Foreword

Imagine a world where the heavy machinery of control – born in the smoky factories of the nineteenth century – gives way to a vibrant, living network of human potential. A world where people, not processes, drive progress, and where the rigid hierarchies of traditional management dissolve into fluid, self-organizing systems that pulse with creativity and purpose. This Element is your invitation to step into that world, to witness the dawn of a post-managerial era where freedom, commitment, and adaptability redefine what it means to build thriving organizations. It’s a story of liberation, grounded in the science of complexity, fueled by the courage of pioneers, and amplified by the limitless possibilities of digital innovation.

The old paradigm of management, forged by visionaries like George Whistler and Frederick W. Taylor, was a triumph of its time. It brought order to the chaos of sprawling industrial empires, offering predictability that won the trust of financiers and fueled economic growth. But every system carries the seeds of its own obsolescence. The very structures that promised stability – hierarchies, standardized processes, top-down authority – became shackles. They slowed organizations to a crawl in the face of disruptive competitors, choked resource flexibility with bureaucratic inertia, and silenced the creative spark of individuals buried under layers of oversight. These aren’t just flaws; they’re systemic failures that drain vitality from firms and sap economic potential.

As Thomas Kuhn taught us, when anomalies pile up and the old paradigm can’t explain them, a crisis emerges. That crisis is here, and it’s shaking the foundations of traditional management to its core. This Element doesn’t just diagnose the problem; it lights a path forward. It traces the evolution of management through its phases – control, leadership, technocracy – showing how firms like GE and IBM embodied its principles and reaped its rewards, but also its costs. Then, with the clarity of a Kuhnian lens, it reveals the shift to a new science of organization, one rooted in the principles of complex adaptive systems.

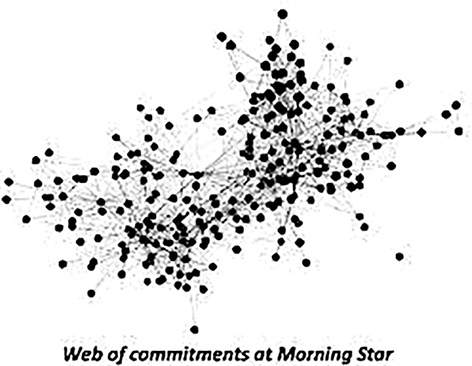

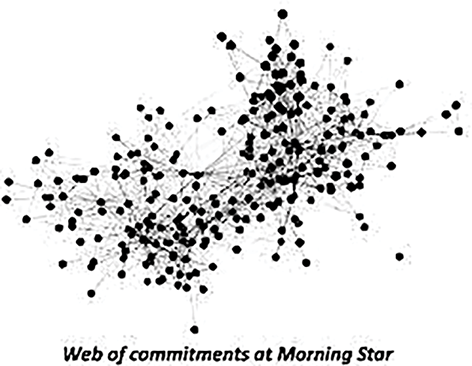

Forget the clockwork precision of Newtonian mechanics; the future belongs to systems that evolve through bottom-up interactions, emergent constraints, and what physicist Adrian Bejan calls flow – the removal of barriers to freedom, one degree at a time. This is a science of life, of adaptation, of possibility. At the heart of this revolution are the pioneers – organizations like W.L. Gore, Semco, Haier, Valve, Buurtzorg, and Morning Star. These aren’t just companies; they’re experiments in human freedom. Morning Star, where I enjoyed the privilege of contributing, is one part of this story. We operated without bosses, titles, or job descriptions, guided by two simple principles: no one coerces another, and every individual honors their commitments. Our Colleague Letter of Understanding (CLOU) system – where each person defines their voluntary promises to colleagues – didn’t come from a boardroom or a consultant’s playbook.

Morning Star’s form of self-management is a living example of spontaneous order emerging from myriad interactions like water molecules forming clouds, dissipating and re-forming. This isn’t theory; it’s reality. A company with a billion dollars in sales that enjoys global industry leadership, Morning Star proved that self-management scales, adapts, and thrives. Picture a dynamic, three-dimensional web of commitments, constantly reshaping itself to meet the needs of customers and colleagues, all without a single command from above. That’s the power of self-organization.

But the story doesn’t stop there. Technology is pushing the boundaries even further, weaving self-management into the fabric of hyper-personalized business models. Digitization has handed power to customers, who now demand exactly what they want, when they want it. Companies like Handu, an Asian e-commerce innovator, show us the future: a front-end of autonomous, entrepreneurial sites, backed by a digitally automated core and a robust infrastructure. Success drives resources, failure fades away, all guided by what a Harvard Business Review case calls “digitally enhanced directed autonomy.”

This is self-organization on steroids, blending human ingenuity with AI and data to create firms that don’t just react – they anticipate. What makes this Element sing is its rejection of the old paradigm’s obsession with formulas and checklists. Instead, it offers a pattern – eight emergent characteristics of the post-managerial age, from dynamic cohesion to the liberation of individual potential. This isn’t a recipe; it’s a worldview. As Kuhn warned, those wedded to the old ways may struggle to see it, but for those ready to embrace a new language of freedom and flow, the horizon is wide open.

This is about weaving constraints into a tapestry that amplifies outcomes, replacing control with enablement. It’s about trusting people to do what’s right because they’re committed to it, not because they’re ordered to. This Element isn’t just a reflection; it’s a call to arms. It challenges you – leader, thinker, doer – to dismantle the barriers that hold back human potential. Learn from the misfits who dared to experiment. Draw from the science of complexity that shows us how systems evolve. Harness technology not to control, but to empower. The result is a vision of work that’s deeply human, where purpose and creativity aren’t just allowed but unleashed, where organizations move like living organisms, resilient and ever evolving.

We’re at a turning point. The future of business isn’t about taming complexity; it’s about dancing with it. It’s not about imposing order; it’s about letting order emerge from the commitments and creativity of free individuals. This Element is your guide to that dance, your provocation to join the revolution. The post-managerial age is here, and it’s time to step into it with courage and conviction. Welcome to a world where freedom works.

1 Introduction: A Short History of Management

The twentieth century witnessed a long period of sustained effort to apply method to management. It was a scientific era where positivism – the belief that all legitimate knowledge must be derived from empirical observation and rational analysis – was the dominant intellectual framework. Management sought to align itself with the rigor of the natural sciences, influenced by the towering successes of mathematics and physics. Hard and fast laws were to be established for social sciences like economics and management by following the pathways of measurement, mathematical analysis, and experimental validation.

In fact, the precedents for twentieth-century management were laid down in the nineteenth century. Positivism became Europe’s dominant philosophy of science, the belief that all mysteries of the universe can be fully unraveled through scientific inquiry. These European positivist proclivities spilled over into the United States, and caught on strongly. The country that so admired innovation and entrepreneurs generated an immense optimism that science would soon solve all business problems and brilliant technocrats would engineer a new and better world. This positive technocracy was the climate in which management science emerged.

The 1841 Western Railroad Accident and George Whistler’s Management System

In October 1841, a serious train accident occurred on the Western Railroad, which connected Albany, New York, and Worcester, Massachusetts. A head-on collision resulted in two deaths and many injuries. Worse than the death and injury toll was the severe jolt the accident gave to the national psyche and people’s trust in industrialization. The tragic accident was a wake-up call for the railroad industry, which was in its early stages of development in the United States. The crash revealed not only the inherent dangers of rail travel but also significant gaps in the organization and management of railroads.

The collision was due to poor communication and coordination. Consulting engineer George Whistler identified issues of scheduling, authority, and information flow between personnel, resulting in an environment where mistakes and accidents could easily occur. He judged that the accident underscored the lack of a clear, hierarchical authority structure in railroad management – one that could ensure accountability and the smooth flow of information.

In designing a management solution, Whistler applied his military background and the principles of military organization – specifically, the Prussian military command structure – to the management of the railroad. The Prussian army was known for its emphasis on discipline, clear chains of command, and centralized control, principles that Whistler saw as applicable to the complex and dangerous operations of the railroad.

His design specifically included (1) centralized authority with a clear hierarchy and distinct layers of authority and responsibility; (2) a formal command structure in which train conductors, engineers, and other staff members were given specific roles and responsibilities, with orders flowing from the top down; (3) strict formalized scheduling and timetables; (4) structured reporting of incidents and performance to superiors.

