Introduction

The United States produces less than 2% of the world’s rice, totaling about 6.93 million metric tons in 2023. Despite this small share, it ranks as the fifth-largest exporter, supplying 5% of global rice exports, largely due to high demand for U.S. rice varieties (USDA, 2023). Roughly half of U.S.-produced rice is consumed domestically, accounting for 80% of the nation’s rice consumption, while the other half is exported to over 120 countries, including Mexico, Canada, and Haiti (USA Rice Federation, 2020; USDA ERS, 2023, 2024). The U.S. rice industry significantly impacts rural employment, contributing over $34 billion to the economy annually and supporting more than 125,000 jobs (USA Rice Federation, 2020). However, factors such as insect infestation and environmental degradation pose significant threats to the rice sector, leading to reduced rural income and economic stability.

Stored rice is affected by insect infestation, mold, and heat damage, all of which can lead to economic losses. Pest attacks not only reduce grain weight but also increase the risk of mycotoxin contamination. According to the World Health Organization, ‘mycotoxins are naturally occurring toxins produced by certain molds (fungi) and can be found in food’. Mold, which tends to grow under warm and humid conditions, can contaminate agricultural products like crops and grains, causing adverse health effects to both humans and livestock (WHO, 2023). Aflatoxin and fumonisin are key mycotoxins that can render rice unsuitable for human and animal consumption, posing risks to food and feed safety. For instance, aflatoxin exposure can lead to acute illness and, in severe cases, liver cirrhosis. In April 2004, a significant aflatoxicosis outbreak occurred in rural Kenya, resulting in 317 cases and 125 deaths, with maize samples from the affected area showing high aflatoxin B1 concentrations (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Onsongo, Njapau, Schurz-Rogers, Luber and Kieszak2005).

Additionally, environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and day length affect insect populations after harvest (Tefera et al., Reference Tefera, Kanampiu, De Groote, Hellin, Mugo and Kimenju2011), leading to increased use of insecticides. Rice is particularly vulnerable to infestation by multiple insect species post-harvest, especially during warmer months like June or July, when conducive conditions facilitate rapid insect reproduction (Tefera et al., Reference Tefera, Kanampiu, De Groote, Hellin, Mugo and Kimenju2011; de Sousa et al., Reference de Sousa, Oliveira, Mexia, Barros, Almeida, Brazinha, Vega and Brites2023). The risk of infestation is worsened by flying insects that often migrate from fields or infested grain bins to newly stored rice (Tefera et al., Reference Tefera, Kanampiu, De Groote, Hellin, Mugo and Kimenju2011). Insecticides are commonly relied upon to manage insect populations, often being the primary method for controlling infestation (Harien and Davis, Reference Harien, Davis and Sauer1992). However, they are frequently inaccessible or too costly for farmers, requiring cost-effective pest control practices for storage (Tefera et al., Reference Tefera, Kanampiu, De Groote, Hellin, Mugo and Kimenju2011). Also, insects are developing resistance to common fumigants like phosphine gas and non-fumigant insecticides like Malathion, presenting challenges and requiring higher pesticide dosages, which could exacerbate the issue (Zettler and Cuperus, Reference Zettler and Cuperus1990; Zettler and Beeman, Reference Zettler, Beeman, Krischik, Cuperus and Galliart1995).

Post-harvest losses contribute to environmental degradation and climate change, as non-renewable inputs such as fertilizer, water, and energy are expended during the production, processing, storage, and transportation of food that is ultimately not consumed (FAO, 2008; World Resources Institute (WRI) et al., 2023). These inefficiencies result in avoidable greenhouse gas emissions across the supply chain, while food discarded in landfills further exacerbates climate change through anaerobic decomposition and methane release (FAO, 2013). Climate change, in turn, intensifies post-harvest losses by accelerating spoilage, altering pest and disease pressures, and disrupting traditional storage conditions (Srivastava, Reference Srivastava, Choudhary, Kumar and Singh2019; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ejaz, Anjum, Nawaz, Ahmad and Hossain2020). Chegere (Reference Chegere2018) found that climate variability significantly affects post-harvest efficiency, particularly in developing regions with limited access to adaptive technologies. Reducing post-harvest losses, therefore, presents a dual opportunity: improving food system efficiency while contributing to climate change mitigation.

