Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is a complex psychiatric disorder characterised by the recurrent presentation of two or more distinct dissociative identity states. Reference Nijenhuis1 These are referred to as trauma-avoidant identity state and trauma-related identity state. Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2–Reference Reinders, Willemsen, den Boer, Vos, Veltman and Loewenstein4 The trauma-avoidant identity state of individuals with DID mentally avoids trauma-related knowledge and often reports subjective amnesia. Reference Nijenhuis1,Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2,Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Paans, Korf, Willemsen and Den Boer5,Reference Reinders, Dimitrova, Schlumpf, Vissia, Dean and Jäncke6 In a trauma-related identity state, individuals with DID are more likely to recall autobiographical trauma-related experiences. Reference Nijenhuis1,Reference Reinders, Willemsen, Vos, den Boer and Nijenhuis3,Reference Dorahy, Dorahy, Gold and O’Neil7–Reference Vissia, Giesen, Chalavi, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Brand9 Most research in DID has focused on overt stimulus presentation, while investigation of both overt and covert processing has mainly focused on emotional face-processing Reference Schlumpf, Nijenhuis, Chalavi, Weder, Zimmermann and Luechinger10,Reference Lebois, Palermo, Scheuer, Lebois, Winternitz and Germine11 or mirror confrontation tasks. Reference Schäflein, Mertens, Lejko, Beutler, Sattel and Sack12,Reference Lebois, Wolff, Hill, Bigony, Winternitz and Ressler13 The majority of these studies used standardised measures rather than subject-specific trauma-related stimuli. The present study aims to expand the literature through overt and covert presentation of individualised words.

Studying overt and covert processing using words is particularly advantageous because it allows for a highly individualised approach. Words can be carefully selected and individualised to each participant, ensuring that the stimuli are personally relevant and engaging. Additionally, words as stimuli provide a precise and measurable way to assess cognitive and emotional processing, which is particularly helpful in studying complex phenomena like dissociation where personalised and context-specific triggers can reveal nuanced insights into overt and covert processing mechanisms. For these reasons, in the present study individualised words were used. During the overt task condition the participants decided whether the word was relevant to themselves (as in Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2 ), while during the covert condition they decided whether or not the word contained a capital letter. This covert presentation method was previously proven effective in the research of Daselaar and colleagues Reference Daselaar, Fleck and Cabeza14 in healthy controls. The inclusion of a capital letter in a trauma-related word created a conflict of task, because the emotional content of the word was interfering with the decision process whether or not the word contained a capital letter, leading to a slower response to the actual capital letter task. Reference Daselaar, Fleck and Cabeza14

Aims and hypotheses

The present study aimed to investigate differences in behavioural performance and brain activation following overt and covert processing of self-relevant words, as compared with non-self-relevant words, in individuals with a diagnosis of DID and in a controlled manner. Therefore, we included three individualised word types, namely self-relevant trauma-related, non-self-relevant trauma-related (NSt) and non-self-relevant neutral (NSn) words. These were rated for self-relevance (yes/no) during the overt task condition and for the presence of a capital letter during the covert task condition (yes/no), while neural and behavioural data were collected. Behavioural performance and brain activation of participants with DID were compared with two control group:; DID-simulating actors and a carefully paired control group consisting of individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and healthy participants.

With regard to the behavioural data, we hypothesised that participants with DID would demonstrate slower reaction times to covertly presented self-relevant and trauma-related stimuli when in the trauma-related identity state, as compared with the control groups. Regarding the neural data, we hypothesised that individuals with DID would exhibit increased brain activation in the frontal and parietal regions when in the trauma-avoidant identity state, and in the areas of amygdala and insula when in the trauma-related identity state. Lastly, we hypothesised that participants with DID would show increased brain activation during covert processing, as compared with overt processing, especially in frontal regions.

Method

Participants

The present study was part of the larger Dutch Neuroimaging Dissociative Identity Disorder project, originally conducted in The Netherlands (see, for example, Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2,Reference Vissia, Giesen, Chalavi, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Brand9,Reference Chalavi, Vissia, Giesen, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Barker15–Reference Vissia, Lawrence, Chalavi, Giesen, Draijer and Nijenhuis19 ), where participants underwent task-based functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) during self-relevance rating of words from individualised word lists. Ethical approval was acquired by the Amsterdam Medical Centre (reference no. MEC09/155) and the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Centre Groningen (reference no. METC2008.211).

Behavioural and neural data of 56 participants were included in the current study: 14 women with a diagnosis of DID (DID-G), 14 healthy DID-simulating actors (DID-S) and a paired between-subject control (CTRL) group consisting of a total of 28 participants – 14 healthy non-psychiatric controls and 14 individuals with a PTSD diagnosis. The individuals with PTSD were included as controls for the trauma-related identity state of the DID-G participants, Reference Vissia, Giesen, Chalavi, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Brand9 whereas healthy, non-simulating, study-blind participants were included as a control group for the trauma-avoidant identity state of the DID-G group. The PTSD participants had a history of interpersonal traumatising events during childhood and/or adulthood, and they scored significantly lower than diagnosed DID individuals in dissociation scales, Reference Vissia, Giesen, Chalavi, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Brand9,Reference Chalavi, Vissia, Giesen, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Cole16,Reference Strouza, Lawrence, Vissia, Kakouris, Akan and Nijenhuis17,Reference Vissia, Lawrence, Chalavi, Giesen, Draijer and Nijenhuis19 thus not meeting the criteria for the dissociative subtype of PTSD. The healthy controls were, by default, non-psychiatric individuals due to our inclusion criteria that required, among others, low scores on the Dissociative Experiences Scale (cut-off <25), the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ-20, cut-off <28; SDQ-5, cut-off <7), the Traumatic Experience Checklist (impact <2) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait scale, as well as no history of psychiatric disorders or psychiatric medication. Reference Vissia, Giesen, Chalavi, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Brand9,Reference Chalavi, Vissia, Giesen, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Barker15,Reference Chalavi, Vissia, Giesen, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Cole16,Reference Reinders, Marquand, Schlumpf, Chalavi, Vissia and Nijenhuis20,Reference Reinders, Chalavi, Schlumpf, Vissia, Nijenhuis and Jäncke21 In line with the design and terminology used in our previous publications, in this study we refer to these non-psychiatric individuals as healthy controls. All participants were carefully matched in terms of gender, age and education level, were of Western European ancestry, native speakers of Dutch and aged between 18 and 65 years. Before their participation, individuals were informed about, and provided written consent to, the procedures, their withdrawal rights and the anonymity and confidentiality of their data. Further information regarding the specific characteristics of each participant group and reported identity states, simulation instructions and inclusion and exclusion criteria, Reference Vissia, Giesen, Chalavi, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Brand9,Reference Chalavi, Vissia, Giesen, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Cole16,Reference Strouza, Vissia, Schlumpf, del Marmol, Nijenhuis and Draijer18,Reference Vissia, Lawrence, Chalavi, Giesen, Draijer and Nijenhuis19 as well as comorbid disorders, Reference Reinders, Marquand, Schlumpf, Chalavi, Vissia and Nijenhuis20,Reference Reinders, Chalavi, Schlumpf, Vissia, Nijenhuis and Jäncke21 has previously been detailed.

Materials and procedure

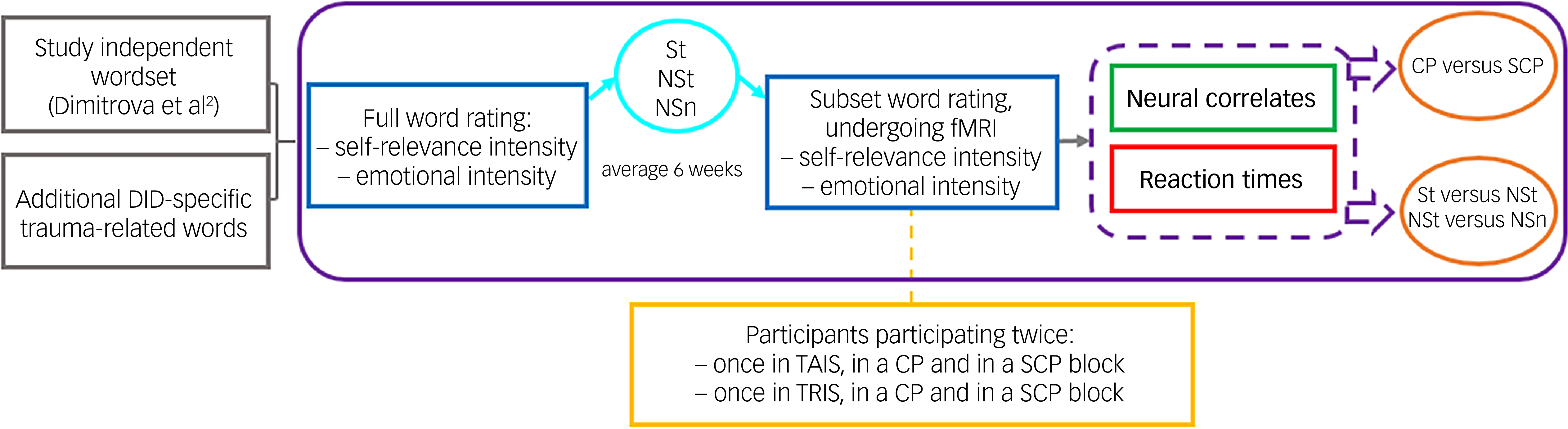

Word lists

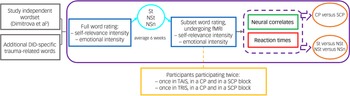

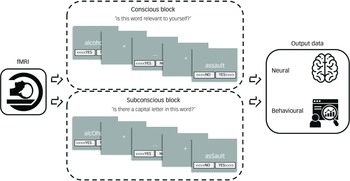

Individualised, subject-specific words were used during the behavioural data and fMRI sessions of the present study. Details on acquiring and determining these subject specific words are provided in Appendix A of the supplementary materials available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10914, reprinted from Strouza and colleagues Reference Strouza, Lawrence, Vissia, Kakouris, Akan and Nijenhuis17 (also used by Dimitrova and colleagues Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2 ). The word selection procedure is visualised in Fig. 1 (adapted with permission from Dimitrova and colleagues. Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2

