Introduction

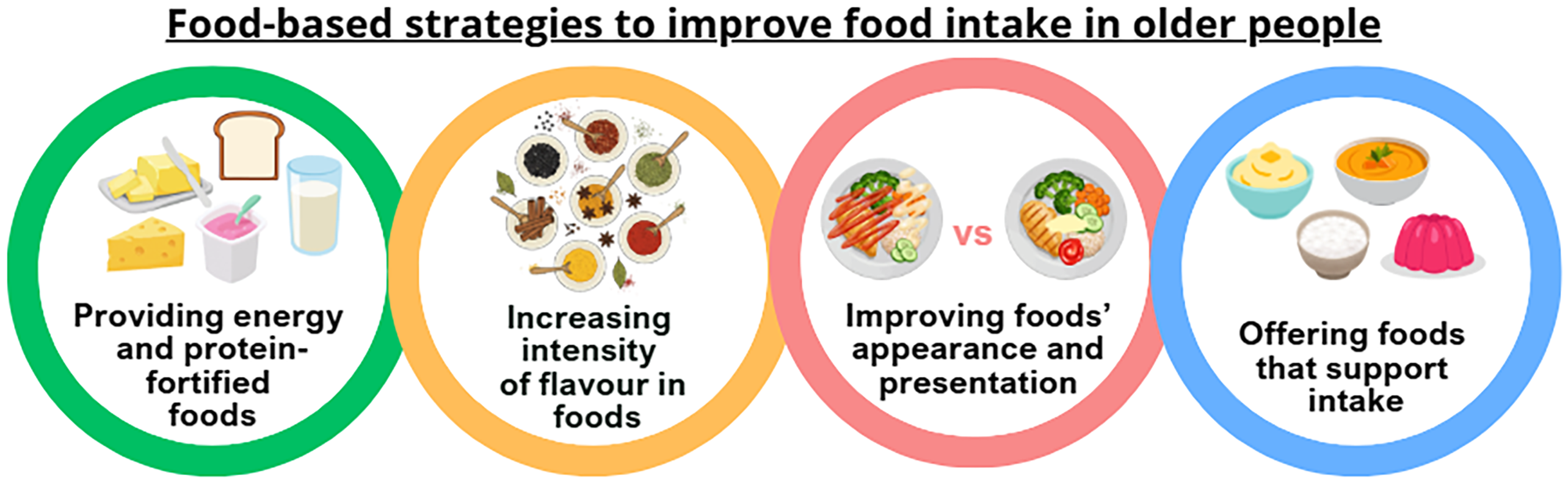

Malnutrition persists as a significant clinical and public health challenge among the elderly population in the UK. Approximately 1.3 million adults aged 65 and older are either malnourished or at risk, with an overwhelming 93% living within the community setting(1). Additionally, one-third of individuals in this age group are at risk of malnutrition upon hospital admission(2). Implementing effective food-based interventions to prevent or manage protein-energy malnutrition could greatly enhance health outcomes, improve quality of life, and substantially reduce healthcare demands and costs(Reference Stratton, Hackston and Longmore3). This review focuses on exploring dietary strategies to promote better food intake among older people (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Outline food-based strategies to improve food intake in older people.

Provision of energy and protein-fortified foods

Oral nutrition support provides additional nutrition to those who are at risk of malnutrition or malnourished(4), which can be via food fortification to increase the energy and protein content of foods without increasing the volume, extra snacks, nourishing fluids, or oral nutritional supplements(Reference Cawood, Stratton, Gandy and Gandy5). These approaches have been shown to positively impact upon an individual’s nutritional status(Reference Elia, Normand and Norman6).

