Introduction

In the early twenty-first century, historiographical inquiry into the Cold War was extended to the study of Afro-Asian contexts. The motivation behind this expanded view was to challenge the notion of a perfectly bipolar world and place the events of those years within a broader narrative of global transformations.Footnote 1 Decolonization played a crucial role in shaping the international landscape during the Cold War, with African decolonization – often sidelined in Europe-centred scholarship – being key. Consequently, Cold War researchers engaged with Africanist historians to explore interconnected narratives, focusing especially on African socialist experiences.Footnote 2 This led to collaboration with scholars of international communism, who examined the USSR's and the socialist bloc’s influence on newly independent African states.

Cooperation between these forces extended beyond state-to-state relations, involving communist parties within non-communist Western countries. West African parties and movements engaged with Western Europe’s two major communist parties, the French Communist Party (PCF) and the Italian Communist Party (PCI). These links were rooted in the relationships that had developed between communist and anti-colonial leaders during the interwar period. Within the labour movement, such connections facilitated the exchange of ideas and political cultures, bringing communism and Pan-Africanism together. Some of these ties were formed during colonialism, between metropolitan communists and African activists, while others emerged after World War II.

Relationships between West African organizations and the PCF and PCI were fostered by the socialist camp’s growing interest in the African decolonization process of the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the rise of new political actors challenging the bipolar order. The excitement surrounding decolonization in Asia and Africa went alongside the rise of the Non-Aligned Movement, a political platform embraced by countries that openly opposed imperialism and colonialism but rejected the bipolarity of the Cold War order and sought to use their own political weight to break it. These circumstances supported productive interactions between trade unions, communist-aligned parties, and African movements and organizations. Such ties developed not only in former colonial capitals but also in key centres of communism, non-European socialism, nationalism, and non-alignment.

This article explores the intersection between African social history and European social and trade union movements, focusing in particular on the Italian labour movement within the framework of its membership in the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU). The Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro (CGIL), inspired by the PCI, opened a dialogue with African workers and participated in exchanges with other international trade union groups. The goal of the CGIL and its activists was to strengthen the labour movement by promoting anti-colonial struggles. However, within its international trade union centre, it had to contend with leaders and unions that opposed its strategy – most notably the French Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT). The debate between the French and the Italians revolved around the role of the working class. The Italians maintained that this segment should support socialist development paths adapted to local conditions (the so-called national paths to socialism); hence, engagement with Africa was particularly stimulating. The French, however, believed that the Italian proposals risked causing a split within the international labour movement.

This article demonstrates that the WFTU was not a monolithic bloc but rather comprised several divergent positions. After the fateful events of 1956 and amidst intensifying de-Stalinization, competition between the unions within the federation became increasingly pronounced. With Khrushchev’s national paths to socialism, new socialist models arose, often at odds with the USSR’s stance. In the 1960s, China became the Soviets’ main rival in the communist movement, but other parties and trade unions also turned away from Moscow’s line.Footnote 3

When discussing the WFTU, a distinction must be made between “Western” and “Eastern” trade unions. Like many other WFTU-affiliated unions – including those in the West – workers’ organizations in socialist countries were closely linked to communist parties and labour organizations. However, in Eastern Europe, these were ruling parties, and the unions themselves became instruments of the socialist organization of labour and society. The CGIL and the CGT were in tension not only with WFTU affiliates from state socialist countries but also with each other, offering differing organizational, ideological, and cultural models. The CGIL aimed to represent all Italian workers, balancing the communist majority and the socialist minority. Cold War divisions notwithstanding, the CGIL had to mediate between diverse political currents (having both socialist and communist members) and social classes (with a strong presence in northern Italian factories and a significant role in peasant struggles in the south, as shown by communist leader Giuseppe Di Vittorio’s leadership in Puglia’s farm labour protests). In contrast, the CGT, closely allied with factories, championed the French working class, merging Marxist–Leninist legacies with patriotic concepts from the Jacobin revolutionary tradition.Footnote 4

Rivalry often complicated CGT–CGIL collaboration in WFTU assemblies, especially after the election of PCI official Agostino Novella (1957) as CGIL General Secretary. Novella, aligning with Communist Party Secretary Palmiro Togliatti’s political views, sought an Italian way to socialism, a concept opposed by the PCF and Benoit Frachon’s CGT, who rejected national paths to socialism.Footnote 5

This article also examines the political and personal trajectories of key figures in the WFTU and CGIL, considering their impact on the trade union debate on decolonization, development, and socialism in Africa. African labour activists, such as Guinean Seydou Diallo and Malian Mamadou Sissoko, respectively secretaries of the Confédération Nationale des Travailleurs de Guinée (CNTG) and the Union Nationale des Travailleurs du Mali (UNTM), were crucial to these inter-union relations.

The article shows, moreover, that the debate quickly expanded to involve the national trade union centres of the socialist bloc in Eastern Europe as they sought to forge closer ties with West African unions and acquire a deeper understanding of African contexts. This research thus contributes to the new historiography of the Cold War, simultaneously directing attention to Africa’s social and political history. These themes are enriched by perspectives from the historiography of the European communist labour movement and studies on relations between the Global North and South.

The article draws on the documents preserved in the archives of the Italian CGIL and PCI (Rome); the archive of the CGT in Montreuil (Paris); and papers of the PCF and the WFTU kept in the archives of the Seine-Saint-Dénis in Bobigny (Paris).Footnote 6

The WFTU: An Internationalist Network, a Repository of Ideas

The WFTU was founded in 1945 in Paris with the participation of various anti-fascist trade unions of different political affiliations. Against the backdrop of the Cold War and US–USSR rivalry, however, the WFTU became increasingly pro-communist; its non-communist and non-socialist unions left in 1949.Footnote 7

The WFTU was a key player in bringing the international communist and labour movement closer to the decolonization struggle, anti-colonial movements, emerging African and Asian countries, and the Non-Aligned Movement. Within the WFTU, a network of solidarity was organized among workers around the world in support of the self-determination of peoples, which became a cornerstone of the labour movement’s internationalist solidarity.

On the other hand, the WFTU was not merely an instrument of mediation and internationalist solidarity – it was a repository of ideologies, leaders, and activists. As such, its members (whether individuals or organizations) both engaged in dialogue and acted independently of one another. The WFTU was often accused by the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU; established by anti-communist trade unions after 1949)Footnote 8 of espousing a monolithic vision of communism that served to promote Soviet policy.Footnote 9 In fact, the WFTU played host to a wide range of positions. Particularly from the 1960s onwards, it accommodated the conflicting stances of the Soviets and the Chinese, as well as communist trade unions from Asian countries in conversation with anti-colonial movements. It was precisely the trade union organization’s multilateral character that allowed for its ideological openness towards the changes brought about by decolonization.

