1. Introduction

As a promising solution for high-efficiency and renewable energy storage, phase-change materials (PCMs) have attracted considerable attention in recent decades (Ghasemi, Tasnim & Mahmud Reference Ghasemi, Tasnim and Mahmud2022). In thermal energy storage (TES) systems, PCMs are utilised to store and release heat by solid–liquid-phase transitions. Due to their high latent heat of fusion, PCMs exhibit substantial thermal storage density and are ideally suited for various TES applications, including building energy conservation, electronics cooling, solar energy systems and textile thermal regulation (Lin et al. Reference Lin, Wang, Ma, Wang and Zhang2018; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Zhu, Lin and Fang2019). Among the available options, paraffin-based PCMs (e.g. n-octadecane) are particularly popular owing to their commercial availability, appropriate melting temperature range and reliable phase-change behaviour (Abdeali & Bahramian Reference Abdeali and Bahramian2022). In addition, spherical encapsulation techniques are commonly used to enclose paraffin-based PCMs within protective shells, thereby mitigating leakage, enhancing stability and improving heat transfer during phase change (Bilir & İlken Reference Bilir and İlken2005; Jurkowska & Szczygiel Reference Jurkowska and Szczygiel2016). However, melting within such confined shells involves complex interactions among heat conduction, natural convection and geometric boundary constraints (Khodadadi & Zhang Reference Khodadadi and Zhang2001). Thorough investigations of these interactions are essential to unlock the full potential of encapsulated PCMs in TESs.

The melting process of encapsulated PCMs has been extensively investigated experimentally, theoretically and numerically. Two distinct melting mechanisms have been identified as unconstrained and constrained melting (Tan Reference Tan2008). In unconstrained melting, the solid PCM sinks under gravity, leading to direct contact melting at the bottom of the shell. On the contrary, constrained melting occurs when the PCM is physically restricted from moving downward within the capsule. A range of experimental studies have explored the complex phase-change dynamics within spherical PCM capsules. Moore & Bayazitoglu (Reference Moore and Bayazitoglu1982) were among the first to investigate unconstrained melting, reporting that the drop of the solid phase induces internal flow within the capsule. Khodadadi & Zhang (Reference Khodadadi and Zhang2001) conducted a combined experimental and numerical study on constrained melting with buoyancy-driven convection. They revealed the transition from conduction-driven heat transfer in the early stages to a convection-dominated regime as the melted layer grows. Tan (Reference Tan2008) further experimentally compared constrained and unconstrained melting of an n-octadecane PCM in transparent spherical containers, demonstrating that the geometric constraint significantly delays the onset of convection and alters both the temperature distribution and the melting front. In a more recent study, Fan et al. (Reference Fan, Zhu, Liu, Xu, Zeng, Lu and Yu2016) experimentally examined the constrained melting of graphene-enhanced PCMs in spherical capsules. Their results showed that, although graphene nanosheets enhance the overall thermal conductivity, the associated increase in viscosity suppresses natural convection and thereby slows down the melting process. Despite the valuable insights gained from experiments, it is often challenging to maintain target boundary temperatures or to visualise fluid motion and the temperature distribution. These limitations in experimental studies hinder a comprehensive understanding of melting mechanisms, particularly under conditions where natural convection plays a critical role in constrained melting (Tan et al. Reference Tan, Hosseinizadeh, Khodadadi and Fan2009).

In theoretical studies, analytical solutions and semi-empirical correlations have been developed primarily for unconstrained melting, aimed at predicting melting rates and heat transfer under various boundary conditions (Roy & Sengupta Reference Roy and Sengupta1987; Fomin & Saitoh Reference Fomin and Saitoh1999). In contrast, constrained melting has received less theoretical attention (Kenisarin et al. Reference Kenisarin, Mahkamov, Costa and Makhkamova2020). A common approach is to introduce an effective thermal conductivity (

![]() $k_\textit{eff}$

) to indirectly account for convection effects, thereby reducing the problem to a pure conduction framework (Gao, Yao & Wu Reference Gao, Yao and Wu2019). Although computationally efficient, this treatment neglects the internal fluid dynamics and loses accuracy in systems with high Rayleigh numbers or strong natural convection. Overall, existing theoretical studies for PCM melting primarily rely on simplifications and approximations. In addition, the impact of natural convection is simplified through empirical correlations rather than being directly resolved.

$k_\textit{eff}$

) to indirectly account for convection effects, thereby reducing the problem to a pure conduction framework (Gao, Yao & Wu Reference Gao, Yao and Wu2019). Although computationally efficient, this treatment neglects the internal fluid dynamics and loses accuracy in systems with high Rayleigh numbers or strong natural convection. Overall, existing theoretical studies for PCM melting primarily rely on simplifications and approximations. In addition, the impact of natural convection is simplified through empirical correlations rather than being directly resolved.

Compared with experimental and theoretical approaches, numerical simulations have become a powerful and versatile tool for investigating the melting of PCMs, enabling detailed insights into the flow dynamics, melting mechanisms and parametric effects with greater flexibility and resolutions. Conventional numerical methods, such as the finite difference method (FDM), finite volume method (FVM) and finite element method, have been widely applied in this context. Khodadadi & Zhang (Reference Khodadadi and Zhang2001) were among the first to utilise the FVM to simulate constrained melting of PCMs and systematically analyse the effects of the Stefan number and Prandtl number on the melting process. The FDM was also applied to model paraffin PCM melting in spherical capsules, introducing a model containing

![]() $k_\textit{eff}$

to approximate the influence of natural convection (Alphonse, Solanki & Saini Reference Alphonse, Solanki and Saini2006). Assis et al. (Reference Assis, Katsman, Ziskind and Letan2007) utilised Fluent 6.0 to simulate unconstrained melting and proposed empirical correlations for liquid fraction evolution based on data fitting. This framework was later extended to constrained melting, by incorporating a single-domain enthalpy method combined with a Darcy damping term to account for the effects of phase change on convection flow (Tan et al. Reference Tan, Hosseinizadeh, Khodadadi and Fan2009). Their results revealed the presence of strong thermal stratification and the development of an unstable thermal layer near the bottom.

$k_\textit{eff}$

to approximate the influence of natural convection (Alphonse, Solanki & Saini Reference Alphonse, Solanki and Saini2006). Assis et al. (Reference Assis, Katsman, Ziskind and Letan2007) utilised Fluent 6.0 to simulate unconstrained melting and proposed empirical correlations for liquid fraction evolution based on data fitting. This framework was later extended to constrained melting, by incorporating a single-domain enthalpy method combined with a Darcy damping term to account for the effects of phase change on convection flow (Tan et al. Reference Tan, Hosseinizadeh, Khodadadi and Fan2009). Their results revealed the presence of strong thermal stratification and the development of an unstable thermal layer near the bottom.

Despite the success of conventional numerical simulations, they often face challenges in handling moving boundaries, complex geometries and multiphysics coupling. In recent decades, the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) has emerged as a promising alternative for simulating phase change and fluid flow, owing to its strengths in parallel computing, complex boundary handling and multiphysics coupling (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Yang, Lei and Luo2023; Lei et al. Reference Lei, Yang, Wang, Chen, He and Luo2024b ; Liu, He & Luo Reference Liu, He and Luo2025a , Reference Liu, Tong and Heb ). Jourabian et al. (Reference Jourabian, Rabienataj Darzi, Akbari and Toghraie2020) simulated the melting of graphene-enhanced PCM in an inclined elliptical annulus at the representative elementary volume (REV) scale. Their results demonstrated that the inclination angle significantly affects internal convection and the overall melting rate. More recently, Ghannam, Abu-Nada & Alazzam (Reference Ghannam, Abu-Nada and Alazzam2024) developed a hybrid LBM–FDM model to simulate micro-PCM suspensions in a minichannel at the REV scale, capturing particle–fluid interactions, phase change and heat transfer under varying particle densities and volume fractions. Despite providing valuable insights into melting characteristics, these REV-scale studies did not directly track the melting process, but instead represented it through latent heat source terms and empirical correlations. In parallel, some pore-scale efforts have been undertaken to address this limitation. For instance, Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Wang, Ma, Wang and Zhang2018) applied enthalpy-based LBM to simulate melting in encapsulated PCMs at the pore scale, successfully capturing the coupled heat transfer and flow evolution without relying on empirical correlations. Similarly, a pore-scale enthalpy-based LBM was employed to evaluate the melting performance of composite PCMs with varying latent heat and melting temperatures, providing valuable guidance for the selection of PCM materials (Li et al. Reference Li, Cui, Simon, Ma, Cui and Wang2021). Although these few available pore-scale studies have directly tracked phase-change processes, the phase interface is typically represented implicitly using either phase-field parameters or enthalpy-based formulations. Such purely Eulerian treatments produce a finite-thickness interface, resulting in a diffused transition zone that compromises the accuracy of interface dynamics capture (Huang & Wu Reference Huang and Wu2014). Moreover, the fundamental melting mechanisms have not been thoroughly explored for various parameters, and the phase-change rate and melting evolution have not been quantified by reliable predictive correlations. In particular, constrained melting typically involves an initial conduction-dominated stage followed by a convection-governed stage (Khodadadi & Zhang Reference Khodadadi and Zhang2001). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no widely accepted correlation currently exists to describe the dynamics of this multi-stage melting behaviour (Kenisarin et al. Reference Kenisarin, Mahkamov, Costa and Makhkamova2020).

To address these research gaps, this study conducts a detailed pore-scale investigation of encapsulated PCM melting with natural convection. A multiple-relaxation-time (MRT) LBM is applied to solve the coupled fluid flow and thermal fields, while the immersed boundary (IB) method is used to explicitly track the phase-change interface as a sharply defined and infinitesimally thin boundary. To overcome the limitations of traditional schemes under strong convection, an innovative phase identification scheme is incorporated into the IB–LBM framework, significantly enhancing its accuracy and robustness. This improved framework enables in-depth exploration of the underlying melting mechanisms. The effects of key parameters, including boundary temperature, capsule size and initial subcooling, are systematically examined, and the melting evolution is quantitatively characterised.

