My boy Jack had another touch of Ague about noon. Gave him a dram of gin at the beginning of the fit and pushed him headlong into one of my Ponds and ordered him to bed immediately and he was better after it and had nothing of the cold fit after, but was very hot.

(Diary of a country parson, 22 May 1779).Footnote 1

Parson Woodforde’s serving boy was one of a small army of children in eighteenth-century England who had made the transition from their biological family or institutional home to live and work in a new household, often at a very tender age. Parson Woodforde was guided by a sense of obligation to his young servants; his remedies, if unscientific, were well intentioned and generally harmless. Nor were all homespun remedies lacking in scientific guidance. Elizabeth Shackleton’s ‘genteel housekeeping’, for example, included a fund of knowledge about medical remedies informed by exchanges with qualified medical men and regularly applied to for family, friends and servants alike.Footnote 2 Many children, however, could not be sure of any such care or attention. Given the vagaries of eighteenth-century medicine and the unregulated medical practice of the day, the neglect which followed might have amounted to a lucky escape. Others could be victims of experiment, ill-informed medical practitioners or the ‘makeshift’ resources of straitened economic circumstances.

The aim of this article is to extend our knowledge and understanding of the health of child workers in eighteenth-century England. It focuses on the little examined area of the experience of young people who fell ill when living and working in the households of those who had apprenticed or hired them. Who was considered responsible for the care and cost of a sick child who was living and working in a household that was not their accustomed home? The apprenticeship indenture, which promised the apprentice the basics of everyday life, made no explicit reference to illness, and mention of illness was rare in private arrangements. How did various agencies, including the parish, charities and individual masters and mistresses, respond to the problem and with what consequences for the young person?

Margaret Pelling has observed that while historians have given much attention to child mortality, little more than ‘anecdotal notice’ was given to the care of children when ill or to the perceptions of the young people themselves when undergoing such experiences.Footnote 3 Her own work gives special attention to illness of children and young people largely in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but her approach informs studies of apprentices in later periods, notably her observation that by examining young people ‘outside the circumscribed context of family and family relationships’, we more easily see them as individuals or their relationship with society as a whole.Footnote 4 Recent historians of apprenticeship and child labour have given new attention to the health and welfare of young workers during the industrial revolution.Footnote 5 Peter Kirby’s important study of the health and welfare of the child workforce in Britain considers children involved in factory, mill and mine work, for which, in many cases, fairly abundant sources exist in the form of parish registers, factory records, inspection reports and the accounts of contemporary observers. Kirby, however, laments the absence of comparable studies for more traditional areas of children’s work including domestic service, agriculture and workshop production, which arises in part from the problems and inadequacies of the sources available.Footnote 6 Although R. C. Richardson provides examples of good and bad treatment of sick household servants, sources for children’s experiences are few.Footnote 7 That said, the records of many charity institutions are valuable sources for the lives of young workers placed out by their officials. Two recent studies by Alysa Levene and Helen Berry use the detailed and extensive archive of the London Foundling Hospital, the governing body of which maintained contact, where possible, with the foundlings they placed out, or at least responded to problems that arose. They include close examination of many of those who subsequently fell ill in households involved in different occupations.Footnote 8

The attempt to penetrate beyond the closed doors of individual households presents problems for the historian, lacking the sources more readily available to investigators into factory and mill work. Evidence is taken from court cases, private correspondence, household accounts and manuals, autobiography and diaries, poor law and charity records, particularly those of the London Foundling Hospital and the Birmingham Blue Coat School, to demonstrate the range of responses to apprentices and other living-in child workers who fell ill. A few writers of autobiographies have left accounts of their own experience of illness when living and working in households away from their own families. As Jane Humphries shows in her study of child workers in the industrial revolution, such accounts need careful interpretation and analysis but may bring us closer to discovering how the child workers ‘themselves understood their suffering’.Footnote 9 The focus here is on the south and midlands of England, but urban and rural households are included to extend the range of experience covered.

The study begins with a consideration of the numerical significance of this workforce during the eighteenth century and what safeguards existed for their well-being. It will examine the implications of the falling age of apprentices and young workers in this period and consider the sense in which the nature and character of the institution of apprenticeship changed. How did these developments affect the lives of these young people when they fell ill? The impact of severe outbreaks of smallpox in this period will be examined and the extent to which these highlighted the wider question of illness and created new tensions for relationships between the young worker and the host household. The policies of the parish, the London Foundling Hospital and the Birmingham Blue Coat School are compared and contrasted. The article concludes with an examination of the experiences of children and young people who fell ill in a range of household occupations.

There is general agreement that, by the eighteenth century, young living-in workers in England amounted to a significant proportion of the labour force and of the population as a whole. It is difficult to be precise about their numbers. Contemporary figures for different categories of workers are unreliable, skewed towards London, and best described as ‘heroic estimates’.Footnote 10 Humphries discusses the piecemeal nature of much of the evidence which survives, especially for non-poor law private apprenticeship. She finds general acceptance for the figure for male (non-agricultural) apprentices of between 7.5 and 10 per cent of the male population of England as a whole. There were, depending on the economy and occupations of an area, significant regional variations.Footnote 11 The vast majority of this cohort worked in the household of artisans to learn a skilled or semi-skilled trade. Domestic service accounted for many other living-in apprentices. The data of the Cambridge Group, a collaborative research body formed to study the population and social structure of England, indicates that household servants (which include young, old, male and female servants), formed 18.4 per cent of the population between 1650 and 1749 and 10.6 percent between 1750 and 1821.Footnote 12 Domestic service was an occupation characterized from the mid-eighteenth century by its predominantly young and female workforce. We can be sure that a substantial number of this group were girls and young women under the age of 21, assigned by poor law overseers, private individuals and charities to learn ‘housewifery’. A small but significant group were boys and young men sometimes placed with more affluent households as ‘house-boys’ and postilions. Young hired servants with contracts, lasting perhaps one to three years, were also likely to live in. In most cases, they too had moved to an unfamiliar household and environment. While at any one time only a minority of all children or adolescents were in household service or apprenticeships, these were ‘life-cycle’ experiences for a significant proportion of the labour force of the whole population in early modern England before they moved to greater independence.

Who were the young workers living in the households of others?

While apprentices might share a common identity, they lacked uniformity. Their experiences were influenced by their previous lives, the occupation they practised and the household into which they were received.Footnote 13 A hierarchy existed with apprentices assigned to masters belonging to the wealthy and powerful London guilds such as the Goldsmiths or Merchant Taylors at the top. Parents of such boys were likely to have spent large amounts of money to acquire these prestigious apprenticeships. The choice of master might have been the subject of long-standing discussion and consultation between friends and kin.Footnote 14 In London and other urban centres, parents of the ‘middling sort’ made their own private arrangements to place their sons, and sometimes daughters, into whatever trade, profession or household their income would allow. In Oxford in 1705, for example, Henry Robinson, a yeoman, placed his son Edward with a glover, Humphrey Wells. The premium is not given, but glove-making was a skilled occupation with some status.Footnote 15 What is striking in Oxford is the wide range of occupations from which, and into which, boys and young men might move to take up apprenticeships. In 1727, Thomas Sellar, son of a cordwainer, was apprenticed to Thomas Clanfield, a baker – a typical move in Oxford from a modest artisan or small shopkeeping family to the household of similar social status.Footnote 16 While personal conflicts might arise between household members and apprentice, social tensions were less likely. This may not have been the case for the 10 per cent of the sons of labourers who were apprenticed between 1697 and 1800. Many were the beneficiaries of Oxford charities, including the University Charity. Such charities were found in cities elsewhere, but pooling of family resources and payment by instalment also made it possible for the sons and daughters of poorer men to enter less prestigious trades.Footnote 17

Charities such as the London Foundling Hospital established by Thomas Coram in 1739 and the Birmingham Blue Coat School, which took in its first intake of children in 1724, placed a number of their pupils (boys and girls in the case of these two charities) into apprenticeships each year. While the officials could hardly exercise the same concern as a parent, they did give attention to the suitability of masters and mistresses and prepared their apprentices for life outside the institutions. A small number of foundlings were placed in wealthy, even aristocratic households, whose heads were sympathetic to the Hospital’s work. The masters and mistresses of most apprentices, however, were modest artisans or small-scale shopkeepers. These households gained prestige because they were judged to be financially stable and respectable enough to take a foundling apprentice. The Hospital gave no premiums – another safeguarding measure which aimed to attract a ‘better’ sort of master. Charity children did not generally enjoy a positive reputation but, in this case, considerable prestige was attached to the connection with the Hospital, enhanced by the reputation of the foundlings for integrity and hard work instilled during their time at the institution.Footnote 18 Much the same was true of the Birmingham Blue Coat School, which began as ‘the Charity School of Birmingham’ in 1724 but, because of the blue uniform worn by pupils, came to be referred to as ‘The Blue Coat School’. This was perhaps encouraged by the governors who were thereby making a link with the prestigious Blue Coat School in London, Christ’s Hospital. The Birmingham school was an exclusively Anglican institution, distinguishing it from rival non-conformist groups in the town.

