1. Introduction

Many natural cellular materials possess outstanding properties such as light weight, high stiffness and improved heat control (e.g. Al-Ketan, Rowshan & Al-Rub Reference Al-Ketan, Rowshan and Al-Rub2018), and are therefore inspiring the creation of new engineering materials with similar advantageous traits (e.g. Femmer, Kuehne & Wessling Reference Femmer, Kuehne and Wessling2015; Pouya et al. Reference Pouya, Overvelde, Kolle, Aizenberg, Bertoldi, Weaver and Vukusic2016). When translating this to engineering applications, a key question arises: How can we mimic natural cells and replicate the structures observed in nature? Earlier simple geometries in two dimensions such as, triangles or hexagons (Gibson Reference Gibson2003), as well as three-dimensional (3-D) polyhedral cells including hollow octahedron truss and octet lattice (e.g. Han, Lee & Kang Reference Han, Lee and Kang2015; Zheng et al. Reference Zheng2016) had the drawback of sharp edges and corners, leading to stress concentration in structural applications. Moreover, such designs are not conducive to cell migration and attachment, particularly in tissue engineering applications. To overcome these limitations, triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS)-based media (a class of metamaterial) have garnered serious attention over the past decade. Triply periodic minimal surfaces comprise minimal surface areas where the mean curvature is zero at every point (e.g. Do Carmo Reference Do Carmo2016), resulting in smooth surfaces, lacking sharp edges or corners that can be repeated without intersecting in three dimensions, and examples include Schoen gyroid, Schwarz primitive, and Schwarz diamond (e.g. Al-Ketan & Abu Al-Rub Reference Al-Ketan and Abu Al-Rub2019). Some of the TPMS geometries that we will focus in this paper are shown in figure 1 (details of which will be presented later).

Figure 1. The TPMS porous media used in this study with solid phase shown in the shading. Panels (a), (b) and (c) represent one unit cell in 12 mm

![]() $\times$

12 mm

$\times$

12 mm

![]() $\times$

12 mm of gyroid, primitive and BCC, respectively. The pair (

$\times$

12 mm of gyroid, primitive and BCC, respectively. The pair (

![]() $d_{\!p1}, d_{\!p2}$

) in mm for

$d_{\!p1}, d_{\!p2}$

) in mm for

![]() $\phi =$

0.85, 0.7 and 0.55 are, respectively, the following: gyroid, (2.34, 5.35), (1.72, 4.72) and (1.07, 4.07); primitive, (4.9, 10.5), (3.78, 9.74), (2.38, 9.02); BCC, (8.0, 11.4), (6.88, 9.78), (5.82, 8.28). Panels (d), (e) and ( f) show

$\phi =$

0.85, 0.7 and 0.55 are, respectively, the following: gyroid, (2.34, 5.35), (1.72, 4.72) and (1.07, 4.07); primitive, (4.9, 10.5), (3.78, 9.74), (2.38, 9.02); BCC, (8.0, 11.4), (6.88, 9.78), (5.82, 8.28). Panels (d), (e) and ( f) show

![]() $4\times 4$

unit cells of gyroid, primitive and BCC, respectively.

$4\times 4$

unit cells of gyroid, primitive and BCC, respectively.

With the advancement of additive manufacturing technology (e.g. 3-D printing), these complex geometries can be manufactured with high precision (Velasco-Hogan, Xu & Meyers Reference Velasco-Hogan, Xu and Meyers2018) that prompted numerous studies on the mechanical properties of various TPMS porous media demonstrating the superiority of TPMS over traditional lattice structures (e.g. Jung & Buehler Reference Jung and Buehler2018; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Mertens, Ferrucci, Yan, Shi and Yang2019). Consequently, the primary focus on TPMS porous media has been their mechanical properties, with relatively less attention devoted to the fluid flow aspects (or thermal properties, e.g. Samson, Tran & Marzocca (Reference Samson, Tran and Marzocca2023)) within TPMS porous media, which provides the motivation of this study to focus on the fluid dynamics perspective. Most available research emphasises biomedical and heat-transfer applications with a need for pressure drop evaluation to estimate permeability. Here we will present a comprehensive set of TPMS pressure drop measurements for varying parameters overcoming some of the existing experimental limitations. A salient feature of this paper is the introduction of a more accurate permeability estimation methodology compared with the usually accepted procedure, which also allows one to place different porous media (and not merely TPMS) on a single plot for comparison with drag coefficient as a function of Reynolds number. As such, we will present the estimation methodology of an ‘equivalent hydraulic diameter’ (called

![]() $d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

), not from the geometry of the porous media, but rather by an inverse method directly from the experimental pressure drop data.

$d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

), not from the geometry of the porous media, but rather by an inverse method directly from the experimental pressure drop data.

1.1. Permeability estimates in TPMS porous media

Classically, average pressure change

![]() $\Delta\! P$

over a distance

$\Delta\! P$

over a distance

![]() $\Delta x$

is given by the Darcy–Forchheimer relation (e.g. Bear Reference Bear1988; Regulski et al. Reference Regulski2015),

$\Delta x$

is given by the Darcy–Forchheimer relation (e.g. Bear Reference Bear1988; Regulski et al. Reference Regulski2015),

where,

![]() $u_s$

is the ‘superficial velocity’ defined as the volumetric flow rate divided by the cross-sectional area that includes multiple pore (or units cells), whereas the ‘intrinsic velocity’ (at the pore level)

$u_s$

is the ‘superficial velocity’ defined as the volumetric flow rate divided by the cross-sectional area that includes multiple pore (or units cells), whereas the ‘intrinsic velocity’ (at the pore level)

![]() $u_i = u_s/\phi$

, where porosity

$u_i = u_s/\phi$

, where porosity

![]() $\phi =V_\textit{fluid}/V_\textit{total}$

is the ratio of fluid to total volume;

$\phi =V_\textit{fluid}/V_\textit{total}$

is the ratio of fluid to total volume;

![]() $\mu$

and

$\mu$

and

![]() $\rho$

are, respectively, the dynamic viscosity and density of the fluid, and the two-dimensional coefficients

$\rho$

are, respectively, the dynamic viscosity and density of the fluid, and the two-dimensional coefficients