A systematic review carried out by Mills et al(Reference Mills, Wilcox and Ibrahim7) suggested that energy- and protein-based fortification as well as supplementation could be more effective to increase food intake amongst older inpatients compared with usual nutritional care (standard hospital menus). Six out of the ten studies included showed a significant increase in intake of energy (250–450 kcal per day) or protein (12–16g per day) when using either energy or protein-based fortification and supplementation. In addition, two studies using combined energy and protein fortification concluded a significant increase in both energy and protein intake compared to the standard nutritional care(Reference Mills, Wilcox and Ibrahim7). These results support findings from a previous systematic review which aimed to determine the effects of dietary enrichment with conventional foods on energy and protein intake in older adults(Reference Trabal and Farran-Codina8).

A more recent systematic review with meta-analyses focusing on residents living in nursing homes, showed that fortified menus as part of a food-first approach, may significantly increase energy and protein intakes compared with standard menus in nursing homes(Reference Sossen, Bonham and Porter9). A variety and combination of ingredients used in the fortification process, included cream, butter, milk drinks, smoothies, yoghurts, puddings, and cheese. However, benefits to weight and nutritional status of residents were only recorded in some studies.

A 12-week nutritional intervention study by Smoliner et al(Reference Smoliner, Norman and Scheufele10), which included 65 nursing home residents, showed that those in the fortified diet group had higher protein intakes (74.3g/d) in comparison to those who consumed a standard diet (62.6g/d). However, energy intake was similar in both groups (1782.3 kcal/d versus 1668.8kcal/d, not statistically significant). Although protein intake was higher in the fortified diet group, both groups saw improvements in body weight, BMI, and mini nutritional assessment (MNA) scores but not fat free mass or handgrip strength(Reference Smoliner, Norman and Scheufele10). Furthermore, a recent systematic review revealed that although protein and energy enriched foods increased energy and protein intakes in older people, no strong evidence was observed on improvement on body weight or BMI(Reference Geny, Petitjean and Van Wymelbeke-Delannoy11).

It is generally agreed that older adults have higher protein requirements compared to younger adults(Reference Bauer, Biolo and Cederholm12,Reference Chernoff13) , however recommendations vary between countries, and in some countries differ between healthy older adults and older adults considered nutritionally vulnerable. Despite this, protein is a macronutrient that should prioritised in the diet’s of older adults to ensure they adequately meet demands. While incorporating protein-enriched foods in the diet is a way to increase protein intake, it may be deemed counterproductive if barriers to intake are not addressed and appropriate strategies are not implemented to mitigate their impact. Without such measures, protein requirements may not be met by this group.

These barriers and strategies to combat them are now discussed. Firstly, fortified foods are not always acceptable to all older adults(Reference van der Zanden, van Kleef and de Wijk14,Reference van der Zanden, van Kleef and de Wijk15) . An online survey, which included 341 consumers aged 58–87 years, evaluated the acceptance of protein-enriched food products(Reference van der Zanden, van Kleef and de Wijk15). Overall, respondents reported low willingness to purchase protein-enriched foods and indicated that they preferred to consume more protein-rich conventional foods, should they need to increase their protein intake(Reference van der Zanden, van Kleef and de Wijk15). Their reluctancy stemmed from the novelty and uncertainty of the healthfulness of protein-enriched products, which aligns with the theory that the acceptance of unfamiliar foods is low among the elderly population group(Reference Laureati, Pagliarini and Calcinoni16,Reference McKie, MacInnes and Hendry17) .

Offering older people protein-fortified foods that they are familiar with may be a possible solution to increase protein intake as well as total energy intake. A randomised controlled trial investigated the effects of 6 weeks protein-fortified butter cookie supplementation on weight gain in 175 adults aged 70 years and above living in nursing homes(Reference Pouyssegur, Brocker and Schneider18). The choice of food for the study was based on a preliminary study that showed that older people enjoyed the taste and texture of the cookies(Reference Pouyssegur, Brocker and Schneider18). The findings indicated an increase in average body mass in the protein-fortified group compared to control, which was maintained 1, and 3 months after the supplementation period. Additionally, there was a positive impact of protein-fortified cookie supplementation on secondary outcome measures, such as appetite, and presence of pressure ulcers(Reference Pouyssegur, Brocker and Schneider18).

