In March 2022, I was in Acre again visiting farms along the Pacific Highway, southwest from Rio Branco, the state capital. The leading agribusiness consultant, who was key in developing expanding soybean and corn plantations, was showing me his working areas. He proudly told me he had planted most of the incipient soy/corn plantations in the state, somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000 hectares at the time, but that was just a fraction of the future growth potential. He boasted, “Acre has an agricultural potential [meaning, for GM soy/corn plantations] of 400,000 hectares.” However, he thought those hectares would never be completely planted as long as there were elite landowners who preferred the cowboy lifestyle of a rancher in Brazil.

Yet, a hectare of soybean and corn rotation would yield about 2,300 reais per year per hectare, while a good ranching hectare would yield only about 800 reais of profit. Thus, even with the lionization of the cowboy culture, soybean plantations were steadily expanding over ranches and pushing ranching deeper into the forests. Simultaneously, both the ranchers and the soybean planters were eyeing the large conservation areas for their flat and fertile soils. All in all, it is a no-win situation fueled by money and power and interests coming from ranching and planting that compete with the interests of the forest.

Establishing Ranching as the Regionally Dominant Political Economy in the Brazilian Amazon

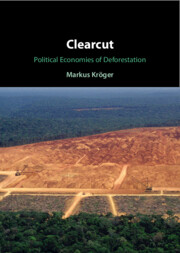

What is the key driving process behind deforestation? Looking from the satellite perspective, ranching and the expansion of pasture land, which cover over 85 percent of deforested areas in the Brazilian Amazon, could be argued to be the key drivers (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.1 Map showing the most significant places in Brazil that are discussed in this book. The Pará region is detailed in Figure 2.2 due to the density of different sites.

Figure 2.1Long description

A map of Brazil highlighting significant, including the Amazon area, Cerrado, and transition zones. Notable cities marked are Manaus, Santarém, Belém, and Brasília. Rivers such as the Amazon, Tapajós, and Araguaia are also shown. Infrastructure such as highways BR319, BR163, and BR230, and the Interoceanic Highway are indicated. National Parks and Indigenous Territories, such as Yanomami and Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve, are also highlighted.

Figure 2.2 A herd of cattle in a large landholder’s pasture in the Brazilian Amazon. Acre, near BR-371 between Rio Branco and Xapuri, March 19, 2022. Brazil has about 160 million hectares of mostly very inefficiently used and extensive pasture land. The nondistribution and ineffective use of these pastures, and their expansion across Brazil, directly drives the Amazon, Cerrado, Atlantic Rainforest, and Pantanal deforestation, as ranchers, for example, move to the Amazon from Bahia. Deforestation is indirectly driven by their claiming land and keeping it from being used more effectively outside of the Amazon.

Currently, about 20 percent of the Amazon is deforested and about 40 percent is degraded (Rodrigues, Reference Rodrigues2023). Ranching and soybean/corn plantations in the Amazon forests have been shown to be pushed or driven by the overall expansion and actions of Brazil’s ranching and plantation agribusiness (Picoli et al., Reference Picoli, Rorato and Leitão2020), which by 2019 had already deforested most of Brazil’s other forests, as only 19–20 percent of the Cerrado and 8–11 percent of the Atlantic Rainforest remain (Ferrante & Fearnside, Reference Ferrante and Fearnside2019). Instead of contending with these land claims made at the expense of Cerrado and other forests and their countless human and other inhabitants, the agroextractivist system, which is capitalist in its character as it continues to seek growth and profit for national and international financiers, has increased its expanse.

A primitive, predatory form of cattle capitalism in the Amazon creates its own logic of hyperextractivism, in the sense that soils are extracted of their vitality and forests of their life (see Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Ranching in the Amazon has expanded very deep into the rainforest and is not an effective use of the space. Acre, near BR-371 between Rio Branco and Xapuri, March 19, 2022.

Figure 2.3Long description

A cattle ranch in the Amazon rainforest. The image shows a large, fenced pasture with a herd of cattle grazing. In the background, there are scattered trees and building-like structures associated with the ranch. The sky is overcast, adding a dramatic effect to the scene. The location is near BR-371 between Rio Branco and Xapuri.

The system drives a general pulling from nature to feed itself as a ranching extractivist system causes widespread degradation. This ranching extractivism was described to me in November 2019 by Carlos, who works for the Kaiapó Indigenous peoples’ association in Novo Progresso, as we drove to the shoreline of the closest river to do an interview:

A person comes, takes away the forest, the wood. After taking out the principal wood, the thickest, he clearcuts the forest and plants pasture. Then the farmer stays on the pasture for five six years, that cattle eating all that pasture which weakens. That land, when degraded by cattle, the farmer does not reform, does not put fertilizer, calcium, does not do any work to retain the water, to recuperate that land. He moves to another region, forest, where he will take away the wood, pull out the forest, and plant again grass.

Pasture-based and inefficient cattle ranching appears to be the primary proximate driver of deforestation in the Amazon (Barbosa et al., Reference Barbosa, Soares Filho, Merry, Azevedo, Costa, Coe and Rodrigues2015). It is present throughout the region, due to the low level of capital required, little need for preparing the soil, and easy extension to steep areas and recently deforested lands (Rivero et al., Reference Rivero, Almeida, Ávila and Oliveira2009). However, behind the proximate causes of pasture land and cattle production, which are driven by the price of meat internationally and nationally, is a deeper mechanism. There are systemic features of the Brazilian political economy wherein land value rise, land speculation and rentierism, illegal land grabbing and clearcutting, can be argued to be as important, or even more important, than the ineffective current Brazilian model of one-cow-per-hectare ranching. The rise in land prices produces more profits and possibilities for capital accumulation than ranching itself. However, fencing, planting grass, and placing cattle on the land are key tools to secure land holdings in deforested areas. For this reason, I suggest calling the key cause of deforestation the creation, expansion, and consolidation of the ranching-grabbing RDPE. Since 2000s, the expansion of deforestation following the parameters of this system has been largely premised on the pushing factor of another RDPE, the soybean, corn, and other monoculture plantations stemming from the south and pushing the frontier of the ranching-grabbing deeper. The presence of these monocultural plantations makes it possible for the land grabbers to gain revenues from increased land valuation, as the soybean planters continue to buy the land. While specificities apply to which land is valued more, the general valuation in the economic sense drives and explains the bulk of where deforestation takes place. These valuations are based especially on the political decisions that accompany major developmental decisions about infrastructure and land tenure regularization schemes.

Forest policies flow from the larger world system of global capitalism, which assigns particular, lower value-adding roles to countries in the Global South, particularly by means of a mix of subsidies and loans, to form regionally dominant, yet developmentally misguided sectors within the primary sectors (see Bunker, Reference Bunker1988). The Brazilian state in the 1960s and 1970s – like many other states guided by the policies of the World Bank, FAO, and other international development cooperation agencies and businesses – had strongly supported the tropical livestock sector installed as a means to “develop” the country (Simmons, Reference Simmons2004). In the Amazon, the subsidized credit lines and political pressure to ranch led to major deforestation (Hecht, Reference Hecht2005; Nepstad et al., Reference Nepstad, Stickler and Almeida2006) and the consolidation of power for an elite group of landholders.

Initially in the 1970s and 1980s, large areas were deforested in the Pará and Mato Grosso states, driven by the expansion of ranching to the Amazon (see Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Map showing the most significant places in Pará that are discussed in this book.

Figure 2.4Long description

A map of Pará highlighting significant, including cities such as Santarém, Itaituba, and Altamira, along with highways such as BR163 and BR230, and notable landmarks such as the Cargill Port, Tapajós National Forest, and Belo Monte Dam. Various indigenous territories including Munduruku and Ituna-Itapecu are also featured in the map.

