Introduction

Polynoids are the largest family of scaleworms including more than 170 genera and 900 species (Hourdez, Reference Hourdez, Purschke, M and Westheide2021). Their body is covered dorsally by a series of paired scale-like organs, or elytra, that protect the body, and generate a rather closed chamber for respiration, and in some cases for carrying embrios. The classification of the polynoids relies on the arrangement of the cephalic appendages, elytra ornamentation, and parapodial and chaetae features. However, these features are fragile, and the polynoids suffer the detachment of elytra, which often complicates their identification, even if they were collected in shallow water. These issues are exacerbated in specimens collected by dredging or trawling in deeper substrates. Nevertheless, the taxonomic treatment of deep-water polynoids has been progressively refined since M’Intosh (Reference M’Intosh1885), such that distinct body patterns are recognized after their cephalic appendages, elytra, parapodia and chaetae features.

HALIPRO 2 was an oceanographic cruise carried out by New Caledonia and New Zealand in 1996 (Grandperrin et al., Reference Grandperrin, Farman, Lorance, Jomessy, Hamel, Laboute, Labrosse, Richer de Forges, Seret and Virly1997), for assessing fisheries resources in seamounts along the Norfolk and Loyalty Ridges. The New Zealand research vessel, Tangaroa, was designed for studying deep-sea resources, and used an Orange Roughy bottom trawl, having a bag screen 100 mm wide in the end, and 40 mm wide in the external bag sides (Grandperrin et al., Reference Grandperrin, Farman, Lorance, Jomessy, Hamel, Laboute, Labrosse, Richer de Forges, Seret and Virly1997: 11).

There were 17 scientists on board led by R. Grandperrin, and they made 106 hauls, resulting in 275 species of 101 families, including 42 different shark and ray species. The invertebrates were treated by B. Richer de Forges (Grandperrin et al., Reference Grandperrin, Farman, Lorance, Jomessy, Hamel, Laboute, Labrosse, Richer de Forges, Seret and Virly1997: 10, 96), annelid polychaetes were fixed with a 10% formalin solution (Grandperrin et al., Reference Grandperrin, Farman, Lorance, Jomessy, Hamel, Laboute, Labrosse, Richer de Forges, Seret and Virly1997: 15), and there were 17 lots with polychaetes collected (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo1999: 36), but only one lot had two polynoid specimens, one with a parasitic copepod collected at station BT94.

In station BT94 the trawl lapsed 64 min, sampling an area of 0.17 km2 and collected 165 kg, of which 156 kg were made up by fishes (Grandperrin et al., Reference Grandperrin, Farman, Lorance, Jomessy, Hamel, Laboute, Labrosse, Richer de Forges, Seret and Virly1997: 63); there were 240 specimens of 26 fish species, and the most abundant species was the cosmopolitan splendid alfonsino, Beryx splendens Lowe (Reference Lowe1834).

It is remarkable that after such a long haul, two polynoids were recovered from station BT94. They are regarded as belonging to a new genus and a new species and are described below, including a modification for a recent key to identify similar polynoid genera. Further, one of the specimens had a parasitic copepod, and it is also described below.

Material and methods

Polynoid polychaetes features were analysed in stereo- and compound microscopes. Specimens were temporarily stained with Shirlastain-A or Methyl green for improving visibility of some morphological features, and this is shown in the figures. Two parapodia and elytra were removed for observing finer details in compound microscopes. Series of digital photos corresponding to successive focal planes were stacked with HeliconFocus 8, and plates were arranged with PaintShop Pro 2021.

Results

Class Polychaeta Grube (Reference Grube1850)

Order Phyllodocida Dales (Reference Dales1962)

Suborder Aphroditiformia Levinsen (Reference Levinsen1883)

Family Polynoidae Kinberg (Reference Kinberg1856)

Subfamily Polynoinae Kinberg (Reference Kinberg1856)

Jimipolyeunoa gen. n.

[urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act: E9440D52-B52A-456F-A823-9752DD1F81ED]

Type species

Jimipolyeunoa richeri sp. n.

Etymology

The generic name is a free combination of the last name of Dr. Naoto Jimi, from the Nagoya University, Japan, and the name for the stem genus, Polyeunoa M’Intosh (Reference M’Intosh1885). It is an homage to the impressive productive academic life of our colleague, and especially in recognition of his recent publications on scale worms.

