Introduction

The grandparent role offers a positive, generative identity in later life (Arber and Timonen Reference Arber and Timonen2012). Grandparent–grandchild relationships have received considerable research attention since the 1980s (Kahana et al. Reference Kahana, Kahana, Goler, Kahana, Hayslip and Fruhauf2019), with much research focusing on intergenerational exchange and interactions, through the theoretical lens of intergenerational solidarity (Duflos and Giraudeau Reference Duflos and Giraudeau2021). This form of solidarity is understood as reciprocal and multidimensional, involving instrumental and symbolic exchanges, but affectual solidarity – involving emotional closeness – is the most studied dimension (Duflos and Giraudeau Reference Duflos and Giraudeau2021). A systematic review of emotional closeness between grandparents and adolescent or young adult grandchildren (Duflos et al. Reference Duflos, Giraudeau and Ferrand2022) highlights the quantitative focus of this research, and the need for more nuanced understandings of how grandparents and grandchildren experience their relationship, in its own right and in the context of broader family interactions.

Within studies of grandparenthood, grandparents’ care for their grandchildren is the dominant area of inquiry (Duflos and Giraudeau Reference Duflos and Giraudeau2021). Considerable international evidence indicates that grandparents often provide material, practical, moral and emotional support to parents and grandchildren (Craig and Jenkins Reference Craig and Jenkins2016; Grünwald et al. Reference Grünwald, Damman and Henkens2022; Kastarinen et al. Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023).

There is growing evidence of grandchildren offering practical as well as emotional support for grandparents who have become frail or ill (Hamill Reference Hamill2012; Venters and Jones Reference Venters and Jones2021). Beyond these situations, however, a recent review of research on grandparent–grandchild relations argues that insufficient attention has been paid to the many ways that non-adult grandchildren ‘serve as resources to their grandparents’ (Kahana et al. Reference Kahana, Kahana, Goler, Kahana, Hayslip and Fruhauf2019: 73). Furthermore, relatively little is known about grandparents’ experiences of receiving support from their grandchildren, particularly in situations where they do not need practical help with daily living.

This article, then, aims to answer the call for more qualitative studies, offering more nuanced understandings of experiences and feelings involved in grandparent–grandchild relationships (Duflos and Giraudeau Reference Duflos and Giraudeau2021) and for greater understanding of grandchildren’s contributions to the grandparent–grandchild relationship (Kahana et al. Reference Kahana, Kahana, Goler, Kahana, Hayslip and Fruhauf2019). Exploring how grandparents experience upward flows of support from their grandchildren, it ventures beyond measuring individual dimensions of support or solidarity, employing instead the holistic theoretical lens of care (Tronto Reference Tronto1993). It seeks to add further nuance to this lens by drawing on theories concerning the circulation of care within families (Baldassar and Merla Reference Baldassar, Merla, Baldassar and Merla2014), intergenerational caring through consumption (Kastarinen et al. Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023) and the mundane materialities of care, not least within families (Buse et al. Reference Buse, Martin and Nettleton2018; Lindsay and Maher Reference Lindsay and Maher2013).

Focusing on the Covid-19 pandemic which disrupted taken-for-granted aspects of family life (Eldén et al. Reference Eldén, Anving and Wallin2022; Vanderhout et al. Reference Vanderhout, Birken, Wong, Kelleher, Weir and Maguire2020), this article addresses two research questions: how did grandparents experience receiving care from grandchildren during the pandemic, and how were consumption practices bound up with those experiences? It seeks to answer these questions by drawing on a wider consumer culture study of grandparenting and the circulation of care, undertaken during the early stages of the pandemic. The study involved semi-structured interviews with 30 grandparents living in Scotland or Denmark, locations offering distinctive regulatory and cultural contexts, shaping different patterns of grandparent–grandchild interactions in ‘normal’ and exceptional circumstances (OECD 2024; Olagnier and Mogensen Reference Olagnier and Mogensen2020; SPICe 2023).

Beyond offering further insights into older peoples’ experiences of the pandemic, this study highlights the range of grandchild caring practices – many involving mundane, taken-for-granted consumer goods and services including food and communications technology – and their particular contribution to grandparents’ wellbeing. In these ways, this article contributes to a richer, contextualized understanding of the social bond between grandparents and grandchildren (Klein Reference Klein2022) and how flows of care from grandchildren to grandparents contribute to grandparental wellbeing. These insights could help families, health and social care professionals, and policy makers understand better how younger generations can contribute to the care and wellbeing of older people.

Before presenting methodological details and key findings, this article reviews prior literature regarding grandparents in contemporary family life; grandchildren’s support for grandparents; the impact of the pandemic on grandparenting relationships; and conceptualizations of care, including those incorporating consumption.

Literature review

Grandparenting roles, relationships and family life

In recent decades, grandparents’ place in family life has received increasing attention from scholars and policy makers (Arber and Timonen Reference Arber and Timonen2012; Backhaus and Barslund Reference Backhaus and Barslund2019; Timonen Reference Timonen2020). International studies highlight important differences in intergenerational cohabitation and the intensity of grandparental involvement in rearing children (Dolbin-MacNab and Yancura Reference Dolbin-MacNab and Yancura2018; Etten Reference Etten1995). Grandparent–grandchild relationships also vary according to wider family dynamics, geographic closeness and the health, needs and resources of each generation (Arber and Timonen Reference Arber and Timonen2012; Herlofson and Hagestad Reference Herlofson, Hagestad, Arber and Timonen2012; Timonen Reference Timonen2020). These relationships change over time and vary between individuals, even within the same family (Fingerman Reference Fingerman1998; Ross et al. Reference Ross, Hill, Sweeting and Cunningham-Burley2005; Sciplino and Kinshott Reference Sciplino and Kinshott2019), and are shaped by ‘gendered conceptions of care’ (Marhánková and Štípková Reference Marhánková and Štípková2015: 932), though perhaps less than in the past: studies in the United Kingdom (UK), for example, document how divorce, separation, remarriage and repartnering reconfigure intergenerational relations (Jamieson et al. Reference Jamieson, Ribe and Warner2018; Ross et al. Reference Ross, Hill, Sweeting and Cunningham-Burley2005) and how grandfathers increasingly describe close emotional bonds and involvement with grandchildren (Buchanan Reference Buchanan, Shwalb and Hossain2018; Mann et al. Reference Mann, Tarrant and Leeson2016).

Overall, in Western societies, longer, healthier lifespans, smaller families and greater participation of both parents in the workforce have woven grandparents more deeply into the fabric of everyday family life (Marhánková Reference Marhánková2015). Grandparents often provide various forms of support to their children and grandchildren (Arber and Timonen Reference Arber and Timonen2012; Kastarinen et al. Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023) and play multiple roles in their grandchildren’s lives, including nurturers, kin-keepers, value transmitters, playmates, mentors, confidants, protectors and mediators (Moore and Rosenthal Reference Moore and Rosenthal2017; Ross et al. Reference Ross, Hill, Sweeting and Cunningham-Burley2005). Many grandparents – particularly grandmothers – provide regular informal childcare when both parents are working, especially where there is limited state funding of formal childcare (Bordone et al. Reference Bordone, Arpino and Aassve2016; Glaser et al. Reference Glaser, Price, Di Gessa, Ribe, Stuchbury and Tinker2013).

Providing childcare often entails expenditure on various consumer goods and services: 83 per cent of UK grandparents who looked after their grandchildren regularly spent up to £50 per month on goods and services for their grandchildren (Holley-Moore Reference Holley-Moore2017), while Danish and New Zealand grandparents treated grandchildren to special foods, café and restaurant visits, days out and even holidays (Gram et al. Reference Gram, O’Donohoe, Schänzel, Marchant and Kastarinen2019; O’Donohoe et al. Reference O’Donohoe, Gram, Marchant, Schänzel and Kastarinen2021).

