A. Introduction

This study presents a new critical lens on international environmental law (IEL), moving beyond two common narratives. The first narrative portrays IEL through a “crisis” lens.Footnote 1 Critics argue that viewing IEL solely as expressions of state sovereignty leads to exploitative outcomes.Footnote 2 Echoing Koskenniemi’s critiques, this vulnerability renders IEL an “apology” for its shortcomings.Footnote 3 The second narrative adopts an “ambition” lensFootnote 4 and embraces concepts like Earth LawFootnote 5 and Earth Systems Integrity.Footnote 6 It advocates reorienting IEL towards a “planetary perspective” and “geological timescales.”Footnote 7 While crucial for vision-building,Footnote 8 Koskenniemi’s warnings remind us these ambitions risk utopianism. Abstract norms may fuel impractical arguments.Footnote 9 The tendency to view IEL as “lacking organizational and doctrinal unity”Footnote 10 further amplifies problems. Conflicting norms validate crisis claims,Footnote 11 while the limited social anchoring of new paradigms reinforces ambition critiques.Footnote 12 Though these critiques hold value, such views often lack a systemic account of how IEL develops responsiveness to social interests. Instead, we end up with an “inconclusive jumble of case studies” where it seems nothing “adds up.”Footnote 13 Simply put, the literature lacks a “central core,”Footnote 14 particularly a “theory of society” that underpins every environmental law.Footnote 15

Recognizing the limitations of crisis and ambition narratives in IEL, this study offers an alternative account. It embraces both ambition and modestyFootnote 16 to gain independence from accounts that frame IEL solely through these lenses. The study shows modesty by refraining from evaluating whether IEL norms produce morally good or bad outcomes. Its ambition, however, drives it to understand the processes that ensure IEL’s continued coherence as a legal system. Through this inquiry, we aim to better understand how IEL addresses problems raised by crisis and ambition narratives. Current narratives use methods like empirical studiesFootnote 17 or doctrinal analysis.Footnote 18 Yet these approaches depend on the “unsustainable belief” that a sound method can capture reliable facts.Footnote 19 While valuable, these methods provide only partial insights into IEL’s systemic function.Footnote 20 As a way forward, we propose using Niklas Luhmann’s social systems theory.Footnote 21 Luhmann’s approach is valuable because it is not a dedicated method but a “thick” sociological account of the legal system.Footnote 22 We develop this thick account by formulating three hypotheses about IEL norms. First, however, we explain how operative closure theory shapes our methods for evaluating the South China Sea (SCS) context.

Operative closure theory explains how IEL maintains coherence while addressing system problems.Footnote 23 It frames IEL within a legal system, a recursive network of communicationsFootnote 24 that operates according to legal rules.Footnote 25 While this orientation, termed “normative closure,” creates systemic boundaries, it simultaneously enables IEL to remain cognitively open to new information. Three systemic processes—variation, selection, and retention—help explain this dual functionality.Footnote 26 IEL shows its openness by responding to the varying demands of science and politics. This reflects IEL’s performance in securing possibilities like environmental protection and dispute resolution. However, IEL is never fully open, as it relies on selecting normative expectations worth protecting. This relates to law’s function of stabilizing some social expectations at the expense of others.Footnote 27 Together, these stances reveal the paradox of IEL’s operative closure. To retain relevance, IEL must grapple with two questions: Are practices sustainable, and are they legal? Sustainability guides IEL’s cognitive direction, while legality steers its normative compass. This implies that sustainable adaptation hinges upon IEL upholding law’s function of stabilizing expectations.

A sociological method reformulates the problem which IEL functions to address. This means shifting from decision problems to system problems. Decision problems are those faced by scholars and practitioners who directly engage in decision-making. These problems often stem from narrow criticisms of IEL’s alignment with capitalism and state interests.Footnote 28 Conversely, system problems provide a broader view on recurring issues that shape the long-term continuity of IEL. These system problems are not necessarily operational flaws within IEL. Instead, they arise from the complex relationship between science, law, and politics.Footnote 29 Our method constructs this “triangular constellation”Footnote 30 to explain how IEL sustains its operative closure. It links various system problems with IEL processes to show how social context informs decision-making. For example, varying facts from scientists create a contingency problem for IEL. In response, lawyers selectively filter legal expectations to maintain legal confidence. Politicians further require this filtering to uphold state consensus and address trust retention problems.

The context of three key IEL norms applied by the 2016 SCS tribunalFootnote 31 helps conceptualize IEL’s response to these system problems. Section C explores this further, detailing the Philippines’ claims that China breached these norms.Footnote 32 For now, we treat IEL norms as social factsFootnote 33 and use the trinity of systemic processes to steer our hypotheses formulations as follows. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) normsFootnote 34 address the system problem of contingency. While the SCS has rich biodiversity,Footnote 35 environmental problems do not immediately affect IEL. Scientists must verify state claims, often leading to variant views. Due diligence norms to protect the marine environmentFootnote 36 address the system problem of confidence. These norms do not impose an absolute duty to avoid harm, but set expectations for best practices, even when outcomes are disappointing. This means that lawyers and judges may select or disregard claims lacking a legal basis to maintain confidence in the legal system. Cooperation normsFootnote 37 retain scientific and political balance by addressing the system problem of trust.

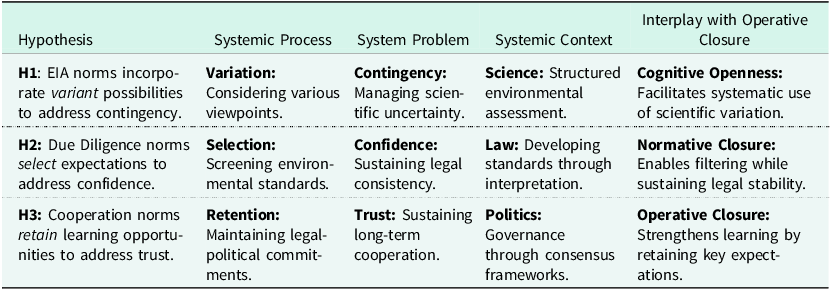

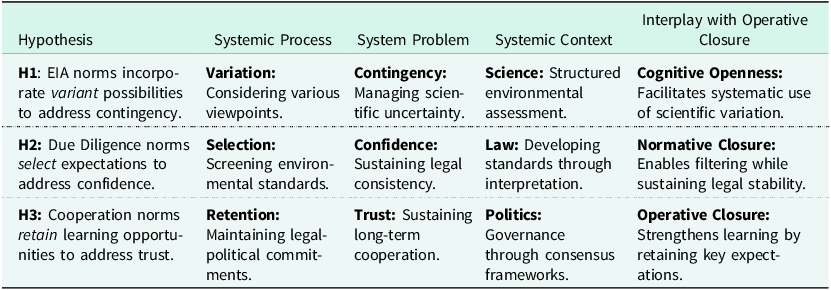

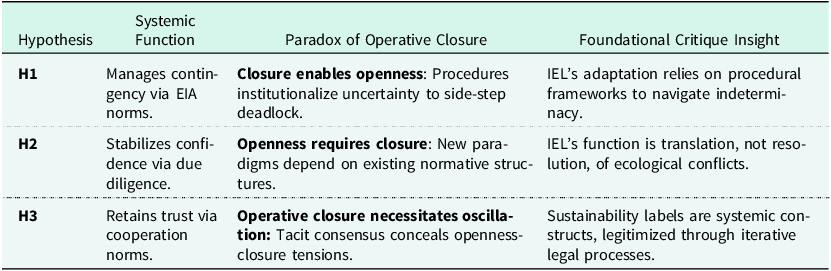

The SCS offers a useful context to highlight the tensions between scientific and political priorities. Science seeks to minimize risks, while politics focuses on maintaining power.Footnote 38 For example, in the SCS tribunal, the Philippines raised environmental disputes as part of its legal claims. While the tribunal affirmed IEL norms, its ruling was unenforced because China claimed a lack of jurisdiction.Footnote 39 China claims sovereignty within the “nine-dash line,” a region also claimed by Brunei, Malaysia, and Vietnam.Footnote 40 This leads us to ask: What is IEL’s function in environmental disputes involving disputed territorial claims? Neither the crisis nor ambition perspective provides a sufficient answer. However, the theory of operative closure—applied at a high level of abstraction and generality—provides a conceptual solution. It allows us to compare the elements of each hypothesis and explain how they relate to IEL’s operative closure, as demonstrated in the table below.