Diagnosis

Polynoin with body long, with over 50 segments. Elytra more than 15 pairs on segments 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23 … Prostomium without cephalic peaks; anterior eyes displaced posteriorly. Notopodia with tapered acicular lobe; neuropodia with elongate acicular lobe, tip extended into a supracicular process. Notochaetae terete, few, as stout as neurochaetae, blunt, finely spinulose. Neurochaetae numerous, oar-shaped, with tips unidentate or finely bidentate.

Remarks

Jimipolyeunoa gen. n. resembles Parapolyeunoa Barnich et al., (Reference Barnich, Gambi and Fiege2012) by having neuracicular lobes extended as supracicular processes, and notochaetae terete, finely spinulose. They differ in prostomial and chaetal features, which are usually employed for separating similar polynoin genera (Barnich et al., Reference Barnich, Gambi and Fiege2012; Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2024). In Jimipolyeunoa the prostomium lacks cephalic peaks, has anterior eyes displaced posteriorly, and its neurochaetae are unidentate or finely bidentate, whereas in Parapolyeunoa there are distinctive cephalic peaks in prostomial anterior margins, the anterior eyes are in the widest prostomial area, and neurochaetae are clearly bidentate. A recently published key (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2024: 442) has been modified for including the new genus and it is included below.

Gender

Masculine. M’Intosh (Reference M’Intosh1885: 76) proposed Polyeunoa with P. laevis as its single species. The adjective means smooth, and it is masculine (laeve, feminine; also used as levis (m.), leve (f.) after Brown 1954: 474). This implies that the genus name was regarded as masculine, even though Eunoe is the name of a nymph. As an extension, the new name is also regarded as masculine.

Composition

Only includes the type species, Jimipolyeunoa richeri sp. n.

Key to some polymeric polynoin genera

(modified after Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2024)

1. Notopodia with notochaetae; lateral antennal sheats short, or missing; tentacular segment sometimes with chaetae; neurochaetae variable …………………………………………… 2

– Notopodia without notochaetae; lateral antennae with long sheats; tentacular segment achaetous; neurochaetae basally cylindrical, distally depressed, tip sharp … Bathyadmetella Pettibone, 1967

2. (1) Notochaetae of a single type ……………………………… 3

– Notochaetae of two types …………………………………… 17

3. (2) Notochaetae thinner than neurochaetae ………………… 4

– Notochaetae as coarse as, or thicker than neurochaetae ………………………………………………………………… 6

4. (3) Cirrigerous segments with dorsal tubercles T-shaped; neurochaetae falcate, tips unidentate …… Acholoe Claparède, 1870

– Cirrigerous segments with dorsal tubercles nodular or bulbous; neurochaetae variable ………………………………………… 5

5. (4) Notochaetae short, blunt; neurochaetae of one type, with tips falcate, entire …………… Parahololepidella Pettibone, 1969

– Notochaetae long, tapering; neurochaetae of two types, falcate spinulose, and falcate denticulate ………… Enipo Malmgren, 1866

6. (3) Neuracicular lobe extending as supracicular process; notochaetae blunt, spinulose ……………………………… 7

– Neuracicular lobe not extending as supracicular process; notochaetae blunt or tapered, smooth or spinulose ………… 9

7. (6) Elytra finely fimbriate; neurochaetae with tips unidentate …………………………………… Neopolynoe Loshamn (Reference Loshamn1981)

– Elytral margins smooth, non-fimbriate; neurochaetae variable ………………………………………………………… 8

8. (7) Prostomium with cephalic peaks distinct; neurochaetae all clearly bidentate ……… Parapolyeunoa Barnich et al. (Reference Barnich, Gambi and Fiege2012)

– Prostomium without cephalic peaks; neurochaetae unidentate and finely bidentate …………………… Jimipolyeunoa gen. n.