Fig. 1 Study procedure. DID, dissociative identity disorder; St, self-relevant trauma-related; NSt, non-self-relevant trauma-related; NSn, non-self-relevant neutral; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; CP, conscious/overt processing; SCP, subconscious/covert processing; TAIS, trauma-avoidant identity state; TRIS, trauma-related identity state.

Brain imaging task description

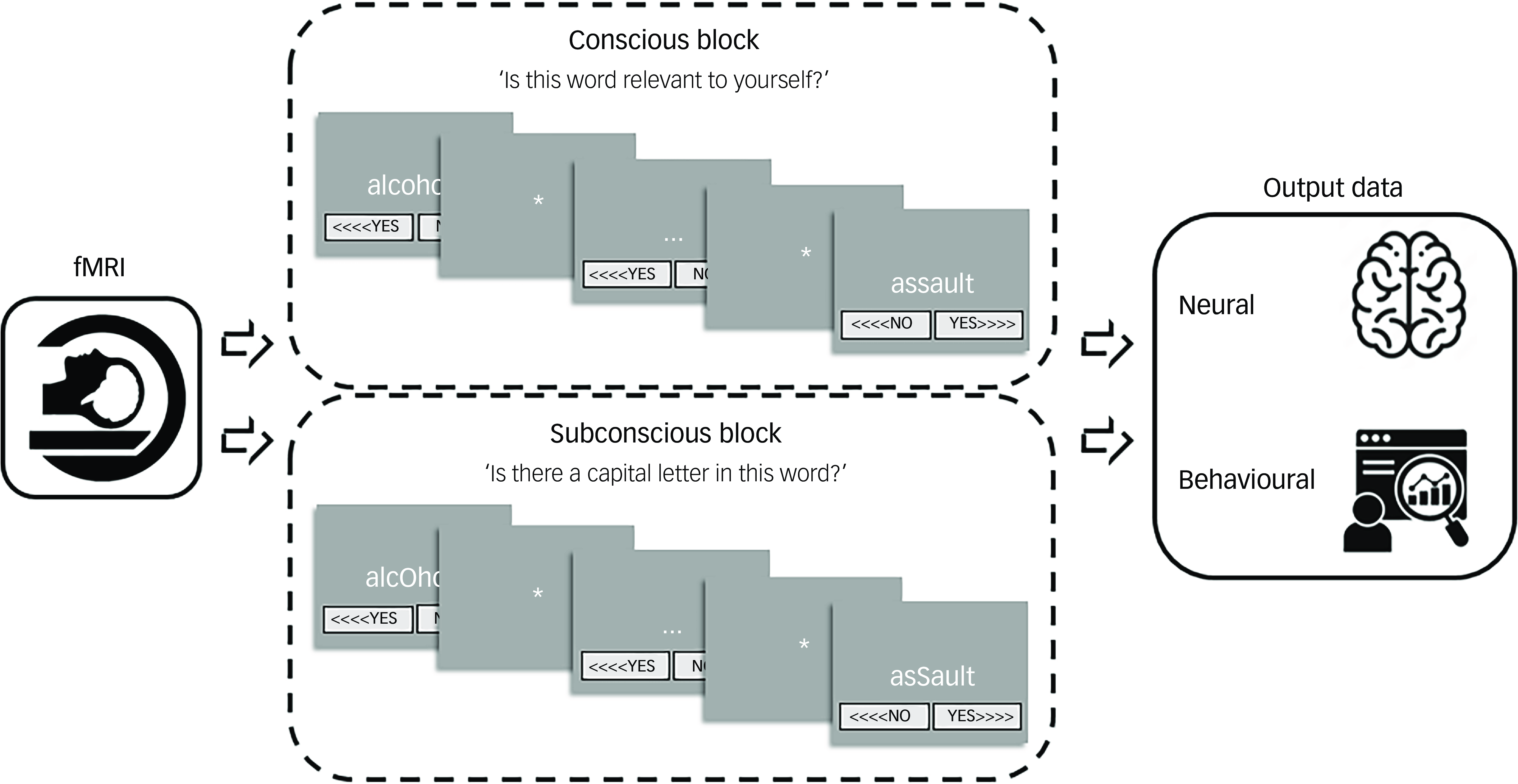

The imaging task was implemented and programmed by S.C. in the software programme Presentation (version 14 for Windows, Neurobehavioral Systems, San Francisco, California, USA; https://neurobs.com/menu_presentation/menu_features/features_overview). This programme was also used to record the participants’ reactions to each word during the brain imaging session. Choice reaction time is a basic measure of processing speed, and constitutes a calculation of the participant’s response time from stimulus presentation to logged response. Reference Whelan22 Slower reaction times indicated greater time between the presentation of the stimulus and the participant’s response, denoting increased mental processing, whereas faster reaction times signified less time taken by the participant to respond, suggesting decreased mental processing and cognitive avoidance. Reference Vissia, Lawrence, Chalavi, Giesen, Draijer and Nijenhuis19 The fMRI task procedure is visualised and detailed in Fig. 2 (adapted with permission from Dimitrova and colleagues Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2 ).

Fig. 2 Brain-imaging session procedure of self-relevance processing. Each task contained a total of five conscious/overt processing (CP) blocks and five subconscious/covert processing (SCP) blocks. The SCP block consisted of the same words included in the CP block but contained capital letters (i.e. asSault). The participants’ task was to decide whether or not there is a capital letter, instead of rating the word in terms of self-relevance and emotional content. There were two different versions of CP/SCP block order to allow for between subject randomisation, randomly allocated one for the trauma-related identity state and one for the trauma-avoidant identity state. Every block contained the self-relevant trauma-related, non-self-relevant trauma-related and non-self-relevant neutral conditions in randomised order within block, i.e. four words from each condition randomly distributed in each block. The reply button allocation was also randomised, sometimes (<>>) and sometimes (<<>) and counterbalanced throughout the task. The word for rating would appear in the centre of the screen for up to 5 s or until the Presentation program logged a response, i.e self-paced termination of the word presentation. Although the task was designed to run at the pace of the participant, the maximum duration of each block was up to 25 min. fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging.

Data analyses

Behavioural data

Presentation log files were extracted, processed and transformed by A.J.L. using R (version 3.4.1 for Windows, R Core Team, Vienna, Austria; https://cran.r-project.org/). IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 24 for Windows, IBM, Armonk, New York, USA; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics) was then used for descriptive and statistical analyses. Participants’ reaction times were analysed using repeated-measures analyses of variance. A four-way factorial design was employed to explore the main effect of consciousness, with participant group being the between-subjects factor (DID-G, DID-S, CTRL). The remaining variables were all within-subject factors: two dissociative identity states (trauma-avoidant identity state, trauma-related identity state), two trial types (conscious/overt processing, subconscious/covert processing (SCP)) and three word types (non-self-relevant neutral (NSn), non-self-relevant trauma-related (NSt), self-relevant trauma-related). Regarding the self-relevance and emotional intensity effect, the same design was employed but, rather than three word types there were only two; for the self-relevance effect we compared between self-relevant and non-self-relevant words (self-relevant trauma-related versus NSt), whereas for the emotional intensity effect we contrasted between trauma-related and neutral words (NSt versus NSn). Simple contrast analyses were conducted to determine the one-tailed direction of the tests, serving as the primary analytical results for the specified hypotheses. Post hoc pairwise comparisons tests were used to determine the directionality of significant differences. P-values were set at 0.05 and corrected for multiple comparisons through Bonferroni’s adjustment. The same factorial designs were also employed for within-group comparisons.

Neuroimaging data

An in-depth overview of the acquisition parameters and preprocessing details has previously been described in detail, in the supplementary materials of Dimitrova and colleagues. Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2 FMRI data were processed and statistically analysed using SPM12 (version 7771 for Windows, Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk) within Matlab (version 9.2.0 for Windows, MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts, USA; https://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html).

