1. Introduction

Small-scale, untethered microrobots are attracting increasing interest due to their potential applications in medicine and bioengineering. However, they still face many challenges, such as their mobility and powering (Sitti et al. Reference Sitti, Ceylan, Hu, Giltinan, Turan, Yim and Diller2015; Ceylan et al. Reference Ceylan, Giltinan, Kozielski and Sitti2017). A promising propulsion mechanism is acoustic driving, which, unlike many other approaches, is biocompatible and relatively easy to implement in medical applications. The most common propulsion mechanism for acoustically driven swimmers involves exploiting a gas cavity mounted on the swimmer. Indeed, gas cavities are very good resonators and allow the exploitation of different physical mechanisms for propelling an object (Dijkink et al. Reference Dijkink, Van Der Dennen, Ohl and Prosperetti2006; Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Lu, Nourhani, Lammert, Stratton, Muddana, Crespi and Huang2015; Bertin et al. Reference Bertin, Spelman, Stephan, Gredy, Bouriau, Lauga and Marmottant2015). Attempts to make these swimmers steerable typically involve multiple gas cavities, which results in increased swimmer size (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Lu, Nourhani, Lammert, Stratton, Muddana, Crespi and Huang2015; Liu & Cho Reference Liu and Cho2021) or reduced propulsion efficiency compared with a monodirectional design (Spelman, Stephan & Marmottant Reference Spelman, Stephan and Marmottant2020). Additionally, bubbles, and thus swimmers equipped with gas cavities (Luo & Wu Reference Luo and Wu2021), are naturally attracted to walls, not only due to lateral forces induced by streaming vortices, but also due to secondary Bjerknes forces between the bubble and its mirror image reflected by the wall.

Some of the drawbacks of swimmers equipped with a gas cavity can be circumvented with entirely solid swimmers. One type of entirely solid swimmers consists of two spheres connected by a spring (Klotsa et al. Reference Klotsa, Baldwin, Hill, Bowley and Swift2015; Dombrowski & Klotsa Reference Dombrowski and Klotsa2020). Another type of solid swimmers are sperm-like objects. A first demonstration of such a sperm-like swimmer was provided by Ahmed et al. (Reference Ahmed, Baasch, Jang, Pane, Dual and Nelson2016), who used a few micrometre-long, axisymmetric objects composed of a rigid head and a flexible tail. The objects were set into resonance at

![]() ${90}\,\textrm {kHz}$

, resulting in the propulsion of the swimmer. Larger, sperm-like two-dimensional (2-D) swimmers, of the order of a hundred micrometres and made entirely of polymer, were designed by Kaynak et al. (Reference Kaynak, Ozcelik, Nourhani, Lammert, Crespi and Huang2017). Furthermore, the principle has since been applied to larger, more complex objects (Dillinger, Nama & Ahmed Reference Dillinger, Nama and Ahmed2021). It is generally assumed that the propulsion mechanism is microstreaming induced around the oscillating swimmer. This microstreaming, due to dissipation in the viscous boundary layer, is a relatively slow flow (with respect to the fast acoustic oscillations). While the presence of such flows is indeed supported by experimental evidence (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Baasch, Jang, Pane, Dual and Nelson2016; Dillinger et al. Reference Dillinger, Nama and Ahmed2021), conducting a repeatable study is challenging, and a detailed understanding of the precise underlying mechanisms is still lacking. Yet, this understanding is essential for further improving the design of such entirely solid swimmers and, most importantly, for addressing their steerability.

${90}\,\textrm {kHz}$

, resulting in the propulsion of the swimmer. Larger, sperm-like two-dimensional (2-D) swimmers, of the order of a hundred micrometres and made entirely of polymer, were designed by Kaynak et al. (Reference Kaynak, Ozcelik, Nourhani, Lammert, Crespi and Huang2017). Furthermore, the principle has since been applied to larger, more complex objects (Dillinger, Nama & Ahmed Reference Dillinger, Nama and Ahmed2021). It is generally assumed that the propulsion mechanism is microstreaming induced around the oscillating swimmer. This microstreaming, due to dissipation in the viscous boundary layer, is a relatively slow flow (with respect to the fast acoustic oscillations). While the presence of such flows is indeed supported by experimental evidence (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Baasch, Jang, Pane, Dual and Nelson2016; Dillinger et al. Reference Dillinger, Nama and Ahmed2021), conducting a repeatable study is challenging, and a detailed understanding of the precise underlying mechanisms is still lacking. Yet, this understanding is essential for further improving the design of such entirely solid swimmers and, most importantly, for addressing their steerability.

In this paper, we study the microstreaming induced by a vibrating cylindrical cantilever, used as a simple representation of a swimmer tail. One end of cantilever is attached to a vibrating glass support, which is excited by a piezoelectric transducer. A particular interest is devoted to the streaming structures perpendicular to the cantilever axis and to their potential for steering a swimmer.

The streaming around an oscillating cylinder has been widely studied in the past. However, aside from a few exceptions discussed below, these studies generally share two important limitations: (i) the cylinder is typically considered rigid, allowing the system to be simplified to a 2-D problem, and (ii) the cylinder undergoes pure back-and-forth oscillations, which we will refer to as rectilinear oscillations in the following.

Experimental evidence of streaming around a rectilinearly oscillating cylinder was reported as early as the 1930s, both in air (Carrière Reference Carrière1929; Andrade Reference Andrade1931) and in water (Schlichting Reference Schlichting1932). First theoretical considerations by Schlichting (Reference Schlichting1932) were followed by a broader discussion in the early 1950s (Andres & Ingard Reference Andres and Ingard1953a

,Reference Andres and Ingard

b

; Holtsmark et al. Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954; Raney, Corelli & Westervelt Reference Raney, Corelli and Westervelt1954; Westervelt Reference Westervelt1953a

,

Reference Westerveltb

). The main concern at that time was to explain the discrepancies between the different experimental observations. All experiments had recorded streaming patterns divided into four quadrants, which are today known as the typical dipole pattern. However, some experiments reported liquid inflow at the poles (on the

![]() $x$

-axis, along the direction of the oscillatory motion) (Carrière Reference Carrière1929; West Reference West1951), while others observed outflow at the poles on the

$x$

-axis, along the direction of the oscillatory motion) (Carrière Reference Carrière1929; West Reference West1951), while others observed outflow at the poles on the

![]() $x$

-axis (Schlichting Reference Schlichting1932; West Reference West1951) and yet others identified additional zones of recirculation near the cylinder (Andrade Reference Andrade1931). The seminal theoretical works by Schlichting (Reference Schlichting1932), Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954) and Raney et al. (Reference Raney, Corelli and Westervelt1954) allow us to understand that the streaming consists of an inner region, with a width of the order of the viscous boundary-layer thickness

$x$

-axis (Schlichting Reference Schlichting1932; West Reference West1951) and yet others identified additional zones of recirculation near the cylinder (Andrade Reference Andrade1931). The seminal theoretical works by Schlichting (Reference Schlichting1932), Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954) and Raney et al. (Reference Raney, Corelli and Westervelt1954) allow us to understand that the streaming consists of an inner region, with a width of the order of the viscous boundary-layer thickness

![]() $\delta$

, and an outer region extending beyond it. The boundary-layer thickness is defined as

$\delta$

, and an outer region extending beyond it. The boundary-layer thickness is defined as

![]() $\delta = \sqrt {2\nu /\omega }$

(although some authors use

$\delta = \sqrt {2\nu /\omega }$

(although some authors use

![]() $\delta = \sqrt {\nu /\omega }$

), with

$\delta = \sqrt {\nu /\omega }$

), with

![]() $\nu$

the kinematic viscosity,

$\nu$

the kinematic viscosity,

![]() $\omega$

the angular frequency and the frequency

$\omega$

the angular frequency and the frequency

![]() $f = 2\pi \omega$

. More precisely, a universal curve can be found between the ratio

$f = 2\pi \omega$

. More precisely, a universal curve can be found between the ratio

![]() $\delta /\!R$

, with

$\delta /\!R$

, with

![]() $R$

the radius of the cylinder, and the ratio

$R$

the radius of the cylinder, and the ratio

![]() $\delta _{\textit{stream}}/\!R$

, with

$\delta _{\textit{stream}}/\!R$

, with

![]() $\delta _{\textit{stream}}$

the thickness of the inner streaming region (Raney et al. Reference Raney, Corelli and Westervelt1954). When

$\delta _{\textit{stream}}$

the thickness of the inner streaming region (Raney et al. Reference Raney, Corelli and Westervelt1954). When

![]() $\delta /\!R$

increases,

$\delta /\!R$

increases,

![]() $\delta _{\textit{stream}}/\!R$

increases as well. Between the above cited experiments,

$\delta _{\textit{stream}}/\!R$

increases as well. Between the above cited experiments,

![]() $\delta /\!R$

varies from negligibly small to dominant in the field of view, which explains the different flow directions. This is also illustrated in figure 1 for a cylinder of a fixed radius of

