Introduction

Archaeological research increasingly highlights the importance of exchange networks in shaping social complexity; networks enable interactions, which foster social bonds and contribute to various forms of social organisation, including hierarchies (Crumley Reference Crumley1995; Barton Reference Barton2014; Kappeler et al. Reference Kappeler, Clutton-Brock, Shultz and Lukas2019). By studying social structures along a spectrum, researchers can gain a more nuanced understanding of how these networks function in different human communities, from egalitarian groups to complex, stratified societies (Chapman Reference Chapman2003: 33; Levy Reference Levy2009), and their impact on social stratification, co-operation and organisation (Stanish & Levine Reference Stanish and Levine2011; Carballo et al. Reference Carballo, Roscoe and Feinman2014).

Funerary practices provide crucial insights into the social complexity of ancient communities (McGuire Reference McGuire1983; McGuire & Paynter Reference McGuire and Paynter1991) but the heterarchical nature of social relations—in which power dynamics are interdependent rather than strictly ordered—complicates interpretation. While funerary rites and grave goods can provide insights into social stratification and identity construction, the development of social hierarchies cannot be reduced to a simplified representation of inequality (Espolin Norstein et al. Reference Espolin Norstein, Selsvold, Voutsaki, Espolin Norstein and Selsvold2024). Competition and negotiation between social ‘units’ shape behaviours and practices and reflect the broader sociopolitical landscape (Brass Reference Brass2014). Daems (Reference Daems2021) argues for a complex-systems approach that emphasises how relationships and exchange shape diverse social structures, and a growing body of literature on sociopolitical complexity and networks of exchange in African archaeology is challenging traditional socioevolutionary interpretations (McIntosh Reference McIntosh1999; Pauketat Reference Pauketat2007; MacEachern Reference MacEachern and Wynne-Jones2015), emphasising how inter-regional cultural exchange contributes to the dynamics of domination and stressing that social complexity encompasses various factors beyond mere hierarchy.

The concept of ‘heterarchy’ presents an alternative to the limitations of the neo-evolutionary framework by illustrating how decision-making in societies is dispersed rather than centralised (Crumley Reference Crumley1995). This perspective uncovers complexity in systems that may appear simple at first glance, such as clan and lineage structures, highlighting specialised roles and interactions with more centralised entities (Davies Reference Davies, Mitchell and Lane2013). By using a dynamic, non-hierarchical model, researchers can better understand the complex social organisations and transformation processes found in different African societies.

This research focuses on the Meroitic townsite of Kedurma in the Middle Nile Valley, which dates from the fourth century BC to the fourth century AD. Recent excavations of 50 tombs at this site have provided extensive data on funerary practices and social complexity in north-eastern Africa. The analysis of these findings aims to explore the links between social structures and cultural practices while addressing broader questions of identity and social interaction. The insights gained are crucial for a deeper understanding of social complexity that goes beyond simplistic subsistence narratives to better characterise human societies in Africa and more broadly.

Research context

The kingdom of Kush, located within the territory of present-day Sudan, serves as an important case study for understanding the complexity of early African societies. This polity on the Middle Nile developed into a formidable power, influencing a large region beyond its borders (Edwards Reference Edwards2004; Török Reference Török, Godlewski and Łajtar2008). The history of Kush can be divided into two major periods: the Napatan (ninth to fourth centuries BC) and the Meroitic (third century BC to fourth century AD). The Napatan period is characterised by strong Egyptian influence from the north, which can be seen in the royal symbolism, language and writing systems and in references to Egyptian religious, artistic and literary traditions. The Meroitic period marked a substantial change, as local African traditions from the Sudanese hinterland and steppes flourished. This period is characterised by advances in literacy, religion, architecture and art, culminating in a unique articulation of social and cultural identity (Edwards Reference Edwards1996, Reference Edwards2004). With the expansion of trade routes linking the capital, Meroe, with Greco-Roman Egypt and the Near East, the regional economy was increasingly interconnected, weakening the direct control of the ruling elite and enabling the wider exchange of goods and ideas (Haaland Reference Haaland2014: 651–52).

