Introduction

Variationist sociolinguistics has long resisted incorporating observations about lexis into theories of language variation and change. This is, to a large extent, predicated on a belief exemplified by, among many others, William Labov, one the founders of our field, in his 2012 book (Labov, Reference Labov2012:17):

There is of course a great deal of fluctuation in vocabulary. We all find it interesting to learn that what is called soda in one place is called pop in another place, and coke in another. Yet the change of one word does not tell us much about change in another, and the long list of words that differ from one place to another does not form a coherent pattern or give us much insight into the machinery of speaking and listening.

From this perspective, lexical variation is seen as defying systematic description and thus falling outside the scope of sociolinguistic theory. Although far from a consensus, this assumption appears to be tacitly accepted across much of the field and has been echoed by many other prominent sociolinguists, including Adams (Reference Adams, Holmes and Hazen2014:164), who wrote that “words do not behave systematically,” and Trudgill (Reference Weiner and Labov1986:25), who wrote that lexical variation is “(mostly) non-systematic.” Sociolinguists do not doubt that the use of individual lexical items is socially patterned (although, see Nagy, Reference Nagy2011); they doubt whether these patterns are systematic, recurring across lexical items, at least in ways that are relevant to our understanding of the basic mechanisms of language variation and change more generally. Each lexical item is assumed to show its own pattern, reflecting the unique history of that word or sign, as opposed to reflecting general sources of sociolinguistic variation.

While the study of lexis has always been central to dialectology, the relative lack of engagement with lexical variation in variationist sociolinguisticsFootnote 1 can be clearly seen in the publication patterns of this journal, Language Variation and Change—the journal of record in our field. For example, between 2012 and 2023, 177 research articles were published. Of these articles, only 10 (6%) were on lexis, compared to 98 (55%) on phonetics and phonology, and 58 (33%) on morphology and syntax (see the Appendix).Footnote 2 Of the 10 articles on lexical variation, there were four articles on quotatives (D’Arcy, Reference D’Arcy2012; Denis et al., Reference Denis, Gardner, Brook and Tagliamonte2019; Labov, Reference Labov2018; Louro et al., Reference Louro, Collard, Clews and Gardner2023), as well as articles on loan word development (Poplack & Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2012), the grammaticalization of variants of finish in Auslan (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Cresdee, Schembri and Woll2015), change over time in the function of key in English (De Smet, Reference De Smet2016), variation in adverbs of evidentiality in English (Tagliamonte & Smith, Reference Takano2021), variation in lexis and other levels of linguistic analysis in Japanese dialects (Takano, Reference Thibault2021), and change from Old to Middle English in the use of third-person adult male referents (Stratton, Reference Stratton2023).

Underlying the general assumption that lexical variation is asystematic, there are three primary challenges, in our view, that have limited the study of lexis within the variationist paradigm.

The first challenge is methodological. Although collecting data through sociolinguistic interviews (Labov, Reference Labov1972a, Reference Labov, Baugh and Sherzer1984) has been highly productive for the study of variation at other levels of linguistic analysis, sociolinguistic interviews do not generally allow for the systematic analysis of variation in vocabulary. While acknowledging the high levels of interest in lexical variation and the centrality of the social function of lexis in communication, Labov himself acknowledged this methodological challenge (Labov, Reference Labov, Bailey and Shuy1973:340) (see also Weiner & Labov, Reference Weinreich, Labov and Herzog1983):

The reason for this neglect is certainly not a lack of interest, since linguists like any other speakers of a language cannot help focusing their attention on the word, which is the most central element in the social system of communication. It is the difficulty of the problem, and its inaccessibility to the most popular methods of inquiry, which is responsible for this neglect.

Compared to most speech sounds and many grammatical constructions, the vast majority of lexical items, particularly those in open-class parts-of-speech (i.e., content words), are far too uncommon to be studied in collections of sociolinguistic interviews or even traditional multi-million word corpora of natural language. Typical sociolinguistic datasets simply do not allow for most lexical items to be observed with sufficient frequency to allow for lexical variation to be analyzed in the quantitative detail demanded in variationist sociolinguistics, precluding analysis of lexical variation at a systemic level. This issue can be overcome, in part, by analyzing relatively high-frequency words, such as intensifiers (e.g., Ito & Tagliamonte, Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003) or by conducting/analyzing a vast number of interviews (e.g., Tagliamonte & Jankowski, Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2025). However, the latter is not feasible for most researchers who are investigating variation and change across the lexicon. Indeed, when Labov has engaged with lexical variation, he has done so not using the Labovian sociolinguistic interview (e.g., Labov, Reference Labov1972a, Reference Labov, Baugh and Sherzer1984) but by engaging with alternative sources of data, such as questionnaires/direct questions (Labov, Reference Labov and Davis1972b; Labov et al., Reference Labov, Ash and Boberg2006)Footnote 3 and advertisements (Labov, Reference Labov, Britain and Cheshire2003).

The second challenge is also methodological. The analysis of lexical variation is often incompatible with standard approaches to the measurement of sociolinguistic variation (see Durkin, Reference Durkin2012; Labov, Reference Labov1978; Lavandera, Reference Lavandera1978). It can be especially difficult to reconcile lexical variation with the notion of the “sociolinguistic variable” as “alternative ways of ‘saying the same thing’” (Labov, Reference Labov1969:738) because all lexical items are ultimately meaningful, unlike phonetic and phonological variables. Every lexical item tends to encompass a range of senses and functions, each denoting a distinct set of possible meanings.Footnote 4 In other words, there are no true synonyms (Cruse, Reference Cruse1986; Leclercq & Morin, Reference Leclercq and Morin2023). Furthermore, the full set of possible lexical items that can be used to express a given concept in a particular context can be enormous and thus difficult to enumerate (Kretzschmar, Reference Kretzschmar2009), while many words do not appear to be in alternation with any other words (Grieve, Reference Grieve2023). For these reasons, when analyzing variation and change in lexis, especially compared to phonetics and phonology, it is generally much more difficult to meet what is known as the “principle of accountability” (Labov, Reference Labov1972a), which insists that all variants of a sociolinguistic variable be considered.Footnote 5

The third challenge is theoretical: observations of lexical variation are difficult to integrate into sociolinguistic theory. Lexical variation is often closely related to variation in the referential meanings words express, which is quite different from variation in phonetics and phonology, for example, where the alternation between variants can be divorced from referential meaning. Lexical variation is therefore seen as being distinct from structural variation—related to language content rather than language form—and consequently asystematic and therefore on the periphery, or even outside the scope, of variationist theory, as Labov claimed in the quote at the start of this paper (Reference Labov2012:17). There is, however, a lack of empirical evidence to support this theoretical assumption, given the inherent methodological challenges associated with the analysis of lexical variation, as discussed above, which make the systematic observation and measurement of lexical variation so difficult within the traditional variationist paradigm. In this case, it seems that methodological challenges are driving the development of theoretical assumptions and not the other way around.

In fact, there is increasing empirical evidence for both the systematicity of lexical variation and its relevance to our general understanding of language variation and change. While there has always been some research on lexical variation in sociolinguistics (e.g., Labov, Reference Labov and Davis1972b; Osser & Endler, Reference Osser and Endler1970), over the past two decades there has been a dramatic increase in the amount of research on lexical variation—not only in adjacent fields, but on the periphery of variationist sociolinguistics, too. In general, we believe research on lexical variation has primarily come from five main sources, all of which were made possible, to an extent, by moving away from the sociolinguistic interview as the main source of data, often taking advantage of new methodological opportunities for the collection of language data, especially by compiling increasingly large corpora of social media and by delivering surveys and other tasks via crowdsourcing platforms to large numbers of informants online.

