1. Introduction

Most people are inclined to deny Derek Parfit’s

Repugnant Conclusion For any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better, even though its members have lives that are barely worth living (Parfit Reference Parfit1984: 388).

Doing so in a plausible way, however, has turned out to be rather difficult. Some of the difficulties have been evident from the beginning: along with the statement of the Repugnant Conclusion, Parfit provided his celebrated Mere Addition Paradox.Footnote 1 Since then, philosophers and economists have contributed yet stronger arguments and impossibility theorems, revealing the problem of avoiding the Repugnant Conclusion to be even harder than Parfit first thought.Footnote 2 In this paper, I provide another argument in this vein. For ease of reference, let’s call it the Additive Impossibility Result.

Parfit’s Mere Addition Paradox relies heavily on the Mere Addition Principle, which says that additions of good lives to the world cannot make an outcome worse. This principle is plausible, but questionable. The main point of the Additive Impossibility Result is to do without it and its close cousins, such as the “Weak Non-Sadism Condition” appearing in Gustaf Arrhenius’s favoured Sixth Impossibility Theorem. That condition says that additions of good lives (no matter how many) cannot make an outcome worse than adding a large number of very bad lives.Footnote 3

Instead, the Additive Impossibility Result appeals to what I call the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition. This principle is non-additive in the following sense: while the Weak Non-Sadism Condition holds that adding a large number of bad lives to any unaffected background population always results in a worse outcome than adding any number of lives worth living, the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition only requires that a large population of bad lives would be worse by itself than any number of lives (perhaps barely) worth living.

Arrhenius’s Sixth Theorem uses the additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition to derive a non-additive version of the Repugnant Conclusion.Footnote 4 The Additive Impossibility Result switches this around. It uses the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition to derive an additive version of the Repugnant Conclusion, which says (simplifying things a little) that adding a large number of people with lives barely worth living can be better than adding a smaller number of people with a very high quality of life.Footnote 5

This switch has a philosophical payoff. As I shall argue in

![]() ${\rm{\S}}$

2, Weak Non-Sadism might fail if we take seriously the idea that additions of good lives can make an otherwise excellent population much worse: that is, that the Mere Addition Principle is false in such a way that, by rejecting it, we can avoid the original Mere Addition Paradox. (Of course, one might just take this to illustrate the high cost of denying the Mere Addition Principle.) Weak Non-Sadism is compelling, but the improvement it offers over the Mere Addition Principle is, I shall suggest, smaller than it first seems.

${\rm{\S}}$

2, Weak Non-Sadism might fail if we take seriously the idea that additions of good lives can make an otherwise excellent population much worse: that is, that the Mere Addition Principle is false in such a way that, by rejecting it, we can avoid the original Mere Addition Paradox. (Of course, one might just take this to illustrate the high cost of denying the Mere Addition Principle.) Weak Non-Sadism is compelling, but the improvement it offers over the Mere Addition Principle is, I shall suggest, smaller than it first seems.

In contrast, the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition is compelling regardless of whether the Mere Addition Principle is true. Moreover, it is more plausible than avoidance of the additive version of the Repugnant Conclusion. Yet the additive version of the Repugnant Conclusion still seems “repugnant” in the same sort of way as the non-additive version. Consider a future for humanity in which our descendants live excellent lives, contrasted with a drab future in which a much larger population has lives barely worth living. It is “repugnant” for the drab future to be better. Suppose now that regardless of which future we choose, some (perhaps large) number of alien persons will also come to exist in a causally isolated part of the universe. Does the presence of these aliens change our intuition that the “drab future” would be worse? I think not. If the drab future is better overall, given certain facts about the numbers and wellbeing levels of the unaffected aliens, this is an instance of the “additive” Repugnant Conclusion.

The Additive Impossibility Result therefore answers the question of whether a reasonable solution to the problem of avoiding the Repugnant Conclusion can be confined to the variable-population case. The answer is: No. If the Repugnant Conclusion is to be avoided in a reasonable way, one must either reject certain plausible principles for comparing same-person populations, or reject foundational structural assumptions such as Acyclicity or what I shall call “Finite Fine-Grainedness”.

2. Mere Addition and Non-Sadism

Let us begin by recalling Parfit’s Mere Addition Paradox (Reference Parfit1984: Ch. 19). The principle at its centre is, unsurprisingly, the

Mere Addition Principle If

![]() $X$

is a population, and

$X$

is a population, and

![]() $Y$

is a population consisting solely of good lives, then

$Y$

is a population consisting solely of good lives, then

![]() $X + Y$

is not worse than

$X + Y$

is not worse than

![]() $X$

.

$X$

.

The argument runs as follows. We begin with an arbitrary population

![]() $A$

, consisting of many excellent lives. We then add an extremely large number of lives barely worth living to

$A$

, consisting of many excellent lives. We then add an extremely large number of lives barely worth living to

![]() $A$

; call the resulting population

$A$

; call the resulting population

![]() ${A^ + }$

. By the Mere Addition Principle,

${A^ + }$

. By the Mere Addition Principle,

![]() ${A^ + }$

is not worse than

${A^ + }$

is not worse than

![]() $A$

. By repeatedly applying plausible principles for comparing same-person populations, we find that

$A$

. By repeatedly applying plausible principles for comparing same-person populations, we find that

![]() ${A^ + }$

is worse than some population

${A^ + }$

is worse than some population

![]() $Z$

, in which all of the

$Z$

, in which all of the

![]() ${A^ + }$

people have a life which is barely worth living, and just a little better than the additional lives in

${A^ + }$

people have a life which is barely worth living, and just a little better than the additional lives in

![]() ${A^ + }$

. (The gains to the

${A^ + }$

. (The gains to the

![]() $A$

people in population

$A$

people in population

![]() ${A^ + }$

are outweighed by the losses to the remaining people.) By transitivity,

${A^ + }$

are outweighed by the losses to the remaining people.) By transitivity,

![]() $Z$

is not worse than

$Z$

is not worse than

![]() $A$

. This is a version of the Repugnant Conclusion.

$A$

. This is a version of the Repugnant Conclusion.

How should we respond to the Mere Addition Paradox? One attractive option is to simply deny the Mere Addition Principle. While it seems implausible that additions of good lives could make the world worse, we might find the Repugnant Conclusion still more implausible. One significant advantage to this response to the Mere Addition Paradox is that it confines our population-ethical difficulties to variable-population cases.Footnote 6

To be sure, it is hard to see why the Mere Addition Principle should be false. But perhaps some explanation could be offered. One might, for instance, appeal to the badness of inequality in order to argue that

![]() ${A^ + }$

is worse than

${A^ + }$

is worse than

![]() $A$

. Or perhaps we could say that the move from

$A$

. Or perhaps we could say that the move from

![]() $A$

to

$A$

to

![]() ${A^ + }$

makes things worse in a holistic sense, as we would move from a situation in which everyone has an excellent life to one in which almost everyone has a life barely worth living. While it is difficult to account for judgements like these in person-affecting terms (since a mere addition isn’t bad for anyone), intrapersonal arguments for the Repugnant Conclusion provide another line of evidence that we might need to appeal to impersonal considerations to avoid the Repugnant Conclusion.Footnote

7

${A^ + }$

makes things worse in a holistic sense, as we would move from a situation in which everyone has an excellent life to one in which almost everyone has a life barely worth living. While it is difficult to account for judgements like these in person-affecting terms (since a mere addition isn’t bad for anyone), intrapersonal arguments for the Repugnant Conclusion provide another line of evidence that we might need to appeal to impersonal considerations to avoid the Repugnant Conclusion.Footnote

7

Later impossibility theorems are widely thought to close the door on the possibility of escaping the Repugnant Conclusion by denying the Mere Addition Principle. In particular, Gustaf Arrhenius has shown that the Mere Addition Principle can be replaced by other, supposedly more compelling, different-number principles. These are

Dominance Addition If

![]() $A$

is a population, and

$A$

is a population, and

![]() $B$

is a population consisting only of good lives, and

$B$

is a population consisting only of good lives, and

![]() ${A^ + }$

consists of the

${A^ + }$

consists of the

![]() $A$

-people with higher wellbeing levels than they enjoy in

$A$

-people with higher wellbeing levels than they enjoy in

![]() $A$

, then

$A$

, then

Non-Sadism If

![]() $A$

is a population consisting of good lives, and

$A$

is a population consisting of good lives, and

![]() $B$

is a population consisting of bad lives, then for any unaffected background population

$B$

is a population consisting of bad lives, then for any unaffected background population

![]() $I$

,

$I$

,

Weak Non-Sadism There is some bad wellbeing level

![]() $b$

, and some number of lives at this level, such that if

$b$

, and some number of lives at this level, such that if

![]() $B$

is a population consisting of at least this number of lives at level

$B$

is a population consisting of at least this number of lives at level

![]() $b$

, or at some worse level, and

$b$

, or at some worse level, and

![]() $A$

is any population consisting of good lives, and

$A$

is any population consisting of good lives, and

![]() $I$

is any unaffected background population, then

$I$

is any unaffected background population, then

However, these conditions are not particularly compelling conditional on the Mere Addition Principle being false in the way it would need to be for us to avoid the Mere Addition Paradox. Consider first the principle of Dominance Addition. This says that adding good lives while at the same time making existing people better off results in an outcome which is at least as good. But if Mere Addition is false, adding good lives can be bad. While it is clearly a good thing for existing people to be better off, there is no obvious reason to expect that the good thing must always outweigh the bad thing. There is thus no real reason to expect that it cannot be worse for existing people to be made better off, and additional good lives to be added at the same time. This claim is plausible, but only because the Mere Addition Principle is plausible. Dominance Addition is plausible because adding good lives does not appear to be bad.

