Non-technical Summary

Tupinambines, commonly referred to as tegus, are a group of large-bodied lizards that evolved and diversified in South America, where they have a rich fossil record spanning the Eocene through Pleistocene. This article introduces a new genus and species that represents the only fossil evidence of a tupinambine in North America and the most northerly record of the subfamily in the Neogene. The appearance of this species on what was then the southern coastline of North America coincided with the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum. At the time, global temperatures were at some of the warmest experienced in the past 34 million years, suggesting that a warm climate was favorable for northern expansion of these large hyperthermic lizards. Living tegus are commonly kept as pets, which has led to a growing number of introduced populations in the southeastern United States (primarily Florida); this report highlights a brief time when tupinambines were part of the southeastern landscape before human introduction.

Introduction

Tupinambinae Bonaparte, Reference Bonaparte1831 is a group of mid- to large-bodied lizards endemic to South America today (Pianka and Vitt, Reference Pianka and Vitt2003; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Ugueto and Gutberlet2012; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Garcia and Zaher2016). Living species are included in the genera Callopistes, Crocodilurus (crocodile lizards), Dracaena (caiman lizards), Salvator, and Tupinambis (tegus) (Pianka and Vitt, Reference Pianka and Vitt2003). They are well represented in the Cenozoic fossil record of South America from the Eocene to Pleistocene (see Appendix 1 for records and citations) and are reported to have had a more widespread distribution in the late Mesozoic to Paleogene, with records from the Cretaceous of North America and Eocene of southwestern France (Estes Reference Estes1964, Reference Estes1969; Denton and O’Neill, Reference Denton and O’Neill1995; Sullivan and Estes, Reference Sullivan, Estes, Kay, Madden, Cifelli and Flynn1997; Augé and Brizuela, Reference Augé and Brizuela2020). Purported North American Cretaceous records are based on fragmentary cranio-dental material from Alberta, Montana, New Mexico, and Wyoming and have been contested as alternatively belonging to the extinct teiid subfamily Chamopsiinae (Denton and O’Neill, Reference Denton and O’Neill1995). Denton and O’Neill (Reference Denton and O’Neill1995) provided support that the two living teiid subfamilies, Tupinambinae and Teiinae, are South American in origin and were never present in the Cretaceous of North America. If Tupinambinae or Chamopsiinae sensu Denton and O’Neill (Reference Denton and O’Neill1995) were present at all in the Cretaceous, they likely went extinct in North America by the end of the Maastrichtian (Sullivan and Estes, Reference Sullivan, Estes, Kay, Madden, Cifelli and Flynn1997). Here we present the first fossil record of a tupinambine in the Cenozoic of North America and the oldest unequivocal record of the subfamily on the continent.

