Introduction

The history of colonialism in Sabah, the northern expanse of Borneo, might be dated back to the founding of Sandakan in 1879. Within a span of seven years, its colonial government – a British chartered company desperate to attract interest and investment to the territory – confidently depicted this port town as a beacon of progress in a frontier region:

In Sandakan, the capital, there is a temporary church, a club, two hotels, several stores, including a European one, Government offices, gaol, barracks, a fish and general market, hospital, a saw mill, lawn tennis grounds, and many other matters bespeaking advancing civilization. The town is lighted by oil lamps, and there is even a temporary race course. The Chinese have their joss house, and the Mahomedans their mosque.Footnote 1

Published in a ‘handbook’ for prospective investors, this description of various structures, institutions and amenities was meant to convey a sense of permanence, vitality and confidence. In the decades that followed, Sandakan indeed became a keystone of the colonial and commercial system in Sabah, functioning as the central node in a network of ports and outstations that dotted the eastern coast of the territory. To start from 1879 imbues the history of Sandakan and, more broadly, urbanization in Sabah with a narrative of growth, durability and perhaps even triumph. Yet doing so elides a longer history of false starts, misfortunes and failures.

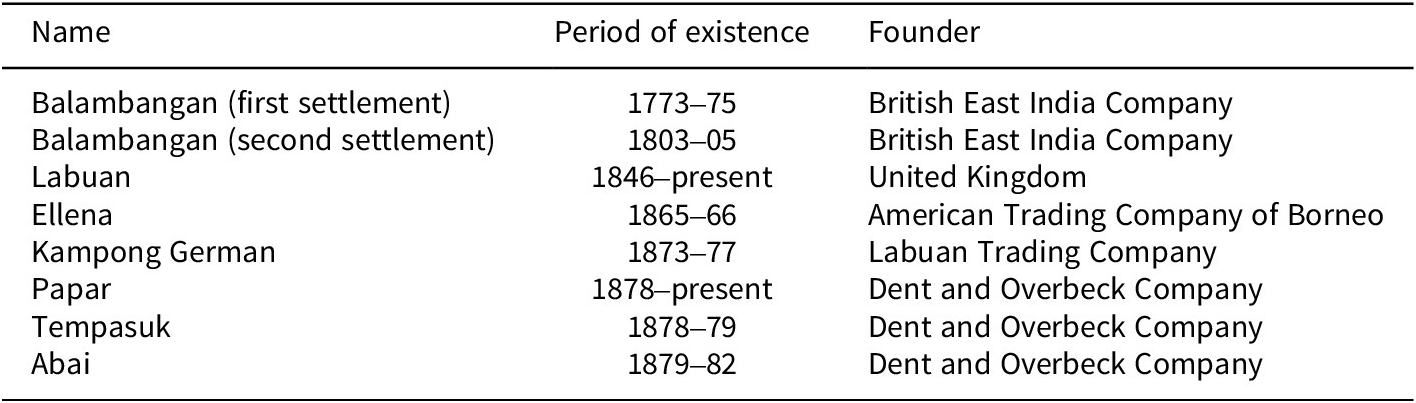

From the 1770s to the 1870s, colonialism in Sabah centred around the search for a suitable port. Over these hundred years, there were eight attempts to establish a foothold on the northern coasts of Borneo that could function as an entrepôt, way station or gateway into the island’s interior. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 1, these were the first and second Balambangan settlements, Labuan, Ellena, Kampong German, Papar, Tempasuk and Abai. Except for one site, all were located on the western coast of Sabah, poised to become part of the commercial world of the South China Sea. But each settlement proved to be abortive – none lived up to the hopes of their American and European founders. With the exception of Labuan and Papar, there are scant physical traces remaining on the landscape to indicate that these sites once existed.

Figure 1. Approximate location of abortive settlements in Sabah, 1770s–1870s.

Source: This map was extracted from Nederlands-Indië Topografische Dienst, Overzichtskaart van het Eiland Borneo. Scale 1:2,000,000. Batavia: Topographische Inrichting, 1909.