For the purposes of statistical analyses, a blocked event-related design was employed. At the first level, a boxcar regressor, aligned with the onset and offset of stimulus presentation, underwent convolution with the canonical haemodynamic response function. At this level, 9 regressors were specified for each session and each identity state plus 4 session-specific constants, totalling 40 regressors per participant. Of the nine regressors there was one low-level baseline condition of no interest, four regressors modelled subconscious/covert processing and four regressors modelled conscious/overt processing. According to processing level, three regressors modelled our conditions of interest, namely the word types NSn, NSt and self-relevant trauma-related, and one regressor, which was of no interest in regard to the current study. Subsequently, image volumes containing parameter estimates pertinent to the current investigation were computed within the self-relevance task blocks and consciousness block manipulation, and taken to the second level of analysis.

At the second level, contrasts of interest were investigated using within-group, one-sample t-tests (for the DID-G group) and between-group, two-sample t-tests to explore the effects of group (DID-G versus CTRL, DID-G versus DID-S). The main effect of consciousness tested participants’ between-identity state increased and decreased brain activation in the overt versus covert level of processing. The effect of self-relevance (self-relevant trauma-related versus NSt) and that of emotional intensity (NSt versus NSn) were investigated using the following comparisons of interest: consciousness effects within identity states (covert versus overt processing in the trauma-avoidant identity state, covert versus overt processing in the trauma-related identity state) and consciousness effects between identity states (overt processing in the trauma-related versus trauma-avoidant identity state, covert processing in the trauma-related versus trauma-avoidant identity state).

An initial threshold of P < 0.05, corrected with family-wise error multiple comparisons for the whole brain, was set with an extent threshold of 8 voxels. Furthermore, brain regions meeting an explorative threshold of P < 0.005 uncorrected were also reported, consistent with previous studies. Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2,Reference Reinders, Willemsen, Vos, den Boer and Nijenhuis3,Reference Reinders, Willemsen, Vissia, Vos, den Boer and Nijenhuis8,Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Quak, Korf, Haaksma and Paans23 Results were restricted by an extent voxel threshold of ≥8, in line with the spatial resolution of the data, to mitigate the risk of type I error following the approach outlined by Bennett and colleagues. Reference Bennett, Wolford and Miller24 Coordinates were extracted from SPM12 with relevant output and label. The labels of the coordinates were cross-referenced by A.I.S. and A.A.T.S.R., using the atlas Siibra Explorer (browser-based, EBRAINS, Watermael-Boitsfort, Belgium; https://atlases.ebrains.eu/viewer/) and the application Brain Tutor 3D (Windows, BrainVoyager, Maastricht, The Netherlands; https://www.brainvoyager.com/products/braintutor.html). The coordinates and labels were further examined in SPM using anatomical visualisation of clusters by means of overlaying a canonical, single-subject T1 image on the sagittal, coronal and axial sections.

Results

Demographics

Participants did not significantly differ in terms of age or education.

Behavioural and brain imaging data

Main effect of consciousness

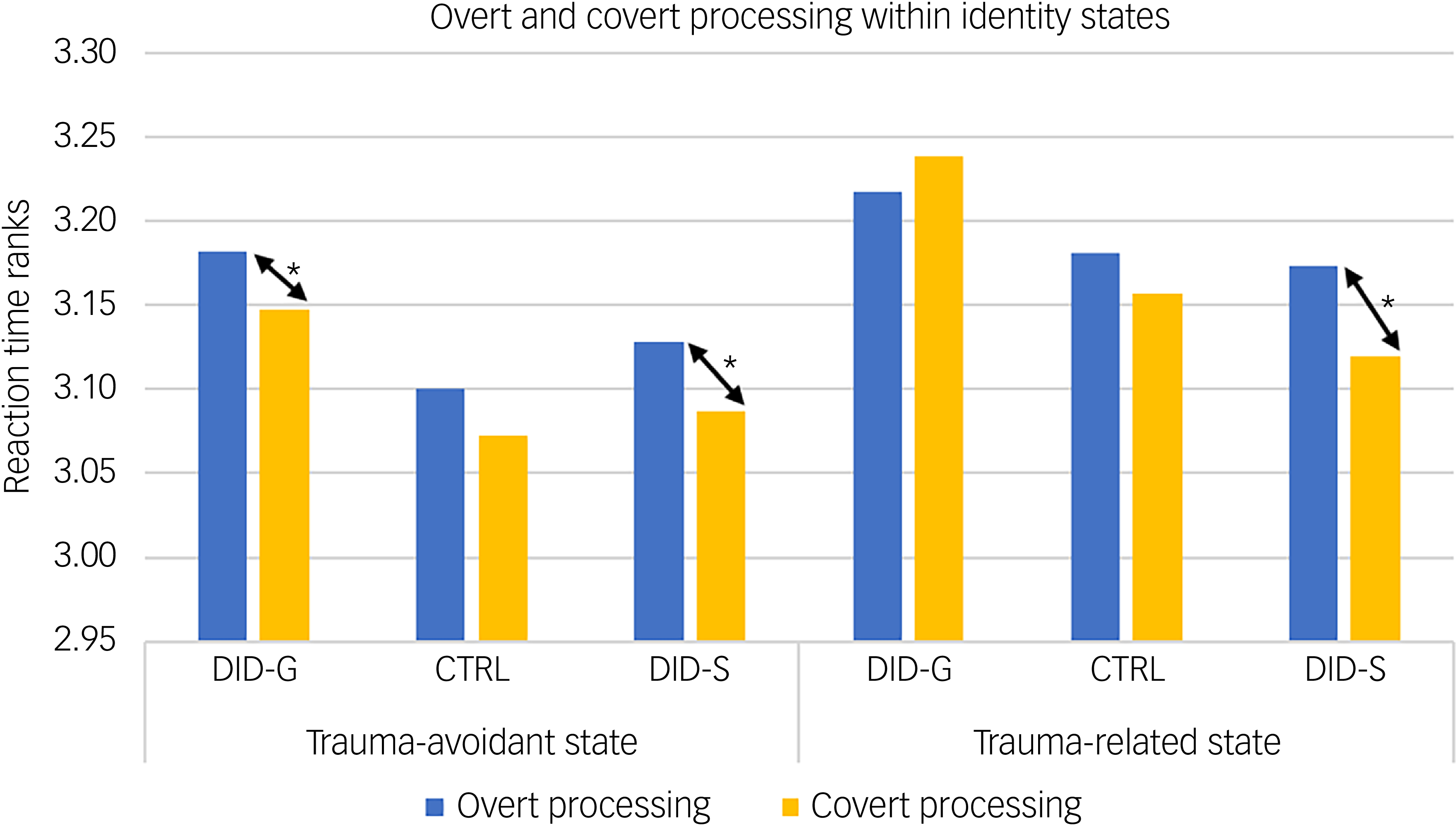

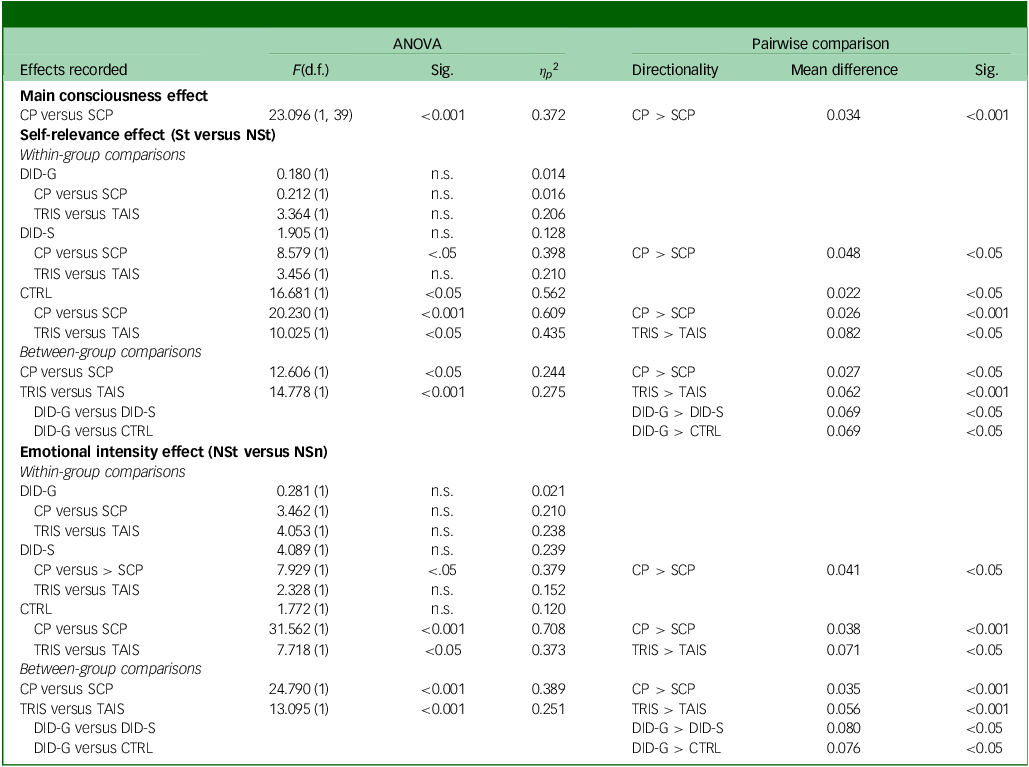

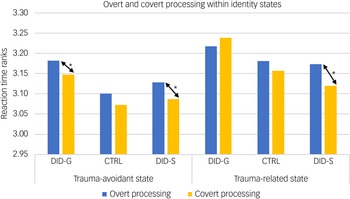

Behavioural data showed a significant main effect of consciousness in participants’ reaction times for self-relevant trauma-related, NSt and NSn words across groups and identity states (see Table 1). Pairwise comparisons revealed slower reaction times in conscious/overt processing compared with subconscious/covert processing (see Table 1, main consciousness effect), especially in the trauma-avoidant identity state for the DID-G group, and in both identity states for DID-S participants (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Mean participant score ranks of response times during overt and covert processing, within identity states. DID-G, genuine/diagnosed dissociative identity disorder; CTRL, paired control group; DID-S, simulated dissociative identity disorder. *0.001 < P < 0.05.