The same point applies to Non-Sadism. Although it would clearly be a bad thing for an additional bad life to be added to a population, there is not much reason to expect that this must always be worse than an addition of good lives, if we think that an addition of good lives can also be a bad thing.Footnote 8 Again: Non-Sadism is plausible because adding good lives does not appear to be bad (that is: it is plausible because the Mere Addition Principle seems to be true).

Consider finally the Weak Non-Sadism condition. This principle seems more compelling than Non-Sadism because even if adding good lives could be bad, surely it could not be so bad as to be worse than an addition of a large number of very bad lives. The problem here, however, is that if we get out of the Mere Addition Paradox by denying the Mere Addition Principle, we must think that adding good lives can be very bad indeed, in the right circumstances.

To see this, let

![]() $B$

be some population which is so bad that, by Weak Non-Sadism, adding it is worse than adding any population of good lives. We can choose, on the basis of

$B$

be some population which is so bad that, by Weak Non-Sadism, adding it is worse than adding any population of good lives. We can choose, on the basis of

![]() $B$

, a population

$B$

, a population

![]() $A$

in which every person is many times better off than the people in

$A$

in which every person is many times better off than the people in

![]() $B$

are badly off, and which contains vastly more people. Those who wish to deny Mere Addition to avoid the Repugnant Conclusion will think that adding a suitably large population of barely good lives

$B$

are badly off, and which contains vastly more people. Those who wish to deny Mere Addition to avoid the Repugnant Conclusion will think that adding a suitably large population of barely good lives

![]() ${Z^ - }$

to

${Z^ - }$

to

![]() $A$

can render the latter population worse than

$A$

can render the latter population worse than

![]() $Z$

, a population consisting of lives barely worth living. But is it obvious that

$Z$

, a population consisting of lives barely worth living. But is it obvious that

![]() $A + B$

is likewise worse than

$A + B$

is likewise worse than

![]() $Z$

? It is not. While it would be a tragedy for the

$Z$

? It is not. While it would be a tragedy for the

![]() $B$

lives to exist, there could be trillions of excellent

$B$

lives to exist, there could be trillions of excellent

![]() $A$

lives for every

$A$

lives for every

![]() $B$

life. Such a population might plausibly be better (or at least not worse) than any population consisting only of lives barely worth living. If that is right, then, by transitivity,

$B$

life. Such a population might plausibly be better (or at least not worse) than any population consisting only of lives barely worth living. If that is right, then, by transitivity,

![]() $A + B$

must not be worse than

$A + B$

must not be worse than

![]() $A + {Z^ - }$

. And this is exactly what it takes for Weak Non-Sadism to be false.

$A + {Z^ - }$

. And this is exactly what it takes for Weak Non-Sadism to be false.

The lesson to draw here is that the plausibility of the Dominance, Non-Sadism and Weak Non-Sadism conditions is closely tied to the plausibility of the Mere Addition Principle itself. The impossibility theorems involving these conditions bring out the costs of this way of avoiding the Repugnant Conclusion, but they do not show that it is unacceptable. To close off this route completely, one would need to provide an impossibility theorem which replaces the Mere Addition Principle with a principle which remains compelling even on the assumption that the Mere Addition Principle is false. Ideally, this replacement should also be clearly more plausible than avoidance of the Repugnant Conclusion. This can indeed be done, as we shall now see.

3. The Additive Impossibility Result

3.1 Framework: Wellbeing and Populations

We assume that there are infinitely many possible people, and that we have at our disposal some set of wellbeing levels.Footnote

9

A population is any logically possible assignment of finitely many people to wellbeing levels. If

![]() $X$

is a set of possible persons (hereafter a “group”)

$X$

is a set of possible persons (hereafter a “group”)

![]() $X\left[ w \right]$

denotes the population where the

$X\left[ w \right]$

denotes the population where the

![]() $X$

people exist at wellbeing level

$X$

people exist at wellbeing level

![]() $w$

and nobody else exists. When populations (or groups)

$w$

and nobody else exists. When populations (or groups)

![]() $X$

and

$X$

and

![]() $Y$

are disjoint,

$Y$

are disjoint,

![]() $X + Y$

denotes their set theoretic union: the population (group) consisting of the

$X + Y$

denotes their set theoretic union: the population (group) consisting of the

![]() $X$

people and

$X$

people and

![]() $Y$

people, who are (in the case of populations) at their respective wellbeing levels in

$Y$

people, who are (in the case of populations) at their respective wellbeing levels in

![]() $X$

and

$X$

and

![]() $Y$

.Footnote

10

An option set is any finite non-empty set of populations; let

$Y$

.Footnote

10

An option set is any finite non-empty set of populations; let

![]() ${\cal C}$

be the set of all option sets. A population axiology

${\cal C}$

be the set of all option sets. A population axiology

![]() $\succeq$

is a three-place relation on

$\succeq$

is a three-place relation on

![]() $P \times P \times {\cal C}$

, where

$P \times P \times {\cal C}$

, where

![]() $P$

is the set of all possible populations, and

$P$

is the set of all possible populations, and

![]() $\succeq$

is reflexive in the sense that we have

$\succeq$

is reflexive in the sense that we have

![]() $\succeq \left( {X,X,C} \right)$

for any population

$\succeq \left( {X,X,C} \right)$

for any population

![]() $X$

and any option set

$X$

and any option set

![]() $C$

. Other relations, such as

$C$

. Other relations, such as

![]() $\succ, $

and

$\succ, $

and

![]() $ \prec $

, are defined from

$ \prec $

, are defined from

![]() $\succeq$

in the standard way. I shall often use “at-least-as-good-as”, “better” and so on to refer to a population axiology and its derived relations.

$\succeq$

in the standard way. I shall often use “at-least-as-good-as”, “better” and so on to refer to a population axiology and its derived relations.

We will need to make some fairly minimal assumptions about the structure of wellbeing. We will need to assume the existence of a prudential at-least-as-good-as relation on wellbeing levels. I shall denote this relation by

![]() $ \ge $

, with other symbols standing for derived relations in the obvious way, and “betterness” talk referring to the relevant derived relations. The relation

$ \ge $

, with other symbols standing for derived relations in the obvious way, and “betterness” talk referring to the relevant derived relations. The relation

![]() $ \ge $

is assumed to be transitive and reflexive.Footnote

11

For technical reasons, we need to assume the Directedness Property: for any wellbeing levels

$ \ge $

is assumed to be transitive and reflexive.Footnote

11

For technical reasons, we need to assume the Directedness Property: for any wellbeing levels

![]() ${w_1}$

and

${w_1}$

and

![]() ${w_2}$

, there exists some

${w_2}$

, there exists some

![]() ${w_3}$

such that

${w_3}$

such that

![]() ${w_3} \ge {w_1},{w_2}$

and some

${w_3} \ge {w_1},{w_2}$

and some

![]() ${w_4}$

such that

${w_4}$

such that

![]() ${w_4} \le {w_1},{w_2}$

.Footnote

12

The Directedness Property is weaker and less controversial than the completeness requirement (which we shall not assume), according to which for any wellbeing levels and

${w_4} \le {w_1},{w_2}$

.Footnote

12

The Directedness Property is weaker and less controversial than the completeness requirement (which we shall not assume), according to which for any wellbeing levels and

![]() $w{\rm{'}}$

, either

$w{\rm{'}}$

, either

![]() $w \ge w{\rm{'}}$

or

$w \ge w{\rm{'}}$

or

![]() $w \le w{\rm{'}}$

.

$w \le w{\rm{'}}$

.

We shall assume that lives and wellbeing levels can be categorized as being good or as bad. These correspond to the levels of a life worth living and of a life worth not living respectively. Good lives are better than bad ones. A neutral life (or wellbeing level) is one which is neither good nor bad.Footnote 13 A barely good life is one at a wellbeing level which is good, and which is close to not being good.

3.2 Finite Fine-Grainedness

We shall take “closeness” to be a primitive binary relation on wellbeing levels. Its intended interpretation is exactly what it sounds like: two wellbeing levels are “close” if they are close together, on some appropriate specification of this notion. For instance, we might say that

![]() $w$

and

$w$

and

![]() $w{\rm{'}}$

are close if the addition or omission of a few pinpricks of pain can make the difference between

$w{\rm{'}}$

are close if the addition or omission of a few pinpricks of pain can make the difference between

![]() $w$

being better or worse than

$w$

being better or worse than

![]() $w{\rm{'}}$

. The notion of closeness is crucial to our first assumption about the structure of wellbeing, namely

$w{\rm{'}}$

. The notion of closeness is crucial to our first assumption about the structure of wellbeing, namely

Finite Fine-Grainedness For any wellbeing levels

![]() $w \gt u$

, there exists a finite chain of wellbeing levels

$w \gt u$

, there exists a finite chain of wellbeing levels

![]() $w = {w_0} \gt {w_1} \gt \ldots \gt {w_n} = u$

such that each

$w = {w_0} \gt {w_1} \gt \ldots \gt {w_n} = u$

such that each

![]() ${w_i}$

is close to

${w_i}$

is close to

![]() ${w_{i + 1}}$

.

${w_{i + 1}}$

.

Thomas (Reference Thomas2018) argues convincingly that Finite Fine-Grainedness is not a principle which is automatically true of the structure of wellbeing. Pace Arrhenius (Reference Arrhenius, Johansson, Österberg and Sliwinski2009, Reference Arrhenius, Dzhafarov and Perry2011), mathematical models purporting to represent the structure of wellbeing can violate Finite Fine-Grainedness. But mathematical possibility is one thing, and philosophical plausibility is another. It seems to me that no such model succeeds in faithfully representing the structure of wellbeing.

