Introduction

On 25 May 1886, the festivities celebrating the marriage of Prince Carlos to Princesse Amélie d’Orléans coincided with the inauguration of Lisbon’s grand new boulevard, Avenida da Liberdade, symbolizing the city’s modernization and northward expansion.Footnote 1 This event marked the end of the once iconic Passeio Público – Lisbon’s first public garden, designed entirely from scratch in 1764. Ordered by Sebastião de Carvalho e Melo (1699–1782), later known as the Marquis of Pombal, the garden was established in Lisbon’s northern district as part of the city’s urban renewal following the devastating 1755 earthquake.

The history of doing and undoing the Passeio Público is filled with contradictions, advances and setbacks. In this article, drawing on the long-term history of the Passeio Público from its inception until its decline, and considering the various political, social, economic, artistic, technical-scientific and environmental factors, I argue that political issues and the Liberals’ narratives were primarily responsible for the disappearance of the Passeio Público.

These dates, 1764 and 1886, which mark the beginning of the Passeio Público and the inauguration of the boulevard built over it, correspond to two very different political regimes. The year 1764 falls in the middle of King José I’s reign, when Carvalho e Melo held actual power in Portugal, a period associated with the ancién régime and absolute monarchy.

By 1886, Portugal was reigned by King Luís, who led a constitutional monarchy that had been evolving since the early decades of the nineteenth century, gaining strength with the Liberals’ victory in 1834 after a civil war between the Absolutists and the Liberals. The years following the Liberals’ victory were marked by instability, and it was the political regime established in 1851, known as Regeneração (hereafter Regeneration), that finally brought the political, economic and social stability that allowed for material progress and modernization.Footnote 2

By adopting the conceptual framework of the ‘infrastructural turn in historical scholarship’,Footnote 3 this article calls for an examination of Lisbon’s first public garden’s materiality, state power, technology and culture, as well as the interconnections between political and technical actors and the narratives and visions of different political regimes. Specifically, this article explores green infrastructure in relation to the middle layers and substrates where daily processes and practices occur, focusing on the interaction between infrastructure, spatial landscape transformation and political and social factors. This concept dates to the 1990s and focuses on building networks of structures related to landscape, ecology and water to address the environmental and societal aspects of urban contexts.Footnote 4 In this sense, Lisbon’s current network – connecting public gardens, boulevards, bike lanes, tree-lined streets and urban vegetable gardens – is part of this green infrastructure. Much of it was built by the Liberals in the nineteenth century, despite the concept of a green infrastructure not existing at the time.Footnote 5 However, its starting point was the Passeio Público, which set the direction for its main axis – the boulevard called Avenida da Liberdade. By examining the inception of Lisbon’s green infrastructure in the longue durée, this article aims to clarify the reasons behind the ups and downs and, finally, the decline of the Passeio Público (see Annex 1).

This article falls within the scope of the urban history of science, a dynamic discipline that combines the study of urban environments with the development of scientific and technical knowledge. It explores how urban planning and technoscientific expertise shape and influence one another in the modernization of cities.Footnote 6 While garden and landscape studies have traditionally focused on these spaces,Footnote 7 the study of Lisbon’s modernization has been largely dominated by art historians analysing the city’s eighteenth- and nineteenth-century urban and architectural developments.Footnote 8 Over the past two decades, historians of science have also examined Lisbon and its gardens.Footnote 9 Following this shift, recent research has shown that greening Lisbon was a fundamental component of the Liberals’ vision for a modern city from 1840 to 1900.Footnote 10

Art historians have long portrayed the Passeio Público as a relic of the Marquis of Pombal’s era, destined to be replaced by a modern boulevard – a symbolic rupture between the ancien régime and Liberalism.Footnote 11 However, I will demonstrate that the garden was actually built by the Liberals in the 1830s, having previously been nothing more than a grove with aligned trees. This article also challenges the supposed dichotomy between the Passeio Público and the boulevard by highlighting the rise of the Jardim da Estrela (hereafter Estrela Garden) as a direct competitor from its inception in 1852. Once the Liberals launched their own project – the Estrela Garden – they withdrew support from the Passeio Público, shaping the narrative that led to its decline.

