1. Introduction

1.1. What’s special about multilingualism?

Language processing is popularly considered to be a skill, with the ambient and persistent demands of language use being able to carry over cognitive capacity to other domains. Much research has provided evidence to the idea that multilingual speakers keep all languages active even when only one is being used (extensive review in Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Craik, Green and Gollan2009). Competing representations of a message in two different languages may extend throughout the assumed pipeline of speech production. The attentional control problem generated here is unique to multilinguals in that they not only have to select a representation that most appropriately meets all semantic and linguistic criteria, but it is also part of the target language system. In principle, the cognitive demands made in this formulation process surpass those made by a monolingual speaker.

The mechanisms of such suspected advantages are speculated from several different perspectives when trying to locate advantages specific to multilinguals. Much cognitive and neurological work on non-verbal performance follows from the study of attentional control with respect to a target system and a simultaneously activated, competing system of knowledge. Studies here are multi-focused but generate evidence for a horizontal model of translation and activation. The locus of language selection is dependent on various factors such as language proficiency or demands of the production task, making it so that there is no single locus of selection in planning (Kroll, Bobb & Wodniecka, Reference Kroll, Bobb and Wodniecka2006). Certain conditions also open speech planning to cross-language influences, while others keep it restricted to one language. Neuroimaging studies indicate that bilingual switching activates shared neural tissue, with area differences being attributed to unbalanced proficiency (review in Abutalebi, Cappa, & Perani, Reference Abutalebi, Cappa and Perani2005). Studies on translators provide support – their two languages interact while the source language is encoded and before the target language is spoken (Christoffels & De Groot, Reference Christoffels, De Groot, Kroll and De Groot2005; Macizo & Bajo, Reference Macizo and Bajo2006).

A majority of studies preceding the past decade make cross-group comparisons between monolingual and bilingual performance in executive functions. Like ‘bilingualism’, ‘executive function’ is an umbrella term and can be used to understand a wide variety of control processes. Green and Abutalebi (Reference Green and Abutalebi2013) identify eight of these: goal maintenance, salient cue detection, distractor suppression, conflict monitoring, selective response inhibition, opportunistic planning, task engagement and task disengagement. De Bruin (Reference De Bruin2019) also identifies common measures of bilingual experience that are studied in relation to executive function measures: age of acquisition (AoA), proficiency, context of language acquisition, frequency of language use, language switching and language context.

1.2. Evidence for bilingual advantages

Research largely employs between-group designs: monolingual and bilingual groups are examined against one another. The main effect marked by bilingual advantages is that of managing a set of task demands: inhibiting, shifting, updating and monitoring. The initial assumption that managing two competing languages enhances executive function, in fact, primarily emerged from studies on the language acquisition of preschool children (Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2000). After studies on symbolic and cross-domain representations in preschool children, Bialystok inquired into the second-language acquisition of children, questioning whether a critical period for language acquisition exists and if bilingual children experience more controlled, effective processing (Hakuta et al., Reference Hakuta, Bialystok and Wiley2003).

Successive studies moved to adults and questioned whether the effect persists in adults and could contribute even to cognitive reserve in older adults. For example, Bialystok et al. (Reference Bialystok, Craik, Klein and Viswanathan2004) conducted three studies that compared the performances of bilingual and monolingual middle-aged and older adults on the Simon task. Older bilingual participants particularly had smaller costs for both age groups and also performed better under working memory demands. Older bilinguals are suggested to have greater resistance to age-related losses in executive function, an advantage that is interpreted as a larger cognitive reserve.

Studies on attention among young adult multilinguals contribute as well. Costa (Reference Costa2009) in their study employed the attentional network task (ANT) that taps into alerting, orienting and executive control. Bilinguals showed reduced global reaction times, but were especially better at utilizing alerting cues, as well as resolving conflicting information. They also displayed a reduced switching cost between different trials. Another study by Costa (Reference Costa2009) exemplifies this literature. Bilingual and monolingual participants had to attempt two versions of the flanker task, the first being more lower demand (incongruent and congruent trials largely separated) and the second demanding high monitoring (incongruent and congruent trials presented in succession). Previously mentioned studies all made a case for how bilinguals overall resolve conflicts much faster, but significant advantages here were only seen in the high-monitoring version of the task, suggesting that the advantage could be specific to rigorous monitoring requirements.

1.3. Lack of consensus and contradictory evidence

The above studies form part of the research that firmly implies balanced proficiency bilinguals carry over their linguistic advantage at controlling attention into non-linguistic domains as well. However, questions regarding the specifics of such an advantage and its mechanisms are not off the table. The hypothesis about bilinguals having to ‘keep track’ of both languages in order to select the more appropriate one might prove insufficient. No consensus exists for bilingual superiority on executive functioning, linguistic performance, or even creativity. Lehtonen et al. (Reference Lehtonen, Soveri, Laine, Järvenpää, de Bruin and Antfolk2018) conducted an extensive meta-review comprising 152 studies and an overall 891 comparisons and moderating variables to conclude that no systematic bilingual advantages exist across the examined bilingual populations, cognitive domains and tasks. The review places considerable responsibility on the practice of cherry picking variables for published studies. The meta-review found very small advantages for inhibition, shifting and working memory (none for monitoring and attention), and these disappeared after controlling for publication bias. A small disadvantage was also found in bilinguals’ verbal fluency, perhaps owing to the lack of exposure to each individual language.

This result is not new; bilinguals have been reported earlier to have inferior performance in verbal tasks. For example, an earlier study by Bialystok and Viswanathan (Reference Bialystok and Viswanathan2009) investigated response suppression, inhibition and cognitive flexibility among culturally diverse groups of 8-year-olds – monolinguals and bilinguals in Canada, bilinguals in India. Bilingual children were better at inhibition and cognitive flexibility but worse at verbal proficiency. Lexical interference from the other language has also been attributed as a cause. A suspicious irony presents itself when some evidence suggests that the bilingual experience appears to have its greatest benefit on non-linguistic processing and its greatest cost for language production.