2. Governing equations and numerical methods

2.1. Governing equations

At the pore scale, the thermal fluid flow during PCM melting is governed by the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations and the advection–diffusion equation as

Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol{u} = (u, v)$

denotes the velocity field,

$\boldsymbol{u} = (u, v)$

denotes the velocity field,

![]() $\rho _0$

is the fluid density,

$\rho _0$

is the fluid density,

![]() $t$

represents time and

$t$

represents time and

![]() $p$

is the pressure. The dynamic viscosity is given by

$p$

is the pressure. The dynamic viscosity is given by

![]() $\mu = \rho _0 \nu$

, where

$\mu = \rho _0 \nu$

, where

![]() $\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity,

$\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity,

![]() $T$

is the temperature field and

$T$

is the temperature field and

![]() $\alpha$

is the thermal diffusivity. The parameters

$\alpha$

is the thermal diffusivity. The parameters

![]() $\boldsymbol{f_b}$

and

$\boldsymbol{f_b}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{f_s}$

are the body forces applied to the flow, which are introduced by the gravity difference and IB, respectively. Likewise,

$\boldsymbol{f_s}$

are the body forces applied to the flow, which are introduced by the gravity difference and IB, respectively. Likewise,

![]() $q_b$

and

$q_b$

and

![]() $q_s$

represent external and IB-induced heat sources, respectively. Applying the Boussinesq approximation, the fluid density is treated as constant

$q_s$

represent external and IB-induced heat sources, respectively. Applying the Boussinesq approximation, the fluid density is treated as constant

![]() $\rho _0$

except in the buoyancy term, which is expressed as

$\rho _0$

except in the buoyancy term, which is expressed as

Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol{g}$

denotes gravitational acceleration,

$\boldsymbol{g}$

denotes gravitational acceleration,

![]() $\beta$

is the thermal expansion coefficient and

$\beta$

is the thermal expansion coefficient and

![]() $T_{\textit{ref}}$

is the reference temperature.

$T_{\textit{ref}}$

is the reference temperature.

To capture the interaction between the fluid and IB, both Eulerian and Lagrangian coordinate systems are employed. The transformations between the two coordinate systems are described as follows (Shu, Ren & Yang Reference Shu, Ren and Yang2013):

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}$

and

$\boldsymbol{x}$

and

![]() $s$

are the Eulerian and Lagrangian coordinates, respectively, while

$s$

are the Eulerian and Lagrangian coordinates, respectively, while

![]() $\varOmega$

and

$\varOmega$

and

![]() $\varGamma$

represent the Eulerian and Lagrangian domains. The function

$\varGamma$

represent the Eulerian and Lagrangian domains. The function

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}(s, t)$

maps a Lagrangian point to its corresponding Eulerian position. The capitalised symbols

$\boldsymbol{X}(s, t)$

maps a Lagrangian point to its corresponding Eulerian position. The capitalised symbols

![]() $\boldsymbol{F_s}$

,

$\boldsymbol{F_s}$

,

![]() $Q_s$

,

$Q_s$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{U_{\!s}}$

and

$\boldsymbol{U_{\!s}}$

and

![]() $T_s$

denote the body force, heat source, velocity and temperature of the IB, respectively. The Dirac delta function

$T_s$

denote the body force, heat source, velocity and temperature of the IB, respectively. The Dirac delta function

![]() $\delta$

is used to couple the two coordinate systems and will be explained in § 2.2.2.

$\delta$

is used to couple the two coordinate systems and will be explained in § 2.2.2.

To characterise the PCM melting process, four key dimensionless parameters are introduced, the Rayleigh number (

![]() $Ra$

), the Stefan number (

$Ra$

), the Stefan number (

![]() $\textit{Ste}$

), the Prandtl number (

$\textit{Ste}$

), the Prandtl number (

![]() $\textit{Pr}$

) and the Fourier number (

$\textit{Pr}$

) and the Fourier number (

![]() $\textit{Fo}$

), which are defined as

$\textit{Fo}$

), which are defined as

In these definitions,

![]() $T_b$

and

$T_b$

and

![]() $T_m$

are the boundary temperature and melting temperature, respectively.

$T_m$

are the boundary temperature and melting temperature, respectively.

![]() $l_c$

is the characteristic length,

$l_c$

is the characteristic length,

![]() $C_{\!p}$

is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure and

$C_{\!p}$

is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure and

![]() $L$

is the latent heat of fusion.

$L$

is the latent heat of fusion.

2.2. Numerical models

In this study, the direct-forcing IB–LBM framework is adopted to solve the above governing equation system (2.1)–(2.8), in which the IB method tracks the melting interface evolution while the LBM models the thermal fluid flow, following the approaches of Kang & Hassan (Reference Kang and Hassan2011) and Huang & Wu (Reference Huang and Wu2014).

2.2.1. Lattice Boltzmann method

A two-dimensional nine-velocity (D2Q9) MRT–LBM is utilised to solve the thermal fluid flow described by (2.1)–(2.3) (Lei et al. Reference Lei, Wang, Yang, Chen and Luo2024a ). The evolution equations for the particle distribution functions are written as (Guo & Zheng Reference Guo and Zheng2008; Lei, Wang & Luo Reference Lei, Wang and Luo2021; Yang et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Yang, Lei and Luo2023)

\begin{eqnarray} g_i(\boldsymbol{x} + \boldsymbol{e}_i \delta _t, t + \delta _t) - g_i(\boldsymbol{x}, t) &=& -\big ( \boldsymbol{M}^{-1} \boldsymbol{S} \boldsymbol{M} \big )_\textit{ij} \left [ g_j(\boldsymbol{x}, t) - g_j^{\textit{eq}}(\boldsymbol{x}, t) \right ] \nonumber \\ &&+\, \delta _t \big ( \boldsymbol{M}^{-1} (\boldsymbol{I} - 0.5 \boldsymbol{S}) \boldsymbol{M} \big )_\textit{ij} \bar {\boldsymbol{f_{\!j}}}, \\[-24pt]\nonumber \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} g_i(\boldsymbol{x} + \boldsymbol{e}_i \delta _t, t + \delta _t) - g_i(\boldsymbol{x}, t) &=& -\big ( \boldsymbol{M}^{-1} \boldsymbol{S} \boldsymbol{M} \big )_\textit{ij} \left [ g_j(\boldsymbol{x}, t) - g_j^{\textit{eq}}(\boldsymbol{x}, t) \right ] \nonumber \\ &&+\, \delta _t \big ( \boldsymbol{M}^{-1} (\boldsymbol{I} - 0.5 \boldsymbol{S}) \boldsymbol{M} \big )_\textit{ij} \bar {\boldsymbol{f_{\!j}}}, \\[-24pt]\nonumber \end{eqnarray}

for

![]() $i=0,1,\ldots ,8$

, representing discrete velocity directions. Here,

$i=0,1,\ldots ,8$

, representing discrete velocity directions. Here,

![]() $g_i(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

and

$g_i(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

and

![]() $h_i(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

are distribution functions for density and temperature, respectively,

$h_i(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

are distribution functions for density and temperature, respectively,

![]() $\boldsymbol{e}_i$

denotes the discrete velocity set and

$\boldsymbol{e}_i$

denotes the discrete velocity set and

![]() $\delta _t$

is the time step. The parameters

$\delta _t$

is the time step. The parameters

![]() $\boldsymbol{S}$

and

$\boldsymbol{S}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{S_T}$

are diagonal relaxation matrices for

$\boldsymbol{S_T}$

are diagonal relaxation matrices for

![]() $\boldsymbol{g}$

and

$\boldsymbol{g}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{h}$

. The equilibrium distribution functions are defined as (Krueger et al. Reference Krueger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2016)

$\boldsymbol{h}$

. The equilibrium distribution functions are defined as (Krueger et al. Reference Krueger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2016)

where

![]() $w_i$

are the lattice weights, and

$w_i$

are the lattice weights, and

![]() $c_s$

is the lattice sound velocity. The variable

$c_s$

is the lattice sound velocity. The variable

![]() $\rho _{\!p}$

is related to the pressure via

$\rho _{\!p}$

is related to the pressure via

![]() $p = c_s^2 \rho _{\!p}$

. The force distribution functions

$p = c_s^2 \rho _{\!p}$

. The force distribution functions

![]() $\bar {\boldsymbol{f}}_i$

and

$\bar {\boldsymbol{f}}_i$

and

![]() $\bar {q}_i$

are given by (Lei et al. Reference Lei, Wang, Yang, Chen and Luo2024a

)

$\bar {q}_i$

are given by (Lei et al. Reference Lei, Wang, Yang, Chen and Luo2024a

)

For both the fluid flow and the temperature distribution, the same transformation matrix

![]() $\boldsymbol{M}$

for the D2Q9 model is used as Lallemand & Luo (2000), which is

$\boldsymbol{M}$

for the D2Q9 model is used as Lallemand & Luo (2000), which is

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{M} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ -4 & -1 & -1 & -1 & -1 & 2 & 2 & 2 & 2 \\ 4 & -2 & -2 & -2 & -2 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 1 & -1 & -1 & 1 \\ 0 & -2 & 0 & 2 & 0 & 1 & -1 & -1 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 1 & -1 & -1 \\ 0 & 0 & -2 & 0 & 2 & 1 & 1 & -1 & -1 \\ 0 & 1 & -1 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 1 & -1 \end{pmatrix}\!. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{M} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ -4 & -1 & -1 & -1 & -1 & 2 & 2 & 2 & 2 \\ 4 & -2 & -2 & -2 & -2 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 1 & -1 & -1 & 1 \\ 0 & -2 & 0 & 2 & 0 & 1 & -1 & -1 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 1 & -1 & -1 \\ 0 & 0 & -2 & 0 & 2 & 1 & 1 & -1 & -1 \\ 0 & 1 & -1 & 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 1 & -1 \end{pmatrix}\!. \end{equation}

This matrix maps the distribution functions

![]() $\boldsymbol{g}$

and

$\boldsymbol{g}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{h}$

into moment space, yielding

$\boldsymbol{h}$

into moment space, yielding

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{g}} = \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{g}$

and

$\hat {\boldsymbol{g}} = \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{g}$

and

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{h}} = \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{h}$

. The evolution equations in moment space become

$\hat {\boldsymbol{h}} = \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{h}$

. The evolution equations in moment space become

The equilibrium moments are defined as

The corresponding force moments,

![]() $\hat {\kern -2pt \boldsymbol{f}}$

and

$\hat {\kern -2pt \boldsymbol{f}}$

and

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}$

are expressed as

$\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}$

are expressed as

The macroscopic variables, including fluid density, velocity and temperature, can be recovered from the distribution functions using (Lei et al. 2023)

The relaxation times

![]() $\tau$

and

$\tau$

and

![]() $\tau _T$

are related to the kinematic viscosity and thermal diffusivity by Chapman–Enskog analysis as (Guo & Zheng 2009)

$\tau _T$

are related to the kinematic viscosity and thermal diffusivity by Chapman–Enskog analysis as (Guo & Zheng 2009)

For the boundary conditions, the half-way bounce-back scheme (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Shi, Guo, Chai and Lu2012) and the non-equilibrium extrapolation method (Krueger et al. Reference Krueger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2016) are utilised. In all simulations, the maximum velocity remains below 0.06 in lattice units (corresponding to

![]() $Ma \lt 0.1$

), ensuring that compressibility effects are negligible.