9. (6) Tentacular segment with chaetae; facial tubercle present ……………………………………………………………… 10

– Tentacular segment without chaetae; facial tubercle present or absent ………………………………………………………… 12

10. (9) Palps smooth (homogeneously papillate) ……………… 11

– Palps with series of papillae; acicular lobes very long; noto- and neurochaetae of similar length ……… Eulagisca M’Intosh (Reference M’Intosh1885)

11. (10) Acicular lobes very long, filiform; notochaetae as long as, or longer than neurochaetae, tapered; neurochaetae with long smooth distal region, tip falcate, unidentate …………………………… Barnichia Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2024)

– Acicular lobes long, subtriangular; notochaetae shorter than neurochaetae, blunt; neurochaetae without smooth distal region, tip blunt or delicately bidentate … Neohololepidella Pettibone, 1969

12. (9) Prostomium with short antennal scales or sheats; with facial tubercle ………………… Admetella M’Intosh (Reference M’Intosh1885)

– Prostomium without antennal scales or sheats; without facial tubercle ………………………………………………………… 13

13. (12) Neurochaetae with long smooth distal region, tips variable ……………………………………………………… 14

– Neurochaetae with short smooth distal region, tips uni- or bidentate ………………………………… Intoshella Darboux, 1899

14. (13) Notochaetae of a single type ……………………… 15

– Notochaetae of two types …………………………………… 16

15. (14) Notochaetae slightly falcate, finely denticulate; neurochaetae of a single type, unidentate ……………………………… Hololepidella Willey, 1905

– Notochaetae smooth capillaries; neurochaetae of two types: longer finely spinulose, and shorter with few denticles, tips unidentate ……………………………… Pararctonoella Pettibone, 1996

16. Notopodial acicular lobe almost as long as neuropodial one; notochaetae short, subdistally swollen, smooth, and tapered; neurochaetae unidentate, or bidentate with tiny secondary tooth ………………………… Polyeunoa M’Intosh (Reference M’Intosh1885)

– Notopodial acicular lobe markedly shorter than neuropodial one; notochaetae short blunt, almost smooth, and long spinulose; neurochaetae unidentate …… Arctonoella Buzhinskaja, 1967

17. (2) All notochaetae tapered …………………………… 18

– Notochaetae blunt, terete, and tapered denticulate; neurochaetae falcate spinulose, with tips uni- or bidentate …………………………… Polynoe Savigny in Lamarck, 1818

18. (17) All notochaetae spinulose, shorter falcate, longer tapered …………………………… Grubeopolynoe Pettibone, 1969

– Notochaetae smooth straight, or spinulose straight or falcate …………………………………… Pareulagisca Pettibone, 1997

Jimipolyeunoa richeri sp. N.

Figure 1. Jimipolyeunoa richeri gen. n., sp. n., holotype (MNHN IA 2000-2121). (A) complete, bent ventrally, dorsal view; (B) anterior end, dorsal view, after Shirlastain-A staining; (C) chaetigers 17–20, left parapodia, dorsal view with small oocytes released, after Methyl-green staining; (D) chaetiger 15, right parapodium, posterior view (inset: neurochaeta tip); (E) chaetiger 29, right parapodium, posterior view (inset: neuracicular lobe with supracicular process); (F) chaetiger 15, tips of upper and lower neurochaetae (inset: tip of upper neurochaeta); (G) two median detached eltyra, damaged during unrolling, posterior and inner margins bent dorsally; (H) paratype (ECOSUR 323), anterior region, dorsal view, after Methyl-green staining. Scale bars: A, 2.7 mm; B, C, G, 0.5 mm; D, E, 0.3 mm; F, 40 µm; H, 0.7 mm.

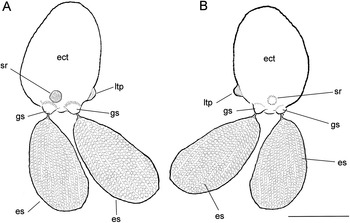

Figure 2. Jimipolyeunoa richeri gen. n., sp. n., paratype (ECOSUR 323). (A) anterior fragment, ventral view, with Herpyllobius pleurotumoris sp. n., holotype, attached in anterior region; (B) same, after Methyl green staining, anterior region, ventral view with structures of the parasite (es= egg sac, ect = ectosoma, gs = genital swelling, ltp = lateral tumour-like process, sr = sclerotized ring); (C) same, parasite ectosome and egg masses. Scale bars: A, 1.6 mm; B, 0.6 mm; C, 0.5 mm.

[urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act: 60AF2213-DB5F-4956-8E7B-A5132AEE25CF]

Type material

New Caledonia. Holotype (MNHN IA 2000-2121), and paratype (ECOSUR 323), Campagne HALIPRO 2, Sta. BT94 (23°36.97´ S, 167°41.66´ E to 23°33.48´ S, 167°42.39´ E), 448–880 m, 24 Nov. 1996 (data from Grandperrin et al., Reference Grandperrin, Farman, Lorance, Jomessy, Hamel, Laboute, Labrosse, Richer de Forges, Seret and Virly1997).

Etymology

The specific epithet is derived after Dr. Bertrand Richer de Forges, ORSTOM, Nouméa, New Caledonia, in recognition of his leading efforts in many expeditions in New Caledonia, and especially because he participated in the Campagne Halipro 2, which collected the specimens which were used for proposing the new genus and describing two new species, including the polynoid species named after him.

Diagnosis

Jimipolyeunoa with elytra with innervation, without macro- or microtubercles.

Type locality

100 km off South of Vao, New Caledonia, in 448–880 m depth.

Description

Holotype (MNHN IA 2000-2121), pale, markedly bent ventrally, complete, mature female; pharynx slightly darker, markedly bent ventrally (Figure 1A); many prostomial, body appendages and most elytra detached, now lost; most segments with numerous oocytes in parapodial spaces, body surface with recently released oocytes (Figure 1C), each 110–120 µm in diameter. Right parapodia of chaetigers 15 and 29 removed for observation; two left median elytra still on site removed for observation (kept in container). Body about 22 mm long, 2.5 mm wide (without parapodia), 51 chaetigers.

Prostomium medially swollen, not bilobed, without cephalic peaks (Figure 1B). Median antenna with ceratophore about 1/3 as wide as prostomium, style lost; lateral antennae inserted ventrally, ceratophores half as wide as median one, right style tapered, bent, about half as long as left palp. Left palp tapered, smooth, tip broken. Eyes blackish, reniform, anterior eyes lateral, slightly larger than posterior ones, displaced posteriorly, behind widest prostomial area; posterior eyes dorsal, near hind prostomial margin.

First or tentacular segment without chaetae, cirri lost. Second or buccal segment with first pair of elytrophores, parapodia biramous, cirri lost. Nuchal lappet or tubercles missing. Ventral cirri thin, tapered, in median segments not reaching neuropodial lobes tip.

Parapodia biramous; notopodia with dorsal cirri lost; notacicular lobes tapered, with about 10 notochaetae per bundle (Figure 1D), each terete, with series of short transverse rows of tiny denticles continued almost to tip, tip entire (Figure 1D, inset). Neuropodia with large neuracicular lobe, with a supracicular process (Figure 1E, inset), with about 20 neurochaetae per bundle, each oar-shaped, slightly bent, with many series of tiny denticles along subdistal area, upper neurochaetae finely bidentate, lower ones unidentate (Figure 1F, inset). Ventral cirri tapered, not reaching neuracicular lobe tip.

Elytra mostly lost, 21 pairs, two remaining in median elytra, markedly rolled over themselves; elytrophores on segments 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 28, 31, 33, 38, 40, 43, 45, and 47. Elytra oval, smooth, without fimbriae (Figure 1G), probably overlapping middorsally. Insertion area eccentric, with some venation.

Posterior end tapered; pygidium with anus terminal, anal cirri lost.

Variation

The paratype (ECOSUR 323) is an anterior fragment, 11 mm long, 3.2 mm wide (without parapodia), and about 21 chaetigers; many parapodia partially broken, most cephalic appendages, tentacular and parapodial cirri lost. After Methyl-green staining, the brain lobes become darker than adjacent prostomial areas. Left tentacular cirri detaching (Figure 1H), slightly shorter than right palp. Eyes blackish, of similar size, anterior eyes barely visible dorsally, displaced posteriorly, posterior eyes towards posterior prostomial margin. No nuchal lappet or dorsal tubercles. Copepod parasite attached midventrally in chaetiger 8 (Figure 2A, B).