Studies have examined other contingencies as well. Older adults seem to have the most pronounced effects, and advantages are fewer for young adults at the peak of their cognitive functioning (Lehtonen et al., Reference Lehtonen, Soveri, Laine, Järvenpää, de Bruin and Antfolk2018). The general reasoning provided here is that multilingualism can attenuate normal, age-related executive function decline. Since the advantages seem to follow from prolonged multilingualism, individuals with lower ages of Ln acquisition also show larger advantages. Practice effects also significantly reduce the extent of bilingual advantages; such reductions happen over the course of an experiment, between groups and are also slower in older participants (Hilchey & Klein, Reference Hilchey and Klein2011).

Working memory and recall also seem to be modulated, although it is a less investigated relationship. The introductory study on working memory updating was conducted by Soveri et al. (Reference Soveri, Rodriguez-Fornells and Laine2011), revealing that the efficiency of executive control decreases for older adult bilinguals, who made more errors compared to younger ones. In a separate meta-review of 27 studies by Grundy and Timmer (Reference Grundy and Timmer2017), a greater working memory capacity for bilinguals over monolinguals was supported by a medium to small population effect of 0.20.

To summarize the largely scattered evidence in terms of cognitive function, studies investigating language proficiency and lexical retrieval show bilingual deficits in their representational base and efficiency. For studies of executive control, bilingual advantages are more apparent throughout the lifespan and are said to contribute to a more robust cognitive reserve. Recall and working memory studies are the most equivocal on bilingual and monolingual performance.

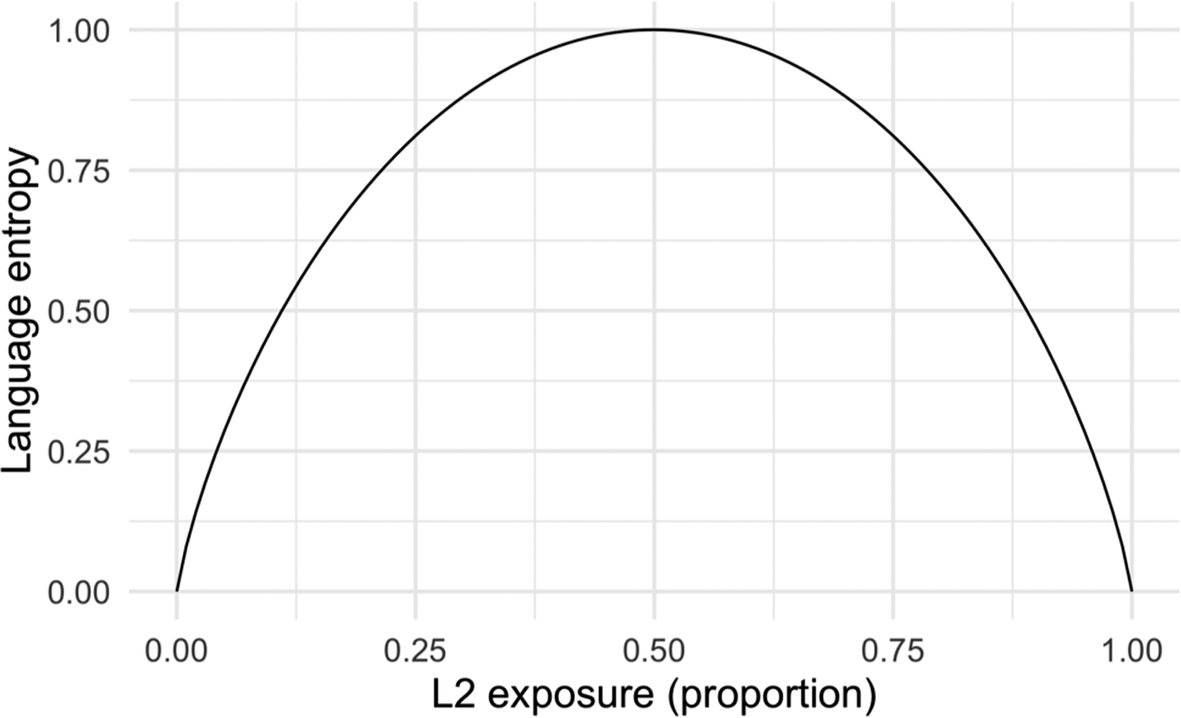

1.4. Accounting for multiple dimensions of language experience

This pervasive effect of language diversity across social contexts has been quantified by the measure of ‘language entropy’. Language entropy is a sensitive measure of calculating the relative diversity or balance in language use and exposure across social contexts. Lower values indicate an increased certainty about when a particular language has to occur in a certain context, while higher values indicate increased uncertainty (Gullifer Jason & Titone, Reference Gullifer Jason and Titone2018). The concept of entropy was first used in physics and information theory; it refers to a measure of uncertainty and diversity when some other proportion of ‘states’ is known. For example, if one were to speak Hindi with their family, English in their classroom and switch between both when with friends, home and classroom would be low entropy contexts and gathering with friends will be very high entropy. Individuals with low entropy are said to compartmentalize their languages and individuals with high entropy are said to integrate their languages by using multiple in one context (Gullifer Jason & Titone, Reference Gullifer Jason and Titone2020).

