1. Introduction

1.1. Stochastic gradient descent

Consider the following learning problem: For

![]() $d, p \ge 1$

, let

$d, p \ge 1$

, let

![]() $\mathcal{H}$

and

$\mathcal{H}$

and

![]() $\mathcal{Z}$

be subsets of

$\mathcal{Z}$

be subsets of

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^{d}$

and

${\mathbb{R}}^{d}$

and

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^{p}$

, respectively. We consider

${\mathbb{R}}^{p}$

, respectively. We consider

![]() $\mathcal{H}$

to be a set of parameters and

$\mathcal{H}$

to be a set of parameters and

![]() $\mathcal{Z}$

the domain of the observable data. Let

$\mathcal{Z}$

the domain of the observable data. Let

![]() $\ell \colon \mathcal{H} \times \mathcal{Z} \to [0, \infty)$

be a measurable function, called the loss function. The aim is to minimize the risk function

$\ell \colon \mathcal{H} \times \mathcal{Z} \to [0, \infty)$

be a measurable function, called the loss function. The aim is to minimize the risk function

![]() $L_\mathcal{D}(x)\,:\!=\, \mathbb{E} \ell(x,Z)$

, where Z is a random variable on

$L_\mathcal{D}(x)\,:\!=\, \mathbb{E} \ell(x,Z)$

, where Z is a random variable on

![]() $\mathcal{Z}$

that is assumed to generate the data, and the law

$\mathcal{Z}$

that is assumed to generate the data, and the law

![]() $\mathcal{D}$

of Z is unknown.

$\mathcal{D}$

of Z is unknown.

Upon observing a sample

![]() $S=(z_1, \ldots, z_m)$

of realizations of Z, we can define the empirical risk function by

$S=(z_1, \ldots, z_m)$

of realizations of Z, we can define the empirical risk function by

If

![]() $\mathcal{H}$

is convex and

$\mathcal{H}$

is convex and

![]() $\ell$

is differentiable on

$\ell$

is differentiable on

![]() $\mathcal{H}$

, we can employ the gradient descent algorithm in order to minimize

$\mathcal{H}$

, we can employ the gradient descent algorithm in order to minimize

![]() $L_S$

: Starting with

$L_S$

: Starting with

![]() $x_0 \in \mathcal{H}$

, we recursively define, for

$x_0 \in \mathcal{H}$

, we recursively define, for

![]() $n \in \mathbb{N}$

,

$n \in \mathbb{N}$

,

\begin{align*}x_n = x_{n-1} - \eta_n\nabla L_S(x_{n-1}) = x_{n-1} - \eta_n\Bigg(\frac1m\sum_{i=1}^m\nabla\ell(x_{n-1},z_i)\Bigg)\end{align*}

\begin{align*}x_n = x_{n-1} - \eta_n\nabla L_S(x_{n-1}) = x_{n-1} - \eta_n\Bigg(\frac1m\sum_{i=1}^m\nabla\ell(x_{n-1},z_i)\Bigg)\end{align*}

with parameter

![]() $\eta_n>0$

, called the step size or learning rate, which may vary with time. The parameter

$\eta_n>0$

, called the step size or learning rate, which may vary with time. The parameter

![]() $\eta_n$

has to be chosen sufficiently small that the first-order approximation of the function about

$\eta_n$

has to be chosen sufficiently small that the first-order approximation of the function about

![]() $x_{n-1}$

by its gradient is good enough; see, e.g., [Reference Murphy17, Section 8.4.3] for a discussion.

$x_{n-1}$

by its gradient is good enough; see, e.g., [Reference Murphy17, Section 8.4.3] for a discussion.

In stochastic gradient descent (see, e.g., [Reference Shalev-Shwartz and Ben-David18, Chapter 14]), the idea is to use at each step only a random subsample

![]() $(z_{i,n})_{1 \le i \le b}$

of size b of the observations to calculate the gradient:

$(z_{i,n})_{1 \le i \le b}$

of size b of the observations to calculate the gradient:

\begin{equation} x_n = x_{n-1} - \frac{\eta_n}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b \nabla \ell(x_{n-1},z_{i,n}) \,=\!:\, x_{n-1} - g_n.\end{equation}

\begin{equation} x_n = x_{n-1} - \frac{\eta_n}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b \nabla \ell(x_{n-1},z_{i,n}) \,=\!:\, x_{n-1} - g_n.\end{equation}

By choosing the subsample at random, the gradient term

![]() $g_n$

becomes a random variable. If, in each step, a new sample is drawn independently of the previous samples, then the successive gradient terms

$g_n$

becomes a random variable. If, in each step, a new sample is drawn independently of the previous samples, then the successive gradient terms

![]() $(g_n)_{n \ge 1}$

are independent as well. However, the

$(g_n)_{n \ge 1}$

are independent as well. However, the

![]() $(g_n)_{n \ge 1}$

are not identically distributed, since the gradients are evaluated at different points

$(g_n)_{n \ge 1}$

are not identically distributed, since the gradients are evaluated at different points

![]() $x_{n-1}$

in each step.

$x_{n-1}$

in each step.

To analyze the algorithm, it is of prime interest to study the random distance between

![]() $x_n$

and local minima of

$x_n$

and local minima of

![]() $L_S$

. To show how this relates to stochastic recursions, we focus now on the particular setting (more general settings will be considered in Section 3.4) of a quadratic loss function with constant step size, as considered in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12]: The parameter set is

$L_S$

. To show how this relates to stochastic recursions, we focus now on the particular setting (more general settings will be considered in Section 3.4) of a quadratic loss function with constant step size, as considered in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12]: The parameter set is

![]() $\mathcal{H}={\mathbb{R}}^d$

, the observed data

$\mathcal{H}={\mathbb{R}}^d$

, the observed data

![]() $z \in\mathcal{Z}={\mathbb{R}}^d \times {\mathbb{R}}$

, and with

$z \in\mathcal{Z}={\mathbb{R}}^d \times {\mathbb{R}}$

, and with

![]() $z=(a,y)$

the loss function is given by

$z=(a,y)$

the loss function is given by

This corresponds to the setting of linear regression where

![]() $y \in {\mathbb{R}}$

would be the target variable and a the vector of explanatory variables;

$y \in {\mathbb{R}}$

would be the target variable and a the vector of explanatory variables;

![]() $L_S(x)$

is then equal to the mean squared error.

$L_S(x)$

is then equal to the mean squared error.

In this setting, the function

![]() $L_S(x)$

has a unique global minimum

$L_S(x)$

has a unique global minimum

![]() $x_*$

, and we can expand the gradient of

$x_*$

, and we can expand the gradient of

![]() $\ell$

around

$\ell$

around

![]() $x_*$

:

$x_*$

:

![]() $\nabla\ell(x,a,y) = a(a^\top x-y) = -ya + (aa^\top)x_* + (aa^\top)(x-x_*)$

. Note that a and x are d-dimensional column vectors,

$\nabla\ell(x,a,y) = a(a^\top x-y) = -ya + (aa^\top)x_* + (aa^\top)(x-x_*)$

. Note that a and x are d-dimensional column vectors,

![]() $a^\top$

is a row vector,

$a^\top$

is a row vector,

![]() $aa^\top$

is the

$aa^\top$

is the

![]() $(d \times d)$

rank-one projection matrix onto a. Using this in (1.1), we obtain, for the distance

$(d \times d)$

rank-one projection matrix onto a. Using this in (1.1), we obtain, for the distance

![]() $x_n-x_*$

,

$x_n-x_*$

,

\begin{equation*} x_n - x_* = x_{n-1} - x_* - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b\big(a_ia_i^\top\big)(x_{n-1}-x_*) + \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b\big(y_ia_i - \big(a_ia_i^\top\big)x_*\big).\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} x_n - x_* = x_{n-1} - x_* - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b\big(a_ia_i^\top\big)(x_{n-1}-x_*) + \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b\big(y_ia_i - \big(a_ia_i^\top\big)x_*\big).\end{equation*}

Let I be the

![]() $d\times d$

identity matrix. Writing

$d\times d$

identity matrix. Writing

\begin{equation} X_n \,:\!=\, x_n-x_*, \qquad A_n \,:\!=\, \Bigg(\mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b} \sum_{i=1}^b a_i a_i^\top\Bigg), \qquad B_n \,:\!=\, \frac{\eta}{b} \sum_{i=1}^b\big(y_ia_i - \big(a_ia_i^\top\big)x_*\big),\end{equation}

\begin{equation} X_n \,:\!=\, x_n-x_*, \qquad A_n \,:\!=\, \Bigg(\mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b} \sum_{i=1}^b a_i a_i^\top\Bigg), \qquad B_n \,:\!=\, \frac{\eta}{b} \sum_{i=1}^b\big(y_ia_i - \big(a_ia_i^\top\big)x_*\big),\end{equation}

