1. Introduction

Taylor dispersion plays a crucial role in the transport and mixing of passive scalars (such as temperature or concentration) in fluid flows, with applications spanning various scientific and engineering disciplines. Originally studied by Taylor (Reference Taylor1953), it describes how a solute in shear flow undergoes enhanced mixing due to the interplay between advection and diffusion. Classical Taylor dispersion theory has been widely utilised, as it enables dimensional reduction by approximating the governing equations with fewer independent variables (Young & Jones Reference Young and Jones1991; Ding Reference Ding2023; Teng, Rallabandi & Ault Reference Teng, Rallabandi and Ault2023; David et al. Reference David, Hester, Xu and Aurnou2024; Guan & Chen Reference Guan and Chen2024). However, since Taylor dispersion is an asymptotic approximation valid at long times, a fundamental question arises: At what time scale does this approximation become valid?

To address this question, it is useful to examine the evolution of the scalar field in a straight channel with uniform cross-section, from its initial introduction into the flow to its eventual homogenisation. This process can be characterised by three distinct time scales: dispersion, longitudinal normality and transverse uniformity, which we outline below.

In the early stage after the solute is injected into the channel, it is primarily advected along streamlines and undergoes stretching. During this stage, advection dominates while diffusion begins to play a role, leading to a complex evolution of the scalar field Taghizadeh, Valdés-Parada & Wood (Reference Taghizadeh, Valdés-Parada and Wood2020), Camassa et al. (Reference Camassa, McLaughlin and Viotti2010b ). The first significant time scale arises when the variance of the solute concentration begins to grow linearly in time, marking the onset of Taylor dispersion Aris (Reference Aris1956), Camassa et al. (Reference Camassa, Lin and McLaughlin2010a ). This signals that diffusion has started to act in concert with the background flow to redistribute the solute along the channel. At this stage, the rate of variance growth exceeds that of pure molecular diffusion due to the coupling between shear-induced advection and transverse diffusion. One might expect that the scalar field could already be described by a diffusion equation, since the solution of a diffusion equation is a Gaussian function with linearly increasing variance. However, at this stage, transverse variations in the scalar field persist, and the cross-sectionally averaged scalar field may still deviate from a Gaussian profile, exhibiting skewness that depends on the channel geometry and shear flow characteristics Aminian et al. (Reference Aminian, Bernardi, Camassa, Harris and McLaughlin2016).

As molecular diffusion continues, the cross-sectionally averaged scalar field approaches a Gaussian distribution, marking the second time scale. Once this stage is reached, the evolution of the cross-sectionally averaged scalar field can be effectively described by a one-dimensional diffusion equation with an enhanced diffusivity Chatwin (Reference Chatwin1970). We refer to this governing equation as the effective equation and to the enhanced diffusion coefficient as the effective diffusivity. However, even at this stage, the solute concentration may still exhibit non-uniformity across the channel cross-section.

The third and final time scale corresponds to the attainment of transverse uniformity across the channel cross-section. At this point, diffusion has sufficiently spread the solute so that the concentration becomes nearly uniform across the cross-section. Wu & Chen (Reference Wu and Chen2014) demonstrated that this time scale can be up to ten times larger than that for longitudinal normality, highlighting the extended duration required for complete transverse homogenisation. At this stage, the whole scalar field can be well approximated by a one-dimensional effective equation.

How do these time scales depend on physical parameters? The enhanced mixing in Taylor dispersion arises from the diffusion of concentration variations across the channel’s cross-section. The time scale for this enhanced mixing is related to the rate at which these variations decay into a uniform concentration through diffusion. Dimensional analysis shows that the diffusion time scale is

![]() $L^2/\kappa$

, where

$L^2/\kappa$

, where

![]() $L$

is the characteristic length scale of the channel cross-section and

$L$

is the characteristic length scale of the channel cross-section and

![]() $\kappa$

is the molecular diffusivity. Interestingly, many studies of Taylor dispersion in a straight channel with flat boundaries show that the variance starts to increase linearly at an earlier time, approximately

$\kappa$

is the molecular diffusivity. Interestingly, many studies of Taylor dispersion in a straight channel with flat boundaries show that the variance starts to increase linearly at an earlier time, approximately

![]() $0.1L^2/\kappa$

, for steady shear flows in various geometries, such as parallel plate channels Camassa et al. (Reference Camassa, Lin and McLaughlin2010a

), circular pipes Barton (Reference Barton1983) and even time-dependent flows Vedel & Bruus (Reference Vedel and Bruus2012), Vedel, Hovad & Bruus (Reference Vedel, Hovad and Bruus2014). The variance evolution can be computed exactly using the method of moments, first proposed by Aris (Reference Aris1956). These calculations refine the dispersion time scale to

$0.1L^2/\kappa$

, for steady shear flows in various geometries, such as parallel plate channels Camassa et al. (Reference Camassa, Lin and McLaughlin2010a

), circular pipes Barton (Reference Barton1983) and even time-dependent flows Vedel & Bruus (Reference Vedel and Bruus2012), Vedel, Hovad & Bruus (Reference Vedel, Hovad and Bruus2014). The variance evolution can be computed exactly using the method of moments, first proposed by Aris (Reference Aris1956). These calculations refine the dispersion time scale to

![]() $L^2/(\kappa \lambda )$

, where

$L^2/(\kappa \lambda )$

, where

![]() $\lambda$

is the smallest non-zero eigenvalue of the Laplacian on the cross-section domain. For a parallel plate channel,

$\lambda$

is the smallest non-zero eigenvalue of the Laplacian on the cross-section domain. For a parallel plate channel,

![]() $L$

is the gap width,

$L$

is the gap width,

![]() $\lambda = \pi ^2$

and

$\lambda = \pi ^2$

and

![]() $1/\lambda \approx 0.1$

. For a circular pipe with radial symmetry,

$1/\lambda \approx 0.1$

. For a circular pipe with radial symmetry,

![]() $L$

is the radius,

$L$

is the radius,

![]() $\lambda = 14.682$

(the square of the roots of

$\lambda = 14.682$

(the square of the roots of

![]() $J_1(x)$

, the Bessel function of the first kind of order one), yielding

$J_1(x)$

, the Bessel function of the first kind of order one), yielding

![]() $1/\lambda \approx 0.0681$

.

$1/\lambda \approx 0.0681$

.

In addition to studies focusing on the variance, others investigate the approximation of the entire scalar field. Mercer & Roberts (Reference Mercer and Roberts1990), Watt & Roberts (Reference Watt and Roberts1995) demonstrated that the scalar field converges exponentially to the centre manifold of the system, and the rate of this convergence is governed by the Laplacian eigenvalue. This implies that the time scale for achieving longitudinal normality is also closely related to

![]() $L^2/(\kappa \lambda )$

. Stokes & Barton (Reference Stokes and Barton1990), Phillips & Kaye (Reference Phillips and Kaye1996) applied a Laplace transform in time and a Fourier transform in the longitudinal direction to derive an integral representation of the concentration field, enabling accurate asymptotic expansions at both short and long times. Using a representation that combines the Fourier transform with eigenfunction expansion, Ding & McLaughlin (Reference Ding and McLaughlin2022b

) derived an effective equation and effective diffusivity for a family of stochastic shear flows, demonstrating that the time scale is governed by the Laplacian eigenvalues associated with the random scalar field.

$L^2/(\kappa \lambda )$

. Stokes & Barton (Reference Stokes and Barton1990), Phillips & Kaye (Reference Phillips and Kaye1996) applied a Laplace transform in time and a Fourier transform in the longitudinal direction to derive an integral representation of the concentration field, enabling accurate asymptotic expansions at both short and long times. Using a representation that combines the Fourier transform with eigenfunction expansion, Ding & McLaughlin (Reference Ding and McLaughlin2022b

) derived an effective equation and effective diffusivity for a family of stochastic shear flows, demonstrating that the time scale is governed by the Laplacian eigenvalues associated with the random scalar field.

While the theory for channels with flat walls is well developed, real-world systems often involve more complex geometries, such as channels with periodically varying cross-sections (Roggeveen, Stone & Kurzthaler Reference Roggeveen, Stone and Kurzthaler2023). These geometries are crucial in applications like passive microfluidic mixers and flow through porous media. Micro passive mixers enable rapid homogenisation, essential for chemical and biological processes at the microscale. Specially designed channel boundaries can enhance mixing by inducing chaotic advection (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Stremler, Sharp, Olsen, Santiago, Adrian, Aref and Beebe2000; Stroock et al. Reference Stroock, Dertinger, Ajdari, Mezic, Stone and Whitesides2002; Stone, Stroock & Ajdari Reference Stone, Stroock and Ajdari2004; Oevreeide et al. Reference Oevreeide, Zoellner, Mielnik and Stokke2020), leading to faster homogenisation compared with shear-driven mixing in straight channels. In addition, a sinusoidally varying channel radius serves as an idealised model for flow through porous media, where constrictions and expansions mimic pore throats and pore bodies (Richmond et al. Reference Richmond, Perkins, Scheibe, Lambert and Wood2013; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Xiao, Aquino, Dentz and Wang2024). In both cases, generalised Taylor dispersion theory provides a framework for estimating the longitudinal dispersion coefficient and approximating the scalar field (Brenner Reference Brenner1980; Hoagland & Prud’Homme Reference Hoagland and Prud’Homme1985; Amaral Souto & Moyne Reference Amaral Souto and Moyne1997; DeGroot & Straatman Reference DeGroot and Straatman2011, Haugerud, Linga & Flekkøy Reference Haugerud, Linga and Flekkøy2022). Thus, determining the characteristic time for the validity of Taylor dispersion theory is of fundamental importance.

Several numerical studies have attempted to estimate the characteristic time scale. For instance, Bouquain et al. (Reference Bouquain, Méheust, Bolster and Davy2012) investigated sinusoidally varying channels and estimated the characteristic time by fitting the numerically computed time evolution of the normalised dispersion coefficient to an exponential relaxation function. Haugerud et al. (Reference Haugerud, Linga and Flekkøy2022) investigated channels with periodic square boundary roughness. Non-flat boundaries can induce circulation regions that trap particles and affect the dispersion process. Haugerud et al. (Reference Haugerud, Linga and Flekkøy2022) showed that particle residence times in these circulation regions are directly related to the characteristic mixing time. However, these approaches rely on simulating the scalar field over the entire domain, which is computationally expensive, particularly in geometries with complex boundaries. Despite valuable insights, a rigorous and systematic theoretical framework for estimating mixing times in such domains remains an open challenge.

As mentioned earlier, in the case of scalar transport in a channel with flat boundaries, the approach combining the Fourier transform in the longitudinal direction with eigenfunction expansion has been successful in analysing characteristic times. However, two main challenges arise when generalising this method to a channel with periodically varying cross-sections. First, the Fourier transform in the axial direction is no longer applicable due to the complex geometry. Second, while the flow may be periodic and solvable within a unit cell, the scalar field itself is not periodic. As a result, the eigenfunctions of the advection--diffusion operator must be defined over the entire domain rather than a single cell. Since exact solutions to this eigenvalue problem are typically unavailable, numerical methods are required. However, solving on an infinite domain poses computational challenges, making this approach impractical.

