Non-technical Summary

Coal balls, calcium carbonate nodules that preserve ancient plant material, provide a unique window into the ecosystems of Pennsylvanian tropical peat swamps that were living approximately 300 million years ago. These fossils capture the interactions between plants and terrestrial arthropods, helping scientists understand the structure of prehistoric food webs. In this study, we examined two borings—small tunnels created by organisms—that are preserved in a coal ball from the Mt. Rorah Coal Member in Illinois. These borings contain coprolites, or fossilized fecal material, offering insight into the dietary habits of ancient arthropods. Our findings suggest that an early roach-like insect (Blattoptera), millipede, or another terrestrial arthropod created the borings while feeding on the roots of Psaronius, a prehistoric tree fern. Within these tunnels, we discovered two distinct types of coprolites: larger ones that likely came from the original borer and much smaller ones, which were probably produced by oribatid mites that fed on the larger fecal material. This process, known as coprophagy, indicates a complex ecological interaction where one organism’s waste becomes another’s food source. The absence of damage to surrounding plant tissues suggests that the roots were already dead or rapidly fossilized after the borings were made. This discovery provides new evidence of arthropod-driven decomposition in ancient peat swamps, shedding light on how these ecosystems processed plant material. By studying these fossils, we gain a better understanding of the roles of early insects and mites in the nutrient cycle of Carboniferous forests, revealing a sophisticated prehistoric ecosystem where even the smallest organisms played vital roles in maintaining ecological balance.

Introduction

The analysis of trophic dynamics, feeding behaviors, and nutrient cycles sheds light on how organisms coexist and influence their ecosystems in both extant and ancient systems. Evidence from trace fossils, including feeding traces such as borings through plant tissue and herbivore fecal material (or coprolites), allows for reconstructions of ancient food webs, illustrating the broad roles of herbivores and detritivores in nutrient cycling (Scott and Taylor, Reference Scott and Taylor1983; Labandeira, Reference Labandeira2007). Food webs of ancient ecosystems can give insight into the structure of past communities and the evolutionary relationships among primary producers, consumers, and decomposers. These interpretations reveal the life histories of ancient species and provide valuable insight into how ecosystems function and adapt over time and respond to environmental change (Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997; Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Schachat and Monarrez2023).

Coal balls, masses of permineralized peat from the Carboniferous Period, provide a rich record of the interactions between terrestrial arthropods and plants in the form of coprolites and feeding traces such as borings (Scott and Taylor, Reference Scott and Taylor1983; Labandeira, Reference Labandeira, Herrera and Pellmyr2002, Reference Labandeira2013). These traces offer direct evidence of ancient plant–arthropod associations and can be used to understand the feeding behaviors of the terrestrial arthropods that produced them (Scott and Taylor, Reference Scott and Taylor1983).

Live borings occur when arthropods feed on living plant tissue, often triggering a wound response in the form of hyperplastic or hypertrophic cell growth, callus formation, or other structural modifications as the plant attempts to heal (Labandeira, Reference Labandeira1998). In contrast, borings in dead or decaying tissue do not induce a wound response and are characterized by the absence of reaction tissue, because the plant is no longer metabolically active (Labandeira, Reference Labandeira1998; Labandeira and Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips2002). The presence of wound-response tissue in fossilized plants indicates that the feeding occurred while the plant was still alive, whereas borings in decayed material suggest postmortem feeding, likely by detritivores contributing to decomposition.

Borings by arthropods in live tissue, which have been documented as far back as the Late Mississippian, also are found in Pennsylvanian coal balls (Labandeira, Reference Labandeira1998; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Rothwell and Mapes2003; Falcon-Lang et al., Reference Falcon-Lang, Labandeira and Kirk2015). Borings through live tissue with a wound response of flattened or otherwise modified parenchymatous cells also have been described in the phloem of lyginopterids from permineralized fossils from the Late Mississippian of Arkansas (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Rothwell and Mapes2003; Falcon-Lang et al., Reference Falcon-Lang, Labandeira and Kirk2015). Falcon-Lang et al. (Reference Falcon-Lang, Labandeira and Kirk2015) described additional live-tissue borings in Middle Pennsylvanian cordaitalean leafy branches from calcic-permineralizations from the Pennant Sandstone Formation in Southern England. Laaß et al. (Reference Laaß, Kretschmer, Leipner and Hauschke2020) described borings in a living calamitalean stem from the Osnabrück Formation in Germany (Middle Pennsylvanian).

Postmortem borings have been described in both Pennsylvanian compression and coal ball assemblages. Arthropod borings in intact calamitalean stems have been documented in compression assemblages of the Wettin subformation (Late Pennsylvanian, Gzhelian) and Osnabrück Formation (Middle Pennsylvanian, Moscovian) in Germany (Laaß and Hauschke, Reference Laaß and Hauschke2019; Laaß et al., Reference Laaß, Kretschmer, Leipner and Hauschke2020). The borings in a calamitalean stem from the Wettin subformation are infilled with two different classes of coprolites—smaller coprolites (63–74 μm in greatest diameter) and larger coprolites (123–158 μm in greatest diameter) (Laaß et al., Reference Laaß, Kretschmer, Leipner and Hauschke2020). Based on the size of the coprolites and borings, the authors suggested that the producers were small xylophagous millipedes of different developmental stages or oribatid mites.

Multiple studies have reported terrestrial arthropod borings specifically in coal balls (Rothwell and Scott, Reference Rothwell and Scott1983; Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Beall and Hueber1988; DiMichele and Phillips, Reference DiMichele and Phillips1996; Labandeira, Reference Labandeira1998; Labandeira and Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips2002; Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Guillemette, Jones and Ahr2012). Cichan and Taylor (Reference Cichan and Taylor1982) described borings filled with uniformly shaped coprolites attributed to oribatid mites in Premnoxylon wood from the Cranks Creek locality in Kentucky (Middle Pennsylvanian). Rothwell and Scott (Reference Rothwell and Scott1983) described a coprolite-filled boring through ground tissue in a Psaronius stem from the Conemaugh Group of the Appalachian Basin (Late Pennsylvanian). Labandeira and Phillips (Reference Labandeira and Phillips2002) described borings in the pith of trunks of Psaronius (Pteridiscaphichnos psaronii Labandeira and Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips2002) containing coprolites (1–3 mm diameter) from the Middle and Late Pennsylvanian of the Illinois Basin. Labandeira (Reference Labandeira1998) documented a Medullosa stem filled with coprolites from the Late Pennsylvanian Calhoun Coal. The specimen is notable because the reaction tissue indicated the plant was alive during feeding.

Fecal pellets originating from terrestrial arthropods are commonly found in coal balls scattered among permineralized plant organs. They can be found associated with a particular plant organ involving targeted herbivory or scattered throughout the peat matrix as evidence of detritivory. Large, isolated coprolites, which originate in the canopy and are produced by herbivorous or detritivorous insects, are sometimes incorporated into coal ball-forming peat. Fecal material provides evidence of the diverse feeding strategies that occur in the fossil record, including detritivory (feeding on dead plant matter), herbivory (feeding on live plants), palynivory (feeding on spores and pollen), and coprophagy (feeding on fecal material) (Mamay and Yochelson Reference Mamay and Yochelson1953, Reference Mamay and Yochelson1962; Baxendale Reference Baxendale1979; Scott and Taylor, Reference Scott and Taylor1983; Labandeira Reference Labandeira1998, Reference Labandeira2000). Such feeding strategies can originate from several sources representing the consumption of live or dead plant material in the forest canopy, understory, or forest floor within litter (Scott and Taylor, Reference Scott and Taylor1983).

