1. Coastal crisis

In the Anthropocene (Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Rockström, Richardson, Lenton, Folke, Liverman, Summerhayes, Barnosky, Cornell, Crucifix, Donges, Fetzer, Lade, Scheffer, Winkelmann and Schellnhuber2018), we face three urgent global challenges – a triple planetary emergency (Guterres, Reference Guterres2020). These are climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss. These human-induced emergencies are relentlessly driving the planetary system towards tipping points and changes, making our continued existence less safe (Rockström et al., Reference Rockström, Gupta, Qin, Lade, Abrams, Andersen, Mckay, Bai, Bala, Bunn, Ciobanu, Declerck, Ebi, Gifford, Gordon, Hasan, Kanie, Lenton, Loriani and Zhang2023; Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Rockström, Richardson, Lenton, Folke, Liverman, Summerhayes, Barnosky, Cornell, Crucifix, Donges, Fetzer, Lade, Scheffer, Winkelmann and Schellnhuber2018), including through potentially irreversible shifts in the Earth system’s components and processes (Lenton et al., Reference Lenton, Rockstrom, Gaffney, Rahmstorf, Richardson, Steffen and Schellnhuber2019; Rockstrom et al., Reference Rockstrom, Kotze, Milutinovic, Biermann, Brovkin, Donges, Ebbesson, French, Gupta, Kim, Lenton, Lenzi, Nakicenovic, Neumann, Schuppert, Winkelmann, Bosselmann, Folke, Lucht and Steffen2024). In the coastal zone, the triple planetary crisis manifests as accelerating losses and changes (Halpern et al., Reference Halpern, Frazier, Afflerbach, Lowndes, Micheli, O'Hara, Scarborough and Selkoe2019) with negative consequences for human communities and societies. The escalating pace of global warming (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Péan, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekçi, Yu and Zhou2021; Johnson & Lyman, Reference Johnson and Lyman2020), the rise in sea levels (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Karpytchev and Hu2023; Nicholls et al., Reference Nicholls, Lincke, Hinkel, Brown, Vafeidis, Meyssignac, Hanson, Merkens and Fang2021), the loss of biodiversity (Jaureguiberry et al., Reference Jaureguiberry, Titeux, Wiemers, Bowler, Coscieme, Golden, Guerra, Jacob, Takahashi, Settele, Diaz, Molnar and Purvis2022; Penn & Deutsch, Reference Penn and Deutsch2022), especially the loss of coral reefs (Eddy et al., Reference Eddy, Lam, Reygondeau, Cisneros-Montemayor, Greer, Palomares, Bruno, Ota and Cheung2021), sandy beaches (Brooks, Reference Brooks2020; Luijendijk et al., Reference Luijendijk, Hagenaars, Ranasinghe, Baart, Donchyts and Aarninkhof2018), deltas (Anthony et al., Reference Anthony, Syvitski, Zăinescu, Nicholls, Cohen, Marriner, Saito, Day, Minderhoud, Amorosi, Chen, Morhange, Tamura, Vespremeanu-Stroe, Besset, Sabatier, Kaniewski and Maselli2024), seagrass (Dunic et al., Reference Dunic, Brown, Connolly, Turschwell and Côté2021), and mangrove cover (Bryan-Brown et al., Reference Bryan-Brown, Connolly, Richards, Adame, Friess and Brown2020; Otero et al., Reference Otero, Quisthoudt, Koedam and Dahdouh-Guebas2016), as well as ocean pollution (Jouffray et al., Reference Jouffray, Blasiak, Norström, Österblom and Nyström2020; Landrigan et al., Reference Landrigan, Stegeman, Fleming, Allemand, Anderson, Backer, Brucker-Davis, Chevalier, Corra, Czerucka, Bottein, Demeneix, Depledge, Deheyn, Dorman, Fenichel, Fisher, Gaill, Galgani and Rampal2020; Riechers et al., Reference Riechers, Brunner, Dajka, Duse, Lubker, Manlosa, Sala, Schaal and Weidlich2021), are some of the scientifically confirmed trajectories that confront us. These manifest as potentially critical impacts on coastal communities and their livelihoods that demand societal responses at all levels (Cinner et al., Reference Cinner, Caldwell, Thiault, Ben, Blanchard, Coll, Diedrich, Eddy, Everett, Folberth, Gascuel, Guiet, Gurney, Heneghan, Jägermeyr, Jiddawi, Lahari, Kuange, Liu and Pollnac2022; Gill et al., Reference Gill, Blythe, Bennett, Evans, Brown, Turner, Baggio, Baker, Ban, Brun, Claudet, Darling, Di Franco, Estradivari, Gray, Gurney, Horan, Jupiter, Lau and Muthiga2023)

There is a groundswell of scientific evidence that urges immediate action (IPBES, Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo, Guèze, Agard, Arneth, Balvanera, Brauman, Butchart, Chan, Garibaldi, Ichii, Liu, Subramanian, Midgley, Miloslavich, Molnár, Obura and Pfaff2019; IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Péan, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekçi, Yu and Zhou2021, Reference Pörtner, Roberts, Poloczanska, Mintenbeck, Tignor, Alegría, Craig, Langsdorf, Löschke, Möller and Okem2022). The actions necessary to maintain an Earth system supportive of human well-being are equally clear, e.g. to avert public health impacts from extreme events worsened by climate change (H. Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Cirulis, Borchers-Arriagada, Bradstock, Price and Penman2023; Salvador et al., Reference Salvador, Nieto, Vicente-Serrano, Garcia-Herrera, Gimeno and Vicedo-Cabrera2023). Global policy urges mitigation of greenhouse gases, adaptation to climate change, and social transformation that improve fairness, equality, and access to resources. Indeed, measured by the abundance and scope of global policies, agreements, commitments, and institutions, humanity is aware of adverse global change in the Anthropocene (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., Reference Hoegh-Guldberg, Jacob, Taylor, Bolanos, Bindi, Brown, Camilloni, Diedhiou, Djalante, Ebi, Engelbrecht, Guiot, Hijioka, Mehrotra, Hope, Payne, Portner, Seneviratne, Thomas and Zhou2019; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Raubenheimer, Urho, Unger, Azoulay, Farrelly, Sousa, van Asselt, Carlini, Sekomo, Schulte, Busch, Wienrich and Weiand2021; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Kohler, Lenton, Svenning and Scheffer2020). People are increasingly anxious about observable, extreme and large-scale changes (Kurth & Pihkala, Reference Kurth and Pihkala2022; Mortreux et al., Reference Mortreux, Barnett, Jarillo and Greenaway2023; Smith, Reference Smith2020; Van Valkengoed & Steg, Reference Van Valkengoed and Steg2023), and these anxieties surface in social and political discourse (Spence & Ogunbode, Reference Spence and Ogunbode2023). At the same time, powerful vested interests, political strategy and lobbying, fear, ignorance, religious fervour, feelings of despair, and being overwhelmed contribute to inaction. Divisive politics undermine the validity of science, and together with social inequality, further exacerbate our ability to devise unified responses to address planetary emergencies (Dietz, Reference Dietz2020).

As a result, the urgency for immediate behavioural change still fails to have the desired effect on policy audiences and a substantial portion of the public (Fesenfeld & Rinscheid, Reference Fesenfeld and Rinscheid2021). The expected and necessary shift in policy towards sustainability remains out of reach, and denial has become or is causing a delay in addressing the planetary crises (Shue, Reference Shue2023) when acceptance of this urgency should cause an inverse positive societal response to bend the negative trajectories of loss and damage. The rate and extent of corrective societal action (policies, laws, practices, valorising local knowledge, etc.) should at least keep pace with the projected rate of loss and environmental degradation. How else can the planetary system be maintained and restored to a state conducive to continued human well-being? Accelerating action in the face of increasing urgency is a major societal challenge, especially considering the overwhelming evidence of anthropogenic impacts. Media and social platforms increasingly report on future projections and environmental scenarios. This includes discussions about the future state of coastal regions. The coast has always and will continue to attract humans impacted by current and future global and local changes (Lincke et al., Reference Lincke, Hinkel, Mengel and Nicholls2022; McMichael et al., Reference McMichael, Dasgupta, Ayeb-Karlsson and Kelman2020).

In this perspective, we propose that the scientific and societal challenges of Anthropocene coasts necessitate solutions that draw upon both old and new research realities, and a diversity of scientific disciplines and knowledge, while also engaging authentically and respectfully with society. Accordingly, we argue that new rationalities, inner logic, and hope are needed to achieve transformation to sustainable future coasts. This means new scientific reasoning is required to prepare for the future state of the coast. It is neither reasonable nor fair to expect an accepting societal response to knowledge production in which society has no meaningful stake. Science’s role and position in this context must be clarified, and outdated research cultures, priorities, and funding gaps rejected. The terms Global South and Global North are complex and often contested (Thérien, Reference Thérien2024). We use them thoughtfully, not to assert any stance, but to acknowledge the diverse and evolving narratives associated with these concepts.

