1. Introduction

Hypersonic vehicles experience extreme heat loads during flight, which requires a suitable thermal management system to maintain material temperatures below critical thresholds (Anderson Reference Anderson2006). Heating results from a combination of heat conduction, radiation and gas–surface interactions. The complex nature of high-enthalpy flows interacting with the vehicle surface introduces uncertainties into predictive models. These interactions involve various processes, such as catalytic recombination, oxidation and nitridation, e.g. detailed in Prata, Minton & Schwartzentruber (Reference Prata, Minton and Schwartzentruber2021). In heterogeneous catalytic surface recombination, atomic species recombine on active surface sites, releasing heat into the material. These atomic species are adsorbed onto the surface and can react with other atoms – either adsorbed or in the gas phase – or with the surface material itself to form molecules that are then released into the flow (Josyula Reference Josyula2015). The material-dependent recombination effectiveness of atoms is typically described by the recombination coefficient,

![]() $\gamma$

. A comprehensive review of related experiments can be found in Chazot et al. (Reference Chazot, Panerai, Muylaert and Thoemel2010).

$\gamma$

. A comprehensive review of related experiments can be found in Chazot et al. (Reference Chazot, Panerai, Muylaert and Thoemel2010).

The catalytic recombination coefficient plays a significant role in surface heating and is often determined through experimentation. Massuti-Ballester & Herdrich (Reference Massuti-Ballester and Herdrich2021) present an extensive overview of experiments focused on oxygen and nitrogen recombination. Since the recombination coefficient is strongly influenced by surface temperature (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Yang, Park and Jo2021a ), experiments are conducted in high-enthalpy facilities that replicate the thermochemical conditions encountered during flight, including the high surface temperatures of the tested materials. To ensure accurate surface chemistry measurements, highly pure plasma flows are preferred, which can be achieved in inductively coupled plasma wind tunnels (Pidan et al. Reference Pidan, Auweter-Kurtz, Herdrich and Fertig2005; Meyers, Owens & Fletcher Reference Meyers, Owens and Fletcher2013; Viladegut Reference Viladegut2015). These facilities exhibit fluctuating behaviour, driven primarily by the characteristic frequency of their electrical power supply. Zander, Marynowski & Löhle (Reference Zander, Marynowski and Löhle2017) measured a dominant frequency of 300 Hz in the University of Stuttgart’s PWK3 facility, while Capponi et al. (Reference Capponi, Oldham, Konnik, Stephani, Bodony, Panesi, Elliott and Panerai2023) recorded a dominant frequency of 360 Hz in the University of Illinois’ Plasmatron X facility.

In addition to catalytic surface recombination, other surface reactions that occur during material ablation, such as surface oxidation and nitridation, are also influenced by the incoming flux of atomic particles and the properties of the surface. Ablation experiments are commonly conducted in plasma wind tunnels (Hermann et al. Reference Hermann, Löhle, Fasoulas, Leyland, Marraffa and Bouilly2017a ; Löhle et al. Reference Löhle, Hermann and Zander2018), where flow conditions can be highly unsteady, resulting in fluctuating free-stream conditions (Zander et al. Reference Zander, Marynowski and Löhle2017; Ravichandran et al. Reference Ravichandran, Leiser, Zander, Löhle, Matlovič, Tóth and Ferrière2021; Oldham et al. Reference Oldham, Capponi, Konnik, Stephani, Bodony, Panesi, Elliott and Panerai2023; Hermann & Chang Reference Hermann and Chang2024). These fluctuations can occur at frequencies of the order of several kHz, and the amplitudes can be significant (Hermann et al. Reference Hermann, Löhle, Fasoulas and Andrianatos2016; Zander, Hermann & Loehle Reference Zander, Hermann and Loehle2016). For example, Zander et al. (Reference Zander, Marynowski and Löhle2017) found that flow temperature in an inductively coupled plasma facility can fluctuate by as much as 4000 K, with a mean temperature of approximately 13 400 K. Similarly, Hermann & Chang (Reference Hermann and Chang2024) report temperature fluctuations of approximately 1300 K, with a mean temperature of 10 100 K in an arc-jet free stream.

While testing methodologies and flow characteristics may vary between different facilities, most suffer from some form of unsteadiness. Material samples tested under such conditions will be subjected to changing flow conditions – specifically, the boundary-layer-edge condition will be unsteady, leading to fluctuating surface conditions. As a result, the atomic mass flux to the surface will vary over time. If these experiments are analysed assuming steady-state conditions, errors may arise in the determination of material surface properties, as the dissociated flow physics and surface reaction efficiencies are non-linear. Furthermore, a varying heat flux will cause a fluctuation in surface temperature. Most gas–surface reactions are non-linearly related to the surface temperature (Prata et al. Reference Prata, Minton and Schwartzentruber2021). Through this non-linear behaviour, the average surface reactivity depends not only on the time-averaged atomic surface concentration, but also on its fluctuation magnitude. Therefore, it is desirable to develop a theory capable of predicting the strength of atomic-mass-fraction fluctuations at the surface for a non-equilibrium high-enthalpy flow. This allows for more accurate analysis of experiments, including the transient effects present in test facilities. Unsteady flows may simultaneously exhibit unsteadiness in other flow variables, such as density, velocity or temperature. This could lead to coupled effects, which are beyond the scope of the current work.

The aim of this paper is to develop a basic analytical theory for unsteady atomic and molecular species transport in reacting non-equilibrium boundary layers and to explore its properties. This allows the identification of relevant scaling parameters and the assessment of their respective significance for any given flow condition. The derivation of this approach is accomplished by constructing semi-empirical correlations based on analytical solutions to the reacting boundary-layer equations. It will be demonstrated that the unsteady reacting flow behaviour can be effectively described by a correlation that only requires knowledge of the steady frozen-flow solution and the fluctuation frequency. The current work builds upon the approximate theory developed by Inger (Reference Inger1963), extending it to account for unsteady flow dynamics. The resulting correlation is validated against fully coupled numerical solutions of the self-similar thermal and concentration boundary-layer equations. Under certain simplifying assumptions, the correlation can be expressed entirely in terms of non-dimensional heat and mass-transfer numbers. Finally, the paper highlights the impact of unsteady flow on the conditions faced in experimental ground testing facilities.

2. Analytical derivation

In this section, the governing equations and the strategy to solve them in a semi-empirical fashion are presented. The fully coupled boundary-layer theory of energy and species transport is broken down into two special cases, where either diffusion processes or chemical reactions dominate over other terms. This strategy allows for analytically closed solutions, supplemented by empirical correlations, which form the basis of a generalised engineering correlation describing unsteady non-equilibrium species transport.

Figure 1. Domain sketch of flow configuration (not to scale).

2.1. Governing equations

The assumption of a self-similar stagnation point around axisymmetric (

![]() $\epsilon = 1$

) or two-dimensional (

$\epsilon = 1$

) or two-dimensional (

![]() $\epsilon = 0$

) (

$\epsilon = 0$

) (

![]() $\epsilon$

is a shape parameter) bodies of revolution is employed, with the domain sketch presented in figure 1. In the following analysis, the subscript

$\epsilon$

is a shape parameter) bodies of revolution is employed, with the domain sketch presented in figure 1. In the following analysis, the subscript

![]() $\infty$

is used to denote properties of the free stream,

$\infty$

is used to denote properties of the free stream,

![]() $w$

is used to denote wall conditions, and

$w$

is used to denote wall conditions, and

![]() $e$

is used to denote boundary-layer-edge properties. The current work is limited to cases where self-similar theory is appropriate (see Harris & Ii Reference Harris and Ii1982; Tauber Reference Tauber1989; Prévereaud et al. Reference Prévereaud, Vérant and Annaloro2019). This includes the implicit assumption that the boundary-layer edge is in thermochemical equilibrium at all times (Goulard Reference Goulard1958). A body of spherical or cylindrical geometry is assessed as it represents a typical test configuration of material samples and diagnostic probes (Löhle et al. Reference Löhle, Hermann and Zander2018; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, James, Ravichandran, Morgan and McIntyre2018). It also acts as a canonical geometry case, which can be used to transform the boundary-layer properties to other commonly used geometries in material testing, such as a flat-faced cylinder (Hermann et al. Reference Hermann, Löhle, Zander and Fasoulas2017b

). The unsteady boundary-layer equations of energy and atomic mass transport are considered. The derivation of Fay & Riddell (Reference Fay and Riddell1958) is adapted, utilising the formulation found in Inger (Reference Inger1963). These equations have been extended to include the appropriate unsteady terms, based on the derivation found in Dorrance (Reference Dorrance2017), yielding

$e$

is used to denote boundary-layer-edge properties. The current work is limited to cases where self-similar theory is appropriate (see Harris & Ii Reference Harris and Ii1982; Tauber Reference Tauber1989; Prévereaud et al. Reference Prévereaud, Vérant and Annaloro2019). This includes the implicit assumption that the boundary-layer edge is in thermochemical equilibrium at all times (Goulard Reference Goulard1958). A body of spherical or cylindrical geometry is assessed as it represents a typical test configuration of material samples and diagnostic probes (Löhle et al. Reference Löhle, Hermann and Zander2018; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, James, Ravichandran, Morgan and McIntyre2018). It also acts as a canonical geometry case, which can be used to transform the boundary-layer properties to other commonly used geometries in material testing, such as a flat-faced cylinder (Hermann et al. Reference Hermann, Löhle, Zander and Fasoulas2017b

