Introduction

Italian ryegrass [Lolium perenne L. ssp. multiflorum (Lam.) Husnot] (2n = 2x = 14 or 2n = 4x = 28) is among most troublesome weeds in winter and spring cereal grains production in the United States (Van Wychen Reference Van Wychen2023). In wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), L. perenne ssp. multiflorum has been reported to cause a yield loss from 4.2% to 92%, primarily driven by weed density (Yadav et al. Reference Yadav, Purohit, Russell and Maity2024). Liebl and Worshman (Reference Liebl and Worsham1987) reported a 4.2% loss of yield in wheat at a L. perenne ssp. multiflorum density of 10 plants m−2 in North Carolina. Furthermore, Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a) reported a yield loss of 40% at a L. perenne ssp. multiflorum density of 40 plants m−2 in Texas. Similarly, L. perenne ssp. multiflorum has been reported to cause a yield reduction of 61% in wheat in Oregon when present at a L. perenne ssp. multiflorum density of 93 plants m−2 (Appleby et al. Reference Appleby, Olson and Colbert1976).

Herbicides are the most commonly used tool to control L. perenne ssp. multiflorum in wheat and other crops in the United States; however, the increasing cases of herbicide-resistant (HR) L. perenne ssp. multiflorum worldwide threaten this most cost-effective and efficacious mode of management options. Rapid evolution of herbicide resistance has been observed in L. perenne ssp. multiflorum, and in the United States, it has been reported to be resistant to six modes of action that include acetyl coenzyme-A carboxylase (ACCase) inhibitors (WSSA Group 1), acetolactate synthase (ALS) inhibitors (WSSA Group 2), enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phospahate synthase (EPSPS) inhibitors (WSSA Group 9), glutamine synthetase inhibitors (WSSA Group 10), very-long-chain fatty-acid inhibitors (WSSA Group 15), and photosystem I inhibitors (WSSA Group 22) (Heap Reference Heap2025).

Herbicide resistance, whether caused by amino acid substitution at the target site or by metabolism-based mechanisms, can also lead to changes in plant and seed traits, which are sometimes quantified as a fitness cost (Vila-Aiub et al. Reference Vila-Aiub, Neve and Powles2009). Nonetheless, the propensity of a plant species to invade and adapt to changing growing conditions often stems from its wide range of diversity in the adaptive and life-cycle traits. Growing conditions and human interference as a part of crop management practices are reported to impose stress on crops and weeds, leading to changes in vital adaptive traits in plants (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a).

Seed dormancy is an important survival trait, and increased seed dormancy in weed species may help them to survive early-season chemical as well as non-chemical management practices (Darmency et al. Reference Darmency, Colbach and Le Corre2017). It has been suggested that intensive agricultural practices can drive directional selection for specific seed morpho-physiological characteristics such as seed dormancy and sizes (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Rocha, Khalil, Bagavathiannan, Ashworth and Beckie2022, Reference Maity, Paul, Rocha, Bagavathiannan, Beckie and Ashworth2024; Owen et al. 2015). For instance, Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Rocha, Khalil, Bagavathiannan, Ashworth and Beckie2022) concluded that seed dormancy of ripgut brome (Bromus diandrus Roth), wild oat (Avena fatua L.), and hare barley [Hordeum leporinum Link; syn.: Hordeum murinum L. ssp. leporinum (Link) Arcang.] collected from fields under intensive agriculture was higher compared with their counterparts with no history of herbicide exposure. Likewise, seed sizes of H. leporinum and B. diandrus were greater compared with their ruderal counterparts. Seed traits, such as seed weight, may contribute to enhanced seed dormancy by increasing the potential for germination from greater soil depths, increasing the likelihood of exposure to late-season postemergence herbicides and, consequently, the potential of resistance development (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a). Furthermore, integrating a trait-based approach to understanding herbicide resistance may enhance the development of more effective risk assessment tools (Hulme and Liu Reference Hulme and Liu2021). For instance, Hulme and Liu (Reference Hulme and Liu2021) found that HR weed species are more likely to be wind-pollinated and outcrossing in nature with unisexual flowers, larger chromosome numbers, and greater seed size compared with herbicide-susceptible weed species.

Correlation studies among seed morpho-physiological traits may provide a better understanding of the process of trait-assisted herbicide-resistance evolution. Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a) reported a correlation between the degree of herbicide resistance in Texas L. perenne ssp. multiflorum populations and adaptive traits such as seed dormancy and germination. This correlation was primarily attributed to the intense selection pressure from recurrent agronomic practices, including the repeated use of herbicides with the same modes of action, which may have been selected for specific seed traits (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Rocha, Khalil, Bagavathiannan, Ashworth and Beckie2022). Understanding these traits could be crucial for understanding seed dormancy in Lolium spp. (Owen et al. 2011). This also highlights the importance of studying the concurrent evolution of herbicide resistance and seed germination traits to better strategize the timing and specifics of herbicide programs for effective weed control.

HR L. perenne ssp. multiflorum has been recently reported in Alabama (Yadav et al. Reference Yadav, Russell, Ganie, Patel, Price and Maity2025); however, information on diversity in seed morpho-physiological traits and its association with herbicide resistance in L. perenne ssp. multiflorum is limited. Hence, the objective of this study was to assess seed morpho-physiological trait diversity and to explore its potential association with herbicide resistance in Alabama L. perenne ssp. multiflorum populations.

