The purpose of our study is to predict the result for the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) in the upcoming federal German parliamentary election on February 23, 2025, using data available in late December 2024. We proceed in three steps. First, we create a regression model using state- and national-level data from 1972 to 2021 to explain the results of the CSU in Bavaria and the CDU in all other states for the German Bundestag elections. Then, we use the coefficients from the estimated models and enter the most up-to-date data to predict state-level Bundestag results for each of the 16 German states. Finally, we use the distribution of voters across the states from the previous 2021 Bundestag election to estimate the weight of each state to reflect its influence on the final overall federal election result. Our model forecasts that the CDU/CSU will garner between 31.5% and 34.6% of the vote share in the February 2025 Bundestag election.

Our model forecasts that the CDU/CSU will garner between 31.5% and 34.6% of the vote share in the February 2025 Bundestag election.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES: THE UNDERLYING LOGIC OF OUR STATE-LEVEL FORECAST

We seek to create a parsimonious and accurate model for predicting the CDU/CSU election result using easily accessible data and independent of the fluctuations inherent in vote intention polls. Our approach is informed by the theoretical insights and empirical findings from the German voting behavior and election forecasting literature (Stegmaier Reference Stegmaier2022). We identified four salient factors that influence election outcomes in Germany. Three of these variables have a structural character capturing the economic, social, and political situation in the states, and the fourth variable allows us to take into consideration the current context. The three structural variables are the nominal GDP growth rate in the year preceding the federal election, the percentage of religiously nonaffiliated or adherents of denominations other than the two traditionally dominant religions in Germany (i.e. not Catholics and not Lutherans), and the CDU/CSU’s most recent previous state legislative election result. To measure the current political context in the country, we take the difference between preferences for a CDU/CSU chancellor candidate and those for the SPD contestant.

Our analysis builds on two earlier studies—the purely structural Länder-based model by Kayser and Leininger (Reference Kayser and Leininger2017) and the chancellor model by Norpoth and Gschwend (Reference Norpoth, Gschwend and Wüst2003) and Gschwend and Norpoth (Reference Gschwend and Norpoth2017). We combine selected aspects of these two approaches and test the viability of our specification focusing exclusively on the Christian Democrats.

Kayser and Leininger (Reference Kayser and Leininger2017) demonstrate the potential of incorporating state (Länder) legislative election results into forecasting models. Our model incorporates these state elections, but we further refine the state-level prediction with additional state-level measures. First, instead of using the national GDP growth rates, we include state-specific GDP growth rates. Second, we add a social-structure component, a measure of religious affiliation, that is especially relevant for the Christian Democrats. We operationalize this as the percentage of religious “others,” which is those who do not belong to the two traditional German mainstream denominations—that is, are not members of either the Lutheran or Catholic church. Thus, we acknowledge the relevance of political confessionalism in German politics (Burnham Reference Burnham1972) and give it new meaning in the time of “religion’s sudden decline” (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2021).

The addition of the national-level CDU/CSU chancellor candidate’s popularity in our model is inspired by the work of Norpoth and Gschwend (Reference Norpoth, Gschwend and Wüst2003), even though our operationalization differs from their approach as described below.

THE DEPENDENT VARIABLE: WHY THE CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATS?

Our model predicts the result of the German Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU), an alliance of the Bavarian Christian Social Union (CSU) and the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) that is present in all states except for Bavaria. We see several arguments in favor of this strategy. First, for much of the time since the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949, the CDU/CSU has been the strongest party at the federal level. The office of the chancellor has been held by the Christian Democrats for 52 of the past 75 years. In the 1950s and 1960s, the CDU/CSU amassed a large group of loyal voters and held a dominant position in German politics from 1949 to 1969. After the 1969 election, the SPD led the coalition government, and the following 1972 election marks the first in which a non-CDU/CSU government ran as the incumbent. We use 1972 as the starting point for our data series because it represents the beginning of a more balanced period in German politics, as voter preferences no longer favored the Christian Democrats as overwhelmingly as before. The loyalty of CDU/CSU supporters, despite the party’s increasing age and some resulting voter attrition, is still a strong advantage for Christian Democrats, making them less vulnerable to dealignment processes than other parties (Rosar and Mesch Reference Rosar, Masch, Korte, Schiffers, von Schuckmann and Plümer2022, 9). Thus, relative to their main rival, the Social Democratic SPD, the CDU/CSU remains the most stable large party in the German system.

