Statement of Research Significance

Research Question(s) or Topic(s): This study explored how to best demonstrate the value and impact of neuropsychological assessment (NPA) across healthcare settings by identifying key outcomes, existing measures, and challenges in outcome evaluation. Main Findings: Focus groups identified 50 potential outcomes of NPA. After a Delphi consensus process, 16 reached expert consensus, with the top three being: 1) improved understanding of presenting problems, ii) improved understanding of how to manage cognitive symptoms and iii) diagnostic clarification. Existing validated measures for these outcomes are limited. Study Contributions: This study provides a consensus-based framework of meaningful outcomes of NPA. It reveals a critical gap in available measurement tools – especially for psychoeducational benefits. It underscores the need to develop valid, standardized measures to assess the impact of neuropsychological services in clinical research and practice.

Introduction

Neuropsychological assessment (NPA) involves comprehensive evaluation of cognitive, psychological, and behavioral functioning to clarify diagnosis and prognosis of brain conditions, characterize cognitive strengths and weaknesses, evaluate a person’s capacity to make decisions or participate in certain activities or roles, and guide patient management, rehabilitation, and support. The utility of NPA has been shown in observational studies across a variety of neurological, mental health, and medical conditions (e.g., Donders, Reference Donders2020; Watt & Crowe, Reference Watt and Crowe2018) and has been found to reduce hospital service use (VanKirk et al., Reference VanKirk, Horner, Turner, Dismuke and Muzzy2013) and improve self-efficacy (Lanca et al., Reference Lanca, Giuliano, Sarapas, Potter, Kim, West and Chow2020). Referring providers report that NPA services are a valuable addition to patient care (Allahham et al., Reference Allahham, Wong and Pike2023; Allott et al., Reference Allott, Brewer, McGorry and Proffitt2011; Donofrio et al., Reference Donofrio, Piatt, Whelihan and DiCarlo1999; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Zimak, Sherwood and Elias2020; Hilsabeck et al., Reference Hilsabeck, Hietpas and McCoy2014; Mahoney et al., Reference Mahoney, Bajo, De Marco, Arredondo, Hilsabeck and Broshek2017; Postal et al., Reference Postal, Chow, Jung, Erickson-Moreo, Geier and Lanca2018; Spano et al., Reference Spano, Katz, DeLuco, Martin, Tam, Montalto and Stein2021). However, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that provide causal evidence of the impact of NPA are lacking, and those that have been done have not measured key potential benefits such as improved patient understanding of their brain condition and how to manage it (Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Dent, Harding, Weyman, Nicholl, Blumhardt and Playford2002; McKinney et al., Reference McKinney, Blake, Treece, Lincoln, Playfordand and Gladman2002).

It is increasingly important to demonstrate the value of neuropsychology in an era of resource-limited health care (Pliskin, Reference Pliskin2018) in which access to neuropsychological services is limited. Allott and colleagues (Reference Allott, Van‐der‐el, Bryce, Hamilton, Adams, Burgat, Killackey and Rickwood2019) found that while a large proportion of the client base of youth mental health services in Australia were believed to have cognitive difficulties or would benefit from NPA, only 12% of the clients received the service when needed. Similarly, an online survey of members of neuropsychological societies in Europe concluded that the low number of neuropsychologists in many European countries was insufficient to meet the needs of people with brain conditions in those countries (Kasten et al., Reference Kasten, Barbosa, Kosmidis, Persson, Constantinou, Baker, Lettner, Hokkanen, Ponchel, Mondini, Jonsdottir, Varako, Nikolai, Pranckeviciene, Harper and Hessen2021). Barriers to accessing neuropsychological services include limited availability in public health services, and exclusion of NPA from government funding, such as Australia’s Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS; Department of Health and Aged Care, 2025; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Hetrick, Merrett, Parrish and Allott2017). To bridge this gap and increase the provision of accessible, affordable neuropsychological services, governments and insurance companies require high-quality, RCT-level evidence that highlights the clinical utility of neuropsychology. Indeed, a bid to include NPA as a billable item in Australia’s Medicare Benefits Schedule (which provides rebates to patients for listed service items), which was submitted about 10 years ago, was rejected on the basis that there were only two RCTs evaluating outcomes of NPA and both had negative findings (Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Dent, Harding, Weyman, Nicholl, Blumhardt and Playford2002; McKinney et al., Reference McKinney, Blake, Treece, Lincoln, Playfordand and Gladman2002).

To design RCTs which could provide such evidence, we need outcome measures that detect quantifiable changes that occur as a direct result of NPA. Several prominent neuropsychologists in the USA have identified the need to develop outcome measures that are unique to neuropsychological services, to demonstrate our specific value or “return on investment” to insurers who fund NPA services (Glen et al., Reference Glen, Hostetter, Roebuck-Spencer, Garmoe, Scott, Hilsabeck, Arnett and Espe-Pfeifer2020; Pliskin, Reference Pliskin2018). This is challenging, as NPAs are a limited, short-term form of clinical input, and outcomes differ widely depending on the referral question. For example, a referral which seeks to clarify an individual’s capacity to make financial decisions has distinct outcomes from a referral which seeks to evaluate neuropsychological functioning pre- and post-focal resection for treatment of epilepsy. To classify outcomes of pediatric neuropsychology services in their systematic review, (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Zimak, Sherwood and Elias2020) proposed four levels of potential outcomes of NPA: 1) internal experiences/reactions (e.g., changes in knowledge or understanding), 2) actions or behavior change (e.g., implementation of recommendations), 3) changes in symptoms or functioning (e.g., improved mood or subjective cognitive complaints), and 4) high-level consequences with financial or economic impacts (e.g., health service utilization). Level 1 outcomes are the most proximal to the NPA as they occur as a direct result of the NPA and can be observed immediately afterwards; whereas Level 2–4 outcomes are increasingly distal or “downstream” from the NPA, therefore more difficult to demonstrate as causally related to the NPA. For example, changes in symptoms or functioning (Level 3) may only result if the NPA led to the person accessing evidence-based interventions to improve their symptoms. The two main RCTs to directly evaluate the outcomes of NPA, McKinney et al. (Reference McKinney, Blake, Treece, Lincoln, Playfordand and Gladman2002) and Lincoln et al. (Reference Lincoln, Dent, Harding, Weyman, Nicholl, Blumhardt and Playford2002), found no significant effect of NPA on functional outcomes, quality of life, mood, or subjective cognitive impairment in cohorts with stroke and multiple sclerosis, respectively; effect sizes on these outcomes were trivial to small. However, the outcomes they measured were all at Level 3 of Fisher et al.’s (Reference Fisher, Zimak, Sherwood and Elias2020) framework, and therefore potentially too distal from the NPA to capture meaningful change.