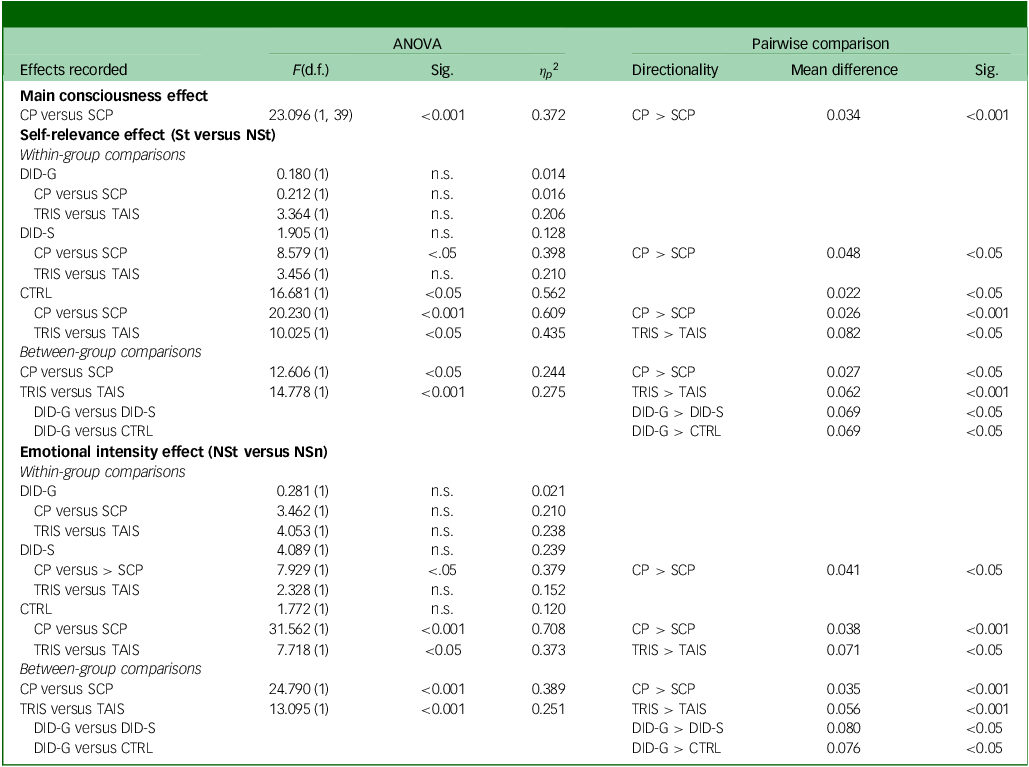

Table 1 Statistical comparisons of behavioural response times between groups, processing blocks and dissociative identity states

ANOVA, analysis of variance; Sig., significance; CP, conscious/overt processing; SCP, subconscious/covert processing; St, self-relevant trauma-related words; NSt, non-self-relevant trauma-related words; DID-G, diagnosed dissociative identity disorder participants; n.s., no significance; TRIS, trauma-related identity state; TAIS, trauma-avoidant identity state; DID-S, simulated dissociative identity disorder participants; CTRL, paired control group; NSn, non-self-relevant neutral words.

