The 2015 JOIE debate

Few concepts are as central to institutional economics as property rights, yet few have proven as conceptually contentious. A decade ago, the pages of this journal hosted a debate focused on the distinction between property and possession (Journal of Institutional Economics, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2015). The exchange pitted two fundamentally different interpretations against one another.

The critique. The debate’s catalyst was Hodgson’s (Reference Hodgson2015a) charge that the mainstream ‘economic approach to property rights’ (EAPR) conflates property with possession.Footnote

1

For Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a), possession is a pre-legal, de facto control over a resource – a physical relationship between a person and a thing. Property, by contrast, is a de jure social relationship, not a person-thing relationship, requiring legally sanctioned, enforceable rights that depend on a third-party legitimating authority (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2015a). Hodgson argued that the EAPR’s terminology – specifically its use of the term ‘economic property right’ to describe what is merely de facto control – is deeply misleading. A ‘right’, he insists, implies a legitimate claim enforceable in a court of law; for instance, a thief’s possession of stolen goods does not constitute a ‘right’, even if their control is effective (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2015a, b). Cole (Reference Cole2015) strongly supports this critique. Citing John Searle, he argues that possession is a ‘brute fact’ about the world, whereas property is an ‘institutional fact’ requiring collective intentionality and acceptance. This reliance on collective intentionality, rather than strictly on state enforcement, is a key clarification. It widens the conceptual lens to accommodate non-state (e.g., Ostromian) common-property regimes as valid, institutionalized systems.

The EAPR defense. Allen (Reference Allen2015) and Barzel (Reference Barzel2015) defended the EAPR’s framework, contending the dispute was primarily a matter of ‘semantics and focus’ Allen (Reference Allen2015, p. 711). They argued that the EAPR does not conflate the two concepts but, in fact, explicitly distinguishes between them using its own terminology: ‘legal property rights’ (what Hodgson calls property) and ‘economic property rights’ (what Hodgson calls possession) (Allen, Reference Allen2015; Barzel, Reference Barzel2015). For the EAPR, this distinction is the very foundation of its analysis. Allen (Reference Allen2015) argued that in a hypothetical world of zero transaction costs (no costs associated with establishing and maintaining rights), legal property rights and economic property rights would be identical. In the real world, however, transaction costs are always positive. This creates an inevitable gap between the law on the books (legal rights) and an individual’s actual, operational choice set (economic rights). Behaviour, they insist, is driven by this de facto reality, making ‘economic rights’ the proper focus for a positive science aiming to explain behaviour.

The methodological and behavioural divides. In his rejoinder, Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015b) forcefully rejected the ‘mere semantics’ defense. Citing the Humpty Dumpty dialogue from Alice Through the Looking Glass, he argued against philosophical nominalism (the idea that words mean whatever the user chooses). He contended that arbitrarily redefining a foundational legal term like ‘right’ (which implies legitimacy) to mean ‘possession’ (de facto control) is not analytically neutral; it is misleading and has negative consequences, especially for interdisciplinary dialogues with law (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2015b). Furthermore, this exposed a deep behavioural divide over modelling human action. Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a) argued that the EAPR’s focus on individuals maximizing their ‘economic rights’ treats law as a purely instrumental constraint. This, he charged, ignores evidence from psychology that individuals are often motivated non-instrumentally by the perceived legitimacy of the law and a moral, deontic duty to obey per se.Footnote

2

Allen (Reference Allen2015) countered that this confuses ‘motivation’ (which is always maximization) with ‘objectives’, and that moral sentiments can simply be included as an element in the utility function. Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015b) rejoined that this attempt to ‘subsume’ morality under a general utility calculus obscures its distinctive, non-instrumental character as a driver of action.

Thus, the 2015 exchange hosted two distinct debates simultaneously: (i) a terminological debate over the analytic utility of the EAPR’s lexicon versus the call to adopt ‘possession’, and (ii) a deeper conceptual debate on the proper modelling of human action and the role of law, morals, and legitimacy. This Comment deliberately isolates the first of these debates for one critical reason: it is empirically testable. While the deeper conceptual debate is of profound importance, its impact is diffuse and difficult to measure. In contrast, the terminological question – whether the profession’s working vocabulary shifted – offers an observable hypothesis. We mainly limit our analysis to this measurable lexical adoption within 58 English-language journals, bracketing the more complex question of conceptual influence. The remainder of this article proceeds as follows: Section 2 details our dual bibliometric methodology: it first presents a citation analysis to measure the visibility and evolution of the 2015 debate, followed by a multi-database text-mining analysis (Web of Science and OpenAlex) to test for the adoption of the term ‘possession’ and a broader conceptual basket of de facto keywords. Section 3 discusses the findings, offering interpretations for the disconnect between the debate’s sustained scholarly visibility and the statistically non-significant lexical shift observed in the data. Finally, Section 4 concludes by assessing the dual legacy of the exchange ten years on.

The debate’s intellectual footprint: a bibliometric analysis

This section employs two bibliometric methods: a citation analysis to assess both the static visibility and the dynamic evolution of scholarly engagement with the debate, and a text-mining analysis to determine if this engagement led to a shift in the profession’s working vocabulary.