There is a clear need to identify key outcomes of NPA that are most relevant and most likely to detect impacts of NPA. More recently, Colvin et al. (Reference Colvin, Roebuck-Spencer, Sperling, Acheson, Bailie, Espe-Pfeifer, Glen, Bragg, Bott and Hilsabeck2022) proposed a conceptual framework to link neuropsychological practice with positive patient outcomes. They defined a core set of patient-centered outcomes and neuropsychological processes that apply across clinical settings and populations. According to their conceptual framework, the most universally applicable outcomes were quality of life, health-related behaviors and functional independence, treatment adherence, safety, and caregiver knowledge and well-being and family functioning. However, their list was not exhaustive and appeared to be generated by the authors; as far as we are aware, it has not yet undergone a consensus process or other validation. Notably, besides caregiver knowledge, the list did not include other proximal outcomes falling in Level 1 of Fisher and colleagues’ (Reference Fisher, Zimak, Sherwood and Elias2020) outcome classification framework.

Measurement of proximal outcomes such as knowledge and understanding of the presenting conditions and how to cope with them have shown promise in observational studies (Arffa & Knapp, Reference Arffa and Knapp2008; Austin et al., Reference Austin, Gerstle, Baum, Bradley, LeJeune, Peugh and Beebe2019; Combs et al., Reference Combs, Beebe, Austin, Gerstle and Peugh2020; Lanca et al., Reference Lanca, Giuliano, Sarapas, Potter, Kim, West and Chow2020; Mountjoy et al., Reference Mountjoy, Field, Stapleton and Kemp2017; Rosado et al., Reference Rosado, Buehler, Botbol-Berman, Feigon, León, Luu, Carrión, Gonzalez, Rao, Greif, Seidenberg and Pliskin2018). Typically, these observational studies have used bespoke measures created for their studies to measure these proximal outcomes; for example, Likert-rating scales asking “How well do you feel you understand your current condition?” and “How well do you feel you can manage or cope with your condition?” (Rosado et al., Reference Rosado, Buehler, Botbol-Berman, Feigon, León, Luu, Carrión, Gonzalez, Rao, Greif, Seidenberg and Pliskin2018), or measures of attainment of NPA-specific goals (Lanca et al., Reference Lanca, Giuliano, Sarapas, Potter, Kim, West and Chow2020). Several of these studies highlighted the impact of NPA feedback on patient understanding of their neuropsychological condition and their confidence in managing it (e.g., Rosado et al., Reference Rosado, Buehler, Botbol-Berman, Feigon, León, Luu, Carrión, Gonzalez, Rao, Greif, Seidenberg and Pliskin2018). This accords with growing evidence in support of the benefits of NPA feedback for a range of patient outcomes (Gruters et al., Reference Gruters, Ramakers, Verhey, Kessels and de Vugt2021; Longley et al., Reference Longley, Tate and Brown2023). Key models of NPA feedback delivery (Finn & Martin, Reference Finn, Martin, Geisinger, Bracken, Carlson, Hansen, Kuncel, Reise and Rodriguez2013; Gorske & Smith, Reference Gorske and Smith2009; Postal & Armstrong, Reference Postal and Armstrong2013) and clinician competency frameworks (Wong, Pinto, et al., Reference Wong, Pinto, Price, Watson and McKay2023) emphasize clear, meaningful explanations of the patient’s condition and how to manage it. Surveys of feedback practices in the USA (Varela et al., Reference Varela, Sperling, Block, O’Leary, Hart and Kiselica2024) and Australia (McRae et al., Reference McRae, Kelly, Bowman, Schofield and Wong2023) indicate that the majority of clinicians deliver feedback as part of standard clinical NPA practice. Together, this suggests that the psychoeducational impacts of NPA that includes feedback to patients and families may be important patient-reported outcomes that are worth measuring in experimental trials.

Given that existing research has not always measured the most appropriate outcomes, systematic review may not be the best methodology for identifying key outcomes of NPA that are likely to detect change in clinical trials. Expert consensus methodology (Skulmoski et al., Reference Skulmoski, Hartman and Krahn2007) has the potential to do this more meaningfully, by asking expert clinical neuropsychologists for their opinions on what impacts they typically observe and any issues they anticipate in measuring those. Identifying existing outcome measures can also inform the need for development of new measurement tools. The aims of this study were to identify i) the key potential outcomes of NPA across a variety of contexts and settings; ii) existing tools available to measure those outcomes, and iii) issues and challenges associated with measuring these outcomes, with the broader aim of identifying the best outcomes to measure in future clinical trials evaluating the benefits of NPA and informing possible measure development.

