Introduction

The late Pleistocene is characterized by an expansion of ice sheets, formation of permafrost, and emergence of periglacial circumstances over high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, although no ice sheet expanded in eastern Asia, including the DPRK (Erbajeva et al., Reference Erbajeva, Khenzykhenova and Alexeeva2011).

The late Pleistocene Chongphadae (CPD) Cave Site in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), which has yielded human fossils, a great number of mammalian fossils and stone tools, and spore and pollen fossils, is known as one of the typical sites of the late Pleistocene (Choe et al., Reference Choe, Han, Kim, Ho and Kang2020; U et al., Reference U, Choe, Ri and Han2022; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choe, Kim, U and Kang2023). Therefore, it is an important representative of a late Pleistocene endemic area. Diverse mammalian fossils, including large mammal and small mammal fossils, have been found in the CPD Cave Site, with small mammal fossils playing an important role in characterizing the climatic environment of the late Pleistocene (Choe et al., Reference Choe, Han, Kim, Ho and Kang2020).

In the DPRK, small mammal fossils have generally been described only in fauna studies of the late Pleistocene, and no detailed research has been undertaken (Choe et al., Reference Choe, Han, Kim, Ho and Kang2020, Reference Choe, Han, Kim, Ri and Ri2021).

Small mammals are highly sensitive to changes in the regional environment and are therefore an important component of the regional biota and important indicators reflecting paleoenvironments. The species composition of small mammal communities in the CPD fauna provides insight into the late Pleistocene environment of the CPD Cave Site region.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate species composition of the small mammal assemblage, examine community structure, explain the stages of community development, and reveal dynamics of mesophilous and xerophilous elements in the small mammal community of the CPD Cave Site.

Study area

Geographic location

The CPD Cave is situated in the southeastern part of the township area, Hwangju County (North Hwanghae Province, DPRK) (Choe et al., Reference Choe, Han, Kim, Ho and Kang2020; U et al., Reference U, Choe, Ri and Han2022; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choe, Kim, U and Kang2023). The site is located in the hilly peneplain zone, and its geographic coordinates are 38°40′54″N, 125°47′30″E (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Location of the Chongphadae Cave Site, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

The site region is characterized by a broad plain, low mountains, rivers and streams, and a mild continental climate. The vegetation is principally a Pinus–Quercus community, characterized by plants of the hills, grasslands, and rivers (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choe, Kim, U and Kang2023). The soil type is commonly dark brownish forest soils.

Modern small mammal population

According to modern zoogeographic distribution, the CPD region lies in the Korean lowland forest province. This province contains 19 species of small mammals in 9 families and 4 orders (insectivores, chiropters, lagomorphs, and rodents): Insectivora—Family Erinaceidae: Erinaceus amurensis; Family Soricidae: Crocidura lasiura (Amur hedgehog); Family Talpidae: Mogera wogura (Ussuri white-toothed shrew); Chiroptera—Family Rhinolophidae: Rhinolophus ferrum-equinum (greater horseshoe bat); Family Vespertilionidae: Myotis mystacinus gracilis (whiskered bat), Myotis formosus tsuensis (orange whiskered bat), Eptesicus kobayashii (Kobayashii bat), Nyctalus lasiopterus (greater noctule bat), Pipistrellus abramus (Indian pipistrell), Pipistrellus savii (house bat); Lagomorpha—Family Leporidae: Lepus mandshuricus (Manchurian hare); Rodentia—Family Sciuridae: Sciurus vulgaris (Eurasian red squirrel), Tamias sibiricus (Siberian chipmunk); Family Muridae: Apodemus agrarius (striped field mouse), Apodemus peninsulae (Manchurian wood mouse), Micromys minutus (harvest mouse), Rattus norvegicus (common rat), Mus musculus (house mouse); Family Cricetidae: Clethrionomys rufocanus (gray-sided vole).