The language entropy measure was first used by Gullifer Jason and Titone (Reference Gullifer Jason and Titone2018) in their study on French–English bilinguals in Montréal, Canada. The study foregrounds the practice of assessing quantitative experimental data as a continuous variable, avoiding the dichotomization of speakers as monolinguals/bilinguals/multilinguals to increase nuances within the same set of speakers. The authors utilize the AX-CPT to test whether the individual differences in language experience from 400 bilinguals and multilinguals would predict engagement of certain proactive control processes. Despite scepticism on the basis of overfitted models, increases in entropy (as well as functional connectivity in the anterior cingulate prefrontal cortex for the same population) seemed to be correlated with increased reliance on proactive control. The results were largely in line with the prediction from the adaptive control hypothesis, suggesting that bilinguals with high general entropy could have adapted to the cognitive demands of active goal maintenance required to manage conflict.

1.5. Research questions

Importantly, an increasing amount of literature is converging on the idea that the presence or absence of bilingual advantage depends greatly on the specific contexts the bilingual lives, and the switching and language demands these contexts pose on them. The paper’s aim is to work upon this shift in the body of research, Ahmedabad, making a very interesting case for investigation due to its diverse linguistic environments. Most native residents speak both Gujarati and Hindi. If one has migrated to the city, they may also speak the language of the region they belong to, for example, Malayalam, Telugu, Punjabi and so on. Learning English is also posed as a requirement in primary, secondary and higher educational settings, with the prevalence of speakers being widespread.

Newer approaches suggest that variation across samples and conditions in executive functioning research may not be noisy and deviant; rather, this variation contains signals within the noise (Beatty-Martínez & Titone, Reference Beatty-Martínez and Titone2021). Overall, questions have emerged on whether multilinguals who are exposed to more linguistically varied contexts are affected differently from those who are exposed to more homogenous linguistic contexts, where the speaker is more certain about the languages and conversations that may crop up. The current work intends to examine the relationships between bilingualism and executive functioning by calculating participants’ language entropy scores. The executive functioning variables focus on proactive control performance through two experimental designs. The work is less interested in solidifying claims about individual differences among multilingual speakers on the basis of their executive control performance. The participants make up less of a unit of analysis than their specific patterns of language use. Moving past the individual also allows us to understand effects on context-general cognitive control information.

First, the present study intends to analyse the entropy score as a fitting descriptor of the language use patterns of multilingual undergraduate students. Second, the experiment expects a positive correlation between entropy scores and the performance on attention and working memory tasks, owing to the context-required switching. The expected increase in entropy scores for such a context is also expected to show improved AX-CPT and n-back measures. Results notwithstanding, the study will establish the usefulness of the entropy measure in a multilingual environment with potentially greater noise, when previously it has only been used to characterize bilingual environments. This will also be achieved by comparing entropy to the more traditional measures of proficiency, exposure and acquisition to see which exhibit greater predictive power over current language use. In previous work, entropy is also compared to age of acquisition and current exposure measures; it more accurately predicts characteristics like L2 accentedness and L2 abilities (Gullifer Jason & Titone, Reference Gullifer Jason and Titone2020). Due to the versatility of entropy results in previous literature (Li et al., Reference Li, Ng, Wong, Lee, Zhou and Yow2021; Van den Berg et al., Reference Van den Berg, Brouwer, Tienkamp, Verhagen and Keijzer2022), we hope to also see a meaningful connection in regards to the attention and working memory tasks here.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The target population (N = 56) comprised undergraduate university students who all spoke English. Additionally, they could speak Gujarati, Hindi, or all three. The composition of participants’ first languages is – Gujarati (n = 16), Hindi (n = 14), English (n = 12), Kannada (n = 1), Marathi (n = 2), Tamil (n = 1) and Bengali (n = 1). Additionally, participants also reported speaking Sindhi, Sambalpuri, Assamese, Urdu, Mandarin, French, German, Punjabi, Marwari, Telugu and Haryanvi. Participants spoke 3.54 (SD = 1.03) languages on average during their day-to-day. The ages at which they acquired English specifically were much more varied (M = 3.83, SD = 3.53). Each participant provided a detailed assessment of their language history and self-reported fluencies. Before participating, all individuals gave their informed consent to attempt the tasks. They also consented to the storage and analysis of the data collected from their questionnaire and experiment attempts. The Ahmedabad University Ethics Committee approved this research.

2.2. Apparatus and stimuli

2.2.1. Language history and background questionnaire (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Mak, Keyvani Chahi and Bialystok2018)

It has been difficult to generate consensus on how to best measure one’s current language experience, the need for standardization being quite urgent. This is especially true when bilingualism is not treated as a dichotomous construct and a heterogeneous population of participants is sampled. The LSBQ yields the extent to which an individual speaks one or more languages in 25 different micro-contexts. The first section gauges social background through place of birth, age and education. The second section is language background, participants are asked for details about how many languages they speak, when they learnt each of them (AoA), where they learnt it and if there were any periods in their life where they ceased using it. The self-reports on proficiency in each language are also included here. Third, Community Language Use Behaviour gathers information on languages used in different life stages (infancy, preschool, primary school, etc.), with different interlocutors (friends, grandparents, roommate, etc.), in different contexts (home, work, school) and miscellaneous activities (reading, watching movies, writing lists, etc.). Entropy measures were calculated from each of the contexts within community language use.