Traditional methods of pest control for stored grain in elevators are under pressure due to environmental concerns and rising costs. Grain elevator managers employ various pest control methods, including grain turning and blending, aeration, temperature control, sanitation, and primarily chemical control, such as fumigation. However, an overreliance on chemical control persists due to the prevalence of pest infestations and resistance levels. Concerns over environmental impact prompted the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, 2018) to ban methyl bromide, an ozone-depleting fumigant, effective January 2005 (Fields and White, Reference Fields and White2002). Also, fumigation application to control pest infestations results in increased time and costs for grain elevator managers. This is especially the case as mills mostly adhere to a strict 100% pest mortality policy when accepting grains from elevators for packaging and shipping to retailers and consumers. Despite the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) allowance of certain levels of contaminants in food products, such as certain levels of insect fragments (like legs, heads, and body parts) and rodent hairs, mills, exemplified by Riviana Foods Inc., prioritize consumer satisfaction and maintain stringent standards. Any contamination incident could incur significant costs due to product recalls, necessitating the tracing back of entire shipments.

Atmospheric cold plasma (ACP) is a novel and emerging pest control treatment technology with potential to disrupt critical physiological processes in insects, akin to synthetic insecticides (Los et al., Reference Los, Ziuzina, Van Cleynenbreugel, Boehm and Bourke2020), while also addressing current environmental issues. Studies have investigated ACP’s impact on various developmental stages of pests, including rice weevils, from eggs to pupae (Chaplot et al., Reference Chaplot, Yadav, Jeon and Roopesh2019; Kirk-Bradley et al., Reference Kirk-Bradley, Salau, Salzman and Moore2023, Reference Kirk-Bradley, Hujon, Rohilla, Burciaga, Zhu-Salzman and Moore2024). This plasma treatment combines charged particles, UV radiation, and reactive species like ozone and hydroxyl radicals, causing morphological alterations and cellular damage through etching effects (Bourke et al., Reference Bourke, Ziuzina, Han, Cullen and Gilmore2017). ACP is a non-thermal, ionized gas generated at room temperature that effectively targets pests such as Tribolium castaneum (red flour beetle) and Callosobruchus maculatus (cowpea weevil) without damaging heat-sensitive materials (Patil et al., Reference Patil, Moiseev, Misra, Cullen, Mosnier, Keener and Bourke2014; Han et al., Reference Han, Boehm, Amias, Milosavljević, Cullen and Bourke2016; Chaplot et al., Reference Chaplot, Yadav, Jeon and Roopesh2019; Los et al., Reference Los, Ziuzina, Van Cleynenbreugel, Boehm and Bourke2020; Rana et al., Reference Rana, Mehta, Bansal, Shivhare and Yadav2020; Kirk-Bradley et al., Reference Kirk-Bradley, Salau, Salzman and Moore2023). Kirk-Bradley et al. (Reference Kirk-Bradley, Hujon, Rohilla, Burciaga, Zhu-Salzman and Moore2024) underscore ACP’s value in pest control for stored grains, achieving significant mortality rates across developmental stages. This aligns with work by Kaur, Hüberli and Bayliss (Reference Kaur, Hüberli and Bayliss2020), who observed reduced pest and fungal loads in stored grains treated with cold plasma in Australia. ACP’s low-temperature operation prevents heat damage and avoids the toxic residues and environmental risks associated with chemical pesticides (Lopes-Ferreira et al., Reference Lopes-Ferreira, Maleski, Balan-Lima, Bernardo, Hipolito, Seni-Silva, Batista-Filho, Falcao and Lima2022; Panis et al., Reference Panis, Kawassaki, Crestani, Pascotto, Bortoloti, Vecentini, Lucio, Ferreira, Prates, Vieira and Gaboardi2022). Additionally, Okumura et al. (Reference Okumura, Tanaka and Nakao2023) found no adverse health effects on the grains harvested from plasma-irradiated seeds.

Rice mills and drying/storage facilities provide an ideal setting for evaluating new pest control technologies like an ACP fumigation chamber. These facilities handle large grain volumes that require extensive drying, storage, and pest management, making them prime environments for assessing cost-saving innovations (Tefera et al., Reference Tefera, Kanampiu, De Groote, Hellin, Mugo and Kimenju2011). A sizeable portion of the revenue in this industry comes from storage fees per hundredweight (cwt) per day, so any technology that reduces downtime, lowers energy usage, or improves pest control efficiency can significantly impact profit margins. Additionally, the continuous, high-volume turnover in these facilities emphasizes the need for rapid and effective pest control methods, aligning well with the ACP fumigation chamber’s potential (Phillips and Burkholder, Reference Phillips, Burkholder, Bakker-Arkema and Maier1996). Rice milling and drying/storage facilities also face economic constraints due to rising costs associated with traditional pest control methods. Fumigants have become more expensive due to regulatory requirements, pest resistance, and the need for precise applications to preserve grain quality (Ucar et al., Reference Ucar, Ceylan, Durmus, Tomar and Cetinkaya2021; Birania et al., Reference Birania, Attkan, Kumar, Kumar and Singh2022). These conditions make agricultural facilities particularly receptive to new approaches that can help mitigate these expenses.