Modern small mammal fauna is characterized by typical forest, grassland, and synanthropic species. In the modern small mammal population of this region, the forest species constitute the dominant ecological group and consist of 13 taxa. This population includes the following ecological groups: forest species—Amur hedgehog, Ussuri white-toothed shrew, Japanese mole, Manchurian hare, Eurasian red squirrel, Siberian chipmunk, gray-sided vole, wood mouse, greater horseshoe bat, greater noctule bat, whiskered bat, orange whiskered bat, and house bat; grassland species—striped field mouse, harvest mouse; and synanthropic species—common rat, house mouse, Kobayashii bat, house bat.

Methods

The studied objects are cheek teeth of insectivores, lagomorphs, and rodents (Insectivora, Lagomorpha, and Rodentia) from Layers 8–15 of the CPD Cave Site. The identification of small mammal remains from the CPD Cave was made on the basis of morphological methods specific to rodents, insectivores, and lagomorphs (Young, Reference Young1934; Pei, Reference Pei1936; Zheng, Reference Zheng1984; Choe et al., Reference Choe, Han, Kim, Ho and Kang2020).

With large mammals, composition and population structure of small mammals of each layer are important to characterize the fauna of this region during this period.

Seven samples were examined from seven layers in total. The share of each species in a sample was calculated as the share of maximum number of each taxon in the total number of all remains in the sample.

The grouping of extant species within habitats was performed based on modern distribution of the species, and grouping of extinct species was based on data in the literature (Liu, Reference Liu1967; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhong, Zhou and Wang2003; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Pech, Davis, Shi, Wan and Zhong2003; Hutchins et al., Reference Hutchins, Kleiman, Geist and McDade2004; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang and Sun2004, Reference Liu, Sun and Wang2006; Alexeeva, Reference Alexeeva2006; Sawamukai et al., Reference Sawamukai, Hoshino, Ganzorig, Purevsuren, Asakawa and Kawashima2012; Garcia-Ibaibarriaga et al., Reference Garcia-Ibaibarriaga, Rofes, Bailon, Garate, Rios-Garaizar, Martinez-Garcia and Murelaga2014; Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Ganzorig, Umegaki and Nurtazin2014; Pavlenko et al., Reference Pavlenko, Tsvirka, Korablev and Puzachenko2014; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Khenzykhenova, Simakova, Danukalova, Morosova, Yoshida, Kunikita, Kato, Suzuki, Lipnina and Medvedev2014; Cuenca-Bescós et al., Reference Cuenca-Bescós, Ardevol, Morcillo-Amo, Galindo-Pellicena, Santos and Costa2015; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Cao, Xu, Cao and Zhao2015; Kuzmina et al., Reference Kuzmina, Smirnov and Ulitko2016; Lebedev et al., Reference Lebedev, Bannikova, Adiya, Shar and Surov2016; Rey-Rodríguez et al., Reference Rey-Rodríguez, López-García, Bennàsar, Bañuls-Cardona, Blain, Blanco-Lapaz, Rodríguez-Álvarez and Lombera-Hermida2016; Dammhahn et al., Reference Dammhahn, Randriamoria and Goodman2017; Konidaris et al., Reference Konidaris, Athanassiou, Tourloukis, Thompson, Giusti, Panagopoulou and Harvati2017; Fu et al., Reference Fu, Yuan, Man, Chai, Yang, Bao and Wu2018; Galán-Puchades et al., Reference Galán-Puchades, Sanxis-Furió, Pascual, Bueno-Marí, Franco, Peracho, Montalvo and Fuentes2018; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Ziegler, Starkovich and Conard2018; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Wilson, Hartley, Innes, Fitzgerald, Miller and Heezik2022; Orlov et al., Reference Orlov, Lyapunova, Baskevich, Kartavtseva, Malygin and Bulatova2023). As a result, six groups were identified: forest, meadow, and riverside species (mesophilous species); dry grassland and semidesert species (xerophilous species); and synanthropic species.