Geologic setting

Locality information

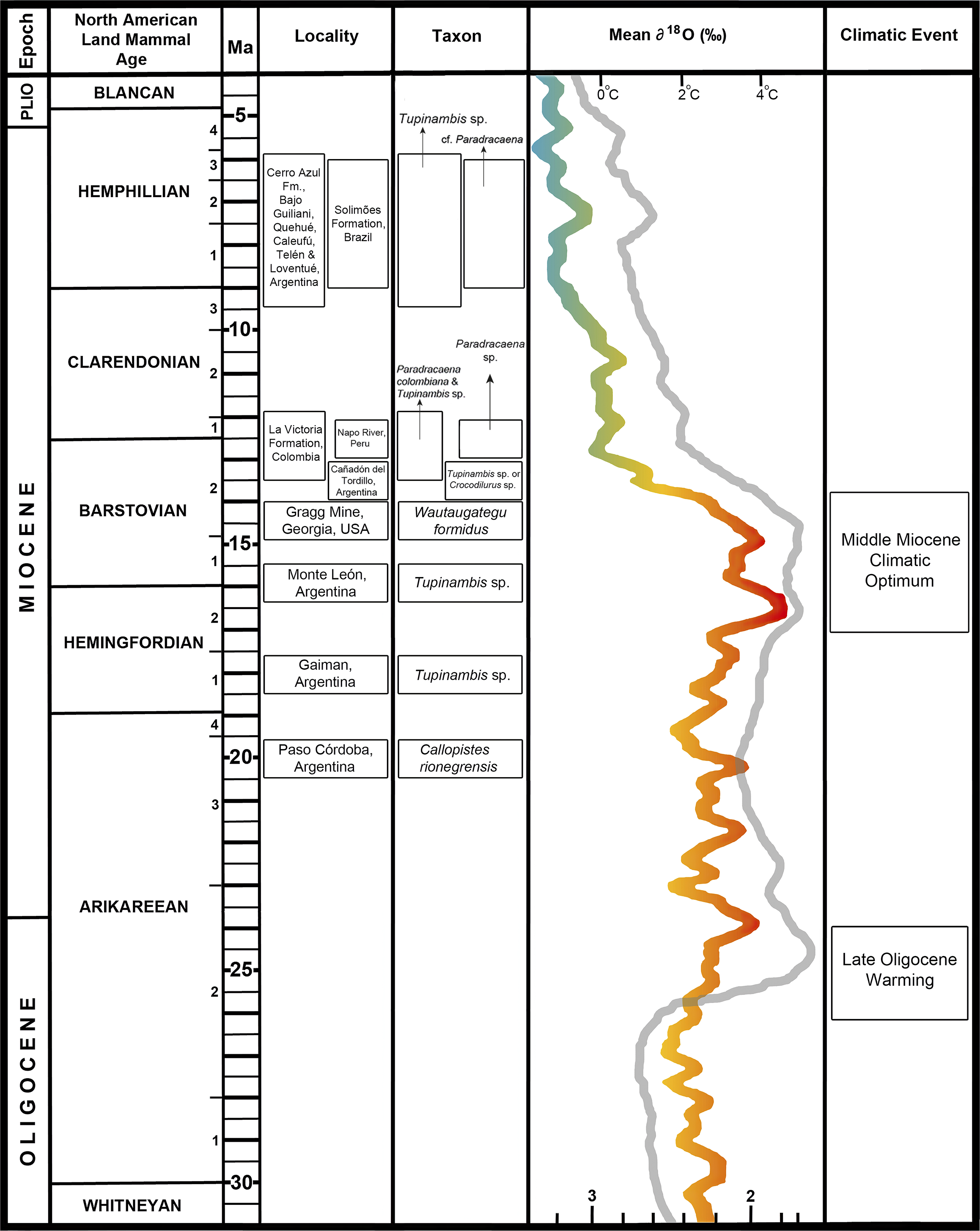

Gragg Mine is a now-defunct fuller’s earth clay mine located about 5.6 km southeast of Attapulgus in Decatur County, Georgia, just north of the border with Florida, geographic datum WGS84, 30.72°N, 84.44°W (Fig. 1). At present, it is completely reforested with little or no exposure of the fossil-bearing deposit (Bourque et al., Reference Bourque, Stanley and Hulbert2023) and may have been reburied with overburden soils in the reclamation process (R. Hulbert, personal communication, 2023). Fossils from this locality are largely unpublished, but a diverse middle Miocene (Barstovian 2, 14.8–14.0 Ma) local fauna is represented by micro- and to a lesser extent macrofossils. The age of the fauna was determined biochronologically using its diverse mammalian micro- and macrofauna and co-occurrence of the rare large-bodied salamander Batrachosauroides sp. (Bourque et al., Reference Bourque, Stanley and Hulbert2023). It is one of the few deposits in the Gulf Coastal Plain of this age, approximately coeval with the Cold Spring Fauna of Texas and Fort Polk Fauna of Louisiana (Bourque et al., Reference Bourque, Stanley and Hulbert2023) (Fig. 1). Marine and freshwater fish are the most abundant non-mammalian constituents of the Gragg Mine paleofauna, but frogs, salamanders, chelonians, snakes, lizards, a small alligator, and birds are also represented (Mörs and Hulbert, Reference Mörs and Hulbert2010; Bourque et al., Reference Bourque, Stanley and Hulbert2023). Salamanders include batrachosauroidids, salamandrids, and a small Amphiuma species, possibly of the Amphiuma pholeter Neill, Reference Neill1964 lineage (Bourque et al., Reference Bourque, Stanley and Hulbert2023). Turtles are represented by trionychids, kinosternids, emydids (deirochelyines), and testudinids (Bourque et al., Reference Bourque, Stanley and Hulbert2023). Snakes are the most common squamates in the fauna and require further study. Lizards are comparatively rarer, represented by partial jaws and other cranial fragments, osteoderms, and relatively few vertebrae, and include anguids, iguanids, scincids, and at least two teiids, a Teiinae (small-bodied taxon) and a Tupinambinae (mid- to large-bodied taxon described here). The paleoenvironment is similar to that hypothesized for the nearby Willacoochee Creek Fauna (Bryant, Reference Bryant1991) and likely represents a coastal fluvial deposit with an admixture of marine, freshwater, and terrestrial vertebrates. Fossil deposits in this region of the southeastern United States reflect a transient coastline in the middle Miocene, farther north than today (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, MacFadden and Mueller1992). Dated at 14.8–14.0 Ma, the Gragg Mine site is regionally significant for the southeastern United States in that it represents a terrestrial coastal plain environment at the conclusion of one of the warmest periods of the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum (MMCO), when sea level was close to its highest in the Neogene (Zachos et al., Reference Zachos, Pagani, Sloan, Thomas and Billups2001; Westerhold et al., Reference Westerhold, Marwan, Drury, Liebrand and Agnini2020). At that time, Florida was largely submerged with the exception of some small islands along the Brooksville Ridge and a complex of islands and peninsulas along the border with Georgia and Alabama (Randazzo and Jones, Reference Randazzo and Jones1997).

