1. Introduction

Many children grow up speaking a heritage language at home, and the societal language at school. Heritage Language (HL), also defined as “first language (L1),” “family language,” or “minority language,” refers to a language spoken at home that is not dominant in the speaker’s local context (Rothman, Reference Rothman2009) (i.e., Arabic in the context of Italy, as is the case in the present study). Heritage Bilingual (HB) children might lag behind their monolingual peers in second language (L2) (i.e., the language of schooling, Italian in the present study) competence in preschool years due to less and later exposure to L2 but also because children from migrant backgrounds often come from families with a low socio-economic status (SES) (Hoff, Reference Hoff2013). Furthermore, there is high heterogeneity in language exposure at home, since some parents speak L2 in the home context, whereas others mainly use their heritage language(s).Footnote 1

The present study was conducted in Italy, where the first large waves of immigration started around 1999/2000, and have shown a progressive increase. Students from migrant backgrounds represent 10.3% of the school population (MIUR, 2021), and the vast majority were born in Italy (81.9%). Migrant families in Italy have a mean income roughly <56% of that of families with two parents with Italian citizenship, and the composite index of poverty and social exclusion risk is 56.8% for families with two parents with migrant background, compared to 23.4% of families with both parents with Italian citizenship (ISTAT, 2022). Access to preschool is free in Italy, although lunches and school materials may incur costs for families; children from migrant backgrounds have lower attendance rates to preschool programs (83.7%) compared to children born in families with Italian citizenship (96.3%).

Overall, bilingualism is a multidimensional phenomenon, and, as suggested by Paradis (Reference Paradis2023), various sources of individual differences might shape heritage language development, including internal (e.g., WM, nonverbal reasoning), proximal (e.g., L2 versus HL use at home), and distal (e.g., family SES) factors. The phenomenon of first language attrition seems to be present in many HB children (Gallo et al., Reference Gallo, Bermudez-Margaretto, Shtyrov, Abulatelebi, Kreiner, Chitaya, Petrova and Myachykov2021), due to parents’ beliefs that employing L1 in the family context might negatively affect children’s L2 proficiency (Wilson, Reference Wilson2020). Although previous evidence has shown that L1 competence might support L2 development (Cummins, Reference Cummins1979), minor evidence has been collected on heterogeneous language-minority groups, considering both L1 and L2 linguistic skills and including SES in the study design. Indeed, SES might influence the development of linguistic skills in both L1 and L2 (Hoff, Reference Hoff2013; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Brouwer, de Bree and Verhagen2019). In addition, increasing evidence suggests that cognitive functions have a significant role in L2 acquisition (Bouffier et al., Reference Bouffier, Barbu and Majerus2020).

Based on these findings, the present study aims to investigate the multiple sources of individual differences shaping both L1 and L2 linguistic profiles in a sample of heritage bilingual children attending preschool. In particular, attention is given to key predictors such as linguistic exposure at home, SES, and children’s nonverbal reasoning and phonological working memory (WM) skills. Examining these predictors simultaneously across the two languages is crucial, as they may differentially influence L1 and L2 development. This approach allows for a more precise understanding of the mechanisms underlying bilingual language outcomes and highlights potential language-specific and shared pathways in early bilingual acquisition.

1.1. L1 and L2 competences: Reciprocal interaction and the effect of sociolinguistic background

Considering the relation between linguistic skills in L1 and L2, Cummins’ Interdependence Hypothesis (1979) states that surface linguistic features of both languages lie on a common underlying linguistic competence, and “the development of competence in a second language (L2) is partially a function of the type of competence already developed in L1 at the time when intensive exposure to L2 begins” (p. 222). The interdependence hypothesis has been supported by later studies, with particular reference to the acquisition of prepositions and pronouns (Perozzi & Sanchez, Reference Perozzi and Sanchez1992; Spanish-English bilinguals), listening comprehension skills (Sierens et al., Reference Sierens, Van Gorp, Slembrouck and Van Avermaet2020; Turkish-Dutch emergent bilinguals), and syntactic abilities (Soto-Corominas et al., Reference Soto-Corominas, Daskalaki, Paradis, Winters-Difani and Janaideh2021; Syrian-Arabic and English).

Other authors have challenged the interdependence hypothesis. Marchman et al. (Reference Marchman, Martínez-Sussmann and Dale2004) reported that grammatical skills in each language were strongly tied to vocabulary growth in that language but grammatical outcomes were only weakly related to lexical level or grammatical accomplishments in the other language, as reported by parents’ questionnaires. Proctor et al. (Reference Proctor, August, Snow and Barr2010) suggested that the interdependence continuum hypothesis varies based on similarities or differences between the languages involved in the study (Spanish and English in their case). Goodrich et al. (Reference Goodrich, Lonigan, Kleuver and Farver2016) proposed that Cummins’ broad notion of transfer may not apply to vocabulary knowledge; in their study, children’s overall level of vocabulary knowledge in L1 (Spanish) was not predictive of subsequent vocabulary development in L2 (English).

In addition to interdependence, lexical bootstrapping may help explain L1–L2 relationships, as vocabulary provides semantic and distributional cues that support morphosyntactic acquisition (Marchman & Bates, Reference Marchman and Bates1994). Other evidence also highlights reciprocal effects: syntactic bootstrapping can support vocabulary learning, especially for verbs, by using sentence structure to infer meaning (Cao & Lewis, Reference Cao and Lewis2021). This suggests that such bidirectional mechanisms may operate within and across both languages.

Other studies have evaluated the relationships between linguistic exposure at home and children’s linguistic skills in L1 and L2. A positive relationship has been found between more L1 use at home and stronger syntactic abilities in the same language (Albirini, Reference Albirini2014; Daskalaki et al., Reference Daskalaki, Chondrogianni, Blom, Argryri and Paradis2019; Jia & Paradis, Reference Jia and Paradis2020). Similarly, length of exposure to L2 has been reported to be positively associated with L2 linguistic skills (Chondrogianni & Marinis, Reference Chondrogianni and Marinis2011; Paradis et al., Reference Paradis, Rusk, Sorenson Duncan and Govindarajan2017; Sorenson Duncan & Paradis, Reference Sorenson Duncan and Paradis2020), even if some studies did not report a significant association (Chiat et al., Reference Chiat, Armon-Lotem, Marinis, Polišenská, Roy, Seeff-Gabriel and Gathercole2013). However, evidence regarding the effects of non-native-speaking parents using L2 in the home environment due to beliefs concerning the potential negative effects of L1 is still limited (Golberg et al., Reference Golberg, Paradis and Crago2008; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Harding and Roulstone2017; Place & Hoff, Reference Place and Hoff2011, Reference Place and Hoff2016). Golberg et al. (Reference Golberg, Paradis and Crago2008), for example, found that parents’ use of English as L2 at home did not enhance English children’s vocabulary. Further, L2 exposure at home might be mitigated by other factors, such as SES and parental fluency.