The WFTU’s rapprochement with the new African trade unions – driven by strong pan-African and anti-colonial forces – was therefore achieved through the efforts of the various trade union organizations that made up the WFTU and the many activists who animated it. Among them, representatives of the CGT and the CGIL were the most eager to establish contacts with their African counterparts. They saw themselves as representatives of “capitalist” Europe’s working class, whose fundamental duty was to fight Western imperialism from within, advocating for socialism and the improvement of workers’ conditions. At the same time, the Italian and French trade unions pursued their own autonomous “national” policies, the strategic contours of which were often reflected in their international relations. In particular, the CGIL’s innovative approach to anti-colonialism and its relations with African workers’ organizations caused several disagreements with the CGT and the majority of the WFTU. The CGIL encouraged African trade unions to unite in pursuit of political and economic independence. This required engaging with both the WFTU and the ICFTU, which included not only strongly anti-communist US unions but also the British Trade Union Congress.Footnote 10 Many trade unions in Ghana, Nigeria, and Kenya, where African–American pan-Africanist organizations also had substantial influence, patterned themselves after the British trade union structure.Footnote 11 US trade unions emerged as the leading advocates of the ICFTU’s anti-colonial efforts in Africa, providing both technical and financial support to African organizations. However, their involvement was primarily intended to steer the ICFTU’s actions towards a more aggressive anti-communist position, which significantly strained relations with the WFTU.Footnote 12

The Union Générale des Travailleurs de l’Afrique Noire and West African Trade Unions

After World War II, as African trade unions increased in number and power, closer ties between communist union officials in Europe and their counterparts in colonies were forged.Footnote 13 By the late 1940s, the Cold War climate had ideologized many labour movements in French West Africa. In the early 1950s, most West African trade unions were branches of French national centres.Footnote 14 After the Bandung Conference and the rise of the Afro-Asian movement, trade unions’ need for autonomy grew. In January 1956, the Confédération Générale des Travailleurs Africains was founded to challenge Eurocentric Marxist views on the working class and direct attention to local social realities. However, it remained closely associated with the CGT and the WFTU, failing to address the autonomy and pan-Africanist demands of African anti-colonial movements.Footnote 15

In the early 1950s, the WFTU aligned itself with trade unions in socialist countries and the USSR. While the French CGT followed pro-Soviet policies, it also pursued its own national agenda. Consequently, French trade unionists’ relations with their African counterparts were shaped by the goals of achieving social justice between the metropolis and colonies and creating a large egalitarian community, not securing independence for the colonies. In response to pressure from African union leaders, the WFTU sought to solidify its bonds with African trade unions to expand support for the socialist camp, combat imperialism, and assert the communist movement’s central role in the anti-colonial struggle.Footnote 16 Starting in 1956, the socialist camp supported “national roads” to socialism, and, within the WFTU, a debate arose among European, Asian, and African members on the need to grant anti-colonial trade unions more freedom. The focus shifted from legal and wage-related demands to the anti-imperialist struggle, to be led by the “masses” of workers. The result was recognition that trade union action must adapt to the African context and that local organizations should be free from the CGT and its ideological control in their manoeuvrings.Footnote 17

In January 1957, African former CGT leaders (including Sékou Touré, future president of Guinea) launched the Union Générale des Travailleurs de l’Afrique Noire (UGTAN), an autonomous organization seeking to promote the unity of trade unions in French-speaking Africa. Its goal was independence, prompting the UGTAN to break with the CGT and disaffiliate from the WFTU, drawing inspiration from the Bandung principles. Nevertheless, the UGTAN maintained a progressive, socialist stance, evident in its role in the 1958 Guinean independence referendum. Its activities were viewed differently by certain WFTU affiliates, however.Footnote 18

Western trade unions associated with the WFTU viewed the establishment of the UGTAN as a means of countering imperialism’s fragmentation of the labour movement. CGT leaders, on the other hand, believed that strengthening the working class in African countries was essential for guiding them towards socialism. French leaders were prominent in the WFTU, with Louis Saillant, the general secretary, sharply criticizing those who thought class struggle in Africa should be overcome to build a united anti-imperialist movement.Footnote 19 For his part, Guinean labour leader and politician Sékou Touré argued that African social classes were poorly defined and not central to socialist development.Footnote 20 The divergence of views became more evident after the independence of African countries like Ghana (1957), Guinea (1958), and Mali (1960), which tried to build socialism in former colonial contexts where the working class was nearly non-existent.Footnote 21 The resulting debate centred on the function of trade unions in independent (and especially progressive) African countries, and whether class struggle was actually fundamental.

When Guinea gained independence in November 1958, French communists, leveraging their connections with Guinean trade unions, made the case that the country could achieve socialism through workers’ leadership. The CGT viewed Touré’s progressive government as tasked with fostering the rise of the proletariat and industrializing Guinea using Soviet aid. To support this, CGT and WFTU leader Maurice Gastaud was sent to Conakry to establish an African Workers’ University for the political and ideological training of African trade unionists.Footnote 22

The CGT was disappointed by the UGTAN’s decision to break away from the WFTU and adopt a neutralist, anti-colonialist stance. However, with Guinea’s independence, the union and the French party could become key mediators between anti-colonialists and the socialist camp.Footnote 23 According to CGT officials and many in the WFTU, African trade unions ought to operate as the most progressive, Marxist sectors of their respective societies, pulling their countries to the left through institutional leadership.Footnote 24

The WFTU in Africa and the Role of the CGIL

In the 1950s and 1960s, the CGIL was a national centre with a communist majority and a left-wing socialist minority, influenced by the PCI’s strategies. Beginning in 1956, Italian communists developed the “Italian way to socialism” (via italiana al socialismo), advocating for socialism through progressive reforms tailored to local conditions. At the time, Italy had a young democracy and a constitution co-written by communists but was marked by a stark social and economic divide between the north and south. Many communist leaders and intellectuals considered the south to be exploited by the capitalist north, often likening it to a colonial relationship.Footnote 25

The CGIL closely followed the trajectories of newly independent countries in West Africa, with Guinea quickly drawing its attention. From 1958 to 1959, the CGIL made contact with UGTAN trade unionists as Italian communists and socialists took a greater interest in the decolonization of West Africa.Footnote 26 Italian trade unionists established ties with Guineans, Malians, and Cameroonians through CGT leaders’ prior connections (including personal friendships) or international WFTU meetings. Many CGIL cadres were also PCI leaders, using the party’s political channels in the aforementioned African countries.Footnote 27 Compared to their French counterparts, Italian trade unionists had a different view of African workers’ role in post-colonial society: African trade unions, in their view, should not merely represent the proletariat or serve as a tool of class struggle. The CGIL believed that social classes in Guinea and other African countries, due to colonial legacies, were still largely amorphous; European domination had hindered the development of modern society and the working class. Therefore, trade unions had to organize the masses against neocolonialism to secure and buttress national independence. Union work among peasants (the majority of the workforce in newly independent West African nations) needed to be paired with the unionization of civil servants. The CGIL saw civil servants as an emerging class, taking over roles previously held by Europeans and crucial for running the state and directing its socialist development. Similarly, in post-war Italy, trade union work among public employees was vital to purging the state administration of the remnants of fascism. Italian communists believed that influencing institutions was imperative for progress towards socialism – hence, public employees needed political education.Footnote 28 The CGIL aimed to support African paths to socialism without resorting to dogmatism, which could alienate African parties and undermine the credibility of the communist international labour movement; its strategy aligned with the founding principles of the UGTAN. At the WFTU’s Fourth World Trade Union Congress in Leipzig (September 1957), it was declared that the primary task of the labour movement in Africa and colonial countries was to champion independence. African workers had to first liberate their own lands, enabling the social development long hindered by colonial rulers. This also meant regaining control over national resources and the economy. The Congress called for active collaboration with the national bourgeoisie, seen as a vital force in the liberation struggle and the formation of independent governments. Trade unions, therefore, were charged with overseeing the national bourgeoisie, holding them to an anti-imperialist course and preventing self-interested behaviour.Footnote 29