Although grandparents report intergenerational tensions, including the paradoxical requirement of ‘being there, without interfering’ (Breheny et al. Reference Breheny, Stephens and Spilsbury2013; May et al. Reference May, Mason, Clarke, Arber and Timonen2012), positive relationships with grandchildren contribute to their wellbeing by offering joy and fun, validation, companionship, satisfaction and generational continuity (Duflos and Giraudeau Reference Duflos and Giraudeau2021; Klein Reference Klein2022; Mansson Reference Mansson2016).

Grandchildren as providers of care

The intergenerational solidarity framework sees support and emotional closeness as flowing in both directions, not least over time (Duflos and Giraudeau Reference Duflos and Giraudeau2021; Duflos et al. Reference Duflos, Giraudeau and Ferrand2022; Sciplino and Kinshott Reference Sciplino and Kinshott2019). Less attention has been paid, however, to the many ordinary ways that non-adult grandchildren’s interactions with grandparents contribute to the relationship (Kahana et al. Reference Kahana, Kahana, Goler, Kahana, Hayslip and Fruhauf2019). This may reflect Western cultures’ construction of childhood as a special, protected life stage (Becker Reference Becker2007). Thus, children’s care-giving is often downplayed using the language of ‘chores’ or ‘help’, or framed as an exceptional ‘burden’ in families facing challenges (García-Sánchez Reference García-Sánchez2018). In this context, several UK and Danish studies highlight the strain on under-18-year-olds undertaking ‘substantial, regular and significant’ tasks for family members including grandparents (Becker Reference Becker2007; Wind and Jorgensen Reference Wind and Jorgensen2020). There is growing international evidence of grandchildren, ranging in age from 8 to 40, forming part of the ‘the constellation of caregivers in the family system’ (Hamill Reference Hamill2012: 1208) when grandparents become ill or frail, particularly with dementia. Many studies report grandchildren helping, to a greater or lesser extent, with care-giving for vulnerable grandparents, including housework, meal preparation, travel, walking, intimate tasks around eating and personal care, and support with money or medication (Berenbaum et al. Reference Berenbaum, Miller, Shapiro and Tziraki2024; D’Amen et al. Reference D’Amen, Socci and Santini2021; Hamill Reference Hamill2012; Venters and Jones Reference Venters and Jones2021).

More generally, studies have pointed to grandchildren discharging their ‘grandfilial responsibility’ (Brody et al. Reference Brody, Litvin, Hoffman and Kleban1995) in various ways, including spending time with grandparents; listening to them; showing respect; ‘giving back’ by making grandparents proud; helping with chores; encouraging healthier eating, social participation or open-mindedness; and introducing them to new technologies (Keck and Saraceno Reference Keck, Saraceno, Leira and Saraceno2008; Kemp Reference Kemp2004; Matos and Neves Reference Matos, Neves, Arber and Timonen2012). Several studies highlight how grandchildren offering support see themselves not only as responding to a grandparental need but also as reciprocating and expressing gratitude for the care previously shown to them by their grandparents (Kahana et al. Reference Kahana, Kahana, Goler, Kahana, Hayslip and Fruhauf2019). Although many grandchildren found it satisfying to help, providing intense support could affect their own mental health, social lives, careers or relationships (Fruhauf et al. Reference Fruhauf, Jarrott and Allen2006; Venters and Jones Reference Venters and Jones2021). Less is known, however, about grandparents’ experiences of receiving support from grandchildren (Lowenstein Reference Lowenstein2007).

The impact of Covid-19 on grandparenting relationships

As Covid-19 spread, it became clear that risks of death and severe illness increased with age (Crimmins Reference Crimmins2020). Although restrictions were framed as shielding vulnerable populations, enforced isolation and reduced social support challenged older people’s mental health and wellbeing (Age Reference Age2020, Reference Age2021) and older people were subjected to othering discourses around vulnerability, burdens, blame and expendability (Cohn-Schwartz and Ayalon Reference Cohn-Schwartz and Ayalon2021; Jimenez-Sotomayor et al. Reference Jimenez-Sotomayor, Gomez-Moreno and Soto-Perez-de-Celis2020; Rosen Reference Rosen2021). Negative stereotypes of ageing added psychological and emotional stress at this time (Gallistl et al. Reference Gallistl, Richter, Heidinger, Schütz, Rohner, Hengl and Kolland2022), but, as Beckman and Gustavsson (Reference Beckman and Gustavsson2025) found, older adults also demonstrated considerable resilience over this period.

Grandparents faced distinctive challenges during the pandemic. Even in normal times, grandparenting has finite, poignant dimensions, requiring some reckoning with mortality and declining health, energy or grandchildren’s enthusiasm for time together (Gram et al. Reference Gram, O’Donohoe, Schänzel, Marchant and Kastarinen2019), and this is likely to have compounded the pain of enforced separation. For grandparents raising grandchildren in already stressful circumstances, the pandemic exacerbated these (Zakari et al. Reference Zakari, Hamadi, Bailey and Jibreel2022). Other grandparents were distressed at not being able to help with childcare (Derrer-Merk et al. Reference Derrer-Merk, Ferson, Mannis, Bentall and Bennett2022; Di Gessa et al. Reference Di Gessa, Bordone and Arpino2023), although many grandparents offered support in other ways, including remote help with home schooling, sending gifts or listening empathetically on calls to grandchildren missing their friends, freedom and routines (Derrer-Merk et al. Reference Derrer-Merk, Ferson, Mannis, Bentall and Bennett2022; Eldén et al. Reference Eldén, Anving and Wallin2022).

Media reports describe grandchildren seeking to raise their grandparents’ spirits during the pandemic, for example by setting up virtual dance parties (Yurieff Reference Yurieff2020), singing happy birthday or even announcing an engagement outside their grandparents’ residences (O’Malley Reference O’Malley2020). Academic studies refer to a care-giver of parents with dementia stating that her husband and sons would step in to help if she could not (Cipolletta et al. Reference Cipolletta, Morandini and Tomaino2023), and university students making more frequent calls to grandparents during the pandemic (McDarby et al. Reference McDarby, Ju and Carpenter2021). A study of videos in English, Dutch, French, Spanish and German, uploaded by grandparents and grandchildren on TikTok, describes (mainly teenage) grandchildren hugging grandparents through a plastic wall, arranging for a band to play outside their window and dropping off food or other gifts (Nouwen and Duflos Reference Nouwen and Duflos2021). Framing such actions as examples of intergenerational solidarity, these studies do not examine how they were experienced by grandparents. To explore these issues further, a more detailed understanding of care is required.

Conceptualizing care

Mayeroff’s (Reference Mayeroff1971) landmark text argued that caring cannot be reduced to ‘wishing well, liking, comforting and maintaining, or simply having an interest in what happens to another … nor is it simply a matter of wanting to care for some person’ (p. 1). Instead, he viewed caring as a process, a way of relating to another who needs and trusts us.

The 1980s saw increasing interdisciplinary interest in the concept, often drawing on a relational, context-specific ethic of care perspective informed by feminist scholarship (Sander-Staudt Reference Sander-Staudt, Fieser and Dowden2011; Shaw et al. Reference Shaw, McMaster, Longo and Özçaglar-Toulouse2017). Tronto’s (Reference Tronto1993, Reference Tronto1998) typology of interrelated caring practices has been particularly influential. Her framework involved caring about (noticing someone’s needs), caring for (taking on responsibility to meet the needs identified), care-giving (concrete care practices) and care receiving (accepting the moral burden of responsiveness). For Tronto (Reference Tronto1993: 105) care is ‘both a practice and a disposition’, underpinned by relations of trust and solidarity. This conceptualization is ‘looser’ and more inclusive than can be captured by specific activities such as instrumental, socio-emotional or domestic support, or the division of care into emotional and labour components (Eldén Reference Eldén2016; Eldén et al. Reference Eldén, Anving and Wallin2024; Inthorn Reference Inthorn2018).