In this regard, it has been shown that higher family SES is related to better children’s lexical skills (see Hoff, Reference Hoff2006) and enhanced listening/reading comprehension (Bonifacci et al., Reference Bonifacci, Ferrara, Pedrinazzi, Terracina and Palladino2022; Bonifacci, Atti, et al., Reference Bonifacci, Atti, Casamenti, Piani, Porrelli and Mari2020) in monolingual populations. However, the relationship between parental educational levels and the quality of linguistic input may be more complex for bilingual children (Gathercole, Reference Gathercole, Nicoladis and Montanari2016), as parents may be proficient in just one of the languages the child is exposed to. Hoff (Reference Hoff2013) reported results concerning early language trajectories of HB children from low-SES families living in an anglophone environment. She found that they are more likely to enter primary school with lower levels of English (i.e., their L2) in comparison to those from middle-class monolingual families.

However, the home learning environment can perhaps be considered a mediator for the role of SES in early literacy/numeracy competencies in preschoolers. These competencies cannot be explained solely in terms of socioeconomic background; the influence of children’s home context must be considered (Bonifacci et al., Reference Bonifacci, Compiani, Affranti and Peri2021). Mothers’ educational background has been found to contribute significantly to variability in children’s L2 vocabulary scores (Golberg et al., Reference Golberg, Paradis and Crago2008; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Brouwer, de Bree and Verhagen2019), although results are inconsistent (Paradis, Reference Paradis2011). Gatt et al. (Reference Gatt, Baldacchino and Dodd2020) found a positive relationship between SES, measured by means of the Hollingshead Four Factor Index of Social Status (Hollingshead, Reference Hollingshead1975), and English vocabulary, but not with Maltese vocabulary, the language most often spoken at home. In their study, Sorenson Duncan and Paradis (Reference Sorenson Duncan and Paradis2020) highlighted that mothers with a higher educational level in L2 showed higher L2 fluency and provided more linguistic input to children. A study conducted in Italy (Dicataldo & Roch, Reference Dicataldo and Roch2020) found that variation in SES was predictive of vocabulary, grammar, and WM skills after checking for the quantity of bilingual exposure. On the other hand, variation in bilingual exposure predicted vocabulary and narrative comprehension more effectively than the variation in SES.

Regarding the relationship between SES and cognitive functions, a classic study by Morton and Harper (Reference Morton and Harper2007) demonstrated the importance of SES as a fundamental dimension when assessing bilingual cognition. Their observation was initially directed towards studies addressing the so-called bilingual advantage, suggesting that a higher SES might partially explain the better performances in executive function tasks in bilinguals compared to monolinguals. The role of SES on cognitive skills was later investigated in low-SES populations. Indeed, Engel de Abreu and colleagues (Reference Engel de Abreu, Cruz-Santos, Tourinho, Martin and Bialystok2012) found that Portuguese-Luxembourgish bilinguals from low-SES backgrounds outperformed Portuguese monolinguals with similar SES in cognitive control tasks. Although these results support the view of a bilingual advantage in some executive functioning domains, it may be helpful to determine the impact of SES since it might differentially affect linguistic and cognitive development in bilinguals (Calvo & Bialystok, Reference Calvo and Bialystok2014; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Thoemmes and Lust2016).

To conclude, it is important to introduce SES as a structural variable related to families’ circumstances rather than as an innate feature of the family itself. For example, Hannon et al. (Reference Hannon, Nutbrown and Morgan2020) suggested that disadvantage is not inherent in individuals but might be the result of relationships between individuals, society, and the school system. This means that when evaluating education and occupation levels, as in the present study, it is important to bear in mind that these variables should be interpreted as something that characterizes the status of family members and not necessarily their skills, potentials, and habits. In their study, Hannon et al. (Reference Hannon, Nutbrown and Morgan2020) reported results from a preschool literacy intervention programme involving disadvantaged families. The program’s aim was to increase teaching of emergent literacy in the home context and to increase parents’ awareness about everyday opportunities and knowledge about how to help their children’s literacy. The parental training was beneficial and demonstrated how parental awareness and family language policies may be more effective in the face of disadvantages related to SES.

1.2. The effect of children’s nonverbal reasoning and phonological WM skills on L1 and L2 competencies

As suggested by Paradis (Reference Paradis2023), the source of variation in linguistic development might also be shaped by child-internal factors. The author refers, among others, to “cognitive abilities that comprise language aptitude … often measured through tasks like non-word repetition (verbal short-term memory), backwards digit span (WM) or nonverbal IQ tests” (p. 799).

One of the main areas investigated in previous studies is the role of WM (broadly inserted in Baddeley’s theoretical framework, Baddeley, Reference Baddeley1992). For example, Bouffier et al. (Reference Bouffier, Barbu and Majerus2020) studied the results of tasks designed to measure WM and auditory-verbal and visuospatial attention in trilingual individuals, in order to consider the effects these skills have on their overall language skills. They found that verbal WM predicted better linguistic performance for their sample. On the contrary, attention (as operationalised by Majerus et al., Reference Majerus, Heiligenstein, Gautherot, Poncelet and Van der Linden2009) was not a significant factor in explaining linguistic skills. In a 3-year longitudinal study, Blom (Reference Blom2019) assessed the role played by cognitive abilities (namely WM, selective attention, and executive attention) on HB children’s vocabulary knowledge. Vocabulary knowledge in L1 and L2 were tested at annual intervals for three consecutive years. After the first year, cognitive abilities turned out to be predictive of better vocabulary knowledge in both L1 and L2. This result remained stable in the following 2 years, especially concerning L2 vocabulary knowledge. Attentional skills were more useful in explaining vocabulary performance compared to WM.