Kirk-Bradley et al. (Reference Kirk-Bradley, Salau, Salzman and Moore2023, Reference Kirk-Bradley, Hujon, Rohilla, Burciaga, Zhu-Salzman and Moore2024) developed a custom-designed chamber system to assess the effectiveness of ACP as an alternative fumigation method for stored grain pest management. Figure 1 presents the schematic diagram of the ACP system setup reproduced from Kirk-Bradley et al. (Reference Kirk-Bradley, Salau, Salzman and Moore2023), where a detailed explanation of the setup is provided. By generating reactive gas species from compressed air, the chamber created controlled conditions to target and eliminate insect pests while minimizing chemical residues and environmental impact. Although not yet commercially available, this system presents a scalable approach to improving grain storage and protection (Kirk-Bradley et al., Reference Kirk-Bradley, Salau, Salzman and Moore2023). Recently, studies have found the ACP technology to be a sustainable approach to pest management (Okumura et al., Reference Okumura, Tanaka and Nakao2023; Kirk-Bradley et al., Reference Kirk-Bradley, Hujon, Rohilla, Burciaga, Zhu-Salzman and Moore2024; Dilip et al., Reference Dilip, Modupalli, Rahman and Kariyat2025). However, to the authors knowledge, none has analyzed the economic feasibility of adopting it using the operations of existing companies as case examples. This study aims to fill this gap in the literature.

Figure 1. Schematic of experimental laboratory setup using dielectric barrier discharge atmospheric cold plasma system (Kirk-Bradley et al., Reference Kirk-Bradley, Salau, Salzman and Moore2023).

This study evaluates the economic feasibility of using Kirk-Bradley et al.’s (Reference Kirk-Bradley, Salau, Salzman and Moore2023, Reference Kirk-Bradley, Hujon, Rohilla, Burciaga, Zhu-Salzman and Moore2024) custom-designed ACP fumigation chamber for pest control in stored rice relative to the traditional Weevil-Cide (Aluminum Phosphide Pellets) fumigation methods. The researchers employ two methods to assess economic feasibility: net present value analysis and an input–output model for evaluating broader economic impacts. The authors hypothesized that utilizing the ACP fumigant with reactive gas species would reduce hold times, enabling drying facilities to lower costs and boost profitability. The techno-economic analysis is conducted on two grain-drying and storage facilities and one rice milling company in Texas, and the broader economic impact is assessed for the United States.

The study found three key results. First, profitability in rice drying and storage companies is closely tied to the volume processed and stored. Although the authors anticipated that the ACP fumigation chamber would yield significant cost savings, our investment analysis showed that operating costs outweighed revenue for both grain-drying and storage facilities, suggesting that relying solely on storage and fumigation fees may not be economically sustainable. Second, the milling company experienced improved profitability with the ACP fumigation chamber, suggesting that ACP technology could potentially offer more economic benefits to milling operations than the traditional fumigation method. Third, commercializing the ACP technology across 10%–75% of existing drying facilities in the United States could yield an economic impact of $77 million to $580 million. Overall, the findings suggest that the decision to adopt ACP in the agricultural sector for rice and other grains is influenced by the market focus and business type.

Data and methodology

Data collection

The authors identified the various components used to build the custom-designed ACP fumigation chamber in Kirk-Bradley et al. (Reference Kirk-Bradley, Salau, Salzman and Moore2023, Reference Kirk-Bradley, Hujon, Rohilla, Burciaga, Zhu-Salzman and Moore2024). The reactive gas species (RGS) produced by ACP fit into the ‘chemical’ category on the Integrated Pest Management (IPM) chart (see Fig. 2). While ACP itself is a physical treatment method, the reactive gas species it generates can be viewed as chemical agents that interact with pests, disrupting their physiology and ultimately causing mortality. These reactive gas species are generated by ionizing compressed air within the ACP chamber using electrical energy, producing a mixture of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, including ozone (O3), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), and nitric oxide (NO). This allows for more efficient insect control (Kirk-Bradley et al., Reference Kirk-Bradley, Hujon, Rohilla, Burciaga, Zhu-Salzman and Moore2024). Therefore, within the framework of IPM, both ACP and its reactive gas species are classified under the chemical category, along with other chemical pest control methods (Gaunt, Beggs and Georghiou, Reference Gaunt, Beggs and Georghiou2006). The ACP chamber was scaled up to accommodate the operations of the rice milling company and the drying and storage facilities.

Figure 2. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) chart for pest of animals and humans.