2. Foundations for change: interconnectedness, the future, and responsibility

The scientific literature offers a foundation for urgent action, including filling the knowledge gaps to achieve coastal sustainability in the future. Firstly, despite the persistence of ‘terrestrial bias’ (Peters, Reference Peters2020), there is increasing recognition of the inseparability and connectedness of land, atmosphere and oceans, both in form and function. Any separation of the land surface from the ocean waters and the sea floor is a human construct only, deeply embedded in perceptions, legislation, and administration. Notably, many non-‘Western’ knowledge systems do not make such a separation but instead recognise for example a ‘sea-country’ (Whitehouse et al., Reference Whitehouse, Lui, Sellwood, Barrett and Chigeza2014). There is a land–ocean–atmosphere continuum regardless of the boundaries that we impose for convenience (Harvey & Clarke, Reference Harvey and Clarke2019; Rölfer et al., Reference Rölfer, Celliers and Abson2022a; Schlüter et al., Reference Schlüter, Van Assche, Hornidge and Văidianu2020). For this seamless transition between land, atmosphere, and ocean, we recognise a need to draw on diverse natural science, social science, and humanities disciplines (e.g. biology, ecology, physics, law, political sciences, governance, anthropology, sociology, and economy) to study the whole coast as an interconnected and seamless human-land-atmosphere-ocean system (B. Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Stocker, Coffey, Leith, Harvey, Baldwin, Baxter, Bruekers, Galano, Good, Haward, Hofmeester, De Freitas, Mumford, Nursey-Bray, Kriwoken, Shaw, Shaw, Smith and Cannard2013; Rosendo et al., Reference Rosendo, Celliers and Mechisso2018; Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Hobday, Allison, Armitage, Brooks, Bundy, Cvitanovic, Dickey-Collas, D. M. Grilli, Gomez, Jarre, Kaikkonen, Kelly, López, Muhl, Pennino, Tam and van Putten2021). This will require innovation within and across disciplines, together with a willingness of all actors to engage in research that pushes disciplinary and scientific boundaries. Beyond diversifying and combining disciplinary research, we further recognise the need for the uptake of research that addresses these complex, real-world challenges by integrating the diversity of knowledge and involving those affected or taking action in the research process (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Williams, Nanz and Renn2022; Renn, Reference Renn2021).

Secondly, there is an emergence of an orientation towards the future in science and society. ‘Future’ is an operative word that evokes uncertainty about every aspect of human existence, from health to security and home, to well-being and comfort. A search of the Scopus database of publicationsFootnote 1 reveals an exponential growth of articles dealing with ‘coast’ and ‘future’ from 2000 (176) to 2022 (1225, see also Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Riechers, Celliers and Ferse2023). Coastal scholars recognise the significance of the concept of the ‘future’, and are actively integrating it into their research and scholarly work (Farbotko et al., Reference Farbotko, Boas, Dahm, Kitara, Lusama and Tanielu2023; Gaill et al., Reference Gaill, Rudolph, Lebleu, Allemand, Blasiak, Cheung, Claudet, Gerhardinger, Bris, Levin, Pörtner, Visbeck, Zivian, Bahurel, Bopp, Bowler, Chlous, Cury, Gascuel and d'Arvor2022; Harmáčková et al., Reference Harmáčková, Yoshida, Sitas, Mannetti, Martin, Kumar, Berbés-Blázquez, Collins, Eisenack, Guimaraes, Heras, Nelson, Niamir, Ravera, Ruiz-Mallén and O'Farrell2023; Obura et al., Reference Obura, DeClerck, Verburg, Gupta, Abrams, Bai, Bunn, Ebi, Gifford, Gordon, Jacobson, Lenton, Liverman, Mohamed, Prodani, Rocha, Rockström, Sakschewski, Stewart-Koster and Zimm2023; Pace et al., Reference Pace, Saritas and Deidun2023). The UN’s Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals, the Paris Agreement and many other global policy objectives refer to key targets to be achieved in the future, or loss and damage to be mitigated (e.g. by the middle or end of the century). The science we produce is increasingly used to understand the future world based on the current trajectories of change and the policy efforts to reduce crises (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Mackay, Novaglio, Fullbrook, Murunga, Sbrocchi, McDonald, McCormack, Alexander, Fudge, Goldsworthy, Boschetti, Dutton, Dutra, McGee, Rousseau, Spain, Stephenson, Vince and Haward2022; Tosca et al., Reference Tosca, Galvin, Gilbert, Walls, Tyler and Nastan2021; Wyborn et al., Reference Wyborn, Davila, Pereira, Lim, Alvarez, Henderson, Luers, Harms, Maze, Montana, Ryan, Sandbrook, Shaw and Woods2020). According to Knappe et al. (Reference Knappe, Holfelder, Löw Beer and Nanz2019), ‘future-making practices’ are social and political efforts that build relationships or allude to things yet to come. Understanding the dynamics between knowledge and power in future-making practices in marine science can reveal whether this field promotes or obstructs progress towards sustainability. See, for example Nightingale et al. (Reference Nightingale, Eriksen, Taylor, Forsyth, Pelling, Newsham, Boyd, Brown, Harvey, Jones, Kerr, Mehta, Naess, Ockwell, Scoones, Tanner and Whitfield2019), those who propose placing values, normative commitments, and experiential and plural ways of knowing from around the world at the centre of climate knowledge. Hobday et al. (Reference Hobday, Hartog, Manderson, Mills, Oliver, Pershing, Siedlecki and Browman2019) developed a set of ten principles for ethical forecasting, including a focus on co-creation and participation.

Thirdly, there is a need for actionable science and policy and receptive communities that demand tangible outcomes that are not imposed on, but co-created with, societal actors (Celliers et al., Reference Celliers, Mañez Costa, Rölfer, Aswani and Ferse2023a; Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Wyborn, Klenk, Ryan, Serban, Bennett, Brennan, Charli-Joseph, Fernández-Giménez, Galvin, Goldstein, Haller, Hill, Munera, Nel, Österblom, Reid, Riechers, Spierenburg and Rondeau2022; Weiand et al., Reference Weiand, Unger, Rochette, Müller and Neumann2021). This could be described as a ‘coupled dance between human decisions and coastal environmental change’ (Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Adams, Tissier, Murray and Splinter2023, p.3). It is known that decelerating and halting the transgression of key planetary tipping points serves the public good and requires multi-level, distributed, fair and proportional action by all (i.e. Common But Differentiated Responsibility) (Blankespoor et al., Reference Blankespoor, Dasgupta, Wheeler, Jeuken, Van Ginkel, Hill and Hirschfeld2023). Furthermore, the assumption of the validity and adequacy of scientific data and information in the absence of knowledge co-production by decision-makers, policy-makers, the private sector, and civil society is not tenable (Celliers et al., Reference Celliers, Costa, Williams and Rosendo2021; Miner et al., Reference Miner, Canavera, Gonet, Luis, Maddox, Mccarney, Bridge, Schimel and Rattlingleaf2023). The exploration of future approaches combined with transdisciplinary co-production is creating a surge of interest in breaking down the power dynamics afflicting academia, between science and society, within academia, and amongst ‘Western”’Cartesian and other knowledge systems. Transdisciplinarity is an approach that normalises collaborative processes involving academic and non-academic actors, aims to balance power dynamics in knowledge production, and results in solutions for societal challenges (see e.g. Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Williams, Nanz and Renn2022). Transdisciplinarity, as a product of science embedded in and informed by society, is an opportunity to explore collective human action towards novel solutions.