Table 1. Details of abortive settlements in Sabah, 1770s–1870s

Tracking the histories of these eight abortive settlements over a century, this article explores why they struggled to survive in their coastal environments. As historian John Galbraith observed, ‘British association with the island since the eighteenth century had been marked by unrelieved frustrations, disillusionments, and failures.’Footnote 2 While the eight settlements were written off for various reasons, their troubles all stemmed from broad issues with security, land and finances. Instead of chronologically detailing the history of each site, this article is organized according to sections that examine these individual factors. It positions the history of abortive settlements in Sabah as part of an extended but discontinuous struggle to colonize and control the coasts of northern Borneo. In doing so, this article makes a broad argument for expanding the spatial and temporal scope of existing research on the history of colonial ports.

The histories of abortive settlements reveal two significant oversights in the literature on colonial ports. First, scholars rarely venture beyond city boundaries, typically focusing on contests of power between municipal authorities and subject communities within urban spaces. Spatial segregation, conflict and resistance have long been staple subjects in the field, although newer studies have turned their attention to more amicable interactions between colonizer and colonized.Footnote 3 Like other urban centres, however, colonial ports were embedded within specific environments with which they had co-constitutive relationships. City-building and natural history were intertwined in fateful ways that deserve further study.Footnote 4 Second, the historiography is overwhelmingly focused on large centres of commerce and culture. This bias is due in part to the outsized presence of major port cities in histories of globalization and long-distance connections. Jürgen Osterhammel specified that the nineteenth century was the golden age of ‘large ports’ because only they had the capacity to expand world trade on a sufficiently extensive scale.Footnote 5 While this was certainly true, the trade of such epoch-defining centres was often supported by an array of minor or intermediate ports within their region. Focusing on leading maritime hubs also risks occluding the diverse forms and functions that ports actually assumed.Footnote 6 To compound this issue, coastal settlements that failed to survive or develop into lasting urban centres are often overlooked in histories of colonization and urbanization. This is a form of survival bias that runs the risk of portraying colonial ports as inexorable and enduring centres of power.

A renewed wave of interest in the maritime dimension of human history from the mid-2000s – variously styled as ‘the new thalassology’, ‘terraqueous histories’ or ‘oceanic histories’ – offers other promising perspectives on colonial urban centres.Footnote 7 Colonial settlements were intricately bound to the large bodies of water along which they were often established. While David Armitage has noted that the histories of empires and oceans ‘intersect and overlap’, John M. Mackenzie pointed that various empires in world history were more precisely concerned with coastal areas.Footnote 8 Perched at the edge between land and sea, port settlements acted as defensible bridgeheads for thalassocracies looking for both access and security.Footnote 9 Focusing on ‘coastal history’, as conceptualized by Isaac Land, makes sense because human activity, like marine biomass, is ‘concentrated close to the shore and thins out in deeper water’.Footnote 10 This metaphor also extends to how colonial power was often concentrated around the edge of the water. Attending to the ways that coastalscapes shaped Sabah’s early settlements, this article thus situates colonial urbanization within the broader context of the relationship between natural and social environments.Footnote 11

