Introduction

Research suggests that being a musician has a marked impact on identities, attitudes and behaviours (Cogo-Moreira & Lamont, Reference COGO-MOREIRA and LAMONT2018; Dwyer, Reference DWYER2016; Macdonald et al., Reference MACDONALD, HARGREAVES and MIELL2002; Welch, Reference WELCH, HARGREAVES, MIELL and MACDONALD2012). The ways in which these identities, habitual behaviours and value judgements influence a music teacher’s pedagogic practice have also been well documented (e.g., Burnard, Reference BURNARD2012; Dwyer, Reference DWYER2015; Dwyer, Reference DWYER2016; Garnett, Reference GARNETT2014; John et al., Reference JOHN, BEAUCHAMP, DAVIES and BREEZE2024; Odena, Reference ODENA2012; Odena & Welch, Reference ODENA and WELCH2009; Randles & Ballantyne, Reference RANDLES and BALLANTYNE2016; Söderman et al., 2015; Welch, Reference WELCH, HARGREAVES, MIELL and MACDONALD2012; Wright, Reference WRIGHT, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015). These perspectives can be seen in action in Wright’s 2008 research set in a secondary music classroom in Wales. It analyses the power tensions that permeate the interactions between pupils and teacher. Wright postulates that this may have come from the behaviours, values and attitudes embedded in the teacher’s classical music background, in which pervasive hierarchies exist and where the balance of power typically rests firmly and unequivocally with the teacher, composer or conductor (Dwyer, Reference DWYER2016).

At the time of Wright’s research, Wales shared the same broad curriculum aims, structures and approaches as other nations within the United Kingdom (UK). However, Wales is witnessing a period of significant educational reform, with a ‘transformative student-centred curriculum being developed’ (Power et al., Reference POWER, NEWTON and TAYLOR2020, p. 317). Aspirations include affording teachers greater agency, freedom and creativity (Hughes & Lewis, Reference HUGHES and LEWIS2020, p. 295), with less prescribed content and more freedom for teachers to educate their pupils as they see fit, within the confines of a much looser curricular framework (Evans, Reference EVANS2024). In addition, learner voice is valued and considered when making curricular and pedagogic decisions, including having a stake in what they want to learn and how they will learn it (Estyn, 2019). Early critical insights into the implementation of Curriculum for Wales are evolving (e.g., Evans, Reference EVANS2023; Power et al., Reference POWER, NEWTON and TAYLOR2020), but, as it is not fully implemented until 2027, it is difficult to provide a meaningful critique of its impact until then, when it will provide very fertile ground for future research.

Eighteen years on from Wright’s work, it is timely to explore if a changing educational landscape in Wales has cultivated any pedagogic shifts in which the ‘habitus’ of the secondary music teacher has indeed been ‘kicked’ (Wright, Reference WRIGHT2008). The new Welsh Curriculum, introduced incrementally from 2022, ‘sets a bold direction for teaching and learning in Wales’ (Sinnema et al., Reference SINNEMA, NIEVEEN and PRIESTLEY2020, p. 197), where ‘there is the potential to create a culture of learning and development where teaching professionals can work more creatively and be more responsive to individual learner needs and circumstances’ (Taylor, Reference TAYLOR2017). However, Newton (Reference NEWTONn.d.) rightly argues that this will require a substantial change of mindset for teachers. Encouragingly, Breeze et al. (Reference BREEZE, BEAUCHAMP, BOLTON and MCINCH2023) suggest that Welsh secondary music teachers’ beliefs seem to have ‘moved beyond those embodied in their university education, [and] this would offer a counterpoint to the argument that teachers find it difficult to make such a transition when joining the profession’ (Breeze et al., Reference BREEZE, BEAUCHAMP, BOLTON and MCINCH2023, p. 54). Our research aims to explore this further by eliciting the views of three student teachers.

The three participants were student secondary music teachers studying for their Post Graduate Certificate of Education (PGCE) at the same university in Wales. All were formally musically trained and self-identified as ‘classical’ musicians, meaning they had learnt through practices linked to the Western European classical tradition, making them very typical of the secondary music teaching workforce in other Westernised countries (Burnard, Reference BURNARD2012; Dwyer, Reference DWYER2016). It should be recognised that debates on the terminology surrounding classical music as a purely ‘Western’ genre have moved on significantly. We acknowledge that classical music is now transnational and globalised, and the genre should no longer claim ‘exclusive ownership of a cultural space whilst denying the existence of ‘others’ who have been and continue to be central to it’ (Nooshin, Reference NOOSHIN2011, p. 294). Therefore, we will refer to the genre at the centre of this discussion as Western European classical music.