To overcome the challenges of solving the advection--diffusion equation in a periodic channel, we introduce a Floquet–Bloch-type eigenfunction representation that separates the non-periodic and periodic components of the scalar field. This reduces the eigenvalue problem from the full domain to a simpler one defined on a single unit cell. These eigenfunctions form a complete basis for square-integrable functions, enabling an integral representation of the scalar field. This representation highlights the mode governing the system’s slow dynamics, leading to a reduced model whose difference from the full system decays exponentially in time. This reduced model allows us to rigorously determine the time scale over which Taylor dispersion theory remains valid. By applying the method of steepest descent to the integral representation of the slow manifold, we derive the long-time asymptotic expansion of the scalar field. This approach reveals the structure of the advection--diffusion solution in a periodic channel and clarifies the relationships among key dispersion time scales: longitudinal normality, transverse uniformity and effective dispersion. The dominant time scale depends solely on the flow and domain geometries and can be computed from the solution within a single unit cell. Together, these results offer a rigorous and systematic framework for estimating mixing time scales in complex geometries.

This paper is organised as follows. In § 2 we first formulate the governing equations for the scalar field and fluid flow and outline the non-dimensionalisation process. We then define the eigenvalue problem and present the eigenfunction expansion of the scalar field. Based on this, we identify the system’s slow manifold and derive the long-time asymptotic expansion of the scalar field. Next, we discuss the relationship between different time scales in the Taylor dispersion problem. Section 3 examines the characteristic time for the scalar field to converge to the slow manifold through several examples. In § 4 we briefly discuss extending the proposed method to porous media. In § 5 we summarise our findings and explore potential directions for future research. Appendix A provides the perturbation calculations for the small-wavenumber expansion of the eigenfunctions, while Appendix B details the numerical methods used in this study.

2. Governing equation and asymptotic analysis

We consider a straight channel domain of length

![]() $L$

with a periodically varying cross-section, defined as

$L$

with a periodically varying cross-section, defined as

where the

![]() $x$

direction is the longitudinal axis of the channel and

$x$

direction is the longitudinal axis of the channel and

![]() $\varOmega _{c}(x) \subset \mathbb{R}^{d}$

denotes the cross-section of the channel, which depends on

$\varOmega _{c}(x) \subset \mathbb{R}^{d}$

denotes the cross-section of the channel, which depends on

![]() $x$

. We assume that

$x$

. We assume that

![]() $\varOmega _{c}(x)$

is periodic in

$\varOmega _{c}(x)$

is periodic in

![]() $x$

with a period

$x$

with a period

![]() $L_{p}$

. We often focus on the case of an infinitely long channel, denoting it as

$L_{p}$

. We often focus on the case of an infinitely long channel, denoting it as

![]() $\varOmega = \varOmega (\infty )$

for simplicity. The volume of the channel is represented as

$\varOmega = \varOmega (\infty )$

for simplicity. The volume of the channel is represented as

![]() $|\varOmega (L)|$

, while the average cross-sectional area is given by

$|\varOmega (L)|$

, while the average cross-sectional area is given by

![]() $|\varOmega _{c}| = {|\varOmega (L_{p})|}/{L_{p}}$

. The simplest case is a domain bounded by two wavy walls:

$|\varOmega _{c}| = {|\varOmega (L_{p})|}/{L_{p}}$

. The simplest case is a domain bounded by two wavy walls:

![]() $\varOmega = \left \{ (x, y) \,|\, x \in \mathbb{R}, \, h_{1}(x) \leqslant y \leqslant h_{2}(x) \right \}$

, where

$\varOmega = \left \{ (x, y) \,|\, x \in \mathbb{R}, \, h_{1}(x) \leqslant y \leqslant h_{2}(x) \right \}$

, where

![]() $h_{1}(x)$

and

$h_{1}(x)$

and

![]() $h_{2}(x)$

share the same period

$h_{2}(x)$

share the same period

![]() $L_{p}$

. In this scenario, the average cross-sectional area is calculated as

$L_{p}$

. In this scenario, the average cross-sectional area is calculated as

![]() $|\varOmega _{c}| =( {1}/{L_{p}} )\int _{0}^{L_{p}} (h_{2}(x) - h_{1}(x)) \, \mathrm{d} x$

. Beyond this type of domain, practical examples include axisymmetric channels (Chang & Santiago Reference Chang and Santiago2023) and curved microfluidic channels (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Stremler, Sharp, Olsen, Santiago, Adrian, Aref and Beebe2000; Stroock et al. Reference Stroock, Dertinger, Ajdari, Mezic, Stone and Whitesides2002).

$|\varOmega _{c}| =( {1}/{L_{p}} )\int _{0}^{L_{p}} (h_{2}(x) - h_{1}(x)) \, \mathrm{d} x$

. Beyond this type of domain, practical examples include axisymmetric channels (Chang & Santiago Reference Chang and Santiago2023) and curved microfluidic channels (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Stremler, Sharp, Olsen, Santiago, Adrian, Aref and Beebe2000; Stroock et al. Reference Stroock, Dertinger, Ajdari, Mezic, Stone and Whitesides2002).

The passive scalar is governed by the advection--diffusion equation with no-flux boundary conditions, which takes the form

where

![]() $\kappa$

is the diffusivity and

$\kappa$

is the diffusivity and

![]() $c_{I}$

is the initial condition, which is assumed to be non-negative. The vector

$c_{I}$

is the initial condition, which is assumed to be non-negative. The vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{n} = (n_{x}, n_{1}, \ldots , n_{d})$

denotes the outward normal to the boundary and

$\boldsymbol{n} = (n_{x}, n_{1}, \ldots , n_{d})$

denotes the outward normal to the boundary and

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

is the velocity field. The theory developed in this paper can be readily generalised to the case where

$\boldsymbol{u}$

is the velocity field. The theory developed in this paper can be readily generalised to the case where

![]() $\kappa$

is a spatially periodic function, i.e.

$\kappa$

is a spatially periodic function, i.e.

![]() $\kappa = \kappa (x, \boldsymbol{y})$

, but for simplicity, we assume it to be constant throughout this work. To ensure mass conservation, we assume that the velocity field is incompressible and satisfies the no-flux boundary condition. Additionally, we consider flows that are periodic in the longitudinal direction of the channel, with a fundamental period

$\kappa = \kappa (x, \boldsymbol{y})$

, but for simplicity, we assume it to be constant throughout this work. To ensure mass conservation, we assume that the velocity field is incompressible and satisfies the no-flux boundary condition. Additionally, we consider flows that are periodic in the longitudinal direction of the channel, with a fundamental period

![]() $L_{p}$

. While the theoretical results developed here apply to any velocity field satisfying these assumptions, the simulations presented use velocity fields governed by the Navier–Stokes equations. For a homogeneous fluid, the velocity field

$L_{p}$

. While the theoretical results developed here apply to any velocity field satisfying these assumptions, the simulations presented use velocity fields governed by the Navier–Stokes equations. For a homogeneous fluid, the velocity field

![]() $\boldsymbol{u} = (u, \boldsymbol{v})$

satisfies the Navier–Stokes equations:

$\boldsymbol{u} = (u, \boldsymbol{v})$

satisfies the Navier–Stokes equations:

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &\partial _{t} u + u \partial _{x} u + \boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} u = -\frac {1}{\rho _{0}} \partial _{x} p + \nu \big ( \partial _{x}^{2} u + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}} u \big )+f_{x}, \\&\partial _{t} v_{i} + u \partial _{x} v_{i} + \boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} v_{i} = -\frac {1}{\rho _{0}} \partial _{y_{i}} p + \nu \big ( \partial _{x}^{2} v_{i} + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}} v_{i} \big )+f_{y,i}, \quad i = 1, \ldots , d, \\&\partial _{x} u + \boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v} = 0, \quad \left . \boldsymbol{u} \right |_{w\textit{all}} = 0. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &\partial _{t} u + u \partial _{x} u + \boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} u = -\frac {1}{\rho _{0}} \partial _{x} p + \nu \big ( \partial _{x}^{2} u + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}} u \big )+f_{x}, \\&\partial _{t} v_{i} + u \partial _{x} v_{i} + \boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} v_{i} = -\frac {1}{\rho _{0}} \partial _{y_{i}} p + \nu \big ( \partial _{x}^{2} v_{i} + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}} v_{i} \big )+f_{y,i}, \quad i = 1, \ldots , d, \\&\partial _{x} u + \boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v} = 0, \quad \left . \boldsymbol{u} \right |_{w\textit{all}} = 0. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

Here

![]() $u$

is the fluid velocity in the longitudinal

$u$

is the fluid velocity in the longitudinal

![]() $x$

direction,

$x$

direction,

![]() $v_i$

is the fluid velocity aligned with the

$v_i$

is the fluid velocity aligned with the

![]() $y_i$

directions,

$y_i$

directions,

![]() $\boldsymbol{v} = (v_{1}, \ldots , v_{d})$

,

$\boldsymbol{v} = (v_{1}, \ldots , v_{d})$

,

![]() $p$

is the pressure,

$p$

is the pressure,

![]() $\rho _{0}$

is the fluid density and

$\rho _{0}$

is the fluid density and

![]() $\nu$

is the fluid kinematic viscosity. The subscript

$\nu$

is the fluid kinematic viscosity. The subscript

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

denotes quantities related to the coordinates in the cross-section, where

$\boldsymbol{y}$

denotes quantities related to the coordinates in the cross-section, where

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}_{\boldsymbol{y}} = (n_{1}, \ldots , n_{d})$

,

$\boldsymbol{n}_{\boldsymbol{y}} = (n_{1}, \ldots , n_{d})$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} = (\partial _{y_{1}}, \ldots , \partial _{y_{d}})$

and

$\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} = (\partial _{y_{1}}, \ldots , \partial _{y_{d}})$

and

![]() $\Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}} = \sum _{i=1}^{d} \partial _{y_{i}}^{2}$

. The forcing terms

$\Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}} = \sum _{i=1}^{d} \partial _{y_{i}}^{2}$

. The forcing terms

![]() $f_{x}$

and

$f_{x}$

and

![]() $f_{y_{i}}$

represent external forces. In pressure-driven flow,

$f_{y_{i}}$

represent external forces. In pressure-driven flow,

![]() $f_{x}$

is a constant while

$f_{x}$

is a constant while

![]() $f_{y_{i}} = 0$

. If the domain boundary is periodic, it induces periodicity in the flow, as illustrated in figure 1, satisfying our assumption about the velocity field structure. While a transient region exists near the inlet, the flow converges exponentially to the periodic state (Feppon Reference Feppon2025). Therefore, our analysis focuses on the fully developed periodic flow.

$f_{y_{i}} = 0$

. If the domain boundary is periodic, it induces periodicity in the flow, as illustrated in figure 1, satisfying our assumption about the velocity field structure. While a transient region exists near the inlet, the flow converges exponentially to the periodic state (Feppon Reference Feppon2025). Therefore, our analysis focuses on the fully developed periodic flow.

Figure 1. A pressure-driven flow passes from left to right through a channel with periodically varying cross-sections. Two unit cells of the periodic pattern are displayed. The velocity magnitude in the recirculating region is about one-tenth of that in the main flow stream; therefore, the arrow lengths have been scaled to enhance the visibility of the recirculation. The flow field was obtained using FreeFem++ with the algorithm described in Appendix B.

