Introduction

‘Digital poverty reduction refers to efforts, approaches, strategies, and solutions aimed at reducing poverty (e.g., a region or country) through the application of digital technologies and digital inclusion initiatives and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies’ (Si, Hall, & Wei, Reference Si, Hall and Wei2024). Alongside this definition, digital poverty alleviation has received significant attention from academic research (e.g., Ng, Lim, Lye, Chan, & Lim, Reference Ng, Lim, Lye, Chan and Lim2025; Pei, Zhang, & Zhou, Reference Pei, Zhang and Zhou2024). In this regard, the role of digital finance has been highlighted as it facilitates access to digital financial services on mobile phones and digital financial platforms (Adu & Hartarska, Reference Adu and Hartarska2025; Islam, Ornob, & Hossain, Reference Islam, Ornob and Hossain2025). Consequently, digital finance is regarded as an efficient and transformative force in poverty alleviation (Dorfleitner, Forcella, & Nguyen, Reference Dorfleitner, Forcella and Nguyen2022). Meanwhile, various studies, such as Abdallah Ali, Mughal, and Chhorn (Reference Abdallah Ali, Mughal and Chhorn2022), Cooke and Amuakwa-Mensah (Reference Cooke and Amuakwa-Mensah2022), Gupta and Sharma (Reference Gupta and Sharma2023), and Hasan, Singh, Agarwal, and Kushwaha (Reference Hasan, Singh, Agarwal and Kushwaha2025), demonstrated microfinance’s effectiveness in reducing poverty. In this regard, the adoption of digital technologies has increased the efficiency of microfinance by optimizing transaction costs and improving financial transparency (Offiong, Szopik-Depczyńska, Cheba, & Ioppolo, Reference Offiong, Szopik-Depczyńska, Cheba and Ioppolo2024), thereby helping to alleviate poverty. In the same vein, digital financial knowledge can enhance microfinance effectiveness through the provision of access to digital financial applications (Liu, Wang, Sindakis, & Showkat, Reference Liu, Wang, Sindakis and Showkat2024). Therefore, digital financial knowledge is essential for effective financial management of microfinance clients (Abdallah, Tfaily, & Harraf, Reference Abdallah, Tfaily and Harraf2025; Bhat, Lone, SivaKumar, & Krishna, Reference Bhat, Lone, SivaKumar and Krishna2025; Kandie & Islam, Reference Kandie and Islam2022).

Motivated by the importance of both digital technologies and microfinance in alleviating poverty, this study examines whether enhancing the level of digital financial knowledge of microfinance clients could positively influence the link between microfinance effectiveness and poverty alleviation. For that, we consider both digital and traditional financial knowledge, as well as social capital, to be potential moderating factors of this relationship. From our knowledge, this threefold moderation effect has not been considered in previous studies investigating the role of microfinance in alleviating poverty. Furthermore, this research leans on a sample of 500 microfinance clients from Bhakkar, the most dynamic microfinance district in Pakistan’s Punjab province. In addition, its findings can provide critical insights into the role of microfinance in emerging Asian countries such as China. In this study, Pakistan was chosen because it still has a very high proportion of people living in poverty (37.2%, World Bank, 2023).

Empirical results obtained using the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach demonstrate a positive connection between microfinance effectiveness and poverty alleviation. Notably, digital and traditional financial knowledge have a positive moderating effect on this relationship. The same result is found with social capital when traditional financial knowledge is included in the model. However, this is not the case when it comes to digital financial knowledge. This finding raises questions about the potential detrimental effect of digital development on the social capital of microfinance clients. Therefore, to optimize microfinance’s positive effect on poverty reduction, it is crucial to foster both traditional and digital financial knowledge, while also recognizing the importance of fostering social connections of microfinance clients. Based on these results, we recommend that microfinance institutions and governments educate microfinance clients further in both financial and digital basics. We also recommend that microfinance clients embark on a continuous learning journey to better use the funds provided by microfinance institutions. Furthermore, traditional financial knowledge can enable microfinance clients’ social connections to positively contribute to poverty alleviation. However, it is not the case with digital financial knowledge. This finding leads us to call for future research to delve deeper into the interaction between digital development and social capital to better understand its influence on the link between microfinance effectiveness and poverty alleviation.

These findings can inspire future studies into the impact of microfinance in other emerging nations, such as China, where significant differences need to be considered. First, China’s level of digital financial knowledge far exceeds that of Pakistan. For example, 38% of the population in China use credit cards, while the one in Pakistan is 0.22% (The Global Economy). Furthermore, the average income level is another difference between the two countries: $3041 per month in China, compared to $293 per month in Pakistan (World Bank, 2025). In addition, according to Fouillet and Pairault (Reference Fouillet and Pairault2010), microfinance in China is closely linked to the government. Conversely, microfinance in Pakistan is more closely associated with local and regional management. Given these differences, the questionnaire used in this study would need to be adapted for the Chinese context to effectively evaluate constructs such as digital and traditional financial knowledge, social capital, and microfinance effectiveness.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

