1. Introduction

A first-order or simple Markov chain, or just Markov chain as is often called in literature, is a widely used stochastic model in which the future state of a system is determined by its current state alone via some probabilistic rules, not by any of its past states. In many real-world problems, however, it often arises that the future state of a system depends on not only its current state but also a number of its past states following certain probabilistic rules. A higher-order or multiple Markov chain is exactly a stochastic model for such systems and has been adopted in many applied areas [Reference Baena-Mirabete and Puig1, Reference Burks and Azad2, Reference Flett and Kelly6, Reference Ho and Rajapakse13, Reference Islam and Chowdhury18, Reference Kwak, Lee and Eun21, Reference Lan, Li, Jilkov and Mu22, Reference Liu, Luo and Zhu25, Reference Masseran27, Reference Sanjari and Gooi28, Reference Xiong and Mamon30, Reference Yang, Jang and Kim32]. It is a generalization of the notion of first-order Markov chains.

Formally, first-order and higher-order Markov chains can be defined in a unified way as follows. Let ![]() $m \ge 2$. Then, an

$m \ge 2$. Then, an ![]() $(m-1)$th order Markov chain is a stochastic process

$(m-1)$th order Markov chain is a stochastic process ![]() $\{X_t : t=1, 2, \ldots\}$, where

$\{X_t : t=1, 2, \ldots\}$, where ![]() $t$ can be regarded as time and

$t$ can be regarded as time and ![]() $X_t$ is a random variable representing the state of a system at

$X_t$ is a random variable representing the state of a system at ![]() $t$ while taking values in the state space

$t$ while taking values in the state space ![]() $S=\{1, 2, \ldots, n\}$ with

$S=\{1, 2, \ldots, n\}$ with ![]() $n \ge 2$, such that

$n \ge 2$, such that

\begin{equation}

\begin{array}{l}

\Pr(X_{t+1}=i_1 | X_t=i_2,\ldots,X_{t-m+2}=i_m,\ldots,X_1=i_{t+1})\\

=\Pr(X_{t+1}=i_1 | X_t=i_2,\ldots,X_{t-m+2}=i_m)

\end{array}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{array}{l}

\Pr(X_{t+1}=i_1 | X_t=i_2,\ldots,X_{t-m+2}=i_m,\ldots,X_1=i_{t+1})\\

=\Pr(X_{t+1}=i_1 | X_t=i_2,\ldots,X_{t-m+2}=i_m)

\end{array}

\end{equation}for any ![]() $t \ge m-1$ and

$t \ge m-1$ and ![]() $i_1,i_2,\ldots,i_m,\ldots,i_{t+1} \in S$. In particular, this chain is called higher order when

$i_1,i_2,\ldots,i_m,\ldots,i_{t+1} \in S$. In particular, this chain is called higher order when ![]() $m \ge 3$. Incidentally, in this definition,

$m \ge 3$. Incidentally, in this definition, ![]() $X_{t+1}$ can be interpreted as the future state of the system,

$X_{t+1}$ can be interpreted as the future state of the system, ![]() $X_t$ the current state, and

$X_t$ the current state, and ![]() $X_{t-1}$ through

$X_{t-1}$ through ![]() $X_{t-m+2}$ the

$X_{t-m+2}$ the ![]() $m-2$ past states. By reason of the latter, an

$m-2$ past states. By reason of the latter, an ![]() $(m-1)$th order Markov chain is also said to have memory

$(m-1)$th order Markov chain is also said to have memory ![]() $m-2$ and, especially, to be memoryless if it is of first-order with

$m-2$ and, especially, to be memoryless if it is of first-order with ![]() $m=2$.

$m=2$.

In addition, throughout this article, a Markov chain is always assumed to be homogeneous, that is, the probability in (1.1) depends only on ![]() $i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_m$ but is independent of

$i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_m$ but is independent of ![]() $t$. Accordingly, we can write there

$t$. Accordingly, we can write there

which is called the transition probability from states ![]() $(i_2,\ldots,i_m)$ to

$(i_2,\ldots,i_m)$ to ![]() $i_1$. These probabilities form an

$i_1$. These probabilities form an ![]() $m$th order,

$m$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional tensor, which is denoted by

$n$ dimensional tensor, which is denoted by ![]() ${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ and called the transition tensor. Such a

${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ and called the transition tensor. Such a ![]() $\cal P$ is stochastic in the sense that

$\cal P$ is stochastic in the sense that ![]() $0 \le p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m} \le 1$ for all

$0 \le p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m} \le 1$ for all ![]() $i_1, i_2,\ldots,i_m \in S$ and

$i_1, i_2,\ldots,i_m \in S$ and  $\displaystyle \sum_{i_1 \in S} p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=1$ for all

$\displaystyle \sum_{i_1 \in S} p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=1$ for all ![]() $i_2, \ldots, i_m \in S$. For a first-order Markov chain,

$i_2, \ldots, i_m \in S$. For a first-order Markov chain, ![]() $\cal P$ is reduced to an

$\cal P$ is reduced to an ![]() $n \times n$ column stochastic transition matrix, denoted as

$n \times n$ column stochastic transition matrix, denoted as ![]() $P$ (or

$P$ (or ![]() $Q$) in this article. It should be mentioned that in the literature on first-order Markov chains, the transition matrix is typically taken to be row stochastic. In the higher-order case, however, the above “column stochastic” setting with the summation over the first index tends to be more convenient and hence is often adopted; see, for instance, [Reference Chang and Zhang3, Reference Gleich, Lim and Yu8, Reference Wu and Chu29] and the references therein.

$Q$) in this article. It should be mentioned that in the literature on first-order Markov chains, the transition matrix is typically taken to be row stochastic. In the higher-order case, however, the above “column stochastic” setting with the summation over the first index tends to be more convenient and hence is often adopted; see, for instance, [Reference Chang and Zhang3, Reference Gleich, Lim and Yu8, Reference Wu and Chu29] and the references therein.

For brevity, in what follows, we shall refer to a Markov chain of any order simply as a chain.

From the foregoing unified definition, it is natural to anticipate any result for higher-order chains to extend to the first-order case as well. The converse, nevertheless, is not so clear. Specifically, a key question is whether a problem regarding higher-order chains can be solved by way of first-order chains. As far as we can see, it has been a prevailing perception that the answer to this question is to a large extent affirmative. For one thing, it is well known that a higher-order chain can be associated with a first-order chain [Reference Doob5, Reference Hunter16]. Detail in this respect will be given in the next section.

The main thrust of this article is to shed light on the above key question. The importance of this question lies in the fact that it significantly impacts the methodology of examining higher-order chains. Even though such chains have lately been the focus of many studies, see [Reference Chang and Zhang3, Reference Culp, Pearson and Zhang4, Reference Geiger7, Reference Gleich, Lim and Yu8, Reference Hu and Qi15, Reference Li and Zhang23, Reference Li and Ng24, Reference Wu and Chu29] and the references therein, this question remains open to a great degree. In light of this situation, we shall provide, for the first time, a rather comprehensive answer by synthesizing relevant recent results from [Reference Han, Wang and Xu9–Reference Han and Xu12]. We shall also give necessary examples to illustrate the results. In particular, we shall highlight the primary differences between higher-order and first-order chains. These differences, to the best of our knowledge, have yet to be presented in such a collective and systematic way.

To help verify the examples in this article or related works in [Reference Han, Wang and Xu9–Reference Han and Xu12], the reader may use the HOMC MATLAB package [Reference Xu31], which is publicly available at

2. Reduced first-order chains

Let ![]() $m \ge 3$. Suppose that

$m \ge 3$. Suppose that ![]() $X=\{X_t : t=1, 2, \ldots\}$ is an

$X=\{X_t : t=1, 2, \ldots\}$ is an ![]() $(m-1)$th order chain on state space

$(m-1)$th order chain on state space ![]() $S=\{1, 2, \ldots, n\}$ whose transition tensor is

$S=\{1, 2, \ldots, n\}$ whose transition tensor is ![]() ${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$. It is well known [Reference Doob5, Reference Hunter16] that this higher-order chain

${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$. It is well known [Reference Doob5, Reference Hunter16] that this higher-order chain ![]() $X$ can be associated with a first-order chain as follows.

$X$ can be associated with a first-order chain as follows.

First, define the set ![]() $T$ of multi-indices of length

$T$ of multi-indices of length ![]() $m-1$, ordered by linear indexing [Reference Martin, Shafer and Larue26], as

$m-1$, ordered by linear indexing [Reference Martin, Shafer and Larue26], as

Note that the cardinality of ![]() $T$ is

$T$ is ![]() $N=n^{m-1}$. Next, for

$N=n^{m-1}$. Next, for ![]() $t \ge m-1$, introduce vector-valued random variables

$t \ge m-1$, introduce vector-valued random variables

Let us denote ![]() $Y_t=i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}$ when

$Y_t=i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}$ when ![]() $X_t=i_1, X_{t-1}=i_2, \ldots, X_{t-m+2}=i_{m-1}$. Then, the vector-valued stochastic process

$X_t=i_1, X_{t-1}=i_2, \ldots, X_{t-m+2}=i_{m-1}$. Then, the vector-valued stochastic process ![]() $Y=\{Y_t : t=m-1, m, \ldots\}$ is a first-order chain on state space

$Y=\{Y_t : t=m-1, m, \ldots\}$ is a first-order chain on state space ![]() $T$, which we shall refer to as the reduced first-order chain obtained from

$T$, which we shall refer to as the reduced first-order chain obtained from ![]() $X$.

$X$.