Materials and Methods

Lolium perenne ssp. multiflorum populations were collected from late spring to early summer of 2023 through a semi-stratified survey designed to target wheat, soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.], peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.), and corn (Zea mays L.) fields, as well as field borders across Alabama. Some of the plants were survivors of in-season herbicide applications, identified based on the herbicide failure reports from farmers. Others were assumed to be either potential survivors of season-long herbicide applications or late-emerged plants. A total of 20 to 25 seed heads from plants growing within an area of 10 to 15 m2 were collected and combined to form each population. A minimum distance of 3.2 to 4.8 km between collection sites was maintained based on the previous weed survey to ensure spatial distinction among the populations (Bagavathiannan and Norsworthy Reference Bagavathiannan and Norsworthy2016).

A total of 65 L. perenne ssp. multiflorum populations were collected late in the summer, by which point most populations had already completed their life cycles. Surveys were timed to address the fact that populations in southern Alabama matured a few days earlier than those in northern Alabama. As perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) is also commonly found in southern states, all the Lolium spp. populations collected were examined and confirmed to be L. perenne ssp. multiflorum following the method of Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Singh, Martins, Ferreira, Smith and Bagavathiannan2021b) and Bararpour et al. (Reference Bararpour, Norsworthy, Burgos, Korres and Gbur2017). The seed heads were hand-threshed immediately after collection, and the seeds were stored at room temperature (20 to 22 C) until they were used for further experiments.

Seed Morpho-physiological Studies

Studies were conducted in the Weed Bionomics Laboratory at Auburn University, Auburn, AL. All 65 populations were included for evaluating the seed morpho-physiological traits. The seed traits analyzed included 100-seed weight, awn length, seed length, seed dormancy and germination, and seedling root and shoot length. For the 100-seed weight, four random samples of 100 seeds were taken from each population, and their weights were recorded. Awn and seed lengths were measured using 10 randomly selected seeds from each population, with measurements recorded on ruled graph paper in centimeters. For seed dormancy evaluation, germination tests were conducted in a completely randomized design with four replications, each consisting of 50 seeds. The seeds were placed in petri dishes containing double filter paper (Zenpore, Hong Kong, NT) and incubated in a growth chamber (E-36L2, Percival Scientific, Perry, IA, USA) set to a diurnal light cycle of 12 h and a temperature of 21 C. This experiment was repeated every 3 mo up to 9 mo after seed collection. Germination was recorded every 2 d for the first 10 d, followed by additional recordings on the 14th and 21st days. At the end of each germination run, seeds were assessed for viability using the tap method; seeds found to be turgid and alive were dissected and subjected to the tetrazolium test at a 0.1% concentration, and the red-colored seeds were considered viable (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a).

Herbicide Screening

Due to limited seed quantity and high seed dormancy, only 44 populations from Escambia, Baldwin, Lee, Henry, Dallas, Walker, Franklin, Cullman, Limestone Bibb, and Jackson counties were included in the herbicide screening study. Herbicide screenings were conducted in the spring of 2024 at the Plant Science Research Center Greenhouse Complex (32.58°N, 85.48°W) located at Auburn University, Auburn, AL, as described in Yadav et al., Reference Yadav, Russell, Ganie, Patel, Price and Maity2025, Weed Science, in press). Out of 44 populations, one population (AL-64) from northern Alabama without any known history of herbicide exposure was tested at field recommended rates of all herbicides used in the study and, after analysis of the results, it was declared the susceptible standard. The herbicide treatments included: (1) the ACCase inhibitors fluazifop (Fusilade® DX, Syngenta, Greensboro, NC, USA) and clethodim (Section® Three, Winfield Solutions, St Paul, MN, USA); (2) the ALS inhibitor pyroxsulam (PowerFlex® HL Herbicide, Corteva Agriscience, Indianapolis, IN, USA); and (3) the EPSPS inhibitor glyphosate (Roundup PowerMAX® 3 Herbicide, Bayer CropScience, St Louis, MO, USA). All herbicides were applied at their recommended label rates: clethodim at 283 g ai ha−1; fluazifop at 213 g ai ha−1; pyroxsulam at 233 g ai ha−1; and glyphosate at 1,133 g ae ha−1. Herbicides were applied when the plants were at the 3- to 4-leaf seedling stage (∼3- to 4-wk old), using a two-nozzle sprayer powered by a CO2 cylinder and equipped with flat-fan nozzles (TeeJet® XR110015, TeeJet Technologies, Wheaton, IL, USA) calibrated to deliver a spray volume of 140 L ha−1 at 289 kPa at a speed of 4.8 km h−1. Injury ratings (based on a scale of 0% to 100%; 0% means no injury, and 100% means completely dead) and plant mortality were recorded at 3 wk after treatment to estimate the level of resistance. Non-treated controls were included for initial screening.

Data Analysis

Seed dormancy was calculated using the following equation (Equation 1):

where d represents dormancy, x is the total number of seeds, y is the final germination at the end of the 21-d period, and z represents the number of dead seeds. Then the k-means clustering method using the clusterR package (R v. 4.3.0; R Core Team 2025) was applied to classify the dormancy percentages of freshly harvested seeds into three clusters: low dormancy (LD) (<15%), medium dormancy (MD) (15% to 30%), and high dormancy (HD) (>30%), explaining 85.10% of the variation. Box plots were used to illustrate interpopulation diversity in seed traits such as seed length, 100-seed weight, awn length, seed dormancy, and seedling length.

The time to reach 50% seed germination (TG50) across populations was estimated by fitting a three-parameter sigmoidal model (Equation 2) to cumulative seed germination data collected over 21 d. This model, constructed using the drc package (Ritz et al. Reference Ritz, Baty, Streibig and Gerhard2015) in R v. 4.3.0 (R Core Team 2025), is defined as follows:

where y represents the cumulative germination (%) on the xth day, a is the maximum germination (%), x 0 is the number of days to reach 50% germination, and b represents the slope at x 0.