Results

Seven samples from Layers 8–10 and 12–15 contained 161 teeth fossils of small mammals (Table 1). The small mammal assemblage from the CPD Cave contains 11 species of small mammals in 5 families (Erinaceidae, Ochotonidae, Castoridae, Muridae, and Cricetidae) and 3 orders (Insectivora, Lagomorpha, and Rodentia): Insectivora—Family Erinaceidae: Erinaceus sp. (hedgehog); Lagomorpha—Family Ochotonidae: Ochotona alpine (alpine pika); Rodentia—Family Castoridae: Castor fiber (Eurasian beaver); Family Muridae: Rattus norvegicus (common rat), Apodemus agrarius (striped field mouse); Family Cricetidae: Cricetulus barabensis (striped hamster), Clethrionomys rufocanus (gray-sided vole), Microtus oeconomus (root vole), Microtus brandti (Brandti’s vole), Myospalax psilurus (Transbaikal zokor), Myospalax epsilanus (zokor) (Choe et al., Reference Choe, Han, Kim, Ho and Kang2020; Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Small mammal remains from the Chongphadae Cave Site, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. (a) Left mandible of Microtus brandti (Ch-8-43), (b) right mandible of Microtus oeconomus (Ch-13-12), (c) right mandible of Ochotona alpina (Ch-14-19), (d) left mandible of Cricetulus barabensis (Ch-8-64), (e) right mandible of Myospalax epsilanus (Ch-9-13), (f) right mandible of Rattus norvegicus (Ch-13-50), (g) right mandible of Apodemus agrarius (Ch-8-57), (h) left mandible of Clethrionomys rufocanus (Ch-8-1), (i) right mandible of Myospalax psilurus (Ch-9-18), (j) left mandible of Castor fiber (Ch-12-1).

Table 1. Species composition and the share (%) of small mammal fossils from Layers 8–-10 and 12–-15 of the Chongphadae Cave, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

One taxon was determined to the genus level: hedgehog; the remaining taxa (10 species) were determined to the species level (alpine pika, Eurasian beaver, common rat, striped field mouse, striped hamster, gray-sided vole, root vole, Brandti’s vole, Transbaikal zokor, zokor). The small mammal assemblage of the CPD Cave Site is dominated by Brandti’s vole (M. brandti; 33.5%), the root vole (M. oeconomus; 24.2%), the alpine pika (O. alpina; 13%), the striped hamster (C. barabensis; 11.2%), and the zokor (M. epsilanus; 7.5%), with the rest of the species being less abundant (Table 1).

Brandti’s vole (Microtus brandti Radde, 1861) is distributed in the dry grassland region of Inner Mongolia, China, and Mongolia (Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Zhon and Sun1985; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Pech, Davis, Shi, Wan and Zhong2003; Sawamukai et al., Reference Sawamukai, Hoshino, Ganzorig, Purevsuren, Asakawa and Kawashima2012; Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Ganzorig, Umegaki and Nurtazin2014). It prefers dry grassland with short grasses (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Pech, Davis, Shi, Wan and Zhong2003; Sawamukai et al., Reference Sawamukai, Hoshino, Ganzorig, Purevsuren, Asakawa and Kawashima2012; Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Ganzorig, Umegaki and Nurtazin2014).

The root vole (Microtus oeconomus Pallas, 1776) is now distributed widely from Europe to Alaska (Garcia-Ibaibarriaga et al., Reference Garcia-Ibaibarriaga, Rofes, Bailon, Garate, Rios-Garaizar, Martinez-Garcia and Murelaga2014; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Ziegler, Starkovich and Conard2018). This species inhabited open humid and woodland environment in the late Pleistocene (Rey-Rodríguez et al., Reference Rey-Rodríguez, López-García, Bennàsar, Bañuls-Cardona, Blain, Blanco-Lapaz, Rodríguez-Álvarez and Lombera-Hermida2016). Root voles are presently absent from the DPRK and inhabit the cold, humid, and open environments of central and northern Europe (Garcia-Ibaibarriaga et al., Reference Garcia-Ibaibarriaga, Rofes, Bailon, Garate, Rios-Garaizar, Martinez-Garcia and Murelaga2014; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Ziegler, Starkovich and Conard2018).