Gangopadhyay et al. (Reference Gangopadhyay, Davidson, Weismer and Kaushanskaya2016) investigated the relationship between WM and morphosyntactic skills in English monolingual and Spanish-English bilingual children (with English as bilinguals’ L2). WM was measured through an N-back task, where participants were instructed to match the shape that appeared on the computer screen with shapes that they had viewed previously, and a Corsi block task in which the participant must tap the blocks that the experimenter shows in the same or reverse order. They found that nonverbal WM seems particularly relevant to predict bilinguals’ morphosyntactic processing in the language in which they were less proficient, namely their L2.

Phonological WM, usually tested by means of nonword repetition (NWR) tasks, is the process which involves storing phoneme information in a temporary, short-term memory store (Wagner & Torgesen, Reference Wagner and Torgesen1987). Particularly, NWR has been proven to be highly related to L2 acquisition since it is thought to mimic word learning (Gathercole, Reference Gathercole2006), involving temporary storage and retrieval of unique strings. Different basic cognitive and linguistic processes play a part in NWR: speech perception, phonological encoding, phonological memory, sequencing abilities, phonological assembly, oromotor skills, and articulation (Coady & Evans, Reference Coady and Evans2008). NWR is considered to be “less dependent on language knowledge and taps into more basic cognitive underpinnings of language, such as phonological processing and short-term memory” (Boerma et al., Reference Boerma, Chiat, Leseman, Timmermeister, Wijnen and Blom2015, p. 1747). Szwczyk and colleagues (2018) tested the properties of NWR to disambiguate the mechanisms that are responsible for children’s performance. They varied their list of nonwords according to several linguistic parameters such as word length, phonotactic probability, lexical neighbourhood, and phonological complexity. Their results demonstrate the primacy of sublexical representation and that these representations are phonological, unstructured, and insensitive to morphemehood.

Previous studies have found significant relationships between NWR task performance and vocabulary acquisition (Gathercole & Baddeley, Reference Gathercole and Baddeley1989; McDonald & Oetting, Reference McDonald and Oetting2019). Masoura & Gathercole (Reference Masoura and Gathercole1999) found close associations between phonological memory and vocabulary knowledge in both native and foreign languages. In addition, NWR is considered a good task for identifying developmental language disorders in bilinguals (Bonifacci, Lombardo, et al., Reference Bonifacci, Lombardo, Pedrinazzi, Terracina and Palladino2020; Ortiz, Reference Ortiz2021; Schwob et al., Reference Schwob, Eddé, Jacquin, Leboulanger, Picard, Oliveira and Skoruppa2021). On the other hand, NWR cannot be considered a “pure” cognitive task because it requires linguistic (i.e., phonological) knowledge. Furthermore, some degree of relationship with linguistic exposure may occur, although contrasting results are reported in the literature, also based on properties of NWR tasks, participants’ age and ways of measuring language exposure (see Farabolini et al., Reference Farabolini, Taboh, Ceravolo and Guerra2023). For the purpose of the present study, NWR was included as an index of children’s internal factors that might influence L1 and L2 skills, compared to other proximal or distal factors such as language exposure and SES.

Few studies have addressed the role of nonverbal reasoning (nonverbal IQ), which is known to be highly related to WM (Salthouse & Pink, Reference Salthouse and Pink2008), in predicting L2 acquisition. Some studies have found a relationship between nonverbal IQ and literacy skills, particularly spelling, in monolinguals (Rindermann et al., Reference Rindermann, Michou and Thompson2011; Zarić et al., Reference Zarić, Hasselhorn and Nagler2021) and bilinguals (Affranti et al., Reference Affranti, Tobia, Bellocchi and Bonifacci2024). Paradis et al. (Reference Paradis, Rusk, Sorenson Duncan and Govindarajan2017) found that, for children from migrant backgrounds, verbal WM and analytical reasoning scores were predictors of the number of complex English sentences produced, and Woumans et al. (Reference Woumans, Ameloot, Keuleers and Van Assche2019) reported that the rate of cognitive development, quantified as an increase in IQ, seemed to determine the pace of L2 learning. Haman et al. (Reference Haman, Wodniecka, Marecka, Szewczyk, Białecka-Pikul, Otwinowska, Mieszkowska, Łuniewska, Kołak, Miekisz, Kacprzak, Banasik and Forys´-Nogala2017) examined how SES, nonverbal IQ, working memory, and cumulative exposure to L1 and L2 related to vocabulary and grammar in bilingual Polish–English migrant children. Greater L1 exposure was linked to larger vocabulary and stronger phonological processing, whereas grammar was influenced by cognitive abilities rather than L1 exposure.

To sum up, previous evidence has underlined how the development of linguistic skills in L1 and L2 might be affected by a multi-layered set of factors (see Paradis, Reference Paradis2023), including interactions between L1 and L2 competences, proximal factors, such as exposure to both languages, distal factors such as SES, and children’s internal factors, including nonverbal IQ and phonological WM.

Even though many studies have evaluated each of these factors separately, far less evidence is available on how these domain-specific factors relate to one another in HB populations and on how their interactions shape linguistic outcomes across both languages. Only a limited number of studies have assessed both languages within groups characterised by heterogeneous linguistic backgrounds. This gap highlights the need for research that jointly examines these predictors and their effects across the two languages, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of heritage bilingual linguistic profiles.

1.3. Present study

The main aim of the study was to explore the relationships between home language exposure, nonverbal reasoning and phonological working memory (WM), and their linguistic skills in L1 and L2 (vocabulary and morphosyntactic abilities) in a sample of HB preschool children. In addition, before examining environmental and cognitive predictors, the study also aimed to investigate the relationship between vocabulary and morphosyntactic skills in both L1 and L2, based on previous literature on the interdependence hypothesis, which, as previously discussed, has reported mixed results. To address these objectives, receptive vocabulary and morphosyntactic comprehension tasks in L1 and L2 were included as linguistic variables. In addition, an expressive vocabulary task in L2 was considered. Regarding the predictors, two types of variables were considered: on the one hand, nonverbal reasoning and phonological WM, representing different aspects of cognitive and linguistic processes within children’s internal factors; on the other hand, socioeconomic status (SES) and language exposure, representing external (distal and proximal) factors. NWR was treated as a measure of phonological working memory rather than a language knowledge task (Boerma et al., Reference Boerma, Chiat, Leseman, Timmermeister, Wijnen and Blom2015) and is categorised as an internal factor in the model proposed by Paradis (Reference Paradis2023).