Data on seed dormancy changes and release rates at 3, 6, and 9 mo after harvest for each dormancy group (Table 1) were analyzed using SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The seed dormancy release rate was calculated as follows (Equation 3):

where y is the seed dormancy release rate (%) after the nth month, x 0 is the initial dormancy (%) of freshly harvested seed, and x n is the seed dormancy (%) at the nth month.

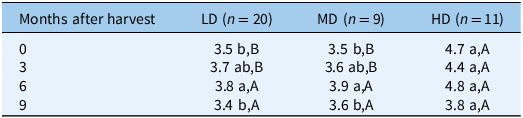

Table 1. Time required for 50% seed germination (TG50) among three dormancy groups of Lolium perenne ssp. multiflorum populations from Alabama at 0, 3, 6, and 9 mo after harvest a .

a The k-means procedure was applied to the dormancy percentages of freshly harvested seeds, resulting in the classification of three clusters: LD, low dormancy (<15%); MD, medium dormancy (15%–30%); and HD, high dormancy (>30%). The clustering explained a total of 85.10% of the variation. Significant differences (P < 0.05) among dormancy groups and observation timings are indicated by uppercase letters and lowercase letters, respectively. Unit for TG50 (time required to reach 50% germination) is days.

Results and Discussion

Interpopulation Diversity in Seed Morphological Traits

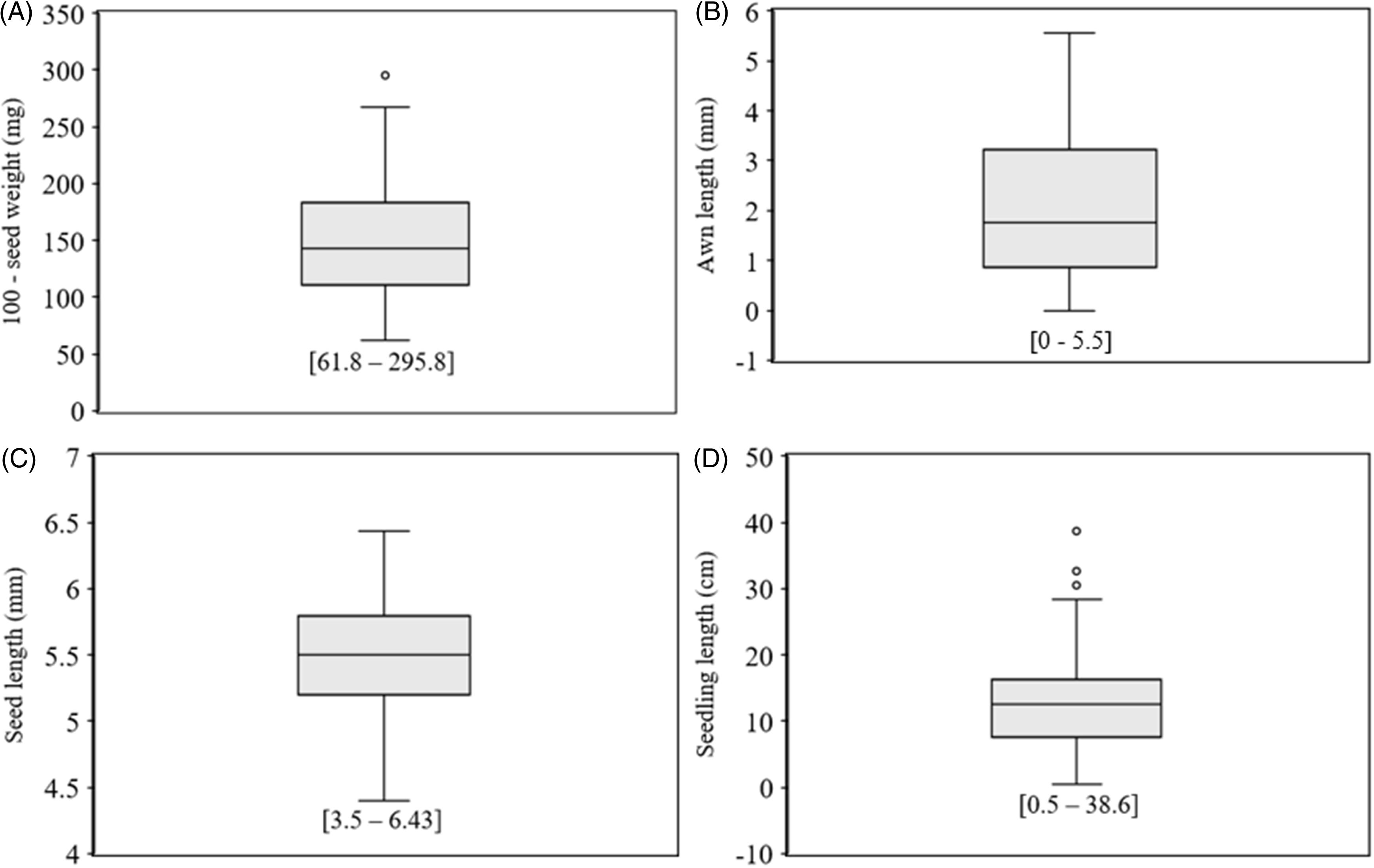

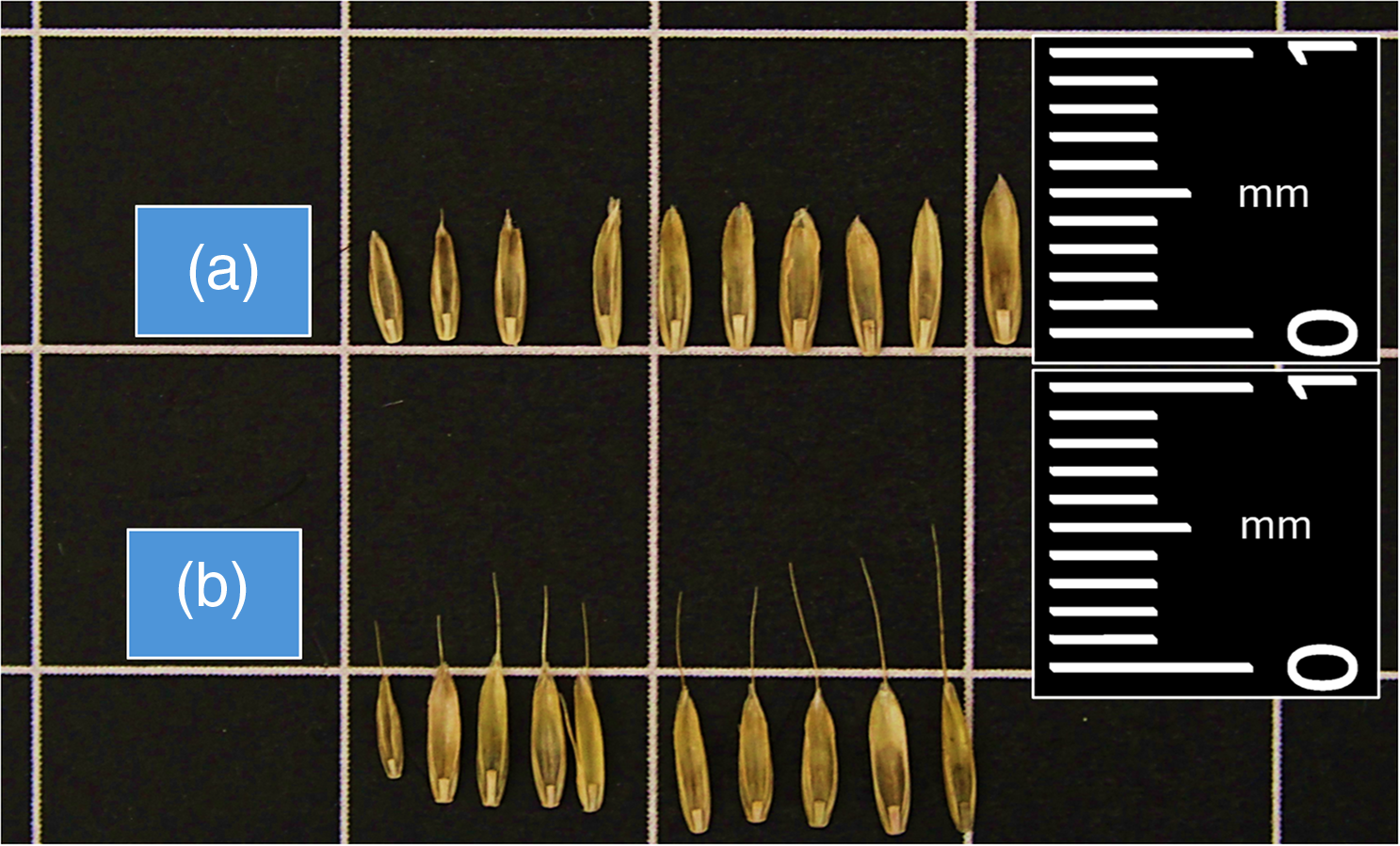

Out of the 65 populations used in the study, 31 were collected from southern Alabama (Escambia, Baldwin, and Henry) counties, 3 from central Alabama (Dallas and Lee) counties, and 31 from northern Alabama (Dekalb, Walker, Lawrence, Franklin, Cullman, Limestone, Bibb, Morgan, and Jackson) counties. Substantial interpopulation diversity in both seed and seedling traits was observed (Figures 1 and 2), similar to the findings reported in L. perenne ssp. multiflorum populations by Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Singh, Martins, Ferreira, Smith and Bagavathiannan2021b) in Texas and Bararpour et al. (Reference Bararpour, Norsworthy, Burgos, Korres and Gbur2017) in Arkansas. The 100-seed weight ranged from 61.8 mg to 295.8 mg across populations (Figure 1A), while seed length varied significantly, from 3.5 mm to 6.43 mm (Figure 1C). Awn length also displayed marked variability; some populations had no awns, while others reached lengths of up to 7 mm (Figure 1B). Likewise, seedling length, which was measured at the end of