Method

Design

This was a mixed-methods study incorporating i) focus groups to generate a list of potential outcomes of NPA and associated outcome measures; and measurement issues and challenges, analyzed qualitatively; and ii) a Delphi study to seek expert consensus on the list of potential outcomes generated by the focus groups, and further information regarding existing measures of those outcomes. The Delphi method is a multi-stage, iterative technique that seeks to gain expert consensus on a topic by asking structured questions across multiple rounds until consensus is achieved (Hsu & Sandford, Reference Hsu and Sandford2007).

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (HEC19196). The research was completed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All participants provided informed consent. Data collection occurred between March-October 2019.

Focus groups

Participants

Focus group participants were recruited from an Australian neuropsychology interest group on outcome measurement convened by DW in 2018 via the NPinOz email list (a google group with >1200 members). Inclusion criteria for the focus groups were i) at least five years’ experience as a clinical neuropsychologist and ii) experience in service management. The target group size was 6–10 participants (Millward, Reference Millward, Breakwell, Hammond and Fife-Schaw1995).

Focus group content and structure

Semi-structured interview questions were used to i) identify short- and long-term outcomes of NPA, at the individual, close other (e.g., family) and organization levels; ii) generate ideas about existing outcome measures for any outcomes identified; and iii) explore issues and challenges associated with measuring these outcomes. Researchers DW and SP facilitated two focus groups which each ran for 90–120 minutes.

Data analysis

The focus group discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed by a professional transcription service, and analyzed using NVivo software. Analysis of the transcripts was primarily guided by Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun and Clarke2021) reflexive thematic analysis approach, within a critical realist orientation to the data. To generate the list of the potential outcomes of NPA and associated measures, a “codebook” thematic analysis approach was used using semantic coding (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021) to capture predefined information (i.e., regarding potential NPA outcomes and associated measures). Any mention of an outcome or outcome measure was documented by SP. This was checked against photographs of the whiteboard notes that were made during the focus group. The resulting list of outcomes and outcomes measures was then checked and verified by DW. To analyze the discussion of measurement challenges and issues, data were coded by SP using a mixture of semantic and more interpretative/latent codes. These codes were critically reviewed by DW, and revised through discussion with SP. Themes were reflexively generated from the codes by DW, SP, and KA, focusing on key issues and challenges to be considered in measuring NPA outcomes. The final list of outcomes and themes were distributed back to participants for member checking, revision, and endorsement. At the completion of data collection and analysis for this study, the focus group participants were invited to become co-authors of this paper to enable contributions from key stakeholders to reporting and dissemination of the final set of outcomes. Six of the eight focus group participants accepted that invitation.

Delphi survey

Participants

Inclusion criteria for expert panel members for the Delphi study included i) registered clinical neuropsychologists with at least 10 years of experience, who ii) had worked across a minimum of two different clinical settings, and iii) had experience working in senior positions. Participants were recruited via an Australian national email list for neuropsychologists (NPinOz). The target sample size was 20–30 participants, as per guidelines for the Delphi method where panelists have specialized expertise (Hasson et al., Reference Hasson, Keeney and McKenna2000; Hsu & Sandford, Reference Hsu and Sandford2007; Manyara et al., Reference Manyara, Purvis, Ciani, Collins and Taylor2024). All participants self-reported their age, gender, postgraduate qualifications, residence, educational, and occupational background, including years of experience as a clinical neuropsychologist, location of principal workplace (i.e., urban/rural), and their work setting (i.e., public/private) and field (i.e., pediatric, psychiatric, etc). Participants were also asked to select the three most common reasons for referrals they receive for NPA, from the following options: “Diagnostic clarification’,” “Characterisation of cognitive strengths and weaknesses,” “Guide management/treatment/rehabilitation,” “Assess decision-making capacity’,” “Assess capacity to undertake life roles (including school/study, work, driving, ADLs), and Other.”

Delphi survey content and structure

The Delphi survey was delivered electronically on the Qualtrics platform. For each outcome (“item”) identified by the focus groups, panelists were asked “How important/relevant would you rate this item as a potential outcome of neuropsychological assessment” using a 5-point Likert scale (from 1-Not at all important to 5-Very important). They were then asked to suggest existing tools to measure that outcome and for any additional comments about that item.

After completing the importance ratings, panelists then selected the top three outcomes they would include in a hypothetical RCT to investigate the outcomes of NPA. They were also asked to rate the importance of NPA feedback in achieving the outcomes identified, on a 10-point scale (from 1-Not at all important to 10-Extremely Important).

Item consensus was determined using a criterion where >80% of panelists endorsed one of the two highest ratings (4 or 5) for importance/relevance. Items which did not meet the consensus criterion and received no suggestions for improvement were removed from subsequent rounds, as it was considered that re-rating those items was unlikely to produce consensus without any revisions to the items and we wished to minimize survey burden in light of its length. Those items that received suggestions for improvement were revised and included in the next round, and explanation and justification of the revisions was provided. Items which met the consensus criterion but also received suggestions for improvement were revised as appropriate; these were included in subsequent rounds only if the revisions were substantial (again with accompanying explanation). After each round, the revised outcomes were disseminated back to the participants, with the survey including i) a list of the items that had and had not reached consensus from the previous round, ii) justifications for revisions to each item, and iii) the group-based consensus ratings (i.e., percentage of participants who selected each of the 5 responses from 1-Not at all important to 5-Very important) from the previous round. These data were anonymous, so participants did not know the identity or individual responses of the other panelists. This process continued until >80% consensus was reached on all items or there were no further suggestions for improvement on items not reaching consensus.

Data analysis

Surveys with a completion rate lower than 50% were excluded from analysis. After each survey round, frequencies of ratings at each level of the 5-point Likert scales were analyzed descriptively to determine if expert consensus was reached on each item. If the additional comments made regarding each outcome detailed issues or challenges in measuring the outcome, the content of those comments was categorized against the existing themes about measurement challenges identified from the focus groups. If new ideas were identified that did not map clearly to an existing theme, this was verified by a second researcher, and the need for an additional theme was discussed and decided collaboratively.

