1. Introduction

Today, when it comes to penal matters, legal scholars and practitioners of international law tend to draw a distinction between ‘international crimes’ and ‘transnational crimes’. But it would be misleading to suggest that there is consensus on the precise meaning of these terms. Authors have assigned them a wide variety of definitions in the literature. For our purposes, the phrase ‘international crimes’ should be taken to mean ‘breaches of international rules entailing the personal criminal liability of the individuals concerned’.Footnote 1 This conception is similar to, but broader than, that preferred by a group of scholars who have described ‘international crimes’ as ‘those offences over which international courts or tribunals have been given jurisdiction under general international law’.Footnote 2

In contrast, the notion of ‘transnational crimes’, apparently conceived by a United Nations body, is said to describe ‘certain criminal phenomena transcending international borders, transgressing the laws of several states or having an impact on another country’.Footnote 3 Or, put more succinctly, ‘transnational crimes’ is a reference to ‘crimes with actual or potential trans-border effects’.Footnote 4 That is to say, those offenses ‘which are the subject of international suppression conventions but for which there is as yet no international criminal jurisdiction’.Footnote 5

The simplicity of this two-part categorization of crimes understates the surprising uncertainty, and masks serious philosophical and other disagreements among scholars, as to what features make some crimes ‘international’ and others ‘transnational’ in nature.Footnote 6 It also elides the confusion about the legal consequences, if any, that may flow from the commission of the crimes that fall into these apparently separate categories for individuals as well as for States. The bare distinction further implies that there is greater clarity than actually exists regarding what specific offenses fall into these seemingly impermeable categories, their origins or sources, and the criteria for their inclusion in one basket or the other, and in some cases, not at all.

As Bassiouni has argued, part of the reason for the current uncertainty stems from the lack of a widely accepted definition of what an international crime is and the absence of universally accepted criteria regarding what qualifies certain penal prohibitions as crimes under international law.Footnote 7 The result is that entire legal regimes (‘International Criminal Law’ or ‘ICL’ and ‘Transnational Criminal Law’ or ‘TCL’) centred around what Cryer calls ‘fuzzy sets’Footnote 8 have developed in a rather ‘haphazard’Footnote 9 manner, with the distinction between the various groups of offenses and the categories of which they form a part varying – sometimes dramatically – based on the nature of the social, State or community interest that is being protected as well as the harm that is being sought to prevent through criminalization.

This chapter is an early exploration into the regional (African) approach to international and transnational crimes. In the absence of a unified theory of what makes each of the above crimes groupings what they are, under international or transnational law, Section 2 will start with an examination of the five-part criteria that a prominent international law scholar has offered as a possible way to distinguish between various offenses. Though perhaps imperfect, as they were deduced based on empirical observations of what States seem to do rather than rooted in a grand penal theory, Section 3 will then use that suggested classification to assess the material jurisdiction of the African Court of Justice and Human and Peoples’ Rights (‘African Criminal Court’Footnote 10 – the first regional criminal court to be established anywhere in the world). The legal framework for the latter tribunal has already attracted serious criticism. Part of the reason for the controversy stems from its inclusion of an explicit immunity clause for incumbent senior government officials and its perceived status as a result of African government backlash against the fledgling permanent International Criminal Court.

A less strident criticism, which is nevertheless theoretically interesting and therefore worthy of consideration, arises from the Malabo Protocol’s fusion of ‘international’ and ‘transnational’ crimes in a single treaty. I argue in this chapter that, rather than focus on which particular offenses are placed into one or the other of this presently largely binary scheme, the emerging practice of African States suggests that it is probably more helpful for legal scholars to start examining the source of the relevant prohibitions and the reasons for their criminalization as well as the legal consequences and implications of their commission. This would better enable us to appreciate the similarities, and differences, between these crimes. It also permits us to explore synergies and best practices that may exist to strengthen each of their underlying legal frameworks.

The last part of the chapter, Section 4, draws some preliminary conclusions. It thereby sets the stage for the analysis that follows in the rest of this part of the book.

2. The Characteristics of International and Transnational Crimes

This chapter stars from the premise that, in the ordinary course, states in Africa – or for that matter any other region of the world – are free to criminalize any conduct that they deem will cause harm to individuals or communities within their jurisdiction or within their effective control, subject only to constitutional or other limits imposed by international law. In prescribing crimes, they are at liberty to act alone under national law. Where the systems contemplated at the national level are not doing the job for one reason or the other, say because of a lack of willingness or lack of capacity to do so, they are free to come together to do collectively what each of them are able to do on their own. In that sense, and reflective of their sovereign nature and the traditional bases of jurisdiction recognized under international law, they can freely assert their jurisdiction to prescribe offences as well as delegate their jurisdiction to adjudicate, and jurisdiction to enforce to a domestic or a regional court – such as that proposed by the AU for the African region – or even an international penal tribunal established for such purpose. It follows that the blending of various types and categories of crimes into a regional treaty does not necessarily require additional doctrinal justification for them to prohibit such offenses and to seek to punish those who perpetrate them.

A. The Nature of International and Transnational Crimes

The doctrinal match for the criminological phrases international crimes and transnational crimes reflect a plethora of definitions, many of which are not always consistent. For starters, the former as classically understood, was usually taken as a reference to what some scholars today more frequently label transnational criminal law. That is, the body of domestic law referring to those parts of municipal law addressing crimes that has cross border or extraterritorial origins and or effects.Footnote 11 This was the case at least until the United Nations Security Council established the first modern ad hoc international criminal tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda in 1993 and 1994 respectively. But the terminological confusion, which tended to lead to the loose equation of transnational criminal law with ‘traditional international criminal law’ and the law concerning the crimes within the jurisdiction of the UN ad hoc tribunals as ‘new international criminal law,’ does not end there.Footnote 12

In fact, it appears to also go the other way. So that, in the literature, it is not unusual to find authors alluding to transnational criminal law when they proceed to actually discuss ‘crimes of international concern.’Footnote 13 The latter would cover a wide range of conduct with little commonality other than the decision, or acceptance, by States that some form of inter-State cooperation regime or some coordinated international action must be taken by them within the domestic sphere to suppress such behaviour.Footnote 14 It is also interesting that, in a way, the resurrection of State interest in the so-called serious crimes of international concern forming part of what many of us would consider international criminal law, at least as administered by the International Criminal Court (‘ICC’), originated in part from Trinidad and Tobago’s proposal to criminalize drug trafficking – itself a classic transnational crime – which ironically did not make it into the statute of the permanent international penal tribunal.Footnote 15 Yet, in a further irony, the most recent work on a draft crimes against humanity convention, at the International Law Commission (‘ILC’), has drawn considerable inspiration from the statute of the ICC for its definition of the offence at the same time as it placed great reliance on various global transnational crimes conventions for its mutual legal assistance, extradition and other clauses. Both fields, it seems, are beginning to converge substantively as well as procedurally.

In any event, despite the lack of definitional clarity, the traditional distinction between international and transnational crimes on the one hand, and between international and transnational criminal law on the other, now provides at least a generally agreed basis for scholars to distinguish between so-called international crimes stricto sensu (that is the post-Nuremberg law governing the so-called ‘core crimes’ – genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression) and transnational crimes (covering a diverse set of crimes such as slavery, drug trafficking, or money laundering). The former are seen as capturing those acts that implicate the fundamental values of the international community as a whole. As the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC Statute) would later put it in its preamble, those offenses are among those that particularly ‘threaten the peace, security, and well-being of the world’.Footnote 16 On the other hand, transnational criminal law provides for the exercise of national jurisdiction by states in respect of conduct which has transnational implications. These, by their nature, involve or affect the interests of more than one State.

But, in an attempt to draw clear boundaries to help minimize the conflation, scholars have suggested that the crucial distinction between these crime categories is that in addition to the distinctive normative goal of protecting core Grotian or Kantian community values, as Boister and Kress have suggested, international criminal law actually creates a system of direct penal responsibility for individuals under international law.Footnote 17 Here, in this category of crimes, international law basically bypasses municipal law and criminalizes behaviour directly. In other words, these are universal crimes condemned by international law. They must thus be punished irrespective where in the world they are committed and by whom.Footnote 18

On the other hand, when it comes to so-called transnational criminal law, there is an indirect system of liability. That system imposes obligations on States Parties to criminalize certain conduct under their domestic laws as much as some core international crimes conventions do. The obligation here is placed on the State, not on individuals. States undertake to prohibit and punish those among the latter category who commit the crime. The obligation is usually imposed in political contexts that indicate the national authorities want to jealously guard their jurisdiction to prescribe, their jurisdiction to adjudicate and their jurisdiction to enforce the relevant prohibitions rather than delegate them to a distant international penal tribunal over which they have may not have meaningful control.