First, research in historical sociolinguistics, which is also generally conducted within the variationist paradigm, has considered change over time in word alternations, primarily focusing on function word alternations (e.g., Nevalainen & Raumolin-Brunberg, Reference Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg2016; Romaine, Reference Romaine1982), although several studies in this tradition have focused on the use of high frequency content words, as well (e.g., D’Arcy, Reference D’Arcy2017; Stratton, Reference Stratton2022). As noted above, two exceptions that have been published in this journal are De Smet’s (Reference De Smet2016) analysis of change in the use of the word key from a noun into adjective in English between the 1970s and 1990s, and most recently Stratton’s (Reference Stratton2023) analysis of change over time in the use of the nouns man and wer to refer to human males in English over 600 years. Notably, research in historical sociolinguistics has generally been based on corpora of historical written documents, although, because these corpora are still relatively small, analyses must generally focus on high frequency lexical items.

Second, over the past decade, there has been a rapid increase in research in computational sociolinguistics in both sociolinguistics (Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Hovy, Kendall, Nguyen, Stanford and Summer2023) and natural language processing ([NLP] Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Doğruöz, Rosé and De Jong2016). These studies are characterized by the analysis of very large datasets collected online, including corpora of social media (Eisenstein et al., Reference Eisenstein, O’Connor, Smith and Xing2014) and crowd-sourced surveys (Britain et al., Reference Britain, Blaxter and Leemann2020). Lexis has received more attention than any other level of linguistic analysis in this research, in part because big data generally facilitates the systematic observation of variation in a far larger sample of words than is otherwise possible. In most cases, this research has focused on the analysis of individual words, as opposed to lexical alterations. Notably, in NLP, much of this research has been pursued with the goal of increasing fairness in artificial intelligence systems, a topic that is now becoming especially important with the rise of large language models.

Third, research on the sociolinguistics of sign languages has naturally placed great emphasis on lexical variation, as this level of analysis is especially prominent in sign languages (Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Bayley and Valli2001; Ma, Reference Ma2020; Mudd et al., Reference Mudd, Lutzenberger, de Vos, Fikkert, Crasborn and de Boer2020). For example, Johnston et al. (Reference Johnston, Cresdee, Schembri and Woll2015), which was published in this journal, found evidence for grammaticalization of signs used to mean finish in Auslan, based on an analysis of variation in the grammatical function, the semantics, and the formational features of this sign in a corpus of elicited conversational data. Notably, given challenges in creating large-scale datasets of sign languages (Fenlon & Hochgesang, Reference Fenlon and Hochgesang2022), rather than collecting data through relatively informal sociolinguistic interviews, sociolinguists who study lexis in sign languages may follow more formal protocols, often involving the direct elicitation of forms of interest in relatively controlled conditions suitable for video recording.

Fourth, research has been conducted at the intersection of variationist sociolinguistics and cognitive linguistics. Research in cognitive sociolinguistics (Geeraerts et al., Reference Geeraerts, Kristiansen and Peirsman2010; Kristiansen & Dirven, Reference Kristiansen and Dirven2008; Kristiansen et al., Reference Kristiansen, Franco, De Pascale, Rosseel and Zhang2022) has often focused on the systematic, structural analysis of lexical variation (e.g., Geeraerts et al., Reference Geeraerts, Speelman, Heylen, Montes, De Pascale, Franco and Lang2024; Robinson, Reference Robinson2010). For example, Geeraerts (Reference Geeraerts1997) outlined the role of prototypicality in processes of diachronic lexical change. Research in cognitive sociolinguistics also tends to draw on increasingly large corpora of natural language harvested online for the analysis of lexical variation (e.g., Geeraerts et al., Reference Geeraerts, Speelman, Heylen, Montes, De Pascale, Franco and Lang2024; Gries, Reference Gries2013).

Finally, a growing body of lexical research has been conducted broadly within variationist sociolinguistics. Much of this research has investigated variation on the edge of grammar and lexis based on the analysis of high frequency words, generally based on relatively large collections of sociolinguistic interviews collected over time. In many cases, these studies have focused on function word alternations (e.g., Cheshire & Fox, Reference Cheshire and Fox2009; Tagliamonte & Baayen, Reference Tagliamonte and Brooke2012), as function words are both sufficiently frequent to be observed in relatively small datasets and are generally understood to involve the expression of grammatical information, as opposed to content word alternations. Researchers in this tradition have also used similar approaches to study a small number of relatively highly frequent content word alternations in corpora, including quotatives (e.g., Buchstaller et al., Reference Buchstaller, Rickford, Traugott, Wasow and Zwicky2010; D’Arcy, Reference D’Arcy2012; Denis et al., Reference Denis, Gardner, Brook and Tagliamonte2019), adjectives of strangeness (Tagliamonte & Brooke, Reference Tagliamonte and D’Arcy2014), words for an evening meal (Jankowski & Tagliamonte, Reference Jankowski and Tagliamonte2019), third-person male referents (Franco & Tagliamonte, Reference Franco and Tagliamonte2021), and large clusters of lexical items (Poplack et al., Reference Poplack, Sankoff and Miller1988). Other researchers have utilized non-vernacular oriented methods such as questionnaires (e.g., Labov, Reference Labov and Davis1972b; Osser & Endler, Reference Osser and Endler1970) or repurposed dialectological survey data (e.g., Burkette, Reference Burkette2012, Reference Burkette2017; Johnson, Reference Johnson1993; Montemagni & Wieling, Reference Montemagni, Wieling, Côté, Knooihuizen and Nerbonne2016) to highlight the social distribution of lexical items according to dimensions such as age, socioeconomic class, and gender.

Developing from within this tradition, third-wave sociolinguists have also often taken lexical variation into consideration (e.g., Bucholtz, Reference Bucholtz and Jaffe2009; Denis, Reference Denis2021; Kiesling, Reference Kiesling2004), in part due to the emphasis on understanding the expression of identity through language variation. Speakers undeniably express social meaning through word choice, which is often highly socially salient. Third-wave sociolinguistics has also challenged the principle of accountability, with Campbell-Kibler (Reference Campbell-Kibler2011) arguing that it is the individual variant, as opposed to the set of variants that constitutes a sociolinguistic variable, that carries social meaning. Notably, research in this tradition is increasingly based on new approaches to fieldwork, including moving online, where the expression of social meaning is of central importance. For example, among many other features, Ilbury (Reference Ilbury2020) showed how certain lexical features originating from African American Language (e.g., bae, yass) are used by gay British men on Twitter to index specific social identities.

Building on recent research on lexical variation, the goal of this paper is therefore to affirm the general importance of this research to our understanding of language variation and change by challenging the notion that lexical variation is unsystematic and therefore less of a priority for variationist sociolinguistics. To support this claim, we consider three empirical studies that show how lexical variation is richly patterned in a wide range of ways. These studies exemplify three of the traditions we have identified above—third-wave sociolinguistics, sign language sociolinguistics, and computational sociolinguistics. In each case, we discuss the primary results of these studies and how they can inform sociolinguistic theory in unique and important ways. We also stress how these studies have each adopted distinctive techniques for data collection and data analysis to overcome the methodological challenges that have previously limited research in this area. We then conclude this paper by claiming that lexical variation is not only systematically patterned, but that these patterns allow us to observe language variation and change from a unique and important perspective that must ultimately be accounted for by any comprehensive variationist theory, even if they challenge long held assumptions about the machinery of language variation and change.

