Introduction

This paper investigates cross-generational variable subject expression (otherwise known as “null subject”) in heritage Vietnamese. Subject pronouns in Vietnamese are not a closed class, but rather are productively derived from a system of kin terms, personal pronouns, and personal names (cf. Song & Nguyen, Reference Song and Nguyen2022). These forms can be expressed or unexpressed, as Example (1) illustrates.

Of all the options, kin terms are the most commonly used in speech. While personal pronouns and proper names in Vietnamese have been said to imply “a lack of deference and high degree of arrogance toward the addressee and/or third-party pronominal referent of superior age” (Ngo, Reference Ngo2006:4), kin terms are said to show a “very deep concern for respect and good feeling” among the interlocutors (Clark, Reference Clark, Tran, Nguyen and Le1988:21). As such, younger speakers are obliged to use kin terms rather than proper names and personal pronouns when speaking to or about their seniors. This is somewhat similar to the honorific system in Japanese but marks a striking difference from languages like English or Chinese, where pronouns are neutral.

Our study is motivated by several key observations. First, subject expression in Vietnamese is pragmatically conditioned by factors such as formality, intimacy, and social relationships—dimensions that are often less clearly defined in diaspora contexts than in the homeland (Tuc, Reference Tuc2003:27-28). Second, there is no straightforward correspondence between the pronoun systems of the contact languages, Vietnamese and English, complicating transfer and alignment. Finally, although Vietnamese is commonly classified as a language with “radical null subjects” (Biberauer et al., Reference Biberauer, Holmberg, Roberts and Sheehan2010), the linguistic and social factors underlying this variability remain underexplored. This study, therefore, seeks to address the following research questions:

1. What are the linguistic and social factors that significantly condition variable subject expression in heritage Vietnamese?

2. Is there a difference across generations concerning such conditions?

In doing so, we first sketch out the linguistic and cultural landscape of the community before reviewing some previous works on subject expression in different contexts. We then discuss the data and approach that we use before presenting our results and discussion.

The Canberra Vietnamese community

The community of interest here is the Vietnamese migrant community in Canberra, Australia—a young yet well-established community. The subjects of investigation are late bilingual immigrants, whom we refer to as first-generation speakers (Gen1), and early bilinguals raised in Canberra, whom we refer to as second-generation speakers (Gen2). It is worth making it clear that both Gen1 and Gen2 are considered Vietnamese “heritage language speakers” in the present work. Although different researchers still have different definitions of what the “heritage” component entails, most agree that a heritage language is not a result of any linguistic “deficit” but rather a complete system on its own (e.g., Aalberse et al., Reference Aalberse, Backus and Muysken2019; Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2018). For immigrant early-bilingual heritage language speakers (Gen2) in particular, the sole focus on divergence from a monolingual baseline can be rather meaningless, given that the input for their heritage language acquisition may come from the late bilinguals (Gen1) who are themselves outside their monolingual milieu (Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2018:15-17; Polinsky & Scontras, Reference Polinsky and Scontras2020:7; Sim, Reference Sim2023:2344; Sim & Post, Reference Sim and Post2024:1290-1293). In this sense, a study of an immigrant heritage language is not just a study of early bilinguals per se, but is in fact an enquiry into the transition from Gen1 to Gen2 speakers.

Studies in language contact have shown that the linguistic landscape of a migrant community is likely to be affected by several distinct characteristics, most notably: the circumstances of arrival; the age at arrival; and the level of integration into the host society. Due to the political tension in Australia following the fall of Saigon in 1975, the Vietnamese community here mainly built their life by clustering with each other, setting up family businesses and services in the Vietnamese/Chinese-dense suburbs where they did not have to communicate in English on a regular basis. Their need to congregate has been reported to be a result of “on the one hand, experiences of racism and social exclusion in Australia, and on the other, the desire to be close to compatriots and to rebuild a sense of community” (Carruthers, Reference Carruthers2008:102). It is thus no surprise that Vietnamese is particularly well-maintained within this diaspora (Ben-Moshe & Pyke, Reference Ben-Moshe and Pyke2012).

After the continuous arrival of Vietnamese refugees, a new generation of Vietnamese migrants began to arrive in Australia in the mid-1990s, primarily made up of international students, entrepreneurs, and specialist workers (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022). The Vietnamese language used in Australia is thus a combination of Old Saigon Vietnamese, maintained mostly by refugees, and modern Vietnamese homeland varieties from different sources, primarily spoken by new migrants.

In Canberra, although the population is still largely English-dominant (71.3% of locals speak only English at home), Vietnamese remains the third most popular heritage language spoken at home (n = 4082), after Mandarin Chinese (n = 12,149) and Nepali (n = 5689). Members of the Vietnamese community in Canberra, like many other inhabitants of the city, are relatively young, highly paid, and highly educated. Contrary to the densely populated cities of Sydney or Melbourne, where Vietnamese speakers tend to cluster in neighborhoods and are employed in nonspecialist or family businesses, most Vietnamese speakers in Canberra work in education or the public sector, or have a partner doing so (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022).

Members of the community engage in regular interactions with each other at a prominent Vietnamese language school in Dickson, North Canberra. Participation extends beyond children and parents to include teachers and administrative staff, often international students or retired community members. Existing members frequently introduce new Vietnamese speakers, fostering new friendships and expanding the community. These school-based interactions form a strong practical and emotional network that extends beyond the classroom, supporting a range of community-bonding activities such as charity stalls, weekly choir practice, karaoke nights, variety shows, and lễ phát phần thưởng ‘traditional end-of-year award ceremonies.’ These shared experiences play a key role in building and maintaining the social fabric of the group (Milroy, Reference Milroy1987:109-138; Wenger, Reference Wenger1998:72-73).

Although no studies have specifically examined Canberra-Vietnamese attitudes toward the homeland, a national survey of 466 Vietnamese speakers in Australia found that while 88% identified as Vietnamese, only 51.5% felt “close” or “very close” to Vietnam. A significant minority (34%) expressed ambivalence, and a smaller group reported feeling “distant” or “very distant” (Ben-Moshe & Pyke, Reference Ben-Moshe and Pyke2012:30). This emotional distance was echoed in a follow-up study five years later, which reported “very weak ties to Vietnam” across various domains, including travel, political engagement, and remittances (Baldassar et al., Reference Baldassar, Pyke and Ben-Moshe2017:938).

Such emotional detachment may also have linguistic implications. Despite high reported levels of Vietnamese language proficiency—90% of respondents claimed strong skills—the so-called Tiếng Việt Cộng Sản ‘Communist Vietnamese variety’ remains a contentious issue. It was even the focus of three consecutive sessions on the Australian Vietnamese Radio Network (Nguyen, Reference Nguyen2012:87). Overall, while Vietnamese identity and language use remain strong in the diaspora, they are maintained as distinct from the homeland.

Null subjects

Subject expression in Vietnamese

Vietnamese was previously classified as a radical null subject language (Biberauer et al., Reference Biberauer, Holmberg, Roberts and Sheehan2010:8), that is, a language that permits the omission of pronominal forms without verbal agreement of any kind. Other languages that also display this behavior include Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Thai, as well as some others concentrated in Asia and Africa. The key trait that distinguishes Vietnamese from other radical pro-drop languages is that anaphoric reference in Vietnamese can be established not only by reduced pronominal forms but also by kinship terms, as we previously saw in Example (1).

The rationale for treating kin terms as pronouns in Vietnamese rests on two key observations, as outlined in Ngo (Reference Ngo2019). First, when used pronominally, kin terms lose their literal kinship meanings and instead index social features such as gender and relative age. For example, in Example (1b), chị does not mean ‘sister’ but signals that speaker B is female and older than speaker A. Second, these pronominal kin terms can appear in bare form or with a demonstrative (e.g., ông ấy, literally ‘that old male person’), where the demonstrative functions anaphorically, referring to a discourse antecedent with the appropriate social attributes. These features set kin terms apart from ordinary lexical noun phrases, which typically lack social indexing and cannot be modified by demonstratives in this way.

