Introduction

Stable isotope studies have proved highly informative about diet across England in the high and late medieval periods (eleventh–sixteenth century AD, henceforth ‘medieval’) (Müldner & Richards Reference Müldner and Richards2005, Reference Müldner and Richards2007a & Reference Müldner and Richardsb; Bownes et al. Reference Bownes, Clarke and Buckberry2018; Kancle et al. Reference Kancle, Montgomery, Gröcke and Caffell2018; Halldórsdóttir et al. Reference Halldórsdóttir2019). While documentary and artefactual evidence can provide general information about diet, stable isotope analysis of the bones of the medieval people themselves provides crucial individual-level resolution. Such data allow for more complex, person-focused analyses that can identify socially differentiated patterns in consumption, challenging prior assumptions regarding medieval diet (e.g. Müldner & Richards Reference Müldner and Richards2007a & Reference Müldner and Richardsb).

This article explores social differences in diet within medieval towns through high-resolution isotopic analysis of a single location: Cambridge. One limitation of stable isotope studies is the nature of the archaeological material available for study. The most extensively excavated, and therefore sampled, sites in England tend to be drawn from specific religious institutions; these sites are unlikely to reflect the diet of ‘ordinary’ people and thus relatively minor groups within the population are over-represented in the data.

To obtain a more representative picture of medieval diet, our study includes individuals from across the social strata of a single medieval town, employing a ‘whole-town’ approach (see Dittmar et al. Reference Dittmar, Inskip, Rose, Cessford, Mitchell, O’Connell and Robb2024). By studying geographically constrained and temporally overlapping cemetery groups, alongside a robust isotopic baseline, we aim to reduce the number of confounding variables that are often present in archaeological research. This allows for greater insight into the lived experience of different groups of people in the past. Our goal is to identify differences and commonalities in diet between social strata.

Medieval diet in England

Historical documents and archaeological evidence, such as archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological remains, attest that diet in medieval England largely consisted of grain products, such as bread, ale and pottage, supplemented with animal products, fruit and vegetables (Woolgar et al. Reference Woolgar, Serjeantson and Waldron2006). Food consumption, particularly of meat and fish, varied across a town’s population depending on season, supply, social status and wealth (Woolgar Reference Woolgar2016). The consumption of meat was also restricted by religious rules, which encouraged the avoidance of quadruped meat on certain days of the week and religious holidays, when the eating of fish instead was encouraged (Woolgar Reference Woolgar, Woolgar, Serjeantson and Waldron2006a, Reference Woolgar2016). However, these sources tell only a partial story and do not permit quantification of individual dietary experience.

Broad indications of individual food consumption in the past can be assessed through isotopic analysis of carbon and nitrogen in human tissues, allowing us to distinguish between the main types of plants consumed (those with the C3 photosynthetic pathway, such as wheat, barley, oats and most fruits and vegetables, or the C4 pathway, like millet), identify an individual’s trophic level and animal protein intake, and determine whether people were eating marine or terrestrial foods (see O’Connell Reference O’Connell, Pollard, Armitage and Makarewicz2023).

To date, isotopic analyses of more than 25 medieval skeletal collections from England have been carried out, producing bulk bone collagen carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) results for over 700 individuals. These studies have generally indicated inter- and intra-site differences in diet, highlighting the influence of the ‘Fish Event Horizon’ (a marked increase in marine fishing at the end of the first millennium AD; Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Locker and Roberts2004) and of religious fasting (e.g. Müldner & Richards Reference Müldner and Richards2005). Thus, two key dimensions to diet appear to be religion and status, which were effectively interlinked in the medieval period.

