Introduction

Sympathy – a feeling of sorrow or concern (Eisenberg, Reference Eisenberg2000) – is an emotional response to another’s suffering and is important for motivating children to help others in ways that demonstrate care for a victim’s welfare (Malti et al., Reference Malti, Gummerum, Keller and Buchmann2009). In addition to its prosocial function, researchers have long demonstrated that sympathy serves as a stop signal for aggressive acts (e.g., Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2019; Mayberry & Espelage, Reference Mayberry and Espelage2007). That is, feeling concern for a victim of harm deters children from engaging in future harmful behavior and helps them orient to the consequences of their actions on others (Malti, Dys, et al., Reference Malti, Dys, Colasante and Peplak2018). Children’s capacity for sympathy supports their moral growth and reduces their risk for externalizing problems such as conduct disorder and violent offending in adolescence and early adulthood (see Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Zuffianò and Spinrad2024).

Extant work on the links between sympathy and aggression has focused on measuring children’s sympathy in response to the harm of familiar, innocent, and needy victims (i.e., situational sympathy applied toward particular targets in particular contexts of need), or has focused on sympathy at the dispositional level (i.e., children’s general tendency to feel sympathy without mention of context nor relation to target). Less is known about how children exercise their sympathy across more complex and contentious social situations and how their constriction or extension of concern relates to their social behavior – specifically their aggression (i.e., behavior intended to harm another; Krahé, Reference Krahé2013). Current global challenges of war and violence highlight the destructive role that selective concern (i.e., extending concern toward certain individuals or groups) may play in reinforcing cycles of aggression. As such, researchers have centralized sympathy as a core factor implicated in aggressive behavior problems (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Zuffianò and Spinrad2024).

In this study, our first aim was to examine children’s (ages 6, 9, and 12 years) sympathy as witnesses of peer victimization within two contexts: (1) prototypical contexts involving harm to innocent victims (i.e., no provocation) and (2) more complex social contexts involving harm to previously antisocial victims (i.e., provocation). We focus on children’s responses to another’s unprovoked harm (i.e., when the victim suffers harm without prior instigation) and provoked harm (i.e., when the victim suffers harm following the perpetration of harm) because children’s evaluations, emotional responses, and behavioral tendencies in these contexts will shed light on how they understand and enact justice. We chose to focus on three age groups across the childhood years due to marked shifts in children’s emotional and moral development (e.g., moral responses to aggression and harm to victims, increases in sympathy development; Jambon & Smetana, Reference Jambon and Smetana2014; Kienbaum, Reference Kienbaum2014) and due to typical decreases in aggressive behavior (Girard et al., Reference Girard, Tremblay, Nagin and Côté2019); thus, age-related differences in our findings may offer insights into both normative and atypical behavioral trajectories and highlight possible windows of intervention.

Our second aim was to delineate whether children’s experiences of sympathy in response to (un)provoked harm may serve as a developmental marker of aggressive behavior challenges. From a constructivist-interactionist perspective, children develop their behavioral repertoires within interactions with others (Dahl et al., Reference Dahl, Martinez, Baxley and Waltzer2022). As such, how children interpret and feel in contexts of conflict shape their schemas and response tendencies, which may influence the trajectory of their aggressive behaviors by either inhibiting or exacerbating externalizing problems. We distinguished between proactive (i.e., pre-meditated) and reactive (i.e., retaliatory) functions of aggression in this study because they have fundamentally different emotion-related antecedents and mental health outcome, thus requiring unique intervention approaches (Acland et al., Reference Acland, Peplak, Suri and Malti2023; Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2019; Jung et al., Reference Jung, Krahé and Busching2017; Pederson et al., Reference Pederson, Fite and Bortolato2018).

The development of children’s sympathy and overt aggression

As with all emotions, sympathy involves both affective and cognitive components. The affective component is characterized by a negative feeling of concern for the welfare of another (i.e., feeling for another), while the primary cognitive features include understanding the suffering other’s circumstance and mental state (see Malbois, Reference Malbois2023). Due to its complexity and moral undertones, sympathy requires a nuanced measurement approach to distinguish it from related emotions such as sadness or empathy. Regarding its development, precursors of concern for others are apparent from the first year of life (e.g., Davidov et al., Reference Davidov, Paz, Roth-Hanania, Uzefovsky, Orlitsky, Mankuta and Zahn-Waxler2021) and children’s capacity for sympathy continues to advance into the childhood years alongside sensitive and responsive caregiving (Paulus et al., Reference Paulus, Becher, Christner, Kammermeier, Gniewosz and Pletti2024) and socio-cognitive growth (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman2000). Specifically, once children enter school and begin spending more time with peers, they develop perspective-taking and emotion-regulation capacities that allow them to better understand themselves and others.

Children experience and observe conflicts that help them learn about others’ needs as well as the causes and consequences of harmful actions (Carlo et al., Reference Carlo, Padilla-Walker and Nielson2015; Kienbaum, Reference Kienbaum2014). According to the social domain and empathy-based theories of moral development (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Zuffianò and Spinrad2024; Smetana, Reference Smetana and Zelazo2013), the distress of a victim evokes empathy-induced guilt and concern in aggressors. Children remember these negative affective consequences and, with support and guidance from caregivers, will likely learn from their harmful actions and refrain from aggressing again (Dahl et al., Reference Dahl, Martinez, Baxley and Waltzer2022; Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Mitrevski, Acland and Malti2022). Indeed, children as young as three report moral transgressions (such as harming someone) as being more wrong than conventional rule-breaks (Yoo & Smetana, Reference Yoo and Smetana2022), likely due to their emotional salience. As such, as children continue to learn from the emotional consequences of their actions and increase in concern for others, they also decline in their overt aggression over time (Zuffianò, Colasante, et al., Reference Zuffianò, Colasante, Buchmann and Malti2018).

Reducing aggression in childhood is of critical importance given that persistent trajectories of aggression into adolescence and adulthood risk violent crime and justice-system involvement (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt1993). Frick and Viding (Reference Frick and Viding2009) argue that those at highest risk of aggression and antisociality persistence show elevated childhood conduct problems with limited prosocial emotions (such as sympathy). As such, investigating childhood aggression may provide important insight into which processes may be most developmentally associated and critical for putting children at risk of following an antisocial path and of serious psychopathological outcomes such as antisocial personality disorder (Whipp et al., Reference Whipp, Korhonen, Raevuori, Heikkilä, Pulkkinen, Rose, Kaprio and Vuoksimaa2019).

Situational versus dispositional sympathy

Different methods (e.g., questionnaires, observations, physiological assessments) and informants (e.g., parents and teachers) have been used to assess sympathy from infancy to adolescence (Yavuz et al., Reference Yavuz, Colasante, Galarneau and Malti2024; Zuffianò, Sette, et al., Reference Zuffianò, Sette, Colasante, Buchmann and Malti2018). Dispositional sympathy refers to a child’s general, trait-like tendency to feel concern for others across time and contexts, while situational sympathy highlights children’s specific, momentary and context-dependent sympathetic responses to a specific event (Zuffianò, Sette, et al., Reference Zuffianò, Sette, Colasante, Buchmann and Malti2018). While children with higher dispositional sympathy are more likely to show sympathetic responses across situations (i.e., indiscriminate concern; Holmgren et al., Reference Holmgren, Eisenberg and Fabes1998), situational sympathy provides unique insight into the ways children respond emotionally to the needs of others in-the-moment – a response that is not fully captured by trait-level assessments that often do not mention context nor target.

Measuring situational sympathy is valuable because it highlights the influence of contextual factors (e.g., the nature of the event, the status and relationship to the person in need, and the presence of social cues) on children’s emotional responses. These momentary experiences of sympathy can reveal a dynamic view of children’s moral development (Zuffianò, Sette, et al., Reference Zuffianò, Sette, Colasante, Buchmann and Malti2018). Whether sympathy is elicited in a given situation is due to a combination of a child’s propensity for feeling concern for others (disposition; likely related to other stable personality factors) combined with their appraisal of the context (situation; Vaish, Reference Vaish2016). Stellar and Duong (Reference Stellar and Duong2023) have argued that context fundamentally shapes the experience of how and whether people feel concern for others, and that decontextualized dispositional measures are “impoverished and lack the richness of everyday experiences” (p. 114). Thus, examining both situational and dispositional facets of sympathy may provide researchers with the insight necessary to better identify moments in which situational sympathy maps onto dispositional tendencies, and to better understand the factors that lead to sympathy development in the early years (see Vaish, Reference Vaish2016).

A common approach to assessing children’s dispositional sympathy is via questionnaire methods asking about general response patterns (either self-, parent-, or teacher-report), while situational sympathy is often assessed through in vivo responses to an adult’s pain or distress (e.g., Hepach et al., Reference Hepach, Vaish and Tomasello2013) and to characters’ misfortunes within vignettes (e.g., Holmgren et al., Reference Holmgren, Eisenberg and Fabes1998; Peplak & Malti, Reference Peplak and Malti2022; see Kienbaum, Reference Kienbaum2014 for multi-method, multi-informant approach). There tends to be small-to-moderate convergence across different types of assessments because they all measure a particular context or feature of sympathy that is not holistically captured within one measurement approach (Zuffianò, Sette, et al., Reference Zuffianò, Sette, Colasante, Buchmann and Malti2018). Children’s own reports of sympathy are important to consider because affective processes and interpretations of those processes are subjective and the individual experiencing the emotion is uniquely positioned to speak to the intensity, quality, and nuances of their experiences (Vazire, Reference Vazire2010).