Study 1: Anglo-Cornish dialect lexis

Our first study focuses on lexical variation in Anglo-Cornish, the variety of English spoken in Cornwall in the far southwest of Great Britain (Sandow, Reference Sandow2021, Reference Sandow2022, Reference Sandow2023, Reference Sandow2024a). In Sandow (Reference Sandow2024a), the four lexical variables—tourist, lunch box, woman, and walk—explored in this study were analyzed in the aggregate, highlighting systematic sociolinguistic patterns, such as associations of Anglo-Cornish variants with strong local identity and an inverted style pattern. The case-study that we present here focuses primarily on the first of these variables, tourist, as well as related processes of semantic change.

Methodologically, this study is based on a novel combination of tasks to elicit lexical data from 80 speakers. Spot-the-difference tasks (see Fig. 1) were employed to elicit a relatively casual speech style, while naming-tasks (see Fig. 2) elicited a relatively careful speech style. In the former, participants focused on task-completion, where task-completion was conditional on identifying and lexicalizing differences. In the latter, participants were informed that their word-usage was being observed, shifting their focus to their lexical choices. Accounting for stylistic variation provides insight into the perceptions of these forms, as well as broader insight into language ideology (Sandow, Reference Sandow2022). This combinatory method of eliciting lexical items at varying levels of attention means that we can observe lexical variation in the context of the attention-to-speech (Labov, Reference Labov1972a) model which has seldom been applied to words. In addition, to elicit information on semantic variation and change, Robinson’s (Reference Robinson2010) “who/what is [polysemous word]” elicitation tasks were employed. By asking for a referent, rather than a meaning, these tasks are less direct than asking for meanings explicitly. Here, semantic variants are defined as the same way of saying different things (see Robinson, Reference Robinson2010). These tasks ensure that it is clear where particular variants could occur, thus circumscribing the variable context and satisfying Labov’s (Reference Labov1972a) principle of accountability.

Figure 1. An example of the spot-the-difference elicitation tasks (from Sandow, Reference Sandow2021).

Figure 2. An example of a naming-task (from Sandow, Reference Sandow2021).

In this first study, the analysis of lexical variation provides insights into social attitudes at a more granular level than is generally possible through the analysis of other levels of linguistic analysis, making it possible to track the history of sociocultural changes through lexical variation. This duality of sociocultural and lexical change is evidenced in Cornwall by shifting attitudes toward tourism and the words that are used for tourists. As we see, accounting for changes pertaining to tourism and tourists in Cornwall alongside changes in the semantic domain of tourism in Cornwall allows us to better understand the actuation of these changes. This work builds on existing research that highlights the role of social, cultural, and attitudinal influences on the socially mediated incrementation of lexical change (e.g., Labov, Reference Labov and Davis1972b; Tagliamonte & Brooke, Reference Tagliamonte and D’Arcy2014; Tagliamonte & Jankowski, Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2025).

Tourism in Cornwall largely began at the turn of the 19th to 20th centuries, but there was a notable quantitative upturn in visitor numbers in the post-war years and then again in the 1960s (see Meethan, Reference Meethan and Voase2002:24). This nascent tourist industry, which now accounts for a greater proportion of Cornish economic output than any comparable United Kingdom region (Office for National Statistics, 2016), has had wide-reaching effects, including on the Cornish economy and language. Since the mid/late-mid 20th century, negative attitudes to tourism, particularly the ways in which it was perceived to be diluting traditional Cornish identity, have been evident (see discussion in Perry, Reference Perry1999).

In Cornwall, the Old English word emmet ‘ant’ has been retained but, with the rise in tourism, since at least the 1970s, it has also been used to mean ‘tourist.’ This polysemous state of affairs was induced by pejorative parallels being drawn between arthropods and the tourists who were increasingly visiting Cornwall in the post-war years and who were perceived to be red (due to sunburn on [overwhelmingly] white skin), to move in large groups, and to be seen only in fair weather. The semantic shift from ‘ant’ to ‘tourist’ can be seen in apparent-time, with the ‘ant’ sense being retained most by older middle-class speakers with a strong sense of local identity (for further detail, see Sandow, Reference Sandow2023). The shift away from this ‘ant’ sense, toward ‘tourist,’ is predicated upon a less than favorable attitude toward tourists, which can also be observed in the frequent collocates of emmet ‘tourist,’ such as fucking and bloody.

While many, particularly younger, Cornish people are keen to distance themselves from such discourses, which “other” tourists and non-Cornish people more broadly, it is perhaps surprising that there is no quantitative difference in the overall rates of use of emmet as a variant of tourist across apparent time. However, there are differences in the social factors that best account for variation among older and younger speakers. Within the category of older speakers, strength of local identity was the best predictor of the use of emmet, while socioeconomic class was a stronger predictor for younger speakers, with emmet being favored by those with a strong local identity in the older group and working-class speakers in the younger group.

This generational change must be understood within the context of broader changes in Cornish identity that are underway (see Sandow, Reference Sandow2024b). Older Cornish people primarily orient toward a type of Cornish identity that has been described as the “Industrial Celt” (Sandow, Reference Sandow2024b:201), characterized by an orientation toward Cornwall’s industrial and Celtic histories and a conceptualization of the Cornish people as Celtic and, consequently, non-English. By contrast, many, particularly younger, Cornish people orient to a “Lifestyle Cornwall” (Sandow, Reference Sandow2024b:201) version of Cornish identity which is predicated on an orientation to Cornish aesthetics, including its landscapes and seascapes, and conceptualizing Cornwall as a county of England, albeit a distinct one. This latter identity is also characterized by a mock-othering of the English while accepting, even embracing, tourism in Cornwall.

The specific indexicalities for emmet are clearly expressed in the following quote from a young man from Cornwall, highlighting the broader awareness of social meaning at the level of lexical variation found in this community:

Emmet is a word that is only likely to be used by Cornish people […] it is a pejorative word for tourists […] the sort of person who is likely to use this word is someone with an inherent dislike of outsiders and who feels threatened by influxes of tourism […] I think that if there was a class thing to it, it would probably be used more by working-class Cornish people. Gender, I don’t think it matters nor does age, I think it’s more of an identity thing, a national identity […] I associate this word with a slightly insular quality based on a dislike of others, in this case, tourists. It is reflective of a traditional attitude. I think people use it to advertise their Cornishness as a sort of Cornish badge of honour to dislike tourism. I don’t find it problematic but I know lots of people who do.