Our goal was to confirm previous evidence from the literature and possibly detect new insights considering that the present study was conducted in Italy, where less research has been carried out.

Two main research questions were at the root of the study:

-

1. The first RQ is aimed to test the relationship between vocabulary and morphosyntactic skills in L1 and L2. According to the interdependence hypothesis higher L1 competence is expected to be associated with better morphosyntactic skills in L2 (Soto-Corominas et al., Reference Soto-Corominas, Daskalaki, Paradis, Winters-Difani and Janaideh2021) although with a minor effect on vocabulary (Goodrich et al., Reference Goodrich, Lonigan, Kleuver and Farver2016). However, contrasting evidence was reported, with some authors reporting mainly within language relationships (e.g., Marchman et al., Reference Marchman, Martínez-Sussmann and Dale2004).

-

2. The second RQ aimed to evaluate the differential effects of external factors, specifically sociolinguistic background (linguistic exposure and SES) and internal cognitive-linguistic factors (i.e., nonverbal reasoning and phonological WM) on linguistic skills in L1 and the L2. We expect that SES might significantly influence vocabulary skills (Gatt et al., Reference Gatt, Baldacchino and Dodd2020; Golberg et al., Reference Golberg, Paradis and Crago2008; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Brouwer, de Bree and Verhagen2019), and that exposure in L1 and L2 can predict competency in the corresponding languages (Albirini, Reference Albirini2014; Chondrogianni & Marinis, Reference Chondrogianni and Marinis2011). We also predicted that individuals with higher nonverbal reasoning skills will be more proficient in morphosyntactic tasks (Gangopadhyay et al., Reference Gangopadhyay, Davidson, Weismer and Kaushanskaya2016; Haman et al., Reference Haman, Wodniecka, Marecka, Szewczyk, Białecka-Pikul, Otwinowska, Mieszkowska, Łuniewska, Kołak, Miekisz, Kacprzak, Banasik and Forys´-Nogala2017; Paradis et al., Reference Paradis, Rusk, Sorenson Duncan and Govindarajan2017; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Pratt, Durant, McMillen, Peña and Bedore2021). Furthermore, we expect nonverbal reasoning to have a different role from verbal WM (VWM). Indeed, we expect NWR to be mainly related to vocabulary knowledge and L2 linguistic skills (Gathercole & Baddeley, Reference Gathercole and Baddeley1989; Masoura & Gathercole, Reference Masoura and Gathercole1999; McDonald & Oetting, Reference McDonald and Oetting2019). Due to the lack of previous consistent results, understanding the differential role of SES, linguistic exposure, and children’s phonological WM and nonverbal reasoning skills on L1 and L2 competencies is an exploratory and original contribution of the present study.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The study involved 108 children recruited from public preschools where the Laboratory of the Assessment of Learning Disabilities (LADA), in collaboration with the Municipality of Bologna, was running the LOGOS project, which aims at assessing and developing bilingual students’ linguistic skills. Data were collected during the second year of preschool (mean age = 4.6 years old). School teachers interviewed children’s parents about their home linguistic environment and SES. The sample includes six different L1 speaking groups: Romanian (26.9%), Arabic (25.9%), Indo-Aryan languages (Urdu, Ceylonese, Bengali, 23.1%), Albanian (12%), Tagalog (6.5%), and Chinese (5.6%). The selection criteria were:

-

○ Exposure to an L1 other than Italian within the family context;

-

○ Having attended at least one full year of preschool;

-

○ Not having been diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental disorder or sensory or neurological impairment.

2.2. Materials

Interview with parents. School teachers interviewed parents using the QuBIL questionnaire from the BaBIL battery (Contento et al., Reference Contento, Bellocchi and Bonifacci2013); interviews were mainly conducted in Italian, but there was the possibility of using a linguistic mediator for families with very poor knowledge of Italian.

The questionnaire includes questions about parents’ education level and occupation, the languages the child speaks, length of exposure to Italian (“From what age has your child been continuously exposed to Italian?”; the age of exposure in months was then subtracted from the actual chronological age). The amount of exposure to L1 and Italian (L2) in the family environment was assessed by asking each parent to indicate, on a scale from 1 to 10, the proportion of time the child was exposed to L1 and L2. The values for each language provided by the mother and the father were then summed, resulting in a maximum possible score of 20 per language (score range: 0–20). The amount of exposure to L2 was therefore complementary to the amount of exposure to L1. For this reason, only the percentage of daily exposure time to L1 was considered in the analyses. To achieve a composite score for each child’s SES, information regarding parents’ education level and occupation was scored according to the Four Factor Index of Social Status (SES, Hollingshead, Reference Hollingshead1975), which attributes a score from 1 to 7 for educational level and a score from 1 to 9 for occupation. Then, the SES score for each parent was calculated using the formula (educational level*3 + occupation*5); the mean of the parents’ SES was used as the child’s SES.

Nonverbal reasoning. The Matrices subtest of the KBIT-2 (Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test – Second edition; Bonifacci & Nori, Reference Bonifacci and Nori2016; Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2004) was administered. The 46 items contain pictures and abstract designs and evaluate the ability to solve new problems by perceiving relationships and completing analogies. The test has different starting points based on the participant’s age and stops after four consecutive wrong responses. Raw scores (the maximum score was 46) were converted into standard scores. The split-half reliability coefficient in developmental age as per the Italian standardisation manual (4–18 years) was 0.87.

Phonological memory. The nonword repetition task from the learning difficulties indexes battery (IDA – Bonifacci et al., Reference Bonifacci, Pellizzari, Giuliano and Serra2015) was administered. Children were presented with a NWR task of eight nonwords: two 2-syllable, two 3-syllable, two 4-syllable, and two 5-syllable items. The NWR was based on the phonotactics of Italian; the phonetic repertoire included bilabial (/p/, /b/; alveolar /t/, /d/; velars /k/), fricatives (labiodental /f/, /v/; alveolar /s/), nasal (bilabial /m/; alveolar /n/); vibrants (/r/), palatal (/ʤ/); alveolar laterals (lateral: /l/), and vowels (/a/, /ɛ/, /e/, /i/, /ɔ/, /o/, /u/). Incorrect repetitions were scored 0. A score of 2 was given for perfectly repeated nonwords, and a score of 1 was assigned when an articulatory error (mispronunciation of the correct sound) was made. The total score ranged from 0 to 16, and the Cronbach’s α of the scale was .72.