Children’s sympathy following provoked harm

Children’s sympathy has been traditionally assessed in response to the suffering of victims from low-severity accidents (e.g., a parent or researcher hurting their knee; Davidov et al., Reference Davidov, Paz, Roth-Hanania, Uzefovsky, Orlitsky, Mankuta and Zahn-Waxler2021; Zahn-Waxler et al., Reference Zahn-Waxler, Radke-Yarrow, Wagner and Chapman1992) and chronic poverty or illness (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Fabes, Carlo, Troyer, Speer, Karbon and Switzer1992; MacEvoy & Leff, Reference MacEvoy and Leff2012; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Valiente and Eisenberg2003). When children themselves are asked to identify incidents that typically incite sympathy, they report that they feel sorry for innocent victims of aggression (physical, verbal, relational), accidents, and property damage (MacEvoy & Leff, Reference MacEvoy and Leff2012). Harm that results from peer conflict, however, is not as straightforward as reflected in these typical measurement approaches. For example, a victim of harm may have a history of engaging in harmful acts themselves (i.e., a bully who is also a victim; Demaray et al., Reference Demaray, Malecki, Ryoo and Summers2021). As such, how children emotionally respond as witnesses of peer harm often involves incorporating multiple pieces of information, such as the severity of harm, the intentions of the individuals involved, outcomes of harm, and the victim’s prior behaviors and status (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Smetana and Sturge-Apple2017; Smetana et al., Reference Smetana, Campione-Barr and Yell2003; Yoo & Smetana, Reference Yoo and Smetana2022).

Even young children consider the social complexities involved in contexts of harm as can be seen within children’s judgements, reasoning, and emotional responses to aggression and harm to victims (Malti & Ongley, Reference Malti and Ongley2014; Recchia et al., Reference Recchia, Sack and Conto2024). Children show more nuance in their judgements about moral transgressions as they enter middle childhood. Across middle to late childhood, unprovoked acts of aggression are judged to be undesirable and severe (Smetana et al., Reference Smetana, Campione-Barr and Yell2003). However, in more complicated contexts of aggression – where the aggression is provoked or is implemented to prevent future harm to a victim – children appear to show increasing preferences for harm reduction as they age (perhaps due to parallel increases in sympathy; Zuffianò, Colasante, et al., Reference Zuffianò, Colasante, Buchmann and Malti2018). For example, older children (7–8 years) tend to find provoked acts of aggression less morally justified than younger children (6 years; Smetana et al., Reference Smetana, Campione-Barr and Yell2003). Similarly, in 5- to 11-year-olds, older children are more likely to morally excuse aggression (but still regard it as wrong) if the act is needed to prevent further harm (Jambon & Smetana, Reference Jambon and Smetana2014). Relatedly, in the context of bullying (Gönültaş et al., Reference Gönültaş, Mulvey, Irdam, Goff, Irvin, Carlson and DiStefano2020), older youth (9th graders) report bystander intervention to be more acceptable and victim retribution to be less unacceptable than younger adolescents (6th graders). Thus, with age and across more complex social contexts, it appears that children tend to prefer outcomes that emphasize harm reduction compared to younger children.

This developmental trend is reflected in increasing considerations of “just desserts” in retributive and distributive justice decisions across 4 to 11 years of age (Smith & Warneken, Reference Smith and Warneken2016). Perhaps that is why, as children age, they more selectively extend their sympathy to others based on their antisocial past (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lilienfeld and Rochat2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhou, Zhu and Su2024) – that is, they may withhold concern for prior aggressors as a social signal to alert the antisocial victim that their prior behaviors were wrong (Schindler et al., Reference Schindler, Körner, Bauer, Hadji, Rudolph and Allen2015) and that justice ought to be upheld in interactions with others to prevent future harm (Helwig & Turiel, Reference Helwig and Turiel2002; McAuliffe et al., Reference McAuliffe, Jordan and Warneken2015; Piaget, Reference Piaget1932).

Research on how children emotionally respond to different contexts of harm across childhood is very limited, and it remains unclear whether contextually selective sympathy translates to children’s own context-dependent aggression. Given that moral justifications and sympathy advance during middle-to-late childhood, in this study, we investigated how children’s (6-, 9-, and 12-year-olds) emotional responses to (un)provoked harm of peers differ between ages and how their contextually sensitive sympathy relates to their own uses of aggression.

Proactive and reactive functions of overt aggression

We focus on two functions of overt aggression (i.e., direct aggression via physical force or the threat of force; Coie & Dodge, Reference Coie and Dodge1998): proactive and reactive. Proactive aggression is conceptualized as “cold-blooded” aggression that is goal-directed and calculated in nature. Children who engage in proactive aggression typically harm others to achieve a certain objective (Card & Little, Reference Card and Little2006) and as such, tend to have worse morally relevant skills in the domains of moral reasoning (Baker & Liu, Reference Baker and Liu2021), emotion recognition (Acland et al., Reference Acland, Peplak, Suri and Malti2023), and sympathetic responding (Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2019, Reference Jambon, Colasante, Mitrevski, Acland and Malti2022; Zuffianò, Colasante, et al., Reference Zuffianò, Colasante, Buchmann and Malti2018). Reactive aggression is “hot-blooded” and retaliatory in nature. Children who engage in reactive aggression typically lash out with hostility in response to perceived offenses or provocations (Card & Little, Reference Card and Little2006). Due to its impulsive nature, children who display reactive aggression typically do not experience difficulties in their moral competencies (Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2019; Peplak & Malti, Reference Peplak and Malti2017; but see Mayberry & Espelage, Reference Mayberry and Espelage2007) – rather, their aggression tends to stem from cognitive biases (i.e., hostile attribution bias; Dodge, Reference Dodge2006), emotion dysregulation (Hubbard et al., Reference Hubbard, McAuliffe, Morrow and Romano2010), and justice and rejection sensitivity (Bondü & Krahé, Reference Bondü and Krahé2015). Although these subtypes of aggression tend to co-occur, they are meaningfully and statistically distinct (van Dijk et al., Reference van Dijk, Hubbard, Deschamps, Hiemstra and Polman2021) and underlie different developmental trajectories and pathways toward maladaptive outcomes (Hubbard et al., Reference Hubbard, McAuliffe, Morrow and Romano2010; Vaughan et al., Reference Vaughan, Speck, Frick, Walker, Robertson, Ray, Wall Myers, Thornton, Steinberg and Cauffman2023).

Little is known about how children’s sympathy in contexts involving provoked harm may be differentially related to these two functions of overt aggression. Prior work shows some indication that aggressive children may think and feel about retaliation differently. For example, violent youth are more likely to condone retaliation as a response to provocation compared to non-violent peers (Astor, Reference Astor1994). Relatedly, in a longitudinal study, McDonald and Lochman (Reference McDonald and Lochman2012) showed that revenge motivation was associated with the belief that aggression is an effective strategy to solve problems, and predicted higher levels of reactive aggression in children and youth. Reactively aggressive children may believe that retaliation will stop the victimizer’s attacks (Pardini & Byrd, Reference Pardini and Byrd2012), which may motivate them to seek retributive justice; however, this puts them at risk of developing greater tolerance toward and acceptance of aggression. Thus, although reactively aggressive children may not struggle with exercising their sympathy in unprovoked contexts of harm, this evidence suggests that their sympathy may be attenuated when provocation is involved. Conversely, while proactively aggressive children approve of aggressive responses more than reactively aggressive children (Orobio de Castro et al., Reference Orobio de Castro, Merk, Koops, Veerman and Bosch2005), they may be generally less affected by others’ intentions and may experience lapses in sympathy regardless of provocation. In this study, we tested whether children’s sympathy following provoked versus unprovoked harm of a peer was differentially linked to their engagement in proactive and reactive overt aggression.

Present study

This study had two aims. First, we examined age-related differences in children’s sympathy following provoked (i.e., harm that resulted from prior provocation) compared to unprovoked harm (i.e., harm with no mention of prior provocation). We expected children to report lower levels of sympathy in the provoked harm context compared to the unprovoked harm context (Schindler et al., Reference Schindler, Körner, Bauer, Hadji, Rudolph and Allen2015; Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Rudolph, Tscharaktschiew and Rudolph2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhou, Zhu and Su2024). Regarding age-related differences, unprovoked overt aggression is believed to be equally severe and unjustified by children across mid-to-late childhood; however, children advance in their propensity to experience sympathy over childhood and into adolescence (e.g., Kienbaum, Reference Kienbaum2014). Thus, we anticipated that sympathy would increase across age groups in the unprovoked harm context. Further, given research suggesting that older children feel less concern for victims with an antisocial past, we expected that sympathy would decrease across age groups in the provoked harm context (e.g., Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhou, Zhu and Su2024). Though not a primary focus, we also considered the effect of gender and expected that girls would show stronger sympathy across contexts than boys given that caregivers more strongly emphasize care-based socialization strategies when raising girls compared to boys in Western contexts (Chaplin & Aldao, Reference Chaplin and Aldao2013).

Second, we investigated whether children’s sympathy following provoked and unprovoked harm were differentially associated with their proactive and reactive overt aggression. We focused on overt aggression due to its associations with life-course persistent antisocial behavior (Di Giunta et al., Reference Di Giunta, Pastorelli, Eisenberg, Gerbino, Castellani and Bombi2010). We considered children’s dispositional sympathy (child- and parent-reported) as a comparison measures of sympathy as it reflects unique aspects of children’s sympathetic responding. We hypothesized that sympathy in the provoked harm context would be negatively related to reactive aggression given that a lack of sympathy in this context may reflect endorsement of retaliation which is characteristic of reactive aggression (Bondü & Krahé, Reference Bondü and Krahé2015; McDonald & Lochman, Reference McDonald and Lochman2012). We expected sympathy in both contexts to be negatively associated with children’s proactive aggression given that proactive overt aggression is related to callousness (i.e., lack of sympathy; Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2019; Peplak & Malti, Reference Peplak and Malti2017). Similarly, replicating prior work, we expected both parent- and child-reported dispositional sympathy to be negatively associated with children’s proactive aggression (Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2019). Within exploratory mutligroup models, we anticipated that associations between dispositional sympathy and aggression would become stronger with age because as children grow older, they develop greater awareness of others’ emotions and moral standards, which makes sympathy a stronger inhibitor of aggression (Tampke et al., Reference Tampke, Fite and Cooley2020). We included gender as a covariate in our model as boys tend to behave more aggressively than girls (Card et al., Reference Card, Stucky, Sawalani and Little2008).