Although most studies investigating the ability of digital technology in reducing poverty have found positive effects, academic literature on this topic is mixed. On the positive side, Lechman and Popowska (Reference Lechman and Popowska2022) demonstrated that information technology (IT) can improve educational attainment and living standards in developing nations. Similarly, Lee, Lou, and Wang (Reference Lee, Lou and Wang2023) showed that digital financial inclusion is an important factor in alleviating poverty in China. Furthermore, Tao, Wang, Li, and Wei (Reference Tao, Wang, Li and Wei2023) showed that inclusive digital finance in China can reduce households’ credit constraints, increase investment in risky assets and entrepreneurship, and decrease relative poverty. Meanwhile, Xu (Reference Xu2024) demonstrated that digital finance reduces the rural-urban income gap, which is consistent with the research of Wang, Wang, Zhou, Chen, and Mao (Reference Wang, Wang, Zhou, Chen and Mao2025) on industrial digitalization and the study of Wang, Qu, and Yin (Reference Wang, Qu and Yin2025) on digital literacy. Similarly, Zhou, Zha, Qiu, and Zhang (Reference Zhou, Zha, Qiu and Zhang2024) demonstrated that digital literacy decreases the likelihood of re-experiencing poverty. Additionally, Hariyani, Hariyani, and Mishra (Reference Hariyani, Hariyani and Mishra2025) showed that digital technology facilitates the achievement of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Furthermore, Javed, Ashraf, and Shahbaz (Reference Javed, Ashraf and Shahbaz2025) showed that digital technologies can help Pakistani women develop their skills and achieve financial inclusion. In addition, Li and Huang (Reference Li and Huang2025) found that digital literacy moderates the ability of social security coverage to alleviate relative poverty in a positive way.

In contrast, Dzator, Acheampong, Appiah-Otoo, and Dzator (Reference Dzator, Acheampong, Appiah-Otoo and Dzator2023) found that IT development increases the poverty rate, regardless of the population age. According to Wu (Reference Wu2024), one reason for the negative influence of IT is the digital divide, or digital inequality. Crucially, they showed that social security coverage can mitigate the negative effect of the digital divide. This result supports the moderating effect of social capital considered in this research. Similarly, Zeng, Yang, Wang, and Zou (Reference Zeng, Yang, Wang and Zou2025) showed that digital exclusion increases the level of relative poverty. However, the magnitude of this negative effect depends on household characteristics, while education has a positive moderating effect. In a European context, Antonietti, Burlina, and Rodriguez-Pose (Reference Antonietti, Burlina and Rodriguez-Pose2025) demonstrated that greater access to digital technology exacerbates income inequality. Nevertheless, stronger institutions can mitigate this negative impact.

In summary, recent research has largely demonstrated the positive influence of digital technologies in alleviating poverty. However, it is important to consider the potential negative impact of digital divide, as well as the various channels through which digital technologies operate, such as the internet and mobile phones. These findings support our study, confirming the significance of including digital financial knowledge as a moderating variable in the link between microfinance and poverty reduction.

Regarding microfinance, its relationship with poverty alleviation leans on three theories: vulnerable group theory (Ozili, Reference Ozili2024), social capital theory (Bourdieu & Richardson, Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986), and financial literacy theory (Ozili, Reference Ozili, Al-Sartawi and Ghura2025). Vulnerable group theory stipulates that financial inclusion leads to the economic empowerment of microfinance clients. Furthermore, this theory emphasizes the importance of financial education (Choudhary & Jain, Reference Choudhary and Jain2023), justifying the consideration of both financial knowledge and digital financial knowledge in our empirical analyses. Additionally, microfinance institutions can contribute significantly to leveraging social capital by promoting community-based lending schemes (Bongomin, Munene, Ntayi, & Malinga, Reference Bongomin, Munene, Ntayi and Malinga2018). Thus, social capital theory provides a theoretical justification for the consideration of social networks and trust in improving the effectiveness of microfinance. Indeed, individuals with strong social capital have better access to financial resources, leading to poverty reduction (Ogbari et al., Reference Ogbari, Folorunso, Simon-Ilogho, Adebayo, Olanrewaju, Efegbudu and Omoregbe2024; Zhang & Zhao, Reference Zhang and Zhao2024). In addition, financial literacy theory stipulates that financial knowledge empowers microfinance clients to make better financial decisions, thereby amplifying microfinance’s positive impact on poverty alleviation (Lontchi, Yang, & Su, Reference Lontchi, Yang and Su2022; Prayitno, Sahid, & Hussin, Reference Prayitno, Sahid and Hussin2022). This research therefore extends this theory by also considering digital financial knowledge.

Much of the research on microfinance is based on this theoretical foundation and has demonstrated its positive relationship with poverty alleviation. This is because microfinance fosters entrepreneurship and creates income-generating opportunities, thereby reducing poverty levels (Farooq, Din, Soomro, & Riviezzo, Reference Farooq, Din, Soomro and Riviezzo2024). In this regard, providing financial services to the poor helps improve their investment skills while encouraging new business initiatives (Qamar, Masood, & Nasir, Reference Qamar, Masood and Nasir2017; Tasos, Amjad, Awan, & Waqas, Reference Tasos, Amjad, Awan and Waqas2020; Van Rooyen, Stewart, & De Wet, Reference Van Rooyen, Stewart and De Wet2012). Furthermore, Garcia, Lensink, and Voors (Reference Garcia, Lensink and Voors2020) identified a positive connection between microcredit, hope, and economic wellbeing. Furthermore, Begum, Alam, Mia, Bhuiyan, and Ghani (Reference Begum, Alam, Mia, Bhuiyan and Ghani2018) found that Islamic microfinance is a more ethical approach for poverty reduction as it provides clients experiencing difficulties with a longer period to repay their loans.

In contrast, previous research also showed that microfinance is not always an efficient tool in reducing poverty. For instance, Banerjee, Duflo, Glennerster, and Kinnan (Reference Banerjee, Duflo, Glennerster and Kinnan2015) demonstrated that microfinance has an insignificant impact on clients’ spending habits, educational attainment or the decision-making abilities of women. Furthermore, microfinance services can also lead to increased daily expenditure, causing clients to become indebted and trapped in a cycle of poverty (Banerjee & Jackson, Reference Banerjee and Jackson2017; Nawaz, Reference Nawaz2010). Similarly, Donou-Adonsu and Sylwester (Reference Donou-Adonsou and Sylwester2016) demonstrated that, unlike traditional banks, microfinance institutions do not help reduce poverty. In the Philippines, Agbola, Acupan, and Mahmood (Reference Agbola, Acupan and Mahmood2017) found that microfinance only had a limited impact on poverty reduction. In addition, Zainal, Nassir, Kamarudin, and Law (Reference Zainal, Nassir, Kamarudin and Law2020) showed that microfinance institutions encounter mission drift and are therefore inefficient at reducing poverty in ASEAN-5 countries.

