Following the adoption of the Charter, judicial review of federal legislation grew to an all-time high (McCormick, Reference McCormick2015). Review of federal legislation by the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) peaked during the government of Brian Mulroney in 1990 when the Supreme Court reviewed 21 pieces of federal legislation. Constitutional review remained high in 1991, 1992 and 1993, but rapidly returned to lower baseline levels in 1994, following the swearing-in of the government of Jean Chrétien in late 1993. During this period of high judicial review, the Court was especially active in reviewing criminal justice legislation under the Charter, particularly legislation adopted by previous Liberal governments. This agenda was largely consistent with Mulroney government criminal justice policy—Mulroney was somewhat ambivalent, more committed to civil libertarianism and less committed to neo-conservative “tough-on-crime” policy goals compared with contemporaries such as Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom. In most criminal justice legislation, Mulroney’s government simply reintroduced previously enacted Liberal legislation (Hatt et al., Reference Hatt, Caputo and Perry1992). The Chrétien Liberals, partly in response to the insurgent Reform Party, campaigned in 1993 on a tough on crime platform (“Liberals follow policy,” 1993), particularly as they pertained to sexual violence and juveniles, areas where the Court had been active in asserting its authority during the Mulroney government.

The peaks and valleys in constitutional review by the Supreme Court, we argue, are the result of two changes that occurred in the late 1980s and early 1990s. First, with the appointment of three justices in 1989, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney obtained a Conservative-appointed majority on the Supreme Court for the first time since 1967. That conservative majority would remain until 2000. This explains the rapid growth in judicial review by the Supreme Court: not only armed with new tools under the Charter, but crucially, facing a copartisan government in Parliament, the Supreme Court was empowered to use its judicial authority to advance priorities shared between the Justices and the government. However, following the change in government in 1993, the behaviour of the justices shifted, despite no change in Court personnel, as the Court found itself in partisan policy conflict with the new Liberal government.

To explain this episode, and similar patterns over time, this article develops a new theory of judicial review of federal statutes in Canadian federal politics. Consistent with previous findings, we understand the Supreme Court of Canada to be fundamentally policy-seeking, and we hold that its decision behaviour is driven in part by its partisanship (Macfarlane, Reference Macfarlane2018; Ostberg and Wetstein, Reference Ostberg, Wetstein and Ducat2007; Songer et al., Reference Songer, Johnson, Ostberg and Wetstein2012). However, we further argue that judicial review outcomes depend on the partisan relationship between the government and the Supreme Court. Specifically, we argue that the Supreme Court will tend to constrain itself, or autolimit, such as in its criminal justice decisions post-1994, when the partisan political environment does not support intervention by the Court. That is, the Supreme Court will be more likely to engage in judicial review when the government is copartisan, and therefore more likely to support Court action, and less likely to engage in judicial review when the government is counterpartisan. We argue that this is because a policy-seeking Court avoids granting leave in cases where Parliament may undermine the Court’s policy preferences in various ways, particularly by underenforcing or failing to adequately implement the Court’s judgments. We argue that the Court may find the status quo preferable to the risk of hearing cases in a counterpartisan political environment that raises the potential for inter-institutional conflict undermining the Court’s own preferences. Conversely, where the Court is copartisan with Parliament, the Court will be enabled to hear cases that advance its own policy agenda in coordination with political allies.

To test our theoretical prediction that judicial review will increase with greater copartisanship of the Supreme Court and Parliament and decrease as they drift further apart, we assemble a dataset of instances of review of statutes for constitutional compliance between 1968 and 2020 to determine whether and when each law is reviewed by the Supreme Court. This dataset includes all constitutional judicial review of statutes, whether the law was ultimately upheld and whether it was reviewed as potentially contrary to the Charter or ultra vires of Parliament. Notably, we focus on the decision of the justices to grant leave to appeal, and not the decision to strike a statute. This is because the justices exercise greater latitude at the agenda-setting stage. While the merits decisions of the justices are constrained by law and precedent, leave to appeal gives the justices a freer hand, thus allowing them to use their agenda control to avoid conflicts with Parliament.

Our study brings Parliament back into constitutional decision-making in Canada, albeit in an indirect way. We demonstrate the powerful role that Parliament plays in influencing Supreme Court decisions, in contrast with an extant literature that mostly views Parliament as deferential to the Court. Our findings suggest that Parliament can influence constitutional development, if not directly, then by influencing when and if the Supreme Court will take up thorny constitutional questions. This has important implications for the balance of power between the Supreme Court of Canada and the federal Parliament.

Background

We argue that the Supreme Court uses its leave decisions strategically in ways that have consequences for how we understand the extent of its authority. But if, as we will argue, one can discover political decision-making by observing departures from standard patterns of leave, one must first examine the formal standards and jurisprudence on leave to appeal decisions. Section 40(1) of the Supreme Court Act enables the Court to decide to grant leave to cases “by reason of its public importance.” In R. v Hinse, the Court asserted considerable discretion over leave.Footnote 1 Flemming and Kurtz describe a collection of other jurisprudential predictors for granting leave, including factors such as the need to revisit an important question in law, conflicting lower court decisions and dissenting votes in the lower courts. These scholars argue that institutional practices, such as the use of panels to make leave decisions, allow less room for the justices to act strategically despite the ideological differences between justices (Flemming and Krutz, Reference Flemming and Krutz2002a, Reference Flemming and Krutz2002b; Flemming, Reference Flemming2004). Macfarlane likewise notes that collegiality dominates the leave to appeal process, leaving “little room for strategic manoeuvring due to the institutional design of the process” (Macfarlane, Reference Macfarlane2013b: 99). However, these scholars are largely concerned with strategic behaviour between justices.

As Knopff et al. (Reference Knopff, Baker, LeRoy, James and Christopher2009) and Manfredi (Reference Manfredi and Peter2024: 186) have explained, judges face institutional constraints that force them to act strategically in pursuing their policy objectives. This produces strategic behaviour on two levels: (1) justices are constrained individually by rules governing their internal interactions with colleagues and (2) justices are constrained collectively by rules governing the relationship between the courts and other political institutions. Scholars have not empirically examined whether the justices are influenced by external factors at the leave stage. Johnson (Reference Johnson2019: 357), however, acknowledges the possibility that the agenda-setting stage introduces strategic action that is filtered out at the merits stage—alluding to the difficulty of identifying strategic behaviour if one only looks at merits decisions.

Thus, a forward-looking approach, consistent with Johnson’s suggestion, is warranted. While case features such as importance and lower court conflicts undoubtedly remain significant factors influencing leave decisions, if justices are forward-looking, they will sometimes also consider how their preferred disposition may lead to undesirable political outcomes if an opposed Parliament is uncooperative. This is consistent with strategic approaches that understand Supreme Court justices to be primarily policy-seeking.Footnote 2 For the justices to achieve policy goals, the Court must maintain institutional authority (Epstein and Knight, Reference Epstein and Knight1998; MacFarlane, Reference Macfarlane2013b). Our argument flows from and depends upon the literature on strategic behaviour in the Canadian Supreme Court and other national high courts, and specifically the way the Supreme Court may autolimit its decisions in service to its relationship with Parliament.Footnote 3 This autolimitation manifests as a shift from the baseline determinants of leave decisions.

This approach presents a contrast to the extensively examined executive–judicial relationship on issues of federalism and rights. Much of this work emphasizes the constraining effect that the Court and the Charter has on Parliament (Baker, Reference Baker2010; Kelly, Reference Kelly2005; Macfarlane, Reference Macfarlane2013b; Manfredi and Kelly, Reference Manfredi and Kelly1999; Roach, Reference Roach2001). Among the most significant findings is that it is uncommon for the legislature to substantively depart from judicial interpretations of rights regarding legislation (Macfarlane, Reference Macfarlane2013a). In this vein, Janet Hiebert (Reference Hiebert2002, Reference Hiebert, Campbell, Ewing and Tomkins2011, Reference Hiebert2012) has advanced a theory of the Charter in which the Supreme Court constrains Parliament as legislators attempt to predict and accommodate possible decisions by the SCC on questions of rights. Both Hiebert and Kelly have demonstrated that policy-making within the executive is largely shaped by judicial interpretations of rights (Hiebert, Reference Hiebert, Campbell, Ewing and Tomkins2011; Hiebert, Reference Hiebert and Macfarlane2018; Kelly, Reference Kelly2005). Meanwhile, in this view the Court remains largely insulated from the political wrangling in Parliament, able to make decisions unbothered by contextual and political constraints, though we also note recent studies that have considered attempts by governments to limit the impact of some judicial decisions while complying with their core premises (Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Hiebert and Drake2023; Kelly, Reference Kelly2024).