The founding of the UGTAN and Ghana’s independence (1957) prompted the WFTU to engage with pan-African movements. The UGTAN’s creation must likewise be understood in the context of the 1957 formation of the European Economic Community (EEC), which communists saw as a NATO tool controlled by the United States; some EEC members had colonial empires and sought to maintain dominance through European integration. In response, the WFTU organized a working group to assess the European Common Market’s impact on African countries. In 1959, this group focused on the European Community’s multilateral colonial strategy in sub-Saharan Africa, involving all EEC members to build a powerful imperialist network. Both African and European trade unionists participated in the discussions, among which was a June 1959 meeting in Paris with WFTU representatives and Italian trade unionists like Bruno Trentin,Footnote 30 a UGTAN delegation including Senegalese Thiaw Abdoulaye and Ba Abderhamane, Sudanese (Malian) Dia Bate, and CGT delegate Livio Mascarello. Mascarello, an Italian metalworker who had immigrated to France as a child, was tasked by the CGT with engaging in dialogue with the CGIL.Footnote 31 On this occasion, all delegates shared a negative view of the European Common Market’s role in Africa. As they saw it, the Common Market aimed to integrate African colonies into NATO’s military framework and block their economic independence by promoting monoculture and impeding industrial development. The delegates at the 1959 meeting believed that such control could allow European powers to exploit and discriminate against local workers. Consequently, the WFTU emphasized alignment with nationalist movements to fight for African countries’ independence.Footnote 32 Trentin addressed the issue because he was among those who viewed the struggles of the proletariat in the broader context of a global “neocapitalism”. For this reason, he thought that an international trade union struggle was necessary – one capable of keeping pace with the transformations of capitalism and dealing with its consequences, even in former colonial countries.Footnote 33

Criticism of the EEC was led by the CGT and CGIL, representing the WFTU, alongside UGTAN members. The PCI and PCF also opposed the European Community’s initiatives in Africa, considering them “neocolonial”. Even after the wave of independence that swept through West Africa in 1960, efforts to keep France’s former African territories within a European sphere of influence persisted. However, the perspectives of the two communist parties, as well as the CGT and CGIL, differed. The French communists, while denouncing the bilateral agreements between France and its former coloniesFootnote 34 as expressions of French imperialism, were even more hostile to the initiatives of the “Europe of Six”.Footnote 35 From their perspective, the EEC’s pursuit of economic and trade agreements with France’s former colonies sought to extend imperialist domination to NATO allies, paving the way for countries like West Germany and Italy to enter Africa.Footnote 36

For Italian communists, the formation of the European Common Market marked a turning point in redefining the geographical scope of trade union action. The creation of the EEC, perceived as a large imperialist entity, required unified action from the working class of “capitalist Europe”, which gained its own identity and significance. In the late 1950s, Italian communists endeavoured to negotiate with their French comrades and develop a joint strategy for workers across EEC countries. For the CGIL, the Treaties of Rome had established a supranational imperialist institution that needed to be challenged, with all its unique features (including its ties to France’s and Belgium’s African colonies) borne in mind. This positioned the CGIL in a different context from socialist countries, necessitating new strategies.Footnote 37

The WFTU decided to lead a trade union struggle for socialism and against what it viewed as the new European imperialism in Africa. In collaboration with French and Italian trade unionists, West African UGTAN representatives drafted a document proposing a common African market and, most importantly, a campaign of economic and military aid from socialist countries to the newly independent African states.Footnote 38

The integration of many African countries into the French Communauté rénovée in 1960, along with the first skirmishes between the Soviets and the Chinese, shifted the political balance within the WFTU. These changes led to more dogmatic views on decolonization and sparked a bitter confrontation between French, Soviet, and Italian trade unionists.

African Independence and Alternative Views on the Role of Trade Unions in Africa

The “Year of Africa” – 1960 – saw seventeen African countries gain independence in an upswell of decolonization that also impacted European workers. At WFTU meetings and conferences, however, doubts were voiced about whether some countries had achieved “true” independence. While France had granted countries political independence, it maintained control over their economies – although in Guinea’s case, independence had been won, not bestowed through the benevolence of the colonial powers.

In part because of this feature of Guinea’s road to autonomy, the WFTU prioritized promotion of the country’s socialist development. With the establishment of the African Workers’ University in Conakry in early 1960, the country was set to become a centre for training cadres to lead Africa into the socialist camp. The CGT was instrumental in this initiative.Footnote 39 Gastaud, the director of the African Workers’ University, was a member of the PCF and among the most ardent proponents of the need to create a robust working class in Africa.Footnote 40

Italian trade unionists, on the other hand, disputed this ideological approach. They argued that the struggle for total independence was not over and that the unification of the masses was still required. In their eyes, colonial society had not yet been overthrown, and class divisions were not yet relevant.Footnote 41