2.1. Non-dimensionalisation

We denote the characteristic length scale of the channel cross-section as

![]() $L_{y}$

. We then proceed with the following change of variables for non-dimensionalisation:

$L_{y}$

. We then proceed with the following change of variables for non-dimensionalisation:

Equation (2.2) becomes

and (2.3) becomes

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & \frac {U \kappa }{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {t}}\tilde {u}+ \frac {U^{2}}{L_{y}} \tilde {u} \partial _{\tilde {x}}\tilde {u} + \frac {U^{2}}{L_{y}} \tilde {\boldsymbol{v}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\partial _{\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}}\tilde {u}= -\frac {\nu U}{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {x}}\tilde {p} + \nu U \left ( \frac {1}{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {x}}^{2}\tilde {u} + \frac {1}{L_{y}^{2}} \Delta _{\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}}^{2}\tilde {u} \right )\!,\\ & \frac {U \kappa }{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {t}}\tilde {v}_{i}+ \frac {U^{2}}{L_{y}} \tilde {u} \partial _{\tilde {x}}\tilde {v}_{i} + \frac {U^{2}}{L_{y}} \tilde {\boldsymbol{v}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\partial _{\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}}\tilde {v}_{i}= -\frac {\nu U}{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {y}_{i}}\tilde {p} + \nu U \left ( \frac {1}{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {x}}^{2}\tilde {v}_{i} + \frac {1}{L_{y}^{2}} \Delta _{\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}}^{2}\tilde {v}_{i} \right )\!,\\ &\frac {U}{L_{y}}\partial _{\tilde {x}}\tilde {u}+\frac {U}{L_{y}}\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{v}}=0. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & \frac {U \kappa }{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {t}}\tilde {u}+ \frac {U^{2}}{L_{y}} \tilde {u} \partial _{\tilde {x}}\tilde {u} + \frac {U^{2}}{L_{y}} \tilde {\boldsymbol{v}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\partial _{\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}}\tilde {u}= -\frac {\nu U}{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {x}}\tilde {p} + \nu U \left ( \frac {1}{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {x}}^{2}\tilde {u} + \frac {1}{L_{y}^{2}} \Delta _{\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}}^{2}\tilde {u} \right )\!,\\ & \frac {U \kappa }{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {t}}\tilde {v}_{i}+ \frac {U^{2}}{L_{y}} \tilde {u} \partial _{\tilde {x}}\tilde {v}_{i} + \frac {U^{2}}{L_{y}} \tilde {\boldsymbol{v}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\partial _{\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}}\tilde {v}_{i}= -\frac {\nu U}{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {y}_{i}}\tilde {p} + \nu U \left ( \frac {1}{L_{y}^{2}} \partial _{\tilde {x}}^{2}\tilde {v}_{i} + \frac {1}{L_{y}^{2}} \Delta _{\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}}^{2}\tilde {v}_{i} \right )\!,\\ &\frac {U}{L_{y}}\partial _{\tilde {x}}\tilde {u}+\frac {U}{L_{y}}\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{v}}=0. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

Now the velocity field

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}$

has the dimensionless fundamental period

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}$

has the dimensionless fundamental period

![]() $\tilde {L}_{p} = L_{p} / L_{y}$

. After dropping the tilde, we obtain the equation for the scalar field

$\tilde {L}_{p} = L_{p} / L_{y}$

. After dropping the tilde, we obtain the equation for the scalar field

and the equation for the velocity field

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &\frac {1}{{Sc}}\partial _{t}u+ {\textit{Re}}\left ( u \partial _{x}u + \boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}}u \right )= -\partial _{x}p + \big ( \partial _{x}^{2}u + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}}u \big ),\\&\frac {1}{{Sc}}\partial _{t}v_{i}+ {\textit{Re}} \left ( u \partial _{x}v_{i} + \boldsymbol{v}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}}v_{i} \right )= - \partial _{y_{i}}p + \big ( \partial _{x}^{2}v_{i} + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}}v_{i} \big ),\\&\partial _{x}u+\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}=0,\quad \left . \boldsymbol{u} \right |_{w\textit{all}}=0, \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &\frac {1}{{Sc}}\partial _{t}u+ {\textit{Re}}\left ( u \partial _{x}u + \boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}}u \right )= -\partial _{x}p + \big ( \partial _{x}^{2}u + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}}u \big ),\\&\frac {1}{{Sc}}\partial _{t}v_{i}+ {\textit{Re}} \left ( u \partial _{x}v_{i} + \boldsymbol{v}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}}v_{i} \right )= - \partial _{y_{i}}p + \big ( \partial _{x}^{2}v_{i} + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}}v_{i} \big ),\\&\partial _{x}u+\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}=0,\quad \left . \boldsymbol{u} \right |_{w\textit{all}}=0, \end{aligned} \end{equation}

where we have defined the Pélect number

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}={L_{y}U}/{\kappa }$

, the Reynolds number

${\textit{Pe}}={L_{y}U}/{\kappa }$

, the Reynolds number

![]() ${\textit{Re}}={ L_{y}U}/{\nu }$

and the Schmidt number

${\textit{Re}}={ L_{y}U}/{\nu }$

and the Schmidt number

![]() ${Sc}={\nu }/{ \kappa }$

. Unless otherwise noted, all quantities in the subsequent sections, including

${Sc}={\nu }/{ \kappa }$

. Unless otherwise noted, all quantities in the subsequent sections, including

![]() $\tilde {L}_{p}$

, are taken to be dimensionless, and for simplicity, we drop the tilde.

$\tilde {L}_{p}$

, are taken to be dimensionless, and for simplicity, we drop the tilde.

2.2. Variance and effective longitudinal diffusivity

Since the solution of the advection–diffusion equation in a channel domain converges to a Gaussian distribution at long times, the variance serves as a key quantity for characterising the solution. In this section we present its definition.

As the following discussion involves complex-valued functions, we define the inner product as

\begin{equation} \left \langle f, g \right \rangle = \frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|} \int \limits _{\varOmega } f(x, \boldsymbol{y}) g^{*}(x, \boldsymbol{y}) \,\mathrm{d}x \,\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left \langle f, g \right \rangle = \frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|} \int \limits _{\varOmega } f(x, \boldsymbol{y}) g^{*}(x, \boldsymbol{y}) \,\mathrm{d}x \,\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y}, \end{equation}

where the asterisk denotes the complex conjugate. For simplicity, we use the notation

![]() $\left \langle u \right \rangle$

as a shorthand for

$\left \langle u \right \rangle$

as a shorthand for

![]() $\left \langle u, 1 \right \rangle$

.

$\left \langle u, 1 \right \rangle$

.

Since the solution approaches a Gaussian function at long times, its variance is given by

Then the effective longitudinal diffusivity is defined as

In some studies on time-dependent flows, the term

![]() $({1}/{2}) \partial _{t} \text{Var}(t)$

is directly defined as the effective diffusivity, as seen in Vedel & Bruus (Reference Vedel and Bruus2012), Vedel et al. (Reference Vedel, Hovad and Bruus2014), Ding & McLaughlin (Reference Ding and McLaughlin2023).

$({1}/{2}) \partial _{t} \text{Var}(t)$

is directly defined as the effective diffusivity, as seen in Vedel & Bruus (Reference Vedel and Bruus2012), Vedel et al. (Reference Vedel, Hovad and Bruus2014), Ding & McLaughlin (Reference Ding and McLaughlin2023).

2.3. Eigenfunction expansion

Since the advection--diffusion equation (2.2) is linear, the eigenfunction expansion of the scalar field is a convenient tool for analysing scalar dynamics. The eigenvalue

![]() $\lambda$

and eigenfunction

$\lambda$

and eigenfunction

![]() $\phi$

satisfy the following equation:

$\phi$

satisfy the following equation:

It forms a basis for square-integrable functions defined on the infinite channel domain that satisfy the no-flux boundary condition

![]() $\left . n_{x} \partial _{x} \phi + \partial _{\boldsymbol{n}_{y}} \phi \right |_{w\textit{all}} = 0$

.

$\left . n_{x} \partial _{x} \phi + \partial _{\boldsymbol{n}_{y}} \phi \right |_{w\textit{all}} = 0$

.

There are three properties of eigenvalues and eigenfunctions that will be used later. First, given that the velocity field is real,

![]() $\lambda ^{*}$

is also an eigenvalue and

$\lambda ^{*}$

is also an eigenvalue and

![]() $\phi ^{*}$

is the associated eigenfunction. Second, the real part of the eigenvalue is non-negative (see the proof in Appendix A.1). Third,

$\phi ^{*}$

is the associated eigenfunction. Second, the real part of the eigenvalue is non-negative (see the proof in Appendix A.1). Third,

![]() $\lambda = 0$

is the smallest eigenvalue and

$\lambda = 0$

is the smallest eigenvalue and

![]() $\phi = 1$

is the associated eigenfunction.

$\phi = 1$

is the associated eigenfunction.

Since the advection operator is a skew-adjoint operator,

![]() $\mathcal{L}$

is not a self-adjoint operator when the velocity field is non-zero. Hence, we introduce

$\mathcal{L}$

is not a self-adjoint operator when the velocity field is non-zero. Hence, we introduce

![]() $\lambda ^{*}$

and

$\lambda ^{*}$

and

![]() $\varphi (x, \boldsymbol{y})$

, which are the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of the adjoint eigenvalue problem given by

$\varphi (x, \boldsymbol{y})$

, which are the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of the adjoint eigenvalue problem given by

In the adjoint eigenvalue problem,

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}$

is replaced with

${\textit{Pe}}$

is replaced with

![]() $-{\textit{Pe}}$

, effectively reversing the flow direction.

$-{\textit{Pe}}$

, effectively reversing the flow direction.

Next, we choose

![]() $\phi _{n}$

and

$\phi _{n}$

and

![]() $\varphi _{n}$

such that the sets

$\varphi _{n}$

such that the sets

![]() $\left \{ \phi _{n} \right \}_{n=0}^{\infty }$

and

$\left \{ \phi _{n} \right \}_{n=0}^{\infty }$

and

![]() $\left \{ \varphi _{n} \right \}_{n=0}^{\infty }$

form a biorthogonal system, i.e.

$\left \{ \varphi _{n} \right \}_{n=0}^{\infty }$

form a biorthogonal system, i.e.