Literature review

Contextualising Curriculum for Wales and learner voice

The Curriculum for Wales came about as a result of Donaldson’s Reference DONALDSON2015 Successful Futures report commissioned by the Welsh Government into school-based curriculum and assessment in Wales. All 68 of Donaldson’s recommendations were accepted by the government and were incorporated within a new curriculum policy framework which set in motion the most significant and far-reaching reform of education in Wales since the introduction of the national curriculum in 1988 (Newton, Reference NEWTON2020). Taking a markedly different direction to curriculum reform in England at the time (Spruce, Reference SPRUCE2013), Donaldson advocated for a curriculum being ‘framed in terms of the key skills, capacities or competencies’ (Donaldson, Reference DONALDSON2015, p.5) to be developed in learners, and so the drive towards a purpose-driven curriculum was born. Subject disciplines in Curriculum for Wales were grouped into Areas of Learning and Experience (AoLE), with music in the Expressive Arts AoLE along with art & design, drama, dance, film and digital media. AoLEs were framed by Statements of What Matters that provided, in very generalised form, the core curriculum content that outlines ‘the experiences, knowledge and skills children should encounter throughout their schooling’ (Newton, Reference NEWTON2020, p. 216). In the Expressive Arts AoLE, these statements were framed through the overarching concepts of explore-respond-create (Welsh Government, 2020a), which intend to offer opportunities for learners to make ‘powerful connections’ (Donaldson, Reference DONALDSON2015, p. 68) in their learning across the subject disciplines housed within. Although the perform-compose-appraise model that, like England, had formed the basis of the music curriculum in Wales since 1988 was subsumed within the Curriculum for Wales explore-respond-create framework, it is worth noting that current Welsh curriculum policy documents still endorse performing vocally and on instruments, composing and improvising, and analytical and evaluative listening as the backbone of musical activity in Welsh classrooms and continue to recommend that standard musical concepts such as pitch, melody, rhythm, dynamics, texture, timbre, structure etc. are integral to curriculum design and delivery (Welsh Government, 2020a). It is intended that engagement in these under the broader framing of explore-respond-create offer disciplines within the Expressive Arts AoLE opportunities to discover and explore commonalities, differences and collaborative possibilities, whilst preserving the ‘cherished ideas’ (Fautley & Savage, Reference FAUTLEY and SAVAGE2011, p. 2) within the subject of music. Furthermore, the GCSE and GCE examination requirements of the compulsory examination board for schools in Wales continue to root their specifications within the performing, composing and appraising model. Indeed, given the progressive direction Curriculum for Wales has taken, these examinations remain surprisingly unchanged in terms of content.

A distinctive feature of curriculum development in Wales was its ‘bottom up’ approach in which a selection of teachers from primary, secondary and special schools were tasked by the Welsh Government to create the curriculum content (Kneen et al., Reference KNEEN, BREEZE, DAVIES-BARNES, JOHN and THAYER2020). Indeed, the principle of subsidiarity has been a fundamental philosophy of Curriculum for Wales and is employed as a key element in curriculum design and implementation. By subsidiarity, Donaldson advised ‘approaches [that] should focus less on central [legislative] direction and more on the need to develop local responsibility and decision making’ (Donaldson, Reference DONALDSON2015, p. 99), affording teachers agency to ‘more directly shape the curriculum in ways that meet the needs of their children and young people’ (Donaldson, Reference DONALDSON2015, pp. 110–111). However, if ‘subsidiarity means that power stays as close as possible to the action’ (Donaldson, Reference DONALDSON2015, p. 99), then both teachers and learners should have a stake, and it is in this broad sense that the concept of learner voice is employed within this article. Government guidance clearly encourages schools in Wales to draw on the voice of all learners in the curriculum design process (Welsh Government, 2020b), and secure evidence is emerging that teachers have welcomed the opportunities to include content directed by the learners (Thomas et al., Reference THOMAS, DUGGAN, MCALISTER-WILSON, ROBERTS, SINNEMA, COLE-JONES and GLOVER2023), with some tangible results evident (Estyn 2019; Estyn 2020). However, recent research (Chicken & Tyrie, Reference CHICKEN and TYRIE2023; MacBride, Reference MACBRIDE2021; Roberts et al., Reference ROBERTS, WILLIAMS and CROKE2023) questions the extent to which learner voice in Wales has been consistently and authentically elicited, pointing out the insufficiency and shallowness of formal learner consultation (MacBride, Reference MACBRIDE2021) and advocating the need to go further than ‘merely participation’ (Roberts, Williams & Croke, Reference ROBERTS, WILLIAMS and CROKE2023, p. 44). In criticising these methods of learner voice as offering only a ‘veneer of democratic legitimacy’ (Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015, p. 291), Spruce (Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015) and Bull (Reference BULL2024) call for a dialogical approach which requires a more genuine collaboration between teacher and learner, including a ‘willingness to enter into the world of other voices and to see and hear things – to see potential meanings – from the perspectives of those other voices’ (Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015, p. 299). Returning to the concept of subsidiarity in Curriculum for Wales but through a specifically music lens, Bull (Reference BULL2024) reminds us of the uniqueness of music and the need for learners to develop their own ‘musical voice; by this, I mean the ways in which musical learners might discover an expressive, creative voice through their music education’ (Bull, Reference BULL2024, p. 27) and, as a result, make their own musical and creative decisions. In doing so, they might also be able to create new musical meanings and understandings that are unique to them, as opposed to the ‘“one single true perspective” inherent in the concept of monological discourse’ that, according to Spruce (Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015, p. 299), has traditionally prevailed. As he concludes,

Thinking about music in these dialogical terms reveals a rich and fertile ground for the creation of a musical pedagogy that seeks to engage the voice of the learner…as reflective, thinking musicians and as equal participants in the construction of pedagogy and curriculum (Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015, p. 299).