Unlike compression fossils, the unique preservation of the internal cellular structure of the carbonate permineralized plants in coal balls allows for the taxonomic identification of the tissue types and affiliations contained within coprolites. Although arthropod coprolites are abundant in coal balls, the body parts of their producers are absent. This has been attributed to the acidity of the original peat from which coal balls are formed (Labandeira and Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips2002; Labandeira, Reference Labandeira2006). However, arthropod cuticle is known to survive hydrochloric acid digestion (Bartram et al., Reference Bartram, Jeram and Selden1987), which suggests that acidity alone may not explain its absence. Given the scarcity of body fossils, coprolites and feeding traces from coal balls offer a unique insight into the feeding behaviors of detritivorous and herbivorous arthropods, their digestive processes, and their life history.

In this study, we describe two borings in a Pennsylvanian coal ball from the Mt. Rorah Coal Member and provide evidence that the borings were made by a roachoid or other arthropod through underground Psaronius roots. Both borings have been filled with arthropod fecal material. The borings also contain smaller fecal pellets from oribatid mites, suggesting coprophagy. These findings provide insight into the structure of Pennsylvanian peat swamp food webs, suggesting terrestrial arthropods facilitated decomposition within the upper layers of peat. These interpretations rely on morphological and ecological comparisons with extant taxa, however, and alternative hypotheses or contributions from other organisms cannot be definitively excluded. This work highlights the complex ecological relationships between arthropods and decaying plant material, while also revealing the life histories and functional roles of the organisms that produced these trace fossils.

Geological setting

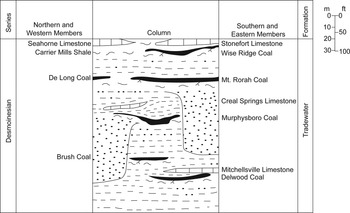

Coal balls are primarily calcium carbonate nodules that precipitate in peat swamps and are widely distributed in tropical Carboniferous Euramerican coal seams (Phillips, Reference Phillips1981; Scott and Rex, Reference Scott and Rex1985; Lakeram et al., Reference Lakeram, Elrick and Punyasena2023). The early Desmoinesian Mt. Rorah Coal Member is located in the upper Tradewater Formation and sits stratigraphically below the Wise Ridge Coal and above the Murphysboro Coal (Fig. 1). The Mt. Rorah Coal Member occurs throughout southern Illinois (outcrop and subsurface), ranging from a thin stratum over most of its extent to 1.6 meters thick in Jackson County, Illinois, where it was mined locally (Kosanke et al., Reference Kosanke, Simon, Wanless and Willman1960). It was previously known as the Bald Hill coal (Cady, Reference Cady1926). The Mt. Rorah Coal Member is typically brightly banded, with a thin 1–30 cm layer of claystone running through the middle of the unit (Willman et al., Reference Willman, Atherton, Buschbach, Collinson, Frye, Hopkins, Lineback and Simon1975). The Mt. Rorah coal ball flora is dominated by lycopsids, pteridosperms, cordaitaleans, and marattialean tree ferns (Elrick et al., Reference Elrick, DiMichele, Falcon-Lang and Nelson2021). Botanically, the unit is most similar to late Desmoinesian peat plant assemblages (Elrick et al., Reference Elrick, DiMichele, Falcon-Lang and Nelson2021). It displays an unusual abundance of terrestrial arthropod fecal material and other feeding traces with exceptional preservation.

Figure 1. A stratigraphic column depicting the stratigraphic position of Mt. Rorah Coal Member within the Illinois Basin.

Material and methods

The Phillips Coal Ball Collection at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is the largest and most significant collection of coal balls globally. In the collection, we found two peels of UIUC Coal Ball 40458 from the Mt. Rorah Coal Member. The original coal balls for these specific peels are absent from the collection.

We digitized the peels using an AxioCam ICC5 camera mounted on a Zeiss Axio Zoom V16 microscope at 7× magnification and 300 dpi resolution (Lakeram et al., Reference Lakeram, Elrick and Punyasena2023). Both peels were systematically described and censused using a 1-cm² grid, with each grid section classified according to its most prominent plant organ or invertebrate trace (Pryor, Reference Pryor1988). This allowed us to calculate the total surface area occupied by each plant taxon or invertebrate trace. To estimate the compaction ratio of the coal ball from which these peels originated, we compared the average cell sizes of similar tissues in coal balls from the same coal bed and calculated the volumetric organic matter content (Winston, Reference Winston1986). We then categorized coprolites from the borings into two groups based on maximum diameter, contents, and degree of comminution, guided by observations from Baxendale (Reference Baxendale1979) and Scott and Taylor (Reference Scott and Taylor1983).

We next digitized thin sections of fecal pellets from extant terrestrial arthropod species from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (USNM) collection using a Zeiss Axio Scan Z1 slide scanner at 7× magnification and 300 dpi resolution. Collected from modern insects, the pellets were first embedded in synthetic resin blocks, then sectioned with a microtome and mounted onto glass slides. Each fecal pellet was then described based on its maximum length, width, and contents.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

High resolution images used for figures are deposited on Morphosource and available for download (https://www.morphosource.org/projects/000697572?locale=en). Peels of UIUC Coal Ball 40458 are deposited at the Phillips Coal Ball Collection at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC). Slides of modern fecal pellets are deposited at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH).