Remarks

Jimipolyeunoa richeri sp. n. is the only species in the genus. This species somehow resembles those included in Neopolynoe Loshamn (Reference Loshamn1981) or Parapolyeunoa Barnich et al. (Reference Barnich, Gambi and Fiege2012) having elongate bodies with smooth elytra, and this new species might be a commensal of soft corals, but this needs corroboration because this type of affinity cannot be retrieved from the field data after this type of dredging operations.

Further, because the collecting gear was an Arrow Trawl, used for sampling fishes having a mesh size of 10 cm, there were only 7 polychaetes recorded during the Halipro 2 Campaign (Grandperrin et al., Reference Grandperrin, Farman, Lorance, Jomessy, Hamel, Laboute, Labrosse, Richer de Forges, Seret and Virly1997: 67). It was fortunate that two of them were polynoids and one had a parasitic copepod on it (see below); they were damaged after a trawling activity extended for over an hour.

Distribution

Only known from the type locality, 100 km off South of Vao, New Caledonia, in 448–880 m depth.

Class Copepoda Milne-Edwards, 1840

Order Cyclopoida Burmeister, 1834

Family Herpyllobiidae Hansen, 1892

Genus Herpyllobius Steenstrup and Lütken, 1861

Herpyllobius pleurotumoris sp. nov.