In many ways, we can identify George Whistler and the Prussian military as precursors of the management systems we have inherited. His written report and recommendations were widely circulated through the new class of managers that was just coming into being.

The Foundations of the Management Paradigm

Phase 1: Management for Operational Control

The expression of the principles of Whistler’s design for railroad administration took the form of management for operational control of industrial businesses. We can highlight three early prophets who documented this new drive for control.

Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856–1915) was one of the first to employ the positivist view of business – that business managers can engineer maximum efficiency through carefully applied scientific principles – to attempt to establish a discipline of business management, to be studied and applied with methodical precision. In this context, he was “one of the individuals who had the greatest influence on the 20th century” (Alexander, Reference Alexander2020). He aimed at a monopoly for managers of knowledge about work tasks and processes in order to rigidly control them.

His high purpose was “greater national efficiency” (Taylor, Reference Taylor1911), and his method was to dehumanize the work process: “In the past the man has been first; in the future the system must be the first.” The remedy for human inefficiency was to be found in the principles of scientific management: “management is a true science, resting on clearly defined laws, rules and principles as a foundation.” He claimed that this science would double the output of each man and each machine, mostly by eliminating the practice of “loafing or soldiering … the natural instinct and tendency of men to take it easy.”

Taylor’s book, The Principles of Scientific Management, set out to demolish the old idea that each workman can best regulate his own way of doing the work. The new science of management placed the entire responsibility on management, who were to analyze and standardize work steps and ensure that they were carried out in a predefined sequence at a predefined pace. Workers could be viewed by managers as a kind of machine to be monitored and controlled.

Taylor wrote that “Taylor wrote that “the fundamental principles of scientific management are applicable to all kinds of human activities, from our simplest individual acts to the work of our great corporations. The fundamental principles of scientific management are applicable to all kinds of human activities, from our simplest individual acts to the work of our great corporations.”

As he had hoped, Taylor’s approach became a standard. It was widely adopted in industry (e.g., by Ford Motor Company in assembly line manufacturing), in World War I military logistics, and in business schools, where courses in scientific management drew heavily on Taylor’s work. The Progressive era saw an Efficiency Movement, lauded by leaders such as Andrew Carnegie and John D Rockefeller, and even by President Theodore Roosevelt, whose call for national efficiency was cited as a driver by Taylor in the introduction to The Principles of Scientific Management.

Henri Fayol (1841–1925) was a contemporary of Taylor who developed Administrative Management Theory. While Taylor focused on the shop floor and task efficiency, Fayol addressed a different dimension – the overall structure and function of management at the organizational level. He identified five functions of management: planning, organizing, commanding, coordinating, and control (Fayol, Reference Fayol1917). Within the five functions, he found fourteen principles, including Authority and Responsibility, Discipline, Unity of Command, and Subordination (of individual interest to general interest). He also included Esprit de Corps as the last item in the list of fourteen principles! He set out a theory of management based on the fourteen principles and proposed that administrative management could be taught on this basis.

Fayol’s management principles led to him being called the father of modern management (Wren, 2002). It has been suggested that Fayol’s fourteen principles metamorphosed into present-day management and the burgeoning administrative formation that exhibits itself all across the globe (Uzuegbu, Reference Uzuegbu2015).

Elton Mayo (1880–1949) was a leader in – some say the founder of – the human relations movement within management theory, specifically applying his attention to the behavior of people in groups. Some of his source material came from The Hawthorne Studies, a series of observations and interviews in the 1920s and 1930s in the context of factory assembly of electrical components. The Hawthorne Studies were interpreted through the lenses of the productivity benefits of social dynamics and team cohesion. Mayo saw work as a profoundly social activity, and identified workers’ social and psychological needs that management must attend to. Mayo’s integration of psychology into his interpretation of motivational and productivity variables emphasized communication, collaboration, and the management of feelings and emotions to encourage compatible relationships in social groups within companies. This more human-centered, psychology-informed approach, emphasizing the importance of interpersonal relationships and group dynamics, can be viewed as an extension of Taylor’s and Fayol’s focus on the measurement and organization of behavior. It expanded the management paradigm into psychology and informal networks, and supported concepts such as employee engagement. Nevertheless, the goal remained the increase in efficiency and the elimination of variance in performance compared to benchmarks.

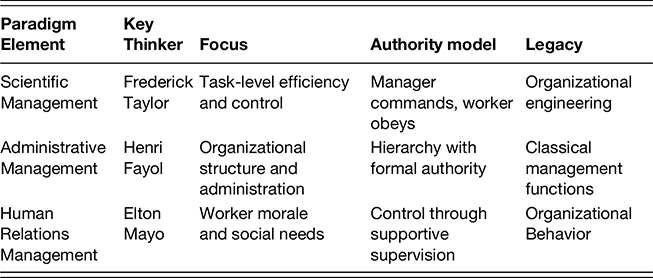

We can group (see Table 1) the Taylor, Fayol, and Mayo views of management into a grouping that represents the first phase of the development of the original management paradigm; management for operational control, with the goal of extracting productivity from the workforce.

| Paradigm Element | Key Thinker | Focus | Authority model | Legacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Management | Frederick Taylor | Task-level efficiency and control | Manager commands, worker obeys | Organizational engineering |

| Administrative Management | Henri Fayol | Organizational structure and administration | Hierarchy with formal authority | Classical management functions |

| Human Relations Management | Elton Mayo | Worker morale and social needs | Control through supportive supervision | Organizational Behavior |

Phase 2: Elevation of Management to Leadership

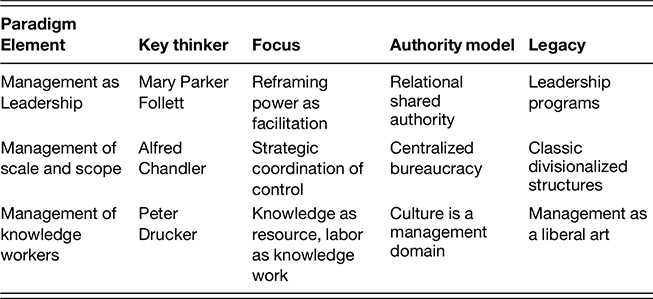

As management began to evolve into a profession, practiced as a form of control within a context of hierarchical authority, it was allocated social prestige. The concept of management as leadership emerged (see Table 2).

| Paradigm Element | Key thinker | Focus | Authority model | Legacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management as Leadership | Mary Parker Follett | Reframing power as facilitation | Relational shared authority | Leadership programs |

| Management of scale and scope | Alfred Chandler | Strategic coordination of control | Centralized bureaucracy | Classic divisionalized structures |

| Management of knowledge workers | Peter Drucker | Knowledge as resource, labor as knowledge work | Culture is a management domain | Management as a liberal art |

Mary Parker Follett (1863–1933) was one of the most important early influences in establishing leadership as a management concept. She did not recommend eliminating hierarchy, but saw leadership as a management skill that could be exercised as a lateral process in a traditionally vertically organized company. Importantly, leadership power emanated from authority of expertise in addition to position in a hierarchy. In this context, management power could be less coercive and more facilitating, integrating and collaborative (“power with” rather than “power over”), without losing sight of the purpose of “getting things done” (Peek, Reference Peek2024). In other words, she saw leadership as another form of power to control others. We may think of the concept of leadership in business as a very contemporary idea in the twenty-first century, but Warren Bennis asserted that “Just about everything written today about leadership and organizations comes from Mary Parker Follett’s writings and lectures” (Bennis, Reference Bennis and Graham2003).

Alfred Chandler (1918–2007) viewed management through the lens of organizational strategy and corporate structure. He was a business historian who documented the path to scale – he referred to mass production, mass distribution and mass marketing – and plainly admired the achievement of not only the great industrialists who built the large corporations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but equally of the appointed executives who took over from the founding entrepreneurs and administered and managed their burgeoning creations. His book titles included Strategy and Structure and Scale and Scope, and, most tellingly, The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Chandler defined management as the complex administrative system required to bring cohesion to industrial scale corporations, via the control that could be exerted through organizational design, including hierarchy, top-down systems, integration achieved through divisionalization and departmentalization, process documentation, and detailed job descriptions. He proposed a managerial revolution (the positivist visible hand replacing Adam Smith’s subjectivist invisible hand) and the consolidation of a managerial class. While Chandler did not write much about “how to manage,” he did a lot to further elevate the profession of management to the highest levels of aspiration. It was a practice of the largest, and therefore best, corporations, to be admired and emulated.