Method

Participants

A community sample of 186 6-year-olds (M age = 6.23 years, SD = 0.66, 47% girls, n = 64), 9-year-olds (M age = 9.22 years, SD = 0.60, 51% girls, n = 59), and 12-year-olds (M age = 12.16 years, SD = 0.61, 48% girls, n = 63) and their primary caregivers (95.1% biological parent; 83.3% women) participated (we use the label “parents” throughout rest of the manuscript). Participants were recruited from multiple communities across southern Ontario via schools, community centers, and through a previously existing database available at the researchers’ institution. Parents reported diverse ethnic backgrounds, including Western European (23%), Eastern European (13%), West or Central Asian (3%), South or South-East Asian (10%), East Asian (8%), Caribbean and South American (5%). A portion self-identified as White or North American (20%), and some reported being of mixed or other ethnicities (4%). Fourteen percent did not report their ethnic origin. Ethnic origins were similar across age groups. Parents reported their highest completed level of education, with the majority being university or college graduates (59.2%), followed by postgraduates (Master’s and Ph.D.; 18.8%), high school graduates (6.5%), trades school graduates (0.5%), and not having a diploma (0.5%). Fifteen percent did not report their education. According to population data regarding ethnicity and education, the sample was representative of the community in which the study took place (Statistics Canada, 2017).

Our sample size was chosen based on prior research showing small–moderate effects of moral emotions on social behavior (Malti et al., Reference Malti, Peplak and Zhang2020; Malti & Krettenauer, Reference Malti and Krettenauer2013). Power sensitivity analyses (via G*Power 3.1; Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009) indicated a minimum detectable effect size of f 2 = .06 for an ANOVA with 3 groups via the following specifications: α = .05, N = 186, Power = 0.80. The minimum detectable effect size for a multivariate multiple regression with 7 predictors and 2 tested predictors (× 2 DVs) was f 2 = 0.07 via the following specifications: α = .05, N = 186, Power = 0.80. The rule of thumb for multigroup modeling, within the structural equation modeling framework, typically requires 100 cases per group (at least 10 observations per parameter to be estimated; Kline, Reference Kline2005). While our models were simple and used observed variables (Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Harrington, Clark and Miller2013), we are cautious in our interpretations as our samples per group were small given our expected small-moderate effects.

Procedure

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Toronto (protocol #35578). We obtained written informed consent from children’s primary caregivers and verbal assent from children prior to study commencement. Children participated in a ∼30-minute individual interview at either the research lab (55%) or in their school (45%). Trained graduate and undergraduate psychology research assistants conducted the study sessions. We did not find story order effects on children’s emotions in our pilot study (n = 49) across four tested randomizations; thus, we presented children with stories in a fixed order: provoked harm (physical harm) → unprovoked harm (prosocial omission) → provoked harm (prosocial omission) → unprovoked harm (physical harm). Children engaged with other vignettes in between each of these stories such that the provoked and unprovoked harm stories were never presented back-to-back. All interviews were audio or video recorded for data transcription purposes. Primary caregivers completed questionnaires about their demographics and children’s social behavior. Children received an age-appropriate book at the end of the study as a gift. All children were debriefed and thanked for their participation.

Measures

Emotions and reasoning

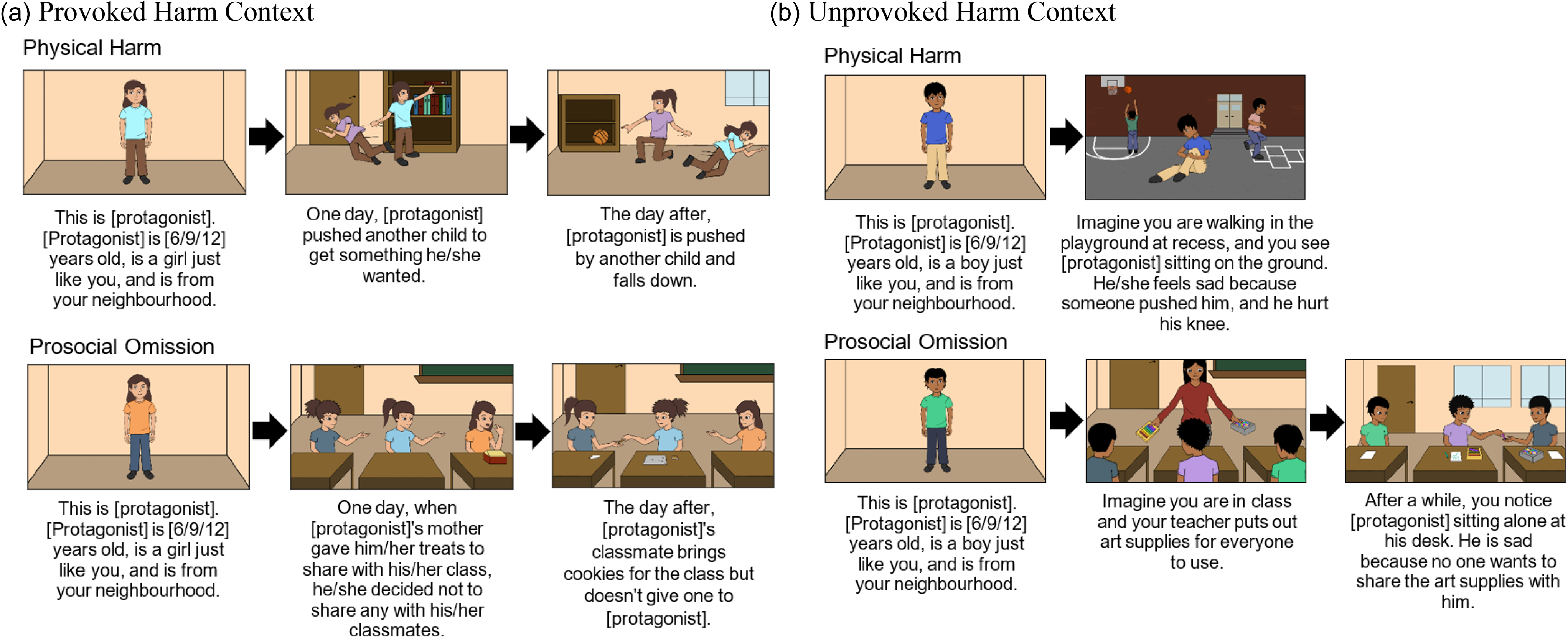

We developed and employed a vignette procedure whereby children provided their spontaneous emotions (and reasoning for those emotions) in response to a hypothetical child who experienced provoked or unprovoked harm (see Mayberry & Espelage, Reference Mayberry and Espelage2007 for similar approach). Our open-ended approach limits reporting biases associated with close-ended questions and allows for the examination of emotions as they might naturally occur in children’s interactions with their peers (rather than restricting their choice to pre-identified emotions; Stengelin et al., Reference Stengelin, Haun and Kanngiesser2023). Children’s emotions and reasoning were assessed in four vignettes – two in the context of provoked harm and two in the context of unprovoked harm (one physical harm and one prosocial omission). Physical harm and prosocial omissions were our chosen transgressions as we were interested in understanding children’s responses across both prescriptive and proscriptive norms (see Malti et al., Reference Malti, Gummerum, Keller and Buchmann2009; Weller et al., Reference Weller and Hansen Lagattuta2013). Provoked harm vignettes displayed a protagonist committing a transgression and later being harmed in the same way by the former victim. The unprovoked harm context displayed a protagonist experiencing harm without any reference to prior provocation. Each vignette was accompanied by drawings to aid children’s comprehension of story events (see Figure 1 for examples of vignettes). The gender and skin tone of the protagonist was matched to the participant to limit potential intergroup confounds. We introduced the target character, named them, and included their name in our questions to ensure children’s responses were directed toward the target of interest and not other characters.

Figure 1. Vignettes designed to elicit children’s emotions and reasoning following (a) provoked and (b) unprovoked harm. Note. (a) = provoked harm vignettes involved the harm to a peer who engaged in a similar harmful act the day prior. (b) = unprovoked harm vignettes involved the harm to a peer without mention of their prior behavior.

Children’s spontaneous emotional responses were assessed following each vignette (“how would you feel if that happen to [protagonist]?”). When interviewing 6-year-old participants, research assistants would point to the characters in the story as they referenced them to reduce potential confusion. We also provided an emotion scale (6 drawings of faces depicting expressions of neutrality, happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, and fear) to help children describe their emotional experiences; however, participants were instructed that they do not need to use the scale and could report other emotions that were not presented. We labeled the emotions on the scale prior to use. Six-year-olds were tested on the emotions before the use of the scale to ensure comprehension. Participants reported up to two emotions and were prompted by the interviewer following their first reported emotion: “Is there any other emotion you would feel?” Participants were then asked why they would feel each emotion (i.e., reasoning; “why would you feel [emotion]”?) and how strongly they would feel that emotion (i.e., emotion intensity) on a scale from 1 (not much) to 3 (very much).

Emotion coding

Two to 12% of children across stories who did not use our emotion scale reported a sadness-related emotion (i.e., bad, upset, sorry for him/her). These emotions were lumped together with sadness responses due to their conceptual similarity and according to previous similar approaches (Dys et al., Reference Dys, Peplak, Colasante and Malti2019; Malti et al., Reference Malti, Gummerum, Keller and Buchmann2009). A substantial proportion of children reported two emotions in response to the vignettes (about 40% in response to provoked and 33% in response to unprovoked harm); thus, both first- and second-reported emotions were coded and considered in the analyses. Sadness (as it is the affective root of sympathy) was binary coded into a separate variable within each context (1 = sadness was reported, 0 = sadness was not reported). Scores were then multiplied by children’s reported emotion intensity (score from 1 = not very to 3 = very), resulting in a possible score from 0 (absence of sadness), 1 (low intensity sadness), 2 (moderate intensity sadness), and 3 (high intensity sadness).