$\delta /\!R$

varies from negligibly small to dominant in the field of view, which explains the different flow directions. This is also illustrated in figure 1 for a cylinder of a fixed radius of

![]() ${100}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

and water viscosity so that the thickness of the inner streaming zones depends only on the frequency. At lower frequencies, the boundary layer is relatively thick, and only the inner streaming region is visible within the field of view. At higher frequencies, the inner region becomes negligibly small, and the outer streaming dominates the field of view. It is noteworthy that the oscillation amplitude does not qualitatively alter the streaming pattern, provided that we remain within the validity of the model, meaning that the amplitude remains small compared with the cylinder radius. Two further important conclusions are reported by Raney et al. (Reference Raney, Corelli and Westervelt1954). Firstly, they propose an additional term to Holtsmark’s model to incorporate Stokes drift, thereby correcting the error caused by describing the cylinder’s motion from a Lagrangian perspective and the flow field from an Eulerian one. Secondly, their experiments confirm the earlier theoretical proof by Westervelt (Reference Westervelt1953a

) that the streaming generated by an oscillating cylinder in a quiescent liquid is equivalent to that generated by an oscillating fluid around a stationary cylinder. For the theoretical streaming to satisfy this result, Stokes drift must be included in the calculations in both reference frames. In parallel, Riley (Reference Riley1965) and others put the calculation of streaming using the method of matched asymptotic expansions onto firm ground. Unlike Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954), Riley’s work is generally in the limit of small

${100}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

and water viscosity so that the thickness of the inner streaming zones depends only on the frequency. At lower frequencies, the boundary layer is relatively thick, and only the inner streaming region is visible within the field of view. At higher frequencies, the inner region becomes negligibly small, and the outer streaming dominates the field of view. It is noteworthy that the oscillation amplitude does not qualitatively alter the streaming pattern, provided that we remain within the validity of the model, meaning that the amplitude remains small compared with the cylinder radius. Two further important conclusions are reported by Raney et al. (Reference Raney, Corelli and Westervelt1954). Firstly, they propose an additional term to Holtsmark’s model to incorporate Stokes drift, thereby correcting the error caused by describing the cylinder’s motion from a Lagrangian perspective and the flow field from an Eulerian one. Secondly, their experiments confirm the earlier theoretical proof by Westervelt (Reference Westervelt1953a

) that the streaming generated by an oscillating cylinder in a quiescent liquid is equivalent to that generated by an oscillating fluid around a stationary cylinder. For the theoretical streaming to satisfy this result, Stokes drift must be included in the calculations in both reference frames. In parallel, Riley (Reference Riley1965) and others put the calculation of streaming using the method of matched asymptotic expansions onto firm ground. Unlike Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954), Riley’s work is generally in the limit of small

![]() $ \delta / {R}$

(with

$ \delta / {R}$

(with

![]() $R$

the cylinder radius), which limits the applicability for low frequencies, but has the advantage of yielding a full analytical solution.

$R$

the cylinder radius), which limits the applicability for low frequencies, but has the advantage of yielding a full analytical solution.

Figure 1. Examples of microstreaming generated around a cylinder undergoing rectilinear oscillations along the horizontal axis. Results are obtained from the model by Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954) for a cylinder of radius

![]() $R=100\,\unicode{x03BC} {\textrm{m}}$

in water (

$R=100\,\unicode{x03BC} {\textrm{m}}$

in water (

![]() $\nu = 10^{-6}\,{\textrm{m}^{2}\, \textrm {s}^{- 1}}$

) and at frequencies

$\nu = 10^{-6}\,{\textrm{m}^{2}\, \textrm {s}^{- 1}}$

) and at frequencies

![]() $f = {0.01}, {0.1}, {1}, {10}, {100}\,\textrm {kHz}$

. The corresponding boundary-layer thicknesses are

$f = {0.01}, {0.1}, {1}, {10}, {100}\,\textrm {kHz}$

. The corresponding boundary-layer thicknesses are

![]() $\delta ={180},{56},{18},{5.6},{1.8}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

. With

$\delta ={180},{56},{18},{5.6},{1.8}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

. With

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $\nu$

fixed, the extent of the inner streaming structure depends only on the frequency. At

$\nu$

fixed, the extent of the inner streaming structure depends only on the frequency. At

![]() ${1}\,\textrm {kHz}$

, both the streaming structure within the boundary layer and the outer streaming are visible. At lower frequencies, only the boundary-layer streaming is visible in the field of view, leading to inflow at the poles on the

${1}\,\textrm {kHz}$

, both the streaming structure within the boundary layer and the outer streaming are visible. At lower frequencies, only the boundary-layer streaming is visible in the field of view, leading to inflow at the poles on the

![]() $x$

-axis, whereas at higher frequencies, the outer streaming dominates, resulting in outflow visible at the poles on the

$x$

-axis, whereas at higher frequencies, the outer streaming dominates, resulting in outflow visible at the poles on the

![]() $x$

-axis.

$x$

-axis.

While, in the past century, the study of streaming around rectilinearly oscillating cylinders was largely driven by scientific curiosity, it has now become of fundamental interest for practical applications, particularly in microfluidics, for instance in mixing and in the trapping of particles or cells (Lutz, Chen & Schwartz Reference Lutz, Chen and Schwartz2006; Lieu, House & Schwartz Reference Lieu, House and Schwartz2012; Chong et al. Reference Chong, Kelly, Smith and Eldredge2013; House, Lieu & Schwartz Reference House, Lieu and Schwartz2014; Orbay et al. Reference Orbay, Ozcelik, Bachman and Huang2018; Parthasarathy, Chan & Gazzola Reference Parthasarathy, Chan and Gazzola2019). More recently, circular streaming induced by circularly oscillating cylinders has also found applications, such as transporting cells along predefined paths (Hayakawa et al. Reference Hayakawa, Sakuma, Fukuhara, Yokoyama and Arai2014, Reference Hayakawa, Sakuma and Arai2015; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Zhou, Cai, Meng, Zheng and Ai2020).

Theoretically, the problem of circular cylinder motion inducing circular streaming flow was first addressed by Riley (Reference Riley1971), based in part on the work of Longuet-Higgins (Reference Longuet-Higgins1970). In particular, they predicted that no flow reversal between the inner and outer streaming regions, characteristic of rectilinear oscillations (as seen, for example, in figure 1,

![]() $f={1}\,\textrm {kHz}$

), would occur. Riley (Reference Riley1992) further developed this theory to account for elliptical motion of the cylinder, with the intent to describe high-Reynolds-number outer streaming for oscillation amplitudes larger than the boundary-layer thickness. For purely circular motion, Hayakawa et al. (Reference Hayakawa, Sakuma, Fukuhara, Yokoyama and Arai2014) later attempted an alternative approach by extending the theory of Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954). Their model nevertheless contains several typographical errors in the first-order solution and an incorrect mathematical approach for the second order, underlined and corrected here in the supplementary material.

$f={1}\,\textrm {kHz}$

), would occur. Riley (Reference Riley1992) further developed this theory to account for elliptical motion of the cylinder, with the intent to describe high-Reynolds-number outer streaming for oscillation amplitudes larger than the boundary-layer thickness. For purely circular motion, Hayakawa et al. (Reference Hayakawa, Sakuma, Fukuhara, Yokoyama and Arai2014) later attempted an alternative approach by extending the theory of Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954). Their model nevertheless contains several typographical errors in the first-order solution and an incorrect mathematical approach for the second order, underlined and corrected here in the supplementary material.

To the best of our knowledge, theories for circular motion have not been confronted with experiments, while both reliable theory and corresponding experiments are missing in the elliptical case. Nevertheless, these oscillation modes are essential to understand in the context of micro-swimmers, as they are naturally observed when a cylindrical tail is attached to a vibrating body.

In the present study, we demonstrate that the microstreaming patterns around a vibrating micro-cantilever (used as a model for a micro-swimmer tail) attached to a vibrating substrate can be extremely diverse. This diversity of streaming patterns arises from the broad variety of motion types of the cantilever, including purely rectilinear motion, purely circular motion and various forms of elliptical motion. These results are confronted with a newly developed semi-analytical 2-D model inspired by the original work of Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954). Unlike previous work, we consider a moving cylinder in a quiescent liquid, not vice versa, and include general elliptical motion, not just rectilinear motion. We evaluate this 2-D model numerically and obtain good agreement with the experiments.

The manuscript is organised as follows. In § 2, we introduce the experimental device, the experimental procedures for microstreaming observations and the measurement of cantilever motion via laser Doppler vibrometry, including the post-processing procedure. The elliptical nature of the recovered cantilever motion emphasises the need for an adequate semi-analytical model, which is derived in § 3. In § 4, we first present the range of cantilever motions obtained, followed by the experimental streaming results and their comparison with the 2-D model. In most of the section, we assume the streaming to be dominantly two-dimensional, but we conclude by discussing the 3-D effects observed, mainly towards the tip of the cantilever. Finally, the manuscript is wrapped up with general conclusions in § 5.

