Because US Supreme Court justices prohibit cameras in their courtroom and rarely communicate directly with the public about their decisions, most Americans do not learn about their work firsthand (Zilis Reference Zilis2015). Instead, they rely on the news media for coverage, and that coverage plays a central role in shaping popular perceptions of the Court (Meyer Reference Meyer2021). Historically, media coverage of the Court has been limited, with only a few major print outlets reporting on it at all. Those outlets typically discussed a small number of high-salience decisions, and their accounts often presented a narrow, apolitical, and legal view of the Court’s work (Vining and Marcin Reference Vining and Marcin2014). This style of reporting, in turn, reinforced public support for the Court’s authority to make consequential decisions (Johnston and Bartels Reference Johnston and Bartels2010). However, a recent combination of media diversification and broader access to the Court’s proceedings is changing what gets covered, how, and where (Houston, Johnson, and Ringsmuth Reference Houston, Johnson and Ringsmuth2023). These changes increase the likelihood that the public encounters different aspects of the Court’s work—lower-salience cases, ideological divisions among justices, and the back-and-forth of working through important legal decisions—and could fundamentally alter the public’s understanding of the Court’s position in American politics.

Unlike other political institutions, whose legitimacy stems from popular elections, the Supreme Court’s legitimacy is built on the popular belief that it has the authority to make the decisions that it does (Johnston and Bartels Reference Johnston and Bartels2010), and that legitimacy is shaped by the public’s knowledge and perceptions of the Court and its activities (Zilis Reference Zilis2015). Consequently, understanding the nature of the Court’s media coverage is crucial for understanding how people react to the institution and the decisions the justices make. Scholars have traditionally used print media coverage of the Court’s decisions in major national print outlets—first the New York Times and later the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune—to study this relationship (Collins and Cooper Reference Collins and Cooper2012). The distinctive nature of Court reporting, characterized by an access hierarchy that favors certain outlets while making coverage difficult and costly for others,Footnote 1 as well as the Court’s reluctance to adapt to a 24-hour news cycle (Houston and Ringsmuth Reference Houston and Ringsmuth2024), shaped how scholars approached the topic. The similarity of coverage across outlets made relying on these sources a reasonable research choice for decades. Yet the move from page-restricted print media to digital platforms with unlimited space and rolling deadlines (Shearer Reference Shearer2021), as well as the Court’s decision to expand access to its processes in 2020 (Houston, Johnson and Ringsmuth Reference Houston, Johnson and Ringsmuth2023), suggests this approach needs reevaluation. If the media environment is evolving, and the changing environment in turn affects where people obtain news about the Supreme Court and what they learn about it, then scholars must consider its variety when studying the relationship between the public and the Court. That is, they need to consider where individuals find their information (Johnston and Bartels Reference Johnston and Bartels2010), which cases and processes are covered (Black et al. Reference Black, Johnson, Owens and Wedeking2024), how much coverage different venues generate (Truscott Reference Truscott2024), and how that coverage presents the Court to the public (Boston and Krewson Reference Boston and Krewson2025).

If the media environment is evolving, and the changing environment in turn affects where people obtain news about the Supreme Court and what they learn about it, then scholars must consider its variety when studying the relationship between the public and the Court.

This study takes a first step toward understanding the new media landscape by investigating whether Supreme Court coverage actually is undergoing measurable change. To do this, we examine the quantity and distribution of coverage across print and broadcast outlets’ physical and online coverage. Using updated data on both oral arguments and decision coverage, this article provides a descriptive, over-time account of the quantity and distribution of Supreme Court coverage across print and broadcast-affiliated platforms. We trace shifts in the parts of the Court’s process that receive media coverage, from the era of printed opinions and restricted access to the digital and better-accessed media environment that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our analysis reveals that the major national print outlets on which scholars traditionally relied have steadily reduced their coverage of decisions since the 1970s, with three of these so-called Big Four outlets reaching all-time coverage lows by 2021. In that same period, however, other print and broadcast-affiliated outlets began covering the Court from different angles, including giving more attention to oral arguments. Although we did not directly assess framing or audience exposure, our findings contribute to a growing literature that suggests coverage patterns are changing in meaningful ways (Boston and Krewson Reference Boston and Krewson2025; Hitt and Searles Reference Hitt and Searles2018). Given recent discussions about the public’s shifting feelings of judicial legitimacy during the Supreme Court’s rightward turn (Gibson Reference Gibson2024), it is increasingly important to acknowledge these informational changes and incorporate them into scholars’ understanding of judicial legitimacy. This study presents scholars with evidence of the need to make that change.

