Introduction

In 2009, a gem dealer, a resource analyst, and a geologist set out to Afghanistan to conduct a geophysical survey of emerald deposits in the mountainous terrain north of Kabul. This area, the Panjshir Valley, is located in the Hindu Kush Mountain Ranges of north-central Afghanistan in a geologic setting propitious for emerald formation. Funded by a USAID partnership with the firm Development Alternatives Inc. (DAI), the team conducted geological surveys to map Afghanistan’s emerald deposits. Using GPS technology, they captured over 150 square miles of emerald-bearing areas. In their report, they noted that Afghan miners had already worked seven-tenths of these deposits through artisanal shafts, tunnels, trenches, and open pits. The DAI team suggested that mapping Afghanistan’s gemstones could “formalize” such small-scale mining—an economic lifeline for many locals. They argued that the informal and makeshift nature of existing operations excluded Afghans from more substantial profits.Footnote 1 Further technological upgrades and large-scale extraction, they claimed, could tap supposedly “untapped” resources to generate state revenue and jobs.

I first met WahabFootnote 2 nearly a decade later, in November 2018, while researching the gemstone trade that connects Pakistan and Afghanistan. His name had come up repeatedly in conversations with dealers of precious stones I met in Pakistan, Thailand, and Hong Kong. In his early sixties, Wahab became the mine-holderFootnote 3 of an emerald mine in his village in Panjshir Valley. Although our first meeting was on a mining site along the steep, tawny slopes of the Khenj district in Panjshir, he asserted that we had met ten years earlier in the gem district of Hong Kong. I was doubtful, since I began my research in 2016. Wahab insisted, however, that I resembled a woman who bought large quantities of lapis lazuli—an ultra-marine gemstone long associated with Afghanistan—for resale in China.Footnote 4 Lapis ornaments—balls, beads, pyramids, and dragon figurines—feature prominently in major jewelry manufacturing and wholesale centers like Guangzhou’s Liwan Plaza, Langang Int’l, Daluo Market, and Hong Kong’s Hung Hom, some of which Wahab once frequented as an exporter.

While Wahab may have mistaken me for a Hong Kong buyer, he was not wrong to point out the centrality of Afghan gems in global trade circuits. These circuits have shifted from Western Europe and the United States to East Asia in recent decades. Hong Kong hosts one of Asia’s largest gem and jewelry fairs. In China, with rising disposable income, purchasing gemstones was second only to real estate and automobiles as an investment as recently as ten years ago (Hsu et al. Reference Hsu2014). In contrast to other gem manufacturing areas, however, Afghanistan is often cordoned off from the global gem and jewelry industry.Footnote 5 This stands in contrast to a place like Jaipur, India. The Jaipuri gem trade, once driven by local consumption and royal patronage, transformed after World War II (Babb Reference Babb2013). The discovery of emerald mines in Brazil in the 1970s led to Jaipur becoming a major center for emerald cutting, with its focus shifting from local markets to international ones. This global orientation contrasts with the situation in Afghanistan, which appears disconnected from the global gem and jewelry industry after decades of war. However, this apparent isolation belies Afghanistan’s historical connections to the acquisition and trade of precious commodities.

In this paper, I bring together these two stories—of professional geologists and traders-cum-mine-holders like Wahab—to explore the connection between a two-century-long history of geological exploration and the present-day characterization of Afghanistan as a mineral-rich “El Dorado.”Footnote 6 Doing so requires placing this relationship within the context of colonial, imperial, and neo-imperial politics. Using an uncommon resource—gemstones—to explore social meanings that both development analysts and Afghan industry players attach to mineral mapping and extraction, I show how geological exploration maps amplified industry hype in the 2000s. Sensationalist media reports of mineral discoveries reflect layers of geological exploration that took place all over Afghanistan over a tumultuous century. These discoveries were also entangled, through the gem trade, in international commercial and material culture networks and across Asia.

The idea of the “frontier” has been central to scholarly understandings of Afghanistan and northwest Pakistan and has shaped much of the scholarly discourse on the region’s history and geopolitical significance. Recently, historians have moved beyond simplistic notions of Afghanistan as a mere buffer state to explore its complex global linkages. Hopkins recasts the frontier as a conceptual frame shaped by various manifestations of state power and political authority. He shows how “frontier governmentality” allowed colonial authorities to manage these spaces through indirect rule, sovereign pluralism, and economic dependencies, while maintaining populations as “objects of state action without being subjects of its justice” (Reference Hopkins2020: 20). This analysis dovetails with Hanifi’s (Reference Hanifi2011) conceptualization of Afghanistan as an artifact of colonial political economy and global capital flows, and complements Crews’ (Reference Crews2015) work on Afghanistan’s commodity export history. Alongside Leake’s (Reference Leake2017) regional history, this scholarship collectively speaks to Afghanistan’s ethnicized frontier status in relation to British colonialism and responds to what Saraf (Reference Saraf2020) identifies as a methodological imperative: to destabilize conventional notions of frontiers as limits of settlement or spaces of statelessness and instead attend to the diverse cultural and political institutions that produce distinctive ideas of sovereignty, mobility, commerce, and community. The colonial construction of Afghanistan as the frontier has also engendered the modern trope of the “failed state” (Manchanda Reference Manchanda2020), showing how entrenched colonial imaginaries continue to shape geopolitical realities and scholarly discourse.

Scholars have begun to explore Afghanistan’s global entanglements through the lens of human mobility, although these studies do not extend to the “itinerant territorialities” that increasingly characterize the study of frontier spaces in African contexts (Mbembe Reference Mbembe2000: 263). Representative approaches include Green’s (Reference Green2011) study of early twentieth-century Indo-Afghan interactions through Muslim modernist networks, and Monsutti’s (Reference Monsutti2004) ethnography of Hazara coal miners as they worked to establish trade and remittance networks from Central Asia to the Gulf. Massoumi (Reference Massoumi, Leake and Guyot-Réchard2023) adds a crucial technological dimension, showing how radio created new channels for transnational connection. These mobilities, as Marsden (Reference Marsden2016; Reference Marsden2017) argues, were reorientated during the Cold War, as traders adopted new modes of doing business and stretched their networks across emerging commercial nodes from Kiev in the former Soviet Union to Yiwu in China. Collectively, these scholarly perspectives on mobility and trade provide a nuanced understanding of Afghanistan’s multifaceted engagement with the world, revealing a place that is “engaged and connected to a wider world” (Crew Reference Crews2015: 2) of people, ideas, and resources.

While much has been done to position Afghanistan as a political, cultural, and economic frontier, Afghanistan’s history as a resource frontier remains understudied. And yet, such an analytical lens brings into focus the overlooked continuity between colonial and neocolonial projects of exploratory geology, illuminating how Afghanistan’s modern history has been shaped by successive waves of geological exploration, resource mapping, and extraction. Nineteenth-century British geological surveys, Soviet mineral assessments of the 1970s, and present-day U.S. resource mappings have all reimagined Afghan territory as a space of untapped potential. By enriching existing scholarship on Afghanistan as a frontier with the concept of the resource frontier, I uncover new dimensions of the country’s integration into global networks of exchange—in things sacred (Green Reference Green2017), precious (Lin Reference Lin2021), and industrially profane—while exposing how these material practices have shaped broader power structures. This shows that Afghanistan’s frontier status indexes not merely its political or cultural marginalization, but also its continual reimagining as a space of resource potential.Footnote 7

Rather than simply juxtaposing the frontier concept with the imaginary of El Dorado, I consider El Dorado through geological expeditions, which allows me to bring Afghanistan into a global resource imagination. Like its mythical predecessor, Afghanistan has been repeatedly cast as a land of untold mineral wealth. How, then, has this ongoing imaginary shaped both colonial and contemporary approaches to the country, driving cycles of exploration, speculation, and, belatedly, disappointment?