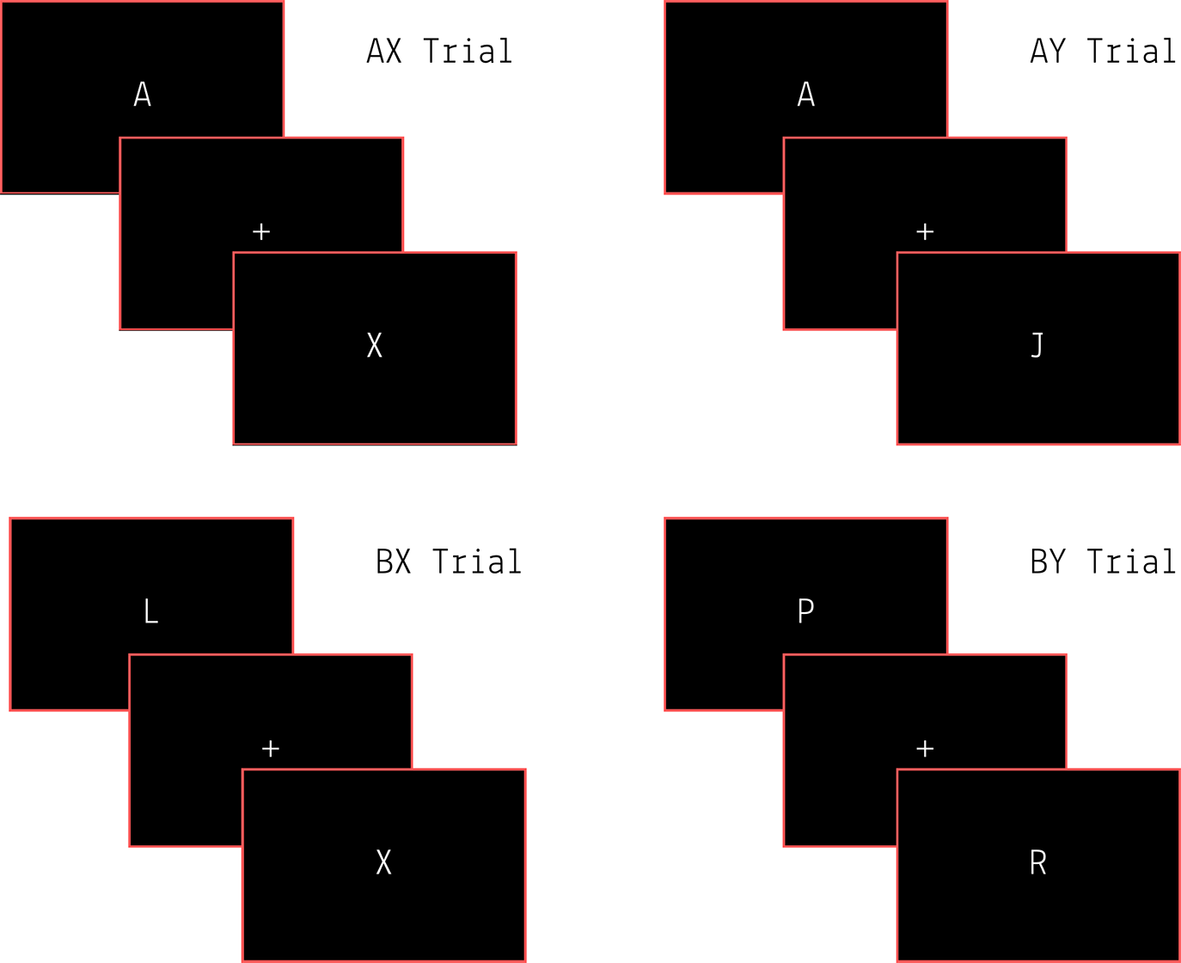

2.2.2. AX-continuous performance task

The AX-CPT was programmed in Psychopy (Peirce et al., Reference Peirce, Gray, Simpson, MacAskill, Höchenberger, Sogo, Kastman and Lindeløv2019) and worked at four different task levels: AX Type (60%), AY Type (20%), BX Type (10%), BY Type (10%) (see Figure 1). English letters were presented serially in the centre of the screen. Participants were required to monitor for the letter A (cue condition) and look out for when it was immediately followed by the letter X (probe condition). The A-X pairing required them to provide feedback with a keypress; pressing on any other pairing of letters would be a false alarm. They were also instructed to respond as quickly as possible. Each trial consisted of 10 letters presented for 150 ms each, with an inter-trial break of 2000 ms. Every participant went through 150 trials, and the proportion of different task levels was constant for each individual.

Figure 1. All four conditions of the AX-CPT task.

Language entropy and the effects of interactional contexts have been assessed with the AX-CPT for most studies (Gullifer Jason & Titone, Reference Gullifer Jason and Titone2018; Gullifer & Titone, Reference Gullifer and Titone2021; Bialystok & Barac, Reference Bialystok and Barac2012). Its most important feature would imply a distinction between proactive and reactive control – behaviour driven from internal control processes versus externally salient stimuli (Braver, Reference Braver2012; Gonthier et al., Reference Gonthier, Macnamara, Chow, Conway and Braver2016; Mäki-Marttunen et al., Reference Mäki-Marttunen, Hagen and Espeseth2019). Proactive control is also contained to attentional and working memory capacities, making it less susceptible to influence from the environment. Whereas reactive control would require one to monitor for and resolve environmental interference in time. Proactive control is always engaged to monitor for the cue condition, reactive control is engaged at the presence of the probe condition – although this is subject to some nuance based on whether these processes are thought to be ‘independent’ or ‘continuous’ with each other. Multiple task levels also allow for them to be delineated, for example, error for an AY type likely characterizes proactive control and error in a BX trial would characterize reactive control. Peak cognitive performance would require a balancing act with both. Gullifer Jason and Titone (Reference Gullifer Jason and Titone2018) employed the AX-CPT in their first investigation, with entropy – trials requiring proactive control were associated with lower reaction times (RTs), whereas trials requiring reactive control instead showed no improvement in RTs.