). The unsteady boundary-layer equations of energy and atomic mass transport are considered. The derivation of Fay & Riddell (Reference Fay and Riddell1958) is adapted, utilising the formulation found in Inger (Reference Inger1963). These equations have been extended to include the appropriate unsteady terms, based on the derivation found in Dorrance (Reference Dorrance2017), yielding

and

with

![]() $z = \alpha / \alpha _e$

representing the non-dimensional atomic mass fraction, where

$z = \alpha / \alpha _e$

representing the non-dimensional atomic mass fraction, where

![]() $\alpha$

is the atomic mass fraction. Here

$\alpha$

is the atomic mass fraction. Here

![]() $\theta = T/T_e$

is the non-dimensional temperature,

$\theta = T/T_e$

is the non-dimensional temperature,

![]() ${\textit{Sc}}$

designates the Schmidt number,

${\textit{Sc}}$

designates the Schmidt number,

![]() $Pr$

the Prandtl number,

$Pr$

the Prandtl number,

![]() $f$

represents the Blasius function,

$f$

represents the Blasius function,

![]() $\beta = ({\rm d}u/{\rm d}s)$

is the stagnation-point velocity gradient, with

$\beta = ({\rm d}u/{\rm d}s)$

is the stagnation-point velocity gradient, with

![]() $s$

denoting the orientation tangential to the surface. The non-dimensional dissociation enthalpy is

$s$

denoting the orientation tangential to the surface. The non-dimensional dissociation enthalpy is

![]() $H_D = \alpha _e {Le}\, h_D / ( c_{p,M} T_e )$

,

$H_D = \alpha _e {Le}\, h_D / ( c_{p,M} T_e )$

,

![]() $Le$

is the Lewis number,

$Le$

is the Lewis number,

![]() $c_{p,M}$

is the specific heat at constant pressure of the molecules in the flow, and

$c_{p,M}$

is the specific heat at constant pressure of the molecules in the flow, and

![]() $h_D$

is the specific dissociation enthalpy of the molecules. A

$h_D$

is the specific dissociation enthalpy of the molecules. A

![]() $( \,\dot { }\, )$

symbol refers to the derivative with respect to time, and a (

$( \,\dot { }\, )$

symbol refers to the derivative with respect to time, and a (

![]() $'$

) symbol refers to a derivative with respect to the non-dimensional coordinate normal to the wall,

$'$

) symbol refers to a derivative with respect to the non-dimensional coordinate normal to the wall,

\begin{equation} \eta = \sqrt {\frac {\rho _e(1+\epsilon ) \beta }{C \mu _e}} \int _0^y \frac {\rho }{\rho _e} {\rm d}y, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \eta = \sqrt {\frac {\rho _e(1+\epsilon ) \beta }{C \mu _e}} \int _0^y \frac {\rho }{\rho _e} {\rm d}y, \end{equation}

with the Chapman–Rubesin factor

![]() $C = \rho \mu / \rho _e \mu _e = {const}$

,

$C = \rho \mu / \rho _e \mu _e = {const}$

,

![]() $\rho$

is density, and

$\rho$

is density, and

![]() $\mu$

is dynamic viscosity. The Damkoehler number is

$\mu$

is dynamic viscosity. The Damkoehler number is

where the recombination rate constant

![]() $K_r$

relates to

$K_r$

relates to

![]() $k_r^{\prime} = K_r/T^\xi$

,

$k_r^{\prime} = K_r/T^\xi$

,

![]() $p_e$

represents the Pitot pressure and

$p_e$

represents the Pitot pressure and

![]() $R_u$

is the universal gas constant. The Damkoehler number gives a representation of the ratio of flow time over recombination time. In this work, the exponent for the reaction speed

$R_u$

is the universal gas constant. The Damkoehler number gives a representation of the ratio of flow time over recombination time. In this work, the exponent for the reaction speed

![]() $\xi =-1.5$

is used, according to the works of Fay & Riddell (Reference Fay and Riddell1958) and Dorrance (Reference Dorrance2017). In the current work, a generic mixture of atoms

$\xi =-1.5$

is used, according to the works of Fay & Riddell (Reference Fay and Riddell1958) and Dorrance (Reference Dorrance2017). In the current work, a generic mixture of atoms

![]() $A$

and diatomic molecules

$A$

and diatomic molecules

![]() $A_2$

are assumed where the dissociation and recombination reactions are described by

$A_2$

are assumed where the dissociation and recombination reactions are described by

with the collision partner

![]() $M$

. This generic description is based on the work of Lighthill (Reference Lighthill1957) and was subsequently used by Fay & Riddell (Reference Fay and Riddell1958) in their analysis on stagnation-point heating. The approach lends itself to the current work, as a general theoretical framework is sought to be established applicable to different diatomic gases. The net reaction term

$M$

. This generic description is based on the work of Lighthill (Reference Lighthill1957) and was subsequently used by Fay & Riddell (Reference Fay and Riddell1958) in their analysis on stagnation-point heating. The approach lends itself to the current work, as a general theoretical framework is sought to be established applicable to different diatomic gases. The net reaction term

![]() $R$

is a function of both the local temperature and atom concentration and is calculated via the formulation found in Inger (Reference Inger1963):

$R$

is a function of both the local temperature and atom concentration and is calculated via the formulation found in Inger (Reference Inger1963):

where

![]() $\theta _D = h_D / (R_M T_e)$

is the dissociation temperature, and

$\theta _D = h_D / (R_M T_e)$

is the dissociation temperature, and

![]() $R_M$

is the specific gas constant of the molecules.

$R_M$

is the specific gas constant of the molecules.

Equations (2.1) and (2.2) are a coupled set of non-linear partial differential equations and require a numerical solution to accurately capture the flow behaviour in the boundary layer. The approach presented in this work is an approximation of these equations using analytical solutions of special cases and connecting these with an empirical correlation that captures the essential flow physics in unsteady reacting non-equilibrium boundary layers. This is achieved by investigating two simplified cases, the diffusion-dominated regime and the reaction-dominated regime. These two special cases will be derived in the following sections, followed by their application in a generalised correlation.

2.2. Diffusion-dominated regime

This special case considers a flow dominated by the effects of unsteady diffusion. Convective transport (

![]() ${\textit{Sc}}f(\eta ) z'$

) and reaction terms (

${\textit{Sc}}f(\eta ) z'$

) and reaction terms (

![]() $({\alpha _e}/{1 + \alpha _e}) {\textit{Da}}\, R(z,\theta )$

) are neglected. These simplifications allow a closed analytical solution to this case which is used in the following semi-empirical correlation. Equation (2.1) becomes

$({\alpha _e}/{1 + \alpha _e}) {\textit{Da}}\, R(z,\theta )$

) are neglected. These simplifications allow a closed analytical solution to this case which is used in the following semi-empirical correlation. Equation (2.1) becomes

This represents the boundary layer as a non-moving slab of fluid where reactions do not take place, i.e. frozen conditions (Wang, Yu & Bao (Reference Wang, Yu and Bao2018)). Neglecting convective transport has to be compensated by using an appropriate choice of boundary-layer thickness, which will be discussed in § 2.4. This formulation is used in part due to its linear time-invariant properties, allowing solutions to be superimposed. This property is exploited by employing the Fourier transform, yielding

where

![]() $\tilde {z}$

is the Fourier-transformed non-dimensional concentration and

$\tilde {z}$

is the Fourier-transformed non-dimensional concentration and

![]() $\omega$

is a frequency. A general solution to (2.8) is

$\omega$

is a frequency. A general solution to (2.8) is

\begin{equation} \tilde {z}= C_1\, \exp \left ( \left ( 1+ {\rm i} \right ) \sqrt {\frac {\omega \,{\textit{Sc}}}{2 (1+\epsilon )\beta }}\, \eta \right ) + C_2\, \exp \left ( - \left ( 1+ {\rm i} \right ) \sqrt {\frac {\omega \,{\textit{Sc}}}{2 (1+\epsilon )\beta }} \, \eta \right ), \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \tilde {z}= C_1\, \exp \left ( \left ( 1+ {\rm i} \right ) \sqrt {\frac {\omega \,{\textit{Sc}}}{2 (1+\epsilon )\beta }}\, \eta \right ) + C_2\, \exp \left ( - \left ( 1+ {\rm i} \right ) \sqrt {\frac {\omega \,{\textit{Sc}}}{2 (1+\epsilon )\beta }} \, \eta \right ), \end{equation}

where the coefficients

![]() $C_{1,2}$

are calculated based on the boundary conditions

$C_{1,2}$

are calculated based on the boundary conditions

The first term in (2.10) describes the conditions found at the edge of the concentration boundary layer thickness at

![]() $\eta = \delta _c$

. A harmonic oscillation of frequency

$\eta = \delta _c$

. A harmonic oscillation of frequency

![]() $\omega$

and amplitude

$\omega$

and amplitude

![]() $\Delta z_\infty$

is imposed originating from concentration fluctuations in the free stream. A single frequency is investigated, as arbitrary time-dependent boundary-layer fluctuations can be decomposed into a range of frequencies via Fourier analysis. The linear nature of the investigated problem allows their superposition, not restricting the generality of boundary-layer-edge fluctuation conditions. These unsteady fluctuations could occur due to electrical power supplies varying in input power, turbulent fluctuations in the flow, flow entrainment and large scale eddies, etc. (Hermann et al. Reference Hermann, Löhle, Fasoulas and Andrianatos2016; Capponi et al. Reference Capponi, Padovan, Elliott, Panesi, Bodony and Panerai2024). The boundary-layer profile will consist of a steady-state mean profile and a superimposed oscillating component, due to the linearity of (2.8). The employed solution (2.9) considers only the transient behaviour and omits the superimposed steady-state contribution. This simplifies the solution slightly and does not restrict the generality of the approach. Additionally, this simplifies the boundary-layer-edge condition to