Here’s why.Footnote

14

Suppose that we take any life, and either make an existing second of it slightly more painful, or extend the life by a second. Both modifications result in only a small difference in wellbeing. Yet sufficiently many such modifications can turn any arbitrarily good life into an arbitrarily long life of constant, agonizing torture. Given, as seems plausible, that any finite life is better than a sufficiently long life of agonizing torture, for any lives

![]() $w \gt u$

we can find a finite consecutively close chain from

$w \gt u$

we can find a finite consecutively close chain from

![]() $w$

towards some life

$w$

towards some life

![]() ${w_n}$

which is worse than

${w_n}$

which is worse than

![]() $u$

. This argument, if it succeeds, justifies Finite Fine-Grainedness.Footnote

15

$u$

. This argument, if it succeeds, justifies Finite Fine-Grainedness.Footnote

15

One might resist arguments of this sort.Footnote

16

Erik Carlson (Reference Carlson, Arrhenius, Bykvist, Campbell and Finneron-Burns2022: 215–216) suggests that small additions of pain might correspond to large differences in wellbeing. He argues that adding or worsening pain episodes might bring about a threshold or holistic effect, whereby a slight amount of added pain corresponds to a sharp drop in wellbeing. I can see two reasons why this might be the case. First, certain levels of pain might be incompatible with certain important goods. A small increase in pain may therefore remove such goods from a person’s life, thereby indirectly leading to a large loss of wellbeing. Second, the badness of pain itself may increase in a greater-than-linear fashion, so that

![]() $n$

pain episodes may sometimes be more than

$n$

pain episodes may sometimes be more than

![]() $n$

times as bad as a single episode.Footnote

17

$n$

times as bad as a single episode.Footnote

17

I am inclined to think, however, that neither of these considerations should lead us to reject Finite Fine-Grainedness.Footnote 18 While it strikes me as plausible that it is not possible for a person to enjoy certain important goods like knowledge or friendship during a sufficiently intense episode of pain, I doubt that these goods disappear in a discontinuous rather than continuous way. If agonizing pain is distracting enough to completely overpower one’s capacity to enjoy the good of friendship, then surely slightly-less-agonizing pain will mostly overpower it. Similarly, while the badness of pain might increase in a greater-than-linear fashion, it is implausible that it should increase in a discontinuous fashion. Sixty-four seconds of pain at intensity sixty-four could not plausibly be twice as bad, let alone a million times as bad, as sixty-three seconds of pain at intensity sixty-three.

It is also worth noting that the validity of the Additive Impossibility Result will not depend on the interpretation of the “closeness” relation. While “closeness”, on my intended interpretation, is a relation which holds between two wellbeing levels when they are evaluatively very similar, we might instead interpret “closeness” as a relation which holds between two wellbeing levels just in case it intuitively seems that one is not lexically superior to the other. The General Non-Elitism and General Non-Extreme Priority conditions we shall discuss later derive some of their intuitive force from the former, intended, interpretation of “closeness”. But they may still be defensible on the latter, less stringent, interpretation of “closeness”. Finite Fine-Grainedness, on the other hand, will be much harder to deny on this lax interpretation of “closeness”. Yet the Additive Impossibility Result will hold however we interpret “closeness”, provided we interpret it the same way for each premise.

3.3 Option-Set-Dependence and Acyclicity

Let us say that

![]() $A$

is sequentially worse than

$A$

is sequentially worse than

![]() $B$

, which we denote by

$B$

, which we denote by

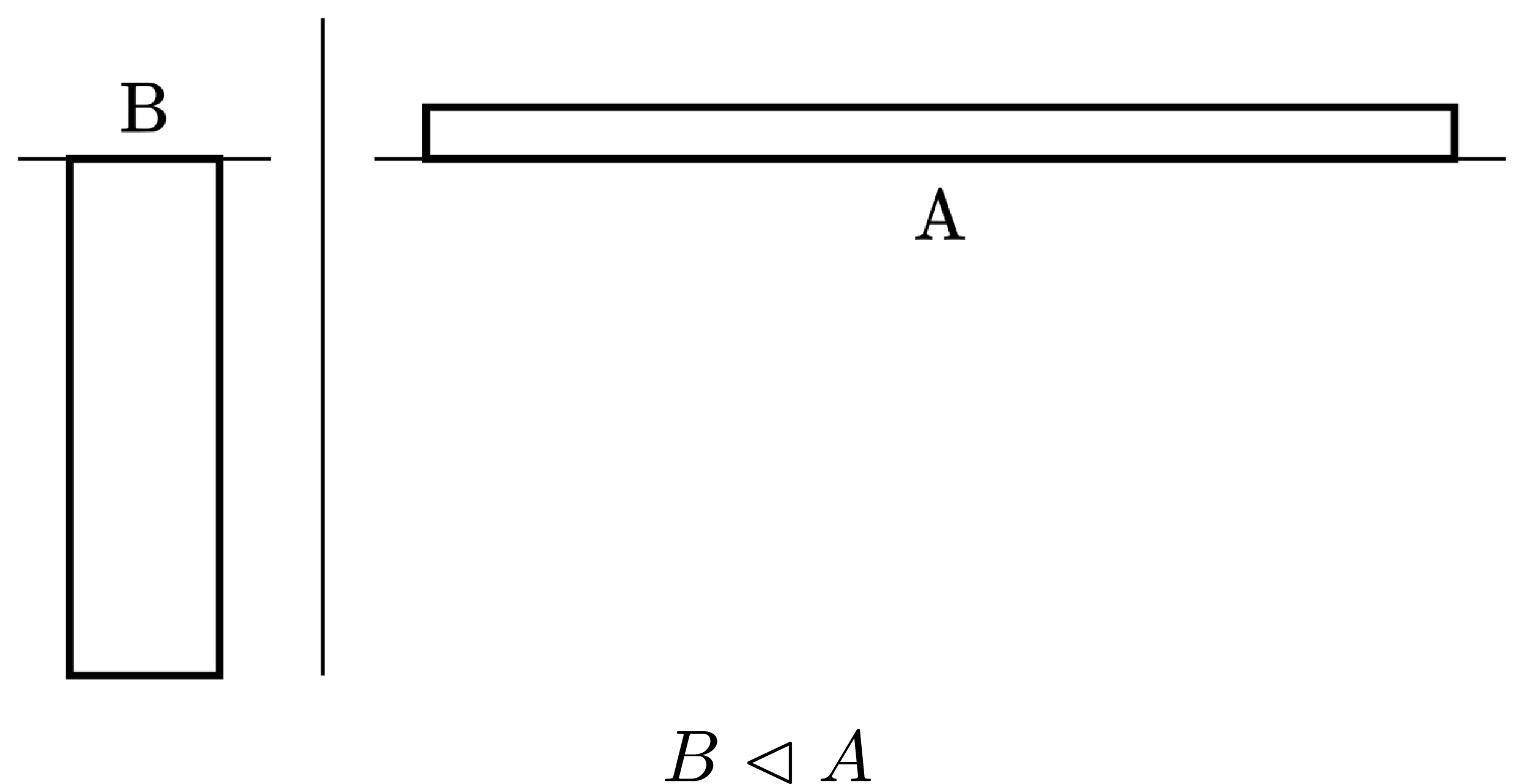

![]() $A \triangleleft B$

, if and only if there exists some sequence with at least two members

$A \triangleleft B$

, if and only if there exists some sequence with at least two members

![]() ${A_1},{A_2}, . . ., {A_n}$

, with

${A_1},{A_2}, . . ., {A_n}$

, with

![]() ${A_1} = A$

and

${A_1} = A$

and

![]() ${A_n} = B$

, such that for all

${A_n} = B$

, such that for all

![]() $i \lt n$

,

$i \lt n$

,

![]() ${A_i} \prec {A_{i + 1}}$

in every option set containing

${A_i} \prec {A_{i + 1}}$

in every option set containing

![]() ${A_i}$

and

${A_i}$

and

![]() ${A_{i + 1}}$

. Given transitivity, sequential worseness is equivalent to strict worseness in all option sets. Since we are not assuming transitivity, sequential worseness is a logically weaker notion than strict worseness in all option sets. We shall use it as a substitute for strict worseness. There are two reasons to appeal to sequential worseness. First, sequential worseness comparisons can be made without the need to worry about option set dependence. Second, and more importantly, the sequential worseness relation is automatically transitive, even if the ordinary worseness relation is not. That is, we have the

${A_{i + 1}}$

. Given transitivity, sequential worseness is equivalent to strict worseness in all option sets. Since we are not assuming transitivity, sequential worseness is a logically weaker notion than strict worseness in all option sets. We shall use it as a substitute for strict worseness. There are two reasons to appeal to sequential worseness. First, sequential worseness comparisons can be made without the need to worry about option set dependence. Second, and more importantly, the sequential worseness relation is automatically transitive, even if the ordinary worseness relation is not. That is, we have the

Transitivity Lemma Let

![]() $X$

,

$X$

,

![]() $Y$

and

$Y$

and

![]() $Z$

be any populations. Suppose

$Z$

be any populations. Suppose

![]() $X \triangleleft Y$

and

$X \triangleleft Y$

and

![]() $Y \triangleleft Z$

. Then

$Y \triangleleft Z$

. Then

![]() $X \triangleleft Z$

. A proof of this fact may be found in the Appendix.

$X \triangleleft Z$

. A proof of this fact may be found in the Appendix.