![]() $\left \langle \phi _{n}, \varphi _{m} \right \rangle = \delta _{n,m}$

, where

$\left \langle \phi _{n}, \varphi _{m} \right \rangle = \delta _{n,m}$

, where

![]() $\delta _{n,m}$

is the Kronecker delta. The solution of the advection--diffusion equation

$\delta _{n,m}$

is the Kronecker delta. The solution of the advection--diffusion equation

![]() $\partial _{t} c = \mathcal{L} c$

can be formally represented as

$\partial _{t} c = \mathcal{L} c$

can be formally represented as

The exact solution to this eigenvalue problem is typically unavailable, necessitating the use of numerical methods. However, the infinite domain presents challenges for numerical computations. One significant simplification of the problem is to consider the eigenfunctions in the form

where

![]() $\hat {\phi }(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)$

solves the equation

$\hat {\phi }(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)$

solves the equation

\begin{align} &\lambda \hat {\phi } = \kern2pt \hat{\kern-2pt \mathcal{L}}(k) \hat {\phi } = {\textit{Pe}} \big ( \mathrm{i} k u \hat {\phi } + u \partial _{x} \hat {\phi } + \boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} \hat {\phi } \big ) - \big ( \partial _{x}^{2} \hat {\phi } + 2\mathrm{i} k \partial _{x} \hat {\phi } + (\mathrm{i} k)^{2} \hat {\phi } + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}} \hat {\phi } \big ),\nonumber\\& \left . n_{x} \mathrm{i} k \hat {\phi } + n_{x} \partial _{x} \hat {\phi } + \partial _{\boldsymbol{n}_{y}} \hat {\phi } \right |_{w\textit{all}} = 0, \quad \hat {\phi }(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)=\hat {\phi }(x+L_{p}, \boldsymbol{y}, k), \end{align}

\begin{align} &\lambda \hat {\phi } = \kern2pt \hat{\kern-2pt \mathcal{L}}(k) \hat {\phi } = {\textit{Pe}} \big ( \mathrm{i} k u \hat {\phi } + u \partial _{x} \hat {\phi } + \boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} \hat {\phi } \big ) - \big ( \partial _{x}^{2} \hat {\phi } + 2\mathrm{i} k \partial _{x} \hat {\phi } + (\mathrm{i} k)^{2} \hat {\phi } + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}} \hat {\phi } \big ),\nonumber\\& \left . n_{x} \mathrm{i} k \hat {\phi } + n_{x} \partial _{x} \hat {\phi } + \partial _{\boldsymbol{n}_{y}} \hat {\phi } \right |_{w\textit{all}} = 0, \quad \hat {\phi }(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)=\hat {\phi }(x+L_{p}, \boldsymbol{y}, k), \end{align}

and

![]() $\hat {\varphi }(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)$

solves the adjoint equation

$\hat {\varphi }(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)$

solves the adjoint equation

\begin{align} &\lambda ^{*} \hat {\varphi } = \kern2pt \hat{\kern-2pt \mathcal{L}^{*}}(k) \hat {\varphi } = -{\textit{Pe}} \left ( \mathrm{i} k u \hat {\varphi } + u \partial _{x} \hat {\varphi } + \boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} \hat {\varphi } \right ) - \big ( \partial _{x}^{2} \hat {\varphi } + 2\mathrm{i} k \partial _{x} \hat {\varphi } + (\mathrm{i} k)^{2} \hat {\varphi } + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}} \hat {\varphi } \big ),\nonumber \\& \left . n_{x} \mathrm{i} k \hat {\varphi } + n_{x} \partial _{x} \hat {\varphi } + \partial _{\boldsymbol{n}_{y}} \hat {\varphi } \right |_{w\textit{all}} = 0, \quad \hat {\varphi }(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)=\hat {\varphi }(x+L_{p}, \boldsymbol{y}, k). \end{align}

\begin{align} &\lambda ^{*} \hat {\varphi } = \kern2pt \hat{\kern-2pt \mathcal{L}^{*}}(k) \hat {\varphi } = -{\textit{Pe}} \left ( \mathrm{i} k u \hat {\varphi } + u \partial _{x} \hat {\varphi } + \boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} \hat {\varphi } \right ) - \big ( \partial _{x}^{2} \hat {\varphi } + 2\mathrm{i} k \partial _{x} \hat {\varphi } + (\mathrm{i} k)^{2} \hat {\varphi } + \Delta _{\boldsymbol{y}} \hat {\varphi } \big ),\nonumber \\& \left . n_{x} \mathrm{i} k \hat {\varphi } + n_{x} \partial _{x} \hat {\varphi } + \partial _{\boldsymbol{n}_{y}} \hat {\varphi } \right |_{w\textit{all}} = 0, \quad \hat {\varphi }(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)=\hat {\varphi }(x+L_{p}, \boldsymbol{y}, k). \end{align}

A key observation is that

![]() $\hat {\phi }$

and

$\hat {\phi }$

and

![]() $\hat {\varphi }$

have a fundamental period of

$\hat {\varphi }$

have a fundamental period of

![]() $L_p$

, whereas the functions

$L_p$

, whereas the functions

![]() $\phi$

and

$\phi$

and

![]() $\varphi$

may have infinite fundamental periods. The periodic component of the solution is captured by

$\varphi$

may have infinite fundamental periods. The periodic component of the solution is captured by

![]() $\hat {\phi }$

, while the non-periodic part is represented by the plane wave

$\hat {\phi }$

, while the non-periodic part is represented by the plane wave

![]() $e^{\mathrm{i}kx}$

. This decomposition reduces the eigenvalue problem from an infinite domain to a finite domain of length

$e^{\mathrm{i}kx}$

. This decomposition reduces the eigenvalue problem from an infinite domain to a finite domain of length

![]() $L_p$

.

$L_p$

.

Two additional properties further simplify the analysis. First, it is straightforward to verify that

![]() $\lambda (-k)=\lambda (k)^{*}$

,

$\lambda (-k)=\lambda (k)^{*}$

,

![]() $\phi (x, \boldsymbol{y}, -k)=\phi (x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)^{*}$

and

$\phi (x, \boldsymbol{y}, -k)=\phi (x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)^{*}$

and

![]() $\varphi (x, \boldsymbol{y}, -k)=\varphi (x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)^{*}$

are eigenvalues and eigenfunctions. Therefore, it suffices to consider positive real values of

$\varphi (x, \boldsymbol{y}, -k)=\varphi (x, \boldsymbol{y}, k)^{*}$

are eigenvalues and eigenfunctions. Therefore, it suffices to consider positive real values of

![]() $k$

. Second,

$k$

. Second,

![]() $\hat {\phi }(x,\boldsymbol{y},k)$

is periodic in

$\hat {\phi }(x,\boldsymbol{y},k)$

is periodic in

![]() $k$

with period

$k$

with period

![]() $2\pi /L_p$

. To see this, note that

$2\pi /L_p$

. To see this, note that

Consequently, multiplying (2.16) by

![]() $e^{-\mathrm{i}x ({2\pi }/{L_{p}})}$

leads to

$e^{-\mathrm{i}x ({2\pi }/{L_{p}})}$

leads to

Since

![]() $e^{\mathrm{i}x ({2\pi }/{L_{p}})}\hat {\phi } (x, \boldsymbol{y},k)$

is periodic in

$e^{\mathrm{i}x ({2\pi }/{L_{p}})}\hat {\phi } (x, \boldsymbol{y},k)$

is periodic in

![]() $x$

with period

$x$

with period

![]() $L_{p}$

, it follows that

$L_{p}$

, it follows that

There are two main reasons for considering the eigenfunctions in the form (2.15). First, the special form of the eigenfunctions defined in (2.16) form a complete biorthogonal system for all square-integrable functions defined on the infinite channel domain. A rigorous justification for the completeness of this biorthogonal system is presented in Appendix A.2. The second reason is that an alternative approach yields the same form of the eigenfunction. It is intuitive to first consider the eigenvalue problem on a channel domain of finite length

![]() $L$

and then investigate the behaviour of the eigenfunctions as

$L$

and then investigate the behaviour of the eigenfunctions as

![]() $L$

approaches infinity. The multiscale asymptotic analysis presented in Appendix A.5 demonstrates that the eigenfunctions take the form (2.15) as

$L$

approaches infinity. The multiscale asymptotic analysis presented in Appendix A.5 demonstrates that the eigenfunctions take the form (2.15) as

![]() $L$

approaches infinity, thereby connecting to the multiscale analysis discussed in Rosencrans (Reference Rosencrans1997).

$L$

approaches infinity, thereby connecting to the multiscale analysis discussed in Rosencrans (Reference Rosencrans1997).

As a side remark, the eigenfunction representation (2.15) is mathematically equivalent to the Floquet–Bloch form used in solving the Schrödinger equation with periodic potentials (Bloch Reference Bloch1929). This representation was employed by Zwanzig (Reference Zwanzig1983) to study pure diffusion in periodically modulated channels. Allaire, Briane & Vanninathan (Reference Allaire, Briane and Vanninathan2016) compared the two-scale asymptotic expansion and Bloch-wave approaches for the periodic homogenisation of the Poisson equation, showing that the two methods yield identical second-order effective tensors but differ in their fourth-order corrections. To the best of our knowledge, the application of this form to the Taylor dispersion is new.

With the eigenfunctions expressed in the form (2.15), the solution to the advection--diffusion equation can be represented as follows:

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} c(x, \boldsymbol{y}, t) &= \int \limits _{-\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}}^{\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}} \sum \limits _{n=0}^{\infty } \left \langle c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}), \varphi _{n}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) \right \rangle \phi _{n}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) e^{-\lambda _{n}(k) t} \mathrm{d}k \\&= \frac {1}{2\pi }\sum \limits _{n=0}^{\infty } \int \limits _{-\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}}^{\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}} \big \langle c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}), e^{\mathrm{i} k x} \hat {\varphi }_{n}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) \big \rangle \hat {\phi }_{n}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) e^{\mathrm{i} k x - \lambda _{n}(k) t} \mathrm{d}k. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} c(x, \boldsymbol{y}, t) &= \int \limits _{-\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}}^{\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}} \sum \limits _{n=0}^{\infty } \left \langle c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}), \varphi _{n}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) \right \rangle \phi _{n}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) e^{-\lambda _{n}(k) t} \mathrm{d}k \\&= \frac {1}{2\pi }\sum \limits _{n=0}^{\infty } \int \limits _{-\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}}^{\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}} \big \langle c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}), e^{\mathrm{i} k x} \hat {\varphi }_{n}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) \big \rangle \hat {\phi }_{n}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) e^{\mathrm{i} k x - \lambda _{n}(k) t} \mathrm{d}k. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

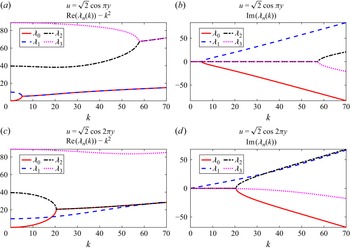

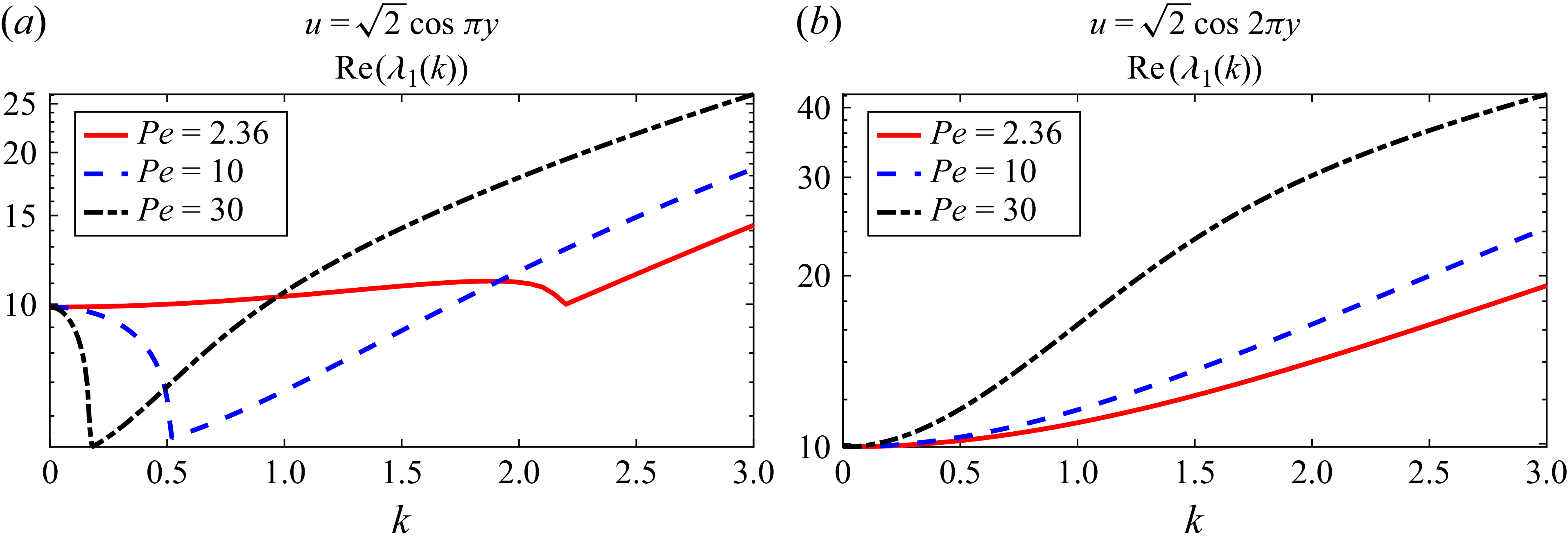

The ordering of the eigenvalues is determined by their real parts at

![]() $k=0$

, specifically

$k=0$

, specifically

![]() $0 = \lambda _{0}(0) \lt \textrm{Re} \lambda _{1}(0) \leqslant \ldots \leqslant \textrm{Re} \lambda _{n}(0) \ldots$