Yet, this literature has not fully considered that the compliance with Supreme Court decisions by Parliament that we generally observe may be a result of strategic choices by the justices. Scholars have pointed to instances of strategic behaviour on the Court, acknowledging that the Court constrains or accelerates its policy-seeking behaviour in response to the political environment. For example, Manfredi argues that the Supreme Court became more aggressive in its remedies in Charter cases after Quebec’s response to Ford v. A.G. Québec undermined the legitimacy of the use of the notwithstanding clause in English Canada and removed its constraining threat (Reference Manfredi2001: 155). Knopff et al. (Reference Knopff, Baker, LeRoy, James and Christopher2009) illustrate how the Supreme Court is strategic in its merits decisions by considering government audiences when crafting its rulings. We argue that similar strategic considerations about potential policy conflicts with Parliament could guide leave to appeal decisions, thereby exaggerating the apparent extent of parliamentary deference to the Supreme Court.

The institutional nature of these strategic decisions means that there is significant overlap between the strategic model and what Macfarlane calls the “institutional model” (Macfarlane, Reference Macfarlane2013b). This strategic approach to explaining judicial decision-making has been less influential in Canadian judicial politics scholarship, but the theoretical approach aligns with strategic accounts that are much more common in the American judicial politics literature.Footnote 4 Most relevant to our analysis is scholarship that considers external political constraints on the Supreme Court. For example, Spiller and Tiller (Reference Spiller and Tiller1996) argue that the Court would consider the preferences of other actors when interpreting federal statutes, lest their decisions be overturned by Congress. Bailey and Maltzman (Reference Bailey and Maltzman2011) show how deference to Congress and the Solicitor General affect Supreme Court behaviour. Other scholars have acknowledged that “institutional maintenance” may extend this logic to constitutional decisions, resulting in courts tempering those decisions (Clark, Reference Clark2010; Hall, Reference Hall2014; Harvey and Friedman, Reference Harvey and Friedman2009), or of relevance to our present study, avoiding those decisions altogether by denying certiorari (Harvey and Friedman, Reference Harvey and Friedman2006; Gardner and Thrower, Reference Gardner and Thrower2023). Such arguments extend beyond the American context as well. Vanberg (Reference Vanberg2001) argues that judicial independence in Germany is conditional on institutional context and legislatures can sometimes avoid compliance with Supreme Court decisions. Similarly, Helmke (Reference Helmke2002) demonstrates how the Argentinian Supreme Court is responsive to political context by engaging in more judicial review when the regime is weak. Together, these works collectively argue that the elected branches of government possess (and use) institutional tools that can serve to effectively constrain high court behaviour.

Related regime politics literatures can help to explain how the Supreme Court is likely to alter its behaviour when confronted with more friendly or hostile governments. Regime politics has been understood a number of ways in the literature, but in its most basic form, Supreme Court strategic behaviour is driven by partisan alignments between legislatures and courts.Footnote 5 Dahl first developed the regime politics thesis by arguing that, given unified political parties with partisan divisions over constitutional issues and a political process for appointing judges, it would be “unrealistic” to expect the policy views of the U.S. Supreme Court to substantially diverge from lawmaking majorities over the long term (Reference Dahl1957). Dahl argued that as Court personnel changed over time with appointments made by the political branches, the Court would shift ideologically to support positions of the governing regime.

Macfarlane adopts a regime politics approach to explain Supreme Court behaviour during the Harper government. Rather than focus on partisan alignments between parliaments and courts, Macfarlane characterizes the regime as a “Charter regime” or “court party” that reinforces prevailing ideological norms while transcending partisan shifts (see also Morton and Knopff, Reference Morton and Knopff2000). Macfarlane finds “basic core” support for regime politics in Canada, arguing that the Supreme Court of Canada rarely invalidates laws passed by a sitting federal Parliament—a trend that holds especially strong during the 1982–1993 period of competition between the federal Liberal and Progressive Conservative parties (‘2018: 8–9). Yet, he finds that Stephen Harper’s Conservative Party suffered distinctive levels of judicial resistance to high-salience policies (Reference Macfarlane2018: 2), even after making eight appointments to the nine-judge Supreme Court. Harper’s agenda departed from the “Charter regime” consensus of the past Liberal and Progressive Conservative governments, and he therefore faced conflict with a Court tied to the old regime (Macfarlane, Reference Macfarlane2018: 15).

On the contrary, the explicit application of a regime politics approach in the Canadian context has been criticized by other scholars. Kelly (Reference Kelly2024: 28) argues that the regime politics approach “founders on the shores of the Canadian shield” because it fails to account for Canada’s “disciplined cohesive parliamentary majorities” and the typical lack of “a dominant governing coalition” untethered to party politics. In essence, Kelly argues that majority governments simply do not need this judicial support because of the policy dominance of governing parties. Yet, this further reinforces our partisan regime approach. The uncertainty about the reaction of such a strong counterpartisan Parliament to judicial decisions may lead the Court to accommodate government preferences. Therefore, partisan regimes, contra the “Charter regime” described by Macfarlane and others, serve to constrain counterpartisan decision-making by the Court, rather than enable it. Indeed, our approach will avoid characterizing the Harper government as “an outlier [from the dominant governing coalition] during its ten years at the centre of government” (Kelly, Reference Kelly2024: 28), instead demonstrating that Harper government priorities mattered.

There is tension in the literature that we have outlined thus far. On the one hand, regime theories suggest that judicial power is contingent on and constrained by the (sometimes uneasy) alliances between elected officials and judiciaries. On the other hand, Canadian judicial politics scholars have argued that the Charter significantly empowers judiciaries at the expense of Parliament. As will be detailed below, our approach takes these two seemingly conflictual theories out of tension. By accounting for strategic behaviour of both Parliament and the Supreme Court and refocusing our attention to leave decisions, we highlight why and when judiciaries will be empowered, rather than whether they are empowered at the expense of Parliament. Our approach can clarify that the appearance of Parliament’s regular deference to the Supreme Court continually misses the autolimitation that the SCC applies to its own behaviour at the agenda-setting stage.

Theory

Canadian political scientists have convincingly argued that the federal Parliament does not generally constrain the Supreme Court reactively via legislative review or other active court-curbing measures such as the use of section 33. For example, in the “dialogue theory” debate, Canadian political scientists have demonstrated that the federal Parliament is relatively unwilling to enact noncompliant responses to judicial decisions with which it disagrees (Macfarlane, Reference Macfarlane2012; Manfredi and Kelly, Reference Manfredi and Kelly1999). Parliament does not generally appear to constrain the Court by how it reacts to the merits of decisions the Court has decided to hear. Put differently, it has been argued that it is the Court that constrains Parliament (Hiebert, Reference Hiebert2002). However, there are many cases and laws the Court decides not to review, which raises the question: does Parliament constrain the Court’s decision to grant leave to appeal in cases involving certain laws? As the review of existing scholarship above shows, this question has not been adequately investigated in the Canadian context. In this section, we offer our theory of partisan regime politics in the context of the Supreme Court of Canada’s decisions to review federal laws. We begin by first explaining the features of Canadian politics that enable Parliament to constrain the exercise of judicial review by hostile Courts. We then examine, conversely, why friendly Courts will be licensed to engage in more judicial review. Finally, we show how partisan licensing and constraint explain Supreme Court decisions granting leave to appeal and offer our formal hypotheses.

