High rates of food insecurity among college students are well-documented(e.g. Reference Bruening, Argo and Payne-Sturges1, Reference Nikolaus, An and Ellison2) and concerning, given the links between food insecurity and poor physical and mental health and academic performance(Reference Hagedorn, Olfert and MacNell3–Reference Coakley, Cargas and Walsh-Dilley8). However, little attention has been paid specifically to international college students in the USA.

Defined as students who are not citizens of the country where they are attending school, international students are an important segment of the US college student population. During the 2022–2023 academic year, about 1·1 million international students enrolled in postsecondary institutions in the USA, representing 4·2 % of the total enrolment(9), with the largest percentage (71 %) coming from Asian countries(10).

There is some evidence that high rates of international college students in the USA report food insecurity(Reference El Zein, Mathews and House11). In a sample of 2,654 students collected at a minority and Hispanic-serving US institution in April 2020, 39 % of international students reported experiencing food insecurity(Reference Mechler, Coakley and Walsh-Dilley12). Evidence also shows that international students are more likely to experience food insecurity than US citizens. Soldavini, Berner and Da Silva found that international student status increased the odds of experiencing food insecurity v. food security for undergraduate students and marginal food security v. high food security for graduate students in a sample of 4,819 students collected in 2016 at a large US public university(Reference Soldavini, Berner and Da Silva13).

Higher rates of food insecurity among international students may be partially explained by the unique financial challenges they face. In the USA, international students are not allowed to receive federal financial aid, which includes grants and work-study positions where aid does not need to be repaid, as well as federal loans that often have more favourable terms than private loans(14,15) . In the USA, international students are also not allowed to receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, which are an important food resource that provides near-cash benefits that can be used to purchase food at many food retailers(Reference Freudenberg, Goldrick-Rab and Poppendieck16,17) .

To effectively design programmes and resources to ensure food security, it is important to understand the demographic correlations of food insecurity for international students. We know of only two studies that examine demographic or descriptive correlations of food insecurity for international students in the USA. Soldavini, Andrew and Berner conducted an online survey with a convenience sample of 263 international undergraduate and graduate students at a southeastern US university in fall 2016(Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner18). Twenty-five percent of their sample reported experiencing food insecurity. In examining the relationship between sixteen demographic variables and food insecurity, they found that gender, year in school, possession of a car, self-reported physical health and frequency of cooking were statistically significantly associated with food insecurity. Using a smaller sample (n 73) collected in 2021, Ibiyemi, Najam and Oldewage-Theron found that out of seven descriptive variables, only length of time in the USA was associated with food insecurity(Reference Ibiyemi, Najam and Oldewage-Theron19). International students who had been in the USA for less than a year were statistically significantly more likely to be food insecure.

Access to cultural foods is important to consider when thinking about how best to provide food-related resources for international students. Cultural foods are those foods that international students eat in their home countries. Access to these foods can promote well-being, feelings of belonging, cultural identity development and maintenance and can alleviate acculturative stress(Reference Rodyna20,Reference Wright, Lucero and Ferguson21) . However, there is evidence that international students in the USA struggle to access cultural foods(Reference Glick, Winham and Shelley22,Reference Goldman, Freiria and Landry23) .

The present study aims to add to the literature on international college students’ experiences of food insecurity and accessing cultural foods in order to aid efforts to support international students. We address two research questions. First, what are the demographic correlates of food insecurity for international college students? Second, what are the demographic correlates of cultural food accessibility and affordability for international college students? We examined the demographic correlates of food insecurity and access to cultural foods for undergraduates and graduate students separately, given evidence from the literature that undergraduate and graduate students are two distinct groups(Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner18,Reference Goldman, Freiria and Landry23) . Graduate students seem to have lower rates of food insecurity than undergraduates(Reference Glick, Winham and Shelley22,Reference Abbey, Brown and Karpinski24) , and there are different demographic correlates of food insecurity for these two groups of students(Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner18).

