Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most common of all psychiatric disorders and a leading cause of disability worldwide (Whiteford et al., Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari, Erskine and Vos2013). Although lifetime prevalence rates generated by cross-sectional epidemiologic surveys suggest that roughly a third of a population will develop MDD at some point during the life course (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005), corresponding figures drawn from longitudinal studies suggest that the true lifetime prevalence of the disorder may be substantially higher (Farmer, Kosty, Seeley, Olino, & Lewinsohn, Reference Farmer, Kosty, Seeley, Olino and Lewinsohn2013; Moffitt et al., Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, Kokaua, Milne, Polanczyk and Poulton2010; Schaefer et al., Reference Schaefer, Caspi, Belsky, Harrington, Houts, Horwood and Moffitt2017). This high prevalence is concerning, as MDD has been shown to predict lower life expectancy, increased susceptibility and risk of mortality from physical disease, and higher risk of suicide (Cassano & Fava, Reference Cassano and Fava2002). MDD also negatively affects multiple measures of occupational and interpersonal functioning (Adler et al., Reference Adler, McLaughlin, Rogers, Chang, Lapitsky and Lerner2006; Hirschfeld et al., Reference Hirschfeld, Montgomery, Keller, Kasper, Schatzberg, Moller and Versiani2000).

It is interesting that many of these functional impairments associated with MDD have been shown to persist even after patients’ depressed mood has remitted (Kennedy, Foy, Sherazi, McDonough, & McKeon, Reference Kennedy, Foy, Sherazi, McDonough and McKeon2007), suggesting that nonaffective factors may play a critical role in determining functional outcomes. One such well-established predictor of overall functioning is cognitive functioning. Although deficits in the ability to think or concentrate have been listed among the diagnostic criteria for MDD since the term major depressive disorder was first introduced in the mid-1970s (Philipp, Maier, & Delmo, Reference Philipp, Maier and Delmo1991), substantial interest in the treatment of cognitive impairment in the context of MDD has emerged more recently. For example, the National Academies of Sciences have hosted several workshops focused on understanding and treating cognitive dysfunction in depression in recent years (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015), and the US Food and Drug Administration is now considering proposals to approve drugs that specifically target cognitive deficits associated with depression (Ledford, Reference Ledford2016; Mullard, Reference Mullard2016). These initiatives have been motivated by a number of cross-sectional reviews and meta-analyses on MDD, which report (a) that depressed individuals score lower than healthy controls across a wide variety of cognitive tasks (Christensen, Griffiths, Mackinnon, & Jacomb, Reference Christensen, Griffiths, Mackinnon and Jacomb1997; Rock, Roiser, Riedel, & Blackwell, Reference Rock, Roiser, Riedel and Blackwell2014; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Kasai, Koji, Fukuda, Iwanami, Nakagome and Kato2004; Snyder, Reference Snyder2013), even at first episode (Lee, Hermens, Porter, & Redoblado-Hodge, Reference Lee, Hermens, Porter and Redoblado-Hodge2012), and (b) that these deficits can be observed even in individuals whose depression has remitted (Bora, Harrison, Yücel, & Pantelis, Reference Bora, Harrison, Yücel and Pantelis2013; Rock et al., Reference Rock, Roiser, Riedel and Blackwell2014). Greater cognitive deficits in the context of MDD in turn are associated with increased symptom severity (McDermott & Ebmeier, Reference McDermott and Ebmeier2009), higher rates of relapse and recurrence (Majer et al., Reference Majer, Ising, Künzel, Binder, Holsboer, Modell and Zihl2004), and impaired functioning after discharge from psychiatric hospitalization (Jaeger, Berns, Uzelac, & Davis-Conway, Reference Jaeger, Berns, Uzelac and Davis-Conway2006). Consequently, there is now considerable interest in the identification of novel therapeutic agents capable of bringing about “cognitive remission” in depressed patients (Bortolato et al., Reference Bortolato, Miskowiak, Köhler, Maes, Fernandes, Berk and Carvalho2016; Ledford, Reference Ledford2016), in addition to the remission of affective symptoms.

Before recommending that cognitive impairment in MDD should become a target of treatment, however, it is important to understand the origin and developmental course of these deficits. To date, two theoretical models have been proposed to explain the relationship between persistent cognitive impairments and MDD. The first, the cognitive reserve hypothesis, suggests that individuals with high intelligence are simply less likely to develop depression, due to either superior neural integrity or an increased ability to cope with or avoid stressful situations (Barnett, Salmond, Jones, & Sahakian, Reference Barnett, Salmond, Jones and Sahakian2006; Koenen et al., Reference Koenen, Moffitt, Roberts, Martin, Kubzansky, Harrington and Caspi2009; Salmond, Menon, Chatfield, Pickard, & Sahakian, Reference Salmond, Menon, Chatfield, Pickard and Sahakian2006; Scult, Knodt, Swartz, Brigidi, & Hariri, Reference Scult, Knodt, Swartz, Brigidi and Hariri2016). Thus, cognitive “deficits” seen in cross-sectional studies that compare the cognitive performance of depressed or remitted individuals to healthy volunteers would be an indicator of “traitlike” differences that present early in development, well before MDD onset. This model draws support from a number of longitudinal studies documenting that low intelligence at Time 1 is a robust predictor of subsequent depression at Time 2, summarized in a recent meta-analysis (Scult et al., Reference Scult, Paulli, Mazure, Moffitt, Hariri and Strauman2017). However, Scult et al. (Reference Scult, Paulli, Mazure, Moffitt, Hariri and Strauman2017) note that the majority of the studies demonstrating a predictive association between intelligence and MDD appear to be driven by depressive symptoms already present at the time of baseline cognitive assessment.

The second explanatory model, the scarring hypothesis, suggests that the cognitive deficits observed in depressed patients result from enduring changes in physiology and neurochemistry that begin around the time of MDD onset and impair cognitive functioning from that point forward (Lewinsohn, Steinmetz, Larson, & Franklin, Reference Lewinsohn, Steinmetz, Larson and Franklin1981). In this model, cognitive impairment in the context of MDD falls somewhere between trait and state factors. Although cognitive deficits are not proposed to precede the onset of depressive symptoms, they are hypothesized to persist well after the resolution of affective symptoms, potentially leaving MDD patients with a lifelong (albeit mild) impairment.

Although both of these models have been supported by previous research, the existing body of literature on persistent cognitive deficits in MDD is characterized by at least four important limitations. First, many of the studies that report associations between MDD and cognitive functioning have used small, clinical samples. Because depressed individuals receiving psychiatric care may differ from those who are not in several significant ways, the generalizability of these findings to the larger population of depressed individuals is unclear. This possibility is underscored by a recent study using population-representative data from the National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement, which reported that adolescents with past-year depression or dysthymia scored higher (rather than lower) on a measure of fluid intelligence compared to peers with no distress disorders (Keyes, Platt, Kaufman, & McLaughlin, Reference Keyes, Platt, Kaufman and McLaughlin2016).