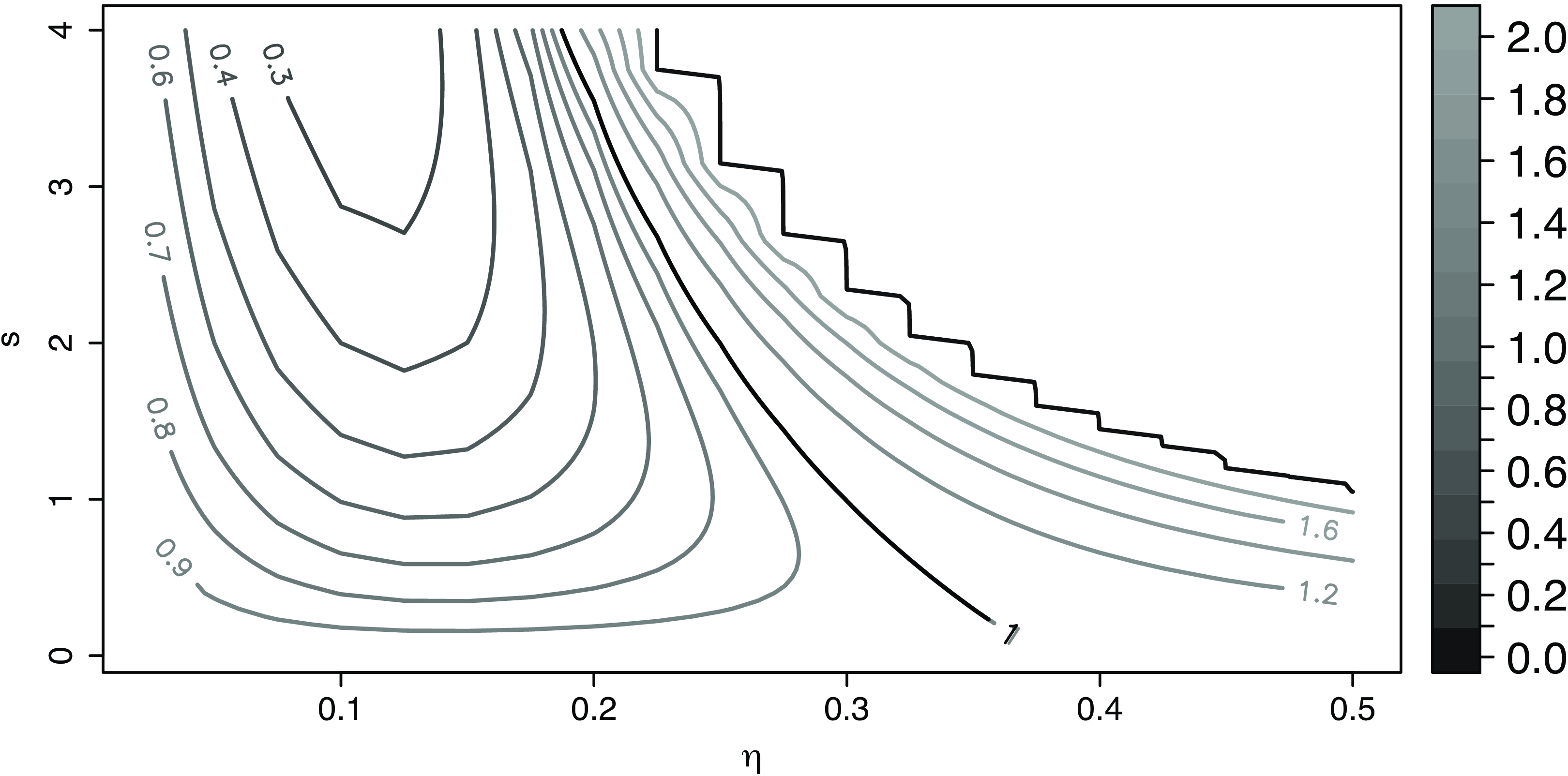

we see that

![]() $X_n$

satisfies an affine stochastic recursion

$X_n$

satisfies an affine stochastic recursion

with

![]() $(A_n,B_n)$

now being an independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) sequence of random matrices and vectors.

$(A_n,B_n)$

now being an independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) sequence of random matrices and vectors.

1.2. Summary of results

It is known ([Reference Alsmeyer and Mentemeier1, Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10, Reference Kesten15]; see also [Reference Buraczewski, Damek and Mikosch5]) that under mild assumptions, stationary solutions to such recursive equations will exhibit heavy tails even if the law of

![]() $a_i$

has all the moments. This means that there is a substantial probability that iterations of the stochastic gradient descent go far away from the minimum, due to the randomness.

$a_i$

has all the moments. This means that there is a substantial probability that iterations of the stochastic gradient descent go far away from the minimum, due to the randomness.

Here, a random variable X is a stationary solution to (1.3) if X has the same law as

![]() $A_1X+B_1$

, and X is independent of

$A_1X+B_1$

, and X is independent of

![]() $(A_1,B_1)$

. The main condition for the existence (and uniqueness) of such a stationary solution is that the top Lyapunov exponent is negative; see below for details. We say that (the law of) X has Pareto tails with tail index

$(A_1,B_1)$

. The main condition for the existence (and uniqueness) of such a stationary solution is that the top Lyapunov exponent is negative; see below for details. We say that (the law of) X has Pareto tails with tail index

![]() $\alpha$

if there is

$\alpha$

if there is

![]() $c>0$

such that

$c>0$

such that

![]() $\lim_{t\to \infty}{t^\alpha} {\mathbb{P}}(|X|>t)=c$

. This is a particular instance of heavy-tail behavior. Intriguing questions are: How is the tail behavior affected by the subsample size b, the step size

$\lim_{t\to \infty}{t^\alpha} {\mathbb{P}}(|X|>t)=c$

. This is a particular instance of heavy-tail behavior. Intriguing questions are: How is the tail behavior affected by the subsample size b, the step size

![]() $\eta$

, or the distribution generating

$\eta$

, or the distribution generating

![]() $(a_i,y_i)$

? What can be said about the law or the moments of finite iterations

$(a_i,y_i)$

? What can be said about the law or the moments of finite iterations

![]() $X_n$

?

$X_n$

?

In [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12], these questions have been studied under a density assumption on the law of

![]() $a_i$

, and relevant results have been proved when

$a_i$

, and relevant results have been proved when

![]() $a_i\sim \mathcal{N}(0,\sigma ^2I_d)$

is standard normal. However, the proof of the heavy-tail behavior of X in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12] is based on a theorem of Alsmeyer and Mentemeier [Reference Alsmeyer and Mentemeier1] that cannot be used since the matrix A does not have density on

$a_i\sim \mathcal{N}(0,\sigma ^2I_d)$

is standard normal. However, the proof of the heavy-tail behavior of X in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12] is based on a theorem of Alsmeyer and Mentemeier [Reference Alsmeyer and Mentemeier1] that cannot be used since the matrix A does not have density on

![]() ${\mathbb{R}} ^{d^2}$

. Namely, in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12, Theorem 2], M does not have a Lebesgue density on

${\mathbb{R}} ^{d^2}$

. Namely, in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12, Theorem 2], M does not have a Lebesgue density on

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^{d^2}$

that is positive in a neighborhood of the identity matrix I since the law of M is concentrated on symmetric matrices, which constitute a

${\mathbb{R}}^{d^2}$

that is positive in a neighborhood of the identity matrix I since the law of M is concentrated on symmetric matrices, which constitute a

![]() $d(d+1)/2$

-dimensional subspace of

$d(d+1)/2$

-dimensional subspace of

![]() $d^2$

-Lebesgue measure 0. In fact, of all the existing results [Reference Alsmeyer and Mentemeier1, Reference Buraczewski, Damek, Guivarc’h, Hulanicki and Urban4, Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10, Reference Kesten15] implying the heavy-tail behavior of X, only the one in [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10] is applicable here. We need to employ the theory of irreducible-proximal (i-p) matrices from [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10], which is the right framework for the problem and at the same time allows us to go beyond the setting of [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12]: we neither require a Gaussian density nor the particular form of A as in (1.2). Further, it will allow us to include the case of cyclic varying stepsizes, see Section 3.4. Under conditions of i-p, the tail behavior of X is described in Theorem 3.1, which we quote from [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10].

$d^2$

-Lebesgue measure 0. In fact, of all the existing results [Reference Alsmeyer and Mentemeier1, Reference Buraczewski, Damek, Guivarc’h, Hulanicki and Urban4, Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10, Reference Kesten15] implying the heavy-tail behavior of X, only the one in [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10] is applicable here. We need to employ the theory of irreducible-proximal (i-p) matrices from [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10], which is the right framework for the problem and at the same time allows us to go beyond the setting of [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12]: we neither require a Gaussian density nor the particular form of A as in (1.2). Further, it will allow us to include the case of cyclic varying stepsizes, see Section 3.4. Under conditions of i-p, the tail behavior of X is described in Theorem 3.1, which we quote from [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10].

In particular, we may consider settings where

![]() $A_n = \mathrm{I} - ({\eta}/{b}) \sum_{i=1}^b H_{i,n}$

for i.i.d. random symmetric

$A_n = \mathrm{I} - ({\eta}/{b}) \sum_{i=1}^b H_{i,n}$

for i.i.d. random symmetric

![]() $d \times d$

matrices

$d \times d$

matrices

![]() $H_{i,n}$

. On one hand, this corresponds to a loss function

$H_{i,n}$

. On one hand, this corresponds to a loss function

![]() $\ell(x,H)=x^{\top} H x$

that is a random quadratic form; on the other hand, this is motivated by the observation (cf. [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12, Reference Hodgkinson and Mahoney14]) that for a twice-differentiable loss function

$\ell(x,H)=x^{\top} H x$

that is a random quadratic form; on the other hand, this is motivated by the observation (cf. [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12, Reference Hodgkinson and Mahoney14]) that for a twice-differentiable loss function

![]() $\ell$

, we may perform a Taylor expansion of the gradient about

$\ell$

, we may perform a Taylor expansion of the gradient about

![]() $x_*$

to obtain

$x_*$

to obtain

\begin{equation*} x_n - x_* \approx \Bigg(\mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b H_\ell(x_*,z_{i,n})\Bigg)(x_{n-1} - x_*) - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b\nabla\ell(x_*,z_{i,n}), \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} x_n - x_* \approx \Bigg(\mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b H_\ell(x_*,z_{i,n})\Bigg)(x_{n-1} - x_*) - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b\nabla\ell(x_*,z_{i,n}), \end{equation*}

where

![]() $H_\ell$

denotes the Hessian of

$H_\ell$

denotes the Hessian of

![]() $\ell$

. However, we have to keep in mind that such an approximation is in general valid only for

$\ell$

. However, we have to keep in mind that such an approximation is in general valid only for

![]() $x_n$

close to

$x_n$

close to

![]() $x_*$

.

$x_*$

.

In the setting of i-p, we are able to prove that

![]() $\mathbb{E} |X_n|^{\alpha}$

grows linearly with n, see Theorem 3.2, which considerably improves the result of [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12, Proposition 10] (which gives only a polynomial bound).

$\mathbb{E} |X_n|^{\alpha}$

grows linearly with n, see Theorem 3.2, which considerably improves the result of [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12, Proposition 10] (which gives only a polynomial bound).

The main issue is how the tail index

![]() $\alpha$

depends on

$\alpha$

depends on

![]() $\eta$

and b. For that, we need a tractable expression for the value of

$\eta$

and b. For that, we need a tractable expression for the value of

![]() $\alpha$

as well as for the top Lyapunov exponent. It turns out that invariance of the law of A under rotations does the job and this, besides i-p, is the second vital ingredient for the right framework. This includes the Gaussian case studied in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12], and particular calculations suitable for the Gaussian case are no longer indispensable. We derive a simple formula for the Lyapunov exponent and an appropriate moment-generating function in Lemma 3.4, which allows us to completely describe the behavior of

$\alpha$

as well as for the top Lyapunov exponent. It turns out that invariance of the law of A under rotations does the job and this, besides i-p, is the second vital ingredient for the right framework. This includes the Gaussian case studied in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12], and particular calculations suitable for the Gaussian case are no longer indispensable. We derive a simple formula for the Lyapunov exponent and an appropriate moment-generating function in Lemma 3.4, which allows us to completely describe the behavior of

![]() $\alpha$

as a function of

$\alpha$

as a function of

![]() $\eta$

and b, see Theorem 3.5.

$\eta$

and b, see Theorem 3.5.