$\Delta z_\infty$

is imposed originating from concentration fluctuations in the free stream. A single frequency is investigated, as arbitrary time-dependent boundary-layer fluctuations can be decomposed into a range of frequencies via Fourier analysis. The linear nature of the investigated problem allows their superposition, not restricting the generality of boundary-layer-edge fluctuation conditions. These unsteady fluctuations could occur due to electrical power supplies varying in input power, turbulent fluctuations in the flow, flow entrainment and large scale eddies, etc. (Hermann et al. Reference Hermann, Löhle, Fasoulas and Andrianatos2016; Capponi et al. Reference Capponi, Padovan, Elliott, Panesi, Bodony and Panerai2024). The boundary-layer profile will consist of a steady-state mean profile and a superimposed oscillating component, due to the linearity of (2.8). The employed solution (2.9) considers only the transient behaviour and omits the superimposed steady-state contribution. This simplifies the solution slightly and does not restrict the generality of the approach. Additionally, this simplifies the boundary-layer-edge condition to

![]() $ z(\delta _c) = \Delta z_\infty \cos (\omega t)$

. At the wall, a material with catalytic recombination coefficient

$ z(\delta _c) = \Delta z_\infty \cos (\omega t)$

. At the wall, a material with catalytic recombination coefficient

![]() $\gamma$

is assumed to be present. The factor

$\gamma$

is assumed to be present. The factor

![]() $\sigma$

relates to this via

$\sigma$

relates to this via

\begin{equation} \sigma = \frac { {\textit{Sc}} \, K_w }{\mu _w} \sqrt {\frac {2 C \rho _e \mu _e}{(1+\epsilon ) \beta }}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \sigma = \frac { {\textit{Sc}} \, K_w }{\mu _w} \sqrt {\frac {2 C \rho _e \mu _e}{(1+\epsilon ) \beta }}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $\mu$

is the dynamic viscosity,

$\mu$

is the dynamic viscosity,

![]() $\rho$

is the density, and

$\rho$

is the density, and

![]() $K_w$

is the speed of atom recombination at the surface,

$K_w$

is the speed of atom recombination at the surface,

The factor

![]() $\sigma$

can be interpreted as an inverse non-dimensional length scale, denoted as

$\sigma$

can be interpreted as an inverse non-dimensional length scale, denoted as

Fully catalytic surface conditions (all incoming atoms recombine) results in a very small

![]() $l_w$

, while non-catalytic conditions result in an infinity large

$l_w$

, while non-catalytic conditions result in an infinity large

![]() $l_w$

.

$l_w$

.

The goal of the following analysis is to relate the fluctuation amplitude at the wall

![]() $\Delta z_w$

to the fluctuation amplitude at the boundary-layer edge

$\Delta z_w$

to the fluctuation amplitude at the boundary-layer edge

![]() $\Delta z_\infty$

. To simplify solution (2.9), all terms including

$\Delta z_\infty$

. To simplify solution (2.9), all terms including

![]() $\textrm i$

are dropped, as they do not contribute to the amplitude change, but describe the time-dependent behaviour. This yields for the oscillation amplitudes,

$\textrm i$

are dropped, as they do not contribute to the amplitude change, but describe the time-dependent behaviour. This yields for the oscillation amplitudes,

For the fluctuation amplitude at the wall

![]() $(\eta =0)$

, this simplifies to

$(\eta =0)$

, this simplifies to

with

which can be interpreted as the Stokes-layer thickness of an unsteady concentration problem. This is analogous to other Stokes layers of oscillating transport phenomena, such as momentum and heat (Pal & Chakraborty Reference Pal and Chakraborty2015; Schlichting & Gersten Reference Schlichting and Gersten2017). The Stokes-layer thickness describes a measure for the penetration depth of a wave with frequency

![]() $\omega$

. As the frequency increases, the diffusive inertia of the medium will attenuate the propagation of this wave, decreasing its penetration depth (Hermann Reference Hermann2025). Equation (2.15) describes the relative amplitude of a concentration fluctuation of frequency

$\omega$

. As the frequency increases, the diffusive inertia of the medium will attenuate the propagation of this wave, decreasing its penetration depth (Hermann Reference Hermann2025). Equation (2.15) describes the relative amplitude of a concentration fluctuation of frequency

![]() $\omega$

at the wall. For the case of

$\omega$

at the wall. For the case of

![]() $\omega = 0$

, the Stokes-layer thickness

$\omega = 0$

, the Stokes-layer thickness

![]() $\delta _S$

becomes infinite, yielding the limiting solution of (2.15) as

$\delta _S$

becomes infinite, yielding the limiting solution of (2.15) as

The solution (2.15) relies on the specification of a mass diffusion boundary-layer thickness

![]() $\delta _c$

, representing the interface between boundary layer and inviscid external flow. This boundary-layer thickness is defined in relation to the thermal boundary layer, analogous to Hermann (Reference Hermann2025). In this work, the conduction length,

$\delta _c$

, representing the interface between boundary layer and inviscid external flow. This boundary-layer thickness is defined in relation to the thermal boundary layer, analogous to Hermann (Reference Hermann2025). In this work, the conduction length,

\begin{equation} \delta _{T,L} = \frac {1 - \theta _w}{ \left ( \frac {\partial \theta }{\partial \eta }\right )_w } \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \delta _{T,L} = \frac {1 - \theta _w}{ \left ( \frac {\partial \theta }{\partial \eta }\right )_w } \end{equation}

is considered alongside the thermal-boundary-layer thickness,

\begin{equation} \delta _{T,T} = 2 \frac {1 - \theta _w}{ \left ( \frac {\partial \theta }{\partial \eta }\right )_w }. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \delta _{T,T} = 2 \frac {1 - \theta _w}{ \left ( \frac {\partial \theta }{\partial \eta }\right )_w }. \end{equation}

Here

![]() $\delta _{T,L}$

represents the thickness required for a solid medium to conduct the same heat flux as the boundary layer (Smith & Spalding Reference Smith and Spalding1958; Smith Reference Smith1979);

$\delta _{T,L}$

represents the thickness required for a solid medium to conduct the same heat flux as the boundary layer (Smith & Spalding Reference Smith and Spalding1958; Smith Reference Smith1979);

![]() $\delta _{T,T}$

, instead, represents the thermal-boundary-layer thickness required to fulfil the Reynolds analogy for Prandtl numbers close to unity, if a Pohlhausen velocity–boundary-layer profile is present (Schlichting & Gersten Reference Schlichting and Gersten2017). Using the correlation between mass diffusion and thermal boundary-layer thicknesses found in Dorrance (Reference Dorrance2017) for a Prandtl number close to unity, the diffusion boundary layer is calculated as

$\delta _{T,T}$

, instead, represents the thermal-boundary-layer thickness required to fulfil the Reynolds analogy for Prandtl numbers close to unity, if a Pohlhausen velocity–boundary-layer profile is present (Schlichting & Gersten Reference Schlichting and Gersten2017). Using the correlation between mass diffusion and thermal boundary-layer thicknesses found in Dorrance (Reference Dorrance2017) for a Prandtl number close to unity, the diffusion boundary layer is calculated as

where

![]() $\delta _T$

is determined by either (2.18) or (2.19). A schematic of a typical boundary-layer profile is provided in figure 2, which illustrates the considered length scales. Equation (2.15) developed in this section can be interpreted as a frequency-resolved impulse response of the boundary layer to a change in external flow conditions, if diffusion is the dominant transport mechanism. This approach allows the use of Duhamel’s theorem to superimpose solutions based on arbitrary boundary-layer-edge fluctuations.

$\delta _T$

is determined by either (2.18) or (2.19). A schematic of a typical boundary-layer profile is provided in figure 2, which illustrates the considered length scales. Equation (2.15) developed in this section can be interpreted as a frequency-resolved impulse response of the boundary layer to a change in external flow conditions, if diffusion is the dominant transport mechanism. This approach allows the use of Duhamel’s theorem to superimpose solutions based on arbitrary boundary-layer-edge fluctuations.

Figure 2. Schematic of boundary-layer atomic concentration profile, with characteristic length scales of diffusion problem.