Methodologically, these studies typically proceed through the comparison of burials from different contexts. In medieval England, burial could occur in many settings, including parish churchyards, religious houses and hospitals (Daniell Reference Daniell1997). Several English medieval parish cemeteries have been studied isotopically, including St Andrew Fishergate, York (Müldner & Richards Reference Müldner and Richards2007a), St Augustine, Ipswich (Farber & Lee-Thorp Reference Farber, Lee-Thorp and Brown2020) and Wharram Percy in Yorkshire (Richards et al. Reference Richards, Mays and Fuller2002; Britton et al. Reference Britton, Fuller, Tütken, Mays and Richards2015). Yet many of the extensively analysed skeletal collections are associated with specific religious institutions of varying financial prosperity. Such sites could contain a mixture of individuals: priests, monks, friars, lay brethren, benefactors, corrodians (live-in pensioners) and hospital inmates but, at some, ‘ordinary’ parishioners may have been largely absent. Definitive assignment of individuals to social groupings is often not possible, except when specialised grave goods or burial treatments are observed (e.g. St Giles by Brompton Bridge; Müldner & Richards Reference Müldner and Richards2005), or when there is distinct zoning in burial geography (e.g. St Andrew Fishergate, York; Müldner & Richards Reference Müldner and Richards2007a).

Combining multiple burial sites, studies of York (Müldner & Richards Reference Müldner and Richards2007b), Hereford (Halldórsdóttir et al. Reference Halldórsdóttir2019) and Oxford (Craig-Atkins et al. Reference Craig-Atkins2020) show how within a town there may be important social differences in diet, particularly related to wealth and religious affiliation. Such studies demonstrate the potential for high-resolution isotopic analysis to characterise variation in diet across different social strata and communities, even when based on relatively small sample numbers. The current larger-scale investigation aims to build upon the success of these previous studies by using greater representation of broadly contemporaneous but socially different groups to further explore these important social differences and their visibility in the isotopic data.

Medieval Cambridge

By the medieval period, Cambridge was an established settlement with good road and waterway connections. Numerous monasteries and friaries represented most of the major medieval religious orders and the university was founded in the thirteenth century. Population size in AD 1066 is estimated to have been 1200–2200, increasing to 3400–5300 by the end of the medieval period (Casson et al. Reference Casson, Casson, Lee and Phillips2020). Many residents would have worked in agriculture, although the population would also have included people involved in specialised trades and crafts people, merchants, scholars and clergy. The residents formed a hierarchical socioeconomic structure; there was a small wealthy elite, but most people were probably manual workers. The religious and academic institutions varied in wealth and status, and scholars and members of religious orders could find themselves positioned across the social hierarchy.

Cambridge was surrounded by good arable farmland and relied on its hinterland for supplies. Grain could be sourced nearby, meat could be obtained from the Fens and beyond and fuel and timber were brought in from further afield, along with imports via waterways (Lee Reference Lee2005). Cambridge was an important hub for agricultural trade and hosted several important fairs, including the internationally significant Stourbridge fair (Miller & Hatcher Reference Miller and Hatcher1995: 166–76). Overall, residents could enjoy a variety of locally produced and imported foodstuffs.

Representing the population of medieval Cambridgeshire

Skeletons from four key cemeteries were chosen to represent a cross-section of medieval society: ‘ordinary’ parishioners from both urban and rural settings, ‘poor’ recipients of charity and ‘prosperous’ members of a religious order (Figure 1; see Inskip et al. Reference Inskip2023; Dittmar et al. Reference Dittmar, Inskip, Rose, Cessford, Mitchell, O’Connell and Robb2024 for further social discussion). While efforts were made to select broadly contemporaneous individuals, due to the nature of available archaeological material, the sites selected do span over six centuries and do not wholly overlap in their use.

Figure 1. Cambridge and surrounding area c. AD 1350, showing the locations of the cemeteries analysed (base map: Vicki Herring; modifications: Kevin Moon).

The parish sites

All Saints by the Castle, located just north of the River Cam, represents an ‘ordinary’ town parish population. The church and cemetery were founded c. AD 940–1150 and went out of use in AD 1365–1366 (Cessford et al. Reference Cessford, Scheib, Guellil, Keller, Alexander, Inskip and Robb2021). As a burial ground for local parishioners, the cemetery comprised individuals from a social and economic cross-section of medieval society.