Figure 1. Elevation map of the southeastern United States. Contour line at 60 m above current sea level represents a hypothetical paleocoastline during the late stage of the MMCO, based on sea-level-rise estimates if the Antarctic ice sheet were largely depleted (Zachos et al., Reference Zachos, Pagani, Sloan, Thomas and Billups2001; Farinotti et al., Reference Farinotti, Huss, Fürst, Landmann, Machguth, Maussion and Pandit2019; Morlighem et al., Reference Morlighem, Rignot, Binder, Blankenship and Drews2019). The paleocoastal Gragg Mine (red dot) is the only locality where a single fossil tupinambine vertebra (UF:VP: 546657) was collected. The Gragg Mine and similarly aged Cold Spring and Fort Polk faunas (yellow dots in Texas and Louisiana, respectively) are rare in the southeastern United States in preserving terrestrial faunas from the late MMCO. Map generated in part with elevation data from www.worldclim.org.

Materials and methods

To minimize intracolumnar differences in vertebral morphology when making systematic comparisons, we estimated the vertebral position of UF:VP: 546657 using a geometric morphometric analysis of presacral vertebral shape change in extant tupinambines. This was performed on a comparative dataset containing the fossil and representative species from all six extant tupinambine genera. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) scanning was performed on UF:VP: 546657 on the UF Nanoscale Research Facility’s Phoenix V|tome|X M dual tube CT system. The vertebra was scanned in a cotton-filled polyethylene tube to reduce movement and unnecessary X-ray attenuation, then scanned using Datos|X A software (Waygate Technologies, Skaneateles, NY, USA) under the following conditions: voxel resolution = 9.25846 μm; Xray tube voltage = 80 kV; current = 120 μA; detector capture time = 0.333096 seconds per image, averaging three images per capture. Radiographs were converted to tomograms using Datos|X R (Waygate Technologies, Skaneateles, NY, USA), using the edge enhancement, ROI filter, and inline median modules. Comparative CT datasets of modern tupinambine genera have been produced as part of the oVert Thematic Collections Network (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, Boyer, Gray, Winchester and Bates2024) and were downloaded from Morphosource.org. For each dataset, all presacral vertebrae (excluding the atlas and axis) were individually segmented, visualized, and converted to .ply polygon file format using VGStudioMax 2023.4 (Volume Graphics, Heidelberg Germany). Twenty-five three-dimensional (3D) landmarks were placed at homologous points of the fossil and each modern tupinambine trunk vertebra using the ALPACA single-template landmark transfer batch function in the SlicerMorph module of 3D Slicer (Porto et al., Reference Porto, Rolfe and Maga2021). All auto-placed landmarks were checked by eye and adjusted where necessary. Landmarks for two asymmetrically damaged vertebrae were recorded by mirroring the shape file and superimposing it back on to the original model. Landmark data were transformed to remove size, orientation, and positional variation using the Generalized Procrustes Analysis function in SlicerMorph, and a principal component analysis was performed on the Procrustes residuals. The first two principal components and centroid size for each vertebra were plotted in R. Tomogram stacks and stereolithography mesh files are available to download from www.Morphosource.org (see Appendix 2 for DOI links).

Specimens examined

Fossils: Tupinambinae (Gragg Mine): UF:VP: 546657; Ctenosaura (Cucaracha Formation, Panama): UF:VP: 262294. Extant: Callopistes flavipunctatus (Duméril and Bibron, Reference Duméril and Bibron1839): UF:Herp: 76336, UF:Herp: 81964; Callopistes maculatus Gravenhorst, Reference Gravenhorst1838: UMMZ:Herp: 118093; Crocodilurus amazonicus Spix, Reference Spix1825: KU:KUH: 127240; Dracaena guianensis Daudin, Reference Daudin1801: UF:Herp: 57890, UF:Herp: 129938; Neusticrurus bicarinatus (Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758): UF:Herp: 55784; Salvator merianae Duméril and Bibron, Reference Duméril and Bibron1839: UF:Herp: 150437; UF:Herp: 189770; Tupinambis teguixin (Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758): LSUMZ:Herp: 47686; UF:Herp: 51999, UF:Herp: 57012. Numerous other teiids housed in the UF:Herp: collection were utilized for comparison during this study, including a representative teiine Ameiva ameiva (Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758) UF:Herp: 137671. Specimens listed using Darwin Core Triplet identifier scheme.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Types, figured, and other specimens examined in this study are deposited in the following institutions: Division of Herpetology, Louisiana Museum of Natural History, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge (LSUMZ: Herp:); Division of Herpetology, KU Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum, University of Kansas, Lawrence (KU:KUH:); Division of Vertebrate Paleontology, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville (UF:VP:); Division of Herpetology, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville (UF:Herp:); Division of Herpetology, Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (UMMZ:Herp:).

Systematic paleontology

Order Squamata Oppel, Reference Oppel1811

Family Teiidae Gray, Reference Gray1827

Subfamily Tupinambinae Bonaparte, Reference Bonaparte1831

Genus Wautaugategu new genus

Type species

Wautaugategu formidus n. gen. n. sp.

Diagnosis

As for type species by monotypy.

Occurrence

As for type species.