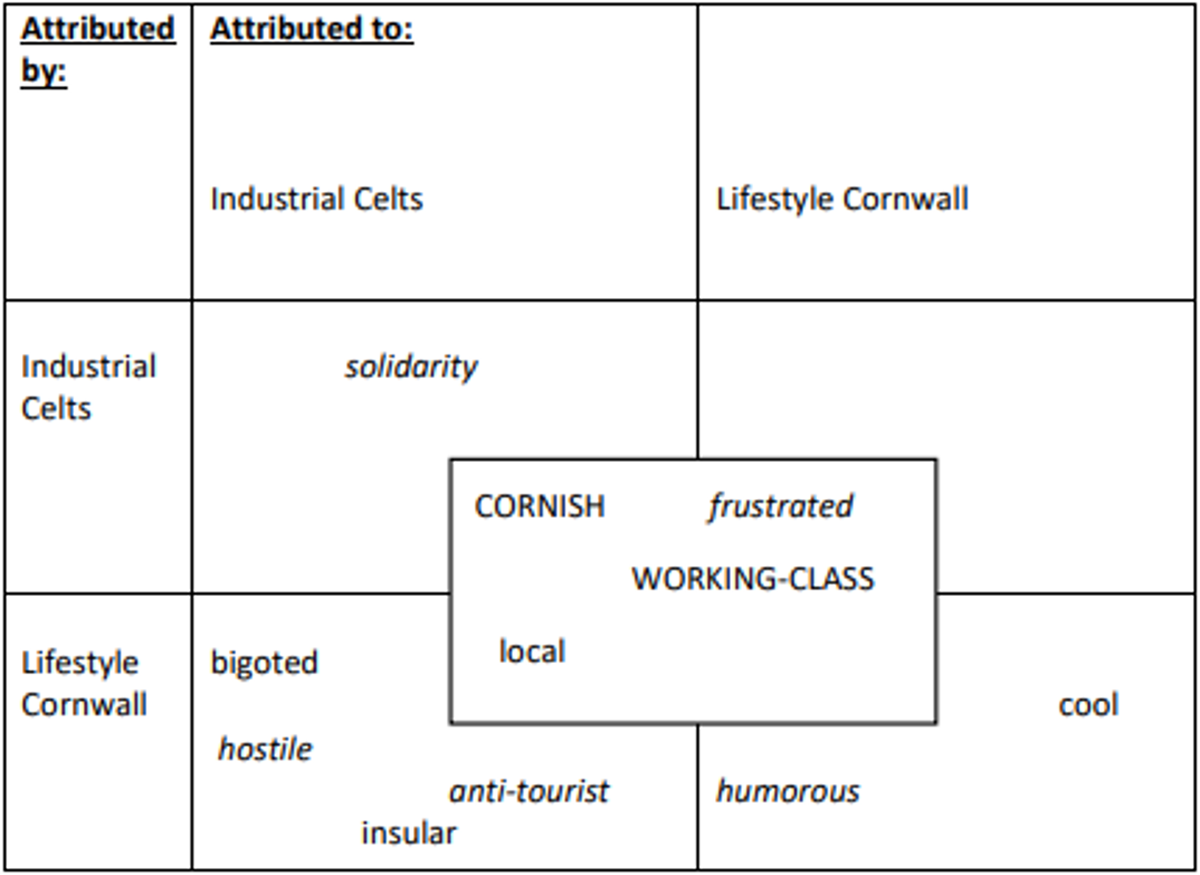

The majority of participants agreed on some core social meanings of emmet: it indexes Cornishness, frustration, localness, and working-classness. However, there was also considerable variation in the identities and stances associated with emmet. Industrial Celts perceived emmet to index solidarity, yet this same usage was perceived by those who orient toward a Lifestyle Cornwall identity as being bigoted, hostile, insular, and anti-tourist. While those who orient to Lifestyle Cornwall acknowledged such social meanings, many do use this word, often commenting that when they do so the butt of the joke are not tourists but other Cornish people who they perceive to be bigoted. Those who orient toward Lifestyle Cornwall are therefore likely to use emmet to index humorousness and a cool identity with their (Cornish and non-Cornish) peers. Thus, while many Industrial Celts use emmet to increase social distance between themselves and non-Cornish people, many who orient toward the Lifestyle Cornwall identity use the same word but with the inverse pragmatic function: to decrease the social distance between themselves and non-Cornish folk.

Overall, meta-linguistic commentaries from speakers therefore show that emmet has a rich and nuanced indexical field in Cornwall, as presented in Figure 3. Crucially, the indexical field highlights the ways in which the referential meaning of lexical items can bleed into the social meaning. This contrasts with the meaning of, for example, phonological variants, in which the relationship between the phonological form and the social meaning is generally assumed to be entirely abstract (although, see Eckert, Reference Eckert2017). The use of emmet to style a Cornish identity is evident from an inverted style pattern (cf. Labov, Reference Labov1972a): it is more frequent in careful (naming-task) as opposed to casual (spot-the-different task) speech. This highlights the way in which, while emmet is not typical of “vernacular” speech in Cornwall, it is utilized to do social identity work. This stylistic pattern, which challenges classic sociolinguistic theories of style, is shared with the three other variables analyzed in this study, highlighting a systematic nature to this cluster of lexical items (see Sandow, Reference Sandow2022).

Figure 3. Indexical field for emmet ‘tourist.’ Capital letters denote social groups. Regular text denotes persona types. Italics denote stances (from Sandow, Reference Sandow2021).Footnote 6

Ultimately, the sociocultural changes pertaining to tourists are also seen in the semantic field of tourism in Cornwall. Tourism in Cornwall can be reduced to three key stages: (1) an increase in tourism in the post-World War II years, (2) the subsequent development of negative affective stances toward tourism, and (3) more recently, a shift toward an acceptance of tourism. These stages each have a lexical analogue: (1) the semantic shift from emmet ‘ant’ to emmet ‘tourist,’ (2) the use of emmet to “other” tourists, and (3) the pragmatic shift in the function of emmet to mock the “other.” The lexical-social analogues provide explanation for why this change happened in this place, providing an explanation for the actuation of the semantic shift from ‘ant’ to ‘tourist,’ as well as the shift in its social meaning.

The combination of the socially-mediated incrementation and the degree of transparency and non-arbitrariness of the actuation of the changes presented in this case-study highlights the valuable insights lexis can facilitate in understanding sociocultural and attitudinal changes and vice versa. Indeed, it highlights the way in which lexical change provides a window into society. The findings also speak to the ways in which semantic change can drive changes in patterns of lexical alternation. These insights extend our understanding of processes of sociolinguistic variation and change which cannot be observed so clearly when focusing on other levels of linguistic analysis.

Study 2: Evidence of dialect leveling in British Sign Language

Our second study focuses on lexical variation in British Sign Language (BSL). Variation may occur in the sublexical structure of signs: signs consist of a combination of distinctive handshapes, locations on the signer’s body or in the space around the signer, and movements (e.g., Johnston & Schembri, Reference Johnston and Schembri2007). For example, studies of American Sign Language, Auslan in Australia, and New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL) have shown that the location of signs specified in citation form for a forehead location can vary, produced on locations lower on the head or body (Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Bayley and Valli2001; Schembri et al., Reference Schembri, McKee, McKee, Pivac, Johnston and Goswell2009). These patterns are partly driven by assimilation effects in connected signing: if other signs are produced at lower locations before or after the target sign, the target’s location also tends to be lower. This variation, however, also correlates with social factors, including gender, age, and region. For example, in Auslan, lowering was seen more often in younger women from urban centers (Schembri et al., Reference Schembri, McKee, McKee, Pivac, Johnston and Goswell2009). Variation may also occur in the grammatical organization of sign languages. For example, this includes variable presence of subject noun phrases. Like many spoken languages, most clauses in Auslan and NZSL narratives exhibit subject drop (McKee et al., Reference McKee, Schembri, McKee and Johnston2011), but this is conditioned by several linguistic factors, such as whether the referent of the noun phrase is the same as in the previous discourse, or whether there is evidence of English influence on other aspects of the clause structure.