Classical music, hierarchy and the teacher

Mrs Metronome, the teacher at the centre of Wright’s Reference WRIGHT2008 research, was a musician trained in the Western European classical tradition (Wright, Reference WRIGHT2008, p. 394), and data captured in research conducted by Breeze et al. (Reference BREEZE, BEAUCHAMP, BOLTON and MCINCH2023) identify that the typical secondary music teacher in Wales still follows an academic degree underpinned by this genre and identifies as a classical musician. This has clear implications. Dwyer (Reference DWYER2016, p. 13) argues that a music teacher’s affinity with their classical music background can result in ‘Western art music [being] positioned as a superior style in some [school] music programmes’, and this can be seen ‘not only through its prominent place in the [music] curriculum, but through the replication of its values and practices in the classroom’ (Dwyer, Reference DWYER2016, p. 13). Therefore, it seems pertinent to briefly explore these values and practices, as they might explain some of Mrs Metronome’s subsequent pedagogic choices and will also have a relevance in the discussion of our participants in this study.

Sagiv and Hall outline many of the ‘distinguished dispositions’ (Reference SAGIV, HALL, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015, p. 124) of a classical musician: the ideal of virtuosity and the pursuit of perfection are ultimate goals, with value placed on excellence of expression and technique, the ability to read and realise challenging notation and the capacity to fully honour the intentions of the composer (Benedek et al., Reference BENEDEK, BOROVNJAK, NEUBAUER and KRUSE-WEBER2014; Burnard, Reference BURNARD2012; Creech et al., Reference CREECH, PAPAGEORGI, DUFFY, MORTON, HADDON, POTTER, DE BEZENAC, WHYTON, HIMONIDES and WELCH2008; Green, Reference GREEN2002; Perkins Reference PERKINS, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015; Sagiv & Hall, Reference SAGIV, HALL, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015; Welch et al., Reference WELCH, PAPAGEORGI, HADDON, CREECH, MORTON, DE BEZENAC, DUFFY, POTTER, WHYTON and HIMONIDES2008; Welch, Reference WELCH, HARGREAVES, MIELL and MACDONALD2012). Yet, within this world, many authors expose the innate yet overt hierarchy that exists (Bull, Reference BULL2021; Bull, Reference BULL2024; Dwyer, Reference DWYER2016; Perkins, Reference PERKINS2013; Sagiv & Hall, Reference SAGIV, HALL, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015; Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015). Exemplifying Bull’s concept of institutional hierarchies (Reference BULL2021), Mrs Metronome affords a higher status in her school, which can result in social interactions that are somewhat authoritarian and one-directional (Bull, Reference BULL2024), potentially silencing the voices of the learners (Bull, Reference BULL2024; Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015) and reducing them to a position of compliance (Sagiv & Hall, Reference SAGIV, HALL, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015). Another genre convention associated with European classical music that can seep into music education is the ‘pedagogy of correction’ (Bull, Reference BULL2024, p. 46). Compliance is at the fore once again, this time in adherence to the written score and in honouring the composer’s intentions, but these convergent behaviours remove any opportunity for creative ‘messing around’ (Bull, Reference BULL2024, p. 46) and limit the capacity for learners to develop their musical voice. Another ubiquitous genre convention that limits learner autonomy is the hierarchical master-apprentice pedagogical approach (Abramo & Austin, Reference ABRAMO and AUSTIN2014; Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015; Almqvist & Werner, Reference ALMQVIST and WERNER2024; Bull, Reference BULL2024), which is exposed in data collected by Wright (Reference WRIGHT2008) from Mrs Metronome’s learners. When reflecting on activity in their music lessons, one learner states that they do ‘what the teacher wants to do, not what I want to do’ (Wright, Reference WRIGHT2008, p. 395). It is interesting to note that whilst current Welsh music teachers are mostly in favour of an amount of learner-led activity, they also see value in teacher instruction (Breeze et al., Reference BREEZE, BEAUCHAMP, BOLTON and MCINCH2023). There is a clear dichotomy – whilst these teachers strive to afford their learners more divergent experiences and practices, the need for the hierarchical control over the learning is apparent. Similar tensions were exposed in Wright’s Reference WRIGHT2008 findings. Despite a genuine attempt to uphold democratic values and take into account learner interests, ‘ultimate power over curriculum and pedagogy rested firmly with the teacher’ (Wright, Reference WRIGHT2008, p. 389), revealing her classical music affiliation and desire for control. Finally, Bull (Reference BULL2021, p. 5) suggests that people in positions of power may not recognise the power they are employing. Instead, ‘relations of power may only be apparent to those who are positioned as powerless within the institution or interaction’ (Bull, Reference BULL2021, p. 5). In Wright’s study (Reference WRIGHT2008), Mrs Metronome is confident that she is taking learner interests into account, but the views of a significant number of her learners are starkly different, demonstrating that ‘A uniform approach to classroom music, however well conceived and executed, rides roughshod over these sensitive relationships and may well serve to distance pupils from their music education’ (Wright, Reference WRIGHT2008, p. 398).

