Introduction

Wheat productivity can be influenced by several factors such as cultivar, nutrient availability, technological level of farming, environmental conditions, and weed interference (Lanzanova et al. Reference Lanzanova, Steinhaus, da Silva, Guerra, de Souza, Pelizzon, Gulart and Bohrer2023; Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Noe, Avent, Butts and Roberts2025; Van Der Meulen and Chauhan Reference Van der Meulen and Chauhan2017). Many weed species show high adaptability and resilience to environmental disturbances caused by human activities or natural events, which often gives them a competitive advantage over crops under certain conditions (Salomão et al. Reference Salomão, Ferro and Ruas2020). Among the weed species that infest wheat, ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) and wild radish (Raphanus raphanistrum L.) stand out as the most difficult to control, mainly due to their resistance to multiple herbicides, which results in significant yield losses (Galon et al. Reference Galon, Basso, Chechi, Pilla, Santin, Bagnara, Franceschetti, Castoldi, Perin and Forte2019; Lamego et al. Reference Lamego, Ruchel, Kaspary, Gallon, Basso and Santi2013; Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Noe, Avent, Butts and Roberts2025; Tavares et al. Reference Tavares, Lemes, Ruchel, Westendorff and Agostinetto2019).

Weeds compete with crops for essential resources such as light, water, and nutrients, and may also release allelopathic substances that negatively affect crop species or serve as hosts for pests that impair crop growth and development (Chu et al. Reference Chu, Zhang, Wang, Gouda, Wei, He and Liu2022; Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Noe, Avent, Butts and Roberts2025; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Zhang, Duan, Lu, Peng, Wang, Pan, Liu and Wang2023). Infestations of wild radish and ryegrass in wheat crops can reduce grain yields by 18% to 82% (Barros and Calado Reference Barros and Calado2020; Galon et al. Reference Galon, Basso, Chechi, Pilla, Santin, Bagnara, Franceschetti, Castoldi, Perin and Forte2019; Lamego et al. Reference Lamego, Ruchel, Kaspary, Gallon, Basso and Santi2013).

Among the main methods used to control weeds in wheat, chemical control via herbicides stands out due to its efficacy, speed, and lower cost compared to other control methods (Balem et al. Reference Balem, Padilha, Michelon and Costa2021; Piasecki et al. Reference Piasecki, Bilibio, Fries, Cechin, Schmitz, Henckes and Gazola2017). However, ryegrass and wild radish populations have developed resistance to key herbicides used on wheat, including inhibitors of acetolactate synthase (ALS), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase), and enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS) (Heap Reference Heap2025). Currently, ACCase and ALS inhibitors are the herbicide groups with the highest incidence of resistant weed biotypes (Heap Reference Heap2025; Salomão et al. Reference Salomão, Ferro and Ruas2020), raising concerns about their continued use for chemical weed control.

Herbicide-resistant weeds pose a major challenge to agriculture due to difficulties in controlling them and the resulting wheat yield losses. This often necessitates the use of tank mixtures of herbicides to achieve effective control or the testing of alternative herbicides. Resistance arises through natural mutation and selection pressure. Natural mutation occurs at a low frequency and may affect the herbicide’s site of action. Selection pressure, however, accelerates resistance development, primarily due to frequent and continuous use of herbicides with the same mode of action without integrating other management strategies such as crop rotation or herbicide rotation (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Noe, Avent, Butts and Roberts2025; Piasecki et al. Reference Piasecki, Bilibio, Fries, Cechin, Schmitz, Henckes and Gazola2017; Walsh Reference Walsh2019).

Tank mixing of herbicides is a common agricultural practice that offers advantages such as reducing the number of applications, minimizing crop trampling, saving time and operational costs, and enhancing the efficacy of applied products, especially when targeting a broader spectrum of pests (Barbieri et al. Reference Barbieri, Young, Dayan, Streibig, Takano, Merotto Junior and Avila2022; de Sousa et al. Reference de Sousa, Côrrea, da Silva, da Silva Cavalcante, Ribeiro and Rodrigues2023; Mechi et al. Reference Mechi, Santos, Ribeiro and Ceccon2018) or weed species. However, successful tank mixing requires thorough knowledge of product compatibility, because some herbicides may interact antagonistically (de Sousa et al. Reference de Sousa, Côrrea, da Silva, da Silva Cavalcante, Ribeiro and Rodrigues2023; Furquim et al. Reference Furquim, Monquero and Silva2019), leading to reduced efficacy or crop injury.

Herbicide mixtures may result in synergistic effects (when combined products perform better than individually), additive effects (when combined efficacy equals the sum of individual effects), or antagonistic effects (when combined efficacy is less than expected) compared to single-product applications (Barbieri et al. Reference Barbieri, Young, Dayan, Streibig, Takano, Merotto Junior and Avila2022; Gazziero Reference Gazziero2015). Given the scarcity of effective herbicides for controlling ryegrass and wild radish in wheat, it is crucially necessary to evaluate new molecules at the research level to generate data that may support the registration of alternative herbicides for use on wheat. This enables assessment of both weed control efficacy and crop selectivity, as well as the potential use of these products for managing resistant weed populations (Piasecki et al. Reference Piasecki, Bilibio, Fries, Cechin, Schmitz, Henckes and Gazola2017; Walsh Reference Walsh2019).

For a herbicide to be recommended for use on a crop, it must be selective; that is, it should control the target weed species while causing minimal or no injury to the crop. This selectivity may result from mechanisms such as differential metabolism between species, positional selectivity, or the use of safeners that protect the crop (Carvalho et al. Reference Carvalho, Ferreira, Figueira and Christoffoleti2009; Colombo et al. Reference Colombo, Albrecht, Albrecht, Araújo and Silva2022), among others. Nonselective herbicides can cause significant negative effects on crop physiology, metabolism, and yield components (Agostinetto et al. Reference Agostinetto, Perboni, Langaro, Gomes, Fraga and Franco2016).They may also interfere with essential physiological processes such as photosynthesis, respiration, and nutrient translocation (Bari et al. Reference Bari, Baloch, Shah, Khakwani, Hussain, Iqbal, Ali and Bukhari2020); and they can disrupt metabolic and biochemical pathways such as amino acid, fatty acid, and chlorophyll synthesis (Tamagno et al. Reference Tamagno, Baldessarini, Sutorillo, Alves, Müller, Kaizer and Galon2022). Finally, they may reduce flower, fruit, and seed formation, directly compromising crop productivity and product quality (Bari et al. Reference Bari, Baloch, Shah, Khakwani, Hussain, Iqbal, Ali and Bukhari2020).