The alpine pika (Ochotona alpine Pallas, 1773) is currently distributed in northwestern Kazakhstan, southern Russia, northwestern China, and northwestern Mongolia (Hutchins et al., Reference Hutchins, Kleiman, Geist and McDade2004). Alpine pikas inhabit open grasslands, mountain slopes, rocky areas, and tundra (Hutchins et al., Reference Hutchins, Kleiman, Geist and McDade2004).

The striped hamster (Cricetulus barabensis Pallas, 1773) is now distributed across northeastern Asia, including the DPRK, China, and the far east of Russia (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhong, Zhou and Wang2003; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Cao, Xu, Cao and Zhao2015). Striped hamsters inhabit dry grasslands and semi-deserts (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhong, Zhou and Wang2003; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Cao, Xu, Cao and Zhao2015).

The zokors (Myospalax epsilanus Thomas, 1912) inhabit dry grasslands in eastern Russia and China’s loess distribution region (Liu, Reference Liu1967; Alexeeva, Reference Alexeeva2006; Pavlenko et al., Reference Pavlenko, Tsvirka, Korablev and Puzachenko2014; Lebedev et al., Reference Lebedev, Bannikova, Adiya, Shar and Surov2016; Orlov et al., Reference Orlov, Lyapunova, Baskevich, Kartavtseva, Malygin and Bulatova2023).

The common rat (Rattus norvegicus Berkenhout, 1769) is currently distributed in wide range from the northern regions of Asia including China or Mongolia, to western Europe and America (Hutchins, Reference Hutchins, Kleiman, Geist and McDade2004; Dammhahn et al., Reference Dammhahn, Randriamoria and Goodman2017; Galán-Puchades et al., Reference Galán-Puchades, Sanxis-Furió, Pascual, Bueno-Marí, Franco, Peracho, Montalvo and Fuentes2018; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Wilson, Hartley, Innes, Fitzgerald, Miller and Heezik2022). It is a common and widespread species due to its close relationship with humans ecologically. Although common rats prefer forest and grasslands and wetlands, they are synanthropic species (Dammhahn et al., Reference Dammhahn, Randriamoria and Goodman2017; Galán-Puchades et al., Reference Galán-Puchades, Sanxis-Furió, Pascual, Bueno-Marí, Franco, Peracho, Montalvo and Fuentes2018; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Wilson, Hartley, Innes, Fitzgerald, Miller and Heezik2022).

The striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius Pallas, 1771) is presently distributed in the DPRK, China, southern Siberia in Russia, and several parts of Europe (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang and Sun2004, Reference Liu, Sun and Wang2006; Osipov et al., Reference Osipov, Sypin, Ilyinov, Ryazanov, Elakov, Afonin and Egorov2006; Kuzmina et al., Reference Kuzmina, Smirnov and Ulitko2016; Danišová et al., Reference Danišová, Valenčáková, Stanko, Luptáková, Hatalová and Čanády2017; Lopucki et al., Reference Lopucki, Klich, Scibior, Golebiowska and Perzanowski2018). Striped field mice inhabit grasslands and hillsides and mainly prefer meadows (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang and Sun2004, Reference Liu, Sun and Wang2006; Kuzmina et al., Reference Kuzmina, Smirnov and Ulitko2016).

The gray-sided vole (Clethrionomys rufocanus Sundeval, 1846) is now mainly distributed in the DPRK, northern China, Russia, and Japan (Kikuzawa, Reference Kikuzawa1988; Batzli, Reference Batzli1999; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang and Sun2004, Reference Liu, Sun and Wang2006; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Khenzykhenova, Simakova, Danukalova, Morosova, Yoshida, Kunikita, Kato, Suzuki, Lipnina and Medvedev2014). Gray-sided voles mainly inhabit forest, grassland, and farmland (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang and Sun2004; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Khenzykhenova, Simakova, Danukalova, Morosova, Yoshida, Kunikita, Kato, Suzuki, Lipnina and Medvedev2014).