Denote the ![]() $N \times N$ transition matrix of

$N \times N$ transition matrix of ![]() $Y$ by

$Y$ by ![]() $Q$. It is more convenient to write

$Q$. It is more convenient to write

in multi-index form with ![]() $i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}, j_2j_3\ldots j_m \in T$. Then, the entries of

$i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}, j_2j_3\ldots j_m \in T$. Then, the entries of ![]() $Q$ can be expressed as, see [Reference Han and Xu12],

$Q$ can be expressed as, see [Reference Han and Xu12],

\begin{equation*}q_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}, j_2j_3\ldots j_m}=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}j_m}, & ~i_\ell=j_\ell, ~\ell=2, 3, \ldots, m-1;\\

0, & ~{\rm otherwise.}

\end{array}\right.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}q_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}, j_2j_3\ldots j_m}=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}j_m}, & ~i_\ell=j_\ell, ~\ell=2, 3, \ldots, m-1;\\

0, & ~{\rm otherwise.}

\end{array}\right.\end{equation*} In addition, ![]() $p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}$ is located in

$p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}$ is located in ![]() $Q$ on row

$Q$ on row

and column

For a third-order chain with two states, that is, ![]() $m=4$ and

$m=4$ and ![]() $n=2$, for example, we have

$n=2$, for example, we have

and

\begin{equation}

Q=\left[\begin{array}{cccccccc}

p_{1111} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{1112} & 0 & 0 & 0\\

p_{2111} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{2112} & 0 & 0 & 0\\

0 & p_{1211} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{1212} & 0 & 0\\

0 & p_{2211} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{2212} & 0 & 0\\

0 & 0 & p_{1121} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{1122} & 0\\

0 & 0 & p_{2121} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{2122} & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & p_{1221} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{1222}\\

0 & 0 & 0 & p_{2221} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{2222}

\end{array}\right].

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

Q=\left[\begin{array}{cccccccc}

p_{1111} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{1112} & 0 & 0 & 0\\

p_{2111} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{2112} & 0 & 0 & 0\\

0 & p_{1211} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{1212} & 0 & 0\\

0 & p_{2211} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{2212} & 0 & 0\\

0 & 0 & p_{1121} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{1122} & 0\\

0 & 0 & p_{2121} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{2122} & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & p_{1221} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{1222}\\

0 & 0 & 0 & p_{2221} & 0 & 0 & 0 & p_{2222}

\end{array}\right].

\end{equation} In particular, ![]() $Q$ coincides with the transition matrix of

$Q$ coincides with the transition matrix of ![]() $X$ when this chain is first order, that is, in the special case

$X$ when this chain is first order, that is, in the special case ![]() $m=2$.

$m=2$.

Speaking of the connection between a higher-order chain and its reduced first-order chain, we mention here the opinion of Joseph Doob, who has left a profound, lasting impact on the field of stochastic processes. In the seminal monograph [Reference Doob5], he stated that “the generalization (from simple Markov processes to multiple ones) is not very significant, because the (vector) process with random variables ![]() $\{\hat{x}_n\}$,

$\{\hat{x}_n\}$, ![]() ${\hat x}_n=(x_n, \ldots, x_{n+v-1})$ (i.e.,

${\hat x}_n=(x_n, \ldots, x_{n+v-1})$ (i.e., ![]() $Y_t$ in our notation) has the Markov property ... Thus multiple Markov processes can be reduced to simple ones at the small expense of going to vector-valued random variables.” This appears to suggest that problems regarding a higher-order chain can be solved through its reduced first-order chain.

$Y_t$ in our notation) has the Markov property ... Thus multiple Markov processes can be reduced to simple ones at the small expense of going to vector-valued random variables.” This appears to suggest that problems regarding a higher-order chain can be solved through its reduced first-order chain.

From what we can gather in literature, different voices have been few and far between. The most notable argument can be found in the classic treatise [Reference Iosifescu17] by Marius Iosifescu, in which he pointed out first that “In this way with any multiple Markov chain one can associate a simple Markov chain. This is the origin of the rooted prejudice that the study of multiple Markov chains reduces to that of simple ones.” and then cited the following example: State ![]() $i$ can be recurrent in a second-order chain but

$i$ can be recurrent in a second-order chain but ![]() $ij \in T$ is not recurrent in the reduced first-order chain for any

$ij \in T$ is not recurrent in the reduced first-order chain for any ![]() $j$. This example, albeit useful, falls short to adequately address why it is a “prejudice” to investigate higher-order chains by reducing them to first-order chains, that is, to fully address the key question as raised in the introductory section. Having laid out the notion of reduced first-order chains, we can now rephrase this key questions as:

$j$. This example, albeit useful, falls short to adequately address why it is a “prejudice” to investigate higher-order chains by reducing them to first-order chains, that is, to fully address the key question as raised in the introductory section. Having laid out the notion of reduced first-order chains, we can now rephrase this key questions as:

Question 2.1. Can a higher-order chain be studied via its reduced first-order chain?

This formal statement clarifies what the first-order chain is in the previously stated approach “by way of first-order chains.” It is also easier for us to refer to this question in the rest of this article.

3.  $k$-step transition and ever-reaching probabilities

$k$-step transition and ever-reaching probabilities

Let us begin here with some background material.

For ![]() $m, n \ge 2$, let

$m, n \ge 2$, let ![]() ${\cal A}=[a_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ and

${\cal A}=[a_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ and ![]() ${\cal B}=[b_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ be both

${\cal B}=[b_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ be both ![]() $m$th order,

$m$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional tensors. The tensor product

$n$ dimensional tensors. The tensor product ![]() ${\cal A} \boxtimes {\cal B}$ is introduced in [Reference Han and Xu10, Reference Han and Xu12] as an

${\cal A} \boxtimes {\cal B}$ is introduced in [Reference Han and Xu10, Reference Han and Xu12] as an ![]() $m$th order,

$m$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional tensor

$n$ dimensional tensor ![]() ${\cal C}=[c_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ such that

${\cal C}=[c_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ such that

\begin{equation*}c_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\sum_{j=1}^n a_{i_1ji_2\ldots i_{m-1}}b_{ji_2\ldots i_m}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}c_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\sum_{j=1}^n a_{i_1ji_2\ldots i_{m-1}}b_{ji_2\ldots i_m}\end{equation*}for any ![]() $1 \le i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_m \le n$. When

$1 \le i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_m \le n$. When ![]() $m=2$, in particular,

$m=2$, in particular, ![]() ${\cal A}\boxtimes {\cal B}$ reduces to a matrix multiplication. Note, however, that the

${\cal A}\boxtimes {\cal B}$ reduces to a matrix multiplication. Note, however, that the ![]() $\boxtimes$ product is in general not associative whenever

$\boxtimes$ product is in general not associative whenever ![]() $m \ge 3$. As a side remark, the product

$m \ge 3$. As a side remark, the product ![]() ${\cal A}\boxtimes {\cal B}$ is originally written as

${\cal A}\boxtimes {\cal B}$ is originally written as ![]() ${\cal B} \boxtimes {\cal A}$ in [Reference Han and Xu10]. The current notation is consistent with the special case when

${\cal B} \boxtimes {\cal A}$ in [Reference Han and Xu10]. The current notation is consistent with the special case when ![]() $\cal A$ and

$\cal A$ and ![]() $\cal B$ are matrices.

$\cal B$ are matrices.

For ![]() $k=2, 3, \ldots$, the

$k=2, 3, \ldots$, the ![]() $k$th power of the

$k$th power of the ![]() $m$th order,

$m$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional tensor

$n$ dimensional tensor ![]() $\cal A$ is defined recursively by

$\cal A$ is defined recursively by

with ![]() ${\cal A}^1=\cal A$. By convention,

${\cal A}^1=\cal A$. By convention, ![]() ${\cal A}^0={\cal I}=[\delta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$, the

${\cal A}^0={\cal I}=[\delta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$, the ![]() $m$th order,

$m$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional identity tensor whose entries satisfy

$n$ dimensional identity tensor whose entries satisfy

\begin{equation*}\delta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

1, & i_1=i_2;\\

0, & {\rm otherwise.}

\end{array}\right.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\delta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

1, & i_1=i_2;\\

0, & {\rm otherwise.}

\end{array}\right.\end{equation*} It is easy to see that ![]() ${\cal I}\boxtimes {\cal A}=\cal A$, but in general

${\cal I}\boxtimes {\cal A}=\cal A$, but in general ![]() ${\cal A}\boxtimes {\cal I} \ne \cal A$.

${\cal A}\boxtimes {\cal I} \ne \cal A$.

Besides the above, the mode-![]() $k$ matricization of the

$k$ matricization of the ![]() $m$th order,

$m$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional tensor

$n$ dimensional tensor ![]() $\cal A$ is defined to be an

$\cal A$ is defined to be an ![]() $n$ by

$n$ by ![]() $N$, with

$N$, with ![]() $N=n^{m-1}$, matrix that has the mode-

$N=n^{m-1}$, matrix that has the mode-![]() $k$ fibers

$k$ fibers ![]() ${\cal A}(i_1, \ldots, i_{k-1}, :, i_{k+1}, \ldots, i_m)$ as columns. These fibers are arranged in the linear indexing order of

${\cal A}(i_1, \ldots, i_{k-1}, :, i_{k+1}, \ldots, i_m)$ as columns. These fibers are arranged in the linear indexing order of ![]() $i_1\ldots i_{k-1}i_{k+1}\ldots i_m$ [Reference Kolda and Bader20]. Especially, the mode-

$i_1\ldots i_{k-1}i_{k+1}\ldots i_m$ [Reference Kolda and Bader20]. Especially, the mode-![]() $1$ matricization of

$1$ matricization of ![]() $\cal A$ is formed by arranging

$\cal A$ is formed by arranging ![]() ${\cal A}(:,:,i_3, \ldots, i_m)$, that is, the frontal slices of

${\cal A}(:,:,i_3, \ldots, i_m)$, that is, the frontal slices of ![]() $\cal A$, side by side via the linear indexing order of

$\cal A$, side by side via the linear indexing order of ![]() $i_3\ldots i_m$.

