1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, the crisis of the global cryosphere—evidenced by the accelerating loss of glaciers, sea ice and permafrost (Comiso and others, Reference Comiso, Parkinson, Gersten and Stock2008; Schuur and others, Reference Schuur, McGuire, Schädel, Grosse, Harden, Hayes and Vonk2015; Hugonnet and others, Reference Hugonnet2021; The GlaMBIE Team, Reference The GlaMBIE Team2025)—has come to be one of the most certain and troubling signs of the advance of anthropogenic global warming. While cryospheric losses have been a matter of scientific concern since the 1950s, public recognition of both ice losses and their implications (e.g., sea level rise) has been slower to develop. This gap between scientific concerns and public awareness has created an opportunity to communicate findings and mitigation pathways in order to impact policy, institutions and behavior. As Susanne Moser wrote, already 15 years ago,

Now more than ever, it is crucial to ask instead how to communicate a global problem that involves less certainty and immediacy than most other, more familiar problems, yet which also has the potential for far graver implications than previous challenges. (Moser, Reference Moser2010)

Studies of opinion polls suggest that it was not until the 1990s that surveyed majorities in most countries reported being aware of global warming as a phenomenon, and even then, uncertainty persisted as to global warming’s causes, consequences and severity (e.g., Nisbet and Myers, Reference Nisbet and Myers2007). Much has changed in the past three decades. According to a 2022 Pew Global Attitudes Survey, a median of 75% across 19 countries in North America, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region labelled global climate change as a major threat, a higher percentage than those who saw the global economy (61%) or the spread of infectious diseases (61%) as major threats (Pew Research Center, Reference Center2022). It is impossible to calculate precisely how much climate communication efforts, either individually or in aggregate, have contributed to this transformation of attitudes since direct experiences of the effects of climate change (e.g., changing weather patterns, droughts, fires, floods) have also increased during the same period. Yet, there is clear empirical evidence not only that climate messaging has the capacity to change attitudes but that the efficacy of messaging depends on how information is presented and narratives are composed (Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, van der Linden, Mildenberger, Marlon, Howe and Leiserowitz2018). Communication strategy, in other words, matters (Oreskes and others, Reference Oreskes, Howe, Boyer and Johnson2025).

Efforts to increase and improve climate communication related to cryospheric loss have taken many forms over the past 65 years, ranging from documentary films and educational television programs to website and social media activity, interactive and immersive media, glacier funerals and storytelling platforms like the Global Glacier Casualty List. All have sought to translate the too often distant or abstract phenomenon of cryospheric diminishment into images and narratives that inspire political and behavioral change. This letter selectively reviews these efforts’ innovations, impacts and limitations to better inform the scientific community about the wide range of communication opportunities that exist beyond specialized academic publications. The authors concede there are no perfect metrics of media impact. With some exceptions, the primary focus here is English-language media whose impacts have been identified and discussed in academic scholarship and public culture. The main conclusion of this review is that collaboration between natural scientists, social scientists and artists continues to offer significant promise in raising public awareness of ice loss and related environmental problems.

2. A brief history of media efforts to raise public awareness of anthropogenic cryosphere loss

2.1. Early efforts in documentary film and educational television (1958–90s)

Scientific recognition of greenhouse gas impacts dates back to the 19th century (Fleming, Reference Fleming1998). Rachel Carson noted in her bestselling book The Sea Around Us that ‘the frigid top of the world is very clearly warming up’ (Carson, Reference Carson1950), though she did not link Arctic warming to anthropogenic emissions. With scientific consensus on human-induced climate impacts still decades away, the late 1950s saw the first serious scientific discussions and warnings concerning anthropogenic climate change as prominent scientists like Edward Teller linked fossil fuel usage to the greenhouse gas effect. Teller spoke at an American Petroleum Institute event in November 1959, advising that anthropogenic warming could have devastating consequences on coastal cities,

It has been calculated that a temperature rise corresponding to a 10 per cent increase in carbon dioxide will be sufficient to melt the icecap and submerge New York. All the coastal cities would be covered, and since a considerable percentage of the human race lives in coastal regions, I think that this chemical contamination is more serious than most people tend to believe. (Franta, Reference Franta2018)