2. Experimental approach

Our experimental device, shown in figure 2 and described in detail in § 2.1, consists of a microscope glass slide excited by a piezoelectric transducer. The aim of this study is to understand the vibrations and the resulting streaming flows of a micro-cantilever attached to the glass slide in the region of interest (ROI). To this end, the experimental procedure follows three steps, (i) the fabrication of the micro-cantilever, described in § 2.2; (ii) the study of the 2-D and 3-D microstreaming, detailed in § 2.3; and (iii) the study of the 3-D micro-cantilever oscillations, presented in § 2.4. The post-processing of the micro-cantilever motion is relatively involved and is explained in detail in § 2.5.

Figure 2. Experimental device and procedures. (a) The experimental device consists of a microscope glass slide to which a piezoelectric transducer was glued. The custom holder (with Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) pads for decoupling vibrations from the device) can be mounted on a microscope and a laser Doppler vibrometer. The cantilever was situated in the ROI, which corresponds to the inner wall of the footprint of the PDMS chamber(s). (b) The cantilever was fabricated by filling a PDMS chamber roughly

![]() ${600}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

high with PEG-DA and subsequently illuminating it with a circular beam of UV light for polymerisation. (c) Microstreaming experiments are conducted in a

${600}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

high with PEG-DA and subsequently illuminating it with a circular beam of UV light for polymerisation. (c) Microstreaming experiments are conducted in a

![]() ${3}\,\textrm {mm}$

-high PDMS chamber filled with water containing tracer particles. (d) Laser doppler vibrometry (LDV) was used to measure the vibrations and displacements of the micro-cantilever in air. A single scan in the

${3}\,\textrm {mm}$

-high PDMS chamber filled with water containing tracer particles. (d) Laser doppler vibrometry (LDV) was used to measure the vibrations and displacements of the micro-cantilever in air. A single scan in the

![]() $z$

-direction provides the 1-D profile in that specific direction. To obtain the full 2-D motion, scans along four axes are used. (e) Post-processing enables correlation of the respective micro-cantilever motion with the induced microstreaming patterns. (Schematics not to scale.)

$z$

-direction provides the 1-D profile in that specific direction. To obtain the full 2-D motion, scans along four axes are used. (e) Post-processing enables correlation of the respective micro-cantilever motion with the induced microstreaming patterns. (Schematics not to scale.)

2.1. Preparation of the experimental device

To fabricate the experimental device sketched in figure 2(a), a microscope glass slide (

![]() $76 \times 26 \times {1}\,\textrm {mm}$

, Fisher Scientific) was cleaned in an ultrasound bath, first in acetone, then in isopropanol. It was subsequently oxidised with

$76 \times 26 \times {1}\,\textrm {mm}$

, Fisher Scientific) was cleaned in an ultrasound bath, first in acetone, then in isopropanol. It was subsequently oxidised with

![]() $\mathrm{O_2}$

plasma for two minutes at

$\mathrm{O_2}$

plasma for two minutes at

![]() ${200}\,\textrm {W}$

to provide a dense layer of reactive silanol groups (

${200}\,\textrm {W}$

to provide a dense layer of reactive silanol groups (

![]() ${\equiv}\textrm {Si}{-}\textrm {OH}$

), which serve as anchoring sites for the adhesion coating. To increase adhesion of the micro-cantilever to the glass surface, we used an organosilane bearing a methacrylate function (3-(Trimethoxysilyl) propyl methacrylate, 98 %, in short TMSPM, Sigma Aldrich). By the technique of self-assembled monolayers, these molecules spontaneously react with the silanol groups on the glass surface, forming a densely packed molecular film (Schreiber Reference Schreiber2000; Onclin, Ravoo & Reinhoudt Reference Onclin, Ravoo and Reinhoudt2005; Aswal et al. Reference Aswal, Lenfant, Guérin, Yakhmi and Vuillaume2006; Ulman Reference Ulman2013). To this end, the freshly cleaned glass substrates were immersed for two hours in a solution of

${\equiv}\textrm {Si}{-}\textrm {OH}$

), which serve as anchoring sites for the adhesion coating. To increase adhesion of the micro-cantilever to the glass surface, we used an organosilane bearing a methacrylate function (3-(Trimethoxysilyl) propyl methacrylate, 98 %, in short TMSPM, Sigma Aldrich). By the technique of self-assembled monolayers, these molecules spontaneously react with the silanol groups on the glass surface, forming a densely packed molecular film (Schreiber Reference Schreiber2000; Onclin, Ravoo & Reinhoudt Reference Onclin, Ravoo and Reinhoudt2005; Aswal et al. Reference Aswal, Lenfant, Guérin, Yakhmi and Vuillaume2006; Ulman Reference Ulman2013). To this end, the freshly cleaned glass substrates were immersed for two hours in a solution of

![]() ${100}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm {l}}$

TMSPM and

${100}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm {l}}$

TMSPM and

![]() ${100}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm {l}}$

acetic acid (Sigma Aldrich) in

${100}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm {l}}$

acetic acid (Sigma Aldrich) in

![]() ${20}\,\textrm {ml}$

toluene (99.8 %, Sigma Aldrich). Finally, the glass slides were thoroughly cleaned in isopropanol, then in dichloromethane by sonication (3 min) and lastly blown dry with nitrogen. The resulting adhesion layer is suitable for promoting covalent bonds with the poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEG-DA) used for the micro-cantilevers during UV crosslinking.

${20}\,\textrm {ml}$

toluene (99.8 %, Sigma Aldrich). Finally, the glass slides were thoroughly cleaned in isopropanol, then in dichloromethane by sonication (3 min) and lastly blown dry with nitrogen. The resulting adhesion layer is suitable for promoting covalent bonds with the poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEG-DA) used for the micro-cantilevers during UV crosslinking.

Next, a piezoelectric transducer (RS 724-3162, resonance frequency

![]() ${4.2}\,\textrm {kHz}$

) was glued onto the glass slide. Finally, the device was placed in a custom support made of two pieces of Plexiglass held together by two screws. The PDMS pads between the device and the support were used to decouple the device from the holder and prevent vibrations from being transmitted from one to the other. The support could be mounted either on the microscope or the laser Doppler vibrometer without altering the boundary conditions or the resulting constraints on the device.

${4.2}\,\textrm {kHz}$

) was glued onto the glass slide. Finally, the device was placed in a custom support made of two pieces of Plexiglass held together by two screws. The PDMS pads between the device and the support were used to decouple the device from the holder and prevent vibrations from being transmitted from one to the other. The support could be mounted either on the microscope or the laser Doppler vibrometer without altering the boundary conditions or the resulting constraints on the device.

2.2. Fabrication of the micro-cantilever

For the micro-cantilever fabrication (see sketch in figure 2

b), the device was mounted on an optical microscope (Nikon Ti2E) equipped with a UV photopatterning system (Alveole Primo). A PDMS chamber (

![]() ${5}\,\textrm {mm}\times {7}\,\textrm {mm}$

in inner area and approximately

${5}\,\textrm {mm}\times {7}\,\textrm {mm}$

in inner area and approximately

![]() ${600}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

in height) was placed in the region of interest and filled with a polymer solution of PEG-DA with an average molecular mass

${600}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

in height) was placed in the region of interest and filled with a polymer solution of PEG-DA with an average molecular mass

![]() $M_n = 250$

, mixed with 12 % (w/w) photo-initiator 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone, as inspired by Orbay et al. (Reference Orbay, Ozcelik, Bachman and Huang2018). A pulse of UV light (

$M_n = 250$

, mixed with 12 % (w/w) photo-initiator 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone, as inspired by Orbay et al. (Reference Orbay, Ozcelik, Bachman and Huang2018). A pulse of UV light (

![]() ${5}\,{\textrm {mJ}\,\textrm {mm}^{- 2}}$

) was projected through a numerical mask (circular shape, 200 pixels in diameter) of the photopatterning system and a

${5}\,{\textrm {mJ}\,\textrm {mm}^{- 2}}$

) was projected through a numerical mask (circular shape, 200 pixels in diameter) of the photopatterning system and a

![]() $20\times$

objective to polymerise the PEG-DA solution within the resulting cylindrical light beam. While the silanised glass slide favours adhesion of the polymerising PEG-DA to the device, a so-called oxygen inhibition layer prevents the PEG-DA from polymerising near the PDMS chamber walls (Dendukuri et al. Reference Dendukuri, Pregibon, Collins, Hatton and Doyle2006). This procedure results in the fabrication of a micro-cantilever approximately

$20\times$

objective to polymerise the PEG-DA solution within the resulting cylindrical light beam. While the silanised glass slide favours adhesion of the polymerising PEG-DA to the device, a so-called oxygen inhibition layer prevents the PEG-DA from polymerising near the PDMS chamber walls (Dendukuri et al. Reference Dendukuri, Pregibon, Collins, Hatton and Doyle2006). This procedure results in the fabrication of a micro-cantilever approximately

![]() ${590}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

high and

${590}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

high and

![]() ${40}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

in diameter.