Peter Drucker (1909–2005) elevated the profession of management to an even higher level of vocation and philosophy. He was dubbed a “management guru” who shaped management practices. One of his biographers elevated him to the position of “champion of management as a serious discipline” (Beatty, Reference Beatty1998). He introduced the term “knowledge worker” (Drucker, Reference Drucker1959), highlighting the intellectual capabilities required for management, and designated management as a “liberal art” (Drucker, Reference Drucker2006), integrating perspectives from philosophy, culture, and sociology. He emphasized the ethical responsibilities of management, as well as execution. This was not a departure from control. His concept of management by objectives established accountability and performance measurement for specific, measurable goals set by the authority levels in the firm. He saw control over resource allocation as crucial for achieving strategic objectives. Cultural alignment was an aspect of “soft” control – Drucker’s management cultures were strong in employing norms and shared beliefs to guide employee behavior.

Phase 3: Management by Technocrats

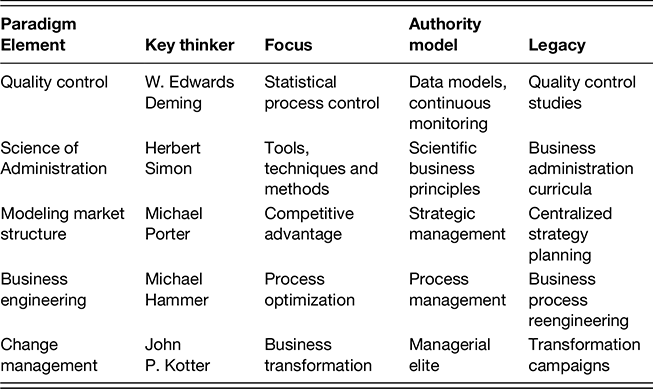

As data and technology became resources to management, the processes and practices of management adopted and integrated them into the scientific method (see Table 3).

| Paradigm Element | Key thinker | Focus | Authority model | Legacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality control | W. Edwards Deming | Statistical process control | Data models, continuous monitoring | Quality control studies |

| Science of Administration | Herbert Simon | Tools, techniques and methods | Scientific business principles | Business administration curricula |

| Modeling market structure | Michael Porter | Competitive advantage | Strategic management | Centralized strategy planning |

| Business engineering | Michael Hammer | Process optimization | Process management | Business process reengineering |

| Change management | John P. Kotter | Business transformation | Managerial elite | Transformation campaigns |

W. Edwards Deming (1900–1993) added another dimension to the managerial control spectrum, that of statistical control. Encapsulated in a theory of Total Quality Management (TQM), Deming’s approach was to emphasize a characteristic he called “quality,” defined as consistent production without error on a track of continuous improvement measured by systematic data collection and analysis, which together defined a practice known as quality management. He specifically preferred management by numbers to management by objectives (Deming, Reference Deming1982). Statistical process control became established as a benchmark source for efficiency and productivity assessments.

Herbert Simon (1916–2001) was one of the most influential management scholars. He studied at the University of Chicago, and recalled that, amongst his professional colleagues, “Logical positivism was the dominant, perhaps exclusive religion in this group” (Simon, Reference Simon1996). Simon’s book, Administrative Behavior, published in 1945, became the seminal textbook for teaching business administration, now the focus of the MBA. It proposed a fundamentally scientific approach to business management, whereby management scholars can develop tools and proven techniques for managers to apply to engineer better performance and efficiency. He proposed scientific principles of design so that even innovation could be engineered rather than left to the creative whims of entrepreneurs. Administration was everything for Simon, and his influence remains strong and pervasive throughout the business schools of today, where students learn Simonian administration and the tools, techniques, factors, methods, and processes to implement it. These students are then sent out to replicate these tools and methods in the business firms they join.

Michael Porter (1947–) introduced a greater focus on external market forces extending beyond internal managerial control. Managers should not only aim at controlling internal variables, but also analyze external forces and respond to them, and ideally shape them, in their strategic processes. Competitive strategy and strategic positioning became the new expressions of acute management insight and superior capability. Paralleling Chandler’s use of corporate structure as a design tool for management organizations, Porter used industrial structure as an analytical tool for the establishment of what he called competitive advantage, an ideal of insulation, albeit partial and temporary, from the negative impacts of market forces, including competitive actions. Following Porter, managers could, like William F. Buckley in the political arena, stand athwart history yelling “Stop!” Strategic planning became the iconic vocation of MBA graduates.

Michael Hammer (1948–2008) added process control to the management control portfolio via the methods of business process reengineering, which quickly became identified by the acronym BPR. The core of the method was to identify all the processes at work in a company’s operations, define the current state of these business processes in step-by-step detail, identify issues at that level of detail, and address them through micro-level re-design (or “change management”) tools, which eventually took their own names, such as Lean and Six Sigma. One of the consequences of the reengineering movement was the use of mass layoffs from the workforce to cut costs in inefficient companies, giving this form of management practice a bad name in PR. Nevertheless, BPR and the concept of reengineering remain prominent in the management lexicon, suggesting the imagery of business firms as machines to be tuned and then run at high throughput levels under the control and direction of an engineer cohort.

John P. Kotter (1947–) proposed that leadership was the tool for change management (Kotter, Reference Kotter2012). In this context, management leadership is presented as a process rather than an exceptional attribute or characteristic, and anyone following the eight-step process can claim leadership. These managers establish the vision for change, set direction for action, and organize implementation. “Transformation” was a frequently used term for the results sought, implying great power for the managers who adopted the process.

The Management Paradigm in Practice

Paradigms solidify when they are associated with success. What we can identify today as the negative consequences of scientific management were disguised by the mid twentieth-century success of some iconic firms. The 1950s–1990s provided a unique economic context of industrial expansion and global dominance of American companies, despite any management inefficiencies. The United States had few global competitors immediately after World War II, when Germany and Japan were recovering and China had not yet industrialized. American corporations benefited from low global competition, rapid urbanization, and mass-market consumer demand, and not necessarily from superior management science.

Some firms used scientific management science effectively – for a time. General Electric, under both Reginald Jones and Jack Welch, applied rigorous efficiency-driven restructuring to boost short-term performance, but ultimately over-optimized and struggled in the long run.

GE CEO Jack Welch was lauded by Harvard Business Review as the greatest leader of his era (Fernandez-Araoz, Reference Fernandez-Araoz2020). One of the reasons he was praised was the reign of GE as the number one company in the world for five years, starting in 1993. In the world of management by objectives, the number one objective for CEOs of public companies was the stock price, total market value, and return to shareholders, and Jack Welch met his objectives. One of the tools was “earnings management”: the consistent delivery on quarterly earnings growth targets and dividend payments. Welch assembled GE as a conglomerate through acquisitions, and built a division of GE, GE Capital, into a collection of financial assets (such as insurance companies) that held liquid assets that could be used, by moving and transferring them appropriately, to smooth quarterly earnings and confidently meet the expectations of the financial sector and so maintain stock prices (Hastings, Reference Hastings2024a). This practice was a form of “financial engineering,” one example of the many levers of detailed control that were developed by the twentieth century’s managerial specialists.

Similarly, IBM in its mainframe era benefited from scale efficiencies and appeared to master Porter’s five forces, but only until new technologies undermined its monopolistic market conditions and exposed its rigid structure. Sears was an effective pioneer of structured retail operations but failed to adapt to the introduction of e-commerce.

Eventually, the management science icons toppled. GE suffered from overmanagement, bureaucracy, and a failure to innovate. The company’s decline can be linked to rigid adherence to hierarchical structures and an overemphasis on efficiency metrics, hallmarks of scientific management (Schrager, Reference Schrager2019). The scientific method adopted by Jack Welch favored aggressive cost-cutting and divestitures of businesses that were not number one or number two in their industries. While initially successful, it eventually resulted in under-innovation and failure to respond to market change. The company’s bureaucracy, installed to develop a special expertise in designing and enforcing scientific methods, hindered the company’s adaptiveness and contributed to its downturn.