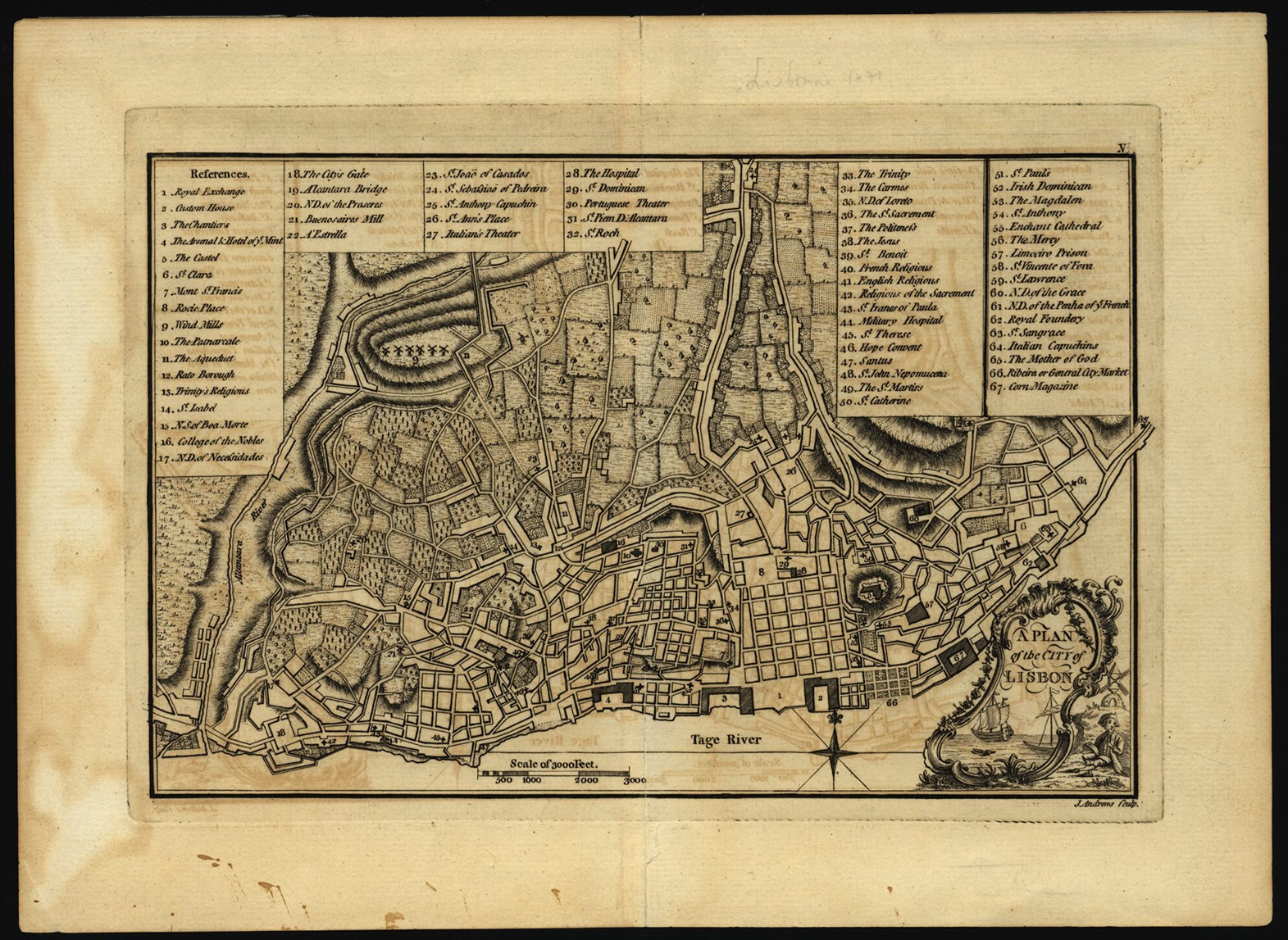

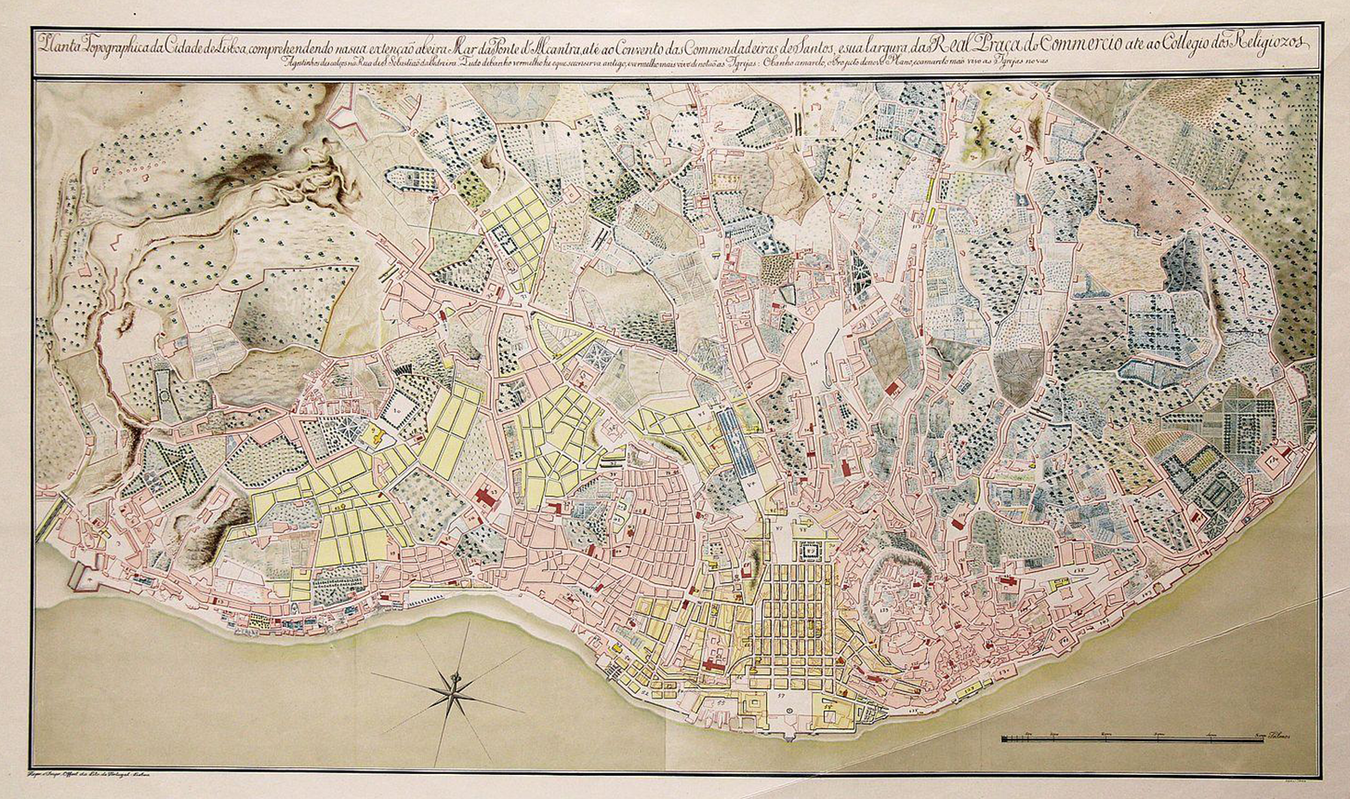

This work was carried out through the investigation of travel accounts, periodicals, City Council minutes and manuscript documents – some previously published and others unpublished – along with access to numerous maps of the city of Lisbon, most of them published here for the first time. It also involved the planimetric reconstruction of the various phases of the Passeio Público based on the different types of sources found at the Municipal Archives, National Library, City Museum and National Archives. The general facts about the Passeio Público were already known. What this article does differently is offer a new interpretation of the sources, demonstrating that historiography has chosen to follow those who criticized the Passeio Público while silencing the voices of those who fought for its construction and preservation.

To unfold my arguments, I have divided the article into four parts. The first part covers the absence of construction from the garden’s inception until the Liberals’ victory. The second part focuses on the making of the Passeio Público by the Liberals in the 1830s. The third part highlights its golden age, when feasts and events gathered the king and court in its settings. The fourth part addresses its competition with the Estrela Garden, and it ends with an epilogue on the reasons behind its dismantlement to make way for Lisbon’s grand boulevard – Avenida da Liberdade.

The early struggles of the Passeio Público: from ambition to setbacks (1764–1834)

During the reign of King José I, a natural catastrophe led to the largest urban construction plan in Europe in the eighteenth century. The 1755 earthquake destroyed nearly the entire downtown of Lisbon, and the Marquis of Pombal, along with engineers and architects, directed the reconstruction of Lisbon according to a completely new and different plan to that which existed before.Footnote 12

In this context, the Marquis sought to crown the project with the creation of a landscaped area for recreation, to promote social interaction and to improve the city’s ventilation. Thus, within the overall reconstruction of Lisbon after the 1755 earthquake, the Passeio Público became the first European public garden to be built from scratch, but it was not an idea ahead of its time. Other public gardens already existed in Europe by then, but these were typically royal gardens that had gradually been opened to the public, such as the seventeenth-century gardens of La Cour de la Reine in Paris and the Kensington Gardens in London.Footnote 13 Other promenading green areas existed, such as the alamedas, notably the Alameda de Hércules in Seville (1574).Footnote 14 Although Passeio Público might be literally translated as ‘public walk’, the word passeio in nineteenth-century Portuguese was used for ‘garden’; it was also used to refer to the Estrela Garden as the Passeio da Estrela. Thus, I consider that alamedas were much more a forerunner of the boulevard than they were related to this enclosed public garden.

In 1764, Carvalho e Melo commissioned the architect Reinaldo Manuel dos Santos (1731–91).Footnote 15 Having lived in London and Vienna as a diplomat, Carvalho e Melo was no stranger to grand gardens as vibrant spaces for leisure and social gatherings. It is likely that he recognized the need for similar spaces in Lisbon, where social interaction across classes, groups and genders was limited. Both foreign and local observers noted that, in the late eighteenth century, Portuguese women, especially those of the elite, rarely appeared in public and remained confined to the private sphere. In part, it was to challenge this status quo that the Marquis of Pombal envisioned a public garden, as remarked on by the Irish architect James Murphy (1760–1814), who visited Portugal between 1789 and 1790.Footnote 16

However, the Marquis’ efforts were not successful: numerous foreign and local visitors to Lisbon at the time noted that the garden was rarely frequented in its early years. One reason given for the lack of public attendance was the dress code, which prevented the lower classes from entering it. In 1774, the Englishman William Dalrymple already noticed that ‘by particular edict, no one is allowed to go in a cloak’,Footnote 17 and the French entrepreneur Jácome Ratton (1736–1822), who lived in Portugal, confirmed that ‘few people frequent it, perhaps because men in cloaks are prohibited’.Footnote 18 At the turn of the nineteenth century, the French physician Joseph-Barthélemy-François Carrère commented in his travel journal that ‘in this sole garden of Lisbon, one never encounters more than 30 people’.Footnote 19 Portuguese society had not yet adopted the everyday habits of bourgeois life, which included theatre outings, café conversations and strolls through gardens. Moreover, at this stage, the garden seemed detached from the city, which was still oriented towards the river. It appeared to be little more than an unfinished and poorly maintained grove, with no attractions, beauty or comfort, making it unappealing to the elites.

The chosen location was frequently criticized. Situated at the northernmost part of Lisbon at the time, just beyond Rossio Plaza – so much so that it was also known as ‘Passeio do Rocio’ – it was criticized for being ‘in a remote place with difficult access, buried at the foot of a high hill, which prevents the free circulation of air’.Footnote 20 Furthermore, it offered no views, a most desirable feature in gardens. However, several reasons are likely to have contributed to this choice of location. On the one hand, it was where the rubble from the earthquake had accumulated, which urgently needed to be concealed and beautified. On the other hand, there was no available space within the urban fabric of the time, and in this location, just a few expropriations of land and vegetable gardens had to be made to make space for this public infrastructure.Footnote 21 It had the merit of setting the direction for the city’s growth to the north and shaping its green infrastructure, as it was in that very spot that the city’s main axis – Avenida da Liberdade – would later be built. To this day, it thrives as one of the city’s most prestigious areas.

