In many contemporary migration societies, an increasing percentage of residents do not have suffrage. This also holds true for the city of Vienna. In the 2020 municipal elections, almost a third of the Viennese population was excluded from suffrage; this rate of exclusion had doubled since 2000 (Mokre and Ehs Reference Mokre and Ehs2021, 716). At the same time, Vienna has a long history of deliberative practices and experiments. A first deliberative experiment dates back to 1990, when a “Forum City Constitution” was initiated by the City Council to discuss the reform of citizens’ participation (Haas et al. Reference Haas, Moussa-Lipp, Verlič, Ehs and Zandonella2024, 20). This forum did not lead to concrete political effects, and the deliberative turn reached Vienna only after 2000. Other deliberative practices have been introduced over time. Many of these instruments allow for the participation of the entire resident population irrespective of individuals’ voting rights; however, most of them are neither legally prescribed nor legally binding. These are the most inclusive instruments, and many of them allow people who ordinarily lack voting rights to participate. Normatively, this inclusion can be evaluated positively for two reasons: (1) some form of inclusion of the whole population in democratic decision making is desirable (Bauböck Reference Bauböck, Leiser and Campbell2001; Gherghina, Mokre, and Mișcoiu Reference Gherghina, Mokre and Mișcoiu2021); and (2) deliberative practices arguably improve the quality of democracies by broadening inclusion, increasing the efficacy of political decisions, and contributing to civic education (Gherghina and Jacquet Reference Gherghina and Jacquet2023, 504).

Thus, although people without voting rights are given the opportunity of political participation, it frequently remains powerless and cannot replace actual suffrage (Mokre and Ehs Reference Mokre and Ehs2021, 715–16; Pateman Reference Pateman2012). This is due not only to the strong democratic legitimacy and clearcut political impact of voting but also because political parties shape their programs to appeal to potential voters and tend to neglect the interests of people without suffrage. However, this does not imply that deliberative practices do not affect both the general population and political parties. They can be expected to encourage the population to politically participate as well as to convey the opinions and interests of residents to political parties (Gherghina Reference Gherghina2024; Gherghina and Jacquet Reference Gherghina and Jacquet2023). This consideration was the starting point of the project, “If No Vote, at Least Voice,” which combined deliberation among people without suffrage with a popular form of publishing and comparing the political positions of political parties and the citizenry. The project took place during campaigning for the 2020 Viennese elections.

This article answers the research question: How far can deliberative practices compensate for a lack of voting rights by impacting the activities and attitudes of political parties? The study discusses the positions of Viennese political parties regarding deliberative practices and the suffrage of noncitizens as well as the outcomes of the project, “If No Vote, at Least Voice.” On this basis, the article draws conclusions about the interest of political parties in deliberations that include noncitizens. Empirically, the project is based on election and party programs and media coverage of the 2020 Viennese elections and includes the results of the project.

POLITICAL PARTIES AND VOTING RIGHTS IN VIENNA

Legally, Vienna is not only a municipality but also a federal province of Austria; therefore, the Vienna City Council is also a legislative assembly. Pursuant to the Austrian federal constitution, only people with Austrian citizenship are entitled to vote in elections to legislative assemblies. Thus, not only third-country nationals but also non-Austrian citizens from other European Union (EU) countries are excluded from voting in city council elections (Mokre and Ehs Reference Mokre and Ehs2021, 716).

Since 1919, the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPOe) has emerged from every Viennese election as the party with the most votes and, consequently, with a mandate to govern.Footnote 1 Between 1945 and 1973 and between 1996 and 2001, the Christian-conservative Austrian People’s Party (OeVP) was part of the city government; between 2010 and 2020, the Green Party was the junior partner of the SPOe. Since 2020, the SPOe has governed in a coalition with the liberal New Austria and Liberal Forum (NEOS) Party (N.N. 2020; Haas et al. Reference Haas, Moussa-Lipp, Verlič, Ehs and Zandonella2024, 25; Pleschberger, Welan, and Tschirf Reference Pleschberger, Welan, Tschirf and Khol2011).