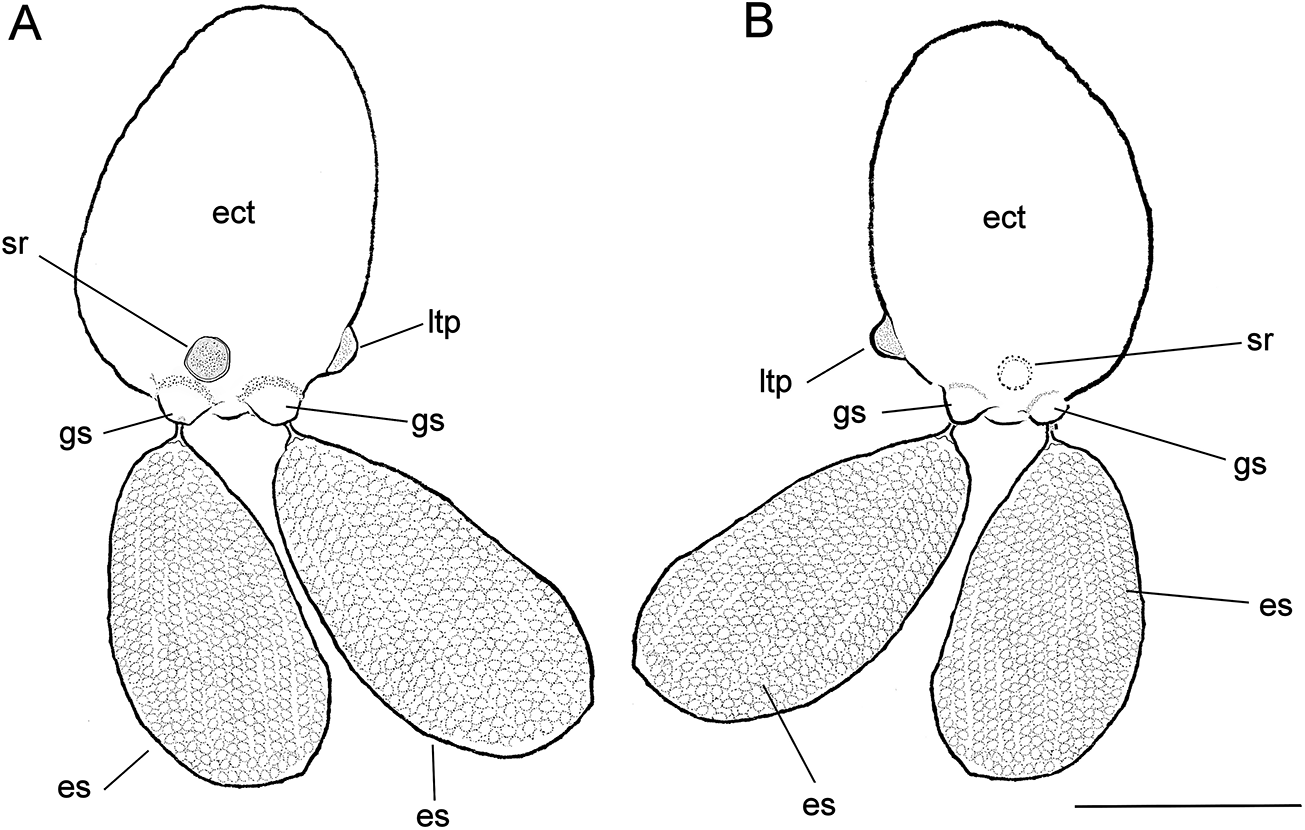

Figure 3. Herpyllobius pleurotumoris sp. n., holotype female from Jimipolyeunoa richeri gen. n., sp. n. (A) ectosoma (ect) with egg sacs (es), sclerotized ring (sr), genital swellings (gs), and lateral tumour-like process (tlp), dorsal view; (B) same, ventral view. Scale bars: A, B, 1 mm.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:C9FDFA5B-C091-4A10-BC61-9CD649441424

Type material

Holotype (ECOCHZ-12610), ovigerous female, parasitizing Jimieupolynoa richeri gen. n., sp. n. (Polychaeta, Polynoidae, Polynoinae) from New Caledonia, Sta. BT94 (23°36.97´ S, 167°41.66´ E to 23°33.48´ S, 167°42.39´ E), 448-880 m, 24 Nov. 1996 (data from Grandperrin et al., Reference Grandperrin, Farman, Lorance, Jomessy, Hamel, Laboute, Labrosse, Richer de Forges, Seret and Virly1997). Specimen removed from host, incomplete, holotype material comprising two separate egg sacs and endosoma, preserved in vial, 70% ethanol with glycerine.

Etymology

The specific epithet derives from a combination of the Greek noun plevra (= side) and the Latin noun tumour (= protuberance) in singular genitive case, with masculine ending. The name refers to the presence of a tumour-like protuberance on the ectosoma lateral surface.

Diagnosis

Herpyllobius female ectosoma oviform, integument smooth, whitish. Paired genital swellings moderately sclerotized, weakly developed. Intergenital surface smooth, lacking medial process or bulging protuberances. Rounded sclerotized ring present adjacent and anteriorly to genital swellings; sclerotized ring crater-like, about same diameter of genital swellings. Right side of ectosoma with single bulging tumour-like process on posterior third, adjacent to genital swellings. Endosoma with two sections, first (proximal) one represented by proximal cylindrical lobe tapering on one side, truncate end on the other. First section with wide flap-like process. Second (distal) section, represented by rounded lobe with regular margin. Egg sacs thick, oviform, yellowish, almost twice as long as wide, almost as long as ectosoma; egg sacs unequally long, one being 20% smaller; egg sacs multiseriate, containing 13–18 egg rows each.

Male

Unknown.

Host

Jimieupolynoa richeri gen. n., sp. n. (Polychaeta, Polynoidae, Polynoinae) from New Caledonia.

Attachment site

The copepod was found attached to the host ventral surface in chaetiger 8 (Figure 2A–C).

Type locality

100 km off South of Vao, New Caledonia, in 448–880 m depth, on Jimipolyeunoa richeri gen. n., sp. n.

Description

Holotype (ECOCHZ-12610), ovigerous female, ectosoma oviform,1.66 times as long as wide, with a maximum length of 1.76 mm, 1.26 mm wide, ectosoma integument smooth, weakly translucent (ect in Figures 2A, B, 3A). Paired genital swellings weakly sclerotized, moderately prominent (gs in Figures 2B, 3A, B). Genital swellings moderately developed, rounded, 235 μm in diameter, carrying pair of egg sacs. Intergenital surface smooth, lacking medial processes or protuberances (Figure 2C); sclerotized ring present on dorsal surface adjacent and anterior to genital swellings (sr in Figures 2C, 3A, B); sclerotized ring rounded, crater-like, slightly smaller in diameter (212 μm) than genital swellings. Postero-lateral surface of ectosoma smooth except for tumour-like process adjacent to right genital swelling (ltp in Figures 2B, C, 3A, B). Intersomital stalk short, thick, ca. 240 μm wide, originating from underside of ectosoma close to midbody. Endosoma 1.88 mm long, slightly longer than ectosoma, comprising two sections, proximal thick cylindrical lump tapering on one side, truncate on other (Figure 2B). First section with wide flap-like process on medial position (mfl in Figure 2C). Distal endosomal half represented by rounded lobe with regular edges. Egg sacs multiseriate, thick, cylindrical, unequally long; larger sac 3.33 mm long, 1.71 mm wide, smaller sac 2.78 mm maximum length, 1.41 mm wide. Eggs 110 μm in diameter.