The speculation practices of large ranchers – backed by state political and economic support (Hecht, Reference Hecht1993; Hoelle, Reference Hoelle2011; Mahar, Reference Mahar1989; Schmink & Wood, Reference Schmink and Wood1992) – created a foothold for a ranching-grabbing RDPE to develop in the Amazon. The Brazilian state created (or was pushed by the rural elites and international financiers to create) the foundations of RDPEs of ranching in several Amazon regions (e.g. in Acre, in the 1970–1990 period) by vast subsidies and political support for land grabs by rural elites from southeastern Brazilian estates. In the Brazilian case ranching did not and does not expand endogenously; rather, its economic prowess was and is created by strong state and international policies that favor the expansion of this system at the cost of other systems. State and international policies provide the infrastructure and promote an overall developmental framing for this key activity (Taravella & Arnauld de Sartre, Reference Taravella and Arnauld de Sartre2012).

The deforesting expansion of the ranching RDPE is partially based on the ample federal-level subsidized credits for Amazon producers and the race to the lowest value-added (ICMS) tax rates for cattle raising, commerce, slaughterhouse, and sales activities between Brazilian states. In the state of Pará, for example, this crucial tax rate was cut from 17 percent in 1989 to only 1.8 percent in 1999. Taravella and Arnauld de Sartre (Reference Taravella and Arnauld de Sartre2012) cite this as a key reason for the profitability and expansion of ranching in the Amazon. However, the economic subsidies for ranching do not solely explain its continued expansion. For example, Hecht (Reference Hecht1993) depicts how ranching continued deforesting activities even when state subsidies were lower. I argue that this is principally because most profits and capital gains come from the speculation and rentierism of those utilizing the ranching/land-grabbing mechanism. Establishing ranches is an effective means to gain access to other benefits, such as taking over conjoining properties or gaining subsidies, credit, tax breaks, and financial gains from land sales (Hecht, Reference Hecht1993). For these reasons, I do not refer to only the ranching alone as the RDPE, but rather the wider system, which I call ranching-grabbing. In the following chapters, I will discuss both ranching and the grabbing separately and as an intermingled system, which constitutes an RDPE.

A key here is to understand the lock-in and path-dependency systemic qualities of RDPE sectors. Once an extractivist RDPE has been set into motion by extensive subsidies like those given to the SUDAM’s (Superintendency of Development for the Amazon, the federal state-created local authority to finance Amazon “development”) mega-ranching projects in the Brazilian Amazon in the 1970s and 1980s, it is hard to reverse the deforestation trend, for example, by withdrawing the subsidies. Hecht (Reference Hecht1993) notes how when the extensive state subsidies were withdrawn in early 1990s from the SUDAM ranching expansion, deforestation increased as the ranching economy had already taken root. Furthermore, the ranching economy was promoted by a series of local economic factors and dynamics and, to a large extent, it was no longer governable by the World Bank and others, despite global changes in attitude toward pasture subsidizing as a form of development cooperation. This example supports my argument on the importance of analyzing RDPEs as key components of global and regional economies.

A key hotspot and example of a regional ranching RDPE is the São Félix do Xingu region, which has been extensively studied by scholars of Amazon ranching (e.g. Schmink & Wood, Reference Schmink and Wood1992; Schmink et al., Reference Schmink, Hoelle, Gomes and Thaler2019; Taravella & Arnauld de Sartre, Reference Taravella and Arnauld de Sartre2012). Taravella and Arnauld de Sartre (Reference Taravella and Arnauld de Sartre2012: 5) emphasize that the cattle sector, more precisely, the large ranchers, easily becomes “dominant” in the local economic, societal, and political systems, which is what happened in São Félix do Xingu. The large ranchers in the area worked together to create an exclusive class association to drive their interests. This move was motivated by rumors of a growing thrust toward the establishment of conservation areas in Terra do Meio where the ranchers wanted to extend their ranching-grabbing activities. These kinds of lobbying associations are powerful and generate dominance and hegemony locally and are also linked to the national Rural Caucus in the Congress. Taravella and Arnauld de Sartre (Reference Taravella and Arnauld de Sartre2012) identify a key feature of ranching power through the São Félix do Xingu case, which is helpful as it details how the “regional” and local aspects of RDPE systems operate by spreading the notion that they provide a local development function. A large ranchers’ association, called Xinguri, frames the local scale where they operate as “powerless and legitimate” and the broader national and international scale as “powerful and illegitimate.” To keep their power, it is important for Xinguri to delegitimize this broader scale because it frames them as Amazon deforesters, a framing that would undermine their status at the local level if it was accepted. Taravella and Arnauld de Sartre (Reference Taravella and Arnauld de Sartre2012: 12) show how the large ranchers strategically use these discourses to frame themselves as the harbingers of “local development,” when in fact they are not even “local,” as in most cases they do not live in or even near the region. In addition, the source of their regional power is derived by policies made outside the region, such as national-level subsidies attained through legislative lobbying to further the “pastoralization of the Amazon.” By their locality discourses, the Xinguri can further consolidate their grip on their distant territorial locations while creating autonomous space for continuing to dominate and expand. For a long time, the discourse pushed by the large ranchers has had a grip on the highest political and judicial systems in Brazil (Taravella & Arnauld de Sartre, Reference Taravella and Arnauld de Sartre2012). This can be clearly seen in the efficient vertical organization of the local dominant agroextractivist systems under the National Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock (CNA).

This system is kept afloat due to ample available financing from banks, which support cattle due to their liquidity and relatively secure quick returns. Cattle are considered “money on [in] the hand,” as they can be sold easily, thus the capital investment has little risk in that sense. This kind of money-making cycle is supported by the world’s dominant political economy – the financialized capitalist world-ecology. In the Amazon, due to strong initial support by dictatorship governments and international lenders, ranching has been turned into the most liquid available form of capital formation, as it can quickly turn money capital (M) into an increased amount of money capital (M’) through a commodity capital (C) cycle, which follows a Marxian M-C-M’ profit-making logic. The rancher “knows that he will finance the opening of that area in a short while, the guy puts there about 100 heads of cattle, and after a while the guy has three hundred, and can pay the bank back.” This logic was explained by Carlos from the Kaiapó Institute. On top of this already profitable cattle system comes the much higher potential of increased land prices and rents, especially in key frontier expansion areas.

Land-Grabbing, Ranching, and Agribusiness Expansion: Speculative Land Value Rise

The degree to which a land area is clearcut, and its proximity to major highways, explain about half the reasons a particular piece of land is valuable. A detailed analysis in Novo Progresso found out that the more clearcut and the closer to the highway, the more the land was valued. Other significant factors that affect land valuations were also identified by Macul (Reference Macul2019). These are, in order of importance, proximity to urban areas, proximity to other roads, the size of the area, and the number of certified farms; these factors, in conjunction with the earlier observations, explain over 80 percent of land value. In 2019, in this key resource and commodity frontier area, I witnessed agribusinessmen planting soybean in clearcut areas even directly beside the BR-163 highway. Clearcutting an area, and building highways and roads, are essential to explaining how land value is created in the Amazon deforestation frontier areas. These RDPEs, based on ranching-grabbing, yield high rents for land value speculation, which are realized especially when a soybean RDPE arrives to the region or the land grabs gain the status of de jure ownership (e.g. by state legalization) or de facto control (e.g. by selling the false title). These acts fortify the existing RDPE of ranching-grabbing, which gains profits and can move deeper into new frontier areas, thus increasing the clout and accumulated economic and social capital of the deforesting extractivists.