Second, focusing on the CDU/CSU instead of the ruling coalition corresponds better with the changing reality of German politics. It marks a departure from the approach used in the classical chancellor model by Norpoth and Gschwend (Reference Norpoth, Gschwend and Wüst2003), that attempted to predict the collective result of the ruling coalition. Evaluating the result of the governing parties seems, on the surface, to correspond better with the logic of the reward–punishment mechanism for the government’s past economic performance (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier Reference Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier2000). This approach, however, is less practical in the 2024 political context considering the breakdown of the “traffic light” coalition of the Social Democrats, Greens, and the FDP that prompted the early Bundestag elections.

Third, in Germany, the reward–punishment mechanism does not apply equally to all parties comprising the governing coalition. As demonstrated by Debus, Stegmaier, and Tosun (Reference Debus, Stegmaier and Tosun2014), economic evaluations have the strongest influence on the party of the chancellor and little influence on the junior coalition partners. Thus, for predictive purposes the economy should have the greatest predictive power, not for the entire coalition but for the chancellor’s party.

Additionally, the transformation of the German party system and increasing political instability during the time of the current SPD Chancellor Olaf Scholz poses a challenge for models using historical data. Against this background, the CDU/CSU has remained relatively stable and secured solid results in several state legislative elections. As the SPD seems to have continued its decline even after the 2021 election, focusing on the other traditional chancellor party is a plausible strategy. It can be considered minimalistic, but, simultaneously, our model’s focus on the CDU/CSU increases the chance of an accurate forecast in a quite uncertain context.

In summary, we know more about Christian-Democratic support than about other parties in the German electorate. Thus, predicting support for the CDU/CSU allows for a theoretically grounded prediction model with the possibility of greater accuracy.

DATA OPERATIONALIZATION

While collecting data, our main concern was the consistency of measures over the entire period. From this point of view, the measurement of the state-level federal election results is straight forward, as they are accessible from the German Federal Election Office.

Obtaining data for the state-level GDP growth in the year preceding the election year was more challenging. We were able to retrieve it in a format guaranteeing consistency of measurement only for the period starting in 1970. We used the raw annual GDP data in current prices and computed its yearly percentage of change. The consequence of this approach is that our GDP growth indicator is higher than the real, inflation-adjusted GDP growth rate. However, our approach provides a consistent measure across the entire period.

Measuring the influence of social structure using religion statistics that are consistent across all 16 states is even more challenging than collecting economic data. In our model, we rely on the official Federal Statistical Office religious denominations census data. We were able to retrieve this information for 1970, 1987, 2003, and 2011, and we applied it to adjacent election years. Still, even this imperfect approach can reflect both the between-state differences at given points and the dynamic state-level changes in religious composition over time.

The data for the CDU/CSU state-legislative election results can be easily obtained, but they also have some limitations. The fact that “state-level elections in Germany are scattered across the calendar” (Kayser and Leininger Reference Kayser and Leininger2017, 689) makes them an important, yet imperfect, signal of voter’s sentiments. And although in most states across election cycles, a state legislative election was held between the Bundestag elections, this has not always the case. It can happen that a state legislative election was not held in the period between Bundestag elections, which then limits the predictive validity of the previous state legislative election measure. This issue with election timing can occur because most German states extended the state legislative term from four to five years in the 1990s, whereas the regular Bundestag legislative period is four years. Additionally, when early Bundestag elections are called—for example, in 1972, 1983, and 2005—even more states are affected by this issue. We also must keep this limitation in mind for our forecast because the upcoming 2025 Bundestag election is an early election.Footnote 1 Despite this limitation, we believe that state legislative election data remains an indispensable component of a forecast that is directed at predicting state-level vote shares.