Hierarchy and the requirement to conform can also exist between a beginner teacher and a more experienced practitioner, as exemplified by Idzania (Reference IZADINIA2014). The mentor (the teacher tutor) to a music student teacher in her research speaks encouragingly of ‘bringing a new player into the team’ (Izadinia, Reference IZADINIA2014, p. 396), but where he is most definitely the senior player, clearly laying out the need for the student to be ‘fully integrated and there would be certain expectations of performance and things like that…’ (ibid). Although he is trying to welcome the new teacher and demonstrate an affiliation, there is an underlying sense of his desire to define the ground rules and the behaviours that will gain favour. According to Idzania (Reference IZADINIA2014, p. 387), the relationship between student teacher and mentor is considered the biggest influence on the student teacher’s professional development, and overall success heavily depends on the positive relationship between the two parties, but as Burnard, Hovander-Trulsson & Södermann (Reference BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015, p. xviii) caution, in any domain, there exists power, struggle and hierarchy, and this certainly seems to be the case here. In adopting the master-apprentice approach to mentoring the student teacher in Idzania’s research, the experienced teacher is implicitly asserting power, flexing hierarchical muscles and narrowing down any possibility the student teacher has to move away from the behaviours, values and attitudes that the mentor privileges to create new understandings of pedagogy.

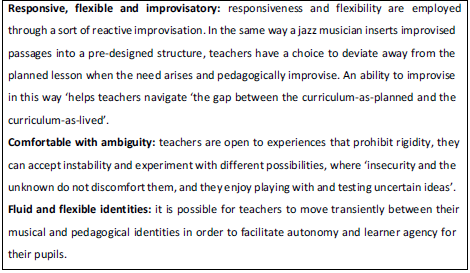

However, research by Abramo & Austin (Reference ABRAMO and AUSTIN2014) and Wright (Reference WRIGHT, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015) identify two music teachers who were able to reflexively question their classical music behaviours and the extent to which the pedagogies they influence were viable or appropriate for learners in their classroom settings. By loosening the hierarchy, affording agency and allowing the learners’ voices to be heard and listened to, both parties became co-participants in the direction of learning. A new pedagogic teacher identity began to emerge, and it is helpful to use Abramo & Reynolds’ (Reference ABRAMO and REYNOLDS2015, pp. 38–40) theoretical framework for pedagogic creativity (Figure 1) to identify some of the characteristics.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for pedagogic creativity (Abramo & Reynolds, Reference ABRAMO and REYNOLDS2015, pp. 38–40).

The new Welsh Curriculum ‘sets a bold direction for teaching and learning in Wales’ (Sinnema et al., Reference SINNEMA, NIEVEEN and PRIESTLEY2020, p. 197). Within this landscape, we explore the extent to which Abramo & Reynolds’ (Reference ABRAMO and REYNOLDS2015) capacities can be enacted. We also take into account the findings from Breeze et al. (Reference BREEZE, BEAUCHAMP, BOLTON and MCINCH2023) which suggest that Welsh music teachers’ beliefs about the subject have moved away from those they held when studying music at university, and this offers a potential opportunity for different ways of thinking as they transition into the profession. Our field research aims to build on this further as it elicits the views of the three pre-service teacher participants.

Methods

This study adopted a narrative inquiry approach (Seale, Reference SEALE2012) to understand three secondary school music student teachers’ subjective experience of their training year ‘by making their stories a central feature of research’ (Garvis & Prendergast, Reference GARVIS and PRENDERGAST2012, p. 111). Data were collected from the full student music teacher cohort, and of the five who associated themselves with the European classical music genre, the three featured in this paper participated for the full duration of the data collection and analysis period. For reference, in John et al. (Reference JOHN, BEAUCHAMP, DAVIES and BREEZE2024), we discuss the findings from the popular musician student teacher sample. The researchers’ role was a relational one, ‘attentive to the inter-subjective, to the relational embedded spaces in which lives are lived out’ (Clandinin, Reference CLANDININ, THOMPSON and CAMPBELL2010, p. 3). Data were collected over 10 months via a series of three semi-structured individual interviews at the start, mid-point and end of their PGCE programme, which enabled participants to ‘define their world in unique ways’ (Merriam, Reference MERRIAM2009, p. 90). Interview one focused on self-perceptions of their musical identities and the beliefs, behaviours and affiliations these had fostered in them. Interview two focused on their emerging practices and developing behaviours as music teachers. It stimulated discussion in which they could reflect, articulate, describe and compare their practices and habitual behaviours within and between the musical and pedagogic domains. Interview three built upon themes developed in interview two but also provided an opportunity to reflect holistically on how their lived experiences over their training year had shaped their beliefs and behaviours as both teachers and musicians.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted from the lead author’s institution and followed BERA guidelines (2024). Additionally, aware of the potential power dynamic between academic staff and students, interviews were informal and conversational in nature and took place away from the university. In the spirit of narrative inquiry, the interviewer and participant were both active and collaborative participants to ‘jointly construct narrative and meaning’ (Riessman, Reference RIESSMAN2008, p. 23).

Participants

The views of three secondary student teachers who self-identified as classical musicians are reported here. The following vignettes are drawn from their self-perceptions in the series of interviews:

Carys: an accomplished classical musician who plays three instruments to a high standard and has extensive experience as a chorister;

Berwyn: a classically trained trumpet player, who enjoys working on technique;

Idris: a classical musicologist and euphonium player who loves analysing Bach chorales.