Methods

Study design and participants

An online survey was conducted in November 2022, at a large public land-grant university located about 60 miles from the Mexican border in a town with just over 500,000 people. Invitations to participate in the study were sent to all international undergraduate and graduate students who were enrolled at the university’s main campus in fall 2022. International students were defined as enrolled students who were not citizens of the USA, US permanent residents, refugees, asylees or Jay Treaty status holders. In 2022–2023, international students made up 6·8 % of the total enrolment in the study university(25). Of the 3,460 international students, 335 completed the survey, a 9·7 % response rate.

Measures

Food insecurity was measured using the six-item USDA Household Food Security Survey Module with a 30-day reference period(26). We coded responses into four food security statuses: high food security, marginal food security, low food security and very low food security. We distinguished marginal food security from high food security, as increasing evidence suggests that even marginal food security is linked to adverse outcomes comparable to low or very low food security for college students(Reference Coakley, Cargas and Walsh-Dilley8,Reference Dana, Wright and Ward27) .

Cultural food accessibility was measured using the question: ‘To what degree do you agree or disagree with the following statement: I am able to find food at the (university) similar to what I am used to eating at home’ (strongly disagree, disagree, unsure/no opinion, agree and strongly agree). Cultural food affordability was measured using the question: ‘To what degree do you agree or disagree with the following statement: I can afford the food that I am culturally accustomed to on the (university) campus’ (strongly disagree, disagree, unsure/no opinion, agree and strongly agree). The following definition of cultural foods, which is based on the definition in the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Food Service Guideline Toolkit(28), was provided in the survey: ‘Cultural foods, also called traditional dishes or culturally preferred foods, is used to describe safe and nutritious foods that are based on the consumer’s cultural identity and represent the traditions, beliefs and practices of a geographic region, ethnic group, religious body or cross-cultural community’. The questions used to measure cultural food accessibility and affordability were validated with expert review and pilot testing. Subject matter experts, such as the director of the campus pantry, reviewed the questions and provided feedback. We also pilot tested the survey in a college class with thirty-six undergraduate students, including international students, at the same university where the data were collected. These students took the survey and provided feedback about the survey design and questions in interviews with the study authors.

We measured thirteen demographic characteristics: gender (woman, man, other; participants in the other category selected either ‘prefer not to answer’ or ‘non-binary’), first-generation status (no parents or guardians who earned a bachelor’s degree or higher), primary caregiver for child(ren) under the age of 18, primary caregiver for an adult with special care needs, employment status (employed v. not employed but looking for work or not employed and not looking for work), meal plan (yes v. no or not sure), off-campus housing (on campus (university housing, fraternity or sorority house), off campus, and no stable residence), vehicle ownership (participants were coded as owning a vehicle if they reported using their own vehicle in the past 30 days to get food or do other activities) and, on average, the percent of food consumed that is cultural foods. Participants were also asked to report which country they were a citizen of. We used the world location list(29) to categorise respondents into four regions: Africa, Asia, Europe and Canada, and Latin America and the Caribbean. We created a Europe and Canada category because only two Canadians were in the North America category. Age, degree (undergraduate or graduate student) and enrolment status (full time or part time) were merged into our dataset from institutional data. All data were collected anonymously.

Analyses

Frequencies and percentages were used to describe the sample. Fisher’s exact tests were performed to assess statistical differences between undergraduate and graduate students on the demographic characteristics and dependent variables (food security status, cultural food accessibility and cultural food affordability). We used ordered probit models with robust standard errors to explore associations between demographic characteristics and the three dependent variables. We fit three models for undergraduates (one for each dependent variable) and three for graduate students, for a total of six models. The lowest level of statistical significance was accepted as P < 0·05.

Results

Participant characteristics

We were able to compare our sample to the full population of international students on some of our study variables. Our sample closely matches the population of international students at the university on full-time enrolment (82 % in our sample and in the population of international students) and off-campus residence (84 % in our sample and 88 % in the population) and overrepresents graduate students (66 % in our sample v. 45 % in the population), first-generation students (31 % v. 16 %) and women (51 % v. 21 %).