Results

Focus groups

Participants

A total of eight participants (7 female) aged between 32–49 years (M = 40.13, SD = 4.78) formed two focus groups (n = 4 per group). Participant experience as a clinical neuropsychologist ranged between 5–23 years (Median = 13.5 years), and varied across settings (e.g., acute, subacute, inpatient, outpatient, and community services) and client groups (e.g., acute neurology, rehabilitation, pediatric, older adult).

Analysis of potential NPA outcomes

A total of 50 outcomes of NPA were identified from the focus groups transcripts. These are presented in Table 1. There was significant overlap between individual short-term (<2 months) and long-term (≥2 months) outcomes. We decided to remove this categorization, and instead used two more distinct categories of outcomes: “Outcomes for the individual/family” and “Outcomes for the organisation/referrer.”

Table 1. Potential outcomes of neuropsychological assessment identified from the focus groups

Analysis of the issues and challenges in measuring NPA outcomes

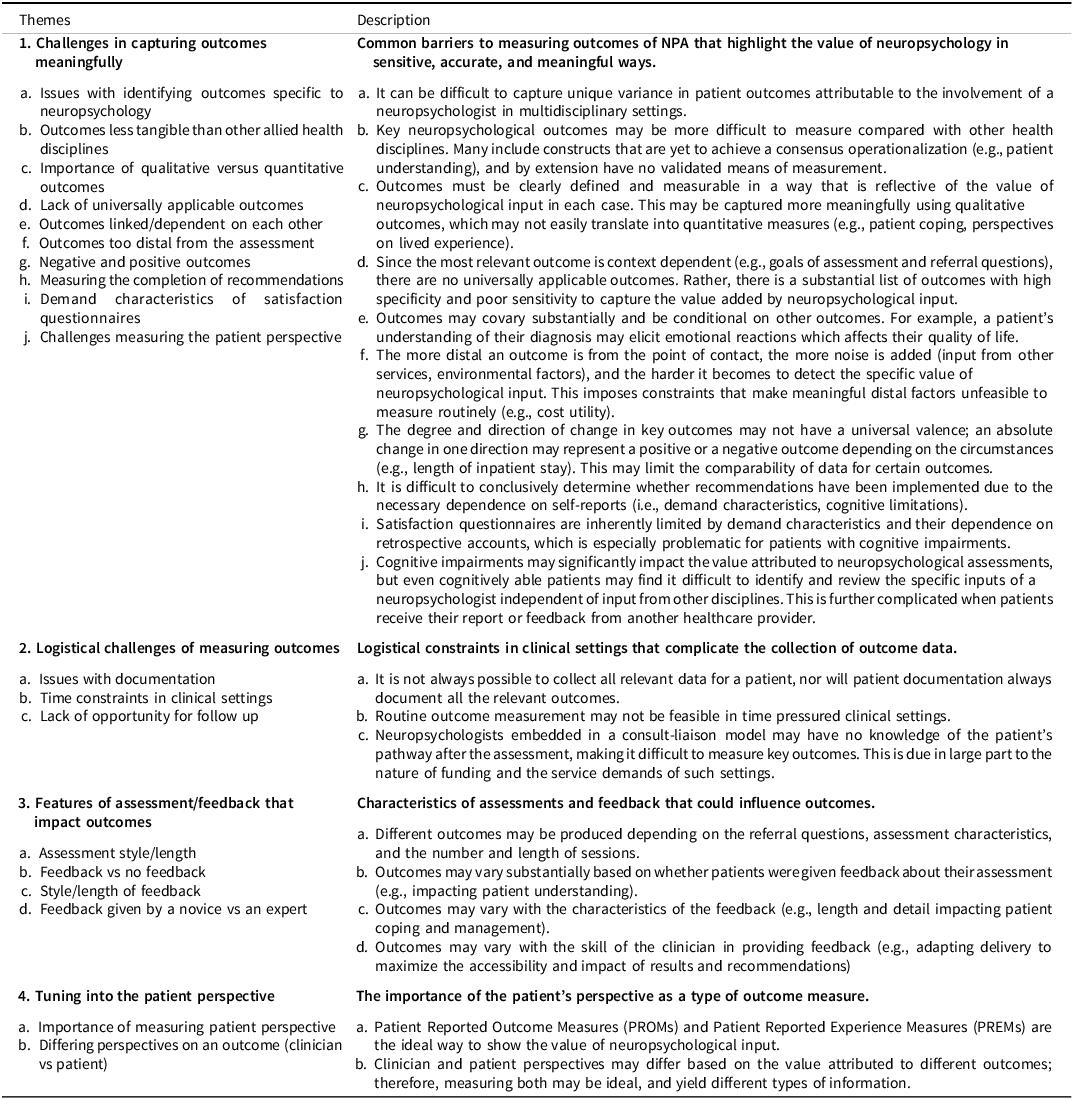

Four major themes were generated during reflexive thematic analysis: 1) Challenges in capturing outcomes meaningfully, which described barriers to measuring outcomes of NPA that highlight the value of neuropsychology in sensitive, accurate, and meaningful ways; 2) Logistical challenges of measuring outcomes, which detailed constraints in clinical settings that complicate the collection of outcome data; 3) Features of assessment/feedback that impact outcomes; and 4) Tuning into the patient perspective, which highlights the importance of patient-reported outcomes. Each theme and its subthemes are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Issues and challenges in measuring neuropsychological outcomes

Note: Themes are shown as superordinate (numerical) and subthemes as subordinate (alphabetical).