Measuring the fourth variable in our model, the popularity of the CDU/CSU’s top candidate is probably most challenging. We decided to rely on the “Kanzlerfrage,” a question about the preferred chancellor, because it is available in the German Election Study or Politbarometer for all the elections that are covered in our model—that is, for the period between 1972 and 2021. However, the question was not always asked in the same manner. Although most data sets contain the direct CDU/CSU leader to SPD leader comparison, in some years only a multicandidate question was asked. In these cases, we focused only on the actual top contestants. In the 2021 study (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen Reference Forschungsgruppe Wahlen2022), both versions of the question were asked, and we opted to rely on the multicandidate comparison due to its higher N. In the December 1990 election (Kaase et al. Reference Kaase, Hans-Dieter, Manfred, Pappi Franz and Semetko Holli2013), the first one after the October 1990 reunification of Germany, we used data from the November 1990 wave. We did not use earlier data due to the unusual nature of this campaign, which was transformed dramatically by the fall of the Berlin Wall, reunification negotiations, and the reunification itself, which occurred only two months before the election.

To obtain comparable data across all data points, we follow the logic suggested by Norpoth and Gschwend (Reference Norpoth, Gschwend and Wüst2003, 112) and compute the differential between the two top candidates by excluding “none of the two” responses in the two-candidate comparisons. For the multicandidate format, we exclude undecided respondents and also those who expressed a preference for candidates other than the CDU/CSU and the SPD chancellor candidate. This transformation inflates the support for the two leaders that are taken into consideration, but as observed by Norpoth and Gschwend (Reference Norpoth, Gschwend and Wüst2003, 112), the effect is the same across data points and therefore should not bias the results.