Second, the majority of studies that report associations between IQ and MDD have assessed MDD at only a single time point. However, multiple psychiatric assessments are desirable in this context because longitudinal studies that have calculated the lifetime prevalence of MDD using both single and repeated assessments have generally found that repeated assessments generate 2.5 to 3 times higher prevalence estimates (Moffitt et al., Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, Kokaua, Milne, Polanczyk and Poulton2010; Takayanagi et al., Reference Takayanagi, Spira, Roth, Gallo, Eaton and Mojtabai2014). Thus, studies that use cognitive functioning to predict MDD at a single point in time are more likely to miscategorize individuals who have experienced or will experience depression as “healthy controls,” potentially biasing estimates of effect size.

Third, it is also desirable to analyze data drawn from studies with multiple cognitive assessments, particularly when evaluating participants for evidence of cognitive “scarring.” Despite this, the majority of studies that examine associations between cognitive performance and remitted depression are cross-sectional in nature, making it difficult to determine whether or not observed deficits represent a true decline from baseline ability following a depressive episode.

Fourth, relatively few studies of the link between IQ and MDD have taken rigorous steps to account for the presence or absence of comorbid diagnoses in diagnostic groups (see Scult et al., Reference Scult, Paulli, Mazure, Moffitt, Hariri and Strauman2017), and those that have assessed participants for comorbidity have tended to use a single assessment wave (Snyder, Reference Snyder2013). These designs limit interpretation of previous findings, as prior work has shown that many psychiatric disorders apart from MDD are predicted prospectively by low IQ (Batty, Mortensen, & Osler, Reference Batty, Mortensen and Osler2005; Gale, Batty, Tynelius, Deary, & Rasmussen, Reference Gale, Batty, Tynelius, Deary and Rasmussen2010; Gale et al., Reference Gale, Deary, Boyle, Barefoot, Mortensen and Batty2008), associated with contemporaneous impairments in cognitive test performance (Airaksinen, Larsson, & Forsell, Reference Airaksinen, Larsson and Forsell2005; Horner & Hamner, Reference Horner and Hamner2002; Muller & Roberts, Reference Muller and Roberts2005; Schaefer, Giangrande, Weinberger, & Dickinson, Reference Schaefer, Giangrande, Weinberger and Dickinson2013), and associated with cognitive “scarring” that lingers after symptomatic remission (Mann-Wrobel, Carreno, & Dickinson, Reference Mann-Wrobel, Carreno and Dickinson2011; Meier et al., Reference Meier, Caspi, Ambler, Harrington, Houts, Keefe and Moffitt2012, Reference Meier, Caspi, Reichenberg, Keefe, Fisher, Harrington and Moffitt2014; Stavro, Pelletier, & Potvin, Reference Stavro, Pelletier and Potvin2013). This raises the possibility that observed deficits thought to be associated with MDD are driven by either unobserved comorbidities or some shared, transdiagnostic process.

To address these limitations, we present tests of both the cognitive reserve and scarring hypotheses using data drawn from two population-representative, longitudinal studies. The first sample, the Dunedin Study, follows a population-representative cohort from birth to midlife, with IQ tests administered at ages 7, 9, 11, and 38 years, and neuropsychological testing conducted at ages 13 and 38. At age 38, Dunedin Study members were also administered a set of self- and informant-report questionnaires asking questions about perceived cognitive functioning. In addition, Dunedin Study members completed psychiatric interviews assessing them for a variety of common psychiatric disorders every few years starting at age 11.

Over its course, the Dunedin Study also assessed study members for a number of clinical indicators relevant to MDD, including disorder age of onset, persistence/recurrence of depressive episodes, self-rated impairment due to MDD, number of MDD diagnostic criteria endorsed, whether the study member received clinical attention for his or her MDD, and psychiatric comorbidity. We used these variables to test whether evidence of cognitive reserve or scarring is especially pronounced among study members with particularly early onset, severe, comorbid, or otherwise extreme cases of MDD.

Our second sample, the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study, follows a cohort of twins born in the United Kingdom from birth to age 18 years, with IQ tests administered at age 12 and a single psychiatric assessment using DSM criteria administered at age 18 years. We used the E-Risk Study's twin design to examine whether the lower IQ member of each twin pair was at relatively elevated risk of receiving a depression diagnosis at age 18. Because this design controls for shared environmental and (in monozygotic twin pairs) genetic factors that might normally account for an association between IQ and MDD, a positive finding would indicate that lower IQ predicts risk of MDD independent of these factors, providing support for a causal relationship.

Method

Because our article utilizes data drawn from two different longitudinal studies, we have divided the Methods section into two parts. Study 1 describes the assessment of IQ and mental disorder in the Dunedin Study, whereas Study 2 describes how these same constructs were assessed in the E-Risk Study. A description of the neuropsychological measures administered to Dunedin Study members at ages 13 and 38 can be found in the online-only supplementary materials.

Study 1: The Dunedin Study

Sample

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study is a four-decade, longitudinal investigation of health and behavior in a population-representative birth cohort. Study members (N = 1,037; 91% of eligible births; 52% male) were all individuals born between April 1972 and March 1973 in Dunedin, New Zealand, who were eligible for the longitudinal study based on residence in the province at age 3, and who participated in the first follow-up assessment at age 3. The cohort represents the full range of socioeconomic status on New Zealand's South Island. In adulthood, the cohort matches the New Zealand National Health and Nutrition Survey on health indicators (e.g., body mass index, smoking, general practitioner visits; Poulton, Moffitt, & Silva, Reference Poulton, Moffitt and Silva2015). The cohort is primarily White; fewer than 7% self-identify as having partial non-Caucasian ancestry. Assessments were carried out at birth and at ages 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, 32, and 38 years, when 95% of the 1,007 study members still alive took part. At each assessment wave, each study member is brought to the Dunedin research unit for a full day of interviews and examinations. The Otago Ethics Committee approved each phase of the study, and informed consent was obtained from all study members.

Measures of intelligence (IQ)

Childhood intelligence

We report results from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Revised (WISC-R; Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1974), using participants’ total scores averaged over the three assessment points at ages 7, 9, and 11 to represent intelligence in childhood.

Adult intelligence

We report results from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV; Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2008), administered at age 38.

Self-reported cognitive problems

At age 38, study members were queried about problems related to memory and attention. Study members reported how often in the past year (never, sometimes, or often) they experienced problems with keeping track of appointments, remembering why they went to a store, and repeating the same story to someone, among other items. Scores on each of the 17 questions were summed to create an overall measure of cognitive difficulties (M = 9.1, SD = 5.3, range = 0–31; internal consistency reliability = 0.83). Study members were also asked to rate the extent to which their cognitive difficulties interfered with their lives on a scale from 1 (some impairment) to 5 (severe impairment). Both self-reported cognitive difficulties (r = –.15) and the extent of impairment (r = –.16) were negatively correlated with adult full-scale IQ (both ps < .0001).

Informant-reported cognitive problems

Informant reports of study members’ cognitive function were obtained at age 38. Study members nominated people who “knew them well.” These informants were mailed questionnaires and asked to complete a checklist, including whether the study member had problems with his or her attention and memory over the past year. The informant-reported attention problems scale consisted of four items: “Is easily distracted, gets side-tracked easily,” “Can't concentrate, mind wanders,” “Tunes out instead of focusing,” and “Has difficulty organizing tasks that have many steps” (internal consistency reliability = 0.79). The informant-reported memory problems scale consisted of three items: “Has problems with memory,” “Misplaces wallet, keys, eyeglasses, paperwork,” and “Forgets to do errands, return calls, pay bills” (internal consistency reliability = 0.64). Both informant-reported attention problems (r = –.26) and informant-reported memory problems (r = .14) were negatively correlated with adult full-scale IQ (both ps < .0001).