Parliamentary Constraints on the Supreme Court

The Canadian executive wields considerable power over the courts via the power to enforce judicial decisions. Executive enforcement power is significant because the executives can control how judicial orders are implemented by political officers and the administrative state, resulting in under- or nonenforcement of judicial pronouncements. Consistent with this argument, Macfarlane et al. (Reference Macfarlane, Hiebert and Drake2023) demonstrate that governments sometimes pursue objectives that may contradict existing jurisprudence when policy is particularly salient. Similarly, Kelly demonstrates the conditions under which a government can limit the impact of judicial invalidation through the legislative and policy implementation process: “because the courts cannot implement their rulings, with few exceptions, they are dependent on the political executives” (Reference Kelly2024: 22). For example, in 1990 the Supreme Court decided in Mahé v. Alberta (1990) that Alberta legislation did not respect minority language rights. Alberta took 3 years to address the matter, even minimally, while publicly signaling its intent not to comply (Riddell, Reference Riddell and Morton2004; Urquhart, Reference Urquhart, Sutherland and Schneiderman1997).

Similarly, following the decision in Canada v. PHS Community Services Society (2011) requiring supervised injection sites when such facilities reduce the risk of death, it took a full 44 months after the decision for Parliament to amend the legislation. The amendments included an onerous application process to operate a supervised injection site, and the Harper government never approved any subsequent applications for such sites (Kelly, Reference Kelly2024). Executive defiance of judicial decisions tends to take this underenforcing shape in the Canadian context: publicly grudging and minimal compliance with judicial rulings that may help push courts to take more deferential and circumscribed approaches to future remedies.

These actions can create uncertainty for the Court about whether the Court’s policy preferences will be implemented under counterpartisan government. The threat of non- or underenforcement (or worseFootnote 6) will often not be worth the risk of overturning the policy status quo. Furthermore, policy conflict and underenforcement may have implications for the perceived legitimacy of the Court—legitimacy the justices strive to preserve (Macfarlane, Reference Macfarlane2013b). It follows that if the justices want to maximize their policy preferences, including the institutional legitimacy that can help them to pursue their policy preferences, they may be incentivized to avoid policy decisions where Parliament may act in apparent conflict with judicial commands. By looking at decisions to review cases, we can begin to demonstrate that parliamentary preferences constrain judicial behaviour.

Licensing Supreme Court Power

The critical ingredients for parliamentary constraint on the Supreme Court are present, and some evidence suggests partisan conflict may trigger constraint. However, our partisan regime politics theory also suggests that alignment between the Supreme Court and Parliament can license more judicial review. More recent theories of regime politics extend and clarify Dahl’s thesis as we describe it above. Whittington, for example, argues that governing majorities can welcome exercises of judicial power where political divisions make settlement of constitutional issues more difficult (Whittington, Reference Whittington2007: 288, Reference Whittington2019b: 289–91). Political officials will sometimes welcome judicial intervention to settle rights issues that cross party lines (Graber, Reference Graber1993) and to overcome status quo obstacles to policy objectives such as entrenched interests or federalism (Whittington, Reference Whittington2005).

Similarly, in the Canadian context, Canadian political parties feature cross-cutting disagreements about rights issues such as abortion, and Canada is well known for featuring robust disputes about constitutional federalism (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone2019). Greene (Reference Greene2006) argues that the Supreme Court of Canada can helpfully step in to clarify policy where the legislature leaves gaps under conditions of partisan alignment between the Court and Parliament. Although the regime politics approach is often understood in Dahl’s paradigm of political regimes constraining courts, scholars such as Whittington and Greene help show how it can license judicial power in contexts where governing coalitions and courts are part of the same partisan or ideological regime. In some cases, the Court may be licensed by a copartisan Parliament to take a case to strike down the laws of past rival Parliaments. In others, the Court may simply be licensed by the decreased likelihood of a copartisan Parliament contesting its decisions. We need not distinguish between these motivations—our hypotheses are consistent with various ways that counterpartisan Parliaments constrain or copartisan Parliaments license the Court.

A Theory of Partisan Regime Influence on the Supreme Court Agenda

Together, we argue that these tools of licensing and constraint should allow us to observe effects of the alignment between parliamentary and judicial partisanship on Supreme Court choices over leave to appeal. We claim that partisan factors operate in tandem with traditional legal factors such as importance and conflict (Flemming, Reference Flemming2004) and should be considered alongside them. Our theory assumes that justices are primarily policy-oriented, though we are agnostic about what informs those policy preferences. We also assume that justices are strategically forward-looking and will seek to avoid granting leave to appeal in cases where their own policy preferences conflict with that of the government in Parliament (Epstein and Knight, Reference Epstein and Knight1998). Our second assumption is grounded in the likelihood that perceived parliamentary policy conflict constrains counterpartisan Courts that would maximize their own policy preferences. For example, a strategically cautious Court will avoid reviewing salient laws where the majority of justices might have policy preferences at odds with strong preferences of the sitting government and wider public; judicial review provoking adverse reactions from Parliament or the government may threaten judicial policy preferences and institutional legitimacy, making the status quo more palatable.Footnote 7

With these assumptions in mind, we offer our somewhat counterintuitive prediction—that the Court will be licensed to engage in more judicial review of legislation when it shares the same policy goals as the Parliament in power and constrained to engage in less review of statutes when its policy goals conflict with the concurrent Parliament. Furthermore, we take it that where the Court shares policy goals with the current Parliament, it will be more likely to review legislation from past regimes that do not share these goals. We call our theory a “partisan” theory of regime politics because we argue that in the Canadian context, the best heuristic for predicting the shared policy goals of Parliament and the Court is partisanship rather than ideology. And so our predictions are best characterized in terms of partisanship, such that Courts that are copartisan with Parliaments are more likely to review federal laws and divergent Courts less likely to do so.

We employ partisanship as a measure of policy agreement in the Canadian context. In the American context, attitudinal scholars have used ideological measures to help explain regime constraints on judicial power rather than partisan measures (Segal and Spaeth, Reference Segal and Spaeth2002). This is because the U.S. has traditionally had weak parties, making partisanship a less useful measure, but in the Canadian context, scholars have used partisan measures to demonstrate some linkages between the ideology of prime ministers and the behaviour of justices they appoint (Ostberg and Wetstein, Reference Ostberg and Wetstein2007; Songer and Johnson, Reference Songer and Johnson2007; Johnson, Reference Johnson2019).Footnote 8 Moreover, the complicated history of Canada’s multiparty system as broad brokerage groups that fracture and regroup in response to heated regional (and separatist) politics make it more difficult to track the ideology of parties in control of Parliament than in the American context (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone2019). Partisanship is a simpler measure of policy preferences that should be more difficult to use as a predictor of policy convergence or divergence precisely because of ideological heterogeneity and institutional division/reform that characterizes Canadian federal parties. If our findings confirm our theory using partisanship as a measure of policy convergence or divergence, then the theory may be even stronger for it.

Although our theory focuses on decisions to review statutes in relationship to contemporaneous Parliaments and Courts, we can also theorize the significance of the partisan origins of laws. In our theory, we would expect Courts that are unified with their contemporaneous Parliament in terms of partisan membership to review more laws enacted by rival parties and less or normal levels of copartisan laws. This is the regime politics insight that copartisan courts and legislatures license Courts to review laws of rival parties because reviewing such laws is less likely to provoke constraining reactions and more likely to serve the interests of partisan allies currently enjoying legislative power. We would also expect Courts that are divergent from their contemporaneous Parliament’s partisanship to review fewer laws enacted by the current Parliament and perhaps also fewer laws enacted by Parliaments copartisan to the contemporary Parliament.