Just like in spoken languages, variation and change in signed languages can thus be identified at all levels of analysis. Although there is interest in variation across all linguistic levels in sign languages, lexis is especially important, as our case-study illustrates. Before introducing this study, however, there are two important differences between lexical variation in spoken and signed languages that should be highlighted. The first relates to the origins of lexical variation in sign languages in the Global North, where schools for deaf children have been found to be the origin of regional variation and the key site for the transmission of sign language variants (Eichmann & Rosenstock, Reference Eichmann and Rosenstock2014; Quinn, Reference Quinn2010; Stamp et al., Reference Stamp, Schembri, Fenlon, Rentelis, Woll and Cormier2014). Because the majority of deaf children are born to hearing families (Mitchell & Karchmer, Reference Mitchell and Karchmer2004), schools for the deaf, which were often residential in the 19th and early 20th centuries, served as “speech communities” where deaf children learned and passed on sign languages, often from older to younger children outside of the classroom, as the language of instruction was often the majority spoken language of the region. It is also possible that minimal interaction between children at different schools allowed sign language variants to remain distinct from one another. When deaf children left school, the use of these school variants therefore became associated with the surrounding region (Sutton-Spence & Woll, Reference Sutton-Spence and Woll1999). In fact, Stamp et al. (Reference Stamp, Schembri, Fenlon, Rentelis, Woll and Cormier2014) described the use of regional variants in BSL as “school-lects” (for more discussion, see Quinn, Reference Quinn2010), reflecting the fact that schools may be a better predictor of regional variation than other social factors.

The second important difference is that regional variation has been found to occur primarily at a lexical level. Studies show that lexical variation in sign languages is systematically conditioned by a range of social factors, including age (Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Bayley and Valli2001), gender (Mudd et al., Reference Mudd, Lutzenberger, de Vos, Fikkert, Crasborn and de Boer2020), region (Ma, Reference Ma2020), and ethnicity (McCaskill et al., Reference McCaskill, Lucas, Bayley and Hill2011). In contrast, studies on regional variation in phonology are fewer in number (Bayley et al., Reference Bayley, Lucas and Rose2000; Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Bayley and Valli2001), reflecting the fact that in some cases no consistent patterns of regional sociophonetic variation have been identified (Hamilton & Hochgesang, Reference Hamilton and Hochgesang2017). An implication of these studies is that lexical variation in BSL may index regional and national identities in a similar way as accent in British English. In fact, BSL signers often refer to this lexical variation as “accent” (Rowley & Cormier, Reference Rowley and Cormier2021:928), which may be partly motivated by a recognition of its role indexing identity. We feel, however, that the primacy of lexical, compared to phonetic, variation in marking regional identities in signing communities is not as well known in the wider sociolinguistics literature as it ought to be.

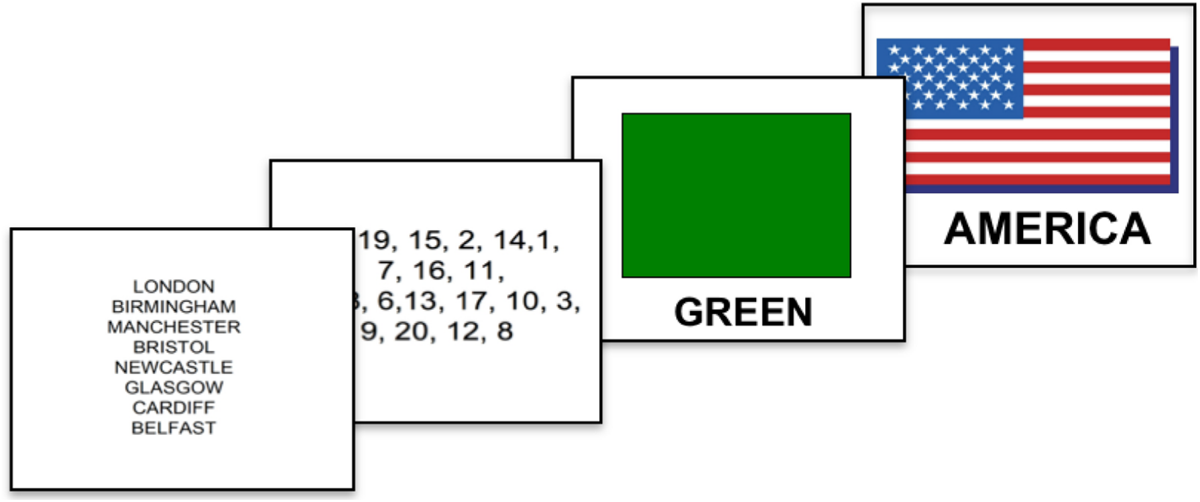

Against this background, our second study relates to work on lexical variation and change in BSL (Stamp et al., Reference Stamp, Schembri, Fenlon, Rentelis, Woll and Cormier2014). This quantitative investigation into BSL regional lexical variation drew on the BSL Corpus dataset (Schembri et al., Reference Schembri, Fenlon, Rentelis, Reynolds and Cormier2013). As part of the BSL Corpus, 249 deaf signers of BSL were filmed in eight sites across the United Kingdom: five cities in England (London, Bristol, Manchester, Newcastle, and Birmingham), as well as cities in Wales (Cardiff), Scotland (Glasgow), and Northern Ireland (Belfast). These sites were identified based both on documented lexical variation in BSL (Brien, Reference Brien1992) and discussions with deaf community consultants and fieldworkers as part of the BSL Corpus Project.

The data used in this study were collected by eliciting from all participants signs for 102 concepts, using slides with an illustration and a prompt in the form of an English word equivalent (see Fig. 4). Participants were asked to produce the sign that they preferred, or felt that they most often used, for this concept. Comparison with participants’ usage in conversation revealed that 78% of lexical variants used in the lexical elicitation task were also found in spontaneous dyadic conversational data, suggesting that the variants produced through elicitation were an accurate representation of their actual lexical preferences.

Figure 4. Examples of the elicitation stimuli used as part of the BSL corpus (from Stamp et al., Reference Stamp, Schembri, Fenlon, Rentelis, Woll and Cormier2014).

Variation was analyzed in a subset of 41 lexical items, including sign variants for colors (‘brown,’ ‘green,’ ‘grey,’ ‘purple,’ ‘yellow’), names of countries (‘America,’ ‘Britain,’ ‘China,’ ‘France,’ ‘Germany,’ ‘India,’ ‘Ireland,’ ‘Italy’), number signs from one to 20, and the United Kingdom place-names for the sites included in the study (‘Belfast,’ ‘Birmingham,’ ‘Bristol,’ ‘Cardiff,’ ‘Glasgow,’ ‘London,’ ‘Manchester,’ ‘Newcastle’). Responses were grouped into signs that were “traditional” for the signer’s region and “non-traditional.” Quantitative analysis found that age, school location, and language background were significant predictors of lexical variation: older signers, those who attended a local school, and those with deaf parents produced more traditional regional signs. Furthermore, results suggested that dialect leveling was taking place, with a decrease in the use of traditional, regional variants by younger signers and movement toward the use of supraregional variants (particularly from southern England), although this was clearer with particular sets of signs, like those for numbers, while others, like color signs, appeared to be changing more slowly. A comprehension task further corroborated the direction of change, showing that younger signers were more familiar with supraregional variants or those variants associated with the London area.