Expressive vocabulary in L2. The expressive vocabulary task is part of the Learning Difficulties Indexes battery (IDA - Bonifacci et al., Reference Bonifacci, Pellizzari, Giuliano and Serra2015). Each child was presented with a series of pictures and was asked to name the object in the picture. The task included 36 images depicting objects and animals organised into three grids with 12 images each, whose corresponding words are increasingly less frequent in oral language (Burani et al., Reference Burani, Barca and Saskia Arduino2001). The accuracy score, ranging from 0 to 36 (1 point for each correct answer), was considered. The Cronbach’s α of the scale was .85.

Receptive vocabulary and morphosyntactic skills in L1 and L2. The BaBIL test (Contento et al., Reference Contento, Bellocchi and Bonifacci2013) is designed to assess children’s linguistic abilities in L1 and L2 using identical stimuli across languages. Tasks are computer-based with prerecorded audio instructions, and responses are given by pointing to images. L1 and L2 sessions were administered at least 2 weeks apart to limit learning effects. The test has been adapted into several minority languages with the support of native speakers and shows good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .86; Bonifacci, Atti, et al., Reference Bonifacci, Atti, Casamenti, Piani, Porrelli and Mari2020). For the present study, two tasks were administered:

-

- Receptive vocabulary (L1, L2). Each version includes 20 items. Children hear a word (e.g., feather) and select one of four corresponding images. Words were chosen based on age of acquisition (VARLEX database; Burani et al., Reference Burani, Barca and Saskia Arduino2001), imaginability, familiarity, and concreteness, with adjustments made for different languages by native speakers. Accuracy scores range 0–20.

-

- Morphosyntactic comprehension (L1, L2). Each version includes 20 items. Children listen to a sentence (e.g., Show me the image that shows more pens) and select one of four images. Items cover structures such as locatives, quantifiers, and cardinal numbers. Accuracy scores range 0–20.

2.3. Procedure

Parents signed the informed consent before participating in the project. The BaBIL tasks were administered individually in a quiet room at the children’s schools in two different sessions over a 2-week period. The other tasks were administered individually across two sessions. In the BaBIL task, the order of languages was counterbalanced across participants, while in the other tests the order of administration was counterbalanced. The study obtained the approval of the Bioethic Committee of the University of Bologna (Prot. 14170 del10/2/2017).

2.4. Data analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses and correlation matrices to examine relationships among variables and to select predictors while avoiding collinearity. Following Marchman et al. (Reference Marchman, Martínez-Sussmann and Dale2004), we analysed correlations between vocabulary and morphosyntactic skills within and across languages to guide model specification. Multivariate regressions tested the effects of sociolinguistic background, L1 exposure, nonverbal reasoning, and phonological working memory on L1 and L2 skills, with linguistic variables also entered as predictors of morphosyntactic skills based on RQ1 (see Results). A dominance analysis (lmg) was used to assess the relative weight of predictors. Regarding the sociolinguistic background, since L1 and L2 frequency of exposure showed specular values and given the moderate correlation between onset of L2 exposure and L2 frequency of exposure (r = −.46), we included only L1 frequency of exposure as a proxy for language dominance in order to avoid redundancy and collinearity. We also decided to exclude chronological age, given its non-significant correlations with the variables of interest (See the Supplementary materials section for the correlation matrix – A).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for all measures, along with reference values from the task manuals. Participants showed wide sociolinguistic variability, with SES scores ranging from 8 to 66 (M = 25.14, SD = 12.60). L1 and L2 exposure ranged from 0 to 20, with similar mean values, slightly lower for L1 (M = 13.07, SD = 5.94) than for L2 (M = 14.82, SD = 5.35), suggesting relatively balanced use of the two languages within families. Mean BaBIL scores were slightly below those reported in the manual. Competences were comparable in L1 and L2, though vocabulary was lower than morphosyntactic comprehension in both languages. As the task is designed to profile bilingualism rather than absolute ability, group means should be considered descriptive indicators rather than normative benchmarks. Finally, nonverbal IQ and phonological memory were in the medium range, while L2 expressive vocabulary was in the medium–low range.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

a Raw scores.

b Standard scores.

3.2. Research question 1: Linear regressions between competencies in L1 and L2

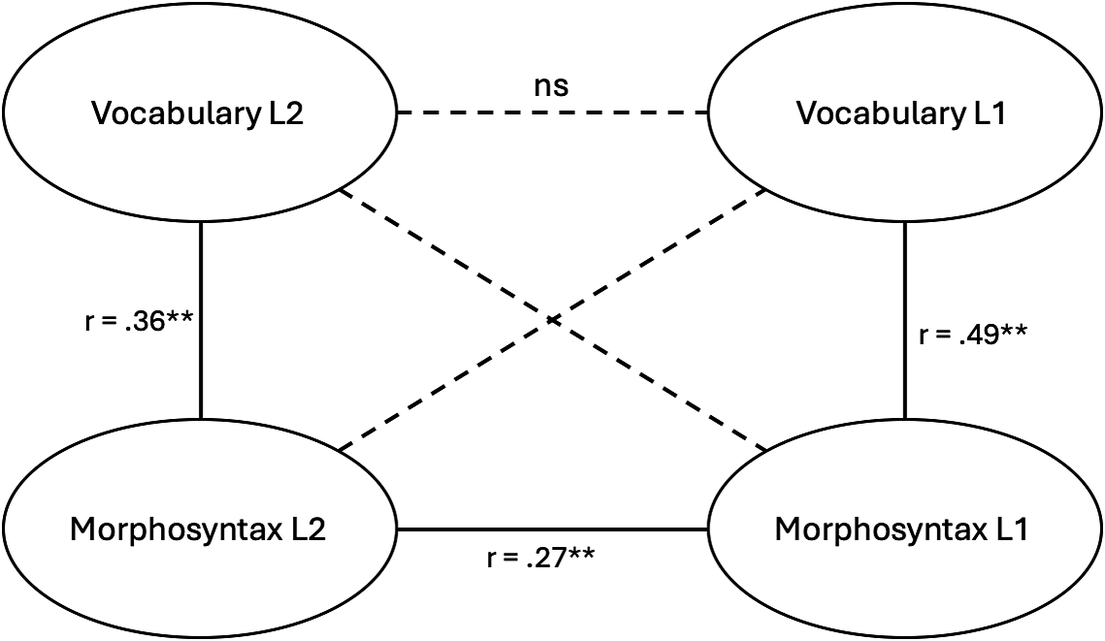

To explore the interdependence between vocabulary and grammar across languages, we conducted a set of analyses based on the framework proposed by Marchman et al. (Reference Marchman, Martínez-Sussmann and Dale2004) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Path model illustrating within- and cross-language associations between vocabulary and morphosyntactic skills in L1 and L2, based on the framework by Marchman et al. (Reference Marchman, Martínez-Sussmann and Dale2004). Solid lines represent significant relationships; dotted lines indicate non-significant paths. r Pearson are reported.