Etymology

Combination of Wautauga in reference to the Wautauga State Forest, a local landmark near the type locality, and tegu, the colloquial name for T. teguixin and Salvator spp.

Remarks

As for type species.

Wautaugategu formidus new species

Figure 2. Holotype thoracic vertebra of Wautaugategu formidus n. gen. n. sp., UF:VP: 546657, from the Gragg Mine, Georgia, in (1) anterior, (2) posterior, (3) dorsal, (4) ventral, (5) left lateral, and (6) right lateral aspects.

Figure 3. Comparison of the fossil Wautaugategu formidus n. gen. n. sp. with thoracic vertebrae (T6) of extant teiid taxa. Rows of specimen images represent the following: (1) Wautaugategu formidus (UF:VP: 546657); (2) Callopistes maculatus (UMMZ:Herp: 118093); (3) Crocodilurus amazonicus (KU:KUH: 127240); (4) Salvator merianae (UF: Herp: 150437); (5) Dracaena guianensis (UF:Herp: 129938); (6) Tupinambis teguixin (LSUMZ: Herp: 47686); (7) Ameiva ameiva (UF:Herp: 137671). Aspects from left to right: left lateral, anterior, right lateral, posterior, dorsal, and ventral. Scale bars = 2 mm.

Holotype

UF:VP: 546657, complete thoracic vertebra from the T4–T6 region.

Diagnosis

Recognized as a tupinambine in being a mid- to large-bodied teioid vertebra with a thickened well-developed zygosphene and corresponding zygantrum, both with developed articulating facets and a strong interlocking system. In addition, it resembles other large tupinambine vertebrae in being dorsoventrally compressed, broad and relatively flat ventrally, and widest anteriorly at the laterally protruding diapophyses and having a broad ovoid cotyle and condyle.