The number of citations

While citation counts are an imperfect proxy for intellectual impact – as they do not distinguish among positive, negative, or passing references – they provide a useful approximation of the attention an academic work has received. If the debate was truly a ‘merely semantic’ issue, one might expect it to have faded into obscurity with minimal citations. Conversely, significant citation counts would suggest that the arguments raised have been actively engaged with by the academic community.

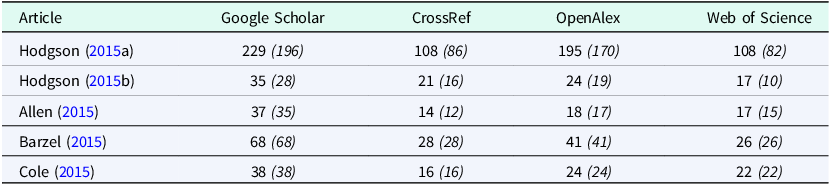

Table 1 presents the citation data for the five articles that constituted the debate, collected from Google Scholar, CrossRef, OpenAlex, and Web of Science (WoS).Footnote

3

Table 1. Citation counts for the 2015 JOIE debate articles

The data reveal several notable patterns. The first feature is the prominence of Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a)’s lead article, which has garnered substantially more citations than the four responses combined across all platforms. This is not unexpected; as the paper that initiated the exchange, it serves as the natural focal point for any subsequent discussion. Its high citation count confirms that Hodgson’s critique was, at the very least, not ignored. Among the responses, Barzel (Reference Barzel2015)’s comment stands out with the highest number of citations, followed by the articles from Cole (Reference Cole2015) and Allen (Reference Allen2015), which have received a similar level of attention.

The line graph in Figure 1 provides a dynamic perspective that complements the static totals in Table 1. These data were generated via programmatic queries to the OpenAlex database, tracking the annual count of unique works citing the symposium. The top line captures any article citing at least one of the five papers, identifying a broad audience of 225 unique works in total. The bottom dashed line serves as a more conservative proxy for direct engagement with the debate itself, tracking articles that co-cite at least two of the papers; a collection of 51 unique works has been identified.

Figure 1. Annual count of articles citing the 2015 JOIE symposium. Note: OpenAlex dataset. Counts represent unique articles. Duplicates were removed to ensure one record per article. ‘Citing at least 1 article’ refers to articles that cite at least one paper from the 2015 JOIE symposium; ‘Citing at least 2 articles’ refers to those citing two or more papers. Values for 2025 are partial, based on records available as of 4 November 2025. Note that the apparent spike in 2025 is largely a methodological artefact resulting from OpenAlex indexing separate chapters from a single book as individual citing works.

Both measures show that scholarly interest was not confined to the years immediately following the exchange but has been remarkably sustained. Notably, both general citations and specific co-citations peaked significantly in 2019–2020, five years after the debate’s publication.Footnote

4

The sustained, parallel trend of both broad citations and specific co-citations strongly suggests that the debate has had an enduring legacy, and that its core questions have remained a live issue for scholars. The apparent spike in 2025 visible in the top line is largely a methodological artefact.Footnote

5

Lexical adoption: from a single term to a conceptual basket

To test whether the debate’s engagement translated into a shift in the profession’s working vocabulary, I first compiled a corpus of academic articles by searching for the exact phrase ‘property rights’ in the title or abstract of 58 selected economics journals. This list, detailed in Appendix A, is based on (most of) the IDEAS/RePEc top 50 supplemented with relevant specialist publications. This corpus was split into three periods: a pre-debate baseline (2010-2014), an immediate post-debate period (2015–2019), and a later period (2020–2025). The first post-debate period intentionally begins with 2015, the year the symposium was published, to capture any immediate lexical response. The entire corpus was then analysed using two distinct databases: WoS and OpenAlex.Footnote

6

First, I measure the frequency of the single, specific term ‘possession’ advocated by Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a).

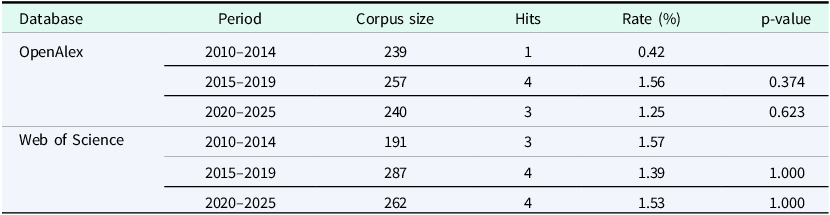

The results for the single-token test, presented in Table 2, indicate that the term ‘possession’ is extremely rare in the abstracts of the core property rights literature. The data from WoS are particularly striking: the rate of use shows no statistically significant change. While the percentage fluctuated slightly from a baseline of 1.57% (3 hits) to 1.39% (4 hits) in the immediate post-debate period, this difference is statistically indistinguishable from zero, yielding a p-value of 1.000. The OpenAlex data, while showing a larger relative increase (from 0.42% to 1.56%), is similarly statistically insignificant (p = 0.374). Furthermore, this apparent ‘increase’ is driven by a change in absolute numbers from only one hit to four, making it far too small to suggest any meaningful analytical trend. The core conclusion from both databases is identical: the specific term ‘possession’ was not adopted, and its use remained negligible post-2015.