Significant correlations emerged within each language (Vocabulary L1 – Morphosyntax L1: p < .001; Vocabulary L2 – Morphosyntax L2: p < .001), and L1 morphosyntax was also related to L2 morphosyntax (p = .005). Cross-language associations involving vocabulary were not significant.

3.3. Research question 2: Multivariate regression on the relationships between sociolinguistic background, L1 exposure, children’s nonverbal reasoning, and phonological WM as predictors of linguistic skills in L1 and L2

We ran a multivariate regression including expressive vocabulary in L2, receptive vocabulary in L1 and in L2 and morphosyntax in L1 and in L2 as dependent variables (see Table 2). As independent variables we inserted SES, L1 exposure, NWR task, and the matrix task. Based on RQ1, predictors also included L1 receptive vocabulary for L1 morphosyntactic comprehension, and L2 receptive vocabulary plus L1 morphosyntactic comprehension for L2 morphosyntactic comprehension.

Table 2. Multivariate regression on the relationships between sociolinguistic background, L1 exposure, children’s nonverbal reasoning, and phonological WM as predictors of linguistic skills in L1 and L2

Note: Significance levels: *** = p < .001 ** = p < .01 * = p < .05. = trend towards significance.

Concerning expressive vocabulary (L2), it was negatively predicted by L1 exposure (p < .001) and positively predicted by NWR task (p < .05). The model explained 19% of the variance (R 2 = .19). Dominance analysis revealed that L1 exposure was the most important variable with a lmg = .114. Concerning L1 receptive vocabulary, only SES was significant (p < .05). The model explained 8% of the variance (R 2 = .08). Dominance analysis confirmed the most prominent role of this variable above all the others, with a lmg = 0.039. As regards L2 receptive vocabulary, L1 exposure (p < .05) and nonverbal reasoning were significant (p < .01), with negative and positive relationships, respectively. Dominance analysis revealed a relative stronger role of nonverbal reasoning (lmg = .073) compared to L1 exposure (lmg = .049). The model explained 14% of the variance (R 2 = .14). In relationship to L1 morphosyntax, receptive vocabulary in L1 (p < .001), SES (p = .007), and L1 exposure (p = .040) were significant predictors. The model explained 31% of the variance (R 2 = .31). Dominance analysis revealed that receptive vocabulary in L1 was the most prominent predictor, with a lmg = .198, followed by SES (lmg = .063) and L1 exposure (lmg = .032). Finally, concerning L2 morphosyntax, performance was significantly predicted by non-verbal reasoning (p = .006), phonological working memory (NWR) (p = .011), receptive vocabulary in L2 (p = .005), and morphosyntactic comprehension in L1 (p = .008). The model accounted for 32% of the variance (R 2 = .324). Dominance analysis revealed that matrices (lmg = .092) and L2 vocabulary (lmg = .091) were the strongest predictors, followed by NWR (lmg = .067) and L1 morphosyntax (lmg = .061).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to understand how different determinants of bilingual linguistic development were related to linguistic competence in L1 (heritage language) and in L2 (Italian) in a heterogeneous group of HB children attending preschool. More specifically, with reference to Paradis’ model (Paradis, Reference Paradis2023) we included distal and proximal factors, namely sociolinguistic background measures (linguistic exposure in the home context, SES), and children’s internal factors, namely nonverbal reasoning and phonological WM skills. Descriptive statistics showed that children in the study had average nonverbal reasoning and phonological memory skills, relatively balanced L1 and L2 competences and exposure, slightly lower performance than norm-referenced values on linguistic tasks, and a medium–low average SES.

4.1. Research question 1

The first research question aimed to evaluate the relationships between vocabulary and morphosyntactic skills in L1 and L2, replicating the model proposed by Marchman et al. (Reference Marchman, Martínez-Sussmann and Dale2004). Consistent with this model, we found relationships between vocabulary and morphosyntax within each language. However, unlike Marchman et al. (Reference Marchman, Martínez-Sussmann and Dale2004), our study also revealed a cross-linguistic relationship between morphosyntactic skills in L1 and L2. At the same time, the results confirmed the absence of relationships between vocabulary across the two languages, as well as between vocabulary and morphosyntax across languages. Thus, the results confirm a strong continuity between vocabulary and morphosyntax in language learning trajectories, while also suggesting that morphosyntactic skills in the heritage language may provide a foundation for the development of morphosyntactic skills in L2. It is also important to note that the differences from the previous study may be due to methodological factors, as Marchman et al. (Reference Marchman, Martínez-Sussmann and Dale2004) collected data through parent reports, whereas the present study used objective tasks in both L1 and L2. This pattern of results seems to align with the interdependence continuum hypothesis of Proctor et al. (Reference Proctor, August, Snow and Barr2010), which holds that the relationship between L1 and L2 skills might vary as a function of the differences between the specific grammatical and lexical features of the languages involved.

Therefore, Cummins’ interdependence hypothesis (Cummins, Reference Cummins1979) seems to be supported for morphosyntactic skills, which might involve a “common underlying proficiency,” that is, a shared linguistic knowledge (i.e., metalinguistic skills) that enables a transfer process across languages. Conversely, as Goodrich et al. (Reference Goodrich, Lonigan, Kleuver and Farver2016) found, the transfer might be less prominent for vocabulary skills. It is also fundamental to underline that the linguistic distance between two spoken languages might play a role. Levenshtein distance (Yarkoni et al., Reference Yarkoni, Balota and Yap2008) could provide information concerning this point: it is an index of orthographic similarity between languages that can be derived by measuring how many letters change from a word in a specific language and its translation equivalent. It has been demonstrated that Levenshtein distance is low for Romance languages (Schepens et al., Reference Schepens, Dijkstra and Grootjen2012), possibly favouring transfer processes. Differently, romance languages and, for example, Indo-Iranian languages do not share common ancestors and therefore have less cognates and cross-linguistic similarities, making their lexical distance higher (Serva & Petroni, Reference Serva and Petroni2008). In such cases, vocabulary can be considered a surface feature of L2 knowledge that needs to be learned through adequate exposure and education and might benefit less from linguistic transfer.