The ‘ordinary’ rural parish population is represented by Cherry Hinton, a small village 4.5km south-east of central Cambridge. Burials from Church End, Cherry Hinton, span AD 940/990–1120/1170 (Cessford & Dickens Reference Cessford and Dickens2005; Cessford & Slater Reference Cessford and Slater2014). As a proprietorial/parochial rural cemetery, the individuals represent a cross-section of the local rural population.

The Hospital

The Hospital of St John the Evangelist broadly represents the poorer population of Cambridge, as the Hospital provided shelter and food for people in need of charity, and, for some, an ultimate place of rest (Rubin Reference Rubin1987: 157). Burials at the Hospital date to between c. AD 1204/1214 and 1467/1511 (Cessford Reference Cessford2015; Cessford & Neil Reference Cessford and Neil2022). Those buried at the Hospital were socially heterogeneous, however, and could include staff, university scholars, benefactors and corrodians as well as the poorer recipients of charity (Cessford Reference Cessford2015; Inskip et al. Reference Inskip2023).

The Friary

The Augustinian Friary, in the centre of Cambridge, was a prosperous religious institution. Burials from its cemetery date to c. AD 1290–1360/1420, while burials from the chapter house date to c. AD 1360/1420–1538 (Cessford & Neil Reference Cessford and Neil2022). People buried at the Friary include friars, lay benefactors and corrodians. Burials of friars can be distinguished from lay individuals at the Friary by the presence of associated girdle buckles, indicating clothed burial (Cessford et al. Reference Cessford, Hall, Mulder, Neil, Riddler and Wiles2022).

Samples and methods

Collagen from non-pathological rib-bone shafts of 220 medieval adults (>18 years) from the four cemeteries was analysed. To provide an isotopic ‘baseline’ (see discussion in Makarewicz & Sealy Reference Makarewicz and Sealy2015), 133 medieval terrestrial and aquatic faunal bone samples were analysed from domestic contexts from four contemporaneous sites in Cambridge (see online supplementary material (OSM) 1), in addition to published isotopic data from 15 codfish (Barrett et al. Reference Barrett2011). Sampling, preparation and isotopic analysis were carried out at the Dorothy Garrod Laboratory, University of Cambridge, following in-house protocols (see OSM1).

Results

Characterising the diet of a whole medieval town and its hinterlands

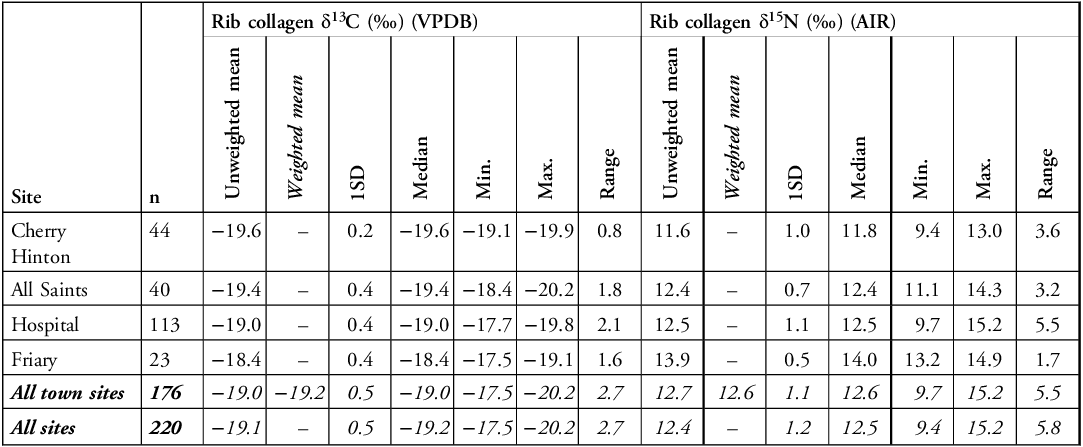

Carbon and nitrogen isotope values were successfully analysed from the 220 human rib and 133 faunal-bone collagen samples (Tables 1 & 2, Figure 2, OSM3 & OSM4). The average adult δ13C values for all sites is around −19.1‰, and the average δ15N is around 12.4‰ (n = 220, Table 1, Figure 2). The average values are similar when considering only the town sites (All Saints, Hospital, Friary; n = 176).