Similarly, Vietnamese personal names, when used pronominally, differ from their use in many other languages, where they typically serve as fixed third-person referents akin to lexical NPs. In Vietnamese, however, personal names can flexibly index first, second, or third person, as well as relative age and social status, functioning much like pronominal kin terms. They are also highly productive in discourse, frequently occupying pronominal positions. In contrast, lexical NPs in Vietnamese lack this grammatical flexibility and do not carry the same discourse prominence.

This rich indexicality of pronominal subjects in Vietnamese imposes additional pragmatic constraints on their use in discourse.Footnote 2 Notably, it is generally considered inappropriate for younger or lower-status speakers to omit first- and second-person pronominal forms (Nguyen, Reference Nguyen1997:96). Ton (Reference Ton2018:201) supported this by reporting that 98.5% (n = 208) of subject drops involving terms of address in her study occurred either between speakers of the same generation or from older to younger speakers. Likewise, Le (Reference Le2011:284) observed in a study of 64 natural utterances that second-person kin terms—used as forms of address—must be overtly expressed to convey proper respect. These Vietnamese-specific pragmatic norms are crucial conditioning factors that need to be accounted for in data analysis.

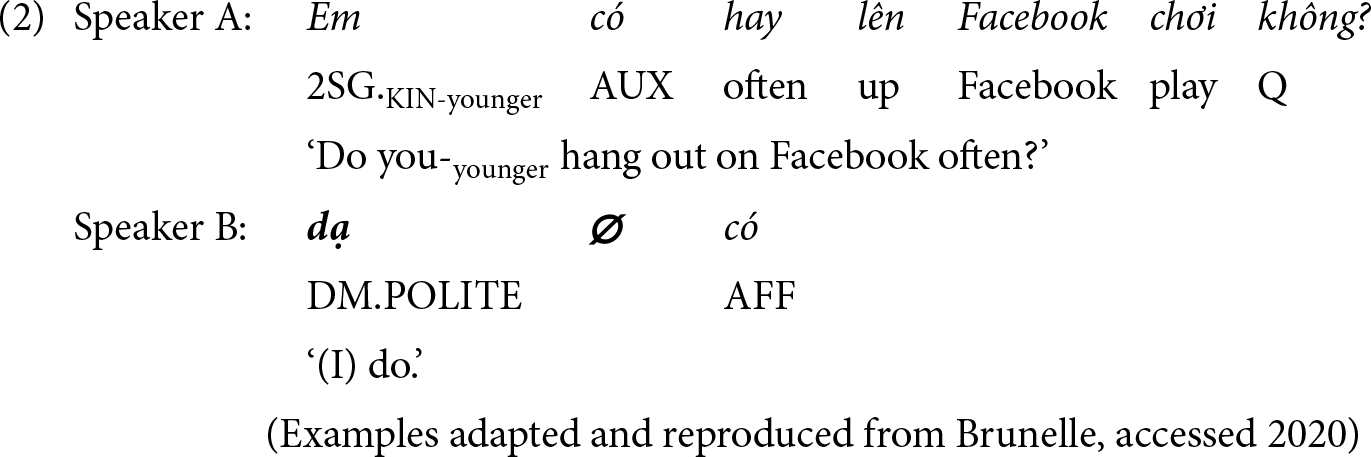

It is important to note, however, that this pragmatic constraint can be alleviated in several ways. Specifically, in spoken Vietnamese, the politeness markers dạ (utterance initial), vâng (utterance initial, Northern varieties), or ạ (utterance final) are often used to offset first-person pro-drop by younger generations. This practice is demonstrated in Example (2):

Here, the 2SG pronominal form em produced by Speaker A indicates that Speaker B is younger/socially inferior to Speaker A. Although Speaker B dropped the 1SG pronominal form in her response to A, the construction would still be considered appropriate, as the discourse marker dạ offsets the load for politeness. It is also crucial to note that this politeness-offset mechanism only works for first-person, but not for second-person pro-drop—which is strongly resistant to being dropped by younger/lower-ranked speakers, even in the presence of politeness markers of all kinds (Nguyen, Reference Nguyen1997:211). As such, we can expect that the second-person is least likely to be left null by Gen2 speakers.

Previous work on null subjects across generations

Successful transmission of subject pronouns appears to be variety-specific, as shown by contrasting results across different contact varieties (cf. Silva-Corvalán, Reference Silva-Corvalán1994:163 for Spanish; Margaza & Bel, Reference Margaza and Bel2006:421-425 for Greek; Sorace & Filiaci, Reference Sorace and Filiaci2006:353-356 for Italian). For example, Otheguy et al. (Reference Otheguy, Zentella and Livert2007) found that Spanish speakers who arrived in New York City after age 16 and lived there less than six years produced significantly more null subject pronouns than New York City-born second-generation speakers. They attributed this to widespread bilingualism among the second generation, accompanied by reduced Spanish proficiency and use (Otheguy et al., Reference Otheguy, Zentella and Livert2007:795). In contrast, Torres Cacoullos and Travis (Reference Torres Cacoullos and Travis2018:127) found continuity rather than change when comparing contemporary Spanish in New Mexico with an earlier stage of the same variety.

Nagy (Reference Nagy2015) also highlighted variety-specific patterns by comparing Cantonese, Italian, and Russian speakers across three generations in Toronto, Canada. For Cantonese and Italian, no significant difference in null subject use appeared between homeland-born (Gen1) and Toronto-born (Gen2 + 3) speakers. However, for Russian, Nagy identified two cross-generational changes:

1. a reordering of grammatical person hierarchy affecting null subject likelihood—from third- > second- > first-person in Gen1 to second- > first- > third-person in Gen2; and

2. negation emerging as a significant predictor for null subjects in Gen2 but not Gen1.

Unlike Otheguy et al. (Reference Otheguy, Zentella and Livert2007), these changes were unrelated to Russian usage frequency or English conditioning factors, suggesting internal cross-generational change independent of language contact (Nagy, Reference Nagy2015:320).

In the Vietnamese context, Tuc (Reference Tuc2003:121) noted that while kin terms generally convey solidarity and respect, pronouns like tao ‘I’ and mày ‘you’ can express either hostility or solidarity depending on the relationship between speakers. These relationships are shaped by social networks and structures, which tend to be less clearly defined in diaspora settings than in the homeland. Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2018) further highlighted this complexity by documenting consistent use of Vietnamese kin terms in code-switching discourse for self- and interlocutor-reference. Crucially, despite some nuanced differences in interpretation, both first- and second-generation speakers regard pronominal kin terms as markers of their “Vietnamese-ness,” using these forms to index their cultural identity. This underscores not only the pragmatic weight carried by Vietnamese pronominal forms but also the speakers’ metalinguistic awareness.