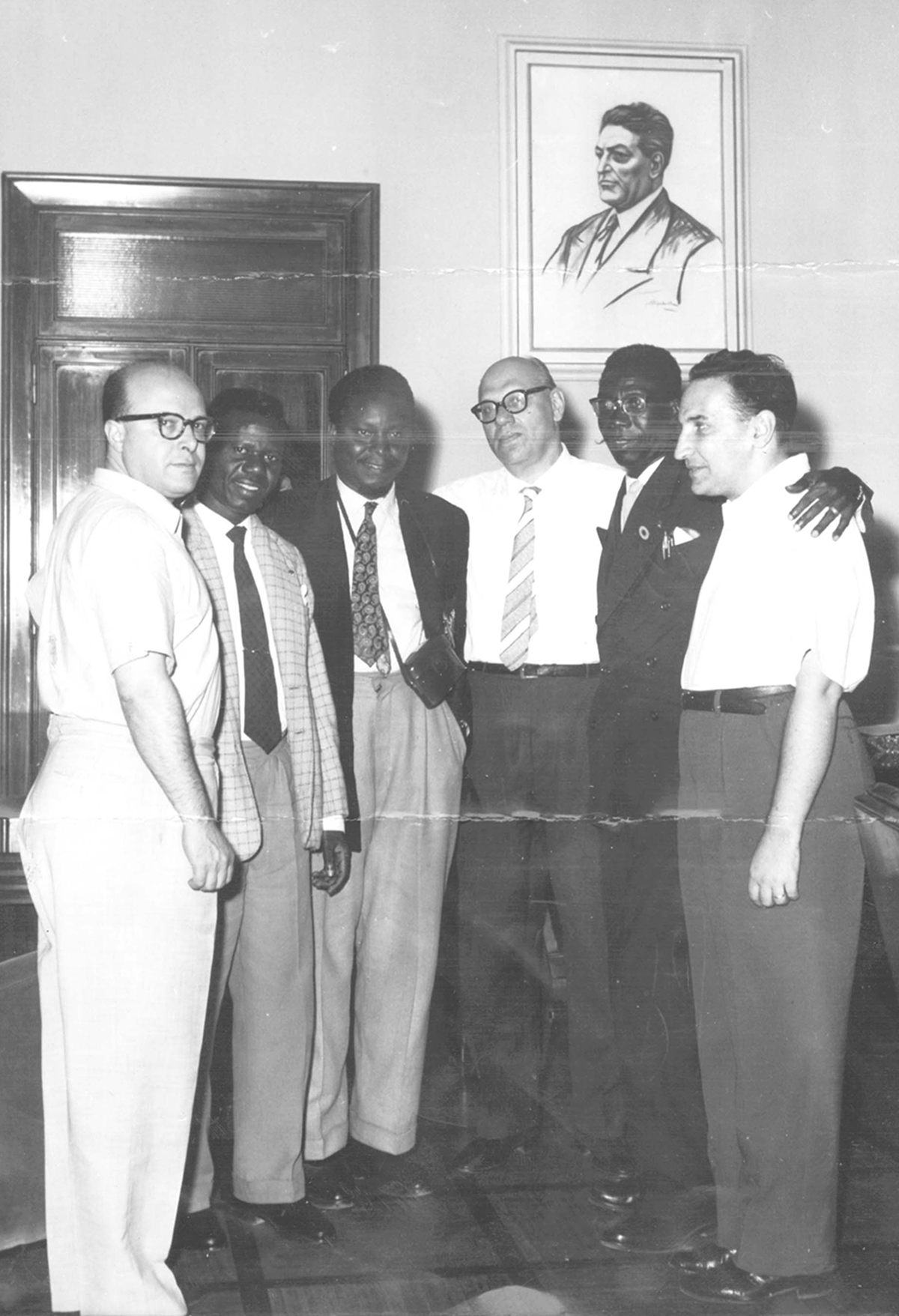

Meanwhile, the CGIL strengthened its ties with the Trade Union Congress (TUC) of Ghana (see Figure 1) and the Guinean CNTG, sometimes via the WFTU. In August 1960, Mario Giovannini, a communist trade unionist from Bologna, travelled to Guinea and Senegal to initiate contacts with local unions, accompanied by fellow trade unionist Pino Tagliazucchi.Footnote 42 Giovannini led the National Federation of Local Government Employees, part of the CGIL, while Tagliazucchi, a member of the Socialist Party of the United Proletariat (Partito socialista di unità proletaria, a small party allied with the PCI and headed by Italian anti-colonialists Lelio Basso and Lucio Luzzatto), was focused on the anti-colonial struggle.Footnote 43 Tagliazucchi, who joined the Partito di unità proletaria per il comunismo in the 1970s, would have been in communication with the Italian New Left movements. Already at that time, Tagliazucchi, like Trentin, was convinced that global action by the labour movement was required to prevent a new form of network capitalism from exploiting the opportunities appearing in former colonial countries.Footnote 44 Additionally, both realized that European formulations of the working class’s role did not apply in Africa.

Figure 1. Pino Tagliazucchi (first from the left), Agostino Novella (third from the right), and Silvano Levrero (first from the right) meet a TUC delegation in Rome, 1960.

During the same trip, Giovannini and Tagliazucchi also visited Mali, which had just gained independence. There, President Modibo Keita had drawn on pan-Africanist and socialist ideas to build the new Malian state. The Italian delegation met key leaders of the CNTG in Guinea and the UNTM in Mali, including secretaries Seydou Diallo (who had already been to Italy, attending the CGIL National Congress in Milan in April 1960 – see Figure 2 – and succeeded Touré as head of UGTAN)Footnote 45 and Mamadou Sissoko.Footnote 46 Both were members of the ruling parties – the Democratic Party of Guinea and the Sudanese Union – and had received trade union training from the CGT, where they had developed as activists and leaders. Bonds between the CGIL and the Guinean and Malian unions solidified, particularly through Italian involvement in agriculture and the public sector. Touré’s theories on overcoming class struggle and promoting mass participation in structural reforms led the CGIL to support Guineans and Malians publicly within the WFTU, sparking criticism of the CGT from the Italians, who believed that the French misunderstood African realities.

Figure 2. Seydou Diallo listens to simultaneous translation during the Fifth CGIL Congress in Milan, April 1960.

The necessity of supporting African political/economic independence (and the autonomy of African trade unions) became a major debate within the WFTU and among its national affiliates, as my research shows. WFTU General Secretary Louis Saillant opposed the Italian stance on polycentrism and structural reforms. Saillant, a member of the Section française de l’internationale ouvrière until his 1948 expulsion for pro-communist views, was known for his fervent orthodoxy and pro-Soviet leadership. He rejected the idea that local specificities should shape the development of socialism, aligning closely with the French communists on this matter. He had previously worked with Pierre Semard, a PCF official, and was influenced by the party’s positions.Footnote 47 Saillant and the French communists saw the French path to socialism as involving a stronger focus on national issues but disputed the need to adapt Marxist categories to French society. They adhered to the Soviet model in both theory and state organization, aiming to make France a socialist country. This, they contended, would give rise to a just, egalitarian, and cosmopolitan society between France and the African countries. However, after the 1958 constitutional referendum, de Gaulle made this model unfeasible, and the PCF openly supported Guinean independence. The French communists still believed it was possible to maintain cultural and ideological ties with militants from former colonies and sought to build a proletarian vanguard in the trade unions and ruling parties of Guinea and Mali. If Saillant and the CGT held significant sway within the WFTU, the CGIL was also influential, representing Togliatti’s ideas on national paths to socialism and “structural reforms”. From this perspective, socialism had to be advanced gradually in some parts of the world, transforming society’s structure via existing institutions. This, the logic went, was the approach needed for countries emerging from colonialism in general and in Africa specifically (where the working class remained largely marginal because the continent’s economies were not yet sufficiently independent to support the development of a “modern” society). Using the concept of “neocolonialism”, the communists considered such countries to still be dependent on European powers, which actively hampered the growth of an industrial sector. They posited that the former colonizers’ objective may have been to maintain control over African economies, hinder autonomous development, and prevent the emergence of a conscious working class. This interpretation led to friction within the WFTU, as the CGT, according to the Italians, sought to push African unions into dogmatic positions to isolate the CGIL.Footnote 48 Meanwhile, leaders of some African unions, such as the Union des Travailleurs du Mali, publicly praised the Chinese model. Guinean and Malian leaders saw Chinese unions as the vanguard of workers and thought that emulating them would be essential for building an independent state. Footnote 49 Both French and Soviet labour leaders viewed African trade unions as the proletariat’s means of achieving socialism. For the Italians, however, the main responsibility of African trade unions was to fight for full independence – the class struggle was to be sidelined. This disagreement points to the significant differences in ideological approaches among WFTU affiliates like the CGT and CGIL, especially with respect to the emphasis placed on the rural peasantry versus the industrial proletariat in nascent West African cities.