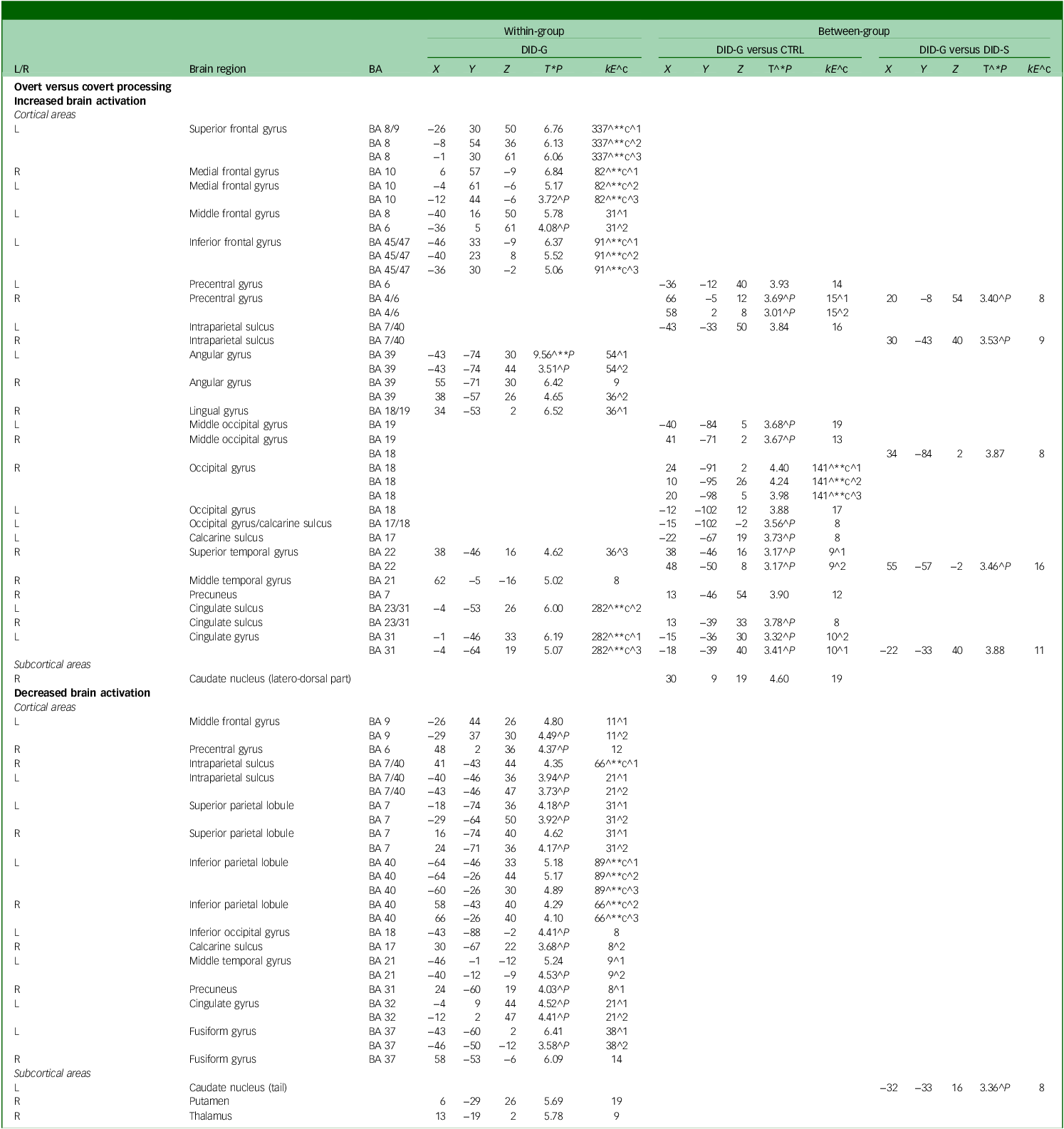

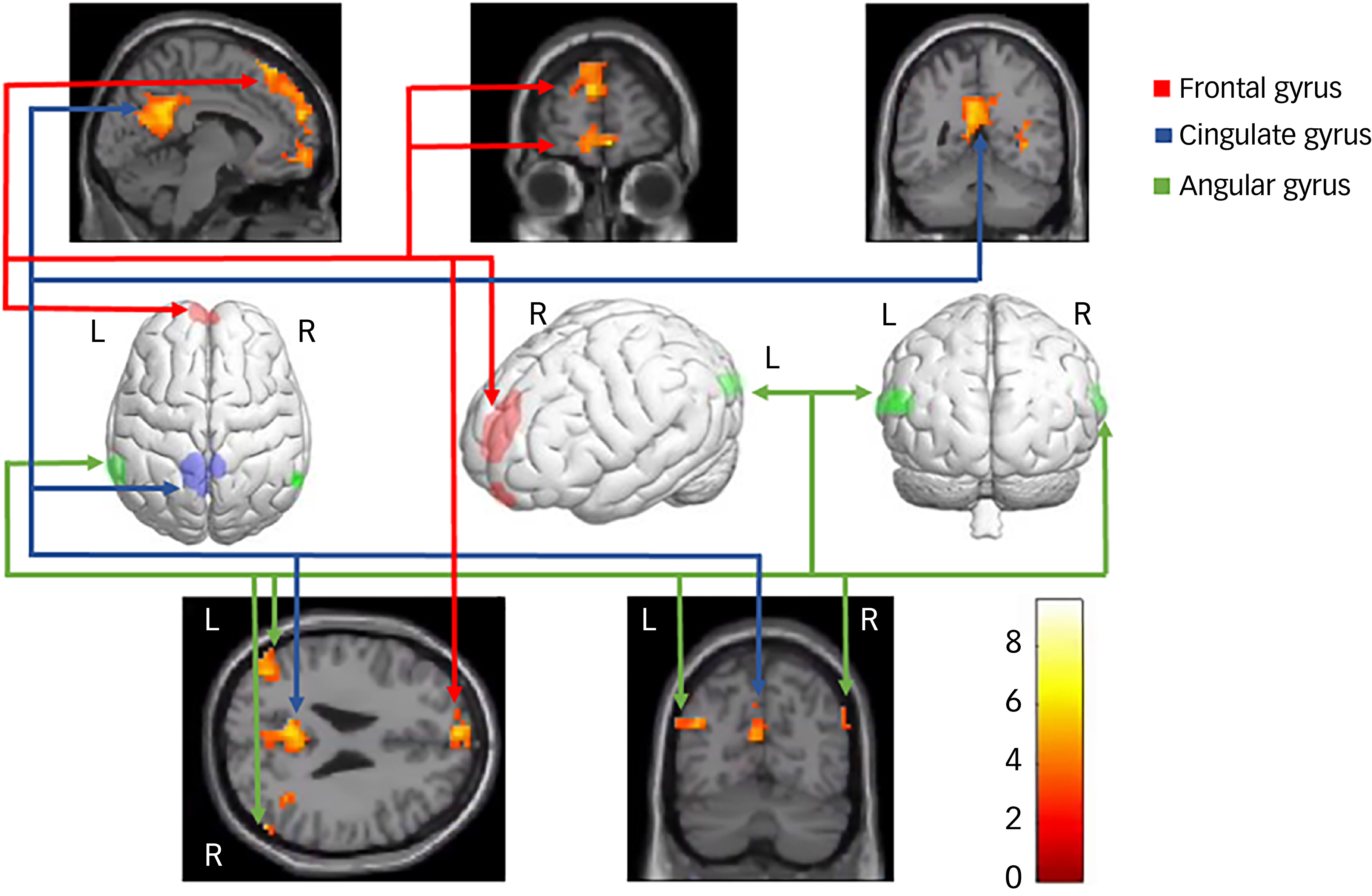

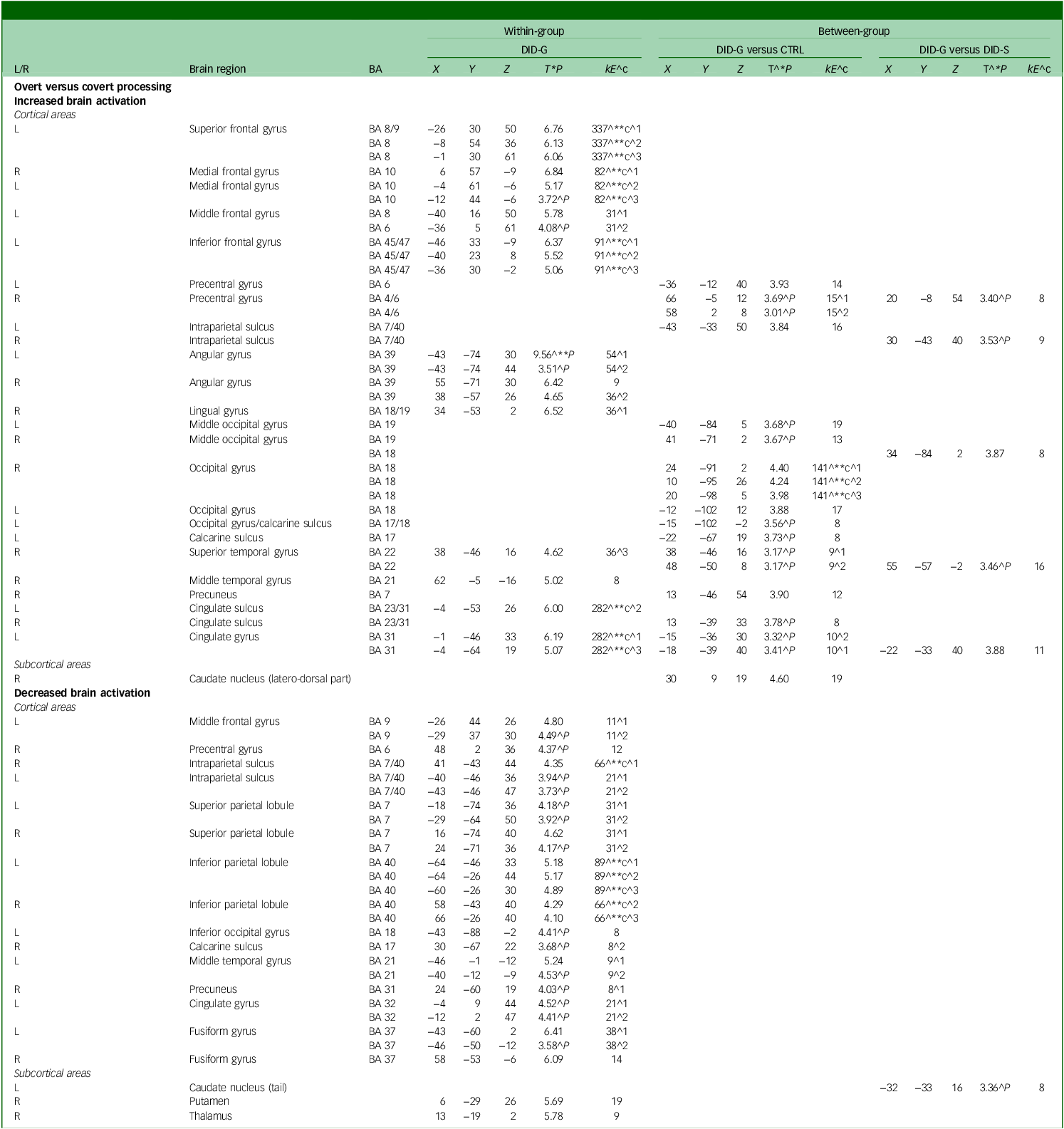

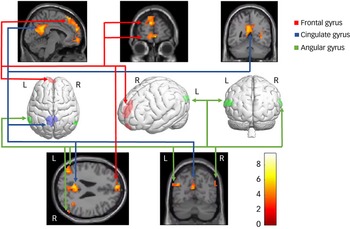

Neural data for the diagnosed DID-G participants showed increased brain activation in the bilateral frontal gyrus, bilateral intraparietal sulcus, bilateral angular gyrus, right lingual gyrus, right temporal gyrus and left cingulate gyrus (see Table 2, Fig. 4 and Appendix B of the supplementary materials). Group comparisons between the DID-G and paired control group (CTRL), as well as between the DID-G and DID-S groups, showed increased brain activation in the bilateral occipital gyrus and bilateral intraparietal sulcus, respectively. Decreased brain activation was found for the DID-G group in the left middle frontal gyrus, right precentral gyrus, bilateral intraparietal sulcus and bilateral superior and inferior parietal lobules, as well as in the right precuneus.

Table 2 Main effect of consciousness: increased and decreased brain activation

DID-G, genuine/diagnosed dissociative identity disorder; CTRL, paired control group; DID-S, simulated dissociative identity disorder; BA, Brodmann area; X, Y, Z, Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates (mm); L/R, left/right side of the brain; T, t-value statistic; kE, cluster size in voxels (one voxel is 26 262 mm).

^1, first peak voxel; ^2, second peak voxel; ^3, third peak voxel; ^**c, 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons at cluster level; ^c, cluster size obtained P = 0.005 uncorrected; ^**, P = 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons at peak level; ^*P, also at 0.001 uncorrected for multiple comparisons at peak level; ^P, only at 0.005 uncorrected for multiple comparisons at peak level.

Fig. 4 Neural correlates of the main effect of consciousness in dissociative identity disorder. L/R, Left/right side of the brain.