Another possible explanation for the absence of significant relationships between vocabulary and morphosyntax in L1 and L2 at this stage is that these associations may evolve over time. Factors such as the amount, duration, and richness of linguistic exposure could shape the emergence of cross-linguistic relationships gradually, rather than being evident early in development. This perspective highlights the need for longitudinal studies to examine how these relationships change with increased bilingual experience and schooling, as “common proficiency” may consolidate progressively rather than being fully established in the preschool years.

Further studies that take linguistic distance into account are necessary to better understand the level of interaction between L1 and L2 skills.

4.2. Research question 2

Concerning the second question, aimed at evaluating the differential role of sociolinguistic background and children’s internal factors (nonverbal reasoning and phonological WM skills) in L1 and L2 competencies, we ran a multivariate regression including expressive vocabulary in L2, receptive vocabulary in L1 and in L2 and morphosyntax in L1 and in L2 as dependent variables. As independent variables we inserted SES, L1 exposure, NWR task and the matrix task. Based on RQ1, predictors also included L1 receptive vocabulary for L1 morphosyntactic comprehension, and L2 receptive vocabulary plus L1 morphosyntactic comprehension for L2 morphosyntactic comprehension.

As regards predictors related to the sociolinguistic background, L1 linguistic exposure was positively associated with morphosyntax in L1 but showed detrimental effects on L2 productive and receptive vocabulary, for which it was the main negative predictor, in line with the findings of Haman et al. (Reference Haman, Wodniecka, Marecka, Szewczyk, Białecka-Pikul, Otwinowska, Mieszkowska, Łuniewska, Kołak, Miekisz, Kacprzak, Banasik and Forys´-Nogala2017). This suggests that rich exposure to L1 in the family environment fosters morphosyntactic development in that language, while the acquisition of expressive vocabulary in L2 may follow at a later pace, reflecting a natural trajectory in early bilingual development. SES emerged as a positive predictor of vocabulary and morphosyntactic skills in the heritage language, while it did not appear to influence the emergence of language skills in the societal language. This result seems consistent both with our hypothesis and with the literature affirming that SES relates to linguistic skills in bilinguals (Hoff, Reference Hoff2013), considering vocabulary and morphosyntactic skills (Dicataldo & Roch, Reference Dicataldo and Roch2020). However, partially in contrast with Gatt et al. (Reference Gatt, Baldacchino and Dodd2020), the effect is limited to L1, that is, the linguistic input received within the family context. It may be that the linguistic input at home might be sensitive to parents’ level of education (Sorenson Duncan & Paradis, Reference Sorenson Duncan and Paradis2020) and thereafter affect children’s linguistic skills in L1. However, exposure to L2 mainly relies on linguistic input from contexts outside of the family, primarily the school environment. It may, therefore, be suggested that the school context might act as a protective factor that helps reduce the effects of SES disparities. It should also be noted that the study by Gatt et al. (Reference Gatt, Baldacchino and Dodd2020) was conducted in the very different sociolinguistic context of Malta, where two societal languages coexist. Cross-linguistic and cross-country comparisons would be useful in disentangling the role of context in L1–L2 relationships.

With regard to children’s internal factors, nonverbal reasoning was the strongest predictor of L2 skills, particularly receptive vocabulary and morphosyntax, while for expressive L2 vocabulary only a trend was observed (p = .06). In contrast, no significant effects emerged for the heritage language. The role of phonological working memory was significant for expressive vocabulary and morphosyntax in L2, although it never emerged as the primary predictor. Previous studies have already highlighted the role of cognitive skills, such as WM and executive functions, in L2 acquisition (Bouffier et al., Reference Bouffier, Barbu and Majerus2020), for both vocabulary acquisition (Blom, Reference Blom2019) and morphosyntactic skills (Gangopadhyay et al., Reference Gangopadhyay, Davidson, Weismer and Kaushanskaya2016). However, these studies have scarcely investigated the role of nonverbal reasoning, a higher-order cognitive index involving cognitive operations such as concept acquisition, decision-making, and inductive reasoning, as in Levine (Reference Levine, W. B., A. C., E. R., H. M. and M. D.2009). This pattern of results appears to contrast, at least in part, with the findings of Haman et al. (Reference Haman, Wodniecka, Marecka, Szewczyk, Białecka-Pikul, Otwinowska, Mieszkowska, Łuniewska, Kołak, Miekisz, Kacprzak, Banasik and Forys´-Nogala2017), who reported an effect of nonverbal reasoning on grammatical skills in the heritage language (Polish). By contrast, the present study found SES and L1 exposure to be the main predictors for the heritage language. However, as Haman et al. (Reference Haman, Wodniecka, Marecka, Szewczyk, Białecka-Pikul, Otwinowska, Mieszkowska, Łuniewska, Kołak, Miekisz, Kacprzak, Banasik and Forys´-Nogala2017) did not examine L2 (English) skills, their study cannot exclude a potential role of cognitive abilities in L2 acquisition. Although this area remains relatively underexplored, some evidence indicates that nonverbal reasoning may particularly support L2 learning when considered alongside phonological working memory (Affranti et al., Reference Affranti, Tobia, Bellocchi and Bonifacci2024; Woumans et al., Reference Woumans, Ameloot, Keuleers and Van Assche2019). Given the strong associations between nonverbal reasoning and several subdomains of working memory (McGrew, Reference McGrew2009), future research should consider this factor together with phonological memory. In particular, NWR, as an index of phonological short-term memory, may play an additional role in L2 learning, as suggested by studies identifying NWR as a sensitive marker of Developmental Language Disorder (Bonifacci, Atti, et al., Reference Bonifacci, Atti, Casamenti, Piani, Porrelli and Mari2020; Ortiz, Reference Ortiz2021; Schwob et al., Reference Schwob, Eddé, Jacquin, Leboulanger, Picard, Oliveira and Skoruppa2021).