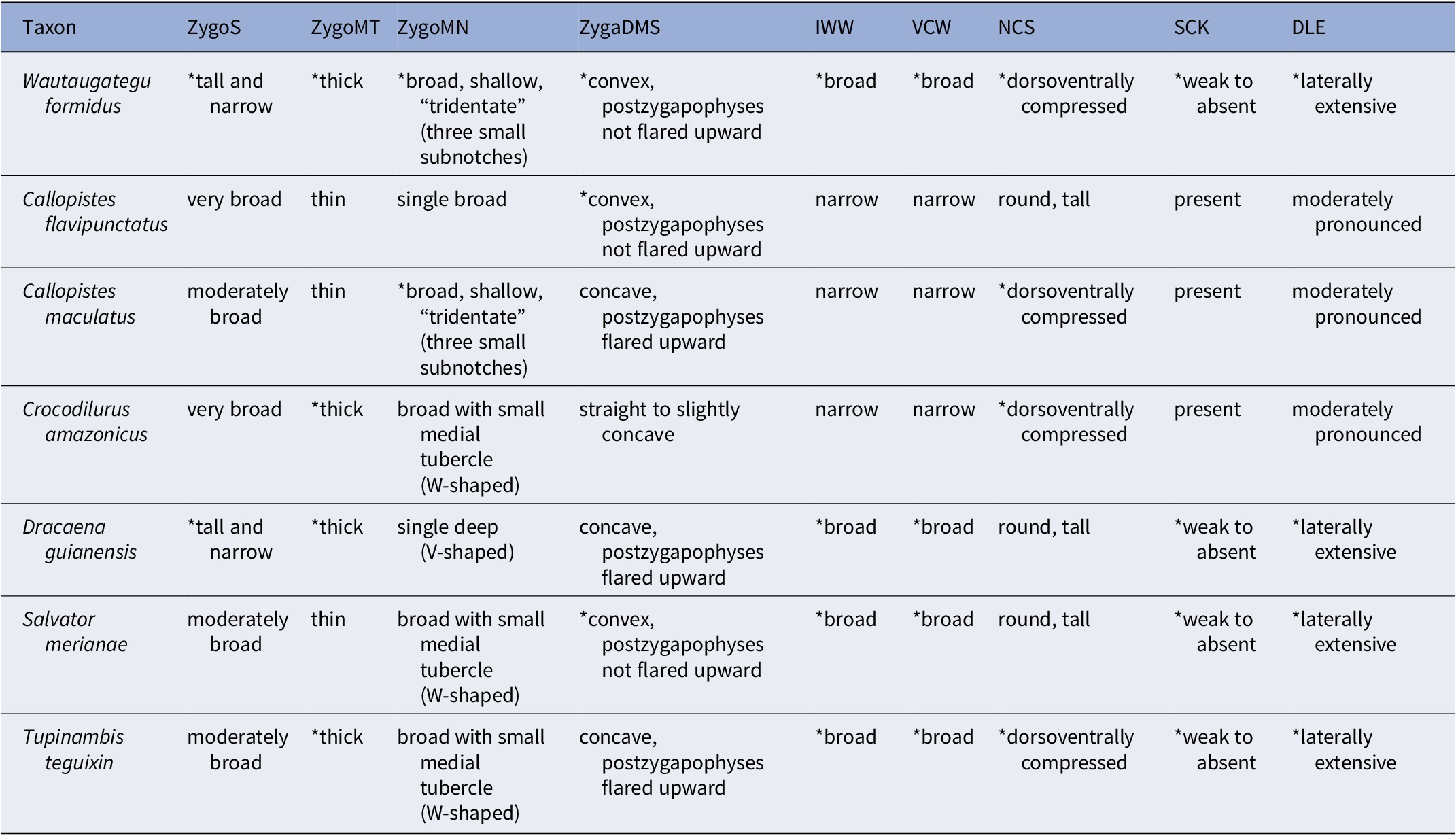

It is diagnosed as a new genus and species by the unique combination of the following characters in the T4–T6 series: zygosphene laterally compressed (shared with Ca. maculatus and D. guianensis), robustly built (shared with Cr. amazonicus, D. guianensis, and T. teguixin), and with articular facets oriented at an angle greater than 45° (shared with D. guianensis); zygosphene with a broad and shallow medial notch composed of three minute subnotches in dorsal aspect (shared with C. maculatus) and greatly thickened bone at the midline (shared with Cr. amazonicus, D. guianensis, and T. teguixin); dorsolateral margin of the zygantrum tall and convex (shared with Callopistes flavipunctatus and S. merianae); diapophyses laterally extensive (shared with D. guianensis, T. teguixin, and S. merianae); interzygapophyseal waist width and centrum broad in dorsoventral aspect (shared with D. guianensis, T. teguixin, and S. merianae); lack of a distinct subcentral keel (shared with D. guianensis, T. teguixin, and S. merianae). In addition, the prezygapophyses uniquely have broad rounded to slightly ovoid articular facets in UF:VP: 546657, but there is some wear around the prezygapophyseal margins, so it is unclear whether this feature is actual or based on preservation.

Occurrence

Gragg Mine, Decatur County, southwestern Georgia, USA; middle Miocene, Barstovian 2 NALMA, 14.8–14.0 Ma (Bourque et al., Reference Bourque, Stanley and Hulbert2023).

Description

UF:VP: 546657 is identified as a mid-body thoracic vertebra in having tall diapophyses that extend from the base of the prezygapophyses almost to the ventral margin of the cotyle and protrude laterally. The degree of ventral extent of the diapophyses varies throughout the vertebral column in tupinambines and seems to be most pronounced where the longest ribs occur on the body at the posterior limits of the rib cage. Compared with the thoracic vertebrae of extant tupinambines, this morphotype is typically situated in the range of T4–T6 (Fig. 4). Thoracic vertebrae are identified here as having extensive ribs that articulate with the sternum. The vertebra UF:VP: 546657 is relatively complete but with some minor abrasion along all edges, including the zygosphene, zygapophyses, and cotyle. The neural spine is missing, but a small basal portion is preserved anteriorly. Measurements are as follows: 9.46 mm long between the pre- and postzygapophyses, 10.82 mm wide at diapophyses, 8.85 mm wide at prezygapophyses, 8.25 mm wide at postzygapophyses, and 6.6 mm tall at the zygosphene.

Figure 4. Shape analysis of comparative tupinambine specimens. (1) CT dataset of Salvator merianae UF:Herp: 150437 with presacral vertebrae segmented. (2) Anterior view of presacral vertebrae in (1). (3) Morphospace plots of the first two principal components of 3D geometric morphometric analysis of vertebrae for five extant tupinambine species. Point color denotes vertebral position (corresponding to (1) and (2)); point diameter denotes centroid size for the individual vertebrae. The black diamonds denote the morphometric position of the Gragg Mine fossil UF:VP: 546657. (4) The first principal component score from the geometric morphometric analysis plotted against vertebral number (beginning at cervical 3) for modern tupinambines. The black diamonds bracket the potential vertebral position of UF:VP: 546657 based on the first principal component. C = cervical; L = lumbar; T = thoracic.

The zygosphene is unique among tupinambines in being tall, narrow, thick medially, and well ossified. In this way, it most closely resembles Dracaena, but the medial notch is deep and V-shaped and there are elongate horn-like processes on the dorsolateral margins of the articular facets in the latter that are lacking in the fossil. The zygantrum is also well developed, with distinct articular facets to interlock with the zygosphene. The dorsolateral zygantrum margins are tall to accommodate the tall zygosphene. The cotyle and condyle are broadly ovoid. The articular face of the former is directed downward and the latter upward. The cotyle and condyle are slightly rounder in Dracaena than in the fossil. The neural canal is wide in being dorsolaterally compressed, and spade to heart-shaped in anterior and posterior aspects. There is a pair of minute dorsomedial foramina on either side of the neural spine. The ventral centrum is relatively broad and smooth and lacks hypapophyses. A very subtle broad subcentral (or hemal) ridge of low relief is present, accompanied by a pair of minute subcentral foramina on either side.

Etymology

Latin formidus for ‘warm’ in reference to the hypothesized climate during the MMCO and favored body temperature of teiids.