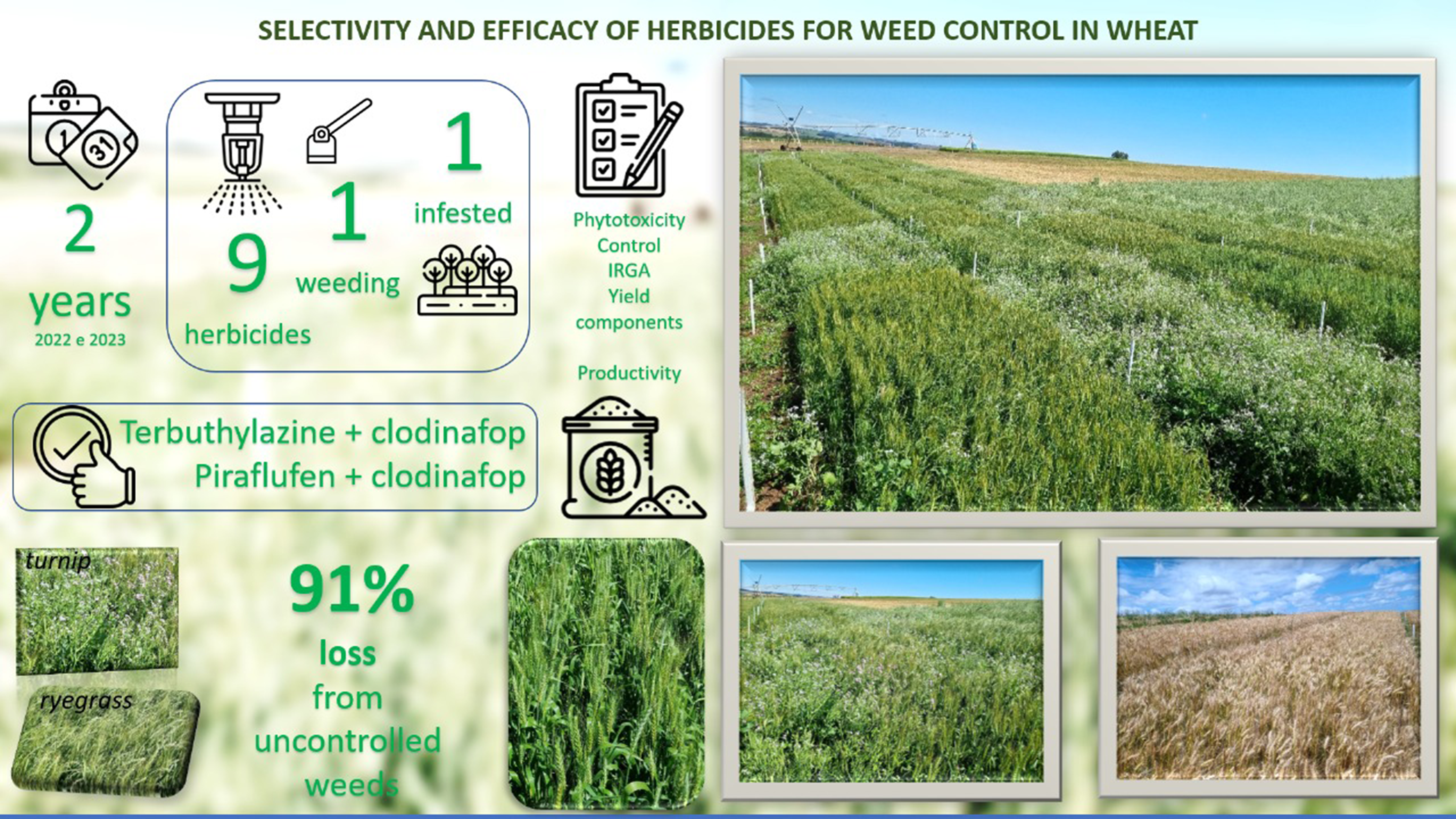

Therefore, further studies are essential to evaluate the selectivity and efficacy of herbicides with diverse modes of action as alternative chemical control options, particularly for managing herbicide-resistant weed species that infest wheat. The hypothesis of this study is that new herbicides, applied alone or in tank mixtures, demonstrate selectivity and efficacy in controlling major weeds in wheat. In this context, the objective was to evaluate the selectivity and efficacy of herbicides applied alone or in combination for controlling weeds in wheat crops.

Materials and Methods

Edaphoclimatic Characteristics, Experimental Design, and Experimental Units

Two field experiments were conducted at the experimental area of the Federal University of Fronteira Sul, Campus Erechim, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (−27.72528° S, −52.29444° W, 650 m), during the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons. In both years, selectivity and efficacy experiments were carried out to evaluate the selectivity of herbicides on wheat and their effectiveness in controlling wild radish and ryegrass, common weeds among wheat crops. In the selectivity experiment, any weed that germinated and emerged within the plots was removed by manual weeding, which was carried out whenever necessary.

The soil of the experimental area is classified as humic alumino ferric latosol (Santos et al. Reference Santos, Jacomine, Anjos, Oliveira, Lumbreras, Coelho, Almeida, Araujo Filhos, Oliveira and Cunha2018), corresponding to the Humic Hapludox (Oxisol according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s soil classification system. Soil pH correction and fertilization were carried out based on soil chemical analysis, following technical recommendations for wheat cultivation (CQFS-RS/SC 2016). The soil’s chemical and physical properties were as follows: pH (H2O) 5.6; organic matter 3.2%; P, 9.7 ppm; K, 134.4 ppm; Al3+, 0.0 meq 100 cm−3; Ca2+, 6.7 meq 100 cm−3; Mg2+, 3.1 meq 100 cm−3; CEC (effective), 10.2 meq 100 cm−3; CEC (pH 7.0), 14.6 meq 100 cm−3; H+ + Al3+, 4.5 meq 100 cm−3; base saturation, 69.50%; clay, 78.30%; sand, 6.25%; and silt, 15.45%.

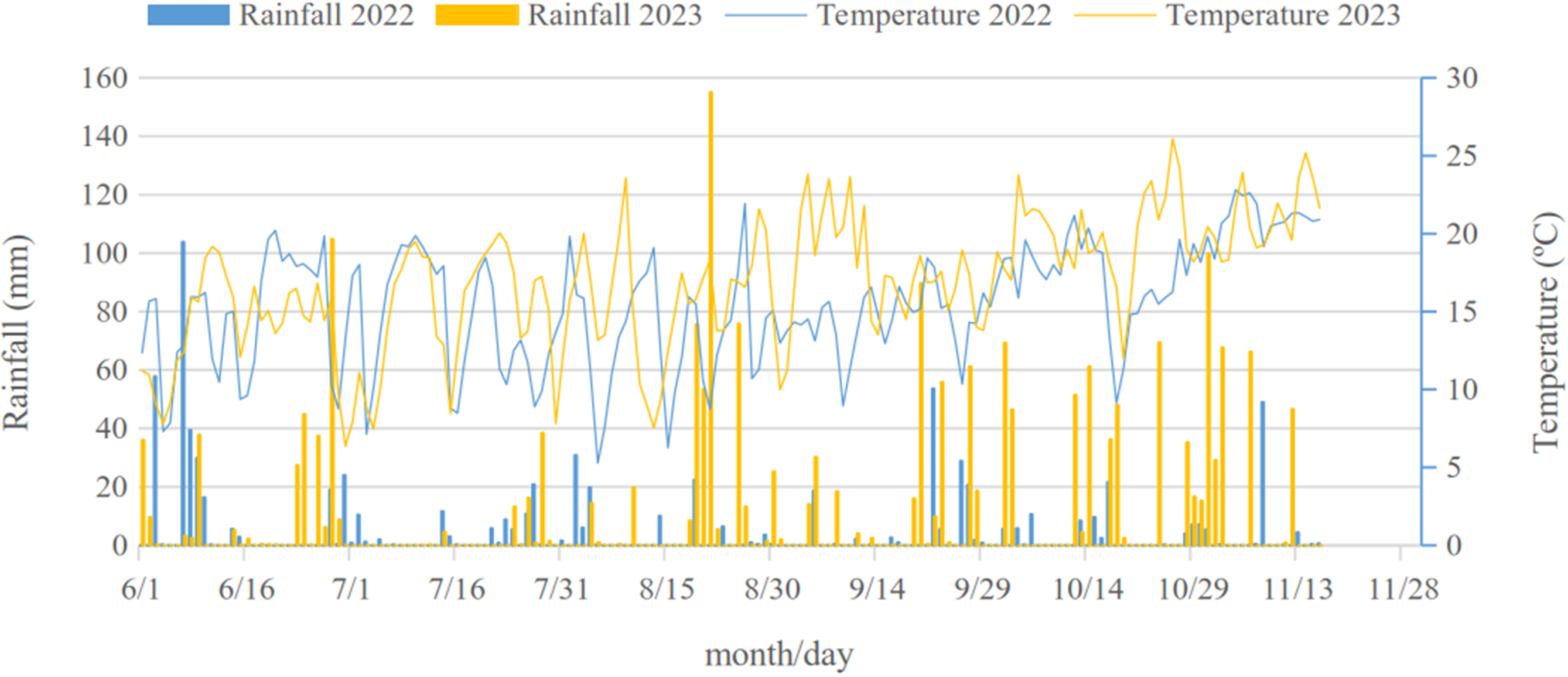

Environmental conditions, including precipitation (in millimeters), mean air temperature (degrees C) and relative humidity (%) during the experiments are shown in Figure 1. The experiments were arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replicates. Each experimental plot measured 5.00 m by 2.72 m, totaling 13.60 m², consisting of 16 rows spaced 0.17 m apart. The useful area for data collection was 6.12 m² (3.00 m by 2.04 m), excluding two border rows on each side and 1 m at both ends of each plot.

Figure 1. Precipitation (mm), mean air temperature (ºC), and relative humidity (%) during the experimental periods from June 2022 to November 2023. Source: INMET (2025).

Sowing, Treatment Application, and Weather Conditions during the Experiments

Wheat was sown on June 20th in both 2022 and 2023 for both selectivity and efficacy trials, using the wheat cultivar TBio Audaz, sown with a tractor-mounted planter/fertilizer at a rate of 85 seeds per meter or 500 seeds m−2. Basal fertilization consisted of 300 kg ha⁻¹ of N-P-K (5-30-15) in 2022, and 200 kg ha⁻¹ in 2023. Nitrogen topdressing was applied at 200 kg ha⁻¹ as urea, split into two applications: the first at tillering and the second at the early stem elongation stage in both years.

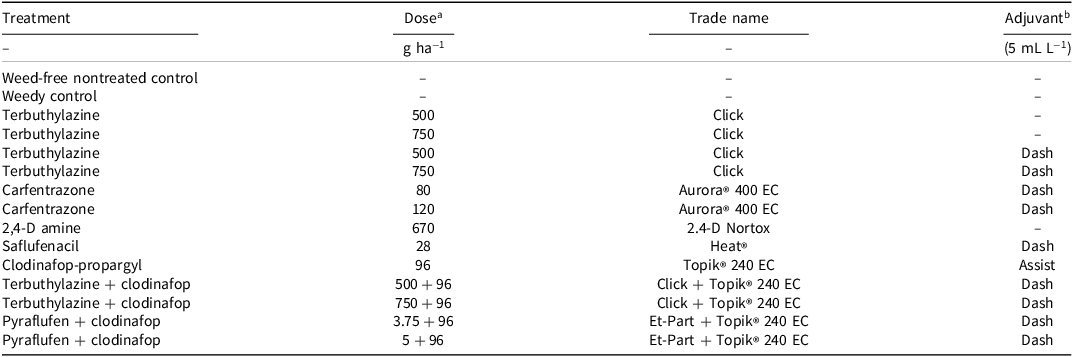

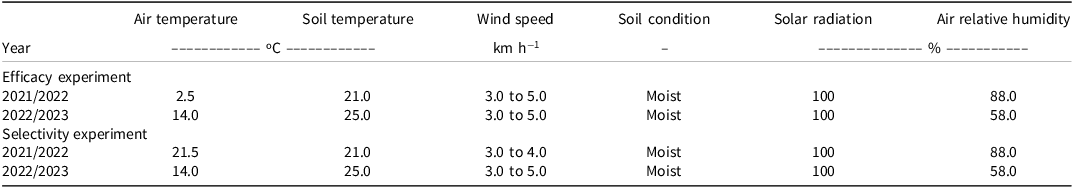

Herbicide treatments were applied with a CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer equipped with four flat-fan nozzles (DG 11002) at a constant pressure of 210 kPa and a walking speed of 3.6 km h⁻¹, delivering a spray volume of 150 L ha⁻¹. The treatments applied in the experiments are detailed in Table 1. Environmental conditions during postemergence herbicide applications (July 20, 2022, and July 17, 2023) are presented in Table 2.