Reasoning coding

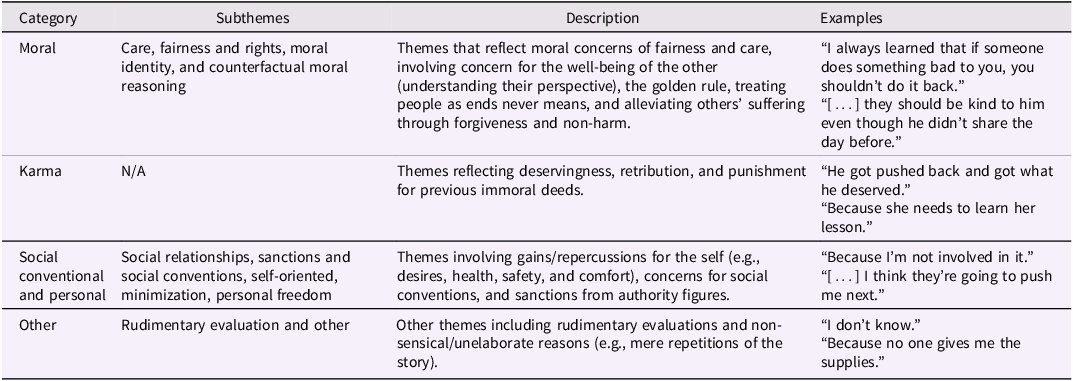

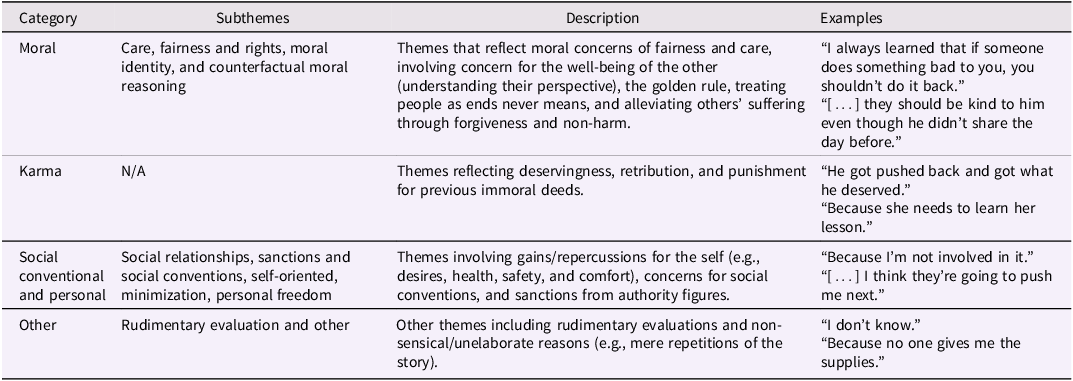

Reasoning data was coded using previously developed schemes that measure children’s reasoning for their emotions in morally relevant contexts (e.g., Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Mitrevski, Acland and Malti2022). We employed a codebook thematic analysis approach and themes were refined or added through the inductive data technique (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021). Responses were categorized into: (1) care (e.g., “I know how it feels and it’s not good”), (2) fairness and rights (e.g., “It’s unfair to them”), (3) moral identity (e.g., “I do not feel as though I’m that kind of person”), (4) counterfactual moral reasoning (e.g., “I can just tell them to take turns sharing the book rather than pushing each other”), (5) karma (e.g., “He got pushed back and got what he deserved”), (6) social relationships (e.g., “The other boy won’t be my friend anymore”), (7) sanctions and social conventions (e.g., “The teacher will find out and get angry”), (8) self-oriented (e.g., “because I want to play with the ball”), (9) minimization (e.g., “It’s not my problem so I don’t care”), (10) personal freedom (e.g., “I guess it’s hers so she doesn’t really have to share”), (11) rudimentary evaluation (e.g., “because it’s mean”), and (12) other. A random subsample of responses (i.e., 20% of the data) was independently coded by two research assistants to calculate inter-coder reliability. Reliability was excellent across stories (κ = 0.95). Disagreements were discussed and consensus was attained for the final coding.

Categories were collapsed to reflect overarching themes of “moral” (including subcategories of care, fairness and rights, moral identity, and counterfactual moral reasoning), “personal and societal concerns” (including subthemes of self-oriented reasoning, social relationships, sanctions and social conventions, personal freedom, and minimization) and “other” (i.e., rudimentary evaluation and other). See Table 1 for category descriptions and prototypical examples. Children were prompted for elaborations (e.g., “what else can you tell me?”; “why is it [rudimentary evaluation] not to share?”) if their initial reasoning was unelaborate or contained a rudimentary evaluation (e.g., “because it’s mean”). The presence (1) or absence (0) of reasoning types within each story (out of two potential lines of reasoning for each emotion) were binary coded into individual variables. Scores were averaged across stories within contexts (possible scores 0.0, 0.5, and 1.0) to run preliminary analyses regarding the overall trajectories of moral reasoning across age groups. Moral reasoning and karma reasoning were the foci within our preliminary descriptive analyses as they were the most prominent categories used across stories by children. Only moral reasoning was included in our sympathy coding as per prior research protocols (see below).

Table 1. Coding scheme for reasoning following (Un)Provoked harm

Sympathy coding

As recommended by related research (e.g., Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2019), we combined children’s intensities of reported sadness with their moral reasoning to create a sympathy variable. This method of calculation reflects children’s sympathetic concern for others as it filters out feelings of sadness that are directed at non-moral facets of the situation (e.g., sadness due to social conventional or self-focused reasons). We multiplied the intensity of sadness (score from 0 to 3) by the presence or absence of moral reasoning (1 = moral reasoning present within the first or second line of reasoning, 0 = moral reasoning absent) within each story, resulting in a possible intensity score from 0 (no sympathy reported) to 3 (strong sympathy reported). Scores for each story (physical harm and prosocial omission) were then averaged within contexts as we were interested in children’s general sympathetic responding rather than harm-specific effects. Stories within contexts were positively correlated (r = .23, p = .002 in the provoked harm context and r = .51, p < .001 in the unprovoked harm context). We computed two variables that reflected children’s intensity of sympathy (i.e., sadness supported by moral reasoning) that varied by context: (1) sympathy in response to provoked harm and (2) sympathy in response to unprovoked harm.

Dispositional sympathy (child- and parent-reported)

Children reported on their general tendency to feel sympathy for others on a 3-point scale (1 = not like me, 2 = sort of like me, 3 = really like me) using 5-items (“When I see another child who is hurt or upset, I feel sorry for them”; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Valiente and Eisenberg2003), McDonald’s ω = .76. Parents rated children’s sympathy using the sympathy subscale from the Holistic Student Assessment adapted for parent report (4 items) on a 7-point scale from 1 = never to 7 = always (e.g., “When he/she sees another kid who is hurt or upset, he/she feels sorry for them”; Malti, Zuffianò, et al., Reference Malti, Zuffianò and Noam2018), McDonald’s ω = .86. Items were averaged within child- and parent-reports for analyses.

Overt aggression

We assessed children’s proactive and reactive overt aggression via parent-reports using previously validated scales from Little and colleagues (Reference Little, Jones, Henrich and Hawley2003). Parents rated how true each item was for their child on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 6 (always true).

Proactive aggression

Overt proactive aggression was examined using three items: “Often hits, kicks, or punches others to get what he/she wants”, “often threatens others to get what she/he wants”, and “often starts fights to get what she/he wants.” McDonald’s ω = .84. Items were averaged to create a composite score of proactive aggression.

Reactive aggression

Overt reactive aggression was examined using three items: “When hurt by someone, often fights back”, “When threatened by someone, often threatens back”, “Often hurts others who make him/her mad or upset.” McDonald’s ω was .86. Items were averaged to create a composite score of reactive aggression.

Missing data

A relatively small amount of data was missing (range = 0–15%). Data were missing for proactive and reactive aggression (14.0%; n = 26), parent education (n = 27, 14.5%), sympathy in the unprovoked harm context (n = 1, 0.5%), and parent-reported sympathy (n = 26, 14%) due to some parents not completing the parent questionnaire. Little’s MCAR (missing completely at random) test conducted on all study variables was non-significant, χ2 (8) = 4.34, p = .83. This indicates that the pattern of missing data was not associated with observed scores across the study variables. Nevertheless, the data were handled using the Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimator available in Mplus (Kelloway, Reference Kelloway2015).