Studying settlements that failed to become major ports provides a nuanced understanding of the nature of colonialism in frontier regions. The establishment of colonial ports throughout history, especially in what some considered uncharted and unfamiliar shorelines, involved risk and uncertainty. Founded in 1496 and rebuilt in 1502, Santo Domingo is the oldest extant city established by Europeans in the Americas, located on the southern coast of Hispaniola.Footnote 12 But this longevity overshadows two prior settlements on the northern coast of the island that were short-lived. La Navidad existed for less than a year after its establishment in 1492 by Christopher Columbus, and La Isabela, its successor, was abandoned in 1497.Footnote 13 From its Caribbean base at Santo Domingo, the Spanish created a network of thriving ports around the fertile and mineral-rich regions of Central and South America during the first half of the sixteenth century.Footnote 14 On the other hand, the Dutch, English and French struggled to establish permanent settlements during the first century of the European colonization of the Americas, leaving a trail of failed outposts. According to Eric Nellis, most of their expeditions until the seventeenth century were ‘half-baked, poorly sponsored, or freelance experiments’.Footnote 15 The history of Jamestown, England’s first permanent settlement in the Americas, has long been tied to the mysterious disappearance of its infamous predecessor, Roanoke. With new evidence from historical climatology, Sam White argued that the Little Ice Age had an adverse effect on the European colonization of North America, concluding that ‘there was nothing easy or inevitable’ about this process.Footnote 16 Making a point about the difficulty of furnishing early colonies in North America with sufficient labour and capital, Barbara Solow shrewdly declared that ‘[t]he history of failed settlements may thus be more instructive than the history of successes’.Footnote 17

Beyond the Americas, the process of colonial settlement shared similarly fraught histories of misadventures and setbacks. During the late eighteenth century, the establishment of Freetown in Sierra Leone was preceded by a prior settlement, Granville Town, which was beset with disease before being destroyed by a local Temne leader.Footnote 18 Before the founding of Darwin in 1869, the British raised and deserted six previous outposts in their bid to colonize northern Australia during the early nineteenth century. Archaeologist Jim Allen even proposed that one such site, Port Essington, was not a true settlement intended to open up the region, but was instead a ‘limpet port’ – an outstation meant to preserve British control over Australian sea lanes and to fend off suspected interventions by the Dutch and the French.Footnote 19 Writing about failed Spanish settlements in the Solomon Islands during the sixteenth century, Martin Gibbs underscored the need to ‘explore how different contexts can lead to different colonization outcomes’, including the abandonment of colonies.Footnote 20

The histories of failed ports offer the opportunity of interrogating the broader question of how tenuous the act of establishing a new settlement, and thereby the process of colonization, was in reality. The establishment of a port was not only an imposition on a single site but an entire stretch of shoreline, including its adjacent land and water bodies. The coasts of Sabah, particularly in its western half, were imagined by would-be empire builders to be an ideal location for agriculture, commerce or geopolitical manoeuvring. What they perhaps did not expect was how desolate, unstable and harsh life on these shores would be.

Security

Isolated from established colonial centres in Southeast Asia, early settlements in Sabah were insecure places. Having limited personnel and firepower, they were highly vulnerable to attacks and raids. European rivals were certainly potential threats, but it was indigenous polities – whether they were people from the Bornean interior or the southern Philippines – that settlers were most wary of. From the 1770s to the 1870s, two sultanates held sovereignty over Sabah. The Sultanate of Brunei claimed the western coast, while the north-eastern coast was part of the ‘Sulu Zone’, a maritime region stretching across the Sulu and Celebes seas and dominated by the powerful Sultanate of Sulu.Footnote 21 The rivalries between these sultanates and various European actors framed the historical context of Sabah, casting a shadow over the histories of its early settlements. Even in the late nineteenth century, at the height of European imperial expansion around the world, security remained a chief concern in Sandakan during its early years. One of the first buildings constructed in the new town was a fort equipped with guns to defend against local marauders.Footnote 22 The threat to life and property was thus a persistent cause of anxiety for settlers in Sabah and, in some cases, these fears became reality.