2.3. Reaction-dominated regime

In this regime, the rate of atomic consumption through recombination reactions is far higher than the local rate of change, i.e. the storage term

![]() $({{\textit{Sc}}}/{(1+\epsilon )\beta }) \dot {z}$

is small compared with the reaction term

$({{\textit{Sc}}}/{(1+\epsilon )\beta }) \dot {z}$

is small compared with the reaction term

![]() $({\alpha _e}/{1 + \alpha _e}) {\textit{Da}}\, R(z,\theta )$

. Equation (2.1) is simplified to

$({\alpha _e}/{1 + \alpha _e}) {\textit{Da}}\, R(z,\theta )$

. Equation (2.1) is simplified to

resulting in a quasi-steady solution of the boundary layer. These solutions assume that the influence of boundary-layer-edge conditions is instantaneously transported to the wall. In this case, boundary conditions are

for nominal conditions without external fluctuations, and

for perturbed conditions with perturbation magnitude

![]() $\Delta z_\infty$

. These conditions are identical to the case used in (2.10), apart from dropping the oscillation term. This is due to the fact that an instantaneous transport is assumed, and the temporal rate of change of boundary-layer-edge conditions therefore becomes irrelevant. Extending the work of Inger (Reference Inger1963), a solution to (2.21) is achieved by double integration of (2.21) with an integrating factor of

$\Delta z_\infty$

. These conditions are identical to the case used in (2.10), apart from dropping the oscillation term. This is due to the fact that an instantaneous transport is assumed, and the temporal rate of change of boundary-layer-edge conditions therefore becomes irrelevant. Extending the work of Inger (Reference Inger1963), a solution to (2.21) is achieved by double integration of (2.21) with an integrating factor of

![]() $\exp ( {\textit{Sc}} \int _{0}^{\eta } f \mathrm {d}\eta )$

, yielding

$\exp ( {\textit{Sc}} \int _{0}^{\eta } f \mathrm {d}\eta )$

, yielding

with

where

![]() $z_F$

refers to the frozen boundary-layer profile,

$z_F$

refers to the frozen boundary-layer profile,

![]() $g$

is a boundary layer integral factor, i.e. the solution of the ordinary differential equation

$g$

is a boundary layer integral factor, i.e. the solution of the ordinary differential equation

where the boundary conditions (2.22) and (2.23) also apply to this case. The frozen-wall condition can be determined analytically using Goulard (Reference Goulard1958), by employing a double integration, yielding

with

The integral can be transformed slightly into a new non-dimensional spatial domain

![]() $\tilde {\eta } = \eta / \delta _c$

which equals to unity at the boundary-layer edge:

$\tilde {\eta } = \eta / \delta _c$

which equals to unity at the boundary-layer edge:

\begin{equation} \tilde {I} = \int _{0}^{1} \delta _c \,\exp \left ( - {\textit{Sc}} \int _{0}^{1} f \mathrm {d}\tilde {\eta } \right ) \mathrm {d}\tilde {\eta } = I(\delta _c) /\delta _c. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \tilde {I} = \int _{0}^{1} \delta _c \,\exp \left ( - {\textit{Sc}} \int _{0}^{1} f \mathrm {d}\tilde {\eta } \right ) \mathrm {d}\tilde {\eta } = I(\delta _c) /\delta _c. \end{equation}

This normalisation is conducted to non-dimensionalise the derived solution. Evaluating (2.24) at the wall (

![]() $\eta =0$

) with the nominal (unperturbed) boundary condition

$\eta =0$

) with the nominal (unperturbed) boundary condition

![]() $z_F(\delta _c) = 1$

yields

$z_F(\delta _c) = 1$

yields

Using the perturbed boundary condition

![]() $z_F(\delta _c) = 1 +\Delta z_\infty$

to denote the increase of external concentration by the relative fraction

$z_F(\delta _c) = 1 +\Delta z_\infty$

to denote the increase of external concentration by the relative fraction

![]() $\Delta z_\infty$

, yields the solution

$\Delta z_\infty$

, yields the solution

Quantities denoted by (

![]() $^\Delta$

) relate to boundary conditions (2.23), while all other cases refer to boundary conditions (2.22). Utilising (2.27) and (2.29) yields

$^\Delta$

) relate to boundary conditions (2.23), while all other cases refer to boundary conditions (2.22). Utilising (2.27) and (2.29) yields

Using this, the difference between (2.30) and (2.31), corresponding to the difference in wall concentration for a given boundary-layer-edge concentration perturbation of

![]() $\Delta z_\infty$

, is

$\Delta z_\infty$

, is

The

![]() $g$

-integrals, given with (2.25), are an implicit function of

$g$

-integrals, given with (2.25), are an implicit function of

![]() $z$

, which would require an iterative solution to (2.33). To avoid this recursive solution procedure, an empirical correlation is proposed. It has been found that the approximation

$z$

, which would require an iterative solution to (2.33). To avoid this recursive solution procedure, an empirical correlation is proposed. It has been found that the approximation

gives a satisfactory prediction of the difference between the two integral terms. The accuracy is better than 10.4 % for all investigated cases in this work (see § 3.2 for details). The fraction

![]() $z(0) / z_F(0)$

is mainly a function of Damkoehler number, and can be calculated by solving the nonlinear ordinary differential (2.21) to obtain

$z(0) / z_F(0)$

is mainly a function of Damkoehler number, and can be calculated by solving the nonlinear ordinary differential (2.21) to obtain

![]() $z(0)$

, and utilising (2.32) for

$z(0)$

, and utilising (2.32) for

![]() $z_F(0)$

. Alternatively, this ratio can be determined analytically using Inger (Reference Inger1963) which utilises only steady-state frozen solutions, which is more in keeping with the approach taken in this work. Either way, the final solution for the wall concentration change under quasi-steady conditions is

$z_F(0)$

. Alternatively, this ratio can be determined analytically using Inger (Reference Inger1963) which utilises only steady-state frozen solutions, which is more in keeping with the approach taken in this work. Either way, the final solution for the wall concentration change under quasi-steady conditions is

\begin{equation} \Delta z_w = \Delta z_\infty \frac { \frac {z(0)}{z_F(0)} }{\frac {\delta _c}{l_w} \tilde {I} + 1 } = \Delta z_\infty \, z(0). \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \Delta z_w = \Delta z_\infty \frac { \frac {z(0)}{z_F(0)} }{\frac {\delta _c}{l_w} \tilde {I} + 1 } = \Delta z_\infty \, z(0). \end{equation}

The special cases of diffusion- and reaction-dominated regimes build the basis of the generalised correlation derived in this work, which is presented in the following.

2.4. Generalised correlation

The hypothesis utilised in the current work is based on the assumption that effects due to chemical reactions are separable from diffusion. This allows the formulation of a general correlation:

where

![]() $F_{\textit{Diff.}}$

describes the attenuation of fluctuations due to the inertia of boundary-layer mass transport, and

$F_{\textit{Diff.}}$

describes the attenuation of fluctuations due to the inertia of boundary-layer mass transport, and

![]() $G_{\textit{Chem.}}$

describes the suppression of fluctuations due to chemical reactions, foremost recombination. The variable

$G_{\textit{Chem.}}$

describes the suppression of fluctuations due to chemical reactions, foremost recombination. The variable

![]() $F_{\textit{Diff.}}$

utilises (2.15) normalised by its limit for

$F_{\textit{Diff.}}$

utilises (2.15) normalised by its limit for

![]() $\omega = 0$

, given in (2.17), leading to

$\omega = 0$

, given in (2.17), leading to

\begin{equation} A = \frac {\frac {\Delta z_w}{\Delta z_\infty }|_{\textit{Diff.}} }{ \lim _{\delta _S \to \infty } \frac {\Delta z_w}{\Delta z_\infty }|_{\textit{Diff.}} } = \frac { 2 + 2 \frac {\delta _c}{l_w} }{ \left ( 1 + \frac {\delta _S}{l_w} \right ) \exp \left ( \frac {\delta _c}{\delta _S} \right ) + \left ( 1 - \frac {\delta _S}{l_w} \right ) \exp \left ( -\frac {\delta _c}{\delta _S} \right ) } . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} A = \frac {\frac {\Delta z_w}{\Delta z_\infty }|_{\textit{Diff.}} }{ \lim _{\delta _S \to \infty } \frac {\Delta z_w}{\Delta z_\infty }|_{\textit{Diff.}} } = \frac { 2 + 2 \frac {\delta _c}{l_w} }{ \left ( 1 + \frac {\delta _S}{l_w} \right ) \exp \left ( \frac {\delta _c}{\delta _S} \right ) + \left ( 1 - \frac {\delta _S}{l_w} \right ) \exp \left ( -\frac {\delta _c}{\delta _S} \right ) } . \end{equation}

This function describes the attenuation of mass transport relative to the maximum possible wall value. It is further used to define

\begin{equation} F_{\textit{Diff.}} = A \left ( \delta _{T,L} \right ) - \frac { A\left ( \delta _{T,L} \right ) - A\left ( \delta _{T,T} \right ) }{ 1 + 8.2 \left ( \frac {{\textit{Sc}} \omega }{ \beta (1+\epsilon ) } \right )^{-3} } . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} F_{\textit{Diff.}} = A \left ( \delta _{T,L} \right ) - \frac { A\left ( \delta _{T,L} \right ) - A\left ( \delta _{T,T} \right ) }{ 1 + 8.2 \left ( \frac {{\textit{Sc}} \omega }{ \beta (1+\epsilon ) } \right )^{-3} } . \end{equation}

Equation (2.38) utilises an empirical correlation which is based on the data analysis presented in § 3.1, where respective details are discussed in greater depth. It utilises the definitions in (2.18) and (2.19) for the thermal boundary-layer thickness, which in turn determine the concentration boundary-layer thickness through (2.20). This is finally used in (2.37).