IBM nearly collapsed in the 1990s due to its slow response to the PC revolution. Inflexibility led to substantial losses. IBM required a cultural change, rather than a scientific one, in order to adopt a more decentralized and customer-focused approach and to eventually recover.

Scientific management worked in predictable, stable environments but collapsed in the face of technological change and competitive disruption. Scientific management appeared to be effective in a special economic era, but the constraints of lowered engagement and motivation, bureaucratic inefficiencies, frustrated creativity, and stifled adaptiveness led to the decline of once-dominant firms.

A Philosophical Problem

Hannah Arendt pondered the threat to humanism of the increasing drive to redesign and control the world through transformative science and technology (Arendt, Reference Arendt1958). For her, the main culprit is an idea – the idea that the world is objective. It’s an alienating idea because it disengages us from reality, and creates an artificial world, stripped of humanistic concerns. With the objective approach, our businesses become objects like any other, reduced to data points to be managed, and they lose their civilizational potential. We engineer and transform them, and they lose their human value. The loss of agency and autonomy that are consequences of managerial control, and the devaluation of human qualities such as spontaneity, creativity, and judgment that is implied, are the inevitable outcomes of what Chandler called the managerial revolution.

But in business management, the mode of thinking we call positivism won the day. Business philosophy became associated with positivist ideas of identifying causality through scientific observation. There was an immense optimism that science would soon solve all business problems and that business technocrats would engineer a new and better world. It was not to be.

2 The Consequences of Managerial Systems

While Hanna Arendt was making an existential appeal about positivism in general, it is appropriate to draw some parallels between management practices and their consequences, and her critique of the modern drive to control the world through science and technology.

Bureaucratic Processes: Corporate bureaucracy and the widespread adoption of bureaucratic processes within organizations have been the inevitable consequences of the managerial approach to business. The management approach, the evolution of which we tracked in Section 1, emphasizes control. Formal rules and procedures, hierarchical structures, and clear lines of authority are designed and imposed to implement this control. People must implement the prescribed processes, subject themselves to the prescribed measurements, follow the rules, and be “loyal.” Jobs are clearly defined in terms of rank, salary, and duties. In the pursuit of efficiency, specialization becomes narrower and narrower for each job, permitting the individual to use a limited range of their human abilities. People become subordinated and dependent.

The term bureaucracy is “always applied with an opprobrious connotation” (Mises, Reference Mises1944). No one likes it. But because of managerialism, bureaucracy has become “the water in which we swim” (Graeber, Reference Graeber2015). Business has become accustomed to it. Sociologist Max Weber saw bureaucratic forms of organization as superior to any alternative form, indispensable for large firms and institutions, even though the inevitable result was to lock humanity in a joyless “iron cage.” Robert K. Merton captured the problem (Merton, Reference Merton1949) as bureaucratic dysfunction, a cause of social disruption rather than stability. It’s a sad picture.

Heavy-handed Control: Management systems aim to eliminate variance from plans and forecasts and reduce outcome uncertainty as much as possible. Since variation and selection are normal conditions in markets, the extent of the control effort must be considerable to overcome them. Decision-making is centralized in the hands of senior management in pursuit of goals of uniformity and productivity. Henry Ford’s management style at the Ford Motor Company established the uniformity norm early in the twentieth century, and, despite the high turnover rates and labor unrest that followed, Ford’s methods were often imitated. Douglas McGregor (McGregor, Reference McGregor1985) called this management style “Theory X.” It rests on the assumption that it is the nature of humans to be lazy and not very capable, and that management must be authoritarian and control-oriented to extract effort from them.

Performance Metrics: Use of Quantifiable Measures to Assess Performance and Productivity. The managerial revolution brought with it a focus on performance metrics, where managers relied heavily on quantifiable measures to evaluate productivity and efficiency. The obsession with quantification to the exclusion of qualitative evaluation represents the widespread adoption of Frederick Winslow Taylor’s principles of scientific management, where time and motion studies were used to determine the “one best way” to perform tasks. Over time, this reliance on metrics evolved into complex systems of performance evaluation, such as the Balanced Scorecard developed by Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton (Kaplan, Reference Kaplan1996), which expanded the focus beyond just financial measures to include customer satisfaction, internal processes, and innovation. While performance metrics have improved accountability and clarity, they have also been criticized for encouraging short-term thinking and neglecting human factors, as discussed in Michael Jensen’s critique of performance measurement systems in his work on “agency theory” (Jensen, Reference Jensen1998).

The focus on what can be measured rather than what truly matters undermines qualitative judgment, intuition, experience, and the application of context-specific knowledge, which are vital to maintaining customer service standards and responsiveness. It can also create a culture of superficiality where employees seek out ways to game the system and never experience the joy and satisfaction of meaningful work. Ian McGilchrist (McGilchrist, Reference McGilchrist2019) sees quantification as part of Western society’s left hemisphere–dominated analytical, logical, and reductionist approach that threatens the health of not just organizations but also the broader culture and civilization.

Standardization: Implementation of Standardized Practices and Policies across the Organization

Standardization became a hallmark of the managerial revolution, as companies sought to ensure consistency and efficiency across all operations. Standardization also extended to administrative functions, so that procedures such as budgeting, scheduling, and reporting often became formalized and rigid. The whole point of standardization was to bring about significant efficiencies and to limit flexibility and adaptability. When Japanese companies were the first to emphasize the need for systems to be adaptable and responsive to changes in the environment in order to achieve continuous improvement and enhance quality, Western companies encountered difficulties in shedding standardized practices. Toyota Production System workers could follow the practice of Jidoka to take prompt action to correct a problem at any point in the production process. Jidoka can be translated as automation with human wisdom (Turner, Reference Turner2020), a nonstandardized mindset.

Professional Management: The managerial revolution elevated the role of professional managers, positioning them as experts and key figures in the achievement of organizational goals. This shift was notably articulated by Peter Drucker, who argued that management itself had become a crucial institution in society, responsible for the economic and social well-being of employees and the community. The rise of the MBA degree, pioneered by institutions like Harvard Business School, reflects this professionalization of management, training individuals to approach business problems with analytical rigor and strategic thinking. However, this professionalization also led to a separation between ownership and management, as explored by Berle and Means in “The Modern Corporation and Private Property,” which highlighted the potential for conflicts of interest between managers, who control the day-to-day operations, and shareholders, who own the company.

Economist Ludwig von Mises wrote that the rise of managerialism and the managerial class undermined the fundamental principles of capitalism: “The capitalist system is not a managerial system; it is an entrepreneurial system” (Mises, Reference Mises1998). For von Mises, the function of entrepreneurship is the determination of how and where to deploy capital, especially in new and innovative ways to meet customer needs. The execution of other details is left to the function of management. The managerial function is subservient to the entrepreneurial function. When scientific management overturns this relationship, the entrepreneurial driving force of the market system, with all its innovation and imaginative value creation, is reined in.

Stifling Creativity and Innovation: Overemphasis on Rules and Procedures Can Limit Flexibility and Discourage Creative Thinking

Managerialism often imposes rigid structures, standardized procedures, and strict adherence to established practices. While they were developed to ensure efficiency and consistency, they often resulted in stifled creativity and innovation. An example that is often cited is the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) in the 1970s. PARC was responsible for groundbreaking innovations like the graphical user interface (GUI) and the computer mouse. However, the rigid corporate structure at Xerox failed to recognize and capitalize on these innovations, which were later successfully developed by companies like Apple and Microsoft. This illustrates how a focus on rules, procedures, and existing business models can cause organizations to miss out on potentially transformative ideas.

Clayton Christensen’s concept of “The Innovator’s Dilemma” (Reference Christensen1997) further explores this issue, showing how successful companies often fail to innovate because their processes and structures are optimized for existing products and markets, making them resistant to disruptive innovations. The managerial focus on maintaining control and efficiency can lead to a risk-averse culture where employees are discouraged from taking the creative risks necessary for innovation.