The Transbaikal zokor (Myospalax psilurus Milne-Edwards, 1874) is an endemic species of Asia, widely distributed in eastern Russia, the northern parts and Inner Mongolia in China, and northeastern Mongolia (Alexeeva, Reference Alexeeva2006; Pavlenko et al., Reference Pavlenko, Tsvirka, Korablev and Puzachenko2014; Lebedev et al., Reference Lebedev, Bannikova, Adiya, Shar and Surov2016; Fu et al., Reference Fu, Yuan, Man, Chai, Yang, Bao and Wu2018; Orlov et al., Reference Orlov, Lyapunova, Baskevich, Kartavtseva, Malygin and Bulatova2023). Transbaikal zokors inhabit the meadow steppes and forest-steppes (Pavlenko et al., Reference Pavlenko, Tsvirka, Korablev and Puzachenko2014; Fu et al., Reference Fu, Yuan, Man, Chai, Yang, Bao and Wu2018).

The Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber Linnaeus, 1758) is now distributed in Eurasia, including eastern Siberia, China, and Mongolia (Hutchins et al., Reference Hutchins, Kleiman, Geist and McDade2004; Barisone et al., Reference Barisone, Argenti and Kotsakis2006; Cuenca-Bescós et al., Reference Cuenca-Bescós, Ardevol, Morcillo-Amo, Galindo-Pellicena, Santos and Costa2015; Konidaris et al., Reference Konidaris, Athanassiou, Tourloukis, Thompson, Giusti, Panagopoulou and Harvati2017; Athanassiou et al., Reference Athanassiou2018), but not in the DPRK. Eurasian beavers inhabit wetlands, rivers, streams, ponds, and lakes surrounded by abundant arboreal vegetation (Hutchins et al., Reference Hutchins, Kleiman, Geist and McDade2004; Cuenca-Bescós et al., Reference Cuenca-Bescós, Ardevol, Morcillo-Amo, Galindo-Pellicena, Santos and Costa2015; Konidaris et al., Reference Konidaris, Athanassiou, Tourloukis, Thompson, Giusti, Panagopoulou and Harvati2017).

The hedgehog (Erinaceus sp.) is distributed in Eurasia, Africa, southeastern Asia, and even New Zealand (Hutchins et al., Reference Hutchins, Kleiman, Geist and McDade2004). Hedgehogs inhabit wide ranges from woodlands to grasslands and deserts and mainly prefer to live in forests in the DPRK (Hutchins et al., Reference Hutchins, Kleiman, Geist and McDade2004).

The small mammal remains were discovered from Layers 8–10 and 12–15, and two dating results for Layers 12 and 13 have been published (Choe et al., Reference Choe, Han, Kim, Ho and Kang2020; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choe, Kim, U and Kang2023). For Layers 12 and 13, 14C dating returned the results of 26,540 ± 1830 yr BP (34,770–27,800 cal yr BP) and 19,370 ± 780 yr BP (24,980–21,340 cal yr BP), respectively.

Layers 8–15, in which small mammal remains were discovered, correspond to the end of Marine Oxygen Isotope Stage (MIS) 4 to MIS 2 according to the age–depth model, which was based on the results of various datings of the CPD cave sediments and pollen analysis (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choe, Kim, U and Kang2023).