Data and method

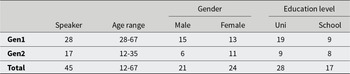

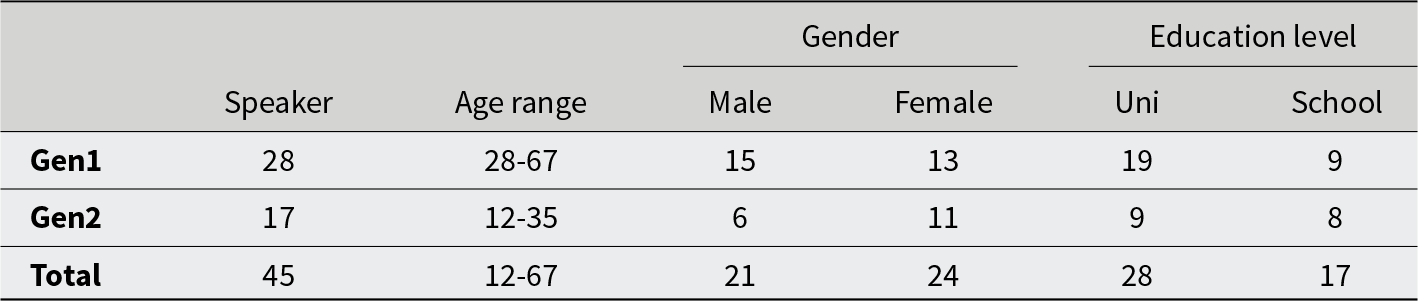

The data for this study come from the Canberra Vietnamese-English Corpus (CanVEC; Nguyen & Bryant, Reference Nguyen and Bryant2020), which contains natural speech from 45 Vietnamese-English bilingual speakers (21 men, 24 women) in Canberra, Australia, spanning two generations. First-generation speakers (Gen1) are the first in their families to emigrate, having lived in Vietnam until at least age 18 and residing continuously in Canberra for at least 10 years. Gen1 speakers in the sample range in age from 28 to 67, covering several waves of immigration: some are refugees who fled the Vietnam War, and some are recent economic migrants. Gen2 speakers are the children of Gen1 migrants and were either born in Australia or arrived before the age of five. The age limit for second-generation participants was to ensure early exposure to English-speaking communities before formal schooling and minimal time spent in Vietnam (cf. Hoffman & Walker, Reference Hoffman and Walker2010:44).Footnote 3 Table 1 summarizes the demographic make-up of CanVEC.

Table 1. CanVEC speakers’ demographic information

Data collection

The primary principle in collecting data for CanVEC was to capture vernacular speech with “minimum attention paid to speech” (Labov, Reference Labov, Baugh and Sherzer1984:29). Participants used their mobile phones to self-record a 30-minute conversation or two 15-minute conversations with Vietnamese-English bilinguals from their social networks. No instructions were given regarding language choice. Interlocutors were people the participants normally spoke to casually, such as friends, colleagues, or family members. This approach is a major strength of the corpus, as it maximizes the likelihood of natural language use—especially important given the complex pragmatics of subject expression. This results in 23 recordings in total, most of which are intergenerational conversations (n = 16, 70%); both Gen1 (n = 22, 96%) and Gen2 (n = 17, 73%) speakers are present in most recordings.

After submitting their recordings, participants completed a questionnaire designed to collect data on independent variables relevant to variation in their speech. This included self-rated proficiency in Vietnamese and English, as well as details about their social networks, language attitudes, and other factors. The recordings were then manually transcribed, anonymized, and semi-automatically annotated for language identification and part-of-speech tags (Nguyen & Bryant, Reference Nguyen and Bryant2020). The resulting corpus includes monolingual English, monolingual Vietnamese, and code-switched segments produced by the same speakers. This study focuses on the monolingual Vietnamese portion (n = 7508 clauses), where subject expression shows significant variation.

Extracting and coding for subject expression in Vietnamese

Identifying the variable context

Recall that Vietnamese pronominal forms are not a closed class but derive from kin terms, personal pronouns, or speakers’ names. Since all three categories are productively used for self-, interlocutor-, or third-party reference in the corpus, it is essential first to identify the relevant variable contexts.

Lexicalized set phrases with limited variability were excluded, such as thôi kệ ‘just ignore/leave it;’ nếu mà nói là ‘if I/you say that,’ n = 5; and common polite phrases like cảm ơn ‘thank you’ and xin lỗi ‘sorry.’ Nonhuman subjects, typically lexical NPs (n = 722, 12.5%), and cases where the subject was ambiguous in person, number, or coreferentiality (n = 24, 0.4%) were also excluded. In instances of subject repetition or repair (n = 45, 0.8%), only the final occurrence was counted.

Additionally, third-person singular nó can function as a neutral pronoun or a nonobligatory expletive. Since this study focuses on referential subjects, expletive uses of nó (e.g., Nó cứ thấy thế nào ấy ‘It feels a bit odd;’ n = 15, 0.3%) were excluded. Similarly, mình can refer to a nonspecific first-person plural (‘we’, similar to English generic ‘you;’ n = 15) or a specific first-person plural including speaker and interlocutor (n = 249). Only the specific mình instances were included.

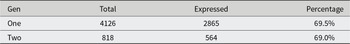

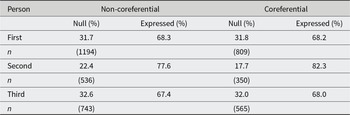

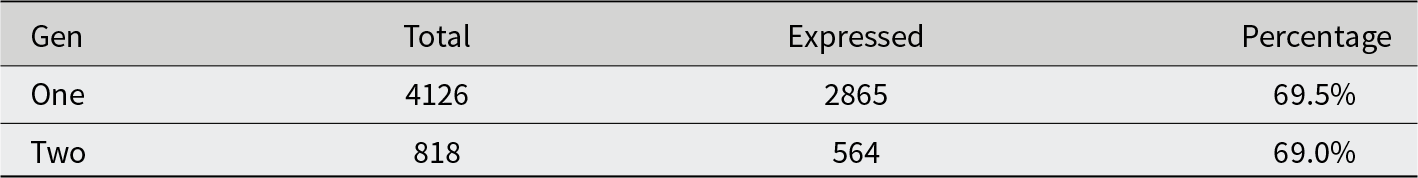

In total, 14.5% of the data (837 out of 5,781 clauses) were excluded based on these criteria. Table 2 presents an overview of the rate of null and expressed subjects by types in the final dataset.

Table 2. Cross-generational distribution of Vietnamese expressed subjects

As we can see, speakers produce expressed subjects nearly 70% of the time—a striking figure for a radical pro-drop language. We will revisit this finding in the Discussion. For now, the key point is that there is no significant difference in overall rates of expressed subjects between first- and second-generation speakers. However, as noted earlier, while the overall rates remain stable, the conditioning factors influencing subject expression may be changing. To investigate this, we turn to multivariate analyses that examine the combined effects of linguistic and extra-linguistic factors.

Coding linguistic factors

Person-Number: Grammatical person and number have consistently been presented as two of the strongest conditioning factors for subject expression. For instance, first-person is reportedly the most commonly expressed subject pronoun in Spanish (Bayley & Pease-Alvarez, Reference Bayley and Pease-Alvarez1997:363), European Portuguese (Barbosa et al., Reference Barbosa, Duarte and Kato2005:22), and Mandarin Chinese (Jia & Bayley, Reference Jia and Bayley2002:110), while second- and third-person are the most frequent overt pronouns in Russian (Nagy et al., Reference Nagy, Aghdasi, Denis and Motut2011:142), Brazilian Portuguese (Barbosa et al., Reference Barbosa, Duarte and Kato2005:22), and Santomean Portuguese (Bouchard, Reference Bouchard2018:17). In Vietnamese, however, we have previously seen that such norms vary with interlocutor and their associated status. The presence of these different discourse conventions means that, for grammatical person-number at least, instead of looking for absolute universals, we need to consider variety-specific patterns that are currently in play (Schroter, Reference Schroter2019:29).

Crucially, Vietnamese pronominal forms do not map neatly onto grammatical person-number. This is again largely due to the kinship-based system, where a single form can shift reference depending on the speaker and discourse context—for instance, the pronominal form con in Example (3) may refer to second-person singular when used by Tanner but first-person singular when used by Nina. Note that every CanVEC example presented features a transcript name (e.g., Tanner.Nina.0609) and a timestamp, with the subscript accompanying the speaker name indicating their generation membership (1 = Gen1, 2 = Gen2). English is given in regular print, while all non-English morphemes are given in italics.