The El Dorado myth, when viewed through the phenomenon of geological exploration, transforms into a narrative of scientific pursuit, resource potential, and the materialization of imperial ambitions. In Afghanistan, geological expeditions have played a vital role in shaping both the country’s frontier status and its El Dorado-like allure, evident in perennial invocations of Afghanistan’s vast mineral deposits, valued by recent U.S. geological surveys in the trillions of dollars. These geological expeditions, beginning in the nineteenth century and continuing to the present day, have served various goals, including contributing to the global body of scientific knowledge, informing colonial and neocolonial policies, aiding in nation-building efforts, and perpetuating the narrative of Afghanistan as a land of “untapped wealth” (Simpson Reference Simpson2011). The quest for minerals, driven by these surveys, has repeatedly recast Afghanistan’s frontier status—transforming it from a political buffer into a resource frontier, from a backwater into a potential mineral-state. This imaginary has not only influenced foreign interventions but has also shaped Afghan state-building efforts and development strategies.

A closer look at exploratory geology in the nineteenth century and the discovery of industrial-use minerals by British geologists in Afghanistan foregrounds the dependence of colonial powers on knowledge of the earth’s structure and its mineral resources as the Industrial Revolution accelerated. This history offers a new lens through which to view Afghanistan’s integration into wider networks and power structures, spotlighting its past and present position in global extraction regimes.

Exploratory geology forms an epistemological register through which value is produced today. It results in the creation of what Taussig (Reference Taussig2004), in his work on Colombian gold mining regions, refers to as “sacrifice zones”—areas where resource extraction takes precedence over environmental and social concerns. These zones emerge through “violent environments” (Peluso and Watts Reference Peluso and Watts2001), where extraction, knowledge production, and conflict become mutually constitutive. As Gordillo’s (Reference Gordillo2021) work on terrain demonstrates, the materiality of resource-rich landscapes shapes not only extraction practices but also patterns of military control and resistance, making geological knowledge inseparable from questions of power and violence.

In recent decades, anthropologists, geologists, and historians of mining have produced an impressive body of work on mining in the Global South and its impact on a wide range of issues that include labor exploitation (Nash Reference Nash1993; Taussig Reference Taussig2010), resource scarcity and human migration (Bebbington and Bebbington Reference Bebbington and Bebbington2018), environmental degradation (Townsend Reference Townsend2017; Jacka Reference Jacka2018), and indigenous land loss (Macintyre Reference Macintyre2007; Li Reference Li2014), all of which provoked protests by indigenous peoples at global scales (Kirsch Reference Kirsch2014). This scholarship has increasingly recognized how geology has become “a principal field and framework in the social sciences and humanities to understand anthropogenic environment crises” (Oguz Reference Oguz2020) and offers new ways to theorize the relationship between human imagination, scientific knowledge, and resource materialities. Since the early 2000s, geographers have made key interventions in theorizing these dynamics, with Watts (Reference Watts2004) demonstrating how oil extraction produces particular forms of governmentality and power relations that complicate simplistic “resource curse” narratives (Reyna and Behrends Reference Reyna, Behrends, Behrends, Reyna, Behrends and Schlee2011). Building on this work, Richardson and Weszkalnys (Reference Richardson and Weszkalnys2014) argue that resources emerge through complex assemblages of techno-scientific practices, infrastructures, and changing political-economic conditions. These “resource ontologies” contour not only how minerals are extracted but also how they are imagined and valued before extraction begins.

Tsing’s (Reference Tsing2000) pioneering work on the relationship between geological speculation and financial markets tracks how scientific practices of resource assessment generate particular forms of value even before extraction begins. Building on this insight, recent geographical scholarship has examined how exploratory practices generate resources through anticipatory politics and knowledge controversies (Kama Reference Kama2020; Reference Kama, Himley, Havice and Valdivia2021). As Kama shows, geological exploration involves complex temporalities that oscillate between resource presence and absence, shaping how resources are imagined and economized prior to extraction. Still, scholars have yet to fully account for the stage prior to mining—reconnaissance geology—and how it relates to the precarity of local actors in their pursuit of mineral commodities (see d’Avignon Reference d’Avignon2018; and Kneas Reference Kneas2018). Resources are not simply discovered—they are produced through complex interactions between scientific expertise, market desire, and local knowledge (Ferry and Limbert Reference Ferry and Limbert2008). Grasping this has profound implications for how we understand speculative frontiers like Afghanistan, where geological knowledge shapes resource imaginaries. Walsh’s (Reference Walsh2012) ethnography of sapphire mining precisely examines these dynamics, showing how the disconnection between local miners’ epistemologies and global market valuation shape resource extraction on the ground.

I begin this essay by tracing the history of geological exploration globally, exploring how it casts Afghanistan as a site of wealth and its mineral occurrences as economic assets. Following Weszkalnys’ (Reference Weszkalnys2016) attention to “resource affect,” I examine the impetus behind the intensification of geological exploration and show how imperial projects intersect with global capitalism and geopolitics. I then turn to the perspectives of an emerald mine-holder. Through him, I account for the interests, choices, and struggles of those who are deeply emmeshed in the extractive industry and connect them to the materiality of resources. My claims build on anthropological and historical research that demonstrate how imperial territorial logics are reinscribed in the regulation of extraction across the postcolonial world (d’Avignon Reference d’Avignon2022). Finally, I argue that histories of geological exploration are fundamental to knowledge production and valuation in and of Afghanistan today and show how value is constantly produced through the labor and labored knowledge of extraction itself.

El Dorados: Geological and Gemological

During his 1982 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Gabriel García Márquez characterized El Dorado as an elusive, mythic land entirely beholden to the whims of cartographers.Footnote 8 This colonial and imperial mapping of El Dorado in the cultural imaginary has shaped extractivist enterprise since colonial times (Rogers Reference Rogers2019). In the Americas, colonial powers introduced extractive operations that have reshaped ecosystems and exploited indigenous and non-white communities since first contact—patterns that persist in contemporary capitalist structures to this day. In nineteenth-century Colombia, cartography served as more than mere documentation—it became a powerful tool of state formation, imposing order on nature through the very act of mapmaking (Taussig Reference Taussig2004: 198). This process of mapping and quantifying nature, which Taussig describes as a “crude magic,” parallels the geological surveys and resource mapping efforts in Afghanistan.

Anthropologists have shown that resource identification and mapping—far from being neutral scientific endeavors—are deeply enmeshed in the “theater” of state-making and the domination of nature (Tsing Reference Tsing2005; Li Reference Li2014). While geological exploration has historically privileged the pursuit of industrial minerals, the sensual allure of decorative stones like emeralds and lapis lazuli remain underexplored, and their allure returns us to El Dorado’s original promise of luxury, beauty, and abundance—in distinct contrast with latter-day industrial fantasies of crude oil, lithium, and the like. In much the same way, the hunt for Afghan gems blurs the lines between nature and artifice, science, and myth—an embodied dynamic that instantiates Taussig’s (Reference Taussig2004: 200) observation that nature and artifice are mutually constitutive.

Afghan emeralds and lapis lazuli thus emerge as fetishized objects whose cultural significance exceeds their empirical properties. Pietz shows that the fetish represents a unique case where material properties and social interpretation are inseparably entangled. Unlike idols, which are material representations of non-existent deities, fetishes possess what Pietz calls “untranscended materiality” (Reference Pietz2022: 7). The uncertainties of mining, the demands of artisanal and skillful cutting, and the subjective nature of color assessment create a valuation process that resists standardization (Brazeal Reference Brazeal2017). Unlike diamonds, for which official prices are published weekly, emerald values are negotiated through countless, ephemeral face-to-face interactions, with each individual stone’s value varying by orders of magnitude as it changes hands. This ritualized exchange process, as Calvão notes (Reference Calvão, Drazin and Küchler2020), reveals how gems accrue value through multiple registers beyond numerical calculation.