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

(

$K_{\!Q1}$

(

![]() $\textrm {m}^2$

) and

$\textrm {m}^2$

) and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

(

$K_{\!Q2}$

(

![]() $\textrm {m}$

) are the, quadratically fitted (hence, the subscript

$\textrm {m}$

) are the, quadratically fitted (hence, the subscript

![]() $Q$

), viscous (Darcy) and inertial (Forchheimer) permeabilities, respectively. Without the quadratic term in (1.1), we obtain Darcy’s formula that is valid within the laminar (low velocity) regime with dominant viscous forces. As fluid velocity increases, pressure drop is no longer linear and deviates from Darcy’s law, requiring the

$Q$

), viscous (Darcy) and inertial (Forchheimer) permeabilities, respectively. Without the quadratic term in (1.1), we obtain Darcy’s formula that is valid within the laminar (low velocity) regime with dominant viscous forces. As fluid velocity increases, pressure drop is no longer linear and deviates from Darcy’s law, requiring the

![]() $u_s^2$

term to account for the turbulent flow regime, i.e. the Forchheimer addition. Although not explicit in (1.1), it is clear that

$u_s^2$

term to account for the turbulent flow regime, i.e. the Forchheimer addition. Although not explicit in (1.1), it is clear that

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

are functions of

$K_{\!Q2}$

are functions of

![]() $\phi$

as well as the pore geometry.

$\phi$

as well as the pore geometry.

Most permeability estimations (e.g. Bobbert et al. Reference Bobbert, Lietaert, Eftekhari, Pouran, Ahmadi, Weinans and Zadpoor2017; Castro et al. Reference Castro, Pires, Santos, Gouveia and Fernandes2019; Montazerian et al. Reference Montazerian, Mohamed, Montazeri, Kheiri, Milani, Kim and Hoorfar2019; Ma et al. Reference Ma2020; Santos et al. Reference Santos, Pires, Gouveia, Castro and Fernandes2020; Pires et al. Reference Pires, Santos, Ruben, Gouveia, Castro and Fernandes2021) measure only

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

, where

$K_{\!Q1}$

, where

![]() ${-\Delta\! P}/{\Delta x}$

is fitted with a straight line to

${-\Delta\! P}/{\Delta x}$

is fitted with a straight line to

![]() $u_s$

. There are several issues. Most importantly, it is rarely ascertained that the flow is within the laminar regime (i.e. only

$u_s$

. There are several issues. Most importantly, it is rarely ascertained that the flow is within the laminar regime (i.e. only

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

is sufficient); the

$K_{\!Q1}$

is sufficient); the

![]() $\Delta x$

over which the

$\Delta x$

over which the

![]() $\Delta\! P$

is estimated in quite short (few centimetres), with questions on fully developed conditions; and the geometrical parameters tested are of limited extent. More recently, using numerical simulations Rathore et al. (Reference Rathore, Mehta, Kumar and Asfer2023) have estimated both

$\Delta\! P$

is estimated in quite short (few centimetres), with questions on fully developed conditions; and the geometrical parameters tested are of limited extent. More recently, using numerical simulations Rathore et al. (Reference Rathore, Mehta, Kumar and Asfer2023) have estimated both

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

and Ahmed & Bottaro (Reference Ahmed and Bottaro2023) have calculated an ‘effective’ permeability (that reduces to the ‘pure’ Darcy permeability at zero Reynolds number) for a set of TPMS geometries. These investigations suggest the need for a systematic and broader parametric experimental study where both

$K_{\!Q2}$

and Ahmed & Bottaro (Reference Ahmed and Bottaro2023) have calculated an ‘effective’ permeability (that reduces to the ‘pure’ Darcy permeability at zero Reynolds number) for a set of TPMS geometries. These investigations suggest the need for a systematic and broader parametric experimental study where both

![]() $\phi$

and flow rate (or Reynolds number) are changed with a clear indication of laminar and turbulent regimes. In fact, there is hardly any experimental data at higher flow rates leading to fully turbulent scenarios. An exception is the recent experiments by Hawken et al. (Reference Hawken, Reid, Clarke, Watson, Fee and Holland2023), who measured pressure drop for a specific TPMS geometry – diamond (which will be discussed later). In this paper, we plan to fill some of the gap by carrying out an experimental study by reporting

$\phi$

and flow rate (or Reynolds number) are changed with a clear indication of laminar and turbulent regimes. In fact, there is hardly any experimental data at higher flow rates leading to fully turbulent scenarios. An exception is the recent experiments by Hawken et al. (Reference Hawken, Reid, Clarke, Watson, Fee and Holland2023), who measured pressure drop for a specific TPMS geometry – diamond (which will be discussed later). In this paper, we plan to fill some of the gap by carrying out an experimental study by reporting

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

(where possible), and covering laminar to turbulent regimes for different TPMS geometries,

$K_{\!Q2}$

(where possible), and covering laminar to turbulent regimes for different TPMS geometries,

![]() $\phi$

and flow rates. Furthermore, we will also vary cell sizes for a fixed

$\phi$

and flow rates. Furthermore, we will also vary cell sizes for a fixed

![]() $\phi$

, and in a particular case, keeping all bulk parameters fixed, we report changes owing to surface roughness (from the 3-D printing technology).

$\phi$

, and in a particular case, keeping all bulk parameters fixed, we report changes owing to surface roughness (from the 3-D printing technology).

Although values of

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

are valuable (for cases that can be fitted by the quadratic form (1.1)) for characterising and designing specific applications, the fact that they are dimensional quantities implies that they vary with each dimensional variable of TPMS (and that also holds for any porous media, and not just TPMS). This is fundamentally unsatisfying, and makes it difficult to compare different geometries as dimensional variables change. Non-dimensional parameters are required to place pressure drop on a firmer footing.

$K_{\!Q2}$

are valuable (for cases that can be fitted by the quadratic form (1.1)) for characterising and designing specific applications, the fact that they are dimensional quantities implies that they vary with each dimensional variable of TPMS (and that also holds for any porous media, and not just TPMS). This is fundamentally unsatisfying, and makes it difficult to compare different geometries as dimensional variables change. Non-dimensional parameters are required to place pressure drop on a firmer footing.