Another study showed that enriching regular food items with protein can be effective in increasing protein intakes of older adults(Reference Beelen, de Roos and de Groot19). Beelen et al.(Reference Beelen, de Roos and de Groot19) developed a variety of protein-enriched foods such as bread, soups, instant mashed potatoes, and fruit juice in the menu to substitute into older residents’ normal diet. Protein intake increased by 11.8 g/d, from 0.96 to 1.14 g/kg/d yet the intake of energy and other macronutrients did not change significantly. The sample size for this study was small (n = 22) and only involved institutionalised older adults, therefore, further research is warranted including free-living older adults.

The FortiPhy project aimed to develop new food solutions with community-dwelling older adults, through co-creation and participatory approaches, that allowed them to fortify their own favourite foods at home(20). Foods that older adults regularly consumed in the UK were mapped across datasets including the UK National Dietary and Nutrition Survey and the Food and You Survey, alongside data purchased from market research consultancy, Kantar market(Reference Smith, Clegg and Methven21). This study highlighted certain foods are particularly suitable for fortification(Reference Smith, Clegg and Methven21) due to the large role they play in older adults’ diets, it also emphasised the need for fortification where some meals during the day were naturally lower in protein than others (for example breakfast and lunch). As such it is important to be able to fortify a range of meals to ensure protein intake is being achieved throughout the day in a ‘pulse-feeding’ pattern(Reference Arnal, Mosoni and Boirie22). Following this food mapping, to explore healthy older adults’ (age 70 +) acceptability and preferences for at-home protein fortification, discussions with older adults (n = 37) and caregivers of older adults (n = 15) were undertaken(Reference Smith, Methven and Clegg23). Findings showed that older adults were unaware of the importance of protein in ageing and did not have a desire to fortify their foods themselves at present. Yet, they were positive regarding the concept and highlighted the importance of taste, familiar ingredients, and preferred preparation methods. Cultural preferences across countries were identified as having the most influence on the liking of fortified meals. Simultaneously, high-protein ingredients (n = 140) were reviewed and screened for sensory, nutritional, food technology, and regulatory characteristics, and two high-protein ingredients were selected: a commercial milk protein powder (over 85% protein) and organic soya mince (extruded product with 52% protein)(Reference Geny, Koga and Smith24). Common food matrices that could serve as relevant candidates for fortification were identified through previous work(Reference Arnal, Mosoni and Boirie22) and 4-day food diaries collected from 65 older adults in France, Norway, and the UK. Eight dishes were selected for recipe fortification and paired with high-protein ingredients (+ 6 to 11 g of protein per portion, mean = 8.1, SD = 2.3). The uniqueness of this study is that the protein-fortified recipes were prepared and tested by older adults in the three countries, in their own homes, and assessed for ease-of-use and acceptability (> 70 years; n = 158). Participants indicated that they found the recipes easy to follow and to prepare themselves(Reference Geny, Koga and Smith24). The fortified recipes were liked (mean liking from 5.3 to 5.9 on a 7-point scale) and perceived as being easy to chew, moisten (humidify in mouth) and swallow. More than 50% of the participants were willing to make the recipes again in the future and liked the fortified version equally or more to their usual recipes(Reference Geny, Koga and Smith24) highlighting the potential for at-home fortification strategies in community-dwelling older adults if education is provided.

In addition, in view of the lack of awareness of protein among the elderly population group(Reference van der Zanden, van Kleef and de Wijk14,Reference Linschooten, Verwijs and Beelen25) , combining dietary advice about the importance of protein alongside offering protein-enriched food products may help increase protein intake and in turn, reduce the risk of malnutrition. In a randomised, controlled trial carried by Fluitman et al(Reference Fluitman, Wijdeveld and Davids26), it was demonstrated that providing personalised dietary advice aimed at increased protein intake in community-dwelling older people enabled them to increase their protein intakes up to 1.2g/BWkg/day compared to those who were not provided any dietary advice and followed their habitual protein intake of less than 1.0 g/kgBW/day.