The previous year saw the broadcast of what is generally regarded as the first television program to predict a coming climate crisis, Unchained Goddess. Unchained Goddess was part of the Bell System Science series of education television programs that first aired between 1956 and 1964 but which later became staples of US high school and college science programs, reaching more than five million children by the mid-1960s (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert1997). Produced by Academy Award winner Frank Capra, Unchained Goddess utilized an innovative blend of animated and live-action content to educate the wider public about how complex weather systems operate. Toward the end of the program, a brief montage shows factories, automobiles and collapsing ice sheets as the film’s scientific expert cautions that:

Even now, man may be unwittingly changing the world’s climate through the waste products of its civilization. Due to our releases in factories and automobiles every year of more than six billion tons of carbon dioxide, which helps the air absorb heat from the sun, our atmosphere seems to be getting warmer. … It’s been calculated that a few degrees rise in the earth’s temperature would melt the polar ice caps. And if this happens, an inland sea would fill a good portion of the Mississippi Valley. Tourists in glass bottomed boats would be viewing the drowned towers of Miami through 150 feet of tropical water. (Carlson and Hurtz, Reference Carlson and Hurtz1958)

Although the program efficiently provided a visual language of climate change causality, the subjunctive mood of ‘may be’ statements softened the warning of melting ice caps and drowned coastal cities, as did the brevity of its thematization. In other early documentary projects, like the BBC’s 1974 program, The Weather Machine, climate messaging focused more on the uncertain and potentially chaotic consequences of a changing climate rather than on the feedback loop of anthropogenic warming hinted at in Unchained Goddess. Indeed, the main focus of The Weather Machine was the speculative possibility of a new ice age rather than an era of anthropogenic warming.

The 1980s saw the rise of much longer and more detailed portraits of climate change and cryospheric impacts, evidenced by programs like British ITV’s 1981 ‘Warming Warning’, the first feature-length television documentary focused on anthropogenic warming and its consequences. Its narration begins,

Since the time of the Industrial Revolution, Man has consumed huge and increasing amounts of fossil fuel to sustain the growth of industrial societies…Meteorologists now believe that increased quantities of CO2 in the atmosphere will lead to significant warming of the planet within decades. (Broad, Reference Broad1981)

The program goes on to discuss the consequences of rising carbon dioxide concentration, including atmospheric and oceanic warming. When it comes to the cryosphere, however, the program is more equivocal, pairing an emphasis on the ‘tentative’ evidence of polar warming with a discussion of how the Ross Ice Shelf destabilization could lead to as much as 5–8 meters of sea level rise on its own, inundating coastal cities like London. The detailed engagement of climate science and climate projections in ‘Warming Warning’ far exceeds earlier efforts, yet its cautious tone emphasizes the need for further observation and data gathering over mitigation action. ‘Warming Warning’ was also the first program to highlight how advances in computation would help scientists to refine their climate models and impact scenarios over time.

A more creative mode of climate messaging was offered by the Maryland Public Television/Film Australia co-production, ‘After the Warming’, which first broadcast in 1990. Hosted by journalist James Burke, ‘After the Warming’ structured its narrative through the conceit that Burke was speaking to the audience from the year 2050, utilizing a ‘virtual reality generator’ to return in time to the 1990s to understand how the ‘greenhouse effect’ had forced a number of political (e.g., carbon taxes) and behavioral changes (e.g., ending automobility, vegetarian diets) to avert disaster. Using novel graphic techniques, ‘After the Warming’ told a compelling long arc story with foci including (a) the historical contingency of civilization upon climate stability, (b) the relationship between fossil fuels, industrial production and climate change, (c) the rise of climate science via efforts like the Keeling curve and Antarctic ice core studies and (d) a fictional mitigation process in which a UN-orchestrated process used taxes and binding emissions targets reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 75% in advanced countries by 2030. The narrative structure of ‘After the Warming’ encouraged recognition that solutions to climate change lay well within the grasp of the international community even in 1990. Its mitigation narrative had, especially in retrospect, a utopian character, overemphasizing rational self-interest as a motivation to action as well as the capacity of nations to prioritize international cooperation over competition.