Table 1. Interplay Between Hypotheses and IEL’s Operative Closure

Our formulation of hypotheses is unconventional. The purpose of mapping IEL’s operative closure through these hypotheses is not to test whether theory reflects practice. Each hypothesis has biases, and none can fully capture the anarchic nature of IEL,Footnote 41 which a crisis lens typically presents. Instead, we use them as a question generating conceptual tool to set a new standard of critique.Footnote 42 This standard offers an “immanent” critique, arising from observing how these hypotheses interconnect. While we analyze each separately for clarity, they must be viewed as an interconnected system. Only then can we understand how IEL’s operative closure functions at both macro and micro levels.

Macro insights arise from mapping how IEL conserves the specialization of legal communications. For example, hypothesis 1 (H1) proposes that EIA norms enable IEL to manage contingencies by incorporating variant viewpoints. Yet, due diligence norms select this adaptability to ensure legal certainty (hypothesis 2 (H2)). Furthermore, cooperation norms coordinate between “knowledge and ignorance”Footnote 43 to address trust retention problems (hypothesis 3 (H3)). Together, these systemic processes reveal IEL’s dual capacity. They show how IEL adapts to changing events while sustaining law’s role of stabilizing societal expectations.

Micro insights arise from mapping how system problems shape IEL’s filtering of legal communications. For example, (H3) demonstrates that unilateral state actions—rather than cooperative approaches—erode trust. This trust deficit directly impairs EIA processes (H1), as decisions become linked to unsustainable practices. Furthermore, a reduced capacity to manage unexpected events can undermine confidence in due diligence norms (H2). These interactions expose how political agendas and scientific uncertainties distort legal outcome predictions. Crucially, they reveal IEL-specific system problems that legal formalism typically masks. The question then is: Under what conditions can IEL manage these system problems while upholding IEL’s operative closure?

The following structure guides this study. Section B presents an alternative account of IEL, moving beyond crisis and ambition views. Section C reviews the SCS tribunal for context. Sections D and E formulate three hypotheses about the function of IEL norms. Section F then summarizes by reframing IEL through the critical lens of operative closure.

B. Beyond Crisis and Ambition

Viewing IEL through the lens of crisis or ambition often leads to both conceptual and practical challenges. A crisis lens apologizes for the inability of the doctrinal method to resolve disputes. This apology stems from the inherent limitations of the doctrinal method in addressing broader issues. For instance, numerous doctrinal accounts center on China’s alleged breach of specific IEL norms, as ruled by the SCS tribunal.Footnote 44 Yet this incident-centric approach yields limited understanding of three broader, intersecting problems challenging IEL. These problems include information, governance, and legitimacy.Footnote 45 Limited marine science research creates a substantial knowledge gap. This gap hinders establishing measurable conservation goals for regional seas conventions. Uncertain enforcement follows,Footnote 46 raising questions about IEL’s effectiveness in preventing exploitation.Footnote 47 Proceduralization, with its emphasis on rules on how to proceed, offers a potential answer to these overlapping problems.Footnote 48 It underscores rules about time and sequence, in addition to strategy and learning, from social developments. However, the day-to-day legal processes stemming from proceduralization often vanish from a doctrinal perspective. This has led to an underappreciation of IEL’s unique function of stabilizing normative expectations.Footnote 49

Conversely, an ambition lens that embraces non-anthropocentric ideals counters the utopianism critique. These ambitions, which aspire to align IEL with a “planetary perspective,”Footnote 50 often arise as reactions to moral outrages. Critics argue IEL exacerbates climate injustice.Footnote 51 In response, supporters offer compelling alternatives. They propose, for example, that we view oceans as living beings rather than mere objects.Footnote 52 The ultimate goal is a just process that democratizes access to oceanic knowledge and identities.Footnote 53 These vision-building values are undoubtedly valuable as they inspire innovation. Yet, the more IEL embraces these values, the less predictable and normatively robust the law becomes.Footnote 54 This does not diminish valuing efforts to reform IEL. After all, problems require solutions and decisive action. Before acting, however, we must consider the complexities of legal change, which are often overlooked.

The confusion about IEL’s function arises partly from crisis and ambition lenses, suggesting legal change emerges through events or paradigm shifts. However, legal systems are not changed solely by such phenomena. For change to occur, a multitude of actors must simultaneously modify their beliefs and actions. This is challenging and unlikely to happen by chance.Footnote 55 Legal change is more likely to relate to the complexity of social systems.Footnote 56 Accordingly, legal systems may respond to short-term social upheavals, such as war or economic crisis. Legal systems may also respond to long-term processes of social transformation. However, how legal systems respond to such events is determined by law’s operative closure. In essence, this refers to how the law confirms social expectations while also upholding law’s function of stabilizing expectations. The law accomplishes this by connecting current expectations to how future laws are likely to be applied.Footnote 57 Without this connection, an entirely unpredictable future would overwhelm decision-makers with complexity. Some level of predictability and legitimacy are required, which is the law’s role.

To reiterate, the law has a unique role: it stabilizes expectations and maintains them even in the face of disappointment.Footnote 58 No other system, such as science or finance, can fulfill this function. Yet, this crucial aspect is often overlooked by scholars, who conflate law’s function with its performance in achieving regulatory ideals. For instance, they may equate dispute resolution and environmental protection with the function of IEL.Footnote 59 Although these views are valid, they present a misleading picture. Firstly, regulatory ideals like environmental protection create the impression that IEL directly resolves issues. In practice, IEL merely equips states with the tools to handle them. Secondly, regulatory ideals are not exclusive to the legal domain. Diplomatic negotiations, which happen outside of formal legal channels, can also resolve disputes. Similarly, financial incentives, such as subsidies for sustainable fishing, can contribute to environmental protection.Footnote 60 In short, conflating IEL’s function with non-specific legal mechanisms obscures its unique purpose.

The concept of operative closure offers a conceptual remedy. Instead of mixing up regulatory ideals by asking about IEL’s specific function, the concept shifts the focus. It explores the conditions IEL needs to meet to fulfill law’s general function of stabilizing expectations.Footnote 61 IEL can facilitate regulatory ideals, such as dispute resolution and environmental protection. But how can IEL create a semblance of legal order when interests conflict? To answer this question, we must elevate our level of abstraction to observe how system problems shape the continuity of IEL’s operative closure. Only by conceptualizing this phenomenon can we understand how IEL develops responsiveness to social interests. This is why Section D connects theory, method, and social context to reconstruct IEL’s operative closure. However, first, UNCLOS and the SCS tribunal ruling are reviewed to frame our current study.