Table 2. Frequency of ‘possession’ in articles on ‘property rights’, by period

A test limited to the single-token ‘possession’ risks a false negative. While our data show that this specific term was not adopted, the 2015 debate may have had a broader impact. The debate itself may have served as a consciousness-raising event. It could have prompted economists, regardless of which side they found more persuasive, to be more explicit and frequent in their discussion of the de facto versus de jure distinction. To test this ‘general salience’ hypothesis, a second analysis was designed. This test searches the ‘property rights’ corpus for a broad ‘conceptual basket’ of keywords associated with the de facto/de jure separation. Critically, this basket includes terms from both the critique (‘possession’, ‘possessory’, ‘de facto control’) and the EAPR’s existing lexicon (‘economic property rights’, ‘hold rights’, ‘use rights’, ‘economic rights’). If the 2015 debate successfully increased the profession’s general preoccupation with this distinction, we would expect to see a statistically significant rise in the frequency of this combined basket in the post-2015 period.

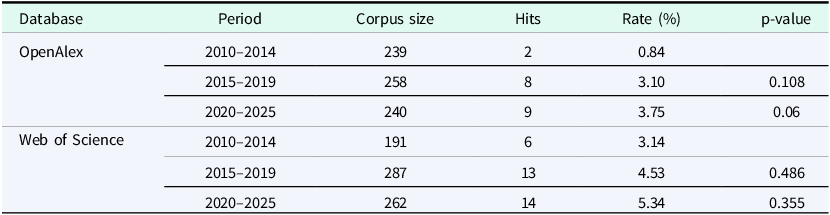

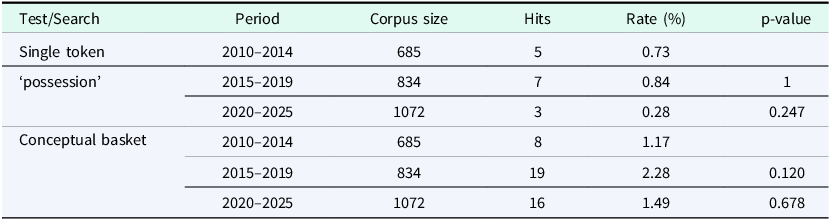

This broader analysis, shown in Table 3, presents a nuanced picture. The data from OpenAlex provide a potential indicator of a delayed increase in the discussion of these de facto concepts. While the immediate post-debate period shows no significant change (p = 0.108), the p-value for the later 2020–2025 period falls to 0.06. This marginal p-value could be interpreted as a weak signal of a slow-burning adoption. However, this finding must be treated with extreme caution, as it is generated from an analytically fragile baseline of only two hits. A change in absolute numbers from 2 hits (in the baseline) to 9 hits (in the later period) is highly susceptible to small-sample effects and cannot, on its own, be considered a robust indicator. Given this ambiguity, we turn to the WoS dataset to complete the picture and see if this potential trend is replicated. The WoS data, by contrast, show no such signal. It returns a globally null result across all periods. While the rate trends slightly upwards from a 3.14% baseline to 5.34% in the later period, the corresponding p-value of 0.355 is far from statistical significance and confirms this fluctuation is indistinguishable from random noise.

Table 3. Frequency of conceptual keyword basket in articles on ‘property rights’, by period

We are thus left with two key elements: a single, statistically fragile signal (p = 0.06) in one dataset, which is directly contradicted by a null result (p = 0.355) in the other. Given that the potential trend is not replicated, the most robust conclusion is that the ‘general salience’ hypothesis is not supported by the evidence. This finding holds even on a broader scale. A robustness check (Appendix B), which replicates this analysis on the entire WoS ‘Economics’ category, confirms our main finding and shows no significant, profession-wide lexical shift.

Discussion

The bibliometric analysis in Section 2 reveals a stark disconnect: the 2015 debate has a sustained and significant intellectual footprint, yet this engagement did not translate into the lexical shift advocated by its proponents. This divergence invites a few plausible interpretations regarding how the profession has processed this exchange.

First, a straightforward explanation is that the EAPR’s defenders were simply persuasive. The profession may have engaged with the critique, cited it, but ultimately concluded that the EAPR’s existing terminology (e.g., ‘economic property rights’) was analytically sufficient for standard modelling, rendering a shift to ‘possession’ unnecessary. This would explain both the high citation counts (as a marker of engagement) and the null result for lexical adoption.

A second, more nuanced reading is that scholars may have ‘split the difference’. It is possible that the profession effectively separated the debate’s two components: embracing the deep conceptual challenge while simultaneously dismissing the specific terminological solution. Researchers may be citing the debate – and Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a) in particular – for its theoretical claims regarding the non-instrumental role of law and legitimacy, while remaining unpersuaded that ‘possession’ is the correct lexical fix. If scholars are citing the debate for its theoretical contribution but treating the terminological dispute as, in Allen (Reference Allen2015)’s words, a matter of ‘semantics and focus’, this would generate precisely the results found in our analysis: high citations alongside a flat, statistically insignificant lexical trend.

Why, then, has the profession resisted this specific lexical shift? While intellectual path-dependency and the coordination costs of altering established terminology undoubtedly play a role, another reason may lie in the legal complexity of the term ‘possession’ itself. As critics have noted, ‘possession’ is not merely a ‘brute fact’ of physical control; it is often a distinct legal term of art entailing specific rights (e.g., the legal right to possess versus actual physical custody). By seeking to reserve ‘property’ strictly for de jure rights, the proposed distinction risks oversimplifying ‘possession’ into a purely pre-legal category – a binary that legal scholars and institutionalists may find analytically insufficient. Furthermore, the existing terminology of ‘economic property rights’ may successfully capture the functional choice set that drives economic modelling. If the profession perceives the current ‘bundle of rights’ metaphor as flexible enough to accommodate both legal and non-legal constraints, the perceived analytical benefits of adopting a stricter legal vocabulary likely fail to outweigh the transaction costs of the switch.