At the bottom were the pauper apprentices for whom parish authorities were responsible. Recent research shows that overseers and vestry boards were by no means always so indifferent to the children’s care or destination as traditional accounts have claimed.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, many children had no parent who might influence their placement or subsequent treatment; where parents did exist, they had little power to influence the arrangements made for their child – or might face penalties if they did so. The enormous range of premiums underlines the discrepancy between apprentices: while masters with pauper apprentices might receive no more than a paltry sum of under £4, Daniel Jenkinson, in a private arrangement, paid a premium of £60 for his son Samuel to be apprenticed to a surveyor in 1790.Footnote 20 Sometimes pauper apprentices were taken reluctantly when overseers, under pressure from ratepayers to cut costs, were anxious to place them under the responsibility (and cost) of others. They were likely to be placed in overcrowded trades for which prospects were less promising and their presence resented. Such circumstances were hardly conducive to establishing caring concern for a child who fell ill.

What linked those under the loose ‘umbrella’ of apprenticeship was their youth and subordinate role in their designated household. They were also committed by the terms of their indenture to a lengthy period of unpaid labour, usually seven years. This term could vary depending on the age of the child when placed or as the result of a mutual agreement between master and apprentice, perhaps when the latter was deemed to have learnt the trade and the master had no more need of the young person’s labour.Footnote 21

In addition to these ‘official’ apprentices were numerous young ‘living-in’ workers who were contracted out by parents who could not afford the payment to apprentice a child even to a semi-skilled trade or did not care to do so. Records of the agreements which underlay such arrangements are scarce, but frequently resembled the terms of the apprenticeship indenture. They might be qualified or extended by local custom or by the particular practice of the household taking in the boy or girl. A crucial difference was that the indenture was a legal document to which a parent or sometimes an apprentice might appeal should a dispute over treatment or the provision of necessities occur. The legal position of such hired labour was much less clearly defined or certain than was the case for indentured apprentices.Footnote 22 At times no more than casual or verbal agreements existed and sometimes none at all. John Gibbs was only ten years old when he persuaded a genteel family to take him as their house-boy; he was clearly in no position to negotiate terms.Footnote 23 Living-in servants formed a less stable workforce: unlike apprentices, hired workers were, in most cases, free to leave usually after a year of working for the same employer. Many stayed for longer periods; parental pressure, the absence of alternative work and the ruling that ‘settlement’ could be obtained only in the parish where it had been earnt by one year’s hired work made it more difficult to move. Settlement – the right to obtain poor law relief in the event of unemployment, sickness or the burdens of old age – was much valued by the poor, as many pauper children knew from their own home lives. Those who did move on when still young might find work in a new household where again they lived in. Peter Rushton refers to ‘the wandering servants of rural households’ in northeast England.Footnote 24

These living-in servants were attached to a variety of households and might experience very different conditions. Rural householders of some means might prefer to hire local people. Reverend James Newton of Newnham Courtnay in Oxfordshire was an exacting master, but the boy servants who accompanied him on his rounds were well dressed and well fed, if only to maintain his image.Footnote 25 Others were less fortunate: by the mid-eighteenth century a struggling family might take on a young girl to work alongside the wife or to release a skilled family wage earner. Behind closed doors they might all go hungry together. All categories of living-in young workers might be trapped in what Rushton calls ‘the intensely claustrophobic atmosphere of personal relations in the domestic sphere of the pre-industrial age of manufacturers’ – tensions engendered by cramped and overcrowded living and working spaces.Footnote 26

Illness might occur to those in any category. Children and young people, even when fit when bound or hired out, fell ill with alarming frequency as numerous contemporary entries in diaries, memoirs and correspondence show. They were the most likely victims of virulent diseases and prone to accidents. Mary Lindeman observes that those surviving to adulthood ‘had often traversed a Job-like path of woes’, punctuated by episodes of vermin, parasites and skin ailments.Footnote 27 The treatment they received provides an insight into the health and welfare of young workers from both the middling sort and the poor when in the hands of those expected to be in loco parentis. Their experiences reflect the great variety of circumstances in which apprentices and young servants lived and highlight the sometimes-contentious question of who should care for them.

By the eighteenth century the daily lives of apprentices were affected by the commitment, on the part of those with whom they were placed, to feed, clothe and accommodate them. A further obligation was to provide training in a useful trade or occupation: in the case of girls placed for housewifery or ‘household business’, this would most often be undertaken by the master’s wife. These were the well-established ‘entitlements’ of the apprentice, laid down by the 1563 Statute of Artificers, written into the indenture and sanctioned by law.Footnote 28 From the mid-seventeenth century the indenture, in the case of more prestigious trades and institutions, was usually a standardized printed form the terms of which were largely formulaic. Pressure from parents or wider community concerns meant, nevertheless, that additional benefits were added from time to time. For example, the master or mistress was by this date usually expected to maintain reasonable standards of hygiene by arrangements for the washing of clothes; this addition reflected concern for the health of young workers and recognition that it was in the interests of all concerned for apprentices to be fit and well. This obligation had appeared slowly and incompletely. It might or might not include ‘Tailor’s board and thread’ – the mending of the apprentice’s clothing. Additional matters might have been agreed verbally or determined according to the particular needs of the young person or the occupation he or she was pursuing. Parents in Southampton, ambitious for their sons in a port trading overseas, for example, might arrange for them to spend time abroad in their master’s business or even, as in the case of John Maijor, ‘to be instructed in the said arte and the French tonge’. Hence, too, the highly practical obligation on the part of cordwainers to provide their apprentices with protective aprons.Footnote 29

What safeguards were there for an apprentice or young hired worker who fell ill?

What happened when such a child or young person fell ill in the household in which they were subject to the head of household? Clauses providing direction on medical care were unusual. Pelling found examples in the sixteenth century which committed masters to care for those bound to them ‘in sickness and in health’ – a phrase more often associated with the marriage service.Footnote 30 This may have been intended to impress upon both apprentice and master the importance of the commitment and to mark the life-changing experience of apprenticeship as much as to draw attention to illness. It was, of course, impossible for the indenture to cover in detail all aspects of an apprentice’s needs and expectations; no one supposed that those taking in a live-in youngster had no other responsibilities towards them. The indenture was, in Humphries’ words, a ‘package deal’; it was a legal contract but ‘incomplete’ in the sense that much was left unsaid or remained subsumed in the unspecific reference to the master’s responsibility for ‘all other Things necessary and fit for an Apprentice’ – a phrase open to wide and varied interpretation.Footnote 31 Such issues as the length of the working day or the effort expected of the apprentice were not fully explained, leaving incentives on both sides to keep the contract but also to renege.Footnote 32 Much then depended on ‘custom, good faith and reputation’ – hence the importance which vigilant and caring families attached to the selection of masters and employers.Footnote 33 Masters with a reputation to maintain had good reason to honour these expectations and parents to assume, unless stated otherwise, that care in time of sickness was part of the deal. Furthermore, the sort of social cohesion seen among Oxford tradesmen (see earlier) indicates that it was in their interests to respect obligations from which, in turn, their own sons or daughters might benefit.