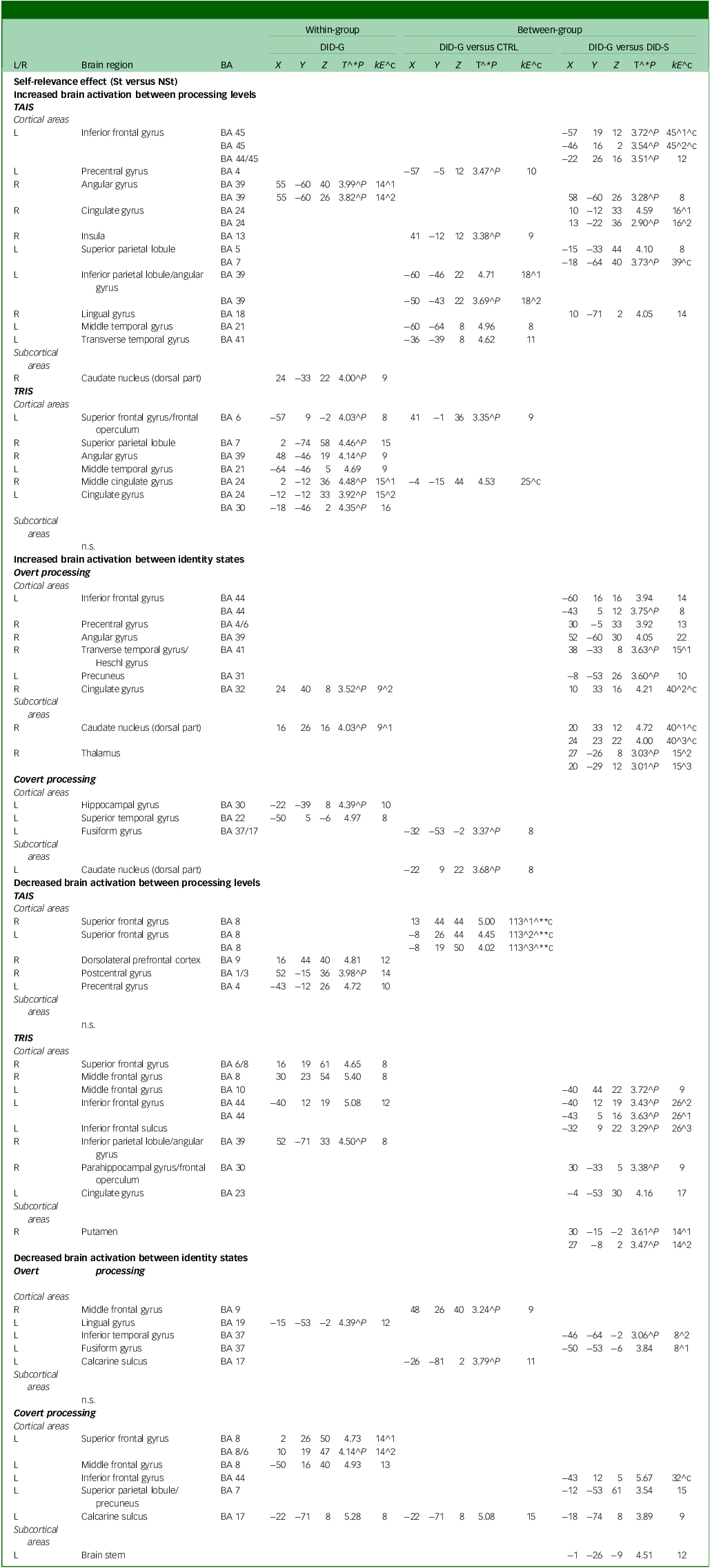

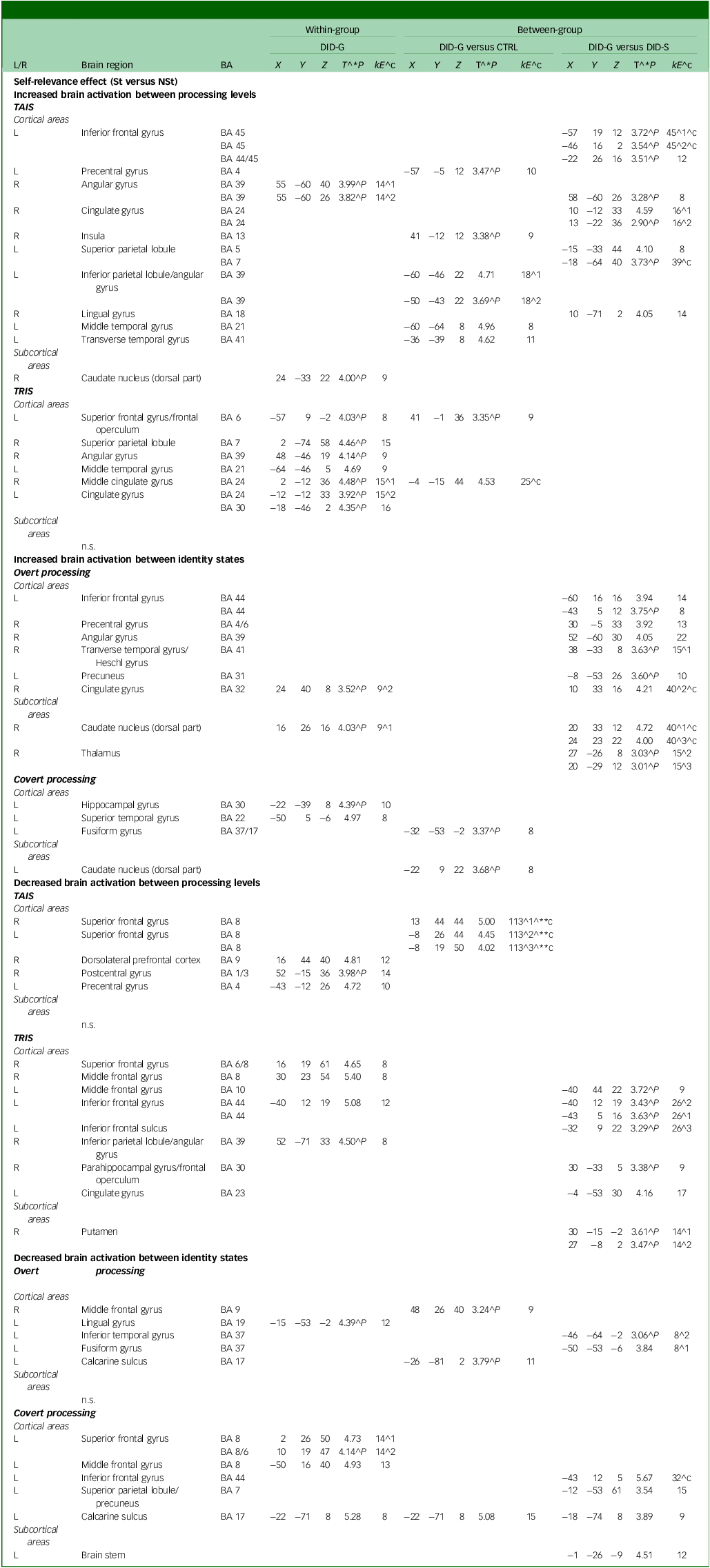

Self-relevance effect: self-relevant trauma-related versus NSt words

Within-group comparisons

Behavioural data showed significant differences in reaction times only for the CTRL group (see Table 1). Post hoc pairwise comparisons showed slower reaction times for self-relevant trauma-related words compared with NSt words. Significant differences between overt and covert processing were found only for DID-S and CTRL participants. Regarding rating differences between the trauma-avoidant identity and -related identity states, only the CTRL group yielded significant results, with slower reaction times for the latter compared with the former (see Table 1).

Neural data obtained during the brain imaging session showed increased brain activation in the left superior frontal gyrus and right superior parietal lobule in the trauma-related identity state of diagnosed DID-G participants (see Table 3). In the covert processing block, there was increase in the left hippocampal gyrus and left superior temporal gyrus. Decreased activation was found in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, right postcentral gyrus and left precentral gyrus while participants were in the trauma-avoidant identity state. Additionally, there was decreased activation in the right superior frontal gyrus, right middle frontal gyrus, left inferior frontal gyrus and right inferior parietal lobule while in the trauma-related identity state, and in the left superior frontal and left middle frontal gyrus during the covert processing block (see Table 3 and Appendix B of the supplementary materials).

Table 3 Self-relevance effect (St versus NSt): increased and decreased brain activation

L/R, left/right side of the brain; BA, Brodmann area; DID-G, genuine/diagnosed dissociative identity disorder; CTRL, paired control group; DID-S, dissociative identity disorder-simulating controls; kE, cluster size in voxels (one voxel is 26 262 mm); (X, Y, Z), Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates (mm); T, t-value statistic; St, self-relevant trauma-related stimuli; NSt, non-self-relevant trauma-related stimuli; TAIS, trauma-aware identity state; TRIS, trauma-related identity state; n.s., no significance.

^1, first peak voxel; ^2, second peak voxel; ^3, third peak voxel. ^**c, 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons at cluster level; ^c, cluster size obtained P = 0.005 uncorrected; ^**, P = 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons at peak level; ^*P, also at 0.001 uncorrected for multiple comparisons at peak level; ^P, only at 0.005 uncorrected for multiple comparisons at peak level.