Delphi study

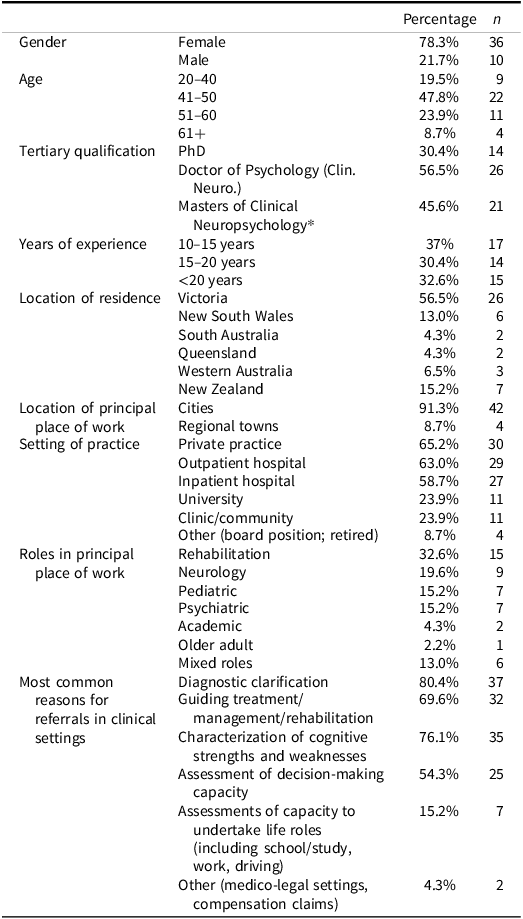

Participants

Three respondents who completed <50% of the survey were excluded. The characteristics of panelists who participated in at least the first survey round (n = 46) are presented in Table 3. Five of these participants had incomplete responses but were included as they completed more than half of the items. Twenty-seven panelists participated in Round 2 (58.7% of total sample). Participant attrition remained relatively stable between Round 2 and 3, with 25 participants (92.6%) retained from Round 2, representing 54.4% of the total sample. The remaining participants did not respond to the survey. Characteristics of participants who completed Round 2 and 3 did not differ significantly from those who withdrew after Round 1, including for gender (χ2 (1, N = 46) = .15, p = .69, φ = −.06), age (χ2 (3, N = 46) = 1.52, p = .68, V = .18) and highest qualification (χ2 (2, N = 46) = 4.94, p = .08, V = .33).

Table 3. Delphi study panellist characteristics

*Note: A Masters degree is an accredited qualification that leads to registration as a Clinical Neuropsychologist in Australia. Only 7 participants (15%) had a Masters qualification only; the remaining had also done a PhD or doctorate.

Delphi survey results: NPA outcomes

Figure 1 shows the flow of Delphi survey rounds, including the processes used in and outcomes of each round. In Round 1, four outcomes achieved consensus with no or very minimal suggestions for improvement and were retained in the final list of outcomes (shown in Table 4). Twenty-four items were removed and not included in Round 2 as they did not meet consensus criteria, and there were no suggestions for improvement. There were 22 items that were modified based on panelist feedback and consensus ratings. These modifications included wording changes to clarify meaning, merging similar items, and simplifying or splitting complex items. For example, the item “Uptake and implementation of recommended strategies/ other recommendations” was considered unclear as it was not specified whether the uptake was by the patient or referrer, so this was split into two items, one about the patient and one about the referrer, with relevant examples provided for each. One item was added based on suggestions given for two original items regarding guardianship/ administrative tribunal hearing and legal appointment of decision makers. It was suggested that the main purpose of determination of decision-making capacity was to uphold the best interests of the patient, so these items were replaced with the new outcome “Implementation of opinion about decision-making capacity so that the best interests of the patient are facilitated (i.e., patient with capacity makes their own decision, and patient lacking capacity receives assistance from a substitute decision-maker).” Following the revisions, merges, and additions, there were 18 items considered in the Round 2 survey.

Figure 1. Flow of processes and outcomes of the three Delphi survey rounds.

Table 4. Final expert consensus on outcomes of neuropsychological assessment, and existing outcome measures

Note: *Asterisked items achieved consensus prior to the inclusion of referral categories and hence were considered universal across the three referral categories, with the exception of Item 12.

Panelists frequently commented that certain outcomes were only relevant in specific contexts, and that affected their rating of its overall importance. It was therefore decided to categorize outcomes using reasons for assessment, rather than by individual/family or organization/referrer. Three categories of reasons for assessment were used, based on responses to the panelist characterization question about common reasons for NPA referral: (1) Diagnostic clarification/characterization of cognitive strengths and weaknesses, (2) Guiding treatment, management or rehabilitation/assessing capacity for life roles such as work, driving, study, and (3) Evaluating decision-making capacity. Each outcome retained in Round 2 was assigned to one or more of these assessment purposes. For example, the outcome “Access to appropriate support services/funding” was categorized under the “Guiding treatment, management or rehabilitation/assessing capacity for life roles” reason for assessment. These categorizations of outcomes were made by lead researcher DW and then verified by two experts drawn from the focus groups (KA and JW), resulting in some adjustments. Panelists were asked to rate the importance/relevance of the outcomes in relation to the applicable reason(s) for assessment. The Likert scale was modified accordingly, i.e., “As an outcome of assessments done for [insert ‘reason for assessment’], how important/relevant would you rate this item as a potential outcome of neuropsychological assessment?” Additionally, when participants were asked to rank the three most important outcomes at the end of the survey, they provided separate answers for each of the three reasons for assessment, as well as for “any reason for assessment.”

In Round 2, eight outcomes achieved consensus with no or very minimal suggestions for improvement and were retained in the final list of outcomes. Four items were removed due to lack of consensus and no suggestions for improvement. Four items were merged with other items; these merges were considered straightforward (i.e., uncontroversial), and the two resulting items were not taken forward to Round 3. There were two items that required changes to wording to clarify meaning. There were another two items which did not reach consensus for all their listed reason(s) for assessment; for those items, only the reasons for assessment which reached consensus were retained, but the outcomes themselves remained unchanged.