. If the real parts are equal when

$0 = \lambda _{0}(0) \lt \textrm{Re} \lambda _{1}(0) \leqslant \ldots \leqslant \textrm{Re} \lambda _{n}(0) \ldots$

. If the real parts are equal when

![]() $k=0$

, the ordering is then based on their real parts in the vicinity of zero wavenumber. For non-zero wavenumbers, we order the eigenvalues to ensure that

$k=0$

, the ordering is then based on their real parts in the vicinity of zero wavenumber. For non-zero wavenumbers, we order the eigenvalues to ensure that

![]() $\lambda _{n}(k)$

remains continuous with respect to

$\lambda _{n}(k)$

remains continuous with respect to

![]() $k$

. In this context, it is possible to have

$k$

. In this context, it is possible to have

![]() $\textrm{Re} \lambda _{n}(k) \lt \textrm{Re} \lambda _{m}(k)$

for some

$\textrm{Re} \lambda _{n}(k) \lt \textrm{Re} \lambda _{m}(k)$

for some

![]() $k$

with

$k$

with

![]() $n \gt m$

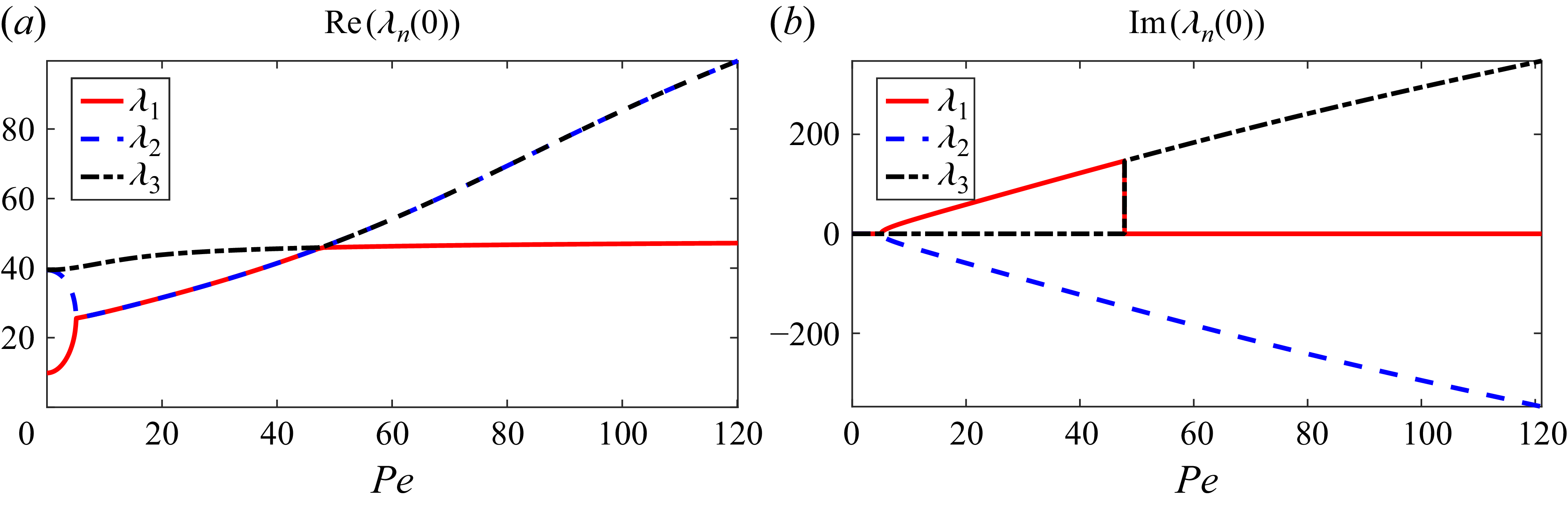

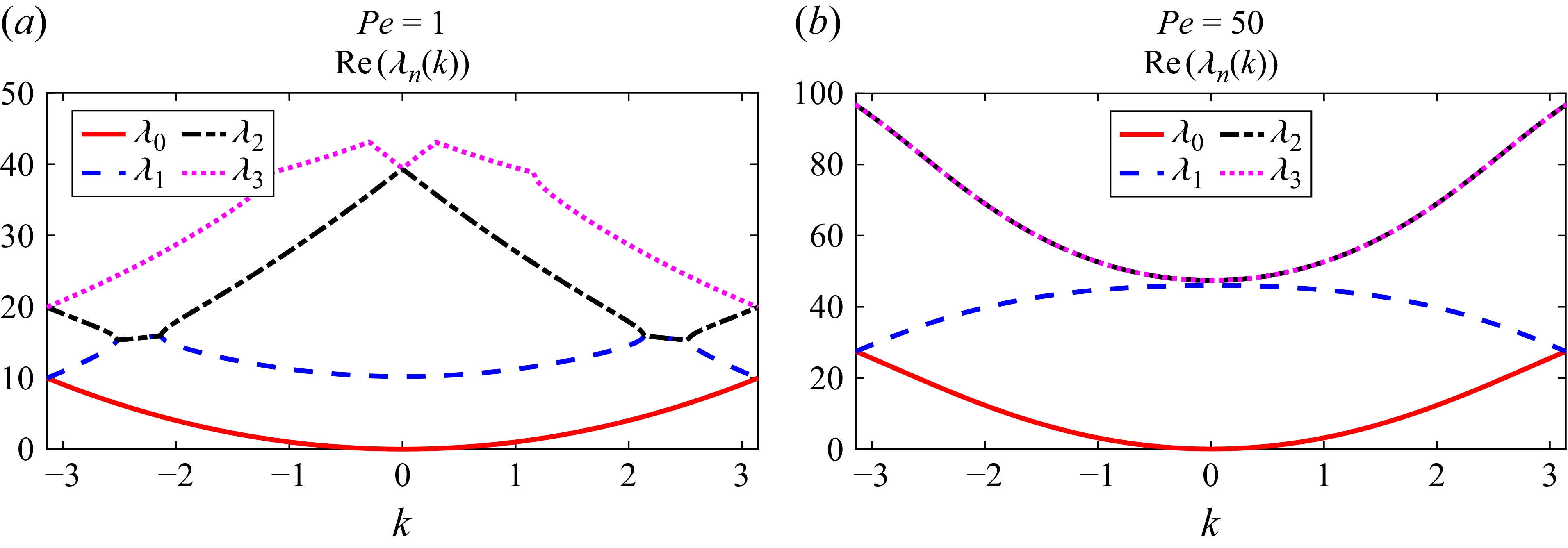

. Figure 5 shows such an example, which will be discussed in § 3. For the flat-walled channel (

$n \gt m$

. Figure 5 shows such an example, which will be discussed in § 3. For the flat-walled channel (

![]() $L_p = 0$

), (2.21) reduces to the Fourier-transform representation used in Stokes & Barton (Reference Stokes and Barton1990), Phillips & Kaye (Reference Phillips and Kaye1996), Ding & McLaughlin (Reference Ding and McLaughlin2022b

).

$L_p = 0$

), (2.21) reduces to the Fourier-transform representation used in Stokes & Barton (Reference Stokes and Barton1990), Phillips & Kaye (Reference Phillips and Kaye1996), Ding & McLaughlin (Reference Ding and McLaughlin2022b

).

2.4. Long-time asymptotic expansion

In this section we use the representation (2.21) to derive the long-time asymptotic expansion of the scalar field. The key observation is that

![]() $0 = \min _{k} \textrm{Re} \lambda _{0}(k) \lt \min _{k} \textrm{Re} \lambda _{1}(k) \leqslant \ldots$

implying that all higher-order terms in (2.21) decay exponentially in time. Hence, the leading term associated with

$0 = \min _{k} \textrm{Re} \lambda _{0}(k) \lt \min _{k} \textrm{Re} \lambda _{1}(k) \leqslant \ldots$

implying that all higher-order terms in (2.21) decay exponentially in time. Hence, the leading term associated with

![]() $\lambda _{0} (k)$

dominates the long-time behaviour:

$\lambda _{0} (k)$

dominates the long-time behaviour:

\begin{align} c(x, \boldsymbol{y}, t) &= \frac {1}{2\pi |\varOmega (L_p)|} \int \limits _{-\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}}^{\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}} \phi _{0}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) e^{-\lambda _{0}(k) t} \left (\, \int \limits _{\varOmega } c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}) \varphi _{0}^{*}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} \right ) \mathrm{d}k \nonumber\\&\quad + \mathcal{O}\left (e^{-\mathop{\textit{min}} \limits _{k} \textrm{Re} \lambda _{1}(k)t}\right )\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} c(x, \boldsymbol{y}, t) &= \frac {1}{2\pi |\varOmega (L_p)|} \int \limits _{-\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}}^{\frac {\pi }{L_{p}}} \phi _{0}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) e^{-\lambda _{0}(k) t} \left (\, \int \limits _{\varOmega } c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}) \varphi _{0}^{*}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} \right ) \mathrm{d}k \nonumber\\&\quad + \mathcal{O}\left (e^{-\mathop{\textit{min}} \limits _{k} \textrm{Re} \lambda _{1}(k)t}\right )\!. \end{align}

We denote the integral above as

![]() $c_{s}$

and refer to it as the slow manifold of the system for several reasons. First, the integral itself is a solution to the advection--diffusion equation, although with a different initial condition. Second, it captures the algebraically decaying dynamics at long times, while other modes decay exponentially. This integral represents a reduced description of the system’s long-time behaviour, which aligns with the typical characteristics of a slow manifold. The idea behind the approximation (2.22) is utilised in Bronski & McLaughlin (Reference Bronski and McLaughlin1997), Camassa et al. (Reference Camassa, Ding, Kilic and McLaughlin2021), Ding & McLaughlin (Reference Ding and McLaughlin2022b

) to investigate the long-time asymptotic properties in the scalar intermittency problem. Within the centre manifold framework adopted in Mercer & Roberts (Reference Mercer and Roberts1990), Roberts (Reference Roberts2014, Reference Roberts2015), Ding & McLaughlin (Reference Ding and McLaughlin2022a

), the cross-sectional average of the integral in (2.22) represents the centre manifold of the system. Finally, we note that

$c_{s}$

and refer to it as the slow manifold of the system for several reasons. First, the integral itself is a solution to the advection--diffusion equation, although with a different initial condition. Second, it captures the algebraically decaying dynamics at long times, while other modes decay exponentially. This integral represents a reduced description of the system’s long-time behaviour, which aligns with the typical characteristics of a slow manifold. The idea behind the approximation (2.22) is utilised in Bronski & McLaughlin (Reference Bronski and McLaughlin1997), Camassa et al. (Reference Camassa, Ding, Kilic and McLaughlin2021), Ding & McLaughlin (Reference Ding and McLaughlin2022b

) to investigate the long-time asymptotic properties in the scalar intermittency problem. Within the centre manifold framework adopted in Mercer & Roberts (Reference Mercer and Roberts1990), Roberts (Reference Roberts2014, Reference Roberts2015), Ding & McLaughlin (Reference Ding and McLaughlin2022a

), the cross-sectional average of the integral in (2.22) represents the centre manifold of the system. Finally, we note that

![]() $\lambda _{0}(k)$

could exceed

$\lambda _{0}(k)$

could exceed

![]() $\lambda _{1}(k)$

for values of

$\lambda _{1}(k)$

for values of

![]() $k$

away from zero. If the initial condition is localised around such modes, the approximation (2.22) may no longer be valid. In this work, however, we focus on slowly varying initial conditions, for which the

$k$

away from zero. If the initial condition is localised around such modes, the approximation (2.22) may no longer be valid. In this work, however, we focus on slowly varying initial conditions, for which the

![]() $k=0$

mode is non-zero and the approximation (2.22) provides the dominant contribution to the long-time behaviour.