MODEL ESTIMATION

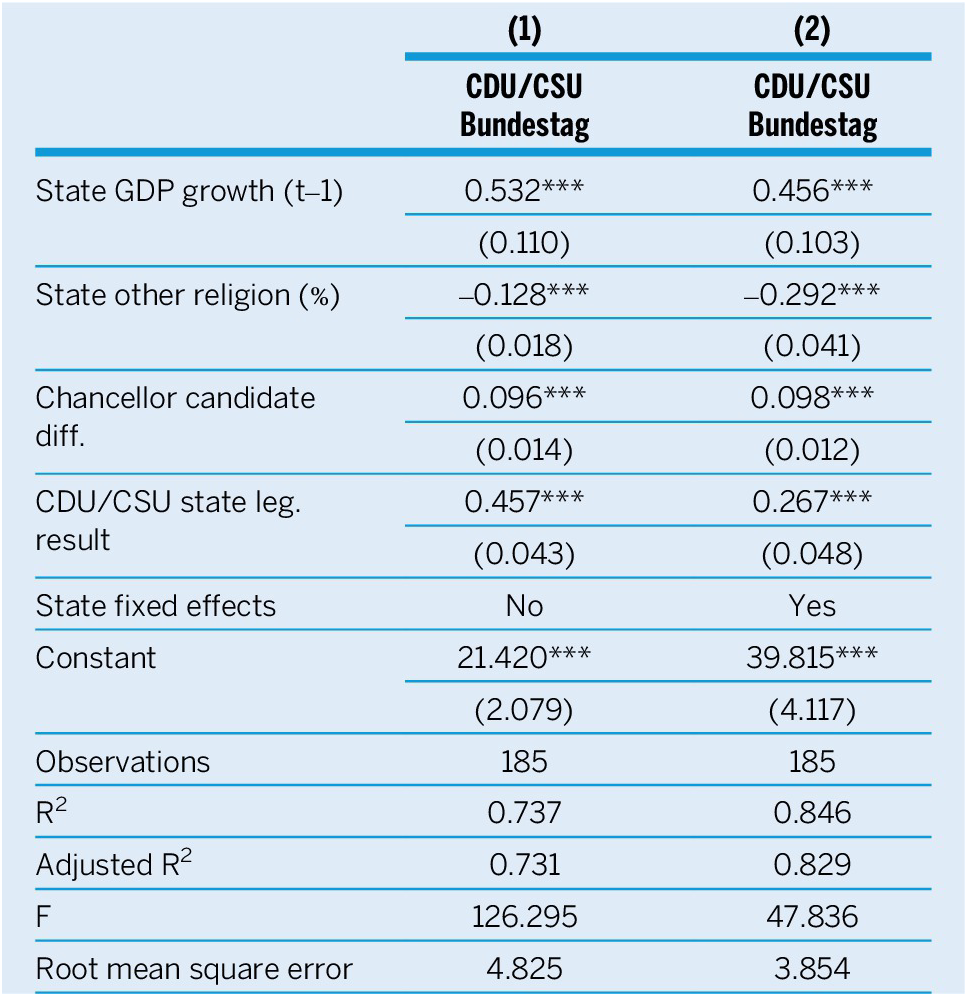

Using four independent variables—state GDP growth, the state’s percent of non-Catholics and non-Lutherans, previous state legislative election results, and the CDU/CSU leader differential—we created two models that offer the best compromise between parsimony and goodness of fit (table 1). They differ merely with respect to the use of state-level fixed effects. Model 1 does not include state-level fixed effects and model 2 includes them.

Table 1 CDU/CSU State-Level Vote Share Regression Models (1972–2021)

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. Brandenburg is used as the reference category for state fixed effects.

* p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Adding fixed effects increases explanatory power. However, it comes at the cost of assuming that the state-level context in this year’s election works similarly to the past. If we use fixed effects, we obtain a series of estimates strongly influenced by historical realities that may no longer exist in a given state. This is challenging in the context of the recent transformation of the German party system paired with the decomposition of traditional political milieus. Therefore, we report both results. The more parsimonious model 1, which expends fewer degrees of freedom with only four variables, has an adjusted R2 of 73%. This compares with model 2, which has an adjusted R2 of 83%.

The regression coefficients in both models indicate that the independent variables are statistically significant and have similar magnitudes. We see that a 1-percentage-point change in nominal state-level GDP growth change increases the vote share of the CDU/CSU by roughly half a percentage point. The share of non-Catholics and non-Lutherans has, in contrast, a detrimental effect on the election results for the Christian Democrats. A 1-percentage-point increase in the share of religious “others” decreases the vote share of the CDU/CSU by between 0.1 (model 1) and 0.3 (model 2) percentage points.

The popularity of the Christian Democratic chancellor candidate is an important positive factor. A 1-percentage-point improvement of the top Christian-Democrat, increases the vote share of their party by roughly 0.1 percentage points. Finally, the improvement of CDU or the CSU results in the most recent state legislative elections by 1 percentage point and boosts the state-level Bundestag election result of the party by between 0.46 and 0.27 percentage points. Here the difference in the magnitude of the coefficients between both models is more strongly pronounced. It decreases substantively after the introduction of fixed effects, as state-level fixed effects are already accounted for in this model.

The effect of state-level GDP growth on the CDU/CSU vote share in these two models is independent of whether Germany is ruled by a government with a Christian Democratic chancellor.Footnote 2 This is probably the most surprising finding of our model. We must, however, bear in mind that we use the state-level GDP growth rates, not the national-level values used, for example, by Kayser and Leininger (Reference Kayser and Leininger2017). The relationship of this indicator with the composition of the national-level government is less clear. We hypothesize that the effect we observe may be related to the fact that economic growth is one of the cornerstones of the CDU/CSU’s identity, which is reinforced by its image of being a party that laid the foundations for the postwar Wirtschaftswunder era. It is also possible that the use of nominal instead of inflation-adjusted numbers plays a role here.