Finally, a methodological boundary must be acknowledged. While abstract-level searches serve as a robust proxy for the profession’s core, codified vocabulary, this approach may naturally undercount incidental usage of these terms within the full text of articles.

Conclusion

A decade on, the legacy of the 2015 JOIE debate on property and possession is marked by a clear divergence. Our citation analysis confirms the exchange was not ignored; it has garnered significant and sustained scholarly attention, demonstrating its enduring relevance.

This intellectual engagement, however, did not translate into the clear lexical shift this Comment sought to test. Our text-mining analysis of 58 economics journals found that the specific terminological critique – the call to adopt ‘possession’ – was unsuccessful, as its use remains negligible. Our broader test for a ‘conceptual basket’ of related de facto terms yielded ambiguous results: a marginal, statistically fragile signal in one dataset was directly contradicted by a null result in another. This ambiguity suggests that if any lexical adoption occurred, it was not a broad, profession-wide shift. However, it should be noted that, as this commentary focused strictly on measuring lexical adoption, these results do not constitute evidence that the deeper conceptual distinction suggested by Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a) has been ignored.

The 2015 JOIE debate

Few concepts are as central to institutional economics as property rights, yet few have proven as conceptually contentious. A decade ago, the pages of this journal hosted a debate focused on the distinction between property and possession (Journal of Institutional Economics, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2015). The exchange pitted two fundamentally different interpretations against one another.

The critique. The debate’s catalyst was Hodgson’s (Reference Hodgson2015a) charge that the mainstream ‘economic approach to property rights’ (EAPR) conflates property with possession.Footnote 1 For Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a), possession is a pre-legal, de facto control over a resource – a physical relationship between a person and a thing. Property, by contrast, is a de jure social relationship, not a person-thing relationship, requiring legally sanctioned, enforceable rights that depend on a third-party legitimating authority (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2015a). Hodgson argued that the EAPR’s terminology – specifically its use of the term ‘economic property right’ to describe what is merely de facto control – is deeply misleading. A ‘right’, he insists, implies a legitimate claim enforceable in a court of law; for instance, a thief’s possession of stolen goods does not constitute a ‘right’, even if their control is effective (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2015a, b). Cole (Reference Cole2015) strongly supports this critique. Citing John Searle, he argues that possession is a ‘brute fact’ about the world, whereas property is an ‘institutional fact’ requiring collective intentionality and acceptance. This reliance on collective intentionality, rather than strictly on state enforcement, is a key clarification. It widens the conceptual lens to accommodate non-state (e.g., Ostromian) common-property regimes as valid, institutionalized systems.

The EAPR defense. Allen (Reference Allen2015) and Barzel (Reference Barzel2015) defended the EAPR’s framework, contending the dispute was primarily a matter of ‘semantics and focus’ Allen (Reference Allen2015, p. 711). They argued that the EAPR does not conflate the two concepts but, in fact, explicitly distinguishes between them using its own terminology: ‘legal property rights’ (what Hodgson calls property) and ‘economic property rights’ (what Hodgson calls possession) (Allen, Reference Allen2015; Barzel, Reference Barzel2015). For the EAPR, this distinction is the very foundation of its analysis. Allen (Reference Allen2015) argued that in a hypothetical world of zero transaction costs (no costs associated with establishing and maintaining rights), legal property rights and economic property rights would be identical. In the real world, however, transaction costs are always positive. This creates an inevitable gap between the law on the books (legal rights) and an individual’s actual, operational choice set (economic rights). Behaviour, they insist, is driven by this de facto reality, making ‘economic rights’ the proper focus for a positive science aiming to explain behaviour.

The methodological and behavioural divides. In his rejoinder, Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015b) forcefully rejected the ‘mere semantics’ defense. Citing the Humpty Dumpty dialogue from Alice Through the Looking Glass, he argued against philosophical nominalism (the idea that words mean whatever the user chooses). He contended that arbitrarily redefining a foundational legal term like ‘right’ (which implies legitimacy) to mean ‘possession’ (de facto control) is not analytically neutral; it is misleading and has negative consequences, especially for interdisciplinary dialogues with law (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2015b). Furthermore, this exposed a deep behavioural divide over modelling human action. Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a) argued that the EAPR’s focus on individuals maximizing their ‘economic rights’ treats law as a purely instrumental constraint. This, he charged, ignores evidence from psychology that individuals are often motivated non-instrumentally by the perceived legitimacy of the law and a moral, deontic duty to obey per se.Footnote 2 Allen (Reference Allen2015) countered that this confuses ‘motivation’ (which is always maximization) with ‘objectives’, and that moral sentiments can simply be included as an element in the utility function. Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015b) rejoined that this attempt to ‘subsume’ morality under a general utility calculus obscures its distinctive, non-instrumental character as a driver of action.