$k=0$

mode is non-zero and the approximation (2.22) provides the dominant contribution to the long-time behaviour.

Further asymptotic analysis can be conducted by noting that the integral in (2.22) is a Laplace-type integral with respect to the wavenumber

![]() $k$

. The asymptotic expansion for large

$k$

. The asymptotic expansion for large

![]() $t$

can be derived using the steepest descent method, as outlined in Bender, Orszag & Orszag (Reference Bender, Orszag and Orszag1999), Ablowitz, Fokas & Fokas (Reference Ablowitz, Fokas and Fokas2003). Intuitively,

$t$

can be derived using the steepest descent method, as outlined in Bender, Orszag & Orszag (Reference Bender, Orszag and Orszag1999), Ablowitz, Fokas & Fokas (Reference Ablowitz, Fokas and Fokas2003). Intuitively,

![]() $\textrm{Re} \lambda _{0} = 0$

only when the wavenumber is zero, while it is positive for non-zero wavenumbers. For sufficiently large

$\textrm{Re} \lambda _{0} = 0$

only when the wavenumber is zero, while it is positive for non-zero wavenumbers. For sufficiently large

![]() $t$

,

$t$

,

![]() $e^{-\lambda _{0}(k) t}$

becomes exponentially small for non-zero wavenumbers. Therefore, the integrand near the zero wavenumber contributes dominantly when

$e^{-\lambda _{0}(k) t}$

becomes exponentially small for non-zero wavenumbers. Therefore, the integrand near the zero wavenumber contributes dominantly when

![]() $t$

is large. To compute the long-time asymptotic expansion, we expand the eigenvalue and eigenfunction around

$t$

is large. To compute the long-time asymptotic expansion, we expand the eigenvalue and eigenfunction around

![]() $k=0$

using the perturbation procedure detailed in Appendix A.3:

$k=0$

using the perturbation procedure detailed in Appendix A.3:

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \lambda _{0} &= \textrm{i}{\textit{Pe}} \left \langle u \right \rangle k + \left \langle 1 - {\textit{Pe}} \left ( u - \left \langle u \right \rangle \right ) \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} + \partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle k^{2} \\ & \quad - \mathrm{i} \left \langle \partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} - {\textit{Pe}} \left ( u - \left \langle u \right \rangle \right ) \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} \right \rangle k^{3} + \mathcal{O}(k^{4}), \\ \phi _{0} &= e^{\mathrm{i} k x} \left ( 1 + \mathrm{i} k \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} - k^{2} \left ( \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} + \frac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle \right ) + \mathcal{O}(k^{3}) \right )\!, \\ \varphi _{0} &= e^{\mathrm{i} k x} \left ( 1 + \mathrm{i} k q_{0}^{(1,1)} - k^{2} \left ( q_{0}^{(2,2)} + \frac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle \right ) + \mathcal{O}(k^{3}) \right ). \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \lambda _{0} &= \textrm{i}{\textit{Pe}} \left \langle u \right \rangle k + \left \langle 1 - {\textit{Pe}} \left ( u - \left \langle u \right \rangle \right ) \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} + \partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle k^{2} \\ & \quad - \mathrm{i} \left \langle \partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} - {\textit{Pe}} \left ( u - \left \langle u \right \rangle \right ) \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} \right \rangle k^{3} + \mathcal{O}(k^{4}), \\ \phi _{0} &= e^{\mathrm{i} k x} \left ( 1 + \mathrm{i} k \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} - k^{2} \left ( \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} + \frac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle \right ) + \mathcal{O}(k^{3}) \right )\!, \\ \varphi _{0} &= e^{\mathrm{i} k x} \left ( 1 + \mathrm{i} k q_{0}^{(1,1)} - k^{2} \left ( q_{0}^{(2,2)} + \frac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle \right ) + \mathcal{O}(k^{3}) \right ). \end{aligned} \end{equation}

The functions

![]() $\theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, \theta _{0}^{(2,2)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)}$

are periodic in

$\theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, \theta _{0}^{(2,2)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)}$

are periodic in

![]() $x$

with a fundamental period

$x$

with a fundamental period

![]() $L_{p}$

and have zero mean over the unit cell domain, satisfying

$L_{p}$

and have zero mean over the unit cell domain, satisfying

![]() $\langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, 1 \rangle = \langle \theta _{0}^{(2,2)}, 1 \rangle = \langle 1, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \rangle = 0$

. The function

$\langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, 1 \rangle = \langle \theta _{0}^{(2,2)}, 1 \rangle = \langle 1, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \rangle = 0$

. The function

![]() $\theta _{0}^{(1,1)}$

satisfies

$\theta _{0}^{(1,1)}$

satisfies

The function

![]() $q_{0}^{(1,1)}$

satisfies

$q_{0}^{(1,1)}$

satisfies

The function

![]() $\theta _{0}^{(2,2)}$

satisfies

$\theta _{0}^{(2,2)}$

satisfies

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &\kern2pt \hat{\kern-2pt \mathcal{L}}_{0}(0) \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} = {\textit{Pe}} \Big \langle u \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} \Big \rangle - {\textit{Pe}} \left ( u - \left \langle u \right \rangle \right ) \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} - \Big \langle \partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} \Big \rangle + 2 \partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, \\&\left . n_{x} \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} + n_{x} \partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} + \boldsymbol{n}_{\boldsymbol{y}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} \right |_{w\textit{all}} = 0. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &\kern2pt \hat{\kern-2pt \mathcal{L}}_{0}(0) \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} = {\textit{Pe}} \Big \langle u \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} \Big \rangle - {\textit{Pe}} \left ( u - \left \langle u \right \rangle \right ) \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} - \Big \langle \partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} \Big \rangle + 2 \partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, \\&\left . n_{x} \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} + n_{x} \partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} + \boldsymbol{n}_{\boldsymbol{y}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{y}} \theta _{0}^{(2,2)} \right |_{w\textit{all}} = 0. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

In addition to the eigenfunction expansion, we need the expansion of the integral related to the initial condition for small wavenumbers:

\begin{align} &\frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|}\int \limits _{\varOmega } c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}) \varphi _{0}^{*}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} \nonumber \\& \ = \frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|} \!\int \limits _{\varOmega }\! c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}) e^{-\mathrm{i} k x} \!\left (\! 1 - \mathrm{i} k q_{0}^{(1,1)} - k^{2} \!\left (\! q_{0}^{(2,2)} + \frac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle \!\right )\! + \mathcal{O}(k^{3})\! \right )\! \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} \nonumber \\& \ = \frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|}\int \limits _{\varOmega } c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}) \left ( 1 - \mathrm{i} k x + \frac {(-\mathrm{i} k x)^{2}}{2} + \mathcal{O}(k^{3}) \right ) \nonumber \\& \ \quad \times \left ( 1 - \mathrm{i} k q_{0}^{(1,1)} - k^{2} \left ( q_{0}^{(2,2)} + \frac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle \right ) + \mathcal{O}(k^{3}) \right ) \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} \nonumber \\& \ = c_{I}^{(0)} - \mathrm{i} k c_{I}^{(1)} - k^{2} c_{I}^{(2)} + \mathcal{O}(k^{3}). \end{align}

\begin{align} &\frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|}\int \limits _{\varOmega } c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}) \varphi _{0}^{*}(x, \boldsymbol{y}, k) \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} \nonumber \\& \ = \frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|} \!\int \limits _{\varOmega }\! c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}) e^{-\mathrm{i} k x} \!\left (\! 1 - \mathrm{i} k q_{0}^{(1,1)} - k^{2} \!\left (\! q_{0}^{(2,2)} + \frac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle \!\right )\! + \mathcal{O}(k^{3})\! \right )\! \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} \nonumber \\& \ = \frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|}\int \limits _{\varOmega } c_{I}(x, \boldsymbol{y}) \left ( 1 - \mathrm{i} k x + \frac {(-\mathrm{i} k x)^{2}}{2} + \mathcal{O}(k^{3}) \right ) \nonumber \\& \ \quad \times \left ( 1 - \mathrm{i} k q_{0}^{(1,1)} - k^{2} \left ( q_{0}^{(2,2)} + \frac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle \right ) + \mathcal{O}(k^{3}) \right ) \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} \nonumber \\& \ = c_{I}^{(0)} - \mathrm{i} k c_{I}^{(1)} - k^{2} c_{I}^{(2)} + \mathcal{O}(k^{3}). \end{align}

Here

\begin{align} c_{I}^{(0)}&=\frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|}\int \limits _{\varOmega }c_{I}(x,\boldsymbol{y}) \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y}, \quad c_{I}^{(1)}=\frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|} \int \limits _{\varOmega }c_{I}(x,\boldsymbol{y}) \left ( x+q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right )\mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y},\nonumber \\ c_{I}^{(2)}&=\frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|} \int \limits _{\varOmega }c_{I}(x,\boldsymbol{y}) \left ( \frac {x^{2}}{2}+ q_{0}^{(2,2)} + \frac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle +q_{0}^{(1,1)} x \right )\mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y}. \end{align}

\begin{align} c_{I}^{(0)}&=\frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|}\int \limits _{\varOmega }c_{I}(x,\boldsymbol{y}) \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y}, \quad c_{I}^{(1)}=\frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|} \int \limits _{\varOmega }c_{I}(x,\boldsymbol{y}) \left ( x+q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right )\mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y},\nonumber \\ c_{I}^{(2)}&=\frac {1}{|\varOmega (L_p)|} \int \limits _{\varOmega }c_{I}(x,\boldsymbol{y}) \left ( \frac {x^{2}}{2}+ q_{0}^{(2,2)} + \frac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle +q_{0}^{(1,1)} x \right )\mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y}. \end{align}

The steepest descent method requires expanding

![]() $\lambda _{0}(k)$

around the saddle point in the complex plane. Note that the expansion (2.23) implies that the saddle point of

$\lambda _{0}(k)$

around the saddle point in the complex plane. Note that the expansion (2.23) implies that the saddle point of

![]() $\lambda _{0}(k)$

is not located at

$\lambda _{0}(k)$

is not located at

![]() $k=0$

if

$k=0$

if

![]() $\left \langle u \right \rangle \neq 0$

. In fact, this expansion around this saddle point provides us with an asymptotic expansion of (2.22) as

$\left \langle u \right \rangle \neq 0$

. In fact, this expansion around this saddle point provides us with an asymptotic expansion of (2.22) as

![]() $t \rightarrow \infty$

while keeping other variables fixed. Notably, this type of expansion is not uniform with respect to the spatial variable. To achieve a uniform asymptotic expansion, we should notice that the whole scalar is transported by the flow with the non-zero mean flow speed. Therefore, we analyse the problem in the moving frame of reference

$t \rightarrow \infty$

while keeping other variables fixed. Notably, this type of expansion is not uniform with respect to the spatial variable. To achieve a uniform asymptotic expansion, we should notice that the whole scalar is transported by the flow with the non-zero mean flow speed. Therefore, we analyse the problem in the moving frame of reference

![]() $x_{m} = x - {\textit{Pe}} \left \langle u \right \rangle t$

. In this frame,

$x_{m} = x - {\textit{Pe}} \left \langle u \right \rangle t$

. In this frame,

![]() $k=0$

is the saddle point of

$k=0$

is the saddle point of

![]() $\lambda _{0}(k)$

and the steepest decent method yields a uniform asymptotic expansion.

