Why do I compose the way I do? Why do I make sonic choices the way I do? My entire impetus for composing has its origin in my work with R. Murray Schafer and the World Soundscape Project in 1973–74. Yes, I studied music, but I never studied composition. In fact, I felt a bit lost as a music student and didn’t really know what I would do with my music degree. But I loved listening to music and perhaps was more interested in musicology, a dilemma I did not really understand at the time. When (after I had completed my music studies) my work with the World Soundscape Project opened my ears to the entire world, it was as if my ears had found their key inspiration: to be allowed to listen to the soundscape in a critical way, to analyse and study it, in fact to listen to it – as Schafer proposed – as if it was a musical composition. This proposition very much attracted me, as it envisioned musicians and composers in a role beyond aesthetics and culture, and more importantly as agents of change in the quality of our soundscapes.

The idea that we could be socially, politically, and environmentally useful really inspired me. And much of my work as a researcher with the World Soundscape Project and for Murray while he was writing his book The Tuning of the World Footnote 1 involved research into areas far away from music and composition. For example, we researched noise legislation locally, in Canada, and in many parts of the world. We also put together what we called a ‘literature file’, in which we gathered quotes about sound from as many books as could be read, but particularly from earlier times when there were no tape recorders and words were the only way to describe the soundscape. It was one of my jobs to gather as many quotes as possible. In addition, we were studying sound from all possible perspectives, including the various already existing scientific disciplines of sound such as acoustics, psychoacoustics, audiology, bioacoustics, noise control and measurement, architectural acoustics, phonetics, and acoustical engineering.

This research work brought out the educator and activist in me. I was discovering noise and the ecological imbalances in the soundscape, and I wanted to be instrumental in making improvements in our sound environments. For a while, after I had worked with the World Soundscape Project, I was hired by a local environmental organizationFootnote 2 to develop educational materials about noise as a significant environmental issue. In that context, I gave many noise workshops in schools to students of all ages, as well as to university students in faculties such as law and urban studies, even to members of Vancouver’s city council. We were also fighting the expansion of Vancouver International Airport and had concerns about neighbourhood noise.

But even in that work I continued to feel most connected to Schafer’s fundamental proposal that much essential information can be gained from the soundscape by listening to it with open and critical ears. Research and scientific studies are one way to learn about the sound environment, but the perceptual approach of listening offers another level of discovery and knowledge. Schafer had invented the soundwalk, and we developed sound monitoring exercises, sound counts, and other such approaches – a kind of qualitative research on the soundscape as opposed to the mostly quantitative approach of the noise studies of that time – developing ever more complex ways of measuring noise and the effects of noise. The proposal to listen to the soundscape, and especially to listen to noise, was unusual at the time. But our belief was that if we really did that kind of listening, we would be able to discover crucial information beyond numbers, figures, and measurements: how a soundscape impacts us and other living beings, how it may or may not interfere with communication, how we react to its sounds, what our relationship is to the soundscape, and ultimately even how we listen. This approach was exciting and deeply meaningful to me at the time. The emphasis in our work was not on fighting noise or being anti-noise activists, but on gaining information through perceptual inquiry, letting the soundscape speak to us and interpreting the meanings of its sonic language.

I also learned first approaches to field recording, although at that time my colleagues did most of the recordings for the World Soundscape Project. But together we spent many hours of listening to these recordings, which in itself added significantly to further ear openings and expanded consciousness of environmental sounds. In addition, my first experiments in the studio quickly led to the discovery that I loved the process and the detailed work with sound in that extraordinarily quiet environment. The sum of all these approaches, our whole endeavour, was a hugely enriching and never-ending learning process.Footnote 3

Parallel to the soundscape work, I became involved with Vancouver Co-operative Radio, then a new community radio station in our city, which was politically leftist and pretty radical at the time. It still exists and continues to offer alternative broadcast voices and approaches. But for those of us who were more culturally oriented, it also offered an opportunity to experiment with radio as an artistic medium. It was very exciting to broadcast within this framework of both a politically leftist orientation and an experimental approach to radio.

How can compositions listen?