The premises of the Additive Impossibility Result will be stated in terms of the sequential worseness relation. Since this relation is a little artificial, this could make it difficult to determine how plausible these premises are. It is therefore worth keeping in mind that the relation of being worse in all option sets is logically weaker than sequential worseness. This is because, if

![]() $X$

is worse than

$X$

is worse than

![]() $Y$

in all option sets, then there is a sequence, namely

$Y$

in all option sets, then there is a sequence, namely

![]() $X,Y$

, such that each member of the sequence is worse than its successor (if it has one) in all option sets containing the two. We can therefore imagine the premises of the Additive Impossibility Result (except for Acyclicity) as being stated in terms of the “worseness in all option sets” relation, rather than in terms of sequential worseness. As these reinterpreted premises would be logically stronger, imagining them in this way will not make them seem more plausible than they are. The reason I have stated the premises in terms of sequential worseness rather than worseness in all option sets is simply that this simplifies the proofs, as it allows us to appeal to the Transitivity Lemma.

$X,Y$

, such that each member of the sequence is worse than its successor (if it has one) in all option sets containing the two. We can therefore imagine the premises of the Additive Impossibility Result (except for Acyclicity) as being stated in terms of the “worseness in all option sets” relation, rather than in terms of sequential worseness. As these reinterpreted premises would be logically stronger, imagining them in this way will not make them seem more plausible than they are. The reason I have stated the premises in terms of sequential worseness rather than worseness in all option sets is simply that this simplifies the proofs, as it allows us to appeal to the Transitivity Lemma.

Those qualifications aside, the sequential worseness notation allows us to easily state our second structural premise. This will be an acyclicity condition which we shall use in place of transitivity:

Acyclicity For every population

![]() $X$

, it is not the case that

$X$

, it is not the case that

![]() $X \triangleleft X$

.

$X \triangleleft X$

.

3.4 Premises

The Additive Impossibility Result has four non-structural premises. Our avoidance condition for the Repugnant Conclusion shall be the

Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition For any barely good wellbeing level

![]() $z$

, there exists some good wellbeing level

$z$

, there exists some good wellbeing level

![]() $a \gt z$

and bad wellbeing level

$a \gt z$

and bad wellbeing level

![]() $b{\rm{'}} \lt z$

, and numbers of lives

$b{\rm{'}} \lt z$

, and numbers of lives

![]() $n$

and

$n$

and

![]() $m$

, such that for any groups

$m$

, such that for any groups

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() $B$

consisting of

$B$

consisting of

![]() $n$

and at least

$n$

and at least

![]() $m$

lives respectively, any group

$m$

lives respectively, any group

![]() $Z$

, any unaffected background population

$Z$

, any unaffected background population

![]() $I$

, and any bad level

$I$

, and any bad level

![]() $b \le b{\rm{'}}$

,

$b \le b{\rm{'}}$

,

The Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition, illustrated by Figure 1, requires that an

![]() $A$

-population must always make a better addition than a

$A$

-population must always make a better addition than a

![]() $Z$

-population, but only when some arbitrarily bad population

$Z$

-population, but only when some arbitrarily bad population

![]() $B$

is also added along with the

$B$

is also added along with the

![]() $Z$

-population. In other words, it is an avoidance condition for an additive version of the Very Repugnant Conclusion, which differs from the Repugnant Conclusion in that it compares a population of excellent lives to an extremely large number of lives barely worth living, plus a smaller number of very bad lives.Footnote

19

$Z$

-population. In other words, it is an avoidance condition for an additive version of the Very Repugnant Conclusion, which differs from the Repugnant Conclusion in that it compares a population of excellent lives to an extremely large number of lives barely worth living, plus a smaller number of very bad lives.Footnote

19

Figure 1. The Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition.

Our other different-number condition shall be the

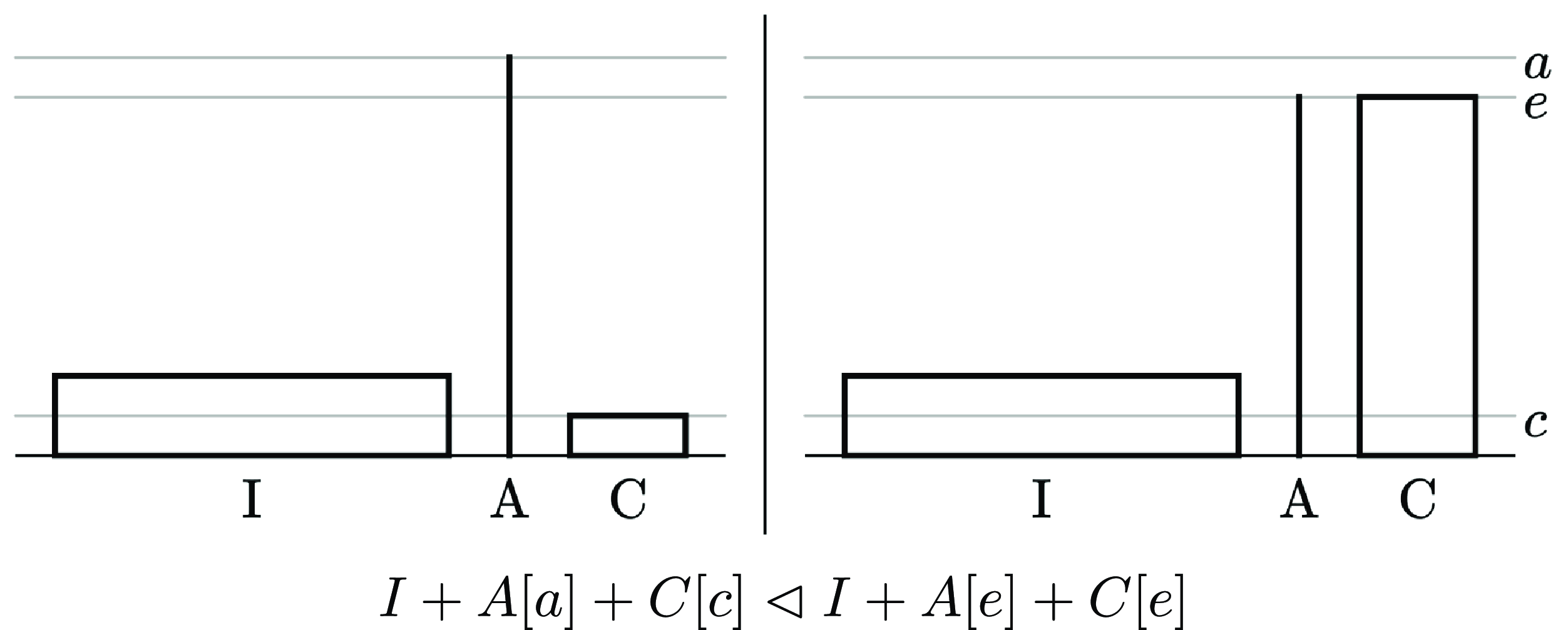

Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition

Footnote

20

There exists a bad wellbeing level

![]() $b$

which is not minimal,Footnote

21

and some number

$b$

which is not minimal,Footnote

21

and some number

![]() $n$

, such that for any group

$n$

, such that for any group

![]() $B$

of size at least

$B$

of size at least

![]() $n$

, any

$n$

, any

![]() ${b^ - } \le b$

, and any population

${b^ - } \le b$

, and any population

![]() $A$

containing only good lives,

$A$

containing only good lives,

The Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition, illustrated by Figure 2, requires that there is some population which is so bad that it is worse than any population consisting solely of good lives. While some of the premises of our impossibility theorem might be up for debate, I believe that this one is not, provided one countenances any different-number comparisons whatsoever.Footnote 22 The Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition is not satisfied by all proposed population axiologies; it is not, for instance, satisfied by positive critical level views, such as those discussed by Blackorby et al. (Reference Blackorby, Bossert and Donaldson2005: Ch. 5). But such views are to be rejected precisely because they do not satisfy the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition.Footnote 23

Figure 2. The Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition.

Our same-person principles shall be analogues of the ones appealed to by Arrhenius (Reference Arrhenius, Johansson, Österberg and Sliwinski2009, Reference Arrhenius, Dzhafarov and Perry2011, n.d.). They are more or less the same as the same-named principles in these works, with the main difference being that their claims are in terms of the

![]() $ \triangleleft $

relation, rather than the worseness relation.Footnote

24

Apart from this, they differ only notationally, and in one or two unimportant respects.Footnote

25

They are as follows.

$ \triangleleft $

relation, rather than the worseness relation.Footnote

24

Apart from this, they differ only notationally, and in one or two unimportant respects.Footnote

25

They are as follows.

