Published a decade ago, Kintigh et alia’s (Reference Kintigh, Altschul, Beaudry, Drennan, Kinzig, Kohler and Limp2014) article set out to define some of the grand challenges of archaeology. The challenges they identified focused on understanding issues related to human–natural systems, collapse, social inequality, and conflict in culture change, among others (see Kintigh et al. Reference Kintigh, Altschul, Beaudry, Drennan, Kinzig, Kohler and Limp2014). The largely scientific and anthropologically centered research domains that Kintigh and colleagues (Reference Kintigh, Altschul, Beaudry, Drennan, Kinzig, Kohler and Limp2014) identified were and still are important (e.g., climate change and population dynamics). However, missing from this original article was a concern with both the historical and political roles—in a contemporary sense—that archaeology plays, with a particular emphasis on materiality in understandings of the past (Cobb Reference Cobb2014). Cobb’s (Reference Cobb2014) critique of the grand challenges of archaeology is perhaps more important than ever in North American archaeology, given that over the last decade, the discipline has seen the revision of Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) regulations, a greater degree of collaboration among archaeologists and Tribes in research, and the emergence of comanagement of ancestral cultural sites, including ones within the National Park System. And although federally recognized Tribes certainly have an interest in the classic grand-challenge questions outlined by Kintigh and colleagues (Reference Kintigh, Altschul, Beaudry, Drennan, Kinzig, Kohler and Limp2014), many of their core values with regard to NAGPRA and the management of cultural sites and the presentation of Native American history align with an archaeology in which history is placed front and center in research. Specifically, such works aid in the NAGPRA process regarding cultural affiliation, and they help to establish the history of certain Tribal institutions over long periods of time. They also provide guidance on the presentation of Tribal histories to non-Native populations.

Recently, Birch et alia (Reference Birch, Hunt, Lesage, Richard, Sioui and Thompson2022) published an article authored by both archaeologists and Tribal members that makes the case that radiocarbon dating can be one of the most productive avenues by which archaeologists can play a role in advancing Indigenous-led research. Although based in Western science, radiocarbon dating can fundamentally provide a way to anchor events in Indigenous histories in deep time. One of the key research agendas for the Muscogee Nation centers on the history of Tribal Towns (Birch et al. Reference Birch, Hunt, Lesage, Richard, Sioui and Thompson2022:4). Tribal Towns not only are physical places, which are relocated from time to time, but also form part of the core identity of Muskogean-speaking peoples and Nations (Birch et al. Reference Birch, Hunt, Lesage, Richard, Sioui and Thompson2022). One of the critical interests of the Muskogean-speaking peoples and Nations is the specific histories of these towns, including their migrations, their relocation across the ancestral landscape, and the way they interacted in deep time in terms of governance (Birch et al. Reference Birch, Hunt, Lesage, Richard, Sioui and Thompson2022).

Here, we present our initial collaborative research on the redating of Ocmulgee Mounds National Historic Park (OMNHP; Figure 1). Specifically, our dating program at this Traditional Cultural Place (TCP) was designed to address some of the fundamental questions that the Muscogee Nation has regarding OMNHP. Although archaeology had been carried out on a massive scale during the Works Progress Administration (WPA; and other federal programs) era in the 1930s, its chronological resolution was coarse at best, resulting in the weakly supported dating of specific events reported in park signage, public-facing interpretation, and broader published academic debates about migration histories (National Park Service 2023:2). The Muscogee Nation perceived this lack of chronological certainty regarding some of the public architecture at OMNHP as a question that required further work because the mounds are the center of the capital of their ancestral homelands (Harris Reference Harris1935; Mason Reference Mason2005). Consequently, the impetus and idea for this work originated from Muscogee Nation and not from the collaborating archaeologists. These collaborations, however, were born of us working together on a variety of other initiatives, including collaborative archaeology field schools and NAGPRA work (see Roberts Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Amanda, Thompson, Garland, Butler, deBeaubien, Panther and Hunt2023).

Figure 1. Location of Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park (OMNHP) in the American Southeast in the United States (Image courtesy of Carey Garland and the Unviersity of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology). (Color online)

We contextualize our initial dating research in the broader political and historical concerns of archaeology—those of both the past and the present. Specifically, we use our new chronological understanding to evaluate three core questions regarding OMNHP:

1. What is the history of public buildings and architecture at these various sites, especially those that focus on communal and cooperative governance (i.e., council houses / earth lodges)?

2. To what extent do the new chronologies support ideas regarding recent migrations as opposed to deeper histories?

3. To what extent do the new chronologies support ideas regarding abandonment?

Chronological information about each of these questions speaks to long-held beliefs by archaeologists regarding the history of “Creek” people in the region and their connection to OMNHP. Furthermore, this work also informs how the National Park Service moves forward in communicating interpretations at OMNHP. Finally—and perhaps most importantly—many Muskogean-speaking peoples and Nations are deeply involved in the management of OMNHP and their connection to their ancestral lands in general, and these questions serve as a key anchor for the broader Native American histories of the American Southeast.

Archaeologists have long recognized OMNHP as one of the Muscogee Tribal Towns known as Ocmulgee Old Fields (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks2003; Harris Reference Harris1935; Mason Reference Mason2005). However, few have connected this later “historically” documented town to the people who constructed the earthen architecture and public buildings for which OMNHP is well known (see Supplementary Material 1). In fact, archaeologists and historians largely argue that there is a disconnect between the people who occupied the “historic town” and those earlier inhabitants who constructed the mounds, citing both an abandonment and then an immigration to the area in the 1680s (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks2003:48–49; Knight Reference Knight and Hally1994:191; Williams Reference Williams and Hally1994:137). This belief, which is largely based on assumptions regarding ceramic chronologies, has had present-day implications for NAGPRA efforts and repatriation. For example, the Smithsonian Institution, which is not subject to the same NAGPRA rules and law as other museums, held Ancestors who had been removed from one of the mounds in the core area of OMNHP. Only a subset of these Ancestors were deemed culturally affiliated by the National Museum of Natural History and repatriated to Muscogee Nation and affiliate tribes.