The coding of person-number in Vietnamese thus relies entirely on the interpretation of each use within the wider discourse context. Thanks to the rich conversational data in the CanVEC corpus, this interpretation is straightforward. In this study, we code person and number as separate variables to isolate their individual effects.

Clause type: Cross-linguistic research also shows that clause type influences subject expression in many languages, including English (Harvie, Reference Harvie1998:21), Spanish (Torres Cacoullos & Travis, Reference Torres Cacoullos and Travis2018:91-94), Russian (Nagy et al., Reference Nagy, Aghdasi, Denis and Motut2011:142), and Chinese (Jia & Bayley, Reference Jia and Bayley2002:111; Li et al., Reference Li, Chen and Chen2012:112). In Cantonese, for example, main clauses tend to favor null subjects, whereas conjoined clauses tend to disfavor them (Nagy et al., Reference Nagy, Aghdasi, Denis and Motut2011:141). Given that Vietnamese falls into the same group of “radical pro-drop” as Cantonese, we might expect comparable patterns.

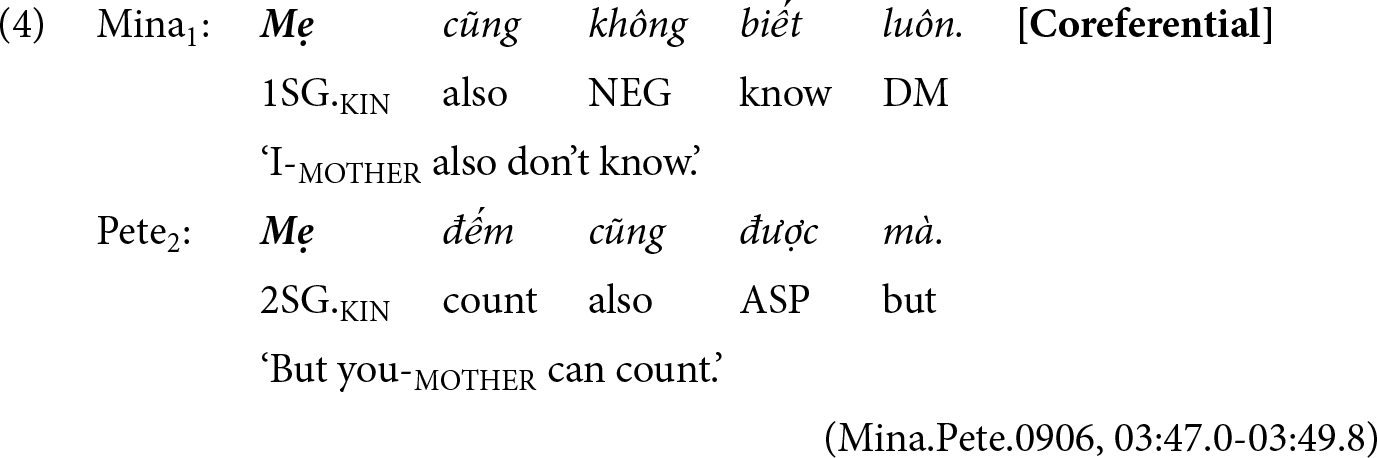

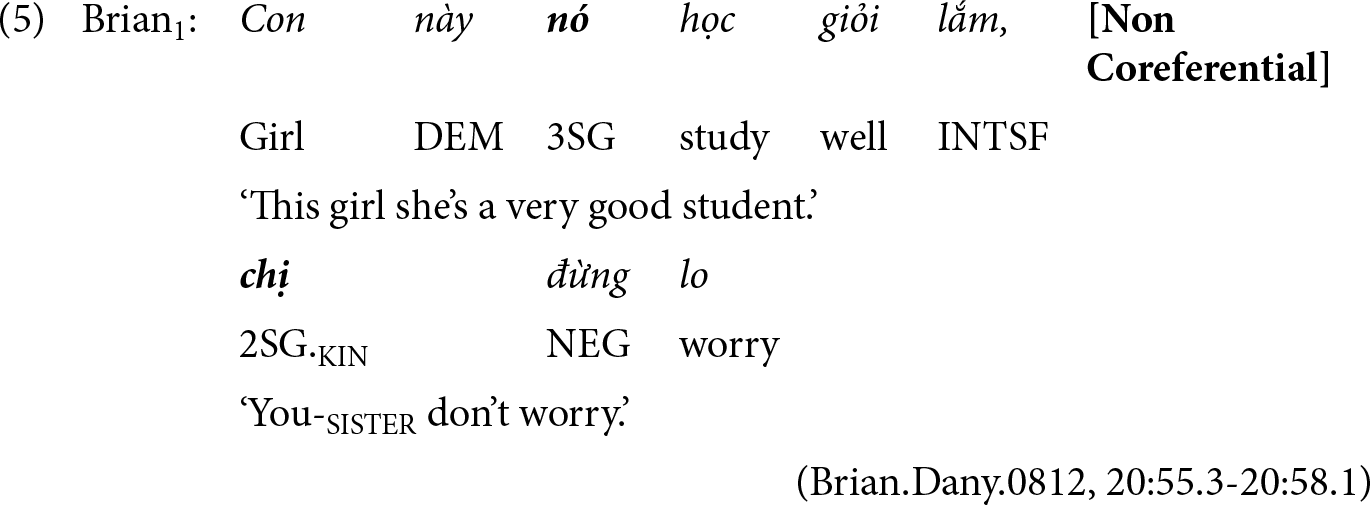

Coreferentiality: This concept relates to the well-established notion of referent accessibility. Since Givón’s (Reference Givón and Givón1983) work on topic continuity, numerous studies have shown that more accessible referents require less explicit coding—unexpressed forms represent the lowest coding effort and thus signal high accessibility. Here, accessibility is operationalized as coreferentiality, defined by whether the subject in the current clause shares the same referent as the subject in the preceding clause, regardless of the speakers. This approach reflects the discourse-dependent, co-constructed nature of reference. Examples (4) and (5) illustrate the same and switched referents, respectively.

Finally, cases of partial coreferentiality (e.g., we → I) were simply marked as if they were fully coreferential, mainly because these cases are extremely rare in the corpus (n = 5), and a separate treatment becomes too fine-grained.

Coding extra-linguistic factors

Data for extra-linguistic factors was extracted from the questionnaire responses containing speakers’ information on age, gender, primary language of the social network, self-assessed proficiency in each language, attitude toward each language, and speakers’ ethnic orientation—all of which have been shown to shape language variation (e.g., Kiesling, Reference Kiesling, Di Paolo and Yaeger-Dror2009; Labov, Reference Labov1972, Reference Labov, Baugh and Sherzer1984; Milroy & Milroy, Reference Milroy and Milroy1992).

Furthermore, given the honorific indexicality of Vietnamese pronominal forms, pragmatic constraints are likely to have an effect. Although it is not possible to conclusively define situational “respect” or “politeness,” the obvious factors here are the age gap between speakers and their respective social statuses. This pragmatic constraint was thus operationalized as “Interlocutor’s Age” and “Interlocutor’s Generation.” “Interlocutor’s Age” was coded as a binary factor: older/younger (in relation to the speaker themselves).Footnote 4

Statistical modeling

Generalized linear mixed-effects (GLMM) modeling was conducted using the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (version 4.2.1; R Core Team, 2022). Subject expression was treated as a binary response variable (null/dropped = 0, expressed = 1). The random effect structure was kept maximal for Speaker, as justified by the data. Categorical predictors were weighted effect-coded to account for the unbalanced sample sizes (Darlington & Hayes, Reference Darlington and Hayes2017:298-300; te Grotenhuis et al., Reference te Grotenhuis, Pelzer, Eisinga, Nieuwenhuis, Schmidt-Catran and König2017:163-166), while the only continuous predictor—speaker age—was z-standardized.