Male

Unknown, absent from perigenital area where they are likely attracted to (López-Gonzalez et al., Reference López-Gonzalez, Bresciani and Conradi2000).

Remarks

Herpyllobius pleurotumoris sp. n. is included in Herpyllobius as it exhibits the main diagnostic characters of this copepod genus according to Lützen (Reference Lützen1964) and Boxshall et al. (Reference Boxshall, O’Reilly, Sikorski and Summerfield2019). The known Herpyllobius species were grouped by Lützen and Jones (Reference Lützen and Jones1976) based on the position and size of the medial protuberances, and the number and arrangement of cuticular processes (cuticular dots) above or between the genital swellings, and then updated with additional characters by López-Gonzalez et al. (Reference López-Gonzalez, Bresciani and Conradi2000) (see characters in Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2022, table 1).

Group I species have a prominent bulging process on the intergenital area, with four adjacent sclerotised dots. This group contains 8 species with the addition of the recently described H. pabloi Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2025) from deep waters of New Guinea. Group II comprises species with 2–4 sclerotized dots in the area adjacent to the genital swellings, whereas Group III comprises the species of the genus lacking these intergenital structures. Group II contains 9 species with the recent inclusion of the Australian H. paulayi Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2024), the Papuan H. chambardi Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2025), and H. hourdezi Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2025) (Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2025). A fourth group was erected by Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2022) to accommodate the Papuan species H. piotrowskiae Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2022).

Because of the lack of an intergenital protuberance or sclerotized dots, H. pleurotumoris n. sp. can be included in Group III, joining H. cluthensis Boxshall et al. (Reference Boxshall, O’Reilly, Sikorski and Summerfield2019), H. haddoni Lützen (Reference Lützen1964), H. luetzeni López-González and Bresciani, Reference López-González and Bresciani2001, H. nipponicus Lützen (Reference Lützen1964), H. polarsterni López-Gonzalez et al. (Reference López-Gonzalez, Bresciani and Conradi2000), and H. stocki López-Gonzalez et al. (Reference López-Gonzalez, Bresciani and Conradi2000), and the recently described H. paulayi Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2024), H. chambardi Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2025), and H. hourdezi Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2025).

Herpyllobius pleurotumoris lacks a bulging process or integumental sclerotized dots in the intergenital surface and thus it belongs to Group III, but it shares an important character with H. cordiformis Lützen (Reference Lützen1964) a member of Group I; i.e., the presence of a heavily sclerotized ring adjacent to the genital swellings (Lützen, Reference Lützen1964, Figs. 13–15), which is represented by a shallow crater-like sclerotized ring in H. pleurotumoris (Figure 2C). Both species can be easily distinguished by several characters: (1) the development of the sclerotized ring, strongly developed, forming a demarcated bulge in H. cordiformis vs. weakly developed, flat ring in H. pleurotumoris; (2) slender, sausage-like egg sacs in H. cordiformis (Lützen, Reference Lützen1964) vs. thick, oviform egg sacs in H. pleurotumoris; (3) endosoma branched into multiple diverticulae in H. cordiformis (Lützen, Reference Lützen1964) vs. unbranched, block-like endosoma in H. pleurotumoris (Figure 2C); (4) heavily sclerotized genital swellings in H. cordiformis vs. weakly sclerotized swellings in H. pleurotumoris (Figure 3A); and (5) the presence of a tumour-like protuberance on the lateral surface of the ectosoma in H. pleurotumoris (ltp in Figures 2B, C, 3A) vs. smooth lateral endosomal surface processes in H. cordiformis (Lützen, Reference Lützen1964, Fig. 13). Overall, the new species can be recognized from its known congeneric species by a unique combination of characters including (1) the presence of the tumour-like process on the lateral surface of the ectosoma, (2) a crater-like sclerotized ring in the intergenital surface, and (3) a block-like endosoma with a single medial lobe.

