Highlights

-

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials for embolization of the middle meningeal artery (EMMA), a novel neuroendovascular therapy for chronic subdural hematoma.

-

EMMA is effective in reducing symptomatic recurrence, progression and/or reoperation.

-

EMMA is not associated with a greater incidence of serious adverse events, stroke or death.

Introduction

Chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) is a common condition, with an incidence of 20.6 per 100,000 person-years. Reference Feghali, Yang and Huang1 It disproportionately affects elderly populations and is often caused by minor trauma. It can cause headaches, confusion, decreased level of consciousness, weakness, aphasia or seizures.

Depending on the volume, mass effect and symptoms, CSDH has been treated either surgically (burr hole evacuation, craniotomy or subdural drainage ports) or conservatively (medical therapy or observation/serial imaging). Conservatively managed CSDH can progress in up to 34% of cases. Reference Foppen, Bandral, Slot, Vandertop and Verbaan2 After surgical evacuation, recurrence rates have been estimated between 10% and 20%. Reference Almenawer, Farrokhyar and Hong3

Recently, endovascular embolization of the middle meningeal artery (EMMA) has become an emerging therapy for CSDH. Reference Rudy, Catapano, Jadhav, Albuquerque and Ducruet4 While initially used in patients at high risk of recurrence, the indications have recently widened to all patients with CSDH. Although EMMA does not remove the hematoma or its mass effect, it is hypothesized to de-vascularize the subdural membrane and prevent recurrence or progression, Reference Rudy, Catapano, Jadhav, Albuquerque and Ducruet4 allowing for spontaneous resorption over time.

EMMA has been used in cases of small, asymptomatic CSDH not requiring surgery, Reference Rojas-Villabona, Mohamed and Kennion5 as well as in cases of CSDH requiring surgical evacuation. Reference Lam, Selvarajah and Htike6 A recent systematic review of non-randomized studies found that EMMA reduced the risk of recurrence from 23.5% to 3.5% (RR 0.17). Reference Dian, Linton and Shankar7 However, at the time of publication, there had not been any prospectively conducted randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Recently, a number of multicenter RCTs have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of EMMA for reducing recurrence or progression in CSDH. Reference Lam, Selvarajah and Htike6,Reference Liu, Ni and Zuo8–Reference Fiorella, Monteith and Hanel10 A systematic review and meta-analysis of these trials has yet to be performed.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of available data from RCTs comparing the efficacy of EMMA in addition to standard of care versus standard of care alone. The primary endpoints included recurrence or progression of CSDH.

Search strategy

We performed a systematic review based on our predefined protocol Reference Wang, Shakil and Drake11 (PROSPERO CRD42024512049), which is available online (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024512049) and in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement and Cochrane Handbook. Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt12

Two authors (APW, HS) independently searched citations from MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane and ClinicalTrials.gov (National Library of Medicine) without language restriction. We used the search terms (all fields, keywords and MeSH terms): subdural hematoma, embolization, meningeal, endovascular and clinical trial (see Appendix 1 in the Supplement).

Study selection

Two authors (APW, HS) independently evaluated studies identified by the literature search. Disagreements were to be resolved by consensus or a third reviewer. Duplicates and ineligible studies were discarded using a web-based systematic review platform, Covidence (Melbourne, Australia). We included RCTs of adult participants (≥18 years of age) with radiographic diagnosis of chronic or subacute subdural hematoma (SDH) that compared EMMA and standard care versus standard care alone. Studies had to have completed enrollment, include at least 10 patients, have a follow-up period of at least 90 days and be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

The intervention of interest was the use of EMMA in addition to standard of care. The control group was treated with standard of care alone, which could include observation, medical therapy and CSDH evacuation.

Data extraction

Two authors (APW, HS) extracted the study design, recruitment information, inclusion/exclusion criteria, randomization characteristics, patient demographics, treatment details, primary and secondary endpoints and adverse events from the manuscript text, pre-published protocols (available online), figures, tables and supplementary files.