An indenture, of course, did not guarantee the child or apprentice’s well-being (to which coroners’ reports, showing apprentices to have been starved and neglected, bore witness). Its value, however, was recognized in 1691 by an act which made it mandatory for parish apprentices to have written indentures. The intention was to make their situation less precarious and closer to that of apprentices outside the poor law. In its commitment to ensure the basics of food and drink, clothing, accommodation, washing facilities and training, the 1691 agreement mirrored the indentures arranged by affluent and middle-income parents or kin for apprentices pursuing skilled trades and professions. The parish contract, however, was a ‘one-size-fits-all’ agreement with limited scope for indulgent extras which, in any case, pauper parents were unable to negotiate. The expectation that the master or mistress was responsible for care in time of sickness (and much besides) was implicit in the injunction at the end of the parish indenture which insisted that, once bound out, ‘the said Apprentice … be not in any way a charge to the said Parish or Parishioners of the same name’. That this was widely accepted among pauper families themselves seems evident from Thomas Sokoll’s examination of pauper letters sent to poor law officials in Essex: while there are many examples of parents or kin asking for help for sick children living at home, there are none asking for help for a sick child or young person who had already become an apprentice or who had been hired out. The letters further show that the writers were often remarkably well versed in their poor law rights.Footnote 34 The assumption must be that they expected their sons and daughters placed in apprenticeships to be cared for by their master should they fall ill. On the basis of his analysis of more than 3,000 indentures in Kent in the mid-eighteenth century, Tom Marshall reached the same conclusion. Reference to the issue of illness was rare, being mentioned in the case of only 33 apprentices. In 29 of these cases the obligation was taken on entirely by the family. This specific mention of the family obligation would seem unnecessary if it was not already assumed to be implicit in the terms of the indenture and thus ‘recognised by all parties that it would be the master who would have to provide during sickness, unless it was otherwise stated’.Footnote 35

Charity organizations also opted for standardized indenture forms with appropriate gaps for the name of the apprentice, his master, the nature of the training and so forth, as well as the usual obligations on both sides of the contract. The London Foundling Hospital had its own ‘opt out’ clause: the apprentice was to be ‘not any way a charge to the said Governors or Guardians during the said Term’, implying again the master’s responsibility in the event of the apprentice’s sickness. The Hospital committee, however, included highly regarded medical men who took seriously the occurrence of illness among foundlings when living in the Hospital. They are unlikely to have overlooked the possibility of foundlings falling ill when once bound out. Poor law authorities had pressing financial reasons to expect a master to take on responsibility if a child fell ill. The Hospital, which received generous subscriptions in its early days, was in a better position to intervene if a master failed. The Birmingham Blue Coat School’s indenture put the responsibility for care in time of sickness on master or mistress by much the same means. The close contacts between the school and the community into which their pupils were placed facilitated contact with the children who had lived in the school for up to seven years. Both institutions had reputations to maintain and were sensitive to hostile criticism. By the eighteenth century the essentials of food, drink, clothing, accommodation, training and washing were pledged even to those entering one of the least prestigious ‘living-in’ apprenticeships.Footnote 36 Obligations beyond those explicitly listed on the indenture were generally accepted to include care for the apprentice who fell ill.

A development during the eighteenth century was for private apprenticeships to become more flexible and masters to shift the balance of responsibility. Obligations on both sides of the contract were defined more precisely, creating indentures which became more closely adjusted to the needs of the apprentice and also to the satisfaction of masters. Parents were concerned to find placements where their children would be well treated and to obtain value for their premium payments. Negotiations, however, increasingly favoured the master as more young people competed for apprenticeship places. This ‘shifting’ of obligation is indicated by the heavier premiums paid by anxious parents and by the relative ease by which masters could opt out of traditional responsibilities.Footnote 37 Much ‘boxing and coxing’ of provisions and responsibilities occurred. In Oxford in 1700 Richard Hall’s master, a white-baker, was not obliged to provide the customary ‘apparel’ but simply to find Richard ‘a pair of new shoes every year’. Richard’s parents had, presumably, got the best deal they could for the premium they could offer. The same ‘shifting’ of commitment from master to parent is seen in reference to the possibility of the apprentice’s illness. Pelling notes the increasing appearance of indentures in the eighteenth century which ‘explicitly relieved the master or mistress of the obligation to pay for medical treatment’.Footnote 38 In 1712, for example, Thomas Munday’s parents agreed to find ‘clothes & the cost of sickness & washing of linen’, thus relieving his master, an Oxford upholsterer, of two traditional responsibilities and acknowledging responsibility should their son fall ill.Footnote 39 Such agreements were not unprecedented: Christopher Brooks refers to indentures in the mid-seventeenth century in which responsibility for care and cost in the event of sickness might be open to such negotiation.Footnote 40 This may have been no more than concern for an individual apprentice with an existing health problem, but may also reflect a long-standing unpopularity of this particular responsibility. Some indentures in the eighteenth century became more precise about the exact nature of the arrangements: Samuel Vallis’s indenture (1745), arranged with an Oxford grocer, made it clear that his father was to provide ‘apothecary and physician’ should his son fall ill. This appeared as a handwritten note in the margin as an addition to the standard format, perhaps negotiated by the grocer as a strategic afterthought and ensuring that the parent was to arrange as well as to pay for his son’s medical care.Footnote 41 These were clear examples of ‘exclusion’ clauses being ‘intruded’ into the indenture in a move, in private contracts at least, away from standardization.Footnote 42 These ‘bespoke’ indentures marked a distinction between private agreements and pauper and charity indentures.

These developments illustrate the hazards which had always been evident in the ‘incomplete’ nature of the indenture. Masters might claim that the young person had become ill by staying out all night in inclement weather, by mixing with undesirable fellow apprentices, by disobeying regulations about work practices or that an incapacity or affliction had been hidden, perhaps unrecognized, at the time of binding. Unscrupulous masters might seek to evade the cost and trouble of their commitment; apprentices, frustrated by the constraints imposed upon them, failed to meet their own obligations of obedience and duty and this added to tensions. The persistence of such cases suggests again that supplying the cost for care of an apprentice facing sickness, while not a major grievance, might be an unpopular obligation which masters more frequently sought to evade.

If cases of issues arising over sickness were fewer than those arising over the basics of food, clothing, accommodation and training, they were nevertheless of significance. Nor is it surprising that complaints concerning sickness were less frequent. In illness, young workers lacked agency, but at other times they could stand up for their own interests: Rushton finds evidence in the northeast of England for both apprentices and servants acting on their own initiative to draw attention to a range of injustices, often with a successful outcome in cases brought to court.Footnote 43 Illness of any serious kind took away even the dubious expression of agency which they might otherwise have achieved through running away, and may explain why relatively few complaints of this particular kind reached public attention. Younger children, those far away from parents or the institutions which had placed them, and those without parents were especially disadvantaged.

The fall in the age of leaving home and the increasingly flexible operation of apprenticeship regulations

Two long-term developments in apprenticeship may have encouraged the occasional strategy of opting out of responsibility for an apprentice’s sickness or even of refusal to take an apprentice. Firstly, in at least some parts of England, the age at which adolescents entered apprenticeships fell. Secondly, the regulations guiding the binding of apprentices were relaxed or sidestepped, arguably creating a less enduring bond between master and apprentice. Patrick Wallis, Cliff Webb and Chris Minns found a reduction in the median age from 17.4 years to 14.7 years in males entering London to take up apprenticeships in the period 1575–1810. The study is based on 22,156 apprentices coming from many different parts of the country, destined for 79 different livery companies.Footnote 44 This was not a uniform development; occupations requiring heavy physical labour (carpentry and blacksmithing) continued to require stronger and older apprentices; those travelling from more distant parts of England and Wales tended to be older than those from the capital. Londoners would have family or kin at hand to assist them.Footnote 45 The general pattern, however, presented masters with a new cohort of apprentices who were often perceived to be more susceptible to the diseases of childhood and less likely to have built up immunities to epidemic diseases. Masters became not only anxious to avoid paying for medical expenses but also reluctant to accept into their household a newcomer more likely to introduce disease or even death.