The authors consider the case study of two grain elevator companies (drying and storage facilities) and one rice milling firm in Texas. While this study includes only three companies, they were selected to reflect a range of facility sizes and operational capacities typical of rice storage and milling companies in Texas. Additionally, because these companies use conventional rice drying techniques and pesticides, they provide an ideal context for collecting data and comparing it with the emerging ACP technology. Company X, a small-to-medium-sized rice drying and storage company with 44 silos capable of storing 110 million cwt (hundredweight, equivalent to 244.44 million bushels), (2) Company Y, a large rice drying and storage facility, with over 160 silos across various state locations and a storage capacity of 400 million cwt (equivalent to 888.89 million bushels), and (3) Company Z, a rice milling company that operates a 465,000 square foot facility, with a production capacity of 2.5 million cwt.

Company Y is one of the largest players in the region, while Company X represents small-to-medium-sized facilities that are common in rural storage networks. These facilities play a significant role in serving the rice industry, farmers, and communities. The three firms utilized Phostoxin as the fumigant to control pests in stored grains, serving as the benchmark for comparison against the proposed RGS fumigant derived from ACP. This allows for a direct evaluation of the effectiveness and cost-efficiency of the novel fumigation approach in contrast to the conventional method. Thus, the selection of companies in this study enables a grounded evaluation of fumigation practices across different contexts. Nonetheless, the authors acknowledge that the findings may not capture the full heterogeneity of the broader sector, especially across other states or grain types.

The raw data were initially collected through a series of site visits, virtual meetings, and phone calls to ensure accurate transcription. The authors conducted in-person interviews with each of the case study companies between April and June 2024. The data collected included cost and revenue values for 2023, along with other operational information such as capacity and quantity of grain stored. Follow-up phone conversations and virtual meetings were also held during this period to allow for further clarification. However, most of the data were collected through field investigations with each company’s permission to include in this study.

For each company, the initial traditional technology cost encompassed the expense of a silo and the associated fan utilized for aeration (Table 1). Operational expenses comprised the following items: an auger (AGI Westfield WR 6) required for rice transportation, a gas monitor system (Dräger Pac® 8000) used to measure the parts per million (ppm) levels of the fumigant after it had been applied and held for the duration of the treatment, prior to its release into the air, along with a replacement battery. Phostoxin Weevil-Cide pellets (from Triton Fumigation LLC) were used for fumigating the rice, Tempo SC Ultra Insecticide for treating the bins before loading them with rice, and a sample probe for detecting insects at various depths within the grain. Additionally, labor costs (comprising hours worked, number of workers, and pay rate) and electricity expenses to power the fans were included.

Table 1. Capacity and cost of case study companies: traditional and custom-designed ACP fumigation chambers

Note: The quantity and cost reflect annual values.

* Reflects year 1 operating costs only.

Table 2 presents the cost structures of the traditional fumigation technology currently being used by our case study companies, as well as the custom-designed ACP technology. The ACP fumigation chamber employs a fundamentally different set of technology and equipment. The ACP system does not utilize many of the traditional components (e.g., silos, augers, Phostoxin pellets); instead, it relies on specialized items such as air stones, shipping containers, valves, and other ACP-specific hardware. The major components to construct the ACP technology include the shipping container, a Shutter Mount Exhaust Fan, ozone monitor, ozone generator, and transformer. The initial cost to construct the ACP fumigation chamber was estimated at $34,315 (Table 1).

Table 2. Detail cost structures of traditional fumigation and ACP fumigation chamber

Note: ‘n/a’ value indicates that this item or equipment was not utilized in the construction or operation of the structure. For example, where ‘n/a’ currently appears in the ACP Technology column, it indicates that those are Traditional Technology items only and are not used or included in the ACP Technology system, vice versa.

Methodology

The process of assessing the economic feasibility of ACP relative to traditional pest management methods involved several steps. First, the authors outlined the data and conversions necessary from each company to generate a comprehensive cost–benefit analysis regarding fumigation. This analysis will serve as the basis for evaluating the approximate financial implications of the fumigation methods.

Second, several assumptions were made when analyzing the data. The authors estimated the longevity of each expense, whether it was for initial technology or operational expenses. For instance, considering that both grain-drying and storage facilities were established in 1962, and the silos were constructed even earlier, the authors approximate the lifespan of modern silos based on similar styles and sizes. According to information from Advanced Grain Handling Systems Inc. (AGHS, n.d.), modern silos typically last for a minimum of 15 years, especially fiberglass or plastic types, while steel and concrete silos generally last 20–30 years, depending on material quality and maintenance, before requiring substantial maintenance costs (Bidragon Silo, 2024). A 20-year useful life was assumed for both the traditional and ACP technologies, thereby avoiding the need to introduce additional assumptions regarding major repairs.