In Round 3, only the two outcomes with wording changes were included. Both achieved consensus. Therefore, sixteen outcomes achieved consensus after three rounds. Table 4 shows the final set of outcomes, the reason for assessment category or categories, the percentage of panelists who selected one of the top two importance ratings, and the round in which consensus was achieved. Detailed results from each survey round are provided in Supplementary Materials 1. Existing measures of each of the 16 outcomes, which were identified by panelists across the three survey rounds, are also presented in Table 4.

Analysis of survey comments: Issues and challenges in measurement

Panelist comments about the outcomes listed generally mirrored the themes identified in focus group discussions (Table 1). There were some new ideas, but it was agreed that these were extensions on existing themes rather than new themes. For example, the theme Issues with identifying outcomes specific to neuropsychology expanded to include difficulties with identifying whether outcomes were impacted specifically by NPA, or by rehabilitation that may have occurred around the same time as the NPA. Survey comments relating to the Lack of universally applicable outcomes focused more on individual outcomes which were not applicable to all settings and contexts, whereas the focus group discussion focused on the broader challenge of identifying a core set of outcomes relevant for every context.

Analysis of top three most important NPA outcomes

The outcomes most frequently selected by participants as the top three outcomes they would include in a hypothetical RCT to investigate NPA outcomes (for each of the three reasons for assessment) are shown in Figure 2. Detailed results showing the percentage of participants selecting each of these outcomes are provided in Supplementary Materials 2. As shown in the left two circles, there was significant overlap between the top three outcomes in the categories “Diagnostic clarification/characterization of cognitive strengths and weaknesses” and “Guiding treatment, management or rehabilitation/assessing capacity for life roles such as work, driving, study.” The top three outcomes for “Evaluating decision-making capacity” were independent of the other reasons for assessment, highlighting the unique nature of this referral question. Across all reasons for assessment, the top outcomes identified were:

Figure 2. Top three outcomes for each reason for assessment, as rated by panelists.

-

1. Better patient and/or caregiver understanding of presenting problems associated with diagnosis.

-

2. Better patient and/or caregiver understanding of how to manage and cope with patient’s cognitive symptoms.

-

3. Diagnostic clarification (new/excluded/changed/confirmed/more certain diagnosis).

Notably, no existing measures of the first and third of these outcomes were identified by panelists (see Table 4). There was one questionnaire suggested for the second outcome, however it was specific to understanding memory strategies for amnestic mild cognitive impairment. In response to the question about the importance of provision of verbal feedback of the NPA findings and recommendations for achieving the top three most important outcomes, mean ratings suggested that feedback is very important (M = 8.93/10, SD = 1.85, Range = 2–10).

Discussion

The aims of this study were to identify the key potential outcomes of NPA, existing tools available to measure those outcomes, and issues and challenges associated with measuring these outcomes. There were 50 potential outcomes of NPA identified by focus groups of expert neuropsychologists spanning individual, family, health service, and societal levels. Of these, 16 reached consensus after three Delphi survey rounds. Only half of these outcomes had existing measures identified, and many of those were not validated or targeted measures of the relevant specific outcome. Some outcomes such as “return to work” had more established measures identified, but these outcomes were generally distal from the NPA. This issue with linking the outcomes directly with the NPA was one of the many challenges identified by our participants in measuring NPA outcomes meaningfully and feasibly. The two outcomes rated most important for all reasons for referral to NPA were both psychoeducational outcomes in nature: Better patient and/or caregiver understanding about presenting problems associated with diagnosis and Better patient and/or caregiver understanding of how to manage and cope with cognitive symptoms. These are examples of proximal outcomes that can be causally linked with the NPA, especially when feedback is provided, and therefore likely to detect the impact of NPA for individuals with known or suspected brain conditions. Notably, no existing measures were identified that measure these outcomes directly, highlighting the need for such measures to be developed. These measures could then be used by clinicians and students to evaluate their own practice, as well as in future trials evaluating the outcomes of NPA with feedback.

The outcomes identified in this study extend on Colvin and colleagues’ (Reference Colvin, Roebuck-Spencer, Sperling, Acheson, Bailie, Espe-Pfeifer, Glen, Bragg, Bott and Hilsabeck2022) work by seeking expert consensus to produce an agreed list of the most relevant outcomes for further investigation. Most notably, and unlike Colvin’s list, the top two outcomes and many of the other outcomes that reached consensus fit within Level 1 of Fisher and colleagues’ (Reference Fisher, Zimak, Sherwood and Elias2020) framework. This level includes the most proximal outcomes to NPA, which measure the internal experiences of the person who underwent the NPA, including satisfaction with services, acquisition of knowledge, or changes in attitude. Interestingly, most of the outcomes listed by Colvin et al. (Reference Colvin, Roebuck-Spencer, Sperling, Acheson, Bailie, Espe-Pfeifer, Glen, Bragg, Bott and Hilsabeck2022) were not endorsed by panelists in our Delphi study, despite appearing on the initial list of 50 outcomes (e.g., Improved quality of life or Reduced subjective cognitive complaints). These tended to fall in Levels 2–4 of Fisher et al.’s (Reference Fisher, Zimak, Sherwood and Elias2020) framework – i.e., were more distal from the NPA and therefore potentially less sensitive to change post-NPA. These more distal outcomes were those measured by Lincoln et al. (Reference Lincoln, Dent, Harding, Weyman, Nicholl, Blumhardt and Playford2002; quality of life, mood, and subjective cognitive impairment) and McKinney et al. (Reference McKinney, Blake, Treece, Lincoln, Playfordand and Gladman2002; quality of life and psychological distress) and did not demonstrate benefit for participants who received NPA compared with cognitive screening in their RCTs, with trivial to small effect sizes. This suggests that to successfully determine the value of NPA, it may be necessary to measure the outcomes which are most proximal and directly related to the NPA, where effect sizes are likely to be larger. These patient-reported outcomes, reflecting the patient perspective, were also noted to be important by the focus groups.