1.2. Non-dimensional pressure drop

If we fix a type of TPMS geometry (e.g. gyroid, primitive, etc.), the governing variables are the length of the (square) unit cell

![]() $l$

or equivalently the ‘pore diameter’

$l$

or equivalently the ‘pore diameter’

![]() $d$

, or the hydraulic diameter,

$d$

, or the hydraulic diameter,

![]() $d_{\!{H}} \equiv 4 V_\textit{fluid}/(\rm wetted\,area)$

, and the porosity

$d_{\!{H}} \equiv 4 V_\textit{fluid}/(\rm wetted\,area)$

, and the porosity

![]() $\phi$

. Along with the fluid and flow variables, these dimensional variables will result in two non-dimensional input parameters:

$\phi$

. Along with the fluid and flow variables, these dimensional variables will result in two non-dimensional input parameters:

![]() $\phi$

and Reynolds number,

$\phi$

and Reynolds number,

![]() $ l u_i/\nu$

or

$ l u_i/\nu$

or

![]() $d u_i/\nu$

or

$d u_i/\nu$

or

![]() $d_{\!{H}}\,u_i/\nu$

, where

$d_{\!{H}}\,u_i/\nu$

, where

![]() $\nu =\mu /\rho$

is the kinematic viscosity and the output non-dimensional pressure gradient is

$\nu =\mu /\rho$

is the kinematic viscosity and the output non-dimensional pressure gradient is

![]() $(-\Delta\! P/\Delta x)/(\rho u_i^2/d_{\!{H}})$

.

$(-\Delta\! P/\Delta x)/(\rho u_i^2/d_{\!{H}})$

.

Further progress on TPMS geometries is possible, if we borrow from the vast amount of existing research in particle porous media (e.g. Bear Reference Bear1988; Richardson Reference Richardson2002). For particles (such as, sand, pebbles, etc.) of some mean diameter, the use of

![]() $d_{\!H}$

(and the intrinsic velocity

$d_{\!H}$

(and the intrinsic velocity

![]() $u_i$

) remarkably reduces the two inputs (

$u_i$

) remarkably reduces the two inputs (

![]() $\phi$

and

$\phi$

and

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

) to just one, because

$d_{\!{H}}$

) to just one, because

![]() $\phi$

and

$\phi$

and

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

can be related via

$d_{\!{H}}$

can be related via

![]() $d_{\!{H}} \equiv 4V_\textit{fluid}/({\rm wetted\,area}) = 4(\phi \,V_\textit{total})/[S\,(1-\phi )V_\textit{total}] = 4\phi /(S\,(1-\phi ))$

, where

$d_{\!{H}} \equiv 4V_\textit{fluid}/({\rm wetted\,area}) = 4(\phi \,V_\textit{total})/[S\,(1-\phi )V_\textit{total}] = 4\phi /(S\,(1-\phi ))$

, where

![]() $S = { ( \rm particle\,wetted\,area)}/V_{\textit{ solid particle}}$

that for a spherical particle of diameter

$S = { ( \rm particle\,wetted\,area)}/V_{\textit{ solid particle}}$

that for a spherical particle of diameter

![]() $d$

reduces to

$d$

reduces to

![]() $S=6/d$

. Following the argument in (1.1), the non-dimensional pressure drop is inversely proportional to the Reynolds number in laminar and should be a constant in fully turbulent regimes, i.e.

$S=6/d$

. Following the argument in (1.1), the non-dimensional pressure drop is inversely proportional to the Reynolds number in laminar and should be a constant in fully turbulent regimes, i.e.

where

![]() $C_1$

and

$C_1$

and

![]() $C_2$

are constants to be determined from experiments. Substitution of

$C_2$

are constants to be determined from experiments. Substitution of

![]() $u_i=u_s/\phi$

and

$u_i=u_s/\phi$

and

![]() $d_{\!{H}}=(2/3) d\,\phi /(1-\phi )$

into (1.2) results in

$d_{\!{H}}=(2/3) d\,\phi /(1-\phi )$

into (1.2) results in

\begin{align} &\frac {-\Delta\! P/\Delta x}{\rho u_s^2/d}\frac {\phi ^3}{(1-\phi )} = \left (\frac {9C_1}{4} \right )\frac {(1-\phi )}{u_s d/\nu } + \frac {3 C_2}{2}, \quad {\rm and\,with} \nonumber \\ & f \equiv \frac {-\Delta\! P/\Delta x}{\rho u_s^2/d}\frac {\phi ^3}{(1-\phi )}, \end{align}

\begin{align} &\frac {-\Delta\! P/\Delta x}{\rho u_s^2/d}\frac {\phi ^3}{(1-\phi )} = \left (\frac {9C_1}{4} \right )\frac {(1-\phi )}{u_s d/\nu } + \frac {3 C_2}{2}, \quad {\rm and\,with} \nonumber \\ & f \equiv \frac {-\Delta\! P/\Delta x}{\rho u_s^2/d}\frac {\phi ^3}{(1-\phi )}, \end{align}

which is the (Carman–Kozeny)–Ergun equation (e.g. Ergun Reference Ergun1952; Wood, He & Apte Reference Wood, He and Apte2020), where

![]() $\textit{Re}_d=u_s d/\nu$

and the constants (

$\textit{Re}_d=u_s d/\nu$

and the constants (

![]() $C_1$

and

$C_1$

and

![]() $C_2$

) are determined from a multitude of packed sphere or particle experiments. The non-dimensional form of (1.4) has a significant advantage over the dimensional equation (1.1). Nevertheless, for TPMS, (1.1) provides an easy method to characterise the geometry, and is the most common method used. The difficulty in using (1.4) in the context of TPMS geometries is the requirement of a pore diameter, which unfortunately cannot be defined uniquely, although the hydraulic diameter

$C_2$

) are determined from a multitude of packed sphere or particle experiments. The non-dimensional form of (1.4) has a significant advantage over the dimensional equation (1.1). Nevertheless, for TPMS, (1.1) provides an easy method to characterise the geometry, and is the most common method used. The difficulty in using (1.4) in the context of TPMS geometries is the requirement of a pore diameter, which unfortunately cannot be defined uniquely, although the hydraulic diameter

![]() $d_{\!H}$

provides an option. However, it is still unclear if an equation similar to (1.4) can be obtained for TPMS. Even with

$d_{\!H}$

provides an option. However, it is still unclear if an equation similar to (1.4) can be obtained for TPMS. Even with

![]() $d_{\!H}$

, as we will show, different TPMS geometries show different

$d_{\!H}$

, as we will show, different TPMS geometries show different

![]() $f(\textit{Re})$

relationships, making it difficult to compare different geometries. Furthermore, it is relatively unknown how surface roughness, which is inherent when different manufacturing techniques or materials are used, will affect the

$f(\textit{Re})$

relationships, making it difficult to compare different geometries. Furthermore, it is relatively unknown how surface roughness, which is inherent when different manufacturing techniques or materials are used, will affect the

![]() $f(\textit{Re})$

relationship.