In 2020, 10 parties were running for election in more than one Viennese district: the SPOe (Social Democrats); the OeVP (conservatives); the Greens; the NEOS (liberal free-market party); the Freedom Party of Austria (FPOe) (right-wing populists); Team HC Strache–Alliance for Austria (HC) (i.e., the party of the former FPOe leader who was forced to leave the FPOe following the Ibiza scandalFootnote 2); LINKS (a new leftist party); the Beer Party (a satirical populist party); Social Austria of the Future (SOeZ) (a new leftist party with ties to the Turkish minority); and Volt Austria (the Austrian branch of the pan-European party).

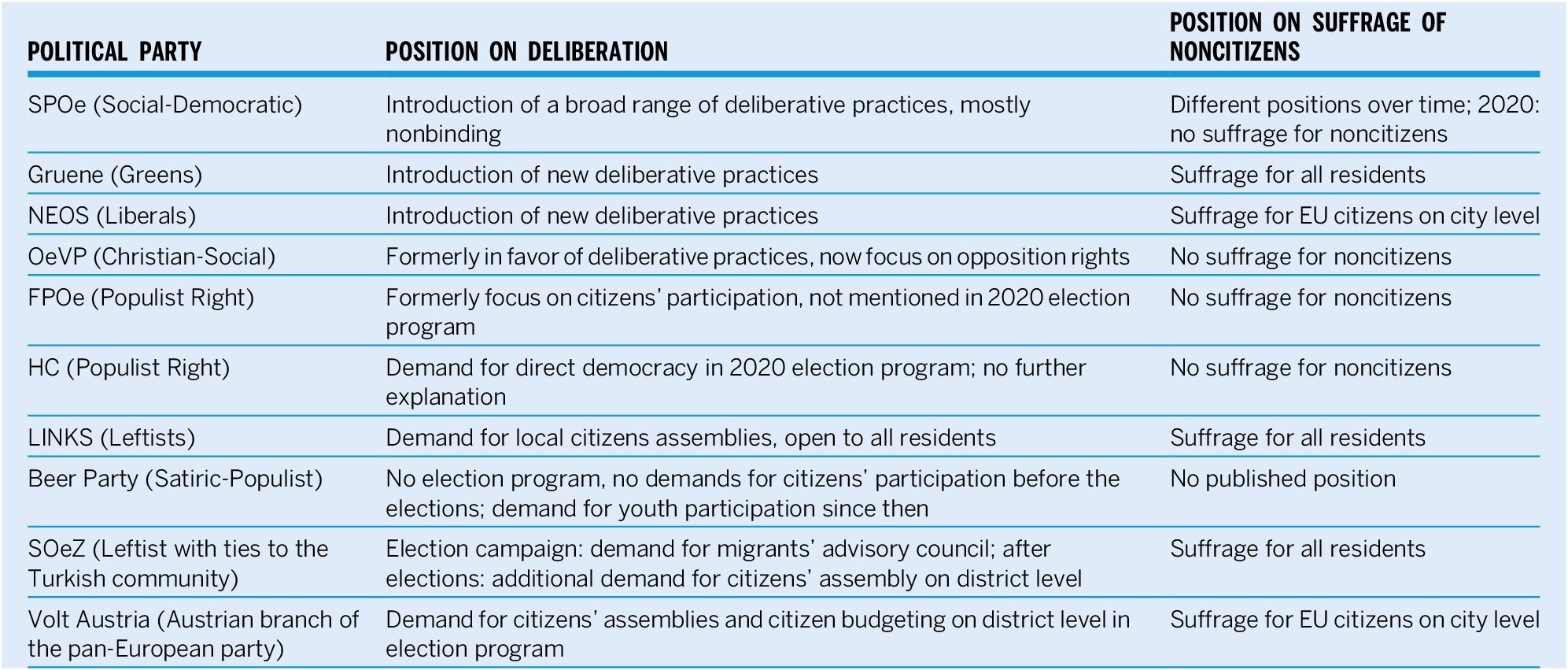

In the context of this analysis, the respective positions of these parties toward deliberative democracy and voting rights for noncitizens are relevant. Regarding the question of deliberative democracy, participatory democracy does not appear to form a priority for Viennese parties. However, at the same time, a certain preference for participatory democracy on the liberal-left wing of the party spectrum can be observed.