The title of this article, Compositions That Listen, originates in my experience with radio. It picks up certain ideas from an article I wrote years ago introducing the concept of radio that listens. It emerged from my years of broadcasting experience on Vancouver Co-operative Radio, and in particular my programme Soundwalking, which I produced and hosted in 1978–79. My idea about radio was that

instead of merely broadcasting at us, we listen through it… Radio listens through its microphones to the world, to human voices, to the environment. Radio that listens then is about the recordist’s position and perspective, the physical, psychological, political, and cultural stance shaping the choices when recording. My choices are influenced by an understanding of the sonic environment as an intimate reflection of the social, technological, and natural conditions of the area.Footnote 4

So one could say that soundscape compositions can very well be compositions that listen. I perceive my own compositions – based entirely on environmental sounds recorded by myself – as providing a time frame for listening to specific places, situations, occurrences, a time frame for contemplation of these. One does not just bring the recordings into the studio; one also brings in the experiences that one has had in the field while recording. That experience, that relationship that one gains while recording, also enters into the compositional process. It may in fact inspire ideas of sonic pacing or allow structural patterns to emerge. The sonic musical possibilities lie in the recorded sounds and their complete uniqueness. Each recording is an excerpt of a soundscape, of a time frame, an excerpt of a place, and as a result has its specific qualities. I have a number of raven recordings, but only one gave me a drum-like throbbing sound when I slowed it down while composing Beneath the Forest Floor (1992).

No other raven recording gave me that particular sound for my composition. So finding a recording like this felt like a gift that I received in that moment in time when the raven came to my microphone in a very specific way. And working with such a sound in the studio can become a journey of discovery and sometimes a magical emergence of unexpected new sounds, of new musical-sonic expressiveness, and possibly a deeper understanding of the sounds’ meanings in the environment and within the composition itself. It is not only a discovery of what the recordings can give me musically and sonically, but most significantly each sound, each soundscape, and each recording inherently carries meaning within its very structure and specific quality. And this is precisely the essence of soundscape composition – composition that listens. It is absolutely never abstract.

Therefore, when I compose with environmental sounds, it is this edge between their musical/sonic characteristics and expressiveness and the meanings they carry within them that interests me the most. In a way, one could say that environmental sounds are the ‘language’ with which I speak about a place, a time, or a situation in my compositions. Through this language in soundscape composition, one is given the opportunity to listen to the world in specific ways. And the composer is the agent who facilitates this listening. More significantly, it feels as if I am collaborating with the sounds of the environment. It is not just me, the composer, presenting a piece. No, it feels more like the sounds themselves and their expressive qualities and my own compositional imagination and language are ‘speaking’ together. I would like to think that, when listening to soundscape compositions, we listen through them to the world.Footnote 5

Ethics of listening and recording

In today’s age, ethical questions arise in the context of field recording and soundscape composition that went unconsidered in the early seventies when we started to record the sonic environment on a larger scale than ever before. Sound recording technology was then becoming portable, if still expensive, quite bulky, and heavyweight. But it meant that if we could afford to buy the equipment, we basically could record everything. Perhaps it is impossible to convey the extent of our excitement, when nowadays anyone can record and make videos with their phones at any time of day or night and in any situation. An equivalent to the magic we felt then might be the subsequent development of hydrophones that allowed us to listen to underwater soundscapes, and more recently the emerging data-recording technology that reveals the sounds of plants.

With the ubiquitous use of recording technologies must come an increased questioning of their ethical use, of the way a recordist approaches an environment for the purposes of research, documentation, data gathering, or cultural productions. In the seventies, the thought of being able to record anything dominated our mind space. Nature recordists delighted in the ability to record birdsong, for example, and to educate listeners about birds and their habitats. There was little thought – as there is now – of asking the land, the place where they live, for permission, or of giving something back in return in the ecological sense. The recording process was a deeply inspirational and educational ear-opening experience, seemingly powerful enough in itself to justify an approach of recording for recording’s sake. Ironically, while mobile phones are used on a mass scale to record and document anything and everything quite indiscriminately and often without much thought, field recording, soundscape listening, and soundwalking activities tend to take an increasingly more mindful approach that includes ethical considerations and relationship building with that which is listened to or recorded. In his book Hungry Listening, Dylan Robinson muses on the complexities of listening in our world, where space must be made for decolonial thinking, Indigenous sovereignty, and the resulting implications for listening. He writes:

Developing practices of Deep Listening and critical listening positionality requires us to adopt self-reflexive ethics about the appropriate conditions for listening: the right place, time, and frame of mind. That, in turn, requires a self-reflexiveness of positionality as other than mere identity category, and instead as an alertness to the intersection of perception and relationality. For myself, this might mean… finding ways (as in Oliveros’s work) to place oneself in new relationships with that which one listens to. … I’m invested in finding ways to help us hear the normative ways that we listen, that then lead to re-positioning. But that re-positioning doesn’t mean that we seek to adopt Indigenous ways of listening, because I wonder – if Indigenous methodologies are located in a deeply embodied/experiential relationship to culture and place, what does it mean to ‘adopt’ such methods without that lived experience? At its worst it might result in an auditory form of ‘going native’. I’m more interested in decolonial forms that allow for self-unsettlement as listeners.Footnote 6

In the 1970s, the ability to record any sound or soundscape disturbed the status quo of our relationship to the sound environment. Indeed, it felt like a liberation from the elusiveness of sound and at the same time the empowerment to be able to ‘capture’ any sound we wanted, including people’s voices that happened to be part of a soundscape recording. We didn’t necessarily think of asking permission to put these voices into a composition, especially since we never identified anyone by name. These voices were understood – by me at least – as part of the soundscape, and their tone and expressiveness were just as interesting as any of the other sounds in the recorded sound environment and had their own sonic integrity within that context.

This approach to recording resonated with an approach to broadcasting that dominated Vancouver Co-operative Radio in the 1970s, which intentionally sought out a different ‘tone’ and pace than the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) or any commercial radio station. Our mission was to provide broadcast opportunities for those voices in society that one would normally not hear on the other media. As we articulated it at the time, we were going to ‘give voice’ to the disenfranchised voices in society. In other words, Vancouver Co-operative Radio was providing a social, political balance in the world of broadcasting, where any member of a community could ‘do’ radio. In this model, any listener could also be a broadcaster and vice versa, with the result that it created a new relationship between radio and its community, a shift in the status quo. It unsettled the existing hierarchy between broadcaster and mostly passive listening audiences and created new relationships between listener and broadcaster, an opportunity for all of us to speak out equally. This was very characteristic for the 1970s: a revolutionary attitude that sought to stir things up and do them differently, to perceive society and the environment in new ways. The tone then was more confrontational and might tend to alienate nowadays.

However, Vancouver Co-operative Radio provided a framework for a broadcasting approach that was not only politically confrontational but also allowed for broadcasting of a more experimental nature. It was ideal for a programme such as my Soundwalking show in which I presented field recordings from in and around Vancouver, something one did not normally hear over the radio at that time. I remember getting a phone call from a German TV correspondent who lived in Vancouver and for whom I had done some voice-over work. He expressed complete astonishment over the fact that I had ‘dared’ to broadcast 20 minutes of very snowy silence that I had recorded on Hollyburn Mountain near Vancouver. Quiet and silence would traditionally set off alarms in conventional media, such as commercial radio and the CBC. He presented it as a revolutionary act that I had committed, although he also perceived it as a very positive act.

Thinking and composing politically

In preparation for writing this article, I went through my list of compositions in order to eliminate from consideration those that were not political in any way or were devoid of any sort of social, political, or environmental message. But I could not find any, which in turn made it a challenge to choose sound examples for this text. I decided therefore that I would choose excerpts from pieces that ‘shout out’ politically more overt messages and are more confrontational in tone, and thus possibly more uncomfortable for the listener.