The regime of ICL now largely addresses itself directly to the individual. It anticipates enforcement of the prohibitions under both national and international law at the national, and in some cases, the international level. The TCL regime, for its part, addresses itself primarily to the State and uses national courts primarily as a means for enforcement. In other words, the latter reflects a web of mutual interstate obligations generating national duties to prohibit the conduct. This is usually supplemented with a specific treaty-based duty to legislate and for a duty to either investigate and prosecute or to extradite the perpetrator, and typically limits the availability of the traditional political offence exception. The degree of enforcement of transnational crimes, as well as coordination between States, will depend on the nature of the specific offence under consideration. It will also reflect the extent to which they (i.e. States) desire to address the threat stemming from the prohibited conduct. The prohibition of such crimes in transnational criminal law regime reflects the concern with the self-interest of sovereignty conscious States. The ICL regime, while secondarily accounting for the stability and other interests of states, seems mainly aimed at protecting human beings and the preservation and even promotion of certain fundamental values within the ‘jus puniendi’Footnote 19 of the international community as a whole.Footnote 20 Values that include the protection of human rights and freedoms, including the right to life and at least a soft right of victims of atrocity crimes to some form of remedy and reparation.

Still, the distinction between ICL and TCL should not be overemphasized. There are certainly some remarkable overlaps between the two regimes. For instance, while ICL did insist from its founding – in what was then a rather radical idea – ‘that individuals have international duties which transcend the national obligations of obedience imposed by the individual state’,Footnote 21 some of the main treaties that prohibited conduct that is now widely considered to fall within the realm of international offenses initially permitted or imposed upon states the duty to prosecute or punish such criminal conduct within their municipal law. The addition of international criminal courts as enforcement mechanisms, initially only ad hoc and eventually also permanent, came much later. At present, there is no Transnational Criminal Court, in the same way that there is an ICC. Nonetheless, for both TCL and ICL offenses, states still bear the primary legal obligation – at least at the domestic level – to investigate and prosecute the suspects who may have committed such crimes. A failure to do so may, in some cases, give rise to a duty to extradite that person upon request of another State willing and able to prosecute.Footnote 22 This is the case for crimes like torture, which is both an international crime found under war crimes and crimes against humanity, but also a separate subject of a suppression treaty (i.e. the Convention Against TortureFootnote 23). Of course, in the case of what we might label purely international crimes in relation to one of the current 123 States Party to the ICC, complementarity might require the unwilling and/or incapable State to surrender the suspect to The Hague. The complementarity principle, as a jurisdiction-sorting rule that initially gives priority to concrete actions of national over international authorities, further supports the argument that the distinction should not be overemphasized.

Unlike in most domestic systems, as compared to the international level, there is not at present a comprehensive penal code of crimes at the international level. The ILC, which was tasked in 1947 by the United Nations General Assembly with producing a draft code of crimes for states to consider for adoption, appear to have had no choice but to focus – as per the terms of its actual mandate concerning the topic – on the relatively narrow list of ‘offenses against the peace and security of mankind’.Footnote 24 Despite its many useful contributions, including to the development of the corpus of modern international criminal law through, inter alia, the formulation of the Nuremberg Principles and the draft statute for the permanent international penal court, in addition to the draft code of crimes against the peace and security of mankind. The ILC did not explicitly adopt a comprehensive theoretical framework setting out preconditions for an international crime or the policy that should guide international criminalization when the project was finally completed in 1996.Footnote 25

B. A Workable Analytical Framework

Bassiouni, who probably undertook one of the earliest and most complete efforts to clarify the concept of international crimes, has rightly observed that the international criminal law literature is replete with terms all of which are aimed at identifying the various crimes categories at the international level.Footnote 26 This includes the use of the descriptors such as crimes under international law, international crimes, international crimes largo sensu, international crimes stricto sensu, transnational crimes, international delicts, jus cogens crimes, jus cogens international crimes, and even a further subdivision of international crimes referred to as core crimes.Footnote 27 He proposed to bring some type of order by seeking to address two things. First, the criteria that should guide the policy of international criminalisation. Second, after having done so, to identify the particular characteristics the presence of any of which would, if found, be sufficient to delimit what constitutes an international crime.

With respect to the policy criteria, Bassiouni suggested five main guidelines, as follows:

(a) the prohibited conduct affects a significant international interest, in particular, if it constitutes a threat to international peace and security;

(b) the prohibited conduct constitutes egregious conduct deemed offensive to the commonly shared values of the world community, including what has historically been referred to as conduct shocking to the conscience of humanity;

(c) the prohibited conduct has transnational implications in that it involves or effects [sic] more than one state in its planning, preparation, or commission, either through the diversity of nationality of its perpetrators or victims, or because the means employed transcend national boundaries;

(d) the conduct is harmful to an internationally protected person or interests; and

(e) the conduct violates an internationally protected interest but it does not rise to the level required by (a) or (b), however, because of its nature, it can best be prevented and suppressed by international criminalization.Footnote 28

Having set out the above criteria, he next considered the ten features that make something an international crime in international treaty law. These were:

(1) explicit or implicit recognition of proscribed conduct as constituting an international crime, or a crime under international law, or a crime;

(2) implicit recognition of the penal nature of the act by establishing a duty to prohibit, prevent, prosecute, punish;

(3) criminalisation of the prohibited conduct;

(4) duty or right to prosecute;

(5) duty or right to punish the proscribed conduct;

(6) duty or right to extradite;

(7) duty or right to cooperate in prosecution, punishment (including judicial assistance);

(8) establishment of a criminal jurisdictional basis;

(9) reference to the establishment of an international criminal court or international tribunal with penal characteristics; and

(10) no defence of superior orders.Footnote 29

The assessment of whether a particular crime fulfils one or more of the foregoing characteristics could probably best be done empirically. The presence of any of those characteristics, in any convention, was thus apparently sufficient in the practice of states for him to label the prohibited conduct an ‘international crime’.Footnote 30

Several observations can be made about the above policy criteria and the characteristics of international penalization. First, Bassiouni’s interesting scheme appears to have found some general support among scholars as a useful starting (not ending) point for discussion.Footnote 31 It offers a workable framework for discussion on the classification of such crimes, though their full practical consequences cannot be explored here given our limited focus. Nonetheless, as some academics such as Cryer have noted, the foregoing criteria are not necessarily ‘self-applying, and the judgments that they are fulfilled are, for the purpose of positive international criminal law, subjective’.Footnote 32 Second, and as Einarsen has also observed, Bassiouni does not explain the sources of the five policy criteria.Footnote 33 Rather than being grounded on a theoretical framework, they appear to be descriptive of a wide variety of penal treaties thereby raising questions about their potential prescriptive value. Third, the history of international criminalization does not always show that States have systematically or consciously adopted and applied these criteria objectively when determining what offenses to prohibit or not. This would be consistent with the free hand that they have under principles of international law to regulate matters within their domestic spheres.

Nonetheless, by providing an empirical study based starting point for debate, it seems sufficiently clear that we can probably judge whether some of the crimes that have been proposed for the African Criminal Court offer a basis to regulate conduct as criminal in nature. This, of course, goes above and beyond what is required because international law does not demand a justification from States in their assertion of jurisdiction – as the Permanent Court of International Justice clarified in the classic Lotus Case, a position that has been admittedly somewhat softened since then. We can still nonetheless query, by careful analogy, whether the mixed basket of crimes contained in the Malabo Protocol carry with them some or all of the similarities and logic of the established crimes to explain, if not necessarily justify, their repression at the regional (i.e. African) level. To the extent that we are here contemplating a system that has been identified as far from coherent, in any event, this useful analytic scheme demonstrates that the variety of offences contained in the regional African instrument may not be outside the norm as may at first blush appear.