Reducing Empathy and Employee Well-being: Focus on Metrics and Performance Can Lead to Neglect of the Human and Emotional Aspects of Management

The emphasis on quantifiable metrics in managerialism was belatedly understood to cause the neglect of the human aspects of management, such as empathy, employee well-being, and emotional intelligence. This became evident in so-called “high-pressure environments” where performance metrics dominated the organizational culture, such as in some financial services and tech companies. A case in point is the “Wells Fargo scandal” of 2016, where the bank’s intense focus on numerical sales targets led to unethical behavior, including the creation of millions of fake accounts. The relentless pressure to meet sales goals, without regard for employee well-being or ethical considerations, fostered a toxic work environment and severely damaged the company’s reputation.

Daniel Goleman’s work on Emotional Intelligence (Reference Goleman1995) emphasizes the importance of empathy, self-awareness, and social skills in leadership. He argues that these qualities are often undervalued in traditional management approaches that prioritize metrics over human relationships, and that the measurement focus leads not only to unhealthy work environments but also to poorer long-term organizational performance.

Centralization of Power: Concentration of Decision-making Power in the Hands of a Few Managers, Potentially Leading to a Disconnect with Lower-level Employees and Customers

A core tenet of the managerial revolution was to centralize corporate power, so that decision-making is concentrated at the top levels of the organization. This created a kind of management feudalism, a significant disconnect between senior managers and lower-level employees, as well as between the organization and its customers. An example of this is the decline of Kodak, once a dominant player in the photography industry. Kodak’s management was slow to adapt to the digital revolution, partly because decision-making was highly centralized and insulated from the insights and innovations emerging at lower levels of the company. The leadership’s focus on maintaining the status quo in film photography led to a failure to embrace digital technology, ultimately resulting in Kodak’s bankruptcy in 2012.

The dangers of centralized power are also highlighted in Chris Argyris’ work on Organizational Learning (Reference Argyris1992). Argyris argues that centralized decision-making structures can hinder organizational learning by suppressing feedback from lower levels and discouraging open communication. This can lead to a lack of responsiveness to changes in the external environment and a failure to innovate or address emerging problems effectively.

Overall, the managerial emphasis on control, efficiency, and metrics has brought negative consequences for creativity, employee well-being, and organizational adaptability.

3 Shifting the Paradigm: Anomalies and Crisis

The control-focused approach to business management that dominated for most of the twentieth century represents a paradigm: the most broadly accepted philosophy of business management, the standard model to be followed by members of a community.

When Thomas Kuhn used the term paradigm in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, his context was the scientific community, where the “accepted examples of scientific practice, including laws, theories, applications, experiment and instrumentation provide the models that create a coherent tradition and serve as the commitments which constitute a scientific community in the first place” (Hacking, 1962).

The concept of a paradigm is legitimately transferable to the management community, those academics, consultants, practitioners, and students who frame the philosophy and culture of business management and their cultural application.

Kuhn portrayed a paradigm shift (a scientific revolution, in his words) as a change in worldview, a new cognitive orientation, constituting progress from less adequate to more adequate conceptions of the world. Science advances by alternately constructing and destroying paradigms.

In Kuhn’s view, a paradigm is all-encompassing, from a set of philosophical assumptions “at the top” to methods and tools “at the bottom.” Between the top and the bottom are theories and some specific examples of solved problems, which are important components of the paradigm (Hillix & L’Abate, Reference Hillix, L’Abate and L’Abate2012). Kuhn calls them paradigmatic examples; we can equate them directly to case studies in business schools or consultant recipes for business success, or biographical histories published by business executives. In fact, Kuhn points to the role of specialized textbooks and history books in scientific disciplines as having the effect of rationalizing and glorifying the paradigm. Writers claim developments that lead to the “correct” paradigmatic view. Readers and adherents develop great fondness for the paradigm. The paradigm is socioculturally constructed; the process is subjective, a system of values about how to perceive reality, a collective style of thinking (Guerra, Capitelli, & Longo, Reference Guerra, Capitelli, Longo and L’Abate2012).

The inclusive paradigm must demonstrate results and accomplishments to attract the allegiance of the majority of practitioners in the field. The paradigm must make clear predictions. Eventually, those nurtured within the paradigm come to accept it without much inquiry about the preconceptions that are involved.

As a consequence, the paradigm is not easily given up. When experience does not agree with expectations, the anomaly is shrugged off as an unimportant exception or error. This explains why, in the field of business management, we observe that traditional management practices and forms of organization are maintained even when the competitive marketplace demonstrates the disruptive power of new approaches.

But in Kuhn’s construct, the anomalies become so frequent and so obvious that they can’t be ignored. The paradigm enters “crisis” mode.

New practitioners, often younger than the paradigmatic loyalists, start to propose alternatives. Thy conduct some new experiments. Eventually they triumph by solving some of the problems posed by the anomalies. The new paradigm attracts new converts. It establishes new methods, new problems, and new language. The new paradigm will not solve all of the problems, and may introduce some new ones. The world is seen differently.

The Paradigm in Crisis

The consequences of the management paradigm become the anomalies of the Kuhnian framework – the unresolvable errors that undermine and ultimately collapse the system. Some of the anomalies of the type that Kuhn identified as leading to crisis are easily visible.

Centralized Authority and Hierarchy Control People but Not Outcomes

The hierarchy of authority is the foundational characteristic of the old paradigm. The standard organizational design is for a top-down, centralized authority structure, with a CEO, C-suite, and Board of Directors at the apex, supported by layered hierarchies of vice-presidents, executives, managers, and supervisors. Leadership and authority are tied to titles, which signify rank and decision-making power within a rigid chain of command. Leadership is framed as the exercise of vision-setting, decision-making, and directive-giving from the top, with the assumption that strategic insight resides at the apex. Job descriptions define what each individual must do in their daily work. The structure defines how power, decisions, and resources are distributed. It underpins all other elements, such as planning and management, and is a primary source of rigidity. The inherent assumption that strategic insight and competence reside at the top marginalizes lower-level contributions.

Hierarchical control systems were designed for a stable business world of relatively slow change. Anomalies arise as change accelerates in the economic ecosystem and rapid adaptation becomes needed. Decision-making bottlenecks occur, and frontline knowledge is ignored. The hierarchy fosters bureaucracy, slowing responsiveness in dynamic markets, as seen in cases like Kodak’s slow response to digital photography. What seemed to be controllable becomes fragile and susceptible to disruption. The system becomes unstable because it can’t adapt to external change fast enough.

The Mechanistic Production Model Fails in a World of Customer Primacy

The old-paradigm organization operates on an inside-out production model, which was originally designed to manufacture standardized products or services for consumption. The focus is on optimizing internal processes to maximize output, with customers positioned as recipients of what the organization produces. This production-centric mindset is a core driver of the paradigm, shaping strategy, segmentation, and resource allocation. It prioritizes efficiency over customer-centricity, which can prove to be a key limitation in today’s customer-dominated markets.

This model assumes predictable demand and stable markets, but anomalies emerge when customer preferences shift rapidly or when customization is demanded (e.g., via digital platforms). The inside-out approach disconnects organizations from evolving customer needs, as seen in, for example, Blockbuster’s failure to adapt to streaming (Davis, 2013).

The old paradigm is challenged by the new active role customers play in determining the flow of innovation from the outside in.

Top-Down Strategy and Competitive Positioning

Strategy is formulated centrally, focusing on competitive positioning within defined industry boundaries (“where to play, how to win”). It emphasizes market share, differentiation, or cost leadership, often benchmarked against rivals, with an aim to dominate specific market segments. Strategy sets the organization’s direction and resource allocation, making it a high-influence characteristic. Its competitive, zero-sum focus shapes the organization’s worldview.

This approach assumes stable industry structures and linear competition, but anomalies arise in disruptive environments where boundaries blur (e.g., Amazon entering healthcare). The focus on rivalry over collaboration or ecosystem-building limits adaptability, as Nokia experienced when its focus on dominating the mobile phone market blinded it to the smartphone ecosystem shift driven by Apple and Google.

Strategic planning can get in the way of the experimental action required for adaptation to changing markets. Modern tech companies are finding that a dynamic portfolio of experimental initiatives and projects, given time to mature into new businesses or new service offerings, gives better results than forward planning. They identify large profit pools across industries where multiple firms can be successful without fighting over market share. Alphabet’s multiple revenue generation sources, ranging from internet search to media to self-driving cars, cloud computing, chips and AI, horizontally linked by AI and infrastructure, provides a contemporary example where competition for market share is not a highly relevant constraint.