Although older people are required to increase their protein intake, there have been previous concerns that it might be counterproductive as protein is considered the most satiating macronutrient, which may suppress appetite and subsequent food intake. However, a meta-analysis, involving 21 studies and 857 participants aged 60 years and above, showed that while acute protein supplementation did suppress appetite in older people, it either had a positive influence or no effect on energy intake(Reference Ben-Harchache, Roche and Corish27). Yet it is worth noting that the review mainly focused on healthy older adults and further research is needed to investigate the influence of protein supplementation among older people who have acute or chronic illnesses, as well as those who are at risk of malnutrition or malnourished.

The methods in which foods are enriched with protein should also be considered from a sensory perspective. For instance, it has been revealed that using whey protein to increase protein content of foods can induce ‘off-flavours’(Reference Norton, Lignou and Bull28) and the addition of pea protein can produce an taste profile which can lead to lower acceptance with regards to taste and overall liking of food(Reference Wu, Miles and Braakhuis29). Therefore, solutions are required to ensure masking of possible unpleasant flavours generated through protein fortification, which may be achieved through flavour modification or enhancement.

Optimising visual appearance and presentation of foods

The appearance and presentation of food is an important sensorial attribute of food among older adults and is a strong determinant of nutritional intake, especially among those with reduced smell sensitivity(Reference Rusu, Badiu and Popescu30,Reference Navarro, Wilund and Milliron31) . One study showed when the presentation of food was improved in the experimental group, the total amount consumed by elderly hospital patients was 19% higher in comparison to those in the control group who received the standard meal, despite reported loss in appetite(Reference Navarro, Wilund and Milliron31). In addition, more participants from the experimental group referred to their meal to be ‘tasty’ in comparison to those in the control group (49.5% v. 33.7%)(Reference Navarro, Wilund and Milliron31). However, the study did not specifically evaluate energy and protein intake as they focused on quantity overall, so it cannot be determined whether energy and protein intakes were increased too.

Ensuring that older adults are presented with foods they are familiar with can help to address and prevent malnutrition(Reference Beelen, de Roos and de Groot19). However, this may not always be possible when foods are texturally modified (e.g. pureed) to aid consumption for those who have dysphagia. Therefore, it is important to consider ways to enhance the appearance of such foods to increase acceptance among older people. One possible way to do this may be shaping or moulding pureed foods. In a 2-week pilot study, 65 elderly patients were provided smooth pureed lunch either as an unmoulded or moulded form(Reference Farrer, Frost and Baldwin32). Results showed that patients significantly increased their oral intake from less than 1/4 eaten to more than 3/4 of the meal, when in the moulded form(Reference Farrer, Frost and Baldwin32). This may suggest the influence of appearance of foods is a driving factor in food intake, but there was insufficient data on whether participants preferred the moulded meals compared to unmoulded meals. It should be noted that this study was unpowered as only 38 and 27 patients in the control and intervention groups were recruited respectively, and data from 50 patients in both the control and intervention groups were required.

In relation to the possibility of moulding or reshaping a pureed food into its original shape as a means to improve its appearance, findings from a semi-structured interview showed that 33.3% of the older people interviewed thought it was a good idea as they expected they would be better able to identify the type of food(Reference Rusu, Badiu and Popescu30). In addition, 8.3% of the participants indicated they thought it would ‘taste better’ when reshaped, and similarly 8.3% thought that they would eat more when the food was reshaped(Reference Rusu, Badiu and Popescu30).

Whilst it is clear that ensuring that visual appearance and presentation of both regular and texture-modified foods are appealing to promote consumption, there are other sensory aspects that may change when foods undergo texture modification, such as reduced flavour intensity(Reference Horie, Kamei and Nishibe33).