These distinctive valuation practices shape what Gudynas calls “modes of appropriation”—the specific ways natural resources are extracted and commodified within particular socio-economic contexts (Reference Gudynas, Munck and Wise2018: 392). In Afghanistan, emerald appropriation operates simultaneously as an economic and ecological process. When a mundane rock is transformed into a luxury good, its material precarity becomes central to negotiating its worth. Like El Dorado’s promise of alchemical possibilities, this transformation transcends material calculations by producing value through the relationships, labor, and rituals that render these bits of lithosphere legible as commodities.

The transformation of rocks into jewels—into a new El Dorado treasure—binds Afghanistan’s emeralds to larger histories of colonialism and capitalist extraction. The pursuit of these precious stones parallels historical quests for gold and land, and embodies narratives of desire, power, and wealth that scholars have identified as driving forces behind exploration and subsequent exploitation (Tsing Reference Tsing2000; Ferguson Reference Ferguson2005; Li Reference Li2015; Appel Reference Appel2019). Even the geological prospecting techniques used to locate gem deposits remain inextricable from commercial hopes that echo El Dorado’s aspirational mystique.

Beyond their economic significance, gems inhabit a distinctive cultural realm that prioritizes aesthetic appeal, luxury status, and symbolic meaning over utility. Afghanistan’s emeralds exemplify this dynamic, having been coveted for millennia as objects of desire rather than industrial inputs. Their value derives from a synthesis of sensory, cultural, and symbolic registers that constitute a distinct capitalist regime—one that differs markedly from gold’s fungibility or coal’s value as fuel. Yet, the quest to locate these aestheticized treasures relies on the same established geological techniques used for all mineral prospecting.

Over the past two centuries, geological exploration has provided insights into the landscape and rock formations of a globally connected Afghanistan. These subterranean inventories have enticed both local and international actors, each pursuing distinct agendas. The interplay between resource extraction, geological exploration, and chronic conflict has therefore transformed mineral discovery in Afghanistan from a lucrative opportunity into a geopolitical imperative. I draw inspiration from Mitchell’s work, which challenges capitalist-technocratic determinism and emphasizes the power of the military-industrial complex (Reference Mitchell2013), to explore how Afghanistan’s resource landscape has been shaped by multilateral forces. These include geological exploration, industrial expansion, fragmented state power, and U.S. imperialism. Geopolitical conflict and the global political economy have not only driven the quest for resources but also dictated the very methods of geological exploration. The convergence of imperial science, military intervention, and capital accumulation has positioned Afghanistan at what Tsing calls a “salvage frontier,” where intensified resource extraction coexists with seemingly contradictory efforts at environmental protection (Reference Tsing2003). As Moore (Reference Moore2000) described in his work on sugar frontiers, this type of resource extraction transforms entire landscapes through “frontier industrialization.” Here, as Bartoletti (Reference Bartoletti2023) shows in his study of Habsburg mining experts in Brazil, geological knowledge production serves as an essential mediator between imperial ambitions and local realities, where land is valued both for its extractive potential and its geopolitical significance in larger conflicts.

Prospecting Afghanistan in the Nineteenth Century

Despite having long captivated the imperial imagination, Afghanistan’s mineral wealth remains puzzlingly under-mapped. When Christie’s auctioned a ring inlaid with a 10.11-carat Afghan emerald for US$2.2 million in 2015, it highlighted the perennial rediscovery of Afghanistan’s resources (Christie’s n.d.). Historians and archaeologists have long documented the ancient lapis lazuli deposits that first made Afghanistan famous, but the appearance of high-caliber Panjshir emeralds on the global market as late as the 1970s indicates that Afghanistan’s mineral resources continue to be “newly discovered.” This pattern of recurrent revelation signals the region’s complex political history as well as its distinctive status within imperial scientific production. As geology emerged as a distinct scientific field, its application in Afghanistan took on a unique character: colonial and neo-imperial interests in development potential perpetually confronted limits to systematic survey work. Even ornamental and decorative crystals became entangled in this broader pattern of interrupted knowledge production, fueling the unrelenting idea and reality that this El Dorado remained uncharted.

The nineteenth century witnessed an explosion in geographical scholarship, and its breadth and authority soon extended far beyond travelogues. With their separate sections on travel, history, and detailed geography, texts like Elphinstone’s Account of the Kingdom of Caubul (Reference Elphinstone2011[1815]) were early predecessors to more comprehensive regional surveys.Footnote 9 The ordering and classification of geographical knowledge was characteristic of early British colonial rule not only in Afghanistan but across South Asia (Gardner Reference Gardner and Hanifi2019). By the mid-nineteenth century, this epistemology was clear in official publications like gazetteers at the district, provincial, and imperial levels. A strict hierarchy of geographical features began to emerge, with borderlines (often demarcated by rivers, mountains, or watershed limits) at the top.

This growing focus on comprehensive geographical description captures the nineteenth-century mania for delineating, cataloguing, and controlling colonial domains. Enthusiasm for epistemic ordering found its most technically sophisticated expression in the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India (1802–1861). As Edney shows, the surveyors’ practice of “occupying” high points to create interconnected triangles across the landscape merged technical precision with territorial conquest (Reference Edney1997: 105). Afghanistan, however, remained conspicuously outside of this mathematical-cartographic regime. This spatial exclusion was not merely technical but epistemological; while British India was rendered knowable through this triangulation method, Afghanistan occupied a more ambiguous zone. Systematic triangulation may have been impossible there due to the Anglo-Afghan Wars (1839–1842, 1878–1880, and 1919), along with continual Afghan resistance to British imperial ambitions more generally.

As geology professionalized during the Victorian era, it became a discipline ever more deliberately conditioned by imperial knowledge and objectives (Stafford Reference Stafford2002: 8). South Asia became a preeminent site for colonial surveys by the British, and the Geological Survey of Great Britain was established in 1835, providing a model that extended into imperial territories.Footnote 10 This was a critical institutional framework that facilitated the integration of geology into imperial administration. Sangwan (Reference Sangwan1994) provides a concise overview of the history of geological research in British India as it transitioned from reconnaissance surveys by “gentleman scientists”—often without clear economic goals—to purpose-driven and increasingly professionalized efforts to identify local mineral resources for exploitation. Geological surveying in the early nineteenth century was often preoccupied with coal—a focus that was formalized through institutions like the Committee for the Investigation of the Coal and Mineral Resources of India, established in the 1830s (Shutzer Reference Shutzer2021). As geologists conducted more and more surveys, the discipline also played a vital role in catalyzing the empire’s technological advantage in discovering mineral resources (Cahan Reference Cahan2003).