Other studies have observed a fall in the age of apprentices as well as a tendency for young people to leave home at an earlier age for work of all kinds.Footnote 46 For the most part these studies consider apprentices other than those sent to prestigious livery companies and draw on sources relevant to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Joan Lane, for example, found an average age of 14 for non-parish males beginning their apprenticeships in Warwickshire, 1700–1800.Footnote 47 Higher premiums and greater concern for the conditions of children on the part of their parents may both have been linked to the fall in the age of leaving home. Masters required larger rewards when children were young, took longer to train and were less useful; parents were, unsurprisingly, more concerned with the conditions in which younger children lived and worked and hence more easily inclined to commit their own resources to medical attention and care.Footnote 48

Pauper apprentices were invariably younger than those sent to masters with the London livery companies and other private apprenticeships. Parishes concerned with finding homes and apprenticeships for pauper children came under more compelling financial pressure in the second half of the eighteenth century. Population growth and the effects of the war with France, especially from 1793, impoverished many families and left a significant number without a main breadwinner.Footnote 49 Many turned for help to poor law authorities which, in turn, faced complaints from ratepayers as poor law rates rose. The temptation for parish officials was to apprentice children at an even younger age in order to pass on the cost of their care to others as well as to avoid ‘the dangerous mobile period between about 4 and 14’ when children were thought to be more likely to fall ill.Footnote 50 Levene’s study of London parishes (1767–1833) found an average apprenticeship age of 12.0 for boys and 12.5 for girls (mean age 12.3) and a sustained lowering of age in the 1780s when the mean value dipped below 12 years.Footnote 51 Policy differed in different parishes and children sent to factories rather than to living-in roles in households were, as a rule, the youngest.Footnote 52 Nevertheless, those sent to live-in apprenticeships of the traditional kind, with which this study is concerned, were also younger. Some authorities were known to justify the age of seven, which provides an indication of the ruthlessness (or desperation) of poor law officials. In practice such a young age was rare and disliked by both masters and parents.Footnote 53

Charity institutions, hoping to continue to win private support, were influenced by the moral climate of the day. In The Fable of the Bees (1729), Bernard Mandeville argued that the poor should be taught to accept ‘hard and dirty labour’ along with ‘coarse living’; ‘Where should we find a better nursery for these necessities’, he asked, ‘than the children of the poor?’ Charity institutions were among the chief targets of Mandeville’s complaint; he accused them of over-educating children who ought to be prepared for a life of toil.Footnote 54 Such views did not go uncontested but appealed to subscribers to eighteenth-century children’s charities whose beliefs the guardians and governors could not ignore. School regimes and apprenticeship schemes were designed accordingly. The Foundling Hospital apprenticeship register for 1752 shows that boys of ten years old were being bound out for sea-service, an exceedingly harsh occupation for those so young.Footnote 55

More difficult to resist was the challenge to Foundling Hospital practices brought about by the years of the General Reception (1756–1760), an arrangement whereby the Hospital, dismayed by the number of children whom it was unable to take in, sought parliamentary support to increase its intake of infants. The immediate effect was a massive increase in the number of foundlings received into the Hospital, rising from a little over 100 each year to 4,000.Footnote 56 This large number, or those that survived, had from the late 1760s to be found apprenticeships. The solution, in Parliament’s view, was to place children out, where possible, at the age of seven. One result was the airing of conflicting views on the question of apprenticing very young children. A bill before parliament in 1765 proposed offering a premium of £7–£10 to potential masters and mistresses. The governors, by now receiving a reduced grant, mounted a spirited defence of earlier practices, arguing that very young children were not able to cope with heavy work and that premiums were liable to attract unsuitable households seeking a quick financial reward rather than providing adequate support for young apprentices. The bill passed, but the governors found ways of avoiding the more extreme solutions proposed.Footnote 57

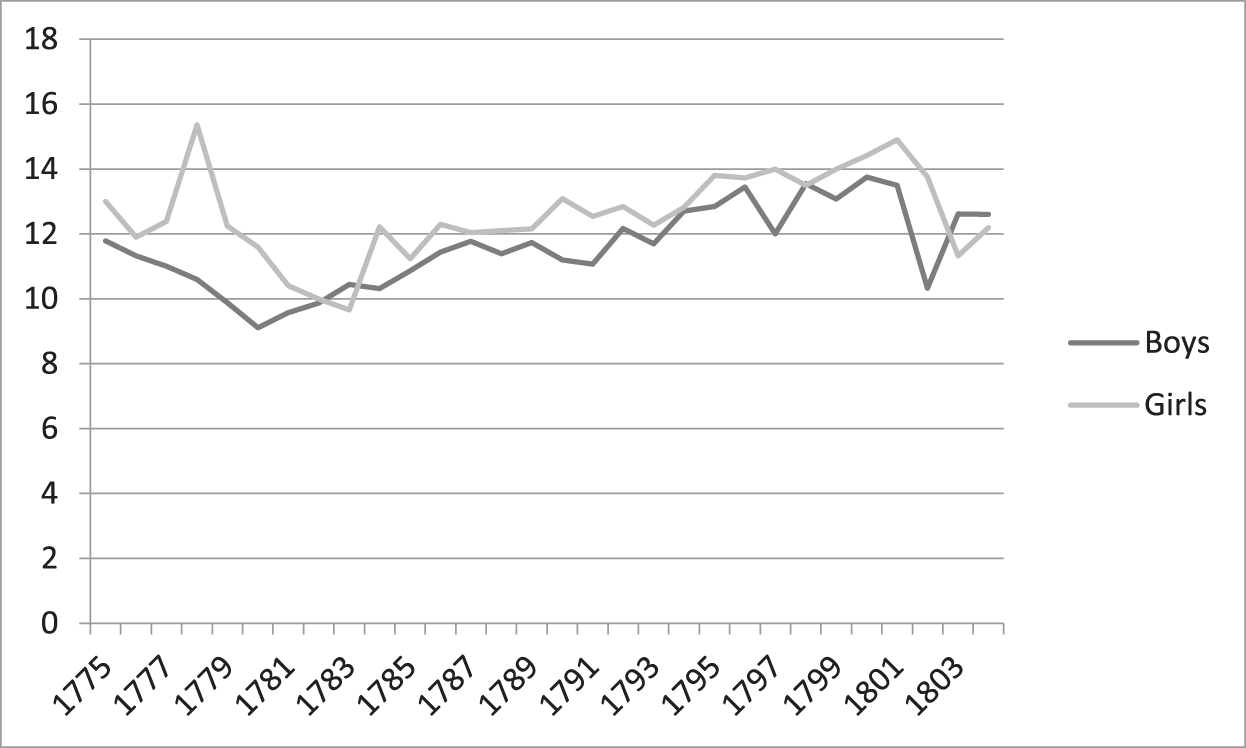

Figure 1 shows the ages at which the Hospital children were apprenticed in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. There is an overall, if irregular, rise in the age at which children were apprenticed. But it is also the case that some very young children were being sent out. Girls as a general rule had always been placed when rather older than boys and this was maintained in almost every year. Often the graph hides the influence of particular circumstances, or may be skewed by one exception in years when a small number of apprentices were placed out. It also hides some mitigating circumstances. The dip in the ages of boys in 1780 reflects the nine boys sent out that year who were under the age of ten. Only one was as old as 11. William Barringham, at eight years old, was to learn ‘the Art and Mistry of a Marriner’. He was sent, however, to Captain Addison in Bedford Square in London, and so probably expected to work as a house servant until considered old enough to work at sea. Five of the other boys went to ‘household business’, considered one of the less physically demanding occupations.Footnote 58 In 1802, the other year showing a low age for boys, only three boys were apprenticed: to a hairdresser, a surgeon (as house-boy) and a letter-press printer. Thomas Trott’s years with the hairdresser were successful: in 1813 he received a gratuity of £5 5s 2d when, at 21, his apprenticeship ended. This was granted when an apprentice had served well and won the approval of the master or mistress.Footnote 59 The 1777 peak for girls, which contrasts with the downward trend for boys, is influenced by the placements of Elizabeth North and Martha Warden, both at the unusually high age of 18.Footnote 60 There may have been health or practical reasons for this. Elizabeth went to a widowed laundress who may have requested an older girl for the heavy work required in a laundry. There were, however, striking examples of the apprenticeship of very young girls. In 1779 Grace Windsor, at the age of only eight, was apprenticed to Ann Graham, a widowed haberdasher.Footnote 61 Graham may have been a tried and trusted mistress who had proved her worth or came with high recommendation. The Hospital could not afford to lose households which had provided care and diligent training in the past and, in such cases, might respond to requests whenever they arose. Foundling Hospital masters and mistresses may have been exceptions to the rule; young workers were acceptable if they came with the good behaviour associated with well-trained foundlings.

Figure 1. Ages of apprentices sent out from the Foundling Hospital 1775–1804.

When apprenticed, the foundlings were of a similar age to the parish apprentices studied by Levene in London in the 1780s. There were, however, safeguards intended for the protection and future well-being of the foundlings. Efforts were made to select suitable masters and mistresses, especially in the case of younger children. The inspection system, which had been unable to cope with the huge numbers during the General Reception years, was, by the 1770s, functioning more efficiently. Clearly this boded well should children fall ill or be affected by other afflictions. Not until 1806, however, did the General Council of the Hospital rule that no child should be bound out before the age of 14, bringing them closer to the experience of children whose parents placed them into skilled and professional apprenticeships. The Birmingham Blue Coat School, meanwhile, had maintained its policy of retaining both boys and girls until the age of 14. Few parish apprentices could hope to delay the start to their working life until the age of 14 and it was rarely possible to give careful attention to their destinations.