Finally, we turn to the question of the finiteness of

![]() $\mathbb{E} \det(A)^{-\varepsilon}$

for some

$\mathbb{E} \det(A)^{-\varepsilon}$

for some

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

, which is required as an assumption Theorem 3.1. Unless

$\varepsilon>0$

, which is required as an assumption Theorem 3.1. Unless

![]() $\det A$

is bounded away from zero, this cannot be claimed in general. Indeed, there are gaps in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12]: In [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu13, Lemma 20], the inequality D.18,

$\det A$

is bounded away from zero, this cannot be claimed in general. Indeed, there are gaps in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12]: In [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu13, Lemma 20], the inequality D.18,

![]() $\log({1}/({1-x}))\le 2x$

, is wrong for x close to 1. We show that a simple sufficient condition for the integrability of

$\log({1}/({1-x}))\le 2x$

, is wrong for x close to 1. We show that a simple sufficient condition for the integrability of

![]() $\det(A)^{-\varepsilon}$

is the existence of a density of the law of A with some weak decay properties (see Section 7), which is also natural from the point of view of applications. The proof is given in Section 7. The problem is interesting in itself and, as far as we know, has not previously been approached in the context of multivariate stochastic recursions. Finally, the existence of a density considerably simplifies the assumptions in Lemma 3.4 and Theorem 3.5.

$\det(A)^{-\varepsilon}$

is the existence of a density of the law of A with some weak decay properties (see Section 7), which is also natural from the point of view of applications. The proof is given in Section 7. The problem is interesting in itself and, as far as we know, has not previously been approached in the context of multivariate stochastic recursions. Finally, the existence of a density considerably simplifies the assumptions in Lemma 3.4 and Theorem 3.5.

We introduce all relevant notation, descriptions of the models, and assumptions in Section 2, in order to state our main results in Section 3, accompanied by a list of examples to which our findings apply. The proofs are deferred to the subsequent sections.

2. Assumptions, notations, and preliminaries

We assume that all random variables are defined on a generic probability space

![]() $(\Omega, \mathcal F, {\mathbb{P}})$

. Let

$(\Omega, \mathcal F, {\mathbb{P}})$

. Let

![]() $d \ge 1$

. Equip

$d \ge 1$

. Equip

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^d$

with the Euclidean norm

${\mathbb{R}}^d$

with the Euclidean norm

![]() $|\cdot |$

, and let

$|\cdot |$

, and let

![]() $\|\cdot \|$

be the corresponding operator norm for matrices. In addition, for a

$\|\cdot \|$

be the corresponding operator norm for matrices. In addition, for a

![]() $d \times d$

matrix g,

$d \times d$

matrix g,

![]() $\|g \|_{\mathrm{F}}\,:\!=\, \big(\sum_{1\le i,j\le d}g_{ij}^2\big)^{1/2}$

denotes the Frobenius norm. We write

$\|g \|_{\mathrm{F}}\,:\!=\, \big(\sum_{1\le i,j\le d}g_{ij}^2\big)^{1/2}$

denotes the Frobenius norm. We write

![]() ${\mathrm{Sym}(d,\mathbb{R})}$

for the set of symmetric

${\mathrm{Sym}(d,\mathbb{R})}$

for the set of symmetric

![]() $d \times d$

matrices,

$d \times d$

matrices,

![]() $\mathrm{GL}(d,\mathbb{R})$

for the group of invertible

$\mathrm{GL}(d,\mathbb{R})$

for the group of invertible

![]() $d \times d$

matrices over

$d \times d$

matrices over

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}$

, and O(d) for its subgroup of orthogonal matrices. The identity matrix is denoted by I. Write

${\mathbb{R}}$

, and O(d) for its subgroup of orthogonal matrices. The identity matrix is denoted by I. Write

![]() $S\,:\!=\,S^{d-1}$

for the unit sphere in

$S\,:\!=\,S^{d-1}$

for the unit sphere in

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^d$

with respect to

${\mathbb{R}}^d$

with respect to

![]() $|\cdot |$

. For

$|\cdot |$

. For

![]() $x \in S$

and

$x \in S$

and

![]() $g \in \mathrm{GL}(d,\mathbb{R})$

, define the action of g on x by

$g \in \mathrm{GL}(d,\mathbb{R})$

, define the action of g on x by

We fix an orthonormal basis

![]() $e_1, \ldots, e_d$

of

$e_1, \ldots, e_d$

of

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^d$

. We write

${\mathbb{R}}^d$

. We write

![]() $\mathcal{C}(S)$

for the set of continuous functions on S, equipped with the norm

$\mathcal{C}(S)$

for the set of continuous functions on S, equipped with the norm

![]() $\|\ f \|=\max \{|\ f(x)| \colon x \in S\}$

. The uniform measure

$\|\ f \|=\max \{|\ f(x)| \colon x \in S\}$

. The uniform measure

![]() $\sigma $

on S is defined by

$\sigma $

on S is defined by

where

![]() $\mathrm{d}o$

is the Haar measure on O(d) normalized to have mass 1. For

$\mathrm{d}o$

is the Haar measure on O(d) normalized to have mass 1. For

![]() $g \in \mathrm{GL}(d,\mathbb{R})$

we introduce the quantity

$g \in \mathrm{GL}(d,\mathbb{R})$

we introduce the quantity

For an interval

![]() $I \subset {\mathbb{R}}$

, the set of continuously differentiable functions on I is denoted

$I \subset {\mathbb{R}}$

, the set of continuously differentiable functions on I is denoted

![]() $\mathcal{C}^{1}(I)$

. For a random variable X, we denote by

$\mathcal{C}^{1}(I)$

. For a random variable X, we denote by

![]() ${\mathrm{supp}}(X)$

its support, i.e. the smallest closed subset E of its range with

${\mathrm{supp}}(X)$

its support, i.e. the smallest closed subset E of its range with

![]() ${\mathbb{P}}(X \in E)=1$

. We also use this notation for measures, where the support is the smallest closed set of full measure.

${\mathbb{P}}(X \in E)=1$

. We also use this notation for measures, where the support is the smallest closed set of full measure.

2.1. Stochastic recurrence equations

Given a sequence of i.i.d. copies

![]() $(A_n,B_n)_{n \ge 1}$

of a random pair

$(A_n,B_n)_{n \ge 1}$

of a random pair

![]() $(A,B) \in \mathrm{GL}(d,\mathbb{R}) \times \mathbb{R}^d$

, which are also independent of the random vector

$(A,B) \in \mathrm{GL}(d,\mathbb{R}) \times \mathbb{R}^d$

, which are also independent of the random vector

![]() $X_0 \in {\mathbb{R}}^d$

, we consider the sequence of random d-vectors

$X_0 \in {\mathbb{R}}^d$

, we consider the sequence of random d-vectors

![]() $(X_n)_{n \ge 1}$

defined by the affine stochastic recurrence equation

$(X_n)_{n \ge 1}$

defined by the affine stochastic recurrence equation

The study of equation (2.4) goes back to [Reference Kesten15]; see [Reference Buraczewski, Damek and Mikosch5] for a comprehensive account. Let

![]() $\Pi_n \,:\!=\, \prod_{i=1}^n A_i$

and write

$\Pi_n \,:\!=\, \prod_{i=1}^n A_i$

and write

![]() $\log^+ x\,:\!=\,\max\{0, \log x\}$

. Assume

$\log^+ x\,:\!=\,\max\{0, \log x\}$

. Assume

![]() $\mathbb{E} \log^+ \|A \| < \infty$

,

$\mathbb{E} \log^+ \|A \| < \infty$

,

![]() $\mathbb{E} \log^+ |B |<\infty$

, and that the top Lyapunov exponent

$\mathbb{E} \log^+ |B |<\infty$

, and that the top Lyapunov exponent

is negative. Then there exist a unique stationary distribution for the Markov chain defined by (2.4) and its law is given by the then almost surely convergent series

see [Reference Buraczewski, Damek and Mikosch5, Theorem 4.1.4]. Indeed, let us write

\begin{align*}R^{(1)} \,:\!=\, \lim_{n\to\infty}R_n^{(1)} \,:\!=\, \lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{j=1}^n A_2\cdots A_{j}B_{j+1},\end{align*}

\begin{align*}R^{(1)} \,:\!=\, \lim_{n\to\infty}R_n^{(1)} \,:\!=\, \lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{j=1}^n A_2\cdots A_{j}B_{j+1},\end{align*}

i.e. we shift all the indices by 1. Then

![]() $R_n \overset{\textrm{D}}{=} R_n^{(1)}$

,

$R_n \overset{\textrm{D}}{=} R_n^{(1)}$

,

![]() $R \overset{\textrm{D}}{=} R^{(1)}$

, and

$R \overset{\textrm{D}}{=} R^{(1)}$

, and

![]() $R_{n+1}=A_1 R_n^{(1)} +B_1$

. Hence, upon taking limits

$R_{n+1}=A_1 R_n^{(1)} +B_1$

. Hence, upon taking limits

![]() $n\to \infty$

, we see that R satisfies the distributional equation

$n\to \infty$

, we see that R satisfies the distributional equation

where A, B are independent of R. Let

![]() $I_k\,:\!=\, \{s \ge 0 \colon \mathbb{E}\|A \|^s < \infty\}$

and

$I_k\,:\!=\, \{s \ge 0 \colon \mathbb{E}\|A \|^s < \infty\}$

and

![]() $s_0\,:\!=\,\sup I_k$

. For any

$s_0\,:\!=\,\sup I_k$

. For any

![]() $s \in I_k$

, define the quantity

$s \in I_k$

, define the quantity

![]() $k(s) \,:\!=\, \lim_{n\to\infty}(\mathbb{E}{\|A_n\cdots A_1 \|^s})^{{1}/{n}}$

. Considering (2.5), a simple calculation gives that

$k(s) \,:\!=\, \lim_{n\to\infty}(\mathbb{E}{\|A_n\cdots A_1 \|^s})^{{1}/{n}}$

. Considering (2.5), a simple calculation gives that

![]() $k(s)<1$

together with

$k(s)<1$

together with

![]() $\mathbb{E} |B |^s<\infty$

implies

$\mathbb{E} |B |^s<\infty$

implies

![]() $\mathbb{E} |R |^s < \infty$

(see also [Reference Buraczewski, Damek and Mikosch5, Remark 4.4.3]).

$\mathbb{E} |R |^s < \infty$

(see also [Reference Buraczewski, Damek and Mikosch5, Remark 4.4.3]).