One potential issue is that these proximal outcomes may hold a lower value or importance for policy makers and funders as demonstrations of the value of NPA for the patient, health system and society. One way to demonstrate these more distal effects could be to evaluate the association between improvements on proximal outcomes (including improved understanding, changes to treatment pathways, and referrer and patient satisfaction) and more distal outcomes (including implementation of recommendations made as a result of the NPA, improved quality of life, and reduced service utilization). A significant relationship between these outcome types would support the idea that the NPA can have downstream effects at these broader levels. It would also provide empirical support for Fisher and colleagues’ (Reference Fisher, Zimak, Sherwood and Elias2020) outcome classification framework, which prioritizes proximal outcomes.

The selection of outcomes to measure the value of NPA should be context dependent. The lack of universally applicable outcomes was a key issue identified in both the focus group and Delphi studies. It became clear in the Delphi study that the importance or relevance of each potential NPA outcome was difficult to evaluate without the referral context. There were different outcomes identified as most important for the three categories of reasons for assessment we used in Rounds 2 and 3, which were 1) Diagnostic clarification/ Characterization of cognitive strengths and weaknesses, 2) Guiding treatment, management or rehabilitation/Assessing capacity for life roles such as work, driving, study, and 3) Evaluating decision-making capacity. This means that future RCTs evaluating the impact of NPA should select outcomes that are most relevant to the clinical context in which NPAs are being conducted. Diagnostic clarification is the main objective of NPA in many settings, and its importance as an outcome is supported by the substantial evidence of the contribution of NPA for diagnosis of neuropsychological disorders, as reviewed by Donders (Reference Donders2020) and Watt and Crowe (Reference Watt and Crowe2018). Notably, there was substantial overlap between the most important outcomes for the first two of the assessment purposes, which suggests that similar NPA outcome measures may be used in these instances. Decision-making capacity assessments, however, had quite different important outcomes identified, and therefore should be evaluated separately.

Other outcome measurement challenges identified by our focus groups were more logistical in nature, including time constraints preventing extensive outcome measurement and the lack of opportunity for later follow-up (e.g., to check implementation of recommendations). These challenges highlight the need to identify a core outcome set that is feasible for clinicians. A clinically feasible set of outcome measures will enable monitoring of the outcomes of NPA services, which can in turn guide service quality improvements and allow clinicians and services to measure the impacts of changes they make to their model of care. These tools could add to existing, less specific quality indicators that are used to provide evidence of high quality of patient care and satisfaction, such as those required to participate in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System in the USA.

Focus group participants highlighted the issue that outcomes of NPA are likely to differ based on assessment and clinician characteristics, including provision of meaningful feedback. Delphi panelists also indicated that provision of feedback was highly important to achieve the top two most important NPA outcomes. This is consistent with previous research demonstrating neuropsychological feedback as having a positive impact on outcomes of NPA (Longley et al., Reference Longley, Tate and Brown2023; Rosado et al., Reference Rosado, Buehler, Botbol-Berman, Feigon, León, Luu, Carrión, Gonzalez, Rao, Greif, Seidenberg and Pliskin2018). We would argue that variations in the delivery of NPA do not present a challenge in outcome measurement per se, but rather that they point to the importance of measuring the impact of these variations on NPA outcomes. For example, it would be useful to understand how clinician competencies in assessment (Carrier et al., Reference Carrier, Wong, Lawrence and McKay2022), feedback (Wong, Pinto, et al., Reference Wong, Pinto, Price, Watson and McKay2023) and other related competencies (Wong, Pestell, et al., Reference Wong, Pestell, Oxenham, Stolwyk and Anderson2023) impact NPA outcomes related to patient understanding. It would also be important to examine the impact of performance validity on NPA outcomes, including patient satisfaction. Conceptualizing “NPA with feedback” as a psychoeducational intervention (see, for example, Wong, Pike, et al., Reference Wong, Pike, Stolwyk, Allott, Ponsford, McKay, Longley, Bosboom, Hodge, Kinsella and Mowszowski2023) may be helpful to guide design of clinical trials and other studies aimed at identifying “active ingredients” that optimize outcomes.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations, most relating to the generalizability of the sample. All participants in the focus groups were located and practising in Melbourne, Australia, due to the focus groups being held in person. The focus group participants are therefore not a representative sample of Australian neuropsychologists, but rather were selected on the basis of significant leadership experience and interest in outcome measurement. We note that the longlist of 50 potential outcomes generated by the focus group was open to additions and modifications by the larger and more diverse sample for the Delphi survey, who added one item and suggested changes to 22 items in Round 1.

In terms of Delphi survey participants, about half were from Victoria, and regional neuropsychologists represented only 9% of participants. A broader sample of neuropsychologists across geographical regions would offer a greater diversity of opinions on outcomes and ensure that the core outcomes are broadly applicable. Furthermore, there was a small percentage of neuropsychologists practicing in medico-legal and older adult settings. Nevertheless, there was a fair spread of participants in other settings such as rehabilitation, neurology, pediatrics, psychiatric and mixed roles, and the top outcomes that were identified could be considered relevant across these settings. The high proportion of female panelists is representative of neuropsychologists’ demographics in Australia, but this may differ in other countries. Female psychologists can be more likely to view their clients positively (Artkoski & Saarnio, Reference Artkoski and Saarnio2013), and therefore may have prioritized patient-reported outcomes more than their male counterparts.