$Ma \lt 0.1$

), ensuring that compressibility effects are negligible.

2.2.2. Immersed boundary

The direct-forcing IB method is applied in the Lagrangian coordinate to explicitly track the motion of the phase interface (Kang & Hassan Reference Kang and Hassan2011; Huang & Wu Reference Huang and Wu2014). To enable coupling between the Eulerian and Lagrangian coordinates, a smooth approximation of the Dirac delta function in a two-dimensional domain is adopted as

where

![]() $d(r)$

is a one-dimensional regularised Dirac delta function defined as (Peskin 2002)

$d(r)$

is a one-dimensional regularised Dirac delta function defined as (Peskin 2002)

\begin{equation} d(r) = \begin{cases} 1 - |r|, & \text{if } |r| \lt 1, \\ 0, & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} d(r) = \begin{cases} 1 - |r|, & \text{if } |r| \lt 1, \\ 0, & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} \end{equation}

After the LBM step, the intermediate macroscopic velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}^*$

and temperature

$\boldsymbol{u}^*$

and temperature

![]() $T^*$

are obtained without the influence of the IB forces

$T^*$

are obtained without the influence of the IB forces

![]() $\boldsymbol{f}_{\!s}$

and heat source

$\boldsymbol{f}_{\!s}$

and heat source

![]() $q_s$

. These values are then interpolated to the Lagrangian points to compute the temporary velocity

$q_s$

. These values are then interpolated to the Lagrangian points to compute the temporary velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{U}_s^*$

and temperature

$\boldsymbol{U}_s^*$

and temperature

![]() $T_s^*$

of the IB, which can be derived from (2.7) and (2.8) as

$T_s^*$

of the IB, which can be derived from (2.7) and (2.8) as

The desired velocity and temperature of the IB, which will be detailed in § 2.3, are then used to calculate the Lagrangian force and heat source using the direct-forcing IB scheme (Feng & Michaelides Reference Feng and Michaelides2005; Kang & Hassan Reference Kang and Hassan2011)

Once the Lagrangian force and heat source are determined, they are distributed back to the Eulerian grid through (2.5) and (2.6) as

With the Eulerian force and heat source terms obtained, the fluid velocity is corrected using (2.23) as

With the velocity, force and heat source terms all updated, the LBM proceeds to the next time step.

2.3. Phase interface treatment

At the phase-change interface, the temperature should remain at the melting point as

![]() $T_s^d = T_m$

. The corresponding heat source at the IB,

$T_s^d = T_m$

. The corresponding heat source at the IB,

![]() $Q_s$

, is calculated using (2.30). To determine the desired interface velocity, this study adopts a local energy balance approach instead of relying on temperature gradients. Specifically, the latent heat released during a time step equals the thermal energy applied to the interface within the same interval (Huang & Wu Reference Huang and Wu2014), thereby

$Q_s$

, is calculated using (2.30). To determine the desired interface velocity, this study adopts a local energy balance approach instead of relying on temperature gradients. Specifically, the latent heat released during a time step equals the thermal energy applied to the interface within the same interval (Huang & Wu Reference Huang and Wu2014), thereby

Here,

![]() $l_{s_n}$

is the segment length associated with a single Lagrangian point on the IB. Solving for the interface velocity yields

$l_{s_n}$

is the segment length associated with a single Lagrangian point on the IB. Solving for the interface velocity yields

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{n_n}$

is the unit normal vector of the phase interface. Compared with gradient-based methods, this local formulation avoids the spatial derivatives, making it more suitable for parallel computing.

$\boldsymbol{n_n}$

is the unit normal vector of the phase interface. Compared with gradient-based methods, this local formulation avoids the spatial derivatives, making it more suitable for parallel computing.

As the phase interface evolves, the spacing between adjacent Lagrangian points changes dynamically. To maintain numerical stability and accuracy, this spacing must be carefully regulated, as excessively large distances degrade accuracy, while overly small distances induce numerical instability. To address this, Lagrangian points are adaptively inserted or removed at each time step. Numerical tests suggested that the point spacing should be less than

![]() ${\rm d}x$

to ensure accuracy (Huang & Wu Reference Huang and Wu2014). In this study, the spacing is constrained within the range of

${\rm d}x$

to ensure accuracy (Huang & Wu Reference Huang and Wu2014). In this study, the spacing is constrained within the range of

![]() $0.4\,{\rm d}x$

to

$0.4\,{\rm d}x$

to

![]() $0.8\,{\rm d}x$

.

$0.8\,{\rm d}x$

.

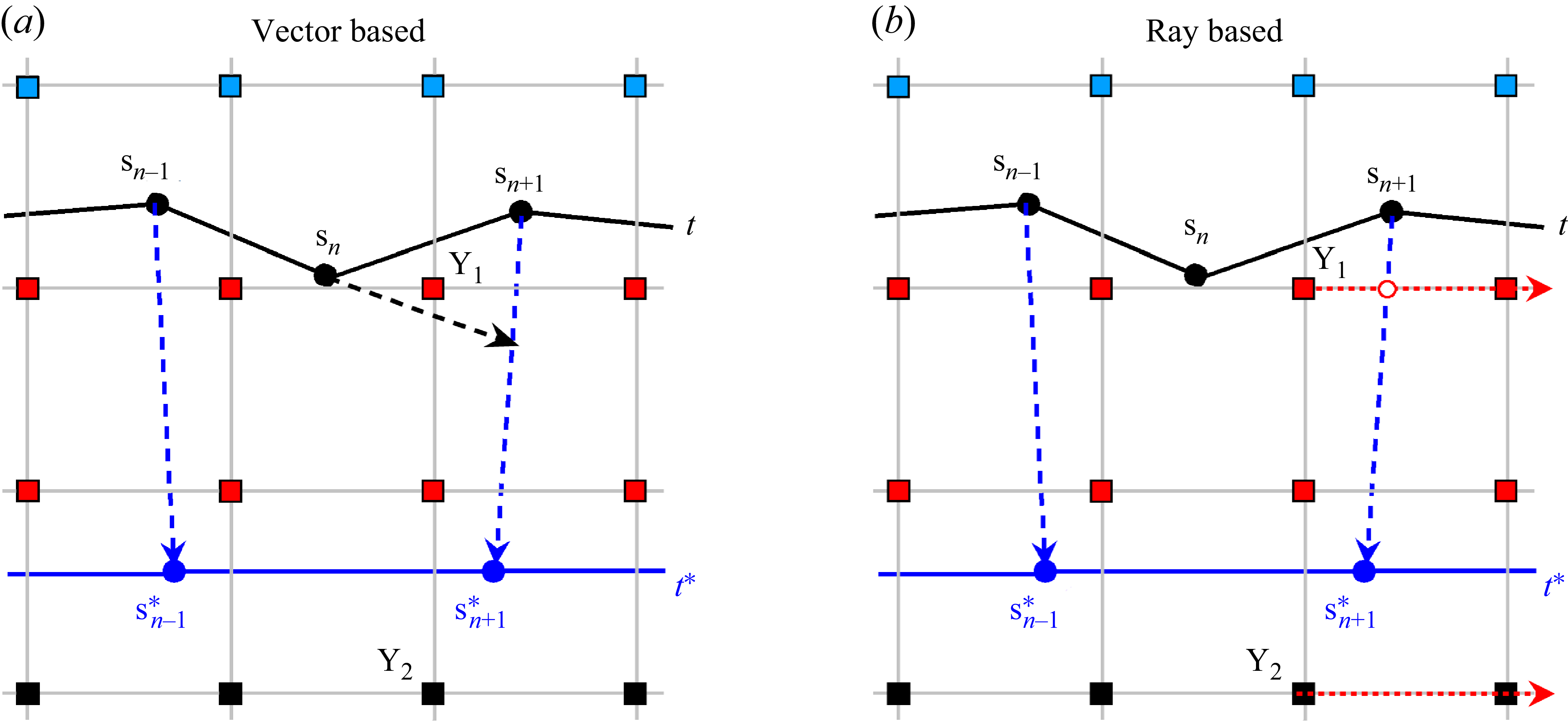

Figure 1. Illustration of two types of points (inside

![]() ${Y_1}$

and outside

${Y_1}$

and outside

![]() ${Y_2}$

) in the phase identification process of Eulerian points using the (a) vector-based method and (b) ray-based method. Blue and black square markers represent Eulerian points located in the liquid and solid phases, respectively. Red square markers identify those Eulerian points that undergo phase transition within the next time step.

${Y_2}$

) in the phase identification process of Eulerian points using the (a) vector-based method and (b) ray-based method. Blue and black square markers represent Eulerian points located in the liquid and solid phases, respectively. Red square markers identify those Eulerian points that undergo phase transition within the next time step.