Overall, previous research shows that digital technologies and microfinance can effectively alleviate poverty. However, if their potential side effects are not considered, such as the digital divide and high levels of microcredit-related debt, they can also exacerbate poverty. Against this backdrop, our central research question is whether digital financial knowledge can influence the link between microfinance effectiveness and poverty reduction by acting as a moderator. There are three reasons for investigating this research hypothesis. Firstly, understanding the moderating role of digital financial knowledge can help explain the dual role, positive and negative, of digital technologies on poverty reduction. Secondly, microfinance and digital technologies are known as efficient tools for reducing poverty. However, to our knowledge, the moderating role of digital financial knowledge has not yet been adequately explored in previous research (e.g., Mushtaq & Bruneau, Reference Mushtaq and Bruneau2019). Thirdly, given the importance of microfinance and digital technology development in Pakistan, this research question is particularly relevant. Therefore, the main research hypothesis is as follows.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Digital financial knowledge has a positive moderating effect on the effectiveness of microfinance in alleviating poverty.

The arguments for the positive moderating influence of digital financial knowledge are as follows. Firstly, previous empirical evidence suggests that financial knowledge is important for microfinance clients to optimize the use of microcredit. In this regard, financial literacy theory (Ozili, Reference Ozili, Al-Sartawi and Ghura2025) posits that financial knowledge is a key driver of financial inclusion. Therefore, it is important to extend this theory to further consider the importance of digital financial knowledge. Secondly, individuals with greater digital financial knowledge are more likely to engage with microfinance institutions because they can use microcredits more efficiently (Hasan, Le, & Hoque, Reference Hasan, Le and Hoque2021). Thirdly, digital financial knowledge improves the effectiveness of microfinance by facilitating the use of digital financial products, leading to poverty alleviation (Abdallah et al., Reference Abdallah, Tfaily and Harraf2025; Bhat et al., Reference Bhat, Lone, SivaKumar and Krishna2025; Kandie & Islam, Reference Kandie and Islam2022; Liu, Wang, Sindakis, & Showkat, Reference Liu, Wang, Sindakis and Showkat2024). Therefore, combining microfinance with digital financial knowledge enhances financial inclusion and reduces poverty (Bongomin, Malinga, Amani, & Balinda, Reference Bongomin, Malinga, Amani and Balinda2025; Koskelainen, Kalmi, Scornavacca, & Vartiainen, Reference Koskelainen, Kalmi, Scornavacca and Vartiainen2023; Teslenko & Maslakova, Reference Teslenko and Maslakova2024), leading to the main research hypothesis of this study.

To specifically measure digital financial knowledge in Pakistan, we consider two dimensionsFootnote 1 which are the knowledge about credit card and the understanding of timely bills payment. Indeed, using credit cards encourages the use of e-commerce and other digital services. In this regard, previous studies indicated that knowledge of credit cards is an important component of digital financial knowledge (Abdallah et al., Reference Abdallah, Tfaily and Harraf2025; Antonietti et al., Reference Antonietti, Burlina and Rodriguez-Pose2025; Chhillar, Arora, & Chawla, Reference Chhillar, Arora and Chawla2024; Shehadeh, Dawood, & Hussainey, Reference Shehadeh, Dawood and Hussainey2024; Vieira, Matheis, Lehnhart, & Tavares, Reference Vieira, Matheis, Lehnhart and Tavares2024). Interestingly, Osuma, Nzimande, and Simon-Ilogho (Reference Osuma, Nzimande and Simon-Ilogho2025) found that using ATMs (Automated Teller Machines) can reduce poverty and improve a country’s GDP. In the context of our data sample of microfinance clients in Pakistan, knowledge of credit cards is an important indicator of digital financial knowledge given that only 0.22% of the population has a credit card (The Global Economy, 2021). Regarding the importance of timely bills payment, Vieira et al. (Reference Vieira, Matheis and Lehnhart2024) concluded that bill payments through digital tools is one of the measurement items of digital financial capability, aligning with the finding of Widyastuti, Respati, Dewi, and Soma (Reference Widyastuti, Respati, Dewi and Soma2024). Therefore, understanding the importance of timely bills payment can participate in the development of digital financial knowledge of microfinance clients in the data sample of this study (more details about the measurement of these two items are presented in third section).

Methods

This research leans on primary data collected from 500 microfinance clients in a district of the Punjab province in Pakistan between December 2021 and June 2022. The participants’ responses to the survey were used to measure the five main constructs to be considered in the analysis. Further, empirical analysis has been carried using structural equation modeling (SEM) on cross-sectional data.