In the 2000s, the ranching-grabbing frontier expanded further, as soybean/corn/cotton monocultures, sugarcane ethanol, and eucalyptus plantations took over pasture land and pushed ranchers deeper into previously forested areas. This happened especially in areas adjacent to these commodity frontiers and states, with deforestation spreading to adjacent areas like Rondônia, and to the Mato Grosso and southeastern and southern parts of Pará. In addition, the deforestation also leapfrogged to the Santarém region in western-mid Pará by the Amazon River. The reasons deforestation came to this area also was due primarily to the building permits given, irregularly, to Cargill in 1999 for a soybean export port in Santarém (Schramm et al., Reference Schramm, Andrade, Martins and González Pérez2021). In parts of Pará and Roraima, oil palm plantation expansion has been the sector driving ranching deeper into Indigenous and other protected lands. However, the plantation agribusiness push for the spread of ranching-speculative deforestation was not the only reason for this expansion. The 2000s especially saw the rise of Amazon ranching as a key global economic source of beef and leather, due in part to the overall global commodity boom, where land and commodity prices increased dramatically before and especially after the 2008 financial crisis (Borras et al., Reference Borras, Franco, Gómez, Kay and Spoor2012). In this setting, Amazonian land prices were lower than elsewhere, which meant land could be more easily grabbed, by buying or violence or a mix. The climatic conditions were also suitable for pasture-based production, which supported the choice to rear cattle. Moreover, the proliferation of hoof and mouth disease in many countries, which affected their exports of meat, also contributed to the perception that Amazon beef was a safe source of meat (Hoelle, Reference Hoelle2011).

However, the issue is still more complex, and the proximate evidence of pasture land can hide deeper processes that are not directly or even necessarily linked to ranching. In addition, there are regionally differing sectorial as well as intersectorial and complex pushing factors for deforestation. A key deeper process is the speculative, mostly illegal, and violent land grabbing, which is done for the sake of seeking rising land value. Amazonian ranching should be considered as a component, or a subset, of the speculative Brazilian grabbing-ranching system. Brazil’s ranching is a particularly unproductive form of capitalism (see Dowbor, Reference Dowbor2018) and more of a rentier and speculative system. As Hecht (Reference Hecht1993: 689) elucidates, the Amazon livestock investment is a form of “land use that produces few calories, little protein, and little direct monetary returns compared with other forms of agriculture while producing maximal environmental degradation,” a description that continues to apply to most regions of Brazil today (see Ollinaho & Kröger, Reference Ollinaho and Kröger2021; Reference Ollinaho and Kröger2023). Yet, big exporting ranchers are making very large profits, especially in the past few years.

Key Actors Driving and Curtailing Ranching-Grabbing

Who are the concrete key actors within this RDPE of ranching-grabbing? Several of them are large landowners who are also leading politicians; thus, accumulating both political and economic capital. There are crucial international buyers and companies such as China and Cargill, respectively. The actors who are working to resist deforestation, at the state and grassroots levels, are also important factors in determining how deforestation plays out. In the Brazilian Amazon, ranching has become by far the biggest cause of deforestation, at least by the number of hectares that have been deforested. As an official from the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio)Footnote 1 explained to me in Itaituba in 2019, “the biggest clearcuts we saw this year were for ranching, by the pattern of clearcut, these are sharply rectangular areas forming and you see a great devastation.” Many argued that the biggest rancher in the Itaituba region is its mayor, Valmir Climaco, whom I interviewed in November 2019. The discussions with him revealed the crucial importance of the link the Amazon has to the broader world system. These links are visible in the tightening import rules in the EU and boycotts by several Western companies, which are due to Bolsonaro’s deforesting policies. However, this has not slowed the export of materials too drastically as the beef and leather are now sold to China. This international flow of commodities is a key factor to explain the continued devastation caused by ranching, although a substantial part of the meat is consumed in Brazil and the Amazon itself. During my interview with the mayor, I asked if exports are important for this business, to which Climaco responded, “That is the best business, a success, we are eyeing [for further exports, as it is] much better remunerated. Very interesting.” He argued that the international market is yielding 40 percent more profits, “and we are smiling!” I asked if the price was good: “Very good! The price doubled.” He said that in 2019, 70 percent of cattle were raised for international export and the other 30 percent for internal markets. However, in 2020, 100 percent were intended for the international market, all sold to buyers in China who had recently visited his farm. He said that it takes 39 days for the boat to take the meat from Manaus to China. “I ordered to make a raft that carries 500 oxen” by the rivers. Thus far, he had been selling the cattle to French company Carrefour in Manaus but was shifting to sell through Belém’s Santana port to the Chinese company Okusan.

In December 2023, I interviewed Felicio Pontes, a federal prosecutor at the Federal Prosecution Service (MPF), who was responsible for safeguarding the rights of Amazonian populations against threats by large investment projects. During our interview, I asked who the grileiros are, he explained, “In general, today in Brazil the grileiros are large farmers, those who need all the time more land for cattle. These illegally grabbed lands have been used primarily for cattle.” Their presence is visible in key deforestation frontiers inside Indigenous lands. For example, Senator Zequinha Marinho (Liberal Party, PL) from Pará has tried for a long time to help large ranchers grab lands in the Ituna-Itatá Indigenous Territory, where isolated Indigenous people live (Bispo, Reference Bispo2022). In 2022, I talked with agents from the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) who had documented – during their several weeks-long expeditions to the area – the presence of the Indigenous people who wanted to remain in voluntary isolation. The problem was very thorny and the agents asked to remain unnamed, which was also required in 2022 under the Bolsonaro regime. Even the FUNAI director himself would not listen to the technical reports, but rather tried to help the senator and his ranching speculators. In January 2022, after demands by the federal public prosecutors, a court ordered that FUNAI needed to reinstate the prohibition of outsiders entering the Indigenous land and they needed to drive out the grileiros. Even though entry by outsiders to the Ituna-Itatá Indigenous Territory has been officially restricted since 2011, the area has become one of the most deforested Indigenous lands in the Amazon. The grileiros took note of the weak resistance organization and used clearcutting to turn the area into an unliveable space for the Indigenous groups, as they are dependent on the forests for their livelihood. Between 2016 and 2022, over 21,000 hectares were opened for pasture using fire and illegal logging. Since the area is not yet officially approved, despite the longstanding ban on outsider use, there is still a theoretical chance for regularization of the illegally grabbed lands. Bolsonaro-appointed FUNAI president Marcelo Xavier made a decision in 2020 that took away the protection and allowed legalized privatization of nonapproved Indigenous lands. Subsequently, several courts have deemed this decision illegal (Bispo, Reference Bispo2022). Nearly the entire Ituna-Itatá Indigenous Territory has been self-declared private property in the Rural Environmental Registry system (CAR: Cadastro Ambiental Rural), which shows the extent and extension of illegal land grabbing in Brazil. This example also clearly shows the links between deforestation activities and the highest levels of government, including electoral and institutional politics. A tremendous amount of work is required for progressive state actors to try to resist and overcome judicial and institutional politics. This case shows the complex politics in places where states do not functionally mean the same thing as governments, but are more complex, internally battling sites or arenas (Baker & Eckerberg, Reference Baker, Eckerberg and Duit2014). Even under authoritarian governments, some space tends to remain for resistance from within and outside of the state.