A Walk Through the City (1981)

The first piece, titled A Walk Through the City, was published on my CD Transformations. It was my third composition, and at the time, in 1981, I had barely recognized that I was a composer. But I had made a clear decision that this piece was going to be a first conscious political expression through composing with environmental sounds. It was based on a poem of the same title written by Norbert Ruebsaat, my then husband. We were working at Co-op Radio, which was located at Pigeon Square, a small park in the middle of Vancouver’s so-called Downtown East Side, and thus in the middle of the worst scenes of addiction and homelessness in the city. At the time, the people who were suffering from addictions were mostly struggling with alcoholism. But nowadays it is the scene of increased mental health issues, a huge opioid crisis, and many tragic deaths.

A Walk Through the City was commissioned by the CBC. I decided to create a piece about this part of Vancouver, which I saw as an opportunity to broadcast voices that were not normally heard on the CBC or on commercial radio stations. I wanted to expose the real difficulties, the horrors of living in that area of town. I was aware of the risk that this piece might never be broadcast. Even though it was commissioned for the new music audience of the programme Two New Hours – that is, an audience that was used to musical and sonic experimentation – the programme was, from my perspective, still relatively staid and perhaps not prepared to expose its listenership to such harsh realities. I was going to work with the sounds that homeless people were exposed to on a daily basis; these are not exactly attractive to the ear and the project turned out to be quite a challenge. The following excerpt will give a first impression of the composition’s sonic atmosphere and may deepen – beyond words – the meaning of my subsequent commentaries about the piece and the compositional process (Sound example 1).

Sound example 1: A Walk through the City (1981), excerpt from 4'46” to 8'10” (3:24), https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17410246.

Norbert was not actually that happy with the poem. He felt it to be incomplete. But I liked it precisely because of that incompleteness: it gave room for the environmental sounds and the compositional process to ‘speak’ their part. We experimented with various reading expressions, but also – as you can hear in this excerpt – with some simple equalizations of the voice. In our first recording session in the studio, he read the poem with a type of poetic tone that he had acquired. But while I was working on the piece, I realized that this voice did not sound right within the louder, more chaotic soundscapes in parts of the piece. With the choice of environmental sounds I had made – the urban broadband, low frequency and raucous sounds, multiple sirens – the poetic voice simply did not cut through the noise in the way I wanted it to. ‘I need you to shout’, I said. ‘Can you come back into the studio and read the whole poem as if you were shouting at the listener?’ I then equalized his shouting voice, which gave it that megaphone quality.

It was an interesting learning experience for me to realize that the combination of spoken voice and the chosen environmental sounds simply was not working in certain parts of the poem. It was not giving me the energy that I wanted from the voice. And then in another part of the piece, it seemed totally appropriate that the words of the poem were whispered. In yet another part, Norbert’s softer and warm poetic voice did work. Depending on the atmosphere in the poem, the sonic relationship between the environmental sounds and Norbert’s vocal expression kept changing. None of this was clear to me before I started working on the piece and it was only revealed when hearing the sound combinations.

The choice of sounds was another aesthetic dilemma for me, because the soundscape in that area of town is noisy and chaotic. If I wanted to give a sense of what people were exposed to on a daily basis on the acoustic level, it was not exactly going to sound attractive. How then do you create a composition about such a place of suffering that attracts people’s ears so that they are drawn into the listening and are not tempted to turn off the radio? The composer in me wanted to offer a sonic/musical piece that does not repel the ears. I remembered a recording from the environmental sound archives of the World Soundscape Project Tape Library: screechy, high-frequency truck brakes in the midst of very heavy traffic. In my search for bearable sounds, it was rather ironic that I zeroed in on this recording. But I had had enough experience in the studio by that time that I sensed interesting results if I were to slow down (pitch shift) the brakes by a few octaves. It was easy to filter out the mostly low-frequency traffic and just work with the brake sounds. And indeed, my experimentation with a number of different speed changes resulted in these very beautiful and pure-sounding tones. Of course, when I mixed a variety of these different pitches together, it revealed my aesthetic choices as a composer, and I ended up with these rather melancholic sounds that can be heard in the part of the poem that speaks about the children. It was exactly this atmosphere of melancholy that I had searched for, an ambience that could perhaps draw in the listener, because it was quite beautiful. At least it was for me. Once I had discovered this sound, its tone guided me through the compositional process. It also relaxed me a bit regarding the aforementioned contradiction between a difficult, repelling soundscape and the composer’s desire to attract listening ears to the piece. That tone, so I sensed, could potentially soften listeners’ hearts towards a place like the Downtown East Side and towards this composition… and yes, perhaps the composition might have a chance to be broadcast on the CBC.