The United Kingdom place-name data were also analyzed, suggesting that place-name signs may work to index local, in-group, versus non-local, out-group, identities. Based on an analysis of 1,992 tokens, the study found the use of place-name variants differed significantly depending on whether the signer was a resident in that location, with the exception of signs for ‘Glasgow,’ ‘London,’ and ‘Manchester.’ Residents of Newcastle, Belfast, Bristol, Birmingham, and Cardiff were found to strongly favor the use of a local variant (or “endonym”) that differed from signs from outside the community. The endonym was often a reduced fingerspelled form, such as ‘M’ and ‘C’ for ‘Manchester,’ while the exonym (the name used by individuals from outside that city) was often a calque—that is, a literal translation of the equivalent English word. For example, one exonym variant for ‘Manchester’ consists of a compound of individual signs man and chest. This result confirmed ethnographic observations that residents of a city use a different sign variant for their city’s name than non-residents.

Overall, the findings from this study show that variation in BSL lexis is a systematic phenomenon: place-names, as well as regional color and number signs, clearly work to index local identities. Systematic change is also taking place in the BSL deaf community with a decline in lexical variation and a shift toward lexical variants with a wider currency (sometimes associated with southern England). This might reflect societal changes, including the closure of centralized schools for deaf children, the possible increased use of southern English variants in the media, and the increase in mobility and contact between signers from different regions. In the case of signs for the names of countries, this change reflects international language contact, with BSL signers increasingly shifting from traditional BSL signs to borrowing signs from other sign languages (e.g., the American Sign Language sign for ‘America’ has largely replaced traditional BSL signs). Furthermore, these findings support the claim that there is no consistent evidence for patterns of regional sociophonetic variation in sign languages (Hamilton & Hochgesang, Reference Hamilton and Hochgesang2017) and that lexical variation is perceived by signers as equivalent to sociophonetic variation in spoken languages in terms of marking regional identities (Rowley & Cormier, Reference Rowley and Cormier2021), implying that cross-modal differences may exist in this domain. Therefore, these findings are crucial for informing sociolinguistic theory in general, which should be derived from evidence in both spoken and signed languages.

Crucially, findings like these can only be obtained by examining variation at the lexical level in many sign languages. Because there have been no studies as yet demonstrating consistent patterns of regional variation at the phonological or morphosyntactic levels, by overlooking lexical studies, we inadvertently push aside a significant proportion of sociolinguistic research on sign languages. In doing so, the field runs the risk of missing out on crucial cross-modal generalizations. Studies, as aforementioned, point to the fact that there is only clear evidence of regional identities realized through lexis in sign languages; this lack of differentiation at other levels might represent a cross-modal difference, or it may relate to the comparatively short histories of many sign languages (i.e., there has not yet been time for regional sociophonetic patterns to emerge). Answering this question is an important extension of variationist sociolinguistics into the areas of cross-modal typology: is the lack of regional sociophonetic distinctions in BSL and other sign languages a modality difference or a language-age issue? This represents a new challenge for variationist theory, and one that we can only begin to address by comparing lexical variation across signing communities of different ages, work which has only just begun (Lutzenberger et al., Reference Lutzenberger, Mudd, Stamp and Schembri2023). Thus, studies of lexical variation may play a key role in understanding language emergence and evolution (Lutzenberger et al., Reference Lutzenberger, de Vos, Crasborn and Fikkert2021). This is a field of study which only the relatively recent emergence of many sign languages makes possible, since emerging sign languages may represent some of the “youngest” languages on the planet. For this reason, it is crucial to continue investigations cross-modally to understand to what extent differences are modality dependent or not.

Study 3: Diffusion of lexical innovation in American English online

Our third study focuses on tracking the diffusion of lexical innovation based on a large corpus of American social media. Despite being central to the variationist endeavor (Weinreich et al., Reference Würschinger1968), the diffusion of linguistic innovations at scale, especially above the levels of phonetics and phonology, has largely resisted analysis using more conventional approaches to sociolinguistic inquiry. In general, analyzing the spread of innovations in natural discourse requires access to large amounts of language data because innovations are necessarily rare, at least initially, generally occurring far less than once per million words, requiring datasets consisting of hundreds of millions of words to observe sufficient instances of these words for meaningful generalizations to be made. Collections of sociolinguistic interviews do not typically allow for sufficient data to be observed, especially over large numbers of time points or informants. Even traditional multi-million-word corpora of natural language are often far too small to reliably observe lexical innovations. Although surveys allow for rare forms to be elicited directly, they must be known beforehand, making diffusion difficult to study, especially in its early stages. The focus of variationist research on phonetic and phonological variation, which is generally more amenable to traditional approaches to data collection, as opposed to grammar and lexis, has also limited the study of diffusion, given the limited number of speech sounds and relatively slow nature of sound change. The spread of grammatical innovation also appears to often be relatively slow. As a consequence, we have not been able to describe in detail how the usage of large numbers of innovations has changed over time, precluding generalizing. Alternatively, lexical innovation can be a much more active phenomenon, as new words and signs are constantly being introduced, as catalogued by lexicographers and as analyzed by linguists interested in identifying common word formation processes (Bauer, Reference Bauer1983; Miller, Reference Miller2014).

Although it has traditionally been difficult to build datasets suitably large for studying lexical innovationFootnote 7 at scale, this situation has recently changed with the growing availability of very large and highly stratified corpora, especially from social media, leading to the development of computational sociolinguistics (Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Hovy, Kendall, Nguyen, Stanford and Summer2023; Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Doğruöz, Rosé and De Jong2016). Notably, while these new corpora have thus far only allowed for linguistic variation to be analyzed in a small number of very specific online varieties of language, they have greatly facilitated the analysis of the diffusion of lexical innovation within these varieties at scale, in real time, and across huge numbers of language users engaged in casual interaction, with a level of temporal and geographical resolution that has not previously been possible (e.g., Eisenstein et al., Reference Eisenstein, O’Connor, Smith and Xing2014; Stewart & Eisenstein, Reference Stewart and Eisenstein2018; Würschinger, Reference Würschinger2021). In this section, we therefore consider a series of studies that analyzed lexical innovation in American English based on the analysis of billions of words of geolocated social media data collected from across the contiguous United States from 2013 to 2016 (Grieve, Reference Grieve2018; Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Nini and Gou2017, Reference Grieve, Nini and Gou2018), which clearly illustrate how working with very large corpora of natural language allows for the study of lexical innovation to be pursued at a scale that has not previously been possible.