Results

Coprolite types

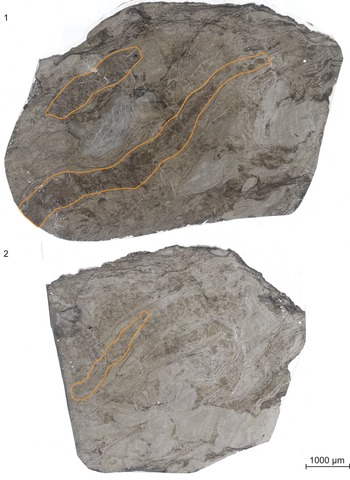

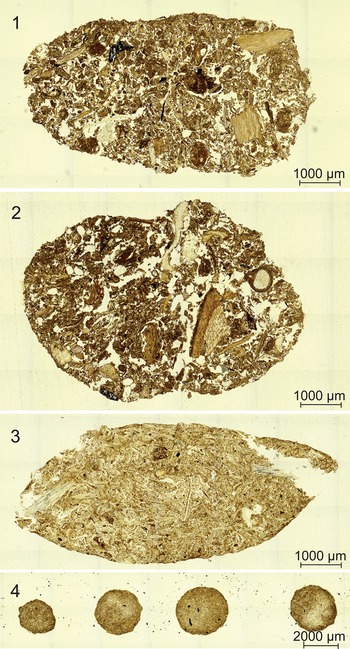

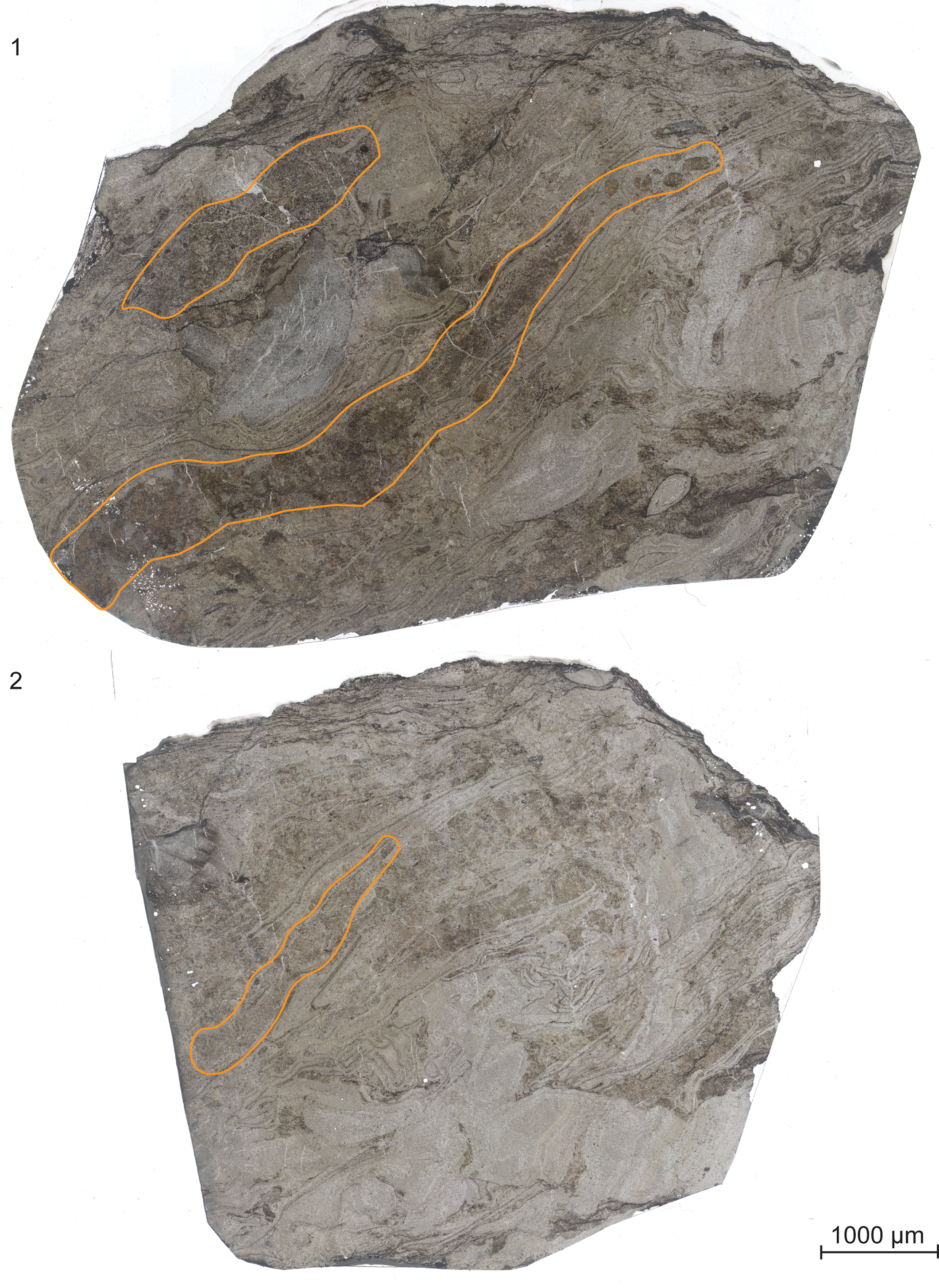

Two distinct coprolite types occur in both borings. Type 1 coprolites are oblong and range in size from 0.5–1.5 mm in length and 0.9–1.2 mm in width (Fig. 3.1, 3.2). Type 2 coprolites are spherical and range in diameter from 40–60 μm (Fig. 3.3). Broadly, type 1 coprolites have a defined shape, with bluntly rounded ends. However, some type 1 coprolites are broken up or disturbed, with type 2 coprolites deposited within (Fig. 3.4). Both coprolite types occur only within the borings and are homogeneous in composition, containing material from Psaronius roots (Fig. 3). No other coprolites were found in the surrounding vegetative material. None of the plant tissues in the peel, including the Psaronius roots surrounding the borings, display wound-response tissue or other signs of live-plant feeding. Type 1 coprolites are deposited in a string-like formation and type 2 coprolites are distributed randomly throughout both borings. Type 2 coprolites are highly comminuted in comparison to type 1 coprolites.

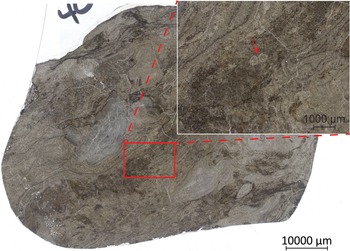

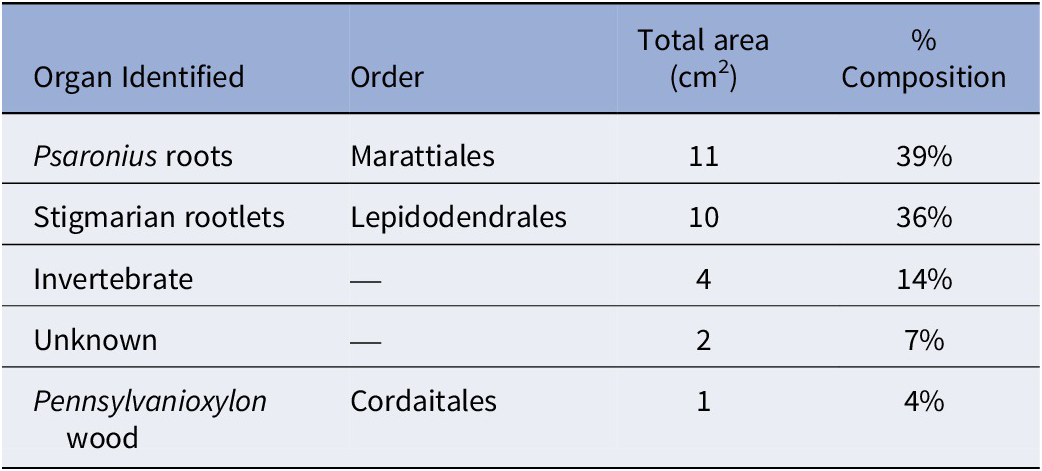

Coal ball UIUC 40458 BTOP

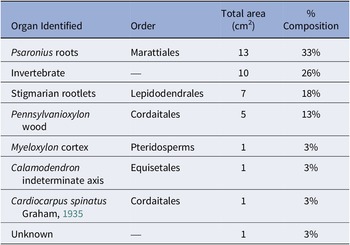

The total surface area of the coal ball peel from UIUC 40458 B-TOP is 39 cm2 and primarily composed of Psaronius roots (33%), Stigmaria rootlets (18%), Pennsylvanioxylon wood (13%), with other organs from pteridosperms, Cordaitales, and Equisetales (Table 1). Invertebrate traces, which consist of borings and fecal material, account for 26% of the total composition (Table 1). Plant organs demonstrate a compaction ratio of 1:7, although the borings display no signs of compaction or deformation.