3. Towards a transformed future

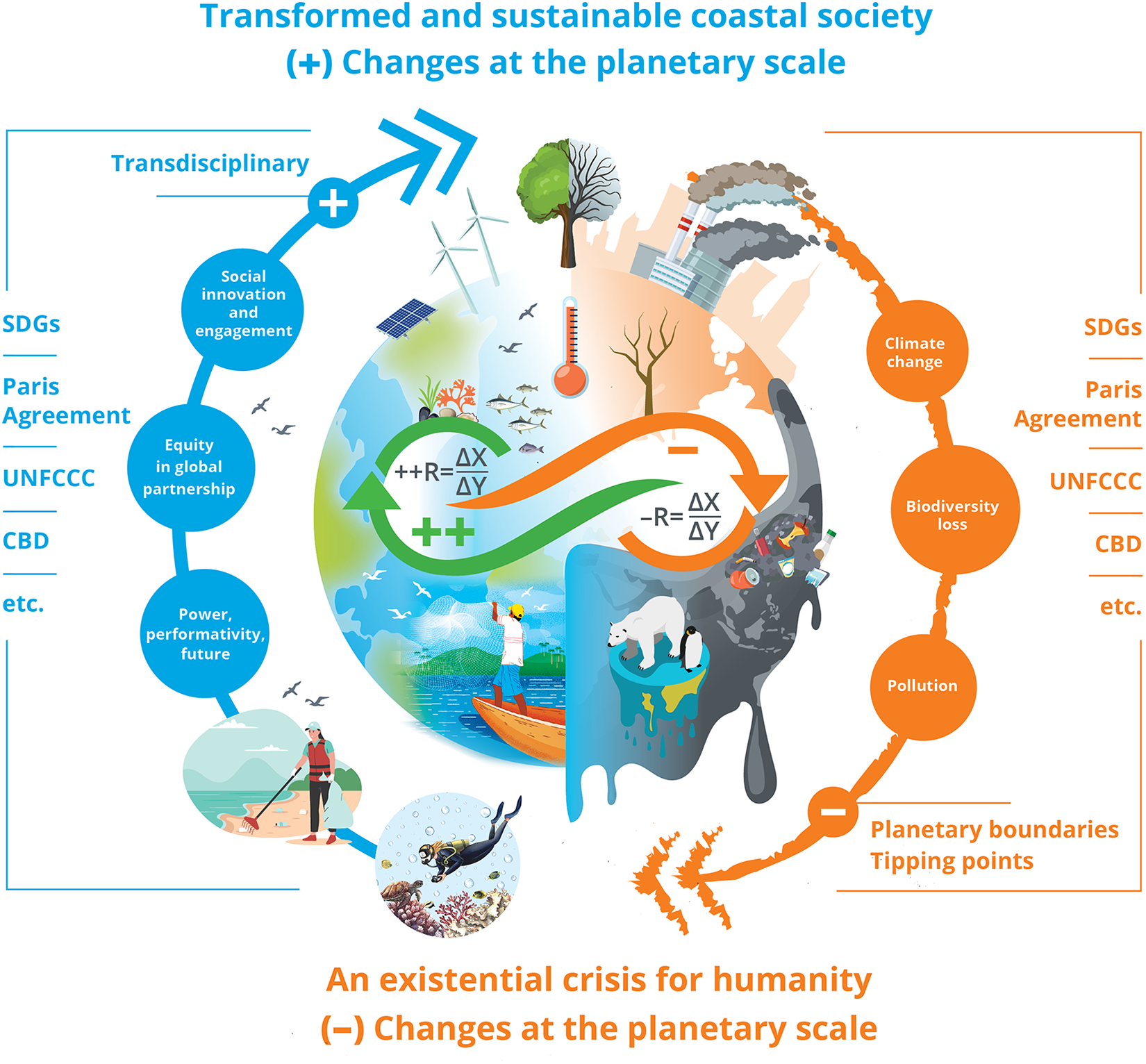

In this paper, we offer three propositions to accelerate urgent actions, foster innovation in coastal research, and focus on emerging trends and foundational changes (Figure 1).

Proposition 1: Scientists urgently need to reflect on the performativity of their research and perceptions of neutrality in anticipating the future of coasts.

Figure 1. Three propositions (solid blue circles) of the new role of science to contribute to a pathway of transformation to a sustainable and human-positive environment where the observed negative trends (−R) in planetary crises (solid orange circles) are reversed by at least equally positive rates of change (++R) in societal action to avoid an existential crisis for humanity.

Science actively shapes the world through its theories, analytical practices and discourses. This perspective comes from fields such as Science and Technology Studies and Political Ecology, where scholars argue that science does not simply discover facts about nature, but constructs knowledge through interactions and institutional processes. Reflexivity in science – science actors who are conscious of their position – recognises the real-world consequences and societal uses of the outputs of the science process. This concept, known as performativity, promotes critical reflection on how knowledge is created, by whom, and for whose benefit it is ultimately applied (Bruns, Reference Bruns, Gottschlich, Hackfort, Schmitt and von Winterfeld2022).

Some key questions triggered by the performativity of science are: How does scientific theory, underpinned by data and information about climate change, pollution or biodiversity loss, shape the actions of coastal communities (Bowden et al., Reference Bowden, Gond, Nyberg and Wright2021)? Through which actions and by which actors can the language of coastal research function as a form of social action and effect change? Furthermore, research practices, paradigms, methodologies, scientific papers, databases, models, and scenarios can be described as future objects. These future objects have components of knowledge and material, playing a significant role in the socio-material politics of anticipation (Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2017; Esguerra, Reference Esguerra2019). As Esguerra (Reference Esguerra2019) argued, future objects are governed by varying objectives, offering options for political participation at different levels and in diverse ways. Creating futures involves material actions and epistemic descriptions, and understanding their interplay is crucial. Incorporating anticipation and foresight in transdisciplinary research may enable the realisation or advancement of creative and sustainable futures (Baumann et al., Reference Baumann, Riechers, Celliers and Ferse2023), moving away from path dependencies created by continuing consumption and the hegemony of economic growth that further entrench the human dilemma (Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2017).

Thus, anticipation, or the growing political demand for sustainability pathways, requires rethinking beyond expert-driven neutral input. Beck and Mahony (Reference Beck and Mahony2017) suggest that ‘…forecasters themselves should be asked to anticipate the political impacts of their forecasts’ (p. 312). The implication is that experts should be aware of, and willing to engage with the many ways in which the best-intended data and information may have distinctly different meanings for societal users. Concomitantly, coastal and marine research requires innovative and brave approaches to conceptualising and studying the connections between society, nature, and the future (heuristics, concepts, methods). Studying the future of coastal areas requires making assumptions and framings that contribute to and construct varying perspectives of coasts as human-nature systems of the future.

However, there is often a lack of transparency and reflection on current approaches to scientific research and how they contribute to shaping the future. A more reflexive approach will make different epistemological and ontological assumptions more transparent. Some of the key aspects include ideas about economic growth and how growth paradigms are often taken for granted in the scenario-building process (Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2017). The science of future coasts and its many different disciplines needs to reflect on the choice, nature and use of methods and approaches: The scientific community must mirror their assumptions in an accessible and transparent way, which is time-consuming and requires novel formats and reflexive spaces in research practices. The predominant Western understanding and design of the science process and its social and political context may not lend itself to achieving more sustainable coasts at the global scale. Other forms of knowledge and knowledge cultures must be recognised – this is epistemological inclusion. Concomitantly, other life-world experiences and lifestyles, i.e. the coexistence of multiple ways of conceptualising and explaining the world or specific phenomena, must be included in future coastal science – this is ontological pluralism (Nightingale et al., Reference Nightingale, Eriksen, Taylor, Forsyth, Pelling, Newsham, Boyd, Brown, Harvey, Jones, Kerr, Mehta, Naess, Ockwell, Scoones, Tanner and Whitfield2019).

We support the call for radical structural change and societal transformation and urge the inclusion of the scientific system in this transformation as part of society. It offers innovative perspectives for conceptualising, studying and designing societal futures as part of nurturing nature. Yet, the current scientific system, including its funding structures, often impedes the reality of such research approaches (Fam et al., Reference Fam, Clarke, Freeth, Derwort, Klaniecki, Kater‐Wettstädt, Juarez‐Bourke, Hilser, Peukert, Meyer and Horcea‐Milcu2019). For example, scientific reflexivity is frequently met with reluctance by funders, while time or resource constraints marginalise structured reflection processes as part of the full research process. Reflexivity and learning are particularly challenging in inter- and transdisciplinary settings where more time and resources are required to achieve cognitive, normative, and relational learning as prerequisites for shifting values, enhanced trust and cooperation (Baird et al., Reference Baird, Plummer, Haug and Huitema2014). This causes imbalance, resulting in unsatisfactory cooperation and outcomes, often leading to misunderstandings regarding communication, acceptance, and the transformative roles of science.

Furthermore, scholarship on the critical role of social sciences in climate change adaptation is rapidly evolving. Climate change adaptation constitutes a political concept and discourse of tangible material consequences, including infrastructure development (Colloff et al., Reference Colloff, Martín-López, Lavorel, Locatelli, Gorddard, Longaretti, Walters, van Kerkhoff, Wyborn, Coreau, Wise, Dunlop, Degeorges, Grantham, Overton, Williams, Doherty, Capon, Sanderson and Murphy2017; Eisenack & Paschen, Reference Eisenack and Paschen2022) and change to ecosystems (e.g. blue carbon) and associated human benefits (Fink & Ratter, Reference Fink and Ratter2024). Nevertheless, most discussions on adaptation are frequently criticised for being apolitically framed, despite their noticeable political impacts. For example, many international cooperation programmes for adaptation are steeped in technical and managerial terms (Cameron, Reference Cameron2012; Keele, Reference Keele2019) that lack cultural, social, and political diversity and ontological pluralism (Nightingale et al., Reference Nightingale, Eriksen, Taylor, Forsyth, Pelling, Newsham, Boyd, Brown, Harvey, Jones, Kerr, Mehta, Naess, Ockwell, Scoones, Tanner and Whitfield2019). Moreover, social inequalities that limit adaptation or adaptation options are often disregarded or even reinforced (Klepp & Chavez-Rodriguez, Reference Klepp and Chavez-Rodriguez2018). Such apolitical approaches in adaptation projects, e.g. in the context of international cooperation, might be understood as future un-making approaches. Futures that are envisioned as undesirable, shall be prevented by adaptation measures.