C. UNCLOS and the South China Sea Dispute

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) offers a legal framework for governing the world’s seas and oceans. Often termed the “Constitution for the Oceans,”Footnote 62 UNCLOS covers a wide spectrum of issues. These encompass marine environment protection, maritime boundaries, navigation, fisheries, scientific development, and dispute settlement. Relevant to IEL are three UNCLOS norms which form the building blocks within the broader IEL framework. They include the obligation to conduct an EIA,Footnote 63 the due diligence to protect the marine environment,Footnote 64 and the duty to cooperate.Footnote 65 On the one hand, EIA norms facilitate the gathering and analysis of information about the effects of proposed projects.Footnote 66 In line with the precautionary approach,Footnote 67 these norms serve as crucial tools for environmental governance. Due diligence norms, on the other hand, are substantive standards that require states to follow best practices for protecting the marine environment.Footnote 68 To achieve this, states must implement the most widely accepted “appropriate rules” and enforcement methods.Footnote 69 Cooperation norms focus on a different area. These are procedural rules that require states to cooperate regionally to protect the marine environment.Footnote 70 This cooperation includes developing international environmental agreements and establishing mechanisms for dispute settlement.

The 2016 SCS tribunal—Philippines vs. China—“is a leading case in a new generation of environmental disputes” that occur in “maritime areas.”Footnote 71 The environmental dispute is one of several legal claims the Philippines made against China. These claims also included the aggravation of the dispute during the arbitration process, the legal status of maritime features, and the source of maritime rights in the SCS.Footnote 72 The roots of these claims are in a disputed territory where China lays claim to historical and sovereign rights within the “nine-dash line.” However, three other Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) states—Brunei, Malaysia, and Vietnam—also have direct claims to the area.Footnote 73 This is contentious because the area holds abundant natural resources for both fisheries and oil extraction.Footnote 74 Additionally, the area ranks among the world’s most significant biodiversity reservoir regions.Footnote 75

At the tribunal, the Philippines alleged China breached UNCLOS norms and their sovereignty. The Philippines presented fifteen submissions to the tribunal. Submissions eleven and twelve held relevance to IEL. The eleventh submission claimed that China infringed on marine environmental protection obligations. It maintained that China tolerated harmful fishing practices undertaken by Chinese fishing vessels. This encompassed the active support of giant clam harvesting in coral reef locations such as the Huang Yan Islands, or Scarborough Shoal. This claim led to the crushing and deterioration of the surrounding coral reef structures.Footnote 76 The twelfth submission relates to China’s construction activities on reefs in the Nansha, or Spratly, islands. It maintained that constructing artificial islands, installations, and structures violated China’s due diligence obligations. Specifically, China violated its UNCLOS due diligence duty to protect and preserve the marine environment.Footnote 77

Three key points arise from the SCS tribunal’s decision. First, the SCS tribunal upheld due diligence norms to protect the marine environment through the eleventh submission. It found that Chinese fishing vessels had significantly harvested endangered species, and these activities were attributable to the Chinese government.Footnote 78 Thus, the tribunal declared China breached its obligations to protect the marine environment.Footnote 79 Second, the SCS tribunal upheld EIA and cooperation norms through the twelfth submission. It found that China’s construction of artificial islands at the above seven reefs caused “severe, irreparable harm to the coral reef system.”Footnote 80 It also found that China failed to cooperate with SCS neighbors, specifically by not communicating an EIA of the potential effects.Footnote 81 Third, despite the tribunal’s affirmation of IEL norms, China did not recognize its findings. China adopted a policy of non-compliance towards the tribunal, asserting it had no jurisdiction over the case.Footnote 82 Consequently, the tribunal could not propose remedies for the Philippines due to the unenforced ruling.Footnote 83

This study takes a different approach than addressing the immediate concerns of IEL practitioners. We do not explore the reasons behind non-compliance with IEL norms, nor do we prescribe the ideal content of these norms. Instead, we aim to broaden our perspective and observe IEL through the critical lens of operative closure. This lens seeks to develop a “theoretically consistent and heuristically productive” account of IEL,Footnote 84 as explored next.

D. A New Critical Lens: Three Hypotheses

To reconstruct IEL’s operative closure and introduce a new critical lens, we propose three hypotheses. These hypotheses encompass the “tightly” interwoven components of theory, method, and the SCS context.Footnote 85 The theory of operative closure offers a conceptual map for observing IEL’s systemic processes. This theory steers the method of constructing the variant system problems that IEL addresses. The method then selects sociological issues to generate questions about IEL’s function. The context of three key IEL norms, applied by the SCS tribunal, ensures the method retains relevance to legal practice.

Theoretically, we draw on the concept of operative closure to present a new transdisciplinary paradigm. This paradigm aids fields such as science, law, and politics understand the processes IEL needs to continue functioning as a legal system. To bridge gaps, we translate diverse ideas into three processes: variation, selection, and retention. Our approach offers three distinct advantages. (1) A theory of operative closure segments IEL’s processes for conceptual purposes but keeps them related. (2) A relational perspective provides a macro-level map of how IEL addresses problems while sustaining system coherence. It shows that IEL’s processing of variant facts depends on how IEL selects and retains expectations worth protecting. (3) Reconstructing IEL’s processes highlights how IEL differentiates itself from fields such as politics. This approach helps illustrate IEL’s unique role in stabilizing expectations rather than reducing it to a political tool.

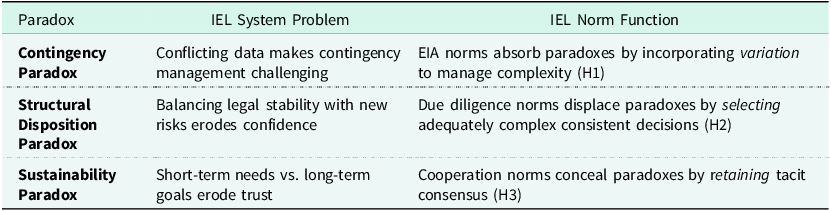

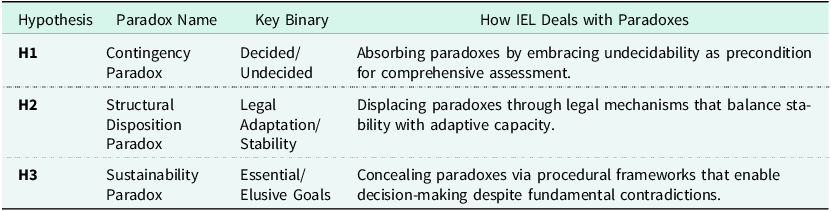

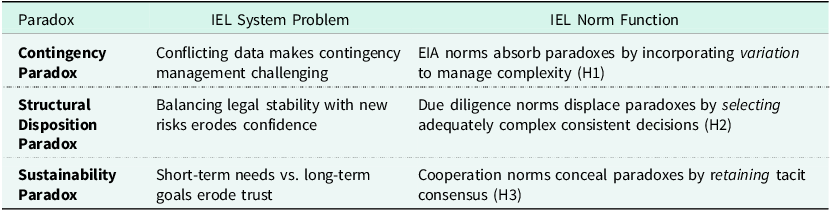

Methodologically, we use a sociological approach instead of an essentialist one. Essentialism typically uses a dedicated method, such as the doctrinal method of applying legal norms to facts to solve problems. This applied approach focuses on upholding IEL norms and prescribing their ideal forms. Conversely, our sociological method treats IEL norms as social facts to analyze their function.Footnote 86 Here, function means the underlying paradox linked to the system problem we hypothesize these norms address. H1 proposes that disagreements among scientists about variant truths reflect the contingency paradox. This leads to a system problem of contingency management, which EIA norms address. H2 proposes that selecting expectations worth protecting highlights the structural disposition paradox. This paradox stems from the system problem of confidence maintenance, addressed by due diligence norms. H3 suggests that disagreements among politicians on development policies demonstrate the sustainability paradox. This results in a system problem of trust retention, addressed by cooperation norms. By forming these hypotheses, we gain new insights into how interconnected opposing viewpoints shape paradoxes. This, in turn, stimulates reflection on how paradoxes shape the system problems that IEL norms function to address.