The first recorded British settlement in Sabah was established on Balambangan Island in 1773 by an employee of the East India Company, John Herbert. With this trading post, the company intended to participate in the trade of the eastern Malay Archipelago and southern China.Footnote 23 The scheme to develop Balambangan as a regional entrepôt was the brainchild of another company man, Alexander Dalrymple. In the early 1760s, Dalrymple successfully obtained the cession of the island after signing a series of treaties with the Sultanate of Sulu.Footnote 24 Under Herbert, the settlement at Balambangan traded with local Tausūg and Maguindanao merchants, exchanging opium and powerful munitions – gunpowder, muskets and even cannon – for produce that was sought after in China, such as birds’ nests, pearl shell and sea cucumbers. According to James Warren, however, the proliferation of advanced weaponry led to an increase in inter-ethnic rivalry and violence in the southern Philippines between competing sultanates.Footnote 25 It was in this atmosphere of heightened tension that the Balambangan settlement was razed. After being publicly humiliated by Herbert, Datu Teteng – a cousin of the sultan of Sulu – led a raiding party to destroy Balambangan in February 1775. Despite warnings about a possible reprisal, Herbert did nothing to improve the security of the settlement.Footnote 26 With the destruction of Balambangan, the company lost an estimated £170,000 and its presence in Sabah for the next quarter century.Footnote 27

In 1803, the East India Company reoccupied Balambangan.Footnote 28 Aware of what happened to the initial settlement, its new leader, Robert Farquhar, was accompanied by a sizeable military force: eight ships carrying a total of 800 soldiers. In addition, he brought settlers – mostly artisans and labourers – and enough provisions to last a year. Yet, fearing that these ships and soldiers would be needed elsewhere in Asia if war with France and the Batavian Republic broke out, the company’s directors soon ordered a withdrawal from the island in the spring of 1804.Footnote 29 By the following year, the efforts of the company to establish a foothold in Sabah came to an ignominious end.Footnote 30

Security was also an issue for settlements later in the nineteenth century. In 1877, two businessmen – an Austrian named Gustav Overbeck and a Briton named Alfred Dent – acquired the territorial rights over Sabah from the sultanates of Brunei and Sulu.Footnote 31 These acquisitions kindled a process that eventually culminated, in 1881, with the creation of the State of North Borneo and the chartered company charged with administering it. Before this happened, however, the two businessmen formed the Dent and Overbeck Company in 1877.Footnote 32 A year later, they decided to finance settlements in three locations and stake their claim to the land. On the eastern coast, they established an outpost that later became the port of Sandakan. On the opposite side of Sabah, they founded outposts now mostly forgotten: Tempasuk and Papar.

Papar was an exposed and insecure place, much like the first settlement at Balambangan. The Government House, which symbolized European power, was constructed from flammable material and lacked a stockade, making it hard to defend.Footnote 33 Papar’s first Resident oversaw a period of lacklustre growth and was replaced in September 1879 by A.H. Everett, a former Sarawak official. Everett prioritized political expansion over commerce, reasoning that it would be unfair to encourage locals to invest in the development of the district when the new government could not guarantee its continued presence and protection.Footnote 34 These plans quickly resulted in a confrontation between Everett and Datu Amir Bahar, a local Bajau leader who refused to pay taxes or heed government orders.Footnote 35 In April 1880, the Datu marshalled at least 500 men against Everett, outnumbering the hapless Resident’s force by ten to one.Footnote 36 Behind a hastily constructed barricade around the Government House, Everett opined in his diary: ‘Tonight affairs look terribly black, but there is no going back.’Footnote 37 In the end, the Datu chose to avoid bloodshed and retreated to a nearby river. Although Papar was not seriously threatened after this confrontation, there was a lingering sense of insecurity, and over a hundred families abandoned the area.Footnote 38 When the governor of North Borneo, William Hood Treacher, visited it in August 1881, he found ‘a very small station’ that was ‘in constant fear of hostile action from the neighbouring Bajows’, with the Resident’s authority extending only a short distance from the Government House.Footnote 39 The inability of the authorities in Papar to offer its settlers a sense of safety also discouraged them to invest in the development of the settlement.