Finally, critical research on global change argues that transformation towards sustainability is more urgent than ever. However, a large part of research still relies on underlying framings that support the status quo (Castree, Reference Castree2022; Nightingale et al., Reference Nightingale, Gonda and Eriksen2021; Wiegleb & Bruns, Reference Wiegleb and Bruns2025). These techno-scientific frameworks dominate eco-modernist discourses, exemplified by the term ‘blue economy’ (see Proposition 2). As such, they strongly influence current policies and politics of adaptation and sustainability, while critical and diverse social science research is not equally considered.

Proposition 2: Scientists must think and act equitably in global partnerships

Research agendas, as well as future development plans and purported solution spaces, are still predominantly shaped in the Global North, even if they address and affect the lives of people in the Global South (Henrich et al., Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010; Miller et al., Reference Miller, White and Christie2023; Spalding et al., Reference Spalding, Grorud-Colvert, Allison, Amon, Collin, de Vos, Friedlander, Johnson, Mayorga, Paris, Scott, Suman, Estradivari, Giron-Nava, Gurney, Harris, Hicks, Mangubhai, Micheli and Thurber2023; Wiegleb & Bruns, Reference Wiegleb and Bruns2018). Using contemporary narratives such as ‘blue economy’ or ‘blue carbon’ often reflects the political agendas of the Global North and industries (Schutter et al., Reference Schutter, Hicks, Phelps and Waterton2021), and other political agendas. We thus see a need to accommodate and integrate multiple, pluralistic visions for a common future beyond the normative guidance of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It is also necessary to have a much more significant role of Global South actors and perspectives in research collaborations, while also considering the disparities in resources (Armenteras, Reference Armenteras2021; Costello & Zumla, Reference Costello and Zumla2000). A critical evaluation of who is responsible for defining and setting agendas is part of this conversation. Scientists and research organisations, particularly in the Global North, have a greater responsibility to contribute to research ethics, science diplomacy, and communication (Lahl et al., Reference Lahl, Ferse, Bleischwitz, Ittekkot and Baweja2023; Partelow et al., Reference Partelow, Hornidge, Senff, Stabler and Schluter2020a; Schroeder et al., Reference Schroeder, Chatfield, Singh, Chennells and Herissone-Kelly2019). We see four interrelated aspects to consider for coastal research in global partnerships: (i) the role of science in society; (ii) identification and definition of topics; (iii) modes of research and collaboration; and (iv) employment and funding structure.

Perspectives vary regarding the role of science in society. While basic research is the gold standard, applied research is often neglected. This tension is particularly relevant in a North–South perspective: We see a tendency that wealthy countries in the Global North value basic and curiosity-driven research more highly, holding academic freedom in high regard. In contrast, the reality in many countries in the Global South is different. For example, it is often expected that public servants and researchers serve society and applied research is the norm (e.g. Siregar, Reference Siregar, Kraemer-Mbula, Tijssen, Wallace and McClean2019). National differences in scientific knowledge production create cultural and political path dependencies within academic systems (Castro Torres & Alburez-Gutierrez, Reference Castro Torres and Alburez-Gutierrez2022; Partelow et al., Reference Partelow, Schlüter, Armitage, Bavinck, Carlisle, Gruby, Hornidge, Tissier, Pittman, Song, Sousa, Văidianu and Van Assche2020b). As such, North–South scientific collaboration should consider and respect the significance of local applications of science as a tool for development, and the extent of its role in collaborative research settings.

Variations in scientific structures also affect which topics are prioritised for research (and funding). The societal relevance of research and its impact are receiving increasing attention in Western academic systems and research funding (Woolston, Reference Woolston2023). This suggests a favourable environment for addressing topics of societal relevance, including in and with countries of the Global South and strengthening South–South relations (Calderón-Contreras et al., Reference Calderón-Contreras, Balvanera, Trimble, Langle-Flores, Jobbágy, Moreno, Marcone, Mazzeo, Muñoz Anaya, Ortiz-Rodríguez, Perevochtchikova, Avila-Foucat, Bonilla-Moheno, Clark, Equihua, Ayala-Orozco, Bueno, Hensler, Aguilera and Velázquez2021). However, trans- and interdisciplinarity still face significant obstacles (Scholz & Steiner, Reference Scholz and Steiner2015; Staffa et al., Reference Staffa, Riechers and Martin-Lopez2022), including project assessments that do not respect the interdisciplinary nature of research activities, and funding institutions that are not designed to facilitate real engagement. The criteria for scientific excellence and measuring the priority of societal impact may need to be revised (Kraemer-Mbula et al., Reference Kraemer-Mbula, Tijssen, Wallace and McClean2020). Prioritising academic excellence can lead to the exclusion of inter- and transdisciplinary approaches, isolating disciplines and excluding local partners. Collaborations between scientists in the Global North and Global South require equality and mutual listening, but rigid funding structures often hinder adaptability and prioritise rapid, high-profile results (Scholz & Steiner, Reference Scholz and Steiner2015). Additionally, there is a lack of guidelines to fairly evaluate project design and quality, and its potential for real-world influence and impact, emphasising the importance of better aligning projects to local necessities and situations.

These points indicate the need to reconsider modes of collaboration and funding practices. The embrace of transdisciplinary co-production throughout the research lifecycle will enable long-term science-society partnerships and minimise the practice of ‘parachute’ science (Bieler et al., Reference Bieler, Bister, Hauer, Klausner, Niewöhner, Schmid and von Peter2020; Gewin, Reference Gewin2023). We perceive an imperative to empower Global South actors with a more authoritative and independent role in shaping collaborations and setting agendas, ensuring equitable participation and influence. This should include the creation of a level playing field, as well as much greater receptiveness both in science and policy to equitable co-creation of knowledge, including learning from the Global South. Commitment in the long term is pivotal to the success of any project, while shorter-term projects can also positively impact society both in the Global South and the Global North. Therefore, these projects need to be designed to ensure long-lasting societal impacts (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Bharadwaj, Fransman, Georgalakis and Rose2019). Transdisciplinarity addresses not only the integration of knowledge but also the connection between people. This results in societal impact, legacy structures, and communities of practice (Norström et al., Reference Norström, Cvitanovic, Löf, West, Wyborn, Balvanera, Bednarek, Bennett, Biggs, de Bremond, Campbell, Canadell, Carpenter, Folke, Fulton, Gaffney, Gelcich, Jouffray, Leach and Österblom2020). Systematically involving a wider range of actors reduces the risk of duplicated efforts (Celliers et al., Reference Celliers, Rölfer, Rivers, Rosendo, Fernandes, Snow and Costa2023b). The intangible aspect of community building in transdisciplinary collaborations is significant as it institutionalises networks. To establish a functional community that includes diverse actors, ranging from early career researchers to senior scientists, policy-makers and other stakeholders, it is essential to have sufficient time, mutual respect, acknowledgement of each other’s roles, and adequate support, resulting in synergetic partnerships (Rölfer et al., Reference Rölfer, Ilosvay, Ferse, Jung, Karcher, Kriegl, Nijamdeen, Riechers and Walker2022b).

In many countries within the Global South, the lack of capacity may be less of an issue than a lack of job prospects and long-term employment, resulting in ‘human capital flight’ (Talavera-Soza, Reference Talavera-Soza2023). Moreover, in Global South countries, the institutional framework is frequently inadequate to enable events that are possible in Global North environments (i.e. meetings and training). We argue that these institutional constraints demand ongoing support and funding from the Global North. Additionally, it is important to challenge the prevailing narrative that Global North countries are always superior in aspects such as training, writing, and analyses, and instead highlight the strengths of partner countries in the Global South and empower south-to-south and south-to-north collaborations (Norström et al., Reference Norström, Agarwal, Balvanera, Baptiste, Bennett, Brondízio, Biggs, Campbell, Carpenter, Castilla, Castro, Cramer, Cumming, Felipe-Lucia, Fischer, Folke, DeFries, Gelcich, Groth and Spierenburg2022) These aspects can be partially addressed by mutual project design, training programmes at local universities, employing local staff for research positions, dedicating time to mentor local students, and gaining familiarity with the local academic and cultural context. It is vital to consider research partners as equitable collaborators rather than mere facilitators, e.g. sharing the hosting of international meetings (Armenteras, Reference Armenteras2021; Asase et al., Reference Asase, Mzumara‐Gawa, Owino, Peterson and Saupe2021; Haelewaters et al., Reference Haelewaters, Hofmann and Romero-Olivares2021).

Proposition 3: Scientists must improve their engagement and willingness to innovate with society

Science should find its appropriate place amongst the many unmanageable and intangible elements or actions that constitute social innovation. Science alone is insufficient for dealing with challenges such as the 1.5°C warming limit, biodiversity and pollution crises, and societal transformation towards sustainability. We need to acknowledge the importance of integrating beyond obvious scientific disciplines, promoting collaboration, and exploring mixed methods and novel approaches to enhance the use of scientific evidence in complex coastal systems.