Sample

This study employed the snowball sampling technique to identify elusive populations while minimizing data collection costs (Biernacki & Waldorf, Reference Biernacki and Waldorf1981). It is based on chain referrals, whereby active participants help identify other participants (Sudman, Reference Sudman1976). Specifically, our data collection process began with a small number of microfinance clients, who then referred us to other microfinance clients. Employees of related microfinance institutions also referred us to other microfinance clients, enabling us to reach a broader audience and achieve greater diversity in the sample. With this method, the final sample comprised 500 completed questionnaires of microfinance clients, 250 of which were from Islamic microfinance institutions and 250 from conventional microfinance institutions.Footnote 2

The questionnaire used in this study can be found in Appendix I. When developing the questionnaire, we considered previous research related to each construct considered. Specifically, Kumari’s (Reference Kumari2021) work informed the measurement of microfinance effectiveness and inspired the poverty alleviation questions. The work of Perry and Morris (Reference Perry and Morris2005) informed the measurement of digital and traditional financial knowledge (DFK and FK). Additionally, Chen, Stanton, Gong, Fang, and Li’s (Reference Chen, Stanton, Gong, Fang and Li2009) work helped us identify how to measure social capital. Furthermore, all the items included in the questionnaire are directly related to our research objective. For instance, we only included items from Kumari’s (Reference Kumari2021) study that were related to microfinance effectiveness.

Five constructs were then calculated using items collected from the survey (see Table 1). The Microfinance Effectiveness (ME) construct comprises four items, which are measured using a five-point Likert scale spreading from ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree’ (see Appendix I for full details). Similarly, the Poverty Alleviation (PA) construct consists of six items. The Digital Financial Knowledge (DFK) construct comprises two items, while the Traditional Financial Knowledge (TFK) construct comprises five items. Finally, the social capital construct consists of five items. Table 1 shows the items used to develop the five constructs.

Table 1. Constructs with measuring items

To measure Digital Financial Knowledge (DFK), we examined participants’ responses to two specific questions: one concerning credit cards and the other concerning the importance of timely bill payment. As discussed above, credit cards play a key role in digital financial knowledge because they are widely used on digital platforms. Therefore, knowing how to use them is essential in digital financial literacy. For microfinance clients without access to credit systems, understanding credit cards and their associated costs is important for personal financial management (Atkinson & Messy, Reference Atkinson and Messy2012). In the same vein, understanding the importance of timely bill payment is essential for personal financial management in the context of rapid digital technology development. As bill payments are now commonly made through digital tools, being aware of when they are due can prevent microfinance clients from digital penalties (Chhillar et al., Reference Chhillar, Arora and Chawla2024; Koskelainen et al., Reference Koskelainen, Kalmi, Scornavacca and Vartiainen2023; Vieira et al., Reference Vieira, Matheis and Lehnhart2024). Therefore, paying bills on time can demonstrate an efficient use of digital tools, which is directly related to personal financial stability (Ozili, Reference Ozili2018). Regarding microfinance clients in our research sample, most of them are novices when it comes to using mobile phones and digital banking. Therefore, this item allows us to measure their ability to interact with digital finance and to avoid financial losses (Seldal & Nyhus, Reference Seldal and Nyhus2022; Koskelainen et al., Reference Koskelainen, Kalmi, Scornavacca and Vartiainen2023; Lusardi, Reference Lusardi2019).

Table 2 presents the main descriptive statistics of the final sample of 500 participants and shows that 60.6% are male and 39.4% are female. Similarly, there are more young clients than older ones. Furthermore, most participants have an annual income lower than 25,000 Pakistani rupees (PKR), equivalent to around 90 USD per year. Moreover, most of the participants come from rural backgrounds and have an educational attainment level below matriculation. Finally, most participants are married (refer to Table 2 in Appendix I for more details on descriptive statistics of each survey item). In addition, Table 3 shows the correlation matrix for the variables under consideration. Panel 3A-1 relates to traditional financial knowledge, while Panel 3A-2 relates to digital financial knowledge. Overall, correlation coefficients are lower than 0.5, which prevents multicollinearity issues in the estimated model.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of participants

Note: The distribution of the main variables collected from the survey is shown in this table. Source: The authors.

Table 3. A: Correlation matrix. Panel 3A-1: With traditional financial knowledge. Panel 3A-2: With digital financial knowledge

** Note:means that the correlation is significant at the 0.01 level.

Variables

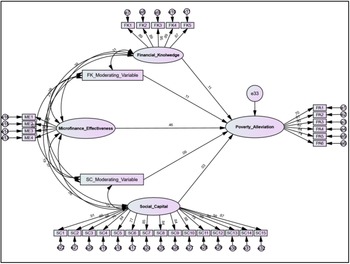

Table 4 defines the variables and their original references. Figure 1 shows how the five constructs under study are measured. To avoid issues of multicollinearity between Financial Knowledge and Digital Financial Knowledge, which have a correlation of 0.962, we construct two separate models. In the first one, only Digital Financial Knowledge (Figure 1) is included while in the second one, only Traditional Financial Knowledge is included (Figure 1A). To save space, the model with Traditional Financial Knowledge (Figure 1A) is presented in Appendix II. Regarding Figure 1, all the constructs are measured through items represented as ME1-ME4, PA1-PA6, DFK1-DFK2, and SC1-SC15, referring to microfinance effectiveness, poverty alleviation, digital financial knowledge, and social capital, respectively. The arrows from each construct to its respective items indicate the strength of their relationship, as measured by factor loadings. These factor loadings are obtained by conducting a structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) approach. Higher factor loadings indicate stronger associations between the considered constructs and their measurement items. The error terms, ‘e1’ to ‘e32’, show the measurement errors of the considered items. Figure 1 also shows the relationship among the constructs (the arrows on the left of the figure). This measurement model has been statistically validated, ensuring the reliability and validity of the constructs.

Figure 1. The constructs’ measurement model with digital financial knowledge

Table 4. Variables

Notes: This table shows the definition of the main variables used in the empirical analysis. ME1 to ME4 refer to the 4 survey items to measure microfinance effectiveness. The same is applied for PA, DFK, FK, and SC. See Table 1 and Appendix I for full details.