In ‘After the Warming’, as elsewhere in the early decades of climate communication, the melting of the cryosphere per se is given relatively minor attention, limited to a few brief mentions related to sea level rise, disrupted ocean currents and freshwater availability. Where attention was paid, it was paid principally to ice caps rather than glaciers. It was not until the 2000s that a consistent visual language of melting glaciers came to occupy a greater role in climate communication.

2.2. Spectacles of melting glaciers

O’Neill and Smith (Reference O’Neill and Smith2014) show that the late 1990s were when environmental organizations like Greenpeace first began to use images of cracking ice shelves and melting glaciers as representative images of climate change creating ‘a visual decoding which sees visualized landscapes as representations of (threatened) nature’. A similar analysis of environmental campaigns in 1990s and 2000s by Manzo concluded that ‘the dominant iconography of climate change is arguably melting glaciers’ or a combination of polar bears and melting ice. The vulnerability of glaciers and polar bears generated charismatic images but also concerns that human stakes of Arctic warming were being downplayed as though only losses to nature were unfolding (Manzo, Reference Manzo2010).

The 2000s marked a decisive surge in climate media in the wake of the unprecedented popular and commercial success of An Inconvenient Truth (2006), directed by Davis Guggenheim and featuring former US Vice President Al Gore. While not exclusively focused on the cryosphere, the film used before and after images of glacial melt, time-lapse images of glacial retreat, dramatic footage of Jakobshavn Glacier ‘exploding’ during a heat wave and other similar visual techniques to help anchor glacial melt as a potent symbol of climate disruption. The film helped establish melting glaciers as a charismatic spectacle and a form of visual proof to buttress the film’s argument for the acceptance of rapid and ambitious climate mitigation measures. As Doyle writes, ‘Images of melting glaciers dominate the pictorial language of climate change, powerful symbols of a fragile earth at risk from the impacts of climate change’ (Doyle, Reference Doyle2007). The film’s success—two Academy Awards and gross revenue of nearly $50 million worldwide—demonstrated that documentaries could bridge scientific credibility and popular storytelling to mobilize climate concern.

An Inconvenient Truth also pioneered the interweaving of personal life transformation narratives with the witnessing of climate change in the natural landscape. This model was developed further by Jeff Orlowski’s Chasing Ice (2012), which followed environmental photographer James Balog and his team as they undertook the Extreme Ice Survey, a multiyear photographic project aimed at documenting the melting of glaciers across the Arctic and other remote locations. The film offered unprecedented visual documentation of glacial change. Over a period of several years, Balog and his team deployed time-lapse cameras across Greenland, Iceland, Alaska and Montana, often braving extreme weather and difficult terrain. These cameras captured images at regular intervals, which were later compiled into sequences showing dramatic glacial retreat over relatively short periods. This approach made a unique contribution to climate communication, transforming abstract scientific models into observable visual phenomena. The film’s most iconic sequence captured the calving of the Jakobshavn Glacier in Greenland, where a chunk of ice roughly the size of Manhattan broke off into the sea. This footage, both awe-inspiring and unsettling, creates a visceral demonstration of climate instability, an example of what Bennett terms ‘Anthropocene ruin aesthetics’ (Reference Bennett2020). The film’s aesthetic—hauntingly beautiful shots of collapsing ice cliffs juxtaposed with the stark admissions of disbelief by Balog himself—humanized the scale and immediacy of the crisis. It powerfully illustrates how the integration of science, storytelling and visual media can enhance environmental awareness (Wang and others, Reference Wang, Corner, Chapman and Markowitz2018).