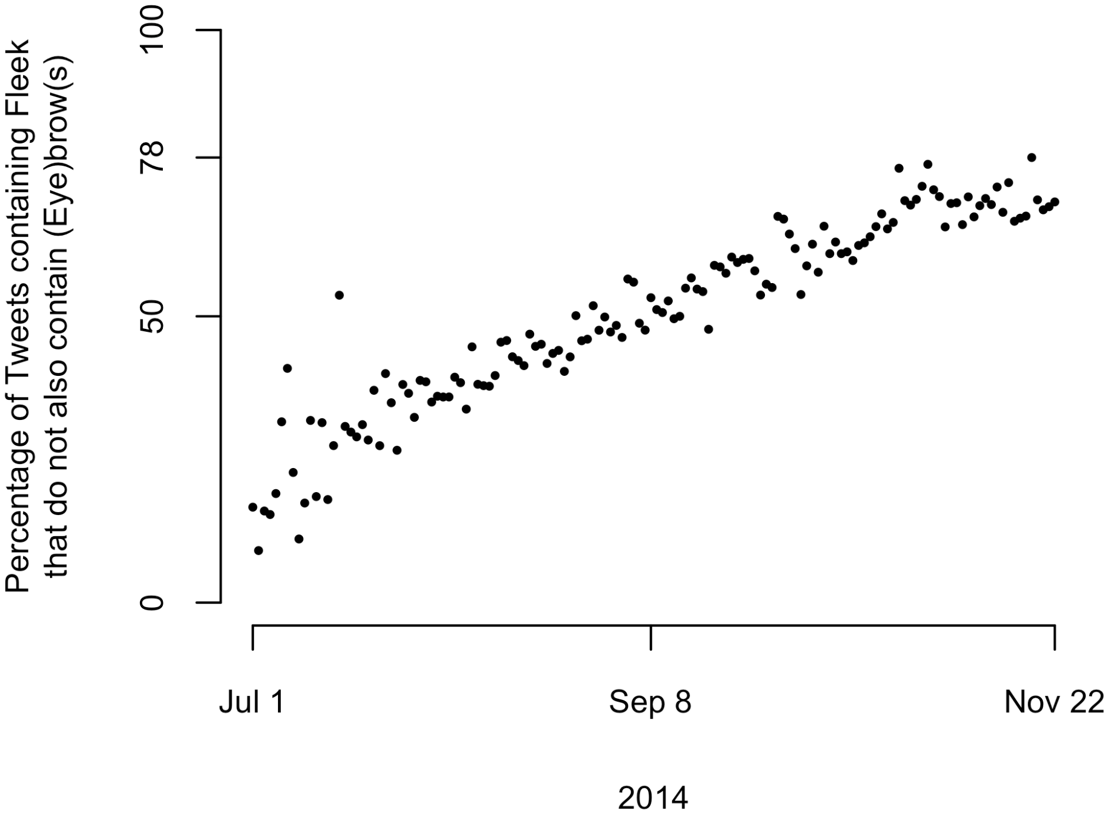

In the first study (Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Nini and Gou2017), a general method for identifying “emerging words” in a large time-stamped corpus was introduced. The application of this method was illustrated through an analysis of a multi-billion-word corpus of American tweets collected between 2013 and 2014, identifying word forms that were very rare at the start of this period but whose relative frequency increased rapidly over time on a day-by-day basis, excluding proper nouns and words found in standard dictionaries. Through this process, 29 unique emerging words were identified, many of which can be considered to be “slang,” and many of which are now, a decade later, fairly well established (e.g., baeless, boolin, famo, (on) fleek, faved, gainz, rekt).

By analyzing the properties of these words, generalizations about the systematic nature of lexical emergence in this variety were also uncovered. For example, although s-shaped curves are commonly found in historical sociolinguistics over much longer time-spans (e.g., Nevalainen & Raumolin-Brunberg, Reference Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg2016; Stratton, Reference Stratton2023), in this case, it was found that the relative frequencies of individual emerging words in this variety tend to show an s-shaped curve over real time, even though the corpus spans little more than a year. It was also found that shifts in meanings of some of these words could be observed over real time, illustrating how new words can quickly undergo semantic change during the early stages of diffusion, perhaps helping to propel their spread. For example, it was found that although the term on fleek was originally used only to refer to carefully manicured eyebrows, its meaning quickly generalized over just a few months, as it started to be used to refer to various other well-presented things (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Change in the meaning of (on) fleek (from Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Nini and Gou2017:120).

This study was also able to quantify the rate at which different word formation processes were used in this corpus, showing, for example, that compounding was most common, whereas true coinages were uncommon. Crucially, none of these insights are accessible through conventional approaches to data collection in sociolinguistics, illustrating the theoretical value of analyzing lexical innovations over very short periods of time, as made possible through large-scale corpus-based research. For example, as the case of on fleek demonstrates, understanding the semantics of a word can be directly relevant to understanding the mechanisms through which language changes.

In the second study (Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Nini and Gou2018), an even larger set of 54 emerging words was extracted from the same corpus and the diffusion of these lexical items was tracked over time and across the approximately 3,000 counties in the contiguous United States, taking advantage of the precise geolocation of all tweets in the corpus. In addition to the lexical items included in the first study, new words included balayage, litty, senpai, thottin, traphouse, and waifu. Crucially, because many emerging words were analyzed, it was once again possible to draw generalizations about the nature of the geographical diffusion of lexical innovation in this variety. It was found that new words tended to spread out from urban centers, identifying five main regional hubs of lexical innovation, as illustrated in Figure 6, centered within five distinct American cultural regions. New words were also found to spread within these cultural regions before spreading to the rest of the United States, illustrating the importance of cultural patterns for constraining the geographical diffusion of lexical innovation, as opposed to simply geographical distance and population density, as had traditionally been theorized to predict patterns of diffusion (Labov, Reference Labov, Britain and Cheshire2003; Trudgill, Reference Trudgill1974). Finally, the importance of African American Language as a source of lexical innovation in modern American English was affirmed, with three of the five hubs notably being centered on different parts of the South with especially large Black populations.

Figure 6. Hubs of lexical innovation in American English (US Twitter, 2013-2014) (from Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Nini and Gou2018:307).

Finally, in the third study (Grieve, Reference Grieve2018), these 54 emerging words were reanalyzed in a parallel multi-billion-word corpus of American Twitter data from 2016 to see how these words fared over time. For each word, the logged factor by which the relative frequency changed between 2014 and 2016 was calculated, and a linear model was used to predict this change based on four independent variables—word length, part-of-speech, word formation process, and whether or not the word expressed a new referential meaning (as opposed to being a synonym for an existing word). Overall, it was found that marking new meanings was the strongest predictor of lexical perseverance. Shorter words and words that were created using standard word formation processes were also found to be more likely to be retained over time. These results provide systematic evidence that new words that express new referential meaning are more likely to succeed, whereas words that are primarily used to express social meaning (i.e., that are synonyms for existing words) are less likely to succeed, perhaps because they tend to lose social meaning over time as they are adopted by a greater proportion of the population, demanding that more new words be introduced to fill this gap, creating a social meaning treadmill.

Overall, these studies clearly show the general theoretical value of analyzing lexis in very large corpora sampled densely over time and space to understand the diffusion of linguistic innovations. Crucially, many of the types of generalizations arrived at in these studies can only be obtained when conducting aggregated analysis of many linguistic innovations in real time, which is much easier for lexis compared to sound change and grammatical change due to the pace and diversity of lexical innovation. By taking a lexical perspective, it was therefore possible to track the emergence of linguistic innovations in far greater detail than in the past, challenging the well-established wave and gravity models, which have been based primarily on theoretical assumptions and limited empirical data. Most notably, these studies have shown that the spread of new words is not only constrained by geography and population density, as predicted by the wave and gravity models, but by their cultural associations and communicative functions.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have argued that lexical variation should occupy a more central place in the variationist paradigm, despite having long been relegated to the fringes of the field. Given the recent surge of lexical studies, both in adjacent fields and within variationist sociolinguistics, we believe the need to incorporate lexis methodologically and epistemologically into our field is clearer and more important than ever. To support this claim, we have presented three sociolinguistic studies of lexical variation that reaffirm the value of sociolexical research, as is increasingly evident from the growing body of literature (e.g., see Sandow & Braber, Reference Sandow and Braberin press). While our studies represent only three of the five modern research traditions that we have identified as pursuing research on lexical variation and change, our hope is that this paper will help to draw attention within the variationist community not only to variationist (specifically, third-wave) sociolinguistics, sign language sociolinguistics, and computational sociolinguistics, but to research being conducted in all five (additionally, cognitive sociolinguistics and historical linguistics) of these traditions and beyond. These case studies illustrate the broader body of research that highlights lexis as a key component in understanding the interface between language, culture, and society.