To identify significant predictors and to achieve a more parsimonious model, likelihood ratio tests were conducted by comparing the full model (with all predictors included) to separate restricted models, each excluding only one predictor at a time. Only predictors that significantly improved model fit—that is, those that contributed meaningfully to explaining the outcome based on model comparisons—were included in the best-fitting model. Interaction terms were further investigated using the emmeans package (Lenth, Reference Lenth2018). The fixed and random effects included in the models are described in the next section.

Multicollinearity was assessed by cross-tabulation, adjusted Generalized Variance Inflation Factor (GVIF), and inspection of regression diagnostics. Due to high collinearity with ethnic orientation, attitudinal and self-assessed proficiency variables for Vietnamese and English were removed. Given the cultural load of subject expression in Vietnamese, ethnic orientation was deemed a more relevant predictor.

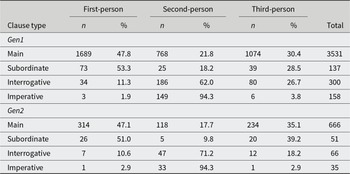

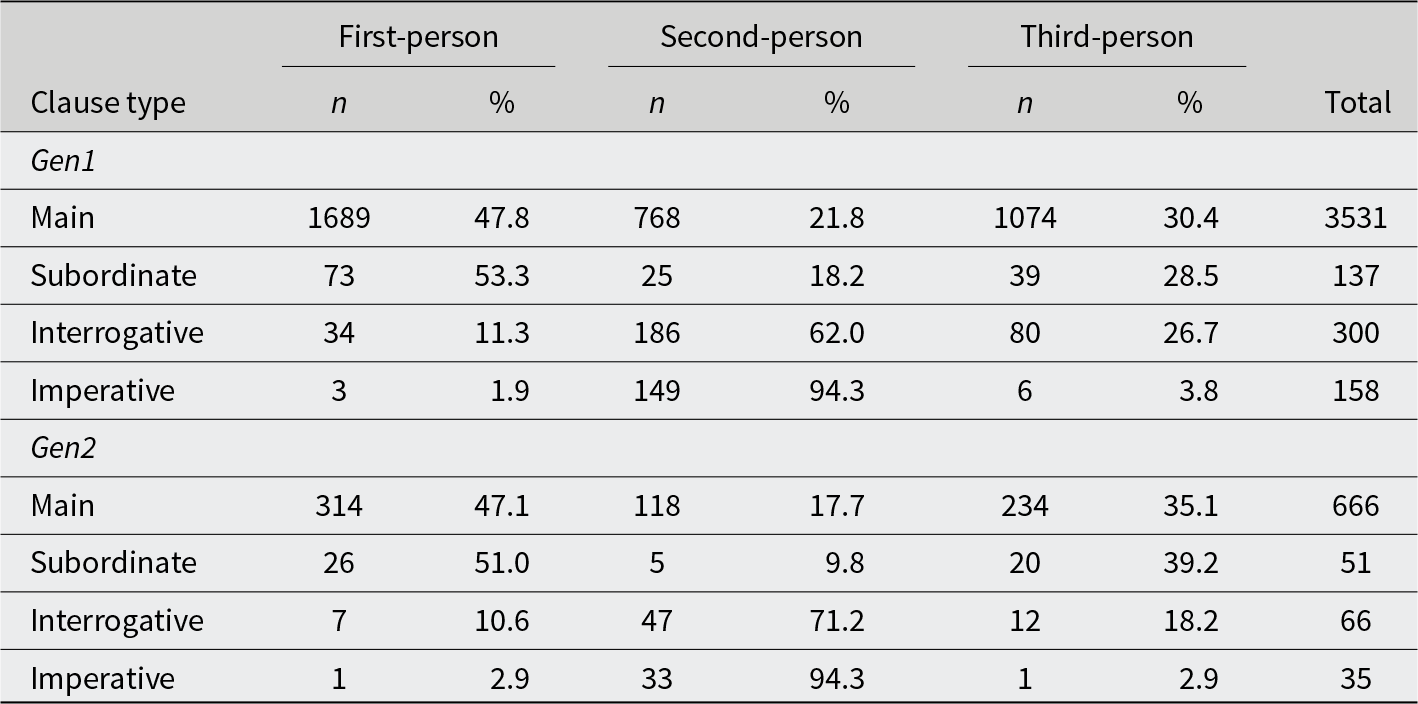

Finally, since clause type is expected to correlate to some degree with person (e.g., imperatives and interrogatives are more likely to occur with second-person subjects) and with Generation (e.g., more imperatives are likely to be produced by Gen1 speakers), we examine the distribution of these three factors in the dataset, as shown in Table 3. It is clear from the table that the counts for non-main clauses become relatively low when subdivided by person and generation. Including them in the analysis could introduce issues of non-orthogonality and confound interpretation. We thus proceeded with the analyses focusing on main clauses only.

Table 3. Distribution of Clause Type by Person and Generation (percentages reflect distribution by clause type)

Variable subject expression in the Canberra-Vietnamese community

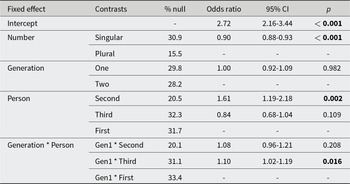

Focusing on main clauses only, regression analysis was next performed to ascertain whether there are generational differences in subject expression, controlling for the various linguistic and social factors as described. The list of fixed effects included in the maximal model can be found in Table 4. The random effect structure in the maximal and best-fitting models included a random intercept for Speaker and a by-speaker random slope for Person.

Table 4. Fixed effects included in the maximal generalized linear mixed-effect model, including number of observations per level of each categorical variable, contrast weights, and the justifications for the interaction terms

† Note: There were only five tokens of 2PL, which were therefore removed from the dataset. For this reason, an interaction term between Number and Person could not be included in the maximal model.

In the best-fitting GLMM model (n = 4197, conditional R 2 = 0.19), the main effects of Number (χ2(1) = 65.6, p < 0.0001) and the two-way interaction between Generation and Person (χ2(2) = 18.1, p < 0.0001) significantly improved model fit. The adjusted GVIF values for all fixed effects in the final model were below 1.02. As Table 5 illustrates, the main effects of Number and Person, and the two-way interaction between Generation and Person, were significant predictors. Compared to the weighted grand mean, null subjects were significantly more likely in singular subjects but less likely in second-person subjects.Footnote 5

Table 5. Summary of fixed effects from the best-fitting generalized linear mixed model with Subject expression as response (0 = null, 1 = expressed) and random intercept for Speaker

Note: Syntax of best-fitting model: glmer (Subject ∼ Number + Generation*Person + (1 + Person|Speaker)). Values in bold are statistically significant.