2.2. The setup:

$\boldsymbol{A} = \mathrm{\textbf{I}} - \xi \boldsymbol{H}$

for

$\boldsymbol{A} = \mathrm{\textbf{I}} - \xi \boldsymbol{H}$

for

$\boldsymbol{H} \in {\mathrm{\textbf{Sym}}(\boldsymbol{d},\mathbb{R})}$

$\boldsymbol{H} \in {\mathrm{\textbf{Sym}}(\boldsymbol{d},\mathbb{R})}$

Motivated by the application to stochastic gradient descent, we want to study matrices A of the form

![]() $A=\mathrm{I}-\xi H$

, where

$A=\mathrm{I}-\xi H$

, where

![]() $\xi >0$

and H is a random symmetric matrix. More specifically, we want to consider the following two models, both for

$\xi >0$

and H is a random symmetric matrix. More specifically, we want to consider the following two models, both for

![]() $b \in \mathbb{N}$

and

$b \in \mathbb{N}$

and

![]() $\eta>0$

. Firstly, a setup where B is arbitrary and A is composed from random symmetric matrices. Given a tuple

$\eta>0$

. Firstly, a setup where B is arbitrary and A is composed from random symmetric matrices. Given a tuple

![]() $(H_i)_{1\le i \le b}$

of i.i.d. random symmetric

$(H_i)_{1\le i \le b}$

of i.i.d. random symmetric

![]() $d \times d$

matrices, let

$d \times d$

matrices, let

\begin{align*} &\qquad\qquad A = \mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b H_i, \qquad \qquad \quad B \text{ a random vector in } {\mathbb{R}}^d. \end{align*}

\begin{align*} &\qquad\qquad A = \mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b H_i, \qquad \qquad \quad B \text{ a random vector in } {\mathbb{R}}^d. \end{align*}

Secondly, we consider a setup where A is composed from rank-one projections and B is a weighted sum of the corresponding eigenvectors:

\begin{align*} \\&\qquad\qquad A = \mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b a_i a_i^{\top}, \qquad\qquad B = \frac{\eta}{b} \sum_{i=1}^b a_i y_i,\end{align*}

\begin{align*} \\&\qquad\qquad A = \mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^b a_i a_i^{\top}, \qquad\qquad B = \frac{\eta}{b} \sum_{i=1}^b a_i y_i,\end{align*}

where

![]() $(a_i,y_i)$

are i.i.d. pairs in

$(a_i,y_i)$

are i.i.d. pairs in

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^d \times {\mathbb{R}}$

. Of course, model (Symm) contains model (Rank1) as a particular case. In what follows, we study a general model wherever possible, and only restrict to the particular case (that still covers [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12] completely) when this is necessary to obtain more precise results.

${\mathbb{R}}^d \times {\mathbb{R}}$

. Of course, model (Symm) contains model (Rank1) as a particular case. In what follows, we study a general model wherever possible, and only restrict to the particular case (that still covers [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12] completely) when this is necessary to obtain more precise results.

2.3. Geometric assumptions

Let

![]() $\mu_A$

be the law of A, and let

$\mu_A$

be the law of A, and let

![]() $G_A$

denote the closed semigroup generated by

$G_A$

denote the closed semigroup generated by

![]() ${\mathrm{supp}}(\mu_A)$

. It will be required that

${\mathrm{supp}}(\mu_A)$

. It will be required that

![]() $G_A \subset GL(d,{\mathbb{R}})$

, i.e. the matrix A is invertible with probability 1. This is satisfied, e.g., when

$G_A \subset GL(d,{\mathbb{R}})$

, i.e. the matrix A is invertible with probability 1. This is satisfied, e.g., when

![]() $\mu_A$

has a density with respect to Lebesgue measure on the set of symmetric matrices: the set of matrices with determinant 0 is of lower dimension.

$\mu_A$

has a density with respect to Lebesgue measure on the set of symmetric matrices: the set of matrices with determinant 0 is of lower dimension.

Here and below, a matrix is called proximal if it has a unique largest eigenvalue (with respect to the absolute value) and the corresponding eigenspace is one-dimensional. We say that

![]() $\mu_A$

satisfies an irreducible-proximal (i-p) condition if the following hold:

$\mu_A$

satisfies an irreducible-proximal (i-p) condition if the following hold:

-

(i) Irreducibility condition: There exists no finite union

$\mathcal{W}=\bigcup_{i=1}^n W_i$

of proper subspaces

$\mathcal{W}=\bigcup_{i=1}^n W_i$

of proper subspaces

$W_i \subsetneq \mathbb{R}^d$

that is

$W_i \subsetneq \mathbb{R}^d$

that is

$G_A$

-invariant.

$G_A$

-invariant. -

(ii) Proximality condition:

$G_A$

contains a proximal matrix.

$G_A$

contains a proximal matrix.

The irreducibility condition does not exclude a setting where

![]() $G_A$

leaves invariant a cone (e.g. if all matrices are nonnegative in addition), see [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10, Proposition 2.14]. Since this setting is not relevant to the applications that we have in mind, we will exclude it and consider the following assumption in all of the subsequent results:

$G_A$

leaves invariant a cone (e.g. if all matrices are nonnegative in addition), see [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10, Proposition 2.14]. Since this setting is not relevant to the applications that we have in mind, we will exclude it and consider the following assumption in all of the subsequent results:

For some results, we will require more specific assumptions. We say that

![]() $\mu_A$

is invariant under rotations if, for every

$\mu_A$

is invariant under rotations if, for every

![]() $o\in O(d)$

,

$o\in O(d)$

,

![]() $o Ho^\top$

has the same distribution law as H. We will make use of the following condition:

$o Ho^\top$

has the same distribution law as H. We will make use of the following condition:

Remark 2.1. If a random vector

![]() $a\in {\mathbb{R}} ^d$

has the property that, for every

$a\in {\mathbb{R}} ^d$

has the property that, for every

![]() $o \in O(d)$

, oa has the same law as a, then we call (the law of) a rotationally invariant as well. This is justified by the observation that then the law of

$o \in O(d)$

, oa has the same law as a, then we call (the law of) a rotationally invariant as well. This is justified by the observation that then the law of

![]() $H\,:\!=\,aa^\top$

is invariant under rotations.

$H\,:\!=\,aa^\top$

is invariant under rotations.

We will sometimes assume a Gaussian distribution for the

![]() $a_i$

:

$a_i$

:

Remark 2.2. The independence between

![]() $a_i$

and

$a_i$

and

![]() $y_i$

is not essential (and unrealistic for structured data). It suffices to assume, as in (Rank1) that

$y_i$

is not essential (and unrealistic for structured data). It suffices to assume, as in (Rank1) that

![]() $(a_i,y_i)$

are i.i.d. pairs for

$(a_i,y_i)$

are i.i.d. pairs for

![]() $1 \le i \le b$

, with the marginals being standard Gaussian, and then to assume in addition that

$1 \le i \le b$

, with the marginals being standard Gaussian, and then to assume in addition that

![]() ${\mathbb{P}}(Ax+B=x)<1$

holds for all

${\mathbb{P}}(Ax+B=x)<1$

holds for all

![]() $x \in {\mathbb{R}}^d$

. See the proof of Corollary 3.1 for further information.

$x \in {\mathbb{R}}^d$

. See the proof of Corollary 3.1 for further information.

Note that (Rank1Gauss) is assumed throughout in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12]; we will show that indeed all their results hold at least under (rotinv-p), and some already under (i-p-nc).

2.4. Density

As has already been mentioned, to study

![]() $\alpha$

as a function of

$\alpha$

as a function of

![]() $\eta$

and b, finiteness of

$\eta$

and b, finiteness of

![]() $\mathbb{E} \log N(A)$

or

$\mathbb{E} \log N(A)$

or

![]() $\mathbb{E} N(A)^\varepsilon$

for some

$\mathbb{E} N(A)^\varepsilon$

for some

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

is needed. This means, in particular, that we require finiteness of small (or logarithmic) moments of

$\varepsilon>0$

is needed. This means, in particular, that we require finiteness of small (or logarithmic) moments of

![]() $\|A^{-1} \|$

– see (2.3). Such a property is difficult to check in general (unless

$\|A^{-1} \|$

– see (2.3). Such a property is difficult to check in general (unless

![]() $\det A$

is bounded away from zero). However, it holds when the law of A has density, see Theorem 3.6 and Section 7. This is why we provide two sufficient conditions, formulated in terms of densities. The first one is for the model (Symm) where

$\det A$

is bounded away from zero). However, it holds when the law of A has density, see Theorem 3.6 and Section 7. This is why we provide two sufficient conditions, formulated in terms of densities. The first one is for the model (Symm) where

![]() $A=I-\xi H\,:\!=\,I-({\eta}/{b})\sum_{i=1}^b H_i$

:

$A=I-\xi H\,:\!=\,I-({\eta}/{b})\sum_{i=1}^b H_i$

:

The law of H has a density f with respect to Lebesgue measure on

![]() $\text{Sym(d},\mathbb{R})$

that satisfies

$\text{Sym(d},\mathbb{R})$

that satisfies

The second one is for the model (Rank1):

The law of

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_b\ \textrm{on}\ {\mathbb{R}}^{db}$

has a joint density f that satisfies

$a_1, \ldots, a_b\ \textrm{on}\ {\mathbb{R}}^{db}$

has a joint density f that satisfies

\begin{align} f(a_1, \ldots,a_b) \leq C\Bigg(1+\sum_i^b|a_i|^2\Bigg)^{-D} \quad \text{for some } D > \frac{db}{2}. \end{align}

\begin{align} f(a_1, \ldots,a_b) \leq C\Bigg(1+\sum_i^b|a_i|^2\Bigg)^{-D} \quad \text{for some } D > \frac{db}{2}. \end{align}

Under (Decay:Symm) or (Decay:Rank1), small moments of

![]() $\| A^{-1}\| $

are finite, which simplifies the assumptions in Lemma 3.4 and Theorem 3.5. The latter is essential from the point of view of applications.

$\| A^{-1}\| $

are finite, which simplifies the assumptions in Lemma 3.4 and Theorem 3.5. The latter is essential from the point of view of applications.

2.5. Preliminaries

For

![]() $s \in I_k$

, we define the operators

$s \in I_k$

, we define the operators

![]() $P^s$

and

$P^s$

and

![]() $P^s_*$

in

$P^s_*$

in

![]() $\mathcal{C}(S)$

as follows: For any

$\mathcal{C}(S)$

as follows: For any

![]() $f \in \mathcal{C}(S)$

,

$f \in \mathcal{C}(S)$

,

Properties of both operators will be important in our results.

Proposition 2.1. Assume that

![]() $\mu_A$

satisfies (i-p-nc) and let

$\mu_A$

satisfies (i-p-nc) and let

![]() $s \in I_k$

. Then the following hold. The spectral radii

$s \in I_k$

. Then the following hold. The spectral radii

![]() $\rho(P^s)$

and

$\rho(P^s)$

and

![]() $\rho(P^s_*)$

both equal k(s), and there is a unique probability measure

$\rho(P^s_*)$

both equal k(s), and there is a unique probability measure

![]() $\nu_{s}$

on S and a unique function

$\nu_{s}$

on S and a unique function

![]() $r_{s} \in \mathcal{C}({S})$

satisfying

$r_{s} \in \mathcal{C}({S})$

satisfying

![]() $\int r_{s}(x)\,\nu_{s}(\mathrm{d} x)=1$

,

$\int r_{s}(x)\,\nu_{s}(\mathrm{d} x)=1$

,

![]() $P^s r_{s} = k(s)r_{s}$

, and

$P^s r_{s} = k(s)r_{s}$

, and

![]() $P^s\nu_{s} = k(s)\nu_{s}$

. Further, the function

$P^s\nu_{s} = k(s)\nu_{s}$

. Further, the function

![]() $r_{s}$

is strictly positive.

$r_{s}$

is strictly positive.