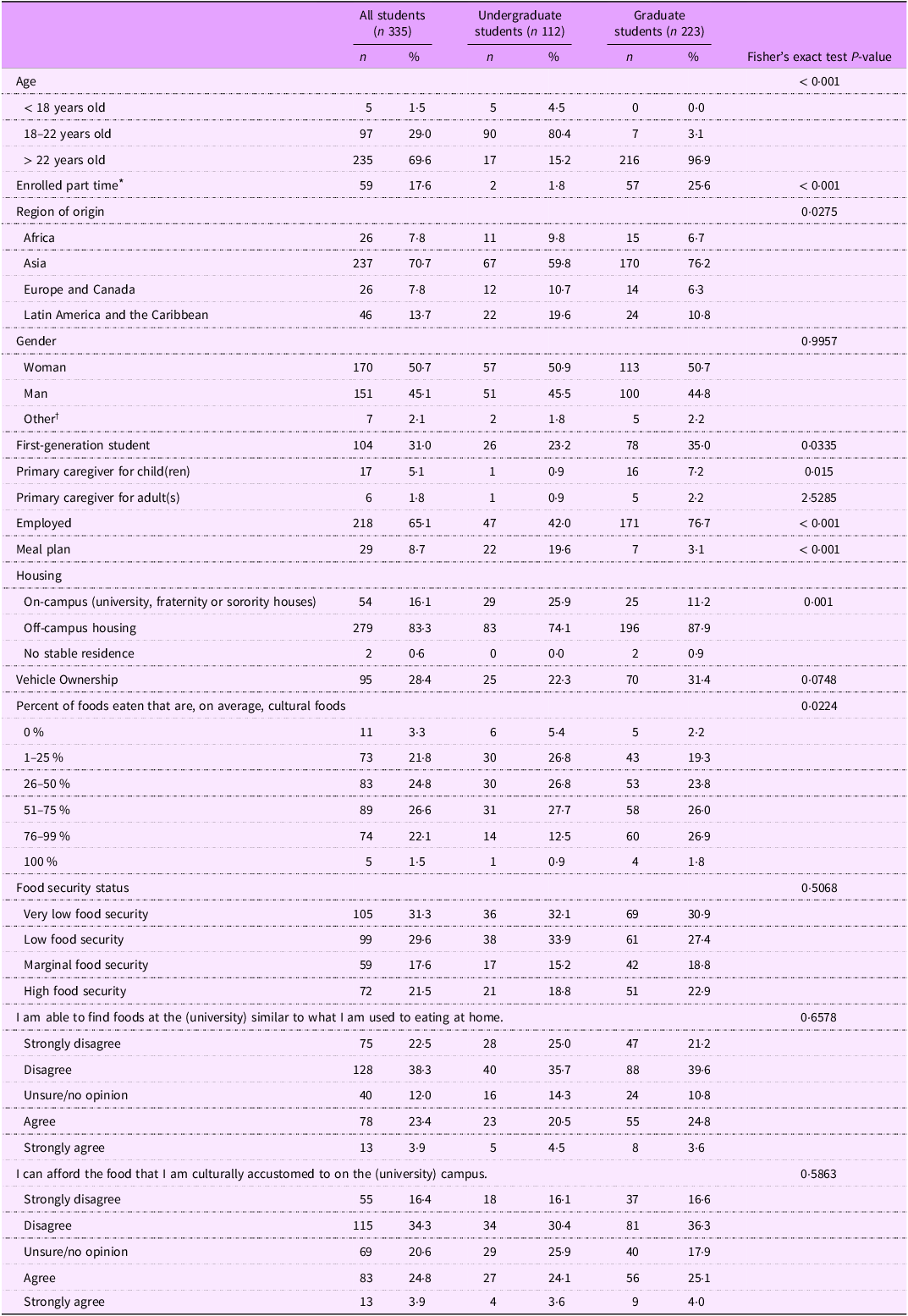

Full sample descriptives are presented in Table 1. Undergraduate and graduate students in our sample were significantly different on age, enrolment status, region of origin, first-generation status, being a caregiver for children, employment status, whether they have a meal plan, housing location and the amount of cultural food in their diet.