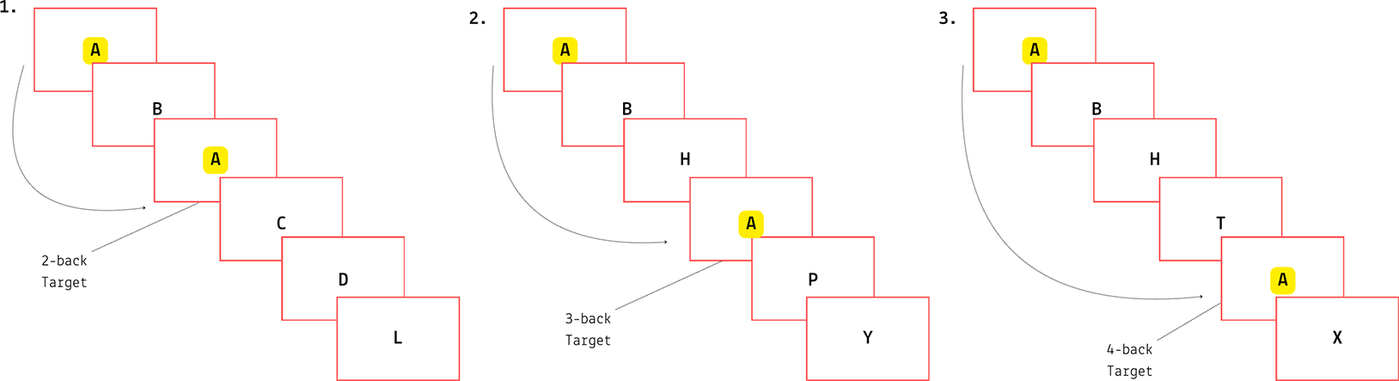

2.2.3. n-back task

The n-back task load is very easy to modulate – each level requires that information to be actively maintained in working memory, and different difficulties also engage different degrees of content processing and cognitive control processes (Kirchner, Reference Kirchner1958; Pelegrina et al., Reference Pelegrina, Lechuga, García-Madruga, Elosúa, Macizo, Carreiras, Fuentes and Bajo2015). The n-back test is also a recognition test, carrying elements of recollection and familiarity. The internal reliability of the test (measured by accuracy and reaction time scores) has mixed support; some claim it is highly reliable (Hepdarcan & Can, Reference Hepdarcan and Can2025; Hockey & Geffen, Reference Hockey and Geffen2004) and some do not consider it reliable enough to be a measure of individual differences (Jaeggi et al., Reference Jaeggi, Studer-Luethi, Buschkuehl, Su, Jonides and Perrig2010a). Despite this, there remains a precedent for its experimental usefulness; the task has advantages over other tasks for being able to reflect the updating aspects of working memory (Wilhelm et al., Reference Wilhelm, Hildebrandt and Oberauer2013), attentional control (Grundy & Timmer, Reference Grundy and Timmer2017) and working memory capacity (Pelegrina et al., Reference Pelegrina, Lechuga, García-Madruga, Elosúa, Macizo, Carreiras, Fuentes and Bajo2015). More recently, the task has been robustly used in neuroimaging (primarily, fMRI) research on age-related changes in working memory and cognitive functioning (Yaple et al., Reference Yaple, Stevens and Arsalidou2019).

For this particular study, the simplicity of the task makes it a useful companion to AX-CPT results.

This task was also programmed in Psychopy and worked at three levels of difficulty: 2-back (60%), 3-back (20%), 4-back (20%). English letters were updated as task material, presented serially in the centre of the screen (see Figure 2). Each trial consisted of 11 letters presented for 150 ms each, with an inter-trial break of 2000 ms. For the repetition of a letter that appeared n-steps ago (n according to the trial condition), the participants were instructed to press the left arrow key. Participants were instructed not to press any key in the absence of such a repetition. Response times and accuracy (hits, misses, false alarms) were recorded. The entire task was also preceded by a practice block that consisted of 10 trials.

Figure 2. All three conditions of the n-back task. From left to right: 2-back version, 3-back version and 4-back version.

2.3. Data analysis

2.3.1. Language entropy (Gullifer Jason & Titone, Reference Gullifer Jason and Titone2018; fully documented R package)

Entropy is a measure that turns its attention to variables that are often measured but not entirely evaluated. It indexes the relative balance and diversity in daily language usage – higher values relate to more balanced language use and greater diversity (Gullifer Jason & Titone, Reference Gullifer Jason and Titone2018). This diversity can occur across locations such as classrooms, workplaces, etc., and also among individuals. Multilingualism is the norm in most of India, but especially in regions that do not predominantly speak Hindi. Gujarati forms its own rich linguistic and literary culture in Ahmedabad, taking its place as the most dominant language.

Formula for Shannon Entropy (H). n is the total number of languages (here min = 2, max = 5) in a certain context. Pi refers to the proportion with which a language is used in that context.

The Likert scale and percentage data from the LSB Questionnaire are converted to entropy scores by using the formula for Shannon entropy (H). To provide an example, if a participant (n = 2) reports using Gujarati for 60% of the time and Hindi for 40% of the time when at home, the entropy value would be attained by summing up 0.60 × log2(0.6) and 0.40 × log2(0.40). This value will be negative and has to finally be multiplied by −1 to yield a positive score. The hypothetical entropy for this participant’s home context would be 0.97. This is a very high value (nearly half and half), indicating a high amount of uncertainty about which language to use in a certain context. Theoretically, the lowest an entropy value could go would be 0, occurring when only one language is used in a context (proportion value = 1.0). The distribution itself varies based on the number of languages accounted for; when three languages are considered, its maximum value would be about 1.585 (log3, n = 3) – this would represent a completely integrated context where all three languages are used equivalently (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Theoretical distribution of compartmentalized/integrated language use when using entropy (Gullifer Jason & Titone, Reference Gullifer Jason and Titone2018). Here, two languages are considered so that the X-axis ends at 1 (log(number of languages, base = 2)).