The situation became more complicated after tensions arose between the USSR and China in 1960. The Maoist ideology seemed poised to divide anti-colonial movements and the socialist camp, creating a rift between industrialized and former colonial countries.Footnote 50 The socialist camp began to feel that countering Chinese influence required independent Africa to combat the post-decolonization corruption and power of the bourgeoisie by embracing a more sharply socialist approach, with choices led by the proletariat. During preparations for the Fifth WFTU World Congress in March 1961, CGIL Deputy Secretary Luciano Lama noted the WFTU leadership’s mistrust of African trade unions. Lama, secretary of the Italian Metalworkers’ Federation and a PCI official, believed that the union had to engage the masses to transform society and that the working class needed to collaborate with peasants and employees.Footnote 51 In his opinion, the time was not yet right to push for class struggle in Africa, a point he emphasized to the WFTU audience.

The preparations for the Fifth Congress were held in Beijing, and Chinese trade unionists sought to dominate the meeting. This provoked efforts to discredit them – the WFTU majority stressed the role of the workers’ vanguard in former colonial countries, challenging Chinese peasant revolutionary theories. According to Lama’s note to the CGIL, the WFTU

[…] doesn’t understand the crisis in which a trade union movement objectively finds itself, [a trade union movement] that has rightly collaborated for years with the bourgeoisie in a clandestine or armed struggle, after the liberation.Footnote 52

That is, emancipation did not imply the end of the anti-imperialist struggle or the demand for economic aid, as only modernization and development could “make the achievement of independence definitive”. Lama argued that the WFTU leadership’s distrust of African trade unions and their focus on the “African personality” could undermine “the contacts formed during the height of the independence struggle”. While the CGIL supported a united effort by West African trade unionists, the CGT and the majority of the WFTU’s leadership voiced dissent, deeming it an imperialist strategy to thwart class struggle. As a result, the CGIL proposed an amendment to the preparatory document for the Fifth World Congress. Lama urged Louis Saillant to “base demands and union policies on the reality of each country”. However, Saillant replied that “the working class is one, and its unity is grounded in unified demands (not interests!)”. He likewise warned that Lama’s position was dangerous, as it could strengthen factional (Chinese) views.Footnote 53 The Italian proposal was rejected, eliciting a forceful response from CGIL General Secretary Agostino Novella, who expressed his disagreement in a letter to Saillant.Footnote 54 In April 1961, the CGIL denounced the WFTU’s report on the international trade union situation. Pino Tagliazucchi critiqued the WFTU’s “paternalism”, schematism, and misreading of the African situation. The Italians argued that the WFTU failed to recognize African workers’ primary need: to take ownership of their resources and free themselves from neocolonial exploitation.

The Casablanca Congress and the Birth of the All-African Trade Union Federation

To reach basic economic and social benchmarks, an ongoing alliance between the nascent bourgeoisie and the proletariat was required in newly independent countries. Thus, the CGIL leaders asserted, the WFTU and its national affiliates should have pursued power alongside the respective parties and shored up their political identity. However, the issue of trade union autonomy from political power remained important.Footnote 55 In May 1961, the creation of the All-African Trade Union Federation (AATUF) showed, according to the CGIL, that only the “Pan-Africanist ideological orientation” could ensure genuine autonomy and overcome schematism, sectarianism, and colonial ideological subordination. The CGIL closely monitored the AATUF after its founding and was alert to its unique aspects – the AATUF aimed to bridge divisions in African trade unionism (among other ways, by striking a compromise between socialist and religious groups) to avoid Cold War political rifts. In fact, this new organization was meant to include trade unions cooperating with the WFTU, such as those in Guinea and Mali, as well as unions earlier affiliated with the ICFTU. The CGIL’s international office sent Tagliazucchi to Casablanca to attend the founding congress, where the CGIL and CGT were the only unions from capitalist countries present. Despite hopes for unity and autonomy, Tagliazucchi noted the paradox in King Hassan II of Morocco’s opening speech, which proposed that the subordination of the union to the state was the only way to synthesize workers’ aspirations. Conditions for autonomy were shrinking, despite leaders like Sissoko and Seydou Diallo advocating non-alignment, pan-Africanism, the fight against “feudalism”, and dissociation from other international centres.Footnote 56

The Casablanca Charter called for trade union autonomy from global trade union federations and superpowers, insisting on the latter’s noninterference in African affairs. This position extended to core principles: the AATUF declared its African identity and freedom from external ideologies, highlighting the gap between industrialized countries and new post-colonial states, whose primary goal was full independence. The organization identified itself with the Non-Aligned Movement and challenged the bipolar world order; its condemnation of imperialism and references to socialist solutions made it a natural partner for the WFTU, which maintained ties with several African leaders. However, the AATUF faced internal tensions between those advocating constructive dialogue with pan-African realities and those rejecting socialist solutions beyond Marxist–Leninist dogma. The CGIL defended the need to respect both the political and ideological autonomy of African trade unions, which operated under different conditions from those in Europe. Their stance was opposed by the CGT and unions of the socialist camp. In 1961, Gastaud argued that African trade unions had initially fought against “indigenous capitalism”; he viewed African liberation movements as comprising the working class, peasantry, and national bourgeoisie.Footnote 57 The CGIL took issue with this classist view of colonial and post-colonial society, believing that the subaltern condition of Africa’s entire population required unity across all sectors to resist colonialism and neocolonial economic control. The Italians’ position on trade union autonomy and an African path to socialism strengthened their bonds with the AATUF.Footnote 58

At the Casablanca conference, Tagliazucchi observed that the matter of trade union autonomy was still unresolved. Unions siding with the WFTU were most in favour of breaking from international organizations to create an autonomous pan-African platform. Tagliazucchi maintained that disaffiliation, supported by Guineans Seydou Diallo and Mamady Kaba and Malian Mamadou Sissoko, would fortify the anti-imperialist alliance with the European labour movement. However, autonomy could not be achieved without addressing independence from state institutions. The relationship between unions and the state was pivotal for unions in both neocolonial countries and in Ghana, as well as for the former UGTAN,Footnote 59 demonstrated by the control that the Guinean and Malian governments exercised over the unions.

Tagliazucchi and Rosso also took the occasion to praise Mamadou Sissoko for the role of the union in Mali and the AATUF in the fight against neocolonialism. The relationships between Italian and Malian trade unionists were likewise maintained by Silvano Levrero, a Neapolitan trade unionist who had served as head of the chamber of labour in his city and later led the international department of the CGIL.Footnote 60 As Levrero wrote to Sissoko a month later, the primary task of African trade unions was still to secure full emancipation. Independence had not solved everything, and class struggle had to await the appearance of a conscious working class, obstructed up to that point by the economic dominance of foreign capital.Footnote 61

Levrero sent Sissoko a draft of a joint declaration he had written with Dioko and Camara, two Malian delegates who had visited Rome some months earlier. The statement affirmed that the fight against neocolonialism in Africa also aimed to weaken European monopolies, just as the European working class’s struggle against big business supported African goals.Footnote 62