Data analytic strategy

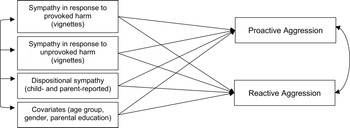

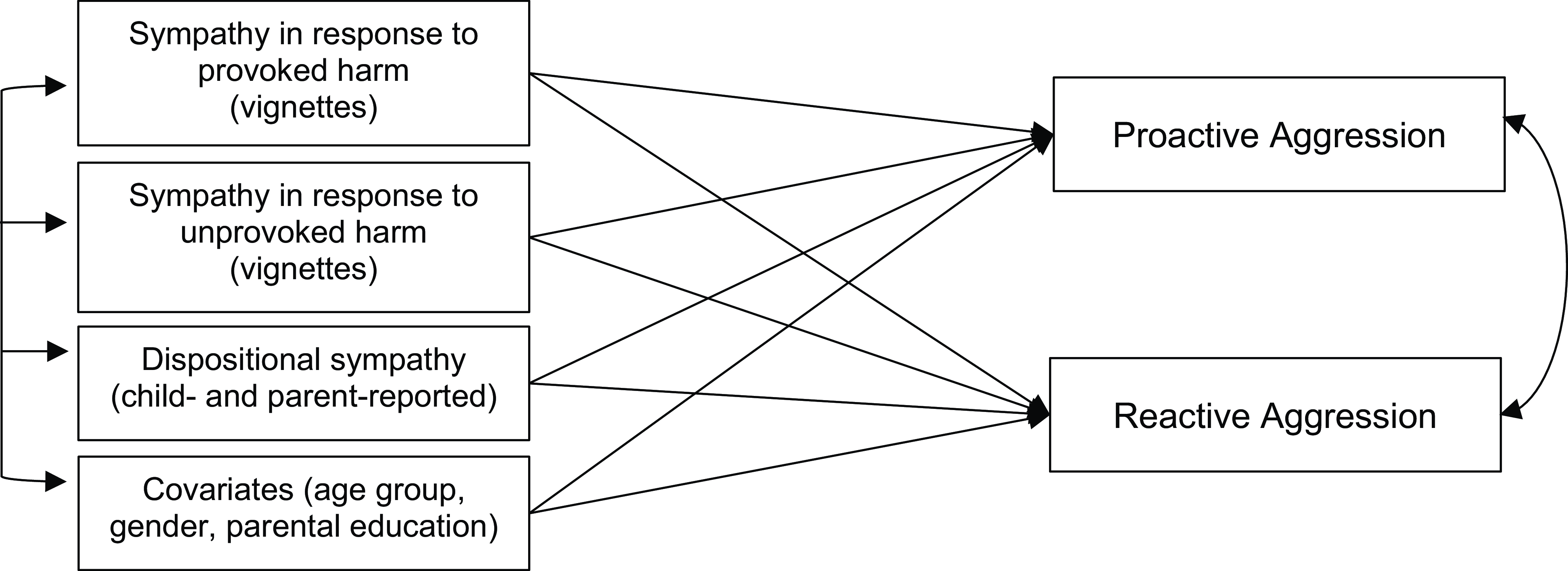

First, we ran box plots to examine potential outliers in children’s proactive and reactive aggression and their emotion scores. Descriptive statistics were conducted to examine means, standard deviations, and bi-variate correlations among study variables. Two MANOVAs were conducted to test age group and gender differences across the two aggression subtypes, and gender differences across the two sympathy scores. We tested bivariate correlations between our main measures of sympathy (within vignettes involving provoked and unprovoked harm) and dispositional assessments of sympathy (child- and parent-reported) to assess their convergent validity. We conducted a repeated-measures ANOVA (with Bonferroni correction) to assess our hypothesis regarding context (within-group factor) and age-group differences (between-group factor) in sympathy. To test our second hypothesis, we assessed sympathy-aggression links within a simultaneous path model (see Figure 2 for conceptual model). We included proactive and reactive aggression as our dependent variables, which allowed us to explicitly test whether sympathy within each context of harm would be more strongly associated with one form of aggression compared to the other (see Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2019 for similar approach). We explored age group (6- vs., 9- vs., 12-year-olds) differences in links between sympathy and aggression using multigroup comparisons (chi-squared difference tests between constrained and freely estimated models). We included our two dispositional sympathy assessments to shed light on state-trait associations between sympathetic responding and aggression. We also included gender and parental education as covariates in our models because these variables have been found to reliably predict children’s aggression (with girls and children of more educated parents tending to be less aggressive; Benenson et al., Reference Benenson, Gauthier and Markovits2021; Zuffianò, Colasante, et al., Reference Zuffianò, Colasante, Buchmann and Malti2018). Data cannot be shared for ethical reasons as participants did not consent to having their data made available on a repository at the time of participation. Data and materials may become available upon reasonable request. All analysis code and output files are shared on Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/f7nur/?view_only=45feaf206e1044469b991936b1065e9d

Figure 2. Conceptual model of the association between children’s sympathy and proactive and reactive aggression.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Data were initially screened for outliers. One outlier was identified such that one 9-year-old scored 4.61 standard deviations (SDs) above the mean for proactive aggression. Our analyses for study aim two were conducted with and without this participant’s proactive aggression data. Beta weights, standard errors, and confidence intervals did not substantially change with and without this participant; thus, this participant’s data was retained for our final results.

Rates of emotions and reasoning (moral and karma) across stories (physical harm and prosocial omission) and context (unprovoked and provoked harm) are depicted in the Online Supplementy (Figure S1). When aggregated across stories, reports of sadness were nearly twice as prevalent in the unprovoked harm context (64%) compared to the provoked harm context (38%). Children often reported feeling neutral as observers of provoked harm (26%) but rarely reported neutrality in the unprovoked harm context (6%). Anger was present in both contexts to a similar degree – 15% in the provoked harm context and 17% in the unprovoked harm context. Interestingly, children rarely reported happiness (i.e., schadenfreude) in the provoked harm context (7%), despite this context having characteristic features that elicit schadenfreude (Schindler et al., Reference Schindler, Körner, Bauer, Hadji, Rudolph and Allen2015). Regarding reasoning, we found high rates of moral reasoning (76%) and very low rates of karma reasoning (2%) in the unprovoked harm context, whereas rates of karma reasoning in the provoked harm context were slightly higher (47%) than rates of moral reasoning (43%). Children did not often use social conventional and personal reasoning across contexts (< 15%).

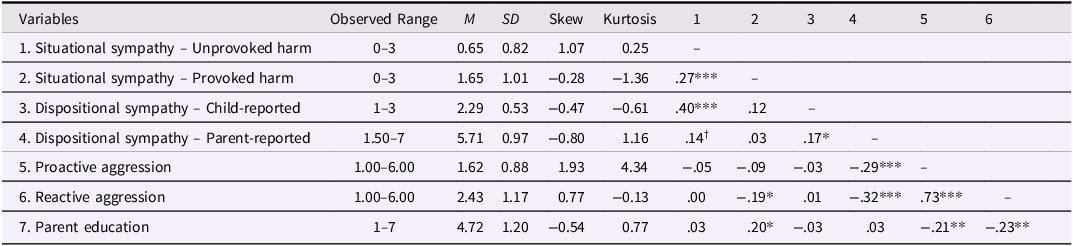

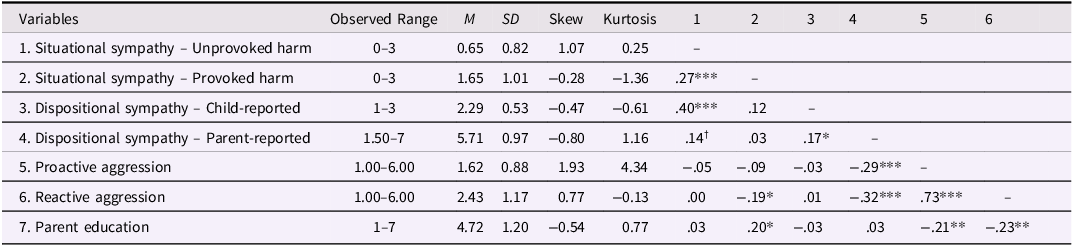

Table 2 displays observed ranges, means, standard deviations (SDs), skewness and kurtosis, and bivariate correlations of all study variables. Situational sympathy (i.e., computed variable including sadness intensity × moral reasoning) was positively correlated across (un)provoked contexts. Sympathy in the provoked harm context was negatively correlated with reactive aggression and positively correlated with parent education. Parent-reported dispositional sympathy was significantly positively correlated with child-reported dispositional sympathy overall. Parent-reported sympathy was not significantly associated with situational sympathy (in either context) across or by age group. Parent-reported (but not child-reported) dispositional sympathy was negatively associated with proactive and reactive aggression. Proactive and reactive aggression were strongly positively correlated. Parent education was negatively correlated with both types of aggression. We did not find any significant differences in proactive nor reactive aggression across age groups nor across gender; however, parents rated children to be significantly more reactively aggressive than proactively aggressive, F(2,153) = 352.95, p < .001, ηp 2 = .82. We did not find significant effects of gender on situational sympathy (within vignettes). Child-reported dispositional sympathy showed significant age-related increases across age groups, F(2,153) = 16.38, p < .001, ηp 2 = .18. Both child- and parent-reported sympathy differed by gender, F(1,153) = 4.17, p = .04, ηp 2 = .03, F(1,153) = 5.45, p = .02, ηp 2 = .03, respectively, such that girls rated themselves and were rated by their parents as being more sympathetic than boys.

Table 2. Observed range, means (M), standard deviations (SDs), distribution statistics and bivariate correlations of continuous study variables