Enhancing flavour of foods

Increasing the intensity of flavour, as well as the addition of flavours in food, can increase both liking(Reference Dermiki, Mounayar and Suwonsichon34) and the variety of flavours within an eating experience, which in turn may positively increase food intakes among older adults(Reference Van Wymelbeke, Sulmont-Rossé and Feyen35–Reference Schiffman and Warwick39).

An early study carried out by Schiffman and Warwick(Reference Schiffman and Warwick39) revealed that flavour enhancement led to higher consumption of flavour-enhanced foods compared to non-flavour-enhanced foods among older adults living in nursing homes(Reference Schiffman and Warwick39). It is suggested that older adults’ food intakes can be improved by flavour enhancement using aroma compounds and/or using by using tastants that enhance flavour, such as umami taste that is typified by monosodium glutamate (MSG)(Reference Schiffman40).

It is well established that a reduction of taste and smell acuity is prevalent in older age(Reference Jeon, Hong and Kim41–Reference Boyce and Shone43) and the addition of flavours in food is thought to compensate for these reduced acuities or chemosensory losses. An observational study including elderly hospital patients in Hong Kong showed that the use of natural food flavours, such as ginger and garlic, increased food consumption, with energy and protein intake increased by 13–26% and 15–28%, respectively(Reference Henry, Pang and Hoo44). Despite this, they still did not meet their energy and protein requirements(Reference Henry, Pang and Hoo44).

A study in which 36 institutionalised elderly people and 45 young people, rated their liking for different foods modified in appearance, taste and flavour, showed that the elderly group tended to prefer food in which taste and flavour had been amplified(Reference Laureati, Pagliarini and Calcinoni45). This was observed for both first courses of meals (which were modified with ingredients that produced a complex flavour sensation) and in fruit juice. It was noted in the fruit juice experiment that it was predominantly enhanced taste (sweetness), rather than additional aroma, that produced an increase in the older people’s liking(Reference Laureati, Pagliarini and Calcinoni45).

Flavour enhancement may be helpful for older adults with neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease(Reference Pouyet, Giboreau and Schwartz37,Reference Thomas, Boobyer and Borgonha46) . Kimura et al(Reference Kimura, Waki and Saito47) explored whether the addition of sauces affected finger-foods intake among Japanese elderly patients with dementia in two experiments. In the first and second experiment they used chocolate and agave syrups, respectively, as sauce samples. It was found that 90.5% and 64.3% of participants, in the first and second experiments respectively, ate more snacks with sauce compared to without sauce. A Dutch study in 2001 found that the addition of meat and fish flavour enhancers to protein-rich meals increased food consumption by 7% in older adults living in a nursing home over a 16-week period(Reference Mathey, Siebelink and de Graaf48). Also, on average, the body weight of the elderly group who consumed the flavour-enhanced meals, significantly increased (+ 1.1 ± 1.3kg) compared to those who consumed the non-flavour-enhanced meals (−0.3 ± 1.6kg). However, when this study was replicated in 2007 by the same research group, under similar conditions, the effect of flavour enhancement was not seen in terms of food intake nor body weight, although it should be noted that the specific meat flavours used were not the same, the group sizes were smaller, and there were four parallel groups rather than two (as both taste and aroma were investigated in the later study)(Reference Essed, Van Staveren and Kok49). This suggests that flavour enhancement does not always have a positive influence on food intake in this age group. One aspect that should be noted it that most studies test a specific flavour type at a fixed concentration and yet as decline in sensory acuity is not uniform across individuals, this might partly explain conflicting results.