Much the same economic and social pressures which pushed the poor law authorities into binding out younger apprentices in the last years of the century also compelled individual families to apprentice or hire out their own children at a younger age. Many would have preferred not to do so.Footnote 63 Agriculture remained a dominant occupation for boys and domestic service for girls at the end of the century and beyond. Both were traditional trades invariably involving a living-in role, and often in the case of poor children without even the uncertain protection of a formal apprenticeship.Footnote 64 Shoemakers and weavers might still take in poor children to live in while they trained, but both were ‘overcrowded’ trades with poor prospects.

The whole question of the age at which children left home for work is, of course, immensely complex with variations based on time, regional differences and occupations.Footnote 65 As the Hospital governors had argued, younger apprentices and living-in servants were unwelcome in many households as well as in greater danger of abuse and neglect, which may have had consequences if they fell ill. They were judged too weak, less capable of a range of tasks, in need of greater supervision and prone to such problems as bed-wetting (of which households frequently complained) and homesickness. Masters had always been aware of the possibility of a young worker falling ill when living in their family and adolescents were prone to a range of diseases. The prospect of coping with a young child of perhaps nine or ten who fell ill was daunting as well as costly.Footnote 66 Such concerns must at least have contributed to a growing reluctance to take an apprentice or young living-in servant and, of course, to an unwillingness to care for a sick worker in their household.

Autobiographies provide anecdotal evidence for households which were at least cautious about taking in young or less robust children. John Gibbs, at the age of ten, was not encouraged by the reception he received when applying to replace a house-boy in a gentleman’s house in Sussex in the 1770s: ‘some said, I was much too small, others that I was altogether unacquainted with the business’. John believed that he was taken on as an act of charity out of pity for his wretched state.Footnote 67 Mary Ann Ashford recalled that, at the age of 12, her father had been given into the service of an acquaintance of the family to act as his general factotum. The man doubted if such a young boy would be useful and took him grudgingly. He thought him ‘too young, but would try him’.Footnote 68 It was no less true for girls. Elizabeth Purefoy wrote to a friend in an effort to find ‘a young healthy girl’, but not so young as to be unable to spend long hours at the washing tub. A request for a ‘stout’ girl often accompanied a search for a new housemaid. When masters were offered only the youngest workers, this was hardly a good omen. The obligation to provide even the basic requirements for their living-in worker was resented by many masters; they were hardly likely to show willingness to fulfil obligations beyond this, including care in time of sickness.

While the age at which a child or young person left home to work elsewhere fell, the terms of apprenticeship and obligations on both sides had become less rigid and less assiduously observed than once supposed. Earlier studies have drawn attention to the flexibility applied to the regulations laid down in the 1563 Statute of Artificers from its earliest years.Footnote 69 Drawing on new sources, Minns and Wallis provide substance to these observations, tracing and quantifying the experiences of apprentices in London and Bristol between 1786 and 1796 and suggesting that apprenticeship seems to have been ‘much more fluid than is traditionally understood’.Footnote 70 Citizen records reveal a high rate of breakdown of apprenticeship agreements, often well before the customary seven-year term was completed. Approximately 26 per cent of London apprentices never, therefore, became citizens in year seven of the study and approximately 36 per cent in Bristol.Footnote 71 The reasons were various, often unavoidable and not necessarily unwelcome for either side: the death or imprisonment of either master or apprentice; a mutually agreed departure usually when the two could not be reconciled; or when the apprentice worked for another master or perhaps worked and lived in a different part of the business from his master. Most striking were the numbers of apprentices who ran away, were dismissed for bad behaviour or found a new master. Other arrangements involved the apprentice working away to gain additional experience or attending to concerns of the master elsewhere. The point, for the purpose of this study, is that if masters could not depend upon (and sometimes did not wish for) a seven-year term of service, they were less likely to form the strong bond with the apprentice which would incline them to accept an ‘in loco parentis’ relationship and take responsibility for an apprentice’s illness.

The position of pauper and charity apprentices was different but not without parallels. Parish apprentices were expected, and under some pressure, to serve their seven-year term. Runaways could be recovered, punished in a house of correction and returned to their master. For pauper apprentices, a main incentive to completion was the attainment thereby of legal settlement (see earlier) – the right to claim poor relief. William Hart’s experience in London suggests that apprentices were aware of the importance of the settlement qualifications and especially in the event of sickness. Just weeks after the end of his time as an apprentice cooper in the 1790s, William contracted smallpox and, appealing to his parish officer, received both care and protection, confident that, ‘As I was a Parishioner by my servitude they must provide for me’. He was provided with two parish nurses and, he said, ‘every necessity for my recovery and the parish doctor attended me’.Footnote 72 William’s experiences underlined the value of completion but at the same time made it clear that, while an apprentice was in ‘servitude’, it was the parish master or mistress who was responsible for attending to their illness. Hart’s experience provides an example of a far from callous poor law authority. Nevertheless, the promise of settlement was not necessarily enough to deter a 16-year-old from fleeing an abusive master, a parsimonious household or even a tedious occupation for which he or she had no inclination. Runaways were frequent among pauper apprentices, and breakdowns through death, imprisonment and debt were not unusual.

Young servants, hired out by parents or sometimes through their own initiative to living-in work based on casual, informal agreements or sometimes none at all, present a different case again. As discussed earlier, they were free to leave after a year, having in their case earnt settlement rights. Contemporary employers complained of the rapid turnover of domestic staff, especially the young, whom they had spent time and effort training. This suggests that until loyalty had been established, they would be unwilling to commit to anything beyond what local custom or parental pressure might demand.Footnote 73

From the late seventeenth century, therefore, masters or mistresses seeking or under pressure to take apprentices or young hired workers into their households were presented with a cohort who were younger than was previously the case. They were to be with them for a longer period, given the age at which apprenticeship ended, and believed to begin at an age when they were most susceptible to disease and more difficult to care for. Over the course of the eighteenth century the nature and character of apprenticeship changed; regulations continued to be relaxed and open to interpretation and apprenticeships more often came to a premature end; apprentices in privately arranged contracts were more likely to live in their parental home. It was not uncommon for a male apprentice to marry, which formerly had been forbidden. In such cases the family or kin became responsible for the care and cost of the apprentice’s illness. Population growth and inflation aggravated by the French wars contributed to the rise in the number of parish and poor charity apprentices. The number of apprenticeships based on private family arrangements, and favoured by the moderately well-off (with incomes of £20–£100 per annum), remained stable, as this group could no longer always afford the premium for skilled middle-ranking training. By the late eighteenth century, the influx of paupers and the growth in the number of charity apprenticeships alongside the relative decline of middle-income apprenticeship meant that the institution became more characteristic of the children and adolescents of the poor. It was also more ‘feminine’, owing to the addition of larger numbers of parish girls.Footnote 74 In the eyes of many, apprenticeship lost status.

Impact of smallpox

The appearance of more virulent forms of smallpox in the late seventeenth century highlighted the general issue of sickness among apprentices and other young living-in workers. It had, as Pelling shows, a particular impact on the question of who paid for the cost of medical treatment.Footnote 75 Between the mid-seventeenth century and the third quarter of the eighteenth century, the frequency of smallpox epidemics increased from roughly a four-yearly to a biennial cycle.Footnote 76 The disease appears as a threat or blight in the writings and recorded experiences of all sections of society –in diaries, correspondence, autobiography, charity records, poor law documents and fiction, providing us with an insight into a wide range of household and institutional responses to smallpox and to illness in general.