Table 1. Herbicide treatments applied in postemergence selectivity and efficacy experiments with the wheat cultivar TBio Audaz in 2022 and 2023 growing seasons.

a Dose is presented in g ai or ae ha−1 depending on formulation.

b Dash (BASF, São Paulo, Brazil) is an agricultural adjuvant with adhesive, spreading, and penetrating properties, composed of methyl esters of vegetable oil (37.5 g kg). Assist (BASF) is a nonionic adjuvant composed of mineral oil derived from petroleum (78.2 g kg-1).

c Click (OXON, São Paulo/SP, Brazil) is a herbicide used to control weeds infesting corn and sorghum, containing the active ingredient terbuthylazine (500 g L-1).

d Aurora® 400 EC (FMC, Campinas/SP, Brazil) is a herbicide used to control weeds infesting various agricultural crops, containing the active ingredient carfentrazone (400 g L-1).

e 2,4-D Nortox (NORTOX S/A, Arapongas/PR, Brazil) is a herbicide used to control weeds infesting various agricultural crops, containing the active ingredient 2,4-D (670 g L-1).

f Heat (BASF, São Paulo/SP, Brazil) is a herbicide used for desiccation of vegetation and seeds and grains, as well as post-emergence weeding of various crops, containing the active ingredient saflufenacil (700 g kg-1).

g Topik® 240 EC (Syngenta, São Paulo/SP, Brazil) is a herbicide used for the control of weeds infesting wheat and soybeans in post-emergence of crops, containing the active ingredient clodinafop-propargyl (240 g L-1).

h Et-Part (NICHINO, Barueri/SP, Brazil) is a defoliant herbicide used in potato, bean, and cotton crops, containing the active ingredient piraflufen-ethyl (25 g L-1).

Table 2. Weather conditions at the time of herbicide application in wheat selectivity and efficacy experiments in 2022 and 2023 growing seasons.

Growth Stages, Plant Density, and Evaluated Variables

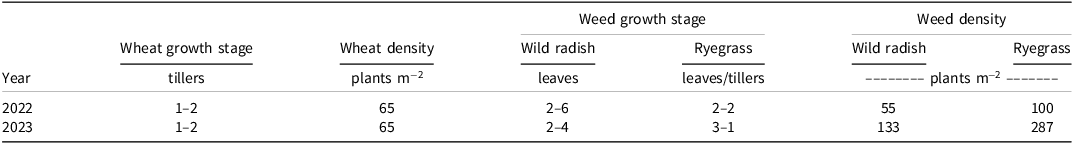

The growth stages of wheat and weeds, as well as their densities at the time of herbicide application, are shown in Table 3. The density of weed plants present in the experiment originated from the soil seed bank and was measured at the center of the infested control plots at the time of herbicide application, using a quadrat made with polyvinyl chloride pipes with dimensions of 0.5 by 0.5 m (0.25 m²). The following variables were evaluated: crop phytotoxicity, physiological parameters, weed control (wild radish and ryegrass), number of spikes per square meter, spike length (in centimeters), number of filled and sterile grains per spike, thousand-grain weight (in grams), hectoliter weight (in kilograms per cubic meter, kg m−3), and grain yield (in kilograms per hectare, kg ha⁻¹).

Table 3. Wheat growth stage, and plant densities of wheat and weeds at the time of herbicide application in selectivity and efficacy experiments.

Phytotoxicity and weed control were visually assessed by two independent evaluators (scores from both evaluators were later averaged to a single score prior to statistical analysis), at 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 d after treatment (DAT) using a percentage scale in which 0% represented no injury or no control and 100% represented complete plant death (Velini et al. Reference Velini, Osipe and Gazziero1995). The symptoms evaluated as expressions of herbicide phytotoxicity on wheat included reduced plant height, decreased tiller number, delayed canopy closure between rows, chlorosis, necrosis, leaf purpling or yellowing, leaf epinasty, stem curvature, shortened internodes, and leaf rolling.

At 21 DAT, physiological parameters were measured, including intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci, µmol mol⁻¹), stomatal conductance (g s, mol m⁻² s⁻¹), transpiration rate (E, mol H2O m⁻² s⁻¹), and photosynthetic rate (A, µmol m⁻² s⁻¹). Water use efficiency (WUE = A/E) and carboxylation efficiency (CE = A/Ci) were subsequently calculated. Gas exchange was measured in two plants per experimental unit, on the last fully expanded leaf of each wheat plant, using an infrared gas analyzer. Choosing an evaluation time of 21 DAT for determining physiological variables was based on previous studies conducted by the research group, in which multiple assessments were performed at various stages after herbicide application. These studies concluded that 21 DAT is the most appropriate time to determine the effects of the herbicides on the gas exchange of wheat plants. To do this we used the high-precision infrared gas analysis feature housed within an automated photosynthesis analyzer system (ADC Bioscientific, Hoddesdon, Herts, UK) between 8:00 and 11:00 AM under stable environmental conditions.

Prior to harvest, the number of spikes per square meter, spike length (in centimeters), and the number of filled and sterile grains per spike were recorded. Spike counts were performed within a 0.25-m² quadrat (0.5 by 0.5 m) placed at the center of each plot. Ten spikes per plot were randomly collected for grain counts and spike measurements using a graduated ruler.

After manual harvesting and threshing of the 6.12-m² plot area, hectoliter weight (in kilograms per cubic meter, kg m−3), thousand-grain weight (in grams), and grain yield (in kilograms per hectare, kg ha⁻¹) were determined. Hectoliter weight was measured using a Dalle Molle balance, model 40. Thousand-grain weight was determined by weighing eight samples of 100 grains each. Grain yield was extrapolated to kg ha⁻¹, adjusted to 13% moisture.

Data Analysis

To assess the consistency of the results over time, the experiment was repeated in two consecutive years (2022 and 2023) using the same experimental design, treatments, and methodological procedures. Prior to the combined data analysis, tests for normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variances (Hartley test) were conducted. These indicated no significant heterogeneity between years. Given the homogeneity of variances, a combined statistical analysis of the 2-yr data set was performed to increase statistical power and provide a more robust interpretation of the treatment effects across different seasonal environments. When assumptions were met, the data were analyzed using ANOVA (F-test), and treatment means were compared using the Scott–Knott test at a significance level of P ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Sisvar software version 5.6 (Ferreira Reference Ferreira2011).

Results and Discussion

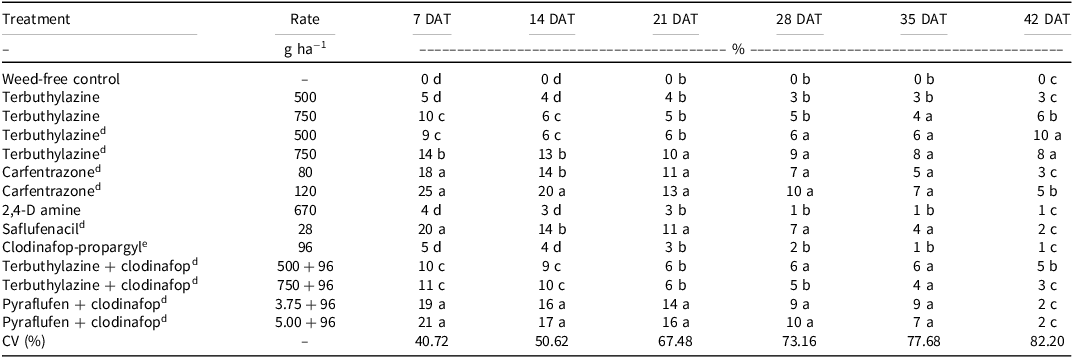

Selectivity of Herbicides Applied to the Wheat Cultivar TBio Audaz

From 7 to 35 DAT, herbicides that caused the greatest phytotoxicity to the wheat cultivar TBio Audaz included terbuthylazine (750 g ha⁻¹) + Dash (BASF, São Paulo, Brazil) (5 mL L−1), carfentrazone (80 and 120 g ha⁻¹), saflufenacil (28 g ha⁻¹), and the tank mixture of pyraflufen (3.75 and 5 g ha⁻¹) + clodinafop-propargyl (96 g ha⁻¹) (Table 4). At 42 DAT, applications of terbuthylazine (500 and 750 g ha⁻¹) combined with Dash (5 mL L−1) resulted in the greatest phytotoxicity to wheat (7.5% to 10%) compared to the other treatments (6.3% or less).