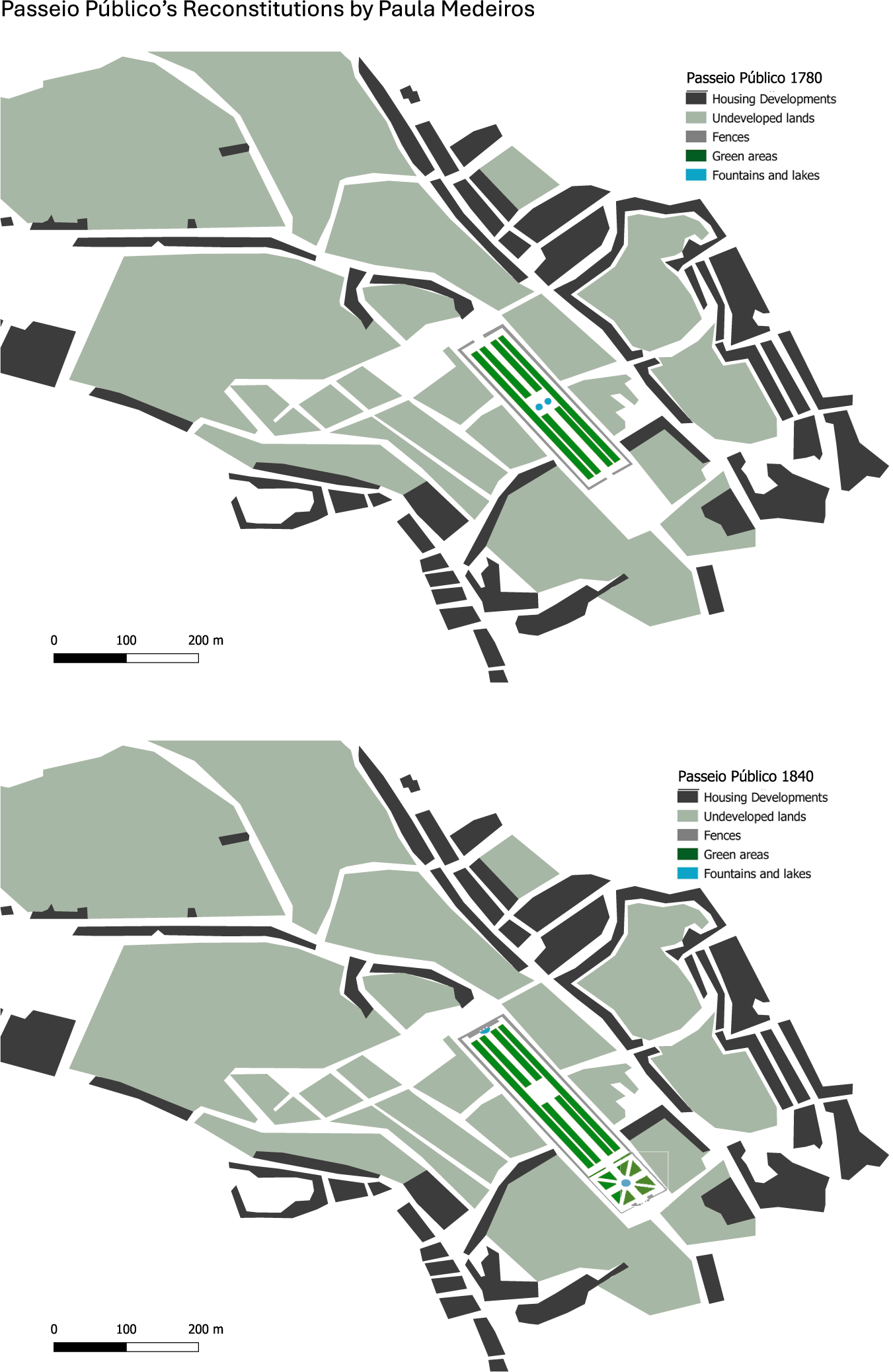

After being commissioned, there is no evidence that any feature of the garden was built until the mid-1770s. In 1768, the survey of all Lisbon’s parishes by Sergeant-Major José Monteiro de Carvalho did not indicate its presence on the map of St Joseph Parish, nor does it appear on the 1771 map by British historian John Andrews (Figure 1).Footnote 22

Figure 1. John Andrews, A plan of the city of Lisbon [London: n.p., 1771]. BNP, C.C. 397 P2.

Construction probably began shortly afterwards, as noted by the Englishman Richard Twiss, who visited Lisbon between 1772 and 1773 and observed that a new ‘walk’ was being built.Footnote 23 The first significant evidence of the Passeio Público’s existence appeared in 1774 when Dalrymple dismissed it as a ‘paltry kind of public walk lately made, by no means in style with the town’,Footnote 24 at a time when the city was becoming the most modern of eighteenth-century Europe, with new apartments being built. From the same period, between 1775 and 1776, there are reports describing a grove that measured 1,360 palms in length and 400 in width, with 1,123 trees sourced from nurseries managed by the prominent entrepreneur Jácome Ratton.Footnote 25 By the 1780s, some records criticized the poor quality of the completed work and noted the absence of key structures, such as a proper wall and gates. Additionally, debris from the 1755 earthquake still obstructed the intended entrance to the public garden.Footnote 26 At that stage, it resembled more of a promenade than a garden, to the extent that it was described by contemporaries as a ‘walk’ (Figure 2).Footnote 27

Figure 2. Map encompassing the area from the Alcântara Bridge waterfront to the Convent of the Comendadeiras of Santos, and from the Praça do Comércio to the College of the Discalced Augustinian Friars on São Sebastião da Pedreira Street, 1780. MC (Museu da Cidade [City Museum]) GRA.0495.

Investment in the Passeio Público was never a priority. During the reign of King José I, the reconstruction of Lisbon consumed all available capital, attention and effort from those involved. Under Queen Maria I, the situation worsened significantly – not only had the reconstruction efforts drained the kingdom’s treasury, but the dedicated funding for the reconstruction of Lisbon, which included the Passeio Público, was redirected to other projects favoured by the queen, such as the Basilica of Estrela. This led to the complete depletion of the Treasury and, in 1799, the subsequent order to halt all construction.Footnote 28

As a result, the Passeio Público remained incomplete and underwhelming. For foreign visitors accustomed to the grandeur of British and French gardens – where garden art was highly praised and developed – it fell far short of their standards. The Englishman Dalrymple dismissed it as a ‘miserable little promenade’,Footnote 29 while the Frenchman Carrère criticized it as ‘ridiculous and very small’, noting that 300 people would ‘almost entirely fill it’.Footnote 30

Although nearly 30 years had passed, almost nothing had been built. At the turn of the nineteenth century, new improvement plans by the Italian botanist Domingos Vandelli (1735–1816), director of the Botanical Garden of the University of Coimbra, emerged. Vandelli claimed that the garden area was insufficient for his intended ‘Economic Garden’, which should house a collection of ‘Medicinal Plants, Cereals, Legumes, Pasture Plants, and Dye Plants, akin to the Royal Botanical Garden’.Footnote 31 Following contemporary physiocratic theory, Vandelli advocated for utilitarian gardens cultivated with agricultural crops, as evidenced by his earlier publication on the benefits of botanical gardens for agriculture.Footnote 32 Vandelli still referred to the Lisbon public garden as ‘in progress’.Footnote 33 It was not yet properly enclosed, as his project included two budget options: one for a stone and lime wall and a cheaper one for a rammed earth wall. The garden was finally enclosed thanks to the efforts of Minister Rodrigo de Sousa Coutinho (1755–1812) and Senate President Luís de Vasconcelos e Sousa (1742–1809), during the regency of Prince João.Footnote 34

By 1802, it was properly enclosed and received more favourable opinions. The German naturalist and botanist Heinrich Friedrich Link (1767–1851) visited Portugal at the turn of the nineteenth century and deemed the Passeio Público a ‘moderate-sized garden’.Footnote 35 The Swedish Protestant pastor and traveller Carl Israel Ruders (1761–1837), who visited Lisbon between 1798 and 1802, described it as follows: ‘The garden is large, beautiful, and clean, but in the old French style. It has comfortable seating everywhere, and on the wall surrounding it, there are viewpoints with stone benches, some facing each other, and wide openings adorned with lovely iron railings, through which one can comfortably see the streets surrounding the garden.’Footnote 36 Ratton also recalls that ‘this garden is the only refuge the inhabitants of Lisbon have for strolling free from mud; however, it is often closed at times when it should be open’.Footnote 37

The following period was one of immense instability. In 1807, the Napoleonic invasions dictated the course of events for years to come. The royal family and the court embarked on a convoy of ships carrying 15,000 people, along with countless valuables, books and documents, bound for Rio de Janeiro, where they ended up staying far longer than initially expected. Lisbon effectively became a colony of its own colony; one of the many negative consequences of this was a complete lack of investment, with most construction projects in Lisbon coming to a halt. King João VI only returned to Lisbon in 1821 and signed the Liberal Constitution in 1822. However, his eldest son remained in Brazil, where he was proclaimed the country’s first emperor in that same year.