Relating this perspective to childhood, Eldén (Reference Eldén2016) refers to ‘ordinary complexities of care’, highlighting the taken-for-granted nature of ‘doing’ care as part of children’s everyday experiences and relationships, and the complexity of the practices and emotions involved. Interviewing Swedish grandchildren, Eldén et al. (Reference Eldén, Anving and Wallin2024) found that those born between 2001 and 2015 saw themselves as ‘doing’ care for their grandparents, practically, relationally and emotionally. Thus, while they may help with chores like gardening, cooking or shopping, they also saw just ‘being there with them’ as a form of help. One child even reflected that leaving material traces like paintings in her grandparents’ home was a form of ‘help’, allowing them to proclaim their valued grandparent status to visitors or friends.

Extensive research highlights the relationship between intergenerational support and older people’s health and wellbeing (Duflos and Giraudeau Reference Duflos and Giraudeau2021; Levitt et al. Reference Levitt, Guacci and Weber1992; Merz and Huxhold Reference Merz and Huxhold2010). Wellbeing has also been addressed from a caring perspective, although Galvin and Todres (Reference Galvin and Todres2011: 12) challenge simplistic assumptions that ‘certain conditions will inevitably lead to certain well-being experiences’. Wellbeing is often classified as hedonic or eudaimonic. For Thorsteinsen and Vittersø (Reference Thorsteinsen and Vittersø2020), hedonic (or subjective) wellbeing involves ‘the presence of pleasant affect, the absence of unpleasant affect and overall satisfaction with life’, whereas eudaimonic wellbeing concerns the realization of human potential, embracing meaning, values and personal growth. Both kinds of wellbeing could conceivably be facilitated by grandchildren’s care.

Care and consumption

The relationship between care and consumption is contested, reflecting how love and money are often placed in opposition to each other (Lindsay and Maher Reference Lindsay and Maher2013; Taylor Reference Taylor, Taylor, Layne and Wozniak2004). Nonetheless, Shaw et al. (Reference Shaw, McMaster, Longo and Özçaglar-Toulouse2017) argue that a consumption lens can foster more nuanced understandings of care ‘involving the combination of awareness, responsibility and action’ (p. 417) across a range of consumption activities and stakeholders.

The value of this lens depends largely on how consumption is defined. It is often understood narrowly as the purchase and using up of goods or services, or ideologically as linked to power and inequality, but it is also a meaningful social practice with emotional and symbolic as well as practical or economic dimensions (Woodward Reference Woodward2013). Various goods and services form part of social practices that combine activities, things, understandings, know-how, emotions and motivations (Warde Reference Warde2005). Thus, mundane material objects are often embedded in taken-for-granted routines that are nonetheless crucial parts of everyday life (Miller Reference Miller2008). Drawing on Miller’s (Reference Miller1987) dialectical theory of materiality, Mullins (Reference Mullins, Venkatesh, Miles, Maclaran and Kravets2018: 16) argues that things – material or immaterial – are ‘part of an imagined and embodied human experience that is profoundly shaped by objects themselves’. From this perspective, things are more than a set of qualities: they offer ‘affordances’ or ‘action possibilities’ (Gibson Reference Gibson1986) realized in interaction with other human and non-human actors (Schwarz et al. Reference Schwarz, Aufschnaiter and Hemetsberger2023).

In health and social care contexts, Buse et al. (Reference Buse, Martin and Nettleton2018) refer to the ‘mundane materialities of care’, highlighting how everyday material artefacts shape moments of ‘doing’ and receiving care. Dressing people with dementia, for example, involves more than manoeuvering bodies into clothes: care workers choose clothing styles that respect or erode personal identities and contribute to physical (dis)comfort, while tactile, sensory dimensions of fabric foster human connections during the dressing encounter (Buse and Twigg Reference Buse and Twigg2018).

Prior studies have examined how mundane material goods and services are bound up with everyday practices of ‘doing family’ (Morgan Reference Morgan1996). Lindsay and Maher (Reference Lindsay and Maher2013) highlight the ‘profoundly relational’ nature of consumption in families, arguing that ‘it is the daily practices of consumption – planning, purchasing, preparing and using – that express and achieve family life, identity, belonging and care’ (p. 5). Sociologists, anthropologists and consumer culture scholars have examined how mothers in particular engage in ‘caring consumption’ (O’Donohoe et al. Reference O’Donohoe, Hogg, Maclaran, Martens and Stevens2014; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Layne and Wozniak2004; Thompson Reference Thompson1996). Detailed studies have explored the minutiae – and value – of routine, taken-for-granted practices including grocery shopping (Miller Reference Miller1998), feeding the family (DeVault Reference DeVauIt1991; Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Harman and Cappellini2021), or working out ‘how much of what is best’ in family consumption of food, technology, alcohol and sexualized products (Lindsay and Maher Reference Lindsay and Maher2013: 17).

Studies of caring consumption have also explored adult children’s care of parents in later life and how this is bound up with marketplace offerings such as residential care homes, social care packages and technology (Barnhart and Peñaloza Reference Barnhart and Peñaloza2013). Also moving beyond the nuclear family household is Kastarinen et al.’s (Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023) study of ‘intergenerational caring through consumption’, which explores how grandparents showed love and concern for grandchildren through everyday consumption practices including cooking, gift-giving and shared leisure activities. Still underexplored in the literature, however, are the ways in which grandchildren themselves may engage in caring consumption, and how grandparents experience such care.

The circulation of care

The complex flows of intergenerational care within families are highlighted in Baldassar and Merla’s (Reference Baldassar, Merla, Baldassar and Merla2014) circulation of care theorizing, developed to explain how transnational families maintained kinship, intimacy and co-presence from a distance, within ‘intergenerational networks of reciprocity and obligation, love and trust’ (p. 7). Studies in this tradition identify myriad forms of caring about and caring for others, within and beyond transnational contexts, making this lens appropriate for exploring the caring practices of families separated by Covid.

Exploring the circulation of care among cohabiting grandparents, parents and adult grandchildren, Souralová and Žáková (Reference Souralová and Žáková2019) found that practical, financial, emotional and moral support was provided through ‘big’, obvious actions and ‘little’, routine, taken-for granted activities like chatting over coffee. Caring could be hands-on, delivered in person, or accomplished virtually, using technology and other goods and services. Furthermore, the boundaries between giving and receiving care could blur: care-givers can benefit from feeling needed and appreciated, just as accepting or receiving care from others can be an act of generosity in itself (Souralová and Žáková Reference Souralová and Žáková2019).

Although they do not refer explicitly to this framework, Eldén et al. (Reference Eldén, Anving and Wallin2022) interviewed Swedish grandparents, parents and grandchildren to explore intergenerational experiences of care during the pandemic. These authors found that doings and feelings (including worries and relief) were intertwined within those experiences. Different generations found new, often digital ways of staying in touch from a distance. Several grandchildren described their efforts to balance grandparents’ need for connection and need for safety through physical separation, while parents and grandparents sometimes prioritized intergenerational relationships over separation, justifying risk-taking as a form of care. Although this is a rich and insightful examination of intergenerational care flows, it does not focus on grandparents’ experiences of receiving care from grandchildren or dwell on goods and services as part of those experiences.