Thus, the 2015 exchange hosted two distinct debates simultaneously: (i) a terminological debate over the analytic utility of the EAPR’s lexicon versus the call to adopt ‘possession’, and (ii) a deeper conceptual debate on the proper modelling of human action and the role of law, morals, and legitimacy. This Comment deliberately isolates the first of these debates for one critical reason: it is empirically testable. While the deeper conceptual debate is of profound importance, its impact is diffuse and difficult to measure. In contrast, the terminological question – whether the profession’s working vocabulary shifted – offers an observable hypothesis. We mainly limit our analysis to this measurable lexical adoption within 58 English-language journals, bracketing the more complex question of conceptual influence. The remainder of this article proceeds as follows: Section 2 details our dual bibliometric methodology: it first presents a citation analysis to measure the visibility and evolution of the 2015 debate, followed by a multi-database text-mining analysis (Web of Science and OpenAlex) to test for the adoption of the term ‘possession’ and a broader conceptual basket of de facto keywords. Section 3 discusses the findings, offering interpretations for the disconnect between the debate’s sustained scholarly visibility and the statistically non-significant lexical shift observed in the data. Finally, Section 4 concludes by assessing the dual legacy of the exchange ten years on.

The debate’s intellectual footprint: a bibliometric analysis

This section employs two bibliometric methods: a citation analysis to assess both the static visibility and the dynamic evolution of scholarly engagement with the debate, and a text-mining analysis to determine if this engagement led to a shift in the profession’s working vocabulary.

The number of citations

While citation counts are an imperfect proxy for intellectual impact – as they do not distinguish among positive, negative, or passing references – they provide a useful approximation of the attention an academic work has received. If the debate was truly a ‘merely semantic’ issue, one might expect it to have faded into obscurity with minimal citations. Conversely, significant citation counts would suggest that the arguments raised have been actively engaged with by the academic community.

Table 1 presents the citation data for the five articles that constituted the debate, collected from Google Scholar, CrossRef, OpenAlex, and Web of Science (WoS).Footnote 3

Table 1. Citation counts for the 2015 JOIE debate articles

Source: Google Scholar, CrossRef, OpenAlex, and Web of Science data retrieved on 27 October 2025. Note that databases differ in coverage: Web of Science and CrossRef are selective, while OpenAlex and Google Scholar index a broader range of content (e.g., preprints, working papers), which results in higher counts. CrossRef data are as displayed on the JOIE website. Numbers in parentheses exclude self-citations.

The data reveal several notable patterns. The first feature is the prominence of Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a)’s lead article, which has garnered substantially more citations than the four responses combined across all platforms. This is not unexpected; as the paper that initiated the exchange, it serves as the natural focal point for any subsequent discussion. Its high citation count confirms that Hodgson’s critique was, at the very least, not ignored. Among the responses, Barzel (Reference Barzel2015)’s comment stands out with the highest number of citations, followed by the articles from Cole (Reference Cole2015) and Allen (Reference Allen2015), which have received a similar level of attention.

The line graph in Figure 1 provides a dynamic perspective that complements the static totals in Table 1. These data were generated via programmatic queries to the OpenAlex database, tracking the annual count of unique works citing the symposium. The top line captures any article citing at least one of the five papers, identifying a broad audience of 225 unique works in total. The bottom dashed line serves as a more conservative proxy for direct engagement with the debate itself, tracking articles that co-cite at least two of the papers; a collection of 51 unique works has been identified.

Figure 1. Annual count of articles citing the 2015 JOIE symposium. Note: OpenAlex dataset. Counts represent unique articles. Duplicates were removed to ensure one record per article. ‘Citing at least 1 article’ refers to articles that cite at least one paper from the 2015 JOIE symposium; ‘Citing at least 2 articles’ refers to those citing two or more papers. Values for 2025 are partial, based on records available as of 4 November 2025. Note that the apparent spike in 2025 is largely a methodological artefact resulting from OpenAlex indexing separate chapters from a single book as individual citing works.

Both measures show that scholarly interest was not confined to the years immediately following the exchange but has been remarkably sustained. Notably, both general citations and specific co-citations peaked significantly in 2019–2020, five years after the debate’s publication.Footnote 4 The sustained, parallel trend of both broad citations and specific co-citations strongly suggests that the debate has had an enduring legacy, and that its core questions have remained a live issue for scholars. The apparent spike in 2025 visible in the top line is largely a methodological artefact.Footnote 5

Lexical adoption: from a single term to a conceptual basket

To test whether the debate’s engagement translated into a shift in the profession’s working vocabulary, I first compiled a corpus of academic articles by searching for the exact phrase ‘property rights’ in the title or abstract of 58 selected economics journals. This list, detailed in Appendix A, is based on (most of) the IDEAS/RePEc top 50 supplemented with relevant specialist publications. This corpus was split into three periods: a pre-debate baseline (2010-2014), an immediate post-debate period (2015–2019), and a later period (2020–2025). The first post-debate period intentionally begins with 2015, the year the symposium was published, to capture any immediate lexical response. The entire corpus was then analysed using two distinct databases: WoS and OpenAlex.Footnote 6

First, I measure the frequency of the single, specific term ‘possession’ advocated by Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a).