Table 4. Phytotoxicity of herbicides applied postemergence to the wheat cultivar TBio Audaz during the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons. a b c d

a Abbreviation: CV, coefficient of variation; DAT, days after treatment.

b Doses are listed in g ai or ae ha−1 depending on formulation.

c Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ statistically by the Scott-Knott test at α ≤ 0.05.

d,e The adjuvants Dash and Assist, respectively, were added at 5 mL L−1.

The phytotoxicity caused by these herbicides may be due to the plant’s inability to metabolize the compounds or to physicochemical factors related to the herbicide molecules themselves, such as the chemical structure, dosage, and timing of application (Correia and Carvalho Reference Correia and Carvalho2021; Powles and Yu Reference Powles and Yu2010; Raj et al. Reference Raj, Kumar and Singh2020).

The results demonstrate that applications of terbuthylazine (500 g ha⁻¹) without any adjuvant, 2,4-D, and clodinafop-propargyl resulted in the fewest phytotoxicity symptoms in wheat from 7 to 42 DAT, being statistically similar to the nontreated weed-free controls in all evaluations (Table 4). Other treatments resulted in intermediate phytotoxicity levels, ranging between those that caused the greatest and least injuries. Similarly, Agostinetto et al. (Reference Agostinetto, Perboni, Langaro, Gomes, Fraga and Franco2016) reported a reduction in phytotoxicity symptoms over time following the application of 2,4-D and other herbicides to wheat crops. Consistent results were also reported by Galon et al. (Reference Galon, Ulkovski, Rossetto, Cavaletti, Weirich, Brandler, Silva and Perin2021), who observed phytotoxicity levels of less than 8% for clodinafop-propargyl, which is considered low and comparable to those observed in the present study.

Although some treatments initially caused high levels of phytotoxicity, particularly at the first two evaluations (7 and 14 DAT), these symptoms did not evolute as the crop matured, reaching values of less than 10% at 42 DAT (Table 4). The crop was thus able to overcome the initial herbicide damages. This reduction suggests that the wheat plants were able to recover from the initial herbicide injury as growth progressed. According to Elattar et al. (Reference Elattar, Dahroug, El-Sayed and Hashiesh2018), phytotoxicity levels between 12.5% and 15% in wheat are considered mild, and allow the crop to recover. This finding highlights the physiological capacity of wheat to metabolize and overcome the toxic effects of herbicides over time (Piasecki et al. Reference Piasecki, Bilibio, Fries, Cechin, Schmitz, Henckes and Gazola2017).

The progressive reduction in phytotoxicity symptoms can be attributed to the plant’s detoxification mechanisms. Tolerant cultivars such as TBio Audaz are capable of metabolizing herbicides through the action of enzymes such as cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (P450) and glutathione S-transferase (GST). P450 enzymes catalyze oxidation reactions of herbicide molecules, whereas GSTs conjugate herbicides with glutathione, facilitating their detoxification (Carvalho-Moore et al. Reference Carvalho-Moore, Norsworthy, Avent and Riechers2024; Devine et al. Reference Devine, Duke and Fedtke1993). These biochemical processes are directly associated with herbicide selectivity and crop tolerance. According to Powles and Yu (Reference Powles and Yu2010), this type of metabolic resistance is one of the main adaptive strategies in grasses, explaining the crop’s ability to recover even after exhibiting initial injury symptoms. In both wheat and barley, some herbicides are metabolized through accelerated hydroxylation, glucose conjugation, and limited or differential absorption and translocation via the phloem and xylem. These processes, combined with the metabolic efficiency of P450 enzymes, detoxification pathways, and differential plant sensitivity, contribute to reduced phytotoxicity over time (Carvalho-Moore et al. Reference Carvalho-Moore, Norsworthy, Avent and Riechers2024; Mithila et al. Reference Mithila, Hall, Johnson, Kelley and Riechers2011; Piasecki et al. Reference Piasecki, Bilibio, Fries, Cechin, Schmitz, Henckes and Gazola2017). International studies report that adding the safener cloquintocet-mexyl to pinoxaden improves selectivity in wheat and barley (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Cummins, Brazier-Hicks and Edwards2013); however, in Brazil, this is not recommended for clodinafop-propargyl. Results might differ with this safener, but its use still lacks registration and technical approval by Anvisa, Brazil’s health regulatory agency.

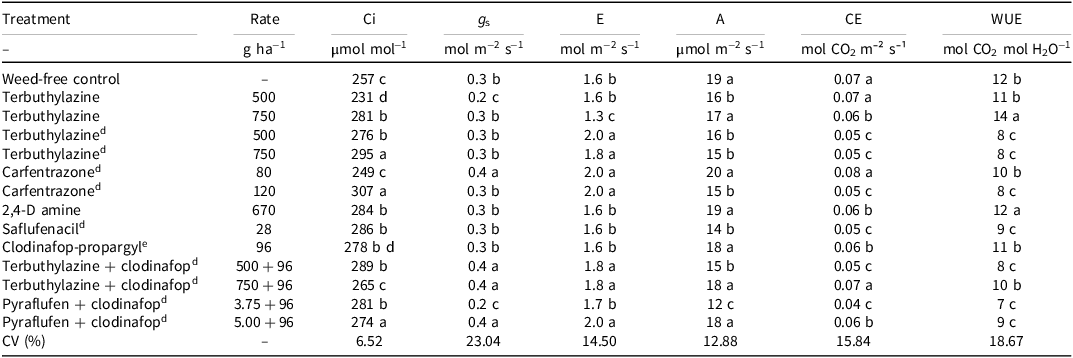

At 21 DAT, evaluation of the physiological responses of wheat to herbicide application showed that the nontreated weed-free control and plots that had been treated with terbuthylazine (500 and 750 g ha−1), carfentrazone (80 g ha−1), 2,4-D, and terbuthylazine + clodinafop (750 + 96 g ha−1) generally exhibited the best physiological profiles (Table 5). The phytotoxicity observed in the mixture, but not in the individually applied treatments, is most probably due to a reduced detoxification capacity and combined oxidative stress, caused by each herbicide individually, at the same time. In other words, the plant becomes unable to neutralize both herbicides simultaneously at the same rate as it does when each herbicide is applied alone (Carvalho et al. Reference Carvalho, Ferreira, Figueira and Christoffoleti2009; Silva et al. Reference Silva, Oliveira, Carneiro, Souza, Ferreira, Simoes, Machado and Pinho2024; Zanatta et al. Reference Zanatta, Mandredi-Coimbra, Procópio, Manica, Sganzerla and Carneiro2007). For these treatments, the photosynthetic rate tended to be higher, compared to the other treatments, where it tended to be affected by the herbicides. This reduction is associated with the oxidative stress induced by herbicide action (Agostinetto et al. Reference Agostinetto, Perboni, Langaro, Gomes, Fraga and Franco2016); there is a direct relationship between herbicide toxicity and reduced photosynthetic rates, as CO2 fixation decreases, crop development and productivity are negatively affected (Su et al. Reference Su, Sun, Ge, Wu, Lu and Lu2018).

Table 5. Internal CO2 concentration, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, photosynthetic rate, carboxylation efficiency, and water use efficiency in the wheat cultivar TBio Audaz as affected by herbicide applications in the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons. a b c

a Abbreviations: A, photosynthetic rate; CE, carboxylation efficiency; Ci, internal CO2 concentration; CV, coefficient of variation; DAT, days after treatment; E, transpiration rate; g S, stomatal conductance; WUE, water use efficiency.

b Doses are listed in g ai or ae ha−1 depending on formulation.

c Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ statistically by the Scott-Knott test at α ≤ 0.05.

d,e The adjuvants Dash and Assist, respectively, were added at 5 mL L−1.

According to Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Zheng, Shen and Guo2013), the dynamics of stomatal opening and closing strongly influence stomatal conductance (g s), which is a key parameter in regulating transpiration rates. When stomata are open, g s increases, leading to higher transpiration rates and enhanced heat dissipation via water evaporation. Conversely, stomatal closure reduces g s, limiting transpiration and water consumption. This response is commonly associated with environmental stress or herbicide-induced stress. Stomatal regulation is one of the plant’s primary responses to stress, aimed at reducing water loss through transpiration. However, this mechanism also leads to a simultaneous reduction in CO2 assimilation, which directly affects photosynthetic rates and plant growth (Cruz et al. Reference Cruz, Porto, Ramos, Santos, Seixas and Santos2023).

In addition to stomatal conductance (g s), the internal CO2 concentration (Ci) was higher in treatments that exhibited lower photosynthetic rates (A), such as those treated with terbuthylazine + Dash or pyraflufen + clodinafop. This suggests a limitation in the use of the assimilated CO2, likely indicating a biochemical inefficiency in carbon fixation, probably associated with herbicide-induced interference in Calvin cycle enzymes (Devine et al. Reference Devine, Duke and Fedtke1993). On the other hand, herbicides that produce higher photosynthetic rates, such as carfentrazone (80 g ha⁻¹) and 2,4-D, demonstrated lower Ci values.

Photosynthetic rate (A) was reduced in treatments that presented higher visual phytotoxicity, following the same pattern observed for carboxylation efficiency (CE). This limitation may be associated with both the direct toxicity of the products and secondary effects, such as the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, which compromise chloroplast integrity (Powles and Yu Reference Powles and Yu2010).