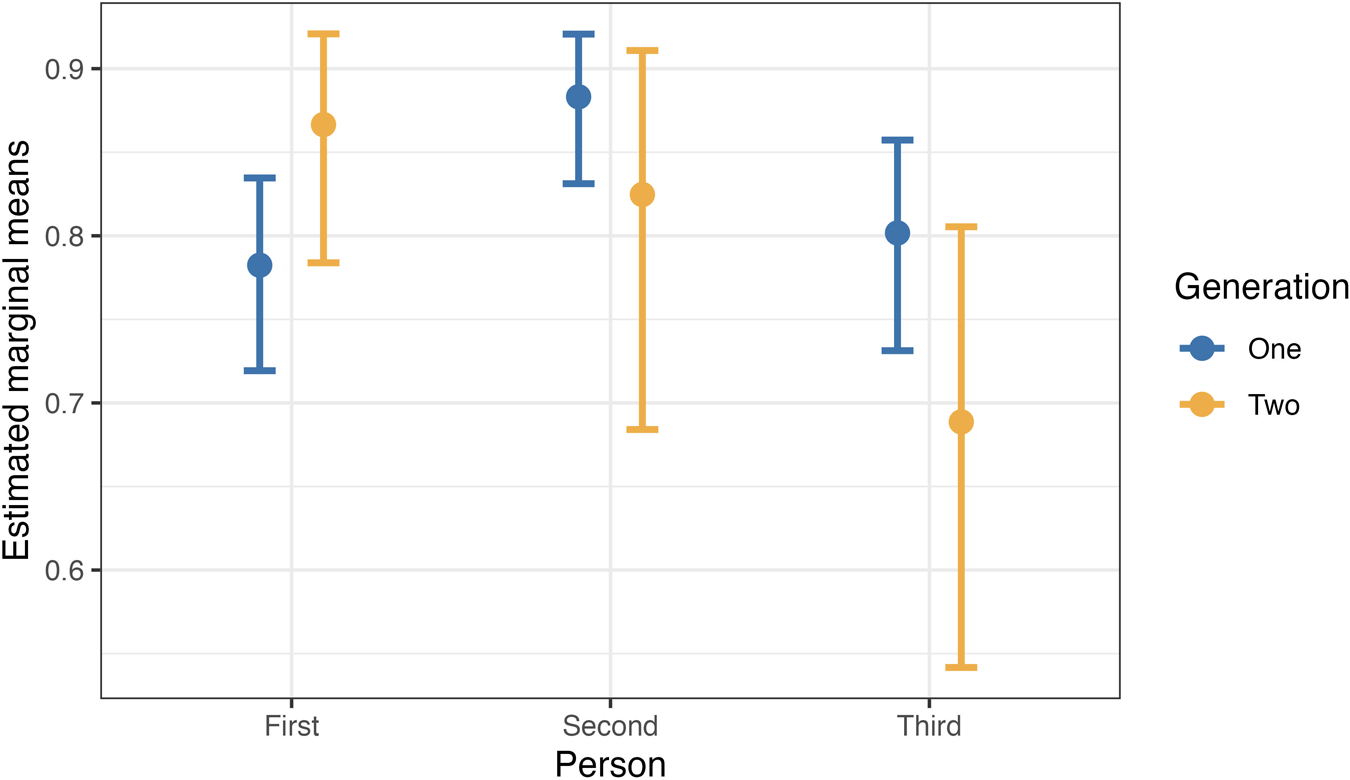

We then probed the interaction between Generation and Person. The plot of the marginal effects of this two-way interaction is presented in Figure 1. Pairwise comparisons within generations revealed that for Gen1 speakers, second-person subjects (% null = 20.1) were least likely to be null compared to first-person (% null = 33.4; OR = 2.10, SE = 0.49, z = 3.20, p = 0.004) and third-person subjects (% null = 31.1; OR = 1.87, SE = 0.46, z = 2.54, p = 0.03). Contrastingly, for Gen2 speakers, first-person subjects (% null = 22.6) were least likely to be null compared to third-person (% null = 38.0; OR = 0.34, SE = 0.12, z = -3.20, p = 0.004) and second-person subjects (% null = 23.7; OR = 0.73, SE = 0.33, z = -0.72, p = 0.75).

Figure 1. Marginal means of the interaction between Generation and Person for subject expression, with error bars representing 95% confidence intervals.

In summary, while there was no overall difference in the rate of unexpressed subjects, generational differences were observed in the conditioning factorsFootnote 6:

• Gen1 speakers were least likely to drop second-person subjects: first ≈ third > second; whereas

• Gen2 speakers were least likely to drop first-person subjects: third ≈ second> first

In other words, the hierarchy of the Person constraints has been reordered across generations when it comes to unexpressed subjects.

Discussion: subject expression in heritage Vietnamese

In much of the existing literature, a significant linguistic predictor—especially with reordered factor rankings—is often taken as evidence of cross-generational change in speakers’ grammar or competence (cf. Nagy et al., Reference Nagy, Aghdasi, Denis and Motut2011). However, in Vietnamese, subject expression carries culturally embedded meaning, making the notion of “grammatical change” less clear-cut. We therefore turn to the role of pragmatic norms in explaining the observed cross-generational variation in subject omission.

The peculiar direction of person effects: pragmatic shifts driving grammatical choices

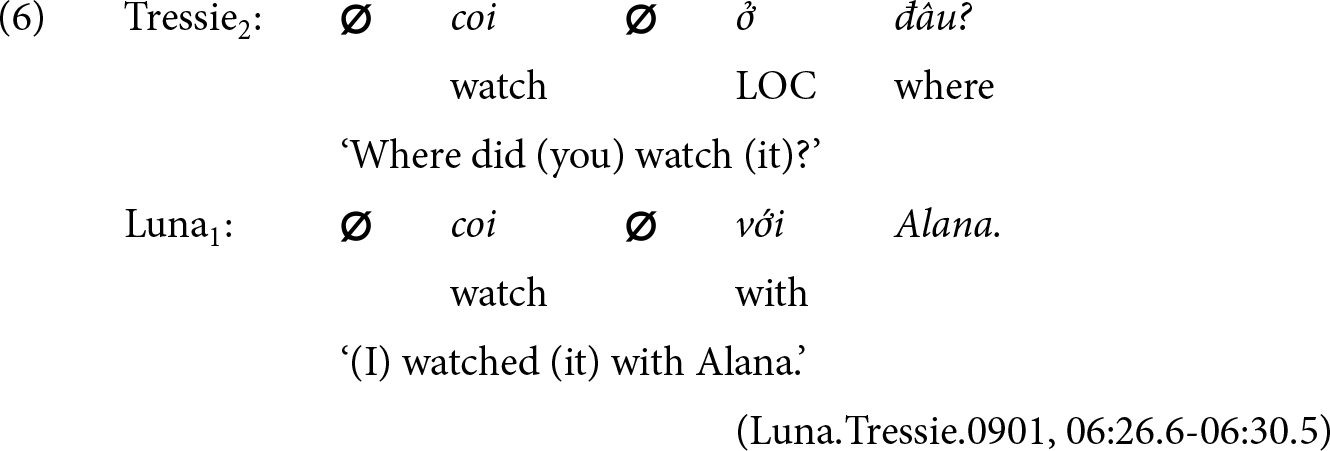

As our analyses revealed, while the likelihood of subject omission is similar across generations, the types of subjects omitted differ. Specifically, Gen1 speakers were most likely to drop first-person subjects, whereas Gen2 speakers were more likely to drop second-person subjects. This contrast is exemplified in Example (6).

This specific direction of effects runs counter to expectations. In fact, we anticipated that Gen2 speakers, due to age/status differences compared to Gen1, would be more likely to express second-person subjects. Our findings are thus particularly striking for second-person subjects.

To further probe this, we examine the patterning of different expressed forms across generations, as demonstrated in Table 6.

Table 6. Distribution of subject expression by Type, Person, and Generation

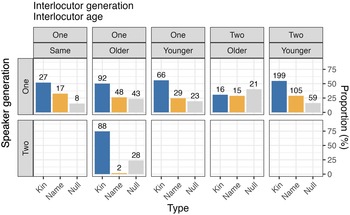

As shown, kin terms are widely used for all person subjects across both generations. For second-person subjects in particular, Gen2 speakers not only exhibit a higher rate of null subjects than Gen1 speakers (24% versus 20%), but also show a higher rate of kin term usage (75% versus 52%) and a much lower rate of personal names (2.0% versus 28%). This pattern suggests that the key pragmatic difference lies in the avoidance of personal names.