Table 5 presents the main descriptive statistics of the constructed variables. The average value of microfinance effectiveness (ME) is 3.8440, out of a maximum of 5. This indicates that participants generally recognize the benefits of microfinance. Similarly, the average of poverty alleviation (PA) of 3.7077 indicates that microfinance has effectively alleviated poverty among survey respondents. Furthermore, the average value of digital financial knowledge is 2.89, which shows that microfinance clients in the sample possess low digital financial knowledge. In addition, an average of social capital of 3.1559 indicates that participants have moderate social connections. Furthermore, the skewness and kurtosis values of the variables are less than 3 and 10, respectively, suggesting that they are not affected by heavy tails or asymmetry (Kline, Reference Kline2011). Additionally, the multicollinearity assessment (Table 6) revealed that the tolerance values for the considered constructs are greater than 0.1, while the values of VIF are lower than 10, indicating the absence of multicollinearity.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics of the constructs

Notes: This table shows the main descriptive statistics of the five variables. ME refers to Microfinance Effectiveness. PA refers to Poverty Alleviation. DFK refers to Digital Financial Knowledge. FK refers to Traditional Financial Knowledge. SC refers to Social Capital.

Table 6. Tolerance and variance inflation factor values

Note: Dependent variable = Poverty Alleviation.

Before conducting the SEM estimation, the measurement models need to be validated using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (Awang, Reference Awang2015). CFA is used to measure the reliability, validity, and one-dimensionality of the constructs (Awang, Reference Awang2015; Kline, Reference Kline2011).Footnote 3 As shown in Table 7, all the AVE values are between 0.55 and 0.77, which corresponds to the criterion of 0.5. Furthermore, all the Cronbach’s alpha values are above 0.5, confirming the satisfactory internal consistency of the measurement items (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981; Malhotra, Mukhopadhyay, Liu, & Dash, Reference Malhotra, Mukhopadhyay, Liu and Dash2012). Similarly, the diagonal values (the square root of the Average Variance Extracted) are above the off-diagonal values (Table 8). This result indicates that the measurement items of this construct differ from those of the other constructs in the study. Furthermore, the correlations are less than 0.85 (see Table 8). Therefore, the discriminant validity of the constructs is validated.

Table 7. The reliability of the constructs

Notes: This table shows the reliability measures of the main constructs considered in empirical analysis. The reliability of one variable is the extent to which an instrument is reliable in measuring the variable (Awang, Reference Awang2015) and is measured through three criteria which are Cronbach’s alpha, Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and Construct Reliability (CR), following previous works such as Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). Cronbach’s alpha measures the internal coherence of the scale of the variables. A value of Cronbach’s alpha of at least 0.5 shows the reliability of the items in the questionnaire used to calculate the variables. AVE measures the amount of variance that is captured by a construct in relation to the amount of variance due to the measurement error. A value of AVE of at least 0.5 shows that the latent variables from the questionnaire explain at least 50% of the variance of the constructed variables (Awang, Reference Awang2015). CR measures the construct reliability. A value of CR higher than 0.7 is required to achieve construct reliability.

Table 8. Discriminant validity with digital financial knowledge (with the Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981) method)

Notes: According to Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), ME = Microfinance Effectiveness, PA = Poverty Alleviation, DFK = Digital Financial Knowledge, SC = Social Capital. Source: Authors’ calculations.

In addition, Table 9 shows the HTMT (Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations) results for assessing discriminant validity. An acceptable level of discriminant validity is with a value lower than 0.9, a criterion that all our variables meet. Tables 7A and 8A (in Appendix III) also demonstrate construct validity when the model incorporates traditional financial knowledge.

Table 9. Discriminant validity with digital financial knowledge (with the HTMT0.85 criterion)

Notes: According to the HTMT0.85 criterion. ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), ME = Microfinance Effectiveness, PA = Poverty Alleviation, DFK = Digital Financial Knowledge, SC = Social Capital. Source: Authors’ calculations.

Structural Equation Model (SEM)

Following the validity of the model presented above, Equation (1) illustrates the SEM used to analyze the relationship between microfinance effectiveness (exogenous variable) and poverty alleviation (endogenous variable):

where ![]() $P{A_i}$ represents the measure of poverty alleviation of participant i.

$P{A_i}$ represents the measure of poverty alleviation of participant i. ![]() $M{E_i}$ represents the measure of microfinance effectiveness of participant i.

$M{E_i}$ represents the measure of microfinance effectiveness of participant i. ![]() ${\varepsilon _i}$ represents the error terms.

${\varepsilon _i}$ represents the error terms.

To examine the moderating effect of digital and traditional financial knowledge, as well as social capital, we further estimate the equations below:

where ![]() $P{A_i}$ represents the measure of poverty alleviation of participant i.

$P{A_i}$ represents the measure of poverty alleviation of participant i. ![]() $M{E_i}$ represents the measure of microfinance effectiveness of participant i.

$M{E_i}$ represents the measure of microfinance effectiveness of participant i. ![]() $DF{K_i}$ represents the measure of digital financial knowledge of participant i.

$DF{K_i}$ represents the measure of digital financial knowledge of participant i. ![]() $F{K_i}{\text{ }}$represents the measure of traditional financial knowledge of participant i.

$F{K_i}{\text{ }}$represents the measure of traditional financial knowledge of participant i. ![]() $S{C_i}$ represents the measure of social capital of participant i.

$S{C_i}$ represents the measure of social capital of participant i. ![]() ${\varepsilon _i}$ represents the error terms.

${\varepsilon _i}$ represents the error terms.