3. Results

The majority of participants reported having acquired English at 3 years of age, the age at which most children begin preschool and are required to learn a language they may not be exposed to at home. This is exceedingly common in most Indian cities, where the language spoken at a toddler’s home is usually Hindi or the most regionally dominant language. English is the constant among all participants, and is employed to better document proportions in which the speakers’ languages emerge in different contexts. For example, measures of frequency regarding English speaking, writing and reading will later provide more information about how a speaker uses different languages for either of these three activities.

3.1. LSBQ to entropy

The LSBQ yields 26 potential micro-contexts from which entropy values could be calculated. The scales on the LSBQ measure language use for both languages on a single scale, but the scales used to measure language entropy assess the use of each language individually. Additionally, multilinguals were accounted for in each context. For example, on one scale, participants indicate their language use with parents from ‘Always English’ (1) to ‘Always Non-English’ (5). To calculate the proportion of each language, the reported usage in the non-English language was subtracted from 100 to determine the value for English use (25%). All percentage values were converted to proportions (0.25 in this case) before proceeding. The remaining 75% was divided by the number of languages spoken by the participant, subtracted by one. For a bilingual, L2 would remain 75%, but for a trilingual, it would be split to 37.5% for L2 and 37.5% for L3, and so on. Participants also reported qualitative data on discontinuing certain languages or not using them conversationally, and such languages were excluded from the calculations. The mean entropy values among contexts ranged from 0.07 (emailing) to 0.93 (primary school). By comparison, the reported mean entropy values across contexts in university students ranged from 0.60 to 0.94. The complete list of values is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Mean, std. deviation of each entropy micro-context

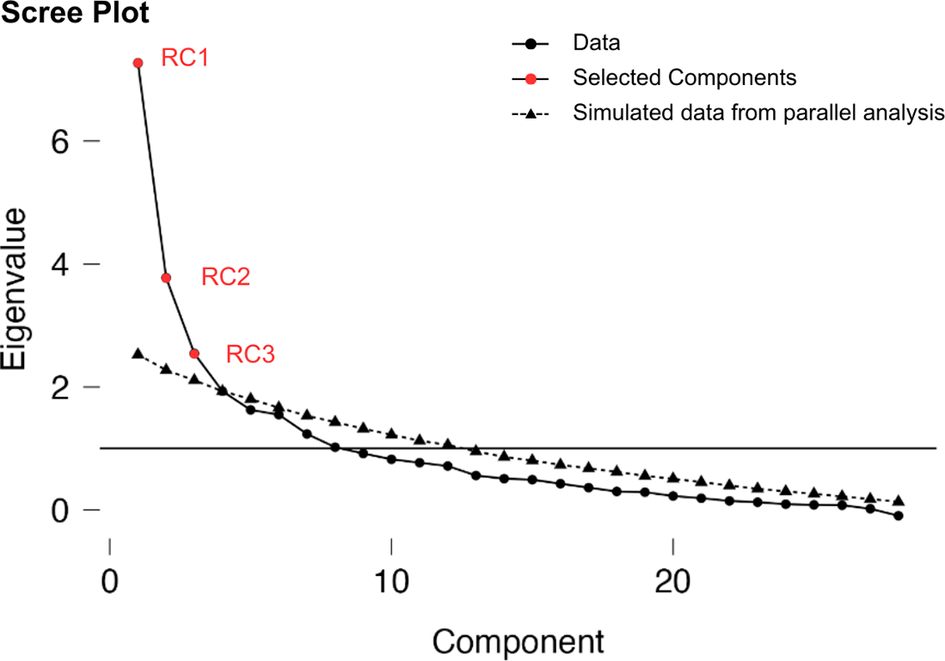

3.2. Factor analysis and correlations

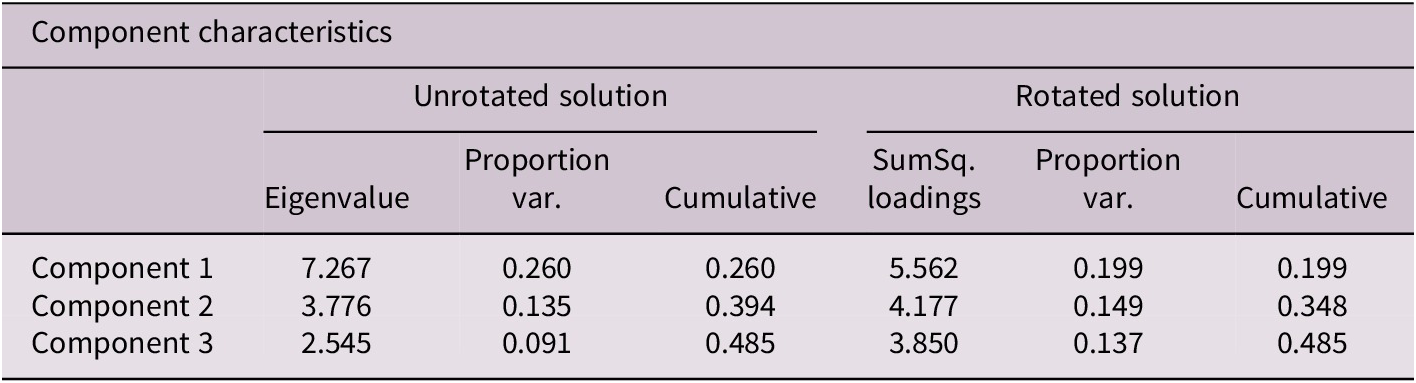

To reduce the complexity of the data, a principal component analysis (PCA) using JASP was conducted (JASP Team, 2024). First, the entropy values were inspected to examine the amount of missing data for each microcontext. This revealed that there were significant missing data for two contexts – Partner (40%) and Praying (18%) – as many participants either did not have a partner or did not pray. These micro-contexts were excluded from the PCA. All other missing data were not imputed, but rather excluded pairwise in JASP since missing values were small and random.