Discussion

Small mammal communities in the CPD Cave and their stages of development

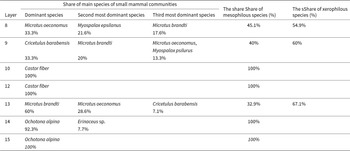

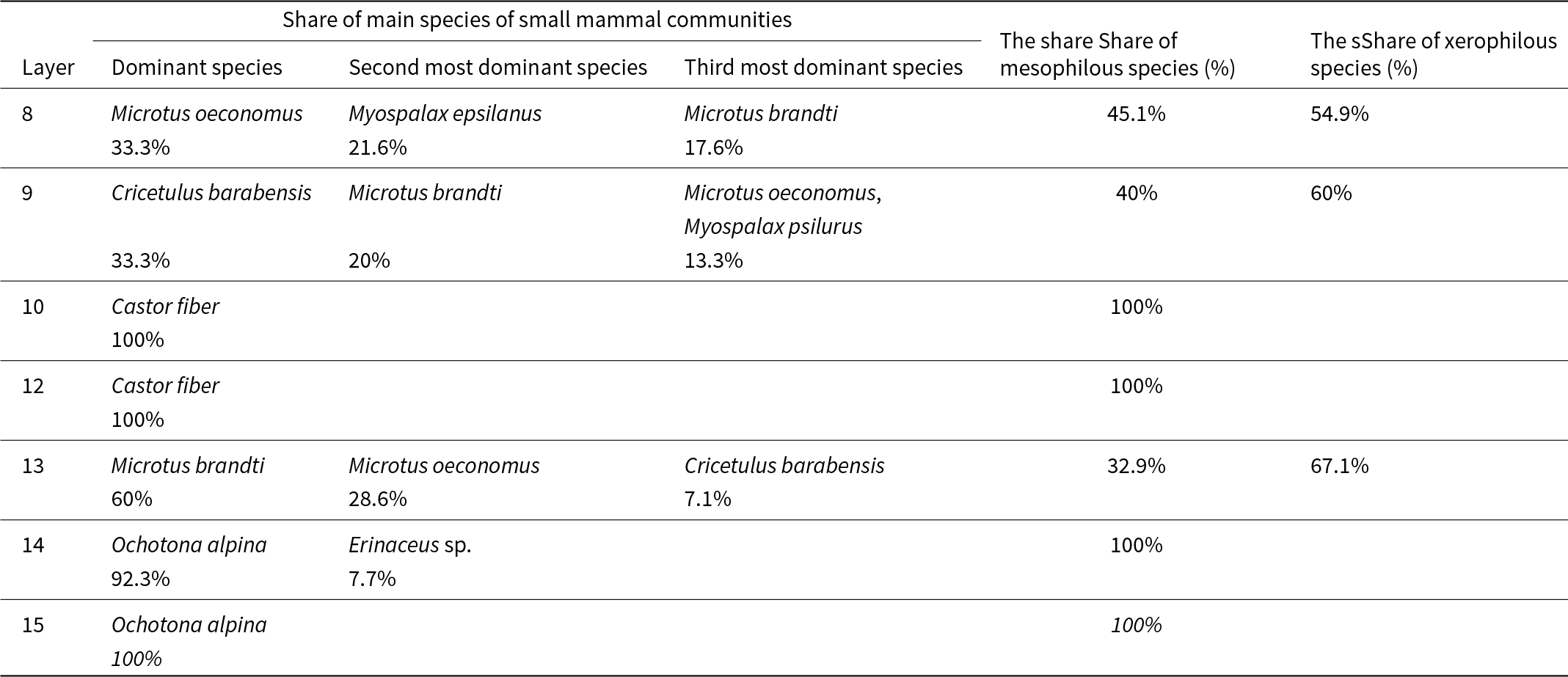

The small mammal community development of the CPD Cave consisting of 11 species has five stages. The dynamics of mesophilous and xerophilous elements (forest, meadow, and riverside species) (Kuzmina et al., Reference Kuzmina, Smirnov and Ulitko2016) and xerophilous elements (dry grassland species) (Kuzmina et al., Reference Kuzmina, Smirnov and Ulitko2016) are marked on Fig. 3. The data for the stages of small mammal community development are shown in Table 2.

Figure 3. The species share dynamics of small mammals and dynamics of mesophilous (forest, meadow, riverside) and xerophilous (dry grassland) species in Layers 8–10 and 12–15 of the Chongphadae Cave Site, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

Table 2. The stages of the late Pleistocene small mammal community development of the Chongphadae Cave Site, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea of the Late Pleistocene.

The development stages of small mammal communities correspond to 62.122–19.630 ka of the late Pleistocene using the age–depth model for the CPD Cave Site profile (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choe, Kim, U and Kang2023).