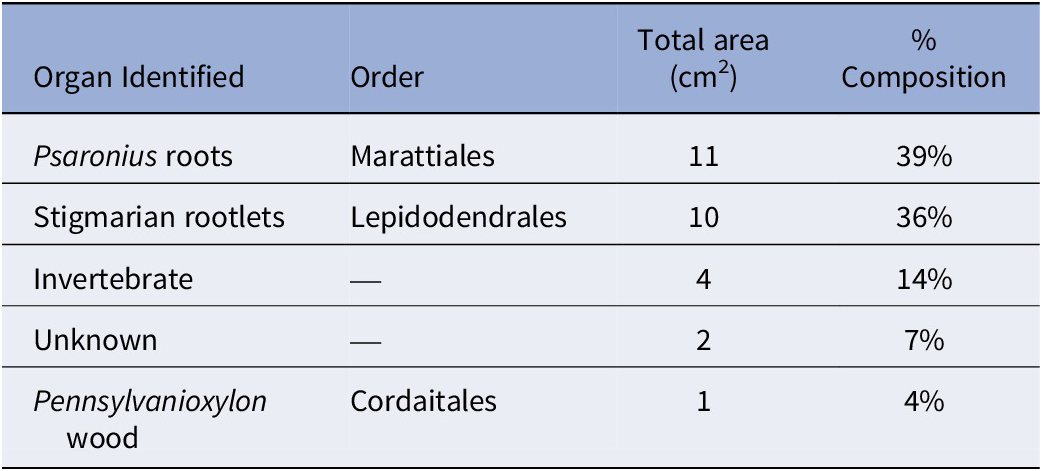

Table 1. The percent taxonomic composition of peel UIUC 40458 BTOP

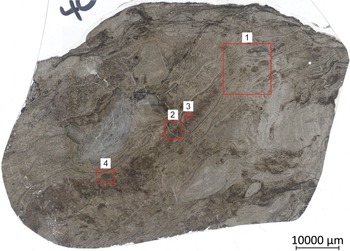

Description of borings. The two borings are 3 cm and 6 cm in greatest length and are 300–750 μm wide. They follow along the transverse margin of Psaronius roots growing into the peat surface (Fig. 2.1). The roots surround a piece of fusanized woody tissue from Pennsylvanioxylon, a cordaitalean. Both borings penetrate through the Psaronius root mat and avoid the fusanized woody tissue. They are filled with a mixture of type 1 and type 2 coprolites. No secondary Psaronius roots are present within either boring.

Figure 2. Scanned peels of (1) UIUC 40458 BTOP and (2) 40458 CEND. Borings filled with both type 1 and 2 coprolites are outlined in orange. UIUC 40458 BTOP contains two coprolite-filled borings through Psaronius roots.

On the left side of the peel in the orientation in Figure 2, the 6-cm boring contains disaggregated or amorphous coprolitic material from both types 1 and 2 (Fig. 2.1). The middle of the boring contains fragments of Psaronius roots and defined type 1 coprolites. Type 2 coprolites are intact and disaggregated through this portion. There are two round megaspores in the larger boring with little to no surface texture, a widened flange, and no indication of an aperture. The spores measure 630 and 780 μm in greatest diameter, are not incorporated in any coprolite, and do not show signs of feeding (Appendix Fig. 3). The right side of the boring mostly contains intact type 1 coprolites with little to no type 2 coprolites. The 3-cm boring contains mostly a high density of type 2 coprolites, with type 1 coprolites distributed throughout (Fig. 2.1). Calcite veins run along the lateral axis of the boring.

Figure 3. Coprolites in borings through a Psaronius root mantle (UIUC 40458 BTOP). (1) Type 1 coprolites from a roachoid or other terrestrial arthropod containing tissue from Psaronius roots indicated by red arrows (16×). (2) An arrow pointing to a type 1 coprolite in a boring surrounded by type 2 coprolites from oribatid mites (16×). (3) Type 2 coprolites ranging from 40–60 μm in greatest diameters indicated by the arrows (40×). The differences in the size indicated by the red arrows of oribatid mite coprolites indicate feeding of different instar stages. (4) A disturbed type 1 coprolite (orange arrow) containing type 2 coprolites (red arrows; 16×). See Appendix Figure 2 for a map of focus points on peel UIUC 40458 BTOP.

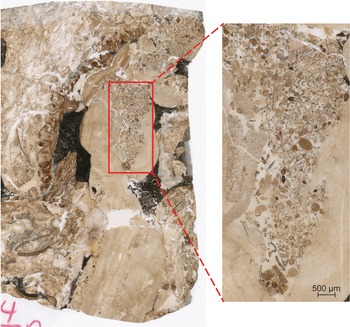

Coal ball UIUC 40458 C-END

The total surface area of the coal ball peel from UIUC 40458 C-END was 28 cm2 and is primarily composed of Psaronius root mantle (39%) and Stigmaria rootlets (36%), including a small piece of fusanized wood from a cordaitalean (Table 2). C-END (Fig. 2.2) partially captures the external regions of the 6-cm boring identified in UIUC 40458 B-BOT (Fig. 2.1). Evidence for invertebrate interaction, consisting of borings and fecal material, accounted for 14% of the total surface area (Table 2). Both coprolite types are present in the boring from C-END, however, type 2 coprolites are more prevalent than type 1. Calcite veins are present within the boring and follow along the latitudinal axis (Fig. 2.2).

Table 2. The percent taxonomic composition of peel UIUC 40458 CEND

Discussion

Context of the borings

The morphology of Psaronius (marattialean tree fern) consists of both adventitious above-ground roots and underground roots. Both identified borings occur along the transverse margin of Psaronius underground roots that penetrated the peat to anchor the plant and capture resources (Gillette, Reference Gillette1937; Stidd and Phillips, Reference Stidd and Phillips1968; Rothwell, Reference Rothwell199l; Rößler, Reference Rößler2000; Labandeira and Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips2002). Psaronius adventitious roots consist of an outer mantle, which is composed of hundreds of sclerenchymatous rootlets. This root mantle is located above ground and encapsulates a central stem acting as a trunk-like structure (Stidd and Phillips, Reference Stidd and Phillips1968; Rößler, Reference Rößler2000; Labandeira and Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips2002).

Both borings are filled with type 1 and 2 coprolites. The coprolites only contain digested fragments of Psaronius roots, which indicates that the producers of both coprolite types fed on the Psaronius root ground tissue surrounding the borings. The dimensions of both borings suggest that they were produced by the producer of type 1 coprolites. Three possibilities can explain how these borings were made. Specifically, both borings were created by an insect or other terrestrial arthropod in: (1) decaying Psaronius roots within compressed peat, (2) living tissue that was quickly permineralized before wound reaction tissue could develop, or (3) a void space between Psaronius roots.

Arthropod borings in live tissues are typically characterized by galleries of open space that are filled with fecal pellets. Notably, wound response is indicated by the proliferation (hyperplasia) or enlargement (hypertrophy) of cells along the feeding margin or gallery, indicating that the plant was alive during feeding (Labandeira and Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips1996; Labandeira, Reference Labandeira1998; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Rothwell and Mapes2003; Falcon-Lang et al., Reference Falcon-Lang, Labandeira and Kirk2015). Wound-reaction tissue was not displayed by Psaronius roots in the microenvironment surrounding the borings (Fig. 2). No evidence of degradation or senescence such as flattened, shrunken, or lignified cells is displayed on Psaronius roots indicating that this organ was alive or had not begun the decomposition process at the time of permineralization. Fungal material was not observed within the boring or in either coprolite types. The absence of wound-reaction tissue along the margin of the borings, degradation of tissues, or fungal activity within signifies that fossilization occurred quickly after feeding (Labandeira and Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips2002).