† p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

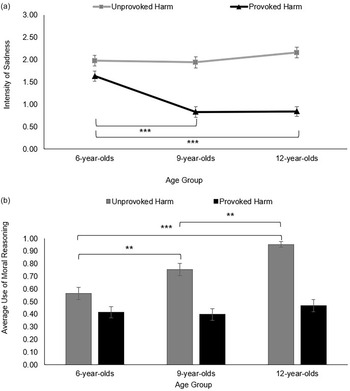

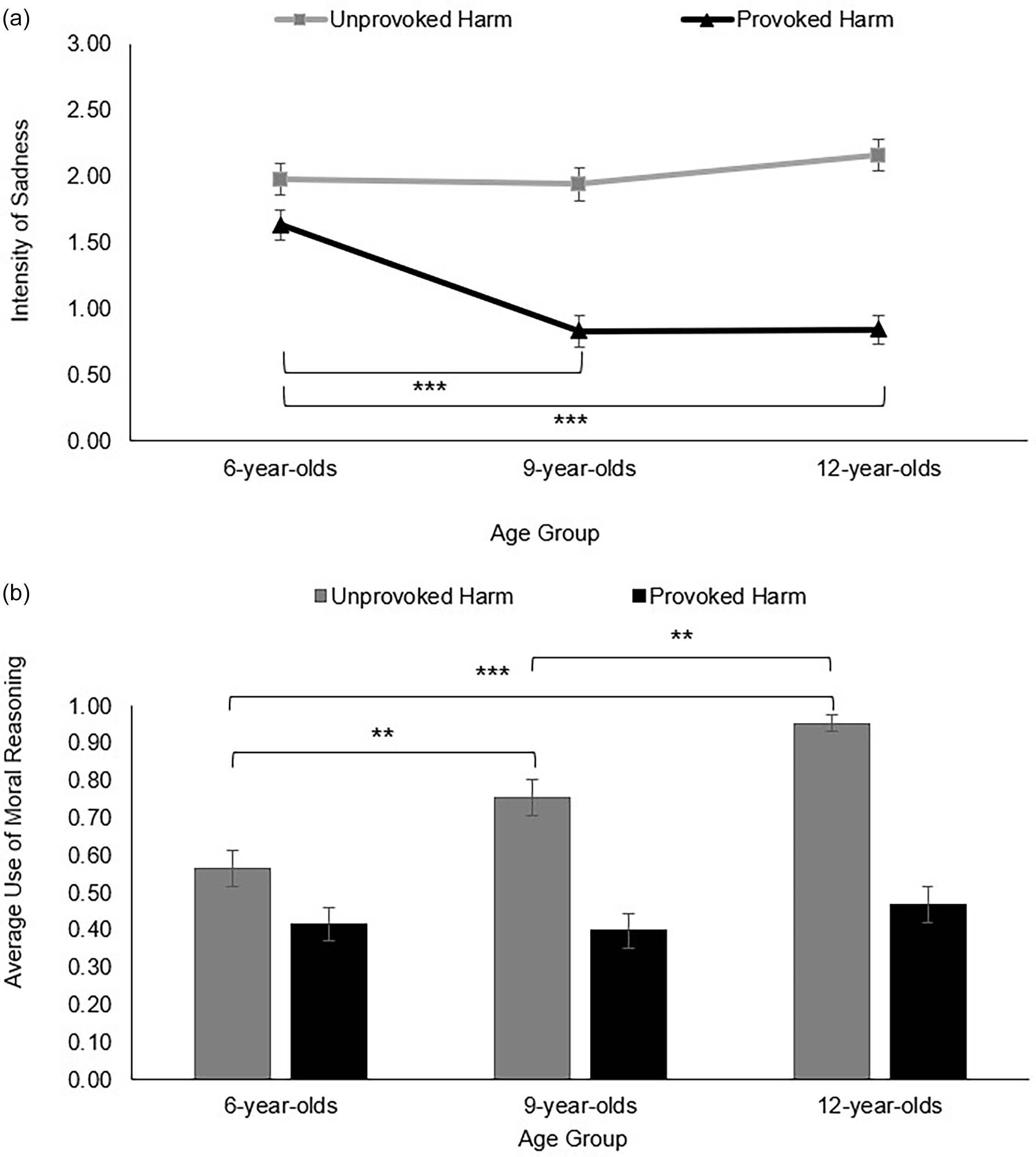

Children’s sadness and moral reasoning by age and context

We first examined age group and context differences in children’s sadness and moral reasoning to better understand which facet of sympathy (affect or cognition) may drive change across age (see Figure 3). We found that children in general reported higher sadness in the unprovoked harm context than the provoked harm context, Wilks’ λ = .52, F(1, 183) = 166.62, ηp 2 = .48, p < .001, M diff = -0.92, SE = 0.07. We found a significant between-subjects effect of age group on intensity of sadness across contexts, F(2,183) = 4.76, ηp 2 = .05, p = .01, whereby 6-year-olds reported stronger sadness on average than 9-year-olds (p = .01). This effect was qualified by an age group by context interaction, F(2,183) = 17.52, ηp 2 = .16, p < .001. Specifically, 6-year-olds reported more intense sadness than 9- (M diff = 0.80, SE = 0.16) and 12-year-olds (M diff = 0.79, SE = 0.16) in the provoked harm context only, ps < .001.

Figure 3. Average (a) intensity of sadness and (b) use of moral reasoning by context and age group. Note. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean. Moral reasoning scores ranged from 0–1, whereby children who did not use moral reasoning to justify their emotions across stories received a score of 0, those who used moral reasoning in at least one of the stories within each context received a 0.5, and those who used moral reasoning across both stories received a score of 1. **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Similar to our sadness findings, moral reasoning differed by context, Wilks’ λ = .60, F(1, 182) = 121.48, ηp 2 = .40, p < .001, such that children used more moral reasoning in the unprovoked harm context than the provoked harm context (M diff = 0.33, SE = 0.03). We found a significant between-subjects effect of age group on moral reasoning across contexts, F(2, 182) = 9.97, ηp 2 = .10, p < .001, whereby 12-year-olds were more likely to provide moral reasoning compared to 6- and 9-year-olds across contexts (ps < .05). This was qualified by an age group by context interaction, F(2,182) = 11.45, ηp 2 = .11, p < .001, such that the likelihood of using moral reasoning in the unprovoked harm context increased across age groups (6- vs., 9-year-olds: p = .004; 9- vs., 12-year-olds: p = .002; 6- vs., 12-year-olds: p < .001).

Correlations between children’s situational and dispositional sympathy

We examined bivariate correlations between our sympathy measures to assess concordance (see Table 2). Children’s sympathy in the unprovoked harm context was moderately positively correlated with children’s self-reported dispositional sympathy and was not significantly correlated with parent-reported sympathy. Children’s sympathy in the provoked harm context was not significantly correlated with child- nor parent-reported sympathy, suggesting that children’s sympathetic concern in more contentious social contexts is not well-captured by traditional assessments of disposition sympathy. Child- and parent-reported sympathy showed a small, but positive, correlation.

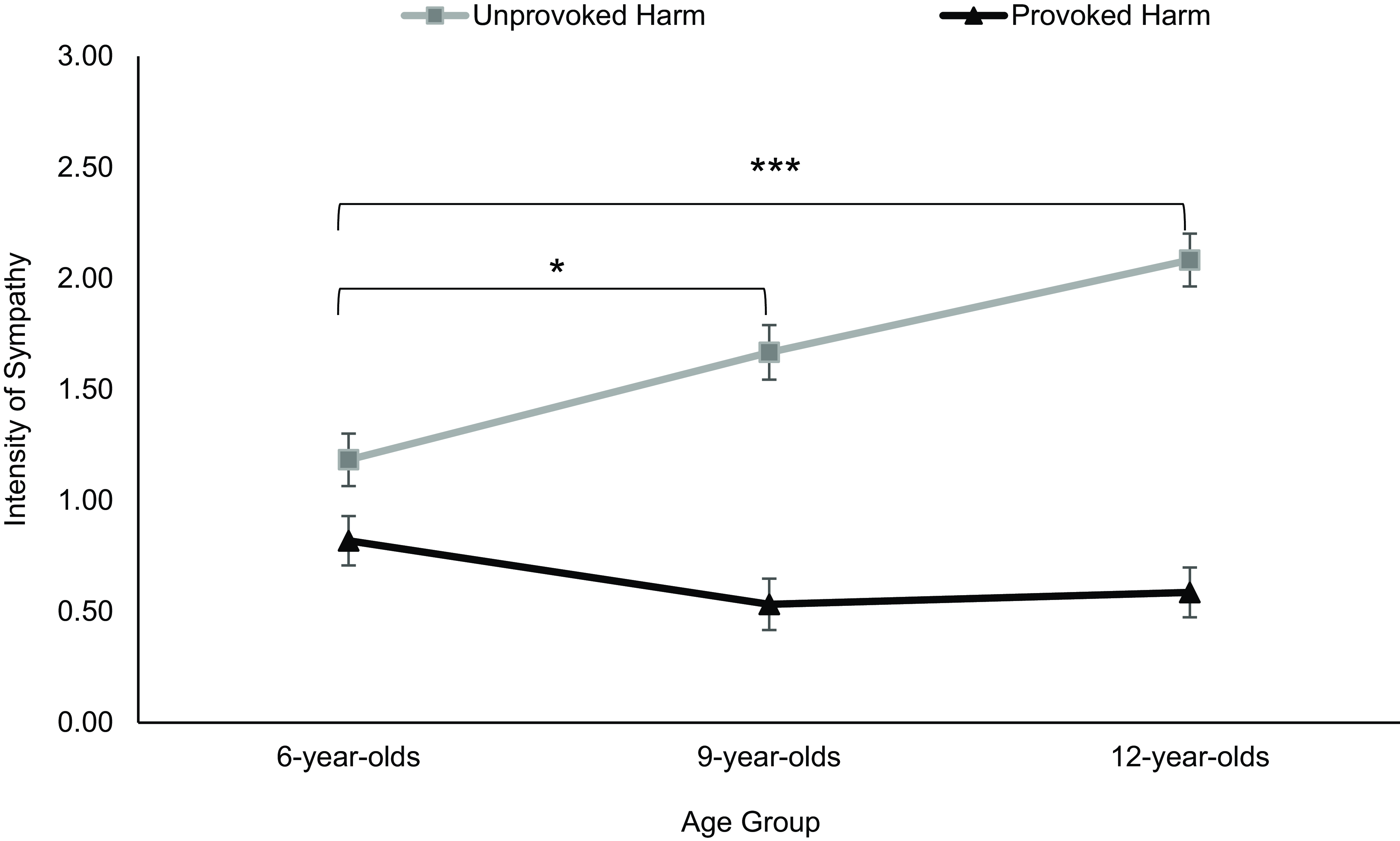

Context and age group differences in situational sympathy

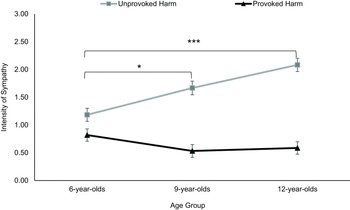

Our repeated measures ANOVA with age-group as a between subjects factor revealed a main effect of context, Wilks’ λ = .54, F(1,182) = 155.43, p < .001, ηp 2 = .46, such that children reported higher levels of sympathy in the unprovoked harm context (M = 1.65, SE = .06) compared to the provoked harm context (M = 0.65, SE = .08). We also found a significant context by age group interaction, Wilks’ λ = .84, F(2,182) = 17.75, p < .001, ηp 2 = .16. Specific age group by context differences are displayed in Figure 4. As expected, sympathy in the unprovoked harm context was significantly higher in older children (12-year-olds and 9-year-olds compared to 6-year-olds). Unexpectedly, sympathy in the provoked harm context remained low across ages and no significant differences were found across age groups.

Figure 4. Age group differences in situational sympathy by context. Note. Post hoc tests used Bonferroni correction. Children’s situational sympathy scores across contexts within each age group were significantly different from one another (6-year-olds p = .009, ηp 2 = .04; 9-year-olds, p < .001, ηp 2 = .26; 12-year-olds ps < .001, ηp 2 = .40). Error bars represent standard errors of the mean. *p < .05, ***p < .001.