the germination test as an indicator of seed vigor, ranged considerably, from 0.5 cm to 38.6 cm (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Box plots showing inter population diversity for (A) 100-seed weight, (B) awn length, (C) seed length, and (D) seedling length (total of root and shoot length at 21 d after seed germination) across (A–C) 65 Lolium perenne ssp. multiflorum populations and (D) 56 populations (9 populations had no germination) evaluated in the study (all from Alabama). The values shown in square brackets for each variable indicate the minimum and maximum population means observed in the study.

Figure 2. An example of diversity for (A) seed size and (B) awn length across the Lolium perenne ssp. multiflorum populations from Alabama evaluated in the study.

Seed polymorphism is a common phenomenon observed in many plant species, often associated with variations in dispersal ability, germination behavior, and dormancy-breaking requirements, all of which can enhance a species’ adaptive potential (Venable and Levin Reference Venable and Levin1985). These variations in seed traits among the populations can be partially explained by environmental factors, local adaptation to applied selection pressure by the biotic as well as abiotic factors, and their genetic makeup (Bu et al. Reference Bu, Chen, Xu, Liu, Jia and Du2007; Li et al. Reference Li, Tan, Li, Yuan, Du, Ma and Wang2015; Linkies et al. Reference Linkies, Graeber, Knight and Leubner-Metzger2010). Alabama spans from 30°N to 35°N latitude, and its weather varies accordingly in both temperature and rainfall. Counties near the Gulf of America (formerly Gulf of Mexico) tend to experience warmer temperatures (ranging from 4 C to 32 C) and receive more annual rainfall (1,673 mm) than those in the northern part of the state, where temperatures range from −1.5 C to 30 C and annual rainfall averages 1,447 mm (Chaney Reference Chaney2023). Daylength is longer at higher latitudes, and the transition from longer nights to longer days is faster, which can induce earlier flowering in L. perenne ssp. multiflorum, a long-day plant. This allows the Lolium spp. in northern counties more time to complete its life cycle and seed development compared with Lolium spp. in southern counties, which in turn might have influenced the diversity differences in seed morpho-physiological traits.