The 2010s saw several other films building upon the spectacular visual techniques of Chasing Ice, yet exploring different themes related to the loss of glaciers and their human impacts. Luc Jaquet’s La Glace et le Ciel (Ice and Sky, 2015) also centered the life of a scientific pioneer—glaciologist Claude Lorius—in its narrative. National Geographic’s The Last Ice (2020) offers similarly dramatic ice imagery but in service of a story about Inuit adaptation to climate change. HBO’s Ice on Fire (2019) featured Leonardo DiCaprio as narrator and emphasized the technological innovations that could help reverse climate change.

As compelling as spectacular images of glacial retreat and collapse may be, a limitation of this approach is that spectacle also creates detachment and can abet passivity from a viewing perspective (Debord, Reference Debord2012). The massive scale of glacial movements at sites like Jakobshavn can similarly suggest a process beyond any possibility of human control, even if its anthropogenic influence is acknowledged. Several studies have shown that while films such as Chasing Ice and An Inconvenient Truth increased awareness and temporary shifts in attitudes and behaviors among their audiences, the effects were short-lived and long-term attitude change and behavioral transformation were inconsistent (Cook, Reference Cook2016).

One response to this problem has been a turn toward experimentation with more immersive kinds of media. The 2017 New York Times Antarctica series is one example of this approach, as is the 2018 Frontline series, Greenland Melting. Both projects are advertised as ‘virtual reality’ since the embodied nature of VR fosters a sense of presence and emotional proximity otherwise difficult to achieve through conventional video and film. However, in actuality, these projects are better described as 360° photography, allowing a viewer to pivot viewpoint but not to move through a landscape, limiting their capacities of embodiment. Still, these experiments demonstrate that opportunities exist to create richer multimedia experiences that mirror immersive experiences such as ice cave tourism in countries like Iceland and Norway.

Another response has been to rescale visual documentary work toward more intimate levels of interaction between humans and glacial landscapes. The film Rockies Repeat (2021), directed by Caroline Hedin, follows a team of Indigenous and settler artists as they trek into the Canadian Rockies to reinterpret the work of early Banff painter, Catharine Robb Whyte. Along the way, the artists endure the precarity of climate change—record-breaking temperatures, horizons obscured by wildfire smoke, and an unrecognizable glacial landscape—permitting the filmmakers to offer what they describe as ‘a heartbreaking meditation on a shifting sense of place’.

Ice Edge—The Ikaaġvik Sikukun Story (2022) highlights the possibilities of intercultural filmmaking of cryospheric diminishment, documenting a multiyear sea ice research project based in Kotzebue Sound in northwest Alaska. Guided by an Indigenous advisory council of Elders, the project couples state-of-the-art geophysical observations from unoccupied aerial systems with a community-engaged research approach to bridge scientific and Indigenous understanding of sea ice change in the Alaskan Arctic. The film’s emphasis on a community-centered ‘holistic view’ on adaptation to ice loss marks a tonal and thematic departure from the often distancing and abstract spectacles of melting glaciers documented above.

2.3. Efforts to raise climate awareness via fiction

While nonfiction media has been the primary mode of addressing the melting cryosphere, it is worth briefly recognizing media efforts using fiction as a means for raising climate awareness. Films such as The Day After Tomorrow (2004, dir. Roland Emmerich) and Snowpiercer (2013, dir. Bong Joon-ho) dramatized abrupt climate change catastrophe through fantastical depictions of freezing cities and glacial advance, often criticized by scientists for inaccuracies but lauded by scholars for their mythic and affective power. These narratives, though hyperbolic, often succeed in communicating the existential stakes of inaction. More recent projects like Netflix’s climate allegory Don’t Look Up (2021, dir. Adam McKay) and especially the Apple TV+ series Extrapolations (2023, dir. Scott Z. Burns), further develop the melting cryosphere as a symbol of irretrievable loss, colonial violence and temporal acceleration. Such works effectively highlight the affective dimension of climate change—grief, guilt, anxiety—often absent from scientific discourses but central to public engagement.