Early settlements in Sabah required sufficient protection for their physical survival and expansion. Perched along the sea, these settlements could technically be defended by warships belonging, for example, to the East India Company or the British Navy. From the late 1870s, British gunboats increasingly conducted anti-piracy patrols around Sabah.Footnote 40 During a lecture on the colonization of Sabah at the Royal Colonial Institute in London in 1885, a senior British army officer expressed hope that the Navy would increase its presence in the waters of the fledgling domain: ‘Nothing tends more to encourage loyalty and enhance a feeling of security than frequent visits by the Navy of England; and such are more than ever valued and valuable in the earlier settlement of newly acquired territory.’Footnote 41 Yet these powerful vessels – often under orders to monitor vast littoral regions – were not always stationed at individual settlements, nor could their cannons reach targets far beyond the shoreline. Early settlers were often practically marooned for weeks on end, left to fend for themselves in unfamiliar and unfriendly lands with limited personnel and arms. In this sense, the coast represented a material impediment to thalassocratic power.

Land

The fortunes of a settlement, and consequently its history, were shaped by the land it was embedded in. Fresh water, salubrious environments and fertile soil to grow food were essential for sustaining human life. In places where trade was scarce, a resource-rich hinterland was important for the development of a local economy. For coastal colonial outposts, unrestricted access to the sea for maritime transport was absolutely crucial. The absence of these geographical features resulted in the demise of several early settlements in Sabah. That their planners and pioneers founded them suggests that they were over-optimistic, naïve or ill-prepared.

Even during its brief existence, the second Balambangan settlement faced grave problems that indicated it was a poor choice for a port: the commerce was poor, the soil was infertile and its settlers were threatened by starvation.Footnote 42 Seven decades after it was abandoned, the new government of North Borneo decided not to open a station on the island because its distance from the mainland meant that it held little economic value.Footnote 43 Instead, the governor hoisted the colony’s flag at the approximate site of the abortive settlement in June 1882 and left, never to return.Footnote 44

The third British settlement in Sabah was located on Labuan Island. On Christmas Eve of 1846, the British government founded a port on the island, after James Brooke, later of Sarawak fame, acquired the rights to the island from Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II of Brunei.Footnote 45 The British sought to transform Labuan, with its promising coal deposits, into a naval base to check both local ‘piracy’ and the advance of the Dutch and the Spanish in the region. In addition, it was thought that a port at Labuan would be able to capitalize on trade from north-east Borneo and the Sulu Archipelago.Footnote 46 In fact, at least one British MP, Benjamin Hawes, harboured hopes for the new colony to become a ‘second Singapore’.Footnote 47

Yet, by most accounts, Labuan proved to be a disappointment. First, the colony had a noxious climate because it was in a grassy plain that transformed into a swamp during wet seasons. Many of its inhabitants and visitors alike succumbed to what became known as ‘Labuan fever’.Footnote 48 Second, the trade at Labuan was tepid. Despite the initial flow of trade from north-east Borneo and the Sulu Archipelago, the lack of accessible capital hampered the expansion of commerce on the island.Footnote 49 Third, the much-vaunted coal of Labuan was difficult to extract, expensive and of low quality, making it unsuitable for naval ships.Footnote 50 Finally, it was hardly used as a base to launch anti-piracy actions because Labuan was considered insignificant by the Royal Navy, which concentrated its efforts near Hong Kong instead.Footnote 51 Although it was not abandoned like the other early settlements, Labuan largely failed to accomplish the objectives for which it was founded and remained a secluded backwater. Until the establishment of North Borneo, this quiet port was Britain’s sole outpost in Sabah.

While the British government limited its presence to Labuan, private companies began to take an interest in the mainland of Sabah. In December 1865, the American Trading Company of Borneo founded a colony at the mouth of the Kimanis River named ‘Ellena’ with a group of 11 Americans and approximately 60 Chinese from Hong Kong. This company was led by two American traders, Joseph Torrey and Thomas Harris, who had resided in Hong Kong for several years.Footnote 52 Torrey had secured the cession for a large tract of land in Sabah from the American consul for Brunei, who had himself acquired these rights from Sultan Abdul Momin of Brunei in August 1865.Footnote 53 Ellena was meant to be the base from which the American Trading Company could expand across the rest of the western coast of Sabah, creating a raj in the style of Brooke’s Sarawak.