Risk of bias/quality assessment

Two reviewers (APW, MR) independently performed quality assessment of included studies. Disagreements were to be resolved by consensus or a third reviewer. The Cochrane ROB 2 tool Reference Sterne, Savović and Page13 was applied to assess the risk of bias. The GRADE approach Reference Guyatt, Oxman and Vist14 was used to appraise the limitations, inconsistency of results, indirectness of evidence, imprecision and publication bias of each outcome for each study.

Data synthesis and analysis

Data for primary groups and subgroups were extracted from the main articles’ figures, tables and supplementary files. In some instances of data that were not included in the quantitative meta-analysis, median values were approximated as mean values as the distribution was symmetric. Reference Higgins, Thomas and Chandler15 All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with an a priori specified significance level of P = 0.05 for two-tailed tests. Descriptive statistics were reported as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and count with proportions for categorical variables. Variables for which at least two studies had data available were tabulated and displayed (Tables 1 and 2).

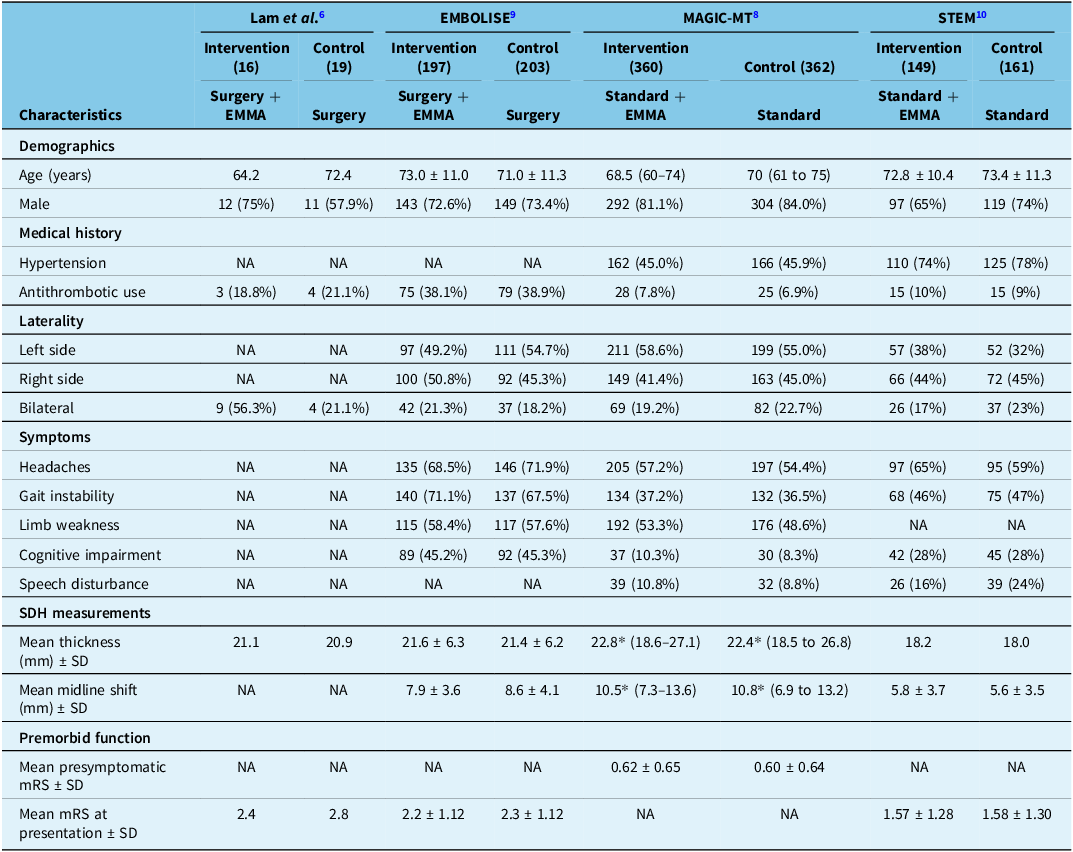

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics among trials

EMMA = embolization of the middle meningeal artery; mRS = modified Rankin Scale; SDH = subdural hematoma.