The second term in (2.36), describing wall concentration attenuation due to chemical reactions utilises (2.35):

\begin{equation} G_{\textit{Chem.}} = \frac { \frac {z(0)}{z_F(0)} }{\frac {\delta _c}{l_w} \tilde {I} + 1 } , \end{equation}

\begin{equation} G_{\textit{Chem.}} = \frac { \frac {z(0)}{z_F(0)} }{\frac {\delta _c}{l_w} \tilde {I} + 1 } , \end{equation}

resulting in the full correlation

\begin{equation} \frac {\Delta z_w}{\Delta z_\infty } = \left [ A \left ( \delta _{T,L} \right ) - \frac { A\left ( \delta _{T,L} \right ) - A\left ( \delta _{T,T} \right ) }{ 1 + 8.2 \left ( \frac {{\textit{Sc}} \omega }{ \beta (1+\epsilon ) } \right )^{-3} } \right ] \left [ \frac { \frac {z(0)}{z_F(0)} }{\frac {\delta _c}{l_w} \tilde {I} + 1 } \right ]. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac {\Delta z_w}{\Delta z_\infty } = \left [ A \left ( \delta _{T,L} \right ) - \frac { A\left ( \delta _{T,L} \right ) - A\left ( \delta _{T,T} \right ) }{ 1 + 8.2 \left ( \frac {{\textit{Sc}} \omega }{ \beta (1+\epsilon ) } \right )^{-3} } \right ] \left [ \frac { \frac {z(0)}{z_F(0)} }{\frac {\delta _c}{l_w} \tilde {I} + 1 } \right ]. \end{equation}

The correlation features a few noteworthy properties that give insight into the behaviour of the fluid mechanics. All functions involved are only dependent on the steady-state frozen boundary-layer solution, which can be readily obtained using either simple numerical simulations or classical theory (Goulard Reference Goulard1958; Dorrance Reference Dorrance2017). Another useful aspect is that this correlation retains the linear time-invariant property found in § 2.2. As such, this approach can be viewed as an approximate linearisation of the inherently nonlinear flow physics. The linear time-invariant property allows the calculation of a frequency-resolved impulse response which can then be applied to arbitrary temporal boundary conditions at the boundary-layer edge using Duhamel’s theorem.

Furthermore, several special cases exist for components in correlation (2.40) that lead to substantial simplification. These are (i) either very fast or slow flow oscillations, (ii) fully or non-catalytic surface behaviour and (iii) frozen or fully equilibrated flow. The diffusion term

![]() $A$

depends only on the catalytic and frequency aspects and can be simplified as follows.

$A$

depends only on the catalytic and frequency aspects and can be simplified as follows.

High frequency (small

![]() $\delta _S$

) and fully catalytic wall (small

$\delta _S$

) and fully catalytic wall (small

![]() $l_w$

):

$l_w$

):

\begin{equation} \lim _{\delta _S \to 0, \,\, l_w \to 0} A = \frac { \frac {\delta _c}{l_w} }{ \mathrm{sinh} \left (\frac {\delta _c}{\delta _S} \right ) } . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \lim _{\delta _S \to 0, \,\, l_w \to 0} A = \frac { \frac {\delta _c}{l_w} }{ \mathrm{sinh} \left (\frac {\delta _c}{\delta _S} \right ) } . \end{equation}

High frequency (small

![]() $\delta _S$

) and non-catalytic wall (large

$\delta _S$

) and non-catalytic wall (large

![]() $l_w$

):

$l_w$

):

\begin{equation} \lim _{\delta _S \to 0, \,\, l_w \to \infty } A = \frac { 1 }{ \mathrm{sinh} \left (\frac {\delta _c}{\delta _S} \right ) } . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \lim _{\delta _S \to 0, \,\, l_w \to \infty } A = \frac { 1 }{ \mathrm{sinh} \left (\frac {\delta _c}{\delta _S} \right ) } . \end{equation}

Low frequency (large

![]() $\delta _S$

) and fully catalytic wall (small

$\delta _S$

) and fully catalytic wall (small

![]() $l_w$

):

$l_w$

):

Low frequency (large

![]() $\delta _S$

) and non-catalytic wall (large

$\delta _S$

) and non-catalytic wall (large

![]() $l_w$

):

$l_w$

):

Furthermore, using the fringe cases presented in Inger (Reference Inger1963) for close to frozen conditions (

![]() ${\textit{Da}}\lt \lt 1$

),

${\textit{Da}}\lt \lt 1$

),

where

![]() ${\textit{Da}}^{*}$

is a composite Damkoehler number, as defined in Inger (Reference Inger1963). This number is entirely dependent on steady-state frozen-flow properties. Alternatively close to equilibrium (

${\textit{Da}}^{*}$

is a composite Damkoehler number, as defined in Inger (Reference Inger1963). This number is entirely dependent on steady-state frozen-flow properties. Alternatively close to equilibrium (

![]() ${\textit{Da}}\gt \gt 1$

) conditions can be approximated with

${\textit{Da}}\gt \gt 1$

) conditions can be approximated with

In the following, the individual components of the derivation are investigated with respect to their accuracy for a fully coupled unsteady simulation.

3. Numerical simulation

As the analytically derived model is approximate and employs several simplifications, a comparison with a higher-fidelity model is needed to ensure sufficient accuracy. A fully coupled transient simulation of the boundary layer (2.1) and (2.2) is performed, using the boundary conditions

The following analysis uses an axisymmetric case (

![]() $\epsilon = 1$

), i.e. a flow around a sphere. The numerical simulation includes several effects, which have been assumed as negligible in the derivation, such as full coupling between species and energy conservation equations. The full boundary-layer equations are solved, whereas the analytical work in § 2.2 uses an idealisation of the boundary layer as a solid slab. The impact of these assumptions is investigated by comparing the simplified analytical correlation with an accurate solution of the heat and mass transfer in the coupled boundary layer.

$\epsilon = 1$

), i.e. a flow around a sphere. The numerical simulation includes several effects, which have been assumed as negligible in the derivation, such as full coupling between species and energy conservation equations. The full boundary-layer equations are solved, whereas the analytical work in § 2.2 uses an idealisation of the boundary layer as a solid slab. The impact of these assumptions is investigated by comparing the simplified analytical correlation with an accurate solution of the heat and mass transfer in the coupled boundary layer.

The solution is generated using the Matlab pdepe functionality and is initialised using the steady-state solutions of (2.1) and (2.2). The method of Skeel & Berzins (Reference Skeel and Berzins1990) is used to solve the differential equations, where the solution is iterated until a relative tolerance of

![]() $10^{-4}$

is reached. The equations are solved for a total time corresponding to 10 000 oscillations of the investigated frequency

$10^{-4}$

is reached. The equations are solved for a total time corresponding to 10 000 oscillations of the investigated frequency

![]() $\omega$

. An equidistant mesh of 150 000 points in the time dimension, and 500 points in the spatial dimension is used. A mesh convergence study has been carried out in space and time dimensions where the number of discrete mesh points has been doubled respectively. The solution was insensitive to this with a maximum deviation of 0.015 %. Therefore, the coarser mesh size was used in all following simulations. The solution was validated by comparing the wall value of a frozen-flow condition (

$\omega$

. An equidistant mesh of 150 000 points in the time dimension, and 500 points in the spatial dimension is used. A mesh convergence study has been carried out in space and time dimensions where the number of discrete mesh points has been doubled respectively. The solution was insensitive to this with a maximum deviation of 0.015 %. Therefore, the coarser mesh size was used in all following simulations. The solution was validated by comparing the wall value of a frozen-flow condition (

![]() $Da=0$

) to (2.27), which is an exact solution of the frozen boundary layer. The simulated value showed a deviation of 0.0013 % from the analytical value. The unsteady solver has been further validated in Hermann (Reference Hermann2025) using exact solutions of the boundary-layer energy equation, yielding a maximum difference of 0.009 % between simulation and exact solution.

$Da=0$

) to (2.27), which is an exact solution of the frozen boundary layer. The simulated value showed a deviation of 0.0013 % from the analytical value. The unsteady solver has been further validated in Hermann (Reference Hermann2025) using exact solutions of the boundary-layer energy equation, yielding a maximum difference of 0.009 % between simulation and exact solution.

Figure 3. Numerical simulation with

![]() ${\textit{Da}} = 10^{-5}$

and

${\textit{Da}} = 10^{-5}$

and

![]() $\sigma = 10^{-2}$

. This flow condition is close to frozen and non-catalytic.

$\sigma = 10^{-2}$

. This flow condition is close to frozen and non-catalytic.

Figure 4. Numerical simulation with

![]() ${\textit{Da}} = 10^{-5}$

and

${\textit{Da}} = 10^{-5}$

and

![]() $\sigma = 10^{4}$

. This flow condition is close to frozen and fully catalytic.

$\sigma = 10^{4}$

. This flow condition is close to frozen and fully catalytic.

Figure 5. Numerical simulation with

![]() ${\textit{Da}} = 10^{1}$

and

${\textit{Da}} = 10^{1}$

and

![]() $\sigma = 10^{-2}$

. This flow condition is close to equilibrium and non-catalytic.

$\sigma = 10^{-2}$

. This flow condition is close to equilibrium and non-catalytic.

Figure 6. Numerical simulation with

![]() ${\textit{Da}} = 10^{1}$

and

${\textit{Da}} = 10^{1}$

and

![]() $\sigma = 10^{4}$

. This flow condition is close to equilibrium and fully catalytic.

$\sigma = 10^{4}$

. This flow condition is close to equilibrium and fully catalytic.