$\lambda _{0}(k)$

and the steepest decent method yields a uniform asymptotic expansion.

Substituting the expansions (2.23) and (2.27) into (2.22) yields the asymptotic expansion of the scalar field at long times:

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &c (x,\boldsymbol{y},t) =\frac { e^{-\frac {x_{m}^2}{2 t \lambda ''(0)}}}{|\varOmega (L_p)|\sqrt {2 \pi t \lambda ''(0)}} \int \limits _{\varOmega }c_{I}(x,\boldsymbol{y}) \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} +\frac { x_{m} e^{-\frac {x_{m}^2}{2 t \lambda ''(0)}}}{\sqrt {2 \pi }\left (t \lambda ''(0)\right )^{3/2}} \!\left ( c_{I}^{(1)}-\theta _{0}^{(1,1)} c_{I}^{(0)}\! \right )\\ &+\frac { e^{-\frac {x_{m}^2}{2 t \lambda ''(0)}} \!\left (x_{m}^2-t \lambda ''(0)\right ) \!\left ( \!\left ( \!\theta _{0}^{(2,2)} \!+\! \dfrac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle \right ) c_{I}^{(0)}- \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} c_{I}^{(1)}+c_{I}^{(2)} \!\right )}{\sqrt {2 \pi }\left (t \lambda ''(0)\!\right )^{5/2}}+\mathcal{O} \!\left ( t^{-\frac {3}{2}} \!\right )\!. \\ \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &c (x,\boldsymbol{y},t) =\frac { e^{-\frac {x_{m}^2}{2 t \lambda ''(0)}}}{|\varOmega (L_p)|\sqrt {2 \pi t \lambda ''(0)}} \int \limits _{\varOmega }c_{I}(x,\boldsymbol{y}) \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{y} +\frac { x_{m} e^{-\frac {x_{m}^2}{2 t \lambda ''(0)}}}{\sqrt {2 \pi }\left (t \lambda ''(0)\right )^{3/2}} \!\left ( c_{I}^{(1)}-\theta _{0}^{(1,1)} c_{I}^{(0)}\! \right )\\ &+\frac { e^{-\frac {x_{m}^2}{2 t \lambda ''(0)}} \!\left (x_{m}^2-t \lambda ''(0)\right ) \!\left ( \!\left ( \!\theta _{0}^{(2,2)} \!+\! \dfrac {1}{2}\left \langle \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}, q_{0}^{(1,1)} \right \rangle \right ) c_{I}^{(0)}- \theta _{0}^{(1,1)} c_{I}^{(1)}+c_{I}^{(2)} \!\right )}{\sqrt {2 \pi }\left (t \lambda ''(0)\!\right )^{5/2}}+\mathcal{O} \!\left ( t^{-\frac {3}{2}} \!\right )\!. \\ \end{aligned} \end{equation}

Note that not all terms of order

![]() $\mathcal{O}(t^{-3/2})$

are included above. Capturing the full expansion to this order requires extending the eigenvalue expansion to

$\mathcal{O}(t^{-3/2})$

are included above. Capturing the full expansion to this order requires extending the eigenvalue expansion to

![]() $\mathcal{O}(k^{5})$

and the eigenfunction expansion to

$\mathcal{O}(k^{5})$

and the eigenfunction expansion to

![]() $\mathcal{O}(k^{3})$

, resulting in a lengthy expression that is omitted here for brevity.

$\mathcal{O}(k^{3})$

, resulting in a lengthy expression that is omitted here for brevity.

In Fourier space, multiplication by

![]() $k$

corresponds to differentiation in physical space. Since derivatives of the Gaussian function yield Hermite polynomials multiplied by the Gaussian, each higher-order term in (2.29) takes the form of a Hermite polynomial times a Gaussian, with coefficients determined by the eigenfunction expansion.

$k$

corresponds to differentiation in physical space. Since derivatives of the Gaussian function yield Hermite polynomials multiplied by the Gaussian, each higher-order term in (2.29) takes the form of a Hermite polynomial times a Gaussian, with coefficients determined by the eigenfunction expansion.

A more accurate approximation can be obtained by incorporating information about the initial condition. For instance, if the initial condition is a Gaussian distribution

![]() $\mathcal{N}(x; x_0,\sigma )$

centred at

$\mathcal{N}(x; x_0,\sigma )$

centred at

![]() $x=x_{0}$

with standard deviation

$x=x_{0}$

with standard deviation

![]() $\sigma$

,

$\sigma$

,

In this case, instead of approximating

![]() $e^{-\mathrm{i} k x}$

using its small

$e^{-\mathrm{i} k x}$

using its small

![]() $k$

expansion as in (2.27), we can directly evaluate the integral involving the initial condition. This approach yields an expansion that is asymptotically equivalent to (2.29) at long times while significantly improving accuracy at short times.

$k$

expansion as in (2.27), we can directly evaluate the integral involving the initial condition. This approach yields an expansion that is asymptotically equivalent to (2.29) at long times while significantly improving accuracy at short times.

The leading-order term in the approximation (2.29) is a Gaussian function, which corresponds to the solution of a one-dimensional advection–diffusion equation with an enhanced diffusion coefficient:

This equation serves as the effective long-time approximation of (2.7). The coefficient

![]() $\kappa _{\textit{eff}}$

represents the effective diffusivity, which is consistent with the definition given in (2.11). To show that the effective diffusivity is real and non-negative, we rewrite it as

$\kappa _{\textit{eff}}$

represents the effective diffusivity, which is consistent with the definition given in (2.11). To show that the effective diffusivity is real and non-negative, we rewrite it as

where the inequality follows from the fact that

![]() $\theta _{0}^{(1,1)}$

is real. This expression for the effective diffusivity aligns with previously reported results in Brenner (Reference Brenner1980), Rosencrans (Reference Rosencrans1997). (The function

$\theta _{0}^{(1,1)}$

is real. This expression for the effective diffusivity aligns with previously reported results in Brenner (Reference Brenner1980), Rosencrans (Reference Rosencrans1997). (The function

![]() $\theta _0^{(1,1)}$

satisfies the same cell problem as

$\theta _0^{(1,1)}$

satisfies the same cell problem as

![]() $\chi _i$

in Rosencrans (Reference Rosencrans1997, p. 1225), and thus, (2.32) corresponds directly to the expression for the enhanced diffusion coefficient given on p. 1226 of the same reference.) Furthermore, the validity of this formula has been confirmed through benchmarking against particle tracking methods, as demonstrated in Richmond et al. (Reference Richmond, Perkins, Scheibe, Lambert and Wood2013), Haugerud et al. (Reference Haugerud, Linga and Flekkøy2022).

$\chi _i$

in Rosencrans (Reference Rosencrans1997, p. 1225), and thus, (2.32) corresponds directly to the expression for the enhanced diffusion coefficient given on p. 1226 of the same reference.) Furthermore, the validity of this formula has been confirmed through benchmarking against particle tracking methods, as demonstrated in Richmond et al. (Reference Richmond, Perkins, Scheibe, Lambert and Wood2013), Haugerud et al. (Reference Haugerud, Linga and Flekkøy2022).

Finally, there is an intriguing question that is difficult to address in other frameworks but becomes more tractable in the proposed approach: How does the effective diffusivity change when the flow direction is reversed, i.e. when

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}$

is replaced by

${\textit{Pe}}$

is replaced by

![]() $-{\textit{Pe}}$

? This question arose from examining the formula for the effective diffusivity (2.31). At first glance, the forcing term suggests that

$-{\textit{Pe}}$

? This question arose from examining the formula for the effective diffusivity (2.31). At first glance, the forcing term suggests that

![]() $\partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}$

scales as

$\partial _{x} \theta _{0}^{(1,1)}$

scales as

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}$

, while

${\textit{Pe}}$

, while

![]() ${\textit{Pe}} (u - \langle u \rangle )\theta _{0}^{(1,1)}$

scales as

${\textit{Pe}} (u - \langle u \rangle )\theta _{0}^{(1,1)}$

scales as

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}^{2}$

. This scaling would imply the possible presence of a

${\textit{Pe}}^{2}$

. This scaling would imply the possible presence of a

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}$

-order term in the effective diffusivity, potentially making it a non-even function of

${\textit{Pe}}$

-order term in the effective diffusivity, potentially making it a non-even function of

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}$

.

${\textit{Pe}}$

.

Replacing

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}$

by

${\textit{Pe}}$

by

![]() $-{\textit{Pe}}$

essentially switches the roles of the eigenvalue problem (2.12) and its adjoint counterpart (2.13). Consequently, the effective diffusivity changes from

$-{\textit{Pe}}$

essentially switches the roles of the eigenvalue problem (2.12) and its adjoint counterpart (2.13). Consequently, the effective diffusivity changes from

![]() $\kappa _{\textit{eff}} = {\lambda ''(0)}/{2}$

to

$\kappa _{\textit{eff}} = {\lambda ''(0)}/{2}$

to

![]() $\kappa _{\textit{eff}} = {(\lambda ''(0))^{*}}/{2}$

. Since

$\kappa _{\textit{eff}} = {(\lambda ''(0))^{*}}/{2}$

. Since

![]() $\lambda ''(0)$

is real, the effective diffusivity remains unchanged. One alternative approach to demonstrate this symmetry is to compute a power series expansion of the effective diffusivity in terms of

$\lambda ''(0)$

is real, the effective diffusivity remains unchanged. One alternative approach to demonstrate this symmetry is to compute a power series expansion of the effective diffusivity in terms of

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}$

and show that all odd-order terms vanish, implying that the effective diffusivity is an even function of

${\textit{Pe}}$

and show that all odd-order terms vanish, implying that the effective diffusivity is an even function of

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}$

. However, this calculation is relatively lengthy, whereas the symmetry arises more directly within the framework proposed in this work.

${\textit{Pe}}$

. However, this calculation is relatively lengthy, whereas the symmetry arises more directly within the framework proposed in this work.

2.5. Connection to the time scale for dispersion, longitudinal normality and transverse uniformity

From the derivation in the previous section, we observe that the effective equation (2.31) is obtained through two successive approximations. The first approximation assumes that the scalar field can be described by its slow manifold with exponentially decaying correction terms. This approximation is valid on the time scale estimated by

which depends solely on the domain geometry and velocity field. A larger

![]() $\min_k \textrm{Re} \lambda _1(k)$

leads to faster convergence, whereas a smaller

$\min_k \textrm{Re} \lambda _1(k)$

leads to faster convergence, whereas a smaller

![]() $\min _k \textrm{Re} \lambda _1(k)$

results in slower convergence. The second approximation expresses the slow manifold as a Gaussian distribution plus algebraically decaying correction terms. Therefore, validity of the Gaussian distribution approximation depends on the decay of these correction terms, as given in (2.29), and the initial condition.