Notably, our three studies offer very different solutions to the two key methodological challenges that have limited lexical research in variationist sociolinguistics, as we outlined in the introduction to this paper. Furthermore, these studies have shown how, in various ways, the analysis of lexis can result in the identification of systematic patterns of lexical variation and change that can both extend and challenge theories of variationist sociolinguistics, which have generally been based on other levels of linguistic analysis. We believe these results, as well as the growing body of research on lexical variation and change in sociolinguistics and adjacent fields, therefore clearly show not only that the analysis of lexical variation is possible within the variationist paradigm, but that lexical variation is systematic and must therefore be accounted for by variationist theories if we are to have a complete understanding of the nature of language variation and change.

First, our studies illustrate different ways lexis can be systematically observed despite the inherent methodological challenges of studying linguistic forms that are generally incredibly infrequent, rarely occurring in natural discourse. This makes most forms of lexical variation difficult to observe via sociolinguistic interviews or other traditional approaches to data collection. Our first study shows how this issue can be overcome through carefully designed task-oriented approaches to eliciting lexical variation. By developing bespoke elicitation procedures such as spot-the-difference tasks, we were able to identify complex sociolinguistic patterns in lexical variation, with clear links to the expression of sociolinguistic identity. Similarly, our second study shows how lexical variation in BSL can be observed through the use of a picture naming activity. Although any elicitation task in sign language is hindered by the fact that signers are videotaped, minimizing the spontaneity of the task and increasing the severity of the Observer’s Paradox, task-oriented approaches have been developed that help to distract signers’ attention from the presence of cameras (Stamp, Reference Stamp2016). However, it is notable that sign language researchers have problematized assumptions around the Observer’s Paradox (see Schembri et al., Reference Schembri, Fenlon, Rentelis, Reynolds and Cormier2013). Finally, our third study illustrates a complementary approach to analyzing lexis, overcoming the inherent challenge of studying very low frequency forms by working with extremely large corpora of natural language harvested online. Taking this approach created a unique opportunity to observe lexical variation and change in detail in natural language use while directly avoiding the Observer’s Paradox.

Second, our three studies exemplify different ways that lexical variation can be meaningfully and rigorously measured. Because lexical items express referential meaning, measuring lexical variation within the standard sociolinguistic paradigm is challenging. While two word types are never perfectly synonymous across all tokens, either at the level of individuals or communities, actual tokens can be functionally interchangeable in context. As we exemplify in our first two case-studies, lexical variation can therefore be isolated through carefully constructed task-based elicitation methods, which allow us to track precisely where a variant could occur, thereby broadly satisfying the principle of accountability. Alternatively, in our third study, we eschewed the principle of accountability, as is common in corpus linguistics and many other fields, analyzing variation instead based on the relative frequencies of individual lexical types. This approach is necessary to obtain a complete picture of lexical variation and change, and by extension language variation and change more generally, because many words, including lexical innovations, are not meaningfully in alternation with any other existing forms.

Finally, our three studies clearly show that lexical variation not only is characterized by systematic social patterns, but that the analysis of lexical variation provides a unique perspective that extends and challenges existing theories of language variation and change. In our opinion, it is therefore not only possible to incorporate explanations for lexical variation into variationist theories but necessary if our goal is to develop robust and general theories that account for language variation and change across levels of linguistic analysis. In our first study, we see not only how lexical variation plays a critical role in the expression of sociolinguistic identity, but how the analysis of lexical variation provides a uniquely detailed perspective for understanding the complexity of the actuation of change and how closely it can be linked to the cultural context in which change occurs. In our second study, we see how lexical variation is an integral part of the variationist analysis of sign languages, where fundamental processes of language variation and change, such as the role of lexis in marking regional identity and the decrease in lexical variation from dialect leveling, appear to primarily occur at this level of linguistic analysis. To exclude lexical variation from sociolinguistic theory therefore amounts to the de facto exclusion of key aspects of sign language research from sociolinguistic theory. Lastly, in our third study, we see how the aggregated analysis of lexis in very large corpora of natural language can allow for the spread of lexical innovations to be tracked in far greater resolution—given both the speed and volume of lexical change—than is possible at other levels of linguistic analysis. Most notably, this study shows how this process is driven, in part, by the meanings that these words express, as well as the cultural contexts in which these meanings are expressed. Furthermore, although each word has its own meaning and history, this study shows that generalizations about lexical innovation can still be discovered by analyzing many innovations in the aggregate, demonstrating that, in fact, change in one word can tell us much about change in another.

Most importantly, in all three studies, we clearly see that lexical variation and change is not only amenable to rigorous variationist analysis, but that lexical variation is systematic, with many lexical forms varying together in a structured way, driven by external factors that shape how language is used in society, despite widespread assumptions in our field. In this regard, each study provides novel insight into the mechanisms and processes of sociolinguistic variation and change. In study 1, we see that the actuation of lexical change was driven by important cultural changes in Cornish society, with changes in tourism and attitudes to tourism influencing the sociolinguistic patterns of lexicalization of the concept tourist. Similarly, in study 2, we see how regional variation in education systems has resulted in systematic patterns of lexical variation in sign language. Finally, in study 3, we see that when regional variation in large numbers of lexical innovations is analyzed in the aggregate, it is possible to identify a small number of common patterns of lexical innovation in American English that are driven by well-established patterns of cultural variation in the United States. In all cases, these patterns of lexical variation are systematic, reflecting the importance of general extra-linguistic sources of language change. It is therefore clear that the analysis of lexis is critical to fully understanding language variation and change in all its complexity. Further integrating a lexical perspective in variationist sociolinguistics, through more widespread adoption of lexis-oriented methods, can complement existing knowledge at other levels of language structure and facilitate a more holistic perspective in the pursuit of understanding the processes and mechanisms of language variation and change.

Finally, the analysis of lexical variation makes it clear that variation in linguistic structure is generally linked not only to the expression of social meaning but to the expression of referential meaning. We see that this link between form and meaning, which has largely been excluded from variationist sociolinguistics for methodological and theoretical reasons, is actually an important driver of language variation and change. When we analyze lexical variation, this is a fact that we must acknowledge. Our claim is, therefore, not simply that lexical variation should be integrated into variationist sociolinguistics, but that the analysis of lexical variation must be integrated into variationist theory because it provides the basis for investigating aspects of the actuation and diffusion of language change that are not otherwise generally accessible when analyzing phonological or grammatical variation. Our three studies offer clear evidence of this claim: to obtain a complete picture of how people express social meaning in the real world, how sign languages emerge and change over time, and how linguistic innovations diffuse across a population, it is not only possible but necessary to study lexis. If variationist sociolinguistics does not at least attempt to account for variation at all levels of linguistic analysis, we cannot claim to be pursuing a complete sociolinguistic theory.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the reviewers of this article for their considered feedback, as well as the editors of Language Variation and Change. Any remaining errors are the responsibility of the named authors. We would also like to acknowledge the receipt of funding that made this work possible. Rhys Sandow was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council [AH/L503861/1]; Adam Schembri was supported by European Research Council Advanced Grant [ERC-ADG 885220 SignMorph]; and Jack Grieve was supported by the AHRC, ESRC, and Jisc (grant reference number 3154) as part of Round 3 of the Digging into Data Challenge.

Data availability statement

The data that support the three studies presented in this article can be made available upon request to the authors.

Appendix

Research Articles by Topics in Language Variation and Change (2012-2023)