Additionally, each Eulerian point is assigned to a single phase state, either solid or liquid. For points within the solid phase, the velocity is set to zero; once they transition into the liquid phase upon melting, a velocity is imposed to ensure accurate modelling of the temperature profile. Consequently, the phase states of Eulerian points must be updated at each time step to capture the evolution of phase interface accurately. The vector-based approach proposed by Huang & Wu (Reference Huang and Wu2014) is commonly used to determine phase transition by checking whether an Eulerian point consistently lies to the right side of all boundary segments. Although effective under low-

![]() $Ra$

conditions, where the interface is relatively flat or convex, this method becomes less reliable in high-

$Ra$

conditions, where the interface is relatively flat or convex, this method becomes less reliable in high-

![]() $Ra$

cases with concave interface geometries, sometimes failing to capture phase changes correctly. Figure 1(a) illustrates this limitation. Consider a representative case where three Lagrangian points (

$Ra$

cases with concave interface geometries, sometimes failing to capture phase changes correctly. Figure 1(a) illustrates this limitation. Consider a representative case where three Lagrangian points (

![]() ${s_{n-1}}$

,

${s_{n-1}}$

,

![]() ${s_n}$

,

${s_n}$

,

![]() ${s_{n+1}}$

) at the time step

${s_{n+1}}$

) at the time step

![]() $t$

, forming a concave phase interface, are merged into two points (

$t$

, forming a concave phase interface, are merged into two points (

![]() ${s_{n-1}^*}$

,

${s_{n-1}^*}$

,

![]() ${s_{n+1}^*}$

) at the subsequent time step

${s_{n+1}^*}$

) at the subsequent time step

![]() $t^*$

. In this process, only the Eulerian points located within the newly formed polygon, denoted by red squares, should undergo phase change, while the points outside the polygon should remain unchanged. However, the vector-based method fails to identify point

$t^*$

. In this process, only the Eulerian points located within the newly formed polygon, denoted by red squares, should undergo phase change, while the points outside the polygon should remain unchanged. However, the vector-based method fails to identify point

![]() ${Y_1}$

, as it lies on the left side of

${Y_1}$

, as it lies on the left side of

![]() $\overrightarrow {\boldsymbol{s_{n-1}s_n}}$

, omitting necessary phase changes. To overcome this limitation, this study introduces a novel ray-based method. As shown in figure 1(b), for a given Eulerian point

$\overrightarrow {\boldsymbol{s_{n-1}s_n}}$

, omitting necessary phase changes. To overcome this limitation, this study introduces a novel ray-based method. As shown in figure 1(b), for a given Eulerian point

![]() $Y_1$

(or

$Y_1$

(or

![]() $Y_2$

), a horizontal ray is cast to the right. The number of intersections between this ray and the polygonal geometry boundary determines whether the point lies inside the region. If the intersection count is odd (e.g.

$Y_2$

), a horizontal ray is cast to the right. The number of intersections between this ray and the polygonal geometry boundary determines whether the point lies inside the region. If the intersection count is odd (e.g.

![]() $Y_1$

), the point is classified as inside and its phase state is updated; if even (e.g.

$Y_1$

), the point is classified as inside and its phase state is updated; if even (e.g.

![]() $Y_2$

), it is classified as outside and remains unchanged. This ray-based method ensures robust and accurate phase classification for arbitrarily shaped interfaces, particularly under high-

$Y_2$

), it is classified as outside and remains unchanged. This ray-based method ensures robust and accurate phase classification for arbitrarily shaped interfaces, particularly under high-

![]() $Ra$

conditions, and is also efficient for parallel computing.

$Ra$

conditions, and is also efficient for parallel computing.

3. Validation and problem description

To verify the accuracy and applicability of the proposed IB–LBM approach for phase-change problems, numerical simulations are conducted on three representative benchmark cases, which include (i) a one-dimensional Stefan problem, (ii) natural convection melting in a square cavity and (iii) melting in a spherical container. The simulation results are systematically compared with analytical, numerical and experimental data from the literature.

3.1. One-dimensional Stefan problem

The first validation case considers the classical one-dimensional Stefan problem without fluid motion, aiming to demonstrate the capability of the present IB–LBM approach in handling solid–liquid-phase change driven purely by conduction. As illustrated in figure 2(a), a semi-infinite domain is initially filled with solid at a uniform temperature

![]() $T_0$

, which is below the melting point

$T_0$

, which is below the melting point

![]() $T_m$

. At time

$T_m$

. At time

![]() $t=0$

, the left boundary temperature is instantaneously raised to

$t=0$

, the left boundary temperature is instantaneously raised to

![]() $T_b$

(

$T_b$

(

![]() $T_b \gt T_m$

), inducing melting through heat conduction.

$T_b \gt T_m$

), inducing melting through heat conduction.

Figure 2. One-dimensional Stefan problem without fluid motion: (a) schematic of the problem set-up, (b) comparison of phase interface location

![]() $X_i$

between IB–LBM results and the analytical solution, (c) temperature distribution at

$X_i$

between IB–LBM results and the analytical solution, (c) temperature distribution at

![]() $t = 1000$

,

$t = 1000$

,

![]() $4000$

and

$4000$

and

![]() $10\,000$

comparing IB–LBM and analytical results.

$10\,000$

comparing IB–LBM and analytical results.

The boundary conditions are specified as

with periodic boundary conditions applied in the vertical direction. The analytical solution for the moving solid–liquid interface position is given by (Özışık 1993)

where

![]() $\eta$

is the root of the transcendental equation

$\eta$

is the root of the transcendental equation

The temperature distribution in both the liquid and solid phases can also be expressed analytically as (Özışık 1993)

\begin{equation} T(x,t) = \begin{cases} T_b - \dfrac {(T_b - T_m) \textit{erf}\left(\dfrac {x}{2 \sqrt {\alpha t}}\right)}{\textit{erf}(\eta )} &, 0 \lt x \leq X_i(t), \\[1ex] T_0 + \dfrac {(T_m - T_0) \textit{erfc}\left(\dfrac {x}{2 \sqrt {\alpha t}}\right)}{\textit{erfc}(\eta )} &, x \geq X_i(t). \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} T(x,t) = \begin{cases} T_b - \dfrac {(T_b - T_m) \textit{erf}\left(\dfrac {x}{2 \sqrt {\alpha t}}\right)}{\textit{erf}(\eta )} &, 0 \lt x \leq X_i(t), \\[1ex] T_0 + \dfrac {(T_m - T_0) \textit{erfc}\left(\dfrac {x}{2 \sqrt {\alpha t}}\right)}{\textit{erfc}(\eta )} &, x \geq X_i(t). \end{cases} \end{equation}

In the present simulation, the parameters are set as

![]() $\delta _x = 0.1$

,

$\delta _x = 0.1$

,

![]() $T_0 = 0$

,

$T_0 = 0$

,

![]() $T_m = 1/3$

,

$T_m = 1/3$

,

![]() $T_b = 1$

,

$T_b = 1$

,

![]() $\alpha = 0.05$

and

$\alpha = 0.05$

and

![]() $C_{\!p}/L = 0.3$

. Figure 2(b) compares the evolution of the phase interface location

$C_{\!p}/L = 0.3$

. Figure 2(b) compares the evolution of the phase interface location

![]() $X_i$

obtained from the IB–LBM with the analytical solution given in (3.2). Excellent agreement is observed throughout the entire simulation period. Furthermore, figure 2(c) presents the temperature distributions at

$X_i$

obtained from the IB–LBM with the analytical solution given in (3.2). Excellent agreement is observed throughout the entire simulation period. Furthermore, figure 2(c) presents the temperature distributions at

![]() $t = 1000$

,

$t = 1000$

,

![]() $4000$

and

$4000$

and

![]() $10\,000$

, again demonstrating good consistency between the IB–LBM and analytical results. To quantitatively assess the accuracy of the simulation, the global relative errors in both the interface position and the temperature field are calculated as

$10\,000$

, again demonstrating good consistency between the IB–LBM and analytical results. To quantitatively assess the accuracy of the simulation, the global relative errors in both the interface position and the temperature field are calculated as

where the subscripts

![]() ${num}$

and

${num}$

and

![]() ${ana}$

denote numerical and analytical values, respectively. The computed relative errors for the interface location and temperature are

${ana}$

denote numerical and analytical values, respectively. The computed relative errors for the interface location and temperature are

![]() $E_X = 0.168\,\%$

and

$E_X = 0.168\,\%$

and

![]() $E_T = 0.271\,\%$

, respectively, confirming the high accuracy of the present IB–LBM approach in tracking the phase interface and resolving the temperature field.

$E_T = 0.271\,\%$

, respectively, confirming the high accuracy of the present IB–LBM approach in tracking the phase interface and resolving the temperature field.

3.2. Natural convection melting in a square cavity

Figure 3. Convection melting within a square cavity: (a) problem schematic, (b) comparison of average Nusselt number

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

among the present IB–LBM, the enthalpy-based LBM by Huang, Wu & Cheng (Reference Huang, Wu and Cheng2013) and the control volume method by Mencinger (Reference Mencinger2004), (c) comparison of phase interface locations at

$\textit{Nu}$

among the present IB–LBM, the enthalpy-based LBM by Huang, Wu & Cheng (Reference Huang, Wu and Cheng2013) and the control volume method by Mencinger (Reference Mencinger2004), (c) comparison of phase interface locations at

![]() $\textit{Fo}=4.0$

,

$\textit{Fo}=4.0$

,

![]() $10.0$

,

$10.0$

,

![]() $20.0$

and

$20.0$

and

![]() $30.0$

.

$30.0$

.