The logic behind this prediction is that a law enacted by a past Parliament of the same party as the current Parliament is more likely to be valued by the current Parliament, which incentivizes the current Parliament to constrain a Court reviewing and thereby potentially invalidating such laws. We also expect that the divergent Court’s caution will even extend to past laws enacted by its own partisan allies that diverge from the current Parliament, because even reviewing the past policy may raise its salience in the eyes of the current Parliament. Divergent Courts may reason that it is better to let sleeping dogs lie than to raise the profile of policies the current Parliament is likely to have different views on. Our theory in this article is focused on decisions to review and we leave more in-depth discussion of merits cases to future work. In summary, we predict that the Supreme Court will (1) be less likely to grant leave to appeal when facing a counterpartisan government, (2) more likely to grant leave to appeal under a copartisan government, and (3) copartisan, regime-supporting Courts will be more likely to review legislation originating from outside the party of the regime.

Data and Methods

For our analysis, we use a statute-centered approach with the unit of analysis as the statute-year. There are a number of reasons to avoid a case-based approach, some of which have already been hinted at in our theory above. Most importantly, the decision by the Supreme Court to hear a case is already an ideological or political decision because the Supreme Court has a largely discretionary docket. The Supreme Court has enjoyed a degree of discretion over its caseload (particularly in constitutional cases) since its establishment in 1875, and amendments to the Supreme Court Act granted near complete discretion in 1975 (R.S.C. 1985 c. S-26). Prior to 1975, 85 per cent of cases were decided as nondiscretionary appeals of right and roughly 15 per cent by leave; after the 1975 reforms these numbers were almost exactly reversed (McCormick, Reference McCormick2000: 87; Macfarlane, Reference Macfarlane2009: 6).Footnote 9 As McCormick (Reference McCormick2015: 17) claims, “a court that controls its own docket is, or at least can be, a strategic court, as distinct from a purely reactive one.” By examining only cases that the Supreme Court has decided to hear, we would be ignoring any decision-making that the Supreme Court might engage in where it declines to hear cases because of the potential political consequences of that decision. We argue that a politically cautious court would be likely to avoid conflict with Parliament by declining to review statutes when the threat of nonenforcement, open criticism or other political consequence is high. Under these circumstances, using a case-based approach that focuses on merits decisions will rarely identify situations where the court has constrained its own decision-making for political reasons because it will have excluded the key decision—construction of the agenda—from analysis.Footnote 10

To examine our hypotheses, we require a dataset of review of statute at the bill-year level as the dependent variable. We analyze instances of judicial review beginning in the 28th Parliament in 1968.Footnote 11 To do this, we track all public laws between the 20th and 43rd Parliaments, noting each year that they were “reviewable.” Acts adopted in 1968, for example, can be potentially reviewed in 1968 and any year after for bills not repealed by Parliament. Acts adopted prior to 1968 we code as reviewable in 1968 forward. Next, we cross-referenced these Acts of Parliament with a newly developed database of all federal statutes reviewed by the Supreme Court of Canada during the period, whether on Charter grounds or as ultra vires of Parliament. We can demonstrate the structure and collection of our data with the 1993 amendments to the Canada Elections Act as an example. Adopted in the waning days of the Mulroney government, the amendments made wide-ranging changes, both consequential and mundane, to the administration of Canadian elections. Given its passage in 1993, the amendments have been “reviewable” by the Supreme Court in the 28 years from 1993 to 2020 (inclusive) and therefore appear in the data 28 times. In those 28 years, the amendments have been reviewed three times: in 1998 (Thomson Newspapers Co. v. Canada), 2002 (Sauvé v. Canada) and 2019 (Frank v. Canada).

To identify cases reviewing the amendments to the Canada Elections Act, we first developed all cases of review of federal statute. There is no canonical source of review of statute in Canada, though some lists developed for other purposes exist. Therefore, following Whittington (Reference Whittington2019a), we begin from scratch by examining all cases of the Supreme Court of Canada between 1968 and 2020 for evidence of review of statute. Given the large number of cases to examine, our “first sweep” relied on computer text searches to identify key terms that are often associated with Charter or ultra vires review. Our searches were designed to be intentionally over-inclusive. From here, each case was individually examined to (1) confirm the presence of constitutional review of federal statute and (2) identify the federal statute under review. The latter step requires some care—taking again our example of the Canada Elections Act, the Act has been amended dozens of times, thus we were careful to track the specific provision under review to the legislation that adopted the provision. In the cases of Thomson, Sauvé and Frank, though the Court often identified the Canada Elections Act as amended, we tracked each provision under review to the 1993 amendments.

The most common outcome for any statute in any year, of course, is that it is not reviewed. In those bill-years, our dependent variable is recorded as “0.” In years where the Supreme Court does review a federal statute, the bill-year dependent variable takes a “1.” Therefore, for example, the 1993 amendments to the Canada Elections Act appear in the data as reviewable between 1993 and 2020 and are marked as “0” in all years except 1998, 2002 and 2019, when the variable is recorded as “1.” We repeat this procedure for all Acts of Parliament. The resulting dataset contains 171,508 observations, including 3,668 Acts of Parliament and 241 cases of constitutional review over the course of the years from 1968 to 2020. Instances of review are rare but substantively important—Supreme Court review of parliamentary statute is among the most politically significant actions taken by the Court. Therefore, understanding the factors influencing this rare choice by the justices is critical in large part as a result of the rarity of the use of judicial review.Footnote 12

The key independent variables for our analysis are related to the partisanship of Parliament and the Supreme Court. We are primarily interested in the partisanship of Parliament at the time of review (and not the time of the passage of the bill). Our measure of the partisanship of Parliament is a variable indicating the proportion of seats in the House of Commons held by the Liberal Party.Footnote 13 This variable is useful as both an indicator of who is in power and the strength of the government in Parliament.

Our regime politics theory primarily asks whether behaviour of Supreme Court justices is influenced by the alignment between the government in power and the partisanship of the justices currently sitting on the Supreme Court. Therefore, we also require a measure of the partisanship of the justices. The appointment power is formally a prerogative power of the Governor General on the advice of the prime minister but de facto under the unconstrained power of the prime minister (see Hausegger et al., Reference Hausegger, Riddell, Hennigar and Richez2010; Hausegger et al., Reference Hausegger, Riddell and Hennigar2013; and Riddell et al., Reference Riddell, Hausegger and Hennigar2008). The prime minister does not require parliamentary advice and consent over judicial appointments and tends to enjoy unified majority control over a national legislature with weaker bicameralism, all of which suggests that partisanship may be a good proxy for judicial attitudes. And research bears out that the partisanship of the appointing prime minister does matter for predicting the ideological behaviour of justices on the Supreme Court of Canada (Ostberg and Wetstein, Reference Ostberg and Wetstein2007; Songer et al., Reference Songer, Johnson, Ostberg and Wetstein2012). Therefore, in each year, we identify the number of sitting Supreme Court justices that were appointed by a Liberal prime minister.Footnote 14

We further collect control variables that may have significant impact on the likelihood of review. In addition to the partisanship of the current government, we may think that the partisanship of the adopting government would also affect the likelihood of review. After all, if lawmaking has ideological and partisan components, the political leanings of the Parliament that adopted the bill may well affect the choice of partisan justices to review a bill. Furthermore, this also controls for any bias that may result from the fact that Liberal governments have held power for more years in our sample and therefore have had more opportunities for lawmaking.Footnote 15 We therefore construct variables indicating the partisanship of government and Liberal seat-share in Parliament at the time the Act is adopted. Studies have indicated that older statutes are more likely to be reviewed than newer statutes (Dahl, Reference Dahl1957), therefore we construct an integer variable indicating the age of a statute, with the variable taking a value of “0” in the year of passage, “1” in the next year and so on. Our regime politics theory focuses on partisan alignment, but scholarship on the Supreme Court of Canada has demonstrated a role for ideology independent of partisanship (Ostberg and Wetstein, Reference Ostberg and Wetstein2007). We therefore also construct a “lifetime liberalism” measure for each Supreme Court justice, which is the percent of nonunanimous decisions made in a more progressive ideological direction (Segal and Spaeth, Reference Segal and Spaeth2002). We then average across these liberalism measures in each year to create a Supreme Court ideological “progressivism” score in each year to control for any differential effects of partisanship and ideology.