Based on the above guidelines, Bassiouni’s study, which obviously reflects a broad instead of narrow conception of what gives rise to international crimes such that it is inclusive of what some might ordinarily consider ‘transnational’ crimes, identified the presence of one or more of the penal features in 281 conventions. He argued that, while it would be ideal for all or most of these ten characteristics to appear in every penal treaty, this was simply not the reality.Footnote 34 He went on to identify about 27 crimes in existing international conventions, which he further subdivided into four general groupings: ‘truly international’ crimes; ‘transnational’ crimes; ‘partly international or transnational’ crimes; and ‘international crimes.’ The practicality of these groupings being the way to enhance their prevention and suppression.Footnote 35 These four broad classes seem to mirror each other and differ only in the quality of being pure or mixed as the language of ‘truly’ or ‘partly’ indicate.

Unlike treaties such as the ICC Statute, instruments addressing the phenomenon of transnational crimes do not establish direct penal liability by defining specific crimes in the same manner that, for example, genocide or crimes against humanity are delineated. Instead, by accepting to sign on to such a treaty as noted earlier, the State undertakes to criminalise in its domestic law the prohibited conduct as well as to provide penalties for the violations. Though the matter may not yet be entirely settled, the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime has provided some useful guidance on what criteria a crime must fulfil to fall within the so-called ‘transnational’ crimes category. Under this approach advanced by the UN, much like Bassiouni’s ten penal characteristics for what makes something an ‘international crime’, the presence of one or more of the following four factors is said to be determinative of ‘transnational crime’ status:

(1) it is committed in more than one state;

(2) it is committed in one state but a substantial part of its preparation, planning, direction or control takes place in another state;

(3) it is committed in one state but involves an organized criminal group that engages in criminal activities in more than one state; and

(4) it is committed in one state but has substantial effects in another state.Footnote 36

Under this methodology, we may conclude that the transnational nature of a crime apparently relies on the existence of cross-border geographical dimensions. This is supported by the main literature on transnational criminal law which seeks to add definitional certainty on TCL as a category. It also implies the fact of several States coming together to engage in some type of cooperation to stem the perpetration of the crime as part of protecting their individual and collective interests.

3. Wither the Categories? The Classification of Crimes in the Material Jurisdiction of the African Criminal Court

A. The Context

The African Court of Justice and Human and People’s Rights, whose creation is contemplated by the Malabo Protocol which, as of writing, has only been signed by eleven African States, will exercise jurisdiction over general, criminal, and human rights matters through three different chambers:

(1) a General Affairs Section;

(2) a Human and Peoples’ Rights Section; and

(3) an International Criminal Law Section.Footnote 37

For the limited purposes of this chapter, I do not engage on the first two types of jurisdiction which are carefully evaluated by other colleagues in this volume. Rather, I ponder the subject matter competence of the last of the three foregoing sections in a way that should inform the subsequent chapters that follow on the specific crimes. More specifically, I will examine what the Malabo Protocol defined as ‘international’ crimes as listed in its Article 28A. There is, of course, much that could be said about the subject matter jurisdiction of the African Criminal Court, triable in the International Criminal Law Section.Footnote 38 However, the discussion here is limited only to the description (‘international crimes’) that the drafters gave to the 14 crimes contained in the court’s subject matter jurisdiction. This issue is of interest, not only because of the seeming confusion that exists in the literature on what makes a crime an international as opposed to a transnational one, which traditional distinction we could use the Malabo Protocol to test, but also because it is evident that the invocation of that label in the circumstances of this one instrument will be controversial. Controversial because, at the least, the classification of the crimes as ‘international’ threatens to undo the conventional paradigm among scholars and policymakers that, until recently, attempted to draw a somewhat neat division separating international from transnational crimes.

Partly because of this, and the way the Malabo Protocol relies on an eclectic mix of treaty sources for the crimes contained within the African Criminal Court’s jurisdiction, it is important to discuss these offences. This exercise becomes that much more necessary because it offers a sufficient basis to compare the African regional instrument with the international penal tribunals that have preceded it, again, even if this is not necessarily required to justify the form of the regional prohibitions under international law. The clarification may also be helpful for both theoretical and practical reasons. Indeed, in relation to the latter aspect, some scholars, such as Van der Wilt, have already relied on the conventional international versus transnational crime distinction to propose that this categorization could enable a division of labour that could help avert future jurisdictional conflicts between the African Criminal Court and the ICC.Footnote 39 This is an interesting proposal, though given the arguments of this paper, I remain doubtful whether the international-transnational crimes divide could by itself be a sufficient basis to properly resolve any jurisdictional conflicts that might arise.

B. The Baskets of Crimes in the Malabo Protocol

The ACC contains a more extensive list of fourteen crimes within its subject matter jurisdiction. It differs, in that respect, from the international and other tribunals that preceded it. Indeed, since the seminal Nuremberg trials in 1945, international criminal courts have tended to include only three main offenses within their jurisdictional ambits. Part of the reason for that stems from the practical reality that only the gravest crimes that have been widely condemned under international law can be realistically prosecuted at the international, as opposed to, the national levels. The more extensive list of crimes in the African Criminal Court are, as listed in the constitutive instrument, (1) genocide, (2) crimes against humanity, (3) war crimes, (4) the crime of unconstitutional change of government, (5) piracy, (6) terrorism, (7) mercenarism, (8) corruption, (9) money laundering, (10) trafficking in persons, (11) trafficking in drugs, (12) trafficking in hazardous wastes, (13) illicit exploitation of natural resources, and (14) the crime of aggression. The form of the list does not appear to imply any hierarchy. The first three, and the last one, are typically considered to be among the worst crimes known to international criminal law.

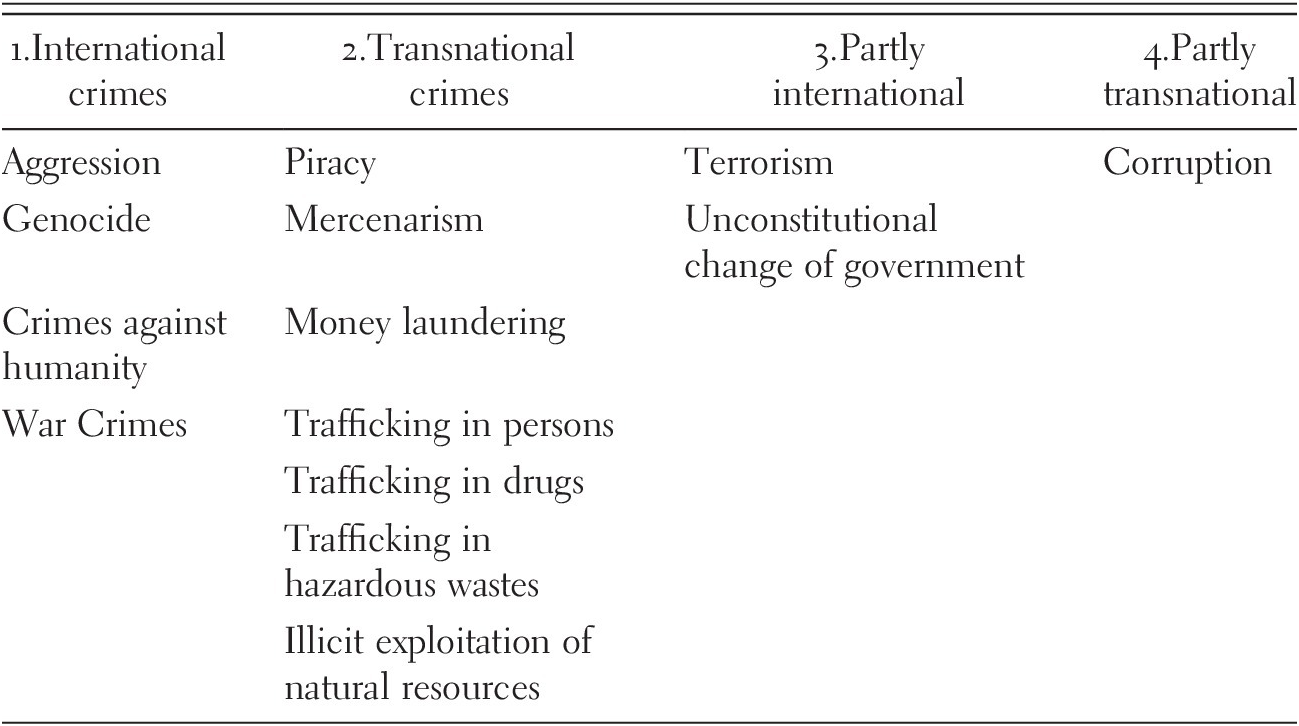

Applying Bassiouni’s ten penal characteristics to each of these offenses in the Malabo Protocol, if we assume all ten are present in each crime, they could reflect up to one hundred and forty. However, even on a cursory review, it becomes apparent that not all of the identified characteristics can be found in each crime. This is to be expected since some of the crimes may contain ideological or political components (for example, the crime of unconstitutional change of government), which implies that they may be expected to have a lower number of actual penal characteristics. Conversely, the offenses lacking political or ideological features might contain a larger percentage of penal characteristics. Whatever the case, for convenience, we can at the broadest level of generality sub-divide the fourteen crimes included in the Malabo Protocol into Bassiouni’s four main categories. These, it will be recalled, are (1) international crimes, (2) transnational crimes, (3) partly international crimes and (4) partly transnational crimes, which can thus be depicted graphically as followsFootnote 40:

| 1.International crimes | 2.Transnational crimes | 3.Partly international | 4.Partly transnational |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression | Piracy | Terrorism | Corruption |

| Genocide | Mercenarism | Unconstitutional change of government | |

| Crimes against humanity | Money laundering | ||

| War Crimes | Trafficking in persons | ||

| Trafficking in drugs | |||

| Trafficking in hazardous wastes | |||

| Illicit exploitation of natural resources |

The discussion, which follows next, considers some of the main features and sources of the crimes contained in each of these four groupings.

1. The International Crimes in the Malabo Protocol

As a branch of public international law, international criminal law relies on the sources of international law. The formal sources are those listed in Article 38(1) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice.Footnote 41 That is: treaties, custom, general principles of law, and as subsidiary means of determining the law, judicial decisions and the writings of highly qualified publicists. It follows that, to the extent that African States have included international crimes in the statute of their regional court, we might expect that they derive from the explicit recognition of the proscribed conduct as constituting a crime under international law, whether found in treaties or pursuant to customary international law composed of state practice and opinio juris.

The four crimes in the Malabo Protocol that are classified as international in nature are sometimes referred to as ‘core’Footnote 42 international crimes, to wit: aggression, crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes. It is obvious that these widely recognized crimes are rooted in international law. Two of the four (that is, genocide and war crimes) are expressed in universal multilateral treaties that are widely endorsed by African States as well as in widely known international instruments such as those produced by the ILC.Footnote 43 The other two (that is, crimes against humanity and the crime of aggression) have not yet been codified in stand-alone treaties. Still, there have been several international instruments which have defined them. Those definitions have generally shaped the more specific ones included in the statutes of various international criminal tribunals. In the case of crimes against humanity, following on persistent academic proposals, there is at present an ongoing effort to develop a draft global convention on the topic within the ILC which has completed the first reading in the summer of 2017 and is expected to accomplish second and final reading in the summer of 2019.Footnote 44 The crime of aggression has been defined in various international instruments, but excepting the carefully and slowly crafted definition contained in the ICC Statute, these have not been treaties.

The inclusion of these four serious international crimes in the Malabo Protocol suggests that African States take seriously their legal duty, presumably based on conventional and customary international law, to prosecute the most serious international crimes whenever they occur on the continent. The stated intention of the African Union in relation to their inclusion was apparently to create, within the African continent, a court that will have the competence to address these crimes to the highest international standards.Footnote 45 In other words, the African system sought to address them as they would have been dealt with by, for instance, the ICC or any other State responsibly exercising universal jurisdiction.Footnote 46

Keeping these goals in mind, in terms of sequence, the decision of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government directing the establishment of the new tribunal specifically requested that the AU Commission (‘AUC’), in proposing a treaty for their consideration, ‘examine the implications of the Court being empowered to try international crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes’.Footnote 47 Thus, war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, were specifically identified as worthy of inclusion in the future regional court’s instrument. This may have come partly because of the context of the creation of the African Criminal Court as a sort of more local alternative to the ICC. As to the fourth international crime (i.e. the crime of aggression), which was later included in the draft statute, the drafters argued that the language of ‘such as’Footnote 48 in the Assembly decision implied that the list of the three core crimes was an illustrative instead of a closed list. It followed that a crime of similar gravity and significance, like the crime of aggression, could be properly included in the statute of the future court.Footnote 49

The above meant that, by fiat of the political directive in the decision of the African Union’s highest organ (the Assembly of Heads of State and Government) and the drafters’ reading of it, the regional court would enjoy jurisdiction over four serious international crimes. Thus, it was not surprising that Articles 28B, 28C and 28D detailed the subject matter jurisdiction of the African Criminal Court concerning the core international crimes – genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes respectively – those being the ones deemed to be the most serious crimes of international concern. They reproduced, in terms of which definitions of those offenses to use, those set out in the Rome Statute. The Report of the Study on the Implications of expanding the mandate of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights to try serious crimes of international concern (‘AUC Report on the Amended African Court Protocol’)Footnote 50 summed up the preferred approach of the drafters as follows: ‘… with regard to these three serious crimes [genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes] where jurisdiction will inevitably be shared with the ICC, the definitions adopted should essentially be similar to (if not better than) those of the ICC.’Footnote 51

The justification provided for this posture was two-fold.Footnote 52 First, though this may only be half true, the report claimed that ‘in terms of the continuous development of law, the Rome Statute definitions represent the most current advances in definitions of these crimes. … Anything less may be retrogression.’ The second justification was framed by considerations of complementarity. The drafters took the view that it was necessary to reflect, in terms of the definition and content of crimes, the latest developments in international law as any variation between the Rome Statute and the African regional instrument portends challenges for complementarity practice.Footnote 53 As they put it: ‘The ICC could be moved to indict a person who is already indicted before the African Court, for aspects of crimes which are covered in the Rome Statute definition and which are absent in the Amended African Court Protocol definition.’Footnote 54

In the result, the Malabo Protocol definitions of the core international crimes reflected this approach. For example, regarding the crime of genocide, the regional instrument includes a new paragraph – among the established statutory or treaty list of genocidal acts – ‘acts of rape and any other form of sexual violence’. The laudable goal here was to reflect more recent advances in the law of genocide – as developed by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (‘ICTR’) in the Akayesu case. Under that jurisprudence, rape acts were seminally determined to amount to genocide if they occur in the right context.Footnote 55

It can be argued, as Ambos does, that the specification of the crime in this way was superfluous, given both Akayesu and the line of tribunal jurisprudence on sexual violence that has since followed it.Footnote 56 However, although a bigger leap in influencing the law of genocide might have been to expand the long contested list of so-called protected groups to cover political and perhaps even cultural groups, the explicit naming and shaming of this phenomenon present in many modern African and other conflicts is, on balance, a highly welcome development. By adding rape acts to the crime of genocide, in the Malabo Protocol, it gives greater clarity and legitimacy to the more modern prohibitions. It thus helps to address a traditional (gender) blind spot for international criminal law, especially given the more gender-neutral framing of the rape acts and the hopefully not-overbroad nature of the second part of the sentence (‘any other form of sexual violence’).Footnote 57

On crimes against humanity, the Malabo Protocol reproduced essentially the same definition as that found in Article 7 of the Rome Statute. This includes the chapeau requirements, including the problematic State or organizational policy element, as well as the same list of prohibited acts as can be found in Article 7 of the Rome Statute.Footnote 58 However, there were also some differences in the text. For instance, the Malabo Protocol definitions includes in its list of forbidden acts an act amounting to crimes against humanity: the crime of torture. The definition contemplates, as ‘torture’, a crime against humanity delineated as the infliction of ‘cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment’ which in the ICC, as expressed in the Rome Statute and Element of Crimes, is limited to the perpetrator’s ‘intentional infliction of severe pain or suffering’ of a person, ‘whether mental or physical,’ in his or her custody and infliction of ‘severe physical or mental pain or suffering upon one or more persons’.Footnote 59 For the future African Criminal Court, a key issue will be how to distinguish the line between ordinary cruel treatment, on the one hand, and torture on the other (which entails a greater degree of cruelty), as that is defined under international human rights (not criminal) law. Indeed, because the difference between cruel treatment and torture is likely one of degree,Footnote 60 the African Criminal Court’s definition captures within its prohibitive scope both severe and less severe forms of ill treatment. In a way, if we leave aside the concern about lesser degrees of inhumane treatment that should be prosecuted at the national level falling within the jurisdictional scope of the regional court, this expansion of the protective umbrella to victims of torture could be a positive expansion of the crime against humanity of torture.