Data analysis

Each interview was transcribed, and draft individual narratives were summarised. These ‘interim texts’ (Clandinin & Connelly, Reference CLANDININ and CONNELLY2000, p. 132) were scrutinised to extract information that most closely described the actual experience or events in the participants’ told stories. The composition of each narrative aimed to empathetically ‘represent, explore and/or understand the subjective world of the participants and the social world they feel themselves living in’ (Josselson, Reference JOSSELSON2004, p. 5).

We asked for internal verification from each participant, and from the classical musician sample, Carys, Berwyn and Idris replied to this request and vouched for their narrative’s accuracy. The fundamental and overarching meanings contained in the narratives were identified by ‘highlighting on the transcript key events, characters and turning point moments’ (Sparkes & Smith, Reference SPARKES and SMITH2014, p. 132), and patterns, narrative threads, tensions and themes were generated. Once categorised via the initial inductive process, the narratives underwent a deductive meta-analysis process, in which they were grouped, thematically analysed and coded, whilst still attempting to keep the stories intact. The narrative threads below are representations of the themes that commonly emerged via the participant-researcher conversations and were identified from this two-stage analysis. In presenting the findings of these themes in the form of narrative threads, we draw from Ryan (Reference RYAN2019, p. 3), who explains that ‘Identity can be seen as a patchwork of available threads that have been sutured together in an attempt to represent some form of coherence’.

Findings and discussion

Narrative thread 1: habits of a classical musician

Carys talks about ‘not being able to move from the traditions…I play what’s on the page; if there’s a piece in front of me, I like playing it as it is’. She reflects on the limited autonomy she is afforded as a choral singer, acknowledging that ‘you’re not moving too far from what the conductor wants’.

Berwyn, as a classical trumpet player, likes ‘ just the old-school technique part of performance. My attempts at jazz say that I’m a classical musician. I would say I’m not very creative. I like structure, I like things to be black and white. I’m more of a tick the boxes, make sure everything is correct. That’s probably due to my background, I think, musically … I like to feel in control.’

Idris enjoys analysing and writing pastiche Bach chorales because ‘ you have got Bach’s rules and you’re supposed to follow them. That helped me because I knew what I needed to aim for. I sometimes do struggle to just let loose and try new things. I don’t like to fail, so sometimes I will miss out on opportunities just because I know, “Well, I’m not very good at that,” or, “It’s out of my comfort zone”’.

Discussion

Prior to commencing their classroom teaching experience as student teachers, the participants demonstrated traits of the classical musician. Carys’s tacit acknowledgement of an innate hierarchy, with her reluctance to move away from the composer’s intentions on the printed page, Berwyn’s preoccupation with refining his technique, and Idris’s fixation on fulfilling preset criteria, all point towards a convergence of thinking and compliance of action typically aligned to the classical musician’s identity (Benedek et al., Reference BENEDEK, BOROVNJAK, NEUBAUER and KRUSE-WEBER2014; Bull, Reference BULL2024; Burnard, Reference BURNARD2012; Creech et al., Reference CREECH, PAPAGEORGI, DUFFY, MORTON, HADDON, POTTER, DE BEZENAC, WHYTON, HIMONIDES and WELCH2008; Dwyer, Reference DWYER2016; Green, Reference GREEN2002; Perkins, Reference PERKINS, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015; Sagiv & Hall, Reference SAGIV, HALL, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015; Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015; Welch, Reference WELCH, HARGREAVES, MIELL and MACDONALD2012; Reference SAGIV, HALL, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015; Welch et al., Reference WELCH, PAPAGEORGI, HADDON, CREECH, MORTON, DE BEZENAC, DUFFY, POTTER, WHYTON and HIMONIDES2008; Woody, Reference WOODY2007). Both Berwyn and Idris feel safe when they have structure and are in control (or possibly being controlled by the composer, the notation, the conductor). Both suggest that they would not be able to cope without it. Carys also seems to accept without question the lack of autonomy and ownership she has in the musical decision-making as a chorister and is happy to relinquish power and control to the conductor. This accords with Dwyer’s (Reference DWYER2015) suggestion that conductors are afforded the most prominent place in the institutional hierarchy, also Sagiv and Hall’s notion of compliance (Reference SAGIV, HALL, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015) and Bull’s observation of the silencing of the performer’s voice (Reference BULL2024). Yet, migration can be a tricky business, as Berwyn has discovered. His classical performer behaviours, based on the disciplined practice of technique, replication and control, prevent him from migrating successfully into a musical genre that relies on a readiness to ‘leave [musically] beaten paths’ (Benedek et al., Reference BENEDEK, BOROVNJAK, NEUBAUER and KRUSE-WEBER2014, p. 120) and a tolerance for taking risks.