COURT COVERAGE BEYOND THE BIG FOUR

The transition from print to digital media fundamentally reshaped US Supreme Court coverage. For much of the twentieth century, traditional print publications, including the New York Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, and Los Angeles Times, provided the public with primary analyses on the Court’s decisions and arguments (Vining and Marcin Reference Vining and Marcin2014).Footnote 2 These major national outlets employed specialized legal beat reporters who had Court-granted access, which they used to explain the institution’s procedures and translate its complex work into accessible (if often legalistic) language for public consumption (Davis Reference Davis, Davis and Taras2017). Traditional broadcast media, including radio and the three original major television networks, offered brief same-day recaps of the Court’s decisions, but in-depth discussion appeared in the following day’s print coverage. That coverage served as the true starting point of public conversation (Collins and Cooper Reference Collins and Cooper2012). Traditional print outlets thus had a central role in shaping the public’s understanding of the judiciary. Their coverage was viewed as authoritative, and it ultimately formed the foundation for popular and scholarly interpretations of the Court’s role in American governance (Johnston and Bartels Reference Johnston and Bartels2010).

The print-focused model began to shift in the late-twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries as traditional media began departing from established journalistic routines. Both print and broadcast-affiliated outlets launched web versions of their publications to meet the needs of a digitally engaged audience (Levy and Nielsen Reference Levy and Nielsen2010), offering continuous updates, faster reporting, and access to source documents such as opinions and oral argument transcripts (Houston, Johnson, and Ringsmuth Reference Houston, Johnson and Ringsmuth2023).Footnote 3 Although most Americans did not read the opinions themselves, they were able to follow real-time expert analysis published alongside those documents to understand the Supreme Court’s work (Zilis Reference Zilis2015). These digital platforms also allowed for more dynamic interaction between the public and reporters through comment sections, social media threads, live blogs, and multimedia explainers (Houston and Johnson Reference Houston and Johnson2023; Sorenson, Houston, and Savage Reference Sorenson, Houston and Savage2024). In this new environment, audiences not only read about the Court but also engaged in conversations about it.

The digital shift in traditional print and broadcast-affiliated media also opened the door for a wider range of outlets to cover the Court. In the pre-digitization era, outlets without hard passes at oral argument faced major hurdles in accessing real-time information. They could send reporters to Washington, DC, and hope to secure a day pass on the right day; rely on Associated Press summaries; or publish delayed post-decision commentary. Crucially, with credentialed outlets posting source documents online, outlets that lacked physical access could quickly obtain documents, audio, and context, as well as provide timely updated and deeper coverage.Footnote 4 This shift did not simply increase the amount of coverage either; research suggests it also changed its tone. Many digital-first and nontraditional outlets departed from the deferential tone typically found in traditional print and broadcast-affiliated coverage. They opted to approach the Court as a political institution, framing the justices as political actors and decisions as policy outcomes with winners and losers (Hitt and Searles Reference Hitt and Searles2018). Traditional print outlets also began using political language to discuss the Court (Boston and Krewson Reference Boston and Krewson2025), although their daily coverage continued to use traditional legalistic frames to discuss decisions (Lithwick Reference Lithwick2014).