Segmented Organizational Structure

The paradigmatic organization is divided into siloed units – departments, functions, regions, or business units – for control and specialization. Each segment operates with defined roles, budgets, and objectives, often competing internally for resources. Segmentation is a structural enabler of control, but significantly influences inefficiency and disconnection by increasing the organizational cost of cross-functional collaboration. Consequences include misaligned priorities and duplicated efforts.

In dynamic markets, silos struggle to integrate knowledge or respond holistically to customer needs, as we see with traditional automotive firms lagging in electric vehicle integration because siloed R&D and marketing functions struggle to align, delaying product innovation.

Organizational initiatives seek to address the silo problem through horizontal collaboration, flexible role descriptions and distributed functionality. But a full shift to a self-organizing network is prevented by the fundamentals of the hierarchical control orientation.

Centralized Planning and Target-Setting

The old paradigm organization relies on centralized, periodic planning cycles that produce detailed plans and numerical targets for all segments and individuals. Targets are often ambitious (“stretch goals”), tied to incentives for achievement and penalties for failure, driving performance evaluation.

Planning and targets operationalize strategy but their rigidity is a major source of anomalies. The planning approach assumes predictability and control over outcomes, but anomalies emerge in volatile environments where plans quickly become obsolete, or struggle to accommodate real-time shifts, such as supply chain disruptions. Stretch goals can also foster short-termism or unethical behavior, as with Wells Fargo’s notorious fake accounts scandal (Witman, Reference Witman2018).

Coercive Management and Supervision

The concept of management is constitutive for the control paradigm. Managers act as enforcers of plans and targets, wielding coercive authority to direct and monitor subordinates. Supervision aims to ensure compliance, with managers serving as gatekeepers of resources and performance evaluators. The model assumes managers have superior insight, but anomalies arise when frontline workers possess better contextual knowledge. Coercive management also demotivates employees, reducing engagement (e.g., Gallup’s data on low and declining employee engagement in hierarchical firms (Harter, 2025)). Micromanagement stifles innovation, as seen in overly controlled R&D teams failing to match agile competitors.

The crisis for coercive management is highlighted by modern systems thinking. Complex systems are not responsive to management; their multiple realizability (i.e., many outcomes are equally probable and none are predictable with certainty) precludes it.

Performance Monitoring and Control

Data is collected to track progress against plans and targets, focusing on operational and market outcomes. Deviations trigger corrective actions, such as process adjustments or resource reallocation, to realign with goals. Monitoring is a feedback mechanism, less influential than strategy or structure but critical for maintaining control. Its reactive nature limits adaptability, because it prioritizes lagging indicators (e.g., sales) over leading indicators (e.g., customer sentiment), creating anomalies when market shifts are missed. Overreliance on quantitative metrics also ignores qualitative insights.

Suppression of Dissent and Enforced Alignment

The paradigmatic organization can discourage dissent, valuing alignment with centralized goals over debate or diversity of thought. Nonperformers or dissenters may be marginalized, disciplined, or removed to maintain cohesion. This cultural element reinforces control, but its stifling effect is a key anomaly. Suppressing dissent limits innovation and adaptability, as alternative perspectives are silenced. Anomalies arise when organizations fail to anticipate disruptions due to groupthink (e.g., GM’s slow response to fuel efficiency trends). Whistleblowers exposing flaws are often ignored, delaying necessary change.

Mechanistic Change Management

Change is treated as a controlled process, managed through structured interventions like reorganizations, process reengineering, or strategic pivots. The organization is viewed as a machine that can be retuned or repaired to restore performance. In this model, change management is a reactive tool, less influential than core structural elements. Its mechanistic assumptions highlight the paradigm’s limits. The assumption is that change is manageable and controllable, but anomalies emerge in complex, emergent environments where linear interventions fail (e.g., Sears’ failed turnaround efforts). It also underestimates cultural and human factors.

Static Job Descriptions and Specialization

Roles and responsibilities tend to be rigidly defined in job descriptions, with employees assigned specialized tasks to maximize efficiency. Cross-functional flexibility is limited, and the job descriptions are tightly enforced. This characteristic reinforces segmentation and hierarchy, locking employees into narrow functions. While job specialization enhances efficiency in stable environments, it hinders innovation in dynamic ones, and creates anomalies when adaptability or interdisciplinary skills are needed. When high return on talent is required, job descriptions and job specialization requirements have the effect of lowering the return by narrowing the guardrails.

Short-Term Financial Focus

The model prioritizes short-term financial metrics, such as quarterly profits or stock price, often at the expense of long-term innovation or sustainability. Decisions are driven by metrics such as shareholder value maximization. This cultural and strategic element shapes planning and target-setting, amplifying anomalies that can undermine long-term resilience. Short-termism can discourage investment in R&D or employee development, as seen in firms cutting costs to meet earnings targets. Anomalies arise when long-term trends disrupt financial models, for example, when conventional automobile manufacturers mistimed the lifestyle switch to everyday affordable EV’S led by startup companies in China. One of the problems caused by this anomaly is the relatively short life of large corporations, as the short-term financial focus triumphs over innovation and idea creation (West, 2018).

A Narrow View of External Stakeholders

The paradigm prioritizes internal goals and shareholder interests over broader stakeholders, such as communities, suppliers, or the environment. External impacts are addressed only when legally or publicly mandated. This worldview underpins strategy and production, creating more anomalies as stakeholder expectations (e.g., corporate social responsibility) grow. Neglecting the broader stakeholder groups can lead to self-defeating reputational and regulatory risks. The paradigm’s inward focus limits its ability to navigate complex ecosystems. The recent trend of consumer backlash against unhealthy ingredients provides an example of forcing food companies into defensive, reactive change.

A Kuhnian Framing of the Management Crisis

Thomas Kuhn’s concept of anomalies – observations, discoveries, contradictions, or failures that cannot be explained or accommodated by the prevailing paradigm’s “normal science” – provides the catalyst for a revolution. In the context of business management, anomalies are the mounting evidence of the old paradigm’s inadequacies, which create a crisis that paves the way for a new worldview.

Collectively, these anomalies create a crisis, in Kuhnian terminology, by demonstrating that the control paradigm cannot address modern challenges of complexity, volatility, and expanded stakeholder demands. They erode confidence in “normal management science,” pushing development toward a new paradigm.

However, in Kuhn’s model, adherents do not renounce the paradigm that has led them into crisis. They defend it. They may make some ad hoc modifications to eliminate some anomalies and counterinstances that are particular sources of trouble, but they don’t concede a new theory. In fact, it may be impossible for them to do so. “Normal management science” contains all the design possibilities, all the data, all the experiments and initiatives, and all the metrics. It also controls the incentives, including financial analyst and investor confidence, the politics of the corporate ladder, peer recognition, and board of directors’ conservatism. The paradigmatic institutions of professorial papers in peer-reviewed journals, articles in the Harvard Business Review, business books and biographies, conferences, and corporate speaking engagements are all bounded within “normal science.” The tools for breakout are unavailable inside the boundary.

To facilitate the change to the new paradigm, “extraordinary research” is called for. Two complementary sources of novelty are required: discovery and invention. Discovery refers to facts that were not known or recognized. Kuhn uses the discovery of oxygen as one of his examples. Discovery is a process, not an event, and takes time. Eventually, oxygen became an important part of the emergence of a new paradigm for chemistry.

The invention of new theories, rather than the discovery of new facts and concepts, usually results in far larger shifts in paradigms, in Kuhn’s view. Novel theories demand more large-scale destruction of the existing paradigm and major shifts in techniques and practice. Copernicus wrote that the Ptolemaic system of astronomy that he proposed to replace had “created only a monster” (Kuhn, Reference Kuhn1962). In the crisis of chemistry that preceded the discovery of oxygen, the existing phlogiston theory had to be abandoned because it did not align with, and could not explain, laboratory experience. A novel theory emerges only after a pronounced failure of the existing paradigm.

The management paradigm has a particularly difficult time generating new theory:

“Business scholars tend to have a skepticism toward theory and theorizing. Many of them argue that there is ‘too much’ theorizing going on in the journals, apparently ignorant of the meaning and use of theory in social science. A field that collects and analyzes data but does not generate theory has accomplished nothing (other than a mass of data). As Ronald Coase once put it (about American institutionalists), ‘Without a theory they had nothing to pass on except a mass of descriptive material waiting for a theory, or a fire.’ This applies to business scholarship as much as to any other field.”