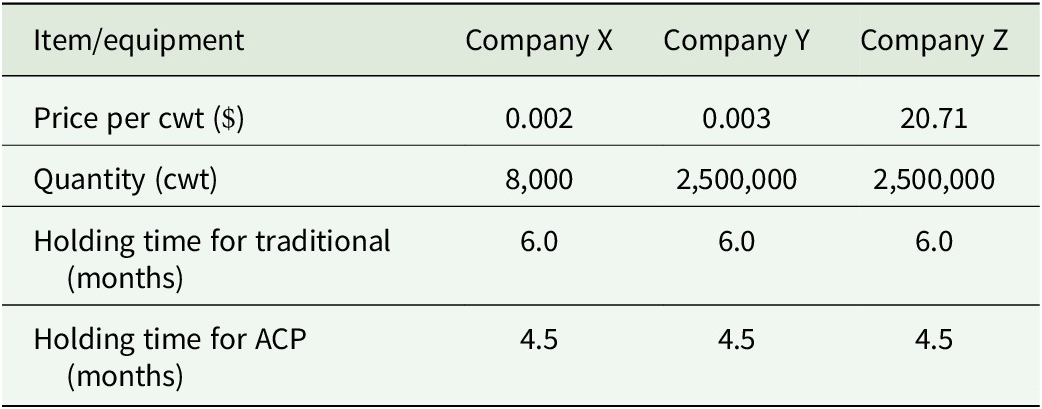

Other assumptions were made regarding the duration of grain storage. Based on discussions with both company types, the average hold time ranged from 3 to 6 months. For our ACP analysis, the authors took a conservative approach and used a hold time of 4.5 months. This figure significantly influenced the revenue calculation for the drying and storage companies since each facility charged farmers between $0.002 and $0.003 per cwt per day for storing their grain. Holding time also impacts labor costs by increasing the number of labor days allocated to rice storage activities. The authors estimated 8 days per year for three workers under the ACP technology and 10.5 days under the traditional technology.

The authors calculated a mill revenue of $20.71 per cwt. This value is derived from the 2022 USDA’s food dollar value for wholesale trade (10.7 cents) and farm production (7.9 cents), totaling 18.6 cents. According to the USDA, wholesale trade is ‘all non-retail establishments that resell products for the purpose of contributing to the U.S. food supply’, and farm production is ‘all establishments classified as farms in the agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting industries’. Since the 18.6 cents represent the market price of $36 per cwt, the authors used the ratio (10.7/18.6) and applied it to the $36 per cwt. Table 3 provides the revenues of each case study company based on its financial performance in 2023.

Table 3. Revenue structure of case study companies

The authors used the net present value (NPV) to determine the financial feasibility of the proposed ACP fumigation chamber technology and the traditional fumigation methods. The NPV is typically the preferred financial metric tool by managers when comparing projects to make investment decisions (Gallo, Reference Gallo2014). Companies often prefer NPV because it accounts for the time value of money, translating future cash flows into current dollars, and provides a more precise figure for managers to compare the initial cash outlay against the present value of the return. The NPV represents the present value of the technology’s expected cash flows discounted at the required rate of return, minus the initial investment. The authors determine the project’s viability by converting all expected returns from the investment into present-day dollars. Net cash flow was calculated by subtracting total cash expenses from total cash sales or revenue. The discount rate utilized in the analysis was sourced from the U.S. Treasury average long-term government bond discount rate, representing a value of approximately 4%.

For the NPV analysis, the following equation is utilized:

$$ NPV=\sum \limits_{t=0}^T\left(\left({B}_t-{C}_t\right)\times {\left(1+i\right)}^{-t}\right),\hskip3.959998em $$

$$ NPV=\sum \limits_{t=0}^T\left(\left({B}_t-{C}_t\right)\times {\left(1+i\right)}^{-t}\right),\hskip3.959998em $$

-

•

$ {B}_t $

= Cash inflow (benefit) in dollars in year t.

$ {B}_t $

= Cash inflow (benefit) in dollars in year t. -

•

$ {C}_t $

= Cost or cash outflow in dollars in year t.

$ {C}_t $

= Cost or cash outflow in dollars in year t. -

• 𝑖 = Interest rate (sourced from US Treasury average long-term government bond interest rate, 4%). A higher 𝑖 denotes a higher uncertainty or risk.

-

• T = Number of years/life of project.

If

![]() $ NPV>0 $

: The project is expected to generate positive returns and is profitable or viable.

$ NPV>0 $

: The project is expected to generate positive returns and is profitable or viable.

If

![]() $ NPV=0 $

: The project breaks even, generating returns equal to the initial investment.

$ NPV=0 $

: The project breaks even, generating returns equal to the initial investment.

If

![]() $ NPV<0 $

: The project is expected to generate negative returns and is not financially viable.

$ NPV<0 $

: The project is expected to generate negative returns and is not financially viable.