Assessment of mental disorders

Mental disorders were ascertained in the Dunedin Study longitudinally using a periodic sampling strategy: every 2 to 6 years, study members were interviewed about past-year symptoms in a private in-person interview at the research unit by trained interviewers with tertiary qualifications and clinical experience in a mental health-related field such as family medicine, clinical psychology, or psychiatric social work (i.e., not lay interviewers). Interviewers used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children at the younger ages (11–15 years) and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule at the older ages (18–38 years). At each assessment, interviewers were kept blind to study members’ previous data, including mental health status. At ages 11, 13, and 15, diagnoses were made according to the then current DSM-III and grouped for this article into a single wave reflecting the presence or absence of specific juvenile mental disorders. At ages 18 and 21, diagnoses were made according to the DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987), and at ages 26, 32, and 38 diagnoses were made according to the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). This method led to 6 waves in total representing ages 11–15, 18, 21, 26, 32, and 38. In addition to symptom criteria, diagnosis required impairment ratings for that disorder ≥2 on a scale from 1 (some impairment) to 5 (severe impairment). Each disorder was diagnosed regardless of the presence of other disorders. Variable construction details, reliability and validity, and evidence of life impairment for diagnoses have been reported previously (Feehan, McGee, Raja, & Williams, Reference Feehan, McGee, Raja and Williams1994; Kim-Cohen et al., Reference Kim-Cohen, Caspi, Moffitt, Harrington, Milne and Poulton2003; Moffitt et al., Reference Moffitt, Harrington, Caspi, Kim-Cohen, Goldberg, Gregory and Poulton2007, 2010; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Moffitt, Caspi, Magdol, Silva and Stanton1996).

Study 2: The E-Risk Study

Sample

Participants were members of the E-Risk Study, a birth cohort of 2,232 British children. The sample was drawn from a larger birth register of twins born in England and Wales from 1994 to 1995 (Trouton, Spinath, & Plomin, Reference Trouton, Spinath and Plomin2002). Full details on the sample were reported previously (Moffitt & the E-Risk Study Team, Reference Moffitt2002). Briefly, the E-Risk sample was constructed in 1999–2000, when 1,116 families (93% of those eligible) with same-sex 5-year-old twins participated in home-visit assessments. This sample comprised 56% monozygotic (MZ) and 44% dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs. Within zygosity, 48% of MZ twins were male, and 50% of DZ twins were male. Families were recruited to represent the UK population of families with newborns in the 1990s, on the basis of residential location throughout England and Wales and mother's age. Teenaged mothers with twins were overselected to replace high-risk families who were selectively lost to the register through nonresponse. Older mothers having twins via assisted reproduction were underselected to avoid an excess of well-educated older mothers. The study sample represents the full range of socioeconomic conditions in Great Britain, as reflected in the families’ distribution on a neighborhood-level socioeconomic index (A Classification of Residential Neighborhoods, developed by CACI Inc. for commercial use; Odgers, Caspi, Bates, Sampson, & Moffitt, Reference Odgers, Caspi, Bates, Sampson and Moffitt2012): 25.6% of E-Risk families live in “wealthy achiever” neighborhoods compared to 25.3% nationwide; 5.3% versus 11.6% live in “urban prosperity” neighborhoods; 29.6% versus 26.9% live in “comfortably off” neighborhoods; 13.4% versus 13.9% live in “moderate means” neighborhoods; and 26.1% versus 20.7% live in “hard-pressed” neighborhoods. E-Risk underrepresents “urban prosperity” neighborhoods because such households are likely to be childless.

Follow-up home visits were conducted when the children were aged 7 (98% participation), 10 (96% participation), 12 (96% participation), and, most recently in 2012–2014, 18 years (93% participation). There were 2,066 children who participated in the E-Risk assessments at age 18, and the proportions of MZ (56%) and male same-sex (47%) twins were almost identical to those found in the original sample at age 5. The average age of the twins at the time of the assessment was 18.4 years (SD = 0.36); all interviews were conducted after the 18th birthday. Home visits at ages 5, 7, 10, and 12 years included assessments with participants as well as their mothers (or primary caretaker); the home visit at age 18 included interviews only with the participants. Each twin participant was assessed by a different interviewer.

The Joint South London, Maudsley, and the Institute of Psychiatry Research Ethics Committee approved each phase of the study. Parents gave informed consent, and twins gave assent between 5 and 12 years and then informed consent at age 18.

Measure of Intelligence (IQ): Childhood intelligence

We administered a short version of the WISC-R when study members were age 12 years. Using two subtests (matrix reasoning and information), we prorated study members’ IQs and standardized them to M = 100 (SD = 15), according to the method recommended by Sattler (Reference Sattler2008).

Assessment of depression

Unlike the Dunedin Cohort, which underwent repeated diagnostic assessments from age 11 to 38, the E-Risk Study members participated in only one diagnostic interview at age 18, during which they were assessed for past-year DSM-IV symptoms of MDD using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (Robins, Cottler, Bucholz, & Compton, Reference Robins, Cottler, Bucholz and Compton1995). As in the Dunedin Study, E-Risk Study members meeting symptom criteria for MDD also needed to report impairment ratings ≥2 on a scale from 1 (some impairment) to 5 (severe impairment) to receive a diagnosis.

Results

We present the results in three parts. Study 1 presents our tests of the cognitive reserve hypothesis, in which lower IQ in childhood is hypothesized to predict an increased risk of subsequent MDD. Study 2 presents our tests of the scarring hypothesis, in which IQ deficits are hypothesized to persist in individuals with a history of MDD, even after remission of their affective symptoms. Finally, Study 3 extends both of these analyses to neuropsychological measures assessing memory and executive functioning, two domains that have been repeatedly linked to MDD in previous work (Bora et al., Reference Bora, Harrison, Yücel and Pantelis2013; Hsu & Davison, Reference Hsu and Davison2017; Rock et al., Reference Rock, Roiser, Riedel and Blackwell2014).

Study 1: The cognitive reserve hypothesis

-

Does lower IQ in childhood predict increased risk of developing MDD?

To address this question, we started with 957 (92.3%) of the original 1,037 Dunedin Study members, including only those individuals who (a) had participated in at least half of the six mental health assessment waves from ages 11 to 38 and (b) had available childhood IQ data. Because schizophrenia is often accompanied by depression, and is associated with pronounced premorbid and postonset cognitive deficits as well as thought disorder symptoms (Kendler, Ohlsson, Sundquist, & Sundquist, Reference Kendler, Ohlsson, Sundquist and Sundquist2014; Meier et al., Reference Meier, Caspi, Reichenberg, Keefe, Fisher, Harrington and Moffitt2014; Reichenberg et al., Reference Reichenberg, Caspi, Harrington, Houts, Keefe, Murray and Moffitt2010; Schaefer et al., Reference Schaefer, Giangrande, Weinberger and Dickinson2013), we further refined our analytic sample by excluding all study members who received a diagnosis of schizophrenia by age 38 (N = 37). This step ensured that any observed associations between MDD and IQ were not driven by these individuals.