The statement highlights another ideological divergence between CGIL and CGT. While it acknowledged socialist countries’ support for the struggle of Africans and the working masses in capitalist countries, the CGT could not accept it. The French believed that the French working class could most meaningfully aid peoples under French imperialism, yet they rejected the idea of an autonomous identity for workers in capitalist countries.Footnote 63 This provided the Italians with the chance to differentiate themselves from the majority view of the socialist camp within the WFTU. Saillant argued that the CGIL’s position risked fragmenting the working class and that tailoring strategies to local interests would open the door to opportunism and expose them to Chinese factionalism. The Italians, on the other hand, believed Saillant’s approach could push African unions away from the WFTU. Umberto Scalia, an Italian communist leader on a mission in Paris since 1956, claimed that Saillant intended to replace the Italian leaders of the WFTU with French ones in an attempt to isolate the CGIL and Togliatti’s PCI theories on national roads to socialism.Footnote 64

The “universalist” views expressed by the CGIL irritated Saillant and the WFTU leadership, and not only because of the role played by the Chinese. The withdrawal of African trade unions from international trade union centres implied the presence of organizations affiliated with the ICFTU, thereby weakening ties with the WFTU. In reality, the ICFTU – which had a sizeable membership in Africa – was far more concerned than the WFTU about the emergence of the AATUF.Footnote 65 Tagliazucchi, like Lama and other CGIL leaders, hoped that the Casablanca Congress and the formation of the AATUF would finally give rise to a truly unified trade union organization at the continental level, with the aim of defeating colonialism. However, during the March 1961 meeting of the WFTU Commission for the preparation of the Fifth World Congress, Lama witnessed a marked distrust towards African trade unions – the WFTU’s leadership seemed to regard the repeated allusions to a distinct “African personality” with suspicion, seeing them as the result of imperialist manoeuvring. These misgivings ultimately led African trade unions to distance themselves, even though many had previously been closer to the ICFTU and had participated in the Casablanca conference as observers. In essence, the shift allowed anti-communist American trade unions to make inroads in Africa.Footnote 66 Rivalry within the WFTU was intensified by interactions with African trade unions. The CGIL believed it understood the struggle of African workers better than other socialist trade unionists, and it established Italy as a node in the transit networks between Africa and the worldwide socialist camp. Trade unionists facing repression in countries such as Congo or Cameroon could reach Moscow, Prague, or Berlin with the help of the Italians, who granted them visas to enter Rome. Once in Rome, African activists sought the necessary documents from the embassies of their destination countries. As a result, many Congolese and Cameroonian trade unionists stayed in Rome for extended periods, forging close ties with the CGIL. Among the Congolese trade unionists who most frequently travelled to Rome was Valentin Muthombo, leader of the Union Nationale des Travailleurs Congolais, inspired by Lumumba’s pan-Africanist ideology. He had expressed a desire to make the Italian capital the “hub” for his own travels – and those of his comrades – to Eastern Europe. From Italy, it was easier to access countries beyond the Iron Curtain: not only was the largest communist party in Western Europe (and its networks) based there, which facilitated travel, but Italian authorities had also “normalized” diplomatic relations with the USSR following President Giovanni Gronchi’s visit to Moscow in February 1960. The stopover in Italy allowed Congolese trade unionists to make multiple visits to the USSR, Berlin, Prague, Warsaw, Beijing, and Tirana. Moreover, thanks to study visas, delegations of Congolese trade unionists were hosted by the CGIL trade union training school in Ariccia (near Rome) and attended courses at the University for Foreigners in Perugia, funded by the Italian trade union. Footnote 67

Italian trade unionists fortified their bonds with Malians and Guineans through several delegation exchanges. These trips were crucial for trade union and political education: Italians gained firsthand experience of Africa, while African trade unionists became familiar with Italian workers’ struggle. Congolese, Cameroonians, Guineans, and Malians received trade union training in socialist countries, but their sojourns in Italy acquainted them with communist local administration and agricultural cooperation in Emilia Romagna and Tuscany.Footnote 68

These facts notwithstanding, the French considered themselves to be the main link between Africans and socialist countries. French trade unionists ran the African Workers’ University, and the WFTU used the CGT to build connections with and defend African trade unionists under repression. French communist lawyer and trade unionist Robert Cevaer, for example, travelled to Brazzaville to defend union activists from the Confédération Générale Africaine du Travail arrested by the government. Many activists, including Aimé Matsika and Julien Boukambou, were former students at the African Workers’ University in Conakry. Congolese trade unionists were frequently allowed to travel to France to make contacts with the CGT and the WFTU.Footnote 69 The Congolese trade union played a key role in the Trois Glorieuses uprising in Congo-Brazzaville, a revolt headed by workers’ organizations and students that ousted Abbot Fulbert Youlou’s government and ushered in a socialist phase.Footnote 70

The French perspective (namely, that socialism could not be established except by workers and via class struggle) was gradually adopted by many national trade union centres, particularly in socialist countries. The events of 1961–1962 heralded a shift in communists’ views on Africa: Lumumba’s death and the tensions between the Soviets and Guineans in late 1961 seemed to signal that neocolonialism was pushing back. Italian communists lamented the short-sightedness of international communism and blamed the French for the conflicts between communists and nationalists in Africa.Footnote 71 In October 1961, the Twenty-Second Congress of the CPSU rolled back many national roads to socialism. Between November 1961 and January 1962, Sékou Touré’s Guinea distanced itself from the USSR, which had become too restrictive for the president’s political and economic decision making. The Soviets were accused of plotting against Touré by supporting the teachers’ union and student protests in Guinea. The November 1961 protests were violently suppressed, and relations between the government and unions became increasingly strained, with many CNTG leaders co-opted. Touré rejected class divisions in African societies, and the trade union training provided by the WFTU to UGTAN and CNTG leaders became contentious. The Guinean and Malian governments then tightened their grip on the unions, purging them of their pro-Soviet wings.Footnote 72 The CGT became convinced that Sékou Touré’s departure from Moscow was a ploy to get closer to France and the West.Footnote 73 The CGIL continued to support Sékou Touré, seeing his mass policy as the only path to socialism in Guinea and Africa (that is, a strategy that was adapted to the local context). In December 1961, at the Fifth World Trade Union Congress of the WFTU in Moscow, Luciano Lama reiterated his concerns. The CGIL delegation agreed to ratify the general resolution with some amendments, but Lama expressed dissatisfaction with its stance on the AATUF. He felt the resolution’s assessment of the struggle against colonialism and the first true experience of Pan-African trade union unity was inadequate.Footnote 74 At the same time, CGIL secretary Novella and PCI vice-secretary Luigi Longo sent a report to Togliatti voicing disappointment with the Moscow decisions. They found the WFTU document insufficient in its analysis of workers’ movement in capitalist, colonial, and ex-colonial countries. Longo and Novella argued that “huge masses of workers in Western Europe, Africa, and other continents are still outside the communist orientations”.Footnote 75 They believed that trade unions in socialist countries and the CGT failed to recognize the crucial role of African unions in building progressive states. Defending “class independence” did not mean opposing the policies of nationalist governments. Instead, the unions should support “the construction of a national and popular democratic policy […] opposed to nationalist degeneration and neocolonialist manoeuvres”.Footnote 76 Here too, the issue was directly related to trade union cohesion and the possibility of weakening the ICFTU’s influence. In their view, the WFTU’s stubborn refusal to place trust in the AATUF amounted to a concession to the ICFTU, as the unions aligned with that organization would only break away if they were able to form a truly Pan-African confederation.Footnote 77 This was indeed the case with the Ghanaian trade union, which not only withdrew from the ICFTU but also played a leading part in the creation of the AATUF.Footnote 78 However, the decisions taken by the trade union conference represented a new interpretation of the African situation and disagreements within the WFTU intensified. The interclass massification of society was unacceptable from the French point of view, even in Africa.Footnote 79