Regarding war crimes, the definition of which was drawn from the Rome Statute, the Malabo Protocol retained, albeit in an attenuated form to the point of a near merger, the traditional distinction between international armed conflict (‘IAC’) and non-international armed conflict (‘NIAC’). But it also attempted to reflect the latest developments in international criminal law, not always successfully or most logically, by adding 14 new war crimes to supplement Article 8C of the Rome Statute.Footnote 61 As to IACs, the African instrument included several new prohibitions amounting to war crimes as well. These included previously controversial issues, at least in the context of the ICJ and the negotiation of the Rome Statute, such as the addition of a penal prohibition banning the ‘use of nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction’. With no African State being a known nuclear weapons jurisdiction, and the high possibility that such weapons would only be deployed by non-African States, it can be argued that this grave crime has as its object those officials in more developed countries that may be tempted to deploy ‘nuclear weapons’ but also other ‘weapons of mass destruction’ during a war involving states from their region. In a region of the world that has seen its share of foreign interventions from former colonial powers, and sometimes other (more private) interests, this gap filling offense could be part of the process of Africanizing international criminal law which the mainstream ICL regime has so far largely resisted.

Finally, in defining the crime of aggression, the Malabo Protocol also used as a starting point the definition in Article 8bis of the Rome Statute. That definition, like all the international crimes discussed above, was taken as a floor – rather than a ceiling – allowing a tweaking of the definition in an attempt to address specificities of the African context.Footnote 62 The specificities of the African context include the extension of the manifest violations to not only cover those prohibited by the Charter of the United Nations, but also to those violations of the Constitutive Act of the African Union, as well as interference with ‘territorial integrity’ and ‘human security’ of the population of a State Party. It additionally envisages, as encompassing within the crime of aggression, a wider category of targeted actors that go beyond the traditional category of aggressor States. These would include a ‘group of states’ (presumably including military alliances such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization), but importantly also ‘non-state actors’ and ‘any foreign entity’. The expansion of the crime to include the latter elements arguably takes more seriously the role of non-state actors such as rebel, terrorists, and militia groups in the commission of heinous atrocities in Africa.

In sum, while it may be that some of the changes made in the Malabo Protocol to the established definitions of international crimes will not in practice add much to the effectiveness of the crime, or potentially even create interpretational difficulties, the takeaway for our more limited purposes of determining whether they are appropriately categorized as international crimes is clear. They are indeed international crimes, and because of their serious nature, they are in fact rightly considered to be among the ‘core’ offenses. In this regard, evaluating them against Bassiouni’s five-part policy criteria, genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, easily constitute prohibited conduct affecting a significant international interest because their commission constitutes a threat to international peace and security in respect of which African States are rightly concerned. They also entail prohibited conduct that is grave enough to shock the conscience of Africans. They are so serious that they can rightly be deemed offensive to the commonly shared values of the world community, of which the African continent is but one part. The commission of these crimes hold international implications and typically involve or affect more than one state in their planning, preparation, or commission, whether through the nationality of their perpetrators or victims, or both, and the fact that the means employed to accomplish them frequently transcend national borders. Finally, the conduct that they attempt to regulate is harmful to internationally protected interests. It flows from this that these crimes, as easily the most widely recognizable ones under modern international criminal law, also fulfil most if not all the ten penal characteristics that Bassiouni’s empirical study sought to identify and classify.

An important question arises whether, in light of the differences in the definitions of crimes introduced by the Malabo Protocol vis-à-vis other definitions of the same offenses in various international instruments, we might begin to see a form of fragmentation of international criminal law. The ILC Study on the issue of fragmentation highlights that rules of international law, including those in specialized regimes like that under study here, could have relationships of both interpretation and conflict. The ILC’s draft conclusions and commentary suggests ways such conflicts could be avoided. Using interpretation as a tool, in the future, may prove useful or even be necessary in future discussions of this issue of regional/particular versus general international criminal law. Still, it would be hard to claim that the ad hoc nature of how ICL has developed to date reflect a coherent unitary model or even understanding of the concept of international crimes let alone a system of international criminal law.Footnote 63