Contextually, our hypotheses aim not to verify alignment with SCS realities. Any hypothesis has prejudices, especially when it compels social complexity to fit its dimensions. Instead, our hypotheses leverage the SCS context to reconstruct how IEL functions operatively closed. Here, we adopt an exploratory approach to empirical material. This involves shifting from high-profile jurisprudence to the low-profile everyday aspects of decision-making. We reason that society experiences IEL norms, primarily not through judicial decisions. International courts seldom settle environmental disputes, and those adjudicated are often insubstantial.Footnote 87 Instead, we propose that society experiences IEL norms in two main ways: first, through how paradoxes appear in everyday decisions, which influence the form of IEL system problems; and second, through how IEL norms address these paradoxes that underlie IEL system problems. While paradoxes are generally unsolvable,Footnote 88 IEL norms can mitigate them in three ways, as outlined in the table below.

Table 2. The Role of Paradoxes in IEL and the Function of IEL Norms

Despite presenting each hypothesis in separation, IEL’s operative closure intertwines them. The structural disposition of due diligence norms creates the conditions for EIA norms to absorb the contingency paradox. This then empowers cooperation norms to pacify conflicts stemming from the sustainability paradox. We explore this next by combining our three paradoxes—hypotheses—to stimulate reflection on IEL’s operative closure.

I. Hypothesis 1: EIA Norms Function to Address the System Problem of Contingency

Contingency articulates the system problem of undecidability.Footnote 89 This arises from the uncertainty inherent in any decision, especially when considering ecological risks. EIAs for offshore oil platforms in the SCS exemplify this uncertainty. Non-linear environmental feedback loops create knowledge gaps that hinder risk analysis.Footnote 90 To address this, EIA norms differentiate between formal procedures and informal “old boy” networks.Footnote 91 The latter dominate assessments through opaque negotiations, yet their secrecy creates a paradox. While exclusivity maintains their power, it also traps them in inflexible patterns. For instance, restricted data access sustains dominance but prevents adaptation to new risks. In contrast, formal EIA norms demand a “dialogical process”Footnote 92 about EIA methods, making them easier to identify and, therefore, change. This is key because even states not ratifying UNCLOS must uphold certain standards, like publishing EIA findings. States must also adapt their practices to comply with legal procedures mandating consultation on EIA processes for proposed projects with considerable environmental impacts.Footnote 93

Not all risks receive equal protection under EIA norms. For instance, consider how EIA norms process risks associated with giant clam harvesting. The intrinsic beauty of giant clams is not the subject of an EIA report. Instead, EIA norms adhere to instruments like the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).Footnote 94 This means species listed in CITES Appendix 1 may receive greater protection than those in Appendix 3. Footnote 95 However, categorizing endangered species is a double-edged sword. It stabilizes state duties, as shown by the SCS tribunal’s decision to apply CITES Appendix 2 strict rules to giant clams.Footnote 96 Yet, it also creates problems, such as disputes over classifying giant clams under CITES Appendix 1, which prohibits harvesting.Footnote 97

EIA norms, involving observing and assessing environmental effects,Footnote 98 present a paradoxical form of relief. EIA decisions gain perceived comprehensiveness precisely because their foundational criteria remain in principle undecidable. The UN High Seas TreatyFootnote 99 exemplifies this contingency paradox. While ratification is voluntary, states cannot ignore the treaty’s effects—it reshapes legal expectations. This dynamic pressure compels states to refine EIAs for activities such as island-building in the SCS. First, the treaty amplifies contingency by specifying stricter substantive requirements. Assessments must consider all impacts surpassing “minor or transitory effect on the marine environment,”Footnote 100 including cumulative stresses and climate-related damage.Footnote 101 Second, the treaty necessitates a “dialogical process”Footnote 102 to absorb contingency. This fosters collective learning about both existing knowledge and unknown knowledge. Continuous monitoring protocols and publication of (non)-findingsFootnote 103 for “poorly understood” activitiesFootnote 104 illustrate this function. Indeed, exhibiting this property of undecidability is essential. Only by acknowledging the limitations of knowledge can an EIA appear more comprehensive.

Conversely, omitting dialogical processes in EIAs creates systemic risks. China may strategically comply with EIA requirements to build environmental credibility. Officials may assert that island-building projects followed scientific protocols.Footnote 105 Yet this reduces EIA norms to checkbox exercises, neglecting their contingency paradox. Comprehensive EIAs emerge through communicative engagement with alternative possibilities. This includes evaluating competing scientific models alongside relevant “traditional knowledge” and justifying methodological choices.Footnote 106 Challenges emerge when EIAs frame compliance unilaterally. Such narratives find acceptance only within social environments that tolerate restricted communicative frames. However, when ecological anxiety erupts, neither visible controls nor representative performances suffice.Footnote 107 Anxiety perpetuates itself as a self-reinforcing medium,Footnote 108 escalating when third-party research contradicts official findings.Footnote 109 Linking ecological harm to state decisions further reveals ambiguities in due diligence norms.Footnote 110 Because these norms allow states flexibility in determining EIA content, loopholes emerge. Resulting indeterminacy fuels interstate disputes over compliance expectations.

Scientific uncertainties further complicate the challenge of managing expectations. Consider an EIA of island-reclamation activities on coral reefs. While metrics like the Coral Health IndexFootnote 111 can quantify ecological harm, EIAs also amplify uncertainties. This reflects the probabilistic nature of science.Footnote 112 An EIA may find that coral reef restoration could take decades or even centuries.Footnote 113 For instance, an EIA might project ecosystem recovery spanning decades to centuries. However, emphasizing probable outcomes can paradoxically erode an EIA’s perceived validity—a contingency paradox. Decision-makers desire clear conclusions despite facing multiple probabilities. Consequently, uncertain EIAs often seem insufficiently decisive within legal-political frameworks. This perception enables states to privilege expert opinions supporting their predetermined agendas. The precautionary principle offers a potential corrective mechanism here.