Like geography and cartography, geology in nineteenth-century Afghanistan was much less systematic than it was in India and remained a largely opportunistic endeavor. The first amateur geological explorers were often embedded within the paramilitary units of the East India Company and, later, the British Indian Army. As Stafford notes, “geology marched in the van of the Indian Army: officers made observations and collections on behalf of the London Society in Afghanistan, Sind, and Punjab” (Reference Stafford and MacKenzie1990: 71). As they traversed Afghanistan, aiming to gain a strategic advantage over Russia, their efforts were impeded by the same political and military constraints that had limited cartographic work elsewhere. Especially so after the commercial expedition to Kabul led by Captain Alexander Burns (Grout Reference Grout1995: 192), which ultimately propelled the East India Company into the First Anglo-Afghan War. This de facto militarization of geological work stood in stark contrast to other scientific pursuits being carried out under the aegis of empire, particularly botany, which operated through established institutions like botanical gardens.Footnote 11

The ad hoc nature of early geological exploration is evident in contemporaneous reports. In 1841, an article in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, which described Captain Drummond’s travels through Afghanistan to survey mineral deposits, referenced an earlier “voluminous Geological Report” prepared by Captain Herbert, which had attracted the attention of “practical men and capitalists in London” (Drummond Reference Drummond1841: 76). Drummond’s observations of copper deposits and mine sites indicate an early exploratory approach focused on cataloging observable characteristics for potential economic exploitation. Given the vitality of transport links to these expeditions, many geological investigations focused on areas adjacent to main caravan routes. This infrastructural dependency meant that geological knowledge was shaped as much by the physical constraints and hardships of literal movement through Afghan territory as by more abstract political circumstances. Drummond’s observations of copper deposits and mine sites show this pattern. He reported that, in addition to the many mineral deposits he surveyed along established routes, the extent of excavations and the amount of slag at various Afghan mining sites boded well for mining investment (ibid.: 80–81). His lush descriptive comparisons also underscore the simultaneous development of imperial expansion within a fledgling capitalist mining economy, which dovetailed with the traditional prospecting method of directly observing mineralization.

Military officials and imperial policymakers were the real beneficiaries of geological surveys, given that they saw geological knowledge in terms of military advantage rather than scientific or economic interest. The case of Captain Alexander McMahon and Lieutenant-General Charles Alexander McMahon, a father and son duo, exemplifies this tension between systematic knowledge production and opportunistic exploration. While ostensibly engaged in the political task of delineating the boundary between Baluchistan and Afghanistan, the McMahons simultaneously conducted a geological expedition, surreptitiously collecting mineral specimens throughout their journey.

Boundary demarcation, while seemingly about territorial control and expansion, also created opportunities for extensive geological surveying, a widespread pattern across British imperial territories. The mineral specimens collected during these expeditions served various purposes, from advancing geoscientific knowledge to evaluating the region’s economic potential, as is evident in the McMahons’ Reference McMahon and McMahon1897 publication on crystalline rocks. It’s important to note that, much like d’Avignon (Reference d’Avignon2022) has shown for Senegal, these systematic assessments of regional physiography and resources relied heavily on local expertise that was often subsequently effaced or merely noted in passing.

The British maintained what they called “a comprehensive interest” in Afghanistan’s resources that lasted until their final retreat in 1919 following the Third Anglo-Afghan War (Ali and Shroder Reference Ali and Shroder2011: 5). Sir Macnaughten articulated this imperial stake in his 1841 vision from Kabul, where he argued that resource development would both enrich the East India Company and reclaim the “wild inhabitants … from a life of lawless violence” (quoted in Grout Reference Grout1995: 193). Though the British never established a firm enough foothold on Afghan regions to develop commercially viable mines, their geological surveys did lay crucial groundwork for later exploration.

Coal deposits naturally became the primary focus of these systematic investigations. Beginning with Griesbach’s pioneering documentation in 1885 and 1887 (Reference Griesbach1887), followed by Sir Hayden’s work in 1911 (Hayden Reference Hayden1911), a succession of geologists conducted detailed surveys from the 1940s to the 1970s that are now preserved in the Afghan Geological Survey archives. These archives also contain numerous Soviet-era reports and maps from the 1960s and 1970s that were once accessible through the AGS Data Center in Kabul but are no longer available for public viewing.Footnote 12 These expeditions relied on what Turner has termed the “geological walk” (Reference Turner1987: 300–9)—a scientific approach centered on meticulous fieldwork and detailed on-the-ground sketch mapping.

While British reconnaissance geology primarily targeted unglamorous fossil fuels like coal, imperial prospecting extended to precious gems, a sector that complicates conventional narratives about resource extraction in the “capitalocene” (Moore Reference Moore2017). Unlike coal and industrial minerals, which align more neatly with imperial industrial development, gemstones reveal new facets of nature’s commodification in frontier spaces. As we turn to the recent history of gemstone surveying in Afghanistan, we see how these tangible assets became enmeshed in new configurations of foreign agencies and state power, simultaneously extending and transforming established patterns of geological exploration.

Mapping Afghan Gems

In the surveys discussed thus far, Afghanistan operated as a site of imperial knowledge production, where observations by military personnel rendered complex and inscrutable terrain into legible colonial territory. To turn these diverse landscapes into systematic geological reports, without modern prospecting technologies required intimate encounters with local populations and their mining practices. How might we recover these interactions that shaped geological knowledge but are often obscured in official accounts? The detached, methodical tone of British geological reports masks the intensely interpersonal nature of mineral prospecting, which depended on indigenous expertise, involved complex negotiations with local power structures, and benefited from local knowledge about deposit locations accumulated across generations. Moreover, these reports often elided the physical demands of accessing remote mining sites and navigating challenging terrain. Embedded within these seemingly objective geological assessments, then, are the personal, political, and embodied experiences of both British surveyors and Afghan miners.

These intimacies define emerald mining, as well. Emeralds, the green variety of the mineral beryl, derive their spectacular color from various trace elements including chromium, vanadium, and iron (Sinkankas Reference Sinkankas1981). These coveted gems played a significant role in the cultural history of the early modern world. In his study of Colombian emeralds spanning the early sixteenth to late eighteenth centuries, Lane (Reference Lane2010) shows how European entrepreneurs transformed the arduous manual labor of indigenous peoples and African slaves into a highly profitable enterprise.Footnote 13 While many Colombian emeralds went to Europe, the rest were funneled into the Islamic empires of the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals, entangling the brutal colonial exploitation of natural resources with lavish imperial consumption.

It is difficult to gauge the precise historical significance of Afghanistan, particularly the Panjshir Valley, as a supplier of emeralds. However, some sources place the first mention of Afghan emeralds (“smaragdus”) as early as 77 CE (Bowersox et al. Reference Bowersox1991). An oxygen-isotope gemological analysis of an emerald from the treasury of the Nizam of Hyderabad, in India, suggests that Panjshir may have been a source of gems for southern India as early as the eighteenth century (Giuliani et al. Reference Giuliani2000).