THE 2025 ELECTION PREDICTION

The coefficients estimated on data from 1972 to 2021 are used to predict the state-level results for the 2025 Bundestag election.Footnote 3 One last challenge that we face concerns the operationalization of the CDU/CSU top candidate’s popularity differential. The problem is the comparability of the currently available data on the “chancellor question” with historical data when there were usually two strong contenders for the office of the chancellor. We solved this problem by creating three different variations of the leader popularity differential using the results of the December 2024 edition of the Politbarometer. The first approach is based on the direct comparison between the incumbent SPD chancellor, Olaf Scholz and the CDU/CSU top candidate, Friedrich Merz. The second one uses the cleaned results for these two candidates from a multiple-candidate question. Then, the third approach measures the difference in popularity between Merz and the second most popular candidate in the multicandidate question, Robert Habeck, representing the Greens. We apply these three different measures in each of the two models. This results in six different predictions for the CDU/CSU’s 2025 Bundestag election vote share in each of the 16 states.

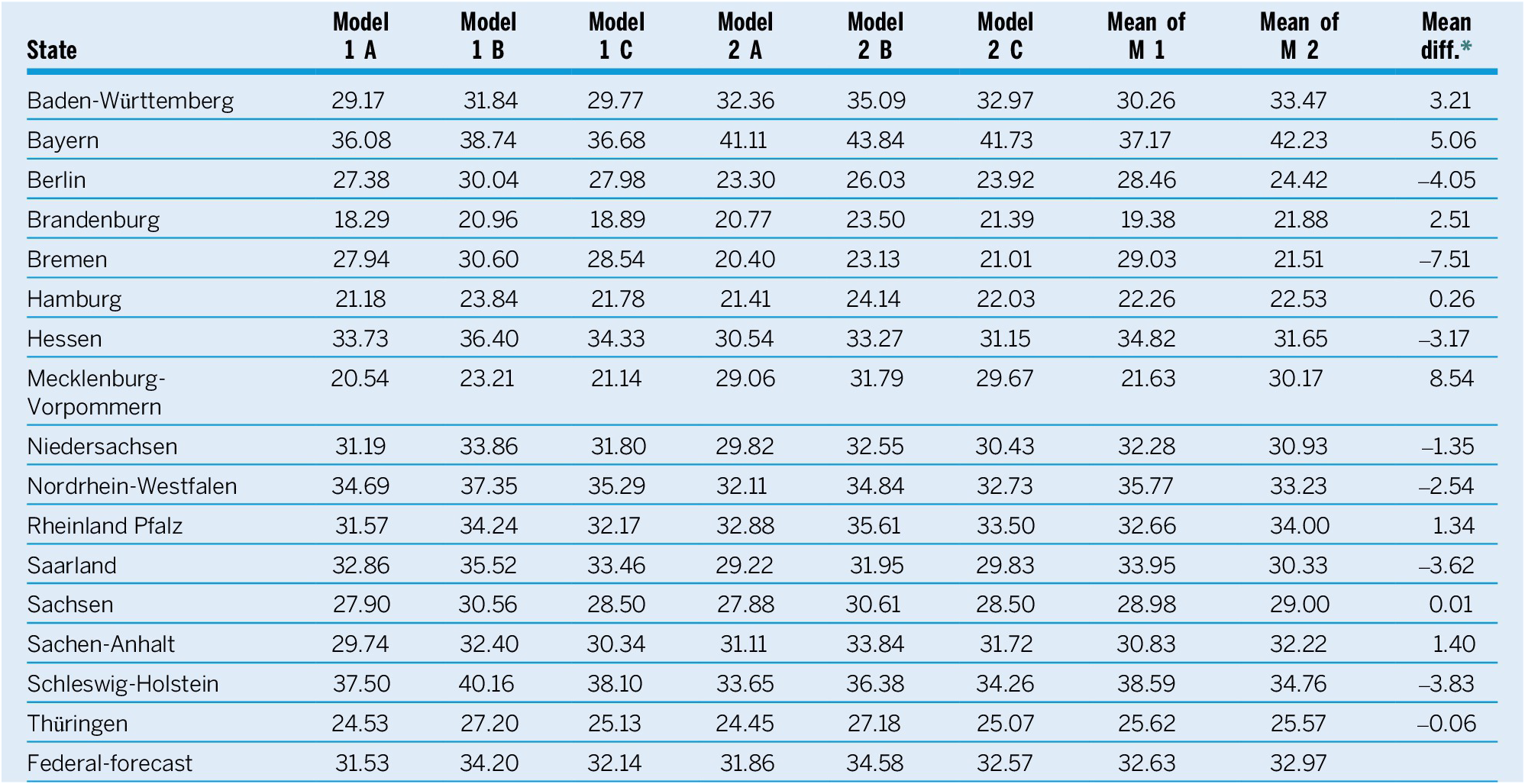

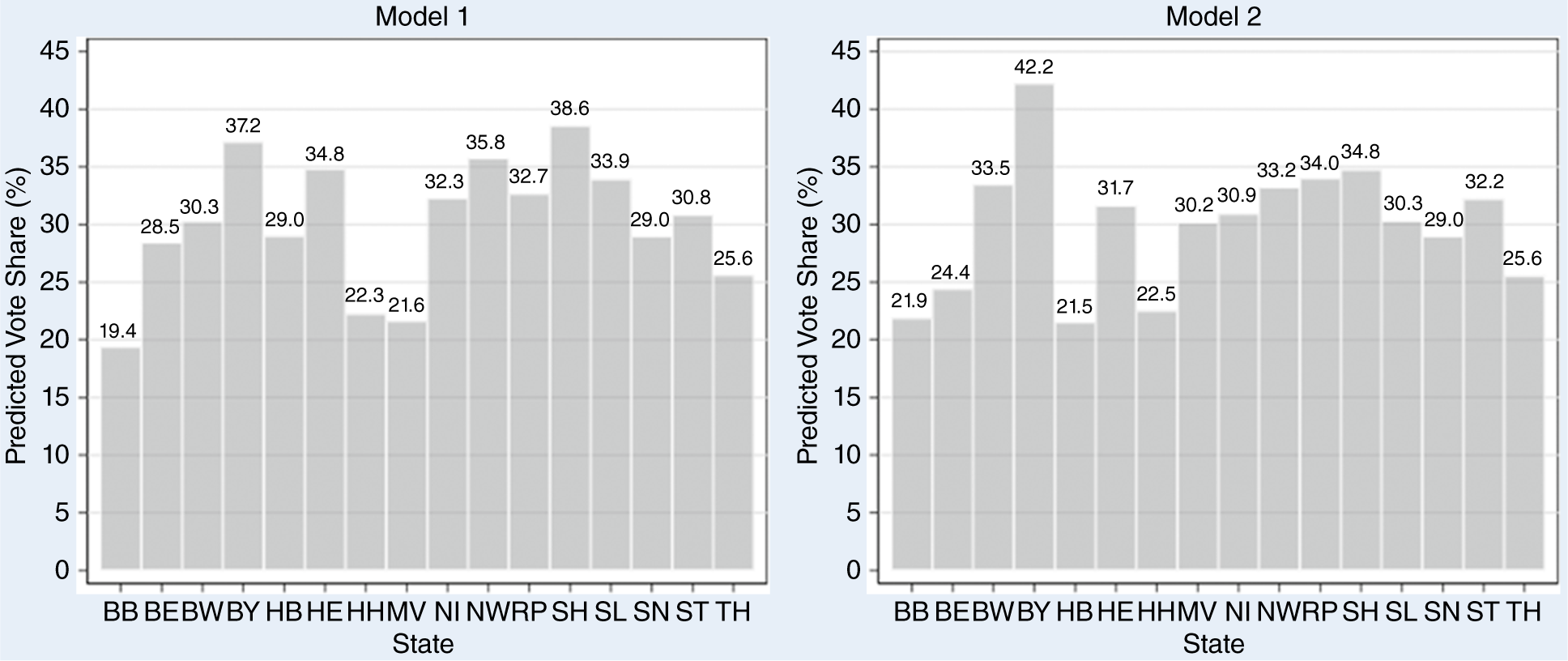

The predicted CDU/CSU vote shares for all six variations of two models and mean values for both models are displayed in Table 2. Additionally, Figure 1 displays the mean values for Models 1 and 2 to demonstrate that the state-level results differ in some cases. The largest difference between the mean values of both models is observed for Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, where adding the historical context in the form of state-fixed effects boosts the CDU/CSU