Significantly, our research questions and the interests of the Muscogee Nation align easily with the contemporary goals of anthropological archaeology, and in the American Southeast specifically (see Anderson and Sassaman Reference Anderson and Sassaman2012). Issues related to migration and political organization have been central themes in American Southeast research for more than a hundred years. In fact, there has been both a renewed focus on migration research (Pluckhahn et al. Reference Pluckhahn, Wallis and Thompson2020; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Smith, Meeks and Patch2024) and work centering on collective governance and its historical trajectory (Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Holland-Lulewicz, Butler, Hunt, Wendt, Wettstaed, Williams, Jefferies and Fish2022). Therefore, the interest of Tribal Nations and anthropological archaeology in certain contexts concatenate and make for a strong program of investigation when both are given footing in research implementation.

Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park

Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park, located in Macon, Georgia, is both one of the most iconic cultural sites in the American Southeast and a TCP of the Muscogee Nation and related Tribal Nations, and it was developed in direct consultation with these federally recognized Tribal Nations. OMNHP often plays a prominent role in cultural history summaries and research on the post–AD 1000 era in the region (e.g., Anderson and Sassaman Reference Anderson and Sassaman2012). During the WPA (as well as other federal programs) of the 1930s and 1940s, the Macon Plateau was the subject of one of the largest archaeological projects in the history of the United States, employing over 800 people in the excavations. This early work (1933–1941) revealed a complex network of earthen monuments, ridge and furrow agricultural fields, and house structures, among other cultural features (Hally and Williams Reference Williams and Hally1994). The most visible of these include eight mounds—the largest of which is known as the “great temple mound”—and a large building known as the “earth lodge” (referred to here as the Earthlodge; Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1946).

Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park is split into three different sections: the North Plateau, South Plateau, and Middle Plateau (Kelly Reference Kelly1938; Figure 2). These designations, however, are arbitrarily defined with respect to modern features largely created by the massive railroad cuts that crossed the site first in 1843, and then again in 1873, when they relocated the line (Andrews and Collings Reference Andrews and Collings2014; Butler Reference Butler1958). For continuity, we continue to use these designations, but we stress that large portions of the community as an integrated whole are missing due to this destruction. Currently, OMNHP covers more than 809 ha (2,000 acres); however, this is only a portion of the related sites, which likely extend outside its current boundaries (Williams Reference Williams2022). If we consider the large sections of the park that were destroyed by the railroad, this constitutes the largest Indigenous archaeological site within the state of Georgia today. Yet, despite almost a century of investigations, our knowledge of the community that founded Ocmulgee and its history remains coarse-grained when compared to other major mound centers in the state and region of the same time frame (i.e., AD 1000–1700; Bigman Reference Bigman2012; Birch et al. Reference Birch, Lulewicz and Rowe2016; Hally and Chamblee Reference Hally and Chamblee2019; Holland-Lulewicz et al. Reference Holland-Lulewicz, Thompson, Wettstaed and Williams2020; Lulewicz Reference Lulewicz2019).

Figure 2. Lidar hillshade map showing the major subsections and architectural features at Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park.

Part of the reason that archaeologists know so little about the history of Ocmulgee is that for the past 90 years, interpretations have hinged on chronologies derived from shifts in ceramic styles, which in turn were anchored by only a few radiocarbon dates (see Bigman [Reference Bigman2012] for a discussion of ceramic chronologies for the region). Although ceramic and other artifact chronologies provide gross time estimates, they are imprecise, and in some cases, completely inaccurate. Consequently, the application of more precise dating techniques is critical to writing detailed narrative histories that link past actions and communities to the present. Previous to this research, there were only two published radiocarbon dates from Ocmulgee relating to its occupation before the arrival of Europeans (Wilson Reference Wilson1964). Both were run in the 1960s, when the dating method was still in its nascent stages of development, and both have large error ranges (Wilson Reference Wilson1964). One date was run on roof timber from the Earthlodge (935 ± 110), calibrating to AD 1020–1220 (68% probability) or AD 885–1280 (95% probability); the other is from House A (1040 ± 115), calibrating to AD 885–1160 (68% probability) or AD 700–1225 (95% probability). Simply put, we will not understand Ocmulgee until we understand the relationship between public architecture and community history with at least generational-scale precision. New research employing massive numbers of radiocarbon dates and complex statistical analysis is rewriting many long-held beliefs regarding Native American history in the Eastern Woodlands (Birch et al. Reference Birch, Manning, Sanft and Conger2021; Cobb et al. Reference Cobb, Krus and Steadman2015; Manning et al. Reference Manning, Birch, Conger, Dee, Griggs, Hadden and Hogg2018; Pluckhahn and Thompson Reference Pluckhahn and Thompson2018; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Jefferies and Moore2020, Reference Thompson, Smith, Sanger, Garland, Pluckhahn, Napora and Bedell2024).

Here, we present the initial results of a collaborative research project between the Muscogee Nation, the University of Georgia, and the National Park Service to radiocarbon date the public architecture and assess the settlement history of OMNHP. Specifically, our initial research centers on (1) understanding the timing of the Earthlodge and related structures (i.e., council houses) and (2) developing a broader radiocarbon-dating program aimed at understanding and evaluating the site’s occupational sequence, especially as it relates to archaeological narratives of abandonment versus cultural continuity.

The Earthlodge and Council Houses

The Earthlodge (also referred to as Mound D-1) is located in the North Plateau section of the site. It is the most well-known public structure at Ocmulgee, and it was excavated by archaeologists in 1934. It is a massive circular structure approximately 14 m in diameter, with a large central hearth that was once covered with an earth mantle. Around the circumference of the structure was a low clay bench consisting of molded seats with small basins in front of each. In total, there were 23 seats on the northern side and 24 on the southern side (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1946:95; Figure 3). In addition to the benches on the western end, there is a large platform constructed in the shape of a raptorial bird (e.g., peregrine falcon, American kestrel, etc.), which held an additional three seats and basins (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1946:95–96). In addition to being of distinct cultural importance to the Muscogee Nation and other Muskogean-speaking peoples and related federally recognized Tribal Nations, this structure has captured the imagination of multiple generations of visitors to the park. Reconstructed shortly after its excavation, it is one of OMNHP’s main attractions for the general public; visitors can still view the floor as it was originally excavated in the 1930s. Interestingly, when the air conditioning unit was installed in the exhibit portion of the reconstructed Earthlodge in 1974, one of the authors (Mark Williams) was there to monitor its installation. He observed a burned layer under the visible floor, which suggested that there may have been an earlier iteration of this structure in the same spot.