The burgeoning field of climate fiction or ‘cli-fi’ has also yielded a number of novels exploring themes related directly or indirectly to the cryosphere. Laline Paul’s The Ice (2023) is a thriller set in a future where Arctic sea ice has entirely melted, opening a lawless and lucrative polar frontier for business and tourism. More commonly, cli-fi novels focus less on ice loss per se than on impacts such as sea-level rise (e.g., Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140 and Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Wind Up Girl) and consequences of hydrological disruption such as catastrophic drought (Claire Vaye Watkins’ Gold Fame Citrus and Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife). These narratives are often structured as mysteries or thrillers and these popular genre motifs can draw readers who might not otherwise engage with climate science. Fiction has been shown to increase readers’ empathy when they form an emotional connection with the narrative (Bal and Veltkamp, Reference Bal and Veltkamp2013), so the potential of fiction as a tool of climate communication should not be discounted. However, it must be used cautiously. Even when projects are built upon substantial verifiable scientific research (e.g., Robinson’s Ministry for the Future), the fictional approach, like the spectacular approach, can create an experiential buffer between the narrative experience and the real-world phenomenon.

Moreover, there is a recognized hurdle in translating climate media consumption into effective environmental action (Moser and Dilling, Reference Moser and Dilling2012). Social media experiments like climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe’s ‘Global Weirding’ YouTube series allow for short-form educational content with more capacity for viewer feedback (see also, e.g., Bhattarai, Reference Bhattarai2024). Instagram and similar platforms have also created lateral communicative pathways for polar and glacier researchers, citizen scientists and other interested parties to share their cryospheric engagements in real-time with the opportunity for conversation and feedback.

A less conventional development in climate communication concerning vanishing glaciers over the past 5 years has been efforts to explore collaborative performances as a medium for climate messaging.

3. The turn toward performance and ritual in documenting vanishing glaciers

3.1. Antecedents in eco-performance and ritual

Performance, in its broadest sense, includes theater, public demonstrations, street art, dance and participatory installations. Its practice is inherently relational and often impermanent, emphasizing presence and embodiment. Performance scholar Diana Taylor (Reference Taylor2003) distinguishes between the ‘archive’ (authorized documents) and the ‘repertoire’ (embodied practice), highlighting the power of live performance to transmit knowledge through action and interaction. This distinction is helpful for expanding the scope of climate communication; while the archive can provide empirical data about climate change, the repertoire invites audiences to feel and participate in the ecological issues being presented as a way of strengthening their epistemic engagement. Such performances can generate liminal spaces where participants momentarily step outside ordinary experience and confront environmental realities in dramatic, embodied and affective ways (Turner, Reference Turner1969).

Theater has long featured performances with environmental themes (e.g., Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People [Reference Ibsen and Archer1890]). Yet, according to Chaudhuri, ‘The scale and complexity of climate change, as well as its often incremental and unspectacular nature, pose formidable obstacles to dramatic representation.’ (Chaudhuri, Reference Chaudhuri2015). Contemporary eco-theater groups like Superhero Clubhouse have responded by embracing complexity as a core value of eco-theater,

Earth and the crises we face contain infinitely complex relationships that are often chaotic and contradictory. Eco-Theater reflects these complexities: We make performances using Impossible Questions, never assuming we know the right answer, leaving room for ideas we can’t yet imagine. (https://www.superheroclubhouse.org/what-is-ecotheater/)

Through its public outreach programs like the Big Green Theater, Superhero Clubhouse seeks to foster climate and environmental justice education, gaming and co-creation programs throughout the Hudson Valley bioregion that bring students into collaborative relationships with scientists and performers.

Such programs bring eco-performance into closer alignment with ritual. Ritual, often seen as a traditional or religious practice, has been reimagined by eco-artists and activists as a method of environmental engagement. Rituals can frame ecological issues as moral and spiritual concerns, not just scientific or political ones. They can promote a sense of connection to the Earth, the sacredness of non-human life, and the cyclical temporality of natural systems (Abram, Reference Abram1997).