The sociopolitical and economic changes of the Meroitic period precipitated transformations in demographic patterns and cultural practices, particularly burial customs (Edwards Reference Edwards1996, Reference Edwards1998a; Török Reference Török, Godlewski and Łajtar2008). Excavations in the Meroitic Kingdom have unveiled a complex array of burial practices that reveal both commonalities and regional differences among the communities of ancient Nubia (el-Tayeb & Kolosowska Reference el-Tayeb and Kolosowska2005; Francigny Reference Francigny2009, Reference Francigny2016; Sakamoto Reference Sakamoto, Anderson and Welsby2014). While ongoing research is enriching our understanding of these customs, it is heavily focused on the Nile Valley and comprehension of burial traditions that originated outside this region—which may provide crucial insights into the broader cultural dynamics of the Meroitic Kingdom (Francigny Reference Francigny2012: 52)—remains limited. This gap highlights the need for deeper exploration of how local Indigenous practices, influenced by distinct environmental, social and political contexts, interacted with overarching Meroitic customs.

Kedurma

The site of Kedurma, located near the River Nile and approximately 595km north-west of ancient Meroe (Figure 1), covers an area of 3–4ha and includes public buildings, residential areas and a large cemetery. Most northern Meroitic sites were lost beneath the Lake Nasser reservoir following the construction of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960s, making this combination of settlement and cemetery unusual (Edwards Reference Edwards1995: 46). Evidence of occupation at the site extends to at least the fourth century BC, and excavations conducted by the University of Khartoum in 2021 and 2023 uncovered 50 tombs, revealing a diversity of funerary architecture, burial practices and grave goods.

Figure 1. The geographical location of Kedurma (figure by author).

The diversity of burial practices raises the possibility that the burials reflect ethnic, cultural, social or political differences, and thus rich local traditions. Located at the northern end of the third cataract of the Nile, royal power is likely to have had a more limited influence on funerary customs at Kedurma than at other monumental sites such as Meroe and Barkal. This is manifest in the simpler burial practices observed at Kedurma and calls for a reassessment of power dynamics during the Meroitic period, including an examination of how individuals outside the royal lineage—though possibly still of relatively high status—could influence power structures and ritual practices, and even the functioning of the state. As such, Kedurma has the potential to enhance our understanding of Meroitic burial patterns and their broader significance in the context of African history.

Materials and methods

Extensive surface surveys were used to map visible features and artefacts at Kedurma, which indicated the archaeological significance of the site and the likely presence of a cemetery. Drone photography was then used to accurately delineate the extent and boundaries of the site and to identify areas for further exploration (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Contour map of the cemetery site (figure by Sebastien Poudroux).

Subsequent geophysical survey permitted the identification of graves, as there are no surface markers in the cemetery. This involved using a Geoscan Fluxgate Gradiometer for magnetometer assessments over 20 × 20m blocks, taking measurements at 0.5m intervals and additional measurements at 0.25m intervals. A resistivity survey was also conducted using a Geoscan RM15 with a crosshead spacing of 1m, taking one or two measurements per metre (Abdelwahab et al. Reference Abdelwahab, Burkhardt, Khalil, Posluschny, Lambers and Herzog2008: 2–4). A total of 12 grids were established in different sections of the cemetery (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Topography of the site overlaid with the distribution of the grids. Excavated grids are marked with graves (figure by Hamza Alhassan).

Excavation then targeted locations with the clearest geomagnetic signals: grids 1, 3, 5, 7 and 12. A total of 50 tombs were excavated during the 2021 and 2023 seasons, which were mapped using a total station (Figure 3). A programme of post-excavation fieldwork meticulously documented the diversity of burials uncovered and the layout of the site, while bioarchaeological analysis was conducted on 135 individuals excavated during the 2023 season (the current conflict in Sudan has delayed study of material from the 2021 season, which is stored in Khartoum).