Equations (2a), (2b), and (3) include three variables which are digital financial knowledge (DFK), traditional financial knowledge (FK), and social capital (SC), respectively. Importantly, an interactive variable between each of these three variables with microfinance effectiveness (ME) is also included. While coefficient ![]() ${\beta _2}$ measures their direct relationship with poverty alleviation, coefficient

${\beta _2}$ measures their direct relationship with poverty alleviation, coefficient ![]() ${\beta _3}$ allows to capture their moderating role on the link between microfinance effectiveness and poverty reduction. If

${\beta _3}$ allows to capture their moderating role on the link between microfinance effectiveness and poverty reduction. If ![]() ${\beta _3}$ is significant and positive, it means that DFK, FK, or SC, has a significantly positive moderating effect. In this case, when microfinance effectiveness increases, an increase in FK, DFK, or SC, will positively influence poverty alleviation. The same is applied for a negative moderating effect. For our research hypothesis to be validated, coefficient

${\beta _3}$ is significant and positive, it means that DFK, FK, or SC, has a significantly positive moderating effect. In this case, when microfinance effectiveness increases, an increase in FK, DFK, or SC, will positively influence poverty alleviation. The same is applied for a negative moderating effect. For our research hypothesis to be validated, coefficient ![]() ${\beta _3}$ in Equation (2a), related to digital financial knowledge, should be significant and positive.

${\beta _3}$ in Equation (2a), related to digital financial knowledge, should be significant and positive.

Results

Model Validity

Figure 2 shows the structural model obtained from the SEM analysis. This illustrates the relationships between the latent constructs of microfinance effectiveness (ME), digital financial knowledge (DFK), social capital (SC), and poverty alleviation (PA). Figure 2A in Appendix IV presents a similar model that incorporates traditional financial knowledge.

The arrows in Figures 2 and 2A show the direction and the strength of the connection among latent constructs, with higher values meaning stronger effects. The error term ‘e33’ illustrates the residual variance of the dependent variable (i.e., poverty alleviation). The direct and indirect relationships among the latent variables were statistically tested to confirm their significance. Furthermore, it is necessary to ensure that the estimated model fits well. In this regard, the SEM approach uses various goodness of fit indices to determine how the model fits the data sample. According to Kline (Reference Kline2011), there are three broad categories of model fit indices: absolute fit, parsimonious fit, and incremental fit. As shown in Table 10, including digital financial knowledge, all the considered fitness indices achieve the required thresholds,Footnote 4 indicating that the data and the model are reasonably well-matched. Table 9A (in Appendix V), including traditional financial knowledge, also shows the fitness of the model with the data sample.

Figure 2. The structural equation model (SEM) with digital financial knowledge

Table 10. SEM model fit statistics including digital financial knowledge

Notes: X2 = Chi-squared statistic, X2/df = Chi-Square to Degrees of Freedom Ratio, GFI = Goodness-of-Fit Index, AGFI = Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index, TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index, CFI = Comparative Fit Index, RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, IFI = Incremental Fit Index. Source: Authors’ calculations.

SEM Results

The results for digital financial knowledge (DFK) are presented in Table 11. Similarly, Table 10A in Appendix V shows the results for traditional financial knowledge (FK). Table 11 shows that there is a significant and positive relationship between Microfinance Effectiveness (ME) and Poverty Alleviation (PA) (β = 0.46, p-value = 0.000). Furthermore, DFK has a significant and positive relationship with PA (β = 0.11, p-value = 0.031). Similarly, social capital is also significantly and positively related to poverty alleviation (β = 0.09, p-value = 0.021).

Table 11. The validity of the research hypotheses including digital financial knowledge

Notes: H denotes hypothesis. H1, H2, and H3 denote the three hypotheses developed in second section. IV denotes independent variables. Path denotes the direction of the relationship. DV denotes the dependent variable. Column “Estimate” shows the results of the beta coefficients in Equations (1), (2), (3), and (4). Estimate (Std) denotes the standard deviation of the estimates. S.E. denotes standard errors. C.R. denotes Critical Ratio. P-value denotes the probability of the statistics of the significance test.

Table 11 shows the results of the moderating effect of DFK and social capital (SC) on ME, as determined by their interaction. The estimated interaction coefficient between ME and DFK is β = 0.11 (p-value = 0.018). This shows that DFK significantly and positively moderates the relationship. In other words, greater DFK strengthens the positive relationship between ME and PA. This may be because more educated microfinance clients can make a better use of microfinance loans, thereby reducing their level of poverty. This finding is in line with that in previous studies, such as Hasan et al. (Reference Hasan, Le and Hoque2021).

Although social capital is significantly related to poverty alleviation when considered as an independent variable (β = 0.09, p-value = 0.021), the estimated coefficient for its interaction with microfinance effectiveness (ME_SC) is not significantly different from zero (β = 0.03, ρ = 0.453). This important finding shows that SC does not significantly moderate the link between ME and PA. This result implies that SC can alleviate poverty independently of microfinance effectiveness. It suggests that the digital dimension of financial knowledge may be associated with an increased use of digital tools for connecting with others, leading to an increasing relationship between social capital and poverty alleviation.

As shown in Table 10A in Appendix V, incorporating traditional financial knowledge (FK) into the model leads to a positive relationship between ME and PA (β = 0.45, p-value = 0.000). Importantly, FK has a positive moderating effect on this relationship (β = 0.09, p-value = 0.022). However, the result regarding the moderating effect of SC is different. While SC is not significantly related to PA (β = 0.03, p-value = 0.554), it has a significant and positive moderating effect on the link between ME and PA (β = 0.06, p-value = 0.035). This result suggests that microfinance clients with a strong understanding of FK may not use digital tools to connect with other people. This may explain why social capital does not significantly alleviate poverty. Nevertheless, combining social capital with ME can further reduce poverty. In line with the findings in Table 11, Table 10A further shows that digital financial literacy can strengthen social connections and alleviate poverty, regardless of microfinance effectiveness.