Between-group comparisons

Behavioural data showed significant between-group effects (F(2, 39) = 4.829, P = 0.013, η p 2 = 0.199). Statistically different reaction times were shown between the two word types (F(1) = 9.216, P = 0.004, η p 2 = 0.191), with pairwise comparisons revealing slower reaction times for self-relevant trauma-related words compared with NSt words (mean difference = 0.011, s.e. = 0.004, 95% CI: [0.004, 0.019], P = 0.004) across groups. Significant differences were observed between overt and covert processing, as well as between trauma-avoidant and -related identity states (see Table 1). Post hoc pairwise comparisons between groups showed slower reaction times in overt processing and in the trauma-related identity state. Pairwise comparisons also showed that DID-G participants exhibited slower reaction times than the CTRL and DID-S groups.

Neural data of group comparisons between the DID-G and CTRL groups showed increased brain activation in the left precentral gyrus, right insula, left inferior parietal lobule/angular gyrus, left middle temporal gyrus and left transverse temporal gyrus in the trauma-avoidant identity state, and in the left superior frontal gyrus in the trauma-related identity state. Decreased activation was observed in the bilateral superior frontal gyrus in the trauma-avoidant identity state, and in the right middle frontal gyrus during the overt processing block (see Table 3).

Comparisons between the DID-G and DID-S groups showed increased activation in the left inferior frontal gyrus, left superior and inferior parietal lobule, mainly in the trauma-avoidant identity state. Increased activation was found in the left inferior frontal gyrus, right precentral gyrus, right transverse temporal gyrus and left precuneus only in the overt processing block. Decreased activation was found in the trauma-related identity state in the left middle and inferior frontal gyrus and sulcus, as well as in the right parahippocampal gyrus/frontal operculum. Decreased activation was observed in the left inferior temporal gyrus in the overt processing block, and in the left inferior frontal gyrus, left superior parietal lobule/precuneus and left calcarine sulcus in the covert processing block (see Table 3 and Appendix B of the supplementary materials).

Emotional intensity effect: NSt versus NSn words

Within-group comparisons

Behavioural analyses revealed no within-group differences between these two word types (see Table 1). Significant differences between overt and covert processing were found for the DID-S and CTRL groups. Comparisons between the trauma-avoidant and -related identity states showed differences only for the CTRL group, with slower reaction times in the latter.

Post hoc emotional intensity assessment of the imaging data showed increased activation in the bilateral superior frontal gyrus, left middle frontal gyrus, bilateral precentral and postcentral gyrus, left anterior insula, left superior parietal lobule, left supramarginal gyrus, right superior and left middle/lateral occipital gyrus, right cuneus and left calcarine sulcus, but only in the trauma-related identity state (see supplementary Table 1). Increased activation in the bilateral superior frontal gyrus, left middle and inferior frontal gyrus, bilateral precentral gyrus, right postcentral gyrus, left anterior insula, bilateral superior parietal lobule, bilateral precuneus, right lateral and left occipital gyrus and bilateral calcarine sulcus was observed in the covert processing block. Decreased activation in the trauma-avoidant identity state was shown in the left occipital gyrus and right occipital gyrus/calcarine sulcus. Decreased activation was found in the right superior frontal gyrus, left middle frontal gyrus and right cuneus/calcarine sulcus in the overt processing block (see supplementary Table 1 and Appendix B of the supplementary materials).

Between-group comparisons

Behavioural data revealed no between-group differences in reaction times between the two word types (F(1) = 0.039, P = 0.845, η p 2 = 0.001). However, significant differences were shown between the overt and covert processing blocks, and between the trauma-avoidant and -related identity states (see Table 1). Post hoc pairwise comparisons showed slower reaction times for DID-G participants compared with the CTRL and DID-S groups. Slower reaction times were found for overt processing and trauma-related identity state.

Neural activity comparisons between the DID-G and CTRL groups showed increased activation in the left superior frontal gyrus and left inferior temporal gyrus in the trauma-avoidant identity state (see supplementary Table 1). In the trauma-related identity state there was increased activation in the bilateral precentral gyrus, bilateral postcentral gyrus, left supramarginal gyrus, right superior occipital gyrus, right cuneus and left calcarine sulcus. Increased activation was found in the right precentral gyrus in the overt processing block, and in the bilateral superior frontal gyrus, left inferior frontal gyrus, right postcentral gyrus and left lateral occipital gyrus in the covert processing block. Decreased activation was observed in the right middle temporal gyrus only in the trauma-avoidant identity state. In the overt processing block, decreased activation was found in the left middle frontal gyrus and right superior parietal lobule/supramarginal gyrus.

Neural data comparisons between the DID-G and DID-S groups showed increased activity in the bilateral superior and middle frontal gyrus, bilateral precentral and postcentral gyrus, bilateral superior parietal lobule, left supramarginal gyrus, bilateral occipital gyrus, right superior and transverse temporal gyrus and bilateral parahippocampal gyrus/frontal operculum, mainly in the trauma-related identity state. In the covert processing block, increased activation was observed in the right superior frontal gyrus, left middle and inferior frontal gyrus, bilateral precentral gyrus, right postcentral gyrus, left anterior insula, bilateral superior parietal lobule/precuneus and left supramarginal gyrus/inferior parietal lobule. Decreased activation was found in the left precentral gyrus and right postcentral gyrus only in the trauma-avoidant identity state. In the overt processing block, there was decreased activation of the right superior frontal gyrus, left middle frontal gyrus, right precentral gyrus, left precentral/postcentral gyrus, left superior parietal lobule, left parietal operculum, left lateral occipital gyrus/cuneus and right calcarine sulcus (see supplementary Table 1 and Appendix B of the supplementary materials).

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the effect of overt and covert identity state-dependent processing of self-relevance knowledge in participants with diagnosed DID, DID-simulating controls and a paired group of PTSD and healthy controls. Our primary finding was that there were significant differences between overt and covert processing of self-relevant trauma-related words, with slower reaction times and increased brain activation for overt processing. Our second most important finding was that the elevated brain activity observed during overt self-relevance processing was mainly observed in the frontal gyrus in individuals with DID as compared with DID simulators and the paired control group, and was independent of dissociative identity state.

With regard to the overall effect of consciousness in the trauma-avoidant identity state of individuals with DID, the behavioural data show significantly slower reaction times in overt processing compared with covert which, paired with the increased frontal and parietal brain activation, indicates heightened cognitive involvement when consciously perceiving self-relevant words. Although the current findings support previous research proposing increased cognitive control and inter-identity avoidance in the trauma-avoidant identity state of DID, Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2,Reference Reinders, Willemsen, Vos, den Boer and Nijenhuis3,Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Paans, Korf, Willemsen and Den Boer5,Reference Reinders, Willemsen, Vissia, Vos, den Boer and Nijenhuis8,Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Quak, Korf, Haaksma and Paans23 they are at odds with other studies. In particular, a study by Hermans and colleagues Reference Hermans, Nijenhuis, Van Honk, Huntjens and Van Der Hart25 showed faster response times to emotional stimuli covertly presented in individuals diagnosed with DID in the trauma-avoidant identity state, and slower response times in their trauma-aware identity state, in direct contrast with the response patterns of the included control groups. Reference Hermans, Nijenhuis, Van Honk, Huntjens and Van Der Hart25 Moreover, a study by Schlumpf and colleagues Reference Schlumpf, Nijenhuis, Chalavi, Weder, Zimmermann and Luechinger10 found longer reaction times to masked neutral faces for participants with DID when they were in a trauma-aware identity state as compared with when in a trauma-avoidant identity state. Lebois and colleagues Reference Lebois, Wolff, Hill, Bigony, Winternitz and Ressler13 used a mirror confrontation task and found that individuals with DID demonstrated reduced self-relevance ratings of their own face when presented covertly, as compared with control participants. The discrepancy of our findings relative to prior research could be attributed to methodological differences – that is, the subject-specific nature of the words used in our study as compared with standardised Reference Schlumpf, Nijenhuis, Chalavi, Weder, Zimmermann and Luechinger10,Reference Lebois, Wolff, Hill, Bigony, Winternitz and Ressler13,Reference Hermans, Nijenhuis, Van Honk, Huntjens and Van Der Hart25 and individualised Reference Lebois, Wolff, Hill, Bigony, Winternitz and Ressler13 facial stimuli. Furthermore, Lebois and colleagues Reference Lebois, Wolff, Hill, Bigony, Winternitz and Ressler13 did not investigate the effect of distinct dissociative identity states on participants’ face perception. Nevertheless, our outcomes complement all aforementioned studies by emphasising the central role of consciousness of self-relevance and emotional perception in individuals with DID.