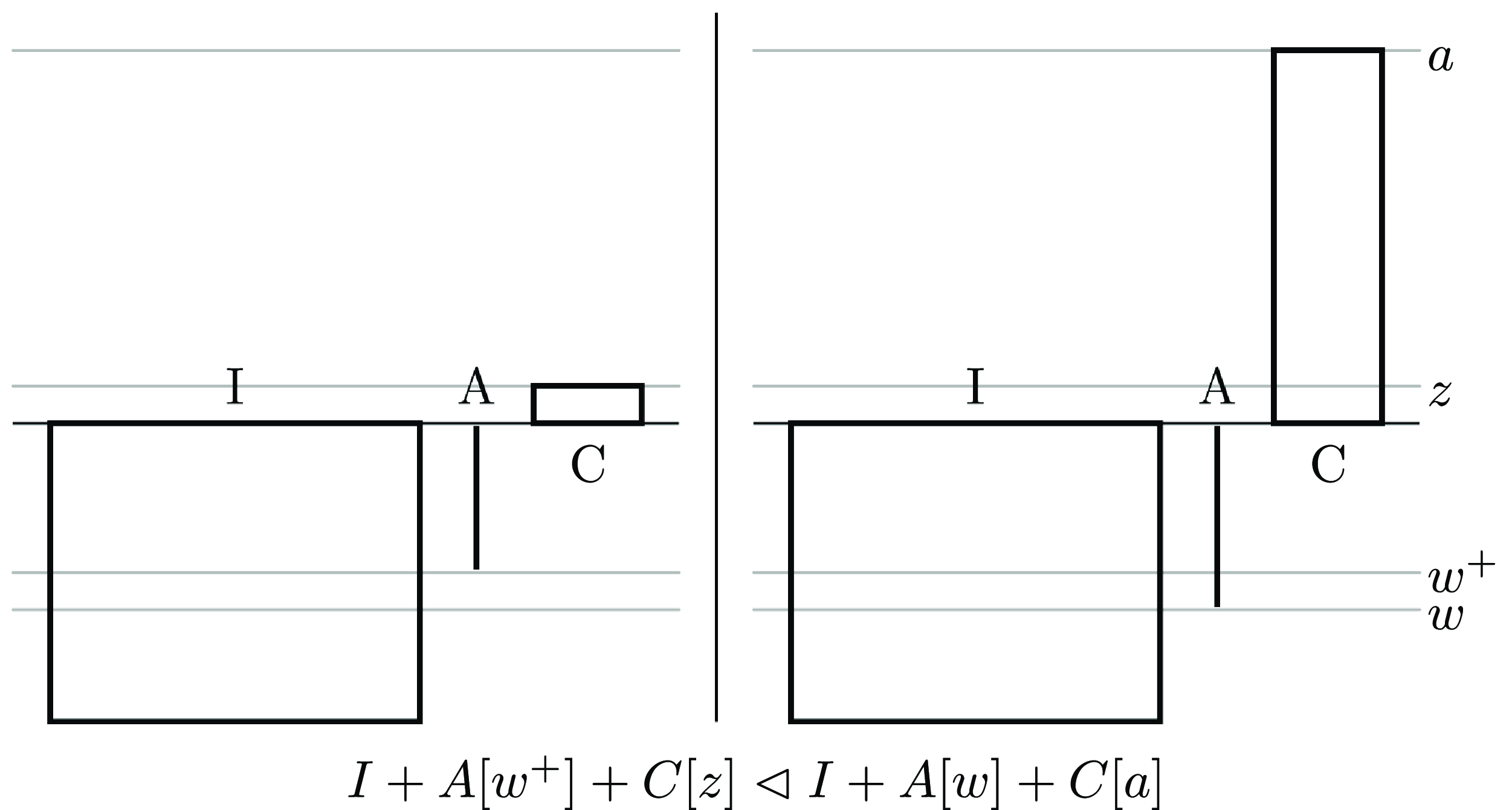

General Non-Elitism For any wellbeing levels

![]() $a \gt e \gt c$

, where

$a \gt e \gt c$

, where

![]() $a$

is close to

$a$

is close to

![]() $e$

, there exists a number

$e$

, there exists a number

![]() $n$

such that for any single-person group

$n$

such that for any single-person group

![]() $A$

, any group

$A$

, any group

![]() $C$

of at least

$C$

of at least

![]() $n$

people, and any unaffected background population

$n$

people, and any unaffected background population

![]() $I$

,

$I$

,

General Non-Elitism, illustrated by Figure 3, says that rather than providing a small benefit to a single better off person, it would be better to instead provide benefits of a fixed size to a sufficiently large number of worse-off people.

Figure 3. General Non-Elitism.

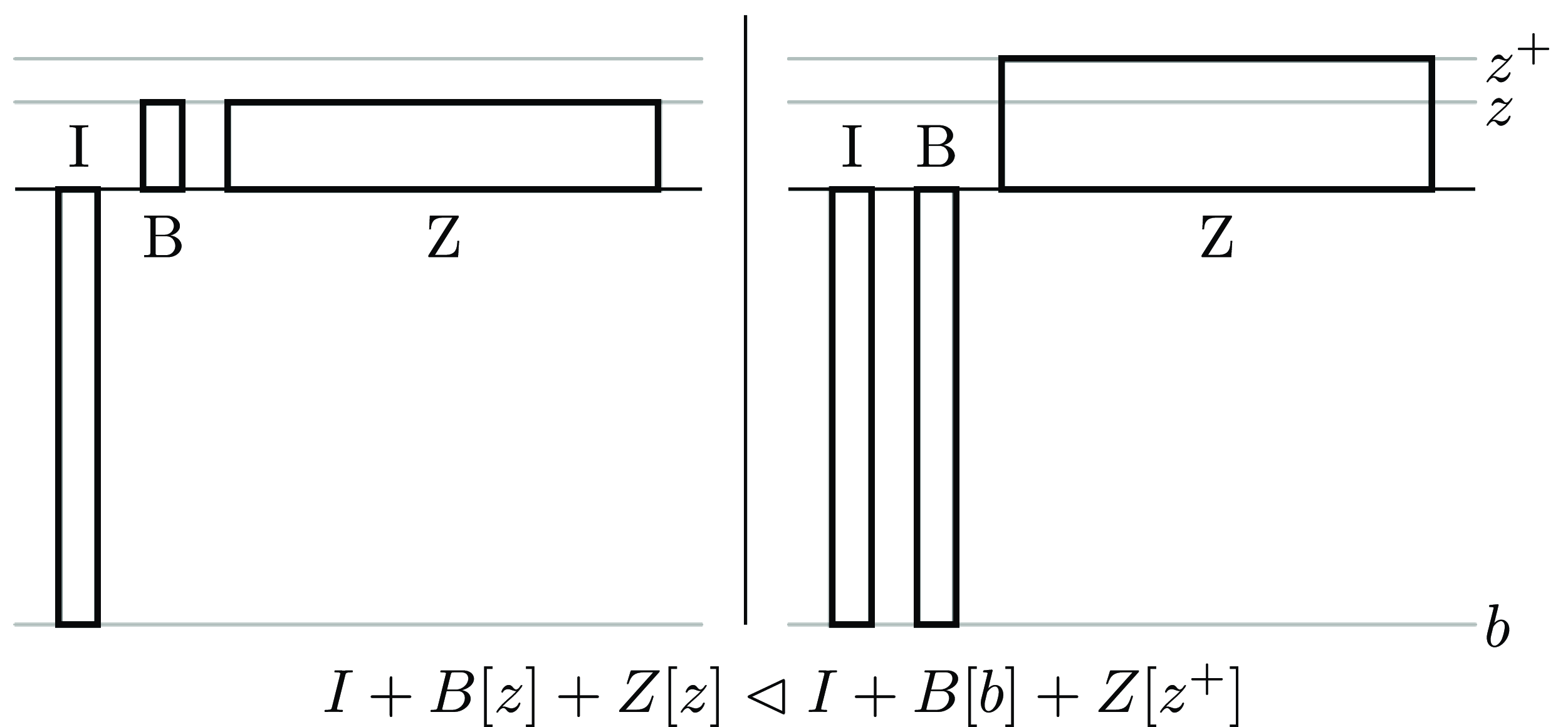

General Non-Extreme Priority For any wellbeing level

![]() $w$

, and any barely good level

$w$

, and any barely good level

![]() $z$

, there is a good wellbeing level

$z$

, there is a good wellbeing level

![]() $a{\rm{'}} \gt z$

, and a number

$a{\rm{'}} \gt z$

, and a number

![]() $n$

, such that for any wellbeing levels

$n$

, such that for any wellbeing levels

![]() $a \ge a{\rm{'}}$

and

$a \ge a{\rm{'}}$

and

![]() ${w^ + } \gt w$

, where

${w^ + } \gt w$

, where

![]() ${w^ + }$

is close to w, any group

${w^ + }$

is close to w, any group

![]() $A$

of size at least

$A$

of size at least

![]() $n$

, any single-person group

$n$

, any single-person group

![]() $C$

, and any unaffected background population

$C$

, and any unaffected background population

![]() $I$

,

$I$

,

General Non-Extreme Priority, illustrated by Figure 4, says that rather than benefiting a single person who is perhaps badly off to some small extent, it would be better to instead lift some sufficiently large number of people up from a barely good wellbeing level to some sufficiently good wellbeing level. Both principles are very plausible.

Figure 4. General Non-Extreme Priority.

3.5 The Additive Impossibility Result

That is enough groundwork to state the main result of this paper:

The Additive Impossibility Result There is no population axiology which satisfies all of the following conditions:

-

(1) Finite Fine-Grainedness.

-

(2) Acyclicity.

-

(3) The Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition.

-

(4) The Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition.

-

(5) General Non-Elitism.

-

(6) General Non-Extreme Priority.