In the current study, populations from northern Alabama were more likely to fall into the upper quartile for both 100-seed weight (75%) and seedling length (71%). The temperature and rainfall pattern to which plants are exposed during seed maturation also play an important role in dormancy levels, seed weight, and numbers (Fenner Reference Fenner1991). Seeds produced from plants under warm temperatures weighed less and had less dormancy compared with plants grown in cooler temperatures (Baskin and Baskin Reference Baskin and Baskin1998; Fenner Reference Fenner1991), which supports our results. The local habitats where these populations were collected can be categorized into row-crop fields (60%), field borders (37%), and pasture (2%) situations. Also cropping systems from which the populations were collected included cotton, corn, soybean, peanut, and wheat. The presence of these populations across diverse agroecosystems likely increased the probability of exposure of these populations to a wide range of selection pressures in terms of management factors, including herbicides, which could lead to selection for diverse traits (Owen et al. 2011). Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Rocha, Khalil, Bagavathiannan, Ashworth and Beckie2022, Reference Maity, Paul, Rocha, Bagavathiannan, Beckie and Ashworth2024) reported a significant difference in seed sizes and dormancy levels among weed populations collected from different agricultural systems in Western Australia.

Lolium perenne ssp. multiflorum diploid as well as tetraploid cultivars are used in forage production in the U.S. Southeast. As L. perenne ssp. multiflorum is a self-incompatible, outcrossing species, the populations can hybridize and increase the chances of genetic diversity as well as diversity in ploidy levels in de-domesticated or feral populations. In the current study, populations collected may have both ploidy levels, which can also affect seed morphological traits; however, their ploidy levels were not examined in this study. Venuto et al. (Reference Venuto, Redfearn, Pitman and Alison2002) reported that seed weights for a single seed varied from 2.4 mg in diploid cultivars to 4.8 mg in tetraploid cultivars in L. perenne ssp. multiflorum populations from the U.S. Southeast. These variations in seed sizes, awn length, seed weight, and seedling length could be interpreted as functions of local adaptations that in various ways help this species to thrive. For instance, greater seed weights may help in persistence and germination from greater soil depths (Baskin and Baskin Reference Baskin and Baskin1998); likewise, greater seed sizes may help in the invasion of a weed into new habitats as well as improving seedling emergence (Buckley et al. Reference Buckley, Downey, Fowler, Hill, Memmot, Norambuena and Rees2003).

In Alabama, soil erosion is a problem, and to alleviate that, farmers practice conservation or no tillage as recommended by local agencies (Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Alabama; U.S. Department of Agriculture–Natural Resources Conservation Service). In such fields, smaller seed sizes may increase the chances of germination with minimum soil incorporation. Also, greater awn length observed in several L. perenne ssp. multiflorum populations may tend to increase dispersal distance, which is an important factor for ecological dominance that is positively correlated with germination and favors survival during fire events, as indicated by Ntakirutimana et al. (Reference Ntakirutimana, Xiao, Xie, Zhang, Zhang and Wang2019). The greater seedling length, which is an indicator of vigor, may help in pushing through biomass residue and soil crust, providing better chances of seedling recruitment in the specific L. perenne ssp. multiflorum populations (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a; Marcos Filho Reference Marcos Filho2015; Meneguzzo et al. Reference Meneguzzo, Meneghello, Nadal, Xavier, Dellagostin, Carvalho, Gonçalves, Lautenchleger and Lângaro2021; Yaklich and Kulik Reference Yaklich and Kulik1979).