$f(\textit{Re})$

relationship.

As such, the objective of this paper is two-fold: first, we will present a comprehensive set of pressure drop experiments that are carried out in a relatively long test section (satisfying the fully developed condition) with varying TPMS geometries,

![]() $\phi$

and

$\phi$

and

![]() $l$

. Apart from presenting the two permeability coefficients (cf. (1.1)), we will show the functional relationships

$l$

. Apart from presenting the two permeability coefficients (cf. (1.1)), we will show the functional relationships

![]() $f(\textit{Re})$

for them. Second, to compare different porous media geometries, we will define an ‘equivalent hydraulic diameter’ for TPMS geometries (based on a laminar drag similarity of packed spheres and TPMS) that will allow us to directly compare TPMS with packed particle-bed porous media, and also with each other. This comparison framework will show that some TPMS geometries have lower drag than others within the turbulent regime. We will also show that (1.1) or (1.4), both of which postulate a laminar drag and a fully turbulent drag, is not sufficient to capture some of the TPMS porous media; in fact, some geometries show characteristics of a ‘transitional’ flow similar to flow through rough-walled pipes, suggesting a more nuanced

$f(\textit{Re})$

for them. Second, to compare different porous media geometries, we will define an ‘equivalent hydraulic diameter’ for TPMS geometries (based on a laminar drag similarity of packed spheres and TPMS) that will allow us to directly compare TPMS with packed particle-bed porous media, and also with each other. This comparison framework will show that some TPMS geometries have lower drag than others within the turbulent regime. We will also show that (1.1) or (1.4), both of which postulate a laminar drag and a fully turbulent drag, is not sufficient to capture some of the TPMS porous media; in fact, some geometries show characteristics of a ‘transitional’ flow similar to flow through rough-walled pipes, suggesting a more nuanced

![]() $f(\textit{Re})$

relationship than the usually expected one from (1.4). We note that the equivalent hydraulic diameter concept can be used for other porous media geometries, allowing a broader application beyond the present TPMS geometries. The rest of the paper is arranged as follows: in the next § 2 we present the experimental methods including the design and manufacturing of the TPMS geometry as well as the pressure measurement set-up. The pressure drop results and standard permeability estimates are discussed in § 3. Next, in § 4 we will show the non-dimensional drag and Reynolds number results, and introduce the concept of ‘the equivalent hydraulic diameter’

$f(\textit{Re})$

relationship than the usually expected one from (1.4). We note that the equivalent hydraulic diameter concept can be used for other porous media geometries, allowing a broader application beyond the present TPMS geometries. The rest of the paper is arranged as follows: in the next § 2 we present the experimental methods including the design and manufacturing of the TPMS geometry as well as the pressure measurement set-up. The pressure drop results and standard permeability estimates are discussed in § 3. Next, in § 4 we will show the non-dimensional drag and Reynolds number results, and introduce the concept of ‘the equivalent hydraulic diameter’

![]() $d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

as well as a better estimate of Darcy permeability

$d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

as well as a better estimate of Darcy permeability

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

, denoted by

$K_{\!Q1}$

, denoted by

![]() $K_1$

; this also allows us to compare different TPMS geometries with a common basis. The essential idea is to use the inverse Reynolds number regime that exists in the laminar part of friction factor distribution (the

$K_1$

; this also allows us to compare different TPMS geometries with a common basis. The essential idea is to use the inverse Reynolds number regime that exists in the laminar part of friction factor distribution (the

![]() $f \sim Re^{-1}$

regime) to determine an effective value for the equivalent hydraulic diameter

$f \sim Re^{-1}$

regime) to determine an effective value for the equivalent hydraulic diameter

![]() $d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

. A discussion follows in § 5, where we compare

$d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

. A discussion follows in § 5, where we compare

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

and

$d_{\!{H}}$

and

![]() $d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

, as well as

$d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

, as well as

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_1$

before suggesting an approximate drag model for cases where the quadratic law (1.1) is applicable, and hence, leading to a different estimate for

$K_1$

before suggesting an approximate drag model for cases where the quadratic law (1.1) is applicable, and hence, leading to a different estimate for

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

, called

$K_{\!Q2}$

, called

![]() $K_2$

, which seems to be more reasonable than a direct fitting of data by (1.1). Finally, conclusions are drawn in § 6.

$K_2$

, which seems to be more reasonable than a direct fitting of data by (1.1). Finally, conclusions are drawn in § 6.

2. Experimental methods

This section is divided into two parts. In the first part, we present details of the TPMS porous media we have chosen, including their design and manufacturing. The focus of the second part is on the pressure drop measurement set-up that will incorporate the manufactured TPMS structures, and towards the end we will present validation of experimental set-up with an empty pipe

![]() $-\Delta\! P/\Delta x$

with laminar analytical solution.

$-\Delta\! P/\Delta x$

with laminar analytical solution.

2.1. Triply periodic minimal surface porous media

Among various TPMS porous media (e.g. Lord & Mackay Reference Lord and Mackay2003; Al-Ketan & Abu Al-Rub Reference Al-Ketan and Abu Al-Rub2019), we choose three common geometries: (i) gyroid – represents a complex internal architecture typical of TPMS porous media; (ii) ‘primitive’ – has a distinctive converging–diverging geometric shape; (iii) TPMS-based body-centred cubic (BCC) – owing to its open cell structure. Note that primitive is somewhere between gyroid and BCC in terms of complexity and open cell type.