In 1823, the Lisbon City Council acknowledged receipt of a petition submitted by 70 citizens requesting ‘the completion of the Public Promenade project, in accordance with the design that had been deemed most suitable’. The council also noted the contribution offered by some councillors, consisting of the salaries to which they were entitled during that year. The government further promised to assist with the work ‘when compatible with the execution of other more necessary projects’.Footnote 38 That same year, the City Council demonstrated the will to complete the Passeio Público project by appointing a committee of six members (three councillors and three external members) to gather donations and raise additional funds. The committee would oversee funding, request materials, pay workers and document their actions in a public report to encourage transparency and further contributions. They believed this plan, if approved by the king, would ensure the completion of the project and inspire ongoing public support.Footnote 39

Unfortunately, King João VI died in 1826, and the resulting instability in the kingdom prevented the work from proceeding. Following his death, the rivalry between his eldest son Pedro (1798–1834) and his second son Miguel (1802–66) intensified. Pedro, a Liberal and already Emperor of Brazil, was crowned as King Pedro IV of Portugal. However, in Brazil, the fear of reverting to the status of a colony grew, and the king had to abdicate the throne of Portugal in favour of his daughter. She was married by proxy to her uncle Miguel, which quelled his ambition to restore an absolutist monarchy. The years that followed were marked by political turmoil, culminating in fratricidal and civil war between 1832 and 1834, pitting Absolutists against Liberals, with the latter emerging victorious.

On the eve of the Liberals coming to power, Lisbon was still littered with the ruins left by the earthquake, and the Passeio Público was nothing more than a garden in embryo. We can, therefore, hardly refer to it as a garden from the ancién régime.

The Liberals and the making of the Passeio Público (1834–40)

Following the Liberals’ victory in May 1834, numerous actions were taken to develop Lisbon’s green infrastructure. Owing to the dedication of both the Lisbon City Council and its citizens, the Passeio Público – once under the Crown’s authority – was officially transferred to the municipality on 12 April 1836, by royal decree.Footnote 40 This move was not just administrative; it was symbolic of a new era, marking the moment when the state stepped up to take on responsibilities that had once belonged to the monarchy.

With the Liberals reaching power, citizens again petitioned to transform the barren and unwelcoming grove of the capital into a beautiful public space.Footnote 41 By then, the Passeio Público was still a ‘grove about 300 meters long, completely walled in, with 15 barred windows on each side. The front was a wooden fence with a gate – a temporary structure that lasted from its foundation until 1834, when the municipal council commissioned a design to expand and complete it’.Footnote 42

In April 1835, the Lisbon City Council appointed a committee to oversee the work and supervise the completion and enhancement of the Passeio Público. The City Council had already taken the first step to providing a dignified entrance to the garden by ordering the removal of stalls cluttering the area, and ordering appropriate iron gates to replace the provisional wooden fence that had been installed at the entrance during the Pombaline period. Councillors then outlined the conditions for completing the iron railing for the front and sides of the garden, stipulating that it had to be made of wrought English iron, to replace the outdated masonry wall with 15 small windows that had been built during the regency of Prince João.

Beyond the political, economic and social difficulties that the country experienced following the Napoleonic invasions, even after achieving political stability, it faced enormous economic challenges, as can be seen from the efforts made to find a way to complete the garden. The Lisbon City Council contributed 2,332$000 réis (ancient Portuguese currency) to the project, which was as much as its budget could support – but it was not enough. Therefore, public subscriptions were launched to fund these garden improvements, given the municipal treasury’s deficit. The citizens that contributed, the amounts of their donations and, in some cases, the nature of their contributions were published in the Diário do Governo as a gesture of gratitude. Together they amassed 7, 204$510 réis. A proportionately smaller contribution of 25$200 réis was donated by municipal employees.Footnote 43 The amount was modest but reveals the collective effort to deliver what was considered a project that would contribute to the city’s beautification, when it was still grappling with ruins, construction and the task of clearing and removing debris left by the earthquake.

At this time, several proposals for the main gate, northern end, walls, parterre and pump house of the Passeio Público were signed by Anselmo José Braamcamp (1817–1885), who served as president of Lisbon City Hall between December 1834 and March 1836. These drawings were probably made by the city architect Malaquias Ferreira Leal (1787–1859), who aimed to construct the entrance ‘according to the original design’.Footnote 44 However, we do not know if these were precisely Manuel dos Santos’s early designs, as his project has not survived. Nevertheless, literary descriptions and iconography reveal a Baroque garden, which was not at all aligned with the main trends in garden art of the 1830s as there was no influence from English landscape garden design or its developments on the continent (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. ‘Passeio Público de Lisboa’, in O Panorama (Jornal Litterário e Instructivo da Sociedade Propagadora dos Conhecimentos Úteis), 188 (5 Dec. 1840), 385.

Figure 4. Tomás José da Anunciação, Passeio Publico = Promenade Publique, litografia de Manuel Luís da Costa, Lisbon, c. 1845. BNP, E.A. 94//12 A.