The precautionary principle affirms that uncertainties cannot justify disregarding potential risks.Footnote 114 Thus, if the impacts of island reclamation on coral reefs are uncertain, states cannot use this uncertainty as a reason to forego protective measures. Proactive steps like consultations or negotiations are required for safeguarding reefs.Footnote 115 However, such requirements can lead to unintended deviation and disorder. States may notify others of marine scientific research findings,Footnote 116 yet recipients can easily consent or refuse the offered content.Footnote 117 States may consult expertsFootnote 118 on an EIA’s quantitative findings, yet these calculations face obstacles as they are known to be malleable.Footnote 119 States may participate in negotiationsFootnote 120 to exchange data on marine pollution,Footnote 121 yet, in the absence of trust, this rarely resolves uncertainties and can become a delaying tactic. Cumulatively, these interactions exacerbate the contingency paradox by overloading institutional decision-making with contested information. The question then arises: How can decision-makers effectively manage the contingency paradox of EIA norms?

In this lies the potential of the legal technique of due diligence norms. This legal technique transforms the contingency paradox into a less harmful, more acceptable contradiction.Footnote 122

II. Hypothesis 2: Due Diligence Norms Function to Address the System Problem of Confidence

Confidence articulates the system problem of managing situations marked by contingency and danger. Consider the Manila Trench’s seismic volatility, where an unforeseen earthquake could generate a tsunami with cascading impacts across the SCS. Even if such an event overwhelms coastal states, due diligence norms cannot permit a collapse of order.Footnote 123 Instead, due diligence norms must relieve liabilities to prevent overwhelming litigation. This applies especially when states could not foresee such dangers or where a clear link between decisions and inflicted damage is absent. The No Significant Harm Principle (NSH) provides a framework for addressing these challenges. While not an explicit legal goal, the principle appears as a due diligence obligation, compelling actors to protect and preserve the marine environment.Footnote 124 This substantive “negative duty” often takes the form of if-then conditional formulas. These formulas link specific circumstances to legal consequences, ensuring systematic accountability. If state X breaches duties not to degrade the marine environment, then disappointment is a likely outcome for the involved parties.

Crucially, law’s normative symbolismFootnote 125 stems from the possibility of disappointment rather than mere compliance. Consider the Philippines’ claim that several Chinese vessels harvested endangered species in the SCS.Footnote 126 China views the SCS tribunal’s ruling as disappointing. China’s non-recognitionFootnote 127 of the tribunal’s ruling that China breached due diligence norms exemplifies this.Footnote 128 From a legal system standpoint, this breach clarifies due diligence norms. It sets an expectation that due diligence norms will treat breaches as such, regardless of disappointment. A state that permits its vessels to harvest endangered species, even in territorial seas,Footnote 129 breaches due diligence norms.Footnote 130 The violator may then face explicit criticism, even legal repercussions, for the alleged breach. From the viewpoint of other nations, this breach necessitates others to adjust their expectations. Owing to due diligence norms, ASEAN states can expect others to prevent their vessels from harvesting endangered species. China can also expect disappointment from ASEAN states if they tolerate such practices. Indeed, this potential for disappointment, symbolized by due diligence norms, is the driving force behind IEL. IEL compels states to learn and adapt, even if they are hesitant to accept the authority of international courts such as the SCS tribunal judgment.Footnote 131

Nevertheless, due diligence conditional formulas have inherent structural limitations. Their input-oriented nature prevents them from undermining systemic integration rules.Footnote 132 Thus, due diligence norms can only maintain environmental protection as long as they do not conflict with other existing rules.Footnote 133 Simply put, due diligence norms are enforceable only if other regulations exist undisrupted. Examples include freedom of navigation and the London Protocol. The former grants shipping rights to international users,Footnote 134 while the latter permits the disposal of “acceptable” waste.Footnote 135 As a result, commercial interests often take priority, as this focus is crucial for maintaining the support of actors involved in IEL. However, this does not mean that commercial interests will completely dominate legal policies. A key question is the extent to which IEL can purge these biases towards commercial interests.

Importantly, purpose-oriented due diligence norms distinguish means from ends to mitigate biases. Their focus on outcomes fosters purpose-oriented “sensibilities,”Footnote 136 as shown by the formula: to decide Y to achieve goal X. In the context of due diligence norms’ positive duty, this means taking active steps to protect and preserve the marine environment. This approach compels decision-makers to consider legal issues from a universal standpoint.Footnote 137 It creates an expectation that states will protect or improve the marine environment’s current condition. While due diligence norms do not specify exact actions, they do mandate maximum effort to prevent environmental harm. This includes adopting best-practice procedures, such as establishing formal cooperative scientific organizations.Footnote 138 These initiatives, however, might not increase certainty or reliability. Instead, they frequently spur increased demands for information. Excessive information, fueled by “media hype,”Footnote 139 can obscure crucial details and hinder decision-making. This is why IEL always pairs “specific sensibilities” alongside “specific stabilities.”Footnote 140 Ultimately, IEL’s ability to respond to social interests depends on its own rules and its normative closure.

To gain this systemic orientation and uphold law’s normative symbolism,Footnote 141 due diligence norms reduce complexities. They achieve this not by determining the cause of harm, but by ensuring adequately complex consistent decision-making.Footnote 142 This confidence-building mechanism protects IEL from unanswerable causality questions. It renders previously irresolvable issues manageable at least within law’s realm. Examples include whether states escalated disputes by breaching good-faith obligations,Footnote 143 or whether EIAs were communicated with relevant parties.Footnote 144 Framing technical legal questions as standardized due diligence norms offers a significant advantage: It enables the law to show that Party B’s position conforms to these norms, whereas Party A’s does not. Therefore, failure to disclose EIA results would contravene due diligence norms. This is especially true if island-reclamation activities may plausibly cause serious harm.Footnote 145 However, this also means that, unless explicitly forbidden, other actions are permitted. For example, a state can utilize sovereign rights to exploit its natural resources within reason.Footnote 146 This is why states can speak of “effective compliance” and the best practices of sustainable fishery resource exploitation.Footnote 147

Admittedly, the mere adherence to “good” practices and legal regulations does not necessarily mean that due diligence norms are just. In fact, the more states rely on “effective compliance” to justify their actions, the more questionable their legitimacy appears.Footnote 148 This is especially true when states contest due diligence norm compliance. China’s non-acceptance of the SCS tribunal rulingFootnote 149 and its counter-arguments of “best possible efforts”Footnote 150 serves as a prime example. However, conflicting expectations do not necessarily lead to chaos. Where confidence is lacking, cooperation norms can offer relief by addressing the system problem of trust.

III. Hypothesis 3: Cooperation Norms Function to Address the System Problem of Trust

Trust is key to risk management, especially for SCS states navigating the paradox of sustainable development. Sustainable development goals anchor IELFootnote 151 by facilitating knowledge exchange.Footnote 152 This exchange helps states predict behavior and coordinate actionsFootnote 153 like SCS fisheries management.Footnote 154 However, structural contradictions within these goals can hinder their implementation. Decisions tied to unsustainable practices may erode trust and impede planning. States may subsidize fishing fleets to establish a presence in disputed waters. Sovereignty disputes further weaken efforts to enforce effective fisheries management rules.Footnote 155 When one state exceeds fishing quotas in shared waters, others may abandon conservation agreements. This retaliatory cycle erodes trust, dismantling collaborative systems designed to protect ecosystems. Breaking this pattern necessitates entrusting decision-making to competent institutions. Cooperation norms are crucial in this process.