Figure 3. Ocmulgee Earthlodge: (A) Mound D-1 Earthlodge excavations; (B) pedestalled roof beans from the Mound D-1 excavations; (C) Council Chamber 2 excavations showing outline and central pit feature. Drawing of the Mound D-1 Earthlodge showing its major features. Note the cane entrance way. (Redrawn and adapted from Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1946:Figure X). (Image courtesy of Victor D. Thompson and the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology).

Interpreted as a communal structure important to collective governance (i.e., council house; Larson Reference Larson and Hally1994:108), the Earthlodge bears many similarities to buildings described in archaeological literature and early historic documents as structures that integrated wide sections of society (Foster Reference Foster2007; Shapiro and Hann Reference Shapiro, Hann and Thomas1990; Thompson Reference Thompson2009). Sixteenth-century documents suggest that the interiors of these buildings were highly structured, with arranged seating and histories painted on the walls (Shapiro and Hann Reference Shapiro, Hann and Thomas1990:512)—as is the case in the Earthlodge, but it is not the only structure at the site that fits this description. Fairbanks identified at least seven such structures on both the North Plateau and South Plateau that could also be described this way, and at least four of them (including Mound D-1) were paired with a platform mound roughly 30 m to the southeast (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1946:106; Hally and Williams Reference Williams and Hally1994:89; see Figure 2).

Hally and Williams (Reference Williams and Hally1994:89) provide a succinct description of the lodges at OMNHP. They state that the other lodges do not have “all the architectural characteristics of the Mound D-1 Lodge” and none “have the interior platform opposite the entrance.” They do point out that “two have peripheral seats,” suggesting a similarity in style to Mound D-1 (Hally and Williams Reference Williams and Hally1994:89). As they note, Fairbanks suggested that this variability may be an evolution of style of these buildings; however, they believe that some of the variation can be explained by incomplete excavations or later destruction, and it is possible that in some cases they may have been functionally different (Hally and Williams Reference Williams and Hally1994:89).

It is unclear why the inhabitants of Ocmulgee constructed so many large public buildings. Fairbanks (Reference Fairbanks1946:101) considered these structures as reflecting the evolution over time of an architectural form, with the elaborate construction of the Mound D-1 Earthlodge as the end form. Hally and Williams (Reference Williams and Hally1994:89) are skeptical of this interpretation; they believe that, in part, incomplete excavation would have revealed similar features for some, and that perhaps a few of the others are different kinds of structures altogether. Without a robust chronology for these structures, however, we cannot say if these buildings are ancestral forms, as Fairbanks suggested, or were perhaps the community buildings of subsections of the Ocmulgee population, as hypothesized by Hally and Williams (Reference Williams and Hally1994:94).

Understanding the Broader Occupational History of OMNHP

To begin to evaluate if there were any breaks in the occupational history of OMNHP—specifically, the perceived disconnect between the precontact and “historic” Creek occupation as it is described in the literature—we focused part of our research program on the Middle Plateau section. The Middle Plateau provides an opportunity to examine the occupational history of the site and offers three distinct advantages for a radiocarbon-dating program geared toward Bayesian analysis (see below). The first advantage is that based on material culture from excavations, we believe that people occupied this particular area of the settlement not only for a long period of time but during the general time frame that the earthworks were constructed and in frequent use (Hally and Williams Reference Williams and Hally1994). Second, there are historic documents, as well as archaeological evidence, that point to the area being the location of Ocmulgee Town during the late 1600s and early 1700s (Hammock Reference Hammock2018:36; Mason Reference Mason2005). Finally, the excavations during the WPA that Mason (Reference Mason2005) subsequently wrote up for her dissertation provide details for the location of a large number of features in this area—including structures, walls, ditch, and pits—associated with the “Macon Trading House” (Mason Reference Mason2005; Waselkov Reference Waselkov and Hally1994). The Macon Trading House was in use sometime between AD 1702 and 1715 when it was burned during the Yamasee War (Waselkov Reference Waselkov and Hally1994), thereby providing definitive temporal constraints for the features associated with the house, along with an end point (i.e., terminus ante quem; TAQ) for the features underlying the house.

Based on what we have outlined above, we know that “Creek” people occupied the Middle Plateau before and up to the abandonment of the Macon Trading House, after which they moved to other sites in the valley (Waselkov Reference Waselkov and Hally1994). In fact, there should have been considerable population growth in the area as Tribal Towns moved away from Spanish-occupied regions. Consequently, a targeted radiocarbon-dating program of this area provides at the very least a starting point from which to evaluate if there were gaps in the central area of OMNHP along the Middle Plateau.

Methods and Materials

To understand the chronology of OMNHP, we traveled to both OMNHP in Macon, Georgia, and the National Park Service Southeast Archeological Center in Tallahassee, Florida, to select radiocarbon samples from the WPA collections held at these two repositories. A total of 52 new AMS 14C dates were obtained on samples from OMNHP. Of these newly run AMS 14C dates, 14 were from the Middle Plateau, four were from Council Chamber 2, and 34 were from the Earthlodge (Mound D-1). Samples (wood charcoal) were selected for (1) dating using established criteria and conventions and (2) documenting relevant archaeological information from the field notes and drawings that can be used as informed priors in Bayesian modeling of the radiocarbon dates.

Sample selections from the Middle Plateau area prioritized short-lived species (e.g., maize) and carbonized wood from features and known contexts in and around the Macon Trading House. We dated samples of posts from the Trading House moat, the precontact ditches, and refuse pits associated with this area of the settlement (Figure 4). To date the Earthlodge, we selected one of the single-log roof-support beams (Pinus spp.) and several pieces of cane (Arundinaria gigantea) from the entryway (see Figure 3). For Council Chamber 2, we choose a large sample of carbonized wood (Pinus spp.) that likely represents architectural materials (e.g., wall posts or roof supports; see Figure 3). WPA-era archaeologists treated samples from these areas with paraffin—a petroleum-based wax—as a conservation agent. During the pretreatment process, it was necessary to remove it.