A good example related to the cryosphere is Olafur Eliasson’s Ice Watch project (2014) in which massive chunks of glacial ice from Greenland were transported to major European cities like Copenhagen, London and Paris. The ice blocks were arranged there in public spaces in the rough shape of a clock face. Visitors could see, touch, and hear the ice melting. As the ice melted over several days, the performance created a powerful sensory and spatial metaphor for climate change—one that could be experienced in an embodied way. A longer-term version of this idea is the traveling research and theatrical project The Arctic Cycle, led by Chantal Bilodeau (Reference Bilodeau2023), which uses playwriting and performance to explore the human dimensions of climate change in Arctic regions. Through research, storytelling and dramatization, the project engages climatological phenomena that may seem remote, particularly to audiences in the urban Global North and seeks to make ecological crises like melting glaciers seem less distant. Bilodeau counsels the need to ‘decenter humans’ in climate messaging as a way of addressing human self-importance as a key Anthropocene driver.

The mobilization of ritual to address ecological deterioration includes movements like the Dark Mountain Project, a project begun in 2009, which incorporates ritualized gatherings, myth-making and storytelling to address ecological collapse (Kingsnorth and Hine, Reference Kingsnorth and Hine2009). Dark Mountain publications like Stephanie Krzywonos’s meditation on the fate of Thwaites Glacier, ‘The Unfathomable Heart’ (2022), directly engage issues of cryospheric destabilization. Yet, rituals allow for the direct expression of ecological mourning—a vital emotional register in climate communication. The use of ritual to inspire ecorestoration and overcome ecoanxiety has roots in the environmental philosophy of figures like Gretel Van Wieren (Reference Van Wieren2008) and Joanna Macy (Reference Macy2021). One notable example is the ‘Council of All Beings’ ritual of 1986, where Macy and John Seed created a ritual exercise where participants sought to embody non-human beings to undermine anthropocentrism and better understand non-human perspectives and needs (Seed and others, Reference Seed, Macy, Fleming and Naess1988). More recent climate grief rituals facilitated by activist groups like Extinction Rebellion incorporate elements of lamentation, symbolic burial and silence to process ecological loss (Pike, Reference Pike2024). These acts, though performative, are not merely symbolic; they help participants process grief, guilt and hope, emotions that rarely find prominence in the archive.

One reason ritual and performance are gaining traction in environmental movements is the growing recognition of emotion’s role in climate communication. Brosch writes that

The affective responses people experience toward climate change are consistently found to be among the strongest predictors of risk perceptions, mitigation behavior, adaptation behavior, policy support, and technology acceptance. (Brosch, Reference Brosch2021)

Scholars like Ray (Reference Ray2020), building on Macy and Johnstone (Reference Macy and Johnstone2012), argue moreover that addressing emotions like fear, guilt and despair is critical to overcoming climate paralysis. Ritual and performance provide structured spaces where these complex feelings can be acknowledged, shared and transformed (Craps, Reference Craps and Kaplan2023).

Given these antecedents, it seems logical that the ritual engagement of melting glaciers would become a new kind of eco-performative practice.

3.2. Glacier rituals and cryospheric commemoration as climate messaging

The concept of rituals honoring glaciers is not itself novel. There is substantial ethnographic evidence that mountain cultures across the world developed ethical and spiritual practices honoring glaciers and/or the spirits believed to reside within them (e.g., Allison, Reference Allison2015; Gagné, Reference Gagné2019). Yet, until 2019, there had been no effort to create a ritual specifically focused on the disappearance of a glacier.