Sympathy in response to (un)provoked harm and links with overt proactive and reactive aggression

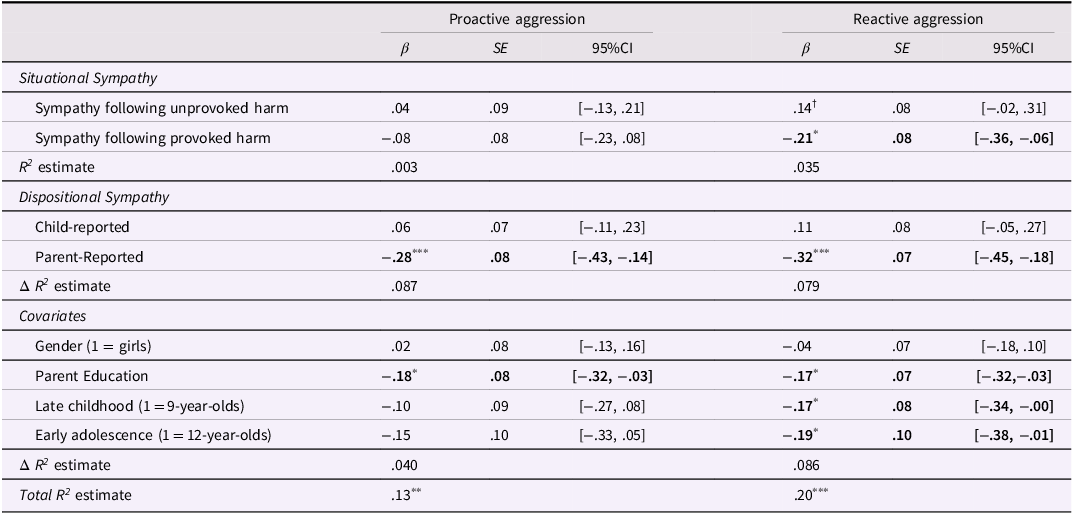

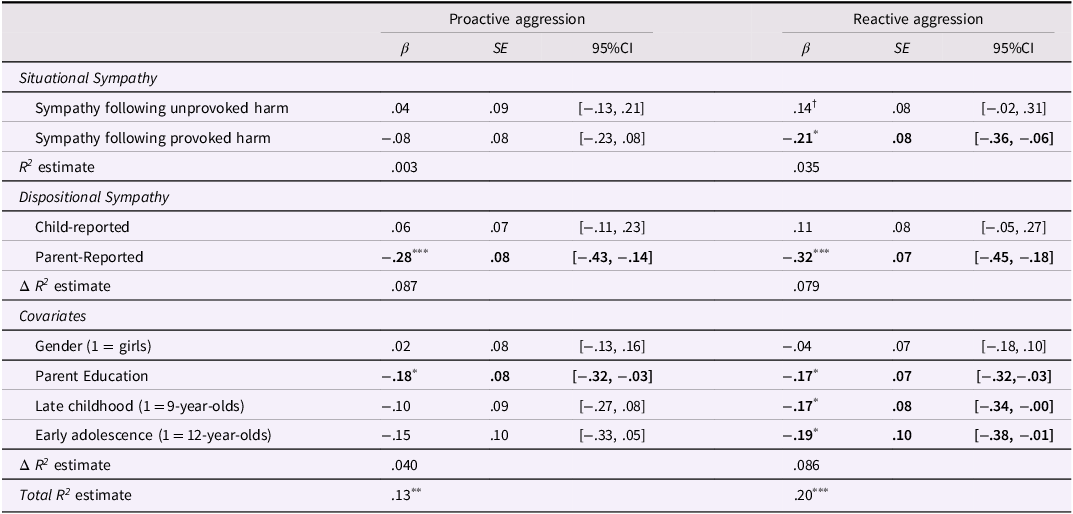

Finally, we examined how sympathy (i.e., sadness combined with moral reasoning) would be uniquely associated with proactive and reactive aggression within a simultaneous path model. As displayed in Table 3, sympathy in response to provoked harm was significantly negatively associated with reactive aggression. Contrary to our expectations, neither sympathy in the unprovoked harm nor the provoked harm context was significantly associated with proactive aggression. Wald’s tests of parameter constraints revealed that sympathy following provoked harm was more strongly associated with reactive aggression than proactive aggression, χ2 (1) = 6.40, p = .011. Parent-reported, but not child-reported, dispositional sympathy was significantly negatively associated with both proactive and reactive aggression. We then conducted exploratory multigroup models to test age-related differences in the associations between sympathy and aggression. Models with paths constrained across age groups compared with models with paths freely estimated were not significantly different (see Online Supplement Table S1). Each sympathy path was tested separately across the two aggression subtypes (four total comparisons). It is important to note that our sample was small across age groups. We also ran our models without the dispositional sympathy measures to ensure that our effects were not altered when including conceptually related constructs (parent- and child-reported dispositional sympathy; see Table S2 in the online supplementy) – the significance of situational sympathy variables on aggression did not change after our dispositional sympathy measures were removed.

Table 3. Sympathy across contexts predicting proactive and reactive aggression

Note. Statistically significant effects are bolded for ease of viewing.

† p < .10, * p < .05, *** p < .001.

Discussion

In this study, we examined differences in children’s feelings of concern (i.e., sympathy) toward victims who engage in prior aggressive behavior compared to innocent victims and elucidated how children’s sympathy toward these targets of harm was associated with their own overt aggression. We showed that children of all ages (6, 9, and 12 years) felt less sympathy for a victim of provoked harm (i.e., a victim who had harmed the perpetrator in the past), while their sympathy for victims of unprovoked harm increased across age groups. We also demonstrated that lower sympathy for victims of provoked harm was associated with children own engagement in reactive aggression (but not proactive aggression). This study highlights sympathy’s potential role in modulating retaliatory tendencies with implications for targeted interventions in aggression-prone youth.

Our first notable finding was that children reported lower levels of sympathy in response to provoked harm of a peer compared to unprovoked harm of a peer. This shows that the extent to which children feel concern for a victim of harm is influenced by the victim’s prior social behavior. This extends Wang and colleagues’ (Reference Wang, Zhou, Zhu and Su2024) findings within a broader age range, showing a similar dampening effect of sympathy toward antisocial others (compared to prosocial others) – a blunting that may underlie children’s desire for punishing perpetrators to achieve fair outcomes (Bernhard et al., Reference Bernhard, Martin and Warneken2020). We showed that children justified their lack of sympathy with karma reasoning (i.e., justifications rooted in concepts of tit-for-tat, deservingness, and punishment) in the provoked harm context, such that children believed harm to prior transgressors was more deserved. Although children tend not to express a desire for revenge following their own social conflicts (e.g., McDonald & Asher, Reference McDonald and Asher2018), their feelings and beliefs about what should occur in others’ conflicts may be different. Indeed, children as young as 3 years of age consider why someone may experience distress and shift their sympathetic responses accordingly (Hepach et al., Reference Hepach, Vaish and Tomasello2013) and by early adolescence, they develop an advanced understanding of reciprocity and deservingness (Wörle & Paulus, Reference Wörle and Paulus2019). As such, early to late childhood may be an important window for the development of deservingness beliefs and a critical time to intervene on maladaptive beliefs that uphold retaliation as an effective conflict-resolution strategy.

One descriptive finding worth noting is that children very rarely reported happiness (i.e., schadenfreude) in response to the provoked harm of a peer. This is surprising given that schadenfreude tends to occur when observers perceive harm to be deserved (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lilienfeld and Rochat2019). Wang and colleagues (Reference Wang, Zhou, Zhu and Su2024) found similar findings using an open-ended response format assessing children’s sympathy and schadenfreude in response to the plight of antisocial puppets. These findings may reflect a potential strength of using open-ended approaches (rather than forced-choice response formats) when assessing children’s emotions, such that children can report the emotion that they truly feel rather than an emotion that researchers anticipate they would feel (likely increasing the ecological validity of the assessment). It is possible that the story context was not one that typically incites schadenfreude in children. If the victim was someone the participants had a contentious personal relationship with where dislike or envy were present, observing their suffering may have evoked feeling of schadenfreude (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Powell, Combs and Schurtz2009). Nevertheless, lacking sympathy (i.e., expressing apathy) may still be concerning as it signals emotional blunting – a marker of dehumanization (Bastian & Haslam, Reference Bastian and Haslam2011).

Regarding age differences in children’s feelings of sympathy within our vignettes, we found that sympathy increased across age groups in the unprovoked harm context – an effect that was driven by increases in moral reasoning (not intensity of sad affect) across age. This suggests that, while observing the harm of others incites negative feelings in children of all ages, their understanding of why they feel bad advances and gets better integrated with their affect as children develop. Contrary to our expectations, children’s sympathy remained low across age groups in the provoked harm context. This finding shows that, despite children’s growing capacity to experience and express sympathy toward perceived “innocent” others, their consideration of the target’s prior behavior buffers their experiences and expressions of care for victims. Thus, it may be specifically sympathy toward “undeserved” harm that increases into late childhood, not indiscriminate sympathy as prior research suggests (Kienbaum, Reference Kienbaum2014; Malti et al., Reference Malti, Ongley, Peplak, Chaparro, Buchmann, Zuffianò and Cui2016). Nevertheless, children’s dampened sympathy toward a victim who retaliated may serve a couple of social functions. First, not expressing concern may signal to the transgressor that their prior provocation was not acceptable, and second, not sympathizing may protect children from future harm by preventing a friendship with the provocateur. Nevertheless, not sympathizing with a victim of harm, regardless of their prior behavior, may help legitimize aggression and prioritize the physical safety of certain individuals over others. Ostracizing aggressive children from social groups may also have cascading impacts on children’s future social and cognitive development and peer relationships (Lansford et al., Reference Lansford, Malone, Dodge, Pettit and Bates2010).