Table 1. Summary statistics for adult (>18yr) rib-bone collagen δ13C and δ15N values.

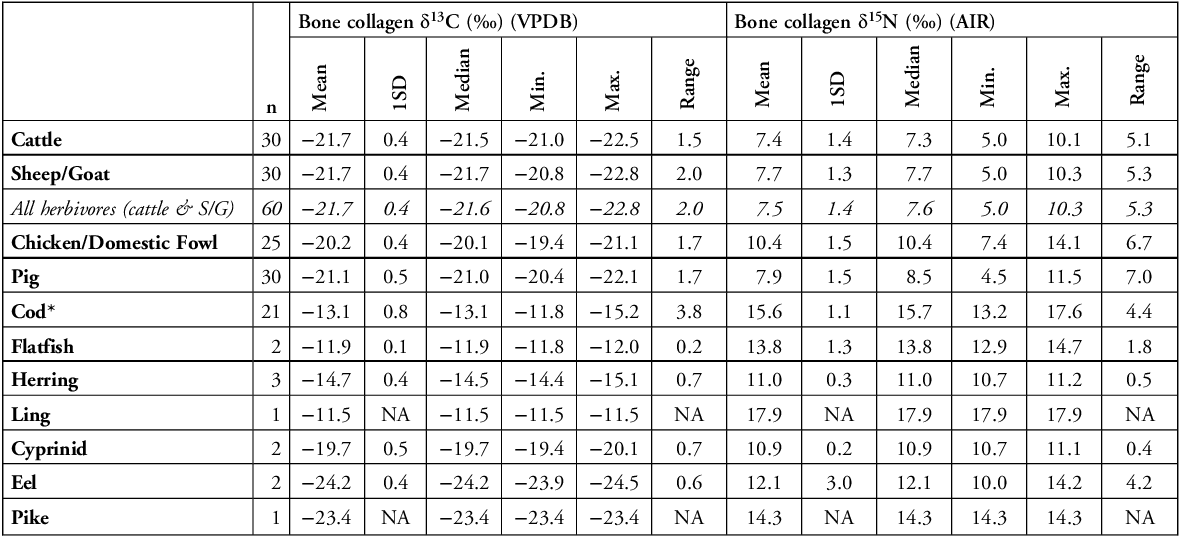

Table 2. Summary statistics for faunal-bone collagen δ13C and δ15N values from medieval Cambridgeshire contexts.

*Includes 15 results from Barrett et al. (Reference Barrett2011).

Figure 2. Scatterplot of adult (>18yr) rib collagen δ13C and δ15N individual and mean (± 1SD) values for the four medieval sites, with a linear regression line for all adult data. Scatterplot includes medieval faunal-bone collagen δ13C and δ15N individual and mean (± 1SD) values. Statistical testing indicates that the samples are unlikely to have been taken from populations with the same distribution (Kruskal–Wallis: δ13C & δ15N p = <0.001), with post-hoc tests indicating differences in δ13C values between all sites except between All Saints and Cherry Hinton, and in δ15N values between all sites except between the Hospital and All Saints (see OSM2). The data for Cherry Hinton have some degree of skew (see Figure 5), yet the data are presented here both as individual points and as mean and standard deviation, to be consistent with the other populations plotted (figure by Alice Rose).