Results

Based on the distribution and density of the 50 excavated tombs, as many as 1000 may have existed across the 4ha cemetery. The extended use of the cemetery as the currently available evidence suggests, dates from the approximately fourth century BC, to the fourth century AD and its diverse range of burial practices and rich material culture (in conjunction with findings from the associated settlement; Bashir Reference Bashir2022), suggest that Kedurma may reflect broader trends in Upper and Lower Nubia, revealing links to wider socioeconomic networks as well as local traditions, and demonstrating the dynamic interaction between internal community organisation and external influences.

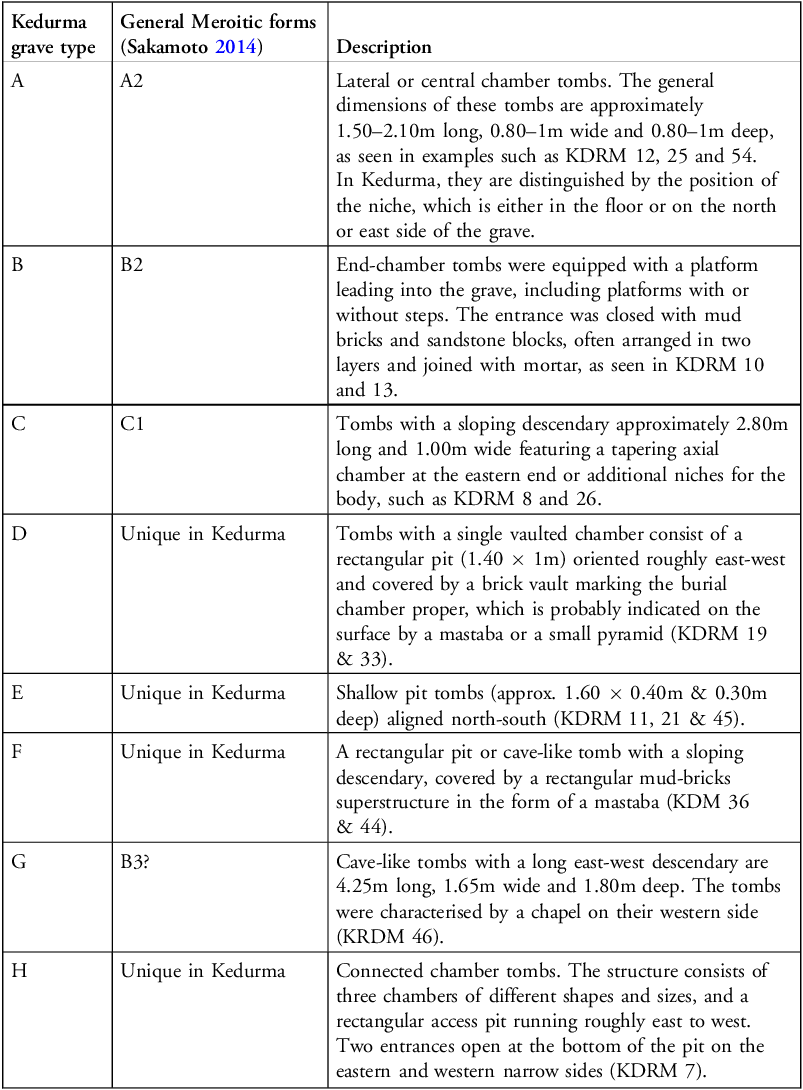

The 50 excavated tombs exhibit stylistic diversity and can be categorised into eight forms, A–H (Figure 4 & Table 1), based on typologies commonly used in Sudanese archaeology (Griffith Reference Griffith1924: 144–46; Reference Griffith1925: 57–63; Fernández Reference Fernández1980; Näser Reference Näser and Welsby1999; el-Tayeb & Kolosowska Reference el-Tayeb, Kolosowska, Näser and Lange2007).