Stakeholder engagement, social innovation, and transdisciplinarity are closely linked with issues related to capacity strengthening. Critics argue that despite transdisciplinary approaches, integrating disciplines and mixed methods for addressing complex societal challenges, which transdisciplinarity is best applied for, is unlikely to be perfect. At a fundamental level, this issue relates to the definition of transdisciplinarity and its theoretical development, as well as the practice of transdisciplinarity as an inclusive and open philosophy. Transdisciplinarity is not merely a linear improvement or evolution from interdisciplinarity. It represents a paradigm shift in stakeholder engagement with which to address complex societal challenges. With its focus on societally relevant problems and aim of creating solution-oriented knowledge, transdisciplinarity, despite the challenges it comes with, holds tremendous potential to contribute to societal and sustainability transformations (Lang et al., Reference Lang, Wiek, Bergmann, Stauffacher, Martens, Moll, Swilling and Thomas2012). It also has great potential for bridging the science–policy–society divide and producing actionable science that supports pathways to transformation.

Which scientific disciplines and sectors of society form the foundation for the sustainable transformation of coasts? Transdisciplinarity is an approach that stems from a specific mindset or philosophy. Older concepts such as ‘polymath’ or ‘generalist’ can partly align with modern interpretations of a transdisciplinary scientist. The practice of transdisciplinarity is dynamic, highly contextual, and involves frequently changing targets and shifting objectives. Fundamental questions have been raised regarding the philosophical nature (i.e. the systematic study of general and fundamental questions) of transdisciplinarity. Emotion and emotional intelligence comprise critical components of a transdisciplinary approach (Horcea-Milcu et al., Reference Horcea-Milcu, Leventon and Lang2022). Leadership in transdisciplinary processes is shaped by personality traits, emotional range and depth, and character (Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Wyborn, Klenk, Ryan, Serban, Bennett, Brennan, Charli-Joseph, Fernández-Giménez, Galvin, Goldstein, Haller, Hill, Munera, Nel, Österblom, Reid, Riechers, Spierenburg and Rondeau2022). This indicates that a transdisciplinary paradigm serves as a philosophical and theoretical framework. Complex problems and challenges best suited for transdisciplinarity, such as those frequently encountered in coastal systems (Jentoft & Chuenpagdee, Reference Jentoft and Chuenpagdee2009), do not have a formulaic solution. Often, these challenges are wicked, i.e. a set of interconnected problems that cannot be solved or diagnosed in isolation, as this would only result in a new set of problems (Wohlgezogen et al., Reference Wohlgezogen, McCabe, Osegowitsch and Mol2020). Many coastal challenges fall in this category, as does climate change. Addressing wicked problems requires a collaborative and dynamic approach that involves the actors in the process (Binder et al., Reference Binder, Absenger-Helmli and Schilling2015) and is designed to enable societal learning that can lead to transformation, i.e. a more fundamental change of paradigm and underlying structures, values, and power dynamics (Pahl-Wostl, Reference Pahl-Wostl2009). For this to occur, collaborative processes require openness instead of attempting to control and own the process.

Transdisciplinarity involves engaging with society (including stakeholders) to address issues that affect the process participants. In this context, ‘ownership’ refers to those who initiate a transdisciplinary process to address a societal challenge that necessitates input and action from various stakeholders (including scientists). A transdisciplinary process may yield a solution in which science provides limited input. Do scientists act as ‘honest brokers’ for the transdisciplinary process to resolve such wicked problems? Can transdisciplinarity be a no-regrets process that non-science actors can initiate and govern? Does a transdisciplinary process still count as one if it lacks any scientific ‘oversight’? And what qualities and outcomes are indicative of a successful transdisciplinary process that has transformative impacts?

What is the relationship between institutional agency and ownership of challenges that generally require a transdisciplinary approach? When transdisciplinary research better defines ownership of solutions, transferring responsibility becomes clearer after proposing a solution. When adaptation actions depend on actors such as municipalities, transdisciplinary processes must involve problem owners alongside knowledge creators and holders. The challenges of solution ownership relate to our understanding of transdisciplinarity as a practice, distinct from the supporting theory. Many adaptation challenges can and should be addressed through self-organisation in society and communities. In such self-organising initiatives, the role of science and scientists can vary widely, from providing scientific input to initiating, facilitating or observing the process. To some extent, the concepts or philosophies that are the foundation of transdisciplinarity necessitate novel forms of power, equality or democracy of voices. The discussion around the ownership of transdisciplinarity and its practical implementation, as well as its underlying theory, brings up issues of how to steer and guarantee the quality of the process.

4. A way forward

As a society in the Anthropocene, we are challenged to respond to the urgency of the triple planetary crisis. The relationship between society and science drives progress and shapes our collective future. The science–society binary is a social misconception. Science is a systematic pursuit of knowledge to explain and understand the natural and social world. The great reversal from rationality to sentimentality in fact-based arguments (Scheffer et al., Reference Scheffer, van de Leemput, Weinans and Bollen2021) is happening simultaneously with the need for evidence-based solutions to existential threats of the Anthropocene. The greater sense of sentimentality of contemporary society does not need to be a barrier to scientific progress in support of the transformation to environmental sustainability and socio-ecological harmony. Acknowledging and engaging with emotions, particularly at the local scale, is essential to move towards constructive societal action and empowerment. We must reconsider and adapt our practices to the shifting nature of contemporary society. In a more connected world, with society facing new uncertainties (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2022), we should guard against using knowledge as a means to exert power. Faced with the dangerous change in the Anthropocene, sweeping societal transformations and widespread intensification of polarisation, the role of science and its practice is facing a new challenge of, if not relevance, a new science–society contract (Huntjens, Reference Huntjens2021; Lubchenco, Reference Lubchenco1998). This contract is more than ‘just’ adding co-production with society, improving the dissemination of science products or more appropriate communication. In this perspective, we argue for a systemic change in science and how it is practised within society.

We already have a foundation for addressing coastal sustainability. The artificial separation between land and ocean is a human construct. To study the entire coast as an integrated system, we must combine diverse disciplines, including natural science, social science, and humanities. The concept of the ‘future’ is gaining prominence in science and society and is especially relevant in the context of coastal change. Understanding the dynamics between knowledge and power in future-making practices can reveal whether marine and coastal science promotes sustainability. Ethical forecasting principles, including co-creation and participation, are increasingly shaping our future and should be prominent. There is evidence for transdisciplinary co-production breaking down or reducing power dynamics within academia and fostering collective design of novel solutions. Enhancing transdisciplinary research to support coastal adaptation involves tapping into the wealth of insights accumulated over decades in social sciences, action research, and transdisciplinarity. Much of this valuable knowledge has thus far been overlooked in the coastal adaptation literature.

We emphasise the need for radical structural change and societal transformation to achieve coastal sustainability, including within the scientific system. Inter- and transdisciplinary research provides fresh perspectives for understanding the interaction between society and nature. However, the existing scientific system, including its funding mechanisms, often hinders the implementation of such research approaches. Effective collaborations between scientists from the Global North and Global South necessitate an ethos of equality, active listening, and adaptability. Unfortunately, rigid and competitive funding structures often prioritise rapid, high-profile outcomes, hindering this collaborative spirit. Mutual funding is essential for strong partnerships. There is also a lack of guidelines for evaluating project design considering real-world impact, highlighting the need to align projects with local needs and contexts. Transdisciplinarity, which engages science and scientists with diverse actors and realities, goes beyond a simple progression from interdisciplinarity. It signifies a paradigm shift in how stakeholders engage to tackle complex societal challenges. Transdisciplinarity drives societal and sustainability transformations by focusing on real-world problems and generating solution-oriented knowledge.

Transdisciplinary research aims to incorporate co-design, but funding mechanisms often neglect the implementation phase. To improve this, funding agendas should align with priorities and be transparent. Prioritisation should involve both scientists and societal stakeholders. Some challenges require long-term, programmatic funding. Projects with added value (e.g. transformation precursors) should have scope for continuation funding. Diverse review panels, emphasising social science and transdisciplinary expertise, are essential. Developing quality criteria and metrics will enable evaluating actionable coastal research in grant proposals and measuring success.

We emphasise the importance of transdisciplinary approaches for achieving greater sustainability and societal impact of science. It is time to establish a science-society publication process to review such outputs. Currently, there is growing concern about the traditional scientific peer-review process. One potential solution could be a tiered system where disciplinary outputs, e.g. from physics or ecology research, would undergo classical peer review. Interdisciplinary papers would be assessed for the quality of integration and potential real-world applications. Finally, transdisciplinary publications would be evaluated by both scientific and societal actors to consider outcomes and impact achieved through the research.

Promoting and enabling transdisciplinary coastal research requires clear career perspectives for researchers engaged in such work. However, subsequent career paths (e.g. tenure tracks and professorships) must also be considered. Despite a focus on disciplinary careers within academia, there is increasing demand for transdisciplinary expertise and societal impact literacy. Funders should support capacity development for established researchers and incentivise transdisciplinary approaches (e.g. co-design) in funding calls.