Discussion

The proposal of Jimipolyeunoa as a new genus follows a long tradition using morphology for supporting taxonomic decisions and recognition of different supraspecific taxa. During the last 25 years, the discovery or proposal of new genera in Polynoidae has been supported by morphological, molecular, or a combination of these studies. Of course, these results depended on the quality of the specimens and of the funds available for finer studies. The studies based only on morphological features include Barnich and Fiege (Reference Barnich and Fiege2000) proposed Neolagisca for a previously known species. Barnich et al. (Reference Barnich, Fiege, Micaletto and Gambi2006) proposed Antarctinoe for including two previously known species. Barnich et al. (Reference Barnich, Gambi and Fiege2012) proposed Parapolyeunoa to include an already known species, whereas Neal et al. (Reference Neal, Barnich, Wiklund and Glover2012) proposed Austropolaria and a new species from the Southern Ocean. Salazar-Silva (Reference Salazar-Silva2020) proposed Kristianides for an already known species from the Gulf of Mexico. Núñez et al. (Reference Núñez, Barnich and Monterroso2022) proposed a new genus based upon morphological features, Webbnesia, with specimens from the Canary Islands. Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2024) proposed Barnichia for a newly described species form the Western Atlantic.

Whereas studies combining morphologic and genetic data include Bonifácio and Menot (Reference Bonifácio and Menot2019) used morphology and three genes (COI, 16S, 18S) in the analysis of deep-sea polynoids from the Equatorial Pacific. They proposed four new genera and provided a key to the 37 Macellacephalinae genera. Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Zhou and Wang2021) proposed Ceuthone after using morphology and four genes (COI, 16S, 18S, 28S), for a species living in sponges collected in the Weijia Guyot, western Pacific. Capa et al. (Reference Capa, Pons and Jaume2022) used morphology and four genes (COI, 16S, 18S, 28S), and proposed Pollentia for a new species found in an anchialine cave in the Balearic Islands. Jimi et al. (Reference Jimi, Hookabe, Woo and Kohtsuka2025) combined morphology and four genes (COI, 16S, 18S, 28S) proposed two new genera, Echinophilia and Paraechinophilia, for two new species found living on sea urchins in Sagami Bay, Japan.

The presence of H. pleurotumoris as a parasite of a polynoid polychaete is not surprising; according to Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2022, table 1 and sources therein, 2025) and the present data, up to 20 of the 23 known species of Herpyllobius (Walter and Boxshall, Reference Walter and Boxshall2025) have been recorded from members of the annelid family Polynoidae (see Conradi et al., Reference Conradi, Bandera, Marin and Martin2015). Only a few species of Herpyllobius, viz. H. arcticus Steenstrup and Lütken, 1861 (Phyllodocidae), H. piotrowskiae Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2022) (Iphionidae), and H. paulayi Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2024) (Flabelligeridae), have been reported as parasites of non-polynoid annelids.

Members of Herpyllobius Group III are mostly shallow-water species (0–40 m), except for the Antarctic H. stocki López-Gonzalez et al. (Reference López-Gonzalez, Bresciani and Conradi2000) and H. polarsterni López-Gonzalez et al. (Reference López-Gonzalez, Bresciani and Conradi2000), both dwelling in midwater (395–567 m) (López-Gonzalez et al., Reference López-Gonzalez, Bresciani and Conradi2000). The new species H. pleurotumoris, found at a depth range of 448–880 m, joins these two congeners as another deep-living species of Group III Herpyllobius. It also joins several other Herpyllobius reported from the same depth range (see Conradi et al., Reference Conradi, Bandera, Marin and Martin2015; Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Suárez-Morales and Salazar-Vallejo2025).

Acknowledgements

Tarik Meziane and Laure Corbari were very supportive during a research visit to Paris by one of us (SISV) for studying a part of their collections. Initial sorting of MUSORSTOM material was funded by the late Alain Crosnier and Fredrik Pleijel (both MNHN).

Author contributions

Authors contributed equally in study design, descriptions, illustrations, and text edition.

Financial support

None in particular for generating this contribution.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

Study and analysis of specimens were done with the highest ethical standards.

Data availability

All relevant data are included in this contribution.