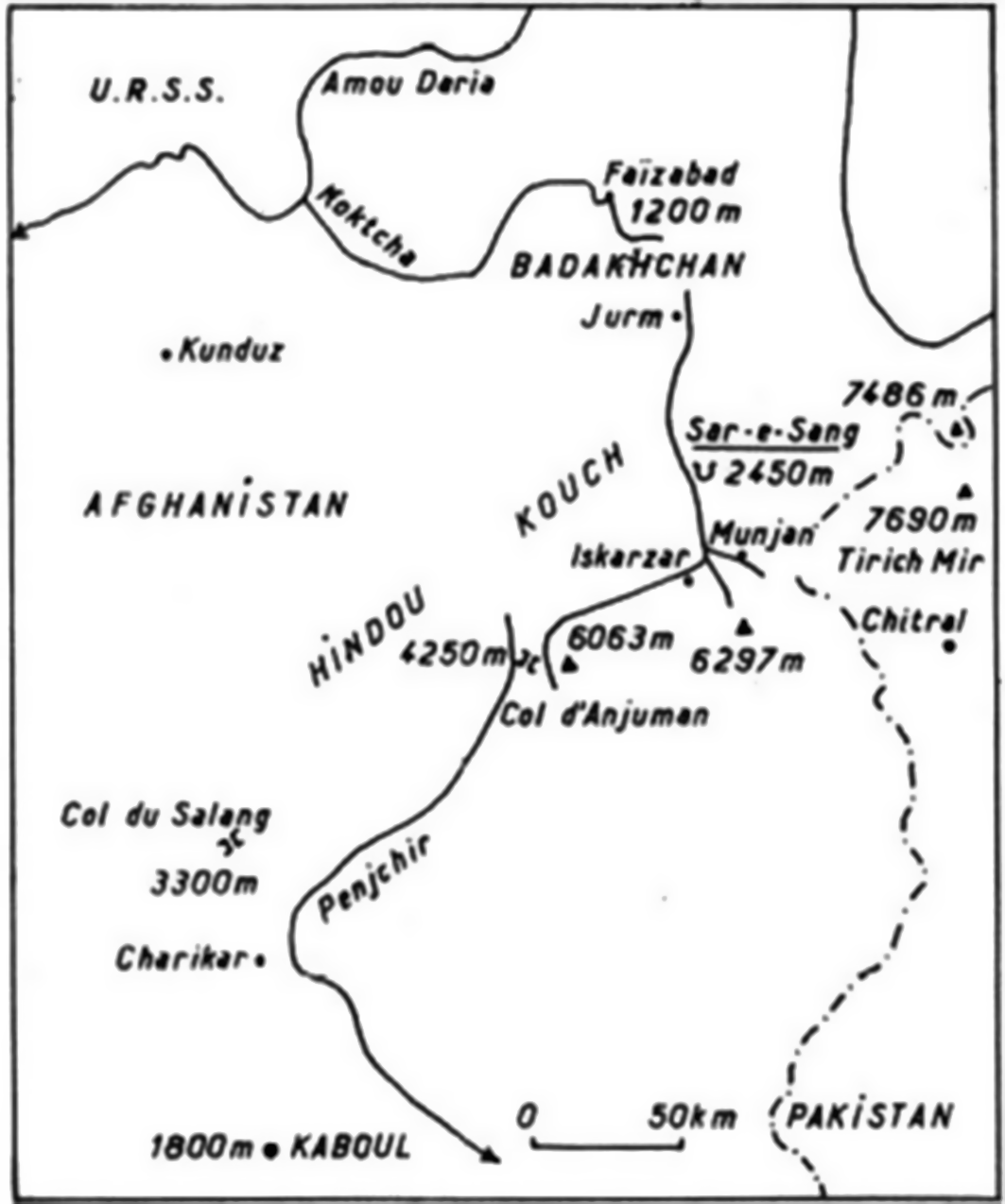

The 1970s marked a significant period in the study and documentation of Afghanistan’s emerald deposits, with French mineralogists playing a key role. The acclaimed French mineralogist Bariand published one of the pioneering works on Iran and Afghanistan’s gem deposits, adopting an approach to mineralogy that, like that of other naturalist adventurers in the 1960s and 1970s, was heavily based on field exploration (Map 1).Footnote 14 His work in Afghanistan in the 1970s fortuitously coincided with a waxing international interest in the mineral trade. He would go on to participate in major mineralogy exhibitions, such as the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show in the United States, beginning in 1972.

Map 1. J. Blaise and F. Cesbron, “Geographical Location of Lapis Deposits in Badakhshan,” Bulletin de Minéralogie, Reference Blaise and Cesbron1966, 334, fig. 1. At: https://www.persee.fr/collection/bulmi.

With his colleague, Poullen, Bariand co-authored a groundbreaking piece on Panjshir’s emeralds in the Mineralogical Record (Reference Bariand and Poullen1978). They posited that the existence of Panjshir emeralds was only made possible by Russian geologists who first discovered the deposit. This French-Soviet exchange of geological knowledge marked a significant shift in understanding Afghanistan’s mineral wealth, though the physical traces of the work remain largely hidden from view. The Soviet geological expeditions left behind volumes of field notes and maps, documents that carried the imprint of years spent traversing Afghanistan’s varied landscapes. Yet these material records have been rendered almost spectral—some carefully cloistered behind institutional walls, others reduced to ash when a U.S. B-52 bombed the Afghanistan Geological Survey office in late 2001.

I was fortunate to interview Abdul Samad Salah, one of the few figures who lived through this entire period of shifting geological alliances. Born in 1935 and educated at Kabul’s Nejat School, Salah studied geology and engineering at Munich University before returning to Afghanistan in 1960, when his appointment to the Ministry of Mines and Industries launched a remarkable career. As he worked alongside German and Soviet geological missions, Salah’s ability to skillfully navigate intricate scientific and cultural contexts—aided by his fluency in German—proved invaluable. He eventually rose to become the General Director of the (AGS) Survey and later the Deputy Minister for Mines and Industries (1973–1978), thus exemplifying the pivotal role that European-educated Afghan experts played in integrating foreign geological missions into national institutions.Footnote 15 As a member of the Board of Experts and the Department of “Exploitation”—or “Excavation,” as he later recalled it with some uncertainty—Salah was uniquely positioned to understand both Soviet and German approaches to geological exploration. The arc of his career, which extended into the Najibullah era, during which he served as Minister of Petrochemical Industries, coincided with a critical period in Afghanistan’s geological mapping efforts, from the relative stability of the 1960s through the profound disruptions of the Soviet invasion.

Salah described a shift in Afghanistan’s geological priorities after the Soviet invasion.Footnote 16 The pre-invasion period was characterized by ambitious, systematic exploration intended to build a comprehensive understanding of Afghanistan’s mineral wealth, central to which was an extensive geological mapping program. It was conducted at 1:250,000 scale and supplemented by targeted exploration of strategic resources like oil and gas, but the Soviet invasion threw that methodical approach into turmoil. Geological work increasingly targeted specific deposits, particularly copper and rare metals, with an eye toward eventual mining concessions. This narrowing of focus, according to Salah, gave way to a more fragmented approach following the Soviet withdrawal. Throughout these changes, gemstone deposits—with the notable exception of lapis lazuli—remained largely outside official geological programs. While lapis lazuli remained a legally mined resource, other precious stones like emeralds were relegated to a parallel economy of informal extraction and smuggling, largely unmapped and unmonitored by state geological efforts. French mineralogists like Bariand were the first to fill in this gap with their documentation of emerald occurrences in the early 1960s.

Since then, several geologists and mineralogists—beginning with Samarin and Akkermantsev (Reference Samarin and Akkermantsev1977), followed by Bowersox (Reference Bowersox1985), and Kazmi and Snee (Reference Kazmi and Snee1989)—have documented the distinctive characteristics of Panjshir emeralds, noting that those from this region fall along a wide spectrum of quality. Crystals typically weigh between 4 and 5 carats, although specimens as large as 190 carats have been reported (Bowersox Reference Bowersox1985), and they tend to exhibit what geologists and gemologists call color zoning, with darker green exteriors and paler interiors—an ombré that traders prize. In fact, while Panjshir emeralds bear a close chemical resemblance to Colombian emeralds, their unique trace element profile distinguishes them from emeralds sourced from other parts of the globe, including neighboring Pakistan.

By the 1990s, non-fuel minerals had become a vital commodity in Panjshir, sustaining local livelihoods and subsidizing the Northern Alliance. A former emerald trader from the region recalled a time when mines were entirely under the control of Northern Alliance leader Ahmad Shah Massoud.Footnote 17 Gems were reportedly a major source of revenue for him, along with limited income from Iranian aid. Massoud taxed lapis lazuli and emerald production and trade, collecting ushr (Islamic tax) from mine-holders and zakat (charity) from traders (Rubin Reference Rubin2000). Two years after establishing an emerald monopoly in 1997, he signed a deal with the Polish firm Inter Commerce to market the gems internationally. While estimates value the current annual trade at US$40–60 million, some believe the joint venture could have yielded as much as $200 million per year (Chipaux Reference Chipaux1999). This absolute discretion over subterranean resources illustrates how, as Oguz (Reference Oguz2021) lays out, underground spaces can enable forms of resistance against both state and non-state domination. In Panjshir, the emerald and lapis mines served as not only economic assets but also strategic spaces that helped the Northern Alliance maintain autonomy. Oguz’s concept of “geopower” sheds light on how the materiality of these mineral deposits opened fresh political possibilities: the challenging terrain and hidden nature of the mines made them difficult to seize or manage from the outside, while their high value provided sustainable funding for local governance structures. Subterranean resources can reconfigure power relations between multiple above-ground actors—local communities, resistance movements, international firms, and competing political authorities—rather than just affecting state-society relations.