${40}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

in diameter.

Care was taken to fabricate the cantilever within a few days after silanising the glass slides, to optimise the adherence of the cantilevers to the device. Immediately after polymerisation, the PDMS chamber was removed, and the region of interest was washed with isopropanol.

2.3. Microstreaming observations

To observe the microstreaming, the device was mounted on the microscope, as shown in the schematic in figure 2(c). A

![]() ${3}\,\textrm {mm}$

high PDMS chamber was placed in the region of interest and filled with water containing

${3}\,\textrm {mm}$

high PDMS chamber was placed in the region of interest and filled with water containing

![]() ${1}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

tracer particles (red fluorescent polymer microspheres, Duke Scientific). Following the estimations by Barnkob et al. (Reference Barnkob, Augustsson, Laurell and Bruus2012), these particles are sufficiently small to follow the streaming flow, as the influence of radiation forces on their behaviour is negligible. The piezoelectric transducer was connected to a function generator (Tektronix AFG 3102) set to a voltage between

${1}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

tracer particles (red fluorescent polymer microspheres, Duke Scientific). Following the estimations by Barnkob et al. (Reference Barnkob, Augustsson, Laurell and Bruus2012), these particles are sufficiently small to follow the streaming flow, as the influence of radiation forces on their behaviour is negligible. The piezoelectric transducer was connected to a function generator (Tektronix AFG 3102) set to a voltage between

![]() ${1}\,\textrm {}$

and

${1}\,\textrm {}$

and

![]() ${5}\,\textrm {Vpp}$

, and operated at different frequencies ranging from

${5}\,\textrm {Vpp}$

, and operated at different frequencies ranging from

![]() ${30}\,\textrm {}$

to

${30}\,\textrm {}$

to

![]() ${300}\,\textrm {kHz}$

. Two different imaging modes were used.

${300}\,\textrm {kHz}$

. Two different imaging modes were used.

The first imaging mode was used for the qualitative visualisation of the microstreaming patterns in 2-D

![]() $xy$

-planes parallel to the glass support and perpendicular to the axis of the micro-cantilever. Imaging was ensured with microscope backlighting, a

$xy$

-planes parallel to the glass support and perpendicular to the axis of the micro-cantilever. Imaging was ensured with microscope backlighting, a

![]() $20\times$

objective and a high-resolution, high-sensitivity camera (Prime BSI) mounted on the microscope. The camera was operated at a frame rate of

$20\times$

objective and a high-resolution, high-sensitivity camera (Prime BSI) mounted on the microscope. The camera was operated at a frame rate of

![]() ${11.8}\,\textrm {fps}$

and controlled via a custom Python script, which directly processed the images. To shorten the duration of the experiments and save memory, the script only stored a superposition of 1000 snapshots, which allows the visualisation of the entire streaming pattern via the ensemble of all the individual tracer particle trajectories. Such images were recorded for different frequencies and at different heights of the micro-cantilever. Three examples are reproduced in figure 3(a). Note that particles up to approximately

${11.8}\,\textrm {fps}$

and controlled via a custom Python script, which directly processed the images. To shorten the duration of the experiments and save memory, the script only stored a superposition of 1000 snapshots, which allows the visualisation of the entire streaming pattern via the ensemble of all the individual tracer particle trajectories. Such images were recorded for different frequencies and at different heights of the micro-cantilever. Three examples are reproduced in figure 3(a). Note that particles up to approximately

![]() ${40}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

above or below the focal plane are blurry but visible in the recording. Each recorded image thus corresponds to an ensemble of trajectories over approximately

${40}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

above or below the focal plane are blurry but visible in the recording. Each recorded image thus corresponds to an ensemble of trajectories over approximately

![]() ${80}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

in height. For all experiments conducted with this imaging mode, the voltage of the transducer was set to

${80}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

in height. For all experiments conducted with this imaging mode, the voltage of the transducer was set to

![]() ${5}\,\textrm {Vpp}$

, as this led to the best image quality.

${5}\,\textrm {Vpp}$

, as this led to the best image quality.

Figure 3. (a) Typical examples of 2-D microstreaming observations. The plots result from a superposition of 1000 snaps hots recorded at a frame rate of

![]() ${11.8}\,\textrm {fps}$

. Images are downsampled and contrast-enhanced for a reasonable file size of the manuscript. (b) Three-dimensional tracer particle trajectories (one colour per particle) obtained with the cylindrical lens set-up. The black arrows indicate the flow direction.

${11.8}\,\textrm {fps}$

. Images are downsampled and contrast-enhanced for a reasonable file size of the manuscript. (b) Three-dimensional tracer particle trajectories (one colour per particle) obtained with the cylindrical lens set-up. The black arrows indicate the flow direction.

The second imaging method was used for a quantitative study of the 3-D streaming around the micro-cantilever. To that end, astigmatic imaging with a cylindrical lens, as proposed by Cierpka et al. (Reference Cierpka, Segura, Hain and Kähler2010), was implemented. A camera (IDS U3-3060 CP Rev.2.2), operated at a frame rate of

![]() ${5}\,\textrm{fps}$

, was mounted onto the microscope via a camera port adapter (SML20/SM1A44/SM1A39, Thorlabs) containing a cylindrical lens with a focal length of

${5}\,\textrm{fps}$

, was mounted onto the microscope via a camera port adapter (SML20/SM1A44/SM1A39, Thorlabs) containing a cylindrical lens with a focal length of

![]() ${150}\,\textrm {mm}$

(LJ1629RM, Thorlabs). Consequently, two focal planes separated by

${150}\,\textrm {mm}$

(LJ1629RM, Thorlabs). Consequently, two focal planes separated by

![]() ${40}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

were created, one for the

${40}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

were created, one for the

![]() $x$

- and one for the

$x$

- and one for the

![]() $y$

-direction. The shape of the particle in the recording changes according to its

$y$

-direction. The shape of the particle in the recording changes according to its

![]() $z$

-position relative to these focal planes. Image processing was carried out using DefocusTracker Version 2.0.0 (Rossi & Barnkob Reference Rossi and Barnkob2020; Barnkob & Rossi Reference Barnkob and Rossi2021), which enabled full reconstruction of the 3-D position of each individual particle at every moment in time. During a single recording, particles could only be detected over a height range of approximately

$z$

-position relative to these focal planes. Image processing was carried out using DefocusTracker Version 2.0.0 (Rossi & Barnkob Reference Rossi and Barnkob2020; Barnkob & Rossi Reference Barnkob and Rossi2021), which enabled full reconstruction of the 3-D position of each individual particle at every moment in time. During a single recording, particles could only be detected over a height range of approximately

![]() ${140}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

, which is considerably less than the total height of the cantilever. Consequently, data were acquired at several

${140}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

, which is considerably less than the total height of the cantilever. Consequently, data were acquired at several

![]() $z$

-planes, spaced by

$z$

-planes, spaced by

![]() ${65}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

, to cover the entire height of the micro-cantilever and beyond, thereby obtaining a complete 3-D image of the streaming field. Due to the long total acquisition time, such detailed analysis was only conducted for a very limited number of frequencies. Here, we present results for vibrations at

${65}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

, to cover the entire height of the micro-cantilever and beyond, thereby obtaining a complete 3-D image of the streaming field. Due to the long total acquisition time, such detailed analysis was only conducted for a very limited number of frequencies. Here, we present results for vibrations at

![]() ${102.5}\,\textrm {kHz}$

, where more than 100 000 velocity vectors in a volume of

${102.5}\,\textrm {kHz}$

, where more than 100 000 velocity vectors in a volume of

![]() ${700}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}\times {700}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}} \times {900}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

around the cantilever were obtained. The corresponding trajectories are shown in figure 3(b). The voltage used in this experiment was set to

${700}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}\times {700}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}} \times {900}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

around the cantilever were obtained. The corresponding trajectories are shown in figure 3(b). The voltage used in this experiment was set to

![]() ${3}\,\textrm {Vpp}$

to optimise the particle displacement between consecutive frames.

${3}\,\textrm {Vpp}$

to optimise the particle displacement between consecutive frames.

Throughout the subsequent analysis of the microstreaming data, a refractive index of 1.3 was used to correct the

![]() $z$

-positions in both 2-D and 3-D recordings. For example, if the microscope objective was initially focused on the top of the glass support and then moved upward by

$z$

-positions in both 2-D and 3-D recordings. For example, if the microscope objective was initially focused on the top of the glass support and then moved upward by

![]() ${50}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

, the corresponding image plane would be located at an actual height of

${50}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

, the corresponding image plane would be located at an actual height of

![]() ${65}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

in the liquid.

${65}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

in the liquid.