Interpopulation Diversity for Seed Physiological Traits

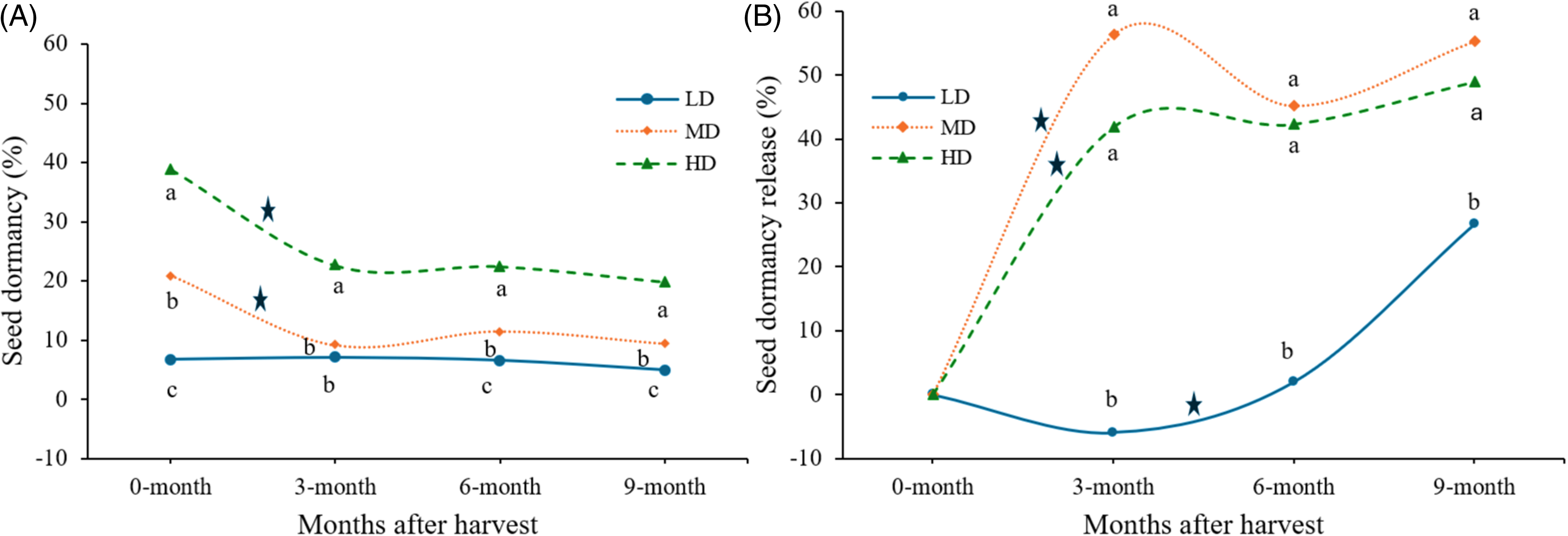

Freshly harvested seeds exhibited a wide range of dormancy levels, ranging from 0.7% to 60% with a mean of 19% across the populations, which were grouped into three categories (Figure 3). Seed dormancy declined rapidly within 3 mo after harvest with a range of 0.7% to 37% and a mean value of 12%. At 6 mo, several populations released dormancy, whereas some induced secondary dormancy. At 9 mo, overall seed dormancy was at its lowest with a mean of 10%, ranging from 0.7% to 14%. The lowest seed dormancy observed at 9 mo in the current study aligns with the findings of Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a) and Stanisavljevic et al. (Reference Stanisavljevic, Djokic, Milenkovic, Ðukanovic, Stevovic and Simic2011), who observed the same trends in Texas and Serbia, respectively. Dormancy release patterns varied significantly (P < 0.001) among the three dormancy groups—LD, MD, and HD (Figure 3A). The HD group consistently exhibited greater seed dormancy across all time points, followed by the MD group. Significant (P < 0.001) dormancy release occurred between 0 and 3 mo in the MD and HD groups, while the LD group showed only minor changes over this period (Figure 3B). The rate of dormancy release was significantly (P < 0.001) lower in the LD group compared with the MD and HD groups at all time points, which aligns with the results of Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a) and Goggin et al. (Reference Goggin, Emery, Powles and Steadman2010).

Figure 3. (A) Seed dormancy change in Lolium perenne ssp. multiflorum populations from Alabama at 0, 3, 6, and 9 mo after harvest, compared among the three dormancy groups developed based on the dormancy level of the freshly harvested seeds using k-means clustering procedures: LD, group of populations with low initial dormancy (<15% dormancy); MD, moderate initial dormancy (15%–30% dormancy); HD, high initial dormancy (>30% dormancy). (B) Seed dormancy release rate over 9 mo among the three dormancy groups (LD, MD, and HD). Here, dormancy at 0 mo for each group was used as the base dormancy level to calculate subsequent dormancy release patterns. In both panels, letters accompanied by the data points indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) among the three dormancy groups within each observation timing (0, 3, 6, or 9 mo). Asterisks (*) indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05) between two consecutive observation timings for a given dormancy group.

The phenomenon of cyclic dormancy induction observed in HD and MD groups at 6 mo and marginally in LD group at 3 mo is commonly observed in other plant species (Baskin and Baskin Reference Baskin and Baskin1985). Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a) reported a similar trend in L. perenne ssp. multiflorum populations collected in Texas. Ecologically this trait provides a survival advantage by not allowing germination in short spells of favorable environments in the off season, when the plant may germinate but chances of its successful life cycle and seed production will be much lower (Hilhorst Reference Hilhorst1998). Overall variations in seed dormancy in this study could be partially explained by the variations in environmental and crop settings from north to south Alabama. In the LD cluster, 85% of the populations were from southern counties of Alabama, whereas in the HD cluster, 55% of the populations were from northern Alabama. Northern Alabama has slightly lower average temperature and rainfall compared with southern counties throughout the year, which may lead to seed production with higher seed dormancy (Baskin and Baskin Reference Baskin and Baskin1998; Fenner Reference Fenner1991). Additionally, cropping history and herbicide programs used may influence seed dormancy levels. For instance, Steadman et al. (Reference Steadman, Eaton, Plummer, Ferris and Powles2006) observed in Australia that after exposure to glyphosate, the proportion of seeds exhibiting dormancy was reduced in rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaudin) populations. Higher seed dormancy could be a part of adaptation to survival from preemergence and early-season herbicide applications, as reports indicate a correlation between herbicide resistance and higher seed dormancy (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Rocha, Khalil, Bagavathiannan, Ashworth and Beckie2022; Owen et al. Reference Owen, Michael, Renton, Steadman and Powles2010, Reference Owen, Goggin and Powles2014).

The time required for 50% seed germination (TG50) also differed significantly (P < 0.001) among dormancy groups at 0 and 3 mo (Table 1). At 0 mo, the HD group had a significantly greater TG50 (4.7 d) compared with the LD (3.5 d) and MD (3.5 d) groups, indicating slower germination in the HD group. By 6 and 9 mo, no significant differences in TG50 were observed between the dormancy groups. The slowest germination speed was observed at 6 mo in all dormancy groups, which can be partially explained by the cyclic dormancy induction. Also, the maximum speed of germination at 9 mo aligns with the results of Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a) and the seed dormancy release pattern in the current study. Slow germination could provide a wide window of emergence, which could be an ecological advantage to L. perenne ssp. multiflorum in the scenarios where burndown application is performed before planting using herbicides with low residual activity. Moreover, temporally scattered germination could also help in the distribution of available resources (Baskin and Baskin Reference Baskin and Baskin2014). In the current study, a statistically significant maximum difference (1.2 d) was observed in freshly harvested seeds between LD and HD groups; however, the agronomic significance of this difference needs to be validated.