*Median values used as means given symmetrical distribution of data.

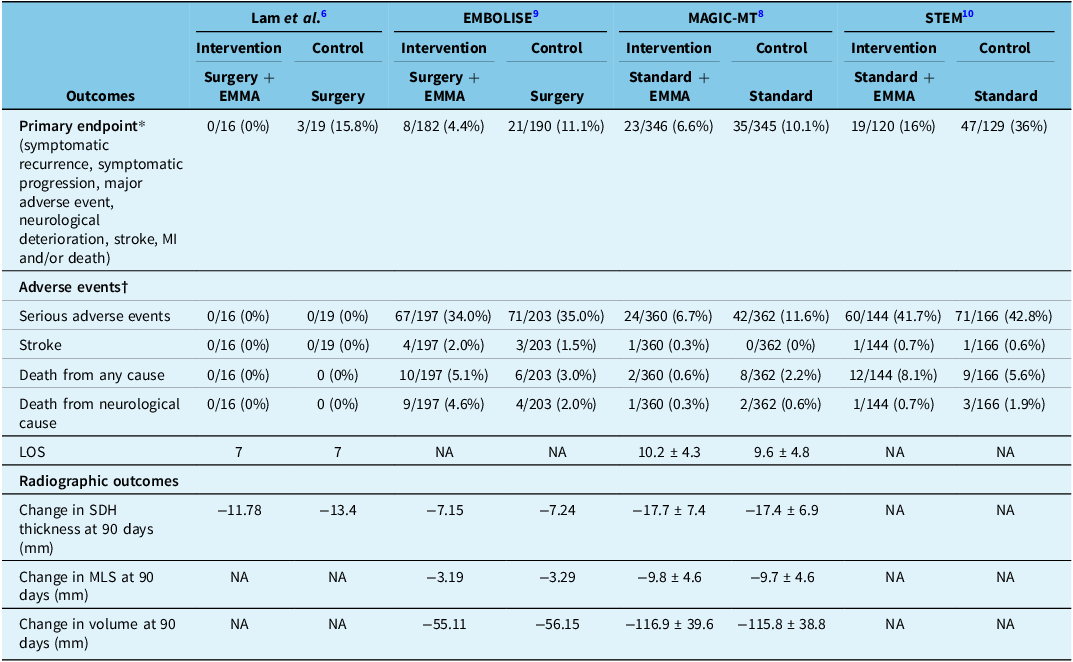

Table 2. Treatment outcomes among trials

EMMA = embolization of the middle meningeal artery; LOS = length of stay; MI = myocardial infarction; SDH = subdural hematoma; MLS = midline shift.

*Observed data (no imputed data) used. Denominators exclude patients who exited the trial before follow-up completion for reasons other than death and did not meet the primary endpoint before exiting or had protocol violations (did not undergo embolization, crossed over or declined follow-up CT).

†Denominators include all enrolled patients.

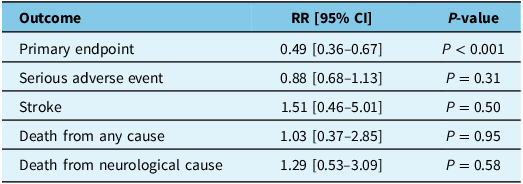

Outcomes for which at least three studies had data available were meta-analyzed (Table 3). Effect estimates of EMMA were estimated and pooled as described in our published protocol. Reference Wang, Shakil and Drake11 In brief, we estimated the relative risk (RR) of each study outcome as reported from individual studies per treatment protocol. The pooled RR of each outcome, along with a 95% confidence interval (CI), was estimated using the meta version 8.0-2 package.

Table 3. Meta-analysis results of primary and safety endpoints

RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval.