As Brazil’s 39th president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (hereafter Lula), regained power in 2023, and the MPF kept defending the rule of law, in September 2023 the Federal Police started entering the Ituna-Itatá reserve and removing the land-grabbing ranchers. As Federal Prosecutor Felicio Pontes from MPF explained in December 2023, “We have now managed [to push] the government to do the disintrusion, right? The removal of the farmers for the Indigenous land, they are right now doing this.” That area was selected as a key site for intervention due to the critical situation of fast deforestation and land grabbing. Pontes saw that now, as FUNAI will be given time to process the Ituna-Itatá studies, Indigenous land will officially be approved, no longer remaining in the study phase. There are currently about 400 Indigenous lands in the study phase, while the number of staff at FUNAI is “very small” and today the institution is “very weak,” which explained for Pontes why “they do not manage to do [the studies] at the speed we want.” The MPF is responsible for defending the rights of Indigenous and other populations, as a state ombudsman. One important function of the MPF is assisting local resistance when they request help in class action suits. Pontes explained that when both local resistance and the federal or state-level prosecutors are active, they have won in 80 percent of the cases in court. Thus, MPF is highly effective in helping to secure the rights of especially the active forest peoples in the Amazon. For example, even during Bolsonaro’s tenure, the MPF brought a case to court against the Bolsonaro-named FUNAI president, who also was a Federal Police officer, because he wanted to remove the consideration of Ituna-Itatá as an Indigenous land. The MPF won that court case, but often they do not even need to go to court, as simple recommendations given to authorities are enough, especially during periods of more lenient governments. In 2023, Lula appointed an Indigenous FUNAI president, Joênia Wapichana, which is a radical transformation in FUNAI politics. The MPF is also involved in trying to improve the legal setting, their analysts (working under prosecutors), such as Rodrigo Oliveira (interviewed in December 2023), have authored new law projects (such as PL 3025/2023, to make money laundering more difficult and ease the tracking of illegal gold chains).

In addition to the MPF, another key actor group is composed of Federal Police investigators, who specialize in targeting environmental crime. In Santarém in December 2019, I interviewed Gustavo Geiser, a forensics expert on forests at the Federal Police forensics department. He explained that it is more important to burn or destroy the deforestation-causing machinery and equipment than to catch the small operators of deforestation. During Lula’s first terms (2003–2010) there was a major police operation and task force targeting and closing small-scale illegal loggers and sawmills in Pará, as detailed in the book Arco do Fogo written by Federal Police officers active in the operation, which had the same name as the book (de Souza & Borda, Reference de Souza and Borda2019). However, since the operation, new sawmills and operations have taken their place, because focusing on these smaller players brings shorter-term results. In the long run, targeting the large sawmills that export wood was more efficient based on Geiser’s experience in the Belém area, where the effects of this kind of work that targeted the large sawmills could still be seen in 2019, even under Bolsonaro. Geiser argued that the focus should be on tracking, detecting, and exposing illegal documents, instead of running around the forests. The chief of Manaus, another Federal Policeperson, explains in his book how it is essential to detain illegal wood at ports (Saraiva, Reference Saraiva2023). According to Saraiva (Reference Saraiva2023), establishing Command and Control in the Amazon, especially through the Federal Police actions between 2008 and 2017 in the Arc of Deforestation Operation, was not sufficient. The actions became isolated, and thus lost in the vastness of the Amazon, and were “not enough to break the economic motor of the criminals.” This refers also to the crucial importance of first combating the economic and political power, instead of taking an isolated, modern, neoliberal governance approach to criminality. This is because, “when the police, inspectors, and military steps to the region, the loggers are already more than alerted.” As a chief Federal Policeperson operating in various regions of the Amazon, Saraiva focused on causing economic and financial losses to the organized crime by destroying machinery and making it harder to launder money. He found it was most important to hit the already processed, value-added deforesting commodities, such as planks in ports, rather than the unprocessed logs in the middle of the forest, of which about 75 percent are wasted anyway. Therefore, hitting further up in the value chain is more impactful, as “the wood arrives at port after investments also in logistics and transport and, of course, it was already negotiated, has a buyer” (Saraiva, Reference Saraiva2023: 160–161). This strategy makes the damages multifold for the whole chain of illegality in the economic, social, and political senses.

Using the approach of tracking illegal documents, among other projects, Geiser did a satellite report on the Jamanxim illegal logging area on Munduruku lands. I had visited this area on a trip before our 2019 interview, so I was interested to ask him about his experiences there. In 2019, under Bolsonaro, he tried to enter an area of logging he had detected, but he did not get the support of the Army for providing a helicopter as had previously been the case. The Workers’ Party (PT) governments had offered logistical and armed forces support for the police forces targeting environmental crime. During Bolsonaro’s regime, last-minute cancellations of these resources were the rule rather than the exception. This was due to exceptional orders from Bolsonaro to not allow helicopters to be used in such environmental crime situations. In addition, the Minister of the Environment, Ricardo Salles, who was forced to resign in June 2021 when US and Brazilian courts started investigating him and his staff for money laundering and illegal export of wood from Amazon (The Guardian, 2021), had forbidden the IBAMA to use helicopters or to burn equipment used in illegal deforestation.

In August 2023, the Federal Prosecutor’s Office moved the case to court, where Salles was accused of four crimes: including being a key constitutor of organized crime, facilitating illegal trade, advancing personal gain while in public office, and obstructing inspection by public officials while in office. At the same time, Bolsonaro-appointed president of IBAMA, Eduardo Bim, was charged in this scheme for criminal acts of illegal wood exports (Peres, Reference Peres2024). This case shows the depth of government capture by criminally minded entities during the Bolsonaro regime.

Having now covered the key actors and dynamics, I will delve deeper into the RDPE.

Land Value Rise for Ranch Holders

I will now explore the rise of ranch land value caused primarily by agroextractivist plantation expansion as the key cause of deforestation. In April 2022, I did a series of extensive interviews with a rancher and agricultural engineer whose lands were located in the southeastern fringes of the Amazon. He explained how the value of his 2,260-hectare ranch had more than doubled in a year, as soybean planters started to look for land in the area where his ranch is located. He did not want to be identified by name as he was living in tense rural areas, where shootings and even killings take place between ranchers grabbing lands from each other and nonranchers. However, he assured me he was not involved in this activity, which was corroborated by some of my other veritable sources. I will refer to him here as the “modern rancher,” as he stands in comparison to the trope of a “predatory” or “primitive” rancher.

This modern rancher I interviewed explained how it would be much easier and more profitable for him to just rent his land to soybean planters, instead of continuing with ranching. In fact, most of the neighboring ranchers were already renting out their pastures. Ranchers are calculating how much they earn per hectare for cows, and compare this with how much they would earn by renting out the land, also including the value of land in the equation, since they can get more and better loans for expansion as the value of their land increases. They also consider the role of fertilizers, improvement of cow genetics, and other factors and expenses they would have to take care of themselves if they did not rent out the land:

My cost per head [of cattle] was 84 reais per head per month. That gave me a 14 percent profit margin. And I earned 250 thousand reais, that was the farm’s profit last harvest. Which, divided by 1,718 [the number of cattle he has], gives 145 [reais]. This is absolutely horrible because the farm is worth 60 million reais [in the preceding year the value was 30 million reais, about 6 million USD (United States dollars)]. She [the farm] gave 200 thousand. It’s kind of like that, it’s really bad [the profit rate]. It’s just not a total disaster because the area itself [its value increase] corrects itself. So those 60 million that the farm is worth correct themselves because it is the value of the land. So, the farm, what saves it is the real estate issue. The herd is worth 10 million. 10 million to get 200,000 [reais].

It is important to focus on these intersectorial processes to understand the drivers of deforestation. I will first focus on the land value and speculation issues since they seem to move much more money than ranching itself. The modern rancher explained that ranching is a poor but secure business for his region. The main utility comes from ranching’s ability to “occupy land.” He explained, “This is a business that produces very little, but it is very safe, it will always give those 200 thousand [reais]. So, it gives only a little bit, but it does serve to occupy the land very well.” This is precisely the issue in Brazil, in the RDPE that I call ranching-grabbing, with an emphasis on land value speculation. One can earn more with very little effort, due to the rising land values. Thus, ranches serve their owners very well and are the most accepted and de facto functioning judicial-political means of holding onto land and being able to claim proper compensation if one is compelled to give up one’s land to establish land reform settlements or conservation areas. In addition, the laws of the National Institute for Colonialization and Agrarian Reform have favored deforestation, both for large landowners and smallholders. Land clearing has been a legally backed way to secure not only the cleared land, normally for pasture, but an area six times the size of the clearing (Hecht, Reference Hecht1993), which is considered to be the legal reserve required by law. In the Amazon, 20 percent can be deforested, while the other 80 percent should be protected; however, this is not respected in practice and one can legally do logging activity on the “protected” 80 percent, provided it is not clearcut. The 1988 constitution defends land clearers from expropriation that make “effective use of land,” which in practice means they deforest the land and then put cattle on it. Therefore, for a long time deforestation has made sense in this legal setting, as it helps to secure land access, control, and capital accumulation.