3.6 Lemmas

To prove the Additive Impossibility Result, we shall need to appeal to three lemmas. We shall need to show that our premises imply “Inequality-Averse Addition”, “Sufficient Trade-Offs” and “Axiological Aggregation”. Roughly, according to Inequality-Averse Addition, large improvements to a first group of people are outweighed by small improvements to a sufficiently large second group of people who are worse off than the first group. According to Sufficient Trade-Offs, rather than having a first and second group of people, all at some barely good wellbeing level, it would be better if instead the first group were at some very good wellbeing level, and the second group were at some very bad wellbeing level, provided the first group is sufficiently larger than the second. According to Axiological Aggregation, rather than having a first and second group of people, all at some barely good wellbeing level, it would be better if the first group were at some slightly better level, and the second group were at some bad level, provided the first group is sufficiently larger than the second. Each of these principles applies in the presence of any unaffected background population. More precisely, the three lemmas we need, which are illustrated by Figures 5, 6 and 7 respectively, are as follows:

The Inequality Aversion Lemma The General Non-Elitism Condition and Finite Fine-Grainedness imply Inequality-Averse Addition. For any wellbeing levels

![]() $a \gt e \gt c$

, and any number

$a \gt e \gt c$

, and any number

![]() $n$

, there is a number

$n$

, there is a number

![]() $m$

such that if

$m$

such that if

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() $C$

are groups containing

$C$

are groups containing

![]() $n$

and at least

$n$

and at least

![]() $m$

lives respectively, and

$m$

lives respectively, and

![]() $I$

is any unaffected background population,

$I$

is any unaffected background population,

The Sufficient Trade-Offs Lemma The General Non-Extreme Priority condition and Finite Fine-Grainedness imply Sufficient Trade-Offs. For any barely good

![]() $z$

, any wellbeing level

$z$

, any wellbeing level

![]() $b \lt z$

, and any number

$b \lt z$

, and any number

![]() $n$

, there is a good wellbeing level

$n$

, there is a good wellbeing level

![]() $a{\rm{'}} \gt z$

and a number

$a{\rm{'}} \gt z$

and a number

![]() $m$

such that for any

$m$

such that for any

![]() $a \ge a{\rm{'}}$

, any group

$a \ge a{\rm{'}}$

, any group

![]() $A$

of size at least

$A$

of size at least

![]() $m$

, any group

$m$

, any group

![]() $C$

of size

$C$

of size

![]() $n$

, and any unaffected background population

$n$

, and any unaffected background population

![]() $I$

,

$I$

,

Figure 5. Inequality-Averse Addition.

Figure 6. Sufficient Trade-Offs.

Figure 7. Axiological Aggregation.

The Axiological Aggregation Lemma The General Non-Elitism Condition, General Non-Extreme Priority and Finite Fine-Grainedness imply Axiological Aggregation. For any barely good

![]() $z$

, any

$z$

, any

![]() ${z^ + } \gt z$

which is not maximal, any

${z^ + } \gt z$

which is not maximal, any

![]() $b \lt z$

, and any number of lives

$b \lt z$

, and any number of lives

![]() $n$

, there is a number of lives

$n$

, there is a number of lives

![]() $m$

such that if

$m$

such that if

![]() $B$

and

$B$

and

![]() $Z$

are groups of

$Z$

are groups of

![]() $n$

and

$n$

and

![]() $m$

people respectively, and

$m$

people respectively, and

![]() $I$

is any unaffected background population, then

$I$

is any unaffected background population, then

Proofs of all three lemmas may be found in the Appendix. The ideas of the proofs of the first two lemmas are fairly simple, and are exactly analogous to the proofs of Arrhenius’s (Reference Arrhenius, Dzhafarov and Perry2011) Lemmas 1.1 and 1.2 respectively. Both Inequality-Averse Addition and Sufficient Trade-Offs result from applying General Non-Elitism and General Non-Extreme Priority finitely many times. If a trade-off can be made between one person and

![]() $m$

people, then, by applying such a trade-off

$m$

people, then, by applying such a trade-off

![]() $n$

times, one can show that the same kind of trade-off can be made between

$n$

times, one can show that the same kind of trade-off can be made between

![]() $n$

people and

$n$

people and

![]() $n \cdot m$

people. Similarly, we can drop the restriction that only small differences in wellbeing can be traded-off by repeatedly applying such many-person trade-offs along a finite chain of consecutively close wellbeing levels between any two wellbeing levels.Footnote

26

Such a chain always exists by the Finite Fine-Grainedness condition. Essentially, the proofs of the first two lemmas just consist in showing that both things can be done. Axiological Aggregation may then be proved by applying both lemmas finitely many times (that is, by induction).

$n \cdot m$

people. Similarly, we can drop the restriction that only small differences in wellbeing can be traded-off by repeatedly applying such many-person trade-offs along a finite chain of consecutively close wellbeing levels between any two wellbeing levels.Footnote

26

Such a chain always exists by the Finite Fine-Grainedness condition. Essentially, the proofs of the first two lemmas just consist in showing that both things can be done. Axiological Aggregation may then be proved by applying both lemmas finitely many times (that is, by induction).

3.7 Proof of the Additive Impossibility Result

The Additive Impossibility Result, illustrated by Figure 8, is proved by constructing groups

![]() $B, B{\rm{'}}, Z$

and

$B, B{\rm{'}}, Z$

and

![]() $A$

, and wellbeing levels

$A$

, and wellbeing levels

![]() $a \gt z \gt {z^ - } \gt b \gt {b^ - }$

, in such a way that the populations illustrated in Figure 8 bear the

$a \gt z \gt {z^ - } \gt b \gt {b^ - }$

, in such a way that the populations illustrated in Figure 8 bear the

![]() $ \triangleleft $

relations as stated in the caption of the same figure. In this construction,

$ \triangleleft $

relations as stated in the caption of the same figure. In this construction,

![]() $a$

is a good wellbeing level,

$a$

is a good wellbeing level,

![]() $z$

and

$z$

and

![]() ${z^ - }$

are barely good levels, and

${z^ - }$

are barely good levels, and

![]() $b$

and

$b$

and

![]() ${b^ - }$

are bad wellbeing levels.

${b^ - }$

are bad wellbeing levels.

Figure 8. Proof of the Additive Impossibility Result.

We choose the sizes of groups

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() $B{\rm{'}}$

, and wellbeing levels

$B{\rm{'}}$

, and wellbeing levels

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() ${b^ - }$

, in such a way that the claim that

${b^ - }$

, in such a way that the claim that

![]() $\left( {ii} \right) \triangleleft \left( {iii} \right)$

is an instance of the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition, with

$\left( {ii} \right) \triangleleft \left( {iii} \right)$

is an instance of the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition, with

![]() $B$

the unaffected background population. We additionally stipulate that the size of group

$B$

the unaffected background population. We additionally stipulate that the size of group

![]() $B$

is sufficiently large for us to obtain that

$B$

is sufficiently large for us to obtain that

![]() $\left( {iii} \right) \triangleleft \left( {iv} \right)$

, by Inequality-Averse Addition. We obtain

$\left( {iii} \right) \triangleleft \left( {iv} \right)$

, by Inequality-Averse Addition. We obtain

![]() $\left( {iv} \right) \triangleleft \left( i \right)$

by the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition.Footnote

27

Since nothing said so far turns on the size of group

$\left( {iv} \right) \triangleleft \left( i \right)$

by the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition.Footnote

27

Since nothing said so far turns on the size of group

![]() $Z$

, we can ensure that

$Z$

, we can ensure that

![]() $Z$

is chosen to be large enough that Axiological Aggregation implies that

$Z$

is chosen to be large enough that Axiological Aggregation implies that

![]() $\left( i \right) \triangleleft \left( {ii} \right)$

. Finally, applying the Transitivity Lemma, we obtain that

$\left( i \right) \triangleleft \left( {ii} \right)$

. Finally, applying the Transitivity Lemma, we obtain that

![]() $\left( i \right) \triangleleft \left( i \right)$

, contradicting Acyclicity.

$\left( i \right) \triangleleft \left( i \right)$

, contradicting Acyclicity.

4. Which Premise Should be Rejected?

Since the premises of the Additive Impossibility Result are mutually inconsistent, at least one of them has to go. But which? For reasons stated earlier, I believe that we should not reject either Finite Fine-Grainedness or the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition. The remaining premises are Acyclicity, General Non-Elitism and General Non-Extreme Priority. Alternatively, we can reject the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition, thereby accepting an additive version of the Repugnant Conclusion. I shall consider each option in turn.

4.1 Acyclicity

It has been suggested, most prominently by Larry Temkin (Reference Temkin1987, Reference Temkin1996, Reference Temkin2012) and Stuart Rachels (Reference Rachels1998, Reference Rachels2001, Reference Rachels, Ryberg and Tännsjö2004), that we might avoid the Repugnant Conclusion by denying the transitivity of the at-least-as-good-as relation. While both authors also deny Acyclicity, it seems to me that the two moves are not on a par: it is less plausible to deny Acyclicity than it is to deny transitivity. To see why, let us first consider the case for (in)transitivity, and next consider the case for Acyclicity.

Why might we antecedently want to accept transitivity, beyond the mere intuitive plausibility of that principle? One standard argument holds that we must accept transitivity because it is an analytic feature of comparatives: as a matter of logic, whenever

![]() $A$

is

$A$

is

![]() $F$

-er than

$F$

-er than

![]() $B$

, and

$B$

, and

![]() $B$

is

$B$

is

![]() $F$

-er than

$F$

-er than

![]() $C$

,

$C$

,

![]() $A$

must be

$A$

must be

![]() $F$

-er than

$F$

-er than

![]() $C$

(Broome Reference Broome2004). It might alternatively be claimed that transitivity is otherwise central to the concept of value, or that value is inherently quantitative (and therefore transitive).Footnote

28

I’m not sure whether these arguments succeed, but even if we assume that they do, sceptics of transitivity still have the nuclear option: they can say that talking about value is a mistake, and that we should instead theorize in terms of some other non-transitive normative relation.Footnote

29

If some such normative relation fulfils whatever role we wanted goodness to play in our moral theory, it is unclear that much is lost by abandoning value-talk in favour of theorizing in terms of this new relation.

$C$

(Broome Reference Broome2004). It might alternatively be claimed that transitivity is otherwise central to the concept of value, or that value is inherently quantitative (and therefore transitive).Footnote

28

I’m not sure whether these arguments succeed, but even if we assume that they do, sceptics of transitivity still have the nuclear option: they can say that talking about value is a mistake, and that we should instead theorize in terms of some other non-transitive normative relation.Footnote

29

If some such normative relation fulfils whatever role we wanted goodness to play in our moral theory, it is unclear that much is lost by abandoning value-talk in favour of theorizing in terms of this new relation.