All existing forms of citizen participation in Vienna were introduced by a SPOe city government; thus, the multiple forms of citizen participation as well as their relative ineffectiveness can be understood as effects of the SPOe government’s decisions. Since the beginning of its political activities, the Green Party has played an important role in pushing for participatory instruments. In the period of Green Party government participation, a “Participation Masterplan” was implemented as a commitment of the city government. This legally nonbinding instrument led to participatory procedures, including citizen assemblies and participatory budgeting. The NEOS, which entered the city government after the 2020 elections, propagated citizens’ participation (New Austria and Liberal Forum Party n.d.). The SPOe/NEOS coalition established climate teams and citizens’ juries as well as a deliberative Children and Youth Parliament. Historically, the OeVP supported participatory and direct democratic instruments in Vienna: important participation opportunities were introduced during the two periods of the SPOe/OeVP coalition government (Haas et al. Reference Haas, Moussa-Lipp, Verlič, Ehs and Zandonella2024, 20–39). More recently, the OeVP has focused on opposition rights and control of the government, and citizens’ participation has been deprioritized (Gruener Klub im Rathaus 2024).

The FPOe has used the demand for citizens’ participation as a form of government critique for many decades. However, its program for the 2020 elections did not include any proposals for democratic instruments (Freedom Party of Austria 2020). The new HC party, which was formed by the former FPOe party leader, Heinz-Christian Strache, included a demand for direct democracy in its program without any further explanation, and it did not specifically mention deliberative procedures (Team HC Strache n.d.). The LINKS program included a demand for local citizen assemblies to be open to all residents (LINKS 2020, 17). The Beer Party did not publish a program for the elections, and its various published demands did not mention democratic instruments. Since the elections, however, the party has advocated for participatory rights for young people (Bierpartei n.d.). One of the demands made by SOeZ (Social Austria of the Future 2020) in the elections was for a migrants’ advisory council in the city government. After the elections, SOeZ (Social Austria of the Future n.d.) also demanded a citizens’ assembly in one district. In its program, Volt Austria (2020) demanded citizens’ assemblies and citizen budgets in the Viennese districts.

Regarding voting rights for noncitizens, on the one hand, a clear left/right differentiation is observed; on the other hand, the focus is on the political rights of EU citizens on the side of the pro-EU parties.

The SPOe expressed a desire to introduce voting rights for third-country citizens at the district level in 2002. However, this was rejected by the Constitutional Court (Mokre and Ehs Reference Mokre and Ehs2021, 717). From 2004 to 2015, the Viennese SPOe, together with the Greens, demanded communal voting rights for non-Austrians. In 2019, the SPOe, the Greens, and NEOS demanded voting rights for EU citizens at the city level. However, not long before the elections of 2020, the SPOe mayor rejected voting rights for residents who did not have Austrian citizenship (Gaigg and Winkler-Hermaden Reference Gaigg and Winkler-Hermaden2020). The Greens, conversely, held their position of suffrage for all residents (Die Gruenen Wien n.d.); this demand also was made by LINKS (2020, 15–17) and SOeZ (Social Austria of the Future 2020). The NEOS and Volt Austria parties demanded voting rights for EU citizens at the city level (New Austria and Liberal Forum Party 2020; Volt Austria 2020). In line with their nationalistic programs, OeVP, FPOe, and HC rejected the idea of any political rights for foreigners (Brunnbauer et al. 2020; Freedom Party of Austria 2019; Team HC Strache n.d.) The Beer Party did not mention this topic in its campaign or afterwards. Table 1 presents the positions of these political parties in more detail.

Table 1 Positions of Political Parties

DELIBERATION OF NON-VOTERS AND POLITICAL PARTIES

As Gherghina and Jacquet (Reference Gherghina and Jacquet2023, 496) pointed out, the competitive logic of party systems and the collaborative logic of deliberative democracy contradict one another in principle. This raises the question of why political parties sometimes embrace deliberative procedures. The forms of deliberation addressed in this article can be understood as links between the political system and the citizenry (Dryzek et al. Reference Dryzek, Bächtiger, Chambers, Cohen, Druckman, Felicetti and Warren2019; Gherghina and Jacquet Reference Gherghina and Jacquet2023, 500). As academic research on political parties has shown extensively, the traditional function of political parties to provide a linkage between citizens and the political system has been weakened continuously as political parties distanced themselves from the citizenry and became part of the political system (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995; Sartori Reference Sartori1976). Thus, political parties can expect to attract voters by expressing their willingness to directly include the citizenry in decision making (Caluwaerts and Reuchamps Reference Caluwaerts and Reuchamps2018).