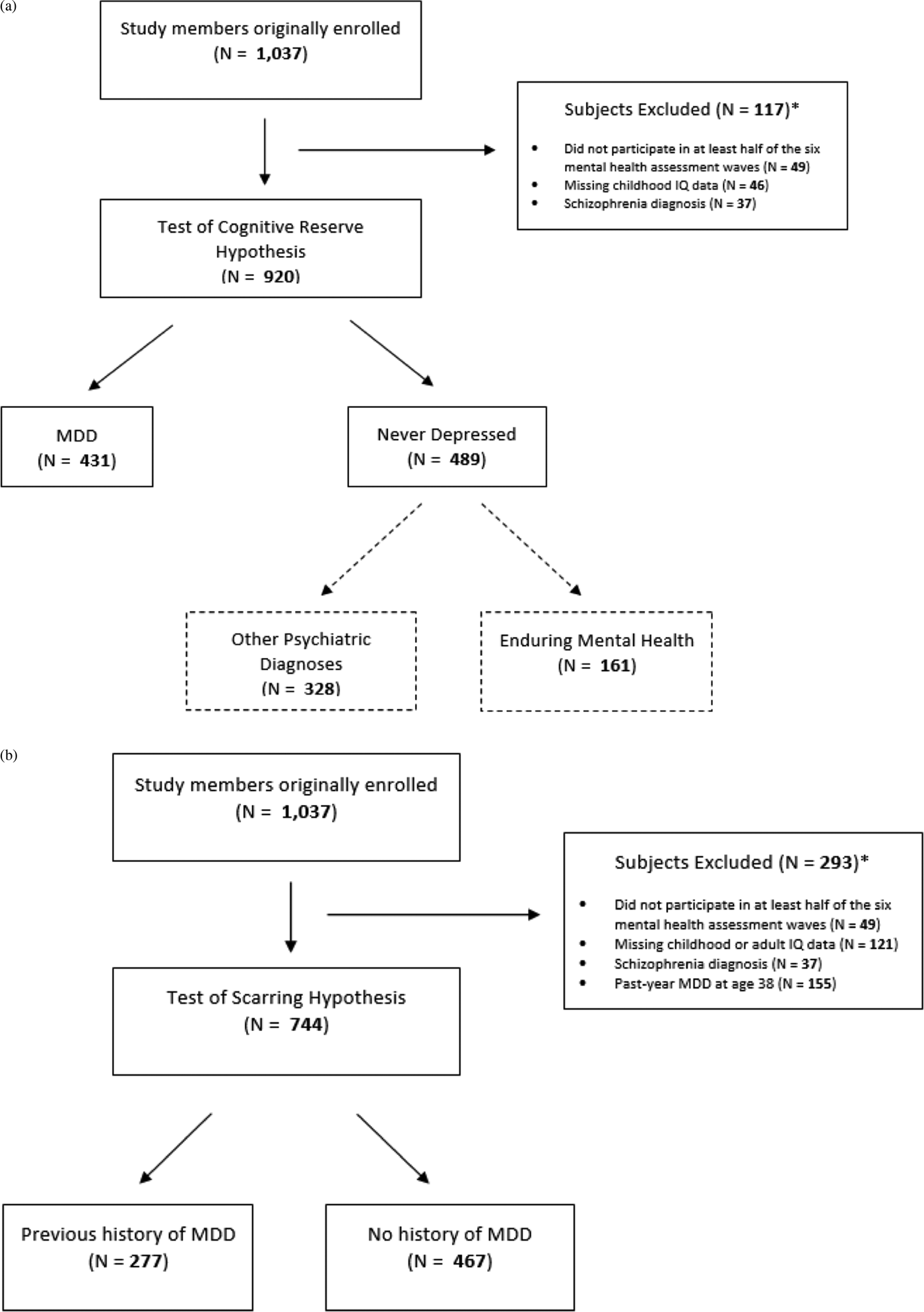

Of the remaining 920 study members, 812 (88.3%) contributed six waves of mental health data, 67 (7.3%) contributed five waves of mental health data, 26 (2.8%) contributed four waves of mental health data, and 15 (1.6%) contributed three waves of mental health data. From ages 11 to 38, 431 (46.9%) of these study members received a diagnosis of MDD at one or more assessment waves. These study members constituted the “ever-depressed” group. The remainder of the cohort (N = 489, 53.2%) did not meet criteria for a diagnosis of MDD between the ages of 11 and 38. These study members constituted the “never-depressed” group. Together, these groups composed the full analytic sample (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. Dunedin Study member flow diagrams for our tests of the (a) cognitive reserve hypothesis and (b) cognitive scarring hypothesis.

As an initial test of the cognitive reserve hypothesis, we conducted a follow-forward analysis using a modified Poisson regression model with robust standard errors to estimate relative risk for the binary outcome of lifetime MDD (Zou, Reference Zou2004). Methodologists have suggested that risk ratios are less inflated than odds ratios in situations where the outcome is common, which is the case for MDD in our sample (Cummings, Reference Cummings2009). The risk ratios presented can be understood as the ratio change in average risk of MDD for every 1-point increase in IQ. Using this approach, we found that risk of membership in the ever-depressed (N = 431; mean childhood IQ = 100.0, SD = 14.4) versus never-depressed group (N = 489; mean childhood IQ = 101.4, SD = 13.8) did not differ as a function of childhood IQ, controlling for sex, incident rate ratio (IRR) = 0.997, 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.992, 1.002], p = .247.

Previous studies have suggested that low childhood IQ is associated with an increased risk of developing not only depression but also a number of other psychiatric conditions, including anxiety and substance use disorders (Fergusson, Horwood, & Ridder, Reference Fergusson, Horwood and Ridder2005; Gale et al., Reference Gale, Deary, Boyle, Barefoot, Mortensen and Batty2008; Koenen et al., Reference Koenen, Moffitt, Roberts, Martin, Kubzansky, Harrington and Caspi2009; Rajput, Hassiotis, Hatch, & Stewart, Reference Rajput, Hassiotis, Richards, Hatch and Stewart2011). Thus, it is possible that our ability to detect a predictive relationship between childhood IQ and lifetime depression is limited by the presence of other psychiatric disorders in the “never-depressed” group. Fortunately, one advantage afforded by the Dunedin Study's repeated mental health assessments is that they allowed us to identify the small group of individuals who have never met criteria for any of the mental disorders assessed by the study (the “enduring-mental-health” group; Schaefer et al., Reference Schaefer, Caspi, Belsky, Harrington, Houts, Horwood and Moffitt2017), and to use these study members as a new comparison group (N = 161 who had childhood IQ data; mean childhood IQ = 102.3, SD = 14.0; Figure 1a). We thus conducted an additional follow-forward analysis to test whether childhood IQ was a significant predictor of membership in the ever-depressed versus enduring mental health groups, controlling for sex. Consistent with our previous results, we found that childhood IQ still did not appear to distinguish between the two groups, IRR = 0.997, 95% CI [0.994, 1.001], p = .136.