Figure 4. Outline of the archaeological features of the Middle Plateau and the location of the samples for AMS radiocarbon dating (Image courtesy of Greg Luna Golya and Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park). (Color online)

The charred post sample from the Earthlodge roof-support-beam sample was manually cleaned to remove the bulk of the paraffin coating. Our strategy for these samples was to date a series of rings from consecutive years of growth of the post (i.e., the same tree) and then use the known pattern of atmospheric radiocarbon to match it to the calibration curve—otherwise known as wiggle matching—which allows one to refine the date (e.g., resolving multiple intercepts on calibration plateaus) for the tree and sometimes estimate its felling date (see Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Ramsey, Christopher and Weninger2001). Subsamples were collected from individual tree rings; from an exposed cross section, we started from the outermost ring and sampled inward (Figure 5). Samples were collected from two contiguous sections, which we called the “outer series” and “inner series.” A total of 18 single-year rings were sampled from the outer series. The inner series consisted of approximately 21 tree rings, which were smaller and more difficult to sample than the outer series. A total of 14 samples were collected from the inner series: eight single-year rings and six samples from multiyear blocks (2–4 rings collected together). Sample masses ranged from 20 to 50 mg.

Figure 5. Ocmulgee Mound D-1 (Earthlodge) post after manual cleaning: (left) locations of outer and inner series; (center) after collection of Ring 3 from outer series; (right) after collection of Ring 11 from outer series (Photos courtesy of the Center for Applied Isotope Studies at the University of Georgia). (Color online)

The Council Chamber 2 sample (see Figure 2) was manually cleaned, and the three subsamples were collected from individual tree rings. Unlike the Earthlodge sample, which was a large and intact sample, the Council Chamber 2 samples were fragmented and housed in a packaged collection (e.g., wood fragments in a jar) that presumably was a single intact specimen at one point. We make this assumption because during the WPA era, single smaller fragments of carbonized wood were not regularly collected because radiocarbon dating as a method had not yet been invented. Consequently, large fragments or whole posts were most likely collected to be examined for tree-ring chronologies, a method that had been developed at that time (see Dean Reference Dean, Taylor and Aitken1997). Our strategy for these samples was to date the outermost ring for each fragment, assuming that they were from the same tree. The “youngest” date in this sequence should then be the terminus post quem (TPQ) for the Council Chamber 2 structure.

AMS Methods

All tree-ring subsamples were treated with hexane and acetone at 50ºC to remove trace remnants of paraffin and then dried at 105ºC. After that, the samples were treated following the acid/alkali/acid (AAA) protocol, which involves three steps: (1) an acid treatment (1N HCl at 80°C for one hour) to remove secondary carbonates and acid-soluble compounds, (2) an alkali (NaOH) treatment, and (3) a second acid treatment (HCl) to remove atmospheric CO2. Samples were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water between each step, then dried at 105ºC. Samples were graphitized on IonPlus Automated Graphitization Equipment (AGE-3) with an online elemental analyzer (EA).

δ13C by IRMS (Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry)

Approximately 1 mg of each sample was encapsulated in tin, and stable isotope ratios (δ13C) were measured using an elemental analysis-isotope ratio mass spectrometry (EA-IRMS). Values are expressed as δ13C with respect to Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB), with an error of less than 0.1‰.

14C by AMS

Graphite 14C/13C ratios were measured using the CAIS 0.5 MeV accelerator mass spectrometer. The sample ratios were compared to the ratio measured from the Oxalic Acid I standard (NBS SRM 4990). The quoted uncalibrated date is given in radiocarbon years before 1950 (years BP) using the 14C half-life of 5,568 years. The error is quoted as one standard deviation, and it reflects both statistical and experimental errors. The dates have been corrected for isotope fractionation using the IRMS-measured δ13C value.

Bayesian Modeling

We employed Bayesian statistical modeling of the dates using OxCal4.4 and the IntCal20 calibration curve to evaluate not only the sequence or contemporaneity of structures but also the occupational history of the settlement (Bronk Ramsey Reference Ramsey and Christopher2009). Bayesian modeling relies on prior archaeological information (e.g., stratigraphy, superpositioning) to overcome ambiguities in the radiocarbon calibration curve (Hamilton and Krus Reference Hamilton and Anthony2018). This method allows for the development of more precise chronologies that would otherwise be expressed only in generalities. For example, rather than saying that a given archaeological phenomenon dates to a 200-year period, Bayesian modeling allows for a generational understanding of time, sometimes on the order of 20-year increments (Bayliss Reference Bayliss2009; Birch et al. Reference Birch, Manning, Sanft and Conger2021; Darvill et al. Reference Darvill, Marshall, Pearson and Wainwright2012). A major advantage of the IntCal20 calibration curve is the increased density of single-year measurements on known-age tree rings, in some cases enabling decadal precision when wiggle-matching timbers (e.g., Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Marshall, Dee, Friedrich, Heaton and Wacker2020:Figure 12).

We constructed a number of different models for each area based on our knowledge of sample type, ordering, and overall context. We follow the conventions outlined by Manning and Birch (Reference Manning and Birch2022) regarding the capitalization of commands and functions in OxCal for clarity (e.g., Date, Phase). All modeled dates are also italicized according to standard practice (Hamilton and Krus Reference Hamilton and Anthony2018). We report the model agreement index; however, we note that this is not a true statistical measure but rather a way to assess how well the stipulated parameters agree with the dates (i.e., the performance of the model). An Amodel value of 60 or greater is considered good agreement (Bronk Ramsey Reference Ramsey and Christopher1995, Reference Ramsey and Christopher2009). Here, we only present the models that we believe best represent the archaeological context for each area. Although there were minor differences among the models, the final estimated age ranges for each model do not vary to a large degree (e.g., decades).