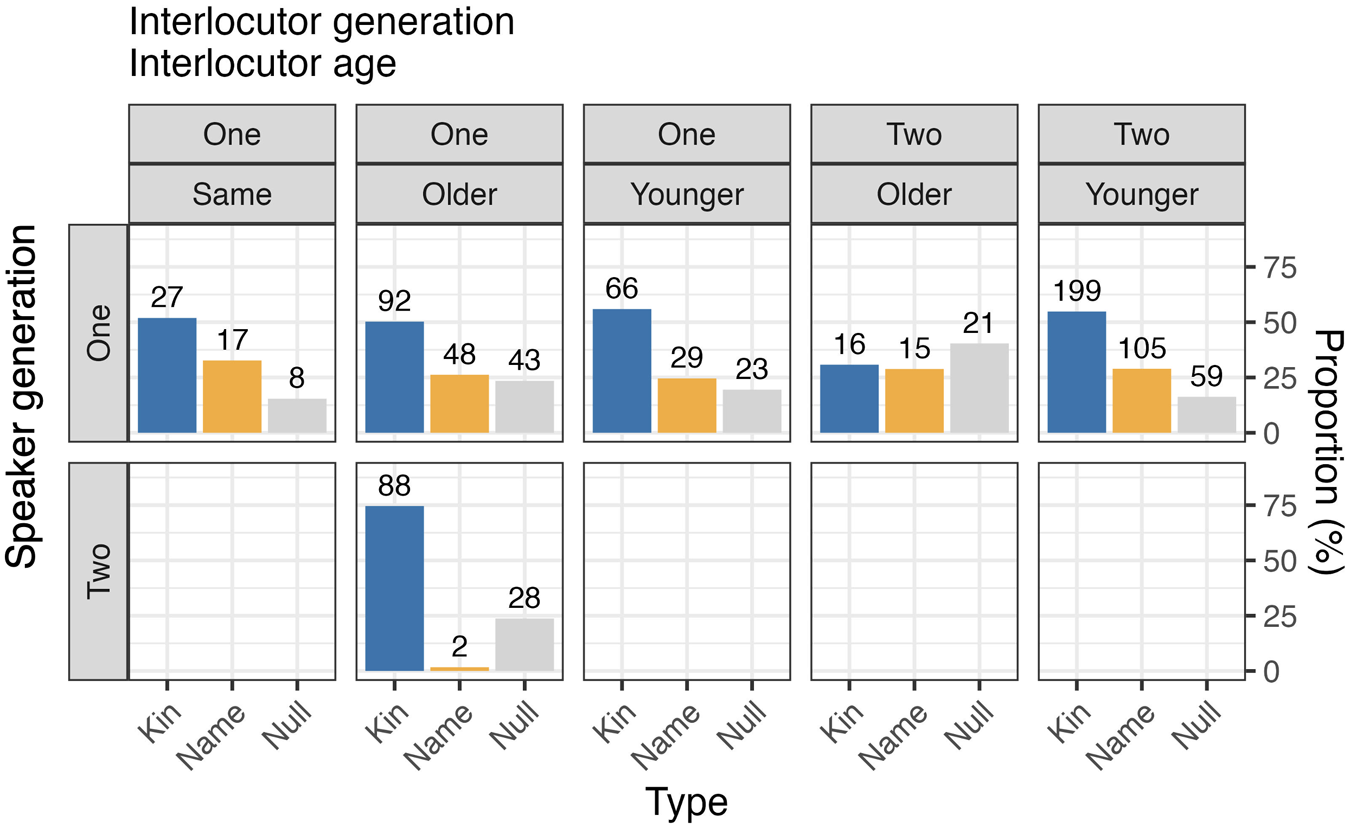

While this may align with expectations for younger speakers in family settings, it is important to note that we cannot conclusively determine whether the observed behavior is driven by age or by generational status. This is because all instances of second-person forms produced by Gen2 speakers in the corpus occur in conversations with Gen1 interlocutors who are also older, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Distribution of second-person subject types by Speaker’s Generation, Interlocutor’s Generation, and Interlocutor’s Age.

We can also observe from Figure 2 that, in contrast to the Gen2 pattern of avoiding personal names, Gen1 speakers show a clear tendency to express second-person subjects more frequently than not (i.e., null). Specifically, Gen1 speakers consistently use overt forms, even when addressing interlocutors who are younger, from a later generation, or both. This pattern may reflect a degree of cultural assimilation into Australian society. Given that most speakers in Canberra are highly educated, they have likely formed more diverse social networks through their jobs and education, providing exposure to broader communicative norms. These experiences may foster the development of distinct linguistic styles (cf. Le Page & Tabouret-Keller, Reference Le Page and Tabouret-Keller1985), or what Eckert (Reference Eckert, Chiang, Chun, Mahalingappa and Mehus2004:42) described as a community bricolage, where individuals draw on a range of resources to create new or reinterpreted meanings. In this context, the use of overt second-person subjects when addressing younger or later-generation speakers may serve to index an identity as “modern” Vietnamese—those who engage more equally with socially “lesser” interlocutors, thereby subtly distancing themselves from traditional homeland norms, shaped in part by past emotional experiences.

Such emotional distance could manifest in linguistic distance in various forms. Since Gen1 speakers also serve as linguistic input for Gen2 speakers, it follows that the pragmatic norms of explicitly expressing second-person subjects toward older interlocutors may not have been properly transmitted and acquired by the second generation. It is also probable that the bricolage was innovated by Gen2 speakers themselves, and by frequently dropping second-person subjects directed at older speakers, these younger speakers are trying to reject the Vietnamese social hierarchy entrenched in the language, thereby establishing a more equal relationship with the older generation.Footnote 7

Ultimately, it is important to emphasize that the reduced use of second-person pronominal subjects among Gen2 speakers cannot be explained by an increased reliance on alternative politeness strategies. As previously discussed, while politeness markers may reduce the need for an explicit first-person subject, they do not have the same effect on second-person subject drop. Moreover, such markers are relatively rare in our corpus (n = 55), and most appear in idiomatic expressions that were already excluded from the analysis. Taken together, these observations support the interpretation that the observed pattern of second-person subject drop is primarily driven by a shift in speakers’ pragmatic norms. This interpretation aligns with earlier research in Australia (e.g., Clyne, Reference Clyne2003:1-19), as well as with Sharma’s (Reference Sharma2011:484) study of second-generation British Asians, which found that this group’s linguistic practices across various contexts reflect a gradual but systematic move toward the norms of the dominant society.

Lack of Coreferentiality effects

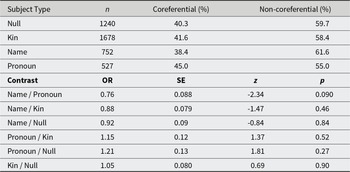

Another result that is worth commenting on is the lack of the Coreferentiality effect in conditioning subject drop in heritage Vietnamese. For avoidance of doubt, we present Tables 7 and 8. Table 7 shows the proportion of coreferential subjects across different subject types, along with pairwise comparisons from a logistic regression model in which Coreferentiality is the response variable (non-coreferential = 0, coreferential = 1) and Subject Type is the fixed effect. Table 8 displays the rates of subject expression in coreferential versus non-coreferential contexts, again restricted to main clauses to control for potential clause-type effects.

Table 7. Distribution of Coreferentiality (no/yes) by Subject Type (top) and pairwise comparisons of Subject Type predicting Coreferentiality (bottom)

Table 8. Distribution of Coreferentiality by Person in Vietnamese main clauses

As Table 7 demonstrates, there is no clear division of labor between null and expressed subjects across subject types, and no particular subject type appears significantly more sensitive to Coreferentiality as a conditioning factor. Likewise, Table 8 demonstrates that the rates of expressed and unexpressed subjects are remarkably similar, regardless of whether the context is coreferential or not. Taken together, these results suggest that the absence of a Coreferentiality effect is not due to collinearity or interactions with Subject Type. Rather, the absence of such an effect strongly appears to be genuine.