To provide a point of comparison, we also tested whether childhood IQ was a significant predictor of membership in the small group of study members with schizophrenia (N = 37; mean childhood IQ = 94.0, SD = 17.6) versus the majority of the cohort who were never diagnosed with schizophrenia (N = 920; mean childhood IQ = 100.7, SD = 14.1), controlling for sex. Here, low childhood IQ was associated with higher risk of receiving a schizophrenia diagnosis, IRR = 0.968, 95% CI [0.944, 0.992], p = .010.

-

Does lower IQ in childhood exert an effect on an individual's later risk of developing MDD independent of family-wide and genetic risk?

An even more powerful approach to testing the cognitive reserve hypothesis is to compare two children growing up in the same family. If the cognitive reserve hypothesis is correct, the sibling with higher IQ should be at lower risk of developing MDD. We tested this hypothesis in the E-Risk Longitudinal Twin Study using the following mixed-effects model:

In this specification, IQ effects are parsed into between-twin pair effects and within-twin pair effects using a logistic regression model, where i is used to index twin pairs and j represents individual twins within pairs, so πij and X ij represent, respectively, the probability of receiving a depression diagnosis and childhood IQ values for the jth twin of the ith pair, whereas ![]() $\bar X$i represents the mean childhood IQ of both twins within the ith pair. The between-twin pair regression coefficient (βB) estimates whether pairs of twins with higher average age 12 IQ are at lower risk of being diagnosed with MDD at age 18. In contrast, the within-twin pair regression coefficient (βW) estimates whether the twin with higher IQ than his or her co-twin is less likely to be diagnosed with MDD than his or her co-twin.

$\bar X$i represents the mean childhood IQ of both twins within the ith pair. The between-twin pair regression coefficient (βB) estimates whether pairs of twins with higher average age 12 IQ are at lower risk of being diagnosed with MDD at age 18. In contrast, the within-twin pair regression coefficient (βW) estimates whether the twin with higher IQ than his or her co-twin is less likely to be diagnosed with MDD than his or her co-twin.

We first estimated this model using data from all available twin pairs (MZ and DZ) in E-Risk. A significant between-twin pair effect would reflect family-wide factors common to both twins that influence IQ and MDD and may underlie their association. In contrast, a significant within-twin pair effect would indicate that possessing low IQ in childhood predicts MDD independent of any factors that are shared between siblings growing up in the same family (Carlin, Gurrin, Sterne, Morley, & Dwyer, Reference Carlin, Gurrin, Sterne, Morley and Dwyer2005). We then estimated this model using only the MZ twin pairs in the E-Risk Study. Because MZ twins are genetically identical, a significant within-twin pair effect would rule out the possibility that the association between IQ and MDD arises solely due to a shared genetic susceptibility that elevates risk of both phenotypes.

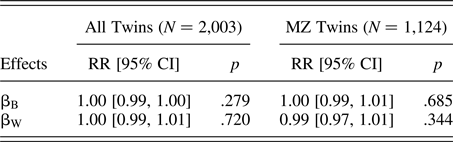

The parameters estimated from each of these models are reported in Table 1. Of the original 2,232 study members, we included 2,003 (89.7%), excluding twins if they belonged to a twin pair in which (a) 1 or more twins lacked IQ data at age 12, or (b) both twins lacked mental health assessment data at age 18. Of these 2,003 study members, 404 (20.2%) received a diagnosis of MDD. Both the full cohort and MZ twin only models indicated that neither between-twin pair nor within-twin pair differences in IQ tested at age 12 appear to predict risk of MDD at age 18, consistent with our results from the follow-forward analysis conducted in the Dunedin Cohort. These findings did not support the assumption that lower IQ is causally related to increased risk of subsequent depression.

-

Could lower IQ in childhood predict particularly early onset or severe MDD?

Table 1. Testing the cognitive reserve hypothesis: Between- and within-twin pair effects of childhood IQ on risk of depression at age 18 in the E-Risk cohort

Note: MZ, monozygotic; RR, rate ratio; βB, between-pair effects of mean childhood IQ (assessed at age 12) on risk of depression at age 18; βW, effect of within-pair differences in childhood IQ, controlling for the effects of shared family environment and (in MZ twins) genetics. Sex was included in each model as a covariate.

Although childhood IQ did not predict risk of future MDD in either cohort, it is still possible that a predictive relationship might exist between IQ in childhood and specific types of MDD, especially given previous research indicating a link between lower cognitive functioning and higher rates of relapse/recurrence, increased symptom severity, and impaired global functioning among depressed individuals (Jaeger et al., Reference Jaeger, Berns, Uzelac and Davis-Conway2006; Majer et al., Reference Majer, Ising, Künzel, Binder, Holsboer, Modell and Zihl2004; McDermott & Ebmeier, Reference McDermott and Ebmeier2009). Thus, we next tested the hypotheses that childhood IQ would predict measures of MDD age-of-onset, persistence, self-rated impairment, number of diagnostic criteria endorsed, clinical attention, or psychiatric comorbidity in the Dunedin Cohort.

Age of onset

We tested whether childhood IQ predicted an earlier age of depression onset by conducting a Cox proportional hazards regression using data from the full analytic sample (N = 920), controlling for sex. We recorded the assessment wave during which each study member in the ever-depressed group received his or her first diagnosis of MDD as the age of depression onset (M = 23.3, SD = 7.0, range = 15–38). We found that childhood IQ did not significantly predict depression age of onset, HR = 1.00, 95% CI [0.99, 1.00], p = .381, indicating that study members with low IQ did not appear to develop depression any earlier than study members with higher IQ.

Persistent course

We calculated depression recurrence/persistence for each study member in the ever-depressed group (N = 431) as the proportion of waves during which that study member met diagnostic criteria for MDD (M proportion = 0.30, SD = 0.16, range = 0.17–1.00). We then conducted a linear regression that predicted the proportion of waves each study member had received an MDD diagnosis as a function of childhood IQ, controlling for sex. We found no significant association between childhood IQ and this measure, b = –0.001, 95% CI [0.002, 0.000], t (428) = –1.31; p = .19, indicating that Dunedin Study members with low IQ who were diagnosed with MDD did not appear to spend significantly more study waves suffering from depression than their higher IQ peers with MDD.

Self-rated impairment

Dunedin Study members were asked to rate the functional impairment caused by their depressive symptoms on a scale from 1 (some impairment) to 5 (severe impairment) at each assessment wave between the ages of 18 and 38. We recorded self-rated impairment in this cohort as the maximum impairment rating given between the ages of 18 and 38 (M = 4.05, SD = 0.88, range = 2–5) by each study member who met diagnostic criteria for MDD at least once during this same period (N = 412). We limited our analysis of impairment to this age range because self-ratings of impairment were not collected in earlier assessments.

We conducted a linear regression model predicting self-rated impairment as a function of childhood IQ, controlling for sex. We found that childhood IQ was a significant predictor of self-rated impairment, b = –0.01, 95% CI [–0.01, 0.00], t (409) = –2.05, p = .041, suggesting that individuals with lower IQs who develop MDD tend to rate their depression as more impairing than their higher IQ peers with MDD. Such an effect is likely to be of little practical significance, however, as each 1-point increase in IQ is associated with a predicted decrease of only 1/100th of a point on a 5-point self-rated impairment scale.