Discussion

The results demonstrate that microfinance effectively alleviates poverty, considering a study sample of 500 microfinance clients in Pakistan, consistent with that of previous research by Hermes and Lensink (Reference Hermes and Lensink2011) and Tasos et al. (Reference Tasos, Amjad, Awan and Waqas2020). Notably, the SEM results revealed that digital and traditional financial knowledge positively moderate the link between microfinance effectiveness and poverty alleviation. These results suggest that financial and digital financial knowledge enable microfinance clients to make a better use of microfinance loans, thereby increasing their income and decreasing their level of poverty (Samer, Majid, Rizal, Muhamad, & Rashid, Reference Samer, Majid, Rizal, Muhamad and Rashid2015). This corroborates previous studies on the role of knowledge in improving financial conditions (Ginanjar & Kassim, Reference Ginanjar and Kassim2019). Therefore, this study recommends equipping microfinance clients with both financial and digital knowledge to improve the efficiency with which microfinance alleviates poverty.

The moderating role of social capital is significant and positive when financial knowledge is incorporated into the model. However, this is not the case when digital financial knowledge is included. The same applies to the relationship between social capital and poverty alleviation, insignificant in the model with financial knowledge while being positive in the model with digital financial knowledge. This result is in line with that of previous studies by Wu (Reference Wu2024), Xu (Reference Xu2024), Antonietti et al. (Reference Antonietti, Burlina and Rodriguez-Pose2025), and Li and Huang (Reference Li and Huang2025), which identified a positive moderating effect of social security and social capital. This important result leads us to make various observations. Firstly, there is a direct relationship between social capital and poverty alleviation in the context of digital finance. Digital tools facilitate social connections through digital social media, leading social capital to significantly influence poverty alleviation. However, the insignificant relationship between social capital and poverty alleviation when financial knowledge is included suggests that social capital alone is insufficient to influence poverty alleviation without a digital element. Therefore, optimizing the positive relationship between microfinance effectiveness and poverty alleviation would require optimizing both digital and physical social connections.

Another possible explanation for the difference in the moderating effect of social capital when digital financial knowledge is included in the model is how this knowledge is measured. The latter is constructed using two items: knowledge of credit cards and understanding the importance of timely bill payment. These items are therefore less related to the social dimension than the five items in the financial knowledge construct, which relate to controlling spending, financial planning, financial allocation for the family, insurance, and interest rates. This may explain why social capital does not moderate the relationship between microfinance effectiveness and poverty alleviation when digital financial knowledge is included in the model. It may also be because real social connections play a less important role for microfinance clients with digital financial knowledge as they rely on digital social connections instead. Consequently, one might infer that microfinance clients with digital financial knowledge would not seek advice from others when making financial decisions (Kumar, Pillai, Kumar, & Tabash, Reference Kumar, Pillai, Kumar and Tabash2023).

These findings also raise questions about the effect of digital technologies on the effectiveness of microfinance. Previous studies showed that digital technologies can have a dual effect on microfinance effectiveness. On the one hand, they improve operational efficiency (Wijayanti et al., Reference Wijayanti, Dwiningrum and Saptono2024). On the other hand, they also increase the likelihood of microfinance institutions drifting from their mission to reduce poverty (Bisht, Noronha, & Tripathy, Reference Bisht, Noronha and Tripathy2025). Furthermore, Sebai and Bouzadi (Reference Sebai and Bouzadi2025) also identified FinTech’s dual impact on microfinance institutions. On the one hand, FinTech improves operational efficiency, reduces costs, and increases access to financial services for microfinance clients. On the other hand, it raises issues such as cybersecurity and compliance risks. Therefore, alongside previous research, our results suggest that digital technologies are an effective tool to reduce poverty. However, to achieve this, it is important to consider the associated risks related to reduced social connection quality, microfinance institutions’ mission drift, cybersecurity issues, and compliance issues.

Conclusion

This study examines the relationship between microfinance effectiveness and poverty alleviation, exploring the moderating effect of digital and traditional financial knowledge, as well as of social capital. With a sample of 500 microfinance clients in Pakistan, the empirical results demonstrate a significant positive relationship between the effectiveness of microfinance and poverty alleviation. Notably, both digital and traditional financial knowledge have a significant and positive moderating effect on the relationship between microfinance effectiveness and poverty alleviation. It therefore emphasizes the importance of providing microfinance clients with both financial and digital skills. Social capital, or connections with other people, also has an important role in microfinance effectiveness towards poverty alleviation. In addition, it also positively moderates the relationship between microfinance effectiveness and poverty alleviation when traditional financial knowledge is included in the model. However, when it comes to digital financial knowledge, this effect no longer exists. This important result suggests that digital financial knowledge may lead to stronger connections with other people through digital social media. Therefore, digital financial knowledge can lead to a stronger moderating influence, compensating the influence of social capital. This finding may help better understand the dual effect of digital technologies on poverty alleviation, positive on the one hand (e.g., Lechman & Popowska, Reference Lechman and Popowska2022), and negative of the other hand (e.g., Dzator et al., Reference Dzator, Acheampong, Appiah-Otoo and Dzator2023), through the channel effect of digital technologies on social capital.

The results of this study make contributions to knowledge on the role of digital technologies in alleviating poverty. Given the positive moderating effect of digital financial knowledge, we recommend that governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and microfinance institutions continue to improve education programmes focusing on digital and financial literacy. This recommendation aligns with the findings of Si et al. (Reference Si, Hall, Cui and Wei2024) that digital technology disrupts entrepreneurship and business models, creating new opportunities to alleviate poverty. Therefore, to capture the positive effects of digital technologies, it is important to understand the factors that determine individuals’ level of digital financial knowledge. In this regard, Lyons and Kass-Hanna (Reference Lyons and Kass-Hanna2021) recommended considering the five dimensions which are ‘basic knowledge and skills, awareness, practical know-how, decision-making, and self-protection.’