Having worked with environmental sound all my life, this kind of discovery has never really stopped. It is in the nature of the world’s sonic complexities that each recording is unique, originating in its very own place and time with its very own context, including the recording process itself and its technical specifications. It carries within it endless possibilities and surprises, and as a result has kept me absolutely fascinated and focused on working with environmental sound as a compositional language.

École polytechnique (1990)

Fast forward to 1989, when on 6 December, fourteen female students were shot to death by a twenty-five-year-old man in an act of misogynist violence at the École Polytechnique at the University of Montreal – a very shocking and at that time new and rare occurrence. Let’s listen to a five-minute interview from spring 2022 that was made about a week before my composition école polytechnique (1990) was released on my album Breaking News (Sound example 2). Listening to it will prepare the reader – hopefully in a constructive way – for the three excerpts from the composition that follow. The interview also elaborates on the tough compositional journey that I experienced while working my way into this piece and asking myself how to realize sonically/musically the occurrence of a massacre and its aftermath: the media reports, experiences of shock, ever-repeating cycles of grieving, and eventual steps towards healing. It elaborates further on the challenges with which I confronted the performers and especially the choir, something I had not anticipated while composing the piece.Footnote 7

Sound example 2: Interview with Brady Marks, 2022 (5:01), https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17458563.

Additionally, Sound example 3 provides a string of three excerpts from the parts of école polytechnique that I describe in the interview.

Sound example 3: école polytechnique (1990), three excerpts (6:30), https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17458638.

So, you can see how this could be a challenge for the choir. The other challenge was that it was an outdoor performance in Montreal on 3 November. Very risky. Jean Piché, when he commissioned me, said, ‘the performance is either going to happen or not’. But we were lucky, it was an overcast but relatively balmy day. Later that day, after the performance, the weather changed and it started to rain and snow.

As a composer, I am always somehow thinking about the listener. Of course, I am also my own audience, I am a listener in the process of composing. And through that listening, I inevitably connect to an audience. In the early years, there were big discussions about who our audience was, to whom we were speaking, and so on. I don’t really ask those questions anymore. I have basically figured out that if I do a composition, I am giving birth to something that is alive, and when it gets out there, it will either survive or not. The listeners will tell me; the audience will tell me. The event at the École Polytechnique was such a shock. All I knew was that I needed to speak up about it as a kind of protest, a tone that was very prevalent at that time in our age group. You can hear that the piece is pretty aggressive, pretty angry, urgently confronting the listener with the horror of the situation.

My programme notes describe it like this:

This piece is also about life and death in a more general sense. It is about human life rhythms, their violent destruction – destroyed with the same kind of violence that creates wars, kills people, abuses children and the natural environment; a violence that is born from violence, where experience of human warmth, compassion, and love is missing, where nothing is sacred or worth protecting – and it is about the recovery from such violence, a process of healing. école polytechnique is like a journey: it takes us from life (symbolized by heartbeat and breath on the two-channel audio) to violence, death, and aftermath, to the underworld of suffering and mourning, and finally to healing and a renewed energy for life.Footnote 8

That describes my journey as a composer, but at the same time these words are trying to invite the listener into this journey, making clear that it is not an easy one. With these words I was attempting to take care of the listener and to prepare them in some way. But for people who were affected by this event, who may have lost a dear one, this journey may be too hard, possibly unbearable – especially the section where the names of the victims are called out by the choir, like a prayer, together with the sound of the church bells. It’s pretty intense emotionally.

A review in the Toronto Star by William Littler stated, ‘an evocative score in any context, école polytechnique seemed to speak with special poignancy to the Montrealers who witnessed its premiere. In a sense, it spoke for them.’Footnote 9 These words resonate with my own intention that the piece should allow the audience to enter a process of grieving that could ultimately be healing. Everybody grieves differently, reacts differently to this kind of intensity. All I can say is that the listener in this case is offered a journey created from my perspective, with good intent, to release the horror into something more human in us that reaches deeper into our hearts. But I know that it could also be too difficult an experience, too tearing. In that case the listener may need to leave the performance.