Symptom count

We calculated symptom count as the number of MDD criteria endorsed by study members between the ages of 18 and 38 (M = 15.03, SD = 7.78, range = 4–41) by each study member who met diagnostic criteria for MDD at least once during this same period (N = 413). We limited our analysis of symptom criteria to this age range because symptom count data from earlier waves were not available.

We conducted a linear regression predicting symptom count between the ages of 18 and 38 as a function of childhood IQ, controlling for sex. We found no significant association between childhood IQ and this measure, b = –0.02, 95% CI [–0.07, 0.03], t (410) = –0.86, p = 0.392, suggesting that study members with lower IQs tended to endorse a similar number of MDD symptoms relative to study members with higher IQs.

Clinical attention

Dunedin Study members reported if they had contacted a professional (i.e., a general practitioner, psychologist, or psychiatrist) for a mental health problem or received psychiatric medication between the ages of 20 and 38. Of the 350 study members diagnosed with MDD during this same period in the full analytic sample (with present treatment contact data), 249 (71.1%) endorsed some form of treatment contact. We conducted a Poisson regression model with robust standard errors to calculate risk ratios for the binary outcome of treatment contact as a function of childhood IQ, controlling for sex. We found no significant association between childhood IQ and this measure, IRR = 1.002, 95% CI [0.997, 1.006], p = .464, suggesting that individuals with lower IQs who develop MDD were no more likely to receive treatment than their higher IQ peers with MDD.

Comorbidity

In the Dunedin Study, we operationalized comorbidity as the number of diagnostic families (including depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and conduct disorder) represented in a study member's complete history of psychiatric diagnoses accumulated between the ages of 11 and 38 years (M = 1.70, SD = 1.21, range = 0–5 in the full analytic sample; M = 2.54, SD = 0.97, range = 1–5 in the ever-depressed group). We did not include schizophrenia in our count of psychiatric comorbidities because study members who developed schizophrenia were excluded from the analytic sample.

We tested the association between childhood IQ and lifetime psychiatric comorbidity using a Poisson regression model that predicted the count of diagnostic families represented in each study member's diagnostic history between the ages of 11 and 38 as a function of childhood IQ, controlling for sex. We found an association between childhood IQ and comorbidity in both the full analytic sample (N = 920), IRR = 0.993, 95% CI [0.989, 0.996], p < .001, and among ever-depressed study members (N = 431), IRR = 0.995, 95% CI [0.991, 0.999], p = .025.

Figure 2a charts mean IQ as a function of psychiatric comorbidity in the context of MDD. Here we plot IQ scores for Dunedin Study members who have never had depression, study members who have had depression only, and study members who have had depression alongside one or more additional psychiatric conditions. Figure 2a shows that early IQ deficits were pronounced only among depressed study members with multiple psychiatric comorbidities. It is interesting that Dunedin Study members with “pure” depression, that is, those who were diagnosed only with depression between the ages of 11 and 38 years, appeared to have slightly higher IQs in childhood than study members who were never diagnosed with depression. We confirmed this observation through follow-forward analysis using Poisson regression, which indicated that Dunedin Study members with higher IQs were more likely to experience pure depression than no depression at all, controlling for sex (N = 543), IRR = 1.019, 95% CI [1.001, 1.037], p = .040.

Figure 2. (Color online) Mean (a) childhood IQ, (b) change in IQ from childhood to adulthood, and (c) subjective adult cognitive problems by lifetime psychiatric comorbidity in the Dunedin Cohort.

Finally, we used modified Poisson regression with robust standard errors to test whether low childhood IQ predicted the emergence of certain types of lifetime psychiatric comorbidities, but not others. We found that children who went on to develop MDD (N = 420) with lower childhood IQs were also at increased risk of developing anxiety disorders, IRR = 0.993, 95% CI [0.989, 0.996], p < .001, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, IRR = 0.949, 95% CI [0.929, 0.969], p < .001, and conduct disorder, IRR = 0.983, 95% CI [0.971, 0.996], p = .008, but not substance use disorders, IRR = 0.999, 95% CI [0.993, 1.006], p = .861.

Study 2: The scarring hypothesis

-

Are individuals with a history of MDD more likely to show evidence of or report lingering cognitive impairment as adults?

We next used data from the Dunedin Study to test for enduring cognitive deficits in previously depressed study members whose MDD had remitted by age 38, the time of adult cognitive assessment. Evidence of intellectual decline among these remitted individuals could be interpreted as evidence of a lingering depression-induced scar on cognitive functioning (Lewinsohn et al., Reference Lewinsohn, Steinmetz, Larson and Franklin1981). For these analyses, we used data from 744 study members who were assessed for mental disorder at age 38 but who did not meet criteria for a diagnosis of past-year MDD at age 38. This decision allowed us to separate the lingering cognitive scarring effects of a diagnostic history of MDD from the contemporaneous effects of a current episode of MDD. Similar to previous analyses, we also required these individuals to have (a) participated in at least half of the six mental health assessment waves from ages 11 to 38, (b) available childhood and adult IQ data, and (c) never received a diagnosis of schizophrenia. These individuals were divided into two groups: those with a previous history of MDD (N = 277; mean adult IQ = 101.2, SD = 14.4), and those with no previous history of MDD (N = 467; mean adult IQ = 101.0, SD = 14.4; Figure 1b).

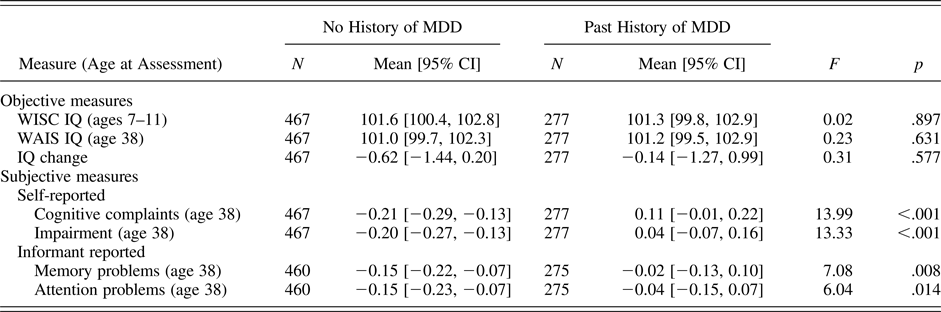

We conducted a series of one-way analyses of variance testing whether study members with a previous history of MDD differed from study members without such a history on age 38 IQ, self-reported cognitive problems, or informant-reported cognitive problems, controlling for sex. As shown in Table 2, we found that study members with a history of MDD scored higher on our subjective measures of cognitive problems (i.e., self-report and informant report), but were no different from study members without a history of MDD on any of our objective measures of cognitive functioning (i.e., WISC-R and WAIS-IV IQ, IQ change from childhood to adulthood). Taken together, these results suggest that study members with a history of depression were more likely to report that their cognitive functioning was impaired despite little to no measurable change (on average) in objective cognitive functioning as assessed by IQ tests.

-

Is there evidence of cognitive scarring following an episode of particularly severe or early onset MDD?