Land grabbers are looking for the most lucrative speculative futures where land buyers will enter the area and they can realize their earlier grabs on land, whose legality is usually doubtful. Yet, the potential-seeming legality is reinforced by acts of selling the lands several times, which produces legal-looking papers for these sales, while gaining support from notary officers, politicians, police, and other elite powerholders, at all levels of the state. Therefore, to understand why large swathes of forest are still being clearcut in the Amazon, it is extremely important to understand the presence and push of the soybean/corn plantation frontiers inside and next to the Amazon. The soybean process ensures continued interest by the professionalized sector of land grabbers (called grileiros in Brazil) specializing in the violence needed to dispossess people and retain the lands obtained through land title frauds. These frauds allow grileiros to continue their work to undermine the rule of law and clear forests for the purpose of creating salable commodities, usually in the form of forged land titles. This process was ongoing in 2022 in the Amazon–Cerrado transition forest area where the modern rancher’s farm was located. It was often the case that landholders in the area had inherited their land from a prior generation of pioneering land grabbers from southern Brazil. He explained to me the kind of thinking these landholders were faced with, “Soybeans make much more money, each hectare of soybeans gives 1,500 reais. Look at the difference. Today I earn 145 reais per hectare [with ranching]. If I leased it for soybeans, starting tomorrow, I would earn 1,500 reais without doing anything and the guy was still fertilizing my land [fertilizing he now must pay for himself, when ranching].” However, the modern rancher was not going to rent out his land, unlike the others, as he explained that he likes the ranching business and intended to intensify it with rotational pastures and fertilizing and breeding cattle with good genetics. This affinity for cattle capitalism, ranching, and cowboy culture as a lifestyle, is an important topic I will discuss later in this chapter. Typically, many ranchers, who might be living elsewhere in Brazil or abroad, are on the lookout exactly for the opportunity to not have to worry about production while receiving monthly payments to their accounts for rental agreements. The ranch itself, even if highly valued, does not produce significant yearly earnings if holders continue to ranch in the typical style for Brazil. The modern rancher explained that there is a sectorial joke among the ranchers in Brazil that “A fazendeiro [large farmer] lives poor to die rich.” This joke helps to expose the cost calculating logic that is driving the expansion of plantations, which drives deforesting land grabbing deeper in the Amazon. The modern rancher laid out these dynamics clearly in our conversation:

The business is like this. Just last year, because soybeans arrived, the land doubled in price. It doubled in a year. Now, I’m not going to sell my land, so it’s money I don’t see, but the equity has doubled. The farm was worth 30 million and is now worth 60 million. If you have a forest area in the Amazon, anywhere in Brazil, if you cut it down and plant grass, it will be worth more. Deforested land ready for production is worth much more than an area that must be deforested because deforesting costs a fortune, it is very expensive. So, it’s the same with soybeans. Soybeans arrived and increased the land value. Grass arrives and values the land. It’s a ladder: grass is cheaper and less valuable, but it values it, and soybeans are more technological, much more expensive, and more valuable. And finally, it’s as if it were damage [in the profit-calculation process], the forest is a bad thing in real estate business, right?

Ranching in the Amazon is often not economically viable without major economic and political incentives, with the largest part of revenue increase coming from rising land prices and rents (Carrero & Fearnside, Reference Carrero and Fearnside2011; Hecht, Reference Hecht1993). In 2019, I interviewed the manager of Bela Vista Farm, which is an 80-hectare intensive showcase farm with feedlots and 350 oxen that is located by the Transamazônica Highway west from Itaituba. During our interview he explained that they need to spread fertilizer and calcium every year, as well as replant the grass in several places where the soil is weaker or the oxen step more often. He shared that pesticides are “needed twice a year … due to the forest, since the forest will trouble the grass and the grass lowers.” This was the only farm in Itaituba that had rotational lots, which was rare due to the cost, yet did provide benefits, since, “if left at large, all open, ox will stomp a lot. Stomping, stomping, and not eating. So having fences he goes there and return.” However, this kind of rotational system, which allows for keeping more cattle than possible on the open area, is not in the interests of ranchers in the Amazon or Brazil. This is because the overarching system is not “modern ranching,” but instead it is a system of ranching-grabbing, wherein speculation is more important than anything. In this ranching-grabbing system, cattle serve more as placeholders than being the commodity through which most value is created. According to the Bela Vista manager, most ranchers do not have the money to put the rotational system into practice, but in some cases, money is not the only limiting factor. Most ranchers also do not have the proper knowledge, so they do not know how to do these kinds of rotations in practice. Based on this, a basic characteristic of an extractivist RDPE is that it locks in wasteful and/or unproductive methods of production and it is not set up to incentivize effecting change.

In Amazon ranching, most returns typically come from financial speculation, not from meat sales. This dynamic of rapidly rising five- to tenfold increases in land prices, prompting ranchers to expand further in the Amazon, after land sales or leases to soybean farmers, has been in operation in the Cerrado–Amazon region, especially since the early 2000s rapidly expanded soybean boom (Nepstad et al., Reference Nepstad, Stickler and Almeida2006). This is a particular setting with strong extractivist and capitalist transformations where forests are seen as obstacles (see Figure 2.5). The excerpts given from frontier ranchers expose the kind of mentality and business logic within which are situated the key powerholders who are territorialized into key positions in the Amazon. Very few of them take climatic-ecologic crises seriously into consideration in their actions, although, based on my interviews, increasing droughts, fires, floods, and other volatilities in production conditions are known and felt by practically all of them.

Figure 2.5 Freshly deforested and burned rainforest next to the main highway leading to Belterra, Pará, which will be turned directly into a soybean plantation. The area was still smoking as I passed it. This is becoming a more and more common sight as direct deforestation for soybean plantations increases next to main roads. Brazil, December 18, 2023.

Soybean-Pushing and Ranching-Pulling Dynamics in the Amazon

While especially the soybean frontier pushes the ranching frontier deeper into the Amazon, the ranching, as conducted in the Amazon, creates a need to resituate itself. In the internal logic of Brazil’s typical cattle capitalism, it takes about 10 years to generate a good genetic quality for the herd, which often coincides with the need for major new investments in the form of fertilizing and turning to intensive ranching instead of extensive ranching. Yet many ranchers do not have the money or knowledge to institute this intensive ranching. Therefore, when soybean farming becomes an option, the ranchers have the “tendency … to look for cheaper land,” which is the logic of the dominant system. In 2022, I interviewed a rancher in northern Goiás, in the Amazon–Cerrado transition area, who explained to me:

My own peão de gado, my ranch manager, said: “Why don’t you rent everything here and go to Tocantins and buy another farm? You keep earning your income from here and I’ll go there with you, we raise cattle there in Tocantins.” I said: “Because I don’t want to go to Tocantins, I’ve already come to Goiás, I’m from São Paulo, it took 10 years for me to meet everyone here.” I don’t want to, like, like … but the logic would be … it’s not logical to raise cattle in one place, because soybeans make ten times more money.