Although the absence of a Coreferentiality effect may seem to contradict cross-linguistic trends (e.g., Torres Cacoullos & Travis, 2018; Frascarelli, Reference Frascarelli, Cognola and Casalicchio2018; Jia & Bayley, Reference Jia and Bayley2002; Nagy et al., Reference Nagy, Aghdasi, Denis and Motut2011; Owens et al., Reference Owens, Dodsworth and Kohn2013), it aligns with Huang’s (Reference Huang1984) account of Mandarin Chinese, where null objects—not subjects—are more closely tied to discourse topics. In fact, later experimental works by Ngo (Reference Ngo2019) also found that Vietnamese speakers favor object reference in pronoun resolution, challenging the widely observed subject preference bias (cf. Chafe, Reference Chafe and Li1976). Ngo (Reference Ngo2019) also showed that both null and overt pronouns in Vietnamese are equally sensitive to grammatical role and structural parallelism—factors central to determining coreferentiality.Footnote 8 She further concluded that Vietnamese patterns more like Chinese than like Italian or Spanish, where a clearer division of labor in coreferential functions typically exists (Ngo, Reference Ngo2019:23). Given that variationist studies on subject expression have largely been dominated by languages of the latter type, it is perhaps unsurprising that coreferentiality plays a weaker role in the present work (see also Jia & Bayley, Reference Jia and Bayley2002:109 on Mandarin; Nagy et al., Reference Nagy, Aghdasi, Denis and Motut2011:210 on Cantonese).

Has Vietnamese co-evolved with speakers’ English?

Given that we have seen signs of evolution of Canberra Vietnamese unexpressed subjects across generations, an important question to ask is whether this has evolved in tandem with the speakers’ English. Although we do not have homeland data to confirm or refute contact effects (e.g., Torres Cacoullos & Travis, 2018; Nagy, Reference Nagy2015), comparing the patterns between those directly in contact still allows us to gauge the extent to which these languages interact and influence each other.

A close look at the English subset shows that the distribution of expressed subjects is near categorical. In fact, out of more than 2,500 English clauses, there were only 39 instances of unexpressed subjects (Gen1 = 25/1380; Gen2 = 14/1202). All of these are either 2SG within an imperative clause (Example 7) or within a conjoined clause with or without an overt conjunction (Examples 8 and 9, respectively).

Two conclusions can therefore be made:

1. pronominal subjects are almost always expressed in the speakers’ English; and

2. when an unexpressed subject occurs, it occurs in the expected environment.

This is in stark contrast with the pattern of unexpressed subjects in the speakers’ Vietnamese, both in terms of frequency and linguistic distribution. Further observations from the code-switching subset of the data also show that subject-drop grammars remain clearly separated within stretches of single-language use. Examples (10) and (11) provide some illustrations.

As we can see, across both generations, Vietnamese subjects are left null largely in Vietnamese stretches. In contrast, English subjects are consistently expressed in English segments. This separation is clear despite the close proximity of the two languages in discourse. The observation is thus consistent with Nagy’s (Reference Nagy2015) conclusions for heritage Cantonese, Italian, and Russian in Toronto, as well as Torres Cacoullos and Travis's (Reference Torres Cacoullos and Travis2018) work on New Mexican Spanish. The consensus is that the underlying grammar of subject expression in English and the substrate varieties remains separate, despite the highly bilingual nature of the communities and their sustained contact.

A note on overt subject expression

Before concluding, we would like to return to the observation in Table 2 about the distinction between null and overt forms in the corpus. Specifically, speakers’ preference for expressed forms over unexpressed forms is striking, accounting for at least 70% of all instances in the variable context. This counters the typical assumption of low rates of subject expression in “discourse pro-drop” languages. Although part of this high proportion of expressed subjects might be attributed to the “extended use” of overt forms in contact scenarios (e.g., Montrul, Reference Montrul2002 et seq.; Otheguy et al., Reference Otheguy, Zentella and Livert2007; Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2018 et seq.; Rothman, Reference Rothman2009; Silva-Corvalán, Reference Silva-Corvalán1994; Sorace & Filiaci, Reference Sorace and Filiaci2006 et seq.; Tsimpli et al., Reference Tsimpli, Sorace, Heycock and Filiaci2003; i.a.), let us not forget several pragmatic constraints that condition Vietnamese unexpressed subjects even in a monolingual variety. It is worth noting then that, to date, most of the existing work on pro-drop languages has only focused on discourse conditions (e.g., coreferentiality, ambiguity, distance from the previous mention, etc.; see Frascarelli, Reference Frascarelli, Cognola and Casalicchio2018; Nagy et al., Reference Nagy, Aghdasi, Denis and Motut2011; Owens et al., Reference Owens, Dodsworth and Kohn2013; i.a.) rather than pragmatic factors that regulate the expression of subjects. This highlights a gap in our understanding of Vietnamese-type pro-drop languages, where established discourse factors such as coreferentiality play less of a role (cf. Ngo, Reference Ngo2019), but pragmatic factors such as politeness, age, and perceived social status are considered more important (cf. Song & Nguyen, Reference Song and Nguyen2022; Song et al., Reference Song, Nguyen, Biberauer and Patterson2023).

More broadly, our findings here also corroborate those of Torres Cacoullos and Travis (Reference Torres Cacoullos and Travis2018), who previously showed how Polish and European Portuguese (both null-subject languages) are closer to Japanese and Korean (both considered “discourse pro-drop” languages), respectively, in terms of subject expression rates, than they are to each other. The expression (or lack thereof) of subjects in the so-called “radical pro-drop” languages is thus perhaps not so radical after all. This invites further typological inquiry into subject expression, especially in light of recent quantitative studies that have challenged such traditional typologies (cf. Torres Cacoullos & Travis, Reference Torres Cacoullos and Travis2019). The findings also highlight the importance of understanding social context in developing theoretical work.

Conclusion

In this paper, we investigated subject expression across generations in the Vietnamese community living in Canberra, Australia. Cross-generational effects were detected in relation to Person as a conditioning factor: while unexpressed subjects were most favored with first-person subjects for Gen1 speakers, they were most favored with second-person subjects for the Gen2 speakers. Given that Gen2 speakers are socially obliged to overtly realize forms referring to their older interlocutors (which is the case for all but one Gen2 in the corpus), this specific direction of effects runs counter to expectations.

Given the community background and the consistent patterns observed across the corpus, we interpret this finding as a possible reflection of the speakers’ cultural integration into Australian society—more specifically, a form of community bricolage to promote more egalitarian relationships between generations in the diaspora. Although it remains to be seen whether the observed “change” reflects a temporary shift in community norms or a lasting development in the heritage language, the consistent patterns found suggest that this behavior has taken hold within the community. Ultimately, the findings reported here present a case where pragmatic norms can, in fact, drive grammatical changes in a language-contact situation.

Linguistically, we offer two key findings. First, the overwhelmingly high rate of expressed subjects across both generations in this work calls into question the classification of Vietnamese as a “radical” pro-drop language. Second, we find that coreferentiality is not a significant predictor of null subject use in Vietnamese, challenging a widely observed cross-linguistic trend in this area of research. We account for these results by drawing on prior theoretical and experimental work on Vietnamese and Mandarin Chinese as a typologically similar language.

On a broader scale, we emphasize the importance of studying under-described heritage languages and the communities where they are spoken. Heritage language is still an emerging field, and as Polinsky and Scontras (Reference Polinsky and Scontras2020:13) noted, “we have barely scraped the surface” of its rich empirical landscape. The lack of data from a diverse source of communities and language varieties has only exacerbated this problem (Stanford, Reference Stanford2016:528). It is our hope that this study—which explored a lesser-documented heritage language like Vietnamese within an atypical community such as Canberra—represented a step toward addressing this gap.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback.

Competing interest declarations

The author(s) declare none.