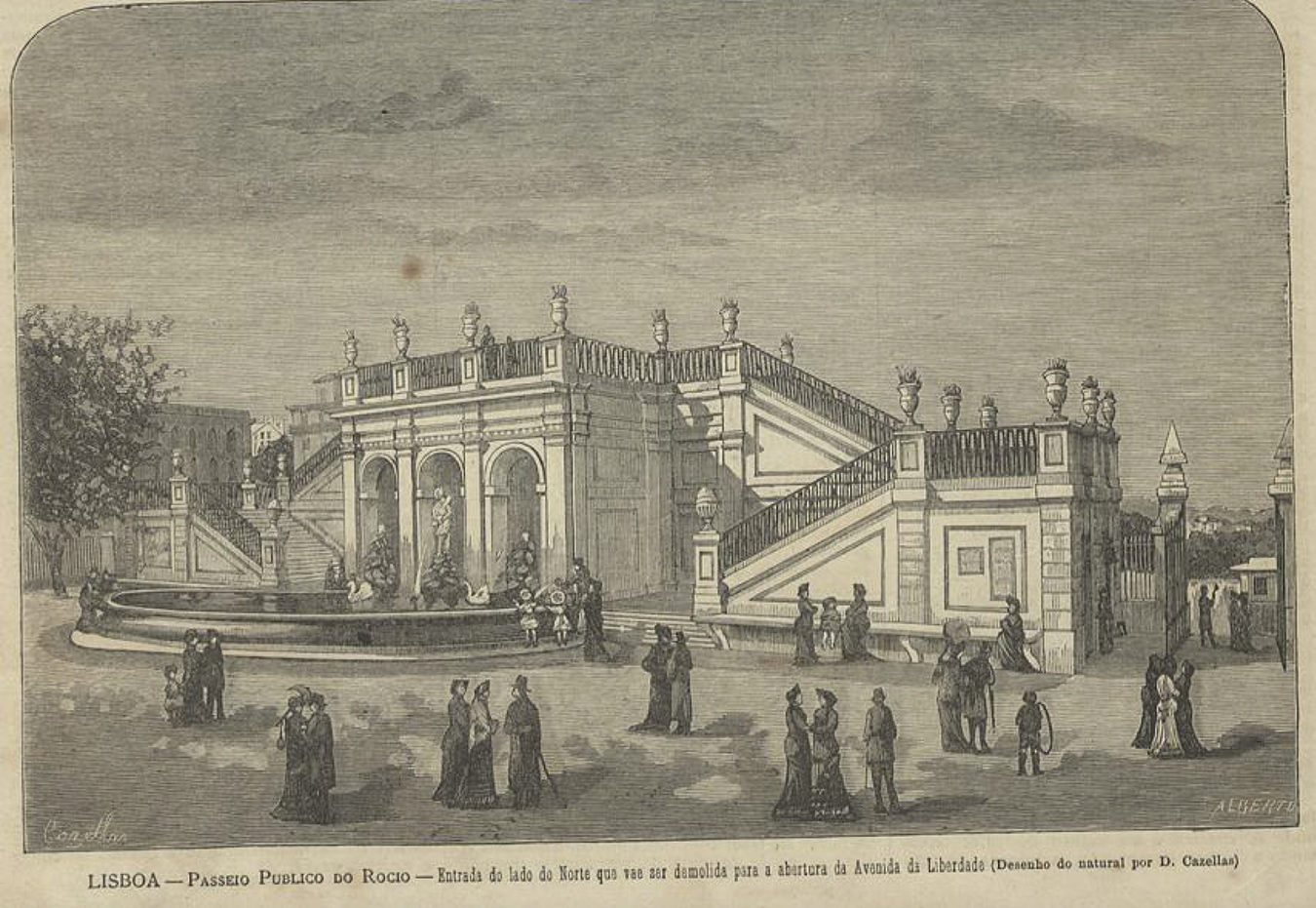

Despite these challenges, the municipal architect Ferreira Leal’s vision gradually transformed the grove into a true garden. The imposing masonry walls were replaced by a graceful iron fence mounted on a sturdy stone base, and the Passeio Público gained an additional 30 metres in length and 20 metres in width, particularly through the garden’s southern expansion.Footnote 45 Clearing debris opened the access square, creating a welcoming entrance. The garden’s main southern façade now featured three iron gates adorned with laurel wreaths and golden ribbons. The gatehouse and guardhouse blended into the railing, marking a new chapter for the Passeio Público as a proud symbol of Lisbon’s civic beauty and ambition (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Proposal for the main entrance of the Passeio Publico by the architect Malaquias Ferreira Leal, created for the 1830s renovation, though it was never implemented. ANTT, Ministério do Reino, Colecção de Plantas do ex-A.H.M.F., cx. 5274, no. 3.

Beyond the difficulty in raising funds, the reuse of various sculptures, whether complete or not, from other projects also reveals the financial constraints under which the City Council operated. The main lake reused six tritons and mermaids that were originally meant for the abandoned Campo de Santana fountain, as well as two statues representing the rivers Tagus and Douro from other lakes (now located on Avenida da Liberdade).Footnote 46

Some remained dissatisfied with the recent garden updates. On 7 July 1837, the royal architect Joaquim Narciso Possidónio da Silva (1806–96), seemingly in response to the city architect, created an alternative project without being commissioned by the City Council. He proposed enclosing the northern side of the public garden and replacing the central entrance with two side entrances to improve access. He also suggested adding two Turkish-style pavilions, suited to the climate and economical to build.Footnote 47 The City Council did not pursue his ideas. This rivalry between the king’s architect and the city’s architect clearly illustrates the disorientation and discomfort surrounding the separation of powers that the recent constitutional monarchy brought to the relationship between the queen and municipal powers.

On 4 April 1838, the garden was ceremoniously inaugurated in honour of Queen Maria II’s birthday, with laurel crowns adorning its entrance. The garden was deemed operational, with a strict set of rules governing hours, behaviour, dress code and attendance. Open from sunrise to the evening ‘Ave Marias’ (prayers), entry was restricted: drunkards, the insane, porters and children under ten unaccompanied by an adult were barred.Footnote 48 Although accompanied children were welcome, this right did not extend to the abandoned children forced to beg in the city’s streets.Footnote 49