Figure 4. Illustrations of grave forms A–H found at Kedurma (figure by author).

Table 1. Grave forms at Kedurma.

The site is distinguished by its mixture of Lower and Upper Nubian burial traditions, as well as some new forms. Most tombs lack surface markings; only three forms (D, F, G) have surface structures, accounting for only eight per cent of the excavated tombs at Kedurma. All but two of the tombs (both of form E) are orientated east–west, and most have a sloping ramp leading to a burial chamber. The entrances to these chambers were usually sealed with mud bricks and occasionally covered with stone slabs (Figure 5).

Figure 5. KDRM 27 and 10 as examples of typical Kedurma tombs (figure by author).

Based on tomb orientation, the heads of the deceased generally faced west, though in seven cases individuals faced east. Bodies were typically laid on their backs with hands resting on the pelvis, and were usually interred wrapped in textile shrouds and inside palm coffins (Figure 6). Some were placed on pieces of leather (KDRM 11, 23), suggesting a continuity of ‘Nubian’ burial practices from the much earlier Bronze Age and the Kerma Kingdom period (c. 2500–1500) (Bonnet & Honegger Reference Bonnet, Honegger, Emberling and Williams2020: 216).

Figure 6. The use of coffins and textiles (see 6b, next to the north arrow) in Kedurma tombs (A, KDRM 16/B, KDRM 11) (figure by author).

Approximately 135 skeletons from the 2023 season were analysed. The specimens range from almost intact skeletons (e.g. KDRM Grid 5 Grave 37 & Grid 3 Grave 53) to fragmented remains requiring minimum number of individuals (MNI) assessments, particularly in disturbed surface context such as Grid 5.

Macroscopic osteology was used to estimate biological sex and age, thereby constructing the demographic profile. In minors, dental development and eruption patterns were used to determine age (AlQahtani et al. Reference AlQahtani, Hector and Liversidge2010). Sex determination required examination of the physical characteristics of the pelvic bones, skull and mandible, which develop only after puberty. Individuals under the age of 15 years were excluded. Only the biological sex of adults was assessed. Age was estimated using degenerative changes in the pelvic bones (pubic symphysis and auricular surface), sternal rib extremities, and dental attrition.

The demographic study identified 20 females, 30 males and 51 individuals of undetermined sex (lacking diagnostic criteria or classified as minors). Nineteen minors were infants and children under the age of 14 years. Among the adult population, 14 were classified as young adults (under the age of 30 years at the time of death), while 68 were categorised as middle-aged, elderly, or adults of indeterminate age due to fragmentation.

Burial practices included both individual and multiple interments. Both tomb types were documented, although no demographic patterns were observed. Intact graves were found for a 10.5-year-old child in KDRM Grid 5 Grave 37 and a 16.5-year-old female in Grave 50. KDRM Grid 3 Grave 53 contained an infant, a 5.5-year-old child, a teenager, and four individuals wrapped in textiles, all well preserved. This demonstrates that sub-adults were interred in individual graves alongside adults (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Niches for child burials in the wall of grave 16 (figure by author).

The burial practices observed in the excavated tombs are typically consistent with general Meroitic traditions, while certain features may reflect specific local Lower Nubian customs. Tomb forms B and C, for example, are associated with a tribal or proto-state elite during the late Meroitic period and the emergence of Christianity in Lower Nubia (third to mid-fourth century AD) (el-Tayeb & Kolosowska Reference el-Tayeb and Kolosowska2005: 11–23; Obłuski Reference Obłuski2008: 529). In contrast, form H is found in Nubia from the New Kingdom onwards, particularly during the Twenty-fifth Dynasty (c. 750–655 BC) at Hillat el Arab near Jebel Barkal and other sites (Vincentelli Reference Vincentelli1999: 33). The material culture from form H tombs at Kedurma—particularly the pottery—also indicates the early use of this tomb type, probably dating to the Napatan period, as suggested by similar Napatan pottery at the Kawa site, located approximately 45 km south of Kedurma (Welsby Sjöström Reference Welsby Sjöström2023).