The results for the single-token test, presented in Table 2, indicate that the term ‘possession’ is extremely rare in the abstracts of the core property rights literature. The data from WoS are particularly striking: the rate of use shows no statistically significant change. While the percentage fluctuated slightly from a baseline of 1.57% (3 hits) to 1.39% (4 hits) in the immediate post-debate period, this difference is statistically indistinguishable from zero, yielding a p-value of 1.000. The OpenAlex data, while showing a larger relative increase (from 0.42% to 1.56%), is similarly statistically insignificant (p = 0.374). Furthermore, this apparent ‘increase’ is driven by a change in absolute numbers from only one hit to four, making it far too small to suggest any meaningful analytical trend. The core conclusion from both databases is identical: the specific term ‘possession’ was not adopted, and its use remained negligible post-2015.

Table 2. Frequency of ‘possession’ in articles on ‘property rights’, by period

Note: Data retrieved on 5 November 2025. The analysis is conducted over 58 journals. ‘Corpus Size’ = articles containing ‘property rights’ in title or abstract. ‘Hits’ = articles from that corpus also containing ‘possession’ in their abstract. We applied tokenization at the word level. Data were queried for titles and abstracts separately and then combined. Duplicates were removed to ensure one record per article. ‘Rate (%)’ = (Hits/Corpus Size) * 100. The p-value is from a Fisher’s Exact Test comparing the period’s proportion to the 2010–2014 baseline. Data for 2025 are partial.

A test limited to the single-token ‘possession’ risks a false negative. While our data show that this specific term was not adopted, the 2015 debate may have had a broader impact. The debate itself may have served as a consciousness-raising event. It could have prompted economists, regardless of which side they found more persuasive, to be more explicit and frequent in their discussion of the de facto versus de jure distinction. To test this ‘general salience’ hypothesis, a second analysis was designed. This test searches the ‘property rights’ corpus for a broad ‘conceptual basket’ of keywords associated with the de facto/de jure separation. Critically, this basket includes terms from both the critique (‘possession’, ‘possessory’, ‘de facto control’) and the EAPR’s existing lexicon (‘economic property rights’, ‘hold rights’, ‘use rights’, ‘economic rights’). If the 2015 debate successfully increased the profession’s general preoccupation with this distinction, we would expect to see a statistically significant rise in the frequency of this combined basket in the post-2015 period.

This broader analysis, shown in Table 3, presents a nuanced picture. The data from OpenAlex provide a potential indicator of a delayed increase in the discussion of these de facto concepts. While the immediate post-debate period shows no significant change (p = 0.108), the p-value for the later 2020–2025 period falls to 0.06. This marginal p-value could be interpreted as a weak signal of a slow-burning adoption. However, this finding must be treated with extreme caution, as it is generated from an analytically fragile baseline of only two hits. A change in absolute numbers from 2 hits (in the baseline) to 9 hits (in the later period) is highly susceptible to small-sample effects and cannot, on its own, be considered a robust indicator. Given this ambiguity, we turn to the WoS dataset to complete the picture and see if this potential trend is replicated. The WoS data, by contrast, show no such signal. It returns a globally null result across all periods. While the rate trends slightly upwards from a 3.14% baseline to 5.34% in the later period, the corresponding p-value of 0.355 is far from statistical significance and confirms this fluctuation is indistinguishable from random noise.

Table 3. Frequency of conceptual keyword basket in articles on ‘property rights’, by period

Note: Data retrieved on 5 November 2025. The analysis is conducted over 58 journals. ‘Hits’ = articles in the ‘property rights’ corpus also containing at least one term from the keyword basket: ‘possession’, ‘possessory’, ‘de facto control’, ‘economic property rights’, ‘hold rights’, ‘use rights’, or ‘economic rights’. We applied tokenization at the word level. Data were queried for titles and abstracts separately and then combined. Duplicates were removed to ensure one record per article. ‘Rate (%)’ = (Hits/Corpus Size) * 100. The p-value is from a Fisher’s Exact Test comparing the period’s proportion to the 2010–2014 baseline. Data for 2025 are partial.

We are thus left with two key elements: a single, statistically fragile signal (p = 0.06) in one dataset, which is directly contradicted by a null result (p = 0.355) in the other. Given that the potential trend is not replicated, the most robust conclusion is that the ‘general salience’ hypothesis is not supported by the evidence. This finding holds even on a broader scale. A robustness check (Appendix B), which replicates this analysis on the entire WoS ‘Economics’ category, confirms our main finding and shows no significant, profession-wide lexical shift.

Discussion

The bibliometric analysis in Section 2 reveals a stark disconnect: the 2015 debate has a sustained and significant intellectual footprint, yet this engagement did not translate into the lexical shift advocated by its proponents. This divergence invites a few plausible interpretations regarding how the profession has processed this exchange.

First, a straightforward explanation is that the EAPR’s defenders were simply persuasive. The profession may have engaged with the critique, cited it, but ultimately concluded that the EAPR’s existing terminology (e.g., ‘economic property rights’) was analytically sufficient for standard modelling, rendering a shift to ‘possession’ unnecessary. This would explain both the high citation counts (as a marker of engagement) and the null result for lexical adoption.