Smallpox conferred lifelong immunity on those who survived its effects and, consequently, as successive outbreaks occurred, became an illness to which children and adolescents were most vulnerable. Apprentices and other young people who were moving into crowded urban areas were vulnerable to smallpox because they had previously lived in rural areas where precautions had been taken to prevent the spread of this disease. The danger was greatest in the south of England, where measures were taken by many rural and small communities to contain the disease (pest houses for isolation, limitations on travel, fairs and markets) and where, consequently, immunity was low. Where smallpox was widespread and few precautions taken, those migrating to crowded urban areas were as likely to have contracted and survived the disease as the apprentices already living there.Footnote 77

Some masters, fearful of challenges to their obligations, sought excusal from any expenses relating to smallpox. In Oxford, a notable centre of trade and exchange, where Sam Bayly became apprenticed to learn tailoring with William Wheeler in 1737, it was agreed that ‘if [the] apprentice be visited with smallpox during the term then the charges thereof shall be borne by John Thatcher of Oxford, baker, his uncle and William Bayly his brother’.Footnote 78 The agreement followed recent outbreaks of smallpox in the Oxford area. Sam had arrived from Faringdon in neighbouring Berkshire, which may explain Wheeler’s caution.Footnote 79 Those responsible if Sam fell ill were close by – an example of kin who were concerned or under pressure to look after their own. In Wiltshire in 1750 it was a brother who stepped in for Joseph Prior, who was to be trained in the art or trade of a cordwainer. The premium was the modest sum of £12 12s. James Prior was ‘to be at half the expence [sic] of physick and attendance in Smallpox’.Footnote 80 This division of cost and care was not uncommon, perhaps reflecting both the difficulties faced by the master and the concern of family members. Both master and apprentice might have preferred to return the sick child to their own family home, but this was unlikely if the distance was considerable and the disease as contagious and feared as smallpox.

In Buckinghamshire, the Purefoy family obliged newly appointed servants to sign an agreement to leave if they contracted smallpox. Child workers were a particular source of concern. In 1743, Elizabeth Purefoy, negotiating the appointment of Jo Sheppard with the boy’s mother, detailed the wages, clothing and boots which Jo would receive, adding ‘and if he shall be visited with the small pox hee must quitt his service’.Footnote 81

Overseers had reason to put pressure on masters lest the burden of care should fall on the parish. Not all poor law officials, however, were without concern for smallpox victims, including apprentices: in March 1766, the officers of the Wimbledon vestry met ‘to take opinion of counsel on Geo. Scarnell’s indenture, if the master is not entitled [obliged] to maintain him in time of sickness during his apprenticeship’.Footnote 82 William Hart’s experience (see earlier) in obtaining medical help in his London parish presents a contrast. He was given help only because he had completed his apprenticeship. The hope in the case of a serving apprentice was a sympathetic master or mistress committed to the indenture’s ‘hidden’ agenda. Yet the dilemma in Wimbledon over George Scarnell’s case suggests that parishes could not and did not altogether evade responsibility. As Steven King’s study of poor relief in Lancashire indicates, the absence of any common poor law policy was ‘nowhere more so than in the context of the sick poor’.Footnote 83

Not all employers or masters were as ready as the Purefoys to make smallpox a reason for dismissing their household workers. Some, influenced by the force of tradition, a strong sense of moral obligation or simply their ability to sustain the costs, accepted responsibility for both medical treatment and care. When, in November 1762, Robert Redford, a boy groom in Lord Carnarvon’s Minchendon estate (Middlesex), contracted smallpox, he was provided with a nurse, her assistant and the attention of an apothecary or doctor.Footnote 84 Others who dismissed their sick apprentices or proved indifferent to their illnesses were also in evidence. Jeremiah Watts, hired in 1787 as a carter at the age of about 17 by Mr Westall in Thatcham (Berkshire), took two weeks’ absence from work when suffering from smallpox. Westall took him back but subtracted a punishing half a guinea (10s 6d) from his wage of £6 a year.Footnote 85

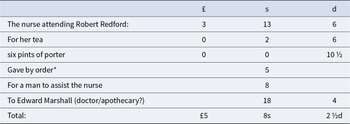

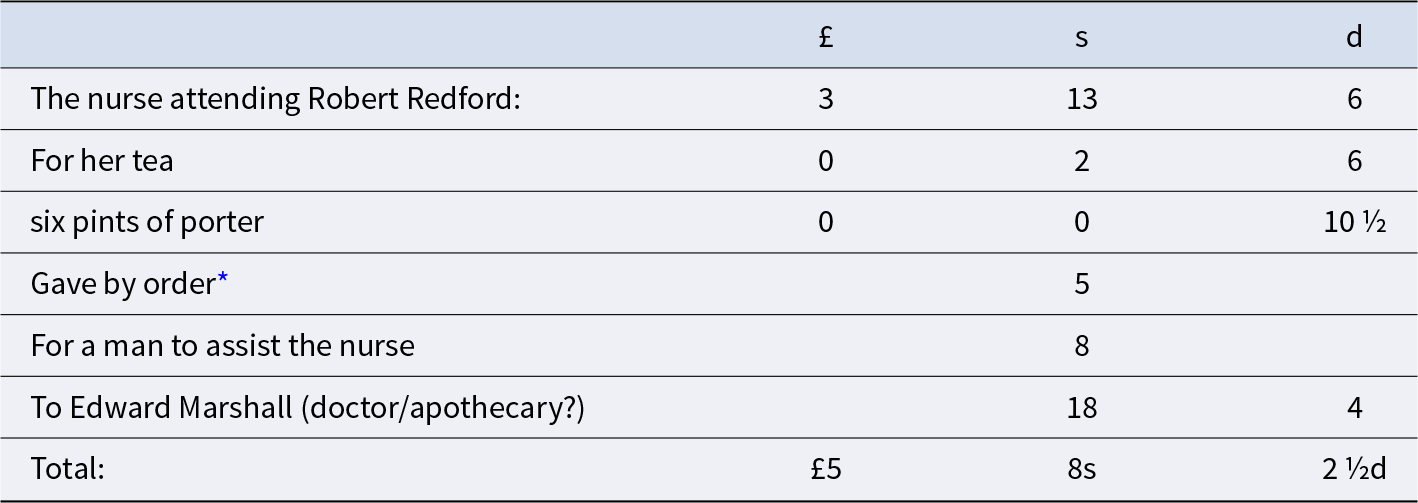

Some households might have argued, with reason, that their circumstances and income allowed little provision for medical care or that a substantial deduction of wages was necessary to pay for a replacement worker. Table 1, showing the cost of care and treatment when Robert Redford contracted smallpox, indicates the problem.

Table 1. ‘Expenses for Robert Redford in smallpox’

Source: Home Bill of the Marquis of Huntington, Huntington Library, ST 389, Box 14, items appearing between 2 December 1762 and 31 January 1763.

* Note: Perhaps a perquisite for diligent service.

A boy substituting for Robert for the four weeks and two days of his illness earnt £1 10s.Footnote 86 This means that the overall cost was £6 18s 2 ½d – hardly a problem for Lord Carnarvon whose expenditure on food and servants’ wages for half a year was £157 6s 4 ½d – but an impossible amount for a straitened artisan household which had taken on an apprentice or child servant to save labour costs.Footnote 87 Even if a member of the household took on the nursing role, this could mean an unwelcome reduction in overall earnings. Poor law officials and charities were soon aware that smallpox had heightened fears about an apprentice falling ill, making it more difficult to find households willing to take in young workers. Many who had taken a pauper apprentice already failed to provide sufficient food, clothing and accommodation. Parishioners of modest means who might be expected to take a pauper apprentice found it an easier option to pay a fine (usually £10) to be excused.

This concern to secure placements meant that many destined for live-in apprenticeships and domestic work were among the first to benefit from inoculation against smallpox. First pioneered in England in the 1720s, inoculation was a hazardous procedure involving discomfort, a period of isolation and considerable expense. The Foundling Hospital began the first inoculations of foundlings in 1743, anxious to reduce the number of smallpox deaths and informed by what had been learnt from earlier procedures. It became routine practice and results were encouraging.Footnote 88 It was also a means of reassuring households who contemplated taking a foundling as an apprentice. Smallpox was one of many diseases or complaints that threatened children and adolescents, but, at a time when it may have been responsible for nearly half the deaths of those aged between five and nine in London, inoculation provided a safeguard, especially to households with young children of their own.Footnote 89 The rationale of Hospital policy was clear to Juliana Dodd, a Foundling Hospital inspector in Berkshire. In 1767 she reported that she had paid for two children to be inoculated, ‘having promised it to their masters at the time of [their] being apprenticed’.Footnote 90 Dodd would have been aware of advertisements of the kind placed in an Oxford newspaper a few years earlier: James Newton sought a livery servant who could be recommended for his ‘Honesty, Care and Abilities’, but Newton’s first concern was that he ‘hath had the Small Pox’.Footnote 91 A more perverse example of the perceived merits of surviving smallpox appeared in The Public Ledger in 1761: an auction in London offered the sale of a ‘Negro Girl, aged about fifteen years’, who could be commended for her domestic skills but also because she ‘has had the smallpox’.Footnote 92

Proof of inoculation or the visible evidence of pockmarks could therefore represent a passport to worthwhile training or at least a means of livelihood. The incidents of deaths still resulting from the procedure, however, as well as hostile publicity and expense were sufficient to deter many.Footnote 93 Poor law authorities, charities and individual masters had to balance the advantages against the high cost, continued risks and popular prejudice.