Methodology

Despite the wealth of research on intergenerational solidarity and grandparent–grandchild relationships, relatively little is known about grandparents’ experiences of receiving care from their grandchildren or the role of materiality in such care. This article seeks to fill this research gap by asking how grandparents experienced receiving care from grandchildren, and what role consumption practices played in those experiences. It does so by drawing on a wider consumer culture study of Scottish and Danish grandparents’ perspectives on the circulation of care within families during the early stages of Covid-19.

Grandparent–grandchild relationships are shaped by temporal, social and cultural contexts (Kahana et al. Reference Kahana, Kahana, Goler, Kahana, Hayslip and Fruhauf2019; Kastarinen et al. Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023). The pandemic was considered an appropriate time for undertaking this study since it encouraged reflections on ‘normal’ family life (Eldén et al. Reference Eldén, Anving and Wallin2022; Vanderhout et al. Reference Vanderhout, Birken, Wong, Kelleher, Weir and Maguire2020). Turning to social and cultural contexts, the study was not designed as an international comparative analysis. Rather, grandparents were recruited from Denmark and the UK (specifically Scotland) following the principle of purposive sampling in qualitative research (Palinkas et al. Reference Palinkas, Horwitz, Green, Wisdom, Duan and Hoagwood2015). This enabled exploration of different levels of intensity in grandparents’ experiences of interacting with grandchildren, before and during the disruptions of Covid.

National welfare policies influence family culture, including expectations of the grandparental role and the opportunities for both parents to work (Albertini Reference Albertini2016; Bertogg Reference Bertogg2023; Bordone et al. Reference Bordone, Arpino and Aassve2016). In Denmark, the state is the main provider of childcare and two parents working full-time is the norm, along with generous maternity pay (Chung et al. Reference Chung, Hrast, Rakar, Taylor-Gooby and Leruth2018; Glaser et al. Reference Glaser, Price, Di Gessa, Ribe, Stuchbury and Tinker2013). Thus, in 2018, 63 per cent of Danish children under the age of three were in formal daycare (Ofsted 2023), and in 2021, 81.8 per cent of Danish mothers with children aged 0–14 worked outside the home (OECD 2024). In contrast, UK families have been conditioned not to expect much from the state (Chung et al. Reference Chung, Hrast, Rakar, Taylor-Gooby and Leruth2018). Only 39 per cent of UK children under the age of three were in formal daycare in 2018 (Ofsted 2023), although 75.4 per cent of mothers with children aged 0–14 were employed full-time or part-time (OECD 2024). Under these conditions, UK grandparents often form a ‘reserve army’ for working parents (Airey et al. Reference Airey, Lain, Jandrić and Loretto2021; Holley-Moore Reference Holley-Moore2017). Despite Denmark’s more generous state-funded childcare, Scandinavian countries share with the UK a valorization of childcare that is ‘child-centred, expert-guided, emotionally absorbing, labor-intensive, and financially expensive’ (Hays Reference Hays1996: 8; Harman et al. Reference Harman, Cappellini and Webster2022; Faircloth Reference Faircloth, Lee, Bristow, Faircloth and Macvarish2023; Eldén et al. Reference Eldén, Anving and Wallin2024).

Denmark and Scotland had contrasting national policy responses to Covid (Olagnier and Mogensen Reference Olagnier and Mogensen2020; SPICe 2023). On 14 June 2020, when interviews were underway for this study, the Stringency Index score, which ranged from 0 to 100 based on nine indicators including work/school closures and stay-at-home requirements (Roser Reference Roser2021), was 57.41 for Denmark and 73.15 for the UK (Mathieu et al. Reference Mathieu, Ritchie, Rodés-Guirao, Appel, Giattino, Hasell, Macdonald, Dattani, Beltekian, Ortiz-Ospina and Roser2020). Within the four nations of the UK, policies and legislation diverged from May 2020 onwards, with Scotland having the UK’s highest average Stringency Index score for the most days in 2020 (Tatlow et al. Reference Tatlow, Cameron-Blake, Grewal, Hale, Phillips and Wood2021).

Semi-structured interviews, lasting approximately 60 minutes, were undertaken with 30 grandparents in Scotland or Demark, who would normally see grandchildren at least twice a month. Recruitment materials referred to grandparenting and everyday family life before and during the pandemic, and asked how ‘the big and little things you and other family members usually do for each other’ might have changed under social distancing. Following ethical approval from the first author’s institution, standard processes were followed including the use of participant information sheets and consent forms. Participants received a small token of thanks for their time.

Recruitment took place through multiple social media platforms, organizations and personal networks. This resulted in interviews with eight grandmothers, one grandfather and four grandparent couples in Scotland, and with one couple and 11 grandmothers in Denmark. Participants ranged in age from 51 to 82, and had grandchildren whose ages ranged from a few weeks to 23 years. Although efforts were made to recruit a wider range of participants, those interviewed were predominantly female, White and middle-class. All described heterosexual relationships for themselves, and LGBTQ+ family members were only referenced once. Reflecting the heterogeneity of older adult lives (Enssle‐Reinhardt and Helbrecht Reference Enssle‐Reinhardt and Helbrecht2022), some participants were separated, divorced or widowed, and some had adult children who were lone parents. Some were part of blended families which had introduced ‘bonus’ grandchildren. In one case, ‘grandmother’ was a treasured honorary title.

Interviews were conducted in summer 2020, approximately three months into pandemic regulations, when restrictions were easing more in Denmark than in Scotland. Given those restrictions, grandparents were interviewed online (one by telephone). Inevitably, participants were on the active side of the digital divide, possessing multiple devices like smartphones, laptops and iPads.

Each interview was conducted by an author or another experienced researcher, all aged 50+, female and in the middle generation of their own families. Participants provided brief life histories and discussed who they considered close family, patterns of family interaction before the pandemic and how/whether they helped each other. Specific questions were asked about time with grandchildren, with and without parents present, and things that they provided or bought for grandchildren. They were then asked about how family interactions had changed during the pandemic: what stopped, what started, what they missed most and least, and how they helped each other. Finally, they discussed possible changes to family relationships arising from their experiences of the pandemic.

Using verbatim transcripts, thematic analysis was undertaken, informed by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2021) and Gioia et al. (Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). Each researcher shared interview summaries and reflections and undertook initial coding, and this was followed by regular discussion of interviews, transcripts, codes and themes between the authors. The UK dataset was analysed by both authors and the Danish dataset was analysed by the second author, who translated key quotes into English as the analysis progressed. In the following section, ‘DK’ attributes quotes to Danish participants and ‘S’ to participants from Scotland. Participant ages are also noted.

Findings

When asked how family members helped each other, it was striking how much grandparents talked about feeling supported and cared for by their grandchildren, including very young children, and how significant this seemed for their wellbeing. Thus, while the interviews described many other flows of help, the focus here is on participants’ accounts of receiving care from grandchildren. As expected, Danish grandparents reported less pre-pandemic involvement in regular childcare than their Scottish counterparts, and were isolated from other family members for less time by social distancing restrictions. Despite these differences, Danish and Scottish participants painted very similar pictures of receiving care from grandchildren during the early stages of the pandemic.

Following Tronto’s (Reference Tronto1993, Reference Tronto1998) formulation, grandparents’ accounts of receiving care are presented here in relation to grandchildren’s caring about; caring for and actively care-giving; and expressing appreciation of receiving care. Resonating with theorizing around intergenerational caring through consumption (Kastarinen et al. Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023) and mundane materialities of care (Buse et al. Reference Buse, Martin and Nettleton2018), these sections show how banal things and everyday consumption practices were woven into narratives of receiving care from grandchildren. These narratives suggest that participants sometimes experienced care from grandchildren as autonomous (initiated and performed independently of the parent) and sometimes as embedded in parental practices, for example by being initiated or orchestrated by a parent (Matos and Neves Reference Matos, Neves, Arber and Timonen2012). Regardless of the form it took, the mundane materialities of grandchildren’s care appeared to foster grandparents’ wellbeing, not least by reassuring them that they matter to younger generations.