Earthlodge (Mound D-1)

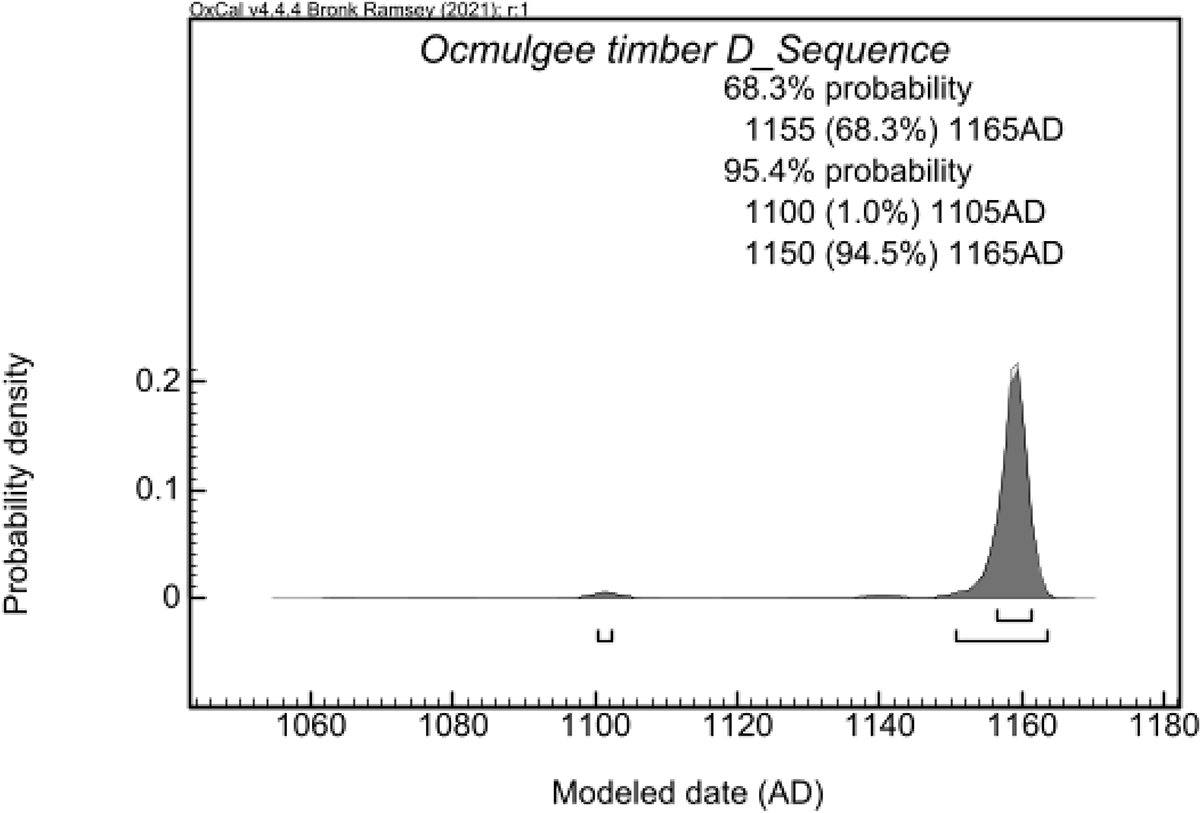

The model for the Earthlodge places all dates from the structure into one Phase, which includes unordered dates on cane from the entryway and a D_Sequence that estimates the felling date of the charred support posts. As used here, a Phase is a bounded (e.g., with a start and end) grouping of dates that date a defined archaeological event; however, the exact order of dates within the Phase is unknown (see Bronk Ramsey Reference Ramsey and Christopher2009; Hamilton and Krus Reference Hamilton and Anthony2018). For each of the single-year samples, these dates were incorporated into the wiggle-match model, with gaps of one year between each growth year. Unfortunately, in the early part of the sequence, we were unable to sample at the single-year interval and therefore ended up sampling blocks of two to four years. These were excluded from the D_Sequence, and we insert a 12-year gap between these innermost sampled individual rings and the single-year sequence of dates leading up to felling edge for this log. Additionally, one individual outlier (the innermost ring sampled) was manually removed from the model due to our low confidence in the Lab’s ability to sample this ring accurately.