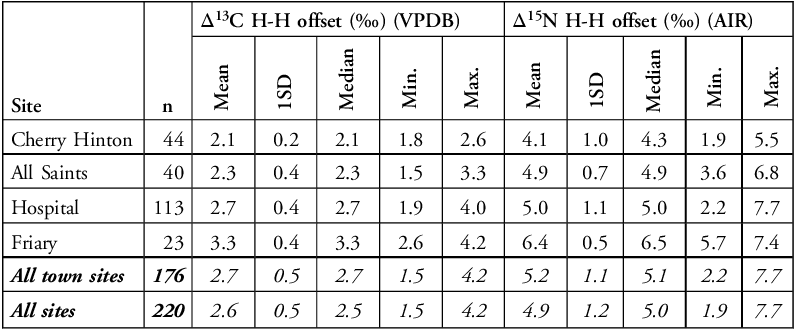

Yet, the available samples are not unbiased in their representation of the demography of medieval Cambridge. For example, people living at the Hospital probably made up less than one per cent of the town’s population (Dittmar et al. Reference Dittmar, Inskip, Rose, Cessford, Mitchell, O’Connell and Robb2024), but they make up 64 per cent (113/176) of the isotopic sample. To compensate for this, we estimate weighted mean isotopic values for the town (following Dittmar et al. Reference Dittmar, Inskip, Rose, Cessford, Mitchell, O’Connell and Robb2024): the mean values from each site are weighted by how much the types of people buried there (townsfolk, religious professionals, recipients of charity) are estimated to have contributed to the overall population. This yields weighted means of −19.2‰ for δ13C and 12.6‰ for δ15N (Table 1)—which are within analytical error (±0.2) and one standard deviation of the unweighted means—indicating, in this case, that weighting the average does not significantly change the overall isotopic characterisation. Whether unweighted or weighted, the overall town population still has higher mean δ13C and δ15N values than the rural parish population (unweighted by +0.6‰ for δ13C and +1.1‰ for δ15N, weighted by +0.4‰ for δ13C and +1.0‰ for δ15N; Table 1). Mean human isotopic values were offset from contemporaneous herbivores by 2.6±0.5‰ for δ13C and 4.9±1.2‰ for δ15N (Table 3, Figure 3). This is greater than typical δ13C offset values (Bocherens & Drucker Reference Bocherens and Drucker2003) but within typical δ15N offset values (Hedges & Reynard Reference Hedges and Reynard2007; O’Connell et al. Reference O’Connell, Kneale, Tasevska and Kuhnle2012), indicating that many people were regularly eating terrestrial animal products and/or fish. Individual offsets vary substantially—with several individuals having δ15N offsets of <3.0‰ or >6.0‰—suggesting social variation in diet.

Table 3. Summary statistics for human-herbivore (H-H) offset (Δ13C and Δ15N values).

Figure 3. Scatterplot of the offset between adult human rib collagen δ13C and δ15N values and contemporary herbivore-bone collagen mean δ13C and δ15N values, resulting in human-herbivore (H-H) Δ13C and Δ15N values for the four medieval sites. Inset: H-H offset Δ13C and Δ15N values +1SD (above) and −1SD (below). Offset values are not absolute. Dashed lines indicate typical trophic level offset Δ13C of 0.0–2.0‰ (Bocherens & Drucker Reference Bocherens and Drucker2003) and typical human-faunal offset Δ15N of 3.0–6.0‰ (Hedges & Reynard Reference Hedges and Reynard2007; O’Connell et al. Reference O’Connell, Kneale, Tasevska and Kuhnle2012) (figure by Alice Rose).

Characterising diet between cemetery populations and social groupings

The four sites have dissimilar distributions in carbon and nitrogen isotopic values, indicating different patterns of dietary consumption (Figures 2 & 4, OSM2). Using All Saints as a baseline of ordinary townspeople, the rural population at Cherry Hinton generally has the lowest isotopic values. In contrast, the Friary population is distinctive in its higher δ13C and δ15N values; those buried in the Friary effectively occupied a separate isotopic ‘niche’, which overlapped little with the other three groups (Figure 4). While lower isotopic values might have been expected in the Hospital population, what really distinguishes this population is the large range of values, which overlap with all the other sites. This reflects the varied social backgrounds of individuals buried there (see above).