By the 1760s, a safer form of inoculation that was easier to administer made the procedure more acceptable. A combination of entrepreneurship, altruism, fear and prudent economics extended the reach of inoculation to some of the poor.Footnote 94 A contributor to The Gentleman’s Magazine singled out servants as a group likely to benefit from low-cost inoculation: if they had not had smallpox, they risked ‘losing their good place’ – or, in the case of charity children, not gaining one.Footnote 95 Most London parishes for which relevant records survive had made routine arrangements for the inoculation of pauper children, including infants. The immediate purpose was to persuade nurses to take infants into care, but overseers realized that potential masters and mistresses would welcome removal of the smallpox threat.Footnote 96

Not all parishes were prepared to take such action, nor was their response so thorough or well directed. As late as 1791, Parson Woodforde lamented the refusal of the parish to pay for the inoculation of the six children of Harry Dunnell in Weston Longeville (Norfolk) while it had arranged for the inoculation of the Case family – ‘tho’ a farmer and better off’. The parson was a strong advocate: ‘It is a pity that all the Poor in the Parish were not inoculated also. I am entirely for it’.Footnote 97 Woodforde, like other individuals who could afford it, had already acted to protect his own household servants. In November 1776, Dr Thorne visited the parsonage to inoculate the youngest, Ben Legate, and ‘little Jack Warton’. Jack was then ‘about ten or eleven years of age’. At a later date the ‘New Boy Jack Secker’ returned from Thorne ‘after inoculation’, as if this became a regular procedure when boys entered Woodforde’s service.Footnote 98

Matthew Flinders, ‘surgeon, apothecary and man-midwife’, inoculated his young servant-maid and boy at the same time as his daughter, Susan, when smallpox hit Donington in Lincolnshire in 1783.Footnote 99 Mary Hardy, a Norfolk farmer’s wife, records the several occasions when the local physician or apothecary came to inoculate their current boy-servant.Footnote 100 Mrs Hardy was aware of the dangers: her daughter, Polly, had been dangerously unwell following inoculation in 1776 and bore smallpox scars thereafter. In July 1787, Sophie Burcham, a neighbour’s daughter, had died, aged 11, following inoculation.Footnote 101

Smallpox had drawn attention to the wider question of responsibility for the illness of a living-in apprentice or young worker, and inoculation demonstrated the importance of preventive measures. Smallpox was only one of many illnesses. Contemporary commentators continued to urge household heads to give care and attention to servants in need of medical attention, perhaps aware that some had explicitly opted out and others had complained. In 1786, John Trusler argued that an annually hired servant ‘could not be discharged by reason of sickness, or any other disability by an act of God’. Writing with more authority in his 1799 guide to legal rights and obligations of masters, James Barry Bird insisted that an apprentice ‘could not be discharged for illness even if the disease seemed incurable’. In 1816, George Watkins could only appeal to the better nature of heads of families: ‘All the care that our opportunity and pecuniary ability will allow is certainly due to our servants in time of sickness’, but, he added, only if they had been ‘acceptable’ in their role.Footnote 102 In Hampshire in 1816 William Cobbett, the reluctant recipient of a pauper apprentice into his household, recognized his obligation to see that the sick child was ‘doctored’, but his resentment of the cost and responsibility expressed the feelings and reluctance of other masters.Footnote 103

Individual experiences

The experiences of many who fell ill while serving as apprentices or ‘living in’ as servants are recorded in sources which are more likely to have survived for wealthier households and charities in the form of diaries, account books and apprenticeship registers. These were more likely to register favourable treatment, which reflected well on the reputation of an individual or institution. Legal records, coroners’ returns and newspaper reports commonly contain the very worst examples of neglect and callousness. Linda Pollock observes that many sources most readily available to the historian of childhood may tell us more about abuse than the everyday experiences of children. Sensational stories in the press cannot be assumed to be typical; there was little reason to record an apprentice, a maid or a house-boy whose life ticked over unremarkably.Footnote 104

Those most likely to receive sympathy and practical help in illness had usually been with a household for some time and earnt, in some sense, a place in the family. Anna Larpent, wife of a civil servant in the office of the Lord Chamberlain, showed concern when, in 1792, her 18-year-old under-servant Richard fell ill with measles. Her account of Richard’s condition suggests anxiety for someone close to them all. ‘We are concerned at eighteen the measles are a bad business and he is very slight.’ Two days later, ‘We had been disturbed all night by expecting the death of Richard … All morning up and down the stairs with the poor creature whom we thought dying from the violence and ructions and convulsive spasms.’ Three days later she ‘found Richard recovering’. Mrs Larpent had servants to help but records her own tiredness; she was not just delegating nursing to others.Footnote 105

Parson Woodforde, too, could take a ‘hands-on’ approach, recording the progress and treatment of his servants’ illness in some detail. In August 1783 his household was stricken with a ‘fever’, thought to have been malaria. It was Lizzie Greaves, the under-maid, and his ‘boy’, Jack, for whom Woodforde expressed most concern. Jack (or Jackie) Warton was the longest serving of Woodforde’s ‘boys’, taken out of charity when very young and something of a favourite. He would have been 12–13 years old in 1783. Lizzie’s youth is indicated by her low wages of £2 0s 6d a year. By 14 August, Lizzie was ‘worse than ever and kept [to] her Bed most part of the Day’.Footnote 106 Woodforde, advised by Dr Thorne, sent for ‘Bark’ (quinine), arranged for Betty, his head maid, to sit with Lizzie at night and at times supervised her medicine himself. That her condition was serious is indicated by the arrival, on 28 August, of her mother who slept at the parsonage for three nights. On 27 September, Lizzie was still ‘very poorly’. Not until 6 October could Woodforde record ‘All my Folks continue better’.Footnote 107 While Woodforde’s own homespun treatments could be eccentric (he once treated a stye on his own eye by rubbing it with his ‘Black Tom Cat’s Tail’), his servants on this occasion were treated by a qualified physician.Footnote 108

Less fortunate in the unregulated world of eighteenth-century medicine was Camp Collins, a 17-year-old apprentice to a cabinetmaker in Clerkenwell. His mother and master were anxious to cure his attacks of giddiness, but, in their case, money was a consideration. They consulted a local soi-disant herbalist, Jacob Evans: ‘the expense will be a very few pence’, he told Camp. He prescribed a dose of foxglove, which the qualified surgeon, Mr Henry Whitmore, called in to comment on the case at the Old Bailey considered ‘twelve or fifteen times the quantity beyond the common dose’. Camp died in much distress – the result not of negligence or malice for, as Whitmore said, ‘Nothing but complete ignorance could have led to such a dose being given’. Evans was pronounced not guilty of manslaughter, which may tell us something of the value attached to an apprentice’s life.Footnote 109

Foundling children, received into the Hospital within a few weeks of birth, baptized and given new names, thereafter lost all ties with family or kin. The Hospital, however, could function as a ‘surrogate’ parent for its apprentices, through an inspection system in London and regional branches. Masters, mistresses and apprentices themselves, as well as inspectors, sometimes brought illnesses and afflictions to the attention of the General Committee. In the first instance it seems to have coped with them much as it dealt with other matters (allegations of abuse, failure to train or provide adequate training, misbehaviour of the apprentice) by bringing in the master or mistress to account for their behaviour or discuss action to be taken. In 1775 Samuel Adams was returned to the Hospital because ‘violent running in his ears’ made him unsuitable for work in a gingerbread shop. The Hospital committee accepted his master’s claim that Samuel was suffering from the complaint before being apprenticed. He was taken back and cared for until found a new post as a household servant with George Coleman, a ‘gentleman’, in Carmarthen, and later, still only 11-years-old, returned to London as a household servant to a wine merchant in Hanover Square.Footnote 110 John Trevor was held back from apprenticeship until he had recovered from his ‘diseased heel’. His master, a letterpress and copper-plate printer, was assured that John would be received back if the condition returned, leaving him unable to cope with the work. When this proved to be the case, plans were put forward for John to be treated in Margate infirmary.Footnote 111 Neither case was the same as those previously discussed as the Hospital was aware of the problem before the foundling was placed out with his master. The committee did not evade responsibility: alternative arrangements were made for Samuel, and John received hospital treatment for his foot.