I think it is not surprising that école polytechnique has not been performed much. It has just been released online, on the album Breaking News. Footnote 10 I would be very interested to hear what kind of impact the piece will have on listeners now, so many years later and so many experiences later where these kinds of shootings have happened over and over again in North America, unleashing fierce debates about gun control legislation. I would love to have discussions about the impact of this piece. Sometimes I feel that we need to talk about whether a piece like this works, is useful, constructive. It is really just one voice, my own compositional voice, that processes the stages of grieving. At the end, there is kind of a pickup of life again, an attempt to find the energy to go forward to living life again.

The Soundscape Speaks – Soundwalking Revisited (2021)

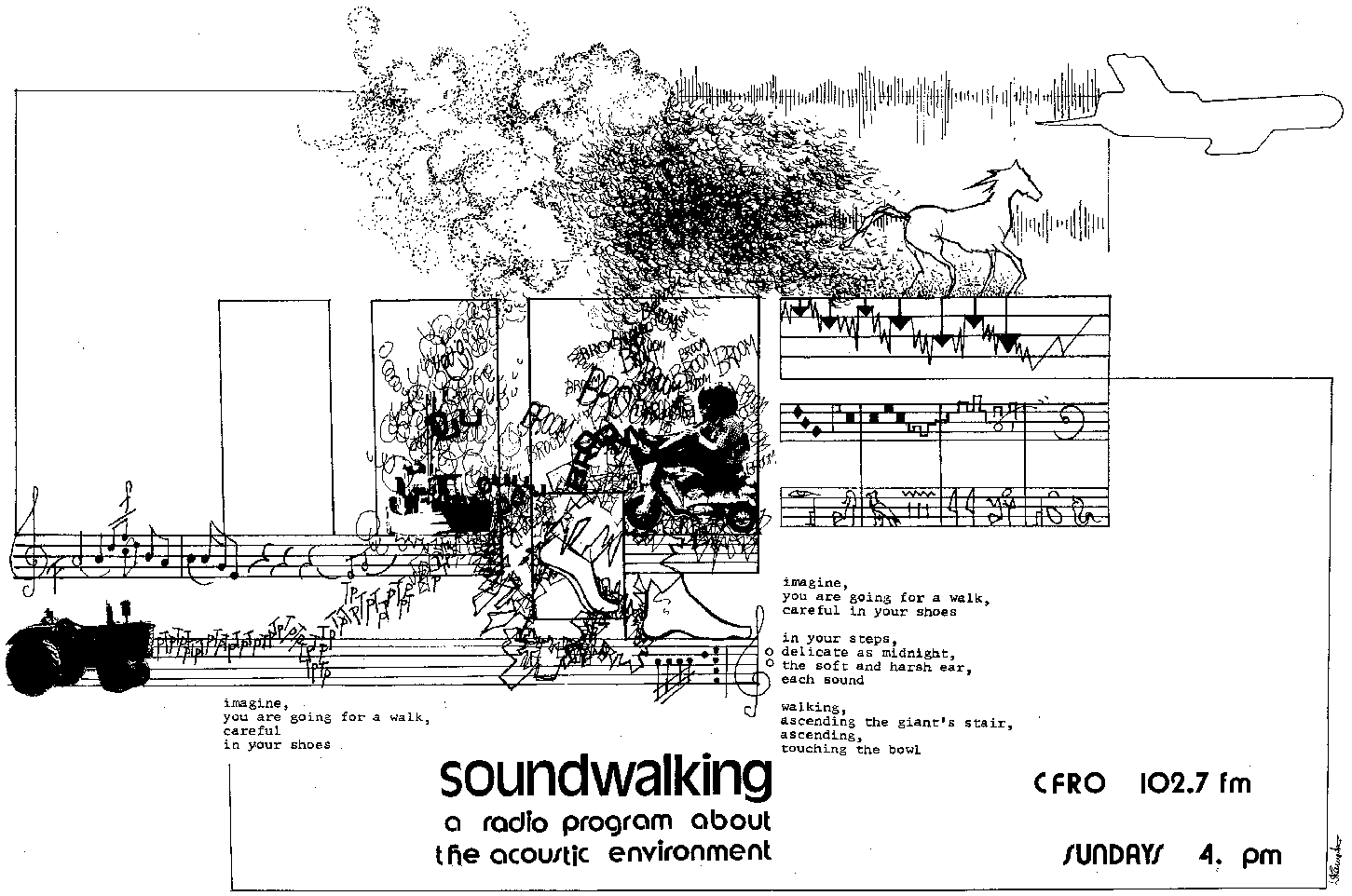

The last piece I want to discuss is one of my most recent compositions, entitled The Soundscape Speaks – Soundwalking Revisited. It was commissioned by the BEAST FEaST in Birmingham, UK, and premiered during the festival in April 2021. I was really happy about the opportunity to create this piece. Not only did it bring me back full circle to my Soundwalking show in 1978–79, for which I started to make weekly recordings and as a result learnt a lot about the field recording process as well as about broadcasting (Figure 1), it also gave me the opportunity to go through these and many more of my field recordings to try to figure out what to do with them, how I might archive or work with them. It was a fascinating and enjoyable process re-listening to over forty years of accumulated environmental field recordings right up to April 2021, a few days before the premiere. The piece is thirty-five minutes long and turns out to be a journey through my field recording style as it evolves over the years – plus the listener gets some insights into early compositional gestures of editing and mixing as well as some subtle hints of studio processing.

Figure 1. Soundwalking poster. Created by Liliane Karnouk, with a poem by Norbert Ruebsaat.

But actually the piece is also very straightforward. When I made the recordings for Soundwalking I would go out anywhere in and around Vancouver, spontaneously choosing a place on any given day, depending on the weather, my interest and mood, and whether I wanted to be in the middle of urban hustle and bustle or by the ocean, in a forest, or on a mountain. I would simply record whatever met my microphone ear. Right from the start I developed a style of speaking live into the microphone while I was recording the environment. I felt it important to be a kind of mediator between environment and radio listener.