A further driving factor from within cattle capitalism itself is the ways in which it causes soil degradation. A modern rancher explained that 20–25 percent of his area is exhausted due to erosion and cannot be used without buying fertilizers, seeds, terraforming, and replanting new grass. It is more aligned with the logic of cattle capitalism – where “ranching gives only little money, so one does not want to invest” – to just go to a new area instead of making the necessary investments. The modern rancher explained that in Brazil, ranching offers on average 100 to 300 reais per hectare, while with soybeans one earns between 2,000 and 3,000 reais per hectare. Due to this reason, he saw that soybean planting is a more important process than ranching even though pastures cover over 160 million hectares and soybean plantations around 45 million hectares. However, due to the enormous difference between the profit rates, the 160 million hectares of pasture in total is less profitable than the soybean areas. For this reason, he saw the soybean sector as one of the key movers of development and more powerful politically than ranching, as it is “richer and better organized” (see Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6 Monoculture soy/corn plantations are being expanded over pasture land, in places that used to be rainforest, thereby expanding the soybean frontier deeper in the Amazon. Acre, near BR-371 between Rio Branco and Xapuri, March 19, 2022.

Figure 2.6Long description

A pasture land with expanded monoculture soy/corn plantations near BR-371 in Acre, Brazil. A large piece of farm machinery apparently a harvester with a large bin or hopper and an auger is prominently featured in the center. On either side are vast fields. The fields extend towards the horizon, where a faint line of trees or vegetation can be seen. The sky is overcast, with a uniform layer of clouds, suggesting a cloudy day.

The ranching and soybean sectors also differ in their demands for technology and infrastructure needed for the volume of production. The modern rancher calculated that he produces about 90 kilograms of meat per hectare per year, while soybeans would produce about 4,000 kilograms of beans (approximately 8,818 pounds) per hectare. This radical difference in volume means that even before the soybeans themselves are planted, the expansion of the soybean sector pushes massive infrastructural expansions, especially ports, paved roads, railroads, canals, electricity, and other major changes in the physical space. However, these pushes would not be possible without having the fundamental requirements fulfilled, which are land availability, access, and control. The resource frontier – where nature is turned into extractable “resources” both physically and mentally – comes before or during the expansion of the commodity frontier (Kröger & Nygren, Reference Kröger and Nygren2020). Ranching in Brazil is a sector that primarily engages in land grabbing, holding, and transferring. Through these processes it creates and expands resource frontiers. The recurrent amnesties offered by Brazilian parliaments to illegal land grabbers incentivize the continuation of the practice of grilagem (the falsification of documents), especially in the so-called arc of deforestation, which currently runs from the western state of Acre to Southern Amazonas, from the state of Pará until Santarém at the confluence of the Tapajós and Amazon Rivers, and then east from there, and in places even hopping over to the northern bank of the river.

Ranchers have also been typically less dependent on banks and other outside entities than soybean cultivators, since they do not need to take such large loans. The modern rancher called the plantation holders “super dependent” on banks in comparison to ranchers. He explained that the banks continually pushed him to take out more loans, but his personal rule was to have no more than a maximum of 25 percent of the value of his herd in loans. At the time of our interview, he only had about 15 percent of the value in loans. Typically, ranchers take loans that equal about 50 percent of their herd value, while soybean producers have several times the value of their crops. As a rancher, he could get loans at an interest rate of about 10 percent per year, while normal Brazilian public sector retirees would need to pay about 30 percent. Ranchers would take this cheap money even if they did not need it, as they could easily invest the money borrowed at 10 percent to gain 15 percent, while pocketing the 5 percent. This was described as “working with the money of the bank as this is cheap.” The modern rancher explained that these comparatively low interest rates are a “privilege that no other sector has,” not to speak of common people. This cheap money makes it possible for the rancher “to be bigger than he is” and grow the herd even if he does not need to. This difference in terms of access to cheap money is a key element when trying to explain the centrality and growth of the ranching-agricultural sector in Brazil in comparison to other sectors. This access to relatively cheap money also helps to explain the consolidation of its territorial dominance. There continues to be a push for deforestation due to the preferential access to low-interest rate loans for ranchers, guaranteed by the aggressive rural lobby. This arrangement also helps the expanding soybean frontier, since the debt generation makes it more likely for low-producing pasture land to be transmitted to soybean producers if the rancher cannot pay the loans. Ranchers get the loans cheaply, since they have the large landholdings registered at the bank as collateral, which the bank can seize.Footnote 2

I discussed these issues related to interest rates and loans with other actors involved with ranching and soybean cultivation in different parts of Brazil. One of them was an agricultural expert, a consultant-company owner called André, who was the key operator expanding nascent soybean and corn plantations in Acre. I traveled in Acre with the consultant in March–April 2022, through the new soybean fields at the westernmost frontier of the soybean expansion in Brazil. André had deep, actual knowledge of the entire chain of operations, in both ranching and field cultivation, and was advising the largest landowners, those who had been resisted by the rubber tappers such as Chico Mendes in the 1980s in Acre. André advised these landowners on how to improve the productivity of their ranching and how to turn their land into soybean/corn plantations and expand deeper in the state. He even walked them through making plans for expanding inside conservation areas, such as the CMER. I traveled with him in the countryside, visiting farms and their owner-patrons, getting to know the way of life, thinking, and talking about these issues. André explained that he, or the large farmer, can get loans with an approximately 5 percent interest rate, which is a factor that helps to explain why soybean production expands and becomes gradually more dominant than ranching. For example, against a farm worth 80 million real, a 50-million real loan normally is taken, with the farm serving as the collateral. With the loan, farmholders can buy the needed capital goods for the ranching–soybean plantation transformation, including harvesters that cost 2 million, tractors that cost 200 thousand, silos that cost 6 million reais, and other smaller things. This is framed as the “modernization” of the business, and consultants, like him, take care of everything. When I was in Acre in 2022, time and again I saw new, but still unused harvesters – which I had never seen in this area previously – that were ready to be deployed to harvest the first crop of corn and soybeans.

Since the 1990s, the value of land has risen dramatically in Acre, which was due at first to the expansion potential and expectation of soybeans and later was related to their actual expansion. André explained how in the late 1990s and early 2000s a hectare of Acrés best agricultural-potential lands, next to the Interoceanic Highway running to Bolivia and Peru from Rio Branco, cost about 100 reais, while later in 2012, when he started to work in the state, the price was up to 1,000 reais per hectare. In April 2022, the price was 20,000 reais or more per hectare, which is an impressive rise from 100 reais. While the value of land does vary, even land next to the rural ramal access roads has increased significantly. These ramal roads are typically not even paved, but rife with mud and bumps, running sometimes legally and often illegally across conservation areas in the Amazon, especially in many parts of Acre. André explained that even in 2002 one could buy land 4–6 kilometers away from this type of road for 500 reais per hectare, but now the same land costs more than 15,000 reais per hectare.

The most marked growth in land prices per hectare started in 2012, which was spurred by legislative changes when the new Forest Code was approved in Brazil. The approval of this Code led to extensive new deforestation due to environmental protection standards being lowered (Kröger, Reference Kröger2017). At the same time, ranches and plantations were expanding, which was a process that had already started at least five years earlier with widespread deforestation, even within conservation areas. On average it takes about five years to deforest an area and turn it into an “open area.” André referred to this deforestation as the primary process required for the land-valuation process to start and continue in a positive feedback cycle. This means that as the demand increases, offers are increased. These changes took place amid the 2008 rise in global commodity prices and profits, following the financial crisis and movement of money into raw materials, which caused a wave of land grabs and land deals (Borras et al., Reference Borras, Hall, Scoones, White and Wolford2011). André explained that once the land has been made available, or “opened,” agricultural expansion is needed for the land prices to soar. He shared that he and his colleagues from the state-level organization of CNA, Brazil’s agribusiness lobby group, whom I also interviewed, were the key players in this process:

[T]he beginning of agriculture here in the state, when we started here in 2012–2013, it was us who started with agriculture on an industrial scale, not family farming with 10–20 hectares, large areas, machines, technology, and all, which were not here before. So, I was the one who started this here in 2013. So, land and agriculture [are needed for the land value rise], agriculture gives more money, if it gives more money, I can sell the land more expensive because the business supports more.