The authors conducted a multi-period techno-economic analysis with a time horizon corresponding to the asset’s expected life. The duration of the project, denoted by the number of years (T), is contingent upon the longevity of the technology. While silos can endure for an extended period with regular and sometimes costly repairs, the fumigation chamber is estimated to have a lifespan of up to 20 years. Therefore, the techno-economic analysis was conducted over a 20-year period. Regarding salvage value, it was assumed to be zero, as the analysis covers the full 20 years, representing the complete depreciation of the technology.

Each component of the ACP technology incurs an associated depreciation cost as part of its operating expense, and, given their finite life expectancies, these components may need to be replaced multiple times over the 20-year lifespan of the technology. For example, the replacement battery has a lifespan of 2 years, meaning it will need to be replaced after 2 years of use. This is similar for other components such as the gas monitor, probes, and ozone monitor. These depreciation values and replacement costs were included in the NPV calculation to obtain more precise financial projections.

A sensitivity analysis was also conducted to test the robustness of the NPV results for the ACP technology. Adjustments were made to key assumptions that could impact the economic feasibility, such as the operational costs, storage volumes, and the discount rate. The authors assumed a

![]() $ \pm 5\% $

change in operational costs, a

$ \pm 5\% $

change in operational costs, a

![]() $ \pm 25\% $

variation in operational volume capacity, and a

$ \pm 25\% $

variation in operational volume capacity, and a

![]() $ \pm 2 $

percentage point change in the discount rate.

$ \pm 2 $

percentage point change in the discount rate.

To estimate the economic impact of the ACP technology for rice drying in the United States, the authors used the Impact Analysis for Planning (IMPLAN) input–output modeling system to calculate direct, indirect, and induced economic effects. IMPLAN is a widely used regional economic analysis tool that quantifies the interdependencies among different sectors of the economy within a defined geographic area. IMPLAN relies on input–output (I–O) analysis, originally developed by Wassily Leontief, to represent the flow of goods and services between industries. In this paper, the I–O analysis measures the ripple effects of the ACP technology in other industries through input purchases, labor payments, and trade (Clouse, Reference Clouse2019). The direct effects are the initial economic activity generated in the economy by spending related to the ACP technology, the indirect effects are the business-to-business spending in the supply chain that stems from the ACP technology input purchases, and the induced effects measure spending of the employees within the technology’s supply chain (Demski, Reference Demski2025).

The analysis incorporated capital investment spending associated with the direct economic activity generated by the ACP technology’s potential introduction and deployment. Capital spending per unit of $34,315 was allocated across relevant IMPLAN industries, including construction of new commercial structures (including farm structures), construction machinery manufacturing, and engineering and related services, to reflect installation and equipment costs. This direct economic impact of the technology’s potential commercialization is magnified through the local economy, and the overall effect is captured by the derived economic output, value-added, labor income, tax revenue, and employment indicators. Output measures gross business activity and represents gross expenditure resulting from direct, indirect, and induced business activity. Value-added measures economic output minus intermediate purchases from other sectors and represents the industry’s contribution to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). Labor income represents the total value of all forms of employment income and includes employee compensation (salary, wages, and benefits) and sole proprietor income. Employment represents the number of full-time, part-time, and seasonal employees, including sole proprietors. Tax revenue measures total taxes paid by businesses and households at the federal, state, and county levels.

To evaluate variation in technology uptake, firm adoption scenarios of 10%, 50%, and 75% were modeled. According to a World Grain article, the United States had 8,068 off-farm storage facilities in 2022 (Reidy, Reference Reidy2023). The adoption rate assumption was based on this conservative number, where it was assumed that each facility used fumigation practices on at least one drying and storage grain elevator. Each scenario was run independently to estimate how different levels of technology penetration affect economic outcomes in the U.S.’s economy. IMPLAN’s multipliers were then used to quantify indirect supply chain effects and induced household-spending effects, producing estimates of total employment, labor income, value added, output, and tax revenues. This approach allows for comparing the relative magnitude of economic impacts across adoption levels and provides a transparent and replicable framework for assessing the broader economic implications of emerging agricultural technologies.

Results and discussion

Net present value

The data showed that both drying and storage companies incurred operational expenses that outweighed revenue, despite having grain storage fees equivalent to the traditional fumigation technique, resulting in losses from $141,037 to over $2.6 million (Table 4). The ACP technology was found to use approximately $56,000 less in electricity per unit per year, due primarily to the increased efficiency resulting from the removal of insects in the grains. Despite the ACP fumigation chamber’s ability to eradicate more than 75% of the total insect population within 24 hours, which reduced hold times and electricity costs, the generated revenue remained insufficient to offset the accrued operational expenses over time. Revenues were low due to the drying and storage facilities charging farmers a daily storage fee of $0.003 or less per cwt.

Table 4. NPV results: traditional and ACP

Note: Values in parentheses are negative.