To further assess the performance of the proposed IB–LBM framework in capturing convection-driven phase change, a benchmark case of natural convection melting within a square cavity is considered. As shown in figure 3(a), the computational domain is a square cavity with length

![]() $l_c$

, initially filled with solid PCM at the melting temperature

$l_c$

, initially filled with solid PCM at the melting temperature

![]() $T_m$

. The left vertical wall is heated to a higher temperature

$T_m$

. The left vertical wall is heated to a higher temperature

![]() $T_b$

(

$T_b$

(

![]() $T_b \gt T_m$

), while the right wall is kept at

$T_b \gt T_m$

), while the right wall is kept at

![]() $T_m$

throughout the simulation. This temperature difference induces melting along the heated left wall, and natural convection subsequently develops in the melted region, driving the phase change to the right side. The boundary conditions for velocity and temperature fields are specified as follows:

$T_m$

throughout the simulation. This temperature difference induces melting along the heated left wall, and natural convection subsequently develops in the melted region, driving the phase change to the right side. The boundary conditions for velocity and temperature fields are specified as follows:

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{u}(0,y) &= (0,0), &\quad &T(0,y) = T_b, \\ \boldsymbol{u}(l_c,y) &= (0,0), &\quad &T(l_c,y) = T_m, \\ \boldsymbol{u}(x,0) &= (0,0), &\quad &\frac {\partial T}{\partial y}(x,0) = 0, \\ \boldsymbol{u}(x,l_c) &= (0,0), &\quad &\frac {\partial T}{\partial y}(x,l_c) = 0. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{u}(0,y) &= (0,0), &\quad &T(0,y) = T_b, \\ \boldsymbol{u}(l_c,y) &= (0,0), &\quad &T(l_c,y) = T_m, \\ \boldsymbol{u}(x,0) &= (0,0), &\quad &\frac {\partial T}{\partial y}(x,0) = 0, \\ \boldsymbol{u}(x,l_c) &= (0,0), &\quad &\frac {\partial T}{\partial y}(x,l_c) = 0. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

The dimensionless parameters are set to

![]() $Ra = 2.5 \times 10^4$

,

$Ra = 2.5 \times 10^4$

,

![]() $\textit{Ste} = 0.01$

and

$\textit{Ste} = 0.01$

and

![]() $\textit{Pr} = 0.02$

. The simulation parameters are chosen as

$\textit{Pr} = 0.02$

. The simulation parameters are chosen as

![]() $l_c = 1.0$

,

$l_c = 1.0$

,

![]() $\delta _x = \delta _t = 1/128$

,

$\delta _x = \delta _t = 1/128$

,

![]() $T_b = 1.0$

,

$T_b = 1.0$

,

![]() $T_m = 0.0$

,

$T_m = 0.0$

,

![]() $|\boldsymbol{g}| = 1.0$

and

$|\boldsymbol{g}| = 1.0$

and

![]() $\beta = 0.0025$

. Natural convection is simulated using the Boussinesq approximation, where buoyancy effects are incorporated through (2.4). To quantify heat transfer performance, the average Nusselt number along the heated wall is calculated as

$\beta = 0.0025$

. Natural convection is simulated using the Boussinesq approximation, where buoyancy effects are incorporated through (2.4). To quantify heat transfer performance, the average Nusselt number along the heated wall is calculated as

\begin{equation} \textit{Nu} = \frac {\displaystyle \int _{0}^{l_c} q_x \,{\rm d} y}{k \bigl ( T_b - T_m \bigr )}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \textit{Nu} = \frac {\displaystyle \int _{0}^{l_c} q_x \,{\rm d} y}{k \bigl ( T_b - T_m \bigr )}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $q_x$

is the heat flux in the

$q_x$

is the heat flux in the

![]() $x$

-direction at the left wall, and

$x$

-direction at the left wall, and

![]() $k$

denotes the thermal conductivity. Considering the complex couplings between fluid motion, temperature distribution and phase change in this two-dimensional problem, no analytical solution is available. Therefore, validation is performed by comparing the present results with those from previous numerical studies. Figure 3(b) shows the evolution of the

$k$

denotes the thermal conductivity. Considering the complex couplings between fluid motion, temperature distribution and phase change in this two-dimensional problem, no analytical solution is available. Therefore, validation is performed by comparing the present results with those from previous numerical studies. Figure 3(b) shows the evolution of the

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

given by the present IB–LBM, alongside results from the enthalpy-based LBM by Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Wu and Cheng2013) and the control volume method by Mencinger (Reference Mencinger2004). These three methods generally exhibit good agreement, demonstrating the accuracy of the present approach. A slight discrepancy is observed near

$\textit{Nu}$

given by the present IB–LBM, alongside results from the enthalpy-based LBM by Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Wu and Cheng2013) and the control volume method by Mencinger (Reference Mencinger2004). These three methods generally exhibit good agreement, demonstrating the accuracy of the present approach. A slight discrepancy is observed near

![]() $\textit{Fo} \approx 8.0$

, which is attributed to the inherent uncertainty and fortuity in the timing of vortex merging, as previously noted by Huang & Wu (Reference Huang and Wu2014). Furthermore, figure 3(c) compares the phase interface locations at four different Fourier numbers (

$\textit{Fo} \approx 8.0$

, which is attributed to the inherent uncertainty and fortuity in the timing of vortex merging, as previously noted by Huang & Wu (Reference Huang and Wu2014). Furthermore, figure 3(c) compares the phase interface locations at four different Fourier numbers (

![]() $\textit{Fo} = 4.0$

,

$\textit{Fo} = 4.0$

,

![]() $10.0$

,

$10.0$

,

![]() $20.0$

and

$20.0$

and

![]() $30.0$

) with those from the literature. The close agreement in interface position confirms that the present IB–LBM accurately captures the melting front in the presence of natural convection.

$30.0$

) with those from the literature. The close agreement in interface position confirms that the present IB–LBM accurately captures the melting front in the presence of natural convection.

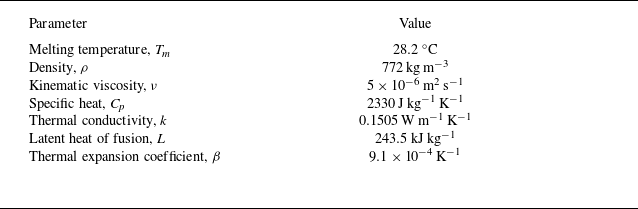

Table 1. Thermophysical properties of n-octadecane (Tan Reference Tan2008; Tan et al. Reference Tan, Hosseinizadeh, Khodadadi and Fan2009).

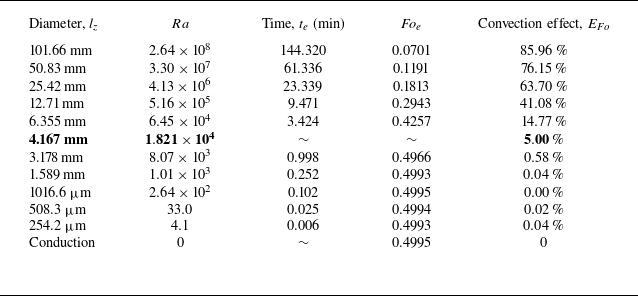

3.3. Melting in a spherical container

Lastly, to evaluate the capability of the proposed IB–LBM in simulating realistic PCM melting processes, a benchmark experiment involving a spherical PCM container is numerically reproduced and analysed under constrained melting conditions. As illustrated in figure 4(a), the experiment conducted by Tan (Reference Tan2008) consists of a spherical capsule with a diameter of

![]() $101.66\,{\rm mm}$

filled with n-octadecane PCM. Eight thermocouples (labelled A–H) are positioned along the vertical symmetry axis to monitor the internal temperature evolutions at different heights. The thermophysical properties of the PCM are summarised in table 1. Initially, the PCM is fully solidified at a uniform temperature

$101.66\,{\rm mm}$

filled with n-octadecane PCM. Eight thermocouples (labelled A–H) are positioned along the vertical symmetry axis to monitor the internal temperature evolutions at different heights. The thermophysical properties of the PCM are summarised in table 1. Initially, the PCM is fully solidified at a uniform temperature

![]() $T_0=27.2{^{\kern1.5pt\circ}{\rm C}}$

, which is one degree below the melting temperature

$T_0=27.2{^{\kern1.5pt\circ}{\rm C}}$

, which is one degree below the melting temperature

![]() $T_m=28.2^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. The melting process is initiated by suddenly raising the outer surface temperature of the capsule to a constant value of

$T_m=28.2^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. The melting process is initiated by suddenly raising the outer surface temperature of the capsule to a constant value of

![]() $T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. The corresponding dimensionless parameters for the problem are

$T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. The corresponding dimensionless parameters for the problem are

![]() $Ra = 2.64 \times 10^8$

,

$Ra = 2.64 \times 10^8$

,

![]() $\textit{Ste} = 0.13225$

and

$\textit{Ste} = 0.13225$

and

![]() $\textit{Pr} = 59.76$

.

$\textit{Pr} = 59.76$

.

Figure 4. Melting of PCM in a spherical container: (a) schematic of the spherical PCM capsule with temperature measurement points, (b) comparison of liquid fraction

![]() $f_l$

among the results of the present IB–LBM, the Fluent simulation by Tan et al. (Reference Tan, Hosseinizadeh, Khodadadi and Fan2009) and the experiment by Tan (Reference Tan2008).

$f_l$

among the results of the present IB–LBM, the Fluent simulation by Tan et al. (Reference Tan, Hosseinizadeh, Khodadadi and Fan2009) and the experiment by Tan (Reference Tan2008).

Figure 4(b) compares the liquid fraction (

![]() ${\kern-0.5pt}f_l$

) evolution predicted by the current IB–LBM with both experimental data (Tan Reference Tan2008) and numerical results obtained using the commercial Computational Fluid Dynamics software Fluent (Tan et al. Reference Tan, Hosseinizadeh, Khodadadi and Fan2009). The IB–LBM results show excellent agreement with the experimental results. Specifically, in terms of the final melting time, the Fluent simulation exhibits a relative error of

${\kern-0.5pt}f_l$

) evolution predicted by the current IB–LBM with both experimental data (Tan Reference Tan2008) and numerical results obtained using the commercial Computational Fluid Dynamics software Fluent (Tan et al. Reference Tan, Hosseinizadeh, Khodadadi and Fan2009). The IB–LBM results show excellent agreement with the experimental results. Specifically, in terms of the final melting time, the Fluent simulation exhibits a relative error of

![]() $27.9\,\%$

, while the enthalpy-based LBM reported in Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Wang, Ma, Wang and Zhang2018) reduces this error to

$27.9\,\%$

, while the enthalpy-based LBM reported in Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Wang, Ma, Wang and Zhang2018) reduces this error to

![]() $7.8\,\%$

. In contrast, the present IB–LBM achieves a remarkably lower error of only

$7.8\,\%$

. In contrast, the present IB–LBM achieves a remarkably lower error of only

![]() $0.8\,\%$

, highlighting its high accuracy and strong capability for simulating phase-change processes under high-Rayleigh-number conditions.