$i_3\ldots i_m$.

As shown in [Reference Han, Wang and Xu9, Reference Han and Xu10, Reference Han and Xu12], the ![]() $\boxtimes$ product plays a crucial role in the study of higher-order chains. It can be used to formulate various important quantities such as

$\boxtimes$ product plays a crucial role in the study of higher-order chains. It can be used to formulate various important quantities such as ![]() $k$-step transition probabilities and ever-reaching probabilities, which we shall describe next.

$k$-step transition probabilities and ever-reaching probabilities, which we shall describe next.

Back to the ![]() $(m-1)$th order chain

$(m-1)$th order chain ![]() $X$ with state space

$X$ with state space ![]() $S=\{1, 2, \ldots, n\}$ and transition tensor

$S=\{1, 2, \ldots, n\}$ and transition tensor ![]() ${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$. Denote

${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$. Denote  ${\cal P}^k=[p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$. Then,

${\cal P}^k=[p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$. Then,  $p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}$ is the

$p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}$ is the ![]() $k$-step transition probability from states

$k$-step transition probability from states ![]() $(i_2, \ldots, i_m)$ to

$(i_2, \ldots, i_m)$ to ![]() $i_1$ [Reference Han, Wang and Xu9], that is,

$i_1$ [Reference Han, Wang and Xu9], that is,

\begin{equation*}p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\Pr(X_{t+k}=i_1 | X_t=i_2, \ldots, X_{t-m+2}=i_m).\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\Pr(X_{t+k}=i_1 | X_t=i_2, \ldots, X_{t-m+2}=i_m).\end{equation*} Accordingly, ![]() ${\cal P}^k$ is called the

${\cal P}^k$ is called the ![]() $k$-step transition tensor.

$k$-step transition tensor.

Continuing, let

be the random variable of the first passage time from states ![]() $(i_2, \ldots, i_m)$ to

$(i_2, \ldots, i_m)$ to ![]() $i_1$. Denote the probability for this passage to happen at

$i_1$. Denote the probability for this passage to happen at ![]() $j=k$ by

$j=k$ by

\begin{equation*}f^{[k]}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\Pr(\eta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=k).\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}f^{[k]}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\Pr(\eta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=k).\end{equation*} In the special case when ![]() $k=1$,

$k=1$,  $f^{[1]}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}$. Denote

$f^{[1]}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}$. Denote  ${\cal F}^{[k]}=[f^{[k]}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$, which is called the

${\cal F}^{[k]}=[f^{[k]}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$, which is called the ![]() $k$-step first passage time probability tensor. It is known [Reference Han, Wang and Xu9] that

$k$-step first passage time probability tensor. It is known [Reference Han, Wang and Xu9] that

\begin{equation}

f^{[k+1]}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\sum_{j \in S, j \ne i_1}f^{[k]}_{i_1ji_2\ldots i_{m-1}}p_{ji_2\ldots i_m}, ~k=1, 2, \ldots,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

f^{[k+1]}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\sum_{j \in S, j \ne i_1}f^{[k]}_{i_1ji_2\ldots i_{m-1}}p_{ji_2\ldots i_m}, ~k=1, 2, \ldots,

\end{equation} To express (3.2) via the ![]() $\boxtimes$ product, for any

$\boxtimes$ product, for any ![]() $m$th order,

$m$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional tensor

$n$ dimensional tensor ![]() ${\cal A}=[a_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$, let us define the diagonal tensor

${\cal A}=[a_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$, let us define the diagonal tensor  ${\cal A}_d=[a^{(d)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ satisfying

${\cal A}_d=[a^{(d)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ satisfying

\begin{equation*}a^{(d)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

a_{i_1i_1i_3\ldots i_m}, & i_1=i_2;\\

0, & {\rm otherwise}.

\end{array}\right.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}a^{(d)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

a_{i_1i_1i_3\ldots i_m}, & i_1=i_2;\\

0, & {\rm otherwise}.

\end{array}\right.\end{equation*}Clearly, (3.2) can now be written simply as

\begin{equation*}{\cal F}^{[k+1]}=({\cal F}^{[k]}-{\cal F}^{[k]}_d)\boxtimes \cal P.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal F}^{[k+1]}=({\cal F}^{[k]}-{\cal F}^{[k]}_d)\boxtimes \cal P.\end{equation*} The probability of ever reaching ![]() $i_1$ from

$i_1$ from ![]() $(i_2, \ldots, i_m)$ is given by

$(i_2, \ldots, i_m)$ is given by

\begin{equation*}f_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\Pr(\eta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m} \lt \infty)=\sum_{k=1}^\infty f^{[k]}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m},\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}f_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=\Pr(\eta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m} \lt \infty)=\sum_{k=1}^\infty f^{[k]}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m},\end{equation*}or in tensor form, the ever-reaching probability tensor ![]() ${\cal F}=[f_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ can be expressed as

${\cal F}=[f_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$ can be expressed as

\begin{equation*}{\cal F}=\sum_{k=1}^\infty {\cal F}^{[k]}.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal F}=\sum_{k=1}^\infty {\cal F}^{[k]}.\end{equation*} These results regarding ![]() $k$-step transition probabilities and ever-reaching probabilities remain valid for first-order chains. In the first-order case, they can also be written as

$k$-step transition probabilities and ever-reaching probabilities remain valid for first-order chains. In the first-order case, they can also be written as  $P^k=[p^{(k)}_{ij}]$, the

$P^k=[p^{(k)}_{ij}]$, the ![]() $k$-step transition matrix, and

$k$-step transition matrix, and ![]() $F=[f_{ij}]$, the ever-reaching probability matrix, respectively [Reference Hunter16, Reference Kemeny and Snell19].

$F=[f_{ij}]$, the ever-reaching probability matrix, respectively [Reference Hunter16, Reference Kemeny and Snell19].

In passing, we also give one example of the mode-![]() $1$ matricization of the transition tensor

$1$ matricization of the transition tensor ![]() $\cal P$, denoted by

$\cal P$, denoted by ![]() $P$. Take a third-order chain with two states just as the one in the previous section, that is,

$P$. Take a third-order chain with two states just as the one in the previous section, that is, ![]() $m=4$ and

$m=4$ and ![]() $n=2$. Then,

$n=2$. Then,

\begin{equation*}P=\left[\begin{array}{cc|cc|cc|cc}

p_{1111} & p_{1211} & p_{1121} & p_{1221} & p_{1112} & p_{1212} & p_{1122} & p_{1222}\\

p_{2111} & p_{2211} & p_{2121} & p_{2221} & p_{2112} & p_{2212} & p_{2122} & p_{2222}

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}P=\left[\begin{array}{cc|cc|cc|cc}

p_{1111} & p_{1211} & p_{1121} & p_{1221} & p_{1112} & p_{1212} & p_{1122} & p_{1222}\\

p_{2111} & p_{2211} & p_{2121} & p_{2221} & p_{2112} & p_{2212} & p_{2122} & p_{2222}

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*} Clearly, ![]() $P$ coincides with the transition matrix when the chain is first order. For

$P$ coincides with the transition matrix when the chain is first order. For ![]() $k=0, 1, \ldots$, the mode-

$k=0, 1, \ldots$, the mode-![]() $1$ matricization of

$1$ matricization of ![]() ${\cal P}^k$ is formed in a similar way and denoted by

${\cal P}^k$ is formed in a similar way and denoted by ![]() $P^{(k)}$.

$P^{(k)}$.

In view of Question 2.1, we now raise the question of whether the ![]() $k$-step transition tensor or ever-reaching probability tensor of a higher-order chain can be obtained from their respective counterpart of the reduced first-order chain. Given an

$k$-step transition tensor or ever-reaching probability tensor of a higher-order chain can be obtained from their respective counterpart of the reduced first-order chain. Given an ![]() $(m-1)$th order,

$(m-1)$th order, ![]() $m \ge 3$, chain with transition tensor

$m \ge 3$, chain with transition tensor ![]() $\cal P$, it is shown in [Reference Han and Xu12] that

$\cal P$, it is shown in [Reference Han and Xu12] that

where ![]() $P^{(k)}$ and

$P^{(k)}$ and ![]() $P^{(0)}$ stand for the mode-

$P^{(0)}$ stand for the mode-![]() $1$ matricizations of

$1$ matricizations of ![]() ${\cal P}^k$ and

${\cal P}^k$ and ![]() ${\cal P}^0={\cal I}$, respectively, and

${\cal P}^0={\cal I}$, respectively, and ![]() $Q^k$ denotes the

$Q^k$ denotes the ![]() $k$-step transition matrix of the associated reduced first-order chain. The formula (3.3) provides a connection between the

$k$-step transition matrix of the associated reduced first-order chain. The formula (3.3) provides a connection between the ![]() $k$-step transition probabilities of the higher-order chain and those of its reduced first-order chain. It is worth noting, nevertheless, that these

$k$-step transition probabilities of the higher-order chain and those of its reduced first-order chain. It is worth noting, nevertheless, that these ![]() $k$-step transition probabilities of the higher-order case can be obtained directly via

$k$-step transition probabilities of the higher-order case can be obtained directly via ![]() ${\cal P}^k$ without resorting to

${\cal P}^k$ without resorting to ![]() $Q^k$.

$Q^k$.

The question concerning ever-reaching probabilities will be considered in the next section after the introduction of the notion of ergodicity.