From my work with the World Soundscape Project, I knew very well that when you broadcast environmental sound for any length of time and without any explanation, listeners will block it out after a while and the broadcast will become an ambient backdrop. This same dynamic happens in daily life: most often the sounds of the environment become a backdrop to our daily tasks and we may not even be aware what is entering our ears. And that is precisely what I did not want. It probably helped that it was unusual at that time to hear environmental sounds on the radio, which furthered my desire to educate radio listeners. I wanted people to become aware of the soundscape in which they lived. I also wanted them to become aware of the influence a soundscape can have on us, how we might like it or not like it, how we could change it. My voice had the function of describing all the things that a listener could not know purely by listening – like the weather, the time of year, the season – or it might even highlight certain things that were heard, asking for example, ‘did you hear that echo?’ It was a recording style that I developed and refined over the years, walking through an environment, always with a moving microphone, in a way already composing, making choices as I am being led by the sounds that are captured by the microphone. Of course, I am always monitoring with headphones when I record. At that time in the late 1970s, I had a large portable cassette recorder, one of the first Nakamichi recorders, two AKG microphones in stereo position, and big headphones. So I was very conspicuous, not like today when nobody notices that you are recording. I was often approached, mostly by men and children who were wondering what I was doing. When you monitor what you are recording, you are in fact composing on some level. Although I tended to make a distinction between field recording and composing with environmental sounds in the studio, my colleague and friend, the late Andra McCartney, always challenged me on this and said that soundwalking is in fact composing. For a while I resisted this idea and we had long debates about it. But of course she was entirely right. Creating a soundwalk, whether we record it or not, involves a kind of listening and decision-making that is a form of composing. When we bring a recording into the studio, the listening and composing process continues, if in a slightly different form. You are bringing the experience from the field with you and combining it with your recordings into – in my case – a one-hour radio programme. The Soundscape Speaks then extends that process and takes excerpts from the Soundwalking programme and many other later recordings, even excerpts of compositions, and re-composes them into a larger piece.