Relatedly, we note here that the conclusions that were drawn by our Australian panelists may differ from those that would have been drawn by panelists in other countries. We chose to focus on a single country first to aim for consensus in the context of Australia’s health and disability systems and the most common roles that neuropsychologists perform within those systems. However, it will be important to conduct similar research around the world with the aim of reaching international consensus. Based on key similarities identified in neuropsychology training and competency frameworks (e.g., Hessen et al., Reference Hessen, Hokkanen, Ponsford, van Zandvoort, Watts, Evans and Haaland2018) and practices (Kasten et al., Reference Kasten, Barbosa, Kosmidis, Persson, Constantinou, Baker, Lettner, Hokkanen, Ponchel, Mondini, Jonsdottir, Varako, Nikolai, Pranckeviciene, Harper and Hessen2021) around the world, we would predict that similar conclusions would be drawn by international panels. This is supported by the fact that the outcomes identified are consistent with frameworks developed outside Australia (e.g., Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Zimak, Sherwood and Elias2020), suggesting they are globally relevant. However, it is possible that cultural differences (e.g., in the views of people from collectivist versus individualistic cultures) may impact selection of the most important outcomes and associated measurement tools. Additionally, differences in service contexts in some countries (e.g., the higher likelihood of cases seen for NPA ending up in civil litigation in the USA) may influence experts’ perspectives regarding important outcomes in those countries. It is also possible that countries requiring doctorate-level qualifications for registration as a clinical neuropsychologist may prioritize different outcomes, reflecting more extensive research training (though we note that 85% of our sample had a doctoral-level qualification).

In addition, we focused on the perspectives of neuropsychologists as the experts in this study. It would be interesting and valuable to investigate the key NPA outcomes considered most important by i) referrers to and ii) users of NPA services. Although we are not aware of any Delphi or studies using consensus-based approaches with these cohorts, referrers to neuropsychologists in private practice in Australia were surveyed by Allahham and colleagues (Reference Allahham, Wong and Pike2023). When asked to rate how frequently certain outcomes occurred as a result of the NPA, referrers rated “diagnostic clarification” as the most frequent. When asked how beneficial certain outcomes were for patients and families, referrers rated “understanding cognitive strengths and weaknesses”, “understanding causes” and “understanding how to cope/manage” as the most beneficial outcomes. These findings align closely with the results of our Delphi study. However, we are yet to investigate how close the alignment is with those who have undergone NPA and their families and close others.

There was a fairly high attrition rate between Round 1 and 2, possibly due to survey burden. The total number of panelists in Rounds 2 and 3 still fell within the suggested sample size of 20–30 for Delphi surveys (Hasson et al., Reference Hasson, Keeney and McKenna2000; Manyara et al., Reference Manyara, Purvis, Ciani, Collins and Taylor2024), however the attrition further limits the generalizability of the sample and our findings. Those who were retained in Round 2 and 3 may have been those with stronger views about the outcomes, though notably, there were no demographic differences in the samples for each round. However, as most of the culling of outcomes occurred in Round 1, with Rounds 2 and 3 focused on smaller refinements, it is unlikely that the final core outcomes would have differed significantly if participant retention was higher.

The importance ratings in Round 2 and 3 were made with reference to the three broad categories of reasons for assessment. It is possible that consensus was not reached in Round 1 for some outcomes due to the lack of a specific context in which they were being considered, and that if participants were provided with another opportunity to re-rate the items that did not reach consensus in Round 1 in relation to the specific referral reasons in Round 2, some may have subsequently reached consensus. Additionally, if personalized feedback was provided (i.e., showing each individual’s response in the previous round in addition to the group-based percentages), it is possible that consensus may have been reached on more items. However, it is unlikely to have changed the top three rated outcomes, which were selected by a clear majority. Some of the outcomes that did not reach consensus (e.g., Improved quality of life; Cost savings to the organization/health service) may still be relevant to measure in certain contexts or to answer specific research questions. We note that the Delphi survey was framed as identifying key outcomes that are likely to detect the value and impact of NPA in RCTs. Therefore, some of the distal outcomes that may be considered important in a general sense but not as sensitive to change post-NPA, or relevant for as many contexts, are likely to have been rated less favorably by panelists. It is also possible that the use of only three broad categories of reasons for assessment (which was a decision made to minimize survey burden) was not nuanced enough, and a larger selection of referral reasons may improve the specificity of outcomes to different practice settings.

Conclusions and future directions

The key potential outcomes of NPA identified in this study provide a roadmap for measuring the impacts of NPA for patients, caregivers, referrers, health services and society. The most important next step in this program of research (and being pursued by our team) is to develop and validate tools to measure the core outcomes identified, particularly the top two outcomes focused on patient understanding of their condition and its management. As noted in the focus groups, the construct of “patient understanding of presenting problems” does not yet have a clear operationalization, and therefore no current validated means of measurement. The development of a tool will therefore need to be based on a clear conceptualization of patient understanding, based on theory and consensus, as well as being feasible to deliver in busy clinical settings. Having sensitive, tailored measures of these proximal outcomes of NPA will enable meaningful measurement of NPA outcomes in RCTs (e.g., comparing NPA with a brief cognitive screening control condition, whereby the control group receives NPA at the end of the trial; see Feast et al., under review; trial protocol registered on the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry: ACTRN12625000004460), as well as service evaluations and quality improvement studies. Such trials are crucial for our profession, to enable us to clearly and rigorously demonstrate to funders and policy makers the value that NPA can add to healthcare for people with brain conditions, and optimize provision of accessible, affordable neuropsychological services.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617725101793

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all Delphi survey participants for your insightful contributions to this research.

Funding statement

No funding support was received for this study.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.