2.4. Measurement of the micro-cantilever oscillations

Measurements of the micro-cantilever vibrations were carried out using laser Doppler vibrometry (Polytec PSV-500, equipped with a

![]() $10\times$

objective). To this end, the device was positioned so that the micro-cantilever axis was perpendicular to the laser beam (see left schematic in figure 2

d). During the measurement, the piezoelectric transducer was excited by

$10\times$

objective). To this end, the device was positioned so that the micro-cantilever axis was perpendicular to the laser beam (see left schematic in figure 2

d). During the measurement, the piezoelectric transducer was excited by

![]() ${128}\,\textrm {ms}$

-long sweeps from

${128}\,\textrm {ms}$

-long sweeps from

![]() ${2}\,\textrm {}$

to

${2}\,\textrm {}$

to

![]() ${300}\,\textrm {kHz}$

at a voltage of

${300}\,\textrm {kHz}$

at a voltage of

![]() ${0.5}\,\textrm {Vpp}$

. The response of the cantilever was recorded using a velocity decoder and the corresponding frequency spectrum obtained via the vibrometer-internal software. Its noise level was reduced by averaging the amplitude and phase (relative to the excitation phase) over 25 sweeps before storing them. Note that, in order to work with vibration amplitudes consistent with those used in the streaming experiments, all data presented in this manuscript have been corrected by a calibration factor of 1000 relative to the raw amplitudes obtained from the frequency sweep of the vibrometer. A detailed justification of this procedure is provided in Appendix B. In brief, it accounts for (i) the vibration amplitude induced by the sweep being much lower than that induced by a pure sine signal at the same voltage, and (ii) the voltages used in the streaming experiments being higher than those applied during the vibration measurements. Furthermore, the amplitudes in water differ from those measured in air. However, as this relationship is far from straightforward, it is not included in the calibration factor but will be addressed separately in § 4.1, and § 4.3.

${0.5}\,\textrm {Vpp}$

. The response of the cantilever was recorded using a velocity decoder and the corresponding frequency spectrum obtained via the vibrometer-internal software. Its noise level was reduced by averaging the amplitude and phase (relative to the excitation phase) over 25 sweeps before storing them. Note that, in order to work with vibration amplitudes consistent with those used in the streaming experiments, all data presented in this manuscript have been corrected by a calibration factor of 1000 relative to the raw amplitudes obtained from the frequency sweep of the vibrometer. A detailed justification of this procedure is provided in Appendix B. In brief, it accounts for (i) the vibration amplitude induced by the sweep being much lower than that induced by a pure sine signal at the same voltage, and (ii) the voltages used in the streaming experiments being higher than those applied during the vibration measurements. Furthermore, the amplitudes in water differ from those measured in air. However, as this relationship is far from straightforward, it is not included in the calibration factor but will be addressed separately in § 4.1, and § 4.3.

A single scan consisted of up to sixty measurement points along the axis of the cantilever. It should be noted that no surface coating is necessary to achieve the measurements, however, the surface of the vibrating object must be (close to) perfectly perpendicular to the incoming laser beam, as otherwise, the reflected beam would not be detected by the vibrometer. This requirement poses a significant challenge for the rounded surface of the cantilever. Consequently, each scan inevitably contained some erroneous points, which were manually discarded when the noise level exceeded

![]() ${1.5}\,\textrm {nm}$

. To increase both the reliability and the quantity of our data, the same procedure was therefore repeated up to four times, each time with a slight readjustment of the micro-cantilever’s position relative to the vibrometer head.

${1.5}\,\textrm {nm}$

. To increase both the reliability and the quantity of our data, the same procedure was therefore repeated up to four times, each time with a slight readjustment of the micro-cantilever’s position relative to the vibrometer head.

The procedure described above allows for the recovery of the 1-D motion of multiple points. For example, the schematic on the left of figure 2(d) illustrates the measurement of vibrations in the

![]() $y$

-direction. Naturally, each segment of the cantilever generally undergoes a 2-D motion in the

$y$

-direction. Naturally, each segment of the cantilever generally undergoes a 2-D motion in the

![]() $xy$

-plane (we consider the

$xy$

-plane (we consider the

![]() $z$

-position to be constant), and we shall see that this motion can be described by an ellipse. To reconstruct this elliptical 2-D motion, separate scans along four different axes were conducted, as shown on the right side of figure 2(d). In theory, it is sufficient to correlate the amplitudes and phases of two different scan directions to reconstruct the full motion of the cantilever. However, using a larger number of scans increases the overall robustness and accuracy of the results. The precise post-processing procedure will be discussed in § 2.5.

$z$

-position to be constant), and we shall see that this motion can be described by an ellipse. To reconstruct this elliptical 2-D motion, separate scans along four different axes were conducted, as shown on the right side of figure 2(d). In theory, it is sufficient to correlate the amplitudes and phases of two different scan directions to reconstruct the full motion of the cantilever. However, using a larger number of scans increases the overall robustness and accuracy of the results. The precise post-processing procedure will be discussed in § 2.5.

Additionally, we measured the vibrations of the glass support, once again without special surface coating, in the vicinity of the cantilever to serve as a reference. Naturally, this only provides access to the

![]() $z$

-component (the only component we could not measure for the cantilever itself), but it still allows for a comparison of the frequencies corresponding to the vibration maxima between the support and the cantilever.

$z$

-component (the only component we could not measure for the cantilever itself), but it still allows for a comparison of the frequencies corresponding to the vibration maxima between the support and the cantilever.

2.5. Post-processing procedure for recovering the micro-cantilever motion

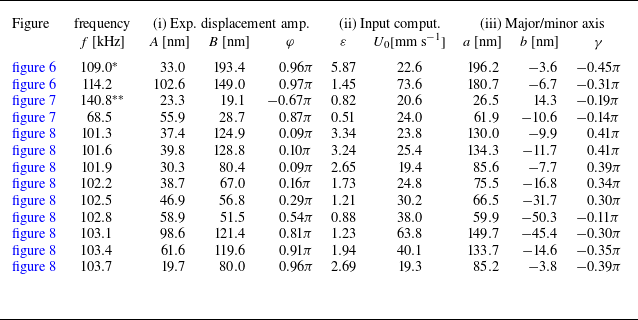

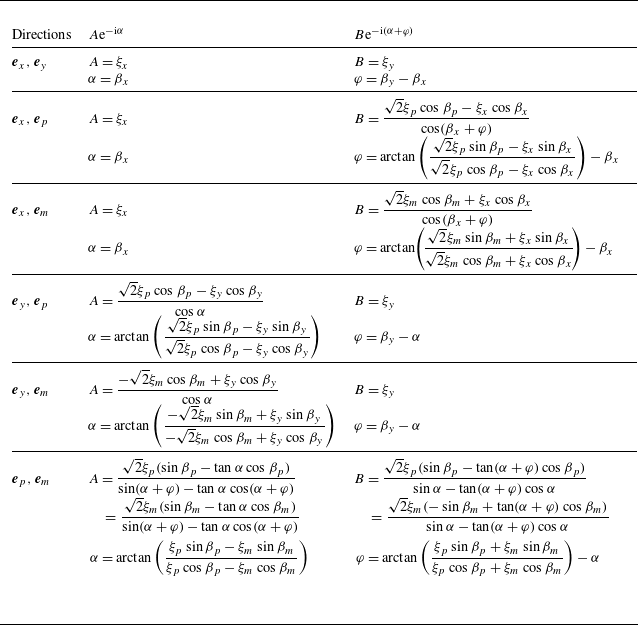

Figure 4. Reconstruction of the micro-cantilever motion at

![]() ${102.8}\,\textrm {kHz}$

. (a) Schematic of the cantilever and the four scanning directions. A full scan along the entire cantilever is illustrated for the

${102.8}\,\textrm {kHz}$

. (a) Schematic of the cantilever and the four scanning directions. A full scan along the entire cantilever is illustrated for the

![]() $x$

-direction. (b) Resulting raw amplitudes

$x$

-direction. (b) Resulting raw amplitudes

![]() $\xi _i$

and phases

$\xi _i$

and phases

![]() $\beta _i$

(with

$\beta _i$

(with

![]() $i = x, y, p, m$

) for each scan, using the same colour code as in panel (a). (c) Schematic of the elliptical motion of a single segment

$i = x, y, p, m$

) for each scan, using the same colour code as in panel (a). (c) Schematic of the elliptical motion of a single segment

![]() $z_j$

, with the raw amplitudes

$z_j$

, with the raw amplitudes

![]() $\xi _i$

, and the final amplitudes

$\xi _i$

, and the final amplitudes

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() $B$

. The major axis

$B$

. The major axis

![]() $a$

and the minor axis

$a$

and the minor axis

![]() $b$

are also indicated. (d) Results for

$b$

are also indicated. (d) Results for

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() $B$

and their respective phases

$B$

and their respective phases

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $\varphi$

, obtained from different pairs shown in panel (b). The black and red lines correspond to the averaged values, only the red part is used for the final reconstruction. (e) Final reconstruction: major axis as a function of

$\varphi$

, obtained from different pairs shown in panel (b). The black and red lines correspond to the averaged values, only the red part is used for the final reconstruction. (e) Final reconstruction: major axis as a function of

![]() $z$

(left), 3-D representation of the motion over time (centre) and motion of three segments in the

$z$

(left), 3-D representation of the motion over time (centre) and motion of three segments in the

![]() $xy$

-plane (right). The three coloured points are the same in each panel.