The concerns of CGIL leaders were confirmed in January 1962, when many African trade unions affiliated with the ICFTU established the African Trade Union Confederation in Dakar. In opposition to the AATUF and the WFTU, they aligned themselves with a global network of “free” trade unions providing technical, educational, and organizational support.Footnote 80

A New World Phase, a New Stage in the African Struggle

In the mid-1960s, world events shifted the communists’ thinking on ex-colonial countries. The Vietnam War suggested that imperialism was escalating its violence to reclaim lost ground. Togliatti’s death triggered further disagreements between the PCI and CPSU, as his posthumous political testimony criticized the USSR’s approach to liberation movements.Footnote 81 At the time, Soviet cooperation with African countries was significantly reduced; new leader Leonid Brezhnev sought to restore the USSR’s central role in the communist movement. The Kremlin would only support movements that adhered to its ideological and strategic model. From the communists’ perspective, this heightened the visibility of corruption and failures in progressive African states.Footnote 82

The CGIL believed it was time for progressive states to embrace socialism. African trade unions, they contended, should focus on transforming society, eliminating the remnants of colonialism, and pushing for genuine structural change. However, the Italians remained confident that they could represent all communists through dialogue with anti-colonial movements. They persisted in engaging with Afro-Asian movements, endeavouring to promote a socialism rooted in popular commitment. For the Italians, this was the only way to advance from the feudal/colonial phase, where the working class barely existed, to the socialist phase.Footnote 83

In this context, the CGIL’s relations with Africans grew stronger, the former aiming to be a model of efficiency and political awareness through mass struggle. However, Italian trade unionists came to realize that their African counterparts were reluctant to commit to building socialism. In 1964, when John Tettegah, general secretary of the Ghanaian TUC, replaced Morocco’s Majhoub Ben Seddik as head of the AATUF, Silvano Levrero engaged him in an intensive exchange of correspondence, extending an invitation to Italy to represent the pan-African federation. Between 1963 and 1964, both Giovannini and Antonio Lettieri visited Ghana to meet Tettegah, but relations were marred by misunderstandings. Lettieri came from a working-class background, and his perspective was informed by his education and leftist beliefs. He headed CGIL’s international department and was a member of the PSIUP, later following Trentin into the metalworkers’ federation. He also helped found Democrazia Proletaria (1975), a small left-wing party. Lettieri’s visit to Ghana was ultimately a failure because “there was nothing to be done with the Gold Coasters”Footnote 84 – they were too far from socialist ideas. The training of TUC leaders followed a trade union tradition closer to the Anglo-Saxon (and ICFTU) model than to those of the French or Italian confederations, provoking misunderstandings with both the CGIL and the French-speaking members of the AATUF.Footnote 85 Lettieri therefore decided to go to Conakry and Bamako, accompanied by Mamady Kaba, leader of the CNTG, and Sissoko, president of the UNTM, with whom he shared political and likely linguistic affinities (CGIL leaders were fluent in French but less proficient in English).Footnote 86 The experience of unity, however, did not seem to support the socialist transformation of African states; rather, it appeared to impede it.

At the same time, the French grew increasingly convinced of the inadequacy of the Italian approach to national roads to socialism. International events had shown that only a decisive socialist shift in African countries could effectively resist “imperialist aggression”. CGT trade unionists believed the working class was the key to this change, leading to miscommunications with Guinean trade unions and Sékou Touré in the following years. At the Third Congress of the CNTG (in 1963), Touré stated that in Guinea, it was the party – not the working class – that steered structural transformation: only the Democratic Party of Guinea represented the people and could guide them towards revolutionary goals.Footnote 87 A year later, the Guinean leader reiterated his opinion to Gastaud, explaining that the main cause of social tension in Africa was not its class divisions, but generational ones. According to Touré, the unity of the people was Guinea’s greatest achievement. When Gastaud pointed out that class divisions existed in Guinea, even within the party, Touré acknowledged this but argued that class struggle in Africa was mainly expressed through opposition to imperialism. While it was necessary to combat parasitic classes, the main enemy was imperialism, which included the bourgeoisie. Thus, the priority was to prevent reactionary forces from using the national bourgeoisie for their own ends. The bourgeoisie had to be drawn into the mass struggle.Footnote 88

Despite their references to scientific socialism, French trade unionists had to confront African realities. In Mali, reconciling class struggle with the existing societal structure was challenging. Gilbert Julis, leader of the railway workers’ union and a CGT and WFTU member, worked in Mali from 1962 to 1965. He was sent to Bamako by the WFTU to organize courses for a school of the Union des Travailleurs du Mali’s trade union leaders. In 1965, he noted the difficulties of aligning trade union training with Marxism–Leninism and integrating it into the local context. Julis maintained that applying the same methods and concepts to all countries was impossible, especially in Mali, where society was both complex and distinct from the European model. The Malian trade union upheld scientific socialism, but it had to deal with a ruling party that included anti-communist nationalists. Additionally, Mali was an agricultural country with small landowners living on subsistence farming, lacking large plantations.Footnote 89 At this stage – the mid-1960s – Julis’s assessment seems to have coincided with that of the Italians. After 1964, it was thought that Africa had to go one step further to achieve scientific socialism, an opinion likewise espoused by members of the CGIL. The phase of national unity was giving way to one where class struggle would be necessary, but to succeed, African workers would have to apply Marxist categories that corresponded to their local realities.Footnote 90

In any case, the CGT hoped to show that the unions of Mali and Guinea were direct heirs to the French trade union tradition. This opinion was articulated in 1963 by Marcel Dufriche, a trade unionist and member of the central committee of the PCF who had worked on behalf of the union with immigrant workers in France.Footnote 91 After visiting Mali with CGT secretary René Duhamel, Dufriche issued a statement asserting that the UNTM was modelled after the CGT, inheriting both its structure and strategies. While conceding that Mali presented different social conditions, he described the Malian union as a vanguard of the working class, shaped by its political pedigree. Dufriche aimed to reaffirm the French communists’ leadership in dealings with former African colonies, demonstrating strength to those who thought they could dominate African trade unions – namely, the CGIL, as well as the Yugoslavs and Chinese.