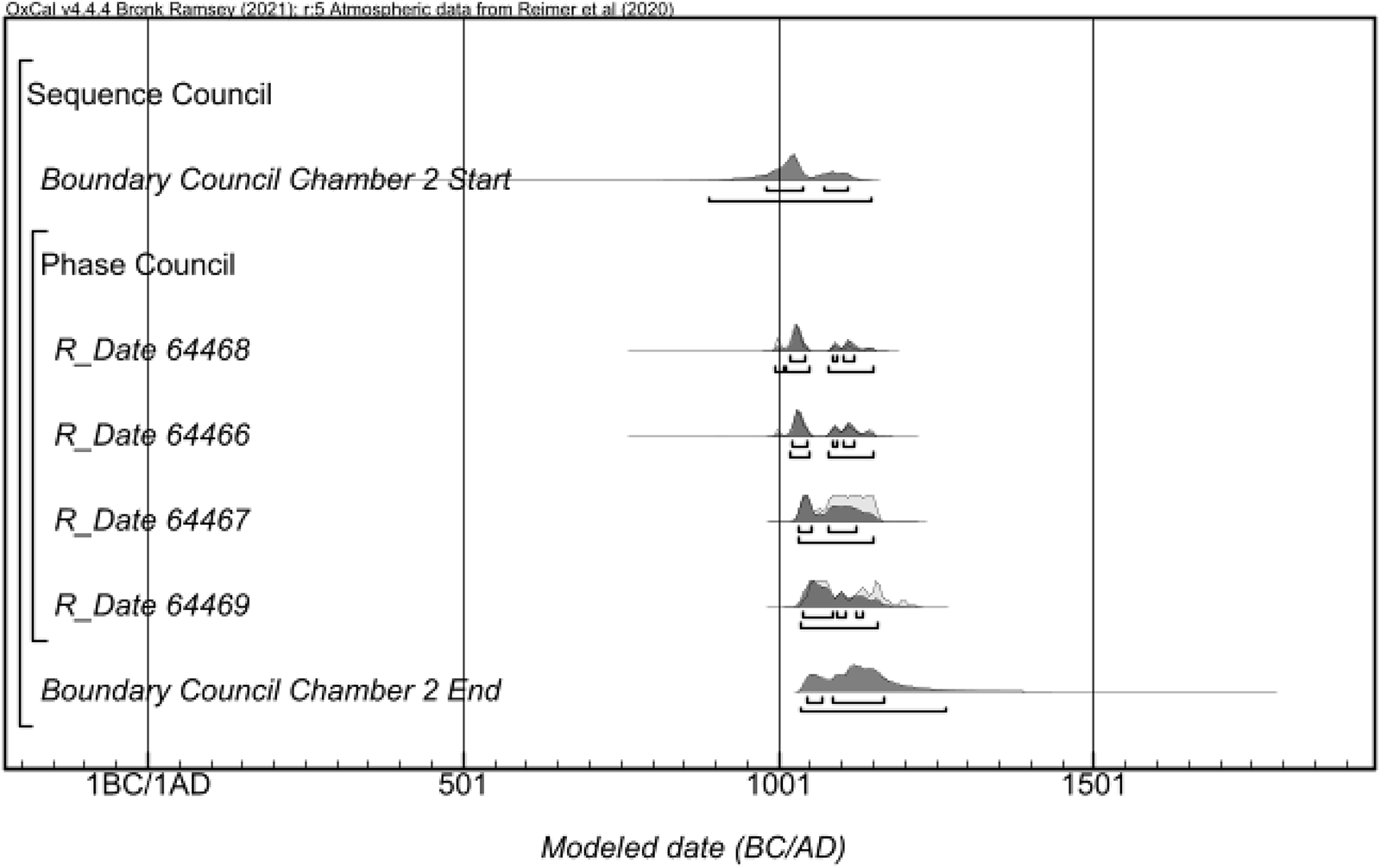

Council Chamber 2

The model for Council Chamber 2 places all the dates from the samples into one Phase. The dates in the Phase are unordered. However, we assume that each of the terminal rings of each sample is part of the same log and that the youngest date in this Phase represents the TPQ for the structure.

Middle Plateau

For the Middle Plateau model, the samples are placed into one Phase. The dates in the Phase are unordered given that they come from a variety of features distributed throughout this locale (see Figure 4). We use the kernel density estimate (KDE) command in OxCal to provide a summary of the probability distribution (see Manning et al. Reference Manning, Birch, Conger, Dee, Griggs, Hadden and Hogg2018). Since we know from documents that the Middle Plateau—and specifically the Macon Trading House—was abandoned in 1715, and that all of the samples dated come from features and contexts definitively associated with this event, we use the C_Date command to make this the TAQ for the occupation (for other examples of this operation for “historic period” sites, see Manning et al. Reference Manning, Huey, Lucas and John2021; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Jefferies and Moore2020).

Results

An overview of study samples, dates, and contexts are presented in Tables 1 and 2. We report all dates in this table regardless of their incorporation into the results of the models presented below. Tables of dates and detailed runfile code for each of the models and the estimated age ranges are provided (Supplementary Material 2–4).

Table 1. Radiocarbon and Stable Isotope Results of OCMU 64593 FS#10032.25.

Note: Rings are numbered in the order in which the samples were collected, with Ring 1 being the outermost ring and Ring 39 being the innermost.

Table 2. Radiocarbon Samples, Contexts, and Dates for the Middle Plateau Area and Council Chamber 2 Areas of 9BI1.

Earthlodge (Mound D-1)

As stated above, the prior dates run on the Earthlodge sample had broad calibrated calendar ages due to large uncertainties and multiple intercepts with the calibration curve. To overcome these challenges, we use a D_Sequence command with known age gaps between samples.

The model indicates good agreement between the dates and stipulated parameters. The Amodel (99) exceeds the 60-threshold (see Supplementary Material 2). Although our model does not totally eliminate the probability of a slightly earlier construction, it is much more likely that the Earthlodge was constructed at a later date. The D_Sequence for the Earthlodge roof-beam post estimates a felling date sometime after cal AD 1155–1165 (68%) and cal AD 1150–1165 (94%; Figure 6). There is a small second peak representing a range of cal AD 1100–1105 (1%). The two dates run on short-lived river cane suggest both an earlier use of the area—possibly from an earlier structure—and a date that seems to be contemporaneous with the use of the later excavated Earthlodge as estimated by the post D_Sequence model (Figure 7a–c).

Figure 6. Earthlodge (Mound D-1) Timber D-Sequence results.

Figure 7. (A) Probability distribution of the earlier cane sample from the Earthlodge entryway; (B) probability distribution of the later cane sample from the Earthlodge entryway; (C) probability distributions comparing the D_Sequence timber with the two cane dates.

Council Chamber 2

The Council Chamber 2 model indicates good agreement between the dates and stipulated parameters. The Amodel (87.6) exceeds the 60-threshold (see Supplementary Material 3). The model estimates (1) a start date for the Council Chamber 2 occupation as cal AD 980–1115 (68%) and cal AD 885–1150 (95%) and (2) an end date of cal AD 1045–1170 (68%) and cal AD 1030–1270 (95%). If our assumption that the youngest date sample represents the TPQ for the post from which all these samples derive is correct, then the Council Chamber 2 use must fall sometime after cal AD 1035–1135 (68%) and cal AD 1035–1160 (95%; Figure 8).

Figure 8. Probability distributions for the Council Chamber 2 context samples from Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park. The light gray and dark gray together represent calibrated distributions, and the dark gray distribution alone represents the posterior density estimates based on the model.

Middle Plateau

The Middle Plateau model indicates good agreement between the dates and stipulated parameters. The Amodel (94.4) exceeds the 60-threshold (see Supplementary Material 4). The model estimates a start date for the Middle Plateau occupation as cal AD 1140–1215 (68%) and cal AD 1055–1255 (95%). The end date for the occupation is based on the abandonment date of AD 1715 stated in the documents. The distribution of dates for this area clearly indicated more or less continuous occupation (Figure 9). We caution, however, that although we do have data suggesting continuous occupation, we do not have the ability to characterize it fully at this point in time. It could have been a more nucleated settlement or simply a few farmsteads. From a probabilistic standpoint, more dates are necessary to resolve these questions.

Figure 9. Probability distributions for the Middle Plateau context samples from Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park. The light gray and dark gray together represent calibrated distributions, and the dark gray distribution alone represents the posterior density estimates for the model that incorporates at a TAQ of 1715 based on historic documents and archaeological information.

Of particular interest to this point is sample UGA 61307 on one of the maize cobs from the area, which produced a modeled date of cal AD 1324–1415 (68%) and cal AD 1315–1425 (95%). Unfortunately, we currently do not have the archaeological data to resolve the double peak represented in this distribution (see sample UGA 61307 in Figure 10). Nevertheless, the entire distribution falls within the period of hypothesized abandonment and is therefore a significant date on a short-lived sample for this time frame. Furthermore, if we look at the distribution of dates and the kernel density estimate (KDE) plot, we see a gradual increase with a peak in the post–AD 1600s period (see Figure 9). The peak is likely a product of our sampling of features associated with the Macon Trading House and those that are directly adjacent to it (see Figure 4).