4. Irreducibility, ergodicity, and regularity

Let us begin with several well-known concepts for first-order chains [Reference Hunter16, Reference Kemeny and Snell19]. Suppose that ![]() $P=[p_{ij}]$ is the transition matrix of a first-order chain on state space

$P=[p_{ij}]$ is the transition matrix of a first-order chain on state space ![]() $S$. Then:

$S$. Then:

• The chain is irreducible if for any

$\emptyset \ne K \subsetneq S$, there exists

$\emptyset \ne K \subsetneq S$, there exists  $p_{ij} \gt 0$ for some

$p_{ij} \gt 0$ for some  $i \in K$ and some

$i \in K$ and some  $j \in K^c$. In matrix theory, its transition matrix

$j \in K^c$. In matrix theory, its transition matrix  $P$ is also said to be irreducible. The chain is said to be reducible if it is not irreducible.

$P$ is also said to be irreducible. The chain is said to be reducible if it is not irreducible.• The chain is ergodic if for any

$i, j \in S$, there exists

$i, j \in S$, there exists  $k \ge 1$, which may depend on

$k \ge 1$, which may depend on  $i$ and

$i$ and  $j$, such that

$j$, such that  $p^{(k)}_{ij} \gt 0$.

$p^{(k)}_{ij} \gt 0$.• The chain is regular if there exists some

$k \ge 1$ such that

$k \ge 1$ such that  $p^{(k)}_{ij} \gt 0$ for all

$p^{(k)}_{ij} \gt 0$ for all  $i, j \in S$, that is,

$i, j \in S$, that is,  $P^k \gt 0$. In matrix theory, such

$P^k \gt 0$. In matrix theory, such  $P$ is said to be primitive.

$P$ is said to be primitive.

For a first-order chain, it is well known [Reference Horn and Johnson14] that irreducibility is equivalent to ergodicity.

The above definitions can be extended as follows to a higher-order chain on state space ![]() $S$, whose transition tensor is

$S$, whose transition tensor is ![]() ${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$.

${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$.

• The chain is said to be irreducible if for each

$\emptyset \ne K \subsetneq S$, there exists

$\emptyset \ne K \subsetneq S$, there exists  $p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m} \gt 0$ for some

$p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m} \gt 0$ for some  $i_1 \in K$ and some

$i_1 \in K$ and some  $i_2,\ldots,i_m \in K^c$ [Reference Li and Ng24].

$i_2,\ldots,i_m \in K^c$ [Reference Li and Ng24].• The chain is said to be ergodic if for any

$i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_m \in S$, there exists

$i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_m \in S$, there exists  $k \ge 1$, which may depend on

$k \ge 1$, which may depend on  $i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_m$, such that

$i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_m$, such that  $p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m} \gt 0$ [Reference Han, Wang and Xu9].

$p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m} \gt 0$ [Reference Han, Wang and Xu9].• The chain is said to be regular if there exists

$k \ge 1$ such that for any

$k \ge 1$ such that for any  $i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_m \in S$,

$i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_m \in S$,  $p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m} \gt 0$, that is,

$p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m} \gt 0$, that is,  ${\cal P}^k \gt 0$ [Reference Han and Xu12].

${\cal P}^k \gt 0$ [Reference Han and Xu12].

Unlike the first-order case, for a higher-order chain, ergodicity is a stronger condition than irreducibility [Reference Han, Wang and Xu9], that is, an ergodic higher-order chain must be irreducible, but the converse is not true in general. Consider, for example, a second-order chain with three states and transition tensor

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 0 & 0\\

0 & 1 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & 0 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 1 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & 0 & 1\\

0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 1 & 0

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 0 & 0\\

0 & 1 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & 0 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 1 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & 0 & 1\\

0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 1 & 0

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*} This chain is irreducible, but not ergodic since  $p^{(k)}_{2i_2i_3}=0$ for all

$p^{(k)}_{2i_2i_3}=0$ for all ![]() $1 \le i_2, i_3 \le 3$ and

$1 \le i_2, i_3 \le 3$ and ![]() $k \ge 2$.

$k \ge 2$.

In order to guarantee the mean first passage times to be well defined and finite, for example, ergodicity is an important condition no matter the order of a chain [Reference Han and Xu10, Reference Kemeny and Snell19]. Following Question 2.1, it is natural to ask whether the mean first passage times of a higher-order chain can be obtained from those of its reduced first-order chain. First and foremost, however, it makes sense to ask whether ergodicity of a higher-order chain carries over to its reduced first-order chain. The answer to the latter question, unfortunately, turns out to be negative as shown by the following example.

Let ![]() ${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2i_3}]$ be the transition tensor of a second-order chain of three states such that all

${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2i_3}]$ be the transition tensor of a second-order chain of three states such that all ![]() $p_{i_1i_2i_3}$ are positive except

$p_{i_1i_2i_3}$ are positive except ![]() $p_{311}=p_{312}=p_{313}=0$. Let us simply take

$p_{311}=p_{312}=p_{313}=0$. Let us simply take

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)={\cal P}(:,:,2)={\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1/2 & 1/3 & 1/3\\

1/2 & 1/3 & 1/3\\

0 & 1/3 & 1/3

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)={\cal P}(:,:,2)={\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1/2 & 1/3 & 1/3\\

1/2 & 1/3 & 1/3\\

0 & 1/3 & 1/3

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*} Since ![]() ${\cal P}^2 \gt 0$, this chain is regular and thus is also ergodic. Its reduced first-order chain has transition matrix

${\cal P}^2 \gt 0$, this chain is regular and thus is also ergodic. Its reduced first-order chain has transition matrix

\begin{equation*}Q=\left[\begin{array}{ccccccccc}

1/2 & 0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0 \\

1/2 & 0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 \\

0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 \\

0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 \\

0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 \\

0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3

\end{array}\right],\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}Q=\left[\begin{array}{ccccccccc}

1/2 & 0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0 \\

1/2 & 0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 \\

0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 \\

0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 \\

0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 \\

0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3

\end{array}\right],\end{equation*}which is clearly not even irreducible due to its third row of all zeros. Hence, the reduced first-order chain is not ergodic.

The above example also justifies that, like ergodicity, regularity does not carry over either from a higher-order chain to its reduced first-order chain.

What this example demonstrates is, in fact, the first obstacle to studying a higher-order chain through its reduced first-order chain. We shall demonstrate later in Section 6 that other difficulties may arise even if ergodicity or regularity happens to carry over to the reduced first-order chain. The issue of mean first passage times will be addressed there too.

Returning to the question raised in the preceding section concerning the relationship between the ever-reaching probabilities of a higher-order chain and those of its reduced first-order chain, we consider below a second-order chain with four states and transition tensor

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

1/2 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 0 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 1 & 0 & 1\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 0 & 1/2 & 1\\

0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 1/2 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 0 & 1/2 & 0

\end{array}\right],\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

1/2 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 0 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 1 & 0 & 1\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 0 & 1/2 & 1\\

0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 1/2 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 0 & 1/2 & 0

\end{array}\right],\end{equation*} \begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 1 & 0 & 1\\

1 & 0 & 1/2 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,4)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 1 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1/2\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1/2

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 1 & 0 & 1\\

1 & 0 & 1/2 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,4)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 1 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1/2\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1/2

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*} It is easy to verify ![]() ${\cal P}^{10} \gt 0$. Clearly, this chain is regular and, consequently, ergodic. It is shown in [Reference Han and Xu10] that for such an ergodic chain, its ever-reaching probabilities

${\cal P}^{10} \gt 0$. Clearly, this chain is regular and, consequently, ergodic. It is shown in [Reference Han and Xu10] that for such an ergodic chain, its ever-reaching probabilities ![]() $f_{i_1i_2i_3}=1$ for all