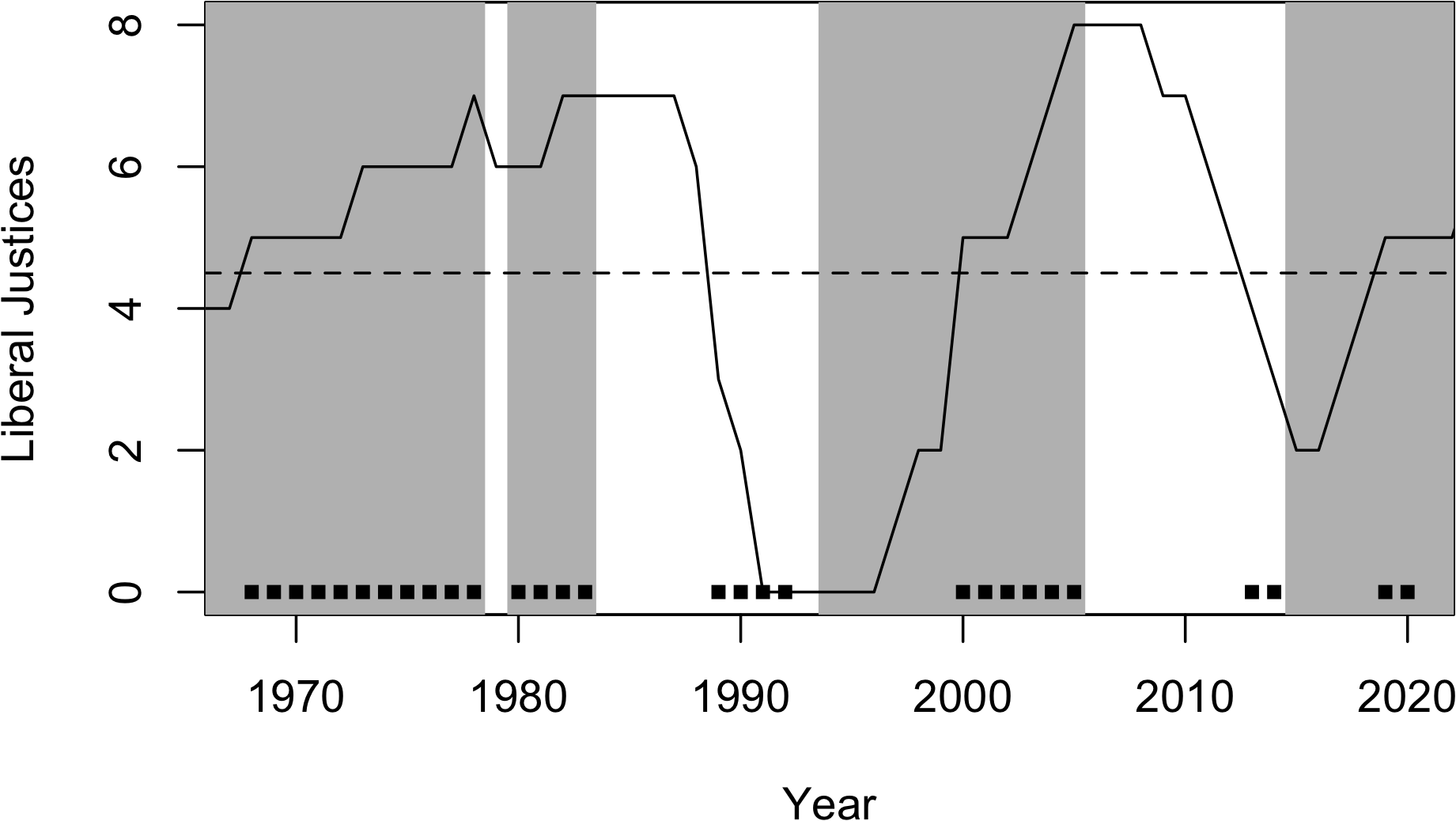

The key partisanship variables as they vary by year are shown in Figure 1. The solid line indicates the number of Liberal-appointed justices on the Supreme Court. Shaded regions represent periods of Liberal government, while unshaded regions are Conservative governments. The dotted line represents the border between Liberal and Conservative majorities on the Supreme Court. When the solid line is above the dotted line, the Court majority is Liberal-appointed and Conservative-appointed when below the dotted line. The figure makes it easy to see the substantial swings from solid Liberal majorities in the pre- and early-Charter eras to a 9-0 Conservative majority during the Mulroney years and continuing the cycle with changes of government. The black dots along the bottom of the graph indicate that the government in Parliament and the majority of the Supreme Court were in the same party during a given year. Our theory suggests that judicial review of statute will be more likely during these years of alignment.

Figure 1. Partisanship of Supreme Court Justices and Parliament.

Note: The solid line indicates the number of Liberal-appointed justices on the Supreme Court. Shaded regions represent periods of Liberal government, while unshaded regions are Conservative governments. The black dots along the bottom of the graph indicate that the government in Parliament and the majority of the Supreme Court were in the same party during a given year.

Some statutes, the Criminal Code for example, are more likely to be reviewed than other statutes independent of the political constraint theory we present here. As we note above, Section 40(1) of the Supreme Court Act dictates that public importance should guide leave decisions, and we expect the salience of policy areas on the likelihood for leave to be granted to be considerable, though analysis of the effect of policy area is not directly relevant to the theory we examine. We account for this in three ways. First, continuing our example of the Criminal Code, by tracking the specific provisions challenged back to the authorizing bill, our analysis allows for more variation in outcomes because the Criminal Code is treated as dozens of bills and amendments rather than just one statute. Second, the subject matter of statutes will have some independent effect on the likelihood of review that is not captured by our variables of interest. The type of policy at issue in each statute is likely to influence its baseline level of review, whether due to political salience, legal complexity or judicial priorities. Indeed, the literature has demonstrated the tendency of the Supreme Court to review cases dealing with rights and liberties (for example, Epp, Reference Epp1996). We therefore also identify each statute by policy “topic.” We use topic codes from the Canadian Agendas Project (CAP), which categorize statutes adopted between 1968 and 2004 across 27 broad categories, including topics such as defense, macroeconomics, trade, civil liberties and so forth. We extend this categorization forward to 2020 and backward to 1949 to cover our full dataset. These policy areas are included in the models as fixed effects, which allows each policy area to have a different baseline level of review.Footnote 16 Third, in all our models, we use standard errors clustered at the bill level. This corrects for any correlation in the residuals that may arise due to the relative differences in the baseline risk of review of individual statutes.