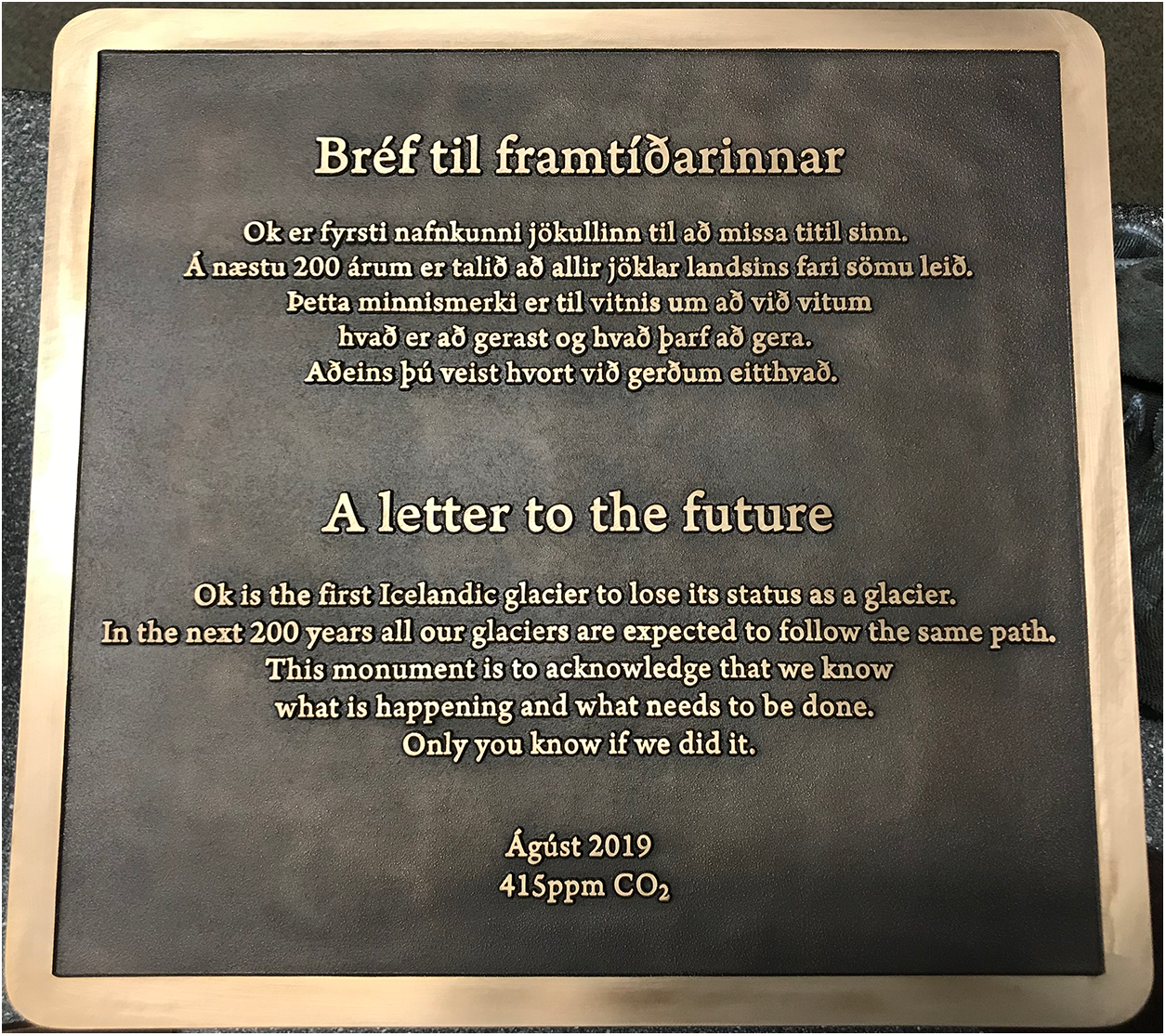

The idea of creating a funeral for a vanished glacier took shape as the authors created a documentary film about the first-named Icelandic glacier (Okjökull) to fall victim to climate change, Not Ok: a little movie about a small glacier at the end of the world (2018; Howe and Boyer, Reference Howe and Boyer2020). The filmmaking process involved interviews with Icelanders about the emotional meaning of ice loss. These conversations led to the concept for a ceremonial ‘un-glacier tour’ to the former home of Okjökull as well as the installation of a memorial plaque, with words provided by Icelandic writer Andri Snær Magnason (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Okjökull memorial plaque, ‘A Letter to the Future’.