Today, the primary sources of gem materials are located in the northeastern region of Afghanistan: Pegmatite gems such as tourmaline, kunzite, and aquamarine have been discovered near the border with Pakistan, in regions like Nuristan and Kunar; meanwhile, corundum gems like sapphires and rubies are predominantly found in Laghman and the southern part of the Sorobi district, within Kabul province. Emeralds, on the other hand, have only been found in the Panjshir Valley, which I visited in November 2019 and where—as I mentioned at the beginning of this essay—a DAI- and USAID-sponsored team collectively captured a geophysical map of the region in 2009.

The rationale behind the 2009 project to map emeralds seemed straightforward. Surveying and mapping this lucrative terrain would allow the Afghan government to claim all land and production rights in mineral-rich zones, the better to monitor and facilitate resource extraction policies such as licensing and stable ownership.Footnote 18 The importance of the geophysical surveying project, a decade after the U.S. occupation of Afghanistan began, lies in its intersections with development narratives, which pushed for more scientific forms of mineral exploration in hopes of achieving rational and stable politics. Reading resource exploration in a long(er) durée shows that it is instead imperial and neo-imperial politics that tends to incentivize surveyal in places like Afghanistan. As deposits become legible for extraction, new fault lines emerge around land rights, indigenous displacement, and the distribution of mineral wealth. Tensions that appear fueled by resource nationalism or separatism cannot be severed from the resources—metals, fuels, and gems—that are enmeshed in sociopolitical worlds they help constitute.

Narratives of Value: From the Descriptive to the Three-Dimensional

The advent of modern prospecting technologies has enabled the efficient mapping of mineral resources over wide areas. Techniques like aerial imagery and remote sensing turbocharged mineral exploration across Afghanistan after the 2001 U.S.-led invasion. However, it is important to note that, while aerial survey techniques are effective for perceiving deposits of iron and hydrocarbons, they are less reliable for locating gemstones. The discovery of pegmatite gemstone pockets, for example, typically requires “hundreds of meters of tunneling and a great deal of luck” (Cook Reference Cook1997: 6). Gemstone prospecting still relies on more traditional, ground-based exploration methods, which in turn rely on the labor and knowledge of local people.

In 2006, U.S. researchers conducted airborne magnetic, gravity, and hyperspectral surveys across over 70 percent of Afghanistan within a two-month period. While the magnetic surveys probed for iron-bearing minerals deep underground, gravity surveys also identified sediment-filled basins potentially rich in hydrocarbons. Hyperspectral sensors analyzed reflected light to map each mineral. From 2004 to 2007, the U.S. Geological Survey collaborated with the Afghanistan Geological Survey to integrate these new datasets with older survey data, creating a preliminary assessment of non-fuel mineral resources.Footnote 19 This foundational survey was expanded in 2009 as additional airborne surveys and remote sensing filled gaps and validated earlier data on mineral deposits. By consolidating the data into a high-resolution Geographic Information System, geologists achieved a comprehensive survey of Afghanistan’s surface mineralogy. For the first time, a nation’s geology was mapped completely from the air (BBC 2012).

Geological mapping and analysis encompass more than physical orientation—there are temporal and ethical dimensions as well because resource mapping demands that we envision how their extraction could shape a nation’s future development and wealth. The British Geological Survey, commissioned to build capacity at the Afghanistan Geological Survey, described the country’s mineral potential as a means to “generate revenue to help revive the economy and rehabilitate the country” (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2005). Political and economic incentives have consistently motivated post-invasion mapping efforts within rebuilding agendas.

Afghanistan’s striking underground wealth captured wider attention in 2010 when a New York Times piece proclaimed, “Vast Mineral Riches in Afghanistan” and sparked frenzied speculation. Some predicted mining would spur development and end conflict, while others claimed mineral resources had motivated the U.S.-led invasion. Since then, Afghanistan’s deposits of copper, iron, oil, lithium, and gemstones have been valued at over US$694 billion. This valuation builds on a 1995 U.N. assessment documenting over 1,400 Afghan mineral occurrences, including “world-class deposits of copper, iron and gemstones” (United Nations 1995). Advocates for resource development argue that fully developing major sites like the Aynak copper vein and Hajigak iron ore could generate thousands of jobs and over $1 billion in annual government revenue, which could finance infrastructure projects like roads, railways, and power plants (Amin Reference Amin2017).

This comprehensive vision of Afghanistan’s mineral wealth cemented its status as a latter-day El Dorado. But what this will ultimately mean varies depending on who is being asked. Prospectors and capitalists may fantasize about subterranean treasures awaiting extraction for fabulous profit, while local miners seek fair pay for their labor in mines often owned by others. The same geological phenomenon yields divergent rewards. The nature and trajectory of any El Dorado emerges from the intersections of rumor, aspiration, and exploitation. Geological surveys manifest not only material endowments, but social negotiations around the anticipated rewards to follow when the Earth’s subsurface is exposed.

As high-level discussions continue, small-scale mining of gemstones—still informal and illicit—has become a significant way of life for many residing in the gem-laden landscapes of the Hindu Kush. Rather than boycotting mining projects, local inhabitants seek to participate in—if not govern—those that come into existence, spurred by global and local politics. While touted as a collective national resource, however, Afghan gems often fill the coffers of local strongmen—a scenario that is admittedly far from the free-trade ideals of “reconstructing” Afghanistan.

Anthropologists have long wrestled with the promises and pitfalls of extraction-oriented development, studying how hopes for the future inform a range of social dynamics and anticipatory actions, which include the establishment of an economy of expectation (around oil), as is the case in São Tomé e Príncipe (Weszkalnys Reference Weszkalnys2016), and the reconfiguration of land ownership and governance practices, as in Papua New Guinea (Jacka Reference Jacka2019; Golub Reference Golub2014). Within development economics, the “resource curse” tends to link mineral wealth to unrest and inequality rather than prosperity (Auty Reference Auty1994; Davis Reference Davis1998; Freudenburg and Wilson Reference Freudenburg and Wilson2002). Yet the scales of “intervention” in Afghanistan complicate such simplistic causal links between minerals and violence. Recent scholarship suggests that different resources generate distinct patterns of conflict based on their material properties and modes of extraction (Le Billon Reference Le Billon2001; Ross Reference Ross2015). The unique materiality of gemstones—their small size, high value, and easy portability—creates sophisticated social and economic networks that differ markedly from the large-scale extractive operations that accrete around other resources, for example crude oil. Gems circulate through “interlocking underworlds” based on personal trust and family connections, operating through horizontal organizational structures (Naylor Reference Naylor2010). This stands in marked contrast to hydrocarbon extraction’s requirement for corporate hierarchies, and this distinction proves critical in Afghanistan, where small-scale gem extraction operates through vastly different social and political networks than proposed hydrocarbon development.

Rather than assuming a universal “resource curse,” scholars increasingly examine how resource materialities interact with specific political economies to produce conflict (Bridge Reference Bridge2009; Watts Reference Watts2004). The transformation of Afghanistan’s gem deposits from geological features to valuable commodities involves multiple forms of violence. This includes not only physical violence over resource control, but also the structural violence of dispossession and the epistemic violence that arises from privileging certain forms of geological knowledge over local know-how.