Sound example 4 occurs about twenty-six minutes into the piece. In the first two minutes we hear a type of collage of my voice speaking during the various field recordings, giving dates and recording locations, describing the way I record, revealing my recording process quite viscerally, as I basically follow my own ears.

Sound example 4: The Soundscape Speaks – Soundwalking Revisited, excerpt (5:19), https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17458686.

At the end of this excerpt, you can hear me pulling the microphone out of a pipe that I discovered by chance halfway up Tunnel Mountain above the town of Banff in Alberta, Canada – a pipe that led underground into a water reservoir and produced those gorgeous resonant and reverberant sounds. The same train horn that we heard acoustically altered and processed by the reservoir earlier in this excerpt, we now hear repeated in the open air, right after I pull the microphone out of the pipe. In hindsight, this piece speaks loudly and clearly about the one ethical issue that has dominated every aspect of my professional life, whether as radio broadcaster, composer, or writer: learning to listen to the world in ways that deepen our relationship to the environment and heighten our respect for nature and the environment as a whole, and that lead us to understand that we are part of it: we are part of nature, of the world.

This became very apparent to me when listening back to all these recordings: putting them side by side in this piece highlighted the fact that not only did my voice sound a lot younger once, but that its expression is different depending on the environment in which I am spending time. This was not intentional; it simply occurred as a natural response to where I was. A distinct difference in tone of voice and pacing is audible throughout the recordings, as if influenced and shaped by the atmosphere of any given place or moment. For example, in the quiet winter landscape my voice was extremely calm and quiet with long pauses between speaking, in order not to mask the subtler sounds of this location; in the hustle and bustle of a shopping environment, my voice projected more loudly, spoke faster and sometimes with a sense of irony; and in the very reverberant acoustics of a tunnel, it was loud and slow, trying to articulate every word clearly to the listener.

In other words, without me being aware of it, the ‘voices’ of the acoustic environment and my own vocal quality collaborated in highlighting the unique acoustic character and atmosphere of each place that was recorded. They revealed sonically what should be obvious to us all: that human beings and their environments are intricately intertwined with each other. If we learn to listen in depth to our interactions with soundscapes, we can hear when we are in tune with our environment and when we are not. It highlights sonically that human beings do not exist as separate entities in this world. Our connection to the world is expressed acoustically in the intonation and expression of our voices. We can hear it if we care to listen.

Concluding thoughts: building relations through sound and listening

It is only with hindsight that I can speak about my sound pieces as compositions that listen. In the years-long process of recording and composing with environmental sounds, I have experienced ever-new ways of perceiving the soundscape – in fact, ever-new ways of listening itself. Listening as

• being present and allowing discoveries and surprises to happen;

• a revelation of the places and times in which recordings are made;

• a pathway to speaking (composing) with and through the voices of the environment;

• coming into an ongoing and felt relation with the soundscape;

• sensing and accepting our unquestionable positioning inside the soundscape;

• exploring and understanding ways of living in a reciprocal relationship with the natural world.

Nowadays, we would no longer say that we want to help ‘giving voice’ or opportunities to so-called disenfranchised people, as we did in the early years of Co-op Radio. Instead, the task now is to engage in relationship building: relationships to the environment, to each other, to community. And this has implications for the larger context of climate change: that is, for the changes that need to be made in our relationship to and interaction with the natural environment and with each other. It also underscores why we need to listen extra seriously to Indigenous cultures who have always known the richness and value of nature and have lived accordingly. Despite years of silencing, loss of language, oppression, and poverty, many Indigenous cultures have retained a deep knowledge of how to live in reciprocity with the natural environment, or as Dylan Robinson puts it, how to live in a ‘deeply embodied/experiential relationship to culture and place’Footnote 11 and not treat it as something that needs to be conquered or exploited.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101027828 (project ONTOMUSIC), the Schulich School of Music of McGill University, and the Canada Research Chair in Music and Politics at the University of Montreal Faculty of Music. The funding bodies played no role in the development of this article, which reflects only the author’s view.