Stage I (62.122–51.610 ka) is the formation age of Layer 8 and is composed of seven species. This first stage of community development is characterized by the domination of root vole and zokor (33.3% and 21.6%, respectively). Brandti’s vole is the third most common species (17.6%). The common rat is a synanthropic taxon in this stage. This stage is characterized by a higher share of xerophilous (54.9%) than mesophilous species (45.1%).

Stage II (51.610–46.408 ka), the formation age of Layer 9, is composed of seven species, but differs in composition from the previous stage. This stage is connected to an increased striped hamster’s share and subsequent increase in the share of the Brandti’s vole. The dominant species is the striped hamster (33.3%), the codominant species is Brandti’s vole (20%), and the root vole and Transbaikal zokor (13.3% each) are the third most dominant species. The ecology associated with the striped hamster and Brandti’s vole is dry grassland (Sawamukai et al., Reference Sawamukai, Hoshino, Ganzorig, Purevsuren, Asakawa and Kawashima2012; Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Ganzorig, Umegaki and Nurtazin2014). The share of xerophilous elements is increased to 60%, and the share of mesophilous elements is reduced to 40%. In this stage, the common rat, a synanthropic species, still exists.

Stage III stage (46.408–30.344 ka), the formation age of Layers 10 and 12, is composed of a single species, C. fiber. All the species that existed in the previous stage disappear, and the Eurasian beaver appears. This constitution of a single beaver that inhabited riversides shows that the ecological conditions of Layers 10 and 12 were extremely humid and provides evidence that the environment was under cooler and wetter climatic conditions than in the previous period during the formation age of Layer 10 (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choe, Kim, U and Kang2023).

Small mammal fossils were absent from Layer 11, and only large mammal fossils were found (Choe et al., Reference Choe, Han, Kim, Ho and Kang2020). Eurasian beaver fossils were found in Layers 10 and 12 and not in Layer 11. It was supposed that small mammal fossils including the Eurasian beaver may be resulted from external factors or changes during excavation process period. It can be seen by spore-pollen fossils collected in Layer 11. Layer 11 includes much smaller spore-pollen fossils than the other layers, and among them, except for Platycarya and Corylus, seven taxa were herb plants and the share of taxa that inhabited humid forests is 66.7% (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choe, Kim, U and Kang2023). This supports the possibility of the existence of Eurasian beaver in Layer 11. The share of mesophilous element is 100%, with no xerophilous taxa.

Stage IV (30.344–24.765 ka), the formation age of Layer 13, consists of four species. The Eurasian beaver disappears, and the common rat, the striped hamster, the root vole, and Brandti’s vole, which existed in Stage II, reappear again. The dominant species is Brandti’s vole (60%), the codominant species is the root vole (28.6%), and the striped hamster (7.1%) is in the third position. The proportion of mesophilous species is reduced to 32.9%, and the proportion of xerophilous species increases to 67.1%. The common rat, which is a synanthropic species, reappears in this stage.

Stage V (24.765–19.630 ka) is the formation age of Layers 14 and 15 and consists of two species (Layer 14: O. alpina, Erinaceus sp.; Layer 15: O. alpina). The dominant species is alpine pika (Layer 14: 92.3%; Layer 15: 100%) and the codominant species is hedgehog (7.7%). In this stage, only mesophilous species exist.

Dynamics of mesophilous and xerophilous elements in the small mammal communities of the CPD Cave

In the late Pleistocene, the ecology of small mammal communities of the CPD Cave Site is characterized by the alternation of mesophilous and xerophilous elements as a whole.

Phase I (Stages I and II of community development) showed the domination of xerophilous elements that gradually increased (from 54.9% to 60.1%), and the reduction of mesophilous elements (from 45.1% to 40%). Phase II (Stage III) revealed the existence of only a mesophilous element. Phase III (Stage IV) is connected with aridity, with the reduction of the mesophilous elements (32.9%) and domination of xerophilous elements (67.1%). Phase IV (Stage V) revealed the disappearance of all xerophilous elements and the existence of only mesophilous elements.