The low compaction ratio of 1:7 for the vegetative material and the presence of activity by terrestrial arthropods suggest that this coal ball represents layers of peat close to or at the surface of the peat swamp in the acrotelm or uppermost layer of a peat deposit containing live plants. Compaction of the plant material in the coal balls represents the continual deposition of organic material in peat forests, which is influenced by the amount of biomass available (Winston, Reference Winston1986; Long et al., Reference Long, Waller and Stupples2006; van Asselen et al., Reference van Asselen, Stouthamer and van Asch2009). The borings do not show any signs of compaction or deformation relative to the surrounding compacted vegetative material. It is expected that little to no compaction will be observed on live tissue, specifically rooting structures penetrating the peat. These lines of evidence suggest that Psaronius roots grew into the acrotelm consisting of compacted vegetative material. The tissue was then bored by arthropods creating both borings in this coal ball. The lack of compaction in the borings, along with the absence of deformation, broken or degraded roots, and reaction tissue in both the borings and surrounding vegetation, suggests that they formed shortly before permineralization and were preserved quickly thereafter. Psaronius roots are commonly found growing among and through organs of other plants deposited on and within the peat surface (Raymond and Phillips, Reference Raymond, Phillips and Teas1983; DiMichele and Phillips, Reference DiMichele and Phillips1994).

Void spaces, areas that do not contain any material, commonly occur in coal balls and can result from decomposition, outgassing, or deformation. These spaces can sometimes act as a collection area for material that has sifted through the peat (Appendix Fig. 4). Due to the unique arrangement of the fecal pellets and structure of this feature, it is unlikely that the borings were void spaces. Void spaces typically collect a random mixture of unsorted material; however, the coprolites in the borings studied here are sorted (Appendix Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Modern fecal pellets from Macropanesthia rhinoceros Saussure, Reference Saussure1895 (Blattodea) containing wood fragments (1–3) and Cryptocercus clevelandi Byers in Nalepa et al., Reference Nalepa, Byers, Bandi and Sironi1997, containing conifer wood fragments (4). Smithsonian identification numbers are (1) USNM 483978-12; (2) USNM 483978-11; (3) USNM 483978-1; (4) USNM 483967-3. The yellow background is due to the embedding medium.

Two megaspores occur within the 6-cm boring of UIUC 40458 BTOP (Appendix Fig. 3). Notably, no trilete marks are visible on either megaspore, which may result from the orientation of the spores within the acetate peel. The spores show no signs of feeding or digestion, as evinced by their uncompressed flanges. The megaspores may have been incorporated into the boring through the movement of the producing organisms or after the boring was created.

Producer of the borings and coprolites

Several coprolite types within coal balls have been reported and can be categorized based on size, shape, content, and spatial distribution in relation to plant organs (Baxendale, Reference Baxendale1979; Scott and Taylor, Reference Scott and Taylor1983). Baxendale (Reference Baxendale1979) categorized coprolites in coal balls from Illinois, Iowa, and Kansas into four types based on composition and morphology. Scott and Taylor (Reference Scott and Taylor1983) further expanded the criteria for Baxendale’s (Reference Baxendale1979) categories by focusing more closely on coprolite content and compaction, identifying three classes. Class 1 coprolites occur in the coal ball matrix not associated with a plant organ and are typically loosely packed (>1 mm in greatest dimension). They generally are loosely aggregated and contain a mix of or a single tissue type. Most Class 1 coprolites are filled with monospecific spores or pre-pollen. Compact coprolites in this category typically contain unidentifiable debris. Class 2 coprolites occur in the coal ball matrix or decomposing stems (150 μm to 1 mm in greatest dimension). They are typically round in cross-section, although irregularly shaped coprolites that contain unidentifiable plant fragments have been identified. Class 3 coprolites are the most common coprolite type in coal balls and almost always occur in clusters (<150 μm in greatest dimension). These coprolites are typically produced by oribatid mites and are found in the coal ball matrix or in association with vascular tissue. They are sometimes observed in borings of vascular tissue (Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997). Following the class categorization from Scott and Taylor (Reference Scott and Taylor1983), type 1 and 2 coprolites from the Mt. Rorah borings can be classified as class 2 and 3 coprolites. Although similar in content, the significant size difference in type 1 and 2 coprolites indicates that at least two different feeders were present in these borings.

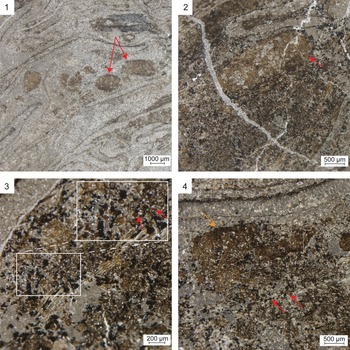

Type 1 coprolites bear a close resemblance to those of Blattodea in size, shape, and degree of comminution (Fig. 4). Based on the context and dimensions of both the borings and type 1 coprolites, it is most likely that the producer was Blattodea, millipedes, or another terrestrial arthropod. Modern Blattodea and their roachoid ancestors are typically considered facultative consumers and generalists (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Roth and Nalepa2007). The upper layers of peat and the abundant amount of detritus provide the optimal habitat for these cryptic insects. The borings and type 1 coprolites can be attributed to (1) general herbivory, where the producer feeds broadly on living tissue not seeking out any specific tissue type; (2) specialized herbivory, where the producer seeks out a specific tissue type that is living; (3) general detritivory, where the producer feeds on dead and decaying organic matter in the peat not seeking out any specific tissue type; and (4) specialized detritivory, where the producer feeds on dead and decaying organic matter from specific tissues (Hopkin and Read, Reference Hopkin and Read1992; Yang, Reference Yang2006; Labandeira, Reference Labandeira2007; Swart et al., Reference Swart, Samways and Roets2022).

Modern cockroaches are known to primarily be generalist omnivores, which are polyphagous feeders often inhabiting cryptic environments (Brues, Reference Brues1946; Kühnelt, Reference Kühnelt1976; Bell and Adiyodi, Reference Bell and Adiyodi1982; Schal et al., Reference Schal, Gautier and Bell1984; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Roth and Nalepa2007). Some species are saprophagous, feeding on decaying vegetation, while others are phytophagous, feeding on living plants (Kevan, Reference Kevan1962; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Roth and Nalepa2007). The preservation of type 1 coprolites containing fragments of Psaronius roots within the borings indicates that the producer deposited fecal pellets in situ as it fed, boring its way through Psaronius ground roots. The most common insect fossils known from the Carboniferous are roachoids (Wootton, Reference Wootton and Rainey1976; Scott and Taylor, Reference Scott and Taylor1983), which are distantly related to modern cockroaches and termites. Scott and Taylor (Reference Scott and Taylor1983) identified possible roachoid coprolites in coal balls from the Lewis Creek locality, Kentucky, that are characteristically cylindrical, ranging in length from 0.2–2 mm. These descriptions are similar to type 1 coprolites from the borings we present (Fig. 2).

Early millipedes also could have produced coprolites similar in size and morphology to those observed in the Mt. Rorah borings. Millipedes were present in Pennsylvanian peat forests and are well-documented detritivores in extant systems, feeding on decaying plant matter and producing elongate, cylindrical fecal pellets that measure 500 μm to 6 mm long and 200 μm to 4 mm wide (Scott, Reference Scott1977; Paulusse and Jeanson, Reference Paulusse and Jeanson1977; Hopkin and Read, Reference Hopkin and Read1992). The deposition pattern and size range of coprolites in these borings indicate that the producer displayed some level of sociality and that adults coexisted with instar stages. Modern millipedes are known to be primarily solitary detritivores with some groups displaying subsocial behaviors (Camatini, Reference Camatini1979; Hopkin and Read, Reference Hopkin and Read1992; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Hennen, Macias, Brewer, Kasson and Marek2020).