An important point to note is that children’s sympathetic responding within our vignettes showed some amount of convergence with children’s own dispositional ratings and parent’s ratings of their sympathy. Only children’s sympathy in the unprovoked harm context and their self-reported dispositional sympathy were moderately positively correlated, suggesting that traditional assessments of sympathy used within questionnaire formats only capture children’s sympathetic responding within straightforward, non-conflictual contexts. Further, parent ratings of children’s sympathy were not significantly correlated with their sympathy in the unprovoked harm context, suggesting either that parents may not be able to accurately report on children’s internal emotional states (as they do not have access to psychological processes unless they are expressed in their presence), that parents report on a certain facet of children’s sympathy (as they only observe their children in particular social contexts), or that their assessments of sympathy measure broader, more latent tendencies (i.e., parents are better able to access and integrate memories of children’s sympathy over time; Kienbaum, Reference Kienbaum2014; Zuffianò et al., Reference Zuffianò, Colasante, Buchmann and Malti2018). Gender differences in sympathy were also only identified when using dispositional measures, as opposed to contextually evoked sympathy. This supports past research suggesting established gender differences in emotions may be a feature of trait measures, while momentary measures do not produce consistent gender differences in emotions (Mauss & Robinson, Reference Mauss and Robinson2009). Beyond informant and trait-state differences, there is a need to integrate assessments of children’s sympathy beyond prototypical contexts involving the harm of innocent and needy others to better capture children’s sympathetic functioning across a range of social situations.

Finally, as expected, we demonstrated that children who reported feeling lower levels of sympathy for the victim of provoked harm (but not unprovoked harm) were more reactively aggressive (as rated by their parents). Reactive aggression is characterized by hostility in response to a real or perceived threat (Mayberry & Espelage, Reference Mayberry and Espelage2007). Prior research has shown that reactive aggression is typically associated with higher emotionality, impulsivity, dysregulated anger, and hostile attribution bias rather than difficulties in morally-relevant skills such sympathizing with others (e.g., Orobio Dodge, Reference Dodge2006; Hubbard et al., Reference Hubbard, McAuliffe, Morrow and Romano2010; Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2019; Tampke et al., Reference Tampke, Fite and Cooley2020; de Castro et al., Reference de Castro, Verhulp and Runions2012). Work examining links between children’s sympathy and reactive aggression has typically measured sympathy at the dispositional level and toward innocent victims in need. Better understanding children’s sympathetic responding in contexts that involve retaliation is important because reactively aggressive children tend to be motivated by revenge and experience high levels of anger in response to injustice and rejection (Bondü & Krahé, Reference Bondü and Krahé2015; Orobio McDonald & Lochman, Reference McDonald and Lochman2012; de Castro et al., Reference de Castro, Verhulp and Runions2012). As such, these children may be particularly sensitive to harms that are provoked and may see aggression as a tool to redress grievances and reinstate justice (Darwall, Reference Darwall2010; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Martin and McAuliffe2021). In Orobio de Castro and colleagues’ (Reference Orobio de Castro, Merk, Koops, Veerman and Bosch2005) study, researchers showed that reactive aggression was uniquely associated with low sadness attributions to transgressors. Taking these findings and our results together, it is possible that more reactively aggressive children may associate more with the act of provocation – an act that reactively aggressive children themselves respond to – and have a difficult time integrating the emotions of all actors involved in the aggression event. Our study highlights that sympathy should not be overlooked when aiming to address children’s reactive aggression in interventions.

Surprisingly, we did not find any associations between sympathy in the unprovoked nor the provoked harm context and children’s proactive aggression. Prior research has demonstrated that children who engage in proactive aggression tend to feel lower levels of sympathy and are less sensitive to the emotions of others in morally relevant contexts (callous unemotional traits; Northam & Dadds, Reference Northam and Dadds2020), which contributes to their willingness to treat others as a means to an end (Peplak & Malti, Reference Peplak and Malti2017). It is possible that associations between proactive aggression and sympathy are best captured in dispositional assessments that measure sympathy across a wide variety of contexts (Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2019). Indeed, when testing links between proactive aggression and our dispositional sympathy variables (child- and parent-reported), parent-reported ratings were significantly negatively associated with both proactive and reactive aggression. Parents may be better able to recall and integrate memories of their children’s lapses in sympathy, which in turn best explains their motivations for engaging aggressively (though, this association may also reflect shared measurement and informant bias). Researchers have also argued that the association between sympathy and proactive aggression is most apparent within physiological assessments and in adolescent samples (Northam & Dadds, Reference Northam and Dadds2020); thus, future research assessing children’s sympathy and aggression should assess sympathy using multiple measures and informants across a wider range of age groups. Further, our story contexts did not showcase harm that resulted in instrumental gain to the participant; thus, it is possible that sympathy for proactively aggressive children may be especially dampened when personal gain is at stake. Finally, children showing proactive aggression tend to be more manipulative and show higher Machiavellian traits – traits that have been associated with lower parent-reported (but not child-reported) sympathy (Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante and Malti2024). Thus, perhaps children who engage in proactive aggression are more likely to tell experimenters what they want to hear rather than what they actually feel.

Implications

When moral concern is selectively applied (e.g., inhibiting sympathy toward disliked or antisocial others), children may develop justifications for aggression framed as “fair” or “deserved,” and divorce their moral emotion from moral judgment in ways that foster moral disengagement (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger & Perren, Reference Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger and Perren2022). Children who habitually suppress sympathy toward provocateurs and externalize blame for their own aggressive acts may internalize revenge-oriented justice beliefs, reinforcing reactive hostility. These tendencies contribute to a risk profile for externalizing psychopathology marked by selective concern and reduced capacity for repair (Gini et al., Reference Gini, Pozzoli and Bussey2015). Pairing sympathy for victims of harm alongside respect-driven problem-solving skills – i.e., holding a transgressor accountable for their actions in ways that reflect care for their well-being rather than revenge (Darwall, Reference Darwall2010; Malti et al., Reference Malti, Peplak and Zhang2020) – may be an effective conflict resolution tool within interventions targeting reactive aggression. These strategies may cultivate restorative rather than retributive justice behavior amongst children who show proclivities toward fighting aggression with aggression (Gönültaş et al., Reference Gönültaş, Mulvey, Irdam, Goff, Irvin, Carlson and DiStefano2020; Recchia et al., Reference Recchia, Sack and Conto2024).

Our investigation was focused on overt aggression; however, there are notable gender and age differences in the types of aggression children enact. Specifically, boys tend to engage in more overt aggression while girls engage in more indirect aggression (Björkqvist, Reference Björkqvist2018; Casper & Card, Reference Casper and Card2017), and covert (i.e., hidden) and indirect aggression tend to increase with age, peaking around late childhood (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Sameroff, Lansford, Sexton, Davis-Kean, Bates, Pettit and Dodge2013). While we did not find that gender was associated with overt proactive or reactive aggression in our sample, our aggression measures likely did not capture all forms of harmful behavior. Further exploring the role of sympathy in aggression that does not have immediate and obvious physical signs (such as covert aggression) could have important implications for targeted interventions.

Limitations and future directions

The first notable limitation of this study was that it was cross-sectional; thus, we could not speak to the direction of the relation between children’s sympathy and aggression. While we conceptualize sympathy to be an emotion that buffers children’s aggressive acts, recent research has shown that reactive aggression may predict decreases in sympathy over time (but not the reverse; Tampke et al., Reference Tampke, Fite and Cooley2020). Additional longitudinal research is needed to examine the development of sympathy across multiple contexts and aggression in larger samples.

Second, children’s self-reports of sympathy in response to picture/story indices are generally affected by social demands (i.e., the need to behave in a socially approved or expected manner; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Valiente and Eisenberg2003); thus, additional research that limits these demands is needed. We also included an emotion descriptor in the unprovoked harm context but not the provoked harm context; as such, children’s sympathetic responses may have been somewhat influenced by the presence of this descriptor, resulting in an exacerbated between-context effect. It is unclear if and how much the emotion descriptor affected our findings, and we encourage future studies to consider this possibility.

Third, although we assessed children’s reasoning following their emotional responses to harm, we did not examine their cognitive biases (e.g., hostile attribution bias, justice and rejection sensitivity). Understanding other motivational features could have provided more insight into individual differences that could have explained our effects. We also did not explore the influence of other emotions that may be present in the contexts we observed (e.g., anger) as well as their reasoning. Future research may wish to better understand anger, particularly in contexts of injustice, due to its potential for motivating both aggressive and prosocial outcomes, which may depend on how children reason about this emotion (Bringle et al., Reference Bringle, Hedgepath and Wall2018).

Fourth, we only examined two forms of victim’s harm in our stories, physical aggression and prosocial omission. Additionally, we combining children’s responses to the two stories may have limited our ability to understand meaningful harm-related differences in sympathy. In future research, it will be important to investigate children’s sympathy across a range of harm types (e.g., verbal threats, exclusion, cyberbullying) and assess whether they load onto a single latent factor.

Finally, we measured aggression using parent-reports. Because prior research has shown only moderate cross-rater correlations in aggression (e.g., Little, Brauner, et al., Reference Little, Brauner, Jones, Nock and Hawley2003), our findings should be interpreted from the lens of parental perspectives.

Conclusion

Children tend to experience less sympathy for victims who had provoked their harm compared to “innocent” others. Though there may be some socially protective reasons for doing so, selective sympathy may legitimize the safety of some over others. Selective sympathy, particularly within contexts that involve retaliation, may also come with costs to children’s social adjustment (i.e., increase their reactive aggression and future peer problems). While it is important to hold transgressors accountable for their misdeeds, withholding sympathy may sustain cycles of violence (Posada & Wainryb, Reference Posada and Wainryb2008) and ultimately challenge children’s social–emotional health (McDonald & Lochman, Reference McDonald and Lochman2012). As such, nurturing sympathy across contexts of unprovoked and provoked harm may be warranted to support children’s wellbeing and positive peer relationships.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942610114X.

Data availability

The data are not publicly available as participants did not consent to having their data shared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the children and families who participated in this research, and the research assistants at the Social–Emotional Development and Intervention Lab for their efforts in data collection and data processing.

Funding statement

This work was supported by SSHRC (J.P., Grant# 752-2016-1155; T.M., Grant# 504464) and CIHR (E.L.A., Grant# FRN-489925).

Competing interests

Authors declare none.

Pre-registration statement

The data were not preregistered as data collection was completed prior to the widespread adoption of preregistration practices.