Figure 10. Earthlodges and collective memory: (A) the Council House Museum in Okmulgee, Oklahoma (photograph by Victor D. Thompson); (B) photo of the Earthlodge adorning the walls of the Council House Museum (photograph by Victor D. Thompson); (C) the Enfulletv-Mocvse in Archaeology Field School in front of the Mound Building in Okmulgee, Oklahoma (photograph by Gano Perez Jr.). (Color online)

Discussion

The collaborative dating project at OMNHP provides critical new insight into the cultural landscape of the park. This is especially important given the renewed push to make OMNHP Georgia’s first national park. It is critical that the comanagement of the TCP by Muscogee Nation, other Muskogean-speaking peoples and related federally recognized Tribal Nations such as the Seminole Nations, and the National Park Service relies on the most up-to-date information as public visitation and engagement with the park increases in the coming years. Although we recognize that there is always more to learn about any TCP, the information currently presented to the public—especially regarding the chronology and occupation of OMNHP—is particularly problematic. Our dating project demonstrates that both long-held beliefs about the timing of the construction of the public buildings and assumptions about the abandonment of OMNHP either lack support or are far more complicated than previously thought.

The Earthlodge and Public Buildings

Given that the Earthlodge is one of OMNHP’s main features and is an important cultural touchstone for the Muscogee Nation, understanding the timing of the construction and use of this structure(s) is necessary to be able to not only present the correct information to park visitors but also situate the OMNHP Earthlodge in broader Ancestral Muskogean and other federally recognized Tribal Nations’ histories. Park signage both in front of the Earthlodge and on the National Park Service website (https://www.nps.gov/places/ocmulgee-mounds-earth-lodge.htm) provides a construction date for the floor of AD 1015, which is the median date of the radiocarbon dates run in the 1960s (Wilson Reference Wilson1964; see Supplementary Material 5).

Our new dating suggests that the roof timbers of the Earthlodge were cut down sometime after circa AD 1160. One of the cane fragments from the entryway to the Earthlodge also suggests continued use for some time after construction. However, the other cane-fragment date seems to indicate an earlier occupation. This earlier date would be consistent with an earlier construction and would also fit in this time frame. As we mentioned above, our coauthor Williams observed another burned floor under the current exposed Earthlodge floor. We speculate that this fragment of cane may be associated with an earlier structure that had the same layout as the later Earthlodge.

The rebuilding of earth lodges and council houses in the American Southeast is observed elsewhere in the archaeological record, some of which have long histories (Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Marquardt, Walker, Thompson and Newsom2018). In fact, the council house that was constructed in Oklahoma at the time of the forced removal of the Muscogee and other related federally recognized Tribal Nations from Georgia was first made of wood and then subsequently burned and reconstructed with brick. This structure continues to be an active council house in addition to being a museum. The enduring connection between the Earthlodge in Macon and the council house in Oklahoma is apparent by the many photos of the Earthlodge that adorn its walls (Figure 10a).

Our dating program from the other council house at OMNHP (Council Chamber 2) was less successful at precisely resolving the history of construction due to the challenges of this portion of the radiocarbon curve. Nevertheless, the models for Council Chamber 2 point to it being constructed around AD 1100, making it roughly contemporaneous with the Earthlodge. Multiple, contemporaneous earth lodges would have supported clans having their own councils, debates, and places to take medicine. Such a view would be consistent with the plurality of clans/lineages associated with individual mound grouping at Moundville, as argued by Knight (Reference Knight, Vernon and Vincas1998). Consequently, this provides a different perspective—or rather, one that emphasizes more communal democratic institutions—regarding governance (see Milner Reference Milner1998; Muller Reference Muller1997). This falls in line with the work of researchers in the broader southeast and Midwest, who have argued for more bottom-up perspectives regarding Mississippian polities than those favoring an emphasis on the agency of singular individuals and political hierarchy (see Schroeder Reference Schroeder2004:328–330). Consequently, the dates on both this structure and the Earthlodge provide new insight into the histories of these public buildings and the community that constructed them.

The Earthlodge and Council Chamber 2 both appear to be structures that focused on communal and cooperative governance. Beginning in the 1930s, archaeologists knew there were a number of these types of structures not only at OMNHP but elsewhere in the immediate vicinity, such as Brown’s Mount (see Marshall and Williams Reference Marshall and Williams2005); however, it was unclear how these structures—and other architecture (e.g., mounds)—functioned as a cohesive whole. The possibility of temporal overlap in the construction and use of these council structures may lend some support to Hally and Williams’s (Reference Williams and Hally1994:84) “subcommunity” hypothesis. The subcommunity hypothesis holds that Ocmulgee consisted of many different smaller community units that centered around mounds and their plazas, as well as council structures (Bigman Reference Bigman2012:7). Our new dating program provides a higher degree of confidence regarding the contemporaneity of structures than simply relying on the ceramic assemblage for these areas. Our dating project lends some initial support for the subcommunity perspective for OMNHP. This is important because, according to Hally and Williams (Reference Williams and Hally1994:95), the spatial segregation of mound complexes—constructed between 250 and 300 m apart—suggests a planned community layout. The addition of mounds, plazas, and council houses to existing architecture in an effort to integrate growing communities has been observed in archaeological research at other ancestral Muscogee towns (Brannan and Birch Reference Brannan, Birch, Malouchos and Betzenhauser2021).

Founding Communities and Occupational Histories

Given that the community pattern at OMNHP seems to be one that was planned from its founding, we must then ask who the people who participated in this new settlement were and where they were from. And although we cannot fully address these two questions, our new understanding of the chronologies at OMNHP does provide some insight into these larger research themes. Early archaeologists recognized that the ceramics at OMNHP were unlike other assemblages in central Georgia, possibly suggesting that migration into the area was the genesis of its establishment (Williams Reference Williams and Hally1994:130–131). In fact, the Macon Plateau case has been the example of a migration event in the southeast since it was proposed early on in the history of work in the region. Williams (Reference Williams and Hally1994:137) lays out the most cogent argument for the in-migration of people likely from the area of northwestern Georgia or eastern Tennessee. Although the rather unique ceramic assemblage still remains one of the strongest lines of evidence for migration, there are several lines of evidence laid out by Williams (Reference Williams and Hally1994) that no longer hold. Among these is the observation that OMNHP is not reoccupied after its supposed AD 1100 abandonment (Williams Reference Williams and Hally1994:137).