Subterranean Lure

Wahab was not always a mine-holder. He was from a family of dealers in precious stones. The profession had not only sustained his family in times of exile from Afghanistan in the 1980s but had also allowed them to accumulate wealth. Before the April 1978 coup that overthrew Daoud Khan, Wahab’s family dealt in lapis lazuli, categorized as a “semi-precious” stone, with a vast clientele in the United States, Switzerland, China, and Hong Kong.

As various parts of Afghanistan descended into turmoil throughout the late 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s, Wahab, then a young man living in Panjshir, found ways not only to make a living by buying from his extended networks in the Sar-e-Sang mines of Badakhshan, where lapis was primarily mined, but also by collaborating with other businessmen to form trade networks that would take them up the value chain to the epicenters of gem consumption and distribution: Bangkok and Hong Kong. By the late 1970s, he had set up a wholesaler company in Hong Kong that catered to clients from across the region. Over the next few years, Wahab accumulated enough money to sustain his extended family throughout the turbulent times of jihad (the Soviet Afghan War, 1979–1989). In the early 1980s, he relocated his immediate family to the city of Peshawar across the border in Pakistan, which was by then already home to the most significant population of Afghan refugees. Wahab’s exile was a comfortable one, especially when compared to the plight of his non-merchant-class comrades.

Wahab’s transition from gem dealer to mine-holder entailed an entry into a world of heightened stakes—where greater profits came hand-in-hand with graver risks. His mine, one of many scattered across Afghanistan’s emerald belt, lies among the rugged mountains some 70 miles northeast of Kabul, in a chain stretching from Khenj village to Dest-e-Rewat. Here, among peaks that soar from 7,000 to 14,300 feet above the Panjshir River’s eastern banks, scattered tunnels bear witness to the persistence of extractivism: passages blasted by dynamite and carved through the arduous labor of Khenj miners. I chose a late-November morning to visit, when the mining season wanes before its winter hibernation from November to March. The work is fraught with risk. Afghan miners descend into mining shafts, their paths illuminated only by lanterns and headlamps. Each movement is calculated to minimize the threat of cave-ins or falling rocks as they chip away at potentially emerald-bearing rocks. For the miners, this precarious enterprise demands total immersion. They spend days at a time in a makeshift shelter near the mine alongside other workers, descending to the nearest village only to replenish dwindling supplies before returning to the mountains.

The isolation of mining sites creates a web of dangers that extends beyond the mine itself. The nearest shelter—a basic structure serving as living quarters and storage space—lies some 30 to 40 minutes from the mine entrance. This distance can critically delay assistance in the case of accidents. Despite these many risks, men across Panjshir pursue this occupation due to the scarcity of employment. Wahab recounts that in other mining sites many choose to work under strenuous and dangerous conditions, sometimes waiting weeks to be paid, which depends entirely on the discovery and extraction of “gem-like” emeralds. Livelihoods, much like in other places of war, are dependent on the land, where life and death are also “an inescapable reality that must be minimized and managed” (Khayyat Reference Khayyat2022: 138). The precarious nature of miners’ employment is compounded by the interrelations of demands in the global emerald market.

In recent years, extraordinary Afghan emeralds have been arriving in unprecedented numbers at elite gemological laboratories like the Swiss Gemological Institute S.S.E.F. What sets these stones apart is not just their impressive size and quality, rivaling some of the finest Colombian specimens which have long been the gold standard, but also their unique gemological properties. Dubbed “Panjshir type II” by gemologists, these specimens have confounded experts with characteristics that set them apart from previously documented Afghan varieties (Krzemnicki, Wang, and Büche Reference Krzemnicki, Hao and Büche2021: 474).

These stones have galvanized the gemological community. Their remarkably consistent inclusion patterns, chemical compositions, and spectral features point to something extraordinary: a single, high-quality deposit unlike any other in the Panjshir Valley. For men like Wahab and his workers, the growing demand for these prized emeralds translates into more intensive mining operations, and greater risks, as they push further into the earth in search of the coveted gems.

The global shift has not only altered local mining practices but has also attracted increased attention from international gem traders and mining companies. The global significance of Panjshiri emeralds is perhaps best exemplified by the aforementioned “exceptional emerald ring” auctioned at Christie’s, where the stone received high praise for its “beautifully saturated green color combined with an exceptional purity” (Christie’s n.d.). The same report goes on to note that the emerald’s few inclusions are quintessential “hallmarks of emeralds from the Panjshir valley in Afghanistan, an area known since historic times for gem-quality emeralds.” Such global recognition creates a feedback loop, in which the mode of accumulation is based on intensified extraction and commodification of Panjshiri emeralds.

While the 2009 ground survey noted that mining methods have improved over the last thirty years in some parts of Panjshir, Wahab’s mine remained a traditional shaft-and-tunnel operation. The methods employed verge on what many U.S. geologists would consider rudimentary; Wahab’s miners rely on dynamite for excavation and blasting—a technique that Snee has described to me as “fairly primitive and dangerous.” This approach, while effective in breaking through hard rock, poses a clear danger to both the miners and the very emeralds they seek to extract (Figure 1). But the site was not entirely devoid of modern equipment. There were also a few expensive pneumatic drills, which are more efficient than traditional hand tools. In addition to the generators powering these drills, a rust-red Hitachi excavator sat perched on the tawny mountainside. In this historically militarized environment, the technological incongruity of the mining operation was hardly surprising.

Figure 1. Shafts and tunnels blasted into limestone during emerald exploration in Khenj District of Panjshir, Afghanistan (author’s photo).

Mining operates within a fraternal system,Footnote 20 in which each man is connected to all the others through his district of origin or his extended family. Sensing my unease and anticipating how others might react during my visit to his mine, Wahab was quick to usher me to the makeshift house nearby, where we spent most of the day discussing the state of mining affairs in Afghanistan as well as the hierarchy of emerald color that was hurting his business. I sat on the carpeted floor in one of the rooms—large enough to host a gathering of a dozen people. Along the corridor, I sighted several bags of powder and wondered out loud what purpose they served. Wahab responded that they were bags of dynamite powder used to break up the rock so they could excavate deeper underground. Wahab, like many others before him, began acquiring explosives during the war and used them for mining gems. His casual explanation opened a window onto the profound effect of war on everyday life and technology. The lack of consistent governance and the threat of violence had prevented the establishment of regulated, large-scale mining operations. Local entrepreneurs and strongmen like Wahab had filled the void, using whatever means available—including repurposed military explosives—to extract gems. “Artisanal” and “primitive” techniques, terms used to describe mining in the Global South more generally, seem inadequate in characterizing hybrid and improvised techniques born of necessity and conflict.

Morris (Reference Morris2008) emphasizes the role of “overhearing”—hearsay and rumors—in South Africa’s diamond and gold rushes. These rushes were sparked by geological information but also by informal hearsay that spread through trade networks. Similar patterns of hearsay also drove rural men, as well as geological explorers and surveyors, to Afghanistan, lured by hopes of mineral discovery and wealth. Speculation propelled the mining futures of these countries, building narratives that both obscured and enabled extraction’s promises. Although prospecting is the first step in all mining, including the extraction of fuel resources, the mining of gems has additional pre-extraction phases—exploration, deposit development, and final exploitation. After discovering a gem-bearing deposit, miners dig a tunnel to reach crystallized formations within rock structures. Separating crystals without damage mandates meticulous extraction processes beyond blasting tunnels through stone. But gem miners in Afghanistan often find themselves at an impasse: blast to explore deeper and risk breaking crystals or stop excavating altogether.