Heterogeneity across studies was evaluated with the Cochran’s Q and I 2 statistics, with p ≤ 0.10 or I 2 >50% considered significant heterogeneity. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman16 In cases of significant heterogeneity, a random-effects model using the DerSimonian-Laird method was used to estimate pooled effects. In the absence of significant heterogeneity, a fixed effect Mantel–Haenszel model was used. Reference Higgins, Thomas and Chandler15 For any outcome with a significant effect, we also pooled observed data to estimate the unweighted risk difference using the same methodology to estimate the number needed to treat (NNT) using the inverse of the absolute mean risk difference. We planned to assess publication bias using Egger’s test and funnel plots Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder17 if there were at least 10 trials in the meta-analysis.

Results

Search results

The search strategy revealed a total of 102 studies (Figure 1). Duplicate records and ineligible studies were removed. The remaining 80 titles and abstracts were reviewed by two authors (APW and HS); the majority were irrelevant or non-randomized studies. A total of five remaining articles were selected for full-text review. One article was removed since it was an interim report of an ongoing trial with only six weeks of follow-up. Data from 4 remaining studies were included in the meta-analysis, consisting of a total of 1468 patients.

Figure 1. Flowchart of literature review and study selection for meta-analysis.

Description of trials

Four recently published RCTs were identified (Lam et al. 2023, Reference Lam, Selvarajah and Htike6 EMBOLISE 2024, Reference Davies, Knopman and Mokin9 MAGIC-MT 2024, Reference Liu, Ni and Zuo8 STEM 2025 Reference Fiorella, Monteith and Hanel10 ), evaluating the efficacy of EMMA combined with standard care versus standard care alone. A total of 1468 patients (723 intervention group, 745 control group) were enrolled among the 4 trials, and a total of 1347 patients (664 intervention group, 683 control group) had data available for the primary endpoint. Lam et al., EMBOLISE and MAGIC MT employed recurrence or symptomatic progression of CSDH as their primary endpoint, while STEM included recurrence and progression, as well as disabling stroke, myocardial infarction (MI) and neurological cause of death. For their embolic agents, EMBOLISE and MAGIC-MT only used Onyx (ethylene vinyl alcohol co-polymer dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland), while STEM used Squid (ethylene vinyl alcohol co-polymer with micronized grain size of tantalum powder, Balt, Montmorency, France). Lam et al. employed Onyx, Squid, PHIL (precipitating hydrophobic injectable liquid, Microvention, Aliso Viejo, USA) and 25% n-butyl cyanoacrylate (n-BCA) (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) with 75% Lipiodol (Guerbet, Villepinte, France). Descriptive details are available in Table S1.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of the intervention group, 136 (19%) of patients were on antithrombotics, a similar proportion to the 138 (19%) control patients. The mean preoperative thickness of the CSDH ranged from 18.2 mm in STEM to 22.8 mm in MAGIC-MT in the intervention groups. For the control groups, the mean thickness ranged from 18.1 to 22.4 mm, respectively.

Radiographic outcomes

In three studies (Lam et al., EMBOLISE and MAGIC-MT), various pre- and post-radiographic outcomes of the SDH (volume, thickness and midline shift) were available (Table 2). MAGIC-MT noted the largest reduction in SDH thickness across both the intervention and control groups, being a mean of 17.7 and 17.4 mm, respectively. EMBOLISE noted the lowest magnitude difference, being −7.15 mm and −7.24 mm in the intervention and control groups, respectively.

Treatment details

Treatment details are summarized in Table S3. In Lam et al. and EMBOLISE, EMMA was used as an adjunct to surgery, as all patients were intended to undergo surgical evacuation of the SDH via burr hole or craniotomy. In MAGIC-MT and STEM, most patients (78.3% and 61.0%, respectively) underwent SDH evacuation via burr hole or subdural evacuation port system (patients requiring craniotomy were excluded), but many patients managed non-surgically were included as well, where EMMA was used as a primary or standalone therapy.