Correlation Analysis between Herbicide Resistance and Seed Traits

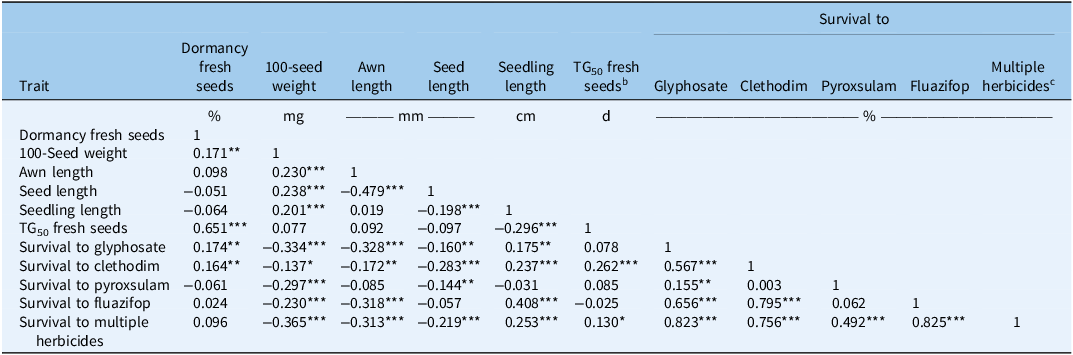

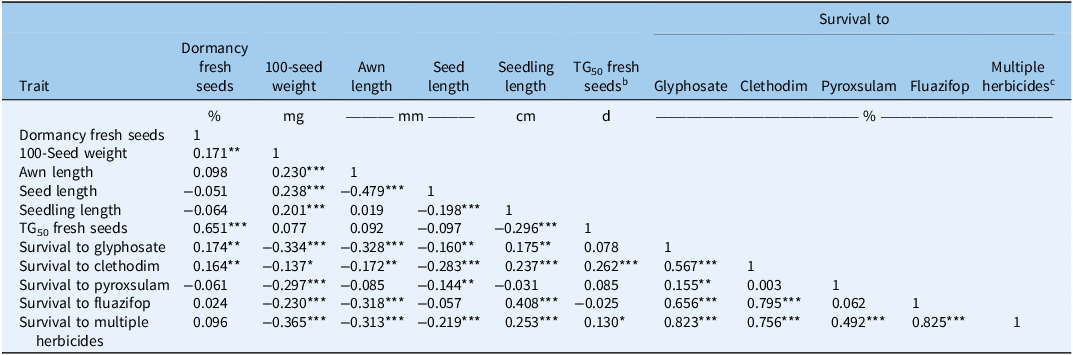

Correlation among Various Seed Morpho-physiological Traits

There were significant associations among various seed traits that have been examined in this study (Table 2). A significant positive correlation (r = 0.17, P < 0.01) was observed between 100-seed weight and freshly harvested seed dormancy. The TG50 also had a significant positive correlation (r = 0.65, P < 0.001) with freshly harvested seed dormancy. Furthermore, 100-seed weight had significant positive correlations with awn length (r = 0.23, P < 0.001), seed length (r = 0.23, P < 0.001), and seedling length (r = 0.20, P < 0.001). Awn length showed a significant negative correlation with seed length (r = −0.47, P < 0.001). Seedling length exhibited a significant negative correlation (r = −0.29, P < 0.001) with TG50, indicating that vigorous seeds have faster germination. Positive association between seed weight and dormancy was previously attributed to increased seed coat thickness in shortfruit stork’s-bill [Erodium brachycarpum (Godr.) Thell.] in California (Venable and Levin Reference Venable and Levin1985). The positive correlation between seedling length and 100-seed weight aligns with the results of Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a) and underscores the importance of high seed biomass in producing healthy and robust seedlings (Hendrix et al. Reference Hendrix, Nielsen, Nielsen and Schutt1991; Luo et al. Reference Luo, Zhang, Yan, Zhang, Wei, Yang, Shen, Zhang and Cheng2023). Positive correlation between TG50 and seed dormancy was expected and implies that dormancy helps in temporally staggered germination, ensuring survival of at least a cohort of emerging seedlings.

Table 2. Pearson correlation analysis between the different seed morpho-physiological traits and survival (%) to herbicides among the different Lolium perenne ssp. multiflorum populations (34) from Alabama investigated in the study a .

a Significance levels: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

b Time taken in days to reach 50% seed germination over 21 d, measured on freshly harvested seed.

c Average survival rate (%) across all four herbicides (glyphosate, fluazifop-butyl, clethodim, and pyroxsulam) evaluated in the study.

Correlation between Seed Morpho-physiological Traits and Herbicide Resistance

Strong association in both positive and negative directions has been observed between seed morpho-physiological traits and survivors to herbicides used in the study (Table 2). The 100-seed weight had a significant negative correlation with survival percentages to glyphosate (r = −0.33, P < 0.001), clethodim (r = −0.13, P < 0.02), pyroxsulam (r = −0.29, P < 0.001), and fluazifop (r = −0.23, P < 0.001), as well as with average survival across all herbicides (r = −0.36, P < 0.001) tested. Likewise, the awn length had a significant negative correlation with survival percentage to glyphosate (r = −0.32, P < 0.001), clethodim (r = −0.17, P < 0.004), fluazifop (r = −0.31, P < 0.001), and multiple herbicides (r = −0.31, P < 0.001). The seedling length had a positive correlation with survival percentages to clethodim (r = 0.23, P < 0.001), glyphosate (r = 0.17, P < 0.01), and fluazifop (r = 0.4, P < 0.0001) and with the average survival rate (r = 0.25, P < 0.001) across all herbicides. Additionally, dormancy in freshly harvested seed showed a significant positive correlation with survival percentages for both clethodim (r = 0.16, P < 0.006) and glyphosate (r = 0.17, P < 0.004). The TG50 had a significant positive correlation with clethodim survivors (r = 0.26, P < 0.001) and with the average survival rate (r = 0.13, P < 0.03) across all four herbicides.