Table 1. Sample descriptives (n 335)

* The sample size for enrolment status was 333.

† The ‘other’ category for gender includes two participants who selected ‘non-binary’ and five who selected ‘prefer not to answer’.

About 22 % of the sample reported high food security, 18 %marginal food security, 30 % low food security and 31 % very low food security. Half of the sample reported that over 50 % of their diet was cultural foods, and only 3 % reported eating, on average, no cultural foods. About a quarter reported that they were able to find cultural foods at the university and were able to afford the cultural foods available on campus.

Demographic correlations of food insecurity

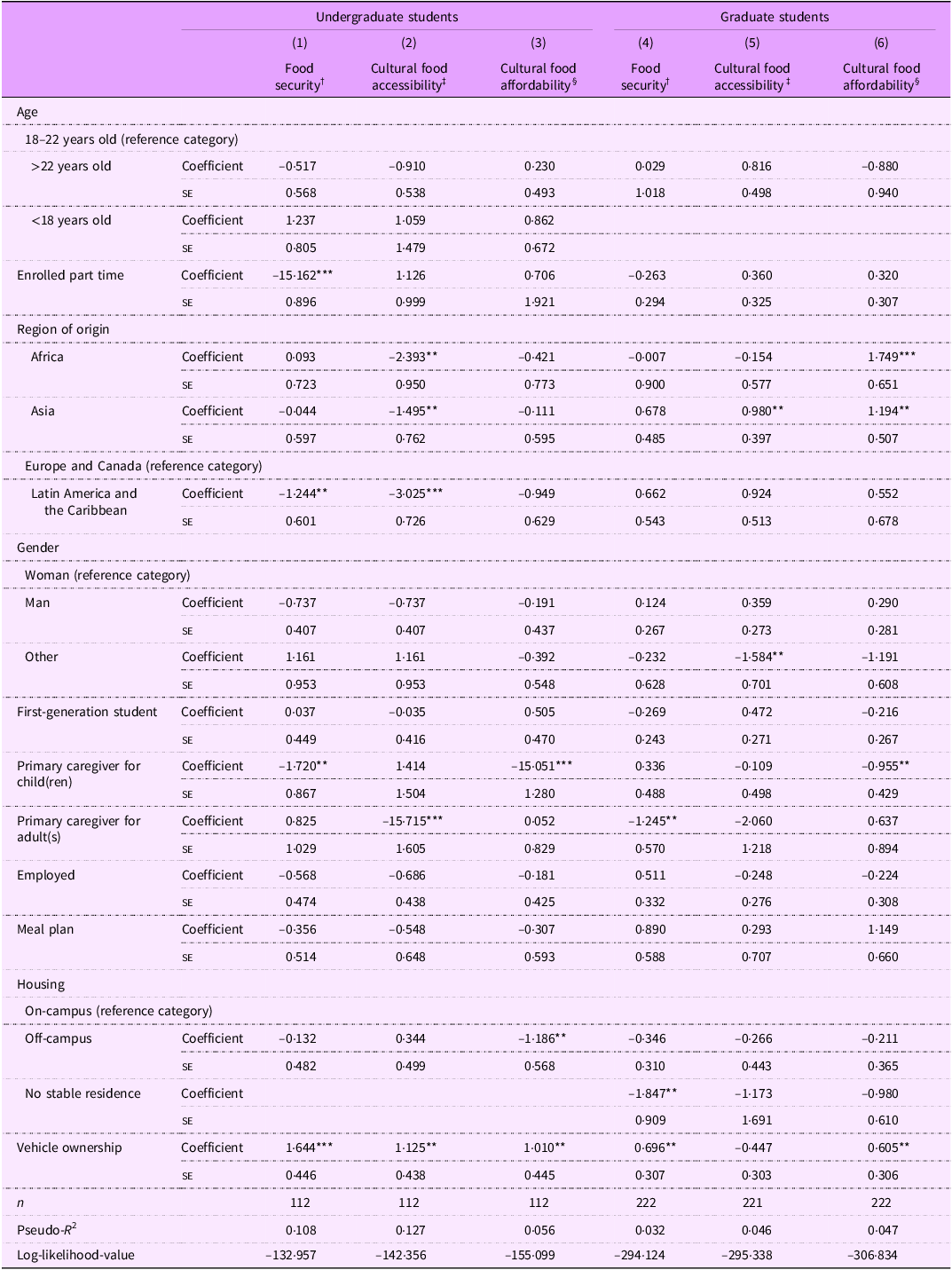

Reporting lower levels of food security was statistically significantly associated with part-time enrolment, region of origin being Latin America and the Caribbean, primary caregiver for child(ren) and not having a vehicle for international undergraduate students, being a primary caregiver for adult(s), not having a stable residence and not having a vehicle for international graduate students (Table 2, columns 1 and 4).

Table 2. Ordered probit regression results for key explanatory variables related to food security level, cultural food accessibility and cultural food affordability

** P < 0·05, ***P < 0·01.

† Food security was coded 1 = very low food security, 2 = low food security, 3 = marginal food security, 4 = high food security.

‡ Cultural food accessibility was coded 1 = strongly disagree with the statement ‘I am able to find food at the (university) similar to what I am used to eating at home’, 2 = disagree with the statement, 3 = unsure or no opinion about the statement, 4 = agree with the statement, 5 = strongly agree with the statement.

§ Cultural food affordability was coded 1 = strongly disagree with the statement ‘I can afford the food that I am culturally accustomed to on the (university) campus’, 2 = disagree with the statement, 3 = unsure or no opinion about the statement, 4 = agree with the statement, 5 = strongly agree with the statement.

Demographic correlations of cultural food accessibility and affordability

Reporting a lack of cultural food accessibility was associated with region of origin, being a caregiver for an adult and not owning a vehicle for undergraduate students. For graduate students, region of origin and identifying with a gender other than man or woman were associated with cultural food inaccessibility (Table 2, columns 2 and 5). Not being able to afford cultural foods on campus was associated with being a caregiver for children, living off campus and not owning a vehicle for undergraduate students. For graduate students, region of origin, being a caregiver for children and not owning a vehicle were associated with cultural food unaffordability (Table 2, columns 3 and 6).