Remarks

As stated in the diagnosis, the vertebra UF:VP: 546657 compares favorably to those of extant tupinambines but differs from described species for which vertebrae are known in possessing a unique combination of character states (Table 1). It strongly resembles D. guianensis in having a tall, narrow zygosphene, Ca. maculatus in possessing a zygosphene with a broad, shallow, tridentate medial notch, and S. merianae and Ca. flavipunctatus in having a convex (versus concave) dorsolateral zygantrum margin with non-flared postzygapophyses. This contrasts with a concave margin, which makes the postzygapophyses appear flared (e.g., in Ca. maculatus, Cr. amazonicus, D. guianensis). Despite unique morphological similarities with species of Dracaena and Salvator, UF:VP: 546657 is smaller than full-grown adults of these genera. The neural canal is relatively compressed dorsoventrally in anterior view, as in Cr. amazonicus, Ca. maculatus, and T. teguixin. Proportionally, UF:VP: 546657 is stout in being transversely broad at the interzygapophyseal waist, which among extant tupinambines is shared only with Dracaena and the living tegus Tupinambis and Salvator. UF:VP: 546657 is dissimilar from extant North American teiine teiids as well as the gymnophthalmid Neusticrurus bicarinatus in its much larger size and in some of the following characters: the Cnemidophorus/Aspidoscelis group and Ameiva spp. have a weakly developed zygosphene–zygantrum system and the zygosphene and zygantrum are much broader than in tupinambines; Ame. ameiva possesses a medial tubercle on the anterior margin of the zygosphene, a subcentral (hemal) keel, and a tall distinct ridge in lateral aspect that extends from the diapophysis just below the prezygapophysis to the ventrolateral margin of the condyle.

Table 1. Distribution of selected vertebral characters for some tupinambines. States with an asterisk (*) are shared with UF:VP: 546657. ZygoS = zygosphene shape; ZygoMT = zygosphene medial thickness; ZygoMN = zygosphene medial notch; ZygaDMS = zygantrum dorsolateral margin shape; IWW = interzygapophyseal waist width; VCW = vertebral centrum width; NCS = neural canal shape; SCK = subcentral keel; DLE = diapophyseal lateral extent.

Results

Morphometric analysis

The 3D geometric morphometric analysis incorporated 116 vertebrae (UF:VP: 546657, Ca. maculatus = 24, Cr. amazonicus = 23, D. guianensis = 23, S. merianae = 23, and T. teguixin = 23). The first two principal components explain 55.5% of the variation in the dataset, with PC1 (49.43%) representing the rostrocaudal elongation and PC2 (14.1%) the lateral expansion of the pre- and postzygapophyses. When the first two principal components are plotted, each specimen shows a stereotyped progression through morphospace along the vertebral column (Fig. 4), with the post-axial cervical vertebrae anteroposteriorly compressed and laterally expanded, becoming gradually elongated and narrower posteriorly, with the posteriormost presacral vertebrae becoming less elongate again. The Gragg Mine fossil UF:VP: 546657 groups closely with the thoracic vertebrae, and particularly those of D. guianensis and S. merianae. Among all tupinambines, it compares favorably to thoracic vertebrae in the range of T4–T6. The conclusion regarding the vertebral position was reached by traditional qualitative comparisons at the onset of this study and further corroborated later by the quantitative method presented here.

Discussion

UF:VP: 546657 is the only known tupinambine fossil from the Cenozoic of North America. Following Denton and O’Neill (Reference Denton and O’Neill1995), who reclassified purported tupinambines from the Cretaceous of North America as chamopsiines, it is the only unequivocal tupinambine fossil from North America. Today, tupinambine diversity is centered in South America, which not surprisingly boasts the richest fossil record of these lizards, with numerous accounts from the early Eocene to Pleistocene (Appendix 1).