$0.8\,\%$

, highlighting its high accuracy and strong capability for simulating phase-change processes under high-Rayleigh-number conditions.

Figure 5. Comparison of temperature evolution at selected measurement points between the present IB–LBM, Fluent (Tan et al. Reference Tan, Hosseinizadeh, Khodadadi and Fan2009) and experimental results (Tan Reference Tan2008): (a) point A, (b) point B, (c) point D, (d) point G.

To provide further insight into the thermal behaviour, figure 5 presents temperature comparisons at four representative measurement points (i.e. A, B, D and G). Overall, the temperature predictions from the IB–LBM align more closely with experimental data. In figures 5(a) and 5(b), temperature profiles at points A and B (located near the bottom of the capsule) exhibit strong fluctuations during the melting process. This is attributed to the formation of a thermally unstable fluid layer. Specifically, the bottom surface of the capsule is maintained at the hot boundary temperature

![]() $T_b$

, while cooler liquid PCM accumulates above. This unstable stratification triggers strong natural convection, resulting in chaotic temperature variations. Similar convection-induced oscillations have also been reported by Duan, Hosseinizadeh & Khodadadi (Reference Duan, Hosseinizadeh and Khodadadi2007). In contrast, as shown in figure 5(c) and 5(d), temperature profiles at points D and G (located higher in the capsule) are smoother and exhibit good agreement with the experimental data. These points reside within thermally stable layers, where the warmer fluid overlays cooler fluid, suppressing convective mixing and stabilising the temperature field. The temperature responses at the remaining measurement points follow similar trends, corresponding to either thermally unstable or stable layers, and are therefore omitted here.

$T_b$

, while cooler liquid PCM accumulates above. This unstable stratification triggers strong natural convection, resulting in chaotic temperature variations. Similar convection-induced oscillations have also been reported by Duan, Hosseinizadeh & Khodadadi (Reference Duan, Hosseinizadeh and Khodadadi2007). In contrast, as shown in figure 5(c) and 5(d), temperature profiles at points D and G (located higher in the capsule) are smoother and exhibit good agreement with the experimental data. These points reside within thermally stable layers, where the warmer fluid overlays cooler fluid, suppressing convective mixing and stabilising the temperature field. The temperature responses at the remaining measurement points follow similar trends, corresponding to either thermally unstable or stable layers, and are therefore omitted here.

4. Results and discussion

In this section, the constrained melting behaviour of the encapsulated PCM is investigated using the proposed IB–LBM model. The simulation set-up follows the experimental configuration shown in figure 4(a), with a capsule diameter of

![]() $l_z$

and a boundary temperature of

$l_z$

and a boundary temperature of

![]() $T_b$

. Initially, the PCM is uniformly sub-cooled by

$T_b$

. Initially, the PCM is uniformly sub-cooled by

![]() $\Delta T_s$

below the melting point. To ensure consistency with the experimental set-up, the thermophysical properties are listed in table 1. In lattice units, the lattice spacing

$\Delta T_s$

below the melting point. To ensure consistency with the experimental set-up, the thermophysical properties are listed in table 1. In lattice units, the lattice spacing

![]() $\delta _x$

and time step

$\delta _x$

and time step

![]() $\delta _t$

are both set to

$\delta _t$

are both set to

![]() $1.0$

, resulting in the lattice speed of

$1.0$

, resulting in the lattice speed of

![]() $c = \delta _x / \delta _t = 1.0$

. The lattice speed is kept at unity even when the grid size changes in the grid convergence test. The kinematic viscosity and thermal diffusivity are specified as

$c = \delta _x / \delta _t = 1.0$

. The lattice speed is kept at unity even when the grid size changes in the grid convergence test. The kinematic viscosity and thermal diffusivity are specified as

![]() $4.3 \times 10^{-2}$

and

$4.3 \times 10^{-2}$

and

![]() $7.2 \times 10^{-4}$

, respectively, to match the Prandtl number.

$7.2 \times 10^{-4}$

, respectively, to match the Prandtl number.

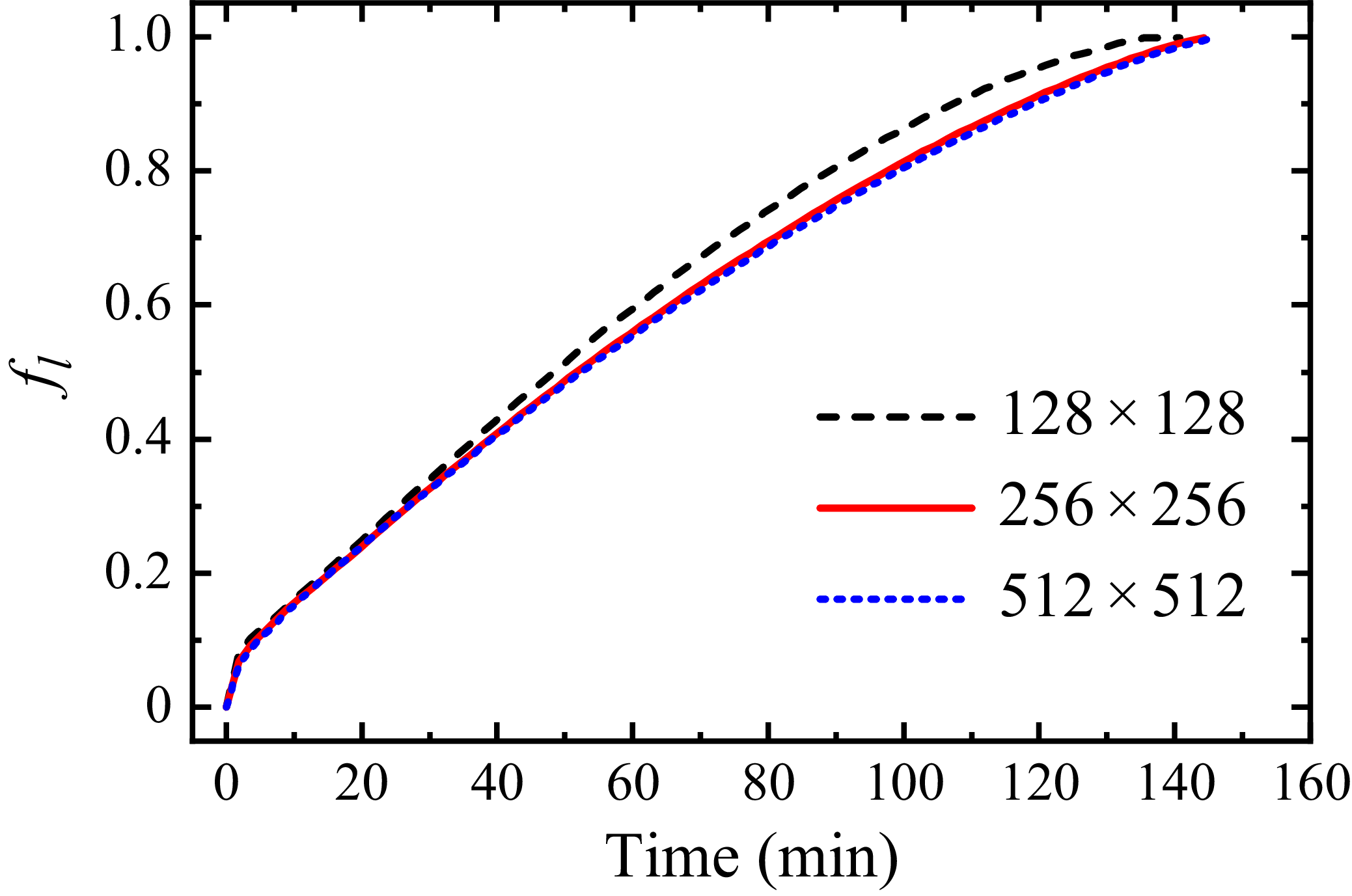

Before proceeding with the main simulations, a grid convergence test is conducted to ensure the selected grid resolution is sufficiently fine. Three grids resolutions are evaluated,

![]() $128 \times 128$

,

$128 \times 128$

,

![]() $256 \times 256$

and

$256 \times 256$

and

![]() $512 \times 512$

. Figure 6 demonstrates the temporal evolution of liquid fraction

$512 \times 512$

. Figure 6 demonstrates the temporal evolution of liquid fraction

![]() $f_l$

for each grid case. The

$f_l$

for each grid case. The

![]() $128 \times 128$

grid slightly overpredicts the melting rate, while results from the

$128 \times 128$

grid slightly overpredicts the melting rate, while results from the

![]() $256 \times 256$

and

$256 \times 256$

and

![]() $512 \times 512$

grids are nearly identical, indicating convergence. Therefore, the

$512 \times 512$

grids are nearly identical, indicating convergence. Therefore, the

![]() $256 \times 256$

grid is adopted for all subsequent simulations to balance numerical accuracy and computational efficiency.

$256 \times 256$

grid is adopted for all subsequent simulations to balance numerical accuracy and computational efficiency.

Figure 6. Temporal evolutions of liquid fraction

![]() $f_l$

for different grid sizes.

$f_l$

for different grid sizes.