Also, there is a unique probability measure

![]() ${\nu^*_{s}}$

satisfying

${\nu^*_{s}}$

satisfying

![]() $P^s_* {\nu^*_{s}} = k(s) {\nu^*_{s}}$

and neither

$P^s_* {\nu^*_{s}} = k(s) {\nu^*_{s}}$

and neither

![]() ${\mathrm{supp}}(\nu_{s})$

nor

${\mathrm{supp}}(\nu_{s})$

nor

![]() ${\mathrm{supp}}({\nu^*_{s}})$

are concentrated on any hyperplane. There is a

${\mathrm{supp}}({\nu^*_{s}})$

are concentrated on any hyperplane. There is a

![]() $c>0$

such that

$c>0$

such that

![]() $r_{s}(x) = c\int_S|\langle x,y \rangle |^s\,{\nu^*_{s}}(\mathrm{d} y)$

. The function

$r_{s}(x) = c\int_S|\langle x,y \rangle |^s\,{\nu^*_{s}}(\mathrm{d} y)$

. The function

![]() $s \mapsto k(s)$

is log-convex on

$s \mapsto k(s)$

is log-convex on

![]() $I_k$

, hence continuous on

$I_k$

, hence continuous on

![]() $\mathrm{int}(I_k)$

with left and right derivatives, and there is a constant

$\mathrm{int}(I_k)$

with left and right derivatives, and there is a constant

![]() $C_s$

such that, for all

$C_s$

such that, for all

![]() $n \in \mathbb{N}$

,

$n \in \mathbb{N}$

,

![]() $\mathbb{E} \|\Pi_n \|^s \le C_sk(s)^n$

.

$\mathbb{E} \|\Pi_n \|^s \le C_sk(s)^n$

.

Source. A combination of [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10, Theorem 2.6] and [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10, Theorem 2.16], where (i-p-nc) corresponds to Case I. The results concerning the supports as well as the bound for k(s) are proved in [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10, Lemma 2.8].

Proposition 2.2. ([Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10, Theorem 3.10].) Assume (i-p-nc), and that

![]() $\mathbb{E}(1+\|A\|^s)\log N(A)<\infty$

for some

$\mathbb{E}(1+\|A\|^s)\log N(A)<\infty$

for some

![]() $s>0$

. Then k is continuously differentiable on [

$s>0$

. Then k is continuously differentiable on [

![]() $0$

,s] with

$0$

,s] with

![]() $k'(0)=\gamma$

.

$k'(0)=\gamma$

.

Remark 2.3. Hence, a sufficient condition for

![]() $\gamma <0$

is

$\gamma <0$

is

![]() $\mathbb{E} \|A_1 \|<1$

(together with

$\mathbb{E} \|A_1 \|<1$

(together with

![]() $\mathbb{E} (1+\|A \|) \log N(A)<\infty$

): Observing that

$\mathbb{E} (1+\|A \|) \log N(A)<\infty$

): Observing that

![]() $k(0)=1$

and

$k(0)=1$

and

![]() $k(1)\le \mathbb{E} \|A_1 \|<1$

by the submultiplicativity of the norm, the convexity of k (see Proposition 2.1) implies that

$k(1)\le \mathbb{E} \|A_1 \|<1$

by the submultiplicativity of the norm, the convexity of k (see Proposition 2.1) implies that

![]() $k'(0)=\gamma<0$

.

$k'(0)=\gamma<0$

.

3. Main results

In this section we state our main results, the proofs of which are deferred to the subsequent sections. We formulate all the results with the minimal set of assumptions required; note that these assumptions are in particular satisfied for model (Rank1Gauss).

3.1. Heavy-tail properties

For completeness, we start by quoting the fundamental result about the tail behavior of R from [Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10] and adapt it to our notation.

Theorem 3.1. ([Reference Guivarc’h and Le Page10, Theorem 5.2].) Assume (i-p-nc),

![]() $\gamma <0$

, and

$\gamma <0$

, and

![]() ${\mathbb{P}}(Ax+B=x)<1$

for all

${\mathbb{P}}(Ax+B=x)<1$

for all

![]() $x \in {\mathbb{R}}^d$

. Assume further that there is an

$x \in {\mathbb{R}}^d$

. Assume further that there is an

![]() $\alpha\in\mathrm{int}(I_k)$

with

$\alpha\in\mathrm{int}(I_k)$

with

![]() $k(\alpha)=1$

,

$k(\alpha)=1$

,

![]() $\mathbb{E}|B|^{\alpha + \varepsilon} < \infty$

, and

$\mathbb{E}|B|^{\alpha + \varepsilon} < \infty$

, and

![]() $\mathbb{E} \|A \|^{\alpha}N(A)^\varepsilon < \infty$

for some

$\mathbb{E} \|A \|^{\alpha}N(A)^\varepsilon < \infty$

for some

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

. Then there is a

$\varepsilon>0$

. Then there is a

![]() $C>0$

such that

$C>0$

such that

Remark 3.1. This fundamental result gives, inter alia, that R is in the domain of attraction of a multivariate

![]() $\alpha$

-stable law if

$\alpha$

-stable law if

![]() $\alpha \in (0,2)$

. In fact, even more can be said about sums of the iterations. Write

$\alpha \in (0,2)$

. In fact, even more can be said about sums of the iterations. Write

![]() $S_n\,:\!=\,\sum_{k=1}^n R_k$

and let

$S_n\,:\!=\,\sum_{k=1}^n R_k$

and let

![]() $ m_R\,:\!=\,\mathbb{E} R$

if

$ m_R\,:\!=\,\mathbb{E} R$

if

![]() $\alpha>1$

(then this expectation is finite). It is shown in [Reference Gao, Guivarc’h and Le Page7, Theorem 1.1] that, under the assumptions of Theorem 3.1, the following holds. If

$\alpha>1$

(then this expectation is finite). It is shown in [Reference Gao, Guivarc’h and Le Page7, Theorem 1.1] that, under the assumptions of Theorem 3.1, the following holds. If

![]() $\alpha>2$

, then

$\alpha>2$

, then

![]() $(S_n-n m_R)/{\sqrt{n}}$

converges in law to a multivariate normal distribution. If

$(S_n-n m_R)/{\sqrt{n}}$

converges in law to a multivariate normal distribution. If

![]() $\alpha=2$

, then

$\alpha=2$

, then

![]() $(S_n-n m_R)/{\sqrt{n \log n}}$

converges in law to a multivariate normal distribution. If

$(S_n-n m_R)/{\sqrt{n \log n}}$

converges in law to a multivariate normal distribution. If

![]() $\alpha \in (0,1) \cup (1,2)$

, let

$\alpha \in (0,1) \cup (1,2)$

, let

![]() $t_n\,:\!=\,n^{-1/\alpha}$

and

$t_n\,:\!=\,n^{-1/\alpha}$

and

![]() $d_n= n t_n m_R \mathbf{1}_{\{\alpha > 1\}}$

. Then

$d_n= n t_n m_R \mathbf{1}_{\{\alpha > 1\}}$

. Then

![]() $(t_n S_n - d_n)$

converges in law to a multivariate

$(t_n S_n - d_n)$

converges in law to a multivariate

![]() $\alpha$

-stable distribution. In all cases, the limit laws are fully nondegenerate.

$\alpha$

-stable distribution. In all cases, the limit laws are fully nondegenerate.

Theorem 3.1 gives, in particular, that

![]() $|R|$

has Pareto-like tails, hence

$|R|$

has Pareto-like tails, hence

![]() $\mathbb{E} |R|^\alpha=\infty$

. Our first result shows that

$\mathbb{E} |R|^\alpha=\infty$

. Our first result shows that

![]() $\mathbb{E} |R_n|^\alpha$

is of order n precisely.

$\mathbb{E} |R_n|^\alpha$

is of order n precisely.

Theorem 3.2. Assume (i-p-nc),

![]() $\gamma <0$

,

$\gamma <0$

,

![]() ${\mathbb{P}}(Ax+B=x)<1$

for all

${\mathbb{P}}(Ax+B=x)<1$

for all

![]() $x\in{\mathbb{R}}^d$

, and that there exists

$x\in{\mathbb{R}}^d$

, and that there exists

![]() $\alpha\in I_k$

with

$\alpha\in I_k$

with

![]() $k(\alpha)=1$

and

$k(\alpha)=1$

and

![]() $\mathbb{E}|B|^\alpha<\infty$

. Then

$\mathbb{E}|B|^\alpha<\infty$

. Then

Remark 3.2. Our result improves [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12, Proposition 10], where it was shown that

![]() $\mathbb{E} |R_n|$

is at most of order

$\mathbb{E} |R_n|$

is at most of order

![]() $n^\alpha$

. Analogous results were obtained in [Reference Buraczewski, Damek and Zienkiewicz6] for the stochastic recursion (1.3) in the one-dimensional case, as well as for a multidimensional case with

$n^\alpha$

. Analogous results were obtained in [Reference Buraczewski, Damek and Zienkiewicz6] for the stochastic recursion (1.3) in the one-dimensional case, as well as for a multidimensional case with

![]() $A_n$

being similarity matrices, i.e. products of orthogonal matrices and dilations.

$A_n$

being similarity matrices, i.e. products of orthogonal matrices and dilations.

While Theorem 3.1 is concerned with the tail behavior of the stationary distribution R, our next theorem gives an upper bound on the tails of finite iterations.

Theorem 3.3. Assume (i-p-nc),

![]() $\gamma <0$

, and that there is an

$\gamma <0$

, and that there is an

![]() $\alpha \in I_k$

with

$\alpha \in I_k$

with

![]() $k(\alpha)=1$

. Assume further that there is an

$k(\alpha)=1$

. Assume further that there is an

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

such that

$\varepsilon>0$

such that

![]() $k(\alpha+\varepsilon)<\infty$

and

$k(\alpha+\varepsilon)<\infty$

and

![]() $\mathbb{E}|B|^{\alpha+\varepsilon}<\infty$

. Then, for each

$\mathbb{E}|B|^{\alpha+\varepsilon}<\infty$

. Then, for each

![]() $n \in \mathbb{N}$

, there is a constant

$n \in \mathbb{N}$

, there is a constant

![]() $C_n$

such that, for all

$C_n$

such that, for all

![]() $t>0$

,

$t>0$

,

![]() ${\mathbb{P}}(|R_n | > t) \le C_n t^{-(\alpha + \varepsilon)}$

.

${\mathbb{P}}(|R_n | > t) \le C_n t^{-(\alpha + \varepsilon)}$

.

Note that the constant

![]() $C_n$

changes with n, but is independent of t. This shows that, for any fixed n, the tails of

$C_n$

changes with n, but is independent of t. This shows that, for any fixed n, the tails of

![]() $R_n$

are of (substantially) smaller order than the tails of the limit R.

$R_n$

are of (substantially) smaller order than the tails of the limit R.