2.1.1. The TPMS design

There are various ways to design TPMS topologies, and we adopt nodal surface approximation (e.g. Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Liu, Fu, Zhang, Zhang and Zhou2018; Al-Ketan & Abu Al-Rub Reference Al-Ketan and Abu Al-Rub2019) because of the available mathematical expression, which enables us to produce customised topologies using MATLAB. In this method, either a solid or a sheet type topology is designed by choosing a level-set constant

![]() $c$

, which allows us to control the porosity

$c$

, which allows us to control the porosity

![]() $\phi$

by controlling the sheet thickness with different values of

$\phi$

by controlling the sheet thickness with different values of

![]() $\pm c$

. The following equations, respectively, for gyroid, primitive and BCC, which use the implicit method to create zero-valued surfaces solving nodal equations, are the most commonly used mathematical expressions to create TPMS porous media:

$\pm c$

. The following equations, respectively, for gyroid, primitive and BCC, which use the implicit method to create zero-valued surfaces solving nodal equations, are the most commonly used mathematical expressions to create TPMS porous media:

Here

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

are spatial coordinates in the 3-D Cartesian system, with

$z$

are spatial coordinates in the 3-D Cartesian system, with

![]() $k_x$

,

$k_x$

,

![]() $k_y$

and

$k_y$

and

![]() $k_z$

defined by

$k_z$

defined by

![]() $k_i =2\pi {n_i}/{L_i}$

(

$k_i =2\pi {n_i}/{L_i}$

(

![]() $i=x,y,z$

) where

$i=x,y,z$

) where

![]() $n_i$

is the number of unit cells and

$n_i$

is the number of unit cells and

![]() $L_i$

is the total lattice length in the

$L_i$

is the total lattice length in the

![]() $i$

direction. Hence, the length of each unit cell is

$i$

direction. Hence, the length of each unit cell is

![]() $l_i = L_i/n_i$

, where we keep the cell size the same in all directions,

$l_i = L_i/n_i$

, where we keep the cell size the same in all directions,

![]() $l=l_i$

(e.g. Peng & Tran Reference Peng and Tran2020). In practice, (2.1a

), (2.1b

) and (2.1c

) are solved using MATLAB, and its built-in functions of isosurface and isocaps are used to generate desired surfaces of TPMS porous media satisfying the above relationship. Figure 1(a), 1(b) and 1(c) show the unit cell geometry of gyroid, primitive and BCC, respectively, whereas the corresponding figure 1(d), 1(e) and 1( f) show a

$l=l_i$

(e.g. Peng & Tran Reference Peng and Tran2020). In practice, (2.1a

), (2.1b

) and (2.1c

) are solved using MATLAB, and its built-in functions of isosurface and isocaps are used to generate desired surfaces of TPMS porous media satisfying the above relationship. Figure 1(a), 1(b) and 1(c) show the unit cell geometry of gyroid, primitive and BCC, respectively, whereas the corresponding figure 1(d), 1(e) and 1( f) show a

![]() $4\times 4$

cell structure.

$4\times 4$

cell structure.

2.1.2. Pore diameter of TPMS porous media

‘Pore diameter’ is usually used to compare different TPMS geometries and for non-dimensionalisation. There are, however, no exact methods to define pore sizes in TPMS porous media. In practice, pore regions (or voids) are identified first, and then a diameter of a sphere fitting the pore region is used to represent a pore diameter. For example, gyroid and primitive in figure 1(a) and 1(b), respectively, have two distinct pore regions; one is formed by surrounding surfaces in the 3-D and the other one is void space. The former pore region can be fit with the diameter (

![]() $d_{\!p1}$

) of sphere (Rati et al. Reference Rati, Singh, Rai and Kumta2019) and the later region with

$d_{\!p1}$

) of sphere (Rati et al. Reference Rati, Singh, Rai and Kumta2019) and the later region with

![]() $d_{\!p2}$

(Ali & Sen Reference Ali and Sen2018; Asbai-Ghoudan, de Galarreta & Rodriguez-Florez Reference Asbai-Ghoudan, de Galarreta and Rodriguez-Florez2021). So far, none of the literature has defined a pore size for BCC. Thus, we define

$d_{\!p2}$

(Ali & Sen Reference Ali and Sen2018; Asbai-Ghoudan, de Galarreta & Rodriguez-Florez Reference Asbai-Ghoudan, de Galarreta and Rodriguez-Florez2021). So far, none of the literature has defined a pore size for BCC. Thus, we define

![]() $d_{\!p1}$

and

$d_{\!p1}$

and

![]() $d_{\!p2}$

by applying the definition of gyroid and primitive. In figure 1(b), the subpanel in yellow colour shows the cut view of primitive in half to visualise

$d_{\!p2}$

by applying the definition of gyroid and primitive. In figure 1(b), the subpanel in yellow colour shows the cut view of primitive in half to visualise

![]() $d_{\!p2}$

inside. The pore diameters are depicted by red lines in figure 1, and values of (

$d_{\!p2}$

inside. The pore diameters are depicted by red lines in figure 1, and values of (

![]() $d_{\!p1}, d_{\!p2}$

) are presented in the caption of figure 1. Although there are no unique ways to define pore diameters, the two selected diameters provide a rough guide to the pore size.

$d_{\!p1}, d_{\!p2}$

) are presented in the caption of figure 1. Although there are no unique ways to define pore diameters, the two selected diameters provide a rough guide to the pore size.

2.1.3. Manufacturing of TPMS porous media for experiments

Three different 3-D printing manufacturing processes are used to obtain TPMS geometries of the different

![]() $\phi$

and

$\phi$

and

![]() $l$

as described in table 1. We divide the experiments into two sets: Set 1 and Set 2. Set 1 has

$l$

as described in table 1. We divide the experiments into two sets: Set 1 and Set 2. Set 1 has

![]() $l=12$

mm, and is manufactured using a specialised 3-D printer, Stratasys Object 260 Connex3. Using this 3-D printer, the minimum unit cell size that can be obtained without being damaged from harvesting and removal of supporting material is approximately 12 mm. With this optimised length, a unit cell of each TPMS porous media, 12 mm

$l=12$

mm, and is manufactured using a specialised 3-D printer, Stratasys Object 260 Connex3. Using this 3-D printer, the minimum unit cell size that can be obtained without being damaged from harvesting and removal of supporting material is approximately 12 mm. With this optimised length, a unit cell of each TPMS porous media, 12 mm

![]() $\times$

12 mm

$\times$

12 mm

![]() $\times$

12 mm is designed, and based on this unit cell size, the values of

$\times$

12 mm is designed, and based on this unit cell size, the values of

![]() $c$

are optimised for each porous media to create targeted porosity namely,

$c$

are optimised for each porous media to create targeted porosity namely,

![]() $\phi$

= 0.85, 0.70 and 0.55.

$\phi$

= 0.85, 0.70 and 0.55.