Experiencing grandchildren caring about grandparents

Participants offered many accounts of grandchildren caring about them, noticing how they were feeling and showing sensitivity to their needs. Lena (DK, 63) recalled her nine-year-old grandson commenting that she was always cleaning, cooking and tidying, and wondering what this meant for her:

I have always worked too much and that is probably still part of me. Frederik, he said to me this weekend ‘Granny do you never have time completely off?’ … it just sounded so sweet.

Cleaning, cooking and tidying have been characterized as invisible, gendered work (DeVault Reference DeVauIt1991) Although Lena showed no resentment towards such ‘ordinary devotional duty’ (Miller Reference Miller1998: 21), she was touched that her grandson did not take her hard work for granted, and cared about her own wellbeing.

Other accounts of being cared about rarely referred to consumption practices. For example, some participants reported grandchildren’s heightened concern about them during the pandemic. Mike (S, 63) described how his granddaughters (aged eight and nine) were particularly conscious of his situation following his divorce:

Ailsa is especially very robust, she’s very sensitive. She’ll say things about, ‘Grandpa is on his own’. So they’re obviously thinking about it.

Bill (S, 80s) appreciated his teenage grandchildren’s sensitivity in handling their evolving relationship, showing in the blurred lines between giving and receiving care (Souralová and Žáková Reference Souralová and Žáková2019). Commenting on how things had changed even before the pandemic, he noted that

They’re growing out of needing us the way they did. Although they’re very good pretending we’re a help.

Perhaps surprisingly, grandparents also felt cared about by very young grandchildren, even if babies and toddlers could hardly pay careful attention to their needs. At the most basic level, many participants described their relief on being remembered and recognized by their youngest family members despite the separation of lockdown. This seemed to offer validation of their importance in these young children’s lives. For example, Cathy (S, 58) enjoyed video calls with her toddler grandson, and was delighted that

[…] we go on WhatsApp. Ken [aged two] clearly recognizes me on the phone, calls me Nana, Nana.

Smartphones, apps and social media platforms allow family members to maintain social relationships across time and space, with virtual co-presence and digital media intimacy particularly important during the pandemic (Schwarz et al. Reference Schwarz, Aufschnaiter and Hemetsberger2023). For example, the audio-visual affordances of video calls allowed grandparents to track the many changes in their young grandchildren (Watson et al. Reference Watson, Lupton and Michael2021). Here, Cathy highlights how WhatsApp’s audio-visual affordances also allowed her to feel cared about by her toddler grandson.

Experiencing grandchildren caring for and care-giving

Although all of Tronto’s phases of caring are interlinked, grandchildren’s caring for and care-giving were particularly difficult to disentangle in grandparents’ accounts, which often referred to mundane consumer goods and services. These included displaying affection; choosing to spend time; initiating and maintaining communication routines; practical help; emotional support; and giving back. These practices were themselves intertwined – for example, affection could be displayed through multiple practices.

Displaying affection

Expressions of emotional closeness are key to grandparent–grandchild relations (Duflos et al. Reference Duflos, Giraudeau and Ferrand2022) and one of the pandemic’s many cruelties was that social distancing deprived grandparents of young children’s exuberant physical displays of affection (Derrer-Merk et al. Reference Derrer-Merk, Ferson, Mannis, Bentall and Bennett2022). Bente (DK, 61) missed ‘those hugs and yelps of happiness when you turn up’, highlighting the affirmation she treasured as well as the physical connection. This made reunions when restrictions eased all the more precious, even if hugs and kisses were still prohibited. Participants expressed sadness at young grandchildren’s confusion or frustration at the rules, but also pride in their understanding, adaptability and determination to express affection. When Kathrine (DK, 76) visited her family in their garden, her three-year-old grandson was upset that she could not hug, kiss or lift him. Like other toddlers who resorted to hugging legs, he bent the rules by crawling up to her and touching her knee. Similarly, when Fay’s (S, 60s) four-year-old granddaughter was allowed to visit again, she had to stay outside in the garden,

and her first instinct was to come running in and I had to say to her [not to come inside]. And I watched her face crumple. And she said, ‘Yes, it’s because of the germ. But Grandma, you’ve got a very clean house. Why can’t I come in?’ [Later] she was chatting to us, but she knew enough to keep away from us. So that was all new, whereas she would be leaping up and having a cuddle.

For Buse et al. (Reference Buse, Martin and Nettleton2018), materialities of care are deeply contextual and enfolded in space and time. At this point in the pandemic, gathering outside in the garden rather than indoors allowed Fay’s family to care for each other, as did keeping their distance from each other. Fay’s granddaughter learnt how to play her part in this multi-directional circulation of care (Baldassar and Merla Reference Baldassar, Merla, Baldassar and Merla2014) by forgoing the usual cuddles and staying outside, but her reluctant compliance highlights the affection she has for her grandparents. Fay also seemed gratified by her noticing Grandma’s clean house, rendering invisible labour visible and appreciated (Miller Reference Miller1987).

Choosing to spend time

Reflecting changes in grandparent–grandchild relations over the lifecourse (Sciplino and Kinshott Reference Sciplino and Kinshott2019), there were fewer accounts of older teenage or young adult grandchildren offering effusive displays of affection. Older grandchildren’s willingness to spend time with them seemed to provide different but compelling evidence of affection, as well as good company and enjoyable times. In situations such as these, the reciprocal nature of care and its expression through material goods were evident. Kathrine (DK, 76), for example, relished invitations to meet up with her 19-year-old grandson and his girlfriend by the fjord. Picnic food and games created the conditions for Kathrine to experience these meetings as a time of fun and togetherness initiated by her grandson rather than as part of a wider family gathering. The plastic gloves and outdoor setting enabled them to take care of each other’s safety while sharing food and enjoying each other’s company.

Even preschool children were described as using material goods to display their desire to spend time with grandparents. For example, when Kathrine’s three-year-old grandson heard the adults talking about Covid restrictions easing,

Noah disappeared at some point and then he came back with a holdall, and he had put his pacifiers, teddies and two nappies into it. ‘So, Noah, where are you going?’ ‘To Granny’s.’ He had heard that now he could come to Granny’s house.

Although Noah’s actions can be seen as egocentric (Piaget 1951/Reference Piaget and Piaget1995) rather than a response to a perceived need, Kathrine was clearly touched that visiting her meant so much to him. As Lindsay and Maher (Reference Lindsay and Maher2013: 15) note, care within families includes many small and subtle acts of consumption. Noah’s taking it upon himself to pack a holdall in the hope of going back to Granny’s house emphasized to Kathrine how much he valued his time with her.

Initiating and maintaining communication routines

Many scholars have documented how digital communications technologies afford expressions of family affection, concern and closeness (Lindsay and Maher Reference Lindsay and Maher2013; Schwarz et al. Reference Schwarz, Aufschnaiter and Hemetsberger2023; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Lupton and Michael2021). Participants often described grandchildren using mobile devices and social media platforms to ‘do’ intergenerational togetherness and, consistent with pre-Covid research (Kahana et al. Reference Kahana, Kahana, Goler, Kahana, Hayslip and Fruhauf2019), actually initiating this. Particular apps or platforms were already a taken-for-granted part of the younger generation’s world, and teaching less knowledgeable grandparents how to use them offered new, remote ways of remaining playmates. Tina (DK, 53) talked about the fun she had with her 11-year-old grandson once she learnt how to use TikTok and Snapchat:

Oscar, he sends me some TikTok or whatever it is called, this thing that is so modern. I don’t understand any of it, but [laughs] then I go out into the garden and find a flower and send him a picture of it, and then we can laugh a bit about that. So we snap, too.