Torrey and Harris’ dream came to naught as the colony was beset by disease and starvation.Footnote 54 According to the acting British consul general of Borneo, T.F. Callaghan, ‘the great unhealthiness of the place’ resulted in many deaths, and even Harris himself succumbed to a fever in May 1866.Footnote 55 In addition, Torrey only managed to raise a paltry sum of $10,000 for the venture, leaving him without the means to buy sufficient stores or to pay the Chinese settlers.Footnote 56 Callaghan reported that Ellena was ‘supported entirely on credit’ by traders in Brunei who furnished the settlement with supplies. Despite clearing about 90 acres of land to plant rice, sugarcane and tobacco, the settlers slowly starved because they lacked sufficient food.Footnote 57 In November 1866, barely a year after its founding, Ellena was deserted and its American settlers returned to Hong Kong. As the Hong Kong agent of the collapsed company remarked, the enterprise was an ‘entire failure’.Footnote 58 Between 1870 and 1881, Torrey slowly sold off the American Trading Company’s interests and rights in Sabah to Overbeck and Dent, the businessmen whose exploits led to the formation of North Borneo.Footnote 59

A dozen years after Ellena was abandoned, the two outposts that Overbeck and Dent installed on the western coast also faced difficulties with their terrain. Apart from its vulnerability to attack, Papar was situated in an inaccessible location, which impeded its growth as an administrative and commercial centre. It was built over a mile upstream from the mouth of the Papar River, which was obstructed by a large sandbar that prevented steamships from approaching it directly.Footnote 60 During the Northeast Monsoon, Dent observed that the entrance of the river was ‘inapproachable for weeks even for row boats’.Footnote 61 Frustrated by this inaccessibility, the North Borneo government relocated the district headquarters further up the coast to Gaya Island in July 1883.Footnote 62 Although it was not abandoned, Papar did not become a significant urban centre in Sabah.

Further north, Overbeck and Dent’s other outpost, Tempasuk, fared much worse. In 1878, the businessmen left William Pretyman in charge of a site along the Tempasuk River that was six miles from the sea upriver or two miles overland.Footnote 63 Pretyman quickly established himself as a figure of authority by creating an alliance with Pengiran Sri Raja Muda, the leader of the local Iranun people, and forcing two other warring communities – Bajau and Dusun – to make peace.Footnote 64 When a Bajau chief refused to recognize his authority, declaring that ‘the country did not belong to the Company but to the Bajous’, Pretyman kidnapped and sent him to Brunei for execution.Footnote 65 Diplomacy and violence were instrumental to establishing European control over this region. Like Papar, however, maritime access to the Tempasuk outpost was obstructed by a bar at the mouth of the river. To circumvent this problem, Pretyman built a separate port four miles west of the outpost in January 1879, connecting the two by a road.Footnote 66 This new port was named Abai, being located at the mouth of its eponymous river. Within three months, a village of 50 huts had sprung up around the port and its inhabitants were engaged in salt-making.Footnote 67 The development of the district centred around Abai thereafter, and the Tempasuk outpost ebbed into irrelevance.

Geography may not have been destiny in Sabah, but it made a difference to whether a settlement was poised for development or decline. Compared to Labuan, Ellena, Papar or Tempasuk, the port town of Sandakan was situated in a more favourable environment. It sat at the mouth of a large natural harbour, close to several river systems that led into the interior, which enabled it to become a hub for waterborne transport. From this strategic position, Sandakan quickly assumed the role of organizing commodity flows from its hinterland – which supplied a variety of sea and forest produce for the Chinese market since the eighteenth century – fostering its early commercial growth.Footnote 68 Furthermore, the settlement was considered a ‘healthy’ place that was ‘practically free from all malarial influences’ – mangrove swamps, noxious pools and other bodies of stagnant water.Footnote 69 The smell and salubrity of townsites were major health concerns for European settlers, informed by the miasma theory of disease.Footnote 70 In contrast, several early settlements were built on woefully chosen spots along the Bornean coastline.