One potential reason for the high operational expenses in drying and storage-only facilities is the mismatch between the ACP chamber’s current treatment capacity and the operational scale of these facilities. Unlike milling operations, which typically handle continuous, high-throughput grain processing, drying/storage facilities may have more intermittent treatment needs. The underutilization of facility chambers prevents the fixed costs of the system from being distributed over enough volume to reach economies of scale. Additionally, traditional storage relies heavily on existing infrastructure like large silos and central aeration, which are not leveraged by the ACP system, creating a redundancy in operational overhead. These factors, combined with limited revenue generation from storage fees alone (Kenkel, Reference Kenkel and Rosentrater2022; Mouza, Reference Mouza2024), contribute to the observed negative NPVs. This underscores that the target market for this technology requires an industry with a diversified revenue source and a high-value product. Future research could explore modular or smaller-scale ACP units tailored to storage facilities, or mobile models that allow cost-sharing across multiple sites.

The NPV analysis showed that the ACP technology presents a financially viable opportunity for the rice milling company, with an estimated NPV exceeding $555 million over the 20 years, approximately $1.5 million higher than the NPV value for the traditional technology (Table 4). This profitability is partly due to mills capturing a greater share of consumer food spending, estimated at 20.7 cents per dollar. Based on the USDA’s breakdown of the U.S. dollar, this higher revenue share enables mills to better absorb operational costs and pass on savings or quality improvements to customers. With rice priced at an average of $36 per cwt, the ACP technology is projected to generate an additional $88,487 in revenue by treating 2.5 million cwt of rice in the first year, compared to that of the traditional technology. These mills are well-positioned to benefit from the chamber’s favorable NPV outcome due to higher revenue generation than storage-only facilities (Alexander and Kenkel, Reference Alexander and Kenkel2012; Kenkel, Reference Kenkel and Rosentrater2022).

The sensitivity analyses showed positive NPV values for the ACP technology (Table 4). As expected, profitability outcomes are better than those of the traditional technology in improved scenarios, such as lower discount rates, higher volume capacity, and decreasing operating costs. Additionally, the milling company is expected to surpass the traditional technology’s NPV even when operating costs are 5% higher. However, the milling company experiences reduced profitability with higher discount rates and lower volume capacity. Consequently, the results indicated that the mill company is more adversely affected by lower volumes than by higher costs.

Economic impact

The adoption rate of the ACP fumigation chamber by the milling, as well as the drying and storage companies, positively influences the overall economic impact in the United States, particularly when accompanied by increased capital investment. In Fig. 3, the economic impact results from the IMPLAN analysis of the commercialization of the ACP technology under each adoption scenario (10%, 50%, and 75%) are presented in a panel format (a–c). Each subfigure presents the impacts by economic indicator (employment, labor income, value added, output, and tax revenue) and by type of impact (direct, indirect, and induced). In Fig. 3a, a 10% adoption rate (806 units) results in a total economic output of $77.2 million. This economic activity supports 273 jobs, generates $23.3 million in labor income, and contributes $38.3 million to GDP (value-added). Economic activity under this scenario generates a combined tax revenue of $8.3 million at the federal, state, and county levels. However, in Fig. 3c, total economic output is estimated at $580 million with a 75% adoption rate (6,051 units). This supports over 2,000 jobs, $174.7 million in labor income, and creates a value of $287.6 million. Economic activity in this scenario of the analysis generates a combined tax revenue of $62.1 million at the federal, state, and county levels.

Figure 3. Initial capital expenditure economic indicators by impact and adoption rate.

Figure 3 also shows that the direct effects of the ACP investment contribute 37% of total output, while the supply chain effects and the additional household spending add 34% and 29%, respectively. Additionally, the ripple effects of the direct ACP investment support other industries such as flat glass manufacturing, other concrete product manufacturing, and iron, steel pipe, and tube manufacturing from purchased steel. The occupation categories with the most impacted jobs include wholesale—other durable goods merchant wholesalers, management of companies and enterprises, employment services, truck transportation, and other real estate. These results highlight the emerging technology’s role in driving economic activity across multiple sectors and occupations.

Discussion

The ACP fumigation chamber, which can reduce pest populations quickly, was initially hypothesized to be cost-effective for facilities dependent on grain storage and processing. However, our findings indicate that relying solely on storage fees does not sufficiently offset the chamber’s operational costs, suggesting that revenue from storage alone may not make ACP implementation immediately profitable in traditional storage setups. Recognizing these financial pressures, many grain drying and storage facilities are already diversifying their revenue streams. Through our interviews, some facilities are expanding services to include the production and marketing of premium rice varieties (e.g., organic or specialty rice) and high-quality seeds. Such diversification helps mitigate the high costs associated with storage and fumigation. For example, should a pest infestation occur, a mill may charge the grain drying and storage facility $300 to $400 per truck for re-fumigation, or reject the shipment entirely, potentially resulting in additional freight charges of up to $1,200. These costs further underscore the importance of diversified revenue models for these facilities.