Cooperation norms facilitate trust by motivating decision-making. They cultivate this by fostering an “economy of consensus”Footnote 156 on general problems and rules. Consider the general problem of ecological adaptation and the general rule that “all states involve in cooperation.”Footnote 157 Everyone agrees because abstract values allow recipients to interpret general commitments to their priorities. Undeniably, such style of declaratory politics leaves much to be desired. However, what is gained from sounding out the capacity for consensusFootnote 158 is that it reinforces “mutual commitments”Footnote 159 —a prerequisite for trust. It creates expectations that non-cooperation in sea-resource conservation is not one’s own mistake, but the fault of others.Footnote 160 These mutual commitments further imply that cooperation is necessary even when disagreements arise. Both sides must acknowledge the need to decide on more substantive issues. However, what happens when trust is lacking prior to cooperation?

Specific codes of conduct can offer relief in this situation. For example, Marine Protected Area (MPA) policies prevent species extinction using purpose-oriented formulas.Footnote 161 These include rules like catch limits, seasonal bans, and restricted fishing zones to meet goals. Crucially, the policy facilitates trust by emphasizing the positive value of achieving goals over their costs. States might promote MPAs within high seas of the SCS, even if it means adjusting sovereign territorial claims.Footnote 162 States might also implement export permits to protect endangered species over the demands of their domestic markets.Footnote 163 However, the use of MPAs for environmental protection is not without complexities. Establishing protected zones requires drawing a boundary, highlighting the protection of only specific environments.Footnote 164 Protection requires observing and representing marine environments through simplified biodiversity metrics and models.Footnote 165 Simplification mediates the processing of different zone uses—for example, no-take zones versus exclusive economic zones.Footnote 166 While accepting these risks is ultimately a decision for states, we can see how legal procedures contribute to system stability.

Consider the functionality of legal procedures such as notification, consultation, and negotiations. NotificationsFootnote 167 function to address communication problems. They give states the opportunity to accept or reject content presented, which is essential for states to make informed decisions. ConsultationsFootnote 168 function to address governance problems. They aid in making disagreements more manageable, guided by the scientific standards of risk minimization. NegotiationsFootnote 169 function to address legitimacy problems. They allow a “general readiness to accept, within certain tolerance limits, decisions that are still without content.”Footnote 170 But what happens if human error causes something unexpected to occur? Under these conditions, states may not necessarily face a fundamental crisis of direction. On the contrary, IEL norms offer numerous directives that minimize the potential for disorientation. This includes the synergy between directives concerning reputation, governance, and legitimacy. EIA norms create conditions that allow institutions to promote a positive ecological reputation. Due diligence norms provide a framework for confirming these social expectations. Cooperation norms mitigate conflicting social expectations by emphasizing “procedural legitimacy.”Footnote 171

First, EIA norms influence institutional reputation. As EIAs become more well-known and understood, their impact on public opinion and decision-making grows. States that neglect this factor risk a reputation loss. Maintaining credibility requires diligent review of authorized activities and responsive action addressing impact findings.Footnote 172 However, EIA norms do not guarantee complete scientific objectivity. States retain flexibility in determining EIA content.Footnote 173 Nevertheless, EIA norms can enhance institutional reputations by ensuring certain expectations are met. They guarantee the expectation that all decisions with potential environmental impacts undergo comprehensive EIAs.Footnote 174 They also ensure the expectation that EIAs consider the perspectives of affected states.Footnote 175 In essence, EIA norms guarantee the expectation of a dialogical process regarding the scope and methods of proposed EIAs.Footnote 176

Second, due diligence norms establish a framework for future action. This framework emerges from two types of formulas working in tandem: conditional and purpose-oriented. Conditional formulas rely on substantive norms and create a structure of conditions and consequences. If a state breaches its due diligence obligations toward marine environments, it faces legal consequences.Footnote 177 These might include environmental remediation or damage compensation. In this way, conditional formulas restrict options by defining forbidden behaviors. Purpose-oriented formulas ensure due diligence norms remain relevant as circumstances change. These formulas operate through procedural norms and focus on the relationship between means and ends. They require states to take proactive measures to protect marine environments, which fosters collective learning.Footnote 178 States must consider best practicesFootnote 179 when selecting their approaches as situations evolve.Footnote 180 Paradoxically, this also means that what is not forbidden is allowed, such as a state’s right to exploit its natural resources reasonably.Footnote 181

Third, cooperation norms retain trust in decision-making by facilitating confidence in institutions. This trust stems not chiefly from the internal workings of institutions but from how these norms utilize visible controls.Footnote 182 Visible controls compensate for the law’s inability to determine substantive outcomes. They achieve this by setting clear procedures for reaching specific results. The obligation for states to regulate relevant entities under their jurisdiction exemplifies this approach. When a UNCLOS signatory fails to control its entities and pollution results, other parties can invoke liability.Footnote 183 This is possible because states have recourse to dispute settlement procedures provided by UNCLOS,Footnote 184 as shown by the SCS tribunal.Footnote 185

Visible controls also address development divides by promoting standards for capacity-building and technology transfer.Footnote 186 These standards equalize access to financial and technological systems. They serve as legal mechanisms enabling developing states to narrow gaps with developed nations. To maintain political acceptability, cooperation norms acknowledge a critical constraint. Cooperative bodies cannot impose standards like technology transfer on developed states. Such imposition would undermine intellectual property rights and subsequent inter-state trust. Therefore, cooperation norms require implementation within state “capabilities” on “mutually agreed terms.”Footnote 187 This approach defines how cooperative bodies facilitate inter-state trust relations.Footnote 188 These bodies do not directly solve problems but empower states to tackle them. They establish decision-making processes that advance inquiry and create new premises amid disagreements. By design, these institutions minimize explicit power strugglesFootnote 189 while prioritizing open deliberation.

Conversely, cooperative norms can construct an impression of legitimacy by empowering representative performances. China’s policies on marine-catch quotas, fuel subsidies, and fisheries trading illustrate such empowerment.Footnote 190 These pledges often use representative performances to show progress in ecological conservation. They do so by demonstrating how actions have narrowed the gap between current and desired ecological conditions. The extension of China’s fishing moratorium and installation of surveillance equipment post-2016 exemplifies such a demonstration.Footnote 191 However, these performances may not be ideal for assessing risk. Political power games and scientific complexities can disrupt even the most well-designed plans. Despite this, representative performances can still create an impression of progress. They can uphold the legitimacy of policy goals, justify actions, and project an image of mutually-beneficial cooperation. Against the prospect of absolute uncertainty,Footnote 192 this dynamic has value: It avoids decision paralysis. Constant focus on unpredictability could otherwise hinder practical governance.