Results from our brain imaging data further support overt and covert processing differences, especially through the activation of frontal parts of the brain. Earlier imaging and electroencephalography studies have indicated marked neural response differences in relation to overt and covert processing between individuals with DID and healthy or simulating controls Reference Schlumpf, Nijenhuis, Chalavi, Weder, Zimmermann and Luechinger10,Reference Schäflein, Mertens, Lejko, Beutler, Sattel and Sack12 in the frontal, precentral, temporal and occipital gyri. Similarly, research on overt and covert processing in PTSD and its dissociative subtype reported significant differences in brain activation patterns following participants’ exposure to masked and unmasked emotional faces Reference Rabellino, Densmore, Frewen, Théberge and Lanius26 or general images. Reference Hendler, Rotshtein, Yeshurun, Weizmann, Kahn and Ben-Bashat27 In accordance with our findings, overt exposure to emotional stimuli in PTSD showed increased activity in frontal regions, including the bilateral basal forebrain and bilateral supplementary motor area. Reference Rabellino, Densmore, Frewen, Théberge and Lanius26 Studies with PTSD participants have also demonstrated decreased activation of the medial prefrontal cortex, Reference Shin, Wright, Cannistraro, Wedig, McMullin and Martis28 which encompasses regions corresponding to our findings such as the superior and middle frontal gyri. Furthermore, covert exposure to emotional images and trauma-related words showed increased activation in the visual cortex, Reference Hendler, Rotshtein, Yeshurun, Weizmann, Kahn and Ben-Bashat27 including the occipital gyrus and calcarine sulcus, which is in agreement with our results. For further discussion of individual brain regions please refer to Appendix B of the supplementary materials.

Our outcome of frontal brain activity, paired with the increased activation in the intraparietal sulcus and parietal regions, corresponds with the frontoparietal network model, which has been implicated in cognitive control mechanisms Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2,Reference Marek and Dosenbach29 including working memory processes. Reference Vissia, Lawrence, Chalavi, Giesen, Draijer and Nijenhuis19 Notably, the frontal and parietal regions have also been associated with working memory and attention, Reference Li, Cai, Liu, Li, Feng and Chen30 further underlining their central role in cognitive processes. Increased frontal and parietal activity has further been observed in studies of PTSD Reference Weber, Clark, McFarlane, Moores, Morris and Egan31 and complex PTSD. Reference Breukelaar, Antees, Grieve, Foster, Gomes and Williams32 Reinders and colleagues Reference Reinders, Willemsen, den Boer, Vos, Veltman and Loewenstein4 also proposed similar areas as a PTSD-based neurobiological model of DID with a strong involvement of parietal regions, in particular the intraparietal sulcus, which has also been confirmed by more recent research. Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2 Current outcomes further support this notion of increased cognitive control over, and mental avoidance of, trauma-related knowledge Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2,Reference Breukelaar, Antees, Grieve, Foster, Gomes and Williams32 in the trauma-avoidant identity state Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2,Reference Reinders, Willemsen, Vos, den Boer and Nijenhuis3,Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Paans, Korf, Willemsen and Den Boer5,Reference Reinders, Willemsen, Vissia, Vos, den Boer and Nijenhuis8,Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Quak, Korf, Haaksma and Paans23 leading to increased reaction time to trauma-related words.

The frontal lobe, and particularly the prefrontal cortices, have also been implicated in another PTSD-based neurobiological model previously proposed, the corticolimbic inhibition network. Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Paans, Korf, Willemsen and Den Boer5,Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Quak, Korf, Haaksma and Paans23,Reference Lebois, Ross and Kaufman33 Specifically, this model proposes that, especially in the dissociative subtype of PTSD, emotional arousal leads to increased activation of the prefrontal cortex which, in turn, inhibits the activation of limbic structures such as the hippocampus and amygdala, thus reducing the emotional experience. Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Schmahl and Bremner34 Moreover, morphological abnormalities in the hippocampal area have previously been observed in individuals diagnosed with DID and associated with childhood maltreatment and dissociative symptomatology. Reference Chalavi, Vissia, Giesen, Nijenhuis, Draijer and Cole16 Our results corroborate these previous findings because they show that the hippocampus was activated in the trauma-related identity state of participants with DID. Higher neural activation was also detected in the right parahippocampal gyrus in the trauma-related identity state, in line with earlier studies. Reference Schlumpf, Nijenhuis, Chalavi, Weder, Zimmermann and Luechinger10 Contrary to that model’s proposal of decreased activity in the insula, Reference Reinders, Willemsen, Vos, den Boer and Nijenhuis3,Reference Reinders, Willemsen, den Boer, Vos, Veltman and Loewenstein4,Reference Lebois, Ross and Kaufman33,Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Schmahl and Bremner34 our findings show increased insula activation, supporting the majority of literature findings, as reported in the systematic review by Roydeva and Reinders. Reference Roydeva and Reinders35

The outcomes of the current study hold significant clinical implications for the therapeutic treatment of DID, and provide valuable insights for future research in this field. As indicated by our findings, increased cognitive control during overt processing in the trauma-avoidant identity state indicates a way in which individuals with DID process trauma-related information, and highlights that interventions for DID could initially focus on addressing this cognitive avoidance. Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2 Moreover, our findings corroborate earlier outcomes on the neural biomarkers of DID Reference Roydeva and Reinders35 and support PTSD-based neurobiological models, Reference Reinders, Willemsen, den Boer, Vos, Veltman and Loewenstein4,Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Paans, Korf, Willemsen and Den Boer5,Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Quak, Korf, Haaksma and Paans23,Reference Marek and Dosenbach29,Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Schmahl and Bremner34 which emphasise the trauma-related nature of DID Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2 and, ultimately, the trauma-informed practices that clinicians should adopt in their assessments and interventions. In particular, approaches such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2,Reference Marek and Dosenbach29,Reference Roydeva and Reinders35 have previously been proposed for the treatment of disorders with increased frontoparietal activity. Real-time fMRI neurofeedback training has also been recommended as an intervention for emotion regulation, through activation modulation of the frontoparietal network. Reference Garrison, Saviola, Morgenroth, Barker, Lührs and Simons36 Although research is limited, this intervention’s effectiveness has been shown in studies including individuals with the dissociative subtype of PTSD. Reference Nicholson, Rabellino, Densmore, Frewen, Paret and Kluetsch37,Reference Panisch and Hai38 We suggest that future studies should investigate the efficacy of neurofeedback in altering the activation of the frontoparietal network in individuals diagnosed with DID.

The strength of our research study is the implementation of an event-related design while displaying trauma-related words rather than scripts (as in script-driven imagery studies Reference Reinders, Willemsen, Vos, den Boer and Nijenhuis3–Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Paans, Korf, Willemsen and Den Boer5,Reference Reinders, Nijenhuis, Quak, Korf, Haaksma and Paans23 ), which is more efficient in detecting transient neural responses in functional brain imaging studies. Another important strength of our study is the inclusion of multiple control groups, which allowed us to compare distinct brain activation patterns between diagnosed DID subjects and clinically healthy and simulating populations.

A limitation of our study is that our sample could be considered small, with limited statistical power. However, our sample is of similar size to others in the field and yielded significant outcomes. Furthermore, we used subject-specific self-relevant and trauma-related stimuli rather than standardised ones, which counteracts the limited sample size through the individualised investigation of our participants’ unique experiences. Lastly, the consistency of our findings with prior research in independent samples further affirms the validity of our outcomes (see also Reference Dimitrova, Lawrence, Vissia, Chalavi, Kakouris and Veltman2 ). Another limitation of our study is that our specific design does not inform on intrusive phenomena in DID, but was tailored to explore behavioural and neural responses to self-relevant trauma-related knowledge. Future research should disentangle the issue of whether mental avoidance is relevant only to such material Reference Daniels, Hegadoren, Coupland, Rowe, Neufeld and Lanius39 or whether it is an escape from an identity state, because identity states may be ‘phobic’ to each other. Reference Şar40 The results of such a study might offer further convergence on treatment recommendations.

In conclusion, our study reaffirms previous findings showing that overt self-relevance processing is characterised by slower reaction times and increased brain activity than covert processing, emphasising heightened cognitive control in the trauma-avoidant identity state of individuals with DID. This is mediated by increased activation of frontoparietal regions, associated with emotional memory suppression or avoidance, and the inhibition of limbic structures involved in emotional processing. These regions have also been highlighted in PTSD and therewith corroborate the notion that DID is a trauma-based disorder. Our study further emphasises that individuals with DID engage in activation of the frontoparietal network as a mechanism for mitigating the emotional impact of overtly presented subject-specific, trauma-related words, suggesting a neurobiological coping mechanism to manage severe trauma-related situations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10914

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, A.A.T.S.R., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

Valerie Sinason, Founder and Former Director of the Clinic for Dissociative Studies, is acknowledged for support. The authors also thank Drs Nel Draijer and Ellert Nijenhuis for participant inclusion, as well as all the participants and their therapists.

Author contributions

A.I.S.: writing of the original and all subsequent drafts, methodology design, data curation, analysis and interpretation. A.J.L.: methodology design, data curation and analysis. L.I.D.: methodology design, data interpretation, draft reviewing and editing. E.M.V.: data curation, draft reviewing and editing. S.C.: data curation, draft reviewing and editing. D.J.V.: work supervision, draft reviewing and editing. A.A.T.S.R.: work conception and supervision, draft reviewing and editing, data and funding acquisition, data interpretation, final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

This paper represents independent research part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The authors thank The International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation for support from their Education and Research Fund. A.A.T.S.R. and this research were supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (www.nwo.nl), grant no. 451-07-009. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.