As an example, say that one population is impartially preferable to another just in case there is all-things-considered reason to hope, from an impartial perspective, that the first population would come about rather than the second.Footnote 30 The impartial preferability relation would appear to be able to do everything we want a value relation to do, but as far as I can see, there is no obvious argument to the effect that the impartial preferability relation must be transitive.Footnote 31

There are, however, strong pragmatic arguments for the irrationality of cyclic preferences. The most prominent of these are money pump arguments, some versions of which even apply to agents who take into account their expected future choices in their present decision-making.Footnote

32

If these arguments successfully show that cyclic preferences are irrational, the betterness relation must be acyclic (given that choosing in accordance with the betterness relation is not irrational). Importantly, pragmatic arguments seem to apply just as well to any relation which might be offered up as a replacement for betterness by a transitivity sceptic taking the nuclear option. If a normative relation

![]() $R$

is to play the role of traditional value relations in our conceptual theorizing, one feature it must have is to be morally decisive in cases in which only

$R$

is to play the role of traditional value relations in our conceptual theorizing, one feature it must have is to be morally decisive in cases in which only

![]() $R$

-relevant factors are at stake. As a result, if

$R$

-relevant factors are at stake. As a result, if

![]() $R$

is cyclic, abiding by morality will sometimes require one to act on cyclic preferences. Therefore, given that successfully abiding by morality is not irrational, that rational agents are not susceptible to exploitation by money pump, and that agents with cyclic preferences are susceptible to exploitation by money pump, any normative relation

$R$

is cyclic, abiding by morality will sometimes require one to act on cyclic preferences. Therefore, given that successfully abiding by morality is not irrational, that rational agents are not susceptible to exploitation by money pump, and that agents with cyclic preferences are susceptible to exploitation by money pump, any normative relation

![]() $R$

purporting to stand in for traditional value relations must satisfy Acyclicity.

$R$

purporting to stand in for traditional value relations must satisfy Acyclicity.

Note also that the only way to deny that agents with cyclic preferences are susceptible to exploitation by money pump is to claim that an agent’s preferences at some point in a decision tree can turn on more than just the options achievable for her going forward from that point.Footnote 33 But if that is true, then even if a theory says (for instance) that populations of excellent lives are better than very large populations of lives barely worth living, the same theory may nevertheless instruct an agent to bring about the population of lives barely worth living, if the agent is at some suitable point in a decision tree. Any non-exploitable theory must avoid actually issuing its usual judgement for at least some pair of populations involved in a betterness cycle, for at least some points in a decision tree. Denial of Acyclicity is therefore not a clean way of avoiding the Repugnant Conclusion without incurring other problematic commitments. Even if Acyclicity is false, we must still deny at least one of the premises of the Additive Impossibility Result in at least some sequential decision contexts, on pain of having to say that rational moral agents sometimes should get money pumped, even when they can see it coming.

4.2 General Non-Elitism and General Non-Extreme Priority

Recall that according to General Non-Elitism, rather than slightly benefiting one person who is comparatively well off, it would be better to instead benefit some sufficiently large number of people who are worse off. According to General Non-Extreme Priority, rather than slightly benefiting one person, who may initially be very badly off, it would be better to instead provide large benefits to a sufficiently large number of people whose lives are barely worth living.

For reasons mentioned in

![]() ${\rm{\S}}$

3.3, we shall understand these claims as applying in every option set. Such claims to the effect that some population

${\rm{\S}}$

3.3, we shall understand these claims as applying in every option set. Such claims to the effect that some population

![]() $A$

is worse than

$A$

is worse than

![]() $B$

in every option set can be denied in a number of ways, some of which are more plausible than others. First, one might reject the claim outright, insisting instead that there are cases where

$B$

in every option set can be denied in a number of ways, some of which are more plausible than others. First, one might reject the claim outright, insisting instead that there are cases where

![]() $A$

is better than

$A$

is better than

![]() $B$

in every option set. Second, one could adopt the weaker position that

$B$

in every option set. Second, one could adopt the weaker position that

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() $B$

might be incomparable in every option set.Footnote

34

Third, one could admit that it is determinately true that there is some case in which

$B$

might be incomparable in every option set.Footnote

34

Third, one could admit that it is determinately true that there is some case in which

![]() $A$

is not worse than

$A$

is not worse than

![]() $B$

(in every option set), but deny, for each pair of populations

$B$

(in every option set), but deny, for each pair of populations

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() $B$

falling under the principle, that it is determinately true that

$B$

falling under the principle, that it is determinately true that

![]() $A$

is not worse than

$A$

is not worse than

![]() $B$

(in every option set).Footnote

35

Fourth, one could accept that

$B$

(in every option set).Footnote

35

Fourth, one could accept that

![]() $A$

is worse than

$A$

is worse than

![]() $B$

in the pairwise option set consisting of just

$B$

in the pairwise option set consisting of just

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() $B$

, while allowing that this may fail to be the case in some larger option sets.Footnote

36

$B$

, while allowing that this may fail to be the case in some larger option sets.Footnote

36

There is little to be said for the first option. It would be very implausible to claim that it would be better to benefit a single better-off person, rather than arbitrarily many worse-off people. It would be only slightly less implausible to claim that it would be better to benefit a single badly off person by a very small amount, rather than benefiting a large number of people with lives barely worth living by a great amount. Moreover, Thornley (Reference Thornley2021) has shown that the two fixed-population principles can be weakened in the following way: the potential losses to one person in each principle can be replaced by arbitrarily small probabilities of a loss to one person. To my mind, this sinks the first option.Footnote 37

The remaining three options represent different paths for mitigating the intuitive costs of denying General Non-Elitism or General Non-Extreme Priority, but it is unclear how much they really help. Consider, for instance, General Non-Elitism. It seems false that benefiting a single person by a small amount could be better than benefiting an arbitrarily large number of less well-off people by larger amounts. It also seems false that benefiting the better-off person could be not worse than benefiting the less well-off people, or that benefiting the better-off person could fail to be determinately worse than benefiting the less well-off people. It is hard to see how even the last, weakest judgement could fail in any option set. Again, these claims become even more secure if we shift to probabilistic versions of our fixed-population principles. The prospects for rejecting General Non-Elitism or General Non-Extreme Priority, even when mitigated by taking one or more of options two to four, thus look dim to me.

4.3 Accepting the Repugnant Conclusion

To reject the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition is to accept that a population of excellent lives may fail to make a better addition than a population consisting of some very bad lives, together with arbitrarily many lives barely worth living. If this is accepted, it would seem natural to also accept a stronger, non-additive version of this claim: a population of excellent lives can be worse, by itself, than a combination of many bad lives with arbitrarily many lives which are barely worth living. That is, if we reject the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition, we should accept the Very Repugnant Conclusion.

One might deny this last claim. Avoidance of the Very Repugnant Conclusion is consistent with the negation of the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition, just as the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition is consistent with the negation of Weak Non-Sadism. (To see that the first of these claims is true, note that Average Utilitarianism avoids the (Very) Repugnant Conclusion, but does not satisfy the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition.)Footnote 38 One might therefore think that the Additive Impossibility Result tells us nothing new that is important: Weak Non-Sadism is arguably more plausible than the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition, and we already know from the Sixth Impossibility Theorem that (assuming the other premises) we must choose between Weak Non-Sadism and avoidance of the Repugnant Conclusion. So why worry? If we deny the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition, we are not much worse off than before with respect to avoiding the Very Repugnant Conclusion, because we have only rejected a principle which is less plausible than Weak Non-Sadism.

Put this way, I think the worry is overstated, because it seems to me that even if the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition is intrinsically less plausible than Weak Non-Sadism, there is still an important sense in which rejecting this condition would be “repugnant”. We are inclined to think that the Repugnant Conclusion is false because of its particular character: it could not be, we think, that a population of lives barely worth living is better than a population of excellent lives, just because the former contains a very large number of people. But if the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition is false, this intuition is undermined: it can be that a population of lives barely worth living is better as an addition than a population of excellent lives, just because the former contains a very large number of people. In contrast, if we deny Weak Non-Sadism, this does not by itself undermine the intuition of repugnance. Rejecting the Weak Non-Sadism condition can be a way of robustly avoiding the Repugnant Conclusion; rejecting the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition cannot.

Accepting the Repugnant Conclusion is a radical step. Most people who have thought seriously about the Repugnant Conclusion find it deeply counterintuitive, taking there to be decisive reason to reject any population axiology which has it, or a version of it, as a consequence.Footnote 39 Even so, it seems to me that unlike in the case of rejecting other premises of the Additive Impossibility Result, such as the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition, it is at least explicable how the Repugnant Conclusion could be true. A large enough population of lives barely worth living can indeed contain more – indeed, much more – of whatever makes life worth living than a smaller population of excellent lives. This fact alone cannot justify accepting the Repugnant Conclusion, because as most moral philosophers rightly observe, people are not mere containers of value. But it can at least help to make it intelligible that the Repugnant Conclusion might be true. Moreover, there are many impossibility theorems in the population ethics literature, many of which include premises which are quite different in character to those appealed to in the Additive Impossibility Result, but almost all of which include a condition for avoiding the Repugnant Conclusion. These can be seen as providing multiple lines of evidence supporting the Repugnant Conclusion.

It may well be objected at this point that what we are dealing with here is a version of the Very Repugnant Conclusion not Parfit’s original Repugnant Conclusion. It is widely held that even those who are able to hold their nose and accept the Repugnant Conclusion should nevertheless baulk at its Very Repugnant cousin. I think we should reject this conventional wisdom. Let me explain why.