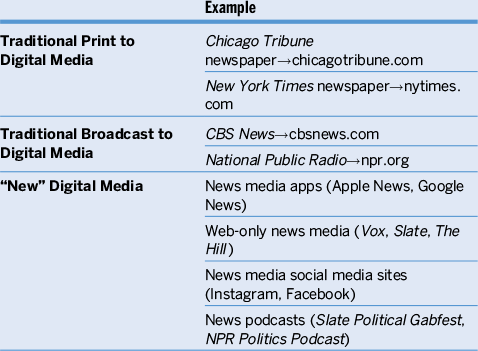

By 2020, the change was unmistakable. According to the Pew Research Center, by the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, 58% of Americans preferred to receive their news digitally, while only 5% still favored print media (Shearer Reference Shearer2021). Even more striking, 82% reported obtaining at least some of their news from a digital device, whether a cell phone, tablet, or computer. We suspect this transformation, presented in table 1, signals more than a change in format; it also suggests that Americans can now encounter the Supreme Court through a wider range of outlets and perspectives. No longer constrained by physical access or print and broadcast-affiliated deadlines, these outlets can provide more frequent and immediate coverage of the Court, offering new opportunities for the public to follow its work.

Table 1 Examples of Different Media Outlets

HEAR YE, STREAM YE: THE SUPREME COURT GOES FOR ACCESSIBILITY

Even as the media environment expanded, the Supreme Court remained largely resistant to public access, earning the title of the least accessible institution in American government. The justices have long resisted efforts to open their work to the public (Black et al. Reference Black, Johnson, Owens and Wedeking2024), rarely write opinions with lay audiences in mind (Black et al. Reference Black, Owens, Wedeking and Wohlfarth2016), routinely decline to explain their reasoning beyond the official written opinion (Zilis Reference Zilis2015), and sometimes fail to even publish an opinion. Most of their work is done out of the public eye, and the justices prefer it that way.

Beyond the justices’ secrecy, their refusal to preemptively schedule opinion releases or notify journalists when important opinions were imminent made covering the accessible parts of the Court’s process a logistical nightmare (Houston and Ringsmuth Reference Houston and Ringsmuth2024). When journalists went to the Court for oral argument and opinion releases, the Court set aside only 36 of 400 seats for them, and the ban on bringing electronic devices into the courtroom made it difficult to fully capture the proceedings (Carter Reference Carter2012). The Court released paper copies of opinions on the day the justices delivered them, but it offered only delayed audio recordings and transcripts for reconstructing oral arguments, which made real-time reporting of them almost impossible (Rosenberg and Feldman Reference Rosenberg and Feldman2008). Most media outlets consequently focused on final decisions and, in doing so, left discussions of oral arguments to a niche group of legal reporters, despite their obvious importance to the Court’s decision-making process (Clark, Lax, and Rice Reference Clark, Lax and Rice2015).

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the Supreme Court began livestreaming audio of its oral arguments in May 2020 (Houston, Johnson, and Ringsmuth Reference Houston, Johnson and Ringsmuth2023). With that decision, the Court opened a new window into its inner workings, granting journalists and the public unprecedented access to a once-restricted part of its process. Livestreaming removed long-standing barriers to access, and reporters could now quote justices in real time, provide immediate expert commentary, and construct more nuanced accounts of judicial reasoning. Rather than reacting only to final rulings, journalists could track the development of legal arguments as they unfolded and offer a fuller account of the Court’s work.Footnote 5 Importantly, livestreaming also allowed more outlets to provide that type of coverage.