Tina appreciated Oscar introducing her to communication apps and helping her master the basics of using them. She enjoyed seeking out things to photograph and send him so they could ‘laugh a bit’. What delighted her, however, was the regular, direct contact with her grandson that the apps afforded. She could receive up to seven Snapchat messages a day from him, suggesting a special grandparent–grandchild bond independent of the middle generation (Klein Reference Klein2022):

Interviewer: Yes, that is nice. It sounds like you are an important person for him.

Tina: I am. I have no doubt about that.

Annie (S, 65) emphasised her 23-year-old grandson Andrew’s care and concern for her during the pandemic:

Andrew texts me every single night, every single night to say goodnight. We have this family chat on WhatsApp and he texts me every night. He will phone, depending on what he’s got on, but he does keep in touch.

Here, Annie distinguishes between the wider ‘family chat’ using the group function on WhatsApp which facilitated sociality and intimate co-presence (Watson et al. Reference Watson, Lupton and Michael2021) and Andrew’s nightly texts to her alone, which both communicated and enacted his solicitude: her sense of his unwavering commitment to her is underscored by the three mentions of his texting ‘every (single) night’.

Practical help

Several participants talked about grandchildren providing practical support. Reflecting older grandchildren’s gradual ‘emancipation’ from parental influence (Wetzel and Hank Reference Wetzel and Hank2020), some grandchildren visited on their own, walking or cycling over during lockdown to bring home baking or groceries, or, once outdoor contact between households was allowed, to do some gardening. Such flows of care may be more complex and multi-directional than they first appear. ‘Independent’ acts of caring consumption could have been orchestrated by parents, and they also offered opportunities for grandparents to pass on their knowledge, skills and values (Kastarinen et al. Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023). Wendy (S, 80) was clinically vulnerable and emphasized that her 13-year-old grandchild’s gardening efforts were mutually beneficial:

Patrick gets paid for cutting my grass, and that’s something he can do without me coming out of the house. So he comes when the grass needs cutting and cuts the grass. He does it perfectly willingly because he gets paid his pocket money and he does a good job.

Paying Patrick to cut her grass could be seen as transforming an act of care into a commercial transaction, with money contaminating love (Taylor Reference Taylor, Taylor, Layne and Wozniak2004). That interpretation, however, ignores Wendy’s pleasure in giving him pocket money and being able to pass on values about the rewards for work done well, and the blurred boundaries between giving and receiving care (Souralová and Žáková Reference Souralová and Žáková2019).

Emotional support

The isolation and strain of the pandemic were evident throughout the interviews. Some participants were particularly vulnerable to the disease themselves. Others had lost friends or family members, or worried about those who were ill or risked infection through their work. Many grandparents described occasions when their spirits had been lifted by grandchildren’s intergenerational caring through consumption (Kastarinen et al. Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023), including handmade gifts of pictures, posters or baking. Wendy (S, 80) recalled becoming very upset on hearing that the initial lockdown was to be extended:

I wasn’t sure I was going to be able to keep [my] spirits up for another seven weeks. Then, this is a kind of thing that is just amazing. Susan and the boys (13 and eight) arrived at the front of the house … They came with thick chalk, and they wrote, ‘We love you Granny’ on the pavement and drew hearts and flowers and stars and things. You know, it was just exactly what I needed at that particular point. I thought, ‘Right, OK. We can do this’. And I just thought it was so sweet.

Wendy’s account of this pivotal experience exemplifies the creativity and generativity of family consumption practices, with care given and received through small acts and everyday objects (Lindsay and Maher Reference Lindsay and Maher2013). Her account also highlights materialities of care as contextual (Buse et al. Reference Buse, Martin and Nettleton2018): at other times and in other places, that same thick chalk may be used on paper to create art for the family fridge, or on pavements to set up games like hopscotch. Here, however, it was used by Wendy’s grandchildren to transform the front of her house with words and images recognizing her vulnerability and helping her find the resilience she needed. This instance also highlights how grandchildren’s care-giving could be embedded within parental practices. Wendy’s grandsons chalked messages of love on her driveway, but they did so with their mother, who had driven them there for this purpose. As Matos and Neves (Reference Matos, Neves, Arber and Timonen2012) observe, grandchildren’s caring practices are often shaped by parents. By involving her children in care-giving for grandparents and modelling empathy, these children’s mother was socializing her children into practices of intergenerational caring through consumption. Another example of parents providing the ‘scaffolding’ (Vygotsky Reference Vygotsky1978) for grandchildren’s care-giving was given by Mary (S, 60s), who was cheered up by a visit from her family once Covid restrictions had eased somewhat:

we did see them last week for the first time since lockdown through the window. They sat in the garden and we sat in the house … Poppy posted some cards through the window, posted a chocolate-covered raisin. It was lovely.

Clearly three-year-old Poppy’s visit was managed by her parents, who may have encouraged or even helped her to make the cards and ‘post’ them through the window. What is interesting here is how she improvised: having ‘posted’ the cards, she added her own distinctive ‘little’ act of care (Souralová and Žáková Reference Souralová and Žáková2019), using the partly open window to share her chocolate raisins with her grandparents. While a chocolate-covered raisin, possibly melting in her hand, was not necessarily the most appetizing treat, it meant a lot to Mary that Poppy took it upon herself to do something kind for her grandparents.

Giving back

Participants talked about ways that grandchildren ‘gave back’ (Kemp Reference Kemp2004), rewarding years of care and attention by making their grandparents proud. This was certainly the case for Annie (S, 65), who had helped raise her 23-year-old grandson Andrew when his parents divorced. She felt rewarded by the kind of young man he had become, not only because of his university degrees and work ethic:

He gets on well with most people. Everybody has a good word to say to him … He’s just a nice lad. A very nice, well-mannered lad.

She notes that while she still liked to give him money, he would protest, saying, ‘Gran, that’s not why I’m here’. This resonates with ‘not doings’ as care-giving (Souralová and Žáková (Reference Souralová and Žáková2019): by not wanting to take money from Annie, Andrew is highlighting that seeing her is the only reward he needs.

In some cases, grandchildren seemed to ‘give back’ by paying forward. Reflecting the close connection between generativity and caring (Kastarinen et al. Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023), this took the form of demonstrating to grandparents that their values had indeed been passed on to another generation. Although it is not difficult to imagine a role for materiality in such cases, consumption did not feature in participant accounts of this form of care. For example, several talked proudly about their grandchildren’s strong sense of kinship and obligation. Lena (DK, 63) was delighted that her grandsons (aged 14 and nine) were ‘thick as thieves’. A bereaved mother herself, she was consoled that her older grandson had inherited his late mother’s qualities:

The big one, he is so incredibly caring, really very, very – but he has that after his mother. She really was, she always hugged and protected other people.

Taken together, the examples discussed in this section highlight the many ways in which grandparents experienced their grandchildren – from toddlers to young adults – as caring for them and as active care-givers. Many of the accounts shared by grandparents were of ‘little’ acts of care (Souralová and Žáková Reference Souralová and Žáková2019), often involving little things given to or done for them, highlighting how much the mundane materialities of care (Buse et al. Reference Buse, Martin and Nettleton2018) matter in this context.