Primary endpoint

There were 664 (92.6%) patients in the EMMA group and 683 (91.1%) patients in the standard therapy group that completed follow-up for assessment of their respective primary endpoints. Two trials (EMBOLISE and STEM) were positive for their primary endpoint, while two (Lam et al. and MAGIC-MT) were negative (but there was a trend toward significance). After pooling, EMMA was found to significantly reduce the risk of the primary endpoint (RR 0.49 [95% CI 0.36–0.67]; P < 0.001) (Figure 2, Table 3). The primary endpoint was met in 50/664 patients (7.5%) in the intervention group compared to 106/683 patients (15.5%) in the control group, with an absolute risk difference of 8% and NNT of 13.

Figure 2. Forest plot showing meta-analysis of the primary endpoint (see Table 3) from the four trials. Given the low heterogeneity (I2 < 50%), a fixed effects model was used.

Secondary endpoints

Observations from 717 patients in the intervention group and 750 patients in the control group were pooled to assess the risk of a serious adverse event (SAE), stroke, death from any cause and death from a neurological cause. The rate of SAEs was 151/717 (21.1%) in the intervention group and 184/750 (24.5%) in the control group (RR 0.88 [95% CI 0.68–1.13]; P = 0.31). The rate of stroke was 6/717 (0.8%) in the intervention group and 4/750 (0.5%) in the control group (RR 1.51 [95% CI 0.46–5.01]; P = 0.50). The rate of death from any cause was 24/717 (3.3%) in the intervention group and 23/750 (3.1%) in the control group (RR 1.03 [95% CI 0.37–2.85]; P = 0.95). The rate of neurological death was 11/717 (1.5%) in the intervention group and 9/750 (1.2%) in the control group (RR 1.29 [95% CI 0.53–3.09]; P = 0.58). After pooling, there was no significant difference found between EMMA with standard therapy compared to standard therapy alone with respect to any of the secondary endpoints (Figure 3, Table 3).

Figure 3. Forest plots showing meta-analyses of serious adverse events, stroke, death from all causes and death from neurological causes (see Table 3) from the four trials. For stroke and death from neurological causes, there was low heterogeneity (I2 < 50%), and a fixed effects model was used. For serious adverse events and death from all causes, there was moderate heterogeneity (50% < I2 < 75%), and a random effects model was used.

Appraisal of evidence

Risk of bias for each trial was evaluated using the Cochrane ROB 2 tool Reference Sterne, Savović and Page13 by two authors (APW and MR) and displayed in the Supplement (Table S2 and Figure S1). Although they were overall well-conducted trials, they each carried some concerns of bias. Given the technical nature of EMMA, no study was able to blind the interventionist or patient to the procedure, and thus, this domain was at risk of bias. Although the studies employed independent assessors to evaluate post-embolization radiographic outcomes, the radiopaque material is visible to them as well as to surgeons and radiologists involved in the clinical care of the patient.

When analyzed on a per-outcome basis as per the GRADE criteria, Reference Langer, Meerpohl, Perleth, Gartlehner, Kaminski-Hartenthaler and Schünemann18 the primary endpoint was of moderate quality evidence, owing to the limitations present in all studies with blinding. In addition, the STEM trial combined symptomatic recurrence, progression requiring repeat surgery, MI, disabling stroke and death from neurological causes into a single outcome; the other three trials used recurrence or progression that was symptomatic or required evacuation as their primary endpoint. However, given data were provided on these other variables, it was possible to coalesce them into a single value for the meta-analysis, thereby minimizing heterogeneity as demonstrated by the low I 2 score of 0.0%.

SAEs did have significant heterogeneity (I 2 = 50.2%) and had greater inconsistency, given that MAGIC-MT reported a statistically significant reduced RR while EMBOLISE and STEM reported CIs that overlapped with no effect. Death from any cause also had heterogeneity (I 2 = 58.1%), while death from neurological causes was not inconsistent but more imprecise given the large CIs. Stroke was imprecise in its effect measure but had minimal heterogeneity in the pooled estimate.