Narrative thread 2: pedagogic improvisation

Carys was placed in a school that embraced informal learning pedagogies and, although apprehensive at first – ‘How am I going to manage?’ – quickly had to adapt. She learnt to deviate from her planned lesson if it became necessary, something that she would not do as a classical performer (‘play what’s on the page’), and in doing so, she demonstrated an ability to be flexible, adaptive and responsive, and improvise in the moment: ‘With teaching, you can plan something and then last minute it could go completely wrong, so then you have to change it completely and try something else. We did a task with Year 10 and they didn’t get it at all and you’d have thought they’d get it straightaway. Well, I had to completely adapt the lesson then, go back to basics and try another way. So, I guess, yeah, you just have to think on the spot ’.

Berwyn started learning to teach in a school with a reputation for promoting a music curriculum that embraces creative learning, yet he prefers ‘to conform than be different as a teacher. I would much rather have them say, “Okay, here’s what you’re teaching tomorrow. This is what they [pupils] need to do. Here it is”. Have it really structured and controlled throughout the whole lesson because that’s who I am. That’s how I learned. That’s how I study.’ However, as the placement progressed, Berwyn embraced the music department philosophies and learnt to ‘ go with the flow ’, deviating when the need arose taking account of pupils’ learning choices. It also fostered in him a newfound freedom and confidence as a musician: ‘Being a trumpeter, not being able to almost hide away with your instrument, that was something I had to overcome a little bit, but that made me feel very creative, for example, if you’re going to demonstrate some blues patterns or something or how to improvise. That made me feel very creative and it made me feel like a better teacher too. Being able to model using those new skills was really nice’.

Idris, after a first placement that advocated pedagogies that were akin to the classical tradition and, therefore, very much in his ‘comfort zone’, moved to a school that had a very different approach. He quickly realised that replicating what he had done in the first school was not going to work and adapted his thinking to be prepared to tolerate uncertainty, be flexible and responsive, and be ready to adapt his practice in the moment: ‘Even my first day, I was thinking, “I don’t know if I can cope with this”, but I got stuck in and I just had to go with the flow and speak to the other staff. You don’t know what you’re going to expect of the children there. Each day or each hour is completely different. You do have to expect the unexpected and be prepared to go off on a tangent. You could never stick to a lesson plan, just thinking on your feet a lot more’.

Discussion

All three student teachers display the capacity to be pedagogically responsive, flexible and improvisatory. Whilst teachers need to show discipline in preparing sufficiently (learning objectives, resources, etc.), they also need to respond, which can mean moving away from, even abandoning, the intended plan to suit pupils’ emerging needs (Abramo & Reynolds, Reference ABRAMO and REYNOLDS2015). We see Carys employing this exact tactic when Year 10 are struggling, and when Idris goes ‘off on a tangent’ and is prepared to ‘think on your feet more’. This intuitive capacity, behaving in a more instinctive and improvisatory manner, reveals behaviours that are very different from their more measured, controlled and disciplined approach as classical musicians. Clearly, as classical musicians, Carys, Berwyn and Idris need to be responsive to other musicians in the moment and use their instinct and intuition to react appropriately, often in an equally high-stakes environment (i.e., a public performance), but there is secure evidence in their narratives that this behaviour is significantly heightened within their pedagogic selves. They are honing a type of pedagogic improvisation to react flexibly and to think and act ‘on the spot’. Improvisation in music usually involves ‘the insertion of improvised passages into a pre-designed structure’ (Green, Reference GREEN2002, p. 42). Carys and Idris describe being willing and able to move away from their ‘pre-designed structure’, the devised lesson plan, when the need arises and pedagogically improvise. Abramo & Reynolds (Reference ABRAMO and REYNOLDS2015, p. 40) call this a ‘reactive improvisation’, creating something different in the moment in response to pupils’ needs. In this sense, both jazz musicians and teachers ‘face a challenge in balancing the risk of failure with the creative tension involved in embracing mistakes and reacting to them to form creative new pathways for action’ (Beauchamp et al., Reference BEAUCHAMP, KENNEWELL, TANNER and JONES2010, p. 148). In the ecology of resources which constitute a classroom, this accords with Kamoche et al.’s (Reference KAMOCHE, CUNHA and CUNHA2003, p. 2025) definition of organisational improvisation as the ‘conception of action as it unfolds, drawing on available cognitive, affective, social and material resources’.

The migration away from their classical musician behaviours is marked. As teachers, they resist their classical performer instinct to ‘play what’s on the page’ (the lesson plan) and begin to inhabit behaviours more typical of the jazz musician: to think and act divergently and be brave enough to go off in a different and unexpected direction (Fautley & Savage, Reference FAUTLEY and SAVAGE2007, p. 5).

Narrative thread 3: tolerating uncertainty, relinquishing control and loosening hierarchy

All three student teachers show a willingness to share control with their pupils, giving them autonomy over the musical and creative choices they made in lessons, and in turn, creating a more democratic learning environment.

Carys: ‘Like, with Year 8, I gave them the choice at the start to pick a few songs that they wanted to do. With the group work, they had to decide how they were going to practise it, what speed they were taking it. It was all more of them and I was more of, like, a facilitator, like stepping back, but giving some ideas now and again, but not just commanding them, telling them what to do’.