Experiencing grandchildren’s appreciation of care

Highlighting the blurred boundaries between giving and receiving care (Souralová and Žáková Reference Souralová and Žáková2019), and the moral burden of responsiveness to care (Tronto Reference Tronto1993), participants greatly valued grandchildren’s expressions of appreciation. Many had sent their grandchildren ‘care packages’, activity packs, baking or handmade items during the pandemic, and talked about how much they appreciated receiving thank-you cards, artwork or videos. During the pandemic, Birthe (DK, 60) used FaceTime to help home-school her 13-year-old grandson. His maths level improved as she made lessons fun: for example, she ‘punished’ him for wrong answers by eating some of his favourite chocolate. She was delighted that when the schools reopened, he asked to continue ‘Granny’s Corona school’.

Reflecting changing family configurations and contemporary grandfathers’ closer emotional bonds (Mann et al. Reference Mann, Tarrant and Leeson2016), it was important to Mike (S, 63) that his granddaughters loved his cooking. Both Mike and his daughter were divorced, and he had been closely involved in his granddaughters’ lives. As Lindsay and Maher (Reference Lindsay and Maher2013: 73) note, food provisioning practices ‘directly sustain family lives but carry wider relational meanings and salience’. His granddaughters’ appreciation of the food he made for them mattered because

Cooking itself is an act of love because there’s health in it, heart in it, you want to make it good.

Some participants talked about acts of appreciation over a longer timescale. Lis (DK, 69), for example, was delighted by a message from her 15-year-old grandson about plans that he and his friend had hatched:

Yesterday a text arrived saying that…. they wanted to serve sausages and snobrød [bonfire-baked bread] for us.

Illustrating complex, temporal and reciprocal flows of care, Lis explained that her grandson’s friend had often accompanied him on visits to their house and been fed there many times. Younger generations may never be able to repay the debts they owe the older generation (Finch and Mason Reference Finch and Mason1993), but the boys’ desire to host and feed her husband and herself was understood as an act of gratitude and acknowledgement. Since feeding the family has long been considered invisible women’s work (De Vault Reference DeVauIt1991), being fed by her grandson may have led Lis to feel that her efforts over a long period had been seen and appreciated. The plan also appeared to have been hatched independent of the middle generation, reinforcing the grandparent–grandchild bond (Klein Reference Klein2022).

Caring, mattering and wellbeing

The various ways in which grandchildren cared about, cared for and gave and received care could be framed as social connection and support, contributing to grandparental wellbeing during the pandemic (Derrer-Merk et al. Reference Derrer-Merk, Ferson, Mannis, Bentall and Bennett2022). Many of the caring practices discussed here could also be theorized as contributing to grandparents’ hedonic wellbeing. However, grandparents’ accounts suggest an additional route to wellbeing: fundamentally, grandchildren’s care communicated to grandparents that they matter. As Flett (Reference Flett2022: 4–5) notes, mattering, ‘feeling important, visible and heard … is a vital source of resilience and adaptability’, making a distinctive contribution to wellbeing. This is not surprising since relationships promoting a sense of belonging also promote a sense that life is meaningful (Wissing Reference Wissing2014), which contributes in turn to eudaimonic wellbeing (Thorsteinsen and Vittersø Reference Thorsteinsen and Vittersø2020). This seems especially important for older generations during Covid, given their physical vulnerability to disease, their isolation and anxiety, and their othering by societal and media discourses of expendability (Flett and Heisel Reference Flett and Heisel2021). Thus, Cathy (S, 58) took pleasure in describing a video call she had received because

Ken [aged two] had built a tower with Lego and wanted to show his granny.

Cathy was delighted that Ken thought of her when he did something he was proud of and wanted to share his achievement with her, even though he had wandered off almost immediately afterwards. Similarly, seeing preschool grandchildren figuring out acceptable forms of physical affection in Covid times, or packing a holdall because it was possible to stay with Granny again, told grandparents that they were important. Describing how her grandchildren would ‘just throw themselves at me’ when she visited unexpectedly before Covid, Susan (S, 64) linked this welcome to her own self-worth, saying, ‘You think, “I can’t be that bad”’. This sense of validation is also demonstrated by Lis’s (DK, 69) account of being invited by her grandson and his friend to the bonfire meal:

I was really touched … Because when you are 15, right, and then, there are so many other things …

Recognizing that her grandson’s teenage life was expanding in various ways, Lis expected to become a less important part of it. That made being thought of and invited to eat with him and his friend all the more precious. Indeed, there was a sense in which receiving any form of care from grandchildren – especially younger ones – exceeded expectations, thereby surprising and delighting participants in this study.

For Prilleltensky and Prilleltensky (Reference Prilleltensky and Prilleltensky2021), mattering is bound up with reciprocity: both having and giving value to others. This may explain why grandparents were so pleased when their own acts of care were appreciated or when they felt they were making a difference. For example, Tessa (S, 61) described a phone call when her daughter prompted her five-year-old grandson to tell her how much he loved an educational game she had given him:

Julia [daughter] said to him the other day, ‘Tell Nanny’, and he said, ‘the best thing about lockdown is Bird Bingo’.

Tessa proceeded to detail what he had learnt from the game about different types of bird. This meant a lot to her because she had taken him on many pre-Covid walks, sharing what she knew and loved of the natural world with him. Seeing him continue to learn about birds while separated from her, through a game she had given him, offered evidence of her generativity (Erikson Reference Erikson1950; Kastarinen et al. Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023) as well as their distinctive bond (Klein Reference Klein2022).