The environment of Phase I, which is dominated by xerophilous elements, corresponds to MIS 4 (Svendsen et al., Reference Svendsen, Alexanderson, Astakhov, Demidov, Dowdeswell, Funder, Gataullin, Henriksen, Hjort, Houmark-Nielsen and Hubberten2004) based on pollen fossils (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choe, Kim, U and Kang2023) and is in accordance with the tendency toward cooling and aridization, because the tree taxa such as Fagus and Acer dominated, and taxa indicating cool and dry conditions, such as Saxifragaceae, Rhododendron, Plantago, and Geranium, appeared. Phase III is related to the dominance of xerophilous elements and reflects the cool and arid conditions of MIS 2 (last glacial maximum) (Svendsen et al., Reference Svendsen, Alexanderson, Astakhov, Demidov, Dowdeswell, Funder, Gataullin, Henriksen, Hjort, Houmark-Nielsen and Hubberten2004) based on pollen fossils (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choe, Kim, U and Kang2023). During this period, the tree taxa Pinus, Morus, and Corylus predominated, and Larix, Corylus, and Saxifragaceae were present, indicating a cold climate.

Phases II and IV, which are connected by the existence of only mesophilous elements, reflect the slightly warm and wet environment during the end of MIS 4 to MIS 3 (Phase II) and during the interglacial period of MIS 2 (Phase IV) (Berto et al., Reference Berto, Luzi, Canini, Guerreschi and Fontana2018; Fernández-García, Reference Fernández-García2019; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choe, Kim, U and Kang2023). Based on pollen analysis, this period represents some short-term climate fluctuations and is characterized by decreasing in the number of species indicating cold climate, such as Corylus and Saxifragaceae.

The species of small mammal remains discovered in the CPD Cave Site and Ryonggok Cave Site No. 1 were same (11 species); however, Ryonggok Cave No. 1 is characterized by a small number of small mammal remains and no xerophilous species such as C. barabensis, M. brandti, and M. epsilanus (Choe et al., Reference Choe, Han, Kim, Ri and Ri2021). This shows that during the late Pleistocene, the CPD Cave Site region experienced heavier climate fluctuation compared with the Ryonggok Cave Site No.1, but was favorable to animals existence.

Conclusion

The species composition of the small mammal assemblage of the CPD Cave Site is 3 orders, 5 families, and 11 species. Among 1 insectivore, 1 lagomorph, and 9 rodent taxa, no species was present constantly, and all taxa were unstable, with fluctuating absence–presence.

Today, only four taxa exist and seven taxa have disappeared from study area: xerophilous elements—C. barabensis, M. brandti, and M. epsilanus; mesophilous elements—Microtus oeconomus, M. psilurus, C. fiber, and O. alpina. All the xerophilous elements that existed in the CPD Cave Site in the late Pleistocene have disappeared.

Considerable changes occurred in the development of small mammal communities. The dynamics of mesophilous–xerophilous species defined five main stages of community’s development. Xerophilous elements dominated Stage I community development, with the domination of the Transbaikal zokor, Brandti’s vole, and striped hamsters. Alternating between mesophilous and xerophilous elements, the last stage of community development is characterized by the existence of only mesophilous elements, such as alpine pikas and hedgehogs.

The development period of small mammal communities of the late Pleistocene in the CPD Cave Site region is characterized by a dynamic that alternates between forests, meadows, and riverside conditions and dry grasslands.

The dynamics of the CPD small mammal communities demonstrate that the modern mosaic landscape, which consists of forest, grassland, and riverside, was formed in the course of such diverse environments alternating during the late Pleistocene,

The late Pleistocene climatic change of the CPD Cave Site based on the small mammals found there roughly corresponds to the palynological record on the local scale; the paleoenvironmental reconstruction from the Ryonggok Cave Site No. 1 in the central part of the DPRK; and climate events in north Eurasia and North America on the global scale.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kwang Sik So (Institute of Natural Sciences, Kim Il Sung University) and Kwang Min Kim, To Jun Ryang, and Yong Su Ju (Faculty of Resource Science, Kim Il Sung University) for their constructive comments and suggestions on the article.