Theorem 3.1 states that the directional behavior of large values of R is governed by

![]() $\nu_\alpha$

, which is given by Proposition 2.1 in an abstract way: as the invariant measure of the operator

$\nu_\alpha$

, which is given by Proposition 2.1 in an abstract way: as the invariant measure of the operator

![]() $P^\alpha$

. The next theorem allows us to obtain a simple expression for both

$P^\alpha$

. The next theorem allows us to obtain a simple expression for both

![]() $\nu_\alpha$

and the top Lyapunov exponent, under assumption (rotinv-p).

$\nu_\alpha$

and the top Lyapunov exponent, under assumption (rotinv-p).

Theorem 3.4 Assume (rotinv-p). Then, for all

![]() $s \in I_k$

,

$s \in I_k$

,

![]() $k(s)= \mathbb{E} | (I-\xi H)e_1| ^s$

and

$k(s)= \mathbb{E} | (I-\xi H)e_1| ^s$

and

![]() $\nu_{s}$

is the uniform measure on S. If, in addition,

$\nu_{s}$

is the uniform measure on S. If, in addition,

![]() $\mathbb{E}(1+\|A\|^s)\log N(A)<\infty$

holds for some

$\mathbb{E}(1+\|A\|^s)\log N(A)<\infty$

holds for some

![]() $s>0$

, then the top Lyapunov exponent

$s>0$

, then the top Lyapunov exponent

![]() $\gamma$

is

$\gamma$

is

Remark 3.3. Our result strengthens [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12, Theorem 3], where the formulae for k(s) and

![]() $\gamma$

were proved for the (Rank1Gauss) model. (3.2) holds, in particular, under (Decay:Symm).

$\gamma$

were proved for the (Rank1Gauss) model. (3.2) holds, in particular, under (Decay:Symm).

Remark 3.4. Note that if

![]() $\|I-\xi H \| < 1$

a.s., then

$\|I-\xi H \| < 1$

a.s., then

![]() $k(s)<1$

for all

$k(s)<1$

for all

![]() $s>0$

, and

$s>0$

, and

![]() ${\mathbb{P}}(|R|>t)=o(t^s)$

for all

${\mathbb{P}}(|R|>t)=o(t^s)$

for all

![]() $s>0$

, i.e. Pareto tails can occur only if

$s>0$

, i.e. Pareto tails can occur only if

![]() ${\mathbb{P}}(\|I-\xi H \|>1)>0$

.

${\mathbb{P}}(\|I-\xi H \|>1)>0$

.

3.2. How does the tail index depend on

$\xi$

?

$\xi$

?

For

![]() $A=I-\xi H$

and the corresponding R, we intend to determine how the tail index of R depends on

$A=I-\xi H$

and the corresponding R, we intend to determine how the tail index of R depends on

![]() $\xi$

, assuming model (rotinv-p). For this model, Theorem 3.4 provides us with the formulae

$\xi$

, assuming model (rotinv-p). For this model, Theorem 3.4 provides us with the formulae

![]() $k(s)=\mathbb{E} | (I-\xi H)e_1| ^s\,=\!:\,h(\xi,s)$

and

$k(s)=\mathbb{E} | (I-\xi H)e_1| ^s\,=\!:\,h(\xi,s)$

and

![]() $\gamma =\mathbb{E} \log|(I-\xi H)e_1|$

. We introduce the function h here to highlight the dependence on both

$\gamma =\mathbb{E} \log|(I-\xi H)e_1|$

. We introduce the function h here to highlight the dependence on both

![]() $\xi$

and s, and to remind the reader that it is equal to the spectral radius k(s) only for this particular model. By Theorem 3.1, the tail index

$\xi$

and s, and to remind the reader that it is equal to the spectral radius k(s) only for this particular model. By Theorem 3.1, the tail index

![]() $\alpha (\xi ) $

of R corresponding to

$\alpha (\xi ) $

of R corresponding to

![]() $\xi $

satisfies

$\xi $

satisfies

For fixed

![]() $\xi>0$

, h is convex as a function of s (see Proposition 2.1), with

$\xi>0$

, h is convex as a function of s (see Proposition 2.1), with

![]() $h(0)=1$

. Thus,

$h(0)=1$

. Thus,

![]() $\gamma=({\partial h}/{\partial s})'(\xi,0)<0$

is a necessary condition for the existence of

$\gamma=({\partial h}/{\partial s})'(\xi,0)<0$

is a necessary condition for the existence of

![]() $\alpha>0$

with

$\alpha>0$

with

![]() $h(\xi,\alpha)=1$

.

$h(\xi,\alpha)=1$

.

A simple calculation shows that

![]() $\gamma \to \infty$

when

$\gamma \to \infty$

when

![]() $\xi \to \infty$

, so (3.3) may happen only for

$\xi \to \infty$

, so (3.3) may happen only for

![]() $\xi$

from a bounded set. However, for an arbitrary law of H it is difficult to determine the set

$\xi$

from a bounded set. However, for an arbitrary law of H it is difficult to determine the set

![]() $U\,:\!=\,\{\xi\colon\mathbb{E}\log|(I-\xi H)e_1|<0\}=\{\xi\colon\gamma(\xi)<0\}$

directly. Therefore, we will provide sufficient conditions for

$U\,:\!=\,\{\xi\colon\mathbb{E}\log|(I-\xi H)e_1|<0\}=\{\xi\colon\gamma(\xi)<0\}$

directly. Therefore, we will provide sufficient conditions for

![]() $U \neq \emptyset$

.

$U \neq \emptyset$

.

Theorem 3.5. Consider

![]() $A=\mathrm{I} - \xi H$

with variable

$A=\mathrm{I} - \xi H$

with variable

![]() $\xi>0$

. Assume (rotinv-p), and that

$\xi>0$

. Assume (rotinv-p), and that

![]() ${\mathrm{supp}}(H)$

is unbounded. Assume

${\mathrm{supp}}(H)$

is unbounded. Assume

![]() $s_0=\infty$

, and that

$s_0=\infty$

, and that

Then the following hold:

-

(i) There is a unique

$\xi _1>0$

such that

$\xi _1>0$

such that

$h(\xi _1,1)=1$

and, for every

$h(\xi _1,1)=1$

and, for every

$\xi \in (0,\xi_1)$

, there is a unique

$\xi \in (0,\xi_1)$

, there is a unique

$\alpha =\alpha (\xi )>1$

such that

$\alpha =\alpha (\xi )>1$

such that

$h(\xi, \alpha (\xi))=1$

. In particular,

$h(\xi, \alpha (\xi))=1$

. In particular,

$\mathbb{E}\log|(I-\xi H)e_1|<0$

for all

$\mathbb{E}\log|(I-\xi H)e_1|<0$

for all

$\xi \in (0,\xi _1]$

and the set U is nonempty.

$\xi \in (0,\xi _1]$

and the set U is nonempty. -

(ii) The function

$\xi \mapsto \alpha (\xi)$

is strictly decreasing and in

$\xi \mapsto \alpha (\xi)$

is strictly decreasing and in

$\mathcal{C}^{1}((0,\xi_1))$

, with

$\mathcal{C}^{1}((0,\xi_1))$

, with

$\lim _{\xi \to 0^+}\alpha (\xi )=\infty$

and

$\lim _{\xi \to 0^+}\alpha (\xi )=\infty$

and

$\lim _{\xi \to \xi ^-_1}\alpha (\xi )=1$

.

$\lim _{\xi \to \xi ^-_1}\alpha (\xi )=1$

. -

(iii) For

$\xi \in U$

with

$\xi \in U$

with

$\xi >\xi _1$

,

$\xi >\xi _1$

,

$\alpha(\xi )<1$

.

$\alpha(\xi )<1$

.

The conditions of Theorem 3.5 are satisfied in particular if we impose a density assumption. Suppose that H is positive definite a.s., and (Decay:Symm) holds. Then, by Theorem 3.6, condition (3.4) is satisfied, and we have the following corollary.

Corollary 3.1. Assume (rotinv-p), (Decay:Symm), that H is positive definite a.s.,

![]() ${\mathrm{supp}}(H)$

is unbounded, and

${\mathrm{supp}}(H)$

is unbounded, and

![]() $s_0=\infty$

. Then the tail index

$s_0=\infty$

. Then the tail index

![]() $\alpha$

is strictly decreasing in the step size

$\alpha$

is strictly decreasing in the step size

![]() $\eta$

and strictly increasing in the batch size b, provided that

$\eta$

and strictly increasing in the batch size b, provided that

![]() $\alpha>1$

.

$\alpha>1$

.

In particular, our result generalizes [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12, Theorem 3] (which covers (Rank1Gauss) only).

Remark 3.5. The assumption

![]() $\mathbb{E} \langle He_1,e_1\rangle >0$

will imply that

$\mathbb{E} \langle He_1,e_1\rangle >0$

will imply that

![]() $U \neq \emptyset$

, while the second assumption in (3.4) is used to ensure that

$U \neq \emptyset$

, while the second assumption in (3.4) is used to ensure that

![]() $h\in C^1((0,\infty )\times(1,\infty ))$

, which we need to employ the implicit function theorem to study properties of

$h\in C^1((0,\infty )\times(1,\infty ))$

, which we need to employ the implicit function theorem to study properties of

![]() $\xi \mapsto \alpha(\xi)$

. Note that

$\xi \mapsto \alpha(\xi)$

. Note that

![]() $\mathbb{E} \langle He_1,e_1\rangle >0$

is automatically satisfied in the (Rank1) case.

$\mathbb{E} \langle He_1,e_1\rangle >0$

is automatically satisfied in the (Rank1) case.

For

![]() $\xi \in U$

with

$\xi \in U$

with

![]() $\xi > \xi_1$

, there still exists a unique

$\xi > \xi_1$

, there still exists a unique

![]() $\alpha(\xi)$

which then satisfies

$\alpha(\xi)$

which then satisfies

![]() $\alpha(\xi)<1$

. However, we are not able to prove the

$\alpha(\xi)<1$

. However, we are not able to prove the

![]() $\mathcal{C}^1$

regularity of

$\mathcal{C}^1$

regularity of

![]() $h(\xi,s)$

when

$h(\xi,s)$

when

![]() $s<1$

since

$s<1$

since

![]() $\partial h/\partial \xi$

does not exist when

$\partial h/\partial \xi$

does not exist when

![]() $\xi$

satisfies

$\xi$

satisfies

![]() $\det(I-\xi H)=0$

; see the proof of Lemma 5.2 for details.

$\det(I-\xi H)=0$

; see the proof of Lemma 5.2 for details.