The Infrastructure–Speculation Nexus: Acre

Besides the 2008 increased clearcutting and ranching, and the 2012 expansion of the budding plantation sector and further ranching, another point André mentioned was the 2021 construction of the Ponte do Abunã over the Madeira River, where there was previously only a ferry crossing. Now that there is a bridge, the crucial hub of Porto Velho in the state of Rondônia can be reached in only six hours, whereas before the bridge this took a whole day. This easier access made it possible for the pioneering ranchers and soybean planters – the land grabbers – to reach Acre quickly. This kind of increased access pushes a natural expansion of the frontier. The bridge helps to explain the post-2021 surge, which I witnessed in 2022, of illegal land grabbing inside Acre’s conservation areas by Rondônia-based farmers. This single bridge greatly increased the value of land in Acre and caught the attention of farmers in Rondônia, who often have 10–15,000-hectare monoculture plantations, for example in Vista Alegre do Amanhã. This means that a single farmholder in Rondônia can have the same size monoculture plantation as there was in all of Acre combined in early 2022. These farmholders started to flock into Acre en masse to make illegal deals with the residents of, for example the CMER, who officially could not sell or rent their lots to outsiders. Yet, despite the official rules, they have been lured into this business by the outside rancher-speculators and the iconic, almost one million hectares of conservation area is now poised to become a key soybean plantation area. The consultants I talked to conceded that the land within the conservation area was excellent for these purposes. The closeness of the Pacific Highway and its overgrazed large ranches with their ranchers is a key explanation for why there is a drive and enabling infrastructure for deforestation to eat away the protected forests. Now, these highway projects have also expanded in the west of Acre, which further allows land grabbing through these enabling infrastructure projects.

The existing ranching-grabbing sector of Brazil explains how the infrastructural expansions do lead to deforestation and illegalities. Roads are a necessity for clearcutting to expand and they are the first indication that there will be a major leap in property values. In 2022, I traveled to Cruzeiro do Sul and Mâncio Lima, the westernmost municipalities in Brazil and Acre, to study the project that has been proposed to link Cruzeiro do Sul and Brazil by a highway to Peru’s Pucallpa. The road would cut through major conservation and Indigenous areas, including the Serra do Divisor National Park. I learned from various sources and informants that the road project, which Bolsonaro, the Acre state governor, and local mayors were advancing, but Peru’s then-president Castillo resisted, had already been illegally opened in large parts in Mâncio Lima. There was an ongoing process of land grabbing, especially by the most powerful and largest politician-ranchers operating in the state, especially its westernmost parts, such as the mayor of Mâncio Lima, who belonged to the PT. He had grabbed, according to my sources, large areas of lands next to the proposed and already opened highway line, waiting for the value of these lands to rise, having put cattle already on several areas as “placeholders” for tenure claims. The highway project was linked to ongoing legislative proposals that would take away the protection status from many national parks in the region, opening them for grabbing. However, there was already ongoing speculation inside these areas. The road-building and asphalt companies, largely owned by companies linked to the state governor and elite families, were also waiting for the highway project to start, but were also already benefiting from the push. Lotting and well-remunerated public contracts are key perks for those wishing to expand these roads. The locals often see these roads as providing them with positive possibilities to go to the city faster, while in practice they often end up losing their lands and gaining the attention of violent land grabbers.

By 2022, Acre was seeing the start of the kind of large-scale land grabbing that had already taken place in Pará, Rondônia, and Amazonas, argued Miguel Scarcello, the director of the nongovernmental organization (NGO) SOS Amazõnia, during our March 2022 interview in Acre. The socioenvironmental NGOs and activists were not happy with what the bridge and the agribusiness powerhouses were bringing to Acre, and further explained the novelties and continuities of how the ranching-grabbing RDPE was expanding in Acre. In a sense, the dictatorship-backed and legitimized process, while very violent, had turned into a more rampant and illegal process, which was also violent, but more in the style of decentralized and ungovernable violence promulgated at the time by the Bolsonaro regime. According to Scarcello, the earlier land grabs in the state were not based on grilagem but took place through the state legalizing the actions of farmers who

occupied the lands of rubber tappers, Indigenous people, expulsing, killing them … just taking their lands … this was done with a lot of assistance by the federal government … [which] was close to everything, knew everything, mapped everything. Now we are hearing of invasions of public lands by grileiros who come from Rondônia, conservation units, protected areas, so these people are invading to appropriate [those lands].

In answer to my question about whether the cartórios, the notary offices that register land deeds, are used in this process, which is common elsewhere in Brazil, Miguel replied, no. He explained that the “model of grilagem here is force, threat, and arms. They occupy, destroy, install themselves by force and then go to ask for the right to the land, in the manner that Bolsonaro is incentivizing [them to do].” He saw that since 2019, in the Bolsonaro era, there was a rapid rise in this violent grabbing and more legitimacy was given to this process. This had been done concertedly since 2017–2018 by a “group that is causing headache for the state government,” as they occupy areas all around, “claim themselves to be inhabitants of the area, and demand remuneration or the land for themselves, which creates conflicts.” This is the way the process takes place outside of RESEX, such as CMER, where, according to Miguel, the process differs in that the locals illegally sell a piece of their land to outsiders, especially those from Rondônia. This creates a problem, as the sale and purchase of land inside a conservation area are null deeds and illegal actions, but the buyer remains in the area by force, as the state does not have the power or willingness to remove them or address the problem of these illegal land markets.

Another way deforestation takes place through land tenure changes inside conservation areas like the CMER is renting lands illegally for ranching, where the CMER residents cut the trees against a payment and the outsider brings the cattle. This practice is very common according to another employee of the SOS Amazõnia NGO I interviewed. This expansion of ranching takes place, according to both informants, due to various factors, including the necessity to gain income somehow and very strong pressure by outside ranchers. Turning to ranching deforestation gives instant cash, in comparison to forest products, and is thus more lucrative in the short term. Once this process has started in a 2–3 hectare area, with a few dozen bulls, then a new area is opened, and so forth. Then these opened areas are often invaded by outsider mafia-like actors, who divide the area into lots and sell these to others, which changes the whole character and outlook of the RESEX. This lotting of land and subsequent sale is one more step on the path of turning rainforests into monoculture plantations through ranching expansion and land grabbing and speculation.

In this chapter, I have discussed the role of rising land prices and speculation as the key driver and dominant political-economic sector in explaining deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, drawing on field research and expert interviews in different parts of the Brazilian Amazon. I linked the land-grabbing process to illegalities, violence, and the crucial ranching and soybean/corn plantation expansions, which are mutually self-reinforcing through the logics that operate in these systems.

Chapter 3 discusses the role of land mafias in Brazil, which draws on the longer history of this contextual feature and its connection to the deforesting RDPE.

A key question that I kept returning to during fieldwork was, “Are there different sections within the Brazilian agribusiness sector?” This question refers to some parts of the agriculture and ranching sector being more “modern” while others were more “primitive.” The division here also reaches beyond just the technology applied in the practice of agriculture, as it extends into the sociopolitical arena, with the latter taking care of the dirty work of violent expulsions and the prior attempting to retain the public image of rule of law and rights respect for the international audiences. The answers to this question varied over the course of my interviews, with some interviewees arguing that yes, there are different facets, while others asserted that the relations of these groups are more intimate and closer than they would appear, as they rely on each other and are overlapping. The land grabbing by the primitive, latter group depends on the push of soybean plantations and ranches deeper into the Amazon for the land buyers, while the deforesting and violent actions and illegalities of the latter group suit the goals of the so-called modern agribusiness to gain access to cheap land and privatize state- and smallholder-occupied lands for large capitalists.