Insights from the grave goods

Most of the tombs (n = 46) were opened at some point in the past, either for reuse or looting; 14 of these were completely cleared of all their contents. In those that had not been cleared, the presence of various objects, such as local pottery (e.g. in tombs 31, 32 & 39), imported pottery (e.g. in tombs 7, 10 & 29), beads (tomb 11; Figure 8c) and iron artefacts (tombs 20, 37; Figure 8d) indicates a complex ritual framework in which grave goods played a crucial role in the burial process. Notable artefacts include an inscribed stele from tomb 30 (form C; Figure 8a), a scraper (tomb 7, form H) made of faience. This oval object featuring a domed upper surface and a flat seal, held significant symbolic meaning in ancient Egypt, primarily representing rebirth and protection. Further finds include fine pottery from tombs 10, 18 (form B; Figure 8b) and 46 (form G), as well as Ba statues and parts of sandstone offering tables found on the site surface.

Figure 8. Objects from the cemetery: a) the stele (grave 30); b) a Meroitic painted bowl (grave 18); c) light-coloured disc beads made of bone or shell material (grave 11); d) iron rings (grave 20) (figure by author).

The intact (sealed) tombs 10, 37, 41 and 53 provide key insights into Meroitic burial customs and allow a detailed analysis of the arrangement of artefacts, reflecting broader archaeological patterns. The positioning of everyday objects such as pottery near the head of the deceased and the arrangement of personal jewellery such as rings and anklets worn on the body during burial indicate a belief in an afterlife in which such possessions were essential (Francigny Reference Francigny, Emberling and Williams2020: 600). When compared with sites such as Gabati and Berber in central Meroe (Edwards Reference Edwards1998b; Bashir Reference Bashir2010) and Amir Abdalla and Sai in northern Sudan (Fernandez Reference Fernández1980; Francigny Reference Francigny2012), the finds from the intact and disturbed tombs at Kedurma reveal broad cultural similarities in Meroitic funerary traditions, including the use of coffins, and regional differences in ornamentation and ceramics.

Internal chronology

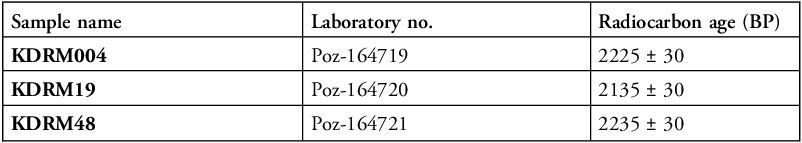

Three radiocarbon dates were obtained from charcoal samples taken from layers associated with human remains in tombs KDRM004, which has a stone structure (form G), KDRM19 (form F) and KDRM48 (form A). Radiocarbon dating was conducted at the Radiocarbon Laboratory in Poznań and the results were calibrated using OxCal v.4.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and the IntCal20 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2020). The results indicate a time frame of the fourth to second centuries BC (Figure 9 & Table 2).

Figure 9. Calibrations for radiocarbon dates from three charcoal samples from the cemetery (figure by author).

Table 2. Radiocarbon dates for the charcoal samples (for calibrations, see Figure 9).

Some tombs (10, 18 and 53, in particular) can be dated to the Classic Meroitic phase, late first century BC to first century AD, based on stylistic comparison of pottery and tomb architecture with well-dated artefacts excavated at other sites, including Barkal (Dunham Reference Dunham1957: fig. 136), Faras (Griffith Reference Griffith1924: pls. XLI. 13-1) and Ballana (Williams Reference Williams1991: 201–203, fig. 4-5). Palaeographic analysis places the stele from tomb 30 in the transitional C/late A period in the second half of the third century AD. This timeframe is consistent with the dating of other funerary texts from Lower Nubian sites such as Karanog, Sai and Sedeinga (Bashir & Rilly Reference Bashir and Rilly2023).