Table 2. Testing the scarring hypothesis: Cognitive functioning in study members who were not diagnosed with past-year MDD at age 38, by lifetime diagnostic history

Note: MDD, major depressive disorder; No History of MDD, study members who had never met criteria for MDD; WISC, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; Past History of MDD, study members who had met diagnostic criteria for MDD during a previous wave but no longer met criteria at age 38. The table includes only those study members who (a) were not diagnosed with past-year MDD at age 38 and (b) had present data for adult IQ. The scores on objective measures are reported as IQ points (mean = 100, SD = 15). Scores on subjective measures were standardized in the full cohort to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Means were compared across diagnostic groups through a series of one-way analyses of variance, controlling for sex.

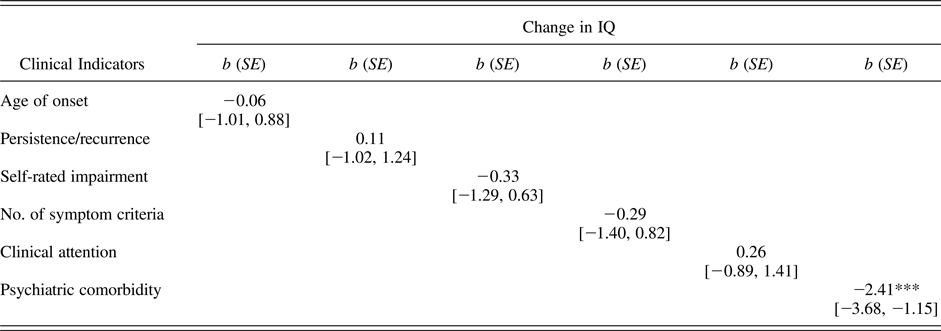

One criticism of the analyses summarized in Table 2 is that, in comparing only those individuals who were not depressed at age 38, we potentially ignore many of the most severe, chronic cases of MDD who continued to meet diagnostic criteria at the age 38 assessment wave. Consequently, we next tested whether any of our six clinical indicators (i.e., MDD age of onset, persistence/recurrence, self-rated impairment, number of diagnostic criteria endorsed, clinical attention, and comorbidity) predicted change in IQ from childhood (ages 7–11) to adulthood (age 38). If cognitive scarring is more common following severe or early onset cases of MDD, higher scores on these indicators should predict a more severe decline in IQ following a depressive episode.

As shown in Table 3, only psychiatric comorbidity was found to predict a steeper decline in IQ from childhood to adulthood. This finding suggests that the cognitive scarring reported following a depressive episode may be more attributable to disorders commonly comorbid with MDD rather than the experience of a depressive episode per se. Figure 2b charts mean change in IQ between childhood (ages 7–11) and adult (age 38) assessments as a function of psychiatric comorbidity in the context of MDD, whereas Figure 2c does the same with each of our four subjective measures of cognitive functioning. Consistent with Figure 2a, Figures 2b and 2c show that evidence of IQ decline and high subjective impairment was apparent only for depressed study members with multiple psychiatric comorbidities.

Table 3. Testing the scarring hypothesis: Change in IQ points from childhood to adulthood per standard deviation increase in each clinical indicator among study members diagnosed with MDD

Note: MDD, major depressive disorder. The table provides coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from a series of separate regression equations predicting change in IQ from childhood (assessed at ages 7–11) to adulthood (age 38) as a function of each clinical indicator, controlling for sex. The total numbers for each regression ranged from 347 to 414. Clinical indicators were standardized to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 in the full cohort to facilitate comparison across indicators.

***p < .001.

Study 3: Beyond IQ

A second potential criticism of the analyses presented in this paper is that IQ is too crude or too global of a measure to detect the subtle changes in cognitive functioning associated with MDD. This may be particularly true for tests of the scarring hypothesis, as previous work has suggested that scarring is most noticeable in the domains of executive functioning (e.g., working memory, attention regulation, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility/switching) and long-term memory (Bora et al., Reference Bora, Harrison, Yücel and Pantelis2013; Rock et al., Reference Rock, Roiser, Riedel and Blackwell2014). To address this concern, we selected from our data sets the measures most closely associated with these cognitive domains. A detailed description of these measures can be found in the online-only supplementary materials.

We used Poisson regression with robust standard errors to test whether childhood scores on our neuropsychological measures were significant predictors of future MDD in the Dunedin Study, controlling for sex (a further test of the cognitive reserve hypothesis). Because study members completed neuropsychological testing at age 13, we removed individuals who received a diagnosis of MDD during our first, juvenile assessment wave (ages 11–15) from the full analytic sample (shown in Figure 1a) in order to ensure that scores predicted future, rather than concurrent, MDD. As shown in online-only supplementary Table S.1, the association between MDD status and performance on Trails B was marginally significant, IRR = 1.00, 95% CI [1.00, 1.01], p = .053, but otherwise we found little evidence to suggest that any of these measures significantly predicted future MDD risk.

We next conducted a series of one-way analyses of variance testing whether study members with a previous history of MDD differed from study members without such a history on neuropsychological measures of executive functioning and memory administered at age 38, controlling for sex (a further test for cognitive scarring). As shown in online-only supplementary Table S.2, we observed no significant differences between groups, apart from finding that study members with a history of MDD scored significantly higher than study members without such a history on a measure involving the delayed recall of multiple word pairs (WMS-IV verbal paired associates), F (1, 738) = 4.40, p = .036. However, this difference did not survive correction for multiple comparisons. Viewed as a whole, our results provide little support for the notion that lower performance on measures of executive functioning or memory are predictors or enduring consequences of MDD.

Discussion

Contrary to prior research, the present study found little evidence to suggest that low cognitive functioning is either a predictor or an enduring consequence of a major depressive episode. We repeatedly found that associations between cognitive functioning and MDD were evident only in the context of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. The finding was true for both objective measures of cognitive functioning (i.e., WISC-R and WAIS-IV IQ, IQ change) and for self- and informant-reported indices of cognitive impairment. This pattern of findings suggests that, to the extent that evidence of cognitive reserve or cognitive scarring in MDD exists, it seems to be largely attributable to psychiatric comorbidities rather than to depressive symptoms per se.

The first hypothesis tested in the present study, the cognitive reserve hypothesis, suggested that individuals with lower cognitive functioning in childhood would be at increased risk of developing MDD later in life. However, childhood IQ did not predict risk of future MDD between the ages of 11 and 38 in the Dunedin Study, even when we compared individuals who developed MDD to those who experienced no diagnosable psychopathology of any sort. Similarly, study members’ performance on specific measures of memory and executive functioning at age 13 also did not predict future risk of MDD. In addition, we found no evidence that childhood IQ predicted MDD risk independent of family-wide and genetic risk when comparing E-Risk Study twins discordant for IQ. Together, these findings indicate that low IQ in childhood does not meaningfully increase risk of a depressive episode between early adolescence and midlife in these two cohorts from different eras and countries.

The second hypothesis tested in this paper, the scarring hypothesis, suggests that the experience of MDD is associated with cognitive impairments that persist even after affective symptoms have remitted. In nondepressed study members, we found little to no difference in mean childhood IQ, adult IQ, IQ change, or adult neuropsychological test scores between those with and without a past history of MDD, suggesting that the scarring effects of a depressive episode are not readily detected by these objective measures. However, we also found that those with an MDD history (and their informants) reported significantly greater subjective cognitive impairment than those without such a history.