Critically, livestreaming expanded access to oral arguments for both journalists and the public, significantly shaping how the Supreme Court was portrayed and understood. Oral arguments reveal the justices’ tone, priorities, ideological leanings, and legal reasonings—all insights that are often less apparent in final opinions (Black et al. Reference Black, Johnson, Owens and Wedeking2024). For the first time, people could hear the Court at work in real time, with all its legal and political dynamics, and that information was disseminated across a wide range of outlets. Consequently, livestreaming changed not only who could cover the Court but also which aspects of its work received attention, potentially influencing how the public understands the institution (Ramirez Reference Ramirez2008). Even if most Americans do not listen to live arguments, they are increasingly exposed to the Court through this new streaming-informed coverage (Houston, Johnson and Ringsmuth Reference Houston, Johnson and Ringsmuth2023).Footnote 6 We believe the traditional print and broadcast-affiliated media’s shift to digital platforms, combined with the Court’s increased accessibility of oral arguments, not only provided more diverse reporting on the Court but also led to an expansion of the parts of the Court’s process covered by those outlets.

THE TRANSFORMATION OF SUPREME COURT MEDIA COVERAGE

To examine shifts in the Supreme Court’s media landscape, we took a two-pronged approach (Cota et al. Reference Cota, Houston, Lane and Schoenherr2026). First, we collected data on decision coverage between the 2015 and 2021 terms in the print editions of four major, geographically diverse national newspapers: the New York Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, and Los Angeles Times. Footnote 7 Reporters for the New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times hold Supreme Court hard passes, which grant them year-round access to the Court’s building and reserved seating in the press section during oral arguments. This level of access allows for consistent, on-the-ground reporting of the Court’s procedural activities and institutional developments and places these journalists among the most knowledgeable and engaged regarding Supreme Court coverage. In contrast, the Chicago Tribune held a hard pass until 2011, after which its editors began relying on AP Wire content for Court reporting. We included it in our analysis to reflect how most regional newspapers now cover the Court.

Second, we examined how different print and broadcast outlets cover different parts of the Court’s process on their digital platforms, focusing specifically on oral arguments and decision coverage. For this part of the analysis, we used data from Houston, Johnson, and Ringsmuth’s (Reference Houston, Johnson and Ringsmuth2023) study of online print and broadcast-affiliated coverage of oral arguments. For print outlets, they examined online stories from the 10 highest-circulation weekday newspapers: the four major national outlets listed previously and USA Today, Wall Street Journal, New York Post, Minneapolis Star Tribune, Boston Globe, and Newsday. For broadcast-affiliated outlets, they analyzed stories published on the websites of the eight most-watched television networks: the three original major broadcast outlets (i.e., NBC News, CBS News, and ABC News) and five others (i.e., Fox News, PBS, MSNBC, CNN, and Fox Business).Footnote 8

ANALYSIS

We first examined how coverage of the Supreme Court’s decisions by the four major print newspapers changed over time (figure 1). Figure 1 displays two important pieces of information. First, it shows the percentage of the Court’s docket that received decision coverage (left y-axis) in the New York Times (solid line), Washington Post (dot-dash line), Chicago Tribune (dashed line), and Los Angeles Times (dotted line), from 1953 to 2021.Footnote 9 Second, it shows the size of the Court’s docket each term (gray bars, count on the right y-axis), allowing us to examine the share of coverage relative to the docket size. We used percentage of the docket as our primary metric to allow for meaningful comparisons over time. As shown in figure 1, the Court’s docket has declined substantially over time for a multitude of reasons (Lane Reference Lane2022). Measuring the percentage of cases covered each year thus allowed us to assess how selective newspapers have been in their editorial focus given this change.

Figure 1 Percentage of Court’s Docket Covered by Major National Print Outlets

The left y-axis shows the percentage of decisions each term that received newspaper print coverage in the Chicago Tribune (dashed line), Los Angeles Times (dotted line), New York Times (solid line), and Washington Post (dot-dashed line). All lines are loess trend curves of the data. The right y-axis shows the total number of cases that the Court reviewed each term, represented by light gray bars.