Publication bias was not assessed using Egger’s test and funnel plots as there were fewer than 10 studies. Reference Higgins, Thomas and Chandler15

Discussion

Herein, we report the first systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs to assess the efficacy of EMMA, a novel neurointerventional therapy. We used a predefined and previously published protocol Reference Wang, Shakil and Drake11 (PROSPERO CRD42024512049), which is available online (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024512049)

While two studies (EMBOLISE, STEM) were positive, the other two (Lam et al. and MAGIC-MT) were negative for their primary endpoint, likely due to being underpowered. Our meta-analysis helps to overcome the limitations of these underpowered trials. Our results demonstrate that EMMA, in conjunction with standard care, significantly decreases the risk of a conglomerate primary endpoint of symptomatic progression, mortality and stroke, MI or neurological deterioration. This includes patients who are undergoing primary EMMA (standalone therapy) as well as adjunctive EMMA (before or after evacuation of CSDH).

Our secondary endpoint analysis further suggests no increased incidence of SAEs, death due to any cause or from neurological causes or stroke with EMMA. The results of our investigation address an important knowledge gap in this novel therapeutic intervention for CSDH.

EMMA is believed to interrupt the neovascularization of the CSDH by the middle meningeal artery. Reference Nakaguchi, Tanishima and Yoshimasu19 In CSDH, meningeal inflammation promotes vascular congestion of hematoma membranes, resulting in persistent bleeding and hematoma recurrence. Reference Moshayedi and Liebeskind20,Reference Shapiro, Raz, Nossek, Chancellor, Ishida and Nelson21 This explains the observation that despite evacuation, many patients experience CSDH recurrence or progression. Reference Almenawer, Farrokhyar and Hong3 This pathophysiology is the impetus for the recent widespread interest in EMMA. Reference Takahashi, Muraoka and Sugiura22

Due to an increasingly elderly population and greater indications for antithrombotics, CSDH is projected to become the most common cranial neurosurgical condition as early as 2030. Reference Balser, Farooq, Mehmood, Reyes and Samadani23 EMMA is estimated to become the most commonly performed neuroendovascular procedure by 2029. Reference Rai, Link and Lakhani24 As a result, understanding the efficacy of EMMA is crucial, highlighting the importance of the recent randomized trials and this meta-analysis.

Differences in primary endpoint

The four trials employed different measures of outcome, which are similar but not equivalent. In Lam et al. and EMBOLISE, the primary endpoint was SDH recurrence or progression requiring repeat surgery within 90 days; in MAGIC-MT, symptomatic SDH recurrence or progression within 90 days; and in STEM, SDH recurrence or residual (>10 mm), reoperation, major disabling stroke, MI or neurological death within 180 days. In most centers, symptomatic recurrence or progression would be an indication for surgical evacuation, and so the primary endpoints of Lam et al., EMBOLISE and MAGIC-MT are in fact quite similar. The main difference is that STEM included patients with stroke, MI and death. The trials did not publish individual patient data to permit meta-analysis with a unified and equivalent primary endpoint, and therefore, we meta-analyzed whatever outcomes each trial defined as their respective primary endpoint.

Liquid embolic agents

The four studies used different liquid embolic agents. Two (EMBOLISE and MAGIC-MT) used Onyx, while STEM used Squid. In Lam et al., various liquid embolic agents (at the discretion of the interventionalist) were used, including Squid, Onyx, PHIL and n-BCA. According to a recent meta-analysis comparing differing embolic agents, including Onyx, PVA, coils and n-BCA, Reference Ku, Dmytriw and Essibayi25 Onyx was demonstrated to have the lowest rates of recurrence, reoperation and complications, while PVA had slightly greater complications, potentially attributable to their greater distal penetration and thus higher risk of obstructing collaterals. Reference Ku, Dmytriw and Essibayi25 However, they did not include any studies with Squid, the agent of choice in STEM, a positive trial.