Figure 4. Output of estMCP in R package rKIN (Eckrich et al. Reference Eckrich2020) showing the minimum convex polygon for adult (>18yr) rib collagen δ13C and δ15N values for the four medieval sites, at 50 and 95% confidence levels. Calculations of the per cent of polygon overlap between each site indicates no overlap between the Friary and Cherry Hinton at 50, 75 or 95% confidence levels, no overlap between the Friary and All Saints at 50 and 75% confidence levels and no overlap between the Friary and the Hospital at the 50% confidence level (see OSM2) (figure by Alice Rose).

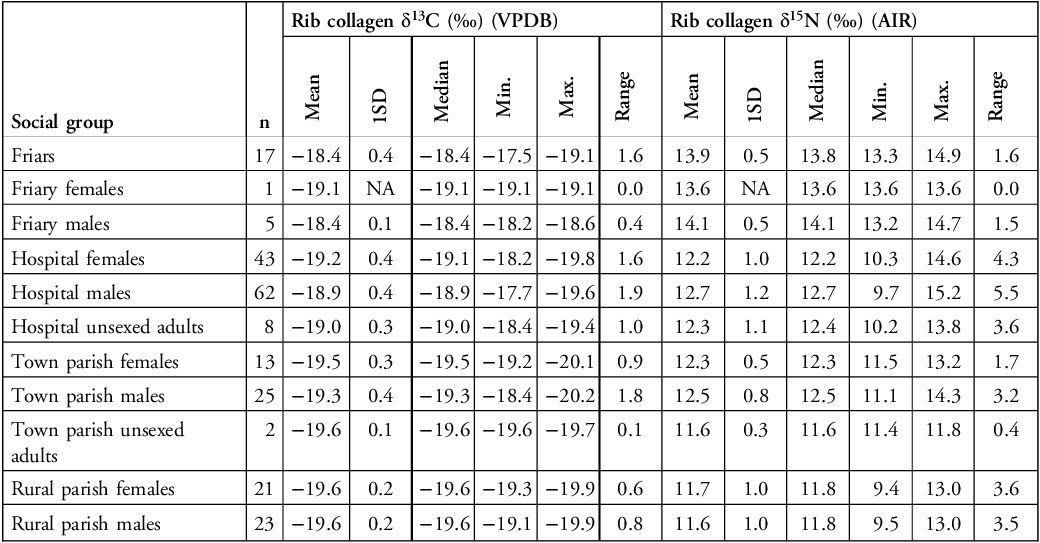

Inter-site differences are greater than intra-site differences (Table 4, Figure 5, OSM2). This is not entirely surprising, as each site was explicitly chosen to represent a different ‘type’ of social group who probably lived and ate differently to some degree (see below). Chronological differences between some of the sites may also be an influencing factor. Within each site, there are no clear differences between isotopic values for males and females; rural females and males do not differ isotopically from the urban females and males buried at All Saints but males buried at the Friary and Hospital do, however, differ from rural males in both δ13C and δ15N (Table S2.8). Individuals identified as friars buried at the Friary tend to have δ15N values that are higher than most of the other groups (Table 4, Figure 5), although they are not significantly different from the other males buried in the Friary or the Hospital (see OSM2). Each site, thus, represents a sector of society with its own way of eating.

Table 4. Summary statistics for adult (>18yr) rib-bone collagen δ13C and δ15N values, by broad social grouping.

Figure 5. Raincloud plots of adult (>18yr) rib collagen δ13C and δ15N values for the four medieval sites, with scatter showing data by social grouping. Statistical testing indicates that the samples by social group are unlikely to have been taken from populations with the same distribution (Kruskal–Wallis: δ13C & δ15N p = <0.001), with post-hoc tests indicating differences in δ13C and δ15N values across multiple groups, with Friars being the group with the largest number of comparisons with p.adj = <0.05 (see Table S2.8) (figure by Alice Rose).