The authors acknowledge that this paper may overlook or exclude several other critical future-oriented aspects, such as governance requirements for emerging systems (Andrijevic et al., Reference Andrijevic, Cuaresma, Muttarak and Schleussner2019; Celliers et al., Reference Celliers, Mañez Costa, Rölfer, Aswani and Ferse2023a). However, this does not diminish the significance of these elements for social innovation. The focus of this paper was intentionally aligned with the propositions outlined by the authors as part of the supporting project.

1. Coastal crisis

In the Anthropocene (Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Rockström, Richardson, Lenton, Folke, Liverman, Summerhayes, Barnosky, Cornell, Crucifix, Donges, Fetzer, Lade, Scheffer, Winkelmann and Schellnhuber2018), we face three urgent global challenges – a triple planetary emergency (Guterres, Reference Guterres2020). These are climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss. These human-induced emergencies are relentlessly driving the planetary system towards tipping points and changes, making our continued existence less safe (Rockström et al., Reference Rockström, Gupta, Qin, Lade, Abrams, Andersen, Mckay, Bai, Bala, Bunn, Ciobanu, Declerck, Ebi, Gifford, Gordon, Hasan, Kanie, Lenton, Loriani and Zhang2023; Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Rockström, Richardson, Lenton, Folke, Liverman, Summerhayes, Barnosky, Cornell, Crucifix, Donges, Fetzer, Lade, Scheffer, Winkelmann and Schellnhuber2018), including through potentially irreversible shifts in the Earth system’s components and processes (Lenton et al., Reference Lenton, Rockstrom, Gaffney, Rahmstorf, Richardson, Steffen and Schellnhuber2019; Rockstrom et al., Reference Rockstrom, Kotze, Milutinovic, Biermann, Brovkin, Donges, Ebbesson, French, Gupta, Kim, Lenton, Lenzi, Nakicenovic, Neumann, Schuppert, Winkelmann, Bosselmann, Folke, Lucht and Steffen2024). In the coastal zone, the triple planetary crisis manifests as accelerating losses and changes (Halpern et al., Reference Halpern, Frazier, Afflerbach, Lowndes, Micheli, O'Hara, Scarborough and Selkoe2019) with negative consequences for human communities and societies. The escalating pace of global warming (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Péan, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekçi, Yu and Zhou2021; Johnson & Lyman, Reference Johnson and Lyman2020), the rise in sea levels (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Karpytchev and Hu2023; Nicholls et al., Reference Nicholls, Lincke, Hinkel, Brown, Vafeidis, Meyssignac, Hanson, Merkens and Fang2021), the loss of biodiversity (Jaureguiberry et al., Reference Jaureguiberry, Titeux, Wiemers, Bowler, Coscieme, Golden, Guerra, Jacob, Takahashi, Settele, Diaz, Molnar and Purvis2022; Penn & Deutsch, Reference Penn and Deutsch2022), especially the loss of coral reefs (Eddy et al., Reference Eddy, Lam, Reygondeau, Cisneros-Montemayor, Greer, Palomares, Bruno, Ota and Cheung2021), sandy beaches (Brooks, Reference Brooks2020; Luijendijk et al., Reference Luijendijk, Hagenaars, Ranasinghe, Baart, Donchyts and Aarninkhof2018), deltas (Anthony et al., Reference Anthony, Syvitski, Zăinescu, Nicholls, Cohen, Marriner, Saito, Day, Minderhoud, Amorosi, Chen, Morhange, Tamura, Vespremeanu-Stroe, Besset, Sabatier, Kaniewski and Maselli2024), seagrass (Dunic et al., Reference Dunic, Brown, Connolly, Turschwell and Côté2021), and mangrove cover (Bryan-Brown et al., Reference Bryan-Brown, Connolly, Richards, Adame, Friess and Brown2020; Otero et al., Reference Otero, Quisthoudt, Koedam and Dahdouh-Guebas2016), as well as ocean pollution (Jouffray et al., Reference Jouffray, Blasiak, Norström, Österblom and Nyström2020; Landrigan et al., Reference Landrigan, Stegeman, Fleming, Allemand, Anderson, Backer, Brucker-Davis, Chevalier, Corra, Czerucka, Bottein, Demeneix, Depledge, Deheyn, Dorman, Fenichel, Fisher, Gaill, Galgani and Rampal2020; Riechers et al., Reference Riechers, Brunner, Dajka, Duse, Lubker, Manlosa, Sala, Schaal and Weidlich2021), are some of the scientifically confirmed trajectories that confront us. These manifest as potentially critical impacts on coastal communities and their livelihoods that demand societal responses at all levels (Cinner et al., Reference Cinner, Caldwell, Thiault, Ben, Blanchard, Coll, Diedrich, Eddy, Everett, Folberth, Gascuel, Guiet, Gurney, Heneghan, Jägermeyr, Jiddawi, Lahari, Kuange, Liu and Pollnac2022; Gill et al., Reference Gill, Blythe, Bennett, Evans, Brown, Turner, Baggio, Baker, Ban, Brun, Claudet, Darling, Di Franco, Estradivari, Gray, Gurney, Horan, Jupiter, Lau and Muthiga2023)

There is a groundswell of scientific evidence that urges immediate action (IPBES, Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo, Guèze, Agard, Arneth, Balvanera, Brauman, Butchart, Chan, Garibaldi, Ichii, Liu, Subramanian, Midgley, Miloslavich, Molnár, Obura and Pfaff2019; IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Péan, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekçi, Yu and Zhou2021, Reference Pörtner, Roberts, Poloczanska, Mintenbeck, Tignor, Alegría, Craig, Langsdorf, Löschke, Möller and Okem2022). The actions necessary to maintain an Earth system supportive of human well-being are equally clear, e.g. to avert public health impacts from extreme events worsened by climate change (H. Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Cirulis, Borchers-Arriagada, Bradstock, Price and Penman2023; Salvador et al., Reference Salvador, Nieto, Vicente-Serrano, Garcia-Herrera, Gimeno and Vicedo-Cabrera2023). Global policy urges mitigation of greenhouse gases, adaptation to climate change, and social transformation that improve fairness, equality, and access to resources. Indeed, measured by the abundance and scope of global policies, agreements, commitments, and institutions, humanity is aware of adverse global change in the Anthropocene (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., Reference Hoegh-Guldberg, Jacob, Taylor, Bolanos, Bindi, Brown, Camilloni, Diedhiou, Djalante, Ebi, Engelbrecht, Guiot, Hijioka, Mehrotra, Hope, Payne, Portner, Seneviratne, Thomas and Zhou2019; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Raubenheimer, Urho, Unger, Azoulay, Farrelly, Sousa, van Asselt, Carlini, Sekomo, Schulte, Busch, Wienrich and Weiand2021; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Kohler, Lenton, Svenning and Scheffer2020). People are increasingly anxious about observable, extreme and large-scale changes (Kurth & Pihkala, Reference Kurth and Pihkala2022; Mortreux et al., Reference Mortreux, Barnett, Jarillo and Greenaway2023; Smith, Reference Smith2020; Van Valkengoed & Steg, Reference Van Valkengoed and Steg2023), and these anxieties surface in social and political discourse (Spence & Ogunbode, Reference Spence and Ogunbode2023). At the same time, powerful vested interests, political strategy and lobbying, fear, ignorance, religious fervour, feelings of despair, and being overwhelmed contribute to inaction. Divisive politics undermine the validity of science, and together with social inequality, further exacerbate our ability to devise unified responses to address planetary emergencies (Dietz, Reference Dietz2020).

As a result, the urgency for immediate behavioural change still fails to have the desired effect on policy audiences and a substantial portion of the public (Fesenfeld & Rinscheid, Reference Fesenfeld and Rinscheid2021). The expected and necessary shift in policy towards sustainability remains out of reach, and denial has become or is causing a delay in addressing the planetary crises (Shue, Reference Shue2023) when acceptance of this urgency should cause an inverse positive societal response to bend the negative trajectories of loss and damage. The rate and extent of corrective societal action (policies, laws, practices, valorising local knowledge, etc.) should at least keep pace with the projected rate of loss and environmental degradation. How else can the planetary system be maintained and restored to a state conducive to continued human well-being? Accelerating action in the face of increasing urgency is a major societal challenge, especially considering the overwhelming evidence of anthropogenic impacts. Media and social platforms increasingly report on future projections and environmental scenarios. This includes discussions about the future state of coastal regions. The coast has always and will continue to attract humans impacted by current and future global and local changes (Lincke et al., Reference Lincke, Hinkel, Mengel and Nicholls2022; McMichael et al., Reference McMichael, Dasgupta, Ayeb-Karlsson and Kelman2020).