The negative correlation between 100-seed weight and survival to both individual and multiple herbicides, along with the negative correlation between awn length and survival to individual (except pyroxsulam) and multiple herbicides, as well as seed length and survival to individual (except fluazifop) and multiple herbicides, suggests that there may be a fitness cost associated with herbicide resistance in these populations. In arable weeds, fitness generally refers to the ability to survive and reproduce (Menchari et al. Reference Menchari, Chauvel, Darmency and Délye2008). Given the importance of 100-seed weight, awn length, and seed length in survival, persistence, and reproduction, these traits can be considered key indicators of weed fitness. Ferreira et al. (Reference Ferreira, Santos, Silva, Oliveira and Vargas2006) reported a 40% reduction in vegetative biomass and a 44% reduction in reproductive biomass yield in glyphosate-resistant (GR) L. perenne ssp. multiflorum compared with susceptible plants. Similarly, Yanniccari et al. (Reference Yanniccari, Vila-Aiub, Istilart, Acciaresi and Castro2016) observed reduced fitness in GR perennial ryegrass from Argentina, including decline in seed production, seed weight, shoot biomass, height, and leaf blade area, compared with susceptible plants from the same population.

Menchari et al. (Reference Menchari, Chauvel, Darmency and Délye2008) reported reduced biomass and height in ACCase-resistant biotypes of blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides Huds.) compared with susceptible ones, with the resistance attributed to a target-site mutation (D2078G) in the ACCase gene. This same mutation was also observed in the current study in the ACCase-resistant population (AL-65) (Yadav et al., Reference Yadav, Russell, Ganie, Patel, Price and Maity2025, Weed Science, in press). Similarly, Anthimidou et al. (Reference Anthimidou, Ntoanidou, Madesis and Eleftherohorinos2020) observed reduced vigor and competitive ability in L. rigidum populations with multiple resistance to ALS- and ACCase-inhibiting herbicides compared with susceptible populations in Greece. However, these fitness costs are not consistent and can vary depending on specific herbicide-resistance mutations, the dominance of the fitness cost, the genetic background of the population, and environmental conditions (Vila-Aiub Reference Vila-Aiub2019).

Acquisition of herbicide resistance may not necessarily reduce seed vigor, as observed in L. rigidum biotypes by Holt et al. (Reference Holt, Powles and Holtum1993). The positive correlation between dormancy in freshly harvested seed and survival rates to clethodim and glyphosate aligns with the findings of Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Singh, Jessup and Bagavathiannan2021a), who also reported a positive correlation between survival to pinoxaden and multiple herbicide resistance. Similarly, Darmency et al. (Reference Darmency, Colbach and Le Corre2017) suggested that herbicide resistance and delayed germination may co-occur in populations resistant to ACCase inhibitors, which aligns with the results of the current study.

Herbicide applications may lead to directional selection for traits beyond herbicide resistance (Owen et al. Reference Owen, Michael, Renton, Steadman and Powles2010). This could also exert selection pressure for phenological adaptations, such as seed dormancy (Gundel et al. Reference Gundel, Martinez-Ghersa and Ghersa2008). However, Owen et al. (Reference Owen, Goggin and Powles2014) confirmed that dormancy and herbicide resistance are not directly linked in a cause-and-effect manner. Instead, high-intensity cultivation applies greater selection pressure on seed dormancy alongside resistance, as late-emerging, highly dormant plants often escape early-season herbicide applications and tillage, becoming exposed only to late-season postemergence treatments. Maity et al. (Reference Maity, Rocha, Khalil, Bagavathiannan, Ashworth and Beckie2022), Yadav et al. (Reference Yadav, Russell, Ganie, Patel, Price and Maity2025) confirmed these trends in populations of rigput brome, A. fatua, and H. leporinum, where populations under intensive management regime for the past 5 yr exhibited higher dormancy compared with their ruderal counterparts in Western Australia and exhibited greater resilience to dormancy-breaking treatments.

Overall, a significant seed morpho-physiological diversity was observed in L. perenne ssp. multiflorum populations from Alabama, which likely helps these populations to tolerate various biotic and abiotic stresses, including agricultural management practices. It also indicated that overreliance on chemical weed control and intensive cropping practices may lead to coexistence of herbicide resistance and altered adaptive traits in weeds such as L. perenne ssp. multiflorum. Hence, adjustments in herbicide application timings and integration of other methods such as harvest weed seed control and cover crops along with rotation of herbicide chemistries would prove valuable for management of L. perenne ssp. multiflorum in Alabama cropping systems. Additionally given the diversity and potential to evolve resistance against various herbicide modes of action in this species, L. perenne ssp. multiflorum may be avoided to use as a cover crop. The positive correlation found between seed traits (dormancy and speed of germination) and herbicide resistance (glyphosate and clethodim) offers insights for devising informed management practices for growers. Although this study did not explore the cause of this correlation, it could be of value to explore this relation in future.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Cade Grace for helping in the collection of L. perenne ssp. multiflorum populations from northern Alabama and to all the members of Auburn Weed Bionomics Lab for their help with the study.

Funding statement

The start-up funds provided to the corresponding author by Auburn University are greatfully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.