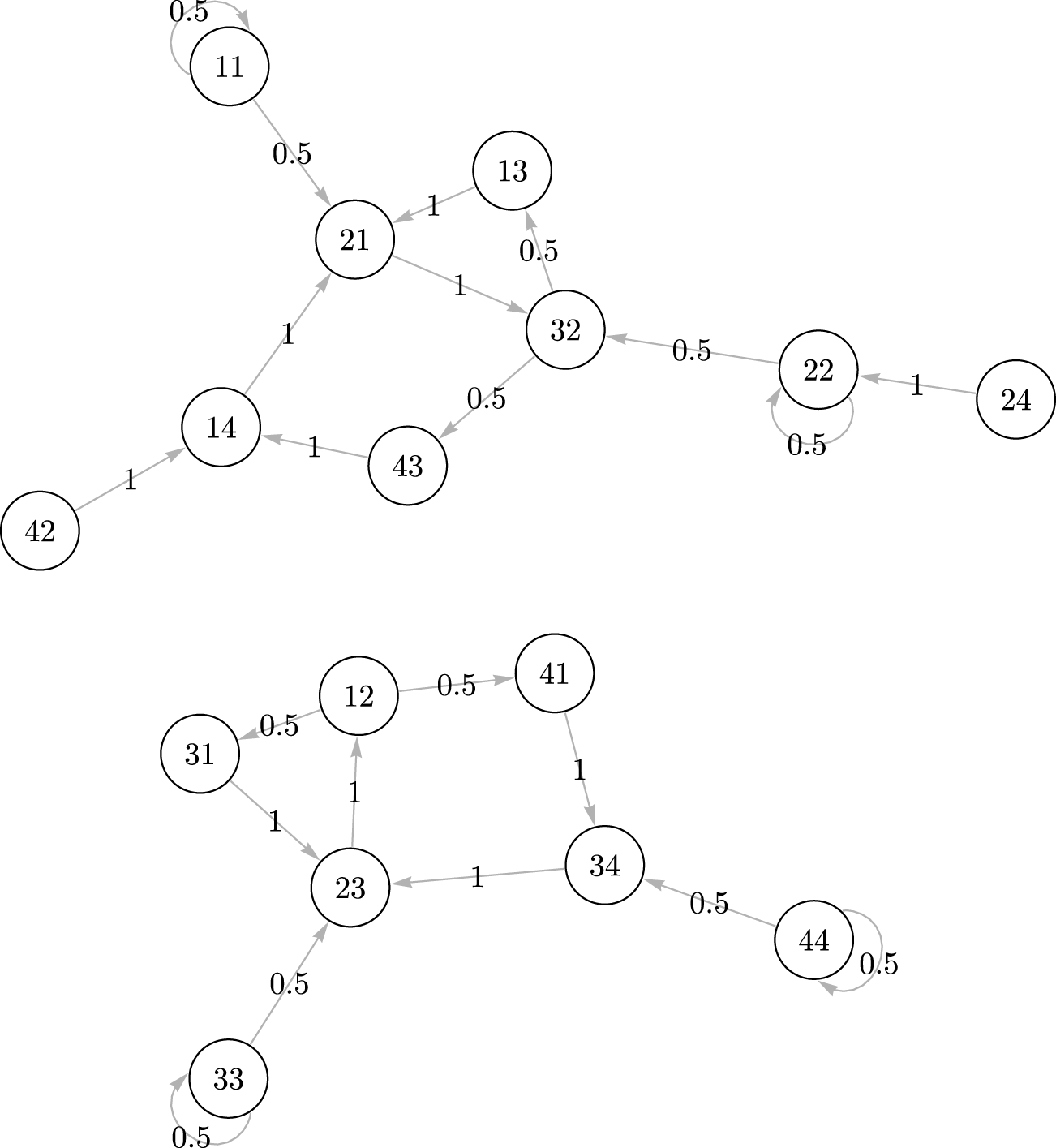

$f_{i_1i_2i_3}=1$ for all ![]() $1 \le i_1, i_2, i_3 \le 4$. The associated reduced first-order chain, however, exhibits a noticeably different dynamics as illustrated by the digraph in Figure 1 that represents its transition matrix

$1 \le i_1, i_2, i_3 \le 4$. The associated reduced first-order chain, however, exhibits a noticeably different dynamics as illustrated by the digraph in Figure 1 that represents its transition matrix ![]() $Q$. Starting, for example, from state

$Q$. Starting, for example, from state ![]() $12$, the reduced first-order chain has zero probability of reaching state

$12$, the reduced first-order chain has zero probability of reaching state ![]() $11$. This, nevertheless, does not lead to the conclusion that state

$11$. This, nevertheless, does not lead to the conclusion that state ![]() $1$ cannot be reached from states

$1$ cannot be reached from states ![]() $(1, 2)$ in the second-order chain since

$(1, 2)$ in the second-order chain since ![]() $f_{112}=1$. This illustrates that the answer to Question 2.1 is negative when dealing with the problem of ever-reaching probabilities.

$f_{112}=1$. This illustrates that the answer to Question 2.1 is negative when dealing with the problem of ever-reaching probabilities.

Figure 1. Digraph of reduced first-order chain.

It is quite straightforward, though a bit tedious, to show that the ever-reaching probabilities of a higher-order chain cannot be obtained via those of its reduced first-order chain in a similar manner as neat as (3.3). Again, we consider the general third-order chain with two states in Section 2. Let  $G^{[2]}=[g^{[2]}_{i_1i_2i_3, j_1j_2j_3}]$ be the

$G^{[2]}=[g^{[2]}_{i_1i_2i_3, j_1j_2j_3}]$ be the ![]() $2$-step first passage time probability matrix of the reduced first-order chain. Then, it is easy to verify that

$2$-step first passage time probability matrix of the reduced first-order chain. Then, it is easy to verify that

\begin{equation}

g^{[2]}_{i_1i_2i_3, j_1j_2j_3}=p_{i_1i_2i_3j_2}p_{i_2i_3j_2j_3}, ~i_1i_2i_3, j_1j_2j_3 \in T,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

g^{[2]}_{i_1i_2i_3, j_1j_2j_3}=p_{i_1i_2i_3j_2}p_{i_2i_3j_2j_3}, ~i_1i_2i_3, j_1j_2j_3 \in T,

\end{equation}provided ![]() $j_1=i_3$ and either

$j_1=i_3$ and either ![]() $i_1 \ne i_2$ or

$i_1 \ne i_2$ or ![]() $i_2 \ne i_3$ or

$i_2 \ne i_3$ or ![]() $i_3 \ne j_2$. As a comparison, it follows from (2.1) that

$i_3 \ne j_2$. As a comparison, it follows from (2.1) that

\begin{equation}

q^{(2)}_{i_1i_2i_3, i_3j_2j_3}=p_{i_1i_2i_3j_2}p_{i_2i_3j_2j_3}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

q^{(2)}_{i_1i_2i_3, i_3j_2j_3}=p_{i_1i_2i_3j_2}p_{i_2i_3j_2j_3}.

\end{equation}Clearly, (4.1) is much more complicated than (4.2). This, together with the preceding example as illustrated in Figure 1, offers an additional perspective showing that the answer to Question 2.1 is negative as far as ever-reaching probabilities are concerned.

5. Classification of states

Given a first-order chain with transition matrix ![]() $P=[p_{ij}]$ and ever-reaching probability matrix

$P=[p_{ij}]$ and ever-reaching probability matrix ![]() $F=[f_{ij}]$, it is well known [Reference Hunter16] that:

$F=[f_{ij}]$, it is well known [Reference Hunter16] that:

• A state

$i$ is recurrent if

$i$ is recurrent if  $f_{ii}=1$. A state

$f_{ii}=1$. A state  $i$ is recurrent iff

$i$ is recurrent iff  $\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{ii}=\infty.$

$\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{ii}=\infty.$• A state

$i$ is transient if

$i$ is transient if  $f_{ii} \lt 1$. A state

$f_{ii} \lt 1$. A state  $i$ is transient iff

$i$ is transient iff  $\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{ii} \lt \infty.$

$\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{ii} \lt \infty.$• A state

$i$ is absorbing if

$i$ is absorbing if  $p_{ii}=1$.

$p_{ii}=1$.

The example that is cited by [Reference Iosifescu17], see the introductory section, indicates that the states of a higher-order chain cannot be classified according to the states of its reduced first-order chain. A more complete classification scheme for states of higher-order chains is recently proposed in [Reference Han and Xu11]. Here is a brief description of this scheme. Consider a higher-order chain whose state space is ![]() $S$, transition tensor is

$S$, transition tensor is ![]() ${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$, and ever-reaching probability tensor is

${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$, and ever-reaching probability tensor is ![]() ${\cal F}=[f_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$. Then,

${\cal F}=[f_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$. Then,

• A state

$i$ is said to be recurrent if

$i$ is said to be recurrent if  $f_{iii_3\ldots i_m}=1$ for all

$f_{iii_3\ldots i_m}=1$ for all  $i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$. If state

$i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$. If state  $i$ is recurrent, then

$i$ is recurrent, then  $\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m}=\infty$ for all

$\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m}=\infty$ for all  $i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$.

$i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$.• A state

$i$ is said to be transient if

$i$ is said to be transient if  $f_{iii_3\ldots i_m} \lt 1$ for some

$f_{iii_3\ldots i_m} \lt 1$ for some  $i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$. Especially, a state

$i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$. Especially, a state  $i$ is said to be fully transient if

$i$ is said to be fully transient if  $f_{iii_3\ldots i_m} \lt 1$ for any

$f_{iii_3\ldots i_m} \lt 1$ for any  $i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$. When state

$i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$. When state  $i$ is fully transient,

$i$ is fully transient,  $\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m} \lt \infty$ for all

$\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m} \lt \infty$ for all  $i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$.

$i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$.• A state

$i$ is said to be absorbing if

$i$ is said to be absorbing if  $p_{iii_3\ldots i_m}=1$ for all

$p_{iii_3\ldots i_m}=1$ for all  $i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$.

$i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$.

These results from [Reference Han and Xu11] seem to be parallel to their first-order counterparts. We, however, point out some differences between the higher-order and first-order cases. Specifically, for a higher-order chain:

• There may exist the scenario where a state

$i$ is transient but not fully transient, that is,

$i$ is transient but not fully transient, that is,  $f_{iii_3\ldots i_m}$ is smaller than

$f_{iii_3\ldots i_m}$ is smaller than  $1$ for some

$1$ for some  $i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$ but is equal to

$i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$ but is equal to  $1$ for other

$1$ for other  $i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$. This is indeed at the center of the key differences between the higher-order and first-order chains when it comes to the classification of states.

$i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$. This is indeed at the center of the key differences between the higher-order and first-order chains when it comes to the classification of states.• The condition of whether

$\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m}$ is infinite or finite becomes necessary, but not sufficient, for characterizing recurrence or full transience; see the next example.

$\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m}$ is infinite or finite becomes necessary, but not sufficient, for characterizing recurrence or full transience; see the next example.

Before proceeding, we need to introduce a few terms. A state ![]() $j$ is said to be reachable from state

$j$ is said to be reachable from state ![]() $i$, denoted as

$i$, denoted as ![]() $i \rightarrow j$, if there exists

$i \rightarrow j$, if there exists ![]() $k \ge 0$, which may depend on

$k \ge 0$, which may depend on ![]() $j, i, i_3, \ldots, i_m$, such that

$j, i, i_3, \ldots, i_m$, such that  $p^{(k)}_{jii_3\ldots i_m} \gt 0$ or, equivalently,

$p^{(k)}_{jii_3\ldots i_m} \gt 0$ or, equivalently, ![]() $f_{jii_3\ldots i_m} \gt 0$, for all

$f_{jii_3\ldots i_m} \gt 0$, for all ![]() $i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$. In addition, states

$i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$. In addition, states ![]() $i$ and

$i$ and ![]() $j$ are said to communicate, denoted by

$j$ are said to communicate, denoted by ![]() $i \leftrightarrow j$, if

$i \leftrightarrow j$, if ![]() $i \rightarrow j$ and

$i \rightarrow j$ and ![]() $j \rightarrow i$. The

$j \rightarrow i$. The ![]() $\leftrightarrow$ relationship is an equivalence relationship and thus it partitions the state space

$\leftrightarrow$ relationship is an equivalence relationship and thus it partitions the state space ![]() $S$ into equivalence classes [Reference Han and Xu11].