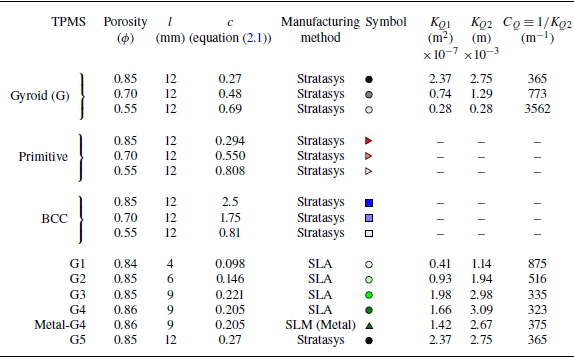

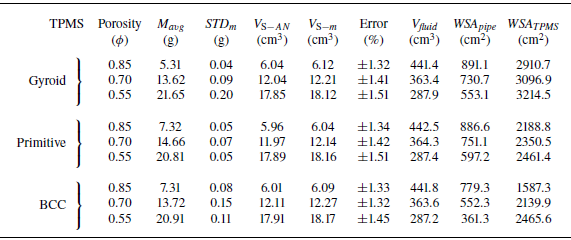

Table 1. Details of the TPMS porous media used in this study. Note that the design of G4 and Metal-G4 are the same; however, the former is manufactured using SLA and the latter by SLM as shown in figure 14(b) and 14(c). The permeabilities

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

(cf. (1.1)) are discussed in § 3.2. The top Set 1 has

$K_{\!Q2}$

(cf. (1.1)) are discussed in § 3.2. The top Set 1 has

![]() $l=12$

mm fixed, whereas the bottom Set 2 has

$l=12$

mm fixed, whereas the bottom Set 2 has

![]() $\phi \approx 0.85$

and varying

$\phi \approx 0.85$

and varying

![]() $l$

. Note that the first and last row are the same.

$l$

. Note that the first and last row are the same.

Set 2 cases in table 1 have a nominally fixed

![]() $\phi \approx 0.85$

and varying

$\phi \approx 0.85$

and varying

![]() $l$

, and are denoted G1 to G4. Stereolithography (SLA), a fine-resolution technology, is used to obtain

$l$

, and are denoted G1 to G4. Stereolithography (SLA), a fine-resolution technology, is used to obtain

![]() $l=$

$l=$

![]() $4$

,

$4$

,

![]() $6$

and

$6$

and

![]() $9$

mm with

$9$

mm with

![]() $\phi \approx 0.85$

. Computational drawings of the three TPMS geometries are shown in figure 2, and photographs of each sample for both sets (cf. table 1) are presented in figure 3. The geometry ‘Metal-G4’ (with

$\phi \approx 0.85$

. Computational drawings of the three TPMS geometries are shown in figure 2, and photographs of each sample for both sets (cf. table 1) are presented in figure 3. The geometry ‘Metal-G4’ (with

![]() $l=9$

mm) is an aluminium TPMS that is 3-D printed with selective laser melting (SLM), and has the same bulk parameters as G4 that is printed in plastic with SLA. The geometry of Metal-G4 has a slightly rougher surface finish than G4 owing to the different 3-D printing process, which becomes apparent when pressure drop is measured. The roughness is estimated to be approximately 50

$l=9$

mm) is an aluminium TPMS that is 3-D printed with selective laser melting (SLM), and has the same bulk parameters as G4 that is printed in plastic with SLA. The geometry of Metal-G4 has a slightly rougher surface finish than G4 owing to the different 3-D printing process, which becomes apparent when pressure drop is measured. The roughness is estimated to be approximately 50

![]() $\mu \textrm {m}$

. Case G5 in Set 2 is with

$\mu \textrm {m}$

. Case G5 in Set 2 is with

![]() $l=12$

mm, and is the same as the top row in Set 1.

$l=12$

mm, and is the same as the top row in Set 1.

Figure 2. All dimensions are in millimetres. The TPMS porous media in the cylinder shape with a diameter of 20.54 mm and a length of 120 mm. Panels (a), (b) and (c) are gyroid, primitive and BCC, respectively, in isometric, side and front views. This corresponds to Set 1 (see table 1) where the unit cell size

![]() $l=12$

mm, and the TPMS are placed inside a pipe of inner diameter 20.6 mm, i.e. little less than two unit cells within the pipe cross-section. Note that for Set 2 (not shown here), the smallest

$l=12$

mm, and the TPMS are placed inside a pipe of inner diameter 20.6 mm, i.e. little less than two unit cells within the pipe cross-section. Note that for Set 2 (not shown here), the smallest

![]() $l=4$

mm, i.e. over five periodic cells within the pipe cross-section.

$l=4$

mm, i.e. over five periodic cells within the pipe cross-section.

Figure 3. Photographs of one of each 3-D-printed TPMS porous media (of a diameter of 20.54 mm and a length of 120 mm) with different porosities. See table 1 for details of G1, G2, etc.

Figure 4. Schematic diagram of the experimental set-up for the pressure drop measurement. Numbers represent corresponding parts. Here

![]() $\unicode{x2460}$

Constant head tank,

$\unicode{x2460}$

Constant head tank,

![]() $\unicode{x2461}$

Flow conditioner,

$\unicode{x2461}$

Flow conditioner,

![]() $\unicode{x2462}$

Entrance length,

$\unicode{x2462}$

Entrance length,

![]() $\unicode{x2463}$

and

$\unicode{x2463}$

and

![]() $\unicode{x2464}$

TPMS porous media are inserted in the entire measurement section. Pressures are measured at three locations as indicated

$\unicode{x2464}$

TPMS porous media are inserted in the entire measurement section. Pressures are measured at three locations as indicated

![]() $P_1$

,

$P_1$

,

![]() $P_2$

, and

$P_2$

, and

![]() $P_3$

in the inset.

$P_3$

in the inset.

![]() $\unicode{x2465}$

Needle valve at the outlet,

$\unicode{x2465}$

Needle valve at the outlet,

![]() $\unicode{x2466}$

Load cell.

$\unicode{x2466}$

Load cell.