result by over 8.54 percentage points. This may be attributed to the fact that fixed effects reflect the influence of former Chancellor Angela Merkel in the past winning her seat in this state, which is currently no longer the case. The result of the Bavarian CSU is similarly corrected in the positive direction if we add historical context. Considering that the CSU has lost votes in state legislative elections to other conservative parties, especially the Free Voters (FW), it is less obvious that we see a bias here.

Table 2 Predicted state-level CDU/CSU vote share (%) for the 2025 Bundestag election and the federal-level forecast estimated using the state-level predictions. Three variants of model 1 (no fixed effects) compared with three variants of model 2 (with state-level fixed effects)

* Difference between the mean predictions of model 2 and model 1, which reflects the change in the forecast after we add state-level fixed effects.

Figure 1 Predicted State-Level CDU/CSU Results for the 2025 Bundestag Election by State

Note: The means of three variants of Model 1 (no fixed effects) compared with the means of three variants of Model 2 (with state-level fixed effects).

Compared with the effects found in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Bayern, the opposite can be observed for Bremen and to a lesser extent also for Berlin, Schleswig-Holstein, and Hessen where the CDU/CSU has performed better in recent state elections than could be expected based on its historical performance. Adding fixed effects decreases the predicted result of the Christian Democrats. Still, these conflicting effects between the two models cancel out when the predicted state-level result is weighted by the share of voters from a given state in the overall German electorate. As a result, the mean values of the predicted federal-level results for models 1 and 2 are very close to each other. What matters more, is which of the three chancellor-candidate-differential scenarios we apply.