A single-blinded preference and consumption study carried out in elderly care wards in a UK hospital, investigated whether taste enhancement using ingredients naturally high in umami compounds, increased food consumption and food preferences in older patients(Reference Dermiki, Mounayar and Suwonsichon34). Patients tasted two cottage pies and gravy (control and taste- enhanced) and expressed their preference. At lunch, control and enhanced meals were served simultaneously. They were asked to consume ad libitum, and intake was measured. Taste enhanced cottage pie was significantly preferred. Although the taste-enhanced meal showed higher mean intake (137 g v. 119 g), energy (103 kcal v. 82 kcal), and protein (4.6 g v. 3.4 g) than the control, these differences were not statistically significant. It is worth noting that the sample size for this study was very small (n = 31) which might have contributed to the non-significant result for intake. In addition, patients were presented with two full plates of food which may have been overwhelming for some patients and impacted their food intake(Reference Dermiki, Mounayar and Suwonsichon34).

In another observational study, older adults better enjoyed meals when they were free to help themselves to wider variety of condiments, such as butter, vinaigrette, mayonnaise and tomato sauce in addition to the usual salt, pepper and mustard, whenever they wished, to accompany their meals(Reference Divert, Droz and Fuchs36). This caused an increase in the quantities of meat or vegetables consumed(Reference Divert, Droz and Fuchs36). Similarly, in another study, when older adults were offered a choice of seasoning and sauce, there were higher amounts of energy and protein were consumed in the meals with seasoning and meals with sauce compared to meals served without(Reference Best and Appleton38). Although these studies have investigated flavour enhancement on regular foods and diets, this may be a useful strategy in texture-modified foods or diets for older people. This is especially relevant considering that a recent study confirmed that flavour intensity is reduced in pureed food. The authors compared non-pureed and pureed food model, finding that the release of both volatile aroma compounds and tastants was reduced through pureeing, and that the resulting perceived flavour intensity was lower(Reference Horie, Kamei and Nishibe33). This suggests that, in addition to appearance differences, the reduced flavour of pureed meals might make it difficult for people to identify the actual flavour of the food and in turn may affect their liking towards it. Notably, in a recent randomised, three-way, crossover study, forty-one healthy older people aged 65 years and above, consumed a standard breakfast, followed by one of three ad-libitum pureed lunches (high protein (HP), high-protein-with-aroma (HP-Aro) or low-protein (LP)(Reference Ibitoye, Methven and Clegg50). Participants’ intake of ad-libitum pureed lunch, which consisted of pureed chicken, potatoes and carrots, was higher when they consumed the HP-Aro pureed meal compared to the HP and LP pureed meals. In addition to this, combining flavour enhancement with protein fortification significantly improved the palatability of pureed meals compared to protein fortification alone(Reference Ibitoye, Methven and Clegg50). These insights underscore the potential of multisensory approaches to optimise nutrition in ageing populations.

Offering foods that can aid consumption

Oral processing behaviours (OPBs) are physiological actions that influence how food is transformed in the mouth from its initial food structure into a bolus for digestion and include eating rate, oral exposure, chewing efficiency amongst others. These behaviours are modifiable factors associated with energy intake, appetite, and body weight(Reference Andrade, Kresge and Teixeira51,Reference Robinson, Almiron-Roig and Rutters52) . In younger adults, faster eating leads to greater energy intake and reduced satiety, while slower eating with thorough chewing enhances oral exposure, reduces intake, and promotes satiety(Reference Miquel-Kergoat, Azais-Braesco and Burton-Freeman53). Thus, slower eating is often recommended to manage weight(Reference Hawton, Ferriday and Rogers54,Reference Sorensen, Martinez and Jorgensen55) . However, these effects may be less beneficial – or even counterproductive – for older adults, particularly those experiencing reduced appetite or undernutrition.