The timing of tupinambine dispersal into North America is here confirmed to have taken place by the middle Miocene (Fig. 5), but likely earlier. An increasing number of fossils from the early Miocene Las Cascadas and Cucaracha formations of the Panama Canal indicate that some reptiles and at least one mammal moved from South to North America before the complete formation of the Panamanian Isthmus. Examples include the monkey Panamacebus transitus Bloch et al., Reference Bloch, Woodruff, Wood, Rincon and Harrington2016, Boa constrictor Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758 (Head et al., Reference Head, Rincon, Suarez, Montes and Jaramillo2012), caimans (Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Bloch, Jaramillo, Rincon and MacFadden2013), podocnemidid side-necked turtles (Cadena et al., Reference Cadena, Bourque, Rincon, Bloch, Jaramillo and MacFadden2012; Bourque, Reference Bourque2016, Reference Bourque2022), and the large-bodied iguanid lizard Ctenosaura (J.R. Bourque, personal observation, Reference Bourque, Stanley and Hulbert2023; UF:VP: 262294). All the pre-isthmus dispersing reptiles share an aptitude for locomotion in water and likely traversed the inter-American seaway by some combination of swimming, rafting, and/or island hopping. Extant tupinambines frequent water bodies and are agile in water, and some such as D. guianensis and Cr. amazonicus are partly aquatic (Mesquita et al., Reference Mesquita, Colli, Costa, França, Garda and Péres2006). Bourque (Reference Bourque2016) discussed how small to mid-sized podocnemidids from the middle Miocene of the Florida Panhandle (from ancient coastal plain deposits very near the border with Georgia) strongly resemble similar-sized podocnemidids from the early Miocene Cucaracha Formation of Panama. These turtles likely made their way north to the southeastern United States when mean annual temperatures were more favorable during the MMCO megathermal. A similar pattern of dispersal from South to North America by the early Miocene, coupled with a brief colonization of the southeastern United States during the MMCO, may have been the case for the tupinambine discovered at the Gragg Mine. Yet no fossils from Central or North America older than those from the Gragg Mine have yet been discovered to confirm this hypothesis or the timing of dispersal. Similarly, there are no pre-MMCO fossil tupinambines known from the Caribbean, and only a single amphibian, the frog Eleutherodactylus, has been demonstrated to have dispersed to North America (Florida) via the Antillean route by the late Oligocene (Vallejo-Pareja et al., Reference Vallejo-Pareja, Stanley, Bloch and Blackburn2023). A tupinambine record from the Eocene of France provides evidence that these lizards dispersed from South America to Europe, with Africa as the most likely route (Augé and Brizuela, Reference Augé and Brizuela2020). The dispersal hypothesis of Augé and Brizuela (Reference Augé and Brizuela2020) seems valid but their referred vertebra is dissimilar from those of all South American crown-tupinambines and from Wautaugategu formidus in lacking a well-developed interlocking zygosphene–zygantrum system. Therefore, it likely represents an earlier dispersal of a stem tupinambine from South America.

Figure 5. Correlation timeline comparing early to late Miocene South and North American localities having fossil tupinambines with global temperature shifts (Zachos et al., Reference Zachos, Pagani, Sloan, Thomas and Billups2001; Tedford et al., Reference Tedford, Albright, Barnosky, Ferrusquia-Villafranca, Hunt, Storer, Swisher, Voorhies, Webb, Whistler and Woodburne2004; Westerhold et al., Reference Westerhold, Marwan, Drury, Liebrand and Agnini2020). Mean ∂18O curves after Westerhold et al. (Reference Westerhold, Marwan, Drury, Liebrand and Agnini2020) (color gradient) and Zachos et al. (Reference Zachos, Pagani, Sloan, Thomas and Billups2001) (gray). All previous tupinambine records from the interval shown are from South America and suggest that the group dispersed into North America from South America. This is further supported in that the oldest tupinambine fossils (Lumbrerasaurus scagliai Donadío, Reference Donadío1985) are from the early Eocene of Argentina (Brizuela and Albino, Reference Brizuela and Albino2015). The tupinambine from the Gragg Mine is the only record from North America and occurs at the conclusion of the MMCO megathermal. Previously published tupinambine records are from the following (bottom to top): Paso Córdoba (Quadros et al., Reference Quadros, Chafrat and Zaher2018); Gaiman (Brizuela and Albino, Reference Brizuela and Albino2004); Monte León (Donadío, Reference Donadío1984b; Albino et al., Reference Albino, Brizuela and Montalvo2006); Cañadón del Tordillo (Brizuela and Albino, Reference Brizuela and Albino2008); Napo River (Pujos et al., Reference Pujos, Albino, Baby and Guyot2009); La Victoria Formation (Sullivan and Estes, Reference Sullivan, Estes, Kay, Madden, Cifelli and Flynn1997); Cerro Azul Formation (Albino et al., Reference Albino, Montalvo and Brizuela2013); Bajo Guiliani, Quehué, Caleufú, Telén, and Loventué (Albino et al., Reference Albino, Brizuela and Montalvo2006); Solimões Formation (Hsiou et al., Reference Hsiou, Albin and Ferigolo2009; age sensu Kay Cozzuol, Reference Kay and Cozzuol2006).