Water use efficiency (WUE) was also negatively affected in several treatments, especially those that caused increased transpiration rates (E) without proportional gains in photosynthesis (A), such as pyraflufen + clodinafop. This indicates a less physiologically efficient use of the available water. In contrast, herbicides that cause lower phytotoxicity and stable photosynthetic performance, such as 2,4-D and terbuthylazine (500 g ha⁻¹), maintained WUE values comparable to the weed-free control.

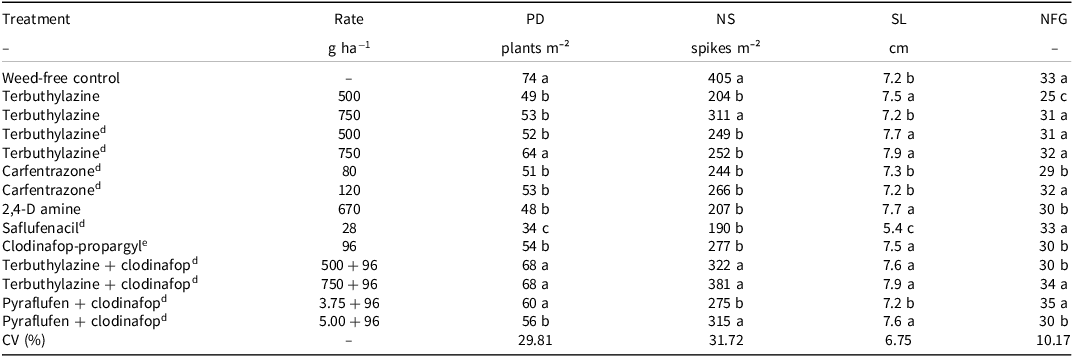

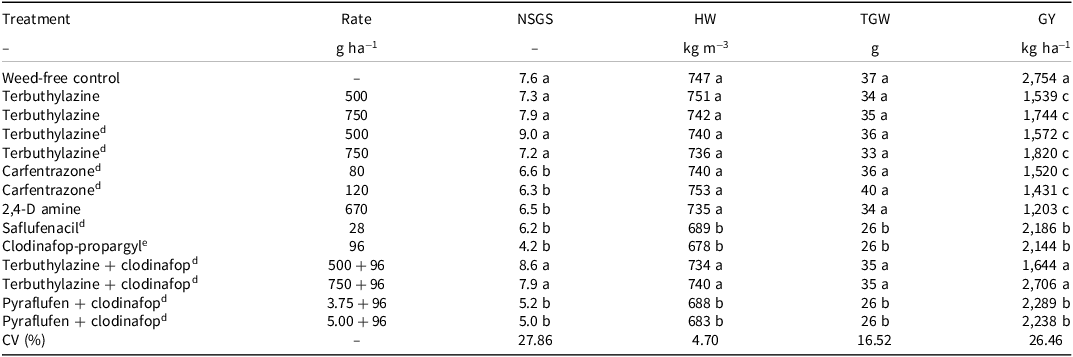

Regarding all wheat yield components, including plant density (plants m⁻¹), number of spikes (spikes m⁻²), spike length (in centimeters), number of filled and sterile grains per spike, hectoliter weight (kg hL⁻¹), thousand-grain weight (g), and grain yield (kg ha⁻¹), the weed-free control and the terbuthylazine + clodinafop treatment (750 + 96 g ha⁻¹) stood out with the best performance compared to the other treatments (Tables 6 and 7). This result was due to the crop’s ability to recover from herbicide-induced injuries without negatively affecting growth, development, or grain yield components.

Table 6. Plant density, number of spikes, spike length, and number of filled grains per spike in plants of wheat cultivar TBio Audaz BRS as affected by herbicide applications in the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons. a b c

a Abbreviations: CV, coefficient of variation; DAT, days after treatment; NFG, number of filled grains; NS, number of spikes; PD, plant density; SL, spike length.

b Doses are listed in g ai or ae ha−1 depending on formulation.

c Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ statistically by the Scott-Knott test at α ≤ 0.05.

d,e The adjuvants Dash and Assist, respectively, were added at 5 mL L−1.

Table 7. Number of sterile grains per spike, hectoliter weight, thousand-grain weight, and grain yield in wheat cultivar TBio Audaz as affected by herbicide applications in the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons. a b c

a Abbreviations: CV, coefficient of variation; DAT, days after treatment; GY, grain yield; HW, hectoliter weight; NSGS, number of sterile grains per spike; TGW, thousand-grain weight.

b Doses are listed in g ai or ae ha−1 depending on formulation.

c Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ statistically by the Scott-Knott test at α ≤ 0.05.

d,e The adjuvants Dash and Assist, respectively, were added at 5 mL L−1.

When plants experience phytotoxicity, they activate defense mechanisms that require greater energy expenditure to metabolize the herbicide, leading to the emission of new leaves that are free from injury symptoms (Agostinetto et al. Reference Agostinetto, Perboni, Langaro, Gomes, Fraga and Franco2016; Raj et al. Reference Raj, Kumar and Singh2020; Tamagno et al. Reference Tamagno, Baldessarini, Sutorillo, Alves, Müller, Kaizer and Galon2022).

Several authors have reported that wheat yield components can be either positively or negatively influenced by herbicide applications. These effects depend primarily on the genetic characteristics of the cultivar, and the herbicide properties (application method, mode of action, dosage, formulation, and mixtures), as well as soil and environmental conditions (Bari et al. Reference Bari, Baloch, Shah, Khakwani, Hussain, Iqbal, Ali and Bukhari2020; Carvalho et al. Reference Carvalho, Ferreira, Figueira and Christoffoleti2009; Zakariyya et al. Reference Zakariyya, Awan, Khan, Baloch and Khakwani2022).

The thousand-grain weight (TGW) did not significantly vary with most herbicide applications to wheat, with the highest TGW recorded in weed-free control plants (Table 7). Saflufenacil and clodinafop-propargyl, applied alone or in combination with both doses of pyraflufen, resulted in the lowest TGW compared to all other treatments in wheat. Differences in herbicide selectivity can depend on soil and climate conditions, crop growth stage, dose, mode of action, product combinations, or interactions among these factors. Rapid degradation and metabolism of these molecules in wheat generally reduce crop damage (Colombo et al. Reference Colombo, Albrecht, Albrecht, Araújo and Silva2022). However, at advanced growth stages or under adverse conditions, this detoxification capacity may be impaired, and crop injury can occur even with selective herbicides.

Similar results have been previously reported in the Gomal-8 wheat cultivar after various herbicides were applied (Bari et al. Reference Bari, Baloch, Shah, Khakwani, Hussain, Iqbal, Ali and Bukhari2020), in the TBio Toruk and TBio Audaz wheat cultivars after an application of clodinafop (Balem et al. Reference Balem, Padilha, Michelon and Costa2021), and in the CD 1303 cultivar when clodinafop-propargyl, saflufenacil, and 2,4-D were applied (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Albrecht, Albrecht, Araújo and Silva2022). Frihauf et al. (Reference Frihauf, Stahlman and Al-Khatib2010) reported wheat grain yield losses of up to 58% when saflufenacil was applied to control infesting weeds, which is similar to the findings of the present study with the same product, although at a lower percentage of damage. Carvalho et al. (Reference Carvalho, Ferreira, Figueira and Christoffoleti2009) noted that when an enzyme or enzymatic complex cannot metabolize or degrade a herbicide within the plant, injury occurs, leading to grain yield losses. This aligns with our observation of reduced TGW and grain yield after treatments when herbicides were insufficiently metabolized, thus lacking selectivity to the crop.

Although some treatments had positive effects on certain grain yield components, they consistently resulted in lower wheat grain yield, with reductions of 35.46% and 34.32% compared with the weed-free control and terbuthylazine + clodinafop (750 + 96 g ha−1) treatments to the average when the other products used (Table 7). The high yield observed in the weed-free control and terbuthylazine + clodinafop (750 + 96 g ha−1) treatments is likely related to the low phytotoxicity these herbicides caused to wheat, thereby improving weed control (of both dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species), which allowed the crop to express its full productive potential. When selectivity and adequate weed control are achieved, the productive potential and grain quality of a wheat cultivar can be maintained (Saif and Bashar Reference Saif and Bashar2024). In our experiment, wheat was free from weed competition through manual weeding carried out whenever necessary, which resulted in better TGW and grain yield. Several studies of herbicides applied to wheat have reported that weed-free, manually weeded controls that are free from competition demonstrated superior grain yield (Bari et al. Reference Bari, Baloch, Shah, Khakwani, Hussain, Iqbal, Ali and Bukhari2020; Colombo et al. Reference Colombo, Albrecht, Albrecht, Araújo and Silva2022; Viecelli et al. Reference Viecelli, Pagnoncelli, Trezzi, Cavalheiro and Gobetti2019).

It is also noteworthy that applications of saflufenacil, clodinafop, or pyraflufen (3.75 and 5.00 g ha−1) mixed in the spray tank with clodinafop-propargyl (5.0 + 96 g ha−1) resulted in the lowest hectoliter weight, averaging less than 690 kg m−3 (Table 7). Herbicides applied in tank mixtures can interact chemically or biologically within the plant, causing additional stress that may reduce grain filling capacity and consequently grain weight and quality. Furthermore, herbicide effects can vary with environmental conditions (temperature and humidity), soil characteristics (moisture, texture, pH, fertility), application timing, cultivar, crop management, and the physicochemical properties of the products and their mixtures, as well as interactions among these factors (Carvalho et al. Reference Carvalho, Ferreira, Figueira and Christoffoleti2009; Gandini et al. Reference Gandini, Costa, Santos, Soares, Barroso, Corrêa, Carvalho and Zanuncio2020; Matzenbacher et al. Reference Matzenbacher, Kalsing, Dalazen, Markus and Merotto Junior2015; Nandula et al. Reference Nandula, Riechers, Ferhatoglu, Barrett, Duke, Dayan, Goldberg-Cavalleri, Tétard-Jones, Onkokesung, Brazier-Hicks, Edwards, Gaines, Iwakami, Jugulam and Ma2019).