Discussion

The development of Meroitic burial practices

Previous examinations of Meroitic funerary practices have identified both common traditions and regional differences in Lower and Upper Nubia from the third century BC to the third century AD (Woolley & Randall-MacIver Reference Woolley and Randall-MacIver1910: 32–45; Griffith Reference Griffith1925: 63–69, pl. XXII; Fernandez Reference Fernández1980: 14; Francigny Reference Francigny2009: 92–96). Three typological sequences for Meroitic chronology (A, B and C) have been suggested, with different subtypes based on tomb structure (Sakamoto Reference Sakamoto, Anderson and Welsby2014).

The eight burial forms at Kedurma build on this classification, with forms A, B, C and G representing known Meroitic types (Table 1). Form B, which is characterised by a long staircase leading to the (typically royal) burial chamber, is simplified at Kedurma with only two steps present (Sakamoto Reference Sakamoto, Anderson and Welsby2014). A progressive reduction through time in the numbers of steps in Meroitic Nubia has been interpreted to indicate a decline in royal authority and a shift of influence to local chieftains, suggesting that social stratification may have been fluid and influenced by wealth and familial ties (Edwards Reference Edwards1998b; Török Reference Török2009: 456).

The other tomb forms found at Kedurma (D, E, F & H) are less common, demonstrating the diversity of burial customs. Form D is found at other sites such as Karanog (Woolley & Randall-Maclver Reference Woolley and Randall-MacIver1910: 18) and Sadeinga (Rilly et al. Reference Rilly, Francigny and David2020: 74) but has not been included in the general Meroitic burial classification. Form F is typically associated with Upper Nubian sites from the early Napatan period such as Kuru, used by kings and elites. The form at Kedurma is smaller and attributed to the Meroitic period based on the pottery. Forms E and H are not attested elsewhere but pottery typologies allow classification of form E as Meroitic and form H as Napatan or as earlier structures reused during the Meroitic period.

Special niches cut into tomb walls for child burials are only found in Kedurma (Figure 8). At other sites, children were generally buried in multiple or single graves (cf. Näser Reference Näser and Welsby1999). Many burials were disturbed, making classification of practices such as reuse and grave robbing—which may have been part of common behaviour (Näser Reference Näser and Welsby1999)—difficult. Nevertheless, the tombs at Kedurma offer valuable insights into the dynamics of burial customs and social power during the Meroitic period.

Orientation and structure of the graves

Substantial typological variation is observed in the 50 excavated tombs at Kedurma. Forty-eight tombs are oriented east–west; 17 have entrances to the east, nine tombs are entered from the west. There are also two shallow pit tombs orientated north–south, as well as individual niches. This diversity illustrates the complexity of the site. The coexistence of different orientations and tomb types indicates a society that was both traditional and adaptive, likely influenced by various factors such as geography and cross-cultural interactions given the site’s location in a culturally Nubian frontier zone (Osman & Edwards Reference Osman and Edwards.2012). The east–west orientation of the tombs, the use of coffins (as in tombs 10, 16 & 46) and artefacts such as scarabs (tomb 7), and the presence of architectural forms F, G and H, which originated in Egypt, evidence the interplay of Egyptian and Nubian burial practices.

At least 39 of the tombs contained multiple individuals, suggesting that certain areas of the cemetery were used over extended periods and possibly indicating familial relationships.

Other instances of Meroitic tomb reuse are documented (Williams Reference Williams1991: 255; Francigny Reference Francigny2012, Reference Francigny, Emberling and Williams2020). As at Qustul, Ballana and Abu Simbel North cemeteries (Williams Reference Williams1991; Naser 1991), repeated reopening disturbs earlier deposits and mixes artefacts from different periods, which complicates tomb chronology (Edwards Reference Edwards1998b).