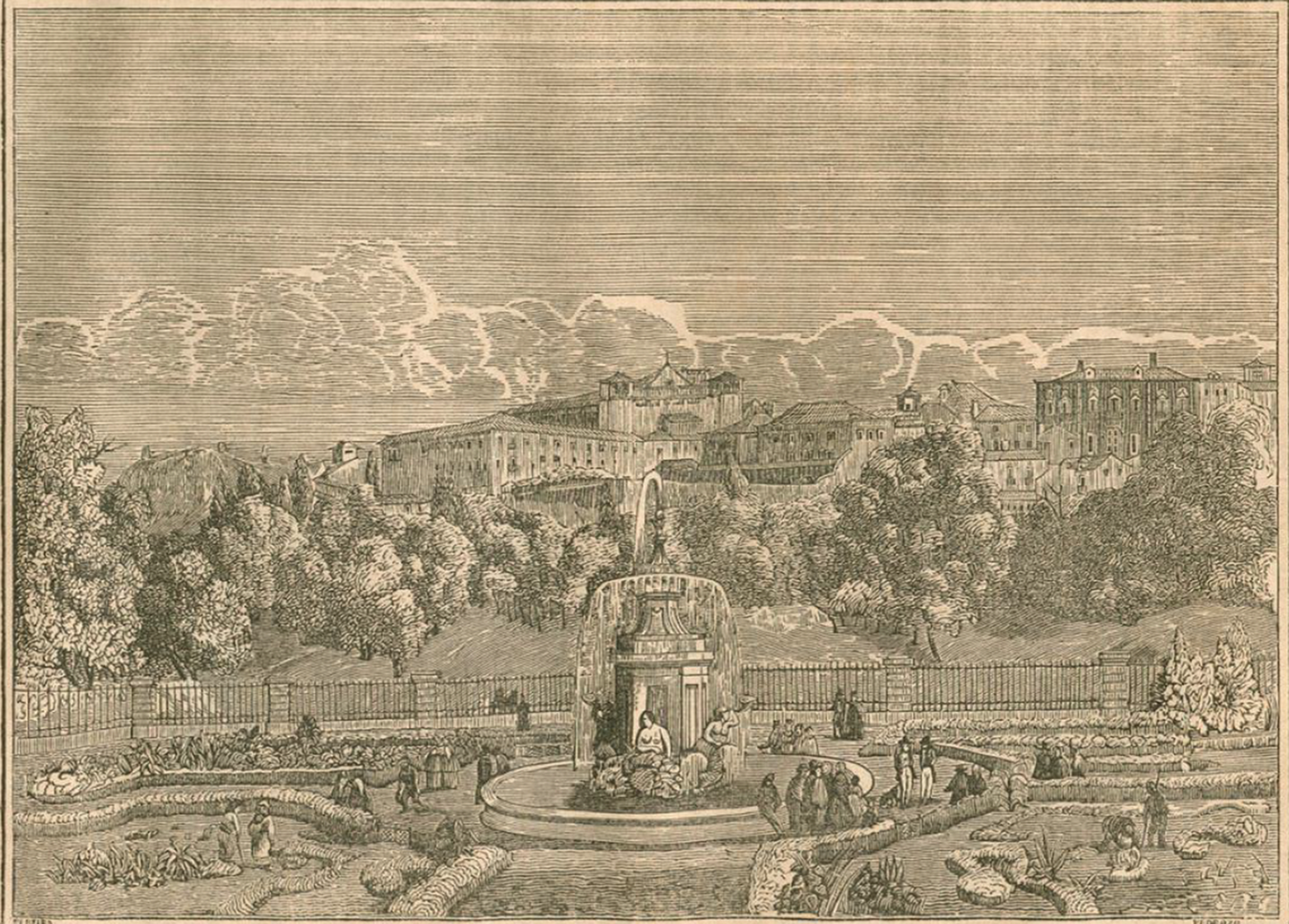

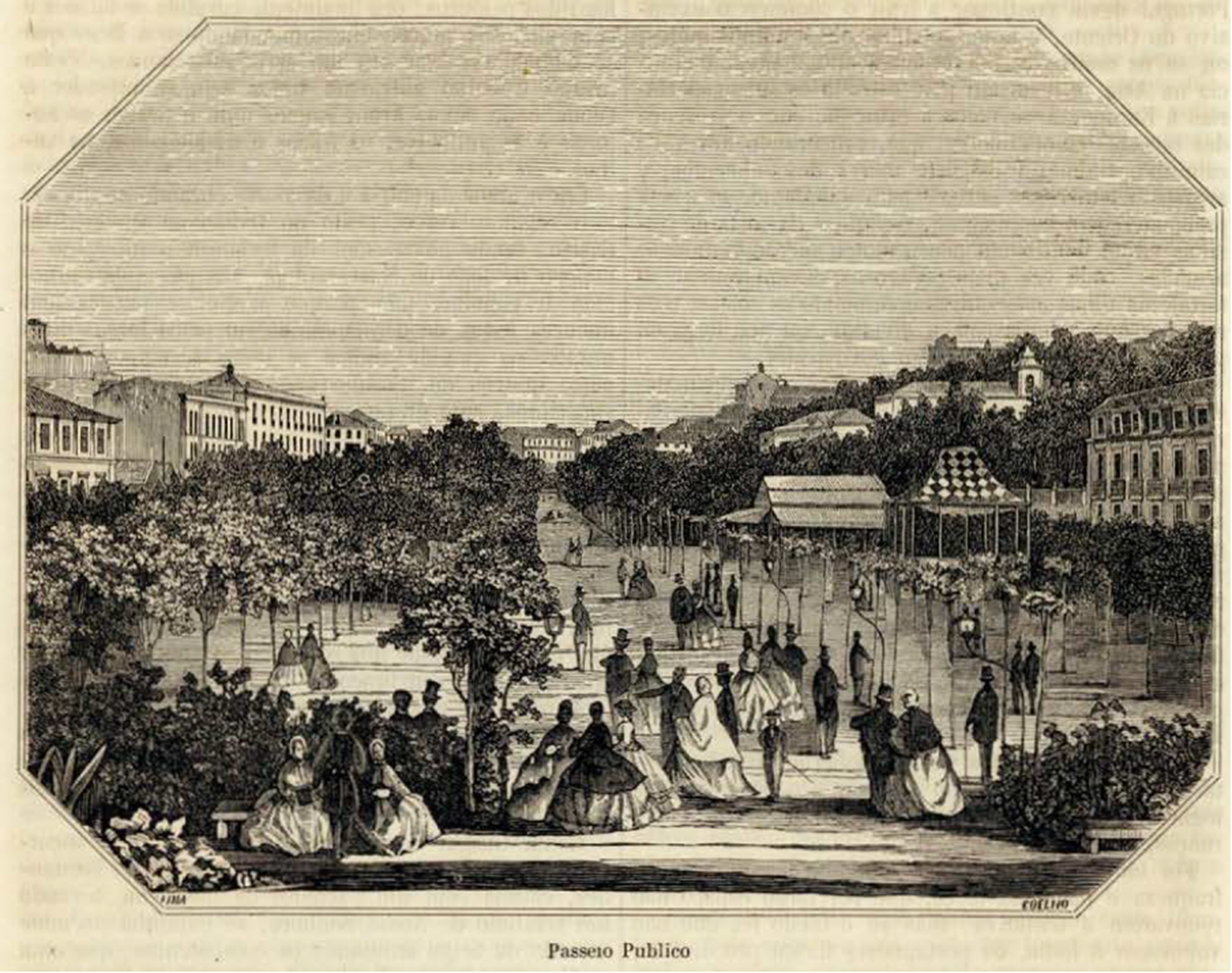

Though officially open, the garden remained incomplete, with various commissions struggling to secure sufficient funding to finish the work. By 1840, a grand cascade was finally installed at the northern entrance, featuring three arches and crowned by a statue of the sea goddess Amphitrite (Figure 6).Footnote 50 The new Passeio Público extended approximately ‘300 palmos’ beyond its previous boundary and was framed by a modest square, almost enclosed by private buildings. The main entrance, flanked by two gatehouses for the guard and gatekeeper, featured three iron gates, with the central gate being the widest. The garden was fenced with spear-shaped iron railings, interrupted by stone pillars topped with decorative capitals. Inside, the garden was divided into four quadrants, anchored by a large central lake with a distinctive pinecone-shaped fountain spout, replacing the previous fountain as its marine figure sculptures appeared disproportionate in size (Figure 4). Shaded groves filled with boxwood and laurel topiaries were threaded by a grid of paths – 13 running lengthwise and 32 across. Two additional lakes were planned to integrate with these lush sections.

Figure 6. Cascade at the Passeio Publico, Occidente, 159 (21 May 1883), 116.

While Universo Pittoresco highlighted the garden’s layout, it also underscored criticisms that had plagued the garden from the start. The article lamented the unfortunate location, and the garden’s enclosure by ivy-draped walls and iron-barred windows that evoked the confinement of a prison. Critics deemed the design monotonous, with its rigid symmetry, limited ornamentation and dense canopy that created a shadowed, sombre ambiance. Rather than a lively urban promenade, the garden was compared to a secluded retreat for monks, poorly suited to provide a pleasant diversion for the inhabitants of a populous capital.Footnote 51

Projected during the ancién régime to unite Lisbon’s inhabitants, the Passeio Público had finally evolved from a simple grove into the envisioned public garden by 1840, laying the foundation for Lisbon’s green network. Yet this goal of unity was only realized in a different political era, underscoring the infrastructure’s own agency. Foreign visitors in the late eighteenth century, especially from France and England, had criticized it as lacking the sophisticated garden design they were accustomed to at home. Despite the Liberals’ efforts to complete it – hindered by earlier plans, limited funding and disputes among the many parties involved – the garden still drew criticism for its location, design and sparse attendance. Gradually, however, the people of Lisbon began to embrace their garden, making it a part of the city’s life.

The Passeio Público reimagined: a legacy of constant reinvention (1848–58)

The Passeio Público’s history is one of relentless transformation. Less than a decade after the sweeping renovations of 1835–40, new plans were already underway, with fresh projects emerging by 1848. This cycle of doing and undoing reflects more than just changing aesthetics; it underscores the often-overlooked role of infrastructure as a force in shaping society.