As shown in figure 1, the Supreme Court was hearing between 140 and 150 cases per term in the 1970s and 1980s. During that period, most of the outlets covered about half of the Court’s decisions each term.Footnote 10 When the Court’s docket began decreasing in the late 1980s, the four major newspapers appeared to handle the change differently. The Washington Post increased the proportion of the docket covered to almost 60%, whereas decision coverage in the New York Times remained consistent at 40% to 50%, and coverage in the Los Angeles Times and Chicago Tribune decreased to all-time lows. It is important to note, however, that—given the decrease in the Court’s docket—even an uptick in the percentage covered pales in comparison to the number of decisions receiving coverage a few decades earlier.

Given these findings, the trends point to an overall decrease in the number of cases covered each term. As shown in figure 2, which displays the number of cases covered by one of these four major outlets every term, major national print outlets cover between 30 and 50 cases each term in the current era, compared to approximately 100 cases in the larger docket era. It appears that most outlets became more selective about their coverage as the docket decreased in size.

Figure 2 Number of Cases Covered in Major National Print Outlets by Term

The y-axis shows the total number of decisions each term that received newspaper print coverage in the New York Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, and Los Angeles Times.

Building on our analysis of print newspaper decision coverage, we next expanded both the stage of the Supreme Court’s process under analysis (i.e., decisions and oral arguments) and the format of media coverage (i.e., print and online stories). Specifically, we examined how the four major national outlets—New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune—covered oral arguments and decisions in their print publications and online stories. Figure 3 illustrates coverage at each stage of the Court’s decision-making process—only the oral argument (black), only the decision (dark gray), both (lighter gray), or no coverage (light gray)—across the four major print outlets between the 2019 and 2021 terms, representing the periods before and after the Court’s accessibility shift. Figure 3 suggests that despite the Court becoming more accessible in 2020 through audio livestreaming, major news outlets did not increase their attention to oral arguments. Before the shift, the New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times regularly reported on oral arguments. For example, the Los Angeles Times discussed 21% of the Court’s orally argued cases on the day they happened, the Washington Post discussed 40%, and the New York Times discussed 48%. After the introduction of audio livestreaming, however, coverage of oral arguments declined to 16%, 20%, and 29% of the Court’s 2021 docket, respectively; the Washington Post and New York Times differences were significantly smaller.Footnote 11 Interestingly, their focus was in different directions, with the Washington Post spending significantly more time on decisions than it had in the past (i.e., from 21% to 39%); both the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times dedicated approximately equal attention to the Court. Despite our assumptions, the data suggest that easier access did not increase oral argument coverage among the major national print outlets that already had access to the Court’s proceedings.

Figure 3 Oral Argument and Decision Coverage by Term

Coverage of Supreme Court oral arguments and decisions in the Los Angeles Times (top left), Chicago Tribune (top right), Washington Post (bottom left), and New York Times (bottom right), presented by term. Different colors indicate different levels of coverage, from only covering oral argument (black), to only covering decisions (darkest gray), to covering both oral argument and decisions (lighter gray), to no coverage (lightest gray). Values represent the percentage of docket falling into that category.

That said, other outlets are taking advantage of the Supreme Court’s increased accessibility and providing at least some coverage of oral arguments. We now turn to other print media and broadcast-affiliated outlets’ online print stories, focusing exclusively on their coverage of oral arguments, which is shown in figure 4. The left side of figure 4 compares how often the four traditionally used major national print outlets and other large print outlets (i.e., USA Today, Wall Street Journal, New York Post, Minneapolis Star Tribune, Boston Globe, and Newsday) covered oral arguments in online content between the 2019 and 2021 terms. Figure 4 ranges from cases in which neither outlet type covered the argument (light gray), to both types covering it (darker gray), to only the traditional four major national outlets providing coverage (darkest gray), to only the other newspaper outlets covering it (black). Overall, our results suggest a strong consensus on which oral arguments are considered newsworthy: the four major print outlets and other print outlets agreed between 85% and 90% of the time. This level of agreement increases the likelihood that the public encounters information about many of the same cases, but disagreement in 10% to 15% of cases still matters. It means that depending on the outlet, people may be learning about different cases and could be doing so through potentially politicized lenses.Footnote 12 In 2020, for example, as the Supreme Court expanded its accessibility, other print outlets actually covered more oral arguments than their traditionally used counterparts, which highlights how different outlets may be more responsive to shifts in institutional transparency.