Finances

After being established, a settlement was expected to be able to pay for itself and, eventually, to generate ample profits. It was imperative that a settlement did not become a financial liability to its inhabitants or investors. The abortive settlements of Sabah were, without exception, driven by avarice. From at least the nineteenth century, European and American writers have, as Douglas Kammen noted, been fascinated by ‘the promise of hidden riches’ in Borneo.Footnote 71 Despite the reputation of Borneo’s mythical abundance of commercial opportunities and natural resources, many early settlers eventually realized that the opportunities had been overstated or, worse still, entirely speculative. Oftentimes, these problems were exacerbated by a dearth of local knowledge.

The fate of an unprofitable settlement depended on its ownership. Sites aligned with the ambitions of imperial states were more likely to receive consistent financial support. Despite being poor and fever-ridden, nineteenth-century Labuan was retained as a crown colony. With its substantial coffers, the British government was willing to underwrite the settlement because it enabled them to monitor their commercial and strategic interests along the western coast of Borneo.Footnote 72 In addition, surveying the potential of the island’s coalfield was a protracted process. Although these deposits were eventually discovered to be substandard, it was time and money that the government was willing to expend in an age where access to coal was vital for shipping and navies.Footnote 73 It was only in 1890 that Labuan was transferred to the British North Borneo Company, which could be counted on to safeguard British interests in the region.Footnote 74 On the other hand, Ellena, the American colony near the mouth of the Kimanis River, had limited financial resources to draw on. When its settlers ran out of food and funds, so too did their capacity and willingness to remain there.

Pretyman’s port on the north-western coast of Sabah, Abai, was not a financially viable settlement despite its promising start. No taxes could be collected from the district because it was poor and the indigenous communities there, though peaceable, were unwilling to pay them.Footnote 75 The governor of North Borneo, Treacher, reported in 1881 that the revenue obtained from the district was ‘not worth consideration’, and the merchant community only comprised two Chinese petty traders, who were keen on leaving. Moreover, the agricultural prospects of Abai’s hinterland were bleak, meaning that the economic situation was unlikely to improve.Footnote 76 Anxious to cut losses, Treacher proposed that the European administrator and the police at Abai be replaced by a government-appointed Bajau chief.Footnote 77 In October 1881, the government took the initial steps to close the port and, by the following year, Abai was abandoned for a new settlement on Gaya Island, approximately 50 kilometres to the south-west.Footnote 78 In an 1882 report, Treacher simply recorded, ‘Abai has proved a failure and been abandoned.’Footnote 79 Pretyman’s ambition to build a flourishing port in this part of Sabah never materialized because the young government could not afford it.

Among all the early settlements in Sabah, Kampong German was exceptional. It was the sole outpost on the eastern coast, far from the shipping lanes of the South China Sea, and never truly conceived as an effort to exploit the resources of its hinterland. In 1873, the Labuan Trading Company established a tiny port on Timbang Island – a small island within the natural harbour of Sandakan Bay – called Kampong German. This private company was founded for the sole purpose of running a Spanish blockade of the Sultanate of Sulu to sell munitions, opium and other contraband.Footnote 80 As it recommenced its efforts to subjugate the archipelago, Spain encircled the port of Jolo, the seat of the sultanate, in November 1871. As a result, the sultanate became increasingly reliant on blockade-runners from Singapore and Labuan to deliver vital supplies in exchange for pearl shell and sea cucumbers.Footnote 81 The company operated out of Labuan until the sultan gave Hermann Schück, one of its blockade-runners, the permission to establish Kampong German.Footnote 82 The name of this trading post was derived from the several Germans associated with the operation, including a merchant named Carl Schomburgk in Singapore, who financed the construction of a warehouse and accommodations at the site.Footnote 83

By most accounts, the Labuan Trading Company successfully used its new port to connect Jolo to Singapore. From its sheltered position within Sandakan Bay, Kampong German was a safe base from which to launch small and stealthy steamships to the Sulu Archipelago.Footnote 84 In 1877, however, the blockade came to an end after Britain, Germany and Spain signed a treaty that guaranteed the freedom of navigation and trade in the archipelago. With its raison d’être and commercial viability now gone, the port was shortly deserted, and the Labuan Trading Company was dissolved.Footnote 85 Kampong German was not strictly a failure. It was created for blockade-running operations and, when this revenue source dried up, it was abandoned – not unlike some of the other abortive settlements in Sabah.