E. Hypotheses as Tools for Norm Reflection

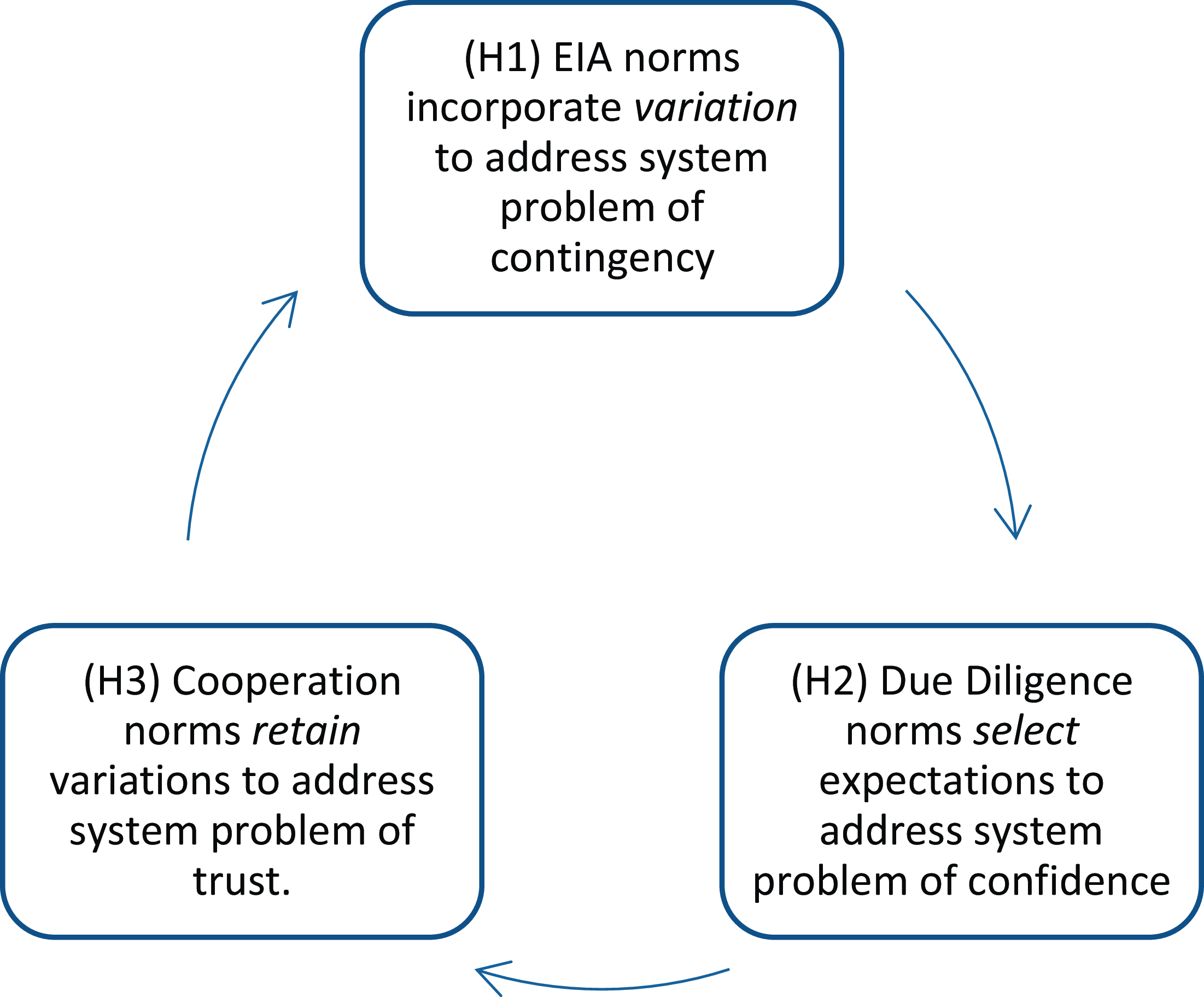

To reconstruct IEL’s operative closure, we developed three hypotheses. Figure 1 presents their cyclical relationship within IEL’s operative closure. It demonstrates how each hypothesis addresses a specific system problem: contingency (H1), confidence (H2), and trust (H3). Each connects distinct norms to specific processes: variation, selection, and retention, respectively.

Figure 1. IEL’s operative closure and the key elements linking each hypothesis (H)

Unlike conventional methods, we suggest a different approach to formulating hypotheses. Rather than testing them against SCS realities, we focus on connecting theory, method, and context to shed new insights in two key ways.

First, the hypotheses stimulate reflection on how IEL addresses problems while sustaining system coherency. This differs from a crisis narrative that focuses on criticizing IEL’s shortcomings. While these criticisms are valid, they often lack a “central core,”Footnote 193 a theory of society that underlies every environmental law.Footnote 194 As a result, the critique often becomes a reactionary response to problems,Footnote 195 rather than a theoretical analysis of how to best frame the problem. In contrast, the hypotheses offer a macro, transdisciplinary map that places IEL’s operations on the “same flat playing field”Footnote 196 as other systems. This universal framing of problems is possible because all social systems function as operatively closed. They operate by being normatively closed to “why” questions but cognitively open to “how” questions.Footnote 197 IEL does not question the reason for using legal inquiries, just as science does not question the use of scientific inquiries. Constantly questioning these fundamental rationalities would lead to system disintegration. Instead, each system focuses on how to improve its approach to problems. Ultimately, operative closure shows that normative closure is crucial for any system to be cognitively open.

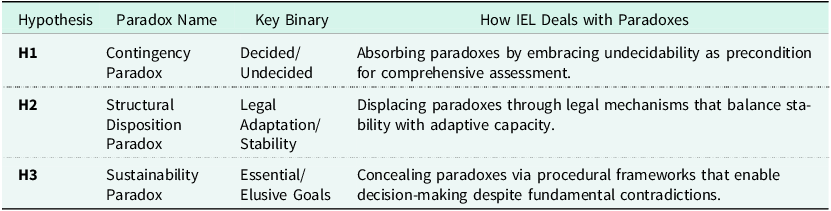

Second, the hypotheses stimulate reflection on the system problems that IEL norms address. This contrasts with an ambition lens, often criticized for utopianism. An ambition lens typically includes non-anthropocentric ideals, like viewing ocean vitality for all.Footnote 198 However, because it focuses on aspirations, an ambition lens often overlooks how system problems inform IEL. In contrast, our hypotheses help explain why the core system problem IEL addresses is the stabilization of expectations.Footnote 199 Stabilization does not depend chiefly on the logical consistency of legal doctrine. Instead, stabilization can only be understood laterally, by observing how paradoxes manifest in everyday decisions. This involves unfolding the form in which IEL norms absorb, displace, and conceal three paradoxes that underpin IEL system problems.

I. H1: The Contingency Paradox of Environmental Impact Assessment Norms

H1 provides insight into how EIA norms absorb the contingency paradox. Unlike precautionary risk management methods,Footnote 200 H1 refrains from reacting to facts to minimize risk. Instead, H1 explores the schemes in which EIA norms recognize facts by unmasking a contingency paradox. This paradox infers decisions appear more “comprehensive”Footnote 201 when EIAs are, in principle, undecidable. H1 explains that EIA norms invalidate EIAs that produce one-sided decisions. Such decisions lack the property of undecidability as they omit evaluation of numerous factors. They therefore lack knowledge, the selection of specific types of observation, and thus comprehensiveness.

Conversely, H1 explains that EIA norms validate EIAs that generate self-reflective learning. These decisions exhibit the property of undecidability as they observe and evaluate numerous factors. This involves facilitating collective learning about knowledge that is both known but also unknown. Accordingly, the potential of EIA norms therefore does not reside in eliminating uncertainty. Rather, it lies in how EIA norms incorporate contingency to cope with complexity. It resides in how EIA norms accentuate specific uncertainties that are more bounded by the risk-minimization standards of science. Yet, this facilitative and cognitive learning-orientation also hinges on due diligence norms’ normative closure.

II. H2: The Structural Disposition Paradox of Due Diligence Norms

H2 observes how due diligence norms displace the contingency paradox by generating specific stabilities. This emerges not primarily from determining consistencies within the sources of legal doctrine. Nor does it stem from prioritizing dispute resolution or environmental protection. Rather, it stems from the paradox of sustaining “adequately complex consistent decision-making.”Footnote 202 Due diligence norms strive for “ecological adequacy”Footnote 203 by incorporating best practices like the precautionary principle. This strategy fosters learning and adaptation to meet the complex risk-minimization standards of science. Yet, consistent decision-making that aligns with systematic integration rules remains also crucial.Footnote 204 Due diligence norms can only maintain environmental protection if they do not clash with other existing rules.