Berwyn: ‘I gave them [the pupils] the opportunity to go off on their own. I‘ve learnt that if you give them some space and responsibility, it can work out really, really well and you can be really impressed with how creative young people can be.’ Berwyn’s second placement was in a music department that favoured a more formal, classically-aligned pedagogic approach, where pupils ‘Play what they’re given [by the teacher] and if that’s too easy then we’ll get move you onto something else.’ Berwyn realised that, despite his natural musical affinities being closer to the ethos of second placement school, he preferred the creative pedagogies in his first school: ‘I didn’t like it as much, to be honest with you, which is a bit of a surprise, but after allowing students space and responsibility and seeing how creative young people can be. It’s amazing. I wanted them [pupils in second school] to have that opportunity as well, and when we just didn’t do that, or at least with the schemes of work when I was there, and I didn’t like that so much.’

Idris: Having gone from a very structured formal environment in his first placement, he quickly learnt ‘to expect the unexpected’ in his second placement and ‘allow pupils to lead the direction of their learning. If that’s what they’re focusing on, that’s what they’re enjoying, just go with it because it wasn’t worth disrupting their learning.’

Discussion

These vignettes demonstrate Carys, Berwyn and Idris learning to become increasingly ‘comfortable with ambiguity’ (Abramo & Reynolds, Reference ABRAMO and REYNOLDS2015, p. 41) and more open to accepting the unknown and unfamiliar. A marked transformation can be seen, particularly in Berwyn, who, in his musician identity, craves the classical musician traits of structure and control. Yet, as a teacher, he strikes a balance between structure and freedom (for both him and his pupils) that results in a working environment where both pupils and teacher can engage in autonomous activity and where Berwyn discovers a creative confidence that feeds his pedagogic self-efficacy. Key to him becoming more tolerant of uncertainty is his developing ability and desire to engage in divergent thinking, where outcomes are not fixed but open to interpretation (Abramo & Reynolds, Reference ABRAMO and REYNOLDS2015), and new pedagogic meanings are made (Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015). Crucially, Berwyn is also encouraging the same quality in his pupils, enabling him to make new discoveries and negotiate outcomes with them as a result. Here, he demonstrates the antithesis of the ‘pedagogy of correction’ (Bull, Reference BULL2024, p. 46) convention that as a musician he would be used to and gives time and space for creative exploration and musical ‘messing around’ (Bull, Reference BULL2024). Indeed, when back in a known, formal, classically influenced learning environment in his second placement, he realises the restrictions and limitations of employing more didactic pedagogic practices and declares his preference for strategies that encourage both teacher and pupil to share creative control. Carys also advocates pupil choice, and when we think back to Wright’s Reference WRIGHT2008 study, the kinds of creative decisions Carys is affording her pupils are exactly the kinds that the pupils of Mrs. Metronome craved but were denied. In Wright’s work, a rigid hierarchy was in place in Mrs Metronome’s classroom, where ‘the ultimate power over curriculum and pedagogy rested firmly with the teacher’ (Wright, Reference WRIGHT2008, p. 389). We suggest that Carys, Berwyn and Idris, in affording their pupils learner agency and encouraging them to be co-participants in the direction of their learning, made a conscious choice to loosen these classroom hierarchies as they formed a new pedagogic identity which was starkly different from their Western European classical musician selves but which was more aligned with the learning preferences of their pupils.

The student teachers were not the only individuals to show a willingness to relinquish control and loosen existing hierarchies. Their mentors demonstrated the same behaviours, as the vignettes at the start of the next section demonstrate.

Narrative thread 4: trusting and collaborative relationships

All three student teachers were given consistent mentor support, trust and agency to explore and be autonomous in developing their pedagogic practice. The mentors seemed to be able to cultivate an environment that was collaborative and reciprocal:

Carys: ‘I think, yeah, my mentor gave me that freedom to just do what I wanted, really, so I’ve literally been able to go ‘oh fancy trying this’ and then just like seeing where it goes then, so yeah’.

Berwyn: ‘ they were really open to have me try anything I wanted to and especially with the students. They wanted students to be as creative as possible and that meant I needed to be creative, too, as a teacher. You almost take it week by week or day by day and just try and make sure your mentors are happy with the way you’re teaching’.

Idris: ‘because of school culture all three [music] teachers were on the same wavelength. They were very much more relaxed, very open. Literally they’d said to me, “This is what we’re doing, but you can do what you want”, and very supportive’ .

Discussion

Undoubtedly, one of the more significant factors in the ‘conditions for living’ (Wright, Reference WRIGHT, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015, p. 79) as a student teacher is the relationship with their mentor. The reciprocal, egalitarian and collaborative relationship that Carys, Berwyn, Idris and their mentors developed is unlike the ‘master-apprentice’ model that they would be familiar with in their learning as classical musicians (Almqvist & Werner, Reference ALMQVIST and WERNER2024; Bull, Reference BULL2024) and more akin to the transient and distributed hierarchy (Green, Reference GREEN2002) in the domain of the popular musician. Mok (Reference MOK2014, p. 181) suggests that learning in this domain is collective and collaborative with ‘natural interaction or exchange of ideas’. The loosening of the hierarchies in place of a more collaborative model of mentoring moves towards a dialogic approach (Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015). It creates a space for the student teachers’ voices to be heard, both pedagogic and musical, and for the mentors to ‘see things from the perspective of those other voices’ (Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, BENEDICT, SCHMIDT, SPRUCE and WOODFORD2015, p. 299). Yet, covert power is still present. Berwyn’s classical background means he does not initially feel confident in his mentor’s pedagogic approaches but chooses to adopt a more creative approach, as this is the preference of his mentor. Tellingly, he says, ‘You almost take it week by week or day by day and just try and make sure your mentors are happy with the way you’re teaching’, and clearly this comment reveals a desire to please his mentor. Since Berwyn’s mentor is also his assessor, this is significant. However, it is clear from his narrative that, by choosing to accept the philosophies and abide by the mentor’s ground rules, he does gain a newly found confidence and belief in a pedagogy that is far removed from his initial preferred approach.