In this perspective, we propose that the scientific and societal challenges of Anthropocene coasts necessitate solutions that draw upon both old and new research realities, and a diversity of scientific disciplines and knowledge, while also engaging authentically and respectfully with society. Accordingly, we argue that new rationalities, inner logic, and hope are needed to achieve transformation to sustainable future coasts. This means new scientific reasoning is required to prepare for the future state of the coast. It is neither reasonable nor fair to expect an accepting societal response to knowledge production in which society has no meaningful stake. Science’s role and position in this context must be clarified, and outdated research cultures, priorities, and funding gaps rejected. The terms Global South and Global North are complex and often contested (Thérien, Reference Thérien2024). We use them thoughtfully, not to assert any stance, but to acknowledge the diverse and evolving narratives associated with these concepts.

2. Foundations for change: interconnectedness, the future, and responsibility

The scientific literature offers a foundation for urgent action, including filling the knowledge gaps to achieve coastal sustainability in the future. Firstly, despite the persistence of ‘terrestrial bias’ (Peters, Reference Peters2020), there is increasing recognition of the inseparability and connectedness of land, atmosphere and oceans, both in form and function. Any separation of the land surface from the ocean waters and the sea floor is a human construct only, deeply embedded in perceptions, legislation, and administration. Notably, many non-‘Western’ knowledge systems do not make such a separation but instead recognise for example a ‘sea-country’ (Whitehouse et al., Reference Whitehouse, Lui, Sellwood, Barrett and Chigeza2014). There is a land–ocean–atmosphere continuum regardless of the boundaries that we impose for convenience (Harvey & Clarke, Reference Harvey and Clarke2019; Rölfer et al., Reference Rölfer, Celliers and Abson2022a; Schlüter et al., Reference Schlüter, Van Assche, Hornidge and Văidianu2020). For this seamless transition between land, atmosphere, and ocean, we recognise a need to draw on diverse natural science, social science, and humanities disciplines (e.g. biology, ecology, physics, law, political sciences, governance, anthropology, sociology, and economy) to study the whole coast as an interconnected and seamless human-land-atmosphere-ocean system (B. Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Stocker, Coffey, Leith, Harvey, Baldwin, Baxter, Bruekers, Galano, Good, Haward, Hofmeester, De Freitas, Mumford, Nursey-Bray, Kriwoken, Shaw, Shaw, Smith and Cannard2013; Rosendo et al., Reference Rosendo, Celliers and Mechisso2018; Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Hobday, Allison, Armitage, Brooks, Bundy, Cvitanovic, Dickey-Collas, D. M. Grilli, Gomez, Jarre, Kaikkonen, Kelly, López, Muhl, Pennino, Tam and van Putten2021). This will require innovation within and across disciplines, together with a willingness of all actors to engage in research that pushes disciplinary and scientific boundaries. Beyond diversifying and combining disciplinary research, we further recognise the need for the uptake of research that addresses these complex, real-world challenges by integrating the diversity of knowledge and involving those affected or taking action in the research process (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Williams, Nanz and Renn2022; Renn, Reference Renn2021).

Secondly, there is an emergence of an orientation towards the future in science and society. ‘Future’ is an operative word that evokes uncertainty about every aspect of human existence, from health to security and home, to well-being and comfort. A search of the Scopus database of publicationsFootnote 1 reveals an exponential growth of articles dealing with ‘coast’ and ‘future’ from 2000 (176) to 2022 (1225, see also Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Riechers, Celliers and Ferse2023). Coastal scholars recognise the significance of the concept of the ‘future’, and are actively integrating it into their research and scholarly work (Farbotko et al., Reference Farbotko, Boas, Dahm, Kitara, Lusama and Tanielu2023; Gaill et al., Reference Gaill, Rudolph, Lebleu, Allemand, Blasiak, Cheung, Claudet, Gerhardinger, Bris, Levin, Pörtner, Visbeck, Zivian, Bahurel, Bopp, Bowler, Chlous, Cury, Gascuel and d'Arvor2022; Harmáčková et al., Reference Harmáčková, Yoshida, Sitas, Mannetti, Martin, Kumar, Berbés-Blázquez, Collins, Eisenack, Guimaraes, Heras, Nelson, Niamir, Ravera, Ruiz-Mallén and O'Farrell2023; Obura et al., Reference Obura, DeClerck, Verburg, Gupta, Abrams, Bai, Bunn, Ebi, Gifford, Gordon, Jacobson, Lenton, Liverman, Mohamed, Prodani, Rocha, Rockström, Sakschewski, Stewart-Koster and Zimm2023; Pace et al., Reference Pace, Saritas and Deidun2023). The UN’s Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals, the Paris Agreement and many other global policy objectives refer to key targets to be achieved in the future, or loss and damage to be mitigated (e.g. by the middle or end of the century). The science we produce is increasingly used to understand the future world based on the current trajectories of change and the policy efforts to reduce crises (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Mackay, Novaglio, Fullbrook, Murunga, Sbrocchi, McDonald, McCormack, Alexander, Fudge, Goldsworthy, Boschetti, Dutton, Dutra, McGee, Rousseau, Spain, Stephenson, Vince and Haward2022; Tosca et al., Reference Tosca, Galvin, Gilbert, Walls, Tyler and Nastan2021; Wyborn et al., Reference Wyborn, Davila, Pereira, Lim, Alvarez, Henderson, Luers, Harms, Maze, Montana, Ryan, Sandbrook, Shaw and Woods2020). According to Knappe et al. (Reference Knappe, Holfelder, Löw Beer and Nanz2019), ‘future-making practices’ are social and political efforts that build relationships or allude to things yet to come. Understanding the dynamics between knowledge and power in future-making practices in marine science can reveal whether this field promotes or obstructs progress towards sustainability. See, for example Nightingale et al. (Reference Nightingale, Eriksen, Taylor, Forsyth, Pelling, Newsham, Boyd, Brown, Harvey, Jones, Kerr, Mehta, Naess, Ockwell, Scoones, Tanner and Whitfield2019), those who propose placing values, normative commitments, and experiential and plural ways of knowing from around the world at the centre of climate knowledge. Hobday et al. (Reference Hobday, Hartog, Manderson, Mills, Oliver, Pershing, Siedlecki and Browman2019) developed a set of ten principles for ethical forecasting, including a focus on co-creation and participation.

Thirdly, there is a need for actionable science and policy and receptive communities that demand tangible outcomes that are not imposed on, but co-created with, societal actors (Celliers et al., Reference Celliers, Mañez Costa, Rölfer, Aswani and Ferse2023a; Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Wyborn, Klenk, Ryan, Serban, Bennett, Brennan, Charli-Joseph, Fernández-Giménez, Galvin, Goldstein, Haller, Hill, Munera, Nel, Österblom, Reid, Riechers, Spierenburg and Rondeau2022; Weiand et al., Reference Weiand, Unger, Rochette, Müller and Neumann2021). This could be described as a ‘coupled dance between human decisions and coastal environmental change’ (Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Adams, Tissier, Murray and Splinter2023, p.3). It is known that decelerating and halting the transgression of key planetary tipping points serves the public good and requires multi-level, distributed, fair and proportional action by all (i.e. Common But Differentiated Responsibility) (Blankespoor et al., Reference Blankespoor, Dasgupta, Wheeler, Jeuken, Van Ginkel, Hill and Hirschfeld2023). Furthermore, the assumption of the validity and adequacy of scientific data and information in the absence of knowledge co-production by decision-makers, policy-makers, the private sector, and civil society is not tenable (Celliers et al., Reference Celliers, Costa, Williams and Rosendo2021; Miner et al., Reference Miner, Canavera, Gonet, Luis, Maddox, Mccarney, Bridge, Schimel and Rattlingleaf2023). The exploration of future approaches combined with transdisciplinary co-production is creating a surge of interest in breaking down the power dynamics afflicting academia, between science and society, within academia, and amongst ‘Western”’Cartesian and other knowledge systems. Transdisciplinarity is an approach that normalises collaborative processes involving academic and non-academic actors, aims to balance power dynamics in knowledge production, and results in solutions for societal challenges (see e.g. Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Williams, Nanz and Renn2022). Transdisciplinarity, as a product of science embedded in and informed by society, is an opportunity to explore collective human action towards novel solutions.

3. Towards a transformed future

In this paper, we offer three propositions to accelerate urgent actions, foster innovation in coastal research, and focus on emerging trends and foundational changes (Figure 1).

Proposition 1: Scientists urgently need to reflect on the performativity of their research and perceptions of neutrality in anticipating the future of coasts.

Figure 1. Three propositions (solid blue circles) of the new role of science to contribute to a pathway of transformation to a sustainable and human-positive environment where the observed negative trends (−R) in planetary crises (solid orange circles) are reversed by at least equally positive rates of change (++R) in societal action to avoid an existential crisis for humanity.

Science actively shapes the world through its theories, analytical practices and discourses. This perspective comes from fields such as Science and Technology Studies and Political Ecology, where scholars argue that science does not simply discover facts about nature, but constructs knowledge through interactions and institutional processes. Reflexivity in science – science actors who are conscious of their position – recognises the real-world consequences and societal uses of the outputs of the science process. This concept, known as performativity, promotes critical reflection on how knowledge is created, by whom, and for whose benefit it is ultimately applied (Bruns, Reference Bruns, Gottschlich, Hackfort, Schmitt and von Winterfeld2022).