4.1. Melting properties

To investigate the general melting behaviours of PCM under constrained conditions, a base case is first simulated with a capsule diameter of

![]() $l_z = 101.66\,{\rm mm}$

, a boundary temperature of

$l_z = 101.66\,{\rm mm}$

, a boundary temperature of

![]() $T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

and a subcooling of

$T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

and a subcooling of

![]() $\Delta T_s = 1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. Figure 7 presents the streamlines (left half) and temperature contours (right half) within the capsule at selected time instants ranging from 0 to 140 minutes. At each time instant, the phase-change interface is indicated by a red dashed line, while the capsule and PCM centres are marked by black and red dots, respectively. At the initial stage (

$\Delta T_s = 1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. Figure 7 presents the streamlines (left half) and temperature contours (right half) within the capsule at selected time instants ranging from 0 to 140 minutes. At each time instant, the phase-change interface is indicated by a red dashed line, while the capsule and PCM centres are marked by black and red dots, respectively. At the initial stage (

![]() $0$

–

$0$

–

![]() $20\,\rm{min}$

), the solid PCM generally remains in direct contact with the heated capsule wall and heat transfer is therefore dominated by conduction. A thin liquid layer begins to form along the inner surface during this period, but the bulk of the PCM retains a nearly circular solid shape. As time progresses (

$20\,\rm{min}$

), the solid PCM generally remains in direct contact with the heated capsule wall and heat transfer is therefore dominated by conduction. A thin liquid layer begins to form along the inner surface during this period, but the bulk of the PCM retains a nearly circular solid shape. As time progresses (

![]() $40$

–

$40$

–

![]() $100\,\rm{min}$

), the liquid layer continues to thicken, reducing the dominance of heat conduction and promoting the onset of natural convection. In the upper region of the capsule, the heated wall is located above the liquid layer, causing warmer liquid to overlay cooler liquid. This forms a thermally stable liquid layer, which suppresses convection. In contrast, the lower region becomes thermally unstable because the heated wall lies beneath the liquid layer, promoting buoyancy-driven flow and intensifying natural convection. This thermal stratification results in a distinct melting pattern: the upper part of the solid PCM exhibits an oval-shaped melting front, while the lower part shows surface waviness caused by vigorous convection. The fluid motion during this period follows a characteristic natural convection pattern, where warm liquid rises along the heated wall, and cooler liquid descends through the central region. This circulation enhances the accumulation of hot liquid in the upper region, causing it to melt significantly faster than the lower region. At later times (

$100\,\rm{min}$

), the liquid layer continues to thicken, reducing the dominance of heat conduction and promoting the onset of natural convection. In the upper region of the capsule, the heated wall is located above the liquid layer, causing warmer liquid to overlay cooler liquid. This forms a thermally stable liquid layer, which suppresses convection. In contrast, the lower region becomes thermally unstable because the heated wall lies beneath the liquid layer, promoting buoyancy-driven flow and intensifying natural convection. This thermal stratification results in a distinct melting pattern: the upper part of the solid PCM exhibits an oval-shaped melting front, while the lower part shows surface waviness caused by vigorous convection. The fluid motion during this period follows a characteristic natural convection pattern, where warm liquid rises along the heated wall, and cooler liquid descends through the central region. This circulation enhances the accumulation of hot liquid in the upper region, causing it to melt significantly faster than the lower region. At later times (

![]() $100$

–

$100$

–

![]() $140\,\rm{min}$

), due to the faster melting in the upper region, the centre of the remaining solid PCM, which is indicated by a red point, gradually shifts below the geometric centre of the capsule, point E. In addition, the melting front evolves into a dome-shaped structure, characterised by concave-down surfaces. As the solid PCM continues to melt and its volume decreases, natural convection becomes the dominant heat transfer mechanism.

$140\,\rm{min}$

), due to the faster melting in the upper region, the centre of the remaining solid PCM, which is indicated by a red point, gradually shifts below the geometric centre of the capsule, point E. In addition, the melting front evolves into a dome-shaped structure, characterised by concave-down surfaces. As the solid PCM continues to melt and its volume decreases, natural convection becomes the dominant heat transfer mechanism.

Figure 7. Streamlines (left) and temperature contours (right) within the capsule for the base case with boundary temperature

![]() $T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, capsule size

$T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, capsule size

![]() $l_z = 101.66\, {\rm mm}$

and sub-cooling

$l_z = 101.66\, {\rm mm}$

and sub-cooling

![]() $\Delta T_s = 1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

at selected time instants from 0 to 140 min. The red dash line indicates the melting front. The centre point (E) of the capsule is indicated by a black point, while a red point represents the location of the solid PCM centre.

$\Delta T_s = 1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

at selected time instants from 0 to 140 min. The red dash line indicates the melting front. The centre point (E) of the capsule is indicated by a black point, while a red point represents the location of the solid PCM centre.

To quantify the melting behaviour, temporal evolutions of the liquid volume fraction

![]() $f_l$

are recorded in figure 8(a). To better illustrate the variation in the initial melting rate, a magnified view of the region for

$f_l$

are recorded in figure 8(a). To better illustrate the variation in the initial melting rate, a magnified view of the region for

![]() $t \leq 10\,\rm{min}$

is also shown. At the initial stage (

$t \leq 10\,\rm{min}$

is also shown. At the initial stage (

![]() $t \leq 2\,\rm{min}$

), the melting rate is high, as indicated by the steep slope of the curve. This is attributed to the effective conduction from the heated wall to the adjacent solid PCM. However, as the liquid layer thickens, the melting rate drops sharply due to increasing thermal resistance. The point at which the melting rate begins to decline rapidly is indicated by a black dot. Interestingly, the rate does not continue to decrease in the later stages, but instead remains nearly steady as indicated by a light blue area, which is driven by enhanced convective heat transfer. Figure 8(b) further illustrates the spatial evolution of the melting front along three angular directions: rightward (horizontal), upward (vertical top) and downward (vertical bottom). The schematic illustration of the radial positions in three directions is also provided, denoted as

$t \leq 2\,\rm{min}$

), the melting rate is high, as indicated by the steep slope of the curve. This is attributed to the effective conduction from the heated wall to the adjacent solid PCM. However, as the liquid layer thickens, the melting rate drops sharply due to increasing thermal resistance. The point at which the melting rate begins to decline rapidly is indicated by a black dot. Interestingly, the rate does not continue to decrease in the later stages, but instead remains nearly steady as indicated by a light blue area, which is driven by enhanced convective heat transfer. Figure 8(b) further illustrates the spatial evolution of the melting front along three angular directions: rightward (horizontal), upward (vertical top) and downward (vertical bottom). The schematic illustration of the radial positions in three directions is also provided, denoted as

![]() $r_r$

,

$r_r$

,

![]() $r_u$

and

$r_u$

and

![]() $r_d$

for the rightward, upward and downward directions, respectively. Among these directions, the upward side exhibits the fastest melting rate, consistent with the accumulation of warmer fluid at the top due to natural convection. Between the downward and rightward directions, the downward side initially melts faster (before

$r_d$

for the rightward, upward and downward directions, respectively. Among these directions, the upward side exhibits the fastest melting rate, consistent with the accumulation of warmer fluid at the top due to natural convection. Between the downward and rightward directions, the downward side initially melts faster (before

![]() $100\,\rm{min}$

) because of the strong convective flows in the thermally unstable lower layer. However, in the later stage, the melting rate in the rightward direction surpasses that of the downward side. This is because the remaining solid PCM has shifted downward, leaving less material near the rightward direction, while residual unmelted PCM remains at the bottom. As shown in figure 7 at

$100\,\rm{min}$

) because of the strong convective flows in the thermally unstable lower layer. However, in the later stage, the melting rate in the rightward direction surpasses that of the downward side. This is because the remaining solid PCM has shifted downward, leaving less material near the rightward direction, while residual unmelted PCM remains at the bottom. As shown in figure 7 at

![]() $140\,\rm{min}$

, when the centre of the solid PCM (red dot) lies below the centre of the capsule (black dot), the rightward and upward radial locations fall outside the solid domain and thus yield no data. This explains why the radial locations of rightward and upward directions drop to zero before the PCM is fully melted, whereas the downward radial location still has a value of approximately

$140\,\rm{min}$

, when the centre of the solid PCM (red dot) lies below the centre of the capsule (black dot), the rightward and upward radial locations fall outside the solid domain and thus yield no data. This explains why the radial locations of rightward and upward directions drop to zero before the PCM is fully melted, whereas the downward radial location still has a value of approximately

![]() $0.2$

until complete melting.

$0.2$

until complete melting.

Figure 8. Results of constrained melting for boundary temperature

![]() $T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, capsule size

$T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, capsule size

![]() $l_z = 101.66\, {\rm mm}$

and subcooling

$l_z = 101.66\, {\rm mm}$

and subcooling

![]() $\Delta T_s =1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. Temporal evolutions of (a) liquid volume fraction

$\Delta T_s =1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. Temporal evolutions of (a) liquid volume fraction

![]() $f_l$

and (b) normalised radial position of the phase interface in different directions.

$f_l$

and (b) normalised radial position of the phase interface in different directions.

Figure 9. Temperature results of constrained melting for

![]() $T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, capsule size

$T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, capsule size

![]() $l_z = 101.66\,{\rm mm}$

and subcooling

$l_z = 101.66\,{\rm mm}$

and subcooling

![]() $\Delta T_s=1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

: (a) temperature evolutions at different locations inside the capsule and (b) temperature contour at 100 min with different melting states marked.

$\Delta T_s=1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

: (a) temperature evolutions at different locations inside the capsule and (b) temperature contour at 100 min with different melting states marked.

To better understand the internal thermal behaviour, temperature evolutions at multiple monitoring points are presented in figure 9(a), with their locations indicated in figure 4(a). The time span shown in figure 9(a) extends slightly beyond the complete melting time, covering an additional period during which the PCM is fully melted. The temperature profiles exhibit similar trends across all points and can be generally divided into three distinct states: solid (state 1), phase change (state 2) and liquid (state 3), corresponding to approximate temperature ranges of below

![]() $28.2^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

,

$28.2^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

,

![]() $28.2{-}32^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

and

$28.2{-}32^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

and

![]() $32{-}40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, respectively. In state 1, the temperature remains nearly constant at around

$32{-}40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, respectively. In state 1, the temperature remains nearly constant at around

![]() $27.2{-}28.2^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. This reflects the dominance of solid-phase conditions in which low thermal conductivity and latent heat absorption limit temperature variations. As the points enter state 2, the onset of melting triggers a rapid temperature rise, driven by intensified convective heat transfer from the surrounding liquid. In the final state 3, after complete melting, the local temperature asymptotically approaches the boundary temperature of approximately

$27.2{-}28.2^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. This reflects the dominance of solid-phase conditions in which low thermal conductivity and latent heat absorption limit temperature variations. As the points enter state 2, the onset of melting triggers a rapid temperature rise, driven by intensified convective heat transfer from the surrounding liquid. In the final state 3, after complete melting, the local temperature asymptotically approaches the boundary temperature of approximately

![]() $40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. The transition points between states are marked by symbols in figure 9(a). To clearly illustrate different melting states among the points, figure 9(b) presents the temperature contour at

$40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. The transition points between states are marked by symbols in figure 9(a). To clearly illustrate different melting states among the points, figure 9(b) presents the temperature contour at

![]() $t = 100 \,\rm{min}$

. At this moment, points D and E remain within the solid PCM and are therefore classified as state 1. In contrast, points C and F lie close to the solid–liquid interface, where sharp temperature gradients are observed, corresponding to state 2. Meanwhile, points A, B, G, and H are in the fully melted region and are accordingly categorised as state 3.