However, the inclusion of residents without suffrage in deliberative practices does not form a direct link between political parties and voters because those being encouraged to participate are not allowed to vote. Nevertheless, from a normative perspective, it seems beneficial to include all people living within a political system in political decision making—and, arguably, all the more so given that deliberative practices deepen democracy and provide civic education. Citizen initiatives and assemblies can influence public opinion and, by impacting the public sphere, these participatory elements also impact the decision making of politicians.

This was the goal of the project, “If No Vote, at Least Voice.” The idea was that the political positions of people without suffrage should be presented to the political parties running in the Viennese elections and also to the Viennese population with voting rights.Footnote 3 In this regard, a mini-public of people without suffrage living in Vienna developed questions that were submitted to all political parties running for election in more than one Viennese district.

All of the parties except the Beer Party answered the questions, irrespective of their positions toward voting rights for foreigners and participatory democracy. This likely was due to the timing and setup of the project because the participating political parties used the process as an additional campaign tool to address people who had voting rights. This result is aligned with previous evidence from other countries—for example, see Mompó, Borge, and Barberà (Reference Mompó, Borge, Barberà and Gherghina2024) for Spain; Pálsdóttir (Reference Pálsdóttir2024) for Iceland; Saintraint and Suiter (Reference Saintraint, Suiter and Gherghina2024) for Ireland; Oross (Reference Oross2024) for Hungary; and Vittori (Reference Vittori2024) for Italy.

The questions and the answers of the political parties were presented to the public in the form of a special issue of the widely used online tool, wahlkabine.at (Wahlkabine 2020). By using this popular tool, users can find out in an amusing way how their own positions correspond to those of political parties. The presentation on wahlkabine.at generated broad public awareness for the project and therefore was an incentive for political parties to answer the questions.

Thus, the project resulted in including the interests and positions of people who do not have suffrage in the agenda-setting during a politically charged period—namely, an electoral campaign. In this way, an incentive was created for political parties to address this agenda. Consequently, the interests of people without suffrage, as well as the reactions of political parties to them, were brought into the public sphere.

Overall, regarding the case of Vienna, even nonbinding participatory forms of democracy can influence the public sphere and political decision makers when they are used in a way that potentially influences elections.

CONCLUSIONS

This article answers the question of whether deliberative practices can compensate for a lack of voting rights by impacting the activities and attitudes of political parties. The study results are in broad alignment with the findings of previous studies (Bedock and Pilet Reference Bedock and Pilet2020; Gherghina and Geissel Reference Gherghina and Geissel2020; Theiss-Morse and Hibbing Reference Theiss-Morse and Hibbing2005; Warren Reference Warren2009). At the same time, voting is the strongest and the most easily accessible political right, directly shaping political representation. Thus, on the one hand, the barrier to participate in deliberative activities is comparatively high whereas, on the other hand, the political influence of these practices frequently is limited. As the history of deliberation in Vienna demonstrates, even those parties that favor more participatory forms of democracy frequently prefer legally nonbinding instruments of participation. Although, in principle, city governments can commit to the legally binding results of deliberations, that commitment has not yet been made in Vienna.

The impact of the project, “If No Vote, at Least Voice,” remained limited. It made public the positions of usually ignored parts of society, as well as the reactions of political parties to these positions. However, strong incentives were not created to improve the quality of democracy in Vienna—by either promoting suffrage for residents without citizenship or developing legally binding forms of participatory democracy. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that more regular practices of publicly informing political parties of the positions of people without suffrage would potentially impact politics similar to how mini-publics are directly used by political parties in election campaigns (Gherghina and Jacquet Reference Gherghina and Jacquet2023, 503).

The systematic inclusion of migrants in deliberative democracy is inherently desirable due to the positive normative value of deliberative practices (Gherghina and Jacquet Reference Gherghina and Jacquet2023, 504). Arguably, this position holds especially true for people without suffrage who are subject to laws enacted by a system in which they are not allowed to vote. Furthermore, in contemporary discourses on radicalization and the development of parallel societies, the civic education of migrants has gained public attention. In this regard, the Viennese example serves as a model for similar attempts to include in politics the ever-growing population without suffrage.

The systematic inclusion of migrants in deliberative democracy is inherently desirable due to the positive normative value of deliberative practices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article is based on the work of the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST), Action CA22149 Research Network for Interdisciplinary Studies of Transhistorical Deliberative Democracy, supported by COST.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.