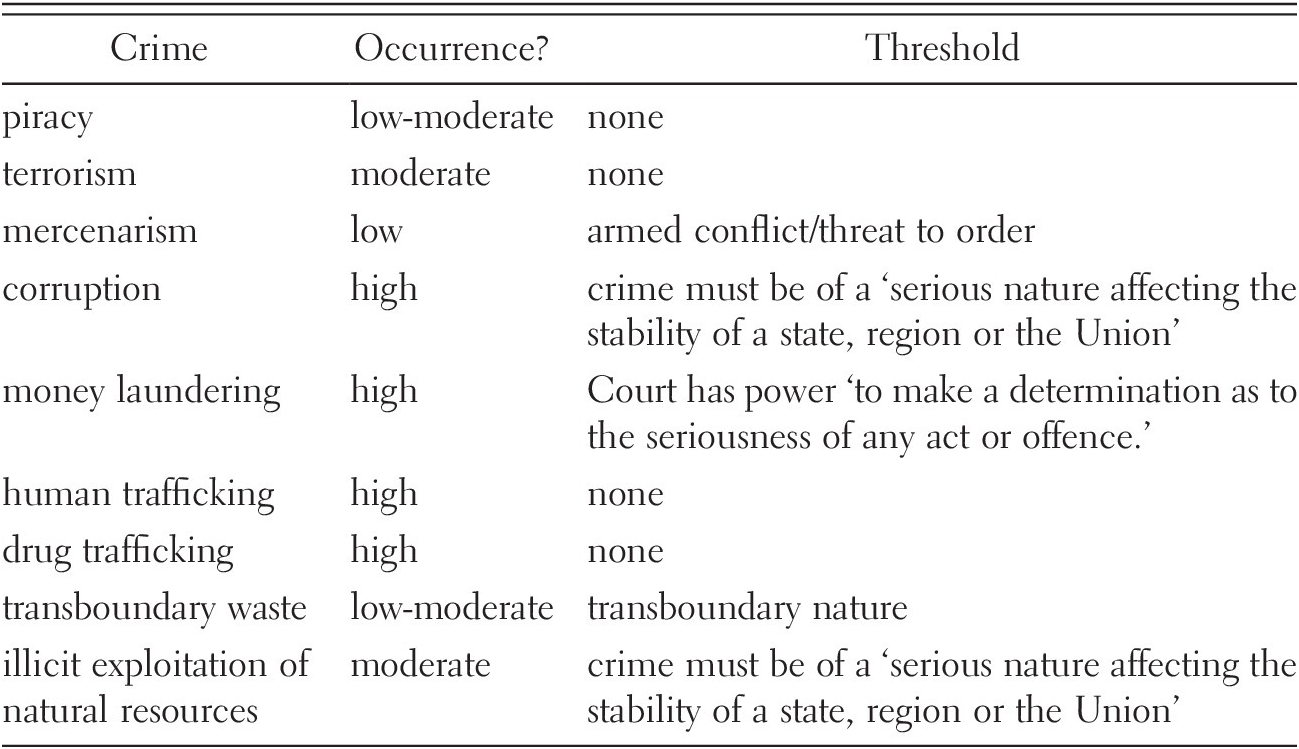

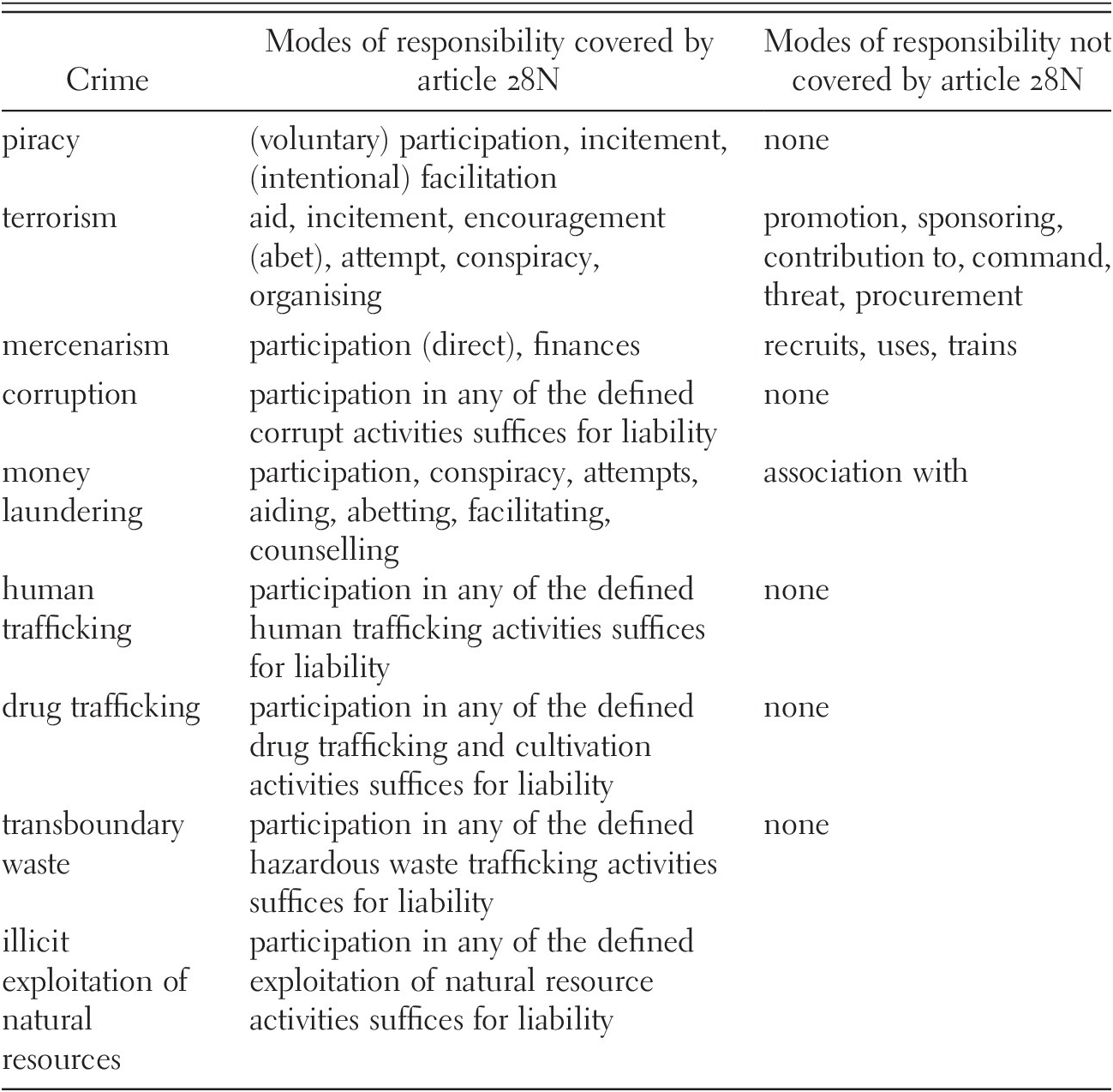

2. The Transnational Crimes in the Malabo Protocol

Besides the above international crimes, the drafters of the Malabo Protocol felt that they did not need to limit the jurisdiction of the African Criminal Court to the core crimes mentioned in the decision of the AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government. They reasoned that, since various African instruments had expressed concerns about several other issues, this had opened ‘the door for the consideration of other crimes, which are of serious concern to’Footnote 64 the African Union.Footnote 65 Having made this determination, the question arose as to how to determine those other ‘serious crimes of concern to African states’. To delimit those, the drafters felt that they should examine treaties that had already contemplated serious matters that the Africa region and other regional economic communities on the continent had addressed over the years. The seven crimes placed in the ‘Transnational Crimes’ category in the above table (i.e. piracy, mercenarism, money laundering, trafficking in persons, trafficking in drugs, trafficking in hazardous wastes, illicit exploitation of natural resources), along with the other remaining crime (i.e. corruption), were drawn from regional conventions as well as other international instruments that some African States had acceded to.Footnote 66 They were therefore essentially justified for inclusion in the Malabo Protocol on the basis of their nature and gravity. They were possessing intrinsic seriousness to the violations, the need to protect the peace, good order and stability of African countries, and in some cases, their serious impact on the countries and indeed the continent as a whole. In this regard, the African Union Commission, in preparing the draft Statute, sought to draw a gravity of the crime based distinction between the ‘serious crimes of international concern’ and those ‘of serious concern to African states’.Footnote 67 They thus particularized the scope of the crimes using this approach.

For reasons of space, and considering that they are discussed at length by other authors in separate chapters in this book, I will not examine each of the individual crimes that I have placed in the transnational crimes category of the Malabo Protocol. Instead, as these are already analyzed in subsequent chapters in this book, I will take two examples (i.e. mercenarism and piracy), one reflecting how the drafters drew from a regional (i.e. African) treaty and the other from an international instrument that has been widely endorsed by African States.Footnote 68 These examples are arguably representative of the wider category of seven crimes in terms of their legal basis. So also is their transformation into regional (mercnearism) and international (piracy) nature such as to account for their particularity for African states. First, recognising that mercenarism has long been an issue of concern to African states as an offense which has the potential to undermine regional peace and security, Article 28H of the Malabo Protocol draws on the 1977 Convention for the Elimination of Mercenarism in Africa.Footnote 69 Concluded under the auspices of the Organization of African Unity, the predecessor to the AU, the convention sought to prohibit the recruitment, training, using, and financing of mercenaries and mercenary activity as well as the active participation of a mercenary in an armed conflict or ‘in a concerted act of violence’ aimed at ‘overthrowing a legitimate government or otherwise undermining the constitutional order of a state’; ‘assisting a government to maintain power’ or ‘a group of persons to obtain power’; or ‘undermining the territorial integrity of a state’. This crime, which is a form of extension of the crime of aggression,Footnote 70 is significant. Historically, the presence of all kinds of mercenaries in African wars has been significant from before during the period of colonization and since then. It was a kind of activity that was used to undermine the human rights and self-determination claims by African peoples against their colonial masters.

Second, I will refer to piracy, which many scholars would consider the oldest international crime. Be that as it may, since we do not need to resolve that debate here, Article 28F of the Malabo Protocol adopts the definition of the crime of piracy as can be found in Article 101 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982. The offence was added to the Malabo Protocol to address the problem of piracy, which has become a major topic of concern for African states and indeed the international community as represented by the United Nations. As was argued by the drafters, ‘[t]his old crime has acquired a renewed importance in Africa, especially because piracy off the East and West African Coasts has lately become a serious concern in terms of law and order, peace, security and stability, and commerce and economic development.’Footnote 71

In this regard, again using Bassiouni’s five part criteria, it can readily be shown that some of these crimes address prohibited conduct affecting a significant international or regional interest because those offences are presumed to generate a threat to regional or international peace and security. This, for instance, was the case with respect to piracy and mercenarism. The commission of these offences undermine peace and security in the Africa region. Some of the other crimes entail prohibited conduct which is so egregious as to shock the conscience of Africans. They may be deemed offensive to the commonly shared values of the African community. This can also be said to be the case, in an admittedly more dubious argument, with respect to money laundering as an economic crime, but perhaps less so trafficking in persons, drugs and the illegal dumping of harmful hazardous wastes, as well as crimes like illicit exploitation of the natural resources of entire societies. Of course, all the prohibited conduct captured by these crimes may have transnational implications in terms of involving or affecting more than one African (or even non-African) State in their planning, preparation, or commission, either through the diversity of nationality of its perpetrators or victims, or the fact that the means employed towards their accomplishment transcend national borders. In some of these crimes, the criminalized conduct is harmful to either or both internationally and regionally protected interests.

Most if not all of these crimes also reflect one or more of Bassiouni’s ten penal characteristics. They implicitly or explicitly recognize the proscribed conduct as crimes under international conventional or customary law (e.g. piracy) and implicitly recognize the penal nature of the acts by establishing a legal duty in regional conventions to take steps to recognize the need for criminalisation of the prohibited conduct (e.g. corruption). In a handful of the cases, they establish that African States bear duties, or at least enjoy rights, to investigate and or prosecute those suspects who commit them (unconstitutional change of government). They also provide a framework for the establishment of a regional criminal jurisdiction to address them (i.e. illicit exploitation of natural resources).

3. The Partly International Crimes in the Malabo Protocol

Following Bassiouni’s classification, two crimes (terrorism and the crime of unconstitutional change of government) have been included in a third category in the earlier table. However, like piracy, some might credibly argue that the former offence belongs to the international crimes basket. The character of terrorism, which may include transborder dimensions in both preparation and commission, also means that it is a crime that could easily be added to the partly or fully transnational offence basket. This goes to show that the categories are not necessarily watertight. It further demonstrates that they may in fact be permeable. On a broader level, this permeability may raise doubts about the formal categories more generally. Nonetheless, the goal here is not to resolve doctrinal issues that might arise in respect of them as much as it is to offer a preliminary basis through which to think about the classification of the diversity of crimes contained in the African regional treaty.