$xy$

-plane (right). The three coloured points are the same in each panel.

The full reconstruction of the cantilever motion from the vibrometer data is achieved through several post-processing steps, as outlined below. To simplify the explanations, the discussion will be focused on the frequency of

![]() ${102.8}\,\textrm {kHz}$

, but the automated procedure can be applied to any frequency of interest, provided that the vibration amplitudes are large enough to yield relevant results.

${102.8}\,\textrm {kHz}$

, but the automated procedure can be applied to any frequency of interest, provided that the vibration amplitudes are large enough to yield relevant results.

-

(i) For all data points, we extract the complex amplitudes

$\xi _i \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \beta _i}$

, where

$\xi _i \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \beta _i}$

, where

$\xi _i$

is the real-valued amplitude and

$\xi _i$

is the real-valued amplitude and

$\beta _i$

the phase. The index

$\beta _i$

the phase. The index

$i$

corresponds to the different directions

$i$

corresponds to the different directions

$\boldsymbol{e}_x$

,

$\boldsymbol{e}_x$

,

$\boldsymbol{e}_y$

,

$\boldsymbol{e}_y$

,

$\boldsymbol{e}_m$

and

$\boldsymbol{e}_m$

and

$\boldsymbol{e}_p$

, as indicated in figure 4(a). The results for

$\boldsymbol{e}_p$

, as indicated in figure 4(a). The results for

${102.8}\,\textrm {kHz}$

are shown in figure 4(b). Specifically, the results of twelve scans (two to four per direction) are plotted. Each scan is processed independently of the others in the same direction, as this proved to yield more robust results than averaging at this stage. For the example shown in figure 4(b), the amplitudes for the four scan directions follow a similar trend, and the displacement node around

${102.8}\,\textrm {kHz}$

are shown in figure 4(b). Specifically, the results of twelve scans (two to four per direction) are plotted. Each scan is processed independently of the others in the same direction, as this proved to yield more robust results than averaging at this stage. For the example shown in figure 4(b), the amplitudes for the four scan directions follow a similar trend, and the displacement node around

${500}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

coincides with a phase shift of

${500}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

coincides with a phase shift of

$\pi$

, as expected.

$\pi$

, as expected. -

(ii) Initially, the

$z$

-coordinates of the data points do not necessarily coincide between different scans, so that we interpolate the amplitudes and phases onto 40 segments

$z$

-coordinates of the data points do not necessarily coincide between different scans, so that we interpolate the amplitudes and phases onto 40 segments

$z_j$

along the cantilever axis (not shown in the figure). This step is necessary for the subsequent reconstruction.

$z_j$

along the cantilever axis (not shown in the figure). This step is necessary for the subsequent reconstruction. -

(iii) For each interpolation segment

$z_j$

, we thus obtain several sets of data. Each pair of measurements, for example

$z_j$

, we thus obtain several sets of data. Each pair of measurements, for example

$\xi _p(z_j)\mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i}\beta _p(z_j)}$

together with

$\xi _p(z_j)\mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i}\beta _p(z_j)}$

together with

$\xi _m(z_j)\mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i}\beta _m(z_j)}$

, is sufficient to describe the elliptical motion of the segment

$\xi _m(z_j)\mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i}\beta _m(z_j)}$

, is sufficient to describe the elliptical motion of the segment

$z_j$

. Consequently, each pair allows for the reconstruction of the complex amplitudes

$z_j$

. Consequently, each pair allows for the reconstruction of the complex amplitudes

$A(z_j)\mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i}\alpha (z_j)}$

and

$A(z_j)\mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i}\alpha (z_j)}$

and

$B(z_j)\mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i}(\alpha (z_j)+\varphi (z_j))}$

along the

$B(z_j)\mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i}(\alpha (z_j)+\varphi (z_j))}$

along the

$\boldsymbol{e}_x$

and

$\boldsymbol{e}_x$

and

$\boldsymbol{e}_y$

directions, respectively, as illustrated in figure 4(b). Here,

$\boldsymbol{e}_y$

directions, respectively, as illustrated in figure 4(b). Here,

$A$

and

$A$

and

$B$

are the respective real-valued amplitudes, and

$B$

are the respective real-valued amplitudes, and

$\varphi$

is the relative phase between the two. The phase

$\varphi$

is the relative phase between the two. The phase

$\alpha$

has no importance for defining the elliptical trajectory, but provides insight into the relative phase of different elements

$\alpha$

has no importance for defining the elliptical trajectory, but provides insight into the relative phase of different elements

$z_j$

, such as the

$z_j$

, such as the

$\pi$

phase shifts corresponding to the amplitude nodes. The full set of equations used for reconstructing the motion from any combination of scan directions is provided in Appendix A. The resulting amplitudes for

$\pi$

phase shifts corresponding to the amplitude nodes. The full set of equations used for reconstructing the motion from any combination of scan directions is provided in Appendix A. The resulting amplitudes for

${102.8}\,\textrm {kHz}$

are shown as dots in figure 4(d).

${102.8}\,\textrm {kHz}$

are shown as dots in figure 4(d). -

(iv) All results for

$A(z_j)$

,

$A(z_j)$

,

$\alpha (z_j)$

,

$\alpha (z_j)$

,

$B(z_j)$

and

$B(z_j)$

and

$\varphi (z_j)$

are averaged to obtain a single representative value for each segment

$\varphi (z_j)$

are averaged to obtain a single representative value for each segment

$z_j$

, as shown by the black line in figure 4(d). More precisely, we compute the median, which (combined with the use of independently processed scans along the same direction as explained in step (i)) provides the best robustness against inevitable outliers arising from the experimental difficulties. In the following steps, we exclude data points where the total vibration amplitude is too low (i.e. below approximately

$z_j$

, as shown by the black line in figure 4(d). More precisely, we compute the median, which (combined with the use of independently processed scans along the same direction as explained in step (i)) provides the best robustness against inevitable outliers arising from the experimental difficulties. In the following steps, we exclude data points where the total vibration amplitude is too low (i.e. below approximately

${7}\,\textrm {nm}$

, corresponding to five times the accepted noise level), as such points are subject to too large error on the phase. As could already be expected from the raw results, the reconstructed real amplitudes

${7}\,\textrm {nm}$

, corresponding to five times the accepted noise level), as such points are subject to too large error on the phase. As could already be expected from the raw results, the reconstructed real amplitudes

$A$

and

$A$

and

$B$

for

$B$

for

${102.8}\,\textrm {kHz}$

are of similar magnitude, and the phase shift observed in each

${102.8}\,\textrm {kHz}$

are of similar magnitude, and the phase shift observed in each

$\xi _i$

naturally reappears in

$\xi _i$

naturally reappears in

$\alpha$

. Importantly,

$\alpha$

. Importantly,

$\varphi$

is approximately

$\varphi$

is approximately

$\pi /2$

, which results in the motion being close to circular rather than purely rectinilear.

$\pi /2$

, which results in the motion being close to circular rather than purely rectinilear. -

(v) After interpolating or extrapolating missing points, the full motion of the cantilever can be reconstructed, see figure 4(e). The grey lines in the centre plot of figure 4(e) show the elliptical trajectories of each segment

$z_j$

. The three differently coloured ellipses are plotted again in the right plot of figure 4(e) The left panel of figure 4(e) shows a side view of the deformed cantilever, or more precisely, the major axis

$z_j$

. The three differently coloured ellipses are plotted again in the right plot of figure 4(e) The left panel of figure 4(e) shows a side view of the deformed cantilever, or more precisely, the major axis

$a$

.

$a$

.

In the following, we will limit the representation of the cantilever motion to the two 2-D representations of figure 4(e), namely (I) the major axis

![]() $a$

as a function of

$a$

as a function of

![]() $z$

, and (II) the elliptical trajectory of a single segment

$z$

, and (II) the elliptical trajectory of a single segment

![]() $z_j$

. These two representations fully describe the motion of the cantilever (apart from the offset

$z_j$

. These two representations fully describe the motion of the cantilever (apart from the offset

![]() $\alpha$

, which is of no interest here), because all of the ellipses are self-similar within the limits of measurement uncertainty. Indeed, this self-similarity, confirmed by the 3-D representation in figure 4(e) (centre), as well as by the roughly constant ratio

$\alpha$

, which is of no interest here), because all of the ellipses are self-similar within the limits of measurement uncertainty. Indeed, this self-similarity, confirmed by the 3-D representation in figure 4(e) (centre), as well as by the roughly constant ratio

![]() $B/A$

and phase

$B/A$

and phase

![]() $\varphi$

over

$\varphi$

over

![]() $z$

, is a general feature observed at all frequencies, and not specific to the example shown here.

$z$

, is a general feature observed at all frequencies, and not specific to the example shown here.