Hectoliter weight is an important parameter related to wheat classification and commercialization, as higher values correspond to better flour yield for baking purposes (Ormond et al. Reference Ormond, Nunes, Caneppele, Silva and Pereira2013). According to Nunes et al. (Reference Nunes, Souza, Vitorino and Mota2011), hectoliter weight is directly influenced by grain shape, density, uniformity, size, broken grains, and foreign material content. For wheat classification and commercialization, following Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture Normative Instruction No. 7 (August 15, 2001) (BRASIL 2001), wheat grains are classified into three types based on minimum hectoliter weight values: Type 1 (≥780 kg m−3), Type 2 (≥750 kg m−3), and Type 3 (≥700 kg m−3). None of the treatments in this study reached Type 1 classification (hectoliter weight > 780 kg m−3). Thus, the treatments involving saflufenacil, clodinafop-propargyl, and pyraflufen + clodinafop (3.75 + 96 and 5 + 96 g ha⁻¹) resulted in hectoliter weight below the minimum required (≤700 kg m⁻³) by Brazilian legislation, making the grain unsuitable for flour production for bread and suitable only for other purposes.

As previously discussed, the negative effects caused by saflufenacil and clodinafop-propargyl, applied alone or in combination with pyraflufen, are related to differences in herbicide selectivity, climatic factors, crop growth stage, dose, site or mode of action, and interactions among these factors. For example, wheat absorbed 2.8 to 3.5 times more saflufenacil when applied in combination with 2,4-D amine compared to saflufenacil applied alone (Frihauf et al. Reference Frihauf, Stahlman and Al-Khatib2010). The same authors reported that mixing saflufenacil with bentazon results in 10% absorption, whereas saflufenacil alone is absorbed at 16%. This demonstrates that the application method—alone or in combination—and the choice of mixing partners influence the percentage of herbicide absorbed by the crop. The low hectoliter weight values observed in our experiment are mainly attributed to the high precipitation occurring near the wheat harvest, as shown in Figure 1. Vargas et al. (Reference Vargas, Mühl, Feldmann, Cassol and Somavilla2023) reported that heavy rain close to harvest negatively affected wheat hectoliter weight.

Efficacy of Herbicides for Control of Wild Radish and Ryegrass

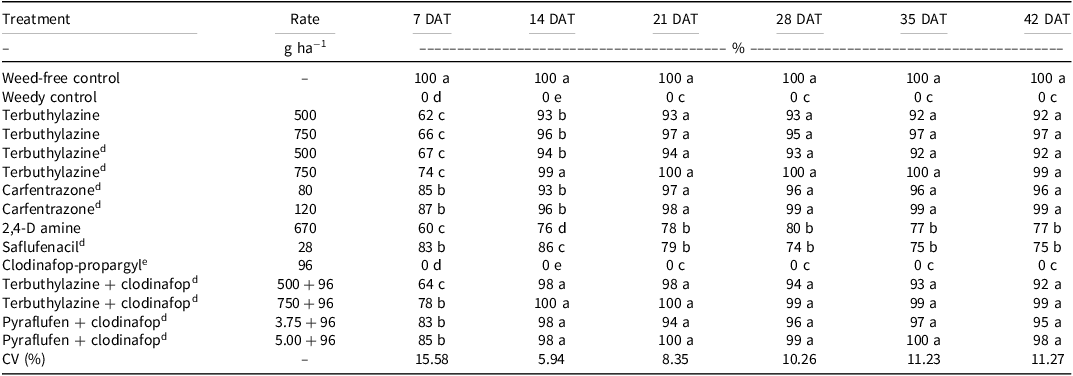

The results show that clodinafop-propargyl provided significantly lower control of wild radish compared to all other treatments, especially from 14 to 42 DAT, when the most effective products achieved control rates of >93% (Table 8). This is due to wild radish possessing an enzyme that is insensitive to clodinafop-propargyl, rendering this herbicide selective for this weed and underscoring that the herbicides is primarily recommended for controlling grass species such as ryegrass (Trezzi et al. Reference Trezzi, Mattei, Vidal, Kruse, Gustman, Viola, Machado and Silva2007).

Table 8. Control of wild radish (Raphanus raphanistrum) infesting wheat cultivar TBio Audaz as affected by herbicide applications in 2022 and 2023. a b c

a Abbreviations: CV, coefficient of variation; DAT, days after treatment.

b Doses are listed in g ai or ae ha−1 depending on formulation.

c Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ statistically by the Scott-Knott test at α ≤ 0.05.

d,e The adjuvants Dash and Assist, respectively, were added at 5 mL L−1.

At 7 DAT, herbicide symptoms were likely not yet fully expressed, making it difficult to visually assess effective control of wild radish (Table 8). In this first evaluation, carfentrazone (80 and 120 g ha−1), saflufenacil and pyraflufen (3.75 and 5.00 g ha−1) stood out as providing the best wild radish control with control rates exceeding 82% compared to other herbicide treatments. This is mainly because these herbicides are contact protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PROTOX) inhibitors, showing effects shortly after application. They act on the PROTOX enzyme in chloroplasts, which oxidizes protoporphyrinogen to protoporphyrin IX, a precursor of chlorophyll and heme groups, or interfere with electron transfer. PROTOX inhibition leads to protoporphyrinogen accumulation, which when exposed to oxygen, forms protoporphyrin IX, which upon exposure to light, generates reactive oxygen species that damage and degrade cellular membranes, ultimately causing necrosis and plant death (Barker et al. Reference Barker, Geva, Simonovsky, Shemesh, Phillip, Shub and Dayan2023).

Schmitz et al. (Reference Schmitz, Tomazetti, Piasecki, Henkes, Garcia, Tessaro and Fialho2016) reported that saflufenacil controlled wild radish by more than 90% from 14 DAT, which partially corroborates our results. In Brazil, a minimum herbicide efficacy of 80% is required for it to be recommended for use against weeds (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Freitas and Vieira2009). Clodinafop-propargyl had no effect on wild radish because this dicotyledon species is naturally insensitive to ACCase inhibitors. Graminicides, such as clodinafop-propargyl, effectively control many annual and perennial grasses in dicot crops (soybean, cotton, common bean, etc.) (Petter et al. Reference Petter, Pereira, Silva and Morais2016). These herbicides are recommended for use on wheat crops due to wheat’s high selectivity, which results from rapid herbicide metabolism (Trezzi et al. Reference Trezzi, Mattei, Vidal, Kruse, Gustman, Viola, Machado and Silva2007).

The results from these studies demonstrate that terbuthylazine (750 g ha−1) + adjuvant, terbuthylazine (500 and 750 g ha−1) combined with clodinafop-propargyl + adjuvant, and pyraflufen (3.75 and 5 g ha−1) mixed with clodinafop-propargyl + adjuvant provided wild radish control that was statistically equal to the weed-free control from 14 to 42 DAT (Table 8). From 21 DAT onward, terbuthylazine (500 and 750 g ha−1), terbuthylazine (500 g ha−1) + adjuvant, and carfentrazone (80 and 120 g ha−1) achieved wild radish control greater than 92%, matching the weed-free control up to 42 DAT. Although terbuthylazine and pyraflufen have not yet registered for use on wheat in Brazil, they may serve as alternatives for controlling dicotyledonous weeds, especially wild radish, which is resistant to ALS inhibitors in Brazil (Costa and Rizzardi Reference Costa and Rizzardi2015) and Argentina (Pandolfo et al. Reference Pandolfo, Presotto, Poverene and Cantamutto2013). Other treatments were only superior to or similar to the weedy control during the evaluation period.

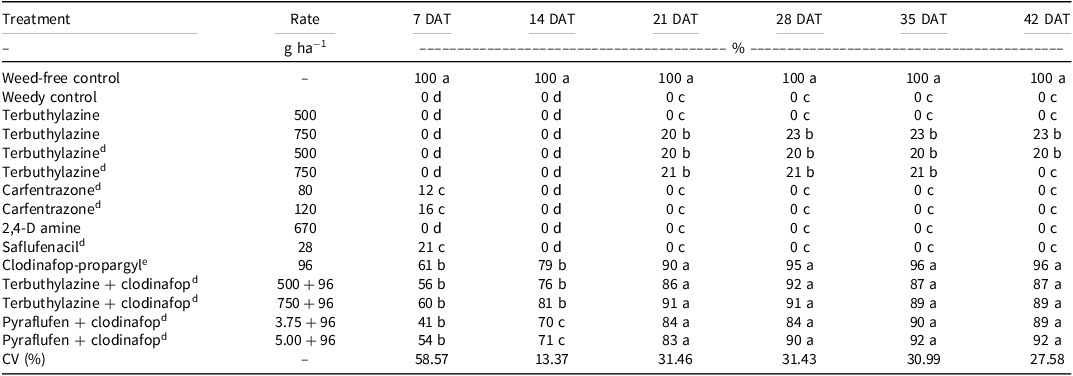

The greatest levels of ryegrass control were achieved with clodinafop-propargyl (96 g ha−1) applied alone and in tank mixtures with terbuthylazine (500 and 750 g ha−1) or pyraflufen (3.75 and 5 g ha−1) from 7 to 42 DAT (Table 9). These treatments provided ryegrass control that was statistically equal to the weed-free control from 21 DAT onward, maintaining it through 42 DAT.