Rothwell and Scott (Reference Rothwell and Scott1983) described a stem of Psaronius magnificus (Herzer, Reference Herzer1901) in a coal ball from the Monongahela Group of Ohio (Upper Pennsylvanian), where the ground tissue was bored out and replaced with coprolites. The coprolites are oval in shape, measuring 400 μm in diameter, and are preserved in situ. Labandeira and Phillips (Reference Labandeira and Phillips2002) found similar associations in Psaronius from the Herrin and Calhoun coals, Illinois (Middle and Upper Pennsylvanian, respectively), and described a new ichnospecies, Pteridiscaphichnos psaronii, characterized by a distinctive network of borings in the ground parenchyma tissue in the stem. The borings range in diameter from 6–13 cm and are filled with ellipsoidal coprolites measuring 1–3 mm in length, along with fragments of macerated but unconsumed plant tissue. The borings are typically located among vascular strands within the outer stem tissues and exhibit no evidence of reaction tissue, indicating that they were formed post-mortem. The geometry of the tunnels, along with the morphology of the coprolites, suggest that a roach-like insect was the producer of Pteridiscaphichnos. The variation in coprolite size and abundance suggests that individuals at different developmental stages contributed to the feeding activity.

The borings we describe in the Mt. Rorah Coal Member share some similarities with Pteridiscaphichnos. The producer deposited fecal pellets in situ while tunneling through Psaronius tissue. The coprolites from Mt. Rorah are similar in size, shape, and mastication patterns to those in Pteridiscaphichnos, although the former contains significantly fewer type 1 coprolites. This discrepancy may be due to oribatid mites incorporating these coprolites into the surrounding matrix. Additionally, the tissue in Pteridiscaphichnos exhibits minimal signs of decay, with little evidence of cell shrinkage or lignification. The coprolites in Pteridiscaphichnos psaronii contain ground parenchyma tissue from Psaronius, whereas the coprolites from the Mt. Rorah contain Psaronius underground roots. Additionally, Pteridiscaphichnos psaronii is significantly larger in its dimensions than the borings from the Mt. Rorah.

In coal balls, the smallest fecal pellet morphotypes are typically attributed to oribatid mites (40–100 μm in maximum diameter) and are found dispersed in clusters in live or decaying tissues (Scott and Taylor, Reference Scott and Taylor1983; Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997). Type 2 coprolites resemble those produced by oribatid mites, based on their size and shape (Scott and Taylor, Reference Scott and Taylor1983; Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997). The deposition of type 2 coprolites in these borings can be explained by two possibilities: (1) mites feeding directly on the surrounding living Psaronius roots during or after these borings were made, or (2) secondarily feeding on Psaronius tissue from type 1 coprolites. The latter is more likely because the root tissue surrounding these borings does not indicate signs of herbivory. Additionally, the high concentration of type 2 coprolites indicates that a colony of mites was responsible for fecal production, not a single individual. Oribatid mites are known to create large feeding galleries. However, the width of their feeding galleries typically does not exceed their body size (Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997). The width of these borings and the presence of type 1 coprolites suggest that mites did not produce the borings.

Some type 1 coprolites contain type 2 coprolites within them. This observation indicates that oribatid mites exhibited coprophagy, feeding on the Psaronius tissue in type 1 coprolites (Fig. 3C and D). Both extant and Pennsylvanian lineages of oribatid mites are known to display coprophagy (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Bocock and Heal1966; Wallwork, Reference Wallwork1976; Scott and Taylor, Reference Scott and Taylor1983; Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997). Previous coal ball studies have identified that oribatid mites targeted indurated plant tissues such as sclerenchyma, xylem, collenchyma, and the tests of Pachytesta seeds (Labandeira and Phillips, 1996; Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997), but also exhibited coprophagy, feeding on the digested material in coprolites from other terrestrial arthropods (Labandeira and Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips1996; Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997; Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Schachat and Monarrez2023). The homogenous content and spatial distribution of type 2 coprolites suggest that mites, in this context, directly fed on the digested Psaronius tissue in type 1 coprolites.

The role of oribatid mites in peat swamps

Several insect groups with mandibulate mouthparts are considered to be borers; however, a majority of reported Paleozoic borings are attributed to oribatid mites (Cichan and Taylor Reference Cichan and Taylor1982; Stidd and Phillips Reference Stidd and Phillips1982; Scott and Taylor Reference Scott and Taylor1983; Rex and Galtier, Reference Rex and Galtier1986; Labandeira and Beall, Reference Labandeira and Beall1990; Chaloner et al., Reference Chaloner, Scott, Stephenson, Jarzembowski, Alexander, Collinson, Chaloner, Harper and Lawton1991; Goth and Wilde, Reference Goth and Wilde1992; Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997; Rößler, Reference Rößler2000; Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Cutlip, Sweet, Allmon and Bottjer2001; Tomescu et al., Reference Tomescu, Rothwell and Mapes2001; Kellogg and Taylor, Reference Kellogg and Taylor2004; Raymond and McCarty, Reference Raymond and McCarty2009; Feng et al., Reference Feng, Wang and Liu2010, Reference Feng, Schneider, Labandeira, Kretzschmar and Röβler2015, Reference Feng, Wang, Rößler, Ślipiński and Labandeira2017; D’Rozario et al., Reference D’Rozario, Labandeira, Guo, Yao and Li2011; Césari et al., Reference Césari, Busquets, Méndez-Bedia, Colombo, Limarino, Cardó and Gallastegui2012; Slater et al., Reference Slater, McLoughlin and Hilton2012; Falcon-Lang et al., Reference Falcon-Lang, Labandeira and Kirk2015; Wan et al., Reference Wan, Yang, Liu and Wang2016; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Gou, Yang and Feng2019; Méndez-Bedia et al., Reference Méndez-Bedia, Gallastegui, Busquets, Césari and Limarino2020). Oribatid mites are small chelicerate arthropods with a box-like exoskeleton, superficially resembling beetles, and are 0.2–1.0 mm long (Luxton, Reference Luxton1972; Wallwork, Reference Wallwork1976). Mite borings and their coprolites can be found within all major plant groups from Pennsylvanian coal-ball deposits, including calamitaleans, cordaitaleans, lycopsids, ferns, and seed ferns, consuming primarily harder (sclerenchymatous) and occasionally softer (parenchymatous) tissue types (Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997). Such coprolites are typically found in close association with Psaronius tissues (Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997). One of the few tissue types avoided by oribatid mites is the periderm of lycopsids (Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997).

Evidence of oribatid mite feeding habits in coal balls reflect changes in plant dominance over time. Early to Middle Pennsylvanian peat swamps were dominated by arborescent lycopsids, with a shift at the Desmoinesian–Missourian boundary to tree ferns. This shift decreased the availability of vegetation from lycopsids to tree ferns (Psaronius), leading to increased consumption of softer tissues such as foliage and reproductive organs by oribatid mites (Phillips and Peppers, Reference Phillips and Peppers1984; Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997). No evidence of feeding on lycopsid periderm has been reported (Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997; Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Schachat and Monarrez2023).