As a technical matter, the Malabo Protocol adopts the definition of terrorism provided for in Article 3 of the Organization of African Unity Convention on Prevention and Combatting of Terrorism, with minor modifications.Footnote 72 Article 28G of the Protocol criminalises the promotion, sponsoring, contribution to, commanding, aiding, incitement, encouragement, attempting, threatening, conspiring, organizing, or procurement of any person, with the intent to commit an act of terrorism. An act of terrorism is defined as:

[a]ny act which is a violation of the criminal laws of a State Party, the laws of the African Union or a regional economic community recognized by the African Union, or by international law, and which may endanger the life, physical integrity or freedom of, or cause serious injury or death to, any person, any number or group of persons or causes or may cause damage to public or private property, natural resources, environmental or cultural heritage (emphasis added).

To constitute a crime, the prohibited conduct or acts must be calculated or intended to intimidate, put in fear, force, coerce, or induce any government, body, institution, the general public, or any segment thereof, to do or abstain from doing any act, or to adopt or abandon a particular standpoint, or to act according to certain principles. With respect to the acts of terrorism, it is unclear why the Malabo Protocol does not include the acts criminalised, perhaps as a starting point, by several UN Conventions and to which the obligation to prosecute or extradite (aut dedere aut judicare) applies. Despite the lack of a universally acceptable definition of terrorism, there appears to be consensus that the conduct criminalized by the 12 UN Conventions constitutes international crimes.Footnote 73

The crime of unconstitutional change of government is one of the new crimes created by the Malabo Protocol. Article 28E, criminalises commission or ordering, ‘with the aim of illegally accessing or maintaining power’, several acts including carrying out a coup against a democratically elected government. Of all the crimes included in the instrument, the crime of unconstitutional change of government is perhaps one of the most important public order crimes for Africa given the history of coup d’états on the continent. It is also a key public order crime, the prohibition of which has been perhaps the most controversial. It also elicited heated debates on a wide range of issues in relevant AU organs during the drafting process.Footnote 74 The drafters of the Malabo Protocol argued that:

This elaborate definition continues the trend of the AU, over the last dozen years, of appreciating that unconstitutional change of government could be sudden, forceful or violent (as in coup d’état or mercenary attacks) or could be more silent, insidious and long-drawn out (as, for example, a democratically elected government which, once in office, systematically dismantles democratic laws, principles and institutions in order to prolong its hold to power).

It is the recognition of the problematic nature of a leader illegally hanging on to power that led to a regional prohibition. Essentially, Article 25 of the African Charter on Elections, Democracy and Good Governance provided, in addition to various sanctions against the offending state, that ‘perpetrators of unconstitutional change of government may also be tried before the competent court of the Union’.Footnote 75 Thus, without previously having criminalized this offense at the regional court level, the Malabo Protocol gives African states the possibility of taking enforcement action in a regional penal tribunal against a person who violates regional norms where he refuses to peacefully transfer power to a winning candidate following free and fair elections.

Recent developments help illustrate the significance of the prohibition. For example, following contested election results in The Gambia in 2016, the AU reminded President Yahya Jammeh that he would have violated regional law if he failed to relinquish power.Footnote 76 The AU stated that the refusal to peacefully transfer power thwarted the will of the people. The regional organisation feared that this would lead to instability in not just the country where the president refused to step down, but that it would also undermine the peace and security of the entire Africa region. In the end, though there were some legal questions about the implications of such regional actions for regime change and African State practice on the jus ad bellum since Gambia was not even a party to the African Charter on Democracy and Governance, only a signatory (though it has accepted the principle of democratic governance under the Constitutive Act of the African Union), the Jammeh Government did proceed to peacefully relinquish power. Part of the reason was no doubt because of pressure from outside, but also the willingness of African States to put boots on the ground to enforce their collective decision. Although this outcome might have been made possible because of the threat of the use of force, from Senegal acting with the imprimatur of Addis Ababa and New York, the winner of the election, Adama Barrow, was subsequently successfully sworn in.

To sum up, using both Bassiouni’s five part criteria and his ten penal characteristics, it can readily be demonstrated that the crimes of terrorism and unconstitutional changes of government can also be explained as regional level offenses because of the harms that they cause and the regional interests that they seek to protect.

4. The Partly Transnational Crimes in the Malabo Protocol

The crime of corruption has here been placed in the partly transnational crimes category. Obviously, this crime can be committed wholly in violation of domestic law and without any transnational or trans-border effects. Nonetheless, given the history of kleptocracy on the part of some African leaders, it was recognized that perpetrators can do more damage to a society by draining it of its resources essential for basic needs of the community. This frequently has a transnational dimension. In some cases, it intersects with other crimes such as money laundering. It is for that reason it was included in the Malabo Protocol to address a matter that has been of both international and regional concern, as the conclusion of several conventions in that regard demonstrates. Again, the categories are not impermeable and others may well legitimately place this crime (i.e. corruption) in the fully transnational crimes or even international crimes category given the existence of a global convention on the same subject.

Corruption as a transnational crime appears to be somewhat ill-defined and could elicit legality challenges (though there is a widely accepted UN convention on the topic). At the regional level, Article 28I of the Malabo Protocol basically replicates, with some modifications, the African Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption.Footnote 77 The chapeau suggests that the African Criminal Court will be limited to prosecuting only those acts ‘of a serious nature affecting the stability of a state, region or the [African] Union’.Footnote 78 This qualifier, which we do not see replicated for the other crimes in the instrument under discussion, offers a formal gravity threshold by removing from the ambit of the regional tribunal ‘petty corruption’ for the sake of addressing what is often referred to as ‘grand corruption’. The latter is usually committed by leaders and high-level persons holding high public office, such as presidents, vice presidents, or sitting government ministers, all of whom are in a different part of the Malabo Protocol guaranteed some type of temporary immunity from prosecution during their time in office.Footnote 79 On this view, it would seem that low level corrupt activity that occurs within a State will not attract the interest of the regional court, presumably because such offences could be more readily prosecuted within the national courts, and in countries that have them, they may even be pursued by national anti-corruption commissions.

Perhaps of greater concern is the lack of clarity as to the meaning of ‘stability’ – whether it is economic, political or social. If ‘stability’ is economic, and corruption is considered an economic crime, it is arguable that while embezzlement of say one million dollars could threaten the (economic) stability of one state, it might not be the case for a richer state, not least a region. In the same vein, the threshold ‘of a serious nature affecting the stability of a state, region or the Union’Footnote 80 appears to be too high. Should a monetary value be attached to such a threshold? If that is the case, is it appropriate in view of differentials in the GDPs of African countries, if that is the measure adopted? How is impact of a corrupt activity to be measured?

It is arguable that, with the extensive list of fourteen crimes within its material jurisdiction, the risk is that the future African Criminal Court will be overburdened. This argument carries weight, if the experience of the international criminal tribunals that have preceded it are anything to go by. It is also not entirely clear what parameters, if any, were contemplated to regulate the relationship between the national courts in states parties to the Malabo Protocol and the African Court which will likely sit in Arusha, Tanzania. Indeed, it can be argued that given the work of the international criminal tribunals and the high costs associated with investigating and prosecuting such crimes, away from the locus criminis, the regional court would likely have benefited from a clarification that its mandate is to focus on the particularly serious international or transnational crimes within its jurisdiction. The Protocol suggested inclusion of only serious crimes of international or regional concern within the jurisdiction of the court. But, in terms of the particular definitions, the same instrument did not delineate formal limits in a systematic way. It did so only in respect of corruption, which was classified as serious and less serious, leaving the rest of the 13 crimes to the wide discretion of the prosecutor.