The problem with such theory skepticism is that it stands in the way of developing and adopting good theorizing practices, feeds resistance to refine and challenge the body of theory, and perpetuates a relative inability to recognize good and sound theory.

The transition to the new paradigm is discontinuous: “a reconstruction of the field from new fundamentals, a reconstruction that changes some of the field’s most elementary theoretical generalizations as well as many of its paradigm methods and applications.” The transition requires “extraordinary research” and novel experiments conducted by pioneers and rebels willing to leave prior practice behind in the search for new discoveries and theories. This research and experimentation is accompanied by philosophical analysis as a device for unlocking the new riddles. There is a search for new assumptions. The new experiments take place in “a different world,” with rules that are different from those of the old paradigm. The people and firms who work in the old paradigm are unable to see this new world, don’t understand its new language, and are unable to make the shift.

4 A New Worldview: Self-organizing Systems

An opportunity for a shift in fundamental orientation toward a new worldview for business management is presented by the invention of complex systems theory.

The twentieth-century illusion was to represent the world around us in the form of mechanisms. Everything works as a machine, whether it’s an atom or a leaf or a bridge or a human body or a firm. We try to bring more mechanical order so as to exercise control. In order to understand something, we model it as if it were a machine, and examine its parts and how they work together (Alexander, Reference Alexander1980). The mechanistic approach replaced the humanistic approach.

From George Whistler and Frederick Winslow Taylor onward, an important characteristic of twentieth-century business management theory and practice was the desire to be seen to be applying the tools and methods and objectivity of the natural sciences, and to bring precision, efficiency, and predictability to capitalism’s processes. Some have called this “physics envy,” or what F.A. Hayek, in his famous essay “The Pretence of Knowledge” referred to as “scientism,” an application of scientific methods in inappropriate contexts.

The form of scientific method chosen by business was a kind of reductionism. Taylor favored breaking down complex tasks into smaller, repeatable actions that could be measured, optimized, and standardized. There was “one best way” to complete each task. Like physical objects, workers could be controlled, manipulated, and optimized within a closed system of production. This approach was extended by subsequent management thinkers who believed that business organizations could best be understood and directed through quantitative analysis and rational controls. The reductionist tendencies of classical physics were preferred to the dynamism of human behavior and creativity. Mathematical precision was a desirable goal.

Scientism extended to complex planning and forecasting models for financial outcomes and plan targets. Organizations were treated as mechanical systems to be fine-tuned with the right data inputs. Management relied on numbers and ratios to make decisions. Today, this reliance extends to so-called big data, machine learning, and the use of algorithms.

Interestingly, as management became increasingly captive to its physics envy, science itself began to move on from the classic mechanistic physics paradigm. In the second half of the twentieth century, systems theory and complexity science emerged, offering a new way to understand the world, one that recognized interconnectedness, interdependence, unpredictability, and emergent (i.e., unmanaged) properties of complex systems.

Complex systems consist of a large number of elements that interact in a rich, dynamic, nonlinear fashion constituted by the transfer of information between them, and specifically including feedback loops that stimulate further interactions between the elements. There is a constant flow of energy to maintain system organization, and it can never be in equilibrium; otherwise, it dies. Complex systems have a history; they evolve through time, and their past is co-responsible for their present behavior. Complexity emerges as a result of the patterns of interaction between the elements. Each element in the system is ignorant of the behavior of the system as a whole; it can only respond to local information over a short range (Cilliers, Reference Cilliers1998).

Systems must grapple with a changing environment and respond appropriately, changing internally without the intervention of a designer, a process known as self-organization (Cilliers, Reference Cilliers1998, p.10). In self-organization, “the whole notion of central control becomes suspect” (Cilliers, Reference Cilliers1998, p.12). There can be no rigid program to shape the behavior of the system.

A business firm or corporation is a complex system. Complex systems analysis typically starts at the level of individual agents: elements or parts that are active. They can be individual people, individually identifiable teams in a multi-team organization, individual companies in an economy or industry, and other agentic elements. They interact through processes, rules, and methods that have important properties (sometimes called “affordances”) that evoke certain behavior from agents. The critical point is that the agents are interconnected and interact with one another, as well as with other elements like customers or suppliers, or banks. They respond to feedback. They’re influenced by their history, and system history is vitally important to individuals’ understanding and sense of meaning. The way that they interact becomes the observed behavior of the entire system. It is the interactions that result in complex and unpredictable outcomes, even if each agent is merely adhering to a few simple rules (such as a sales incentive in the case of the Wells Fargo scandal (Witman, Reference Witman2018)).

Systems scientists coined the term “emergence” to refer to these unpredictable outcomes. A result “emerges” from the collective efforts, insights, tendencies, preferences, and interactions between employees, departments, processes, customers, and external stakeholders. No one has a full view of the interactions or how the outcome happens, but it materializes nevertheless. There is no centralized command, and any attempt to impose one must fail.

Complex systems are dynamic, evolving over time without any management. The science identifies feedback loops as a critical aspect of system dynamism. When agents interact, they experience feedback from the system, whether positive or negative, encouraging them to continue or to change, that is, adapt. The continuous adaptation to feedback and the changing environment across all the interacting agents often leads to unpredicted and unpredictable results. Forecasting outcomes or prescribing definitive plans are unrealistic behaviors in this context.

The term “self-organizing” is applied to the emergence of structure and order in complex systems, without any central authority. The information on which agents base their interactions is local and immediate, and whatever structures emerge are the result of decentralized, bottom-up action.

Self-organization is a Kuhnian scientific revolution and paradigm shift. Ann Pendleton-Jullian put it this way:

Pioneering scientists were astute enough to realize that the answers came from certain phenomena that did not fit known explanations, principally those that assumed top-down rules and organizing principles. Instead, they were all observing complex structures, forms and behaviors emerging from bottom-up, self-organizing interactions among different agents. This realization caused a fundamental shift in thinking, a shift so significant that it has revolutionized almost every domain.

Self-organization works because each agent in the system responds to its immediate environment – adapting behavior, learning from feedback, and influencing the behaviors of other agents. Over time, these local interactions accumulate and aggregate to form larger patterns (such as a business culture) that may be sustainable and repeated, while the system remains dynamic and continually changing. The self-organizing system can be both flexible and resilient. It draws on massive numbers of elements “rather than a single intelligent executive branch” (Pendleton-Jullian, 2018, p.170).

An example of self-organization in economics is the price system. There is no top-down management of the price system, yet a pattern emerges that integrates all economic activity at all levels. Knowledge of the relative scarcities of the means of production is dispersed throughout the economy, and the division of knowledge between individuals, without any individual having knowledge of the entire environment of economic conditions, facilitates final market prices through interaction (Hayek, Reference Hayek1948). A general solution emerges as a whole result of evolving exchanges, bargains, trades, side payments, agreements, compromises, and contracts (Buchanan, Reference Buchanan1979). The system evolves toward a solution, even while the individuals who make up the system are struggling with discovery and understanding (Boettke, Caceres, & Martin, Reference Boettke, Caceres, Martin, Frantz and Leeson2013).

Interaction as Capital

Interaction, between internal elements and with the external environment, is critical for self-organizing systems. Without interaction, self-organization cannot take place (Collier, Reference Collier2004). The question of who should interact with whom, and when and how, becomes the challenge for the firm as a self-organizing complex adaptive system.

The industrial revolution metaphor of machines and linear processes that led to command and control, hierarchies, rules, plans, and goals as management ideals is no longer valid. Complex adaptive systems thinking is replacing traditional management thinking. Decentralization, perpetual novelty, adaptation, variety, and experimentation become the new perspectives. The dominant metaphor for firms as complex adaptive systems is exploration and exploitation (Axelrod, 2000), that is, experimenting and adapting on the way toward discovering new patterns of marketplace effectiveness, and then, once such a pattern tests well for repeatability, expanding its use until the effectiveness diminishes and a new pattern takes its place. This simultaneous explore and exploit capacity has been referred to as organizational ambidexterity (Tushman, 2013) and identified as one of the characteristics of breakaway growth in Silicon Valley companies (Steiber, 2024).