Discussion: diet in medieval Cambridge

Diet in the overall town

The δ13C values indicate that the diet in medieval Cambridge was based on C3 plants, with no evidence for C4 plant intake. This is consistent with the most common crops grown in medieval England (wheat, barley, rye, oats, peas and beans, all C3) (Stone Reference Stone, Woolgar, Serjeantson and Waldron2006) and the results of other similar isotopic studies in this period (e.g. Müldner & Richards Reference Müldner and Richards2005, Reference Müldner and Richards2007b; Bownes et al. Reference Bownes, Clarke and Buckberry2018; Kancle et al. Reference Kancle, Montgomery, Gröcke and Caffell2018). The δ15N values indicate that most people were omnivorous. Substantial variation in animal protein consumption is, however, apparent in the wide range in δ15N values (5.8‰), which are towards the upper limit of the typically cited stepwise ‘trophic-level effect’ of 3.0–6.0‰ (Hedges & Reynard Reference Hedges and Reynard2007; O’Connell et al. Reference O’Connell, Kneale, Tasevska and Kuhnle2012). The high δ15N and δ13C human-herbivore offsets seen in some individuals (Table 4, Figure 3), as well as the positive correlation between δ13C and δ15N values (Figure 2, r 2 = 0.535), indicate that some of the population consumed marine proteins. Medieval fish-bone assemblages from Cambridge include a wide variety of freshwater and marine species, particularly herring, as well as eel, smelt and Salmonidae (Harland Reference Harland2008, Reference Harland2009; Cessford & Dickens Reference Cessford and Dickens2019: 197–99). These assemblages corroborate the isotope findings. Isotopic evidence for fish consumption (particularly marine) is observed at other medieval English sites, such as York (Müldner & Richards Reference Müldner and Richards2007a & Reference Müldner and Richardsb). Increased consumption in the medieval period has been associated with the expansion of the marine fishing industry, although access to marine resources still varied based on status, geography and time (Müldner Reference Müldner, Barrett and Orton2016).

Social variation in foodways

Marked social differences in foodways are apparent in the isotopic record. Between the two parish sites, higher δ15N values at All Saints indicate townspeople were more likely to have regular access to animal and/or marine proteins than rural people from Cherry Hinton. Historical sources suggest that urban and rural diet would have differed, with rural populations generally eating less meat and marine fish, at least in the high medieval period (Woolgar et al. Reference Woolgar, Serjeantson and Waldron2006). If rural communities ate secondary animal products (milk, cheese, eggs) to meet their protein needs (Woolgar Reference Woolgar, Woolgar, Serjeantson and Waldron2006a), it was not in great enough quantities to enrich 15N. Few ‘ordinary’ rural sites have been studied in England, but individuals from the medieval village of Wharram Percy have some of the lowest δ13C and δ15N values for the period (mean adult values: −19.7‰ δ13C, 8.7‰ δ15N, n = 18) (Richards et al. Reference Richards, Mays and Fuller2002; Britton et al. Reference Britton, Fuller, Tütken, Mays and Richards2015). The similar evidence from Cambridge suggests that urban/rural differences may have been present across the country and emphasises the need for further research on rural sites.

Among townspeople, wealth and religious affiliation were clearly strong influencing factors on diet. People buried in the Friary were largely distinct from the rest of the local population: their higher δ13C and δ15N values indicate that marine foods probably featured in their diet, although it is not possible to ascertain whether this was instead of or in combination with meats and dairy products. Distinctly higher isotopic values are often seen in those associated with specialist religious institutions (Müldner et al. Reference Müldner, Montgomery, Cook, Ellam, Gledhill and Lowe2009; Kancle et al. Reference Kancle, Montgomery, Gröcke and Caffell2018) and can be observed for both friars and laymen buried in the Friary. Archived requests for burial at the Friary from higher-status individuals, such as clerks, scholars and a burgess (Cessford & Neil Reference Cessford and Neil2022), indicate that at least some of these laymen were likely high-status individuals who could afford to regularly eat marine and terrestrial animal proteins. Isotopic values for the friars are tightly clustered, probably indicating that they, at least partially, adhered to a homogenising, institutionally prescribed diet (Woolgar Reference Woolgar, Woolgar, Serjeantson and Waldron2006b, Reference Woolgar2016). As seen in other medieval friaries in England (Kancle et al. Reference Kancle, Montgomery, Gröcke and Caffell2018), entering a specialist religious institution could lead to profound changes in diet, more often for the better.