Discussion

Sixty-one percent of our sample of international students at a large land-grant university reported low or very low food security, which is higher than estimates from other studies of international students, that is, between 32 and 39 %(Reference El Zein, Mathews and House11,Reference Mechler, Coakley and Walsh-Dilley12,Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner18,Reference Ibiyemi, Najam and Oldewage-Theron19) . Although all of these estimates were made using non-representative samples from one university, taken together, they suggest that international students experience high rates of food insecurity and universities should provide resources specifically for international students, especially given these students’ lack of access to federal food resources.

Our results concerning the demographic correlates of food insecurity, cultural food accessibility and affordability suggest the importance of access to a vehicle that can be used to purchase food. Vehicle ownership was associated with food security status and cultural food accessibility for undergraduate students and cultural food affordability for both undergraduate and graduate students. Soldavini, Andrew and Berner (2022) and Glick, Winham and Shelly (2025) found similar positive associations between having a car and food security in samples of international students(Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner18,Reference Glick, Winham and Shelley22) . Students have also reported having to travel off campus to find culturally appropriate foods(Reference Watson, Malan and Glik30). Glick and colleagues also found that international students were more likely than US-born white students to report lacking reliable transportation(Reference Glick, Winham and Shelley22). Owning a car is likely important because it allows students to purchase food off campus, where they can often access less expensive food(Reference Zigmont, Anziano and Schwartz31) and more authentic cultural foods. However, vehicle ownership might not be realistic for all or even many international students. Other solutions could include making sure food pantries on campus stock international foods as there is some evidence that international students are more likely to use campus pantries than US college students(Reference El Zein, Mathews and House11,Reference Glick, Winham and Shelley22) and lobbying for increased public transportation or providing university shuttles from campus to parts of the surrounding communities that have grocery stores or restaurants where cultural foods can be purchased.