The form of the ‘letter to the future’ imagined an intergenerational conversation over responsibility and stewardship of the cryosphere. The funeral itself functioned as a performative act of ritualized ecological grief. The mood of the ceremony was not itself grim because of its emphasis on building community among those, to cite the film, ‘for whom the death of a glacier is a real death’. The extensive international media coverage the plaque and funeral received demonstrated how ritual performance can scale environmental messages to global audiences. The creative team explained,

Ritual has always served humanity as a way of generating community and solidarity in times of existential transition. Facing fundamental threats like climate change and species extinction, we have never needed human and more-than-human solidarity more than we do now (Howe and Boyer, Reference Howe and Boyer2024).

In the years that followed, several more glaciers received funerals or commemorative rituals (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2022). A month after the installation of the Okjökull memorial, a group in Switzerland performed a funeral for the Pizol glacier. The month after that, a plaque was laid for the Pyrenees glacier d’Arriel. In 2020, a group of mourners gathered to commemorate the death of Oregon’s Clark glacier. And, in 2021, the Mexican glacier Ayoloco was commemorated with a plaque. The most recent glacier funeral was held in 2025 for the Nepalese glacier, Yala. Interestingly, the memorial texts for Yala, d’Arriel and Ayoloco resembled Magnason’s text for Okjökull quite closely, suggesting that Okjökull’s memorial is serving as a template of sorts for other glacier memorials.

As efforts to commemorate glaciers with funerals and similar rituals have expanded in the past 5 years, the authors have created an Internet-based platform, the Global Glacier Casualty List, that allows glaciologists and other parties invested in the cryosphere to tell stories about specific glaciers that have either already disappeared or that can be projected to disappear in the next 20 years. Global Glacier Casualty List stories seek to balance the communication of reliable scientific information about these glaciers with information about the human impacts of their loss, including reduced freshwater availability, economic disruptions and the loss of cultural heritage as the landscape transforms (Howe and Boyer, Reference Howe and Boyer2025). Coordinated with the launch of the Global Glacier Casualty List, the project organizers created a ‘Glacier Graveyard’ in Seltjarnarnes, Iceland (see Fig. 2) featuring headstones crafted of ice for each of the 15 glaciers featured in the platform launch. The platform now features 36 glaciers with ten additional stories in development.

Figure 2. Glacier graveyard, Seltjarnarnes, Iceland, August 17, 2024.

The Global Glacier Casualty List functions as a site of memory and advocacy. It also serves as a methodological intervention, seeking to incorporate social dimensions of vulnerability and loss into glaciological knowledge production. The Global Glacier Casualty List operates both as a critical data assemblage and a call to ethical reckoning, reminding scholars and policymakers alike that each data point in glacier science may also represent a life, a livelihood, or a way of being in the world. Its significance extends beyond academia, offering a public-facing narrative that humanizes climate change and underscores the urgency of mitigation and justice-oriented adaptation strategies.

4. Conclusion

What comes next in the field of climate communication concerning vanishing glaciers is unknowable. But this review of communicational efforts over the past several decades suggests that scientists, social scientists and artists will continue to innovate as new media and ecological circumstances create new challenges and opportunities for climate messaging and action. As the Okjökull memorial, Global Glacier Casualty List and Glacier Graveyard evince, collaborative partnerships are greater than the sum of their parts, and so collaborative communication should be encouraged above all.

Significant obstacles remain. All climate communication efforts face barriers created by rapid, decentralized information flows and aggressive disinformation efforts, some linked to incumbent energy interests seeking to slow down or avoid energy transition (Oreskes and Conway, Reference Oreskes and Conway2010; Boyer, Reference Boyer2023). Similarly, all climate communication faces risks of narrative fatigue, emotional saturation and apocalyptic framing, particularly when audiences lack the resources or agency to act on the information presented. These critiques point to the need for more ethical, inclusive and hopeful climate storytelling that bridges urgency with empowerment. Performance and ritual also offer promising pathways toward more immersive and experiential modes of communication that can help participants to feel more connected to environments and anthropogenic processes like deglaciation. In an age of climate emergency, the challenge for media makers is not just to show ice melting, but to help build the political, emotional and imaginative capacities needed to stop it.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge their many collaborators in the Global Glacier Casualty List project. For a full list, see: https://ggcl.rice.edu/.