Furthermore, this study encourages microfinance institutions to use digital technologies to reduce poverty in emerging markets, such as Pakistan and China. Previous research showed that digital technologies have a dual effect on microfinance institutions. On the positive side, they can improve operational performance (Khanchel, Lassoued, & Khiari, Reference Khanchel, Lassoued and Khiari2025; Wijayanti et al., Reference Wijayanti, Dwiningrum and Saptono2024). On the negative side, Bisht et al. (Reference Bisht, Noronha and Tripathy2025) found that digital technologies lead microfinance institutions to drift from their original purpose to reduce poverty, leading to a decreasing quality of services provided to the clients. Our results help understand this negative side because when digital financial knowledge is included in the model, social capital no longer has a positive moderating effect on microfinance effectiveness in poverty alleviation. Therefore, it is essential to understand and measure the effect of digital technologies on social connections of microfinance clients.

Finally, the study can be extended by including other emerging countries, such as China. However, the significant differences in digital technologies and microfinance between China and Pakistan need to be considered. Given China’s advanced digital technologies, measures of digital financial knowledge need to be adapted for its population. Similarly, Pakistan’s extensive microfinance landscape, which combines conventional and Islamic microfinance, is also an important difference with China. Therefore, we recommend that future research considers specific characteristics related to each country.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Xiao-Ping Chen, Editor-in-Chief, University of Washington, US, and Professor Steven Si, Guest Editor of the special issue on ‘Digital Poverty Reduction through Entrepreneurship and Innovation’, Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania, US, and Zhejiang University, China. We are very grateful to two anonymous reviewers whose comments helped us to significantly improve our manuscript through the two rounds of revision. We would also like to thank the respondents to our survey for their time and effort in completing the questionnaire. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/nsv53/files?view_only=fa26c6151c054ae28ab401ac4cc0066c

APPENDICES

Appendix I: Questionnaire Used in the Survey

Part A: Socio-Demographics

Part B: Microfinance Effectiveness, Poverty Alleviation, Financial Knowledge, Digital Financial Knowledge, and Social Capital

Read each statement carefully and select the most suitable choice for you.

1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree

Table 2A. Detailed descriptive statistics of the constructs’ items

Notes: ME = Microfinance Effectiveness, PA = Poverty Alleviation, DFK = Digital Financial Knowledge, FK = Traditional Financial Knowledge, SC = Social Capital, N = 500

Appendix II: The Model with Traditional Financial Knowledge

Figure 1A. The constructs’ measurement model with traditional financial knowledge

Appendix III: The Validity of the Variables including Traditional Financial Knowledge

Table 7A. Discriminant validity with traditional financial knowledge (with the Fornelle and Larcker (1981) method)

Notes: According to Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981).**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), ME = Microfinance Effectiveness, PA = Poverty Alleviation, FK = Traditional Financial Knowledge, SC = Social Capital. Source: Authors’ calculations.

Table 8A. Discriminant validity with traditional financial knowledge (with the HTMT0.85 criterion)

Notes: According to the HTMT0.85 criterion. ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), ME = Microfinance Effectiveness, PA = Poverty Alleviation, FK = Traditional Financial Knowledge, SC = Social Capital. Source: Authors’ calculations.

Appendix IV: The SEM with Traditional Financial Knowledge

Figure 2A. The structural equation model (SEM) with traditional financial knowledge

Appendix V: The SEM Results including Traditional Financial Knowledge

Table 9A. SEM model fit statistics with traditional financial knowledge

Notes: X2 = Chi-squared statistic, X2/df = Chi-Square to Degrees of Freedom Ratio, GFI = Goodness-of-Fit Index, AGFI = Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index, TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index, CFI = Comparative Fit Index, RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, IFI = Incremental Fit Index. Source: Authors’ calculations.

Table 10A. The validity of the research hypotheses with traditional financial knowledge

Notes:: H denotes hypothesis. H1, H2, and H3 denote the three hypotheses developed in section 2. IV denotes independent variables. Path denotes the direction of the relationship. DV denotes the dependent variable. Column Estimate shows the results of the beta coefficients in Equations (1), (2), (3), and (4). Estimate (Std) denotes the standard deviation of the estimates. S.E. denotes standard errors. C.R. denotes Critical Ratio. P-value denotes the probability of the statistics of the significance test.

Muhammad Asif Nadeem (masifkhemta@gmail.com) is an assistant professor of finance at Lahore Business School, University of Lahore (Pakistan). His teaching and research interests include behavioral finance, fintech, Islamic finance, financial innovation, and sustainable finance. He has published his research work in journals such as Frontiers in Psychology, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, and Journal of Islamic Business and Management.

Waheed Akhter (drwaheed@cuilahore.edu.pk) is an associate professor at the Department of Management Sciences, COMSATS University Islamabad, Lahore Campus (Pakistan). His teaching and research interests include Islamic banking, takaful, bank liquidity creation, financial stability, risk management, and behavioral finance. He has published his research in journals such as Financial Innovation, Finance Research Letters, Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, Journal of Economic, and Administrative Sciences.

Thi Hong Van Hoang (thv.hoang@mbs-education.com) is a full professor of finance at MBS School of Business (France). Her teaching and research topics deal with sustainable finance, corporate finance, financial markets, and environmental economics. Her research has been published in journals such as The Energy Journal, Economic History Review, Business Strategy and the Environment, Accounting and Finance, International Review of Financial Analysis, Small Business Economics, Energy Economics, and Economic Modelling.