Figure 4 Breadth of Oral Argument Coverage

Comparison of breadth of Supreme Court oral arguments coverage. The left side compares print coverage in the four major print outlets against those in other top print outlets. The right side compares coverage in the four major print outlets against coverage in broadcast outlets. Different colors indicate different levels of coverage, from coverage exclusively in other outlets (black), to coverage exclusively in traditional major print outlets (darkest gray), to coverage in both outlet types (light gray), to no coverage (lightest gray).

The right side of figure 4 compares the coverage of Supreme Court oral arguments by the four major national print outlets with the eight most-watched broadcast networks (i.e., NBC News, CBS News, ABC News, Fox News, PBS, MSNBC, CNN, and Fox Business). Again, our findings indicate a broad consensus about which oral arguments are newsworthy: both types of outlets covered the same arguments between 80% and 90% of the time. This suggests that regardless of whether Americans consume news by browsing print newspapers or broadcast-affiliated outlets online, they are likely to encounter the same cases. Unlike the pattern we observed with print and broadcast-affiliated media, however, there was no noticeable increase in coverage following the Court’s accessibility changes in 2020. This may be because five of the eight broadcast networks already held hard passes, giving them access to oral arguments even before the reforms, thereby reducing the impact of the expanded public availability of audio livestreaming.

Despite the general agreement in which cases are covered among major print outlets, other print outlets, and broadcast-affiliated networks, it is noteworthy there are decreases in coverage regardless of the source. That is, the lightest gray bars in figure 4, which indicate that neither type of media outlet covered a case at oral argument, steadily increased over the three-term period. Although this is not sufficient evidence to draw conclusions that all outlets are covering the Supreme Court less, we know from figures 1 and 2 that major national print outlets have decreased their coverage. If we review other print and broadcast-affiliated outlets only in this abbreviated period, the data suggest the outlets are not making up the difference by covering decisions or oral arguments. Even with increased access and broad digital presence, outlets are still covering the Court less than they did. This could be a result of the Court’s docket getting smaller and, with it, the number of cases worth covering. We suspect scholars will need a longer observation period to fully understand this dynamic, however.

Even with increased access and broad digital presence, outlets are still covering the Court less than they did.

CONCLUSION

Former Justice Stephen Breyer recently observed, “If you want a rule of law…you can’t just talk to the judges and you can’t just talk to the lawyers….It is the people in the towns, in the villages…they’re the ones that have to be convinced that it is in their interest to follow decisions, even when those decisions affect them in a way they don’t like and when those decisions are wrong.”Footnote 13 His words underscore the importance of public understanding and engagement with the judiciary, especially in an era when information about the Supreme Court is increasingly shaped by the digital media environment. If legitimacy rests with the people, then the media pathways through which they come to know and interpret the Court are not only worth studying; they are also essential.

If legitimacy rests with the people, then the media pathways through which they come to know and interpret the Court are not only worth studying; they are also essential.

Our goal was to examine how changes in accessibility and the media landscape influenced the amount of Supreme Court coverage. In pursuit of that goal, this article presents a descriptive snapshot of the Court’s evolving media environment by highlighting several changes in how and how often the institution is covered. Whereas our results suggest that most major traditional print outlets are covering the Court less than in the 1980s, they also suggest other print and broadcast-affiliated outlets are using their digital platforms to report about the Court. We view this as a positive development. At a minimum, digitization and increased accessibility allow more outlets to cover the Court than ever before, and our analysis suggests that many other print and broadcast-affiliated outlets are covering the Court at multiple points in the process. Consequently, the public has more avenues for learning about the Court’s work, and those avenues can give them a fuller picture of an institution that typically is shrouded in mystery and thus difficult to understand. Looking beyond informational sources, the proliferation of different outlets suggests people will also learn about the Court from different viewpoints, which allows them to see it in more ways than traditional major national newspapers typically allow.