In the Rome Statute, the jurisdiction of the Court was narrowly crafted in such a way to limit to the ‘most serious crimes’Footnote 81 of concern to the international community as a whole. The use of the terminology of ‘grave crimes’ in the preamble suggests some criteria to delimit the scope of the Court’s jurisdiction. This is not to say that they were not serious crimes, such as terrorism, which could have also been included. Though it is said that there is no formal hierarchy of crimes in the Rome Statute, we all know that some of the crimes are considered as more egregious than others. In this regard, some scholars see the four core crimes in the treaty as establishing some type of ‘quasi-constitutional threshold’Footnote 82 for the addition of new crimes. In addition, it was clear from the experience of the ad hoc tribunals that preceded it during the 1998 negotiations and the policies of the Office of the Prosecutor since then, that the ICC would have to focus on those bearing ‘greatest responsibility,’Footnote 83 which can be understood as an additional limitation to those holding leadership or authority positions. That also limits the possible reach of the court and helps to ensure that it is not overwhelmed with cases, especially given its wide potential jurisdiction in over 123 States Parties.

4. Concluding Remarks

This chapter has tried to show that traditional international criminal law and transnational criminal law literature remains confused as to the proper basis to distinguish between ‘international crimes’ and ‘transnational crimes’, and for that matter, international criminal law and transnational criminal law. Indeed, as there has historically been limited guidance as to what criteria – if any – states use to determine which crimes to include in international instruments as they negotiate relevant treaty crimes, there is only a limited academic literature attempting to systematically clarify the boundaries between these concepts. One helpful distinction that appears settled is that between crimes under international criminal law, which establish direct penal liability for persons, on the one hand, and those under suppression conventions that instead obligate states to take measures to prohibit as criminal various types of conduct under their domestic law, on the other.

In the absence of clarity in international processes as to what policies should guide criminalization of offences suitable for collective action by States, as opposed to those suitable for each of them acting separately, this contribution has drawn on the spare literature focusing in particular on Bassiouni’s proposed criteria to explore the implications of this state of affairs in what might initially appear like the hodgepodge of crimes contained in the African region’s Malabo Protocol. I have shown that, using the policy criteria and penal characteristics identified by that prominent African author as a starting point, it is not entirely surprising that African States reflect some of the same confusion in their determinations as to what prohibitions should be criminal conduct at the regional level for the future African Criminal Court. Much like how various theories can be used to explain the international prohibition of certain offenses at the international level, and the ad hoc nature in which criminalisation occurred historically, the African court instrument also reflects various regional interests being prioritized for regional over national or international enforcement action. This implies the need for greater clarity, in the future, to be set forth by national authorities as to what doctrinal frameworks drive the adoption of certain crimes for addition to the statutes of future international and regional penal tribunals. Only in this way might we start to develop a more coherent international or regional legal regime that accounts for all the harms and community interests for which prohibition is being sought.

If nothing else, though not yet in force and unlikely to be for a few more years, the arrival of the Malabo Protocol on the international legal scene has posed a serious challenge for international lawyers to explain the objective phenomenon that we might have previously taken for granted in regards to the categories of transnational and international crimes. Considering that it was a proposal by Trinidad and Tobago regarding drug trafficking that reopened the global discussion and led concretely to the final establishment of the long-awaited permanent ICC, and the fact that some states continue to advocate for addition of new ‘transnational’ crimes like terrorism to the Rome Statute, it could be that the African State practice will in the future help show the way forward towards a richer and more nuanced conception of what we consider modern ‘international criminal law’. An international criminal law that would hopefully be more responsive to the needs of developing states in terms of addressing not only individual crimes, but also the web of economic crimes and other related public order offenses that together give rise to instability and give succour to what has aptly been described as ‘system criminality’Footnote 84 in international law. A criminality that, to date, has only been tackled in piecemeal fashion, in two separate silos, that is probably better considered together.

1. Introduction

The Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (2014) (as it is formally known) (‘Malabo Protocol (2014)’) could be said to represent many things, depending on one’s perspective. For some, it is a genuine attempt by African States to address international and transnational crimes that bedevil the African continent.Footnote 1 For others, it is a cynical response to decisions of the International Criminal Court (ICC) that African leaders do not like, and the so-called ‘abuse’ of universal jurisdiction by Western states for crimes committed on the African continent.Footnote 2 The aim of this chapter, however, is to simply offer objective perspectives on the provisions of the Malabo Protocol (2014) that add international criminal jurisdiction to the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (ACJHR), particularly those relating to genocide (Article 28B), war crimes (Article 28D), crimes against humanity (Article 28C) and aggression (Article 28M).

At the outset, one often forgotten matter should be recalled. The Malabo Protocol (2014) as a whole was the result of debates and negotiations between African States which manifested themselves in specific language, omissions and compromises. As with all treaties, one cannot expect a perfect outcome – it is hard, if not impossible, to please all interested parties. As a result, some of the ideas reflected in the Malabo Protocol (2014) are very innovative, salutary and make a positive contribution to the development of international criminal law. Other ideas may be unrealistic. Others are outright retrogressive and undesirable. But as it relates to core international crimes alone, the Malabo Protocol (2014), as detailed below, brings much good to the international criminal law table.

2. A Most Convoluted Architecture: The Interaction of at Least Four Different Treaty Regimes

Before delving into the substantive crimes under the Malabo Protocol (2014), one issue cannot escape attention. That is the convoluted and complex legal architecture of the ACJHR as envisaged by the Malabo Protocol (2014). As the inclusion of the word ‘protocol’ in its name suggests, the Malabo Protocol (2014) is not a treaty that stands on its own. Rather, it is the last of at least 4 different treaty regimes that endeavour to work and interact together to create – among other things – Africa’s regional court for international crimes.

The first of these is the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1998) (African Human Rights Court Protocol). This established the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights – the African equivalent of the European Court of Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Its mandate is to guard against violations of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1981) – Africa’s regional human rights treaty. It hears and adjudicates on complaints from the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, States parties, African intergovernmental organizations, non-governmental organizations and individuals; it may also render advisory opinions at the request of African Union (AU) member states.Footnote 3 The African Human Rights Court Protocol entered into force (and the court was established) on 25 January 2004, 30 days after the 15th AU state (Comoros) deposited its instrument of ratification.Footnote 4 As of 15 June 2017, 52 of the AU’s 55 member states have signed the African Human Rights Court Protocol (1998), while 30 member states have ratified or acceded to it.Footnote 5 The first set of judges were sworn in 2006 and the court is currently up and running and actively fulfilling its mandate.

The second relevant treaty is the Protocol of the Court of Justice of the African Union (2003) (African Court of Justice Protocol). This established an entirely different court, the African Court of Justice – the African equivalent of the International Court of Justice and the European Court of Justice. The court was originally envisaged by the Constitutive Act of the African Union (2000) (AU Constitutive Act), but its statute, composition and functions were left to be finalized in a separate protocol at a later time.Footnote 6 The African Court of Justice’s jurisdiction extends to the interpretation and application of the AU Constitutive Act (2000), AU treaties and subsidiary legal instruments (including regulations and directives), as well as any question of international law and all matters where states parties specifically agree to confer jurisdiction upon it.Footnote 7 As of 15 June 2017, 44 of the AU’s 55 member states have signed the African Court of Justice Protocol (2003), while 18 member states have ratified or acceded to it.Footnote 8 It entered into force on 11 February 2009, 30 days after the 15th AU state (Algeria) deposited its instrument of ratification.Footnote 9 However, unlike the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the African Court of Justice exits only on paper. The Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the AU determined in 2004 that the African Court of Justice should be merged with the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, but without prejudice to the operationalization and continued existence of the latter.Footnote 10

This merger brings us to the third relevant treaty: the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (2008) (African Court of Justice and Human Rights Protocol). This treaty envisages a new court – the ACJHR – which, as aforementioned, would combine the functions and mandates of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the African Court of Justice. As of 8 February 2018, 31 of the AU’s 55 member states have signed the African Court of Justice and Human Rights Protocol (2008), while only 6 member states have ratified or acceded to it.Footnote 11 15 AU member states are needed to ratify (or accede to) the African Court of Justice and Human Rights Protocol (2008) before it enters into force,Footnote 12 and thus the protocol – and the ACJHR – remains only on paper for the time being.

To the ACJHR, the AU has added a fourth treaty layer: the Malabo Protocol (2014). This protocol, which is the focus of this chapter, adds international and transnational crimes to the jurisdiction of the proposed ACJHR, as well as procedural and other provisions to facilitate their investigation and prosecution. 15 AU member states must ratify (or accede to) the Malabo Protocol (2014) before it can enter into force.Footnote 13 As of 8 February 2018, only 11 of the AU’s 55 member states have signed the Malabo Protocol (2014), and no member state has ratified or acceded to it.Footnote 14