Results

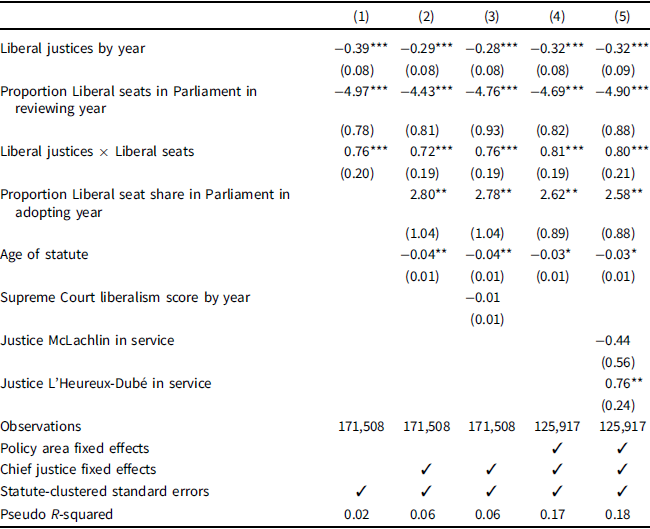

To examine our hypothesis, we employ logit regression with the presence of review as the dependent variable. Logit models are appropriate for the binary response structure (reviewed or not reviewed in a given year). The logit regression coefficients in Table 1 show the influence of our key independent variables on the probability that a statute is reviewed in any given year. Model 1 includes only our key variables of interest. For the remaining models, we add controls in a stepwise fashion to show that our results are robust to omitted factors but are not dependent on the inclusion of any particular set of controls. Model 2 adds controls, excluding Supreme Court ideology as measured by the mean of the lifetime liberal decisions of the justices sitting on the Supreme Court and policy area fixed effects. Model 3 adds judicial ideology with null effect. Chief justices have significant administrative power over the composition of leave to appeal panels. As such, models 2 and 3 include chief justice fixed effects to account for any differences in administrative priorities between the chiefs and to account for secular changes in the Court’s behaviour and caseloads over time.Footnote 17 Model 4 includes all variables except ideology with the addition of policy topic fixed effects.Footnote 18 Policy fixed effects help control for the fact that statutes in some policy domains (for example, crime, civil liberties) may be more likely to be reviewed regardless of political dynamics. Indeed, our results indicate the significance of policy area in leave decisions, as can be observed through the increased fit in models 4 and 5. Including them helps ensure that our estimates of the main political effects are not confounded by differences in policy-specific effects on review, including salience, but our central result is not driven by any particular policy areas.Footnote 19 Finally, Johnson and Masood (Reference Johnson and Masood2023) argue that agendas have been affected by gender changes on the Court. Indeed, peaks in reviewing we identify occur near the time of appointments of Justices McLachlin and L’Heureux-Dubé. All models account for C.J. McLachlin’s tenure through chief justice fixed effects, but model 5 adds variables to account for the entire tenure of each Justice McLachlin and Justice L’Heureux-Dubé.Footnote 20 All models include cluster-robust standard errors with the cluster at the statute level to account for the fact that each statute may appear in the data across multiple years and ensures that our estimates of statistical significance are not overstated. The results are substantially similar across specifications. Our results are robust to the inclusion of several other control variables that have been demonstrated to influence Supreme Court behaviour.Footnote 21 We discuss results from model 4.

Table 1. Partisan Regimes and Judicial Review

Note: Coefficients from logit regression, with robust standard errors clustered by law in parenthesis. The dependent variable is a binary variable taking a “1” when a law is reviewed in a given year. Two tailed tests, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

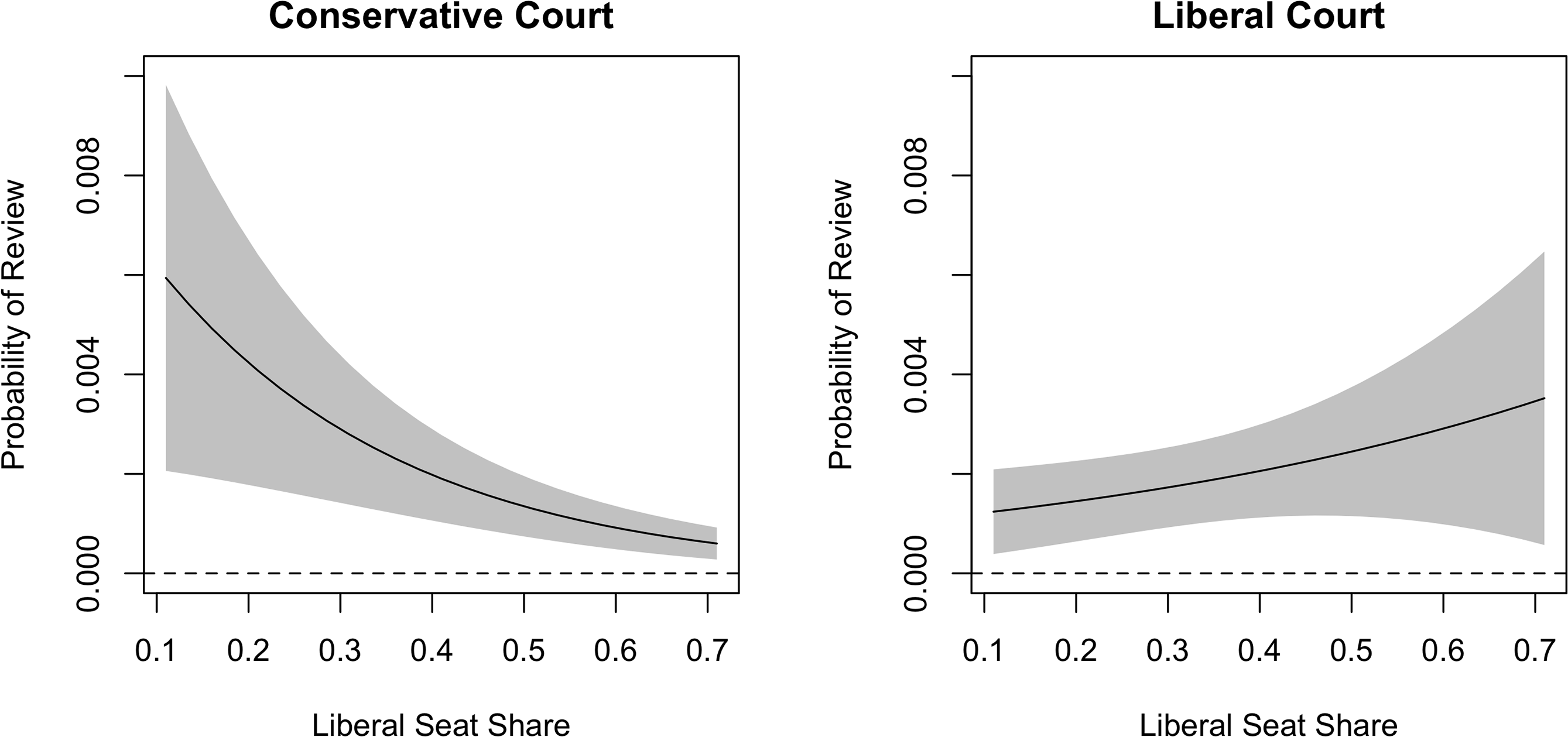

The results provide support for our central hypothesis.Footnote 22 The coefficients are significant and in the expected directions, but the interaction terms are more readily interpreted graphically in Figures 2 and 3. As can be seen in the left panel of Figure 2, when the Supreme Court is quite conservative (in this case with eight conservative justices on the Court), the justices are more likely to review acts of Parliament when there are large Conservative majorities in Parliament. Specifically, when Parliament is most Conservative, the Court is about 0.5 per cent more likely to review a given law. These effects appear small, but when considered in the context that any given statute in any year only has about a 0.1 per cent chance of review as a baseline, the results are substantively significant. Alternatively, we can interpret this result in terms of the odds of review. For a Conservative-appointed Supreme Court, the odds of reviewing any given statute is more than five times as high under the largest Conservative majorities compared with more Liberal parliaments.

Figure 2. Change in the Probability of Review Conditional on Alignment of Parliament and the Supreme Court.

Note: Predicted probabilities derived from model 4. The left panel shows the probability that any given statute is reviewed for a Supreme Court with eight conservative justices. The right panel shows the probability that any given statute is reviewed for a Supreme Court with eight Liberal justices.