Cultural and social identity

The diversity of tombs within the Meroitic kingdom in Lower Nubia suggests a complex sociopolitical landscape that was characterised by overlapping identities (Adams Reference Adams, Wlodzimierz and Adam2008; Francigny Reference Francigny, Emberling and Williams2020: 598). The elaborate tombs of the elite, positioned between the kings and the common people, contained luxury items such as inlaid caskets and decorated vessels that demonstrated their elevated status. These officials usually held hereditary positions, especially at Karanog and Sedeinga (Rilly & Francigny Reference Rilly and Francigny2011: 77–79). In addition, their tombs contained characteristic elements such as Ba statuettes, offering tables and inscribed stelae, indicating the presence of an educated and wealthy official class (Török Reference Török1979; Rilly & Francigny Reference Rilly and Francigny2011: 75).

Certain features of elite tombs also point to advances in architectural techniques, evolving concepts of the afterlife and changing perceptions of elite authority. Evidence from multiple sites suggests that the distinction between royal and aristocratic tombs was not absolute, revealing a more nuanced understanding of social identity, where lesser royal personages coexisted with elite personages, as seen in the burials at the Western Cemetery at Meroe (Adams Reference Adams1977; Abdalla Reference Abdalla1984). This coexistence can also be seen in the Kedurma settlement, where there is no clear demarcation between the high-status ‘Building A’, associated with the elite, and the structures surrounding it. In the cemetery, the presence of form G tombs, typically associated with elites, alongside other forms, also demonstrates this blending. The association of a funerary stele with a form C tomb, while other tombs of this form lack characteristic elite elements, further indicates that some tomb forms were used by individuals with different social identities. Thus, the burial practices observed at Kedurma may serve as a tableau for understanding the cultural dynamics and fluid social structure within the Meroitic state, showing how individual identity was interwoven with collective memory.

Grave diversity and distribution

Despite the substantial variety of tombs found at other Meroitic sites such as Faras and Amir Abdella (Griffith Reference Griffith1925; Fernandez Reference Fernández1980), research to date has focused predominantly on stylistic analysis. This limited perspective hinders comparative analyses, as the typological diversity between graves is often interpreted only in terms of chronological relationships (Sakamoto Reference Sakamoto, Anderson and Welsby2014). At Kedurma, however, chronology alone cannot explain the variety of tombs as, based on artefact typologies, many of the different forms appear to be largely contemporaneous and overlap in time. Instead, the diversity of burial practices at Kedurma may be the result of a combination of factors related to social complexity, including hierarchy. While numerous elements such as gender, age and socioeconomic organisation influence the burial practices of a society, the analysis of the eight grave types at Kedurma shows that biological sex and age did not predetermine burial types (Figure 4 & Table 1).

The irregular distribution of tomb types at Kedurma further complicates our understanding, indicating a complex social structure in which location, architecture and grave goods collectively expressed social status and identity. The unique organisational patterns of the site—best exemplified by the distinctive east–west aligned chapel structures (form G) juxtaposed with the asymmetrical burial arrangements—indicate not only architectural advances but also a sophisticated sociopolitical hierarchy. This architecture indicates the presence of elite families who sought to represent their status through monumental burial practices.

This type of tomb (form G) was located at the lowest point of the cemetery and was constructed on an orientation perpendicular to the high-status Building A of the settlement. This arrangement suggests a connection to a wealthier or aristocratic population. Although only two heavily looted tombs of this type (41 & 46) were excavated, the remaining grave goods and the unique grave shapes emphasise the importance of those buried there.

Overall, no clear pattern in the distribution of different tomb types across the cemetery can be discerned; multiple forms, possibly contemporaneous, were uncovered in each excavated grid. Grid 5, for example, contained 14 tombs of five different forms (A, B, D, F & G), illustrating a broad spectrum of burial customs. Individuals from different age groups and both sexes were buried in the cemetery, perhaps indicating that certain burial practices were reserved for certain segments of society rather than specific individuals.