3. Semi-analytical model of microstreaming

The motion of the micro-cantilever discussed in § 2.5 induces microstreaming in the vicinity of the cantilever when operated in water, as already shown in figure 3. In § 4, we present and discuss the experimental streaming results in detail and, for better understanding, compare them with theoretical expectations. To this end, this section is devoted to developing a semi-analytical 2-D model of the streaming induced by a circular cylinder undergoing elliptical motion in the plane perpendicular to the cylinder axis. A 2-D model is justified because this in-plane motion varies slowly along the length of the cylinder.

Our model builds upon the original work by Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954), who studied the streaming generated by a stationary cylinder in a rectilinearly oscillating fluid. Further inspired by Hayakawa et al. (Reference Hayakawa, Sakuma, Fukuhara, Yokoyama and Arai2014), who used two

![]() $ \pi / 2$

out-of-phase rectilinear oscillations in the

$ \pi / 2$

out-of-phase rectilinear oscillations in the

![]() $ x$

- and

$ x$

- and

![]() $ y$

-directions to describe circular motion, we generalise this description to include any relative phase and magnitude between the two oscillations. The experimental in-plane, time-harmonic micro-cantilever motion is represented by

$ y$

-directions to describe circular motion, we generalise this description to include any relative phase and magnitude between the two oscillations. The experimental in-plane, time-harmonic micro-cantilever motion is represented by

where

![]() $ \omega$

is the angular frequency and

$ \omega$

is the angular frequency and

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() $B$

are real-valued amplitudes. Taking its time derivative, the velocity

$B$

are real-valued amplitudes. Taking its time derivative, the velocity

![]() $ \boldsymbol{U}$

of the cylinder is given by

$ \boldsymbol{U}$

of the cylinder is given by

where

![]() $ U_0 = - \mathrm{i} \omega A$

is the velocity amplitude in the

$ U_0 = - \mathrm{i} \omega A$

is the velocity amplitude in the

![]() $ x$

-direction and

$ x$

-direction and

![]() $ \varepsilon U_0 = - \mathrm{i} \omega B$

the velocity amplitude in the

$ \varepsilon U_0 = - \mathrm{i} \omega B$

the velocity amplitude in the

![]() $ y$

-direction, which have been introduced for conciseness. Furthermore,

$ y$

-direction, which have been introduced for conciseness. Furthermore,

![]() $ \varphi$

represents the relative phase between the two oscillations and

$ \varphi$

represents the relative phase between the two oscillations and

![]() $ \varepsilon = B / A$

the relative amplitude. Purely rectilinear motion is obtained in the

$ \varepsilon = B / A$

the relative amplitude. Purely rectilinear motion is obtained in the

![]() $ x$

-direction for

$ x$

-direction for

![]() $ \varepsilon = 0$

, and purely circular motion is obtained for

$ \varepsilon = 0$

, and purely circular motion is obtained for

![]() $ \varepsilon = 1$

and

$ \varepsilon = 1$

and

![]() $ \varphi = \pm \pi / 2$

. Many of the remaining combinations of

$ \varphi = \pm \pi / 2$

. Many of the remaining combinations of

![]() $ \varepsilon$

and

$ \varepsilon$

and

![]() $ \varphi$

yield elliptical motion. Notably, if

$ \varphi$

yield elliptical motion. Notably, if

![]() $ \varphi = \pi / 2$

, the major and minor axes of the ellipse coincide with the

$ \varphi = \pi / 2$

, the major and minor axes of the ellipse coincide with the

![]() $ x$

- and

$ x$

- and

![]() $ y$

-directions, respectively, and

$ y$

-directions, respectively, and

![]() $ \varepsilon$

is identical to the amplitude of the minor-axis motion with respect to the major-axis amplitude. Although (3.2) does not include purely rectilinear motion in the

$ \varepsilon$

is identical to the amplitude of the minor-axis motion with respect to the major-axis amplitude. Although (3.2) does not include purely rectilinear motion in the

![]() $ y$

-direction, which would correspond

$ y$

-direction, which would correspond

![]() $ \varepsilon \to \infty$

, the situation is equivalent to putting

$ \varepsilon \to \infty$

, the situation is equivalent to putting

![]() $ \varepsilon = 0$

and rotating the coordinate system by

$ \varepsilon = 0$

and rotating the coordinate system by

![]() $ \pi / 2$

.

$ \pi / 2$

.

3.1. Formulation of problem

We represent the micro-cantilever as an infinitely long circular cylinder of radius

![]() $ R$

, prescribed with the velocity

$ R$

, prescribed with the velocity

![]() $ \boldsymbol{U}$

given by (3.2). On account of the smallness of

$ \boldsymbol{U}$

given by (3.2). On account of the smallness of

![]() $ R$

relative to the acoustic wavelength

$ R$

relative to the acoustic wavelength

![]() $ \lambda$

,

$ \lambda$

,

![]() $ {R} / \lambda \sim 0.001$

, the resulting flow around the cylinder is assumed incompressible. Consequently, the Eulerian flow velocity

$ {R} / \lambda \sim 0.001$

, the resulting flow around the cylinder is assumed incompressible. Consequently, the Eulerian flow velocity

![]() $ \boldsymbol{v}$

and vorticity

$ \boldsymbol{v}$

and vorticity

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\omega }$

is related to a 2-D streamfunction

$ \boldsymbol{\omega }$

is related to a 2-D streamfunction

![]() $ \psi (x, y)$

by

$ \psi (x, y)$

by

The velocity

![]() $ \boldsymbol{v}$

and pressure

$ \boldsymbol{v}$

and pressure

![]() $ p$

are governed by the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations

$ p$

are governed by the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations

where

![]() $ \rho _0$

and

$ \rho _0$

and

![]() $ \eta _0$

are the density and dynamic viscosity of the fluid, respectively. Equation (3.4) is adjoined by boundary conditions requiring

$ \eta _0$

are the density and dynamic viscosity of the fluid, respectively. Equation (3.4) is adjoined by boundary conditions requiring

![]() $ \boldsymbol{v}$

to match

$ \boldsymbol{v}$

to match

![]() $ \boldsymbol{U}$

on the surface of the cylinder and to vanish infinitely far away. Expressed in polar coordinates

$ \boldsymbol{U}$

on the surface of the cylinder and to vanish infinitely far away. Expressed in polar coordinates

![]() $ (r, \theta )$

, the conditions are

$ (r, \theta )$

, the conditions are

Taking the curl of (3.4) and using (3.3), the

![]() $ z$

-component of the resulting vorticity equation constitutes an equation for

$ z$

-component of the resulting vorticity equation constitutes an equation for

![]() $ \psi$

$ \psi$

where

![]() $ \nu _0 = \eta _0 / \rho _0$

is the kinematic viscosity.

$ \nu _0 = \eta _0 / \rho _0$

is the kinematic viscosity.

Equation (3.6) is solved under the assumption of small oscillation amplitudes defined as

which is justified by the reasonably small

![]() $ \epsilon \approx 0.005$

found for the typical experimental values

$ \epsilon \approx 0.005$

found for the typical experimental values

![]() $ {R} = {20}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

,

$ {R} = {20}\,{\unicode{x03BC} \textrm{m}}$

,

![]() $ f = {100}\,{\textrm {k}\textrm {Hz}}$

and

$ f = {100}\,{\textrm {k}\textrm {Hz}}$

and

![]() $ U_{0} = {0.06}\,{\textrm{m}\,\textrm {s}^{-1}}$

. The flow fields are written as perturbation expansions up to second order in

$ U_{0} = {0.06}\,{\textrm{m}\,\textrm {s}^{-1}}$

. The flow fields are written as perturbation expansions up to second order in

![]() $ \epsilon$

$ \epsilon$

where the first-order fields describe the linear response of the fluid to the motion of the cylinder, and the second-order fields describe the lowest-order nonlinear response, which includes the experimentally observed steady microstreaming as well as a time-harmonic microstreaming at twice the frequency, which is unresolved in the experiments.

Our problem is similar to that of Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954), but with the modified boundary conditions given in (3.5) and in the frame of reference of an oscillating cylinder in a fluid otherwise at rest. As demonstrated by Westervelt (Reference Westervelt1953a ), the second-order streaming is invariant to a coordinate transformation that renders the cylinder stationary and the fluid oscillating. This evident mathematical similarity between the two situations allows us to solve the problem by following steps similar to those of Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954). While we briefly outline these steps here, more detailed explanations can be found in the earlier work.