The Mt. Rorah Coal Member was deposited during the Middle Pennsylvanian and represents a biome dominated by arborescent lycopsids (Elrick et al., Reference Elrick, DiMichele, Falcon-Lang and Nelson2021). Both coprolite producers in these borings fed solely on Psaronius material despite the availability of other plants. The coprophagy displayed by mites indicates that they targeted the digested Psaronius material in type 1 coprolites (Fig. 3C and D). As seen in the fossil record and modern ecosystems, coprophagous mites tunnel through larger coprolites of other terrestrial arthropods, such as insects and millipedes (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Bocock and Heal1966; Wallwork, Reference Wallwork1976; Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997; Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Schachat and Monarrez2023). Coprophagy aids in releasing and incorporating nutrients from terrestrial arthropod fecal pellets back into the soil (Zimmer and Topp, Reference Zimmer and Topp2002).

In extant ecosystems, many oribatid mites inhabit both living and dead plant organs, with most of this activity occurring in the upper aerobic layers of soil, where plant matter is most accessible (Mitchell and Parkinson, Reference Mitchell and Parkinson1976; Bellido, Reference Bellido1990; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Renker, Scheu and Maraun2004). They play a vital role in breaking down dead organic matter into smaller pieces of debris, thereby facilitating decomposition (Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Hayek, Fagundes and Silva2004; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Renker, Scheu and Maraun2004; Maraun et al., Reference Maraun, Erdmann, Schulz, Norton, Scheu and Domes2009). Both immature and adult stages display minimal dietary shifts in feeding on the same plant tissues, frequently creating feeding galleries in the material that they pack with their fecal pellets (Gourbière et al., Reference Gourbière, Lions and Pepin1985; Lions and Gourbière, Reference Lions and Gourbière1988, Reference Lions and Gourbiere1989; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Renker, Scheu and Maraun2004). The significant accumulation of fecal material in these borings and the known social behaviors of extant mites suggest that a colony of mites was feeding on type 1 coprolites. Oribatid mites form communities in decomposing plant litter and wood, acting as primary or secondary consumers of dead or partially decayed plant material (Woolley, Reference Woolley1960; Luxton, Reference Luxton1972; Kühnelt, Reference Kühnelt1976). In coal balls, mite coprolites are common and seldom occur distant from other coprolites of this type, typically occurring as clusters (Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997).

Decomposition in peat swamps

The coprolites in these borings capture a tritrophic food web interaction, illustrating the ecological roles of terrestrial arthropods in Pennsylvanian peat swamps. The producer of type 1 coprolites, likely a roachoid, millipede, or other terrestrial arthropod, fed on Psaronius roots while excavating borings, depositing fecal pellets composed of digested root tissue. The presence of type 2 coprolites, attributed to oribatid mites, indicates a secondary feeding interaction through coprophagy, where mites consumed partially digested Psaronius material from type 1 coprolites. This sequence of interactions suggests a structured food web, in which larger detritivores initiated decomposition by breaking down plant material, while smaller arthropods further processed organic matter, accelerating nutrient cycling within the peat swamp.

In modern forest ecosystems, nutrients primarily originate from decomposition, which results from interactions among bacteria, fungi, and invertebrate detritivores (Seastedt and Crossley, Reference Seastedt and Crossley1984; Lavelle et al., Reference Lavelle, Blanchart, Martin, Martin and Spain1993, Reference Lavelle, Lattaud, Trigo, Barois, Collins, Robertson and Klug1995). The abundance of peat during the Pennsylvanian indicates both weak climatic zonation and slow rates of decomposition (Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Cutlip, Sweet, Allmon and Bottjer2001, Reference Raymond, Lambert and Costanza2019). Pennsylvanian permineralized peats (coal balls) often contain delicately preserved tissues and organs, including megagametophytic tissues, phloem vascular tissue, and pollen tubes of seeds, which are uncommon or absent in modern peats (Rothwell, Reference Rothwell1971; Brack-Hanes, Reference Brack-Hanes1978; Taylor and Taylor, Reference Taylor and Taylor1993). The presence of these delicate tissue types indicates that ancient peats experienced slower rates of decomposition compared to modern terrestrial ecosystems (Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Cutlip, Sweet, Allmon and Bottjer2001). The continual deposition of excess detritus in tropical peat swamps during the Pennsylvanian, along with their ever-wet conditions, produced an optimal environment for terrestrial arthropods to flourish (Labandeira and Beall, Reference Labandeira and Beall1990; Labandeira, Reference Labandeira, Briggs and Crowther2001; Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Schachat and Monarrez2023).

Detritivores enhance the rate of organic decomposition by fragmenting large particles through digestion, thereby increasing the surface area available for fungal and microbial attack (Swift et al., Reference Swift, Heal, Anderson and Anderson1979; Nalepa et al., Reference Nalepa, Bignell and Bandi2001). Fungi and bacteria have been identified as important decomposers since the Devonian, and their relationship with terrestrial detritivorous arthropods may have originated during the Carboniferous (Smart and Hughes, Reference Smart, Hughes and van Emden1973; Kevan et al., Reference Kevan, Chaloner and Savile1975; Nalepa et al., Reference Nalepa, Bignell and Bandi2001). Blattodea are known to transfer microbes between individuals from a colony and inoculate their young for hindgut fermentation by coprophagy (Lavelle et al., Reference Lavelle, Lattaud, Trigo, Barois, Collins, Robertson and Klug1995; Nalepa et al., Reference Nalepa, Bignell and Bandi2001). It is possible that oribatid mites target fecal material from early roaches and other insects to gain access to hindgut microbes in addition to feeding on material that has already partially been digested, allowing access to more nutrients. Coprophagous insects typically exploit microbial consortia from the fecal material of other organisms (Nalepa et al., Reference Nalepa, Bignell and Bandi2001; Zimmer and Topp, Reference Zimmer and Topp2002).

Decomposition of vegetative material represents a major pathway for the transfer of nutrients between plants and the soil (Swift et al., Reference Swift, Heal, Anderson and Anderson1979; Vitousek and Sanford, Reference Vitousek and Sanford1986). Terrestrial arthropods act as facilitators for the transfer of these nutrients by increasing the surface area of plant tissue digested by breaking down larger particles into smaller particles and incorporating fungi within digested vegetative material to further accelerate decay. Their activity contributes to the formation of humus, enriching the soil with organic material, while also redistributing this matter both vertically and horizontally within the soil column. This decomposition process represents a fundamental pathway for nutrient transfer between plants and soil, highlighting the essential role arthropods play in nutrient cycling (Swift et al., Reference Swift, Heal, Anderson and Anderson1979; Vitousek and Sanford, Reference Vitousek and Sanford1986). In contemporary ecosystems, their influence extends to modulating carbon and nutrient flows, affecting the quality and availability of resources in the detrital food web (Yang and Gratton, Reference Yang and Gratton2014).