Grave goods and social status

The presence of luxuriously crafted objects (see online supplementary material (OSM) Table S1) such as a scraper from tomb 7, finely stamped and decorated pottery with Greco-Egyptian iconography from tomb 10, a finely decorated bowl with religious iconography—including an ankh, a was-sceptre and lotus flowers—from tomb 18 (Figure 9b) and a finely carved stele with Meroitic cursive script from tomb 30 (Figure 9a), alongside more utilitarian objects from other tombs (e.g. 20, 27 & 46) demonstrates the complex negotiation of identity in funerary contexts. The variability of grave goods—from elaborately inscribed stelae to ordinary ceramic vessels—suggests that funerary practices served not to mark endpoints of life, but also as active fields for social negotiation and identity construction.

Funerary practices are deeply rooted in tradition and yet remain adaptable over time (Robb Reference Robb and Laneri2007), highlighting the complexity of social structures in early societies. Inscriptions on grave goods from various site denote roles with overlapping statuses within the Meroitic community, such as governor, specialised priest and royal scribe, highlighting the fluid nature of identity formation and challenging static interpretations of social roles (Bashir & Rilly Reference Bashir and Rilly2023).

Finds from the cemetery and settlement of Kedurma—pottery and textile workshops, imported artefacts such as amphorae and Aswani cups, and Greco-Egyptian iconography on painted and stamped pottery—shed light on the role of local craftsmen and trade, contributing to a better understanding of Meroitic society. They reveal a complex network of social exchange characterised by the convergence of regional networks. This reflects an ongoing dialogue between local practices and broader sociopolitical currents, acknowledging the multiple influences that contribute to social complexity. Rather than subscribing to dominant narratives, this research emphasises the idea of social complexity as a mosaic of interactions that shaped identities within the larger Meroitic state (McIntosh Reference McIntosh1999; Pauketat Reference Pauketat2007).

Conclusion

Research conducted at Kedurma provides important insights into the complex interplay of funerary practices and social organisation within the Meroitic state and highlights the nuanced nature of identity construction and social organisation in ancient Nubia. The excavation of 50 tombs within this well-defined burial site has revealed a diverse range of funerary architecture, burial practices and grave goods that illustrate the dynamic sociopolitical landscape of the Meroitic period. By focusing on variations in funerary customs, including structural diversity and the arrangement of grave goods, this study enriches our understanding of social relations, power dynamics and cultural identities in a historically significant but often globally under-reported region.

The results suggest that Kedurma serves as a microcosm for the study of broader Meroitic customs, in which local traditions interact with external influences from rapidly developing trade networks and cultural exchange, particularly with neighbouring Egypt. Funerary architecture and associated artefacts reflect the coexistence of different cultural practices and social stratifications and show that identity in the Meroitic state was diverse and adaptable. Rather than a linear path to increasing complexity or rigid hierarchies, the evidence from Kedurma points to a fluid social structure that was characterised by negotiations and the actions of different community members, expressed in part through funerary practices.

The burial practices observed at Kedurma challenge traditional, simplistic models of social development and reveal a sophisticated interplay between local customs and broader sociopolitical currents. This research thus contributes not only to the specific understanding of Meroitic burial traditions, but also to the broader discourse on social complexity within ancient African civilisations.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the National Geographic Society (grant no. NGS-60674-R-20), the Michela Schiff-Giorgini Foundation and the British Institute in Eastern Africa (BIEA). Radiocarbon dating was provided by the African Chronometric Dating Fund (Society of Africanist Archaeologists, PanAfrican Archaeological Association) and BIEA. Manuscript preparation was supported by the British Academy and the Association of Commonwealth Universities (via the ‘Rewriting World Archaeology’ programme, Durham University 2025) and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (University of Münster).

Online supplementary material (OSM)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10278 and select the supplementary materials tab.