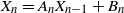

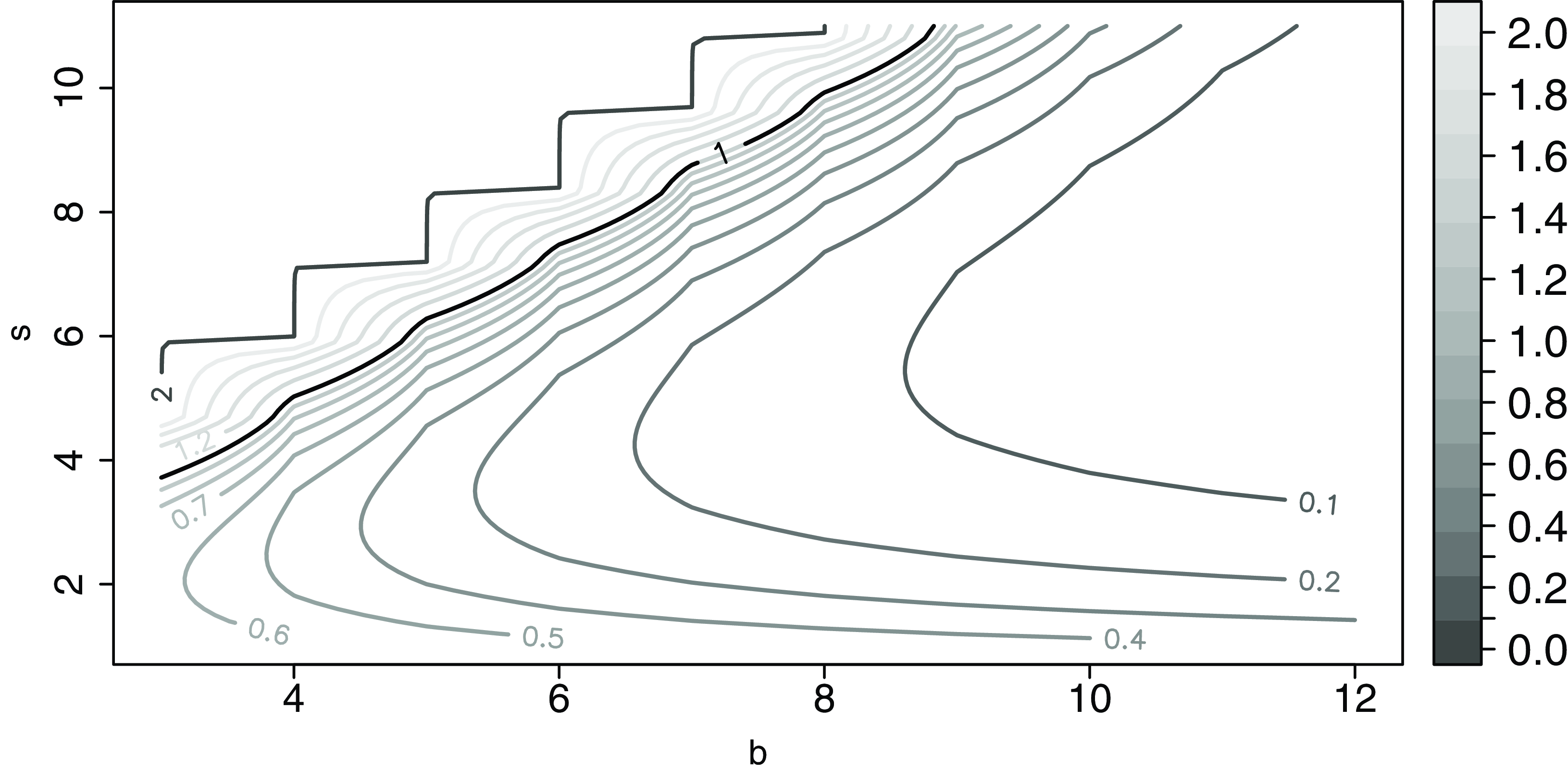

The behavior of h for different values of the batch size b and step size

![]() $\eta$

is shown in Figures 1 and 2 respectively.

$\eta$

is shown in Figures 1 and 2 respectively.

Figure 1. Contour plot of h as a function of b and s for model (Rank1Gauss) with

![]() $d=2$

and

$d=2$

and

![]() $\eta=0.75$

. The black line is the contour of

$\eta=0.75$

. The black line is the contour of

![]() $k\equiv1$

. The values of h have been cut at level 2 for better visualization.

$k\equiv1$

. The values of h have been cut at level 2 for better visualization.

Figure 2. Contour plot of h as a function of

![]() $\eta$

and s for model (Rank1Gauss) with

$\eta$

and s for model (Rank1Gauss) with

![]() $d=2$

and

$d=2$

and

![]() $b=5$

. The black line is the contour of

$b=5$

. The black line is the contour of

![]() $k\equiv1$

. The values of h have been cut at level 2 for better visualization.

$k\equiv1$

. The values of h have been cut at level 2 for better visualization.

3.3. Checking the assumptions – the model (Rank1Gauss)

The following results confirm the hierarchy of our assumptions.

Lemma 3.1. Concerning the conditions imposed for the various models considered, we have the following implications:

Moreover, if we consider model (Rank1) with i.i.d.

![]() $a_i$

,

$a_i$

,

![]() $1 \le i \le b$

, such that the law of

$1 \le i \le b$

, such that the law of

![]() $a_i$

is rotationally invariant with

$a_i$

is rotationally invariant with

![]() ${\mathrm{supp}}(a_i)={\mathbb{R}}^d$

, then (rotinv-p) is satisfied as well.

${\mathrm{supp}}(a_i)={\mathbb{R}}^d$

, then (rotinv-p) is satisfied as well.

Our next result is concerned with the density of the law of

![]() $H=\sum_{i=1}^b a_ia_i^\top$

in the (Rank1Gauss) model. The entries of

$H=\sum_{i=1}^b a_ia_i^\top$

in the (Rank1Gauss) model. The entries of

![]() $g\in {\mathrm{Sym}(d,\mathbb{R})}$

will be denoted

$g\in {\mathrm{Sym}(d,\mathbb{R})}$

will be denoted

![]() $g_{ij}$

, i.e.

$g_{ij}$

, i.e.

![]() $g=(g_{ij})$

, where

$g=(g_{ij})$

, where

![]() $g_{ij}=g_{ji}$

. We identify

$g_{ij}=g_{ji}$

. We identify

![]() ${\mathrm{Sym}(d,\mathbb{R})}$

with

${\mathrm{Sym}(d,\mathbb{R})}$

with

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^{d(d+1)/2}$

. Observe that then the Frobenius norm of g is bounded by the Euclidean norm of the corresponding vector x of

${\mathbb{R}}^{d(d+1)/2}$

. Observe that then the Frobenius norm of g is bounded by the Euclidean norm of the corresponding vector x of

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^{d(d+1)/2}$

, which contains the diagonal and upper diagonal entries of g:

${\mathbb{R}}^{d(d+1)/2}$

, which contains the diagonal and upper diagonal entries of g:

![]() $\|g \|_{\mathrm{F}} \le 2 |x |$

.

$\|g \|_{\mathrm{F}} \le 2 |x |$

.

Lemma 3.2. Assume (Rank1Gauss). If

![]() $b > d+1$

, then

$b > d+1$

, then

![]() $H=\sum_{i=1}^b a_ia_i^\top$

has a density f with respect to Lebesgue measure on

$H=\sum_{i=1}^b a_ia_i^\top$

has a density f with respect to Lebesgue measure on

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^{d(d+1)/2}$

that satisfies

${\mathbb{R}}^{d(d+1)/2}$

that satisfies

![]() $f(x)\leq C(1+|x |^2)^{-D}$

for all

$f(x)\leq C(1+|x |^2)^{-D}$

for all

![]() $D>0$

and some constant

$D>0$

and some constant

![]() $C=C(D)$

depending only on D.

$C=C(D)$

depending only on D.

In particular, it is possible to choose

![]() $D>{d(d+1)}/{4}$

in Lemma 3.2 so that the condition (Decay:Symm) is satisfied. The next result gives that the decay assumptions are sufficient for the existence of negative moments, which are required in the previous theorems. Its proof is contained in Section 7.

$D>{d(d+1)}/{4}$

in Lemma 3.2 so that the condition (Decay:Symm) is satisfied. The next result gives that the decay assumptions are sufficient for the existence of negative moments, which are required in the previous theorems. Its proof is contained in Section 7.

Theorem 3.6. Consider model (Symm) with (Decay:Symm) or model (Rank1) with (Decay:Rank1). Then, for every

![]() $0\leq \delta < 1/ 2$

and

$0\leq \delta < 1/ 2$

and

![]() $\xi$

,

$\xi$

,

and for every

![]() $s<s_0$

,

$s<s_0$

,

![]() $\mathbb{E} (1+\|A \|^s) N(A)^\varepsilon<\infty$

for some

$\mathbb{E} (1+\|A \|^s) N(A)^\varepsilon<\infty$

for some

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

. Further, for every

$\varepsilon>0$

. Further, for every

![]() $0 < \delta < 1$

,

$0 < \delta < 1$

,

![]() $\mathbb{E}|\langle He_2,e_1\rangle|^{-\delta}<\infty$

.

$\mathbb{E}|\langle He_2,e_1\rangle|^{-\delta}<\infty$

.

3.4. Examples

3.4.1. Linear regression with Gaussian data distribution and constant step size.

This is the model (Rank1Gauss) studied in [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Simsekli and Zhu12] and discussed in the introduction. All results are valid for this particular model.

Corollary 3.2. Assume (Rank1Gauss) with

![]() $b>d+1$

, i.e.

$b>d+1$

, i.e.

\begin{align*}A = \mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^ba_ia_i^{\top}, \qquad B = \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^ba_iy_i,\end{align*}

\begin{align*}A = \mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^ba_ia_i^{\top}, \qquad B = \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^ba_iy_i,\end{align*}

where

![]() $a_i$

,

$a_i$

,

![]() $1 \le i \le b$

are i.i.d. standard Gaussian random vectors in

$1 \le i \le b$

are i.i.d. standard Gaussian random vectors in

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^d$

, independent of

${\mathbb{R}}^d$

, independent of

![]() $y_i$

. Then the assertions of Theorems 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, and 3.5 hold. The tail index

$y_i$

. Then the assertions of Theorems 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, and 3.5 hold. The tail index

![]() $\alpha$

is strictly decreasing in the step size

$\alpha$

is strictly decreasing in the step size

![]() $\eta$

and strictly increasing in the batch size b, provided that

$\eta$

and strictly increasing in the batch size b, provided that

![]() $\alpha>1$

.

$\alpha>1$

.

3.4.2. Linear regression with continuous data distribution and i.i.d. step size.

We may easily go beyond the previous example and consider model (Rank1) with an arbitrary (continuous) distribution for

![]() $a_i$

that is rotationally invariant (cf. Remark 2.1) with

$a_i$

that is rotationally invariant (cf. Remark 2.1) with

![]() ${\mathrm{supp}}(a_i)={\mathbb{R}}^d$

and satisfies (Decay:Rank1). This is satisfied, for example, if

${\mathrm{supp}}(a_i)={\mathbb{R}}^d$

and satisfies (Decay:Rank1). This is satisfied, for example, if

![]() $a_i$

are i.i.d. (as assumed in (Rank1)). with generic copy a such that the density of the law of a is bounded, depends only on

$a_i$

are i.i.d. (as assumed in (Rank1)). with generic copy a such that the density of the law of a is bounded, depends only on

![]() $|a|$

, and is of order

$|a|$

, and is of order

![]() $o(|a|^{-db})$

as

$o(|a|^{-db})$

as

![]() $|a|\to \infty$

.