$t = 100 \,\rm{min}$

. At this moment, points D and E remain within the solid PCM and are therefore classified as state 1. In contrast, points C and F lie close to the solid–liquid interface, where sharp temperature gradients are observed, corresponding to state 2. Meanwhile, points A, B, G, and H are in the fully melted region and are accordingly categorised as state 3.

Despite the similar temperature profile patterns, spatial differences are evident. Points located near the top of the capsule (e.g. H, G, F) enter the melting state earlier than their vertically symmetric counterparts near the bottom (e.g. B, C, D). This confirms the upward accumulation of warmer fluid due to natural convection, which accelerates melting in the upper region (see figure 7). In addition, during the melting state 2, the temperature generally varies within the range of

![]() $28.2{-}40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. However, for points near the bottom boundary (i.e. A, B and C), the temperature remains within

$28.2{-}40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

. However, for points near the bottom boundary (i.e. A, B and C), the temperature remains within

![]() $28.2{-}32^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

before entering state 3. Again, this phenomenon arises from strong natural convection, which promotes the accumulation of hot liquid in the top region while maintaining cold liquid in the bottom region. Such a vertical asymmetry is also evident in the final liquid state, where upper points quickly reach the boundary temperature, while lower points approach it more gradually. Notably, point D, located just below the central point E, is the last to undergo melting, further supporting the observation that the remaining solid PCM tends to shift downward over time.

$28.2{-}32^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

before entering state 3. Again, this phenomenon arises from strong natural convection, which promotes the accumulation of hot liquid in the top region while maintaining cold liquid in the bottom region. Such a vertical asymmetry is also evident in the final liquid state, where upper points quickly reach the boundary temperature, while lower points approach it more gradually. Notably, point D, located just below the central point E, is the last to undergo melting, further supporting the observation that the remaining solid PCM tends to shift downward over time.

4.2. Effects of boundary temperature and subcooling

In this section, the effects of boundary temperature

![]() $T_b$

and initial subcooling

$T_b$

and initial subcooling

![]() $\Delta T_s$

on the constrained melting process are investigated. At a fixed capsule diameter of

$\Delta T_s$

on the constrained melting process are investigated. At a fixed capsule diameter of

![]() $l_z = 101.66\,{\rm mm}$

, two sets of parametric studies are carried out: one with varying

$l_z = 101.66\,{\rm mm}$

, two sets of parametric studies are carried out: one with varying

![]() $T_b$

from

$T_b$

from

![]() $35^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

to

$35^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

to

![]() $60^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

at a constant

$60^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

at a constant

![]() $\Delta T_s = 1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, and the other with

$\Delta T_s = 1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, and the other with

![]() $\Delta T_s$

ranging from

$\Delta T_s$

ranging from

![]() $1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

to

$1^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

to

![]() $20^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

at

$20^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

at

![]() $T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

.

$T_b = 40^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

.

Figure 10(a) presents the temporal evolution of liquid fraction

![]() $f_l$

for various boundary temperatures. It is evident that a higher

$f_l$

for various boundary temperatures. It is evident that a higher

![]() $T_b$

significantly reduces the total melting time. For example, when

$T_b$

significantly reduces the total melting time. For example, when

![]() $T_b$

is

$T_b$

is

![]() $35^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, the complete melting occurs at approximately 265 minutes. As

$35^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, the complete melting occurs at approximately 265 minutes. As

![]() $T_b$

increases to

$T_b$

increases to

![]() $60^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, the total melting time progressively decreases, reaching as low as 45 minutes. To further investigate the melting behaviour, figure 10(b) plots the instantaneous melting rate against the liquid fraction. A sharp initial peak is observed, corresponding to heat conduction dominating in the early stage. As the liquid layer thickens, the conduction effect diminishes and the melting rate drops accordingly. After the liquid fraction reaches approximately 0.1, the melting rate is relatively steady due to enhanced convective mixing. The averaged melting rate at this stage is calculated for different

$60^{\kern1.5pt\circ }{\rm C}$

, the total melting time progressively decreases, reaching as low as 45 minutes. To further investigate the melting behaviour, figure 10(b) plots the instantaneous melting rate against the liquid fraction. A sharp initial peak is observed, corresponding to heat conduction dominating in the early stage. As the liquid layer thickens, the conduction effect diminishes and the melting rate drops accordingly. After the liquid fraction reaches approximately 0.1, the melting rate is relatively steady due to enhanced convective mixing. The averaged melting rate at this stage is calculated for different

![]() $T_b$

cases and summarised in figure 10(c). It is evident that a higher

$T_b$

cases and summarised in figure 10(c). It is evident that a higher

![]() $T_b$

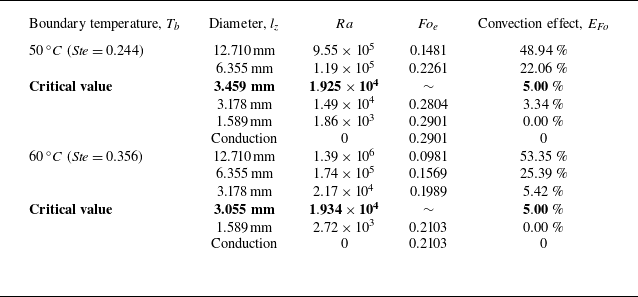

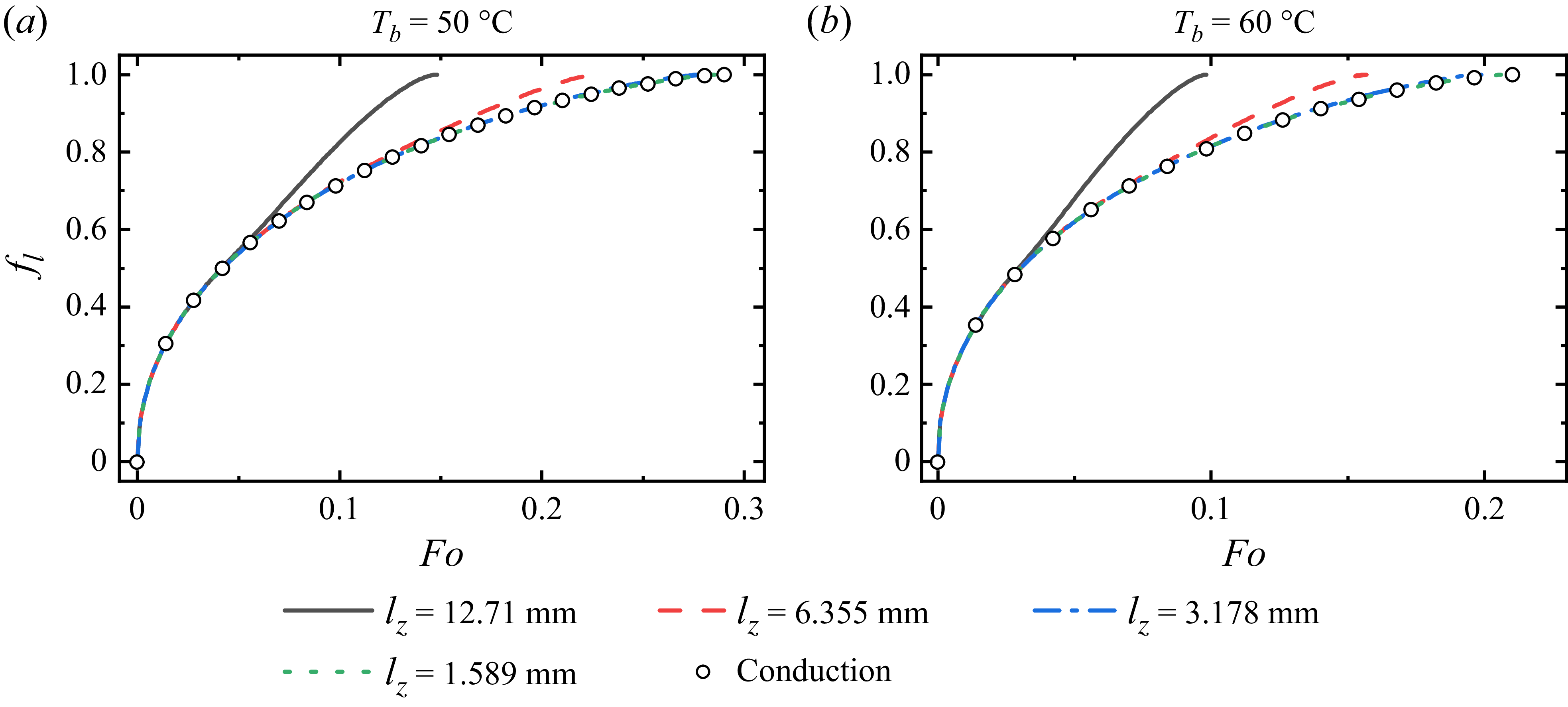

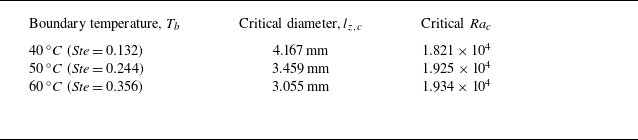

consistently yields a higher melting rate. This outcome is attributed to the increases in both