A significant part of the problem is the institutionalization of illegal land grabbing, ensured through legal loopholes and ambiguities. Over 60 percent of deforestation activities in the Amazon are linked to multiple forms of illegal acts: illegal logging, grilagem, and illegal forms of agriculture and ranching, which are connected and advance synchronically (Waisbich et al., Reference Waisbich, Risso, Husek and Brasil2022). The invasion and appropriation of public lands in the Amazon are crimes that precede the other illegal activities. Waisbich et al. (Reference Waisbich, Risso, Husek and Brasil2022) argue that it is difficult to separately analyze the distinct deforesting economies or to combat these crimes individually. They call for a more comprehensive and integrated approach to assess the profound causes of environmental crimes and their links with other types of illicit actions. The attack on human, territorial, and environmental rights defenders is systematic and seems to be a necessity for deforestation to advance, since resistance can be effective in halting deforesting investments on many frontiers and by several means (Kröger, Reference Kröger2020c). Since 2009, of the more than 300 registered murders of environmental defenders in the Amazon, only 14 cases were brought to court, and only 1 resulted in a judgment. None of the over 40 cases of attacks and threats that did not lead to death were judged. It is typical of the police to refuse to register threats or nonlethal attacks. According to Human Rights Watch (2019), this lack of effective action shows the impunity reigning in the region, the systematic failure of Brazil to investigate and make the illegal loggers and grileiros responsible for their violence in the Amazon. The situation has worsened dramatically since the 2016 coup against Dilma Rousseff, and especially after Bolsonaro’s 2018 election. In 2020 and 2022, under the Bolsonaro regime, the yearly rates of cases of violence against Brazil’s rural populations were the highest since 1985 (Comissão Pastoral da Terra, 2023). The Bolsonaro regime was built on the power and support of extractivist regionally dominant political economies (RDPEs) and provided them with national- and international-level discursive support and governmental backup, by making the actions of environmental authorities and activists from “outside” much harder. According to Brito et al. (Reference Brito, Almeida and Gomes2021), the current Brazilian federal- and state-level land laws are inadequate and have even boosted deforestation and illegal land grabbing. They identify six key processes through which the current land laws increase Amazon deforestation: (1) continued permission of public land occupations; (2) giving private land titles for deforested or mostly forested areas; (3) nonexistent requirements for environmental recuperation before handing out titles; (4) lack of monitoring of environmental obligations after titling; (5) subsidies for titled properties’ price without guarantees for sustainable land use; and (6) acts by public land institutes that do not follow legal priorities. Land mafias thrive in this institutional context. To redeem these ills, Brito et al. (Reference Brito, Almeida and Gomes2021) recommend the following changes to land regularization policies: (1) establish a time limit for occupation of public lands and prohibit offering titles in areas where environmental laws are broken; (2) demand market prices for public lands that are sold and focus on sustainable uses; (3) forbid the titling of recently deforested estates and demand environmental law conformity before and after titling; (4) establish concessions without rights for deforestation for mostly forested estates; and (5) conduct ample consultation before privatizing public lands.

These measures, when properly applied, would likely be enough to strongly curb the possibilities of land mafias to deforest. This is because a key problem is the recurring legalization of illegally grabbed lands by the Congress and executive power, which are both in the hands of the powerful Rural Caucus. For example, in 2017, President Michel Temer sanctioned Provisional Measure 759/2016, which evolved into Law 13,465 that favored land grabbing and speculation. This allowed large land grabbers to get titles for their illegal claims for negligible amounts that were well below market values and regularized the illegal sale of settlement lands (Carrero et al., Reference Carrero, Fearnside, do Valle and de Souza Alves2020). The law also allowed greater possibilities for illegal land grabbing, for example, by increasing the size of rural estates allowed for regularization from 1,500 to 2,500 hectares (Sauer, Reference Sauer2019). This eased the creation of latifundios and increased deforestation through grilagem (Observatório do Clima, 2017). Bolsonaro further opened new law projects for allowing grilagem. It is precisely this political setting that allowed for legalizing illegal land grabs, which in turn made ranching in forest frontiers “highly profitable” (Carrero et al., Reference Carrero, Fearnside, do Valle and de Souza Alves2020: 980). Worryingly, this has opened new frontiers, for example in the Arc of Deforestation, which is now expanding to the south of Amazonas state. Furthermore, there are novelties in the expansion drivers as the criminal aspects gain more strength. Carrero et al. (Reference Carrero, Fearnside, do Valle and de Souza Alves2020) found that now the key actors at the local level are wealthy people and groups, who launder money by buying settlement lots illegally. This setting encourages the mafia-like dynamics that I observed in several parts of Pará, such as the Santarém region (Kröger, Reference Kröger2024). Worryingly, these land mafia dynamics seem to be rapidly penetrating deeper into the sociopolitical fabric of Brazil.

There are particular people and groups involved in the illegal and violent grabbing of land using rural terror, threats, and hired guns. These land mafias have been called by many names, including “rural militias,” a term used by Human Rights Watch (2019) to refer to groups organized by large farmholders and others who are involved in illegal logging to protect their illegal businesses. These organized groups serve as a type of private security corps, which uses violence and intimidation to safeguard their criminal operations. These farmholders and loggers are essentially criminal networks that have major impacts on deforestation and a strong influence on local politics through their economic clout. Essentially, they are comparable with urban militias. They hire armed men, including from IBAMA and police officers, who then use the cars, weapons, and uniforms of the police. They threaten and attack inhabitants who oppose their criminal activities, as documented by Human Rights Watch.

Deforesting Mafias in Southwestern Pará

In November 2019, I did field research along the BR-163, traveling by car from Cuiabá to Santarém with a reporter from Finland’s national broadcasting company, Yleisradio Oy, a driver, and a fixer. This was a quite intense period to be on the road as it was during the Bolsonaro era and at a time when many forest fires were being purposely lit, especially in the towns and rural areas we were visiting. We saw many fires as we proceeded, lit by land grabbers to claim these lands, to start producing soybeans after a period with pasture. With flames reaching the recently paved roadsides, we stopped to film the fires and ask the locals what was happening (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Fighting against the fires being set in the Amazon. Santarém, Brazil, November 2023.

Figure 3.1Long description

Two individuals in protective gear fighting a forest fire. One person is using a hose to douse the flames, while the other is observing. The scene is set in the Amazon rainforest near Santarém, Brazil. The individuals are labeled as "Bombeiro Militar," indicating they are military firefighters.

In one such area, between Novo Progresso and Itaituba, we stopped to film a new forest fire. Our driver was nervous that we asked to stop, as he had passed the same route earlier with other film crews. Pointing to the fire, he said, “It is not advisable to stay close to these things for a long time.” I asked why. “The people are ignorant.… It can result in problems for us. I believe that [you can stay for] ten, twenty minutes maximum. Because, in the last few days, people are reacting in a way that, here is the shotgun law, in Pará.” I asked if this was illegal. Our driver, who had also worked as a gold digger and a soybean truck driver in the region for a long time, pointed to the fire and answered, “It’s illegal, but that’s their admission,” referring to the fire and us recording it as the proof of the crime. “To avoid a future problem, evidence, a person is thus capable of shooting us at the spot,” our driver explained. They are most worried about the local press putting the video on the evening news, which could create immediate problems for them. He continued, “Let’s leave before someone takes photos of our car and that makes things more complicated for us.”