Additionally, the global rice market’s demand for higher quality and regulatory compliance adds to the appeal of ACP technology in milling companies. With international standards becoming increasingly stringent, ACP’s potential to reduce chemical residues offers a significant advantage for exported rice products (Ucar et al., Reference Ucar, Ceylan, Durmus, Tomar and Cetinkaya2021). This aligns with consumer expectations for more sustainable, residue-free agricultural practices, providing mills with access to premium markets where quality assurance is a priority. While ACP technology may not yet be economically feasible for traditional drying and storage-only facilities, rice mills, particularly those with diversified operations, present an ideal setting for its use. By reducing pest-related losses, meeting quality standards, and potentially opening new markets, ACP technology aligns well with the operational and financial objectives of modern rice milling operations.

An alternative market worth exploring is global freight shipping, which typically commands higher revenue streams and potentially greater profitability (Grzelakowski, Reference Grzelakowski2018). This is driven by increasing global efforts to reduce chemical inputs in agriculture, emphasizing the urgent need for sustainable and low-chemical pest management solutions (Brunelle et al., Reference Brunelle, Chakir and Carpentier2024). Additionally, strict international phytosanitary regulations require effective treatments to prevent the spread of pests via traded goods, thereby increasing demand for reliable and chemical-free fumigation methods. The complexity and cost of global freight logistics, compounded by high freight rates and ongoing supply chain disruptions (UNCTAD, 2023), create strong incentives for stakeholders to minimize postharvest losses and maintain product quality during transport. Furthermore, compliance with sanitary and phytosanitary measures is critical for sustaining access to international markets, especially for vulnerable economies reliant on exports (WTO, 2023). These factors collectively contribute to the higher revenue potential in the global freight shipping market compared to traditional domestic markets, making it an attractive target for innovative fumigation technologies like ACP. The expansion into these markets allows for increased production and capital investment, which in turn strengthens the technology’s economic impact.

Conclusion

This study used a custom-designed ACP fumigation chamber to assess its economic feasibility in pest control in stored rice in three case-study companies: two drying and storage companies of different sizes and a rice milling company. The authors employed the net present value analysis to assess the economic feasibility for firms and IMPLAN’s input–output model for evaluating broader economic impacts. The authors hypothesized that utilizing the fumigant with reactive gas species would reduce hold times, enabling drying and storage facilities to lower costs and boost profitability. The analysis of rice drying and storage operations showed that profitability is linked to the volume processed and stored, since there is little influence on the price. Despite initial expectations that the ACP fumigation chamber would provide significant cost savings, the investment analysis revealed that operational expenses exceeded revenue for the two drying and storage companies studied. This indicates that solely relying on storage and fumigation fees may not be sufficient for financial viability in this industry. To address this, the authors suggest that future research explore modular or mobile ACP models better suited to the needs and scale of drying and storage facilities.

However, the results were more promising when the ACP fumigation chamber was applied to the milling company. Mills utilize similar fumigation strategies and show that the chamber can indeed lead to a more profitable outcome, yielding positive NPV. By effectively reducing pest-related losses and operational costs, the chamber further enhances profitability. While the ACP fumigation chamber may not be as effective for standalone drying and storage facilities, its integration into milling operations presents a viable and profitable solution, highlighting the importance of considering specific market applications to achieve financial success.

Overall, investment in the new technology would have a significant impact on the U.S. economy. The input–output analysis showed that adoption rates of 10%–75% could yield total economic output ranging from $77 million to over half a billion dollars. This impact would also be felt across multiple sectors and occupations, highlighting the interrelatedness of the agricultural sector. Additional economic gains are expected if the technology is adopted by other types of industries, such as global freight shipping or international markets. Future research should explore scaling the ACP fumigation chamber to accommodate varying sizes of operations, enabling broader and more flexible implementation across industries and regions.

Data availability statement

Data were sourced through interviews with two rice storage companies and one mill located in Texas. Other data were collected from ACP laboratory experiments at Texas A&M University.

Author contribution

Field study research and article development: N.K.B., C.T., J.M.M., D.R., K.Z.S.; Methodology: C.T., N.K.B.; Writing original draft: N.K.B., C.T.; Writing—review and editing: C.T., N.K.B., J.M.M., D.R., K.Z.S.

Funding statement

This research was made possible through the Kunze Rice Fellowship that funded Dr. Kirk-Bradley’s doctoral studies. This work is supported by the NC213: Marketing and Delivery of Quality Grains and BioProcess Coproducts Project No. 7006647, through the Hatch Act fund from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

AI declaration

We declare that artificial intelligence was not used in the generation of this article.