Table 9. Control of ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum) infesting the wheat cultivar TBio Audaz as affected by herbicide applications in the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons. a b c

a Abbreviations: CV, coefficient of variation; DAT, days after treatment.

b Doses are listed in g ai or ae ha−1 depending on formulation.

c Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ statistically by the Scott-Knott test at α ≤ 0.05.

d,e The adjuvants Dash and Assist, respectively, were added at 5 mL L−1.

Ryegrass control during the first two evaluations (7 and 14, DAT) was observed to be less than 80% at 14 DAT, except the plots that received applications of terbuthylazine + clodinafop (750 + 96 g ha−1), which achieved 81.25% control (Table 9). Treatments such as terbuthylazine, 2,4-D amine, and saflufenacil applied alone demonstrated control levels that were similar to those of the weedy control at 14 DAT. All these were well below the minimum threshold required for herbicide recommendation because these herbicides are selective for grasses and used primarily to control dicotyledonous weeds (AGROFIT 2025; Mariani et al. Reference Mariani, Vargas, Agostinetto, Nohatto, Langaro and Duarte2016).

Plots that received applications of terbuthylazine (500 and 750 g ha−1) with or without the adjuvant, carfentrazone (80 and 120 g ha−1), 2,4-D, and saflufenacil often exhibited ryegrass control that was only just greater than or was statistically equal to that of the weedy control at all evaluations from 7 to 42 DAT (Table 9), where control did not exceed 25% This is because these herbicides are recommended for controlling dicot weeds and have limited or no activity on grasses. Terbuthylazine belongs to the triazine class, which consists of heterocyclic compounds that inhibit the D1 protein in photosystem II, halting electron transport and thus inhibiting adenosine triphosphate production and biosynthesis of proteins and carbohydrates that are essential for plant growth (Teixeira et al. Reference Teixeira, Aguiar, da Silva, da Silva, Siebeneichler, Ferreira Júnior, Lima, da Bastos, de Sousa and de Oliveira2024). The main selectivity mechanisms of herbicides against grass species involve metabolism and conjugation, processes mediated by cytochrome P450 and GST enzymes, respectively. These enzymes detoxify herbicides before they reach their cellular target sites, preventing damage (Powles and Yu Reference Powles and Yu2010). This metabolic detoxification likely explains the tolerance of ryegrass to terbuthylazine observed in this study.

Saflufenacil, a pyrimidinedione herbicide, inhibits PROTOX. Plants that tolerate saflufenacil exhibit reduced absorption and translocation and enhanced detoxification capacity, resulting in lower hydrogen peroxide accumulation and lipid peroxidation (Piasecki et al. Reference Piasecki, Bilibio, Fries, Cechin, Schmitz, Henckes and Gazola2017). This likely accounts for the poor control of ryegrass by saflufenacil in the present study.

The tolerance exhibited by plants to the herbicide 2,4-D involves limited phloem translocation mediated by auxin receptors (T1R1/AFB), which are responsible for triggering transcriptional and biochemical responses (Piasecki et al. Reference Piasecki, Bilibio, Fries, Cechin, Schmitz, Henckes and Gazola2017). These authors also report that the function of the T1R1 protein in plants is to perceive the herbicide and recognize the substrate, regulating the synthesis of abscisic acid and ethylene through the expression of the enzyme 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase in the plastid. According to Song et al. (2014), there is also a structural difference in the vascular tissue between dicotyledons and monocotyledons that contributes to the selectivity of auxinic herbicides in grasses (Poaceae), and different metabolic pathways and rates as well for 2,4-D degradation/metabolism.

For ryegrass control, clodinafop-propargyl (96 g ha−1), applied alone or in combination with terbuthylazine (500 and 750 g ha−1) and pyraflufen (3.75 and 5 g ha−1), provided the greatest efficacy compared to other treatments (Table 9). Notably, tank mixtures did not exhibit antagonism; any reduction in weed control compared to single applications was negligible. The improved ryegrass control observed with terbuthylazine and pyraflufen mixtures with clodinafop-propargyl is attributed to clodinafop’s specificity as a grass herbicide, targeting ACCase-sensitive species within the Poaceae family (Basak et al. Reference Basak, Alam, Goodwin, Harris, Patel, McCullough and McElroy2022).

Clodinafop-propargyl demonstrated the greatest efficacy against ryegrass at all evaluations from 7 to 42 DAT (Table 9). This is because the ryegrass population tested was not resistant to ACCase inhibitors, and clodinafop-propargyl is known for its high effectiveness on this weed. However, ACCase-resistant ryegrass biotypes have been reported in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (Vargas et al. Reference Vargas, Henckes, Schmitz, Piasecki, Cechin, Torchelsen and Agostinetto2018), though in regions different from this study’s location. Trezzi et al. (Reference Trezzi, Mattei, Vidal, Kruse, Gustman, Viola, Machado and Silva2007) reported more than 80% ryegrass control with clodinafop-propargyl in postemergence wheat applications, which is consistent with the present findings.

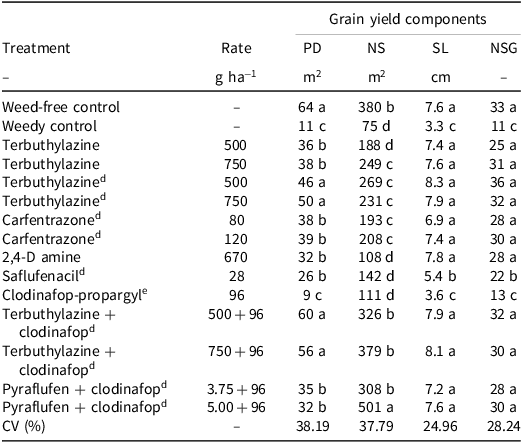

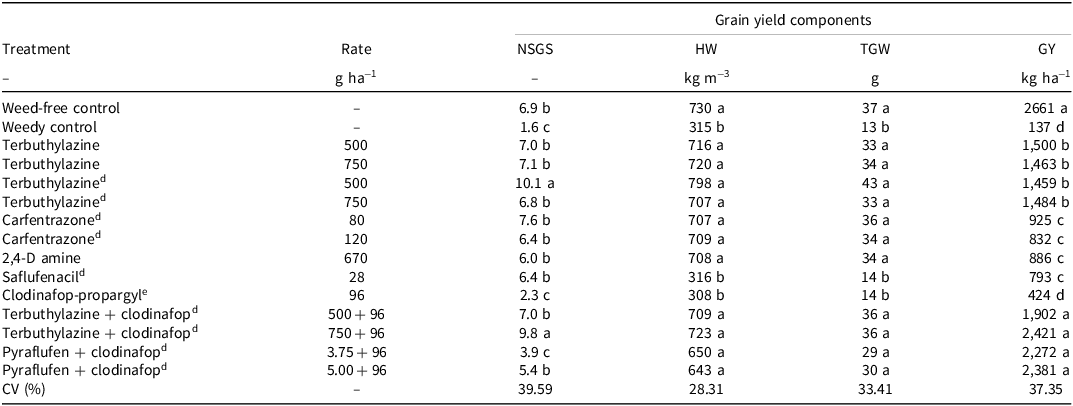

The weed-free control plots and plots that received terbuthylazine (500 and 750 g ha−1), or pyraflufen (3.75 and 5 g ha−1) mixed with clodinafop-propargyl, showed the best results for all wheat grain yield components (plant density, spike length, spike number per area, number of filled and sterile grains, hectoliter weight, TGW, and grain yield) compared to other treatments (Tables 10 and 11). This is likely linked to the effective control of wild radish (Table 8) and ryegrass (Table 9) provided by these treatments. Both weeds are highly competitive in wheat, and when uncontrolled, they directly affect crop growth and development, thereby negatively affecting grain yield components and quality, especially hectoliter weight and productivity. Similar results were reported by Raj et al. (Reference Raj, Kumar and Singh2020), who found improved grain yield components in treatments with superior weed control efficacy, corroborating the present study’s outcomes.

Table 10. Plant density, number of spikes, spike length, and number of filled grains per spike of the wheat cultivar TBio Audaz as affected by herbicide applications in the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons. a b c

a Abbreviations: CV, coefficient of variation; DAT, days after treatment; NSG, number of filled grains per spike; NS, number of spikes; PD, plant density; SL, spike length.

b Doses are listed in g ai or ae ha−1 depending on formulation.

c Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ statistically by the Scott-Knott test at α ≤ 0.05.

d,e The adjuvants Dash and Assist, respectively, were added at 5 mL L−1.