Ageing is associated with declines in oro-sensory function, muscle strength, and dentition, which impair chewing efficiency and prolong oral processing(Reference Watanabe56–Reference Fontijn-Tekamp, Slagter and Van Der Bilt60). Older adults require more chewing cycles and time to swallow, leading to slower eating rates and potentially reduced within-meal energy intake and appetite(Reference Ketel, Aguayo-Mendoza and de Wijk61). While increased chewing has been shown to enhance satiety(Reference Zhu, Hsu and Hollis62), it did not increase food intake in ad libitum settings. Further research is needed to explore how eating rate and OPBs affect appetite and intake in older populations. Zannidi et al(Reference Zannidi, Methven and Woodside63,Reference Zannidi, Methven and Woodside64) explored the individual variations in OPBs and their association with energy intake and appetite in 88 healthy older adults (44 males, mean age 73.7 SD 5.3 years). From the postprandial self-reported appetite ratings, ‘prospective intake’ was rated higher in faster compared to slower eaters, indicating greater perceived appetite. Additionally faster eating rate at an ad libitum meal was independently associated with greater energy intake when accounting for age, sex, BMI, lunch liking and pre-lunch appetite ratings. This study highlights that developing foods that have the potential to increase eating rate may be a beneficial strategy increasing food intake in older adults’ subgroups that are in need of greater nutritional intake.

Dysphagia or chewing dysfunction is more common in older adults(Reference Woo, Tong and Yu65) and can impact oral intake. Ensuring the provision of suitable foods for older adults is therefore essential to enhance food consumption, as well as ensuring safety when meeting their nutrition requirements.

Structured interviews with older adults with chewing difficulties, often due to tooth loss or the use of removable dentures, explored various food preparation strategies which helped them increase intake of foods that they are familiar with(Reference Kossioni and Bellou66). These included slow-cooked meals, mincing meat, and boiling chicken to soften the texture. Participants also selected fruits with soft textures such as oranges, tangerines, grapes, and melons, enabling them to maintain dietary familiarity(Reference Kossioni and Bellou66).

Older adults with dysphagia may be offered a texture-modified diet (TMD) like pureed or mince and moist diet, depending on the severity of the condition. This is to reduce the risk of choking and aspiration, where food goes down the trachea into the lungs rather than the stomach, which can have severe health consequences(67). Yet it is thought that older adults typically consume inadequate amounts of texture-modified foods(Reference Wright, Cotter and Hickson68–Reference Nowson, Sherwin and McPhee70) with pooled data from a systematic review demonstrating that energy intakes are higher in regular diets compared to TMDs(Reference Wu, Miles and Braakhuis71). However, one possible way to encourage increased intake of texture-modified foods is by refining their appearance. It is suggested that using food moulds, 3D printing, and piping bags may improve liking and the appetite of older adults(Reference Liu, Yin and Wang72). Though appearance is an essential aspect of pureed food, the taste and smell may attribute the same importance(Reference Rusu, Badiu and Popescu30). This should be considered in cases where it is not possible to change the appearance of foods, such as for liquidised foods, where flavour should be prioritised to enhance food intake.

Finger foods, which are foods presented in a form that is easily picked up with the hands and transferred to the mouth without the need for cutlery, can be a useful intervention to increase food intake(Reference Forsberg, Nyberg and Olsson73,Reference Volkert, Beck and Cederholm74) and ideal for older adults who require longer to eat or have difficulty handling cutlery. Pouyet et al(Reference Pouyet, Giboreau and Cuvelier75) used softer foods and pureed forms of finger food to support older people with dysphagia or difficulties chewing and showed that pureed finger foods were generally well liked among older people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Conclusion

Malnutrition among older people is a critical clinical, public health, and economic concern, impacting health outcomes, healthcare costs, and quality of life. Addressing this issue requires effective dietary strategies, including energy- and protein-fortified foods, visually appealing meals, enhanced flavours of foods, and providing variety of foods to aid consumption are options to support adequate intake. Prioritising these strategies will help combat malnutrition and enhance the wellbeing of ageing populations.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the opportunity to present this review at the Nutrition Society Scottish meeting. We would also like to thank all the participants who took time out of their lives to participate in our research.

Author contributions

TI: writing original draft; review & editing. LM: review & editing. MC: writing original draft; review & editing.

Financial support

TI was supported by a PhD studentship funded by Apetito and the University of Reading.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.