Four example cases are given to illustrate the possible flow behaviour. In each case, the non-dimensional frequency was

![]() $ ( {\textit{Sc}} \,\omega ) / ( (1+\epsilon ) \beta ) = 1.67$

, the free-stream fluctuation amplitude was

$ ( {\textit{Sc}} \,\omega ) / ( (1+\epsilon ) \beta ) = 1.67$

, the free-stream fluctuation amplitude was

![]() $\Delta z_\infty = 0.1$

, the dissociation temperature was

$\Delta z_\infty = 0.1$

, the dissociation temperature was

![]() $\theta _D = 10$

, the reaction exponent was

$\theta _D = 10$

, the reaction exponent was

![]() $\xi = -1.5$

, the wall temperature was

$\xi = -1.5$

, the wall temperature was

![]() $\theta _w = 0.15$

, the Schmidt and Prandtl numbers were

$\theta _w = 0.15$

, the Schmidt and Prandtl numbers were

![]() ${\textit{Sc}} = 0.5$

and

${\textit{Sc}} = 0.5$

and

![]() ${\textit{Pr}} = 0.71$

, the boundary-layer-edge atomic mass fraction was

${\textit{Pr}} = 0.71$

, the boundary-layer-edge atomic mass fraction was

![]() $\alpha _e = 0.6$

, the velocity gradient was

$\alpha _e = 0.6$

, the velocity gradient was

![]() $\beta = 7500\,\textrm {s}^{-1}$

, the molecular specific gas constant was

$\beta = 7500\,\textrm {s}^{-1}$

, the molecular specific gas constant was

![]() $R_M=287\,\textrm {J}\,\textrm {kg}^{-1}\,\textrm {K}^{-1}$

, and the molecular specific heat at constant pressure was

$R_M=287\,\textrm {J}\,\textrm {kg}^{-1}\,\textrm {K}^{-1}$

, and the molecular specific heat at constant pressure was

![]() $c_{p,M}=1004.5 \,\textrm {J}\,\textrm {kg}^{-1}\,\textrm {K}^{-1}$

. The parameters investigated are representative of an air flow. It is assumed that the gas properties are constant with temperature, to allow a comparison between the simplified derived theory and the accurate numerical solution of the governing equations. Temperature-dependent properties would introduce additional sources of uncertainty which is beyond the scope of the current work.

$c_{p,M}=1004.5 \,\textrm {J}\,\textrm {kg}^{-1}\,\textrm {K}^{-1}$

. The parameters investigated are representative of an air flow. It is assumed that the gas properties are constant with temperature, to allow a comparison between the simplified derived theory and the accurate numerical solution of the governing equations. Temperature-dependent properties would introduce additional sources of uncertainty which is beyond the scope of the current work.

Figures 3 to 6 show the concentration profile from the boundary-layer edge (

![]() $\eta \approx 6)$

to the wall (

$\eta \approx 6)$

to the wall (

![]() $\eta = 0$

). The investigated cases correspond to either frozen or equilibrium chemistry, and an either fully or non-catalytic surface. The steady-state solution of the unperturbed boundary-layer profile is presented alongside several instantaneous contours of the perturbed unsteady boundary-layer profile. The wall oscillation magnitude

$\eta = 0$

). The investigated cases correspond to either frozen or equilibrium chemistry, and an either fully or non-catalytic surface. The steady-state solution of the unperturbed boundary-layer profile is presented alongside several instantaneous contours of the perturbed unsteady boundary-layer profile. The wall oscillation magnitude

![]() $\Delta z_w$

at

$\Delta z_w$

at

![]() $\eta =0$

is extracted and will be used in the subsequent analysis.

$\eta =0$

is extracted and will be used in the subsequent analysis.

3.1. Investigation of diffusion-dominated regime

This section concentrates on the special case of a diffusion-dominated regime, described in § 2.2. For these simulations, the Damkoehler number is set to zero, excluding any influence of chemical reactions in the boundary layer. As described in the previous section, the amplitude of the concentration fluctuation

![]() $\Delta z_w$

is extracted and normalised by the amplitude imposed through the boundary-layer-edge condition

$\Delta z_w$

is extracted and normalised by the amplitude imposed through the boundary-layer-edge condition

![]() $\Delta z_\infty$

. This ratio describes the attenuation of these fluctuations, which is investigated for a variety of different test cases. The parameters summarised in § 3 are used, while the following parameters are varied to facilitate a range of different flow conditions. (i) The free-stream oscillation frequency

$\Delta z_\infty$

. This ratio describes the attenuation of these fluctuations, which is investigated for a variety of different test cases. The parameters summarised in § 3 are used, while the following parameters are varied to facilitate a range of different flow conditions. (i) The free-stream oscillation frequency

![]() $\omega$

was varied in 20 steps between

$\omega$

was varied in 20 steps between

![]() $10^{1.5}$

s

$10^{1.5}$

s

![]() $^{-1}$

and

$^{-1}$

and

![]() $10^{6}$

s

$10^{6}$

s

![]() $^{-1}$

, keeping an equidistant logarithmic spacing. (ii) The wall temperature

$^{-1}$

, keeping an equidistant logarithmic spacing. (ii) The wall temperature

![]() $\theta _w$

was varied in 6 steps between

$\theta _w$

was varied in 6 steps between

![]() $0.01$

and

$0.01$

and

![]() $0.35$

, keeping a linear equidistant spacing. (iii) The wall catalycity factor

$0.35$

, keeping a linear equidistant spacing. (iii) The wall catalycity factor

![]() $\sigma$

was varied in 6 steps between

$\sigma$

was varied in 6 steps between

![]() $10^{-2}$

and

$10^{-2}$

and

![]() $10^{4}$

, keeping an equidistant logarithmic spacing. This resulted in

$10^{4}$

, keeping an equidistant logarithmic spacing. This resulted in

![]() $20 \times 6 \times 6 = 720$

unique transient numerical simulations.

$20 \times 6 \times 6 = 720$

unique transient numerical simulations.

Figure 7. Comparison between analytical correlation (2.15) and numerical simulation results for variations of wall temperature

![]() $\theta _w$

and surface catalycity

$\theta _w$

and surface catalycity

![]() $\sigma$

.

$\sigma$

.

The results for the normalised wall-fluctuation amplitude are shown as circles in figure 7, and are compared with the analytical solution (2.15) where either the conduction or thermal-boundary-layer thicknesses given in (2.18) and (2.19) are used as the boundary-layer reference length. For small frequencies, the Stokes-layer thickness is large and penetrates deep into or beyond the boundary-layer thickness. This means that the fluctuations are not attenuated by the boundary layer whatsoever. As frequencies become larger, the diffusive inertia of the boundary layer rapidly attenuates the magnitude of the fluctuation. This behaviour is entirely analogous to the classical second Stokes problem in momentum and heat transfer, an unsurprising observation as the partial differential equations are identical, albeit with different transport properties (Schlichting & Gersten Reference Schlichting and Gersten2017; Hermann Reference Hermann2025). The second observation relates to the strong influence of the surface catalycity. For small frequencies, a close to non-catalytic surface (e.g.

![]() $\sigma = 0.01$

) results in a full transmission of the fluctuations to the wall, i.e.

$\sigma = 0.01$

) results in a full transmission of the fluctuations to the wall, i.e.

![]() $\Delta z_w/\Delta z_\infty \approx 1$

. The limiting maximum value for each catalycity factor

$\Delta z_w/\Delta z_\infty \approx 1$

. The limiting maximum value for each catalycity factor

![]() $\sigma$

can be determined via (2.17). If the surface tends towards higher catalytic efficiency, this maximum possible value decreases significantly. At

$\sigma$

can be determined via (2.17). If the surface tends towards higher catalytic efficiency, this maximum possible value decreases significantly. At

![]() $\sigma = 10\,000$

, the fluctuation magnitude at the wall is over four orders of magnitude lower than the corresponding free-stream value. The reason for this behaviour is the fast consumption of atoms at the surface. Even in cases of low-frequency oscillations, where the diffusive inertia is small, atoms are immediately consumed through wall recombination reactions. These reactions, controlled through the boundary condition

$\sigma = 10\,000$

, the fluctuation magnitude at the wall is over four orders of magnitude lower than the corresponding free-stream value. The reason for this behaviour is the fast consumption of atoms at the surface. Even in cases of low-frequency oscillations, where the diffusive inertia is small, atoms are immediately consumed through wall recombination reactions. These reactions, controlled through the boundary condition

![]() $z'(0)= \sigma z(0)$

, drive a strong concentration gradient to the surface supplying this flux of atoms. This behaviour is illustrated in the boundary-layer profile of figure 4. The fast consumption of atoms suppresses any significant fluctuations and therefore leads to extremely small

$z'(0)= \sigma z(0)$

, drive a strong concentration gradient to the surface supplying this flux of atoms. This behaviour is illustrated in the boundary-layer profile of figure 4. The fast consumption of atoms suppresses any significant fluctuations and therefore leads to extremely small

![]() $\Delta z_w/\Delta z_\infty$

values. Lastly, the wall temperature variation has no influence whatsoever. Each plotted datapoint is in fact six points with different

$\Delta z_w/\Delta z_\infty$

values. Lastly, the wall temperature variation has no influence whatsoever. Each plotted datapoint is in fact six points with different

![]() $\theta _w$

values sharing the identical

$\theta _w$

values sharing the identical

![]() $\Delta z_w/\Delta z_\infty$

value. This is unsurprising, as the only coupling between energy and mass diffusion equations occurs via the reaction term

$\Delta z_w/\Delta z_\infty$

value. This is unsurprising, as the only coupling between energy and mass diffusion equations occurs via the reaction term

![]() $R(z,\theta )$

, controlled by the magnitude of the Damkoehler number. As

$R(z,\theta )$

, controlled by the magnitude of the Damkoehler number. As

![]() ${\textit{Da}} = 0$

is used in these cases, this coupling is absent. It is, however, noteworthy that the different values of wall temperature also do not have an effect on the thermal-boundary-layer thickness, calculated via (2.18) or (2.19). This is apparent as the analytical correlation (2.15) is equally unaffected by the choice of

${\textit{Da}} = 0$

is used in these cases, this coupling is absent. It is, however, noteworthy that the different values of wall temperature also do not have an effect on the thermal-boundary-layer thickness, calculated via (2.18) or (2.19). This is apparent as the analytical correlation (2.15) is equally unaffected by the choice of

![]() $\theta _w$

.

$\theta _w$

.