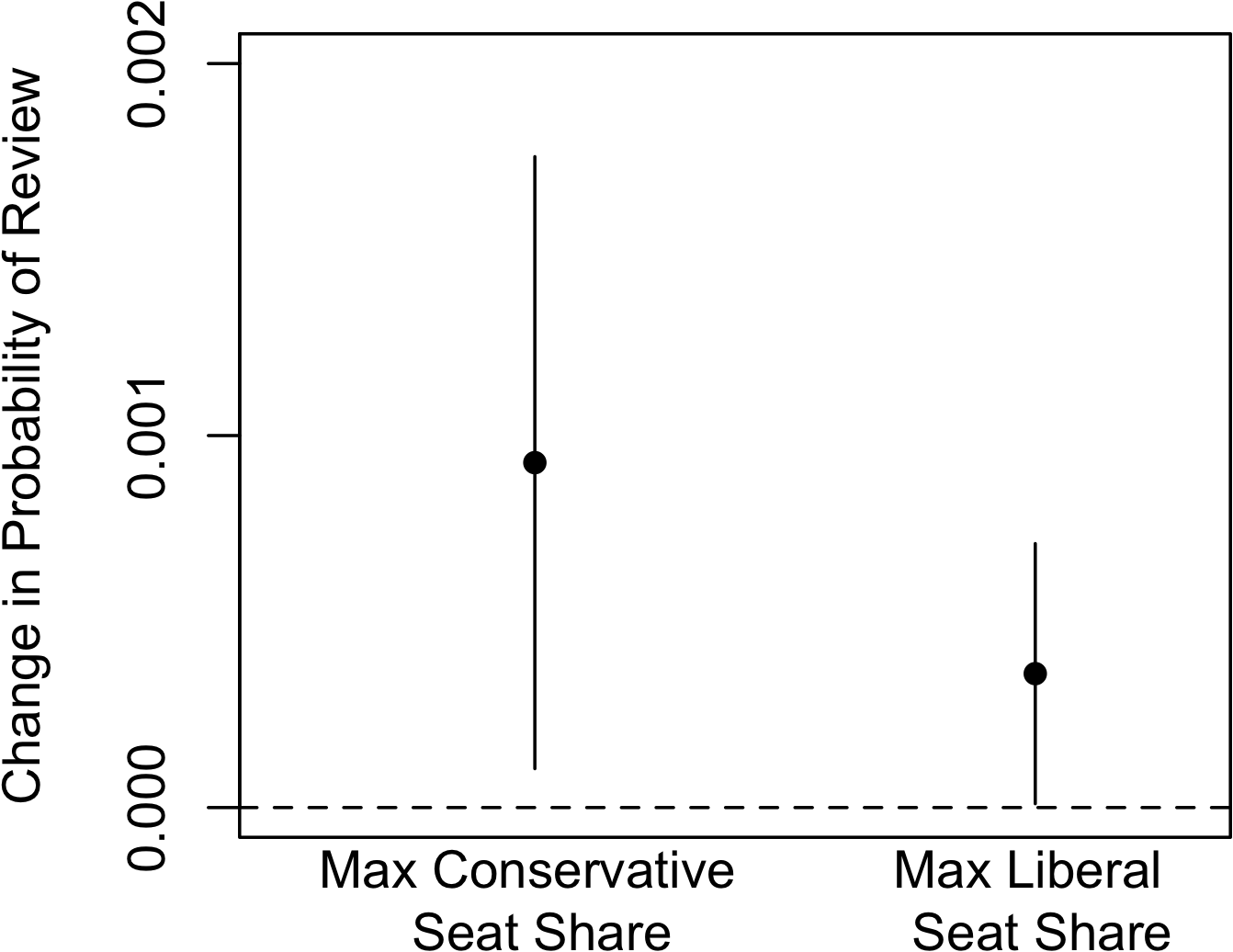

Figure 3. Effect of the Addition of One Copartisan Justice on the Probability of Review.

Note: Point estimates with 95% confidence intervals. For both conservative and liberal parliaments, the effect is statistically distinguishable from zero.

The effect size for Liberal-appointed Supreme Court (with eight Liberal justices) is smaller, but still significant. Liberal courts are about twice as likely to review statutes under the most Liberal parliaments. Figure 3 confirms that the slope is distinguishable from zero and further shows that the results displayed are not sensitive to the choice of a large majority of eight justices in Figure 2. Rather, the addition of a single copartisan justice on average increases the odds of constitutional review for any given statute by about 35 per cent for Liberals and 90 per cent for Conservatives, with both effects distinguishable from zero.

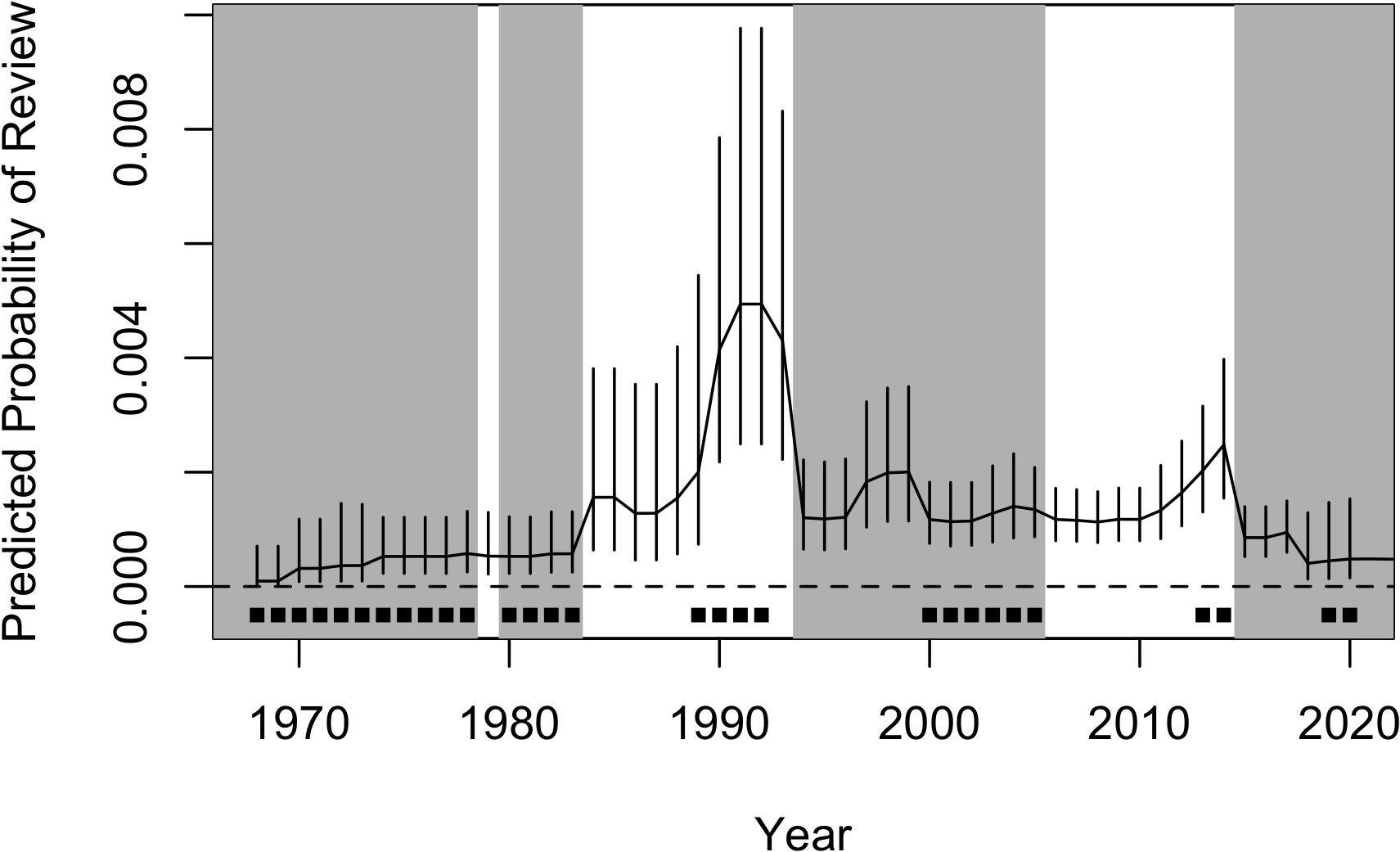

These predicted probabilities are useful to understand the effect of partisanship in hypothetical conditions. But how often do these conditions hold and what are the effects within sample? To answer these questions, we show predicted probabilities of review across years, as can be seen in Figure 4. The graph shows the effect of the interaction between Liberal Seat Share and Liberal Justices (including their direct effects) at their actual values from 1968 to 2020. Control variables are held at their means while chief justice fixed effects are held at their actual values. The predicted probabilities echo the results displayed in the previous figures but emphasize even further the importance of alignment between Conservative governments and Conservative appointed Supreme Courts. Supreme Court review spikes during the years in which the Mulroney and Harper governments obtained majorities on the Supreme Court and plummet as Liberal governments take office, even with no change in Court personnel. These striking effects of partisan alignment suggest that even as attitudinalist theories tend to have weaker explanatory power in the Canadian context compared with the United States, inter-institutional politics may have greater value in identifying policy-motivated behaviour on the Supreme Court of Canada because political alignments largely determine when justices are more and less attitudinally constrained.