A second, more nuanced reading is that scholars may have ‘split the difference’. It is possible that the profession effectively separated the debate’s two components: embracing the deep conceptual challenge while simultaneously dismissing the specific terminological solution. Researchers may be citing the debate – and Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a) in particular – for its theoretical claims regarding the non-instrumental role of law and legitimacy, while remaining unpersuaded that ‘possession’ is the correct lexical fix. If scholars are citing the debate for its theoretical contribution but treating the terminological dispute as, in Allen (Reference Allen2015)’s words, a matter of ‘semantics and focus’, this would generate precisely the results found in our analysis: high citations alongside a flat, statistically insignificant lexical trend.

Why, then, has the profession resisted this specific lexical shift? While intellectual path-dependency and the coordination costs of altering established terminology undoubtedly play a role, another reason may lie in the legal complexity of the term ‘possession’ itself. As critics have noted, ‘possession’ is not merely a ‘brute fact’ of physical control; it is often a distinct legal term of art entailing specific rights (e.g., the legal right to possess versus actual physical custody). By seeking to reserve ‘property’ strictly for de jure rights, the proposed distinction risks oversimplifying ‘possession’ into a purely pre-legal category – a binary that legal scholars and institutionalists may find analytically insufficient. Furthermore, the existing terminology of ‘economic property rights’ may successfully capture the functional choice set that drives economic modelling. If the profession perceives the current ‘bundle of rights’ metaphor as flexible enough to accommodate both legal and non-legal constraints, the perceived analytical benefits of adopting a stricter legal vocabulary likely fail to outweigh the transaction costs of the switch.

Finally, a methodological boundary must be acknowledged. While abstract-level searches serve as a robust proxy for the profession’s core, codified vocabulary, this approach may naturally undercount incidental usage of these terms within the full text of articles.

Conclusion

A decade on, the legacy of the 2015 JOIE debate on property and possession is marked by a clear divergence. Our citation analysis confirms the exchange was not ignored; it has garnered significant and sustained scholarly attention, demonstrating its enduring relevance.

This intellectual engagement, however, did not translate into the clear lexical shift this Comment sought to test. Our text-mining analysis of 58 economics journals found that the specific terminological critique – the call to adopt ‘possession’ – was unsuccessful, as its use remains negligible. Our broader test for a ‘conceptual basket’ of related de facto terms yielded ambiguous results: a marginal, statistically fragile signal in one dataset was directly contradicted by a null result in another. This ambiguity suggests that if any lexical adoption occurred, it was not a broad, profession-wide shift. However, it should be noted that, as this commentary focused strictly on measuring lexical adoption, these results do not constitute evidence that the deeper conceptual distinction suggested by Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015a) has been ignored.

Data availability statement

This study’s empirical analysis relies on data from several bibliographic sources. Data from Google Scholar, CrossRef, and Web of Science were retrieved manually via their respective web interfaces on the dates specified in the text and tables. The analysis of OpenAlex data was conducted programmatically. These analyses were conducted using R version 4.5.0. and the openalexR package version 2.0.2. To ensure full transparency and reproducibility, the online appendix – which includes the complete list of DOIs for the retrieved articles and all R scripts used for data retrieval and analysis – is hosted on the Open Science Framework (OSF) platform: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/H36BY.

Acknowledgements

This work stems from an interest in this debate that dates back to my doctoral thesis. I wish to thank Miléna Spach for her careful reading of every iteration of this manuscript. I am also grateful to Laurent Garnier for his support with the Web of Science data extraction, and to Ondine Berland for her feedback on an earlier draft. Finally, I thank the editor and five reviewers for their constructive comments, which significantly shaped the final version of this paper. All remaining errors are mine.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, I used Google’s Gemini AI for assistance with two tasks: (1) to improve the grammar, clarity, and readability of the English prose, and (2) to refine and optimise the R code used for the bibliometric analysis. After using this tool, I reviewed and edited all content in detail and take full responsibility for the entirety of the published article, including the final text and the accuracy of the code.