Seen this way, the structural disposition of due diligence norms, characterized by their normative closure, is not ideal. The need for systemic consistency demands tolerating a degree of ignorance towards facts that lack a legal framing. However, H2 helps explains why this is essential. It reveals that the legal constitution of facts is indispensable to secure legal confidence and certainty. Without this, IEL would forfeit law’s presumed ability to settle disputes that arise before it. Due diligence norms’ normative closure is the reason IEL can develop cognitive openness to its social context. Due diligence norms (H2) create the conditions for EIA norms to absorb contingencies (H1) and for cooperation norms to pacify conflicts (H3).

III. H3: The Paradox of Cooperation Norms’ Sustainable Development Aspirations

H3 illuminates the paradox of realizing sustainable development, a goal both essential and elusive. While sustainability goals promote cooperation and innovation, attaining sustainable development remains a distant prospect.Footnote 205 H3 demonstrates how cooperation norms sustain decision-making under such paradoxes. Their efficacy stems not from shared values, but from managing the interplay of knowledge and ignorance. Cooperation norms first employ adaptive mechanisms like technical consultationsFootnote 206 to adjust to changing situations. These consultations do not solve the sustainability paradox directly. Rather, they guide decision-makers through paradoxical terrains. Consultations allow decision-makers to pinpoint questions and thus learn from and act on specific types of knowledge.

Cooperation norms also function to mask the sustainability paradox by managing specified ignorance. This occurs when these norms legitimize a state’s right to “reasonable” natural resource use.Footnote 207 Such justification permits decision-makers to overlook certain negative impacts of resource exploitation, thus maintaining perceptions of purposeful action. Trust retention, however, requires balancing learning with non-learning. IEL can create opportunities for adaptation, yet this depends on its operative closure. The capacity of IEL to enhance scientific debates relies on connecting conditions with consequences. This involves linking legal violations— such as failing to share EIA findings—to specific legal repercussions. It also means accepting that IEL may refuse to learn from counterclaims. Even if outcomes prove unfavorable, upholding a semblance of legal order remains crucial for system stability.

The table below synthesizes how each hypothesis employs distinct methods to manage paradoxes within IEL.

Table 3. Paradoxical Dynamics and Systemic Management in IEL

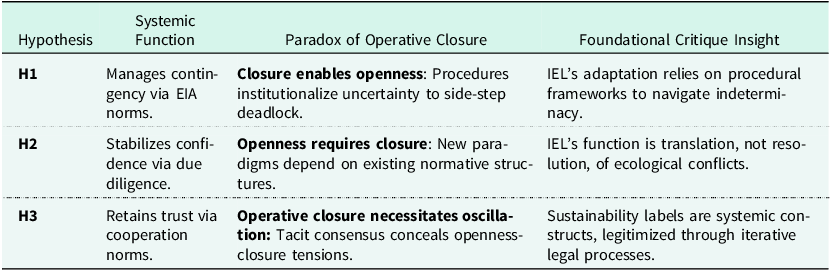

F. Reframing IEL via Operative Closure

Our reconstruction of IEL’s operative closure produces a peculiar synthesis of ambitious modesty.Footnote 208 This modesty appears as our reconstruction steps back from immediate challenges facing IEL practitioners. We avoid prescribing ideals for IEL or predicting whether IEL’s regulation of the SCS will be catastrophic or progressive. Yet our approach remains ambitious by transcending typical crisis-focused IEL discourse. By linking theory, method, and context, we offer a thickFootnote 209 sociological account of processes key for IEL’s continued function as a legal system. This foundational approachFootnote 210 establishes a new critical standard through three key insights.

First, H1 explores how EIA norms address the system problem of contingency. Unlike approaches relying on human rationality to control uncertainty,Footnote 211 H1 exposes the contingency paradox. This paradox reveals comprehensive EIAs require recognizing inherent uncertainty. EIA norms thus prioritize procedural mechanisms over outcomes to process such uncertainty. This procedural focus ensures openness to new evidence and critiques, resisting definitive closure. By mapping how EIA norms institutionalize contingency, H1 thus reconstructs IEL’s systemic potentiality. H1 shows how IEL uses contingency to avoid a cul-de-sac, to offer further opportunities, and to encourage further participation.

Second, H2 maps how due diligence norms address the system problem of confidence maintenance. H2 challenges the assumption that new paradigms like Ecosystem Integrity primarily drive change.Footnote 212 Change happens because of how systems handle their founding paradox: openness from closure.Footnote 213 Law’s structural disposition—its systemic design—prioritizes stabilizing expectations to sustain confidence. Due diligence norms conditionally incorporate new paradigms but must also uphold law’s stabilizing function. By tracing how these norms displace new paradigms, we map IEL’s systemic limits. H2 reveals IEL does not offer substantive resolution to the ecological challenges that new paradigms attempt to solve. Instead, it translates these irresolvable tensions into legally manageable conflicts.

Third, H3 reveals how cooperation norms address the system problem of trust retention. H3 moves beyond critiquing crisis-driven or ambition-focused frameworks. This shift does not ignore crisis narratives about unsustainable practices. Nor does it dismiss visionary narratives about sustainable development necessities. Instead, H3 redirects attention to how cooperation norms conceal sustainability paradoxes. The analysis maps how specific IEL processes maintain and construct this concealment. Visible controls show how IEL maintains concealment by linking conditions with legal consequences. Representative performances reveal how IEL constructs ecological progress through legitimizing decisions. By tracing these processes, we map how IEL builds trust in supposedly sustainable practices. H3 emphasizes that sustainability labeling stems not from inherent qualities. Rather, it emerges from deliberate decisions and systemic processes.

Together, these hypotheses offer an immanent critique of IEL by revealing the paradox of operative closure. H1 uncovers foundational dynamics by demonstrating how closure enables openness. It illuminates how IEL’s normative frameworks guide its cognitive capacity for adaptation. H2 explicates systemic transformation by revealing how openness depends on normative closure. It shows how IEL’s adaptive capacity relies on established normative structures. H3 explores how operative closure demands continuous shifts between openness and closure. Through this account, we develop new critical awareness of how IEL conceals paradoxes. Closure operates through tacit consensus, concealing unsolvable paradoxes. Openness counters with procedural norms that defer substantive resolution. Operative closure leverages this dynamic tension to empower IEL’s societal responsiveness, as summarized below:

Table 4. Systemic Dynamics of IEL’s Operative Closure

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the intellectual guidance of Professor David M. Ong, Professor Gaetano Pentassuglia, Professor Owen McIntyre, Associate Professor David J. Devlaeminck, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. This article benefited from discussions at the Centre for the Study of Law in Theory and Practice at Liverpool John Moores University and was presented at the 19th Annual Law and the Environment Conference hosted by the Centre for Law and the Environment, University College Cork. The author also thanks Dr. George William Lamb and Dr. Majida Ismael for their proofreading support. Appreciation is extended to the editorial team at the German Law Journal for their insightful comments and editorial assistance.

Competing Interests

The author declares none.

Funding Statement

No specific funding has been declared in relation to this article.