When, in 1795, Mary Hereford complained that Benjamin Cater had transferred her to a new master and that she was now ‘afflicted with Rheumatism to a violent Degree’, Mr Cater was called to explain ‘why he does not take proper care of his said apprentice’.Footnote 112 The result of such exchanges was a series of compromises and shared responsibilities. When Laetitia Keene was ‘in a declining way’, her mistress asked that she be received back into the Hospital until she recovered but offered to pay for Laetitia’s maintenance.Footnote 113 William Malisher, a shoemaker, had obtained help for his apprentice from a local doctor but, following the prescribed diet (‘grewel and Cammomiel Tea’), the boy remained so weak that he ‘stops work after a short space’. Unable to provide the appropriate medical assistance, Malisher then sought the assistance of the Hospital.Footnote 114 The arrangements were not always achieved amicably and the intervening period for the apprentice in a resentful household could be difficult. Nevertheless, most masters and mistresses accepted that the obligation rested with them in the first instance and the committee cooperated to seek the apprentice’s well-being. Where appropriate, it acted to reassign the boy or girl to a more suitable occupation or household.

The fudged nature of responsibility for sickness is apparent in the response to the mental illness of William Seal, apprenticed to ‘household business’ in Jersey. In August 1790, 17-year-old William found his way back to the Hospital. According to a letter from his master, Jean Fillieul, in May of that year, the boy had been kept inside, ‘being out of his reasonable mind and entirely unable to perform any kind of work’.Footnote 115 The Hospital cared for William for some weeks but, perhaps fearing to create a precedent, the General Committee was reluctant to continue to fund all support needed. Failing to obtain a place for him in the parish hospital, the steward applied for an order to return William to his master. The response of the sitting magistrate, Mr Balamane, seems thoughtful and humane: he advised bringing an action against the master for causing William to become chargeable to the Hospital but at the same time ‘wondered they should think of sending him back’ given the distance involved. He urged them ‘as Guardians of the children (who have no other Friends) to take best care of him in his present unhappy state’.Footnote 116 Fillieul alleged that William absconded after stealing a boat (the committee preferred to say that he had been sent back), and expressed willingness to pay for ‘charges’ (unspecified), which William might incur ‘if ever he returns’. He added, not unreasonably, ‘that we have not in this place any house wherein to confine persons in this situation’.Footnote 117 Perhaps Fillieul reneged on his promises, perhaps he had never expected William to find his way back to the Hospital, but it seems that the precise nature of responsibilities was not clear to either party. The committee was to meet again to consider William’s case; meanwhile, he was to stay with a Mr Hoxton, for which the Hospital paid 8s a week.Footnote 118 William’s future cannot have been a happy one. Neither Hospital nor master was indifferent to his plight, but neither was willing to take full responsibility for his condition.

Fillieul, described as a ‘gentleman’, was probably a man of some means, which may explain the committee’s persistence, but towards the end of the century the Hospital had encountered a number of difficult cases and its financial circumstances, never very secure, were less so. Moreover, by the 1790s the Hospital had removed uncertainty about who should take responsibility for sickness in the case of the small number of apprentices, mostly girls, sent out to textile mills. Under the 1792 Articles of Agreement with Toplis & Co., a worsted manufacturer in Cuckney (Nottinghamshire), the firm was to provide ‘Attendance Both in Sickness and in Health’ as well as the standard items.Footnote 119 Two years after the Toplis arrangement, Samuel Boddy asked the Hospital to take back his apprentice, George Boyd, ‘now so weak that he was useless to him’. Boddy was to be sent a copy of the resolution passed at the last meeting to inform him that ‘as the Committee never receive back any Children after they are once apprenticed on account of Ill-Health they cannot deviate from that Resolution’.Footnote 120 It was not good news for George Boyd; what emerges in all these cases is the helplessness of an apprentice who fell ill and their dependence on others. Those who could draw attention to their circumstances did receive help. But Mary Hereford was 20 and near the end of her term, and William Seal, 17. It was more difficult for a young, newly placed apprentice, especially when far from the Hospital; many remained dependent on the resources, humanity, inclination or idiosyncrasies of the households to which they were bound.

The experience of the Birmingham Blue Coat School bears out the importance of the close proximity of parents and community. Appeals to the school for help in the event of sickness were unusual, less contentious and sometimes related to other matters. Masters and mistresses apparently accepted that they were to take any necessary action in the event of one of their apprentices falling ill. The school, however, did take measures to avoid sickness arising when apprentices were in their new workplaces. Charles Barton, ‘not in a fit state of health to be in service’, remained in the school until well enough to be placed out.Footnote 121

The school, like the Foundling Hospital, seems to have acted on an ad hoc basis rather than from a set of rigid rules. It was prepared to step in when problems arose, or commitments were not met, but the initiative came usually from the apprentice or parent. In 1784, Richard Jenkins was apprenticed to Messieurs Whitworth in an arrangement whereby the firm paid for him to be boarded with his parents. When Richard fell ill, and Whitworth refused to continue paying maintenance, his mother applied to the school for help. The committee ‘referred the matter back to the Masters, it being their duty’. Richard’s mother did not ask for assistance with medicine or nursing, which she was prepared to undertake herself, and in this sense made no demands on the school. The committee intervened on her behalf over a problem which had arisen from the illness of one of their apprentices, but without admitting responsibility for medical care, and expected only maintenance from Whitworth during Richard’s sickness.Footnote 122

The committee took a more active role in Charlotte Burton’s case. Her illness was alleged to have arisen from her being ‘very cruelly treated by her master’, Mr Bond. She claimed to have been whipped on several occasions and that her master had threatened to hang her. When attending the meeting called to consider her claims in 1787, she fell into ‘a very bad fit’, which brought the enquiry to an end.Footnote 123 By July Charlotte had been taken back to live in the school but by December was judged to be ‘not in a fit state of health to be in service’. In January 1788, it was Charlotte’s mother who provided a solution when she sent for her daughter to join her in Manchester where she had relocated. The school paid travel expenses.Footnote 124 More than ill health was at stake. A series of acrimonious letters had reached the committee and rumours of problems in the Bond household became local knowledge. The matter was the subject of a newspaper report. The committee had felt bound to defend the reputation of the school and issued an indictment against Mr and Mrs Bond.Footnote 125

Caring for a sick apprentice was less difficult in the integrated Birmingham community to which the pupils returned and where parents or kin were often close at hand. Some children were apprenticed to their parents so that parent and ‘master’ were one and the same. The problem of deciding responsibilities when illness occurred did not arise. While far from affluent, most masters with Blue Coat apprentices had some degree of independence and financial security. Having cared for the pupils for several years, the school seems to have had high expectations of the community’s role thereafter. The actions of the school committee were presented as exceptions to the rule that in cases of an apprentice’s sickness the household head was responsible for arranging and paying for medical care and attention.

Mary Ann Ashford’s autobiography provides us with rare insight into the perceptions of a young female worker living in as a hired domestic servant. An orphan when she entered domestic service in London in 1801 at the age of 13, Mary negotiated her own agreements with the families who engaged her. Unlike an apprentice, Mary was free to move on once the contracted term (usually one year) had been served. To improve her circumstances, she found a new place in City Road, but became ill soon after the move. The doctor attributed the haemorrhage from her ear to a ‘violent’ cold caught on the bleak, wet day when she carried a heavy parcel of books across London in preparation for the removal. Who paid the doctor is not revealed. It seems unlikely that Mary’s new mistress, ‘penurious in the extreme’, who kept her seriously short of food, would have been willing to spend money on a doctor’s fee. Mary might have appealed to family members, but they had never approved her decision to enter service, believing that she had ‘lost caste’. Barely 15, she remained alarmed by the dramatic nature of her complaint and experienced a long period of anxiety. In time, Mary’s condition improved without further medical treatment.Footnote 126 She might otherwise have followed the dismal trajectory of the fictional Humphrey Clinker, another (supposed) orphan: following a fever, he used his savings and pawned his clothing to pay for treatment and medicines, thus appearing so wretched and ill clad that he lost his job.Footnote 127