Our results also suggest that the region of the world from which a student comes to the USA shapes their experiences. Region of origin was associated with food security status and cultural food accessibility for undergraduate students and cultural food accessibility and affordability for graduate students. Differences in food security status and access to cultural foods likely vary by region of origin due to both characteristics of the individual students (e.g. culinary literacy skills, knowledge and beliefs about food resources on or near campus, social support, experiences of discrimination) and the university and local community environment (e.g. the availability of holistic supports for basic and academic needs on campus; dining halls, restaurants and grocery stores selling cultural or inexpensive foods on or near campus; availability of cultural foods through food resources)(Reference Brown, Buro and Jones32,Reference DeBate, Jarvis and Perez33) . Although this exploratory study is not designed to make definitive statements about which regions of origin may predict food insecurity or lack of access to cultural foods, our findings suggest that it is likely important for researchers and student services professionals to consider differences within international students based on region of origin, rather than considering international students as one homogeneous group.

Additionally, fitting separate models for undergraduate and graduate students revealed differences between these groups. These findings, along with several studies showing that class year is related to food security status,(e.g. Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner18, Reference Goldman, Freiria and Landry23) suggest that undergraduate and graduate students should be considered separately both when conducting research and designing support programmes.

Our findings should be considered in light of study limitations. The use of a self-selected sample from one university’s international student population limits the generalisability of our findings. Our sample included only a small number of students in some groups (e.g. caregivers for children or adults with special needs and non-binary or gender non-conforming students), making it hard to draw conclusions about these groups of international students. In the future, researchers should oversample these groups in order to address questions about them. The 9·7 % response rate to our survey introduced non-response bias, although it is similar to response rates found in other studies using a similar census sampling approach for the entire university, which also report response rates below 11 %(Reference Coakley, Cargas and Walsh-Dilley8,Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner18) and a study of international students with a 4% response rate(Reference Ibiyemi, Najam and Oldewage-Theron19). Despite these limitations, our study adds to the literature by exploring food insecurity using a four-category (rather than three- or two-category) measure of food security status for a sample of international college students, an important but often ignored group, and widening the focus to include access to and affordability of cultural foods.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the students in the AREC/NAFS 365 Fall 2022 class at the University of Arizona (UA) for their help with survey development and data collection and Reese Branham for being an excellent undergraduate research assistant. We also thank the UA Campus Pantry, the Office of Assessment and Research and the Dean of Students for their invaluable partnerships that helped facilitate data collection and Bridgette Riebe, Kendra Thompson-Dyck, Lin Zhang and Dr. Anna Josephson for their insights and expertise. These partnerships would not have been possible without the support of the UA Experiential Learning Design Accelerator programme and the Course-based Undergraduate Research Experience Training Institute. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the participants, who generously shared their time, experiences and insights.

Financial support

This research was partly supported by the University of Arizona Hispanic Serving Institution Seed Grant project ‘Food Insecurity Among College Students: Understanding Hunger at the University of Arizona’. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University of Arizona. The funders had no role in any aspect of the study or its publication.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authorship

N.Z. and K.S. conceptualised the study. N.Z. and A.J. performed all data analyses. All authors interpreted the data, wrote and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics of human subject participation

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Arizona (IRB ID: STUDY00000185). Electronic written informed consent was obtained from all participants.