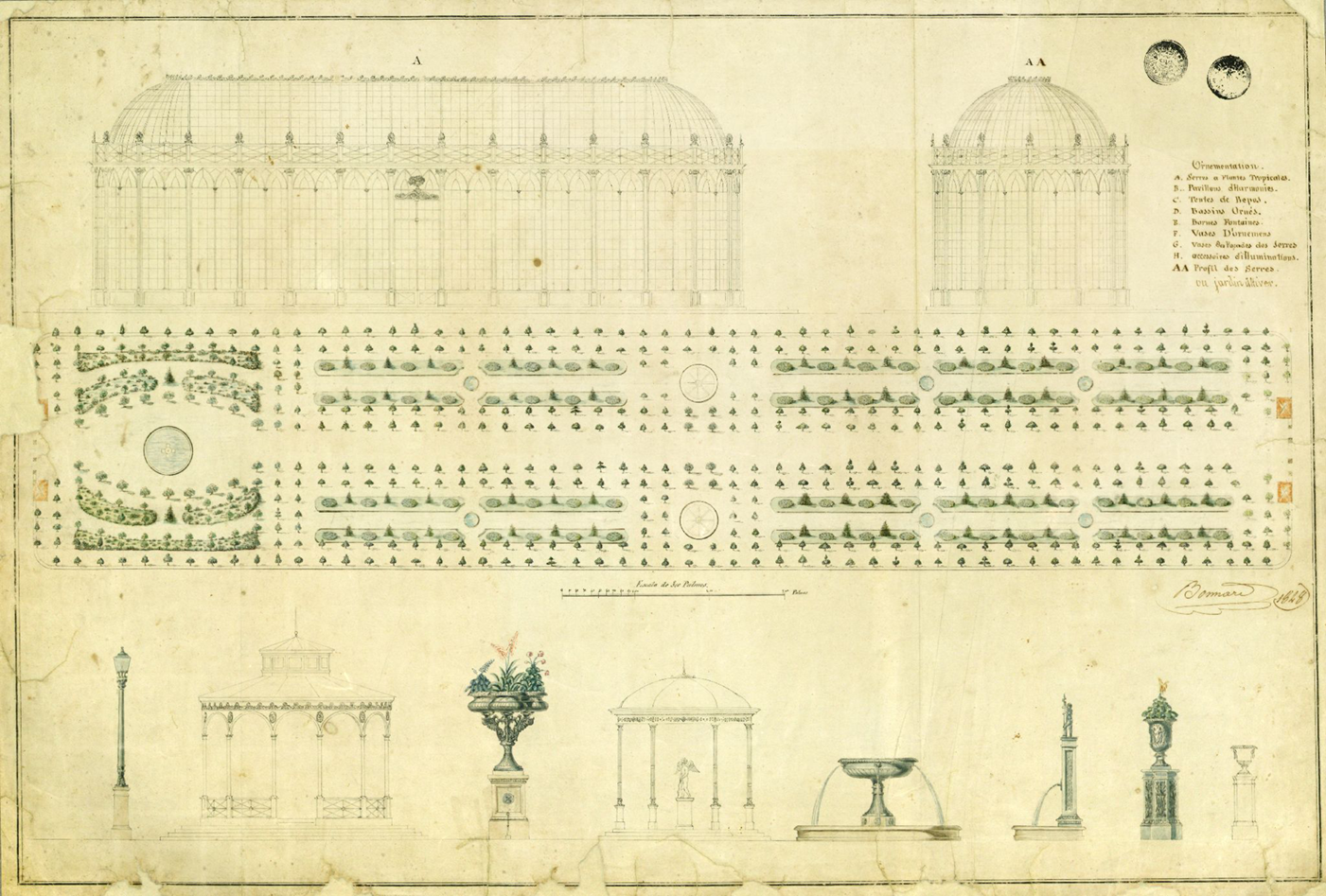

The Lisbon City Council sought expert recommendations for improving the garden’s layout and plantings.Footnote 52 Ideas were put forward by gardeners, councillors, engineers, architects and artistic agents. The Royal Master Gardener, the French Jean Bonnard (1797–1861), who was lent by King Fernando II to the municipality,Footnote 53 envisioned a lush garden with urban furnishings in the French picturesque garden style (Figure 7). The Royal Goldsmith and Artistic Agent to King Fernando II, Raimundo José Pinto (1807–59), also made proposals and prioritized entertainment areas.Footnote 54 Aires de Sá Nogueira (1803–82),Footnote 55 councillor of the Department of Gardens and Green Grounds between 1852 and 1857, envisioned a complete botanical renewal, including the acclimatization of exotic plants and adding water features. By October 1852, experts consulted by the City Council recommended refurbishing the gardens by removing boxwood borders, cutting down dying trees and replacing them with hardy, climate-adapted species like palm trees, magnolias, lemon and orange trees, lindens and tulip trees.Footnote 56

Figure 7. Jean Bonnard’s proposed design for the Passeio Público dates from 1848. AML, A.H., doc. 6880.

Sá Nogueira, charged with overseeing Lisbon’s gardens, envisioned a bold botanical renewal of the Passeio Público, but his ambitions clashed with budget limitations and stirred tensions within the City Council. Standing firmly against him was Councillor Alberto António de Morais Carvalho (1801–78), who challenged the premise of the project. Was replacing trees truly a radical transformation, or merely routine garden upkeep? The debate over preservation versus renewal threatened to stall progress, turning a simple landscaping decision into a battle over urban needs and civic demands.Footnote 57

The City Council accused Sá Nogueira of overreaching by unilaterally deciding the fate of the trees, wielding the ‘destructive axe’ without first assessing their health, even removing those that were thriving. Sá Nogueira was further criticized for prioritizing his department’s interests above other civic needs. Carvalho accused him of treating the Department of Gardens as an independent authority, focused on expansion even at the expense of other city services. Carvalho argued that, while improving gardens was valuable, addressing urgent needs – like paving streets and improving drainage to reduce disease – was a more pressing priority for Lisbon’s citizens.Footnote 58

Not everyone thought the same way. A contemporary, the writer, Lisbonologist and journalist Júlio de Castilho (1840–1919) considered ‘The Lisbon Passeio a civilizing influence; the development of national sociability owed much to it. It was a cultural hub. There, one could listen to excellent music, fall in love, daydream, and meet people; the Lisbon resident stopped being a recluse and felt like a Parisian in the Tuileries Garden.’Footnote 59

By the mid-nineteenth century, the Passeio Público had been beautifully transformed, with a redesigned lake and enchanting gas lamps lining the main avenue – a recent innovation in Lisbon that created a dazzling, almost magical atmosphere. The gas lights, described as ‘luminous diamonds’, quickly became a sensation, drawing thousands of visitors. Castilho fondly remembered the festive nights of August 1851, marvelling at the joy and crowds that filled the garden: ‘What joy on those nights! How many thousands of people gathered there!’Footnote 60 One of the most criticized aspects in the past had been the garden’s opening hours, as it used to close at sunset when it would have been more pleasant to stay open, and the strict dress code. By the 1850s, the garden was open at night and entry was granted to all those who were respectably dressed.Footnote 61

The garden became a favoured venue for charity events hosted by the asylum for the poor, which, thanks to the City Council’s permission to open the park at night, drew eager crowds for evening strolls, reminiscent of public gardens abroad. The Passeio Público reached its golden age in the summer of 1857 with dazzling nighttime illuminations: 16,086 lights glittered nightly across 5,000 balloons, 190 stars and vases, 3,000 lamps on the cascades and 596 garlands, while 7,300 colourful lamps adorned an obelisk and cascades, shining like rubies and emeralds (Figure 8).Footnote 62 That year’s display, brighter than ever thanks to new tallow lamps, cast an enchanting glow over the park – a magical tapestry of light that captivated Lisbon’s residents and lit up the city’s nights. Over ten nights, 27,948 spectators enjoyed this spectacle, filling 10,084 chairs and purchasing raffle tickets.Footnote 63

Figure 8. ‘Iluminação do Passeio Publico’, Archivo Pittoresco, 6 (1857), 41.

This was the golden age of the Passeio Público, when King Fernando frequented the garden, drawing the entire court, while Lisbon’s urban middle classes embraced a bourgeois lifestyle, heavily influenced by French city life. On warm summer nights, the garden came alive with illuminated spectacles, becoming the place to be – an enchanting sight that dazzled all who attended.Footnote 64 It was not just a garden; it was a social hub where the upper echelons of society could see and be seen, marking a shift towards the refined tastes and leisure activities of the era’s urban bourgeoisie.Footnote 65

By 1858, the garden hosted a new café-concert, offering open-air performances of concerts, comedies and dances, alongside a bandstand for musical performances (Figure 9). Throughout this period, bi-weekly flower shows and evening illuminations sustained the park’s allure, with extensive upgrades, including new trees, iron fences, benches and shaded arbours. Constructions and renovations were carried out, such as planting many trees; establishing new pipes between the two central lakes; making iron fences to surround them; placing two water posts, 16 iron benches with decorations, 12 wooden benches and a fenced area for flower exhibitions; and constructing an arbour to hide the gas meter.Footnote 66

Figure 9. ‘Passeio Publico, Archivo Pittoresco, 42 (1863), 329.

The City Council and private entrepreneurs were not giving up the Passeio Público and improvements continued. However, despite the city’s continued efforts and investments, the Passeio Público’s time of prominence was nearing its end, as newer social venues began to emerge and Lisbon’s heart gradually shifted elsewhere.

Between two gardens: popular affection for the Passeio Público versus Liberal favouritism for Estrela

In a magazine edited by the prominent historian and Liberal politician Alexandre Herculano (1810–77), the newly opened Estrela Garden was praised as ‘one of the fine works recently carried out in Lisbon’, emphasizing that ‘the alignment that overabounds in the Passeio Público does not appear even once in the Passeio da Estrela (…) The physical location of the new garden is decidedly superior to that of the old one.’Footnote 67 By contrast, the Passeio Público faced widespread criticism. Perhaps most contentious issue was the entrance fee, leading many to argue that it failed to serve as a true public garden, remaining out of reach for many citizens of Lisbon, to such an extent that the Liberals used this as a selling point for the Estrela Garden whose free entrance made of it a real public garden.Footnote 68 However, the dress code and admission of unsupervised children under the age of ten was also regulated at Estrela.Footnote 69

While most studies focus on the dismantling of the Passeio Público to make way for the Avenida da Liberdade, others argued that the Estrela Garden should also be part of the discussion. Since its inauguration in 1852, the Lisbon City Council demonstrated a clear preference for the Estrela Garden, often at the expense of the Passeio Público. From this point on, disinvestment in the Passeio Público was evident.

Although the area of the Estrela Garden, totalling 4.6 hectares, was about one-third of that of the Passeio Público, the Department of Gardens and Green Grounds of the Lisbon City Council allocated it twice the budget and nearly twice the number of staff. For example, in 1855 and 1856, the City Council spent 160,470 réis on salaries and other expenses for the Passeio Público, while allocating 377,310 réis to the Estrela Garden.Footnote 70 Later, in 1859, in addition to employee wages, 497,370 réis were spent on fences for the central lakes of the Passeio Público, 16 iron benches, 12 wooden benches, an iron fence for flower exhibitions and two trellises to be placed at the garden entrance, while 706,320 réis were spent solely on a greenhouse and 24 iron benches for the Estrela.Footnote 71 In 1864, 195,490 réis were spent on the Passeio Público and 327,600 réis on the Estrela. In 1869, expenses maintained the same proportion: 82,580,000 réis were spent on the Estrela Garden and 43,000,000 réis on the Passeio Público.Footnote 72 The same applied to the workers: of the 65 employees of the Department in 1869, 29 were assigned to the Estrela, while only 16 worked at the Passeio Público.Footnote 73

Criticism of the Passeio Público peaked in the 1870s, fuelled largely by Liberals who linked the garden to the ancien régime of Pombal. In contrast, they promoted the Estrela Garden as a symbol of their ideals. Yet, this was ironic: it was the Liberals of the 1830s who had improved the Passeio Público, redesigning and enhancing it as a garden long after Pombal’s era. Thus, the 1870s Liberals were essentially rebuking the work of their predecessors. Meanwhile, their ambitions for the Estrela Garden and the construction of a grand boulevard through Lisbon laid the groundwork for the garden’s eventual demise.