Figure 7 also shows how correlation (2.15) compares against the simulations. If the conduction layer thickness

![]() $\delta _{T,L}$

is chosen, the correlation agrees extremely well for cases where the Stokes-layer thickness is large, i.e. for low frequencies. In this regime, the modelling of the boundary layer as a solid diffusion slug provides a very good approximation. If the Stokes layer is smaller, i.e. for high frequencies, the data points tend to be better correlated by using the thermal-boundary-layer thickness

$\delta _{T,L}$

is chosen, the correlation agrees extremely well for cases where the Stokes-layer thickness is large, i.e. for low frequencies. In this regime, the modelling of the boundary layer as a solid diffusion slug provides a very good approximation. If the Stokes layer is smaller, i.e. for high frequencies, the data points tend to be better correlated by using the thermal-boundary-layer thickness

![]() $\delta _{T,T}$

. This behaviour is again analogous to thermal-boundary-layer oscillations as shown in Hermann (Reference Hermann2025), where additional discussion is provided on this topic. If each case of a given

$\delta _{T,T}$

. This behaviour is again analogous to thermal-boundary-layer oscillations as shown in Hermann (Reference Hermann2025), where additional discussion is provided on this topic. If each case of a given

![]() $\sigma$

is normalised by its maximum possible value given in (2.17), the simulated data collapses to a single function. This behaviour motivates the use of an empirical bridging function that connects the asymptotes of

$\sigma$

is normalised by its maximum possible value given in (2.17), the simulated data collapses to a single function. This behaviour motivates the use of an empirical bridging function that connects the asymptotes of

![]() $\delta _{T} = \delta _{T,T}$

for high frequencies and

$\delta _{T} = \delta _{T,T}$

for high frequencies and

![]() $\delta _{T} = \delta _{T,L}$

for low frequencies. It is found that (2.38) follows the numerical data points within reasonable accuracy. The bridging function is shown for each simulated case as a dotted line in figure 7. The correlation becomes less accurate at high frequencies. However, at that point the boundary layer attenuates the propagation of oscillations so severely that these values have no practical significance due to their extremely small magnitude. The correlation provides a good fit for all investigated cases.

$\delta _{T} = \delta _{T,L}$

for low frequencies. It is found that (2.38) follows the numerical data points within reasonable accuracy. The bridging function is shown for each simulated case as a dotted line in figure 7. The correlation becomes less accurate at high frequencies. However, at that point the boundary layer attenuates the propagation of oscillations so severely that these values have no practical significance due to their extremely small magnitude. The correlation provides a good fit for all investigated cases.

3.2. Investigation of reaction-dominated regime

In this section, the accuracy of the approximate theory derived in § 2.3 is investigated. This is achieved by numerically solving (2.21) and extracting the magnitude of the wall concentration. This procedure is carried out with boundary conditions

where

![]() $\Delta z_\infty$

is either finite to investigate the perturbed case, or zero to investigate the nominal case. The difference between the two respective wall values is denoted

$\Delta z_\infty$

is either finite to investigate the perturbed case, or zero to investigate the nominal case. The difference between the two respective wall values is denoted

![]() $\Delta z_w$

. In contrast to the analysis, these simulations are steady-state cases and simulate a situation where the boundary layer reacts infinitely fast to changes imposed by the free stream. Due to the coupling of energy and mass diffusion equations, this test case is highly nonlinear and depends on a variety of different parameters. To assess the approximate solution (2.35) against the fully coupled numerical solution, a base test case is constructed with the following values:

$\Delta z_w$

. In contrast to the analysis, these simulations are steady-state cases and simulate a situation where the boundary layer reacts infinitely fast to changes imposed by the free stream. Due to the coupling of energy and mass diffusion equations, this test case is highly nonlinear and depends on a variety of different parameters. To assess the approximate solution (2.35) against the fully coupled numerical solution, a base test case is constructed with the following values:

![]() $\Delta z_\infty = 0.1$

,

$\Delta z_\infty = 0.1$

,

![]() $\theta _D = 10$

,

$\theta _D = 10$

,

![]() $\xi = -1.5$

,

$\xi = -1.5$

,

![]() $\theta _w = 0.15$

,

$\theta _w = 0.15$

,

![]() $\sigma = 0.1$

,

$\sigma = 0.1$

,

![]() ${\textit{Sc}} = 0.5$

,

${\textit{Sc}} = 0.5$

,

![]() ${\textit{Pr}} = 0.71$

,

${\textit{Pr}} = 0.71$

,

![]() $\alpha _e = 0.6$

,

$\alpha _e = 0.6$

,

![]() $\beta = 7500$

s

$\beta = 7500$

s

![]() $^{-1}$

,

$^{-1}$

,

![]() $R_M=287$

J kg

$R_M=287$

J kg

![]() $^{-1}$

K

$^{-1}$

K

![]() $^{-1}$

,

$^{-1}$

,

![]() $c_{p,M}=1004.5$

J kg

$c_{p,M}=1004.5$

J kg

![]() $^{-1}$

K

$^{-1}$

K

![]() $^{-1}$

. Of this set of values

$^{-1}$

. Of this set of values

![]() $\sigma$

,

$\sigma$

,

![]() $\alpha _e$

,

$\alpha _e$

,

![]() $\theta _D$

and

$\theta _D$

and

![]() $\theta _w$

are varied one at a time. For instance, the wall temperature

$\theta _w$

are varied one at a time. For instance, the wall temperature

![]() $\theta _w$

is varied between 0.01 and 0.35 in six equally spaced intervals. For each of these intervals, the Damkoehler number is varied between

$\theta _w$

is varied between 0.01 and 0.35 in six equally spaced intervals. For each of these intervals, the Damkoehler number is varied between

![]() $10^{-5}$

and

$10^{-5}$

and

![]() $10^{3.2}$

with 25 logarithmically equal spacings. This results in a set of

$10^{3.2}$

with 25 logarithmically equal spacings. This results in a set of

![]() $25 \times 6 \times 4 = 600$

unique solutions.

$25 \times 6 \times 4 = 600$

unique solutions.

The results of these simulations and the respective comparison with correlation (2.35) is shown in figure 8. In all cases, a significant influence of the Damkoehler number on the relative wall concentration augmentation

![]() $\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

is evident. Small Damkoehler numbers, where the flow can be considered frozen, do not affect the wall concentration in most cases. In the frozen-flow domain, chemical reactions do not take part and an exact solution of the wall concentration can be obtained with (2.32). These wall conditions depend only on the catalytic wall value

$\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

is evident. Small Damkoehler numbers, where the flow can be considered frozen, do not affect the wall concentration in most cases. In the frozen-flow domain, chemical reactions do not take part and an exact solution of the wall concentration can be obtained with (2.32). These wall conditions depend only on the catalytic wall value

![]() $\sigma$

, the boundary-layer thickness

$\sigma$

, the boundary-layer thickness

![]() $\delta _c$

, the Blasius function

$\delta _c$

, the Blasius function

![]() $f$

and the Schmidt number

$f$

and the Schmidt number

![]() $Sc$

. This is the reason why several solutions become degenerate for small Damkoehler numbers (see figure 8

a,b). Large Damkoehler numbers suggest a flow close to chemical equilibrium. Under these conditions, any deviation from the nominal boundary-layer profile is immediately suppressed by recombination reactions, hence reducing

$Sc$

. This is the reason why several solutions become degenerate for small Damkoehler numbers (see figure 8

a,b). Large Damkoehler numbers suggest a flow close to chemical equilibrium. Under these conditions, any deviation from the nominal boundary-layer profile is immediately suppressed by recombination reactions, hence reducing

![]() $\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

significantly. The local equilibrium condition is mainly influenced by the temperature

$\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

significantly. The local equilibrium condition is mainly influenced by the temperature

![]() $\theta$

. Even though the temperature distribution

$\theta$

. Even though the temperature distribution

![]() $\theta (\eta )$

changes under perturbed external conditions, this effect is only weak and the frozen temperature

$\theta (\eta )$

changes under perturbed external conditions, this effect is only weak and the frozen temperature

![]() $\theta _F(\eta )$

distribution is a good approximation in all considered cases (Inger Reference Inger1963).

$\theta _F(\eta )$

distribution is a good approximation in all considered cases (Inger Reference Inger1963).

Figure 8. Comparison between analytical correlation (2.35) and numerical simulation results for variations of different domain properties. (a) Boundary-layer-edge atomic mass fraction

![]() $\alpha e$

, (b) Dissociation temperature

$\alpha e$

, (b) Dissociation temperature

![]() $\theta D$

, (c) Wall temperature

$\theta D$

, (c) Wall temperature

![]() $\theta w$

, and (d) Wall catalycity

$\theta w$

, and (d) Wall catalycity

![]() $\sigma$

.

$\sigma$

.