Without riches to be found or made, several early settlements in Sabah were either deserted or consigned to obscurity. Sandakan, in contrast, rose to prominence as the first major port town in Sabah because it had a viable economy. It initially thrived on the export of local produce, such as birds’ nests and rattan, and with the rise of tobacco plantations in the mid-1880s, the port’s commercial growth was secured.Footnote 86 In the absence of similar opportunities to finance their development, places like Labuan, Abai and Kampong German simply faded away.

Conclusion

‘After life’s fitful fever he sleeps well.’

Citing Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the inscription on the gravestone of Thomas Harris, the American co-founder of Ellena, serves as a poignant allusion to his death from malaria.Footnote 87 Standing alone at the top of a hill in Kimanis, along the western coast of Sabah, this gravestone is the sole remnant of that ill-fated colony. It also reflects how the existing literature generally overlooks such failures, inadvertently encouraging triumphal narratives of colonial potency. By studying eight abortive settlements in Sabah, this article has shown instead that the history of colonialism and urbanization in the territory began a century before the founding of its first major port town. It involved a protracted and fraught process of settling coastal regions. Starting from the 1770s, instead of the 1870s, gives this history of colonial urbanization a greater degree of complexity and nuance, infusing narratives of expansionism with loss and disillusionment.

The history of abortive settlements in Sabah demonstrates that the coast represented both a bridge and a barrier to colonial expansion. The might of thalassocracies, for all of its potency at sea, petered out from the edge of the shore. It was reliant on the establishment and maintenance of ports, which were perilous ventures in remote and unsurveyed regions. The early settlements of Sabah commonly struggled with issues related to security, land and finances, which manifested in a variety of forms, from conflict with indigenous communities to torpid economies. Above all, perhaps, they were hamstrung by a profound lack of local knowledge, leading not only to disillusionment among settlers but, in numerous cases, also death. With the exception of Labuan and Papar, these early settlements were all short-lived affairs, succumbing to destruction, disease or destitution. They form part of a broader tapestry of the failure to colonize coastalscapes around the world, from the Americas to the Antipodes. Together, these sites and their histories reveal the inherent limitations of colonial power, underlining how ambition often clashed with the complexity of realities on the ground.

Port settlements that survived and thrived after their first tumultuous years were by no means spared from the challenges of being located in the highly unstable geography of the coast. Even after becoming the capital of North Borneo, Sandakan was troubled by an insalubrious shorefront, limited land for urban expansion and water shortages that hindered daily life and commercial activity. From the nineteenth to the twentieth century, other ports across the colonized world – such as Colombo, Lagos and Port Said – also struggled to control their coastal environments. To shore up their positions in these watery landscapes, states often commissioned costly infrastructural projects like breakwaters, land reclamation and sewage systems.Footnote 88 Far from being bastions of foreign dominance, colonial ports existed in perpetual precarity, much like other maritime urban centres, where human planning was constrained by natural forces. Life at the edge of the sea, as Rachel Carson described, has always been difficult, marginal and unpredictable.Footnote 89

Acknowledgments

I thank Michael Goebel, Yorim Spoelder, Christian Jones and Xinge Zhai for their generosity and guidance. I am also grateful to Lucia Carminati, John Darwin, Olivia Durand, Guadalupe García, Adrián Lerner Patrón, Michael Montesano, Mikko Toivanen and Alexia Yates for their comments on an earlier version of this article.

Funding statement

Research for this article was made possible by Start-Up Grant No. 03INS001315C420 from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Competing interests

The author declares none.