Appendix A. List of journals included in the text-mining analysis

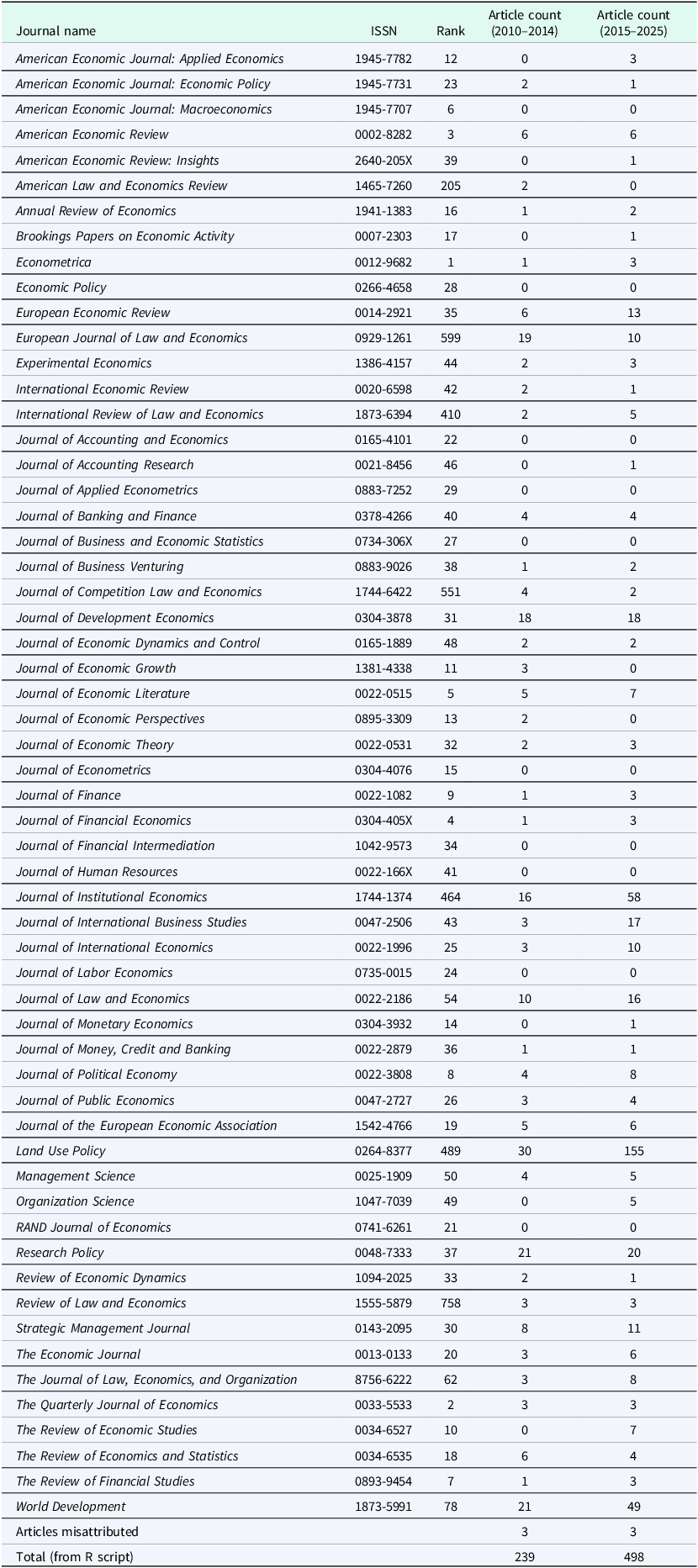

The selection of journals for this analysis was designed to capture the discourse within the mainstream of the economics profession while ensuring thematic relevance. The foundation of our list consists of the top 50 journals based on the aggregate rankings provided by IDEAS/RePEc (https://ideas.repec.org/top/top.journals.all.html). From this list, two sources – the Proceedings of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (Rank 45) and the Proceedings of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.) (Rank 47) – were excluded due to data retrieval issues or format incompatibility with our text-mining approach. This leaves 48 journals from the recognized Top 50.

To this core group, we added ten specialist journals. These include the Journal of Institutional Economics (JOIE, Rank 464), the venue of the original debate, and nine other journals focusing on law and economics, development economics, or land use policy were incorporated. These additions, ranked outside the Top 50 by IDEAS/RePEc, were selected as these fields are potentially more sensitive to the 2015 debate. The final corpus for our query thus comprises 58 journals, listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Journal corpus for text-mining analysis with IDEAS/RePEc Rank

Note: Ranks are from the IDEAS/RePEc aggregate journal rankings (retrieved on 28 October 2025). ‘Article Count’ refers to the total number of articles containing the exact phrase ‘property rights’ in their title or abstract within the specified period. Article count data were retrieved from OpenAlex (6 November 2025). The ‘Articles misattributed’ line accounts for articles that were correctly found by their ISSN in the 58-journal corpus but were grouped by the R script under a non-target source (e.g., SSRN, AgEcon Search). This occurs when OpenAlex lists a preprint server or repository as the ‘primary_location’ for that work. The final ‘Total’ line reflects the complete, de-duplicated corpus size as reported by the R script.

Appendix B. Extending the lexical search to the WoS ‘Economics’ category

The main analysis in Section 2.2 deliberately used a targeted corpus of 58 journals to test for lexical adoption among the profession’s most relevant publications. A potential critique of this approach is that it might miss a broader, more diffuse shift occurring in the wider profession.

To address this, this appendix serves as a robustness check by replicating the analysis (for both the single-token ‘possession’ and the full ‘conceptual basket’) on the entire ‘Economics’ category within the WoS database.Footnote 7 This WoS category is a broad, curated classification used by Clarivate, containing several hundred peer-reviewed journals spanning all major sub-disciplines.

Table 5. Lexical frequency in articles on ‘property rights’ in the full ‘Economics’ WoS category

Note: Data retrieved on 7 November 2025. The analysis is conducted over the entire ‘Economics’ WoS category. ‘Corpus Size’ = articles containing ‘property rights’ in title or abstract. ‘Hits’ = articles from that corpus also containing the relevant search term(s) in their abstract. The conceptual basket (Test 2) contains: ‘possession’, ‘possessory’, ‘de facto control’, ‘economic property rights’, ‘hold rights’, ‘use rights’, or ‘economic rights’. ‘Rate (%)’ = (Hits/Corpus Size) * 100. The p-value is from a Fisher’s Exact Test comparing the period’s proportion to the 2010–2014 baseline. Data for 2025 are partial.

This broad-based analysis confirms our main findings. The specific term ‘possession’ was not adopted by the wider profession. The ‘conceptual basket’ test reinforces our main analysis, showing no increase in uses in the immediate post-debate period (p = 0.120), a null result that was sustained in the later period (p = 0.678). This confirms our 58-journal sample was not misleading and that the 2015 JOIE debate did not lead to a significant, profession-wide lexical shift.