Figure 4. Predicted Probability of Supreme Court Review by Year.

Note: The solid line indicates the predicted probability of review in each year on the basis of actual observed values of the Liberal seat share, Liberal justices and chief justice variables. Other variables are held at their means. Vertical lines are 95% confidence intervals for the predicted probability of review. Shaded regions represent periods of Liberal government, while unshaded regions are Conservative governments. The black dots along the bottom of the graph indicate that the government in Parliament and the majority of the Supreme Court were in the same party during a given year. Predictions derived from model 4.

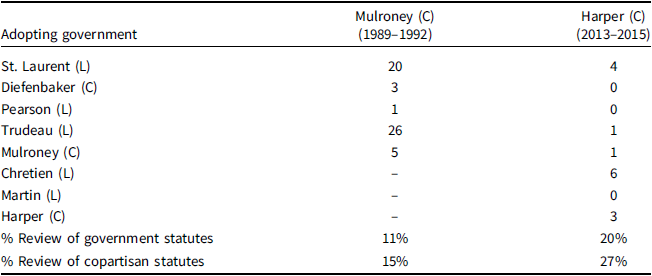

This is not a result of Supreme Court hostility to Conservative legislation. In the 4 years under the Mulroney government where the Supreme Court was majority Conservative-appointed, the Supreme Court reviewed federal legislation 55 times. Of those 55 instances of review, only 8 were reviewing Conservative legislation. The remaining 47 cases reviewed Liberal legislation. Likewise, during the period where the Harper government aligned with a conservative majority on the Supreme Court (2013–2015), the Court reviewed 15 federal statutes, 11 of which were adopted under Liberal predecessors (see Table 2). This further confirms our hypothesis that constitutional review is generally being used to support government priorities or at least is not exercised in direct opposition to those priorities when copartisanship reduces constraints on judicial priorities. Both mechanisms likely operate here—future work examining judicial merit decisions may be better able to distinguish between them.

Table 2. Supreme Court Review of Statute during “Unified” Government

Note: The table presents the number of instances of judicial review when the Supreme Court had a majority under the Mulroney and Harper Conservative governments by the targeted statute’s adopting government.

Discussion and Conclusions

The Charter promised significant change in Canadian constitutional law. The dominant narrative about this change has been one of a shift in power from Parliament to the Supreme Court. In addition, scholars have struggled to demonstrate how Parliament might rein in the discretion of the Court. Here, we show that Parliament remains a significant force in the interpretation of the Charter and the Constitution more broadly. While challenges to the merits decisions of the Supreme Court are rare, our analysis suggests that this may be because the Supreme Court avoids decision-making that would be more likely to draw hostile reactions from the government, thereby endangering judicial policy-making. Through their desire to protect their preferred policy outcomes, the justices avoid open conflict with Parliament, instead wielding their authority when parliamentarians are likely to support judicial intervention.

This has several consequences for how we understand Canadian constitutionalism and politics. First, it forces us to reconsider the role of Parliament in constitutional decision-making. Critics of the dialogue literature often lamented the lack of robust coordinate responses to Supreme Court decisions regarding Charter rights (Baker, Reference Baker2010). Our findings help explain how the lack of such coordinate dialogue may partly be a function of Parliament’s ability to passively influence the Court. Parliament does not reply to the Court’s decisions because the Court tends to avoid speaking when Parliament is likely to disagree. Second, it suggests a new mode of thinking about the “political” nature of Supreme Court decision-making. Where evidence for attitudinalism has typically been weaker in Canadian judicial decision-making than in other democracies, particularly the United States, our results suggest that scholars would be wise to look to inter-institutional influence in tandem with attitudinal influences to discover even more political activity on the Court.

Additionally, we should consider the normative consequences of these patterns. If powerful constitutional courts are heralded for their ability to make principled stands against majoritarianism for the benefit of individual and minority rights and freedoms, we suggest that there are limits to the Court’s ability to engage in such countermajoritarianism (Roach, Reference Roach2016). The impact of partisan alignment with Parliament as a constraint on the Court’s agenda suggests that the rarity of “activist” behaviour in merits cases against a counterpartisan Parliament (Macfarlane, Reference Macfarlane2018) results from strategic autolimitation. Our findings suggest that for every such case of judicial review against a sitting government, there are conflicts that counterpartisan courts have chosen to avoid.

In turn, our licensing mechanism also suggests that scholars should renew their focus on how the Supreme Court may be reducing the accountability of the political actors by relieving legislators of pressure to settle certain political matters or by striking down the laws of partisan rivals. In line with Morton and Knopff’s (Reference Morton and Knopff2000) claim that cross-pressured disagreement about rights issues across party lines within Parliament can undemocratically pass the “hot potato” to courts, we raise democratic accountability concerns related to the more general types of copartisan licensing evident in our leaves to appeal data. Our research demonstrates that the judicial review agenda of copartisan courts has the potential to yield political benefits for sitting governments, but further research on merits decisions is needed to evaluate the specific mechanisms at play. Still, our results are a first step in demonstrating the ways Conservative courts are politically valuable to Conservative politicians just as Liberal courts are valuable to Liberal politicians.

Our results also prompt new questions that should be explored through future research. For example, scholars might assess the mechanisms by which the Supreme Court is led to engage in autolimitation. Do increasing threats to use the notwithstanding clause affect judicial behaviour? Do cases that implicate policies of high priority for the government or high salience with the public cause the Court to be more deferential to Parliament? Does the Court demonstrate a difference in its willingness to review federal or provincial statutes? It may be that our statute-based approach can contribute to the long-standing debate about the “centralizing” role played by the Canadian judiciary (Morton, Reference Morton1995; Kelly, Reference Kelly2001). Further afield, if the justices are willing to accommodate parliamentary preferences through their decisions about what to place on their own docket through leave to appeal, the natural question that follows is whether they might also do so on the merits of their decisions. Does the Supreme Court temper their merits decisions in response to demands from elected officials? Might they decline to adopt constitutional questions and instead confine their analysis to statutory interpretation? Our current approach cannot answer these questions yet prompts us to explore these ideas further.

Our study joins a broadening chorus of work across many countries which shows how high courts are enabled and constrained by the political environment in which they work. We confine our analysis to the autolimiting effects of partisan regimes, but other limits to independence may be worth exploring. Though traditional theories of constitutionalism view constitutional courts as substantially independent, more and more work challenges the extent of this independence, showing when, why and how high courts are limited by elected officials. Whether court-curbing in Hungary and Poland (Aydin-Cakar, Reference Aydin-Cakir2023; Epperly, Reference Epperly2019) or legitimacy-threatening reforms to Courts in Mexico and Israel (Martin-Reyes, Reference Martin-Reyes2025; Navot and Lurie, Reference Navot and Lurie.2024), the effects of electoral and ideological politics are changing the global judicial landscape. It appears that Canada is not immune from these pressures. Scholars of Canadian courts, constitutions and parliamentary institutions would do well to consider the limits to the independence of the Supreme Court of Canada.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423925100991

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Minh Do, Jay Krehbiel and Sharece Thrower for their comments on previous drafts of this article and Matt Wilder for sharing CAP data. Additionally, we thank audiences in seminars at Queen’s University Centre for the Study of Democracy and Diversity, the Courts and Politics Research Group, the 2024 meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, the 2024 meeting of the American Political Science Association and the 2025 meeting of the Southern Political Science Association for helpful insights. We thank Bronwyn Moon-Craney for able and efficient research assistance. Any remaining errors are our own.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.