Discussion and conclusions

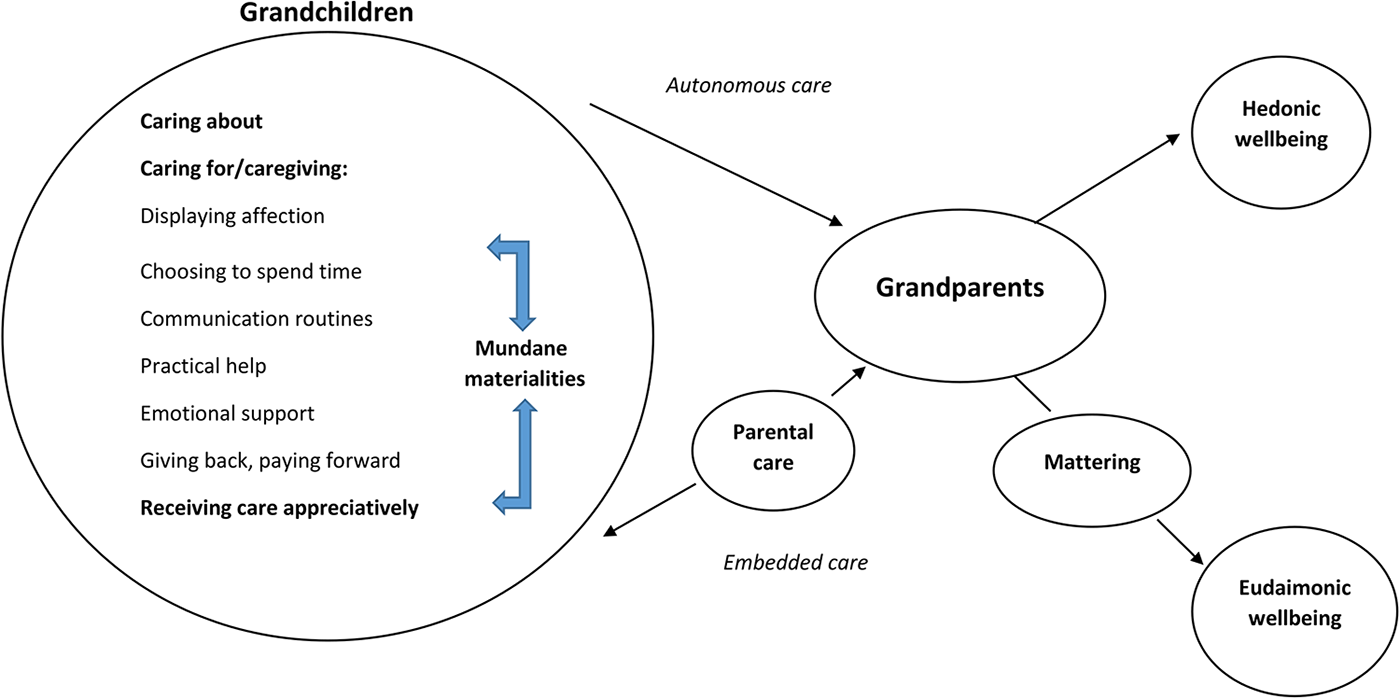

Although prior research highlights the importance of emotional closeness and mutuality in grandparent–grandchild relations (Duflos and Giraudeau Reference Duflos and Giraudeau2021; Duflos et al. Reference Duflos, Giraudeau and Ferrand2022), relatively little is known about older people’s experiences of receiving care from their grandchildren, especially when grandparents are not particularly ill or frail. The current study addressed this research gap by exploring Danish and Scottish grandparents’ experiences of receiving care from grandchildren in the early stages of the Covid pandemic, drawing on holistic theorizations of care (Baldassar and Merla Reference Baldassar, Merla, Baldassar and Merla2014; Tronto Reference Tronto1993, Reference Tronto1998) and considering how these are bound up with everyday family consumption practices (Lindsay and Maher Reference Lindsay and Maher2013). Figure 1 offers a diagrammatic summary of the study’s key findings.

Figure 1. Grandchild care flows, mattering and wellbeing.

Despite different experiences of state welfare systems and Covid regulations, Danish and Scottish grandparents told very similar stories about their grandchildren’s caring practices, and how these contributed to grandparental wellbeing. Addressing the research gap around younger grandchildren’s everyday contributions to the grandparent–grandchild relationship (Kahana et al. Reference Kahana, Kahana, Goler, Kahana, Hayslip and Fruhauf2019), this study documents participants’ experiences of receiving care from grandchildren ranging in age from 2 to 23. Consistent with Tronto’s (Reference Tronto1993, Reference Tronto1998) interrelated phases of caring, participants described many instances of grandchildren caring about them, caring for them, actively care-giving and receiving care appreciatively.

As Shaw et al. (Reference Shaw, McMaster, Longo and Özçaglar-Toulouse2017) argue, much research has framed care exclusively in terms of labour, whereas viewing it through a consumption lens can offer more nuanced understandings. This study extends understanding of the ‘mundane materialities of care’ (Buse et al. Reference Buse, Martin and Nettleton2018) and of caring consumption within families (Kastarinen et al. Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023; Lindsay and Maher Reference Lindsay and Maher2013) by showing how grandparents’ experiences of receiving care from grandchildren were often materialized by mundane, everyday materials, both digital and physical: sticks of chalk, mobile phones, a WhatsApp call to show a Lego tower, a holdall, drawings, bonfire-baked bread and even a single chocolate raisin shaped the care provided by grandchildren and experienced by grandparents. Clearly there were limits to what the very youngest children could do for their grandparents, but the fact that they showed they cared – often in creative ways – made their efforts all the more appreciated. Souralová and Žáková (Reference Souralová and Žáková2019) distinguished between ‘big’ and ‘little’ acts of care. In this study, it seemed that a ‘little’ care – often, though not always, enacted through ‘little’, even trivial things – went a long way for grandparents. It was also clear that grandchildren were actively involved in ‘the multi-directional, intergenerational and creative uses of consumption in creating family life’ (Lindsay and Maher Reference Lindsay and Maher2013: 19), even as family life was forcibly reconfigured by the pandemic.

This study also contributes to understandings of the relationships between care-giving and wellbeing (Galvin and Todres Reference Galvin and Todres2011), and between care-giving and mattering (Pychyl et al. Reference Pychyl, Flett, Long, Carreiro and Azil2022), in the context of grandparenthood. Receiving care from grandchildren certainly seemed to foster grandparents’ hedonic wellbeing, bringing them pleasure and satisfaction. More fundamentally, experiences of grandchildren’s care communicated to grandparents that they matter. This message was crucial during Covid, which was for many older people a time of isolation and vulnerability, exacerbated by media discourses describing them in terms of expendability and burden (Flett and Heisel Reference Flett and Heisel2021). Feeling that they mattered to the people they loved seemed to contribute to grandparents’ eudaimonic wellbeing, fostering a sense of self-worth, resilience and hope.

Grandchilden’s caring consumption practices could be seen as autonomous, performed independently of parents, or embedded in parental caring practices. The distinction between these was not necessarily clear-cut, as parents could well have been orchestrating ‘independent’ acts of care behind the scenes. Nonetheless, each form of care appeared to contribute to grandparents’ sense of mattering, in different but complementary ways. Autonomous caring practices, such as Andrew’s nightly texts to Annie, reassured grandparents of the special place they held in their grandchildren’s lives, independent of the middle generation (Klein Reference Klein2022). Embedded caring practices also seemed valued by grandparents, as exemplified by Wendy’s gratitude when her daughter and grandsons chalked messages of love outside her house. This may be because such instances highlight the multi-directional flow of care (Baldassar and Merla Reference Baldassar, Merla, Baldassar and Merla2014) coming towards them from their children and their grandchildren. It could also evidence generativity (Erikson Reference Erikson1950; Kastarinen et al. Reference Kastarinen, Närvänen and Valtonen2023), reassuring grandparents that the caring values they had sought to instil in their own children were being passed on to the next generation.

Inevitably a study such as this has limitations, not least in relation to sample composition. Future studies could usefully explore grandparents’ experiences of receiving care from grandchildren in other cultural, temporal and socio-economic contexts, and home in on gendered aspects of giving and receiving grandchild care. Furthermore, while the specific experiences and perspectives of grandparents merit attention in their own right, and while grandparents in this study reflected on relationships with multiple family members, other insights may be gained from interviewing grandparent–grandchild dyads or family members spanning three or even four generations. Although this could illuminate further the ‘ordinary complexities of care’ (Eldén Reference Eldén2016), and perhaps associated tensions, Eldén et al. (Reference Eldén, Anving and Wallin2022) remind us of the ethical issues involved in undertaking interviews with different members of the same family. Finally, since material goods and consumption practices offer a rich if perhaps circuitous route to understanding people and relationships (Miller Reference Miller1987, Reference Miller2010), researchers interested in older people’s lives and relationships – within and beyond the family – may benefit from asking participants about ‘stuff’ in interviews.

Limitations notwithstanding, this study suggests several potential practical and policy directions. The many forms of grandchild care-giving reported here may encourage parents – and health and social care practitioners – to reflect on how they could involve children further in fostering grandparents’ wellbeing. Since ‘little’ acts of grandchild care, including those expressed through ‘little’, everyday things, seem to go a long way for grandparents, this need not involve much effort or expense. The contributions that grandchildren can make to older people’s hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing also highlight what those without grandchildren (or without close ties to them) may be missing. This suggests the potential for school and community-level initiatives to embed caring practices among ‘honorary’ grandchildren, fostering the wellbeing of older people and building intergenerational connections beyond the family setting.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the grandparents who shared their experiences so generously with us, to Dr Caroline Marchant for her research assistance on this project, and to the editor and reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Author contributions

Both authors have read the final version of this article and are aware of its submission. Both authors contributed to all parts of this research project and to the writing of this article.

Financial support

This study was funded by The University of Edinburgh’s College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Research Office Covid-19 Call and by an Independent Research Fund Denmark research network grant (DFF 7023-00090). The financial sponsors played no role in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data, or in the writing of the study.

Competing interests

Both authors declare that there were no competing interests.