Some key questions triggered by the performativity of science are: How does scientific theory, underpinned by data and information about climate change, pollution or biodiversity loss, shape the actions of coastal communities (Bowden et al., Reference Bowden, Gond, Nyberg and Wright2021)? Through which actions and by which actors can the language of coastal research function as a form of social action and effect change? Furthermore, research practices, paradigms, methodologies, scientific papers, databases, models, and scenarios can be described as future objects. These future objects have components of knowledge and material, playing a significant role in the socio-material politics of anticipation (Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2017; Esguerra, Reference Esguerra2019). As Esguerra (Reference Esguerra2019) argued, future objects are governed by varying objectives, offering options for political participation at different levels and in diverse ways. Creating futures involves material actions and epistemic descriptions, and understanding their interplay is crucial. Incorporating anticipation and foresight in transdisciplinary research may enable the realisation or advancement of creative and sustainable futures (Baumann et al., Reference Baumann, Riechers, Celliers and Ferse2023), moving away from path dependencies created by continuing consumption and the hegemony of economic growth that further entrench the human dilemma (Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2017).

Thus, anticipation, or the growing political demand for sustainability pathways, requires rethinking beyond expert-driven neutral input. Beck and Mahony (Reference Beck and Mahony2017) suggest that ‘…forecasters themselves should be asked to anticipate the political impacts of their forecasts’ (p. 312). The implication is that experts should be aware of, and willing to engage with the many ways in which the best-intended data and information may have distinctly different meanings for societal users. Concomitantly, coastal and marine research requires innovative and brave approaches to conceptualising and studying the connections between society, nature, and the future (heuristics, concepts, methods). Studying the future of coastal areas requires making assumptions and framings that contribute to and construct varying perspectives of coasts as human-nature systems of the future.

However, there is often a lack of transparency and reflection on current approaches to scientific research and how they contribute to shaping the future. A more reflexive approach will make different epistemological and ontological assumptions more transparent. Some of the key aspects include ideas about economic growth and how growth paradigms are often taken for granted in the scenario-building process (Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2017). The science of future coasts and its many different disciplines needs to reflect on the choice, nature and use of methods and approaches: The scientific community must mirror their assumptions in an accessible and transparent way, which is time-consuming and requires novel formats and reflexive spaces in research practices. The predominant Western understanding and design of the science process and its social and political context may not lend itself to achieving more sustainable coasts at the global scale. Other forms of knowledge and knowledge cultures must be recognised – this is epistemological inclusion. Concomitantly, other life-world experiences and lifestyles, i.e. the coexistence of multiple ways of conceptualising and explaining the world or specific phenomena, must be included in future coastal science – this is ontological pluralism (Nightingale et al., Reference Nightingale, Eriksen, Taylor, Forsyth, Pelling, Newsham, Boyd, Brown, Harvey, Jones, Kerr, Mehta, Naess, Ockwell, Scoones, Tanner and Whitfield2019).

We support the call for radical structural change and societal transformation and urge the inclusion of the scientific system in this transformation as part of society. It offers innovative perspectives for conceptualising, studying and designing societal futures as part of nurturing nature. Yet, the current scientific system, including its funding structures, often impedes the reality of such research approaches (Fam et al., Reference Fam, Clarke, Freeth, Derwort, Klaniecki, Kater‐Wettstädt, Juarez‐Bourke, Hilser, Peukert, Meyer and Horcea‐Milcu2019). For example, scientific reflexivity is frequently met with reluctance by funders, while time or resource constraints marginalise structured reflection processes as part of the full research process. Reflexivity and learning are particularly challenging in inter- and transdisciplinary settings where more time and resources are required to achieve cognitive, normative, and relational learning as prerequisites for shifting values, enhanced trust and cooperation (Baird et al., Reference Baird, Plummer, Haug and Huitema2014). This causes imbalance, resulting in unsatisfactory cooperation and outcomes, often leading to misunderstandings regarding communication, acceptance, and the transformative roles of science.

Furthermore, scholarship on the critical role of social sciences in climate change adaptation is rapidly evolving. Climate change adaptation constitutes a political concept and discourse of tangible material consequences, including infrastructure development (Colloff et al., Reference Colloff, Martín-López, Lavorel, Locatelli, Gorddard, Longaretti, Walters, van Kerkhoff, Wyborn, Coreau, Wise, Dunlop, Degeorges, Grantham, Overton, Williams, Doherty, Capon, Sanderson and Murphy2017; Eisenack & Paschen, Reference Eisenack and Paschen2022) and change to ecosystems (e.g. blue carbon) and associated human benefits (Fink & Ratter, Reference Fink and Ratter2024). Nevertheless, most discussions on adaptation are frequently criticised for being apolitically framed, despite their noticeable political impacts. For example, many international cooperation programmes for adaptation are steeped in technical and managerial terms (Cameron, Reference Cameron2012; Keele, Reference Keele2019) that lack cultural, social, and political diversity and ontological pluralism (Nightingale et al., Reference Nightingale, Eriksen, Taylor, Forsyth, Pelling, Newsham, Boyd, Brown, Harvey, Jones, Kerr, Mehta, Naess, Ockwell, Scoones, Tanner and Whitfield2019). Moreover, social inequalities that limit adaptation or adaptation options are often disregarded or even reinforced (Klepp & Chavez-Rodriguez, Reference Klepp and Chavez-Rodriguez2018). Such apolitical approaches in adaptation projects, e.g. in the context of international cooperation, might be understood as future un-making approaches. Futures that are envisioned as undesirable, shall be prevented by adaptation measures.

Finally, critical research on global change argues that transformation towards sustainability is more urgent than ever. However, a large part of research still relies on underlying framings that support the status quo (Castree, Reference Castree2022; Nightingale et al., Reference Nightingale, Gonda and Eriksen2021; Wiegleb & Bruns, Reference Wiegleb and Bruns2025). These techno-scientific frameworks dominate eco-modernist discourses, exemplified by the term ‘blue economy’ (see Proposition 2). As such, they strongly influence current policies and politics of adaptation and sustainability, while critical and diverse social science research is not equally considered.

Proposition 2: Scientists must think and act equitably in global partnerships

Research agendas, as well as future development plans and purported solution spaces, are still predominantly shaped in the Global North, even if they address and affect the lives of people in the Global South (Henrich et al., Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010; Miller et al., Reference Miller, White and Christie2023; Spalding et al., Reference Spalding, Grorud-Colvert, Allison, Amon, Collin, de Vos, Friedlander, Johnson, Mayorga, Paris, Scott, Suman, Estradivari, Giron-Nava, Gurney, Harris, Hicks, Mangubhai, Micheli and Thurber2023; Wiegleb & Bruns, Reference Wiegleb and Bruns2018). Using contemporary narratives such as ‘blue economy’ or ‘blue carbon’ often reflects the political agendas of the Global North and industries (Schutter et al., Reference Schutter, Hicks, Phelps and Waterton2021), and other political agendas. We thus see a need to accommodate and integrate multiple, pluralistic visions for a common future beyond the normative guidance of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It is also necessary to have a much more significant role of Global South actors and perspectives in research collaborations, while also considering the disparities in resources (Armenteras, Reference Armenteras2021; Costello & Zumla, Reference Costello and Zumla2000). A critical evaluation of who is responsible for defining and setting agendas is part of this conversation. Scientists and research organisations, particularly in the Global North, have a greater responsibility to contribute to research ethics, science diplomacy, and communication (Lahl et al., Reference Lahl, Ferse, Bleischwitz, Ittekkot and Baweja2023; Partelow et al., Reference Partelow, Hornidge, Senff, Stabler and Schluter2020a; Schroeder et al., Reference Schroeder, Chatfield, Singh, Chennells and Herissone-Kelly2019). We see four interrelated aspects to consider for coastal research in global partnerships: (i) the role of science in society; (ii) identification and definition of topics; (iii) modes of research and collaboration; and (iv) employment and funding structure.

Perspectives vary regarding the role of science in society. While basic research is the gold standard, applied research is often neglected. This tension is particularly relevant in a North–South perspective: We see a tendency that wealthy countries in the Global North value basic and curiosity-driven research more highly, holding academic freedom in high regard. In contrast, the reality in many countries in the Global South is different. For example, it is often expected that public servants and researchers serve society and applied research is the norm (e.g. Siregar, Reference Siregar, Kraemer-Mbula, Tijssen, Wallace and McClean2019). National differences in scientific knowledge production create cultural and political path dependencies within academic systems (Castro Torres & Alburez-Gutierrez, Reference Castro Torres and Alburez-Gutierrez2022; Partelow et al., Reference Partelow, Schlüter, Armitage, Bavinck, Carlisle, Gruby, Hornidge, Tissier, Pittman, Song, Sousa, Văidianu and Van Assche2020b). As such, North–South scientific collaboration should consider and respect the significance of local applications of science as a tool for development, and the extent of its role in collaborative research settings.