Narrative thread 5: pedagogic development and the aspirations of Curriculum for Wales

The three student teachers have somewhat differing perceptions about how prepared they feel to embrace the opportunities and challenges of the new curriculum in Wales.

Carys: ‘It obviously does make me feel a little scared because it’s a totally different step…but I think with this year, with like trying things out, and having loads of opportunities to speak with other subjects [teachers], see what you can do together and, you know, if you try it and it goes really well then share it as well [because] you’re going to get ideas from everywhere.’

Berwyn: ‘It would make me nervous. It does make me nervous, to be honest with you, because you may need to bring to the table a bunch of skill sets that I don’t know that I have. Thinking of cross-curricular things…this isn’t for me. I love music, and I love teaching it so much. I think I would give it a go, but I’m apprehensive. It’s a never-ending game of learning’.

Idris: ‘ I’d embrace it. I’m excited and motivated [by it] and I’d really like to incorporate that into my teaching. You’ve got to be very open-minded, but it’s not a bad thing at all. Just don’t be afraid to try anything, that’s what I’ve learned’.

Discussion

Despite some differing views on their capacity to teach within the changing pedagogic landscape of Curriculum for Wales, it is clear that the dispositions that the student teachers developed during their training year had given them some of the tools they will need, even if their confidence to do so is at different stages. For Carys, although she is nervous, the creative capacities of resilience, trial and error learning and being prepared to make and learn from mistakes have developed. The collaborative and reciprocal relationships she developed with her mentor in her placement school have also perhaps influenced her perceptions. Berwyn has come far in his creative journey, but the new Welsh curriculum, which asks its teachers to enter into the unknown in terms of cross-curricular teaching and pioneer a new set of creative pedagogies, is a step too far for him at this stage. The cautious and fearful Berwyn returns. Perhaps this is currently beyond him at his stage of development, but we must remember how far he has travelled in his journey from musician to teacher, and his last sentence hints that it might not be out of the question for him forever. Although Idris has secured a teaching post outside Wales, he looks forward to the new Welsh curriculum and shows a confidence and an openness that was absent prior to learning to teach. Considering Idris started his training year feeling comfortable in situations he could control and being afraid to try new things, he has come a long way.

There is solid evidence in the three student teachers’ narratives that they have indeed moved beyond the Western European classical behaviours, beliefs and values embodied in their university education (Breeze et al., Reference BREEZE, BEAUCHAMP, BOLTON and MCINCH2023) and in their classical musician identity and now seem capable of playing their part in developing the ‘transformative student-centred curriculum’ (Power, Newton & Taylor, Reference POWER, NEWTON and TAYLOR2020, p. 317) required for Wales.

Conclusion

The narratives of Carys, Berwyn and Idris suggest that student music teachers from classical backgrounds can migrate successfully from their musical domain into a pedagogic one without being impeded by the habitual norms that reside in their identities as classical musicians, particularly with regard to hierarchy, power and control. Moreover, the behaviours and attitudes that are central to their musical identities prior to starting to teach do not necessarily influence their emerging pedagogic identities or their developing practice. However, if student teachers are to ‘kick the habitus’ (Wright, Reference WRIGHT2008), supportive ‘conditions of living’ (Reay, Reference REAY1995, p. 357 in Wright, Reference WRIGHT, BURNARD, HOFANDER-TRULSSON and SÖDERMANN2015, p. 79) are crucial in their pedagogic transformation, particularly the relationship they develop with their mentor. Indeed, the findings suggest that transformation is most successful when supported by mentors who foster a reciprocal, collaborative, peer-like relationship. A curriculum that offers teachers and learners subsidiarity and agency is also a significant factor. Despite identifying as classical musicians (and, for Carys, Berwyn and Idris, this did not change throughout the whole of the research), the nature of these collaborative experiences aligns more closely with that of the popular musician (Benedek, Reference BENEDEK, BOROVNJAK, NEUBAUER and KRUSE-WEBER2014; Green, Reference GREEN2002; Mok, Reference MOK2014), and less formal, more transient and democratic collaborations form a catalyst (possibly the fundamental catalyst) for transformation.

In the narratives of all three student teachers there is clear evidence that the control, hierarchy and ‘ultimate ownership of curriculum and pedagogy’ (Wright, Reference WRIGHT2008, p. 399) that were the hallmarks of Mrs Metronome’s classroom in Wright’s research eighteen years prior were not the hallmarks of Carys, Berwyn and Idris. A focus on shared ownership, which genuinely took account of pupil voice and choice and their ability to become adaptive, flexible and improvisatory in their response, positively influenced their pedagogic development.