Our analysis is intentionally descriptive. Rather than explaining why particular outlets adjusted their coverage or how these changes shape public opinion, our goal was to document the structural transformation of the Supreme Court’s media environment. Establishing how much coverage exists, where it happens, and which parts of the Court’s process receive attention is a necessary first step for research that seeks to evaluate shifts in framing, interpret the consequences of coverage for legitimacy, and assess how different media ecosystems construct narratives around the Court.

Our findings broadly suggest that scholars must rethink how they use media coverage to study the public’s interactions with the Supreme Court. Today’s media ecosystem is fragmented, personalized, and fast-moving. Yet many researchers still rely on print coverage in major national newspapers to infer public attention to the Court. Our analysis reveals that the media environments in which traditional print and broadcast-affiliated outlets work have changed in meaningful ways. These modern outlets are presenting the public with more and different information about the Court. This reality carries significant implications for how people learn about and perceive the Court, and it should inspire new research about the connection between modern media and perceptions of judicial legitimacy, transparency, and fairness.

While our analysis provides an important first step toward understanding the modern relationship between the American public, the media, and the Supreme Court, it is not without limitations. First, we did not examine the full scope of the exclusively digital platforms on which people now access information about the Court, including social media, Supreme Court–focused blogs, websites, and podcasts. These platforms have an increasingly central role in shaping the public’s media diet (Shearer Reference Shearer2021). Just as broadcast and print coverage vary in substance and style (Hitt and Searles Reference Hitt and Searles2018; Vining and Marcin Reference Vining and Marcin2014), digital-native outlets likely do the same. Relatedly, future research could also examine how commentary-driven media rely on, reinterpret, and selectively amplify traditional news coverage of the Supreme Court, potentially shaping public understanding. Many of these outlets lack traditional journalistic editorial oversight, which makes them wholly new sources worthy of study (Zilis and Wedeking Reference Zilis and Wedeking2022). The emergence of these platforms invites scholars to revisit long-standing assumptions about how the public, political institutions, and the media interact (Cook Reference Cook2012).

Second, shifts in media coverage may also reflect changes in personnel, such as the transition from Linda Greenhouse to Adam Liptak at the New York Times. We do not attribute long-term trends to individual reporters; however, changes in writing style, editorial emphasis, and newsroom priorities may contribute to broader patterns in how the Court is covered. Future research could explore how individual reporters and editorial leadership shape the tone, frequency, and focus of Supreme Court coverage over time.

Third, we do not assess how the public engages digitally with Court coverage across these platforms. Today, engagement—including likes, shares, and comments—often determines which stories rise to prominence and which are ignored (Guess Reference Guess2021). This can result in selective exposure to certain narratives about the Court, shaping what people believe they know about it in unusual ways (Houston and Johnson Reference Houston and Johnson2023; Truscott Reference Truscott2024). Understanding which accounts gain traction and who interacts with them is a critical step toward mapping the public’s “judicial media diet.”

Fourth, future research also should examine how ongoing consolidation of media ownership may further standardize or replicate Supreme Court coverage across outlets, potentially narrowing the range of distinct narratives available to the public. Ultimately, if the legitimacy of the Supreme Court depends on an informed public, then understanding how a consolidated but fragmented, fast-moving, and increasingly digital media environment constructs the stories people see about the Court is more than a scholarly exercise; it is crucial for understanding the future of judicial authority in American democracy.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096525101807.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This analysis was presented at the 2024 Annual Meeting of the Southern Political Science Association and the 2023 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association. We thank Sara Benesh, Alison Higgins Merrill, and the Law and Courts Women’s Writing Group for their thoughtful comments on previous drafts, and Todd Collins for his encouragement of this project.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PQ4P1M.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.