$\min _k \textrm{Re} \lambda _1(k)$

results in slower convergence. The second approximation expresses the slow manifold as a Gaussian distribution plus algebraically decaying correction terms. Therefore, validity of the Gaussian distribution approximation depends on the decay of these correction terms, as given in (2.29), and the initial condition.

To better understand the relationship between the time scales for dispersion, longitudinal normality and transverse uniformity, we consider an explicit example: a flat channel domain

subject to shear flow

![]() $ \boldsymbol{u} = (({3}/{2})(1 - 4y^2),0)$

and an initial condition given by (2.30). To characterise the time scale for transverse uniformity, we analyse the long-time asymptotic expansion of the scalar field. For longitudinal normality, we evaluate the asymptotic behaviour of the cross-sectionally averaged scalar. To determine the dispersion time scale, we examine the long-time expansion of the scalar variance.

$ \boldsymbol{u} = (({3}/{2})(1 - 4y^2),0)$

and an initial condition given by (2.30). To characterise the time scale for transverse uniformity, we analyse the long-time asymptotic expansion of the scalar field. For longitudinal normality, we evaluate the asymptotic behaviour of the cross-sectionally averaged scalar. To determine the dispersion time scale, we examine the long-time expansion of the scalar variance.

Using the method outlined in the previous section, we obtain the long-time asymptotic expansion of the scalar field:

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} c=&\frac {e^{-\frac {x^2}{2 v}}}{\sqrt {2 \pi v }}\left ( 1+\frac {a_{1}\left (240 y^4-120 y^2+7\right )}{480 } +\frac {a_{2} \left (240 y^2 \left (720 y^6-784 y^4+238 y^2-17\right )-413\right )}{3225600}\right .\\ & -\frac {a_{3}\left (1064960 t-520 \left (-15686 y^2+32 \left (10800 y^6-18568 y^4+10725 y^2-2079\right ) y^4+8447\right ) y^2+240261\right )}{73801728000 } \\ & \frac {a_{4}}{16862218813440000} \left ( 763467599-38993920 t \left (1560 \left (2 y^2-1\right ) y^2+283\right )+ 2720 y^2 \right . \\ &\hspace {2.3cm}\times \left (1127049 -26712502 y^2 +101146864 y^4-78215280 y^6 \right . \\ &\hspace {2.5cm} \left . \left . \left . -259440896 y^8 +779717120 y^{10} -897085440 y^{12} + 377395200 y^{14}\right ) \right ) \right )+\mathcal{O} \left(t^{-\frac {3}{2}}\right)\!. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} c=&\frac {e^{-\frac {x^2}{2 v}}}{\sqrt {2 \pi v }}\left ( 1+\frac {a_{1}\left (240 y^4-120 y^2+7\right )}{480 } +\frac {a_{2} \left (240 y^2 \left (720 y^6-784 y^4+238 y^2-17\right )-413\right )}{3225600}\right .\\ & -\frac {a_{3}\left (1064960 t-520 \left (-15686 y^2+32 \left (10800 y^6-18568 y^4+10725 y^2-2079\right ) y^4+8447\right ) y^2+240261\right )}{73801728000 } \\ & \frac {a_{4}}{16862218813440000} \left ( 763467599-38993920 t \left (1560 \left (2 y^2-1\right ) y^2+283\right )+ 2720 y^2 \right . \\ &\hspace {2.3cm}\times \left (1127049 -26712502 y^2 +101146864 y^4-78215280 y^6 \right . \\ &\hspace {2.5cm} \left . \left . \left . -259440896 y^8 +779717120 y^{10} -897085440 y^{12} + 377395200 y^{14}\right ) \right ) \right )+\mathcal{O} \left(t^{-\frac {3}{2}}\right)\!. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

Here

![]() $ v = \sigma ^2 + 2 \kappa _{\textit{eff}} t$

and

$ v = \sigma ^2 + 2 \kappa _{\textit{eff}} t$

and

![]() $ x_m = x - x_0 - {\textit{Pe}} t$

. The coefficients

$ x_m = x - x_0 - {\textit{Pe}} t$

. The coefficients

![]() $ a_n$

are given by

$ a_n$

are given by

where

![]() $ H_n$

is the Hermite polynomial of degree

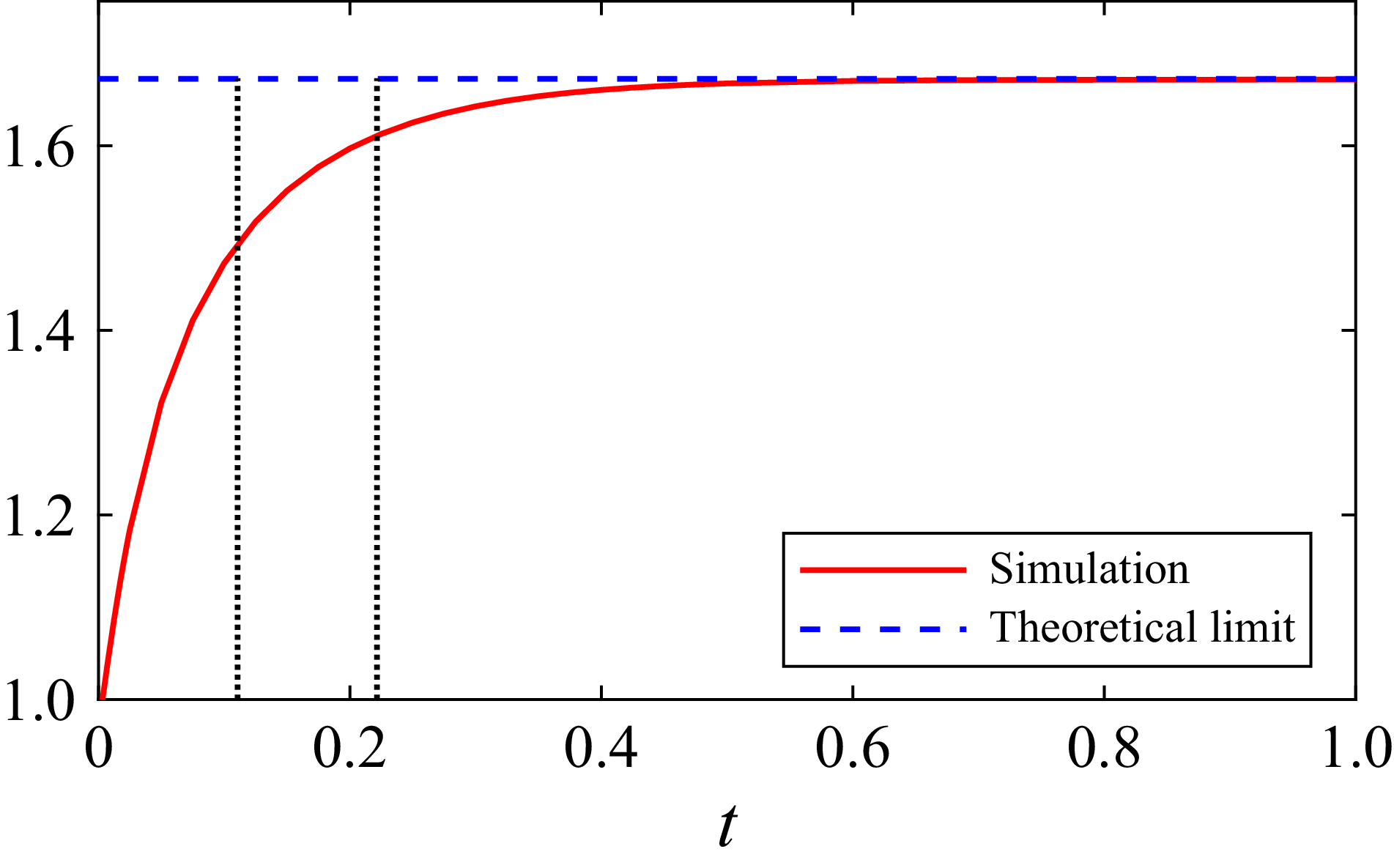

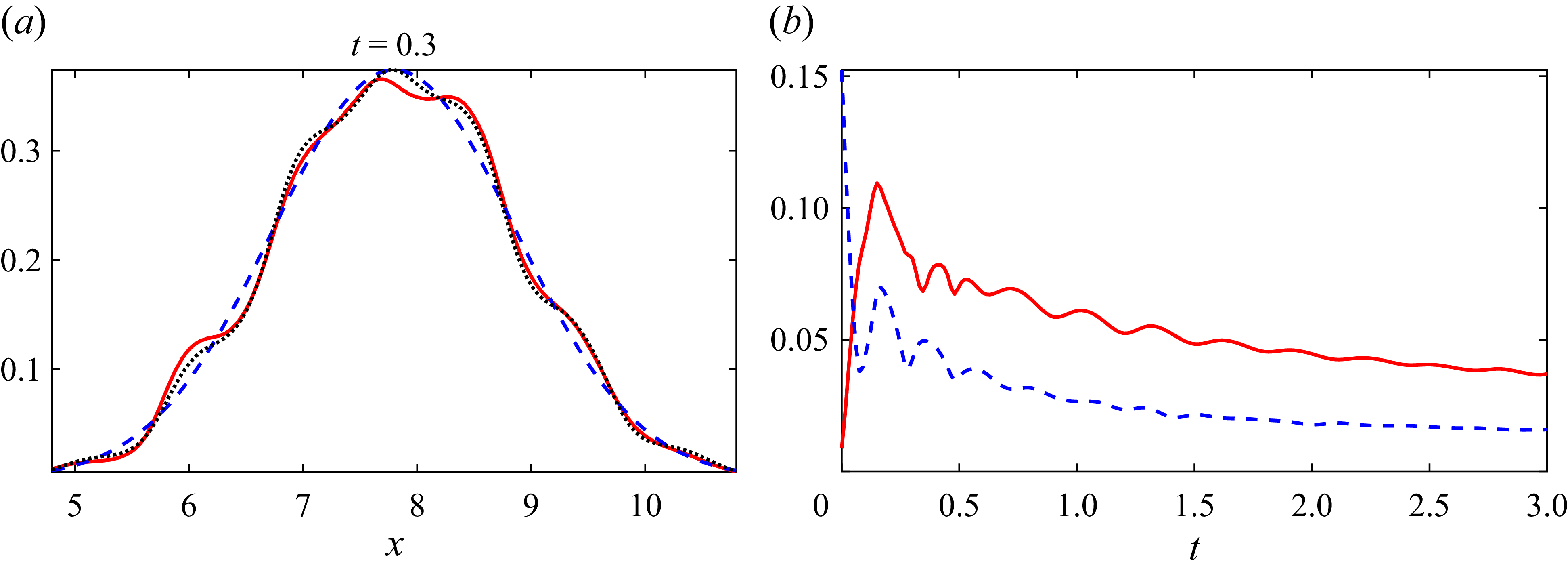

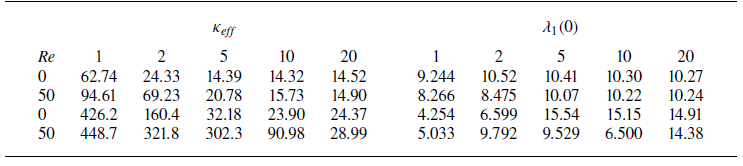

$ H_n$