Using the distribution of valid votes across the states in the 2021 Bundestag election, we estimate the expected CDU/CSU federal-level vote share for each of the six scenarios (table 2, Federal-forecast row). The main factor differentiating these predictions is how the popularity of the CDU/CSU chancellor candidate Friedrich Merz is measured. This matters more than including or excluding state-level fixed effects. The Christian Democrats are expected to obtain between 31.53% and 31.85% of votes if we assume a 1-percentage-point difference between the supporters of Merz and Scholz (models 1a and 2a). If, on the other hand, we use the Merz-Scholz differential from the multicandidate evaluation (excluding other candidates), the result for the CDU/CSU increases to 34.2%–34.58% (Models 1b and 2b). In the third scenario, when we use the same multicandidate evaluation but measure the difference between Merz and the second-placed Habeck, our forecast suggests roughly 32.14% to 32.47% (models 1c and 2c).

Across these six prediction scenarios for the February 2025 Bundestag elections, the lowest CDU/CSU vote share forecast is 31.5% and the highest is 34.6%. This result would not be enough for the CDU/CSU to govern alone, so they would need to join forces with another party or parties to form a coalition government.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096525000125.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study (Marcinkiewicz and Stegmaier Reference Marcinkiewicz and Stegmaier2025) are available at the Harvard Dataverse at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/OIRM5N

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.