Tupinambine physiology and warm climate

Modern teiids have the highest preferred and field body temperature, highest critical thermal maximum, and one of the highest critical thermal minima of all living lizards (Clusella-Trullas and Chown, Reference Clusella-Trullas and Chown2014), and some taxa such as the tupinambine Cr. amazonicus are even highly active during the hottest part of the day in the tropics (Mesquita et al., Reference Mesquita, Colli, Costa, França, Garda and Péres2006). Tupinambines such as D. guianensis and Cr. amazonicus require warm tropical temperatures year-round to thrive, particularly given their association with water (Mesquita et al., Reference Mesquita, Colli, Costa, França, Garda and Péres2006). Notably, the Gragg Mine tupinambine record is at the conclusion of the MMCO, during one of the warmest intervals of the Cenozoic and the warmest part of the Neogene (Zachos et al., Reference Zachos, Pagani, Sloan, Thomas and Billups2001; Westerhold et al., Reference Westerhold, Marwan, Drury, Liebrand and Agnini2020). Their occupation in the southeastern United States was likely tied to this megathermal and likewise very brief, as no other similar fossils have been found in North America before or after the MMCO. Having been collected from a paleowetland deposit, it is unclear whether Wautaugategu formidus favored aquatic habitats like D. guianensis and Cr. amazonicus and consistently required warm aquatic conditions. Localities of similar age to Gragg Mine are scarce, but perhaps other late Barstovian or middle Miocene Gulf Coastal Plain sites will yield more records from a time when the coastline reached southern Georgia and possibly parts of northernmost Florida (Bryant, Reference Bryant1991; Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, MacFadden and Mueller1992). A tupinambine record from the Eocene (~37.8 Ma) of France during the Greenhouse World represents a similar disjunct high-latitude record of a teiid during a globally warm interval followed by a seemingly rapid disappearance in the region likely due to global cooling in the Oligocene (Augé and Brizuela, Reference Augé and Brizuela2020). In an account about the oldest Tupinambis from the early Miocene Sarmiento Formation of Patagonia, Argentina, Brizuela and Albino (Reference Brizuela and Albino2004) noted that the record “indicates warmer more humid conditions than in the region today.” Albino (Reference Albino2011) discussed how climate change influenced tupinambine populations in the Miocene of South America when they reached as far south as possible, stating that “the uplift of the Patagonian Andes, followed by a decrease in temperature and an increase in desertification, induced a strong contraction in the distribution of tupinambine teiids to northern regions of Patagonia and even forced the complete disappearance of boids from this region.”

Living tegus possess several attributes and behaviors that predispose them to be successful invaders, and their wide native ranges in South America support this aptitude for dispersal (Jamevich et al., Reference Jamevich, Hayes, Fitzgerald, Yackel Adams, Falk, Collier, Bonewell, Klug, Naretto and Reed2018). Tupinambines have been anthropogenically reintroduced to North America relatively recently (ca. late 1900s to early 2000s) and are quickly expanding their range into the subtropical portions of the southeastern United States. S. merianae and T. teguixin are established in some areas, primarily in southern Florida (Krysko et al., Reference Krysko, Enge and Moler2019), and there is evidence of an established population of S. merianae as far north as southeastern Georgia (Haro et al., Reference Haro, McBrayer, Jensen, Gillis, Bonewell and Nafus2020). While they seem to thrive in warmer coastal regions of Florida, they can withstand mildly cold winters in more northern latitudes of the southeastern United States by burrowing and entering dormancy. Their ability to live in subtropical regions in the southeastern United States today somewhat contradicts the argument for megathermal paleotemperatures driving dispersal into the southeastern United States during the middle Miocene. However, previous and ongoing studies seek to better understand long-term survivability of tupinambines in the southeast. The tegus S. merianae and T. teguixin have very expansive native ranges in South America, which include regions with relatively cold winters (Jamevich et al., Reference Jamevich, Hayes, Fitzgerald, Yackel Adams, Falk, Collier, Bonewell, Klug, Naretto and Reed2018). A study of outdoor captive S. merianae in Auburn, Alabama, demonstrated that range expansion of this taxon may not be as limited by weather and climate as one might predict (Krysko et al., Reference Krysko, Enge and Moler2019; Goetz et al., Reference Goetz, Steen, Miller, Guyer, Kottwitz, Roberts, Blankenship, Pearson, Warner and Reed2021), and distribution modeling based on their native ranges suggests that suitable habitats for these lizards are available over much of the southern United States and northern Mexico (Jamevich et al., Reference Jamevich, Hayes, Fitzgerald, Yackel Adams, Falk, Collier, Bonewell, Klug, Naretto and Reed2018). A study on S. merianae suggested that these lizards are capable of metabolic thermogenesis, even at relatively small body size (~2 kg) in the absence of external environmental heat sources (Tattersall, et al., Reference Tattersall, Leite, Sanders, Cadena, Andrade, Abe and Milsom2016), and another study similarly showed that hibernating wild S. merianae were able to maintain thermal stability with body temperatures above those of available thermal microhabitats in the Florida Everglades (Currylow et al., Reference Currylow, Collier, Hanslowe, Falk, Cade, Moy, Grajal-Puche, Ridgley, Reed and Yackel Adams2021).

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Hulbert, R. Narducci, J. Bloch, B. MacFadden, D. Blackburn, and C. Sheehey (FLMNH) for collections assistance and discussions; D.P. Mihalik for donations and discovering the Gragg Mine fossil site and J. Hoffman, R. Hulbert, A. Poyer, and A. Zimmerman, all of whom collected at the short-lived Gragg Mine fossil deposit; L.V. Lopez, M. Riegler, S. Zbinden, K. Marks, and M.C. Vallejo-Pareja for discussions; and J. Head and G. Georgalis for helpful manuscript comments. This is University of Florida Contribution to Paleobiology 889.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Appendix 1. List of tumpinambine and purported tupinambine records referenced in this study

Appendix 2. CT data for specimens used in this study