Isotopic data from the Hospital is highly variable, far more so than the other groups, overlapping them all (Figure 5). Some of this variation may reflect the larger sample size but the isotopic data also reflect the social milieu of the Hospital. This pattern is not the same across other studies of medieval hospital cemeteries (Rose Reference Rose2020), reflecting the specialised and differing nature of these institutions. The Hospital’s cemetery contained a broad range of people including inmates, servants, benefactors, corrodians and scholars (Rubin Reference Rubin1987; Inskip et al. Reference Inskip2023). Some had experienced lifelong poverty, but others were more prosperous before entering the Hospital. Some had been university scholars before age or illness incapacitated them. Once admitted to the Hospital, individuals ate an institutional diet broadly following Augustinian dietary rules (Rubin Reference Rubin1987). We cannot determine how long inmates spent in the Hospital and thus whether an individual’s isotope values represent their previous diet, the Hospital’s food, or both; an individual with high δ13C and δ15N values could have been prosperous before entering the Hospital or they could have been long-term inmates, corrodians or staff benefiting from the prescribed diet. A proportion of those buried at the Hospital are likely to have experienced long-term poverty, but those with the highest isotope values highlight that the Hospital population is complex and cross-sectional.

Conclusions

Even within one medieval town, differences in diet were great enough to be detected by isotopic analysis of bulk collagen samples. Comparison between individuals from multiple burial sites allows greater understanding both of social differences within the town and of the nature of each site. The findings broadly reflect wider trends seen across England, allowing us to confirm that dietary differences observed between different social groups across the country can also be seen within a single town. Although the four sites analysed here are not fully contemporaneous—with burials occurring over approximately 600 years during a period that saw substantial development in agriculture and trade networks, influencing the availability of and access to specific foodstuffs—the apparent association between social differences and isotopic values cannot be fully accounted for by temporal variation (Robb et al. Reference Robb2025). Sampling inevitably omits some social groups, and while medieval Cambridge, a prosperous, well-connected and diverse place, may not represent the experience of diet in other areas of England (or Europe more broadly), this work shows the promise of a comparative, social approach to isotopic analysis. By sampling within one locality and establishing a robust isotopic baseline, we can reduce the number of variables that confound isotopic studies, allowing more nuance in interpreting data. Within our data, inter-site differences were greater than intra-site differences, showing that even within a relatively small town, society was detectably partitioned and social differences in diet correlated with burial location. Wealth and religious affiliation influenced diet, particularly in terms of access to marine and terrestrial animal protein. This whole-town approach allows for a more inclusive, intersectional analysis of past societies.

Acknowledgements

This article is the result of Alice Rose’s PhD research (University of Cambridge), part of the ‘After the Plague: health and history in medieval Cambridge’ project, and Mary Price’s BA dissertation (University of Cambridge). The authors thank all of the ‘After the Plague’ team for their support, Catherine Kneale, Emma Lightfoot, James Rolfe and the Godwin Laboratory, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge for analytical assistance, and the Cambridge Archaeological Unit, Cambridgeshire County Council and the Duckworth Collection for allowing sampling of material. Thanks also go to the anonymous reviewers and to Eric Guiry for their patient and constructive contributions to the manuscript revisions.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Collaborative Grant 200368/Z/15/Z.

Online supplementary material (OSM)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2026.10284 and select the supplementary materials tab.