$|a|\to \infty$

.

In addition, similar to [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Hu, Simsekli and Zhu11, Theorem 11], we may allow for i.i.d. random step sizes, meaning that

![]() $\eta_n$

is a sequence of i.i.d. positive random variables with generic copy

$\eta_n$

is a sequence of i.i.d. positive random variables with generic copy

![]() $\eta$

.

$\eta$

.

Corollary 3.3. Assume (Rank1) with random i.i.d. step sizes taking values in a compact interval

![]() $J\subset (0,\infty)$

, i.e.

$J\subset (0,\infty)$

, i.e.

\begin{align*}A =\mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^ba_ia_i^{\top}, \qquad B = \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^ba_iy_i,\end{align*}

\begin{align*}A =\mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^ba_ia_i^{\top}, \qquad B = \frac{\eta}{b}\sum_{i=1}^ba_iy_i,\end{align*}

where

![]() $(a_i,y_i)$

,

$(a_i,y_i)$

,

![]() $1 \le i \le b$

, are i.i.d. and the distribution of

$1 \le i \le b$

, are i.i.d. and the distribution of

![]() $a_i$

is an arbitrary continuous distribution that is rotationally invariant with

$a_i$

is an arbitrary continuous distribution that is rotationally invariant with

![]() ${\mathrm{supp}}(a_i)={\mathbb{R}}^d$

and satisfies (Decay:Rank1). Further,

${\mathrm{supp}}(a_i)={\mathbb{R}}^d$

and satisfies (Decay:Rank1). Further,

![]() $\eta$

is a random variable taking values in J that is independent of

$\eta$

is a random variable taking values in J that is independent of

![]() $(a_i,b_i)$

,

$(a_i,b_i)$

,

![]() $1 \le i \le b$

. Assume that

$1 \le i \le b$

. Assume that

![]() ${\mathbb{P}}(Ax+B=x)<1$

is satisfied. Then the assertions of Theorems 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, and 3.5 hold. The tail index

${\mathbb{P}}(Ax+B=x)<1$

is satisfied. Then the assertions of Theorems 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, and 3.5 hold. The tail index

![]() $\alpha$

is strictly increasing in the batch size b, provided that

$\alpha$

is strictly increasing in the batch size b, provided that

![]() $\alpha>1$

.

$\alpha>1$

.

Proof. We have to check that the introduction of the random step size does not affect the validity of the assumptions. This is obvious for the rotation invariance, since

![]() $\eta$

is scalar. Concerning condition (Decay:Rank1), consider the case where

$\eta$

is scalar. Concerning condition (Decay:Rank1), consider the case where

![]() $\eta$

has a density h on the interval

$\eta$

has a density h on the interval

![]() $J=[j_1,j_2]$

. Given that (Decay:Rank1) holds for the joint density f of

$J=[j_1,j_2]$

. Given that (Decay:Rank1) holds for the joint density f of

![]() $(a_1, \ldots, a_b)$

, then by standard calculations (see, e.g., [Reference Grimmett and Stirzaker9, Example 4.7.6]) the joint density g of

$(a_1, \ldots, a_b)$

, then by standard calculations (see, e.g., [Reference Grimmett and Stirzaker9, Example 4.7.6]) the joint density g of

![]() $(\eta a_1, \ldots, \eta a_b)$

satisfies

$(\eta a_1, \ldots, \eta a_b)$

satisfies

\begin{align*} g(y_1,\ldots,y_d) & = \int_Jf(y_1/x,\ldots,y_b/x)h(x)\frac{1}{x^{bd}}\,\mathrm{d} x \\[5pt] & \le \int_JC\Bigg(1+\sum_{i=1}^b\frac1{x^2}|y_i|^2\Bigg)^{-D}h(x)\frac{1}{x^{bd}}\,\mathrm{d} x \\[5pt] & \le C\Bigg(1+\frac{1}{j_2^2}\sum_{i=1}^b|y_i|^2\Bigg)^{-D}\frac{1}{j_1^{bd}} \le C'\Bigg(1+\sum_{i=1}^b|y_i|^2\Bigg)^{-D}. \end{align*}

\begin{align*} g(y_1,\ldots,y_d) & = \int_Jf(y_1/x,\ldots,y_b/x)h(x)\frac{1}{x^{bd}}\,\mathrm{d} x \\[5pt] & \le \int_JC\Bigg(1+\sum_{i=1}^b\frac1{x^2}|y_i|^2\Bigg)^{-D}h(x)\frac{1}{x^{bd}}\,\mathrm{d} x \\[5pt] & \le C\Bigg(1+\frac{1}{j_2^2}\sum_{i=1}^b|y_i|^2\Bigg)^{-D}\frac{1}{j_1^{bd}} \le C'\Bigg(1+\sum_{i=1}^b|y_i|^2\Bigg)^{-D}. \end{align*}

In the penultimate step we have used that in the integral,

![]() $0 < j_1\le x \le j_2$

; in the last step we included these factors in the constant.

$0 < j_1\le x \le j_2$

; in the last step we included these factors in the constant.

Remark 3.6. (Linear regression with a finite set of data points.) If

![]() $a_i$

takes only finitely many different values, i.e.

$a_i$

takes only finitely many different values, i.e.

![]() ${\mathrm{supp}}(a_i)=\{v_1,\ldots,v_m\}$

, then the irreducibility condition of (i-p-nc) is violated: the union of the one-dimensional subspaces

${\mathrm{supp}}(a_i)=\{v_1,\ldots,v_m\}$

, then the irreducibility condition of (i-p-nc) is violated: the union of the one-dimensional subspaces

![]() $W_j=\mathrm{span}(v_j)$

is

$W_j=\mathrm{span}(v_j)$

is

![]() $G_A$

invariant. This is why this setting is outside the scope of our paper, but we believe that similar results hold when applying Markov renewal theory with finite state space – for example, the operator

$G_A$

invariant. This is why this setting is outside the scope of our paper, but we believe that similar results hold when applying Markov renewal theory with finite state space – for example, the operator

![]() $P^\alpha$

would become a (finite-dimensional) transition matrix.

$P^\alpha$

would become a (finite-dimensional) transition matrix.

Still, there are simple settings where A takes only two distinct values and condition (i-p-nc) is satisfied; namely, if

![]() $d=2$

,

$d=2$

,

![]() ${\mathrm{supp}}(A)$

contains an irrational rotation, and a proximal matrix; see [Reference Bougerol and Lacroix3, Proposition 2.5] for further information.

${\mathrm{supp}}(A)$

contains an irrational rotation, and a proximal matrix; see [Reference Bougerol and Lacroix3, Proposition 2.5] for further information.

3.4.3. Quadratic loss function with cyclic step size.

Note that we cannot cover general time-dependent learning rates because then we would lose the i.i.d. property of the sequence

![]() $(A_i)_{i \ge 1}$

. However, our setup allows us to study the effect of cyclic step sizes, as introduced in [Reference Smith19]; see also [Reference Smith20], as well as [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Hu, Simsekli and Zhu11, Theorem 5] for a recent related treatment.

$(A_i)_{i \ge 1}$

. However, our setup allows us to study the effect of cyclic step sizes, as introduced in [Reference Smith19]; see also [Reference Smith20], as well as [Reference Gürbüzbalaban, Hu, Simsekli and Zhu11, Theorem 5] for a recent related treatment.

Here,

![]() $\eta_n$

takes values from a finite set

$\eta_n$

takes values from a finite set

![]() $\{c_1, \ldots, c_m\}$

in a cyclic way:

$\{c_1, \ldots, c_m\}$

in a cyclic way:

![]() $\eta_n = c_j$

if and only if m divides

$\eta_n = c_j$

if and only if m divides

![]() $(n-j)$

. Then

$(n-j)$

. Then

![]() $A_i$

,

$A_i$

,

![]() $1 \le i \le n$

, are no longer i.i.d., but their m-fold products (covering one cycle of step sizes) are. It is well known (cf. [Reference Vervaat22, Lemma 1.2]) that R satisfies (2.6) if and only if

$1 \le i \le n$

, are no longer i.i.d., but their m-fold products (covering one cycle of step sizes) are. It is well known (cf. [Reference Vervaat22, Lemma 1.2]) that R satisfies (2.6) if and only if

where R is independent of

![]() $(A_1,B_1, \ldots, A_m, B_m)$

and

$(A_1,B_1, \ldots, A_m, B_m)$

and

![]() $B^{(m)}=\sum_{j=1}^m\Pi_{j-1}B_j$

. Hence, we may analyze (3.6) instead of (2.6). Note that the (Rank1) structure is not preserved when going from A to

$B^{(m)}=\sum_{j=1}^m\Pi_{j-1}B_j$

. Hence, we may analyze (3.6) instead of (2.6). Note that the (Rank1) structure is not preserved when going from A to

![]() $\Pi_m$

, but property (rotinv-p) remains valid for

$\Pi_m$

, but property (rotinv-p) remains valid for

![]() $\Pi_m$

, if it holds for A. This is why we cannot recover all the results in this setting, and also why we consider directly here the more general model (Symm) that corresponds to a quadratic loss function

$\Pi_m$

, if it holds for A. This is why we cannot recover all the results in this setting, and also why we consider directly here the more general model (Symm) that corresponds to a quadratic loss function

![]() $\ell(x,H)=x^\top H x$

, where the symmetric matrix H takes the role of the data Z. Recall that this includes (Rank1) as a particular case.

$\ell(x,H)=x^\top H x$

, where the symmetric matrix H takes the role of the data Z. Recall that this includes (Rank1) as a particular case.

Corollary 3.4 Assume (Symm) with cyclic step sizes

![]() $\{c_1, \ldots, c_m\}$

, i.e.

$\{c_1, \ldots, c_m\}$

, i.e.

\begin{align*}A_n = \mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta_n}{b}\sum_{i =1}^bH_{i,n},\end{align*}

\begin{align*}A_n = \mathrm{I} - \frac{\eta_n}{b}\sum_{i =1}^bH_{i,n},\end{align*}

with

![]() $\eta_n=c_j$

if and only if m divides

$\eta_n=c_j$

if and only if m divides

![]() $(n-j)$

and where

$(n-j)$

and where

![]() $H_{i,n}$

,

$H_{i,n}$

,

![]() $1 \le i \le b$

,

$1 \le i \le b$

,

![]() $n \ge 1$

, are i.i.d. random symmetric matrices with unbounded support such that (rotinv-p) and (Decay:Symm) hold. Then the assertions of Theorems 3.1 and 3.2 hold. Further, Theorem 3.3 holds with