Three components were extracted from the PCA, as determined from the scree plot (see Figure 4 and Tables 2 and 3). Variables related to language use at home and other social settings (removed from university) loaded onto one component and explained 26% of the variance, so Factor 1 is called ‘Social Language Use’. Variables related to home use of language loaded onto the second component and explained 13.5% of the variance, so Factor 2 is called ‘University Language Use’. A final factor explains 9% of the variance and relates to miscellaneous writing and non-social language uses. Some cross-loading between the first two and last two components suggests that these factors are not entirely distinct. Values for these two factor scores were calculated for each participant and used to explore the associations between entropy, proficiency, AX-CPT and n-back task performance.

Figure 4. Scree plot for PCA, three components emerge as unique. Individual points stand for underlying components in the data. Simulated data are plotted for comparison; it comprises the components of a randomly generated dataset. RC1, RC2 and RC3 fall above the interject with the simulated data plot; they are selected as most useful for further analysis.

Table 2. Component distribution per each micro-context

Table 3. Component distribution per each micro-context

Note. Applied rotation method is promax.

3.3. AX-CPT

For the AX-trials (N = 3542), participants responded correctly for 70.78% of the trials and missed the target for 30.82% of them, overall accuracy being 66.3%. The highest percentage of false alarms occurred in the BX-trial type (N = 120) at 14.16% of the trials. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to confirm the trial type effects across participants. Trial type effects on accuracy were significant, F (3, 57) = 164.67, p < .001. The ANOVA on reaction times did not indicate a significant effect of trial type F (3, 57) = 0.315, p = .815.

A multiple linear regression was conducted to examine the association between the two entropy factors and performance on the AX-CPT. No significant correlations were found between either social or university entropy factors and accuracy or reaction time for any of the trial types, rs < .1, ps > .08.

3.4. N-back task

The same one-way ANOVAs were conducted for 2-back, 3-back and 4-back type effects on reaction times and accuracy. There existed a significant difference in task load on accuracy, F (2, 57) = 43.61, p < .001 – the percentage of hits being 52.13%, 44.95% and 51.23% respectively. False alarm percentages were most consistent – 21.75% for 2-back, 35.59% for 3-back and 52.15% for 4-back. Reaction times were also significantly different for each task load, F (2, 57) = 11.442, p < .001. Multiple linear regressions for each level of task load were run across the three entropy components, but none of the models significantly explained accuracy or reaction times. In all cases, p remained >.001.

4. Discussion

Multiple linear regression analyses reveal that the age at which participants acquired English is not significantly related to the frequency of English and first language usage, English speaking being the only exception (p = .03, adjusted R 2 = 0.120). The frequency of writing, reading and listening in English or any other language is not predicted by how early one acquired English. Most participants in the study had largely begun learning English as soon as they started school (n = 56, mean age of acquisition = 3.83); only five participants had acquired English at later stages in schooling, despite learning multiple other languages from infancy (n = 10, mean age of acquisition = 9.85). As it stands, the data from these five participants do not contain enough variance to be adequately run through a parametric test like linear regression. The size and thinness of the sample for participants with higher AoAs also make it so that the data do not fulfil normality functions. For instance, only two participants acquired English at the age of seven, and two outlying participants acquired it past the age of 15.

More analysis of age of acquisition measures with current language measures, such as language switching at work, home, school and so on, pre-empts that static, historical experience for a language is less important than more dynamic measures. Switching measures for different participants also pertain to how two or more languages are utilized in the same sentence or phrase. This is especially important data when looking at dense switching contexts where most people speak two or more languages; many social contexts in Ahmedabad are such. It is also worth paying attention to the fact that all participants in the study navigate an English-speaking university environment on a daily basis, where classrooms and formal communication are exclusively handled in English. From 1 (all the time) to 0 (never), switching is most common with friends (mean = 0.771, SD = 0.217) and least common in educational settings (mean = 0.403, SD = 0.312). Lexical selection models meet the self-reported values to imply that bilingual language production is not particularly effortful and switching in more naturalistic environments would greatly eliminate performance costs and cognitive demands (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang2015; Adamou & Xingjia, Reference Adamou and Xingjia2017; Blanco-Elorrieta and Pylkkänen, Reference Blanco-Elorrieta and Pylkkanen2017; Kaan et al., Reference Kaan, Kheder, Kreidler, Tomić and Valdés2020). Even with high entropy values observed, what seems to matter most is the nature of the switching environment. Forceful switching in laboratory environments has been proven to be more costly than naturalistic switching; our observations also seem to better fit the cooperative model of language over a competitive one.

Current entropy values for three out of five contexts had no bearing at all on the self-reported amount of switching in those contexts. The only contexts where entropy values significantly explained switching patterns were with parents and family, and on social media. It also seems significant that while students found themselves speaking mostly English in their current work and university context, entropy did not necessarily predict switching in these environments. Entropy measures from further in the past also do not predict the amount of switching at work, educational settings and among friends, despite educational settings being quite fundamental modulators of how students have employed their languages.

Although the simple exposure values explain variance, entropy values may still provide more nuanced explanations for the same. For instance, switching with parents and family is significantly predicted by entropy values with parents (adjusted R 2 = 0.253, p value = .04) and entropy with siblings (adjusted R 2 = 0.253, p value = .01). For data with more variance, more robust connections can likely be in store. Regardless, entropy seems to develop a better fit compared to more traditional information on proficiency, exposure and acquisition. Even though it requires more up-front engineering than an exposure value, it more surely points to the relative balance between one’s languages rather than any number of confounded variables (Gullifer Jason & Titone, Reference Gullifer Jason and Titone2020).