At the onset of the Pennsylvanian, arborescent lycopsids dominated many lowland ecosystems, which later transitioned to tree ferns in the Late Pennsylvanian (Pfefferkorn and Thomson, Reference Pfefferkorn and Thomson1982; Phillips and Peppers, Reference Phillips and Peppers1984; DiMichele and Phillips, Reference DiMichele and Phillips1996). There is substantial evidence for both herbivory and detritivory on Psaronius tissues by terrestrial arthropods in Pennsylvanian peat swamps, indicating a preference for this plant host (Rothwell and Scott, Reference Rothwell and Scott1983; Lesnikowska, Reference Lesnikowska1990; Labandeira and Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips1996, Reference Labandeira and Phillips2002; Labandeira et al., Reference Labandeira, Phillips and Norton1997). This preference is likely due to the accessibility of softer tissue and lack of periderm in Psaronius when compared to the arborescent lycopsids that were dominant during this time (Labandeira and Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips1996; Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Schachat and Monarrez2023). However, as these arthropods fed on Psaronius and other vegetation, they contributed significantly to the cycling of nutrients within these ancient ecosystems. The coprolites in these borings capture a tritrophic food web interaction where roachoids or other terrestrial arthropods fed on Psaronius roots and oribatid mites fed on roachoid fecal material. This interaction highlights the complex ecological relationships between flora and fauna in Pennsylvanian peat swamps, giving insight into the life history of terrestrial arthropods (DiMichele and Phillips, Reference DiMichele and Phillips1994; Labandeira, Reference Labandeira1998).

Conclusion

The continual deposition of vegetative material in tropical peat swamps during the Pennsylvanian produced an optimal environment for terrestrial arthropods. Detritivores enhanced the rate of organic decomposition by fragmenting larger particles into smaller particles through digestion, which increased the surface area available for fungal microbial attack. The discovery of two coprolite-filled borings in a coal ball from the Mt. Rorah Coal Member provides new insight into the life history and ecological interactions of Pennsylvanian terrestrial arthropods. Both borings occur along the transverse margin of Psaronius roots and are 3 cm and 6 cm in length. Two coprolite types occur in both borings, type 1 (0.5–1.5 mm in maximum diameter), which can be attributed to a roachoid or other terrestrial arthropods, and type 2 (50–60 μm in maximum diameter), which can be attributed to oribatid mites. Both coprolite types contain material from Psaronius roots and are only found within the borings. Psaronius roots along the margins of these borings do not display reaction tissue or show signs of senescence such as flattened, shrunken, or lignified cells, indicating that this boring was made in tissue that was possibly alive (although no reaction tissue is present) or had not begun the decomposition process at the time of permineralization. Due to the preservation of these borings with a lack of deformation, permineralization would have had to occur quickly after the borings were made. The dimensions of the borings suggest that they were made by the producer of type 1 coprolites. The spatial distribution and contents of type 2 coprolites demonstrate secondary feeding through coprophagy by oribatid mites. Together, the coprolites in these borings record evidence of a tritrophic food web, which gives insight into how terrestrial arthropods facilitated decomposition in Pennsylvanian coal swamp forests.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the University of Illinois Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology Core Facilities for access to microscopy equipment for digitization. We thank B. DiMichele (USNM) for insightful discussions about the Mt. Rorah coal. This work was supported by the University of Illinois Phillips Fund for Paleobotany and a Paleontological Society Norman Newell Early Career Grant to MPD. We thank the two anonymous reviewers and Associate Editor T. Wappler for their valuable comments and constructive feedback.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Data availability statement

High resolution images used for figures are deposited on Morphosource and available for download: https://www.morphosource.org/projects/000697572?locale=en.

Appendix

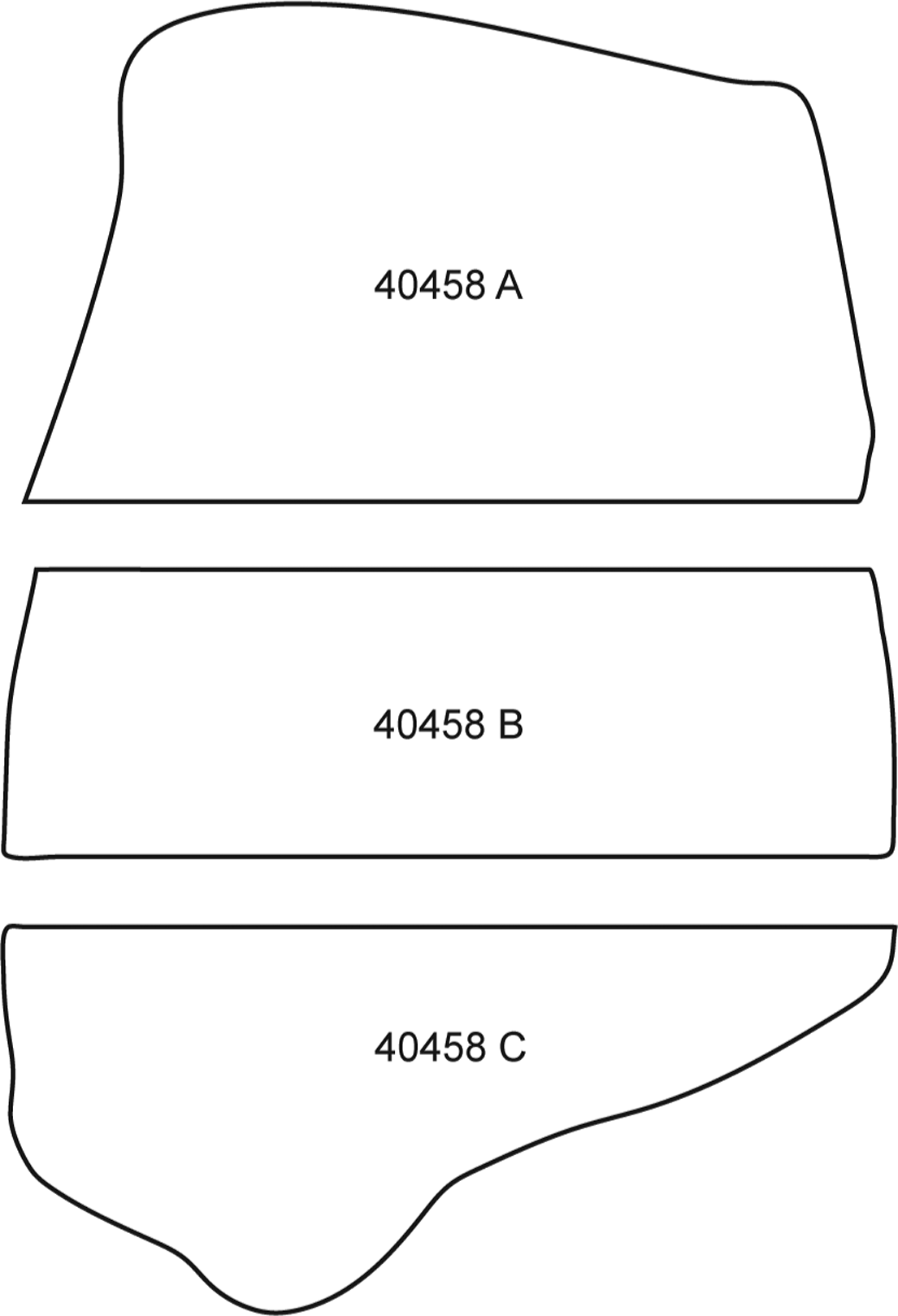

Appendix Figure 1. A schematic depicting how UIUC 40458 was sectioned with a rock saw into slabs.

Appendix Figure 2. Megaspores of lycopsids (indicated by the red arrow) measured in greatest diameter (from left to right, 630 μm and 780 μm). The megaspores are located in the 6-cm boring in UIUC 40458 BTOP surrounded by type 1 and 2 coprolites.

Appendix Figure 3. A scanned peel of UIUC 36674 CTOP from the Baker coal of Providence, Kentucky, depicting a void space filled with a random assortment of coprolites highlighted in red.

Appendix Figure 4. Peel UIUC 40458 BTOP highlighted to designate areas of interest in Figure 3.