Suppose that

![]() $b$

be a terrible wellbeing level, that

$b$

be a terrible wellbeing level, that

![]() $z$

is the level of a life barely worth living, and that

$z$

is the level of a life barely worth living, and that

![]() ${z^ - }$

is the level of a slightly worse life, which is still worth living. Let

${z^ - }$

is the level of a slightly worse life, which is still worth living. Let

![]() $B$

be a large group of people, and let

$B$

be a large group of people, and let

![]() $Z$

be a much larger group of people. The Very Repugnant Conclusion has it that a population

$Z$

be a much larger group of people. The Very Repugnant Conclusion has it that a population

![]() $B\left[ b \right] + Z\left[ z \right]$

can be better than a population of excellent lives, while the regular Repugnant Conclusion has it that a large enough population of lives barely worth living can be better than a population of excellent lives. The former is supposed to be harder to believe than the latter. But if this is so, it must be because there is something implausible about Axiological Aggregation, and therefore something implausible about either General Non-Elitism or General Non-Extreme Priority. For Axiological Aggregation implies that great losses of wellbeing for a large number of people can matter less than tiny gains for a huge number of people. It therefore implies that the population

$B\left[ b \right] + Z\left[ z \right]$

can be better than a population of excellent lives, while the regular Repugnant Conclusion has it that a large enough population of lives barely worth living can be better than a population of excellent lives. The former is supposed to be harder to believe than the latter. But if this is so, it must be because there is something implausible about Axiological Aggregation, and therefore something implausible about either General Non-Elitism or General Non-Extreme Priority. For Axiological Aggregation implies that great losses of wellbeing for a large number of people can matter less than tiny gains for a huge number of people. It therefore implies that the population

![]() $B\left[ b \right] + Z\left[ z \right]$

could be sequentially better than the population

$B\left[ b \right] + Z\left[ z \right]$

could be sequentially better than the population

![]() $B\left[ {{z^ - }\left] { + Z} \right[{z^ - }} \right]$

. This of course guarantees that if the latter population of lives barely worth living is sequentially better than a smaller population of excellent lives

$B\left[ {{z^ - }\left] { + Z} \right[{z^ - }} \right]$

. This of course guarantees that if the latter population of lives barely worth living is sequentially better than a smaller population of excellent lives

![]() $A$

, then the former population must also be sequentially better than

$A$

, then the former population must also be sequentially better than

![]() $A$

. This argument is illustrated by Figure 9.

$A$

. This argument is illustrated by Figure 9.

Figure 9. The Very Repugnant Proposition.

This argument can be made more precise. Specifically, it can be shown that, given Axiological Aggregation, the avoidance condition for the regular Repugnant Conclusion implies the avoidance condition for the Very Repugnant Conclusion. This is proved, as the “Very Repugnant Proposition”, in the Appendix.

(i)

![]() $ \triangleleft $

(ii); hence if (ii)

$ \triangleleft $

(ii); hence if (ii)

![]() $ \triangleleft $

(iii) then (i)

$ \triangleleft $

(iii) then (i)

![]() $ \triangleleft $

(iii).

$ \triangleleft $

(iii).

The upshot is that insofar as the Very Repugnant Conclusion is less plausible than the regular Repugnant Conclusion, the fault must lie with at least one of the same-person principles of General Non-Elitism or General Non-Extreme Priority, or with Finite Fine-Grainedness. But, as I have already argued, I do not think that we should reject these conditions.

For these reasons, I think that the least implausible response to the Additive Impossibility Result is to reject the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition, and thereby accept a version of the Very Repugnant Conclusion. But I expect that this opinion will not be widely shared. It is therefore worth mentioning one final option for those who simply cannot reject any particular premise of the Additive Impossibility Result, which is to flip the table and reject the entire basis of the argument.Footnote 40 One might take the Additive Impossibility Result, together with the many other impossibility theorems in the literature, to show that there is no such thing as a complete, justifiable theory of population ethics, and that we therefore have reason to adopt a moral error theory.Footnote 41 While I cannot offer a detailed argument against this sort of response here, it strikes me as an overreaction. It seems to me better to reject one premise than to reject all six.

5. Conclusion

I have presented the Additive Impossibility Result, which demonstrates that an additive version of the Repugnant Conclusion is extremely difficult to avoid. Unlike most other impossibility theorems, the Additive Impossibility Result does not include any version of the Mere Addition Principle, or any different-number principle which could feasibly be denied on the grounds that Mere Addition is false. Instead, it assumes the compelling Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition. The main practical upshot, I think, is this. In a choice between Weak Non-Sadism and avoidance of the Repugnant Conclusion, it may be unclear which should stay and which should go. Arguably, both are similarly compelling. In contrast, in a choice between the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition and the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition, it is clear that the former is by some margin the more plausible principle. Since these are the only two different-number principles involved in the Additive Impossibility Result, we may conclude that the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition cannot reasonably be maintained by abandoning the Non-Additive Weak Non-Sadism Condition. Neither do denial of Acyclicity or Finite Fine-Grainedness offer a straightforward path to retaining the Additive Anti-Repugnance Condition. Instead, the most plausible response to the Additive Impossibility Result, for opponents of the Repugnant Conclusion, may be to reject the fixed-population assumptions: either General Non-Elitism or General Non-Extreme Priority (or both). I have suggested that the intuitive costs of doing so might be mitigated by appealing to incompleteness, option set dependent betterness, indeterminacy, or some combination of the three. Yet even with these mitigating factors in play, I find these principles too compelling to deny.

Let me make one final point. While the relation ⪰ was interpreted throughout this paper as the moral at-least-as-good-as relation, its structure as a three-place relation incorporating option set dependence means that it can be given other interpretations. In particular, it can be interpreted as the at-least-as-much-reason-to-bring-about relation. The Additive Impossibility Result on this normative interpretation of ⪰ might be more troubling than the axiological interpretation of the theorem. On the normative version of my favoured response to the axiological Additive Impossibility Result, we would sometimes have more reason to bring about a future consisting of many tortured lives, and many more barely good lives, than we would have to bring about a future consisting of a smaller number of excellent lives. This is a conclusion I would be prepared to accept, but I don’t expect I shall have much company.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Ralf Bader, Timothy Campbell, Roger Crisp, Hilary Greaves, Todd Karhu, Kacper Kowalczyk, Seán O’Neill McPartlin, Aidan Penn, Daniel Ramöller, Teruji Thomas, Biqing Wang and three anonymous referees for helpful comments on this paper.

Tomi Francis is a Senior Researcher in philosophy at the University of Fribourg. His work focuses on obligations to future generations, value theory, interpersonal aggregation, and conflicts between moral ideals.

Appendix

The Transitivity Lemma

Transitivity Lemma Let

![]() $A$

,

$A$

,

![]() $B$

and

$B$

and

![]() $C$

be any populations. Suppose

$C$

be any populations. Suppose

![]() $A \triangleleft B$

and

$A \triangleleft B$

and

![]() $B \triangleleft C$

. Then

$B \triangleleft C$

. Then

![]() $A \triangleleft C$

.

$A \triangleleft C$

.

Proof of the Transitivity Lemma. Since

![]() $A \triangleleft B$

, there exists some sequence

$A \triangleleft B$

, there exists some sequence

![]() ${A_1},{A_2}, \ldots, {A_n}$

, with

${A_1},{A_2}, \ldots, {A_n}$

, with

![]() ${A_1} = A$

and

${A_1} = A$

and

![]() ${A_n} = B$

, such that, for each

${A_n} = B$

, such that, for each

![]() $i \lt n$

,

$i \lt n$

,

![]() ${A_i} \prec {A_{i + 1}}$

in every option set containing the two. Similarly, since

${A_i} \prec {A_{i + 1}}$

in every option set containing the two. Similarly, since

![]() $B \triangleleft C$

, there exists some sequence

$B \triangleleft C$

, there exists some sequence

![]() ${B_1},{B_2}, \ldots, {B_m}$

, with

${B_1},{B_2}, \ldots, {B_m}$

, with

![]() ${B_1} = B$

and

${B_1} = B$

and

![]() ${B_m} = C$

, such that, for each

${B_m} = C$

, such that, for each

![]() $i \lt m$

,

$i \lt m$

,

![]() ${B_i} \prec {B_{i + 1}}$

in every option set containing the two. The concatenation of these two sequencesFootnote

42

is a sequence

${B_i} \prec {B_{i + 1}}$

in every option set containing the two. The concatenation of these two sequencesFootnote

42

is a sequence

![]() ${C_1},{C_2}, \ldots, {C_k}$

, with

${C_1},{C_2}, \ldots, {C_k}$

, with

![]() ${C_1} = A$

and

${C_1} = A$

and

![]() ${C_k} = C$

, such that, for each

${C_k} = C$

, such that, for each

![]() $i \lt k$

,

$i \lt k$

,

![]() ${C_i} \prec {C_{i + 1}}$

in every option set containing the two. Thus we have

${C_i} \prec {C_{i + 1}}$

in every option set containing the two. Thus we have

![]() $A \triangleleft C$

.

$A \triangleleft C$

.

The Inequality Aversion Lemma

The Inequality Aversion Lemma The General Non-Elitism Condition and Finite Fine-Grainedness imply

Inequality-Averse Addition. For any wellbeing levels

![]() $a \gt e \gt c$

, and any number

$a \gt e \gt c$

, and any number

![]() $n$

, there is a number

$n$

, there is a number

![]() $m$

such that, if

$m$

such that, if

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() $C$

are groups containing

$C$

are groups containing

![]() $n$