Figures 8(a) and 8(c) reveal that the boundary-layer-edge atomic mass fraction

![]() $\alpha _e$

and the dissociation temperature

$\alpha _e$

and the dissociation temperature

![]() $\theta _D$

affect

$\theta _D$

affect

![]() $\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

only weakly. Some deviation from the correlation is seen for smaller values of

$\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

only weakly. Some deviation from the correlation is seen for smaller values of

![]() $\theta _D$

which occur for Damkoehler numbers greater than

$\theta _D$

which occur for Damkoehler numbers greater than

![]() $10^{-2}$

. However, overall the agreement between correlation (2.35) and the numerical solution is good. Figure 8(b) reveals that the wall temperature exerts a significant influence on

$10^{-2}$

. However, overall the agreement between correlation (2.35) and the numerical solution is good. Figure 8(b) reveals that the wall temperature exerts a significant influence on

![]() $\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

. In fact, the curve shown for

$\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

. In fact, the curve shown for

![]() $\theta _w = 0.01$

, corresponding to a highly cooled wall, provides the only aberration from the trend of degenerate solutions at small Damkoehler numbers. Low temperatures near the wall significantly increase the reaction term given in (2.6), where the term

$\theta _w = 0.01$

, corresponding to a highly cooled wall, provides the only aberration from the trend of degenerate solutions at small Damkoehler numbers. Low temperatures near the wall significantly increase the reaction term given in (2.6), where the term

![]() $\theta ^{\xi -2}$

dominates. This nonlinear term results in such a strong rate of recombination that even small Damkoehler numbers lead to significant changes in the atomic wall concentration. It can be observed that the point where

$\theta ^{\xi -2}$

dominates. This nonlinear term results in such a strong rate of recombination that even small Damkoehler numbers lead to significant changes in the atomic wall concentration. It can be observed that the point where

![]() $\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

deviates from

$\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

deviates from

![]() $1$

is delayed to larger Damkoehler numbers as the wall temperature is increased. This occurs as the larger wall temperature results in a smaller

$1$

is delayed to larger Damkoehler numbers as the wall temperature is increased. This occurs as the larger wall temperature results in a smaller

![]() $R(z,\theta )$

and a larger Damkoehler number is needed to affect the flow. The largest influence on

$R(z,\theta )$

and a larger Damkoehler number is needed to affect the flow. The largest influence on

![]() $\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

is exerted by the wall catalycity factor

$\Delta z_w / \Delta z_\infty$

is exerted by the wall catalycity factor

![]() $\sigma$

, as seen in figure 8(d). As discussed in § 3.1, highly catalytic surfaces lead to a significant suppression of the wall concentration augmentation. Overall, given the wide and diverse range of flow conditions investigated, correlation (2.35) provides a very good fit to the numerical data for the majority of cases.

$\sigma$

, as seen in figure 8(d). As discussed in § 3.1, highly catalytic surfaces lead to a significant suppression of the wall concentration augmentation. Overall, given the wide and diverse range of flow conditions investigated, correlation (2.35) provides a very good fit to the numerical data for the majority of cases.

3.3. Investigation of fully coupled unsteady behaviour

Figure 9. Comparison between analytical correlation (2.40) and numerical simulation results. (a) For variation in Da,(b) For variation in

![]() $\delta c/\delta S$

,(c) For variation in

$\delta c/\delta S$

,(c) For variation in

![]() $\delta c/lw$

and (d) For variation in

$\delta c/lw$

and (d) For variation in

![]() $\delta S/lw$

.

$\delta S/lw$

.

In this section, the full unsteady problem given in (2.1) and (2.2) with boundary conditions

is solved numerically. Based on the two previous sections, it is found that the most impactful parameters controlling the wall concentration are the oscillation frequency

![]() $\omega$

, the Damkoehler number

$\omega$

, the Damkoehler number

![]() $Da$

, the wall catalycity factor

$Da$

, the wall catalycity factor

![]() $\sigma$

, and the wall temperature

$\sigma$

, and the wall temperature

![]() $\theta _w$

. The four parameters are varied with

$\theta _w$

. The four parameters are varied with

![]() $10^{-2}\lt \omega \lt 10^{6}$

;

$10^{-2}\lt \omega \lt 10^{6}$

;

![]() $10^{-5}\lt {\textit{Da}}\lt 10^{3.2}$

;

$10^{-5}\lt {\textit{Da}}\lt 10^{3.2}$

;

![]() $10^{-2}\lt \sigma \lt 10^{4}$

;

$10^{-2}\lt \sigma \lt 10^{4}$

;

![]() $0.01\lt \theta _w\lt 0.35$

, each probing 10 values in the respective range. Every possible combination is tested resulting in

$0.01\lt \theta _w\lt 0.35$

, each probing 10 values in the respective range. Every possible combination is tested resulting in

![]() $10^4 = 10\,000$

unique transient simulations. The remaining salient parameters are

$10^4 = 10\,000$

unique transient simulations. The remaining salient parameters are

![]() $\Delta z_\infty = 0.1$

,

$\Delta z_\infty = 0.1$

,

![]() $\theta _D = 10$

,

$\theta _D = 10$

,

![]() $\xi = -1.5$

,

$\xi = -1.5$

,

![]() ${\textit{Sc}} = 0.5$

,

${\textit{Sc}} = 0.5$

,

![]() ${\textit{Pr}} = 0.71$

,

${\textit{Pr}} = 0.71$

,

![]() $\alpha _e = 0.6$

,

$\alpha _e = 0.6$

,

![]() $\beta = 7500\,\textrm {s}^{-1}$

,

$\beta = 7500\,\textrm {s}^{-1}$

,

![]() $R_M=287\,\textrm {J}\,\textrm {kg}^{-1}\,\textrm {K}^{-1}$

,

$R_M=287\,\textrm {J}\,\textrm {kg}^{-1}\,\textrm {K}^{-1}$

,

![]() $c_{p,M}=1004.5\,\textrm {J}\,\textrm {kg}^{-1}\,\textrm {K}^{-1}$

.

$c_{p,M}=1004.5\,\textrm {J}\,\textrm {kg}^{-1}\,\textrm {K}^{-1}$

.

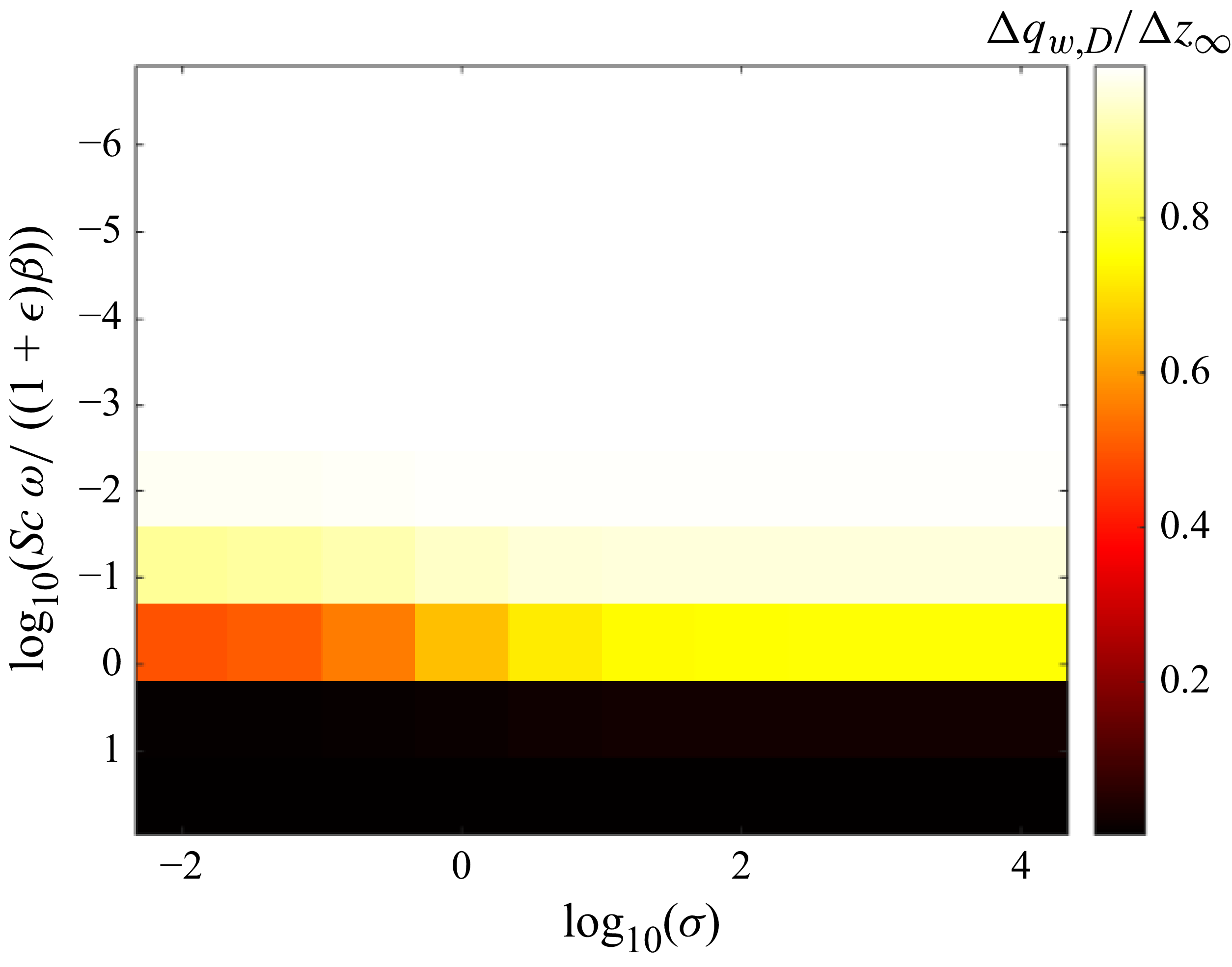

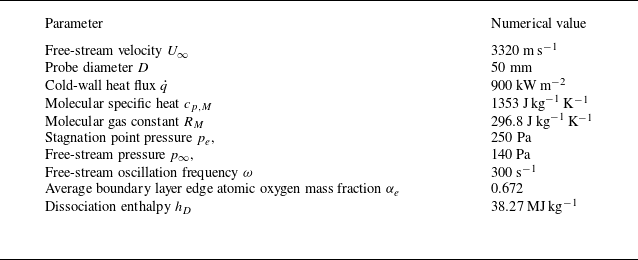

The correlation in (2.40) reveals that the problem is mostly dependent on four non-dimensional parameters: the three length-scale ratios