$S$ into equivalence classes [Reference Han and Xu11].

As illustrated in [Reference Han and Xu11], there are quite a few other differences when we go from first-order to higher-order chains regarding the classification of states. For example,

• A first-order chain must have a recurrent state, but not so for a higher-order chain. Take a second-order chain on three states with transition tensor

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 0\\

0 & 1/2 & 1/2\\

0 & 1/2 & 1/2

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 1/2\\

0 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 1/2

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & 1/2 & 1\\

0 & 1/2 & 0\\

1 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 0\\

0 & 1/2 & 1/2\\

0 & 1/2 & 1/2

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 1/2\\

0 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 1/2

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & 1/2 & 1\\

0 & 1/2 & 0\\

1 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}Then,

\begin{equation*}{\cal F}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 1/2 & 3/4\\

0 & 1 & 1\\

0 & 1/2 & 1/2

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal F}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 1\\

0 & 1 & 1\\

0 & 0 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal F}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

3/4 & 1/2 & 1\\

1 & 1/2 & 1\\

1 & 0 & 1

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal F}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 1/2 & 3/4\\

0 & 1 & 1\\

0 & 1/2 & 1/2

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal F}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 1\\

0 & 1 & 1\\

0 & 0 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal F}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

3/4 & 1/2 & 1\\

1 & 1/2 & 1\\

1 & 0 & 1

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}For each

$1 \le i \le 3$, its ever-reaching probability

$1 \le i \le 3$, its ever-reaching probability  $f_{iii_3}$ equals

$f_{iii_3}$ equals  $1$ for some

$1$ for some  $i_3$ and is less than

$i_3$ and is less than  $1$ for some other

$1$ for some other  $i_3$. Consequently, none of the states in this example are recurrent. In addition, we see

for all

$i_3$. Consequently, none of the states in this example are recurrent. In addition, we see

for all \begin{equation*}\sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{11i_3}=\infty \ \ {\rm and} \ \ \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{33i_3} \lt \infty\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{11i_3}=\infty \ \ {\rm and} \ \ \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{33i_3} \lt \infty\end{equation*} $1 \le i_3 \le 3$, implying that whether

$1 \le i_3 \le 3$, implying that whether  $\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m}$ is infinite or not for all

$\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{(k)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m}$ is infinite or not for all  $i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$ is only a necessary condition for recurrence or full transience, respectively.

$i_3, \ldots, i_m \in S$ is only a necessary condition for recurrence or full transience, respectively.• In a first-order chain, a state

$i$ is recurrent provided

$i$ is recurrent provided  $j \rightarrow i$ whenever

$j \rightarrow i$ whenever  $i \rightarrow j$. Such a characterization does not apply to a higher-order chain. Consider a second-order chain with two states and transition tensor

$i \rightarrow j$. Such a characterization does not apply to a higher-order chain. Consider a second-order chain with two states and transition tensor

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

1 & 1/2\\

0 & 1/2

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

0 & 1/2\\

1 & 1/2

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

1 & 1/2\\

0 & 1/2

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

0 & 1/2\\

1 & 1/2

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}It follows

\begin{equation*}{\cal F}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

1 & 1\\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal F}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

1 & 1\\

1 & 1

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal F}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

1 & 1\\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal F}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

1 & 1\\

1 & 1

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}Both states are recurrent since

$f_{iii_3}=1$ for all

$f_{iii_3}=1$ for all  $i, i_3=1, 2$. Meanwhile,

$i, i_3=1, 2$. Meanwhile,  $2 \rightarrow 1$ yet

$2 \rightarrow 1$ yet  $1 \not\rightarrow 2$ since

$1 \not\rightarrow 2$ since  $p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2i_3} \gt 0$ for all

$p^{(k)}_{i_1i_2i_3} \gt 0$ for all  $1 \le i_1, i_2 \le 2$ and

$1 \le i_1, i_2 \le 2$ and  $k \ge 2$ but

$k \ge 2$ but  $p^{(k)}_{211}=0$ for all

$p^{(k)}_{211}=0$ for all  $k \ge 1$.

$k \ge 1$.• In a first-order chain, both recurrence and transience are class properties, that is, the states in an equivalence class must be either all recurrent or all transient. When it comes to a higher-order chain, recurrence and transience are not class properties anymore. To see this, we examine a second-order chain with three states and transition tensor

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1/2 & 1/3 & 1/2\\

1/2 & 1/2 & 0\\

0 & 1/3 & 1/2

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 1/2\\

0 & 1 & 1/2\\

0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & 0 & 1/2\\

0 & 0 & 1/2\\

1 & 1 & 0

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1/2 & 1/3 & 1/2\\

1/2 & 1/2 & 0\\

0 & 1/3 & 1/2

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 1/2\\

0 & 1 & 1/2\\

0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & 0 & 1/2\\

0 & 0 & 1/2\\

1 & 1 & 0

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}For this chain, we have

\begin{equation*}{\cal F}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

5/6 & 2/3 & 1\\

1 & 1 & 1\\

1/2 & 1/2 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal F}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 1\\

1 & 1 & 1\\

1/2 & 0 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal F}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 1 & 1\\

1 & 1 & 1\\

1 & 1 & 1

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal F}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

5/6 & 2/3 & 1\\

1 & 1 & 1\\

1/2 & 1/2 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal F}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 1\\

1 & 1 & 1\\

1/2 & 0 & 1

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal F}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 1 & 1\\

1 & 1 & 1\\

1 & 1 & 1

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}By checking its ever-reaching probabilities

$f_{iii_3}$, state

$f_{iii_3}$, state  $1$ is transient but not fully transient, and state

$1$ is transient but not fully transient, and state  $3$ is recurrent. These states, however, are in the same equivalence class, that is,

$3$ is recurrent. These states, however, are in the same equivalence class, that is,  $1 \leftrightarrow 3$.

$1 \leftrightarrow 3$.

Such differences constitute yet another roadblock to studying a higher-order chain via its reduced first-order chain. Thus, as far as classification of states is concerned, the answer to Question 2.1 is again negative.

The following was conjectured in [Reference Han and Xu11]. To end this section, we shall prove it here.

Theorem 5.1. Let ![]() $K \subset S$ be an equivalence class. Then, it is impossible to have

$K \subset S$ be an equivalence class. Then, it is impossible to have ![]() $i, j \in K$ such that

$i, j \in K$ such that ![]() $i$ is recurrent while

$i$ is recurrent while ![]() $j$ is fully transient.

$j$ is fully transient.

Proof. Let ![]() $i, j \in K$,

$i, j \in K$, ![]() $i \ne j$, with

$i \ne j$, with ![]() $j$ being recurrent. Then, it suffices to show that

$j$ being recurrent. Then, it suffices to show that ![]() $i$ cannot be fully transient.

$i$ cannot be fully transient.

Let us fix ![]() $i_3, \ldots, i_m$. Since

$i_3, \ldots, i_m$. Since ![]() $i \rightarrow j$ and

$i \rightarrow j$ and ![]() $i \ne j$, there exists

$i \ne j$, there exists ![]() $\alpha \ge 1$ such that

$\alpha \ge 1$ such that  $p^{(\alpha)}_{jii_3\ldots i_m} \gt 0$. Denote the event “the chain takes

$p^{(\alpha)}_{jii_3\ldots i_m} \gt 0$. Denote the event “the chain takes ![]() $\alpha$ steps to go from

$\alpha$ steps to go from ![]() $ii_3\ldots i_m$ to

$ii_3\ldots i_m$ to ![]() $j$” by

$j$” by ![]() $A$.

$A$.

Next, denote the event “starting from ![]() $jj_3\ldots j_m$, the chain takes

$jj_3\ldots j_m$, the chain takes ![]() $\beta$ steps to return to

$\beta$ steps to return to ![]() $j$” by

$j$” by ![]() $B$, where

$B$, where ![]() $j_3, \ldots, j_m$ are given by:

$j_3, \ldots, j_m$ are given by:

• when

$\alpha=1$:

$\alpha=1$:  $j_3=i, j_4=i_3, \ldots, j_m=i_{m-1}$

$j_3=i, j_4=i_3, \ldots, j_m=i_{m-1}$• when

$\alpha=2$:

$\alpha=2$:  $j_4=i, j_5=i_3, \ldots, j_m=i_{m-2}$, any

$j_4=i, j_5=i_3, \ldots, j_m=i_{m-2}$, any  $j_3$

$j_3$•

$\cdots$

$\cdots$• when

$\alpha=m-2$:

$\alpha=m-2$:  $j_m=i$, any

$j_m=i$, any  $j_3,\ldots,j_{m-1}$

$j_3,\ldots,j_{m-1}$•

$\cdots$

$\cdots$

Fix ![]() $j_3, \ldots, j_m$ from now on.

$j_3, \ldots, j_m$ from now on.

Next, denote the event “the chain takes ![]() $\gamma$ steps to go from

$\gamma$ steps to go from ![]() $jk_3\ldots k_m$ to

$jk_3\ldots k_m$ to ![]() $i$” by

$i$” by ![]() $C$, where

$C$, where ![]() $k_3, \ldots, k_m$ are determined in the same way as

$k_3, \ldots, k_m$ are determined in the same way as ![]() $j_3, \ldots, j_m$ above.

$j_3, \ldots, j_m$ above.

From this point on, let us assume ![]() $\beta \ge m-1$. Thus, we can fix

$\beta \ge m-1$. Thus, we can fix ![]() $k_3, \ldots, k_m$. Accordingly, by

$k_3, \ldots, k_m$. Accordingly, by ![]() $j \rightarrow i$ and

$j \rightarrow i$ and ![]() $i \ne j$, there exists

$i \ne j$, there exists ![]() $\gamma \ge 1$ such that

$\gamma \ge 1$ such that  $p^{(\gamma)}_{ijk_3\ldots k_m} \gt 0$.