Standalone versus adjuvant embolization

Lam et al. and EMBOLISE were the only studies where all patients were intended to undergo surgical evacuation of the SDH via burr hole or craniotomy; in other words, EMMA was used as a surgical adjunct, either before or after CSDH evacuation. In MAGIC-MT and STEM, most patients (78.3% and 61.0%, respectively) underwent SDH evacuation, via burr hole or subdural evacuation port system (patients requiring craniotomy were excluded); however, a significant proportion of patients did not undergo CSDH evacuation, and therefore, EMMA was used as a primary or standalone therapy to reduce the risk of requiring evacuation. While STEM published separate outcomes data for their surgical and non-surgical groups, MAGIC-MT did not; therefore, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis to determine whether EMMA has more benefit as a standalone therapy or as an adjunct to surgery.

Among patients undergoing adjunctive EMMA, it remains unknown whether there exists a difference in efficacy whether EMMA is performed prior to surgery (neo-adjuvant) or after surgery (adjuvant). One currently unproven hypothesis is that a greater degree of embolic agent penetration into the subdural membranes can be achieved when EMMA is performed prior to surgery; this warrants further study with patient-level data from the RCTs, as there is an association between greater penetration and improved hematoma resolution. Reference Ma, Hoz and Doheim26 While EMBOLISE and MAGIC-MT reported on the degree of proximal versus distal penetration, Lam et al. and STEM did not, and we were therefore unable to meta-analyze the degree of penetration. In addition, EMBOLISE and MAGIC-MT did not report on any association between the degree of penetration and the primary endpoint.

Follow-up period

In Lam et al., EMBOLISE and MAGIC-MT, the follow-up period was 90 days, whereas in STEM, the follow-up period was 180 days. Although this represents a difference in outcomes, >85% CSDH recurrence and progression Reference Schmidt, Gørtz, Wohlfahrt, Melbye and Munch27 and >95% of CSDH retreatments Reference Nazari, Golnari, Metcalf-Doetsch, Potts and Jahromi28 occur within 90 days. It is therefore reasonable to compare the 90-day outcomes from Lam et al., EMBOLISE and MAGIC-MT to the 180-day outcomes from STEM.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is the use of a composite primary endpoint, which is discussed in detail above. In addition, our meta-analysis includes patients who underwent primary (standalone) EMMA, as well as EMMA as an adjunct to surgical evacuation. Furthermore, there was no characterization of the radiographic appearance of subdural membranes in these RCTs, which has been previously shown to be associated with higher recurrence rates. Reference Liu, Cao, Ren, Zhou and Yang29 All included studies had some degree of bias owing to the inability to blind the interventionalists and patients. Because of the novelty of EMMA, the number of RCTs included is small. Finally, it is impossible to assess the long-term durability and safety of EMMA as the trials included have yet to report any long-term follow-up data beyond 180 days.

Future work

A meta-analysis with individual patient-level data in collaboration with the trial investigators should be performed to characterize specific subgroups of patients (elderly, anticoagulated, etc.) who benefit the most from EMMA and to determine the safety profile and adverse events of the intervention. In addition, a separate analysis of surgically and conservatively managed CSDH patients should be undertaken to understand the relative benefit of primary versus adjunctive EMMA. Finally, given the high cost of neuroendovascular procedures, economic analyses should be performed to determine the financial impact of EMMA compared to standard therapy given our new understanding of an NNT of 13.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis of four RCTs demonstrates that EMMA is effective in reducing the primary endpoint (symptomatic recurrence, symptomatic progression, major adverse event, neurological deterioration, stroke, MI and/or death) among patients with CSDH.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2025.10467.

Data availability statement

All data were extracted from peer-reviewed publications. Extracted data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

APW, HS and BJD: study conception. APW and HS: protocol design. APW and HS: literature search, data collection. HS: data analysis. APW, MR, DB and HS: data interpretation. APW, MR and HS: writing – original drafting. APW, HS, MR, SBN, DB, TMB, RSH, HJL, RF and BJD: writing – draft review.

Funding statement

There was no funding for this study.

Competing interests

We declare no competing interests.

Presentations

This abstract was previously presented as an oral presentation at the 2024 Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery Annual Meeting, Colorado Springs, CO, USA.