The mindset is humble, there is no attempt at prediction, and no seeking control. The dimensions are horizontal, not vertical, and the patterns are networks not hierarchies.

The primary variable for firms aiming to harness complexity is the nature of interactions and interaction patterns both within the firm and with the market and the environment – interaction as capital. All outcomes arise from the interactions of a system’s agents with each other and with artifacts and with the environment. Just like physical and financial capital, interaction capital can deliver returns on the investments made in it. And, also just like physical and financial capital, interaction capital has a combination and recombination aspect resulting in new patterns that can lead to breakthrough differentiation.

Robert Putnam (Putnam, Reference Putnam1993) identified three emergent benefits of interaction capital: (1) generalized reciprocity – people enjoy working together, commit to helping each other, and place trust in one another; (2) trust becomes amplified as dense interaction rewards the cultivation of reputation by each individual agent; (3) a collaborative culture emerges as past successes at collaboration serve as a template for future collaboration.

Interactions Orchestrated by Constraints

In a firm that is a complex adaptive system, the interactions must find unity, a coordination pattern that constitutes a coherent systemwide dynamic and a distinctive interactional type. This coherence is realized through constraints – a term that systems scientists use to indicate not restriction or limitation, but channeling, guiding, and facilitating the energy in a system. Constraints can be cultural norms, ethical values, protocols mental models, conceptual frameworks, feedback loops, algorithms, and many more. Constraints can coexist in a variety of forms and dimensions; Alicia Juarrero introduced the idea of a constraint regime (Juarrero, Reference Juarrero2023), a distinctive combination of constraints that can result in the emergence of novel properties. Every firm has a distinctive constraint regime.

Importantly, constraints are not causes, and they are not deterministic. But they do give shape to the possibility space of what can happen, what’s likely to happen, and when it can happen. And they also shape the view of individuals located in that space – what they can see as possibilities. A system’s events play out differently when constraints are different.

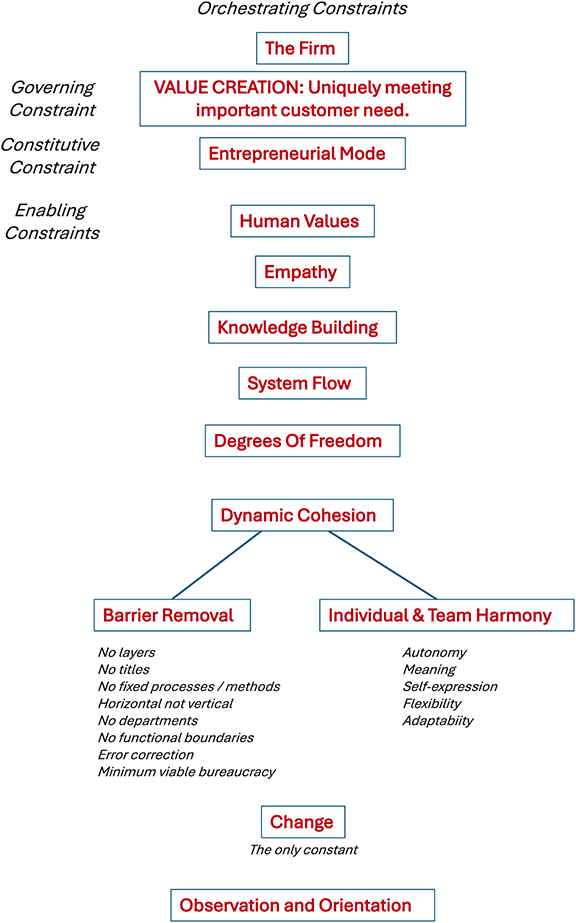

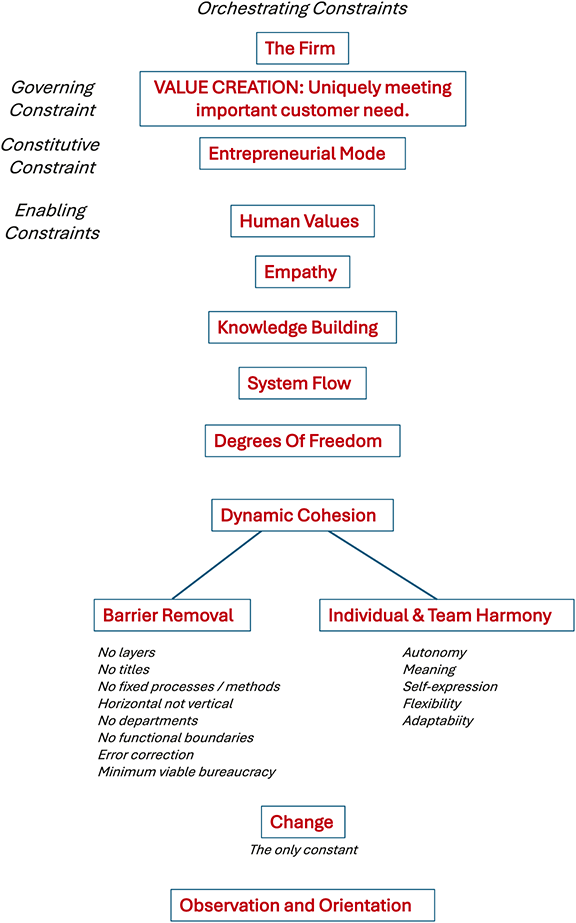

Therefore, in the new paradigm, it’s important for a firm to be thoughtful about constraints. They can be classified into three types:

Constitutive Constraints: These define the essence and identity of the organization. They are foundational principles that give the organization its unique character and purpose and shape what it can become. They might include:

Core Values and Mission: These give contours to the fundamental purpose and ethical foundation of the organization. They are guiding principles for the emergence of a company’s culture, and they influence its strategic direction.

Organizational Framework: Choosing a flat structure with defined departments and roles over a flat network shapes the interactions within the framework and is constitutive of how the company operates and its interaction capital.

Brand Identity: A company’s brand is not just a marketing artifact. It carries distinct characteristics including reputation, trust, image, and positioning in the market. These aspects are fundamental to how the company is perceived both internally and externally. These perceptions are important constraints affecting the firm’s possibility space.

Strategic consistency, cultural integrity, and long-term vision stem from constitutive constraints, helping a firm stay true to its purpose while navigating changes and uncertainties.

Governing Constraints: These are the rules, norms, and limitations that stabilize the overall behavior of a system. In a business context, they are the regulatory, financial, and organizational policies that define the boundaries of the system within which a company operates. They maintain stability and ensure compliance. They might include budget limitations or rigid strategic objectives. Governing constraints ensure that a company adheres to legal standards, stays financially viable, and moves in a direction aligned with its long-term goals, but they can be stifling of innovation and adaptability.

Enabling Constraints: These are the facilitators of flexibility, innovation, and adaptation within the system. They can empower individuals and teams to explore new ideas and approaches, adjusting the explore–exploit balance. They can encourage creativity while maintaining coherence with the firm’s overall purpose.

They can include degrees of decentralization, relaxed role descriptions, qualitative rather than quantitative assessments, innovation incubation, experimentation, and relaxation of risk management. Departments and teams can set their own project goals and respond to market changes and the results of experiments rapidly without bureaucratic reporting and approval requirements. Enabling constraints establish a safe environment for exploration, including acceptance of failure and error in the context of eventual success. Under the right enabling constraints, established processes can be modified, and new challenges or opportunities or newly identified customer needs can be addressed with new responses. The culture becomes one of enthusiasm for adaptability and continuous improvement.

The key is to establish a dynamic interplay – a constraint regime – where constitutive constraints provide foundational solidity and clarity of shared purpose, governing constraints provide dynamic stability for adaptive exploitation, and enabling constraints foster innovation.

Cohesion

Cohesion is the ideal state toward which a system of constraints evolves. Cohesion is the emergent unity of all system elements such that all their energy and mass are applied to the system’s end or purpose, without any waste. Cohesion is dynamic not static, and not necessarily smooth, since external fluctuations and perturbations are unpredictable. For a business firm, the end is value creation, and cohesion is achieved when all the people and processes are applied to that end. A distinctive and sustained coherence is the essence of the differentiated firm that fits into an ecosystem in a distinctive manner to create new value.