We now, of course, know that the Earthlodge floor as excavated by federal archaeologists in the 1930s dates after AD 1100 and that the timeline for the founding of OMNHP may be more complicated than previously thought. We currently only have two dates that suggest an occupation prior to AD 1100, including one of the cane dates from the Earthlodge and another date from the Middle Plateau, which both predate the main occupation of OMNHP. This, of course, does not negate the fact that there were people who occupied this landscape prior to this time (given that there is evidence of earlier deeper time occupations); instead, it refers to the current mounded landscape that is the recognizable core area of the site one observes today. Therefore, if this later date for the community’s florescence is correct, it lends more support to migration explanations. Schroedl (Reference Schroedl and Hally1994:141) critiques the idea of migration mainly because traits found at OMNHP are not apparent in eastern Tennessee until around AD 1200. Our new dating of the Earthlodge clearly puts OMNHP more in line with the timing of such developments in eastern Tennessee and northwest Georgia. Furthermore, our dating from the Middle Plateau indicates that the occupation of OMNHP was not a short-lived phenomenon, with dates on maize indicating occupation of this area up to and through the 1700s, when the trading post was in operation (see Mason Reference Mason2005). Finally, our new chronological understanding of Ocmulgee is now in line with the spread of Mississippian culture as conceived of by researchers, such as Anderson (Reference Anderson and Jill1999:225–226, Reference Anderson and Gregory2017:302), who have taken a macroregional approach to understand this phenomenon.

Conclusions

The 52 new dates from both the Middle Plateau and public buildings (e.g., the Earthlodge) provide insights into the founding and occupational history of OMNHP. In sum, the dating of the Earthlodge suggests that this structure was in use later than expected, which places some of the developments at OMNHP in line with known Ancestral Muskogean histories (e.g., migration stories). Furthermore, our work showing a likely continued occupation in at least one section of the settlement speaks to some degree of cultural continuity in the area with later known “Creek” towns, a point not often explored by archaeologists (Birch et al. Reference Birch, Hunt, Lesage, Richard, Sioui and Thompson2022). This aspect of our work requires additional exploration, given that although some of the dates fall during the time frame that OMNHP is thought to be abandoned, more dates will be necessary to understand the nature of the occupation at this time (e.g., small town, farmsteads, etc.). As a final point, we acknowledge that cultural ties to place—past and present—are a part of lived experience and not always well represented by archaeological evidence or settler-colonial mindsets about the same. We need to keep this in mind as we move forward with these kinds of collaborations and the role that archaeology plays in such discussions.

Although our new dates complicate OMNHP’s history, it is undeniable that there is still much to be learned from the large collections from the site that the National Park Service houses. This work also underscores the importance of museum collections and that, as it currently stands, the knowledge produced from the study of those collections is not proportional to the scale of the excavations at OMNHP. Even though the way in which WPA archaeologists conducted the excavations at the settlement clearly presents challenges to modern research, the archives are nonetheless invaluable, and they can be creatively approached with questions that are of interest to both archaeologists and the Muscogee Nation.

Finally, our work regarding the chronology and settlement history of OMNHP can speak to a variety of anthropologically relevant questions, including some of the grand challenges identified by Kintigh et alia (Reference Kintigh, Altschul, Beaudry, Drennan, Kinzig, Kohler and Limp2014). However, for our research at OMNHP, we forefront the interests of the Muscogee Nation, centering the research on Tribal histories and understanding the broader connection of the Nation to this TCP. For the Muscogee Nation and other Muskogean-speaking peoples and other federally recognized Tribal Nations, OMNHP is one of the most important cultural heritage places in Georgia, and understanding and linking its history to their own understandings is critical. The fact that early council houses in Oklahoma (e.g., Tuckabatchee) had structural elements similar to the Earthlodge (Williams Reference Williams2016); that the historic Muscogee Nation council house museum in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, displays pictures of the famous Earthlodge building excavated at OMNHP in the 1930s; and that the Mound Building in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, is reminiscent of the Earthlodge (Figure 10b–c) demonstrates that this connection is alive and well. These structures and places are not from bygone eras of unknown people. Instead, they are directly connected to lineal descendants. As OMNHP moves into the future, these deeply entangled cultural roots of all Muskogean-speaking peoples and related federally recognized Tribal Nations should be highlighted and recognized as the past meets the present. Finally, as our new work demonstrates, the time for a more collaborative approach to research is at hand in the region, and it is becoming more widely practiced. This road has not always been easy, and many people have paved the way for the kind of collaborative work that we present here.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Muscogee (Creek) Nation for their support of this research. The National Park Service provided critical support and access to these collections. In addition, we benefited from conversations with several of our colleagues, including LeeAnne Wendt and Stephen Kowalewski. Marcie Demyan graciously provided our Spanish abstract. Finally, we especially thank the editors of both Advances in Archaeological Practice and American Antiquity, Sarah Herr and Debra Martin, respectively; and Charlie Cobb and two anonymous readers for their review of and comments on the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This research was funded, in part, by the University of Georgia, Faculty Research Grants Program; UGA Center for Applied Isotope Studies; and the National Park Service.

Data Availability Statement

All dates, code, and data necessary to understand and replicate this study are available in the manuscript and supplemental material included with this publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Supplementary Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2025.10106.

Supplementary Material 1. Generalized Event and Occupation History as It Has Been Historically Understood (table).

Supplementary Material 2. Earthlodge (Mound D-1) (table).

Supplementary Material 3. Council Chamber 2 (table).

Supplementary Material 4. Middle Plateau (table).

Supplementary Material 5. Top: Photo of the Earthlodge from the visitor’s center at OMNHP, which is often the first stop for park goers as they make their way across the park; bottom: sign in front of the Earthlodge noting that it is the oldest lodge and was dated to AD 1015 (image courtesy of Greg Luna Golya and Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park) (figure).