Epilogue: the undoing of the Passeio Público – a clash between people and politicians

The Liberals dismissed the Passeio Público as a bleak, walled-off space resembling a convent or even a prison. Francisco Simões Margiochi (1848–1904), councillor of the Department of Gardens and Green Grounds between 1872 and 1875, strongly criticized the Passeio’s outdated design, lamenting that it lacked the elegance of British or French garden traditions, referencing English landscape pioneers and even the French formalist gardener André Le Nôtre.Footnote 74 He viewed the absence of a modern avenue as a missed opportunity for Lisbon and championed the need for a boulevard that would unify the city with its outskirts and provide an image of progress. Since the mid-nineteenth century, Paris, where public green spaces were predominant, had become a role model for many European cities due to the urban renewal carried out by Napoleon III, Georges-Eugène Haussmann and Jean-Charles Alphand. The novelty of Parisian landscape renovation impressed the Lisbon City Council, which acquired all the volumes of Les Promenades de Paris by Alphand (1867–73). French influence became even stronger during the time when Margiochi was a councilman, as he established a specialized library on gardens and landscapes, most of whose books were authored by French writers.Footnote 75

Margiochi even claimed the title ‘father of the boulevard’, arguing that his 1874 proposal to demolish the Passeio gates was pivotal in realizing Avenida da Liberdade (Figure 10).Footnote 76 However, the idea to make a great avenue was not totally new. In 1859, the Lisbon City Council initiated discussions on building an avenue to link the lower city with the northern circumferential road, aimed at easing the movement of people and goods.Footnote 77 Other proposals followed, but the starting point was consistently the Passeio Público, with no initial plans to disturb the capital’s first public garden. By 1874, Margiochi proposed not only building the avenue but also demolishing the garden’s walls and gates. Still, it was not envisioned that the old Passeio would be destroyed. The idea of demolishing the Passeio Público and building the boulevard evolved over time. But the process was made easier by engineer Frederico Ressano Garcia’s (1847–1911) presence in Lisbon Hall from 1874. Trained in Paris at the École des Ponts et Chaussées, he witnessed the city’s grand transformation first-hand, including the 1867 Universal Exhibition. Paris, now the world’s most modern city, became his inspiration. He returned to Lisbon with both the vision and the technical expertise to reshape the city’s landscape.

Figure 10. Map of the city of Lisbon with the various improvements introduced and planned (Lisboa: Lith[ografia] Matta, 1888). BNP, CCD-65-A.

Although the decision to build an avenue from the existing garden or to demolish the Passeio Público to create a full boulevard remained undefined, work began on 24 August 1879.Footnote 78 Some buildings, including the Theatre of Dramatic Varieties, were expropriated and demolished. As the cascade at the northern end stood as one of the last remnants of the Passeio Público, it too was set to be demolished for the extension of the Avenida da Liberdade, now considered ‘one of the most important works undertaken by Lisbon’s City Council’.Footnote 79 By around 1882, it had become evident that the Passeio Público would fully disappear to make way for a boulevard. The trees of this cherished space – 822 trees of 41 different species – would (at least partially) be transplanted to other gardens and the newly planned boulevard.Footnote 80 By the third quarter of 1882, the garden railings had been removed, and in 1883, demolition of the south lake began to clear space for the Restorers’ Monument.Footnote 81 In 1883, the Passeio Público was permanently demolished, marking the end of an era, to make way for the hallmark of progress – the boulevard.

Yet, public sentiment tells us a different story. In the 1870s, some accounts described the Passeio Público as bustling with visitors. Some claimed it was loved across social classes, while others said it attracted mostly middle-class merchants, municipal soldiers, maids, Brazilians and ‘unaccompanied ladies from the Baixa’. These groups formed, until its dismantling, ‘the permanent public’s constant background’.Footnote 82 A Spanish traveller noted that the most interesting aspect of the Passeio Público was that ‘all classes mingled without mingling’. From bankers to artisans, landowners to merchants, everyone displayed ‘admirable composure’. Visitors strolled, gathered for concerts, watched fireworks and admired rising balloons with a dignified reserve that impressed foreign onlookers, who saw it as a mark of aristocratic grace. A Spanish traveller was astonished, stating that ‘The Lisboans, who were so fond of balls, theatres, and bullfights’, are now ‘falling for gardens’, attributing this change in customs and tastes to the English.Footnote 83

Although neglected by a historiography that has focused on Liberal critiques, the Passeio Público was praised by many citizens. Lisbon native Júlio César Machado captured this sentiment, observing, ‘The Passeio Público represents Lisbon out in the streets – Lisbon that goes out; Lisbon that shows itself; Lisbon that flirts and tires itself out – all of it can be found in the Passeio Público.’Footnote 84 While politicians pushed for modernization, the people clung to the Passeio as a cherished space, viewing its dismantling as a loss of their public right.

This attachment came into sharp focus in 1879. By then, a petition with nearly 2,000 signatures opposing the demolition of the Passeio Público was submitted to the City Council. The citizens of Lisbon had financially supported the city’s first public garden in the 1820s and 1830s, and now, once again, they stood against its destruction. The public petition was unsuccessful because the actual decision-making power was in the hands of the president of the Municipal Hall and the head of the Technical Department since the approval of the City Council Regulations in 1874.Footnote 85 At the time of the construction of Avenida da Liberdade, these positions were held by José Gregório da Rosa Araújo (1840–93) and Ressano Garcia, both staunch advocates of the need to build the boulevard to establish communication between the downtown area and the northern exit of the city, as well as a symbol of progress and modernity.

The public’s attachment to the Passeio Público was clear: as long as there were trees for shade and benches or even stones to sit on, the people of Lisbon continued to gather there daily, even amid its ongoing dismantling, to read the newspaper or chat in familiar surroundings. In 1883, when the garden faced the last demolition of its garden furniture, outraged Lisboans, feeling their civic right to public space was under siege, staged a spirited protest, shouting, ‘Vandals with no regard for our rights, for our well-being: tearing down this charm!’.Footnote 86 The Passeio Público had become, for them, a beloved emblem of civic identity – an irreplaceable part of Lisbon’s social fabric. Its history and former historiographical reviews demonstrate that it was a vital piece of the city’s first experiment in green urban infrastructure, embodying both a physical and symbolic space that evolved across political eras.

Though often criticized by Liberals for its baroque, monastic design, and often cast as a relic of the ancién régime, its construction in the 1830s was actually guided by Liberal municipal councillors, architects and gardeners. This public garden – built with repurposed materials amid economic constraints – offered Lisbon its only green refuge, appreciated by locals and visitors alike.

However, from the 1870s Liberals became highly critical of the Passeio Público, championing instead the Estrela Garden, contrasting the two as symbols of different political regimes – the ancién régime and Liberalism. But as shown here, this narrative is a pure fabrication, as they were, in fact, criticizing a garden built by Liberals in the 1830s. Similarly, historiography has positioned the contrast between the Passeio Público and Avenida da Liberdade as emblematic of an outdated past that had to give way to a modern boulevard, reinforcing the narrative of obsolescence to justify the Passeio Público’s destruction.

From decision-making and funding to construction, the creation of the city’s first axis of green infrastructure highlights the complex interplay of political ideals, economic constraints, cultural shifts, social factors and individual actors – rather than biophysical conditions, climate or techno-scientific aspects – as the key determinants of its outcome.

Acknowledgments

I thank the editor and referees of this journal for their suggestions. I also thank the National Library of Portugal, the Archives of Lisbon Municipality and the City Museum for the figures included in this article. I want to express a special thanks to Paula Antunes Medeiros for the reconstitutions of the Passeio Público.

Funding statement

I thank the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology under the research project UIDB/HIS/UI0286/2020 and UID/00286/2025.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Annex 1