Finally, building on the correlations outlined in Marchman’s model, the present study also considered linguistic skills themselves – particularly morphosyntax and vocabulary – as predictors rather than solely as outcomes. This approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of the relative weight of these skills in relation to sociolinguistic background and cognitive factors, and helps to clarify whether the roles of the previously discussed sociolinguistic and cognitive variables remain robust. With respect to morphosyntactic skills in the heritage language, vocabulary in the same language emerged as the strongest predictor; however, it did not alter the relative weight of other factors, with SES and L1 exposure remaining significant predictors. A similar pattern was observed for morphosyntax in L2, where L2 vocabulary was a significant predictor, but without diminishing the primary role of nonverbal reasoning. In addition, L1 morphosyntactic comprehension continued to play a supportive role, as previously discussed, suggesting an interdependence effect. Nonetheless, this did not reduce the additional contribution of phonological memory. These findings confirm the differential role of sociolinguistic variables as primary predictors of language development in the heritage language and of cognitive and core linguistic variables as primary predictors of acquisition in the societal language. The analysis of the full model also reinforces the strong link between lexical and morphosyntactic development within each language, as well as an interdependence effect of morphosyntax across L1 and L2.

Overall, these results reveal the importance of external factors such as language exposure and sociolinguistic context for L1 development (Paradis, Reference Paradis2023). At the same time, the influence of internal factors such as nonverbal reasoning and, to a lesser degree, phonological working memory, emerged to play a pivotal role in L2 acquisition. These results are in line with Paradis’ model (2023) and reinforce the importance of investigating the differential role of children’s internal proximal and distal factors in shaping L1 and L2 development. With respect to Cummins’ Common Underlying Proficiency theory (1979), the findings of the present study align more closely with the interdependence continuum hypothesis proposed by Proctor et al. (Reference Proctor, August, Snow and Barr2010), showing cross-linguistic (L1–L2) relationships for morphosyntactic skills but not for vocabulary. This suggests that the common linguistic competence underlying language acquisition operates primarily at the sentence level, where linguistic, metalinguistic, and cognitive processes interact, rather than at the lexical level, which appears to be more closely tied to surface-level knowledge and highly dependent on both proximal and distal environmental factors.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the results show a multifaceted relationship between SES, linguistic exposure, children’s nonverbal reasoning and phonological WM, and linguistic competence in L1 and L2. Cross-linguistic relationships were found for morphosyntactic skills but not for vocabulary. Home exposure was linked to competence in the corresponding language (e.g., higher L1 exposure predicting stronger L1 skills), with some negative effects on the other language; family language use was also often unbalanced towards one language. Two novel findings emerged: sociolinguistic background strongly influenced L1 competence (vocabulary and morphosyntax), while nonverbal reasoning and phonological WM had a major impact on L2 morphosyntactic skills and, to some extent, on L2 receptive vocabulary.

This study has several limitations. First, we examined only concurrent predictors, whereas longitudinal data would better capture developmental trajectories and causal effects. Second, no measures of executive functions were included, despite evidence of their role in L2 acquisition, though with mixed results. Third, expressive language in L1 was not assessed, and phonological WM was measured with an Italian standardised NWR task rather than a quasi-universal one (Boerma et al., Reference Boerma, Chiat, Leseman, Timmermeister, Wijnen and Blom2015), which may have inflated associations with Italian skills. In addition, L1 measures did not ensure full equivalence in word frequency and syntactic complexity across languages, although the use of native speakers in adaptation and the heterogeneity of the sample help mitigate this issue. Methodologically, the study relied on parental ratings of L1 and L2 use. Other parameters such as timing, input quality, interlocutors, and caregiver time were not captured, and previous studies report discrepancies between parental reports and direct observations (De Houwer & Bornstein, Reference De Houwer and Bornstein2016; Marchman et al., Reference Marchman, Martínez, Hurtado, Grüter and Fernald2016). Thus, estimates of exposure may be less precise, and information such as sibling interactions is missing. Finally, analyses did not account for specific language pairings, which limited a finer evaluation of the interdependence continuum hypothesis (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, August, Snow and Barr2010). Future studies should include detailed assessments of cognitive functions and direct comparisons across language groups to better clarify the effects of linguistic history, language distance, and cognitive skills on heritage bilingual children’s competencies.

Despite these limitations, the present study has highlighted some original contributions with respect to previous literature, as discussed, and might have some implications for research and educational settings. On the one hand, it would be important to consider not only language exposure but also the role of family language policy (King et al., Reference King, Fogle and Logan-Terry2008) when studying heritage bilinguals (Borghetti et al., Reference Borghetti, Cangelosi and Bonifacci2025; Curdt-Christiansen, Reference Curdt-Christiansen2016) in shaping language acquisition trajectories. On the other hand, the significant role of sociolinguistic background underlines the relevance of making parents aware of the importance of providing enriched linguistic input in the heritage language. It is important to underline that our results are consistent with literature addressing the fact that SES is better viewed as a structural variable related to the family’s circumstances and not as an inherent characteristic of the family itself (Hannon et al., Reference Hannon, Nutbrown and Morgan2020). Therefore, the impact of SES should not be considered from a deterministic perspective but can be modulated by other social and family characteristics (Bonifacci et al., Reference Bonifacci, Compiani, Affranti and Peri2021).

Overall, the impact of sociolinguistic background on L1 language development cannot be minimised in view of subsequent stages of schooling: linguistic exposure and SES pave the way for HB children to exploit their repertoires fully while engaging with the language of schooling and its high academic and cognitive demands (Beacco et al., Reference Beacco, Byram, Cavalli, Coste, Cuenat, Goullier and Panthier2016; Cummins, Reference Cummins1979). In other words, while some detrimental effects on actual L2 development have been identified when children are highly exposed to L1, it is foreseeable that this phenomenon will be compensated for in a future when these pupils, fully equipped with their L1 resources, will engage with the language of schooling. It must also be underlined that, when working with bilinguals, it is important to keep a perspective beyond that of expecting full adequacy in both languages (Flores & Rosa, Reference Flores and Rosa2015). To sum up, bilingual development needs to be supported by a broad perspective that includes families, schools, and children, considering the complex interaction between environmental variables and children’s internal factors in shaping language competence.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000925100457.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Municipality of Bologna for supporting the implementation of the research in preschools within the LOGOS project. We also wish to thank the teachers, the children, and their families who took part in the study. Finally, we are grateful to the reviewers, whose valuable suggestions helped improve the quality of this manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare none.