To characterise fluid flow through the TPMS porous media, the porous media is inserted in an acrylic pipe of inner diameter 20.6 mm with thickness 1.98 mm. (We will describe the full set-up in § 2.2.) To fill the length of 1.56 m acrylic pipe for Set 1 (and a shorter pipe for Set 2, as described later), a cylinder-shaped porous media is required. This full 1.56 m length of the porous media is manufactured by dividing into 13 smaller pieces of length 120 mm due to the limited size of a built plate in Stratasys Object 260 Connex3 (cf. figures 2 and 3). During the design process, we particularly pay attention to maintaining the complete unit cell as multiple 120 mm pieces are inserted into the acrylic pipe. These 13 pieces are aligned in the pipe to make the 1.56 m of a single porous medium. To cover the first set, nine separate acrylic pipes are used for three different TPMS porous media with three different porosities. For the second set of experiments G1 to G5 with

![]() $l$

=

$l$

=

![]() $4$

,

$4$

,

![]() $6$

and

$6$

and

![]() $9$

mm (cf. table 1), which is conducted after finishing first set of experiments, a shorter pipe of 36 cm is used. The results in different length pipes make hardly any difference (discussed in § 4.3), and the shorter pipe is allowed for a more comprehensive parametric study of the gyroid geometry.

$9$

mm (cf. table 1), which is conducted after finishing first set of experiments, a shorter pipe of 36 cm is used. The results in different length pipes make hardly any difference (discussed in § 4.3), and the shorter pipe is allowed for a more comprehensive parametric study of the gyroid geometry.

2.2. Experimental set-up

A schematic diagram of the experimental set-up for the pressure drop measurements is shown in figure 4. The set-up consists of three main sections: the inlet, the measurement section and the outlet. The inlet has a constant pressure head gravity driven system allowing water to be fed to a nozzle which includes honeycomb as flow straighteners. The fluid travels 1.3 m of empty acrylic pipe with an inner diameter of 20.6 mm before entering the pipe with the porous media inserted (for a pipe length of 1.56 m in Set 1 and 36 cm for Set 2). The entrance length of 1.3 m is such that an approximately fully developed laminar flow enters the porous media section, except for the highest flow rates that we encounter. We note that it is more important to achieve a fully developed flow in the porous section beyond the inlet pipe, which will be confirmed later in the paper.

For each porous media section of the pipe, the first pressure tap is located 2 cm from the start of the porous media section, the second and the third taps are 75 and 150 cm from the first tap. To accurately measure pressure changes at specific locations, five holes – each with a diameter of 4 mm – are made around the upper-half of the circumference to connect pressure taps, allowing for the measurement of the averaged pressure at that location. When the porous media are inserted into the acrylic pipe, extra care is taken to avoid the inserted porous media obstructing the holes. To ensure that the holes are not blocked, the silicone tubes connected to the taps are inspected and confirmed to be completely filled with water.

A manometer fabricated in-house (cf. figure 4) is carefully designed to minimise the effect of surface tension (with a relatively large manometer diameter of 35 mm), and height measurements are carried out with submillimetre resolution using a digital camera with a ruler for calibration. At the outlet, a calibrated load-cell is used to record the change of water mass with time. To detect any abnormality of the load-cell during experiments, a beaker with known weight and volume is used to collect the outlet water with a timer and later compared with the load-cell output.

For Set 2, we have considered a shorter 36 cm pipe. Tests with gyroid

![]() $l=12$

mm and

$l=12$

mm and

![]() $\phi =0.85$

show that the results are almost identical for the longer and 36 cm pipe. For each of the five pipes used in the Set 2 measurements, the first pressure tap is located 3 cm from the start of the gyroid, the second tap is 15 cm from the first and the last one 15 cm from the second tap. Thus, the last tap is 3 cm from the end of the porous medium, as shown in Appendix B (figure 14), where we also describe further details of the experimental set-up for Set 2. This includes special connectors for pressure tapping required for the metal gyroid – case Metal-G4 in table 1.

$\phi =0.85$

show that the results are almost identical for the longer and 36 cm pipe. For each of the five pipes used in the Set 2 measurements, the first pressure tap is located 3 cm from the start of the gyroid, the second tap is 15 cm from the first and the last one 15 cm from the second tap. Thus, the last tap is 3 cm from the end of the porous medium, as shown in Appendix B (figure 14), where we also describe further details of the experimental set-up for Set 2. This includes special connectors for pressure tapping required for the metal gyroid – case Metal-G4 in table 1.

Figure 5. Pressure drop within the measurement section in figure 4 without porous media. Three different symbols are three repeat experiments. (a) Pressure drops over

![]() $L=1.5\rm \,m$

at various superficial velocities (

$L=1.5\rm \,m$

at various superficial velocities (

![]() $u_s$

). The dashed line is the linear fitting. (b) Normalised pressure drop versus

$u_s$

). The dashed line is the linear fitting. (b) Normalised pressure drop versus

![]() $\textit{Re}_{\textit{pipe}}$

on log–log axes and its comparison with analytical

$\textit{Re}_{\textit{pipe}}$

on log–log axes and its comparison with analytical

![]() $64/\textit{Re}_{ { pipe}}$

.

$64/\textit{Re}_{ { pipe}}$

.

2.3. Testing of pressure measurement system

Before conducting experiments on pressure drop in our porous media, we first measure the pressure drop in the acrylic pipe without the porous media. This measurement can then be compared with the analytical solution for laminar pressure drop in smooth pipe flows. By controlling the needle valve at the outlet, shown in figure 4, a range of flow rates is obtained, and the pressure drop at each flow rate is measured. The measurement is repeated three times and all the results are plotted together. Figure 5(a) shows pressure drop per unit length versus superficial velocity (which is the same as bulk velocity in this empty pipe). As the flow rates increase, the pressure drop also increases as shown in figure 5(a), and this increasing trend satisfies the expected linear relationship. Figure 5(b) shows the same data, but plotted on a log–log axes with

![]() $ C_f = (-\Delta\! P/\Delta x)\,{d_{\textit{pipe}}}/(( {1}/{2})\rho u_s^2)$

against

$ C_f = (-\Delta\! P/\Delta x)\,{d_{\textit{pipe}}}/(( {1}/{2})\rho u_s^2)$

against

![]() $\textit{Re}_{\textit{pipe}} = u_s d_{\textit{pipe}}/\nu$

, where

$\textit{Re}_{\textit{pipe}} = u_s d_{\textit{pipe}}/\nu$

, where

![]() $d_{\textit{pipe}}$

is the empty pipe diameter. The data follows the laminar solution of

$d_{\textit{pipe}}$

is the empty pipe diameter. The data follows the laminar solution of

![]() $64/\textit{Re}_{\textit{pipe}}$

reasonably well, providing confidence in our measurement system. Note that the pressure difference across

$64/\textit{Re}_{\textit{pipe}}$

reasonably well, providing confidence in our measurement system. Note that the pressure difference across

![]() $L=1.5$

m is less than

$L=1.5$

m is less than

![]() $5$

Pa m−1, whereas the pressure gradient in our porous media is at least an order of magnitude higher, which further supports the adequacy of the present system.