The finding of greater subjective cognitive impairment in the context of no measurable objective deficit suggests at least two possible explanations. First, it is possible that any “lingering” cognitive impairments attributable to a history of MDD are largely subjective in nature. If this were true, the greater self-rated impairment reported by individuals with a history of MDD could reflect either (a) a tendency toward negative self-evaluation commonly seen in individuals vulnerable to depressive episodes, or (b) a form of the “good ol’ days bias,” in which individuals tend to view themselves as having been healthier (e.g., more cognitively advantaged) prior to a negative event (e.g., a depressive episode; Iverson, Lange, Brooks, & Rennison, Reference Iverson, Lange, Brooks and Rennison2010). The greater informant-rated impairment in turn could be caused by study members communicating these beliefs to their informants.

Second, it is possible that the cognitive deficits that either predispose individuals to depression or follow a depressive episode are contextual in nature. In other words, because formal cognitive testing is designed to measure patients’ optimal cognitive functioning under ideal conditions in the clinic, IQ and other neuropsychological tests may fail to capture genuine impairments that occur only under real-world conditions of high arousal, distraction, or affective distress in vulnerable individuals (i.e., those with a history of depression). The results of the present study therefore do not necessarily indicate that reports of cognitive impairment following a depressive episode are solely a product of patients’ cognitive distortions.

The results presented here differ from those of ancillary analyses featured in previous papers that also used data from the Dunedin Study, which reported weak but statistically significant associations between IQ and MDD (Koenen et al., Reference Koenen, Moffitt, Roberts, Martin, Kubzansky, Harrington and Caspi2009; Meier et al., Reference Meier, Caspi, Reichenberg, Keefe, Fisher, Harrington and Moffitt2014). However, these papers, like others in the literature, did not control for comorbidity when estimating the association between IQ and MDD. Moreover, that results can differ even in the same sample indicates that correlations between IQ and MDD are ephemeral and depend heavily on a study's analytical design and comparison groups.

To some, the proportion of Dunedin Study members diagnosed with MDD may seem unusually high, raising concerns about the representativeness of our sample. However, we have shown elsewhere that (a) the past-year prevalence rates of mental disorders in the Dunedin Cohort are similar to prevalence rates in nationwide surveys of the United States and of New Zealand (Moffitt et al., Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, Kokaua, Milne, Polanczyk and Poulton2010) and (b) lifetime prevalence estimates of Axis I mental disorders in the Dunedin Study are comparable to estimates calculated in other cohorts with repeated psychiatric assessments (Schaefer et al., Reference Schaefer, Caspi, Belsky, Harrington, Houts, Horwood and Moffitt2017). These observations indicate that the high lifetime prevalence rate of MDD reported here is due primarily to the advantage of our prospective assessment method rather than to an overabundance of mental disorder in New Zealand, or in this cohort.

Despite the methodological advantages provided by our two cohorts, we acknowledge limitations. First, although our study features results from two independent samples, the E-Risk Study did not contain enough psychiatric assessment waves for us to replicate the analyses conducted using the Dunedin Cohort. Thus, it will be important to test the extent to which our findings generalize across different populations in future studies, particularly those findings that relate to lifetime history of disorder.

Second, study members were assessed for past-year (rather than current) depressive symptoms. Moreover, Dunedin Study members tend to schedule data collection when they feel well, reducing the likelihood of acute depressive symptoms on the day of cognitive testing. This design feature meant that we were unable to control for baseline depressive symptoms at the time of cognitive assessment in our follow-forward analyses. However, given that no association was observed between childhood cognitive functioning and later MDD, it is unlikely that this would alter our conclusions. In addition, we were not able to examine the extent to which MDD was associated with short-term, contemporaneous decreases in cognitive functioning, an important question for future research.

Third, assessment of mental disorder in the Dunedin Cohort is both left- and right-hand censored, which means we cannot assess the relationship between IQ and episodes of MDD that occurred prior to age 11, or future cases that may onset after our most recent assessment at age 38. This limitation means that we are not able to comment on the extent to which either childhood-onset or late-onset depression are associated with childhood IQ, or the extent to which such episodes might scar future cognitive functioning.

Despite these limitations, our results have implications for the study and treatment of depression. In particular, they suggest that the persistent cognitive deficits commonly associated with MDD may not be attributable to depression per se, but rather to other psychiatric conditions that frequently co-occur with MDD (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Koretz, Merikangas and Wang2003; Melartin et al., Reference Melartin, Rytsälä, Leskelä, Lestelä-Mielonen, Sokero and Isometsä2002). Previous studies comparing the premorbid IQs of individuals who developed MDD to those who did not have found individuals with MDD had premorbid IQs approximately 3 points lower than healthy controls (Sørensen, Sæbye, Urfer-Parnas, Mortensen, & Parnas, Reference Sørensen, Sæbye, Urfer-Parnas, Mortensen and Parnas2012), which is comparable to the effect of comorbidity reported in the present study. These findings also shed light on some of the questions highlighted in recent workshops hosted by the National Academies of Sciences (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015), and suggest that researchers interested in treating the cognitive deficits associated with depression should perhaps widen their focus to consider alterations in fear-learning, attention, and executive functioning common to multiple disorders.

Our results further suggest that investigators seeking to demonstrate the existence of cognitive impairment in the context of a particular disorder should carefully assess participants for current and past psychiatric comorbidities. This step allows investigators to distinguish between impairments that are attributable to the disorder of interest versus other, comorbid conditions or some shared, transdiagnostic process.

Our findings also have implications for the prevention and treatment of MDD. Our finding that low childhood IQ does not appear to predict the development of MDD suggests that low IQ should not be considered as a risk factor for MDD. Similarly, our finding that even the most severely disordered individuals (diagnosed with MDD and 3+ comorbidities) scored only about 5 points lower, on average, than those with no history of depression indicates that our ability to predict the course of any one person's MDD based on premorbid intelligence is limited at best. Nevertheless, because subjective ratings of study members’ cognitive impairment tended to increase with each additional psychiatric comorbidity, it may be helpful to screen individuals who report ongoing cognitive impairment following a depressive episode for past and current anxiety, substance-use, attention-deficit, or psychotic disorders. In addition, such patients may benefit from cognitive therapy that examines the function and impact of beliefs of cognitive impairment, as well as therapies aimed at regulating affect and managing psychiatric symptoms, which may continue to impact cognitive functioning in certain contexts (e.g., when multitasking or under conditions of high emotional arousal).

In summary, we find that cognitive deficits are neither an antecedent nor an enduring consequence of MDD, absent psychiatric comorbidities. Thus, future research that seeks to assess and treat cognitive scarring in the context of psychiatric illness would be wise to investigate psychopathology broadly rather than MDD specifically. In addition, rather than focusing on cognitive impairment as a risk factor for MDD or a lingering consequence of the disorder, our results suggest that treatment and prevention efforts should focus on evaluating, and perhaps treating, cognitive deficits that co-occur with depressive symptoms. We hope that our findings will inform studies aiming to develop treatments for these impairments, as well as spur additional research dedicated to better understanding the complex interplay between affective symptoms and cognitive functioning in the individuals who suffer from this disorder.

Supplementary Material

To view the supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941700164X.