$p^{(\gamma)}_{ijk_3\ldots k_m} \gt 0$.

Finally, we observe

\begin{align*}

p^{(\gamma+\beta+\alpha)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m} & \ge \Pr(ABC)\\

& = \Pr(A)\Pr(B|A)\Pr(C|AB)\\

& = p^{(\alpha)}_{jii_3\ldots i_m}p^{(\beta)}_{jjj_3\ldots j_m}p^{(\gamma)}_{ijk_3\ldots k_m}.

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

p^{(\gamma+\beta+\alpha)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m} & \ge \Pr(ABC)\\

& = \Pr(A)\Pr(B|A)\Pr(C|AB)\\

& = p^{(\alpha)}_{jii_3\ldots i_m}p^{(\beta)}_{jjj_3\ldots j_m}p^{(\gamma)}_{ijk_3\ldots k_m}.

\end{align*}It follows that

\begin{equation*}\sum_{\beta=m-1}^\infty p^{(\gamma+\beta+\alpha)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m} \ge p^{(\alpha)}_{jii_3\ldots i_m}p^{(\gamma)}_{ijk_3\ldots k_m}\sum_{\beta=m-1}^\infty p^{(\beta)}_{jjj_3\ldots j_m}=\infty\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\sum_{\beta=m-1}^\infty p^{(\gamma+\beta+\alpha)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m} \ge p^{(\alpha)}_{jii_3\ldots i_m}p^{(\gamma)}_{ijk_3\ldots k_m}\sum_{\beta=m-1}^\infty p^{(\beta)}_{jjj_3\ldots j_m}=\infty\end{equation*}since ![]() $j$ is recurrent. The above clearly leads to

$j$ is recurrent. The above clearly leads to

\begin{equation*}\sum_{\beta=1}^\infty p^{(\beta)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m}=\infty.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\sum_{\beta=1}^\infty p^{(\beta)}_{iii_3\ldots i_m}=\infty.\end{equation*}The proof is now complete.

6. Mean first passage times

For convenience, let us use a framework that includes both higher-order and first-order chains.

Recall ![]() $\eta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}$ in (3.1). For an

$\eta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}$ in (3.1). For an ![]() $(m-1)$th order,

$(m-1)$th order, ![]() $m \ge 2$, chain with state space

$m \ge 2$, chain with state space ![]() $S=\{1, 2, \ldots, n\}$, the mean first passage time from states

$S=\{1, 2, \ldots, n\}$, the mean first passage time from states ![]() $(i_2, \ldots, i_m)$ to

$(i_2, \ldots, i_m)$ to ![]() $i_1$ is defined by

$i_1$ is defined by

\begin{equation*}\mu_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}={\rm E}(\eta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m})=\sum_{k=1}^\infty k\Pr(\eta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=k).\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\mu_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}={\rm E}(\eta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m})=\sum_{k=1}^\infty k\Pr(\eta_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}=k).\end{equation*} Accordingly, the mean first passage time tensor is the ![]() $m$th order,

$m$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional tensor

$n$ dimensional tensor ![]() $\mu=[\mu_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$.

$\mu=[\mu_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$.

As shown in [Reference Han and Xu10], for an ergodic higher-order chain of order ![]() $m-1$ whose

$m-1$ whose ![]() $m$th order,

$m$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional transition tensor is

$n$ dimensional transition tensor is ![]() $\cal P$, its mean first passage times are finite and are uniquely determined by the following tensor equation:

$\cal P$, its mean first passage times are finite and are uniquely determined by the following tensor equation:

where ![]() $\cal E$ is the

$\cal E$ is the ![]() $m$th order,

$m$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional tensor of all ones. Furthermore, as a linear system, (6.1) is nonsingular if and only if the chain is ergodic.

$n$ dimensional tensor of all ones. Furthermore, as a linear system, (6.1) is nonsingular if and only if the chain is ergodic.

Comparing with an ergodic first-order chain, the mean first passage time matrix ![]() $M$ satisfies [Reference Kemeny and Snell19]

$M$ satisfies [Reference Kemeny and Snell19]

where ![]() $E$ is the matrix of all ones and

$E$ is the matrix of all ones and  $M_d=[m^{(d)}_{ij}]$ is such that

$M_d=[m^{(d)}_{ij}]$ is such that

\begin{equation*}m^{(d)}_{ij}=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

m_{ii}, & i=j;\\

0, & {\rm otherwise}.

\end{array}\right.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}m^{(d)}_{ij}=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

m_{ii}, & i=j;\\

0, & {\rm otherwise}.

\end{array}\right.\end{equation*}Clearly, (6.2) is a special case of (6.1). Because of the resemblance between (6.1) and (6.2), and in the spirit of Question 2.1, it is an intriguing question whether (6.1) can be derived from (6.2) using the reduced first-order chain. The answer, however, turns out to be negative, as illustrated by the example below.

Take a second-order chain with three states and

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)={\cal P}(:,:,2)={\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1/3 & 1/3 & 1/3\\

1/3 & 1/3 & 1/3\\

1/3 & 1/3 & 1/3

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)={\cal P}(:,:,2)={\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

1/3 & 1/3 & 1/3\\

1/3 & 1/3 & 1/3\\

1/3 & 1/3 & 1/3

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}By solving (6.1),

\begin{equation*}\mu(:,:,1)=\mu(:,:,2)=\mu(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

3 & 3 & 3\\

3 & 3 & 3\\

3 & 3 & 3

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\mu(:,:,1)=\mu(:,:,2)=\mu(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

3 & 3 & 3\\

3 & 3 & 3\\

3 & 3 & 3

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*} On the other hand, observing that the regularity of this second-order chain carries over to its reduced first-order chain since ![]() $Q^2=(1/9)E \gt 0$, where

$Q^2=(1/9)E \gt 0$, where ![]() $E$ is the matrix of all ones, and using (6.2) for the reduced first-order chain, we obtain

$E$ is the matrix of all ones, and using (6.2) for the reduced first-order chain, we obtain

\begin{equation*}M=\left[\begin{array}{ccccccccc}

9 & 12 & 12 & 9 & 12 & 12 & 9 & 12 & 12\\

6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9\\

6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9\\

9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9\\

12 & 9 & 12 & 12 & 9 & 12 & 12 & 9 & 12\\

9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9\\

9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6\\

9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6\\

12 & 12 & 9 & 12 & 12 & 9 & 12 & 12 & 9

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}M=\left[\begin{array}{ccccccccc}

9 & 12 & 12 & 9 & 12 & 12 & 9 & 12 & 12\\

6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9\\

6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9\\

9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9\\

12 & 9 & 12 & 12 & 9 & 12 & 12 & 9 & 12\\

9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9\\

9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6\\

9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6 & 9 & 9 & 6\\

12 & 12 & 9 & 12 & 12 & 9 & 12 & 12 & 9

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*} Obviously, in this example, ![]() $\mu$ does not follow directly from

$\mu$ does not follow directly from ![]() $M$. If we look at

$M$. If we look at ![]() $m_{11}$, for instance, it represents the mean first passage time from state

$m_{11}$, for instance, it represents the mean first passage time from state ![]() $11$, in multi-index form, to itself. This quantity, however, is different from

$11$, in multi-index form, to itself. This quantity, however, is different from ![]() $\mu_{111}$. In other words, while addressing Question 2.1, other difficulties may still arise even if ergodicity or regularity does carry forward from a higher-order chain to its reduced first-order chain.

$\mu_{111}$. In other words, while addressing Question 2.1, other difficulties may still arise even if ergodicity or regularity does carry forward from a higher-order chain to its reduced first-order chain.

One way of working around the discrepancy as shown above between the mean first passage times of a higher-order chain and those of its reduced first-order chain is to resort to certain matricization of the transition tensor [Reference Han and Xu10]. This approach is not as convenient as the direct tensor treatment leading to (6.1). Besides, its result can be easily obtained by matricizing the mean first passage time tensor from (6.1).

7. Limiting probability distributions

Having presented a range of differences between higher-order and first-order chains in previous sections, we now come to a point where these two appear to converge to a certain level. Again, we use here a framework that includes both higher-order and first-order chains.

With ![]() $m \ge 2$, let

$m \ge 2$, let ![]() $X=\{X_t : t=1, 2, \ldots\}$ be an

$X=\{X_t : t=1, 2, \ldots\}$ be an ![]() $(m-1)$th order chain on state space

$(m-1)$th order chain on state space ![]() $S=\{1, 2, \ldots, n\}$ whose transition tensor is

$S=\{1, 2, \ldots, n\}$ whose transition tensor is ![]() ${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$. The probability distribution of

${\cal P}=[p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_m}]$. The probability distribution of ![]() $X$ at

$X$ at ![]() $t$ is given by

$t$ is given by

If there exists an ![]() $n$-vector

$n$-vector ![]() $\pi$, which is independent of the initial probability distributions

$\pi$, which is independent of the initial probability distributions ![]() $x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_{m-1}$, such that

$x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_{m-1}$, such that

\begin{equation*}\lim_{t \rightarrow \infty}x_t=\pi,\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\lim_{t \rightarrow \infty}x_t=\pi,\end{equation*}then ![]() $\pi$ is called the limiting probability distribution of the chain

$\pi$ is called the limiting probability distribution of the chain ![]() $X$[Reference Han and Xu12]. It is clear that

$X$[Reference Han and Xu12]. It is clear that ![]() $\pi$ satisfies

$\pi$ satisfies ![]() $\pi \ge 0$ and

$\pi \ge 0$ and  $\displaystyle \sum_{i \in S}\pi_i=1$.