The Italians, meanwhile, advocated for a unified trade union platform that would include Afro-Asian organizations, aligning with the PCI’s “unity in diversity” strategy. The goal was to attract as many anti-imperialist groups as possible and bring them closer to the WFTU. Milanese communist trade unionist Aldo BonacciniFootnote 92 spoke at the anti-monopoly plenary conference organized by the WFTU in Leipzig at the end of 1964. He expressed his satisfaction with the presence of African trade unionists and praised the event’s spirit of unity. The non-affiliated African unions were free from pre-ordained decisions, allowing the conference attendees to discuss the “link […] between the anti-monopoly struggle of the working class in the industrialized countries and the liberation struggle in the underdeveloped countries”. Bonaccini observed that the conference’s ethos of unity brought together anti-imperialist forces beyond the working class. This strategy had recently mobilized Italian workers to protest the visit of Congolese Prime Minister Moïse Tshombe, highlighting the connection between African liberation struggles and those of Italian workers: both were fighting the exploitative monopolies that sought to control Africa’s resources. Bonaccini believed the recent Yaoundé agreements between the EEC and some African states to be part of this neocolonial strategy. He stated that the solution was to offer Africa a form of cooperation that was not only equal and reciprocal but clearly in its favour.Footnote 93 Bonaccini, like Trentin and Lettieri, came from the Federazione italiana operai metalmeccanici (FIOM) and thus from a factory-based background. However, by his own admission, he considered workerism “a flaw to be corrected” and preferred a broader conceptualization of workers’ struggles.Footnote 94

As such exchanges show, the Italians felt the time was ripe to include organizations from anti-colonial countries in international communist meetings and were convinced they could win the support of other members. In their view, this was the only way to push African movements decisively towards socialism. The CGIL emphasized the important part that workers in “capitalist countries” could play to strengthen communist and anti-imperialist movements. Gaining support from African trade unions was crucial to underscoring the significance of struggles in Western Europe and recognizing another driving force for socialism, in alignment with Togliatti’s idea of polycentrism.

In the mid-1960s, the Italians held considerable influence over the WFTU’s agricultural section. Its secretary was Vincenzo Galetti, an Italian communist who had visited Mali in 1961 to reinforce ties with the UNTM. Under his guidance, in 1966 the section produced a document outlining the tasks of agricultural and forestry unions, affirming the role of agricultural workers in capitalist countries and their solidarity with African liberation struggles.Footnote 95

By 1967, the views of the CGIL and PCI had been completely sidelined. The concept of polycentric socialism entered a crisis between 1966 and 1967, following the Eleventh PCI Congress and the Twenty-Third CPSU Congress. Brezhnev’s proposal for renewed Soviet centralism rejected differences in programmatic approach – hence, Italian communists reconsidered polycentrism, partly to reconcile with Moscow and heal past rifts. Their attempts to engage with the Non-Aligned Movement were blocked, however, by the 1967 Conference of Communist Parties on European Security in Karlovy Vary, Czechoslovakia. There, the CPSU condemned factionalism and prevented non-Marxist–Leninist “progressive forces” from joining communist discussions.Footnote 96 Moreover, in 1966, Ghana’s progressive president Kwame Nkrumah was overthrown in a coup, and in China, the Cultural Revolution disrupted and replaced political and trade union leadership. These events deeply impacted the CGIL. Italian trade unionists felt more than ever that African states needed to embrace socialism, and that African socialism(s) ought to fortify economic and political structures against imperialism and Chinese factionalism. Once the necessary social conditions were met, African socialisms could then be unified under scientific socialism. While admitting the possibility of building socialism according to the specific conditions of each population, for the Italian communists there was only one socialism: scientific. There could be no different types, only different paths to achieving it. Therefore, the struggle for social progress had to intensify by addressing the growing “social and political contradictions” in liberated countries and opposing the reactionary tendencies of the new African bourgeoisie, a tool of neocolonialism.Footnote 97

Conclusion

Italian communist trade unionists proved pivotal in establishing relations between African trade unions and the WFTU. Internal rivalries within the international labour movement – particularly involving the French and trade unions from socialist countries – centred on the role of workers in both Europe and post-colonial nations. These tensions affected how WFTU affiliates perceived the broader role of the socialist camp in promoting peace, social justice, and development. The French, on the one hand, emphasized the centrality of the USSR and the unique political, ideological, and cultural model it provided for African countries. They envisioned a Franco-African egalitarian unity, achievable only through the success of communists and socialists. CGT leaders expected African workers to follow the example of their French counterparts, forming a socialist vanguard for their nations. In their view, unions in countries like Guinea and Mali should lead the working class and shepherd their new states towards revolution. The French, therefore, overlooked the distinctive characteristics of the African labour movement – just as they disregarded the particularities of the working class in Western Europe – at least until the 1970s. For the CGT, “scientific” socialism was the way forward, irrespective of local context.

This emphatic promotion of a universally applicable form of socialism was necessary to prevent losing ground to the Italian communists and their union, the CGIL. The Italians believed that respecting the local population’s needs was crucial to building a socialist society and that this was the sole means of extending socialism beyond the Eastern bloc. However, their isolation in the international communist and workers’ movements led them to seek mediation with the Soviets and the French. In the late 1960s, the CGIL and PCI attributed the failures of African socialism to Soviet mistakes and the corruption of new African ruling classes. This interpretation brought them to the conviction that class struggle should be applied in countries that had fully accepted nationalist progressivism. In 1968, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia put distance between Italian communists and the USSR, prompting the former to seek a different, more democratic Western communism. This would change their approach to Africa, redirecting their focus from strengthening the socialist camp to building ties with non-aligned countries, thus weakening imperialism and challenging the Cold War’s bipolar balance.Footnote 98 After the Prague Spring repression, the CGIL, CGT, and the WFTU (based in Prague) condemned the crackdown, but Soviet trade unions forced a “normalization” within the World Federation. With the rapprochement of the PCI to the Christian Democrats – in an anti-fascist function – after 1973, the CGIL also moved closer to the Catholic (CISL) and social democratic (UIL) unions, aiming for new national unity. The PCI’s attempt to create a “Eurocommunist” bloc gained support from the PCF and CGT, but the French union stayed aligned with the WFTU until the 1990s. In contrast, the CGIL shifted towards a new European trade union body, the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), leaving the WFTU in 1978.Footnote 99

The research presented here shows how decolonization influenced the internal decisions of the international communist labour movement. The ideological positions taken towards West African unions reveal important differences between the French and Italian unions. But they also illustrate how the events of the Cold War impacted relations between the WFTU and African trade unions, stifling dialogue between communists and African socialist governments. More broadly, tensions within the WFTU weakened its international network and the circulation of militants and ideologies. It should be noted, however, that the Italian trade unionists most active in Africa almost always came from the left wing of the CGIL. With their politics shaped by working-class positions and career paths, these militants eventually entered into conversation with the movements of the new Italian Left. Starting from Togliatti’s (and Novella’s) idea of national paths to socialism and seeking to widen the anti-imperialist base and foster anti-colonial unity, the protagonists of this story came to rethink their analysis of capitalism and labour relations on a global scale. Allowing exploitation to persist in its neocolonial form, they believed, would ultimately mean the defeat of the entire labour movement.

Acknowledgements

This article was preceded by a speech at the European Social Science History Conference in Gothenburg (12–15 April 2023). I would like to thank the editors of this Special Issue, Magaly Rodríguez García, Immanuel Harisch, and Johanna Wolf. Thanks to Françoise Blum for her advice. Special thanks to the Gramsci Foundation, the Archives départementales de la Séine-Saint Dénis, the Institut d’histoire sociale, and the CGIL Archives. I would like to thank the CGIL Archives for allowing me to publish some of their images.