Table 11. Number of sterile grains per spike, hectoliter weight, thousand-grain weight, and grain yield of the wheat cultivar TBio Audaz as affected by herbicide applications in 2022 and 2023. a b c

a Abbreviations: CV, coefficient of variation; DAT, days after treatment; GY, grain yield; HW, hectoliter weight; NSGS, number of sterile grains per spike; TGW, thousand-grain weight.

b Doses are listed in g ai or ae ha−1 depending on formulation.

c Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ statistically by the Scott-Knott test at α ≤ 0.05.

d,e The adjuvants Dash and Assist, respectively, were added at 5 mL L−1.

The weedy control, safufenacil, and clodinafop-propargyl treatments showed the poorest results across all grain yield components compared to other treatments (Tables 10 and 11). Other treatments showed intermediate performance between the best performers (weed-free control, terbuthylazine + clodinafop at 500 + 96 g ha−1 and 750 + 96 g ha−1, pyraflufen + clodinafop at 3.75 + 96 g ha−1 and 5 + 96 g ha−1) and those with the worst results (weedy control, safufenacil, and clodinafop-propargyl alone).

Wild radish and ryegrass are highly competitive with wheat for water, light, and nutrients, and may also release allelopathic substances that inhibit crop growth and development, thereby negatively affecting grain yield components. The poor control of wild radish by safufenacil and clodinafop-propargyl (Tables 8 and 9) likely contributed to this effect. Saflufenacil is a contact herbicide; in fields with heavy wild radish infestation, a “shielding” effect may occur where smaller plants receive less or no herbicide, allowing regrowth. Additionally, saflufenacil lacks soil residual activity, enabling new weed emergence after application (Gazola et al. Reference Gazola, Gomes, Belapart, Dias, Carbonari and Velini2021).

Wild radish, a dicotyledoneous weed, possesses an ACCase enzyme making the weed insensitive to grass herbicides, which explains the lack of control when clodinafop-propargyl was applied (Lopes et al. Reference Lopes, Almeida, Gimenez, Oliveira and Dalazen2021). The herbicide 2,4-D is a synthetic auxin recommended for the control of eudicot species, with a relatively short residual effect. In some crops, the interval between application and sowing ranges from approximately 10 to 15 d, depending on the dose, crop species, soil characteristics, and climatic conditions (Gomes et al. Reference Gomes, Arantes, Andrade, Arantes, Viana and Pereira Junior2017; Rodrigues and Almeida Reference Rodrigues and Almeida2018). In the present study, 2,4-D provided less than 80% control of wild radish, which is the minimum efficacy required for herbicide recommendation in Brazil (Oliveira et al., Reference Oliveira, Freitas and Vieira2009). This low control can be mainly attributed to very low temperatures during and after application, which reduced the herbicide’s effectiveness. The lack of effect of 2,4-D on ryegrass is associated with the species’ biochemical and metabolic tolerance, as well as differences in vascular tissue structure between dicotyledons and monocotyledons, which confer selectivity to grasses (Piasecki et al. Reference Piasecki, Bilibio, Fries, Cechin, Schmitz, Henckes and Gazola2017; Song et al. Reference Song2014).

Terbuthylazine is a herbicide that can be applied either preemergence or postemergence and is recommended for the control of both monocot and dicot weeds in maize and sorghum crops in Brazil (AGROFIT 2025). It exhibits a soil residual effect exceeding 30 d, depending on factors such as application rate, soil characteristics, climate, physicochemical and biological degradation, and management practices (Calderón et al. Reference Calderón, De Luna, Gómez and Hermosín2015; Close et al. Reference Close, Sarmah, Flintoft, Thomas and Hughes2006; Garrett et al. Reference Garrett, Watt, Rolando and Pearce2015). However, wheat and ryegrass are able to metabolize terbuthylazine, which reduces its toxicity to these species, as observed in the present study.

Pyraflufen and carfentrazone are PROTOX-inhibiting herbicides with no soil residual activity, and are recommended for the management of dicotyledonous weeds, such as wild radish, and selective for grasses, including wheat and ryegrass, as studied in the present work (AGROFIT 2025; Han et al. Reference Han, Xu, Dong and Qian2007; Mabuchi et al. Reference Mabuchi, Miura and Ohtsuka2002). Since ryegrass can metabolize carfentrazone, this herbicide did not provide effective weed control, as can be seen in Table 9, which also contributed to reduced wheat grain yield (Table 11) due to the high competitive ability of this weed when it is not adequately controlled. The ryegrass caused a 59% reduction in wheat grain yield due to its infestation (Galon et al. Reference Galon, Basso, Chechi, Pilla, Santin, Bagnara, Franceschetti, Castoldi, Perin and Forte2019), demonstrating similarly high competitive ability. According to Lamego et al. (Reference Lamego, Ruchel, Kaspary, Gallon, Basso and Santi2013), wheat grain yield is directly affected by weed competition, with high losses occurring when weeds are not adequately controlled.

The application of tank mixtures (terbuthylazine + clodinafop at 500 + 96 and 750 + 96 g ha−1, and pyraflufen + clodinafop at 3.75 + 96 and 5 + 96 g ha−1) resulted in a 56% (1260 kg t ha−1) higher wheat grain yield than the average of other herbicides applied alone (Table 11). In this study, the average grain yield loss was 2190 kg t ha−1 when the weedy control is compared with yield loss from the treatments that provided the best control (weed-free control, terbuthylazine + clodinafop at 500 + 96 and 750 + 96 g ha−1, and pyraflufen + clodinafop at 3.75 + 96 and 5 + 96 g ha−1), representing a 94% reduction in productivity due to wild radish and/or ryegrass interference in wheat. Thus, controlling these weeds is essential to preventing significant yield losses. Lamego et al. (Reference Lamego, Ruchel, Kaspary, Gallon, Basso and Santi2013) reported wheat grain yield losses exceeding 80% when no control methods were applied, due to the high competitive ability of these weeds. The results of this study highlight the importance of applying herbicides that are selective to wheat and effectively control wild radish and ryegrass to avoid negative impacts on grain quality and yield.

In summary, herbicides that demonstrated the greatest phytotoxicity to wheat cultivar TBio Audaz were terbuthylazine (500 and 750 g ha−1) + adjuvant, carfentrazone (120 g ha−1), saflufenacil, and pyraflufen (3.75 and 5 g ha−1) + clodinafop. The best physiological performance of wheat plants was observed after applications of terbuthylazine (750 g ha−1), carfentrazone (80 g ha−1), 2,4-D, and terbuthylazine + clodinafop (750 + 96 g ha−1). Terbuthylazine (500 and 750 g ha−1) and pyraflufen (3.75 and 5 g ha−1) combined with clodinafop-propargyl (96 g ha−1) provided the best control of wild radish and ryegrass and the best performance in grain yield components, especially grain productivity of wheat cultivar TBio Audaz. If wild radish and ryegrass in wheat crops are not controlled, average grain yield losses of approximately 91% may occur. The alternative herbicides terbuthylazine and pyraflufen evaluated in this study have mechanisms of action that are distinct from those already widely used, such as ALS inhibitors and auxin mimics, and they exhibit promising potential for wild radish control in wheat crops. It is worth noting that terbuthylazine and pyraflufen may contribute to the management of wild radish, hairy fleabane [Conyza bonariensis (L.) Cronq.] and [Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronq.] and salvation jane (Echium plantagineum L.) (Heap Reference Heap2025), weed species that are resistant to ALS-inhibiting herbicides that infest wheat fields. Terbuthylazine and pyraflufen may also serve as alternatives to hormonal herbicides whose efficacy is reduced during the winter season due to low temperatures.

The results obtained in the present study, which evaluated the selectivity and efficacy of herbicides applied to the wheat cultivar TBIO Audaz, can be summarized visually in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Graphic summary representing the main results achieved with the use of herbicides in the TBio Audaz wheat cultivar.

Practical Implications

The herbicides terbuthylazine, carfentrazone, 2,4-D, saflufenacil, clodinafop-propargyl, and pyraflufen demonstrated good selectivity on the wheat cultivar TBio Audaz, even at higher-than-recommended doses, with or without adjuvants or tank mixtures. This is particularly relevant for the broadleaf herbicides (terbuthylazine, carfentrazone, saflufenacil, and pyraflufen), which are poorly studied for their effects on wheat in Brazil. Two of the products (carfentrazone and saflufenacil) are registered, while terbuthylazine and pyraflufen could be used for controlling critical weeds (AGROFIT 2025) such as wild radish that show resistance to ALS inhibitors and where 2,4-D is less effective at low temperatures.

Mixing broadleaf herbicides with grass herbicides, among the ones studied here, do not affect selectivity or weed control, indicating no antagonistic or phytotoxic effects. The study confirmed the safety of these products, including those not yet registered for use on wheat, such as terbuthylazine (a photosystem II inhibitor) and pyraflufen-ethyl (s PROTOX inhibitor), offering alternatives for managing herbicide-resistant weeds. It allows herbicide rotation with substitution of saflufenacil and carfentrazone with terbuthylazine to control broadleaf species such as wild radish, hairy fleabane, and black bindweed (Polygonum convolvulus L.), among others (Rodrigues and Almeida Reference Rodrigues and Almeida2018). However, further research using commercial formulations, adjuvants, and varietal tolerance tests is recommended to validate the use of terbuthylazine and pyraflufen for wheat cultivation in Brazil.

Funding

Financial support was provided by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Research Support Foundation of the State of Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS), Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP) and Federal University of the Fronteira Sul. Leandro Galon received Research Productivity grants (process number 312652/2023-2 and for financial support (403457/2023-8) from CNPq.

Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interests.