$\displaystyle \sum_{i \in S}\pi_i=1$.

On the other hand, let ![]() $Y$ be the reduced first-order chain associated with

$Y$ be the reduced first-order chain associated with ![]() $X$, whose transition matrix is given by

$X$, whose transition matrix is given by ![]() $Q$. Then, an

$Q$. Then, an ![]() $N$-vector

$N$-vector ![]() $\xi$ is said to be a stationary distribution of both the chains

$\xi$ is said to be a stationary distribution of both the chains ![]() $X$ and

$X$ and ![]() $Y$ if

$Y$ if ![]() $\xi$ satisfies

$\xi$ satisfies ![]() $\xi \ge 0$,

$\xi \ge 0$,  $\displaystyle \sum_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1} \in T}\xi_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}}=1$, and

$\displaystyle \sum_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1} \in T}\xi_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}}=1$, and ![]() $Q\xi=\xi$. The subscript for the entries of

$Q\xi=\xi$. The subscript for the entries of ![]() $\xi$ is written here in multi-index form. Consequently,

$\xi$ is written here in multi-index form. Consequently, ![]() $Q\xi=\xi$ translates to

$Q\xi=\xi$ translates to

\begin{equation*}\sum_{j \in S}p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}j}\xi_{i_2\ldots i_{m-1}j}=\xi_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}}, ~i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_{m-1} \in S,\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\sum_{j \in S}p_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}j}\xi_{i_2\ldots i_{m-1}j}=\xi_{i_1i_2\ldots i_{m-1}}, ~i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_{m-1} \in S,\end{equation*}which is precisely how a stationary distribution is equivalently defined in [Reference Gleich, Lim and Yu8] when ![]() $\xi$ is treated as an

$\xi$ is treated as an ![]() $(m-1)$th order,

$(m-1)$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional tensor. Obviously, as a vector,

$n$ dimensional tensor. Obviously, as a vector, ![]() $\xi$ is just a normalized right eigenvector of

$\xi$ is just a normalized right eigenvector of ![]() $Q$ corresponding to the dominant eigenvalue

$Q$ corresponding to the dominant eigenvalue ![]() $\lambda=1$, sometimes also called a Perron vector [Reference Horn and Johnson14].

$\lambda=1$, sometimes also called a Perron vector [Reference Horn and Johnson14].

It is shown in [Reference Han and Xu12] that if the chain ![]() $X$ is regular, then its limiting probability distribution

$X$ is regular, then its limiting probability distribution ![]() $\pi$ is guaranteed to exist. In this case,

$\pi$ is guaranteed to exist. In this case, ![]() $\pi \gt 0$ and

$\pi \gt 0$ and

\begin{equation*}\lim_{k \rightarrow \infty}{\cal P}^k=\pi \otimes \underbrace{e \otimes \cdots \otimes e}_{m-1},\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\lim_{k \rightarrow \infty}{\cal P}^k=\pi \otimes \underbrace{e \otimes \cdots \otimes e}_{m-1},\end{equation*}where, and in what follows, ![]() $e$ is the

$e$ is the ![]() $n$-vector of all ones and

$n$-vector of all ones and ![]() $\otimes$ is the outer product. Without the regularity condition on

$\otimes$ is the outer product. Without the regularity condition on ![]() $X$,

$X$, ![]() $\pi$ may not exist and therefore such a condition is tight.

$\pi$ may not exist and therefore such a condition is tight.

Regarding a stationary distribution of the chains ![]() $X$ and

$X$ and ![]() $Y$, its existence is guaranteed following the celebrated Perron–Frobenius theorem, yet such a distribution may not be unique. If, in addition,

$Y$, its existence is guaranteed following the celebrated Perron–Frobenius theorem, yet such a distribution may not be unique. If, in addition, ![]() $Y$ is a regular chain, then its stationary distribution

$Y$ is a regular chain, then its stationary distribution ![]() $\xi$ is unique and

$\xi$ is unique and ![]() $\xi \gt 0$.

$\xi \gt 0$.

The preceding results regarding the limiting probability distribution and stationary distribution continue to hold when the chain ![]() $X$ is first order and regular [Reference Hunter16, Reference Kemeny and Snell19]. In this scenario, the limiting probability distribution is the same as the stationary distribution. To be more specific, on letting

$X$ is first order and regular [Reference Hunter16, Reference Kemeny and Snell19]. In this scenario, the limiting probability distribution is the same as the stationary distribution. To be more specific, on letting ![]() $P$ be the transition matrix, then there exists a unique

$P$ be the transition matrix, then there exists a unique ![]() $n$-vector

$n$-vector ![]() $\pi \gt 0$ with

$\pi \gt 0$ with  $\displaystyle \sum_{i \in S}\pi_i=1$ such that

$\displaystyle \sum_{i \in S}\pi_i=1$ such that  $\displaystyle \lim_{k \rightarrow \infty}P^k=\pi e^T$ and, at the same time,

$\displaystyle \lim_{k \rightarrow \infty}P^k=\pi e^T$ and, at the same time, ![]() $P\pi=\pi$ [Reference Kemeny and Snell19]. This appears to be the cause of why the nomenclatures “limiting probability distribution” and “stationary distribution” are at times used interchangeably in works on higher-order chains. Our foregoing description of these concepts clarifies the difference between them in the higher-order case.

$P\pi=\pi$ [Reference Kemeny and Snell19]. This appears to be the cause of why the nomenclatures “limiting probability distribution” and “stationary distribution” are at times used interchangeably in works on higher-order chains. Our foregoing description of these concepts clarifies the difference between them in the higher-order case.

Despite the differences, there is a principal connection between them too. As shown in [Reference Han and Xu12], when the chain ![]() $X$ is higher order and regular, its limiting probability distribution

$X$ is higher order and regular, its limiting probability distribution ![]() $\pi$ can be determined via any stationary distribution

$\pi$ can be determined via any stationary distribution ![]() $\xi$ through

$\xi$ through

where ![]() $P^{(0)}$ stands for the mode-

$P^{(0)}$ stands for the mode-![]() $1$ matricization of the

$1$ matricization of the ![]() $m$th order,

$m$th order, ![]() $n$ dimensional identity tensor. This result does not require the chain

$n$ dimensional identity tensor. This result does not require the chain ![]() $Y$ to be regular.

$Y$ to be regular.

To illustrate the usage of (7.1), let us take the same regular second-order chain as in Section 4 with four states and transition tensor

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

1/2 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 0 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 1 & 0 & 1\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 0 & 1/2 & 1\\

0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 1/2 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 0 & 1/2 & 0

\end{array}\right],\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,1)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

1/2 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 0 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 1 & 0 & 1\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,2)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 0 & 1/2 & 1\\

0 & 1/2 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 1/2 & 0 & 0\\

1/2 & 0 & 1/2 & 0

\end{array}\right],\end{equation*} \begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 1 & 0 & 1\\

1 & 0 & 1/2 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,4)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 1 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1/2\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1/2

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\cal P}(:,:,3)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 1 & 0 & 1\\

1 & 0 & 1/2 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 1/2 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right], ~{\cal P}(:,:,4)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 1 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1/2\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1/2

\end{array}\right].\end{equation*} The associated reduced first-order chain is reducible, which can also be seen from the fact that the dominant eigenvalue ![]() $\lambda=1$ of its transition matrix

$\lambda=1$ of its transition matrix ![]() $Q$ has multiplicity

$Q$ has multiplicity ![]() $2$. This, of course, implies that the reduced first-order chain is not regular. It is easy to verify that

$2$. This, of course, implies that the reduced first-order chain is not regular. It is easy to verify that

\begin{equation*}\displaystyle z=\frac{1}{7}[0 ~~0 ~~1 ~~1 ~~2 ~~0 ~~0 ~~0 ~~0 ~~2 ~~0 ~~0 ~~0 ~~0 ~~1 ~~0]^T\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\displaystyle z=\frac{1}{7}[0 ~~0 ~~1 ~~1 ~~2 ~~0 ~~0 ~~0 ~~0 ~~2 ~~0 ~~0 ~~0 ~~0 ~~1 ~~0]^T\end{equation*}is a normalized right eigenvector corresponding to that dominant eigenvalue above. Hence, the limiting probability distribution of the second-order chain is

\begin{equation*}\pi=P^{(0)}z=\frac{1}{7}[2 ~~2 ~~2 ~~1]^T.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\pi=P^{(0)}z=\frac{1}{7}[2 ~~2 ~~2 ~~1]^T.\end{equation*} Regarding Question 2.1, when it comes to the limiting probability distribution problem of a higher-order chain, (7.1) represents its close tie with a stationary distribution of the corresponding reduced first-order chain. This, along with the ![]() $k$-step transition probabilities in Section 3, is another case in which Question 2.1 yields a positive answer.

$k$-step transition probabilities in Section 3, is another case in which Question 2.1 yields a positive answer.

8. Conclusions

In this article, we provide a relatively comprehensive answer to Question 2.1 in order to address a still prevailing perception, or “rooted prejudice” in the words of Marius Iosifescu, concerning higher-order chains. Our results show that there can be significant differences between a higher-order chain and its reduced first-order chain in most aspects such as ergodicity, regularity, ever-reaching probabilities, mean first passage times, and classification of states. Owing to such differences, the answer to Question 2.1 is negative in general. In the meantime, the closest, and also probably the most useful, tie between a higher-order chain and its reduced first-order chain is seen in the limiting probability distribution problem. Overall, it remains a very interesting topic to further explore whether a reduced first-order chain may, or may not, play a useful role in studying other key quantities for its originating higher-order chain. Moreover, the largely tensor theoretic framework employed throughout this article proves to be highly effective for analyzing higher-order chains.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewer for the careful reading and helpful comments, which have led to an improved presentation.