The number of languages that are part of the participant’s repertoire also predicts switching patterns and reveals interesting environmental constraints and patterns of usage. Which language in particular is not statistically significant for any predictive analyses of switching or entropy measures? But with each successive increase in the number of languages spoken, strong negative and positive predictions about entropy begin emerging stepwise. The number of languages spoken explains the variance (all values adjusted R2) in entropy for up to 89% in extracurricular (hobbies, leisure activities) settings, 79% in the educational settings, 76% in browsing the internet, 76% in writing miscellaneous lists, 75% in watching movies, 70% in reading, 70% in interactions over text, 69% in general media consumption, 65% in engagements on social media, 64% in interactions with friends, 46% in interactions with parents and, 36% in general interactions at home (all p values < .001). Most importantly, the interaction of entropy with the number of languages spoken is not as straightforward as it seems – in most contexts, people switching between only two languages experience the highest entropy and this tapers off with each successive language added to the mix (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Plotting all the switching values with 1. parents and family, 2. friends, 3. work, 4. educational settings and 5. social media. Colours indicate entropy values for each context, red indicating high entropy and blue indicating low entropy. Interestingly, entropy values do not increase with the increase in the number of languages spoken; bilingual speakers maintain the highest entropy values.

To take an overview of these results: language entropy surpasses other measures when modelling diversity among bilingual language use only. Previous studies, including Gullifer and Titone’s (Reference Gullifer and Titone2021) recent work, only work with bilingual populations – this doubtlessly makes for a cleaner experimental model. Turning the attention to any one theoretical predictor of entropy measures, such as uncertainty or language balance or code switching, makes models quite complicated. Different covariates can emerge and be controlled, for example, looking at language balance would require controls for L2, L3 and Ln exposure measures as well. This becomes an even wider net when considering multilinguals over bilinguals. But the results from this paper can provide additional impetus to model more experiences from more diverse linguistic backgrounds on the basis of entropy.

The line of reasoning also contributes to why the language and analysis emerging from LSBQ and entropy measures revolve primarily around the current English usage of participants. Identifying each participant’s native language increases the splintering of the analysis from an already small group of participants. Establishing a certain level of language proficiency for each language in the current group of participants is a difficult task in itself when working with self-report measures. Instead, a common context of intensive English language use, that is, the University, is identified, and other variables are measured against it. The likelihood of the creation of more unifying, generalizable models certainly increases. Larger and more heterogeneous samples could more easily provide models divorced from any one particular language of interest than the ones gained from this study.

Another aspect of language use that remained largely untapped due to the above methodological restraints was proficiency measures. Self-report proficiency measures remain difficult to reliably associate with executive function measures (Tomoschuk, Ferreira, & Gollan, Reference Tomoschuk, Ferreira and Gollan2019), but do provide insight into self-perception of proficiency. The relationship between self-perceived proficiency and other patterns regarding exposure to the language in question, or where this language is primarily encountered in the day (the home or at work, for example), could open up more urgent social lines of correlation.

The results do not manage to escape an existing tendency in bilingual research that provides strong supporting evidence but null results in relation to executive function parameters. The present study attempted to delineate bilingualism parameters based on the language entropy measure, but the effects of the same are mostly absent. The measure proves useful at characterizing a dynamic and diverse linguistic environment, despite the unique linguistic environment of Montreal being quite different from Ahmedabad.

The language entropy values in Ahmedabad were the highest among previous studies in Toronto (dual context; Wagner, Bekas, & Bialystok, Reference Wagner, Bekas and Bialystok2023) and Montreal (single context; Gullifer & Titone, Reference Gullifer and Titone2021), making a considerable case for it being considered a ‘multiple language context’. The values ranged from 0.073 and 0.935, confirming that switching between languages in Ahmedabad is very contingent on the particular context looked at. Language selection choices can only be made when permitted by the larger context, but the language entropy function itself mainly conceptualizes individual behaviour in language use contexts (Bialystok and Wagner, 2023).

The major theoretical framework that connects speech comprehension and processing with cognitive control processes is Green and Abutalebi’s (Reference Green and Abutalebi2013) adaptive control hypothesis. This hypothesis is the first to identify and differentiate between the several real-world interactional contexts that directly shape an individual’s language control processes. These are single language, dual language and dense code-switching contexts.

Simplistically, the ACH holds up in Montreal, such that switching is high and cognitive function is improved, as well as in Toronto, where switching is low and cognitive function is not affected whatsoever. Although neither finding is exactly the case here, Ahmedabad is similar to Toronto in that language choice is not often a matter of personal preference, but public spaces and institutions will privilege the use of English. Both cities also privilege English-speaking minorities in the city to be investigated – the individual is acted upon by sociocultural forces, being compelled to speak in a certain language (Titone & Tiv, Reference Titone and Tiv2022). A systems framework and an emergentism framework (Claussenius-Kalman et al., Reference Claussenius-Kalman, Li and Hernandez2021; Titone & Tiv, Reference Titone and Tiv2022) propose that the outcome of bilingual processing and representation has to be paid more attention to in light of the sociolinguistic and sociocultural experiences. Unlike what the hypotheses suggested, simply looking at the presence of diversity may not be sufficient; the nature of these micro-contexts may be more important. Evidence from the present work may not be useful in providing larger claims about ACH or lexical selection models; rather, its usefulness seems to lie most squarely in describing how entropy measures interact with a uniquely multilingual population and setting.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in LSBQ & Experimental Data.

Competing interests

The authors confirm that there are no competing Interests to share.