3.2. Calculation of the first-order flow fields

To first order, (3.6) is

where

![]() $ k_{{s}}$

and

$ k_{{s}}$

and

![]() $ \delta$

are the shear wavenumber and the viscous boundary-layer thickness. The corresponding boundary conditions are

$ \delta$

are the shear wavenumber and the viscous boundary-layer thickness. The corresponding boundary conditions are

Following Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954), but employing the boundary conditions from (3.10), the first-order streamfunction

![]() $ \psi _{1}$

is obtained as

$ \psi _{1}$

is obtained as

where the following abbreviations have been introduced for convenience:

with

![]() $ H_{n}$

being the cylindrical Hankel function of the first kind and of order

$ H_{n}$

being the cylindrical Hankel function of the first kind and of order

![]() $ n$

. The first-order velocity

$ n$

. The first-order velocity

![]() $ \boldsymbol{v}_1$

is obtained by taking the curl of

$ \boldsymbol{v}_1$

is obtained by taking the curl of

![]() $ \psi _{1} \boldsymbol{e}_z$

, the result being

$ \psi _{1} \boldsymbol{e}_z$

, the result being

\begin{align} v_{1r} & = U_0 ( \cos \theta + \varepsilon \mathrm{e}^{-{\mathrm{i}} \varphi } \sin \theta ) \left [ {X_{{s}} + Z_{{s}} } - C_{{s}} \left ( \frac {{R}}{r} \right )^{2} \right ]\! , \end{align}

\begin{align} v_{1r} & = U_0 ( \cos \theta + \varepsilon \mathrm{e}^{-{\mathrm{i}} \varphi } \sin \theta ) \left [ {X_{{s}} + Z_{{s}} } - C_{{s}} \left ( \frac {{R}}{r} \right )^{2} \right ]\! , \end{align}

\begin{align} v_{1\theta } & = - U_0 ( \sin \theta - \varepsilon \mathrm{e}^{-{\mathrm{i}} \varphi } \cos \theta ) \left [ {X_{{s}} - Z_{{s}}} + C_{{s}} \left ( \frac {{R}}{r} \right )^{2} \right ]\! , \end{align}

\begin{align} v_{1\theta } & = - U_0 ( \sin \theta - \varepsilon \mathrm{e}^{-{\mathrm{i}} \varphi } \cos \theta ) \left [ {X_{{s}} - Z_{{s}}} + C_{{s}} \left ( \frac {{R}}{r} \right )^{2} \right ]\! , \end{align}

concluding the first-order calculations. The velocity (3.13) is a superposition of the flows generated by the oscillations in the

![]() $ x$

- and

$ x$

- and

![]() $ y$

-directions, respectively. Furthermore, the solution of Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954) is obtained by putting

$ y$

-directions, respectively. Furthermore, the solution of Holtsmark et al. (Reference Holtsmark, Johnsen, Sikkeland and Skavlem1954) is obtained by putting

![]() $ \varepsilon = 0$

and subtracting

$ \varepsilon = 0$

and subtracting

![]() $ \boldsymbol{U}$

from (3.13) and multiplying the result by

$ \boldsymbol{U}$

from (3.13) and multiplying the result by

![]() $ - 1$

, in accordance with the coordinate transformation.

$ - 1$

, in accordance with the coordinate transformation.

3.3. Calculation of steady second-order streaming

The steady second-order Lagrangian streaming followed by a tracer particle, represented by

![]() $ \psi _{2}^{\textit{lg}}$

, is the sum of two terms: (i) the Eulerian term

$ \psi _{2}^{\textit{lg}}$

, is the sum of two terms: (i) the Eulerian term

![]() $ \psi _{2}$

arising from the nonlinear term in (3.6) and (ii) a Stokes drift term

$ \psi _{2}$

arising from the nonlinear term in (3.6) and (ii) a Stokes drift term

![]() $ \psi _{2}^{\textit{sd}}$

accounting for the difference between the Lagrangian and Eulerian descriptions of the flow fields

$ \psi _{2}^{\textit{sd}}$

accounting for the difference between the Lagrangian and Eulerian descriptions of the flow fields

Here,

![]() $ \langle \boldsymbol{\cdot }\rangle$

denotes a time-averaged quantity. Equation (3.14c

) corresponds to the time average of the second-order (3.6), and, as suggested by Raney et al. (Reference Raney, Corelli and Westervelt1954), (3.14d

) represents the lowest-order correction of the discrepancy between the time-averaged Lagrangian velocity of a fluid parcel and the time-averaged Eulerian velocity of the fluid. Furthermore, the Lagrangian velocity

$ \langle \boldsymbol{\cdot }\rangle$

denotes a time-averaged quantity. Equation (3.14c

) corresponds to the time average of the second-order (3.6), and, as suggested by Raney et al. (Reference Raney, Corelli and Westervelt1954), (3.14d

) represents the lowest-order correction of the discrepancy between the time-averaged Lagrangian velocity of a fluid parcel and the time-averaged Eulerian velocity of the fluid. Furthermore, the Lagrangian velocity

![]() $ \boldsymbol{v}_2^{\textit{lg}}$

satisfies the no-slip condition on the surface of the cylinder and tends to zero for large

$ \boldsymbol{v}_2^{\textit{lg}}$

satisfies the no-slip condition on the surface of the cylinder and tends to zero for large

![]() $ r / {R}$

, giving the following boundary conditions for

$ r / {R}$

, giving the following boundary conditions for

![]() $ \boldsymbol{v}_2$

:

$ \boldsymbol{v}_2$

:

Substituting (3.13) for

![]() $ \boldsymbol{v}_1$

into (3.14d

), the Stokes drift term

$ \boldsymbol{v}_1$

into (3.14d

), the Stokes drift term

![]() $ \psi _{2}^{\textit{sd}}$

and the corresponding velocity

$ \psi _{2}^{\textit{sd}}$

and the corresponding velocity

![]() $ \boldsymbol{v}_2^{\textit{sd}}$

are readily obtained as

$ \boldsymbol{v}_2^{\textit{sd}}$

are readily obtained as

\begin{align} \psi _{2}^{\textit{sd}} & = \frac {1}{2} {\frac {U_0^2}{\omega }} \bigg \{ [ ( 1 - \varepsilon ^{2} ) \sin 2 \theta - 2 \varepsilon \cos \varphi \cos 2 \theta ] \textrm {Im} \bigg [ \Big ( \frac {{R}}{r} \Big )^{2} C_{{s}} X_{{s}}^{\ast } + X_{{s}} Z_{{s}}^{\ast } \bigg ] \nonumber \\ & \quad - \varepsilon \sin \varphi {\mathrm{Re}} \bigg [ \Big ( \frac {{R}}{r} \Big )^{4} \lvert C_{{s}} \rvert ^{2} - 2 \Big ( \frac {{R}}{r} \Big )^{2} C_{{s}} Z_{{s}}^{\ast } + \lvert Z_{{s}} \rvert ^{2} - \lvert X_{{s}} \rvert ^{2} \bigg ] \bigg \} , \end{align}

\begin{align} \psi _{2}^{\textit{sd}} & = \frac {1}{2} {\frac {U_0^2}{\omega }} \bigg \{ [ ( 1 - \varepsilon ^{2} ) \sin 2 \theta - 2 \varepsilon \cos \varphi \cos 2 \theta ] \textrm {Im} \bigg [ \Big ( \frac {{R}}{r} \Big )^{2} C_{{s}} X_{{s}}^{\ast } + X_{{s}} Z_{{s}}^{\ast } \bigg ] \nonumber \\ & \quad - \varepsilon \sin \varphi {\mathrm{Re}} \bigg [ \Big ( \frac {{R}}{r} \Big )^{4} \lvert C_{{s}} \rvert ^{2} - 2 \Big ( \frac {{R}}{r} \Big )^{2} C_{{s}} Z_{{s}}^{\ast } + \lvert Z_{{s}} \rvert ^{2} - \lvert X_{{s}} \rvert ^{2} \bigg ] \bigg \} , \end{align}

\begin{align} v_{2 \theta }^{\textit{sd}} & = {\frac {U_0^2}{\omega R}} \frac {{R}}{r} \Bigg \{ [ ( 1 - \varepsilon ^{2} ) \sin 2 \theta - 2 \varepsilon \cos \varphi \cos 2 \theta ] \nonumber \\ & \quad \times \textrm {Im} \Bigg [ \Big ( \frac {{R}}{r} \Big )^{2} C_{{s}} X_{{s}}^{\ast } + X_{{s}} Z_{{s}}^{\ast } + \frac {x_{{s}}^{2}}{4} \Big ( \frac {r}{{R}} \Big )^{2} \bigg ( \lvert X_{{s}} + Z_{{s}} \rvert ^{2} - \Big ( \frac {{R}}{r} \Big )^{2} C_{{s}} (X_{{s}}^{\ast } + Z_{{s}}^{\ast }) \bigg ) \Bigg ] \nonumber \\ & \quad - 2 \varepsilon \sin \varphi {\mathrm{Re}} \Bigg [ \Big ( \frac {{R}}{r} \Big )^{4} \lvert C_{{s}} \rvert ^{2} - 2 \Big ( \frac {{R}}{r} \Big )^{2} C_{{s}} Z_{{s}}^{\ast } - \frac {x_{{s}}^{2}}{4} C_{{s}} (X_{{s}}^{\ast } + Z_{{s}}^{\ast }) + \lvert Z_{{s}} \rvert ^{2} \Bigg ] \Bigg \} . \end{align}