“Most of this [mining] happened in the last thirty-forty years,” Wahab tells me, waving a hand at the open bags of dynamite. “We have never mined so deeply nor learned so much about finding [emerald-bearing] veins.” My host then gestured for me to speak to the others, alternating between Dari, Urdu, and Pashto.Footnote 21 “The world knows about Afghanistan’s mineral wealth,” one remarked. “Sometimes, I think, more than us.” He went on to lament that if they had had the right kind of policies and peace in their country, gems could have made Afghanistan a “developed country” in the way natural resources (manabeh tabyi) have done for others.

Policies and peace are hard to come by, however. Sinding (Reference Sinding2005) explains how attempts to formalize artisanal mining have often failed because they impose rigid regulatory frameworks that do not account for the informal institutions and property rights arrangements that already exist among miners and inhabitants of the area. These informal arrangements, as Peluso (Reference Peluso2018) captures in Indonesia, often involve sophisticated systems of labor organization, revenue sharing, and territorial claims that operate entirely outside state control, with their own internal logics and governance.

The challenges of formalization are complicated by what Hilson and McQuilken (Reference Hilson and McQuilken2014) identify as a persistent disconnection between policy interventions and the actual needs of artisanal miners. While governments have focused on implementing licensing systems and imposing technical requirements, they often fail to recognize that many miners operate informally not by choice but due to poverty and a lack of alternatives. In Panjshir, mining arrangements include complex revenue-sharing agreements between local mine-holders, laborers, and traders. The persistence of informal mining despite formalization speaks to what Peluso (Reference Peluso2018) describes as the emergence of “resource territories” that operate through their own systems of authority, property relations, and knowledge practices, often with the tacit involvement of state actors.

It is perhaps not surprising, given these constraints, that emerald mining in Afghanistan remains an uncertain business. As we sat cross-legged, huddled over hot soup and potatoes in the makeshift mining house, Wahab reflected with regret on his last ten years in mining: “I am far poorer than I used to be.” I later came to know that Wahab’s mining venture had been less than satisfactory, if not outright abysmal. After several years of digging, he had yet to find the kinds of “gem-quality” emeralds that would fetch a high price per carat on the global market. Instead, he had uncovered dozens of kilograms of opaque emerald crystal within each of the veins, which were only good enough to be polished into small cabochons and sold “cheaply” to his buyers in Dubai and Jaipur (Figure 2). The price per carat for emeralds can differ by a factor of a thousand, depending on quality.

Figure 2. Miner’s hands sift through metamorphic rock searching for rare flashes of emerald green crystals (author’s photo).

Wahab’s experience of unrealized value is far from exceptional and exposes the chasm between market projections and mining realities in Afghanistan. Indeed, the geologist Salah was sharply critical of how post-2001 mineral assessments missed this fundamental disconnect. He called the current approach to mining gems “strange,” marked by an obsession with monetary evaluation that obscured the practical realities of extraction. “They saw everything with dollars,” he complained, as resource assessments moved from “mathematical equations” of geological feasibility to “oversimplistic” calculations of market value. Salah was particularly critical of how this dollar-centric evaluation fed into hyperbolic claims that Afghanistan was the “second Saudi Arabia.” I am therefore building on his critique of the reductive practices of developmentalism that are divorced from mining conditions and quality. Predicaments like Wahab’s illustrate precisely the kind of practical realities that Samad argued were overlooked in market-driven evaluations.

Beyond American assessments that viewed the presence of gem deposits primarily through their market value and developmental potential, the reality on the ground is far more complex. The mining sites became contested spaces where state power, traditional rights, and international interests converged—a dynamic clearly illustrated by Wahab’s struggles with market demands and quality standards. This friction calls into question the very notion of “development” and challenges conventional narratives that portray formalization as a clear-cut solution to conflict and poverty.

Conclusion

While geological exploration allows one to map subterranean resources, it rests on the observation and evaluation of potentialities, not actualities, and emerges from the nexus of imperialism, mining practices, and conflict (Weszkalnys Reference Weszkalnys2015). The case of emerald mapping in Afghanistan reveals a deep structural relationship between war, geology, and power—one where geological knowledge production does not merely coincide with conflict but actively contours it (and is contoured by it). In this process, subterranean resources transform into both objects of scientific inquiry and instruments of territorial control, where the very act of mapping what lies below becomes an exercise in projecting and wielding power above.

Afghanistan’s dramatic geological formations have captivated global attention since the early nineteenth century, their allure transcending dispassionate scientific curiosity. Over decades of strife and foreign intervention, mineral wealth has become inseparable from its instability, creating a paradox where resource potential engenders new forms of conflict. What began as ostensibly geologically oriented surveys in the nineteenth century became core instruments of imperial ambition and power. As mining technologies advanced and global mineral demands grew, the mapping of Afghanistan’s subsurface transformed into a contested space where anticipatory resource-making practices intertwined with military strategy and territorial control.

Understanding Afghanistan’s complex resource history requires situating technical appraisals and extraction within broader struggles over territory and livelihood in times of war. Subterranean “discoveries” expose not just two centuries’ worth of contestation over material endowments but also the intersection of science and state power. Drawing on a geological anthropology, I have shown how imperial knowledge production, militarization, and resource potential become mutually reinforcing, creating the cycles of speculation and violence that shape the discourse of El Dorado as a geological imagination and an instrument of territorial control.Footnote 22 Contemporary efforts to leverage mining for profit stem from these longer histories of geological surveys and local governance in crisis.

While mineral wealth exerts an enduring hold on the popular imaginary, the process of obtaining it is fraught with risk and uncertainty. Although Wahab’s miners yielded very little economic value, for him—given the substantive capital he had already invested in mining equipment, labor, and logistics—ending his mining operations would mean losing everything. Wahab’s predicament exemplifies the astonishing volatility of this industry. The possibility of a “big discovery” is what tempts people into mining in the first place—yet for days, weeks, or even months, miners may toil in grueling and dangerous conditions without finding anything at all. Corporate agents, the state, and the press continuously narrate the resource tale, which promises change and development in the region, but the history of geological exploration cannot help but disclose the moral ambiguity of such activities. Paying attention to the choices made by individuals like Wahab helps us fathom the elusiveness of a resource and how its production is inseparable from imperial exploration, geological imaginations, and lives lived in extremis.

Wahab’s case is merely one example of the social ramifications of the structural relationships that pertain between geology, power, and conflict. I have argued that geological imaginaries were not simply imposed on resource frontiers but were co-produced through complex mutual interactions between imperial exploration, scientific practices, and local knowledge systems. Wahab’s story shows how these knowledge-power relations manifest in lived experience, shaping individual lives as much as they do collective social worlds. By tracing how geological knowledge and power reconfigure resource frontiers, we see extraction not as an inevitable source of conflict, but as the ground on which imperial pasts and present struggles converge to determine who benefits from mineral wealth—and at what price.

Acknowledgments

I thank the many colleagues who provided valuable feedback on various iterations of this article, including Joseph S. Alter, Elizabeth Brogden, Purnima Dhavan, Aaron Glasserman, Elisabeth Leake, Mejgan Massoumi, Nida Kirmani, Matthew Schutzer, Claire Sabel, Tara Suri, Tania Saeed, Josh Williams, Jamie Wong, and especially Arunabh Ghosh. Former and current geologists Abdul Samad Salah and Lawrence Snee offered instrumental expertise and insights from their experiences. This work also benefited significantly from discussions at multiple academic forums including MESA, AAA, and the Political Anthropology Writing Group at Harvard. I am indebted to Rameen Habibi and Javed Noorani, who have generously shared their expertise on mining-related matters in Afghanistan throughout these years. I am especially grateful for the attentive and incisive feedback from the anonymous CSSH reviewers and to David Akin for his exceptional editorial guidance.