$5$

Pa m−1, whereas the pressure gradient in our porous media is at least an order of magnitude higher, which further supports the adequacy of the present system.

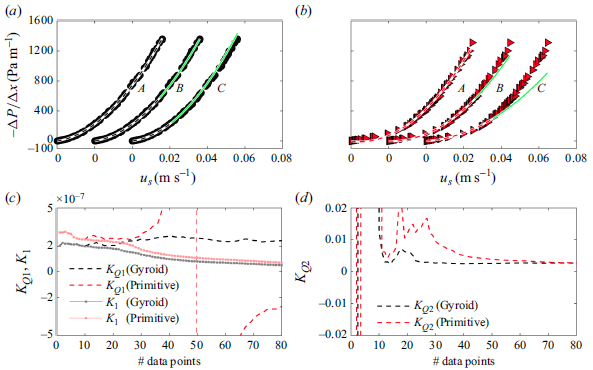

Figure 6. Pressure drops of TPMS porous media with three different porosities – Set 1 in table 1. (a) All pressure drop results. The fitting to extract

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

from (1.1) are shown separately: (b) gyroid; (c) primitive; (d) BCC. Red dashed lines (

$K_{\!Q2}$

from (1.1) are shown separately: (b) gyroid; (c) primitive; (d) BCC. Red dashed lines (![]() ) are the least square fitted (1.1) to data.

) are the least square fitted (1.1) to data.

3. Pressure drop and permeability

We first consider pressure drop measurements for the three TPMS geometries with

![]() $l=12$

mm (Set 1 in table 1), and then for gyroid with varying

$l=12$

mm (Set 1 in table 1), and then for gyroid with varying

![]() $l$

but keeping

$l$

but keeping

![]() $\phi \approx 0.85$

constant (Set 2 in table 1). Subsequently, permeabilities as defined by (1.1) will be estimated for both sets.

$\phi \approx 0.85$

constant (Set 2 in table 1). Subsequently, permeabilities as defined by (1.1) will be estimated for both sets.

3.1. Results of pressure drop measurement

Figure 6(a) presents the experimental results of the net pressure drop (

![]() $-\Delta\! P/\Delta x$

) for the three TPMS geometries of Set 1 (gyroid, primitive and BCC, cf. table 1), which have a fixed unit cell size

$-\Delta\! P/\Delta x$

) for the three TPMS geometries of Set 1 (gyroid, primitive and BCC, cf. table 1), which have a fixed unit cell size

![]() $l=12$

mm, and three different porosities of

$l=12$

mm, and three different porosities of

![]() $\phi =0.85$

, 0.70 and 0.55. The colour of symbols in the figure fades as the

$\phi =0.85$

, 0.70 and 0.55. The colour of symbols in the figure fades as the

![]() $\phi$

decreases. The measurement is repeated five times for each porous media, and the results are plotted together to show the reliability of the results and the repeatability of the measurements. Note that in the repeat experiments we do not try to keep

$\phi$

decreases. The measurement is repeated five times for each porous media, and the results are plotted together to show the reliability of the results and the repeatability of the measurements. Note that in the repeat experiments we do not try to keep

![]() $u_s$

constant. The pressure drop within each TPMS porous medium increases as

$u_s$

constant. The pressure drop within each TPMS porous medium increases as

![]() $\phi$

decreases. This is because a reduction in porosity implies a reduction in the void space for fluid to flow, which increases the viscous and pressure drag for a given

$\phi$

decreases. This is because a reduction in porosity implies a reduction in the void space for fluid to flow, which increases the viscous and pressure drag for a given

![]() $u_s$

and, in turn, increases flow resistance. As such, the largest pressure drops are observed at

$u_s$

and, in turn, increases flow resistance. As such, the largest pressure drops are observed at

![]() $\phi =0.55$

. In general, pressure drops in BCC are lower than those of gyroid and primitive. Compared with primitive at

$\phi =0.55$

. In general, pressure drops in BCC are lower than those of gyroid and primitive. Compared with primitive at

![]() $\phi =$

0.85 and 0.70 in figure 6(a), gyroid shows a larger pressure drop. However, at

$\phi =$

0.85 and 0.70 in figure 6(a), gyroid shows a larger pressure drop. However, at

![]() $\phi =0.55$

, both gyroid and primitive (

$\phi =0.55$

, both gyroid and primitive (![]() and

and ![]() ) have almost identical pressure drops at lower

) have almost identical pressure drops at lower

![]() $u_s$

, and then primitive has a slightly larger pressure drop as the superficial velocity increases beyond

$u_s$

, and then primitive has a slightly larger pressure drop as the superficial velocity increases beyond

![]() $u_s\approx 0.01$

m s−1.

$u_s\approx 0.01$

m s−1.

Furthermore, comparing the results of each porous medium at, say

![]() $\phi =0.85$

(in figure 6

a), a gradual linear increase in pressure drop is observed until

$\phi =0.85$

(in figure 6

a), a gradual linear increase in pressure drop is observed until

![]() $u_s\approx 0.01$

m s−1 (or less) for gyroid and primitive, and

$u_s\approx 0.01$

m s−1 (or less) for gyroid and primitive, and

![]() $u_s\approx 0.04$

m s−1 for BCC. As flow rate increases further, pressure drop increases faster than linear, reflecting the expected change from a viscous to a pressure drag dominated regime as suggested by (1.1). A similar trend is found in other open-cell type porous media, such as metal foams (e.g. Dukhan Reference Dukhan2006; Oun & Kennedy Reference Oun and Kennedy2014) and pack beds of spherical particles (e.g. Ergun Reference Ergun1952; Lovreglio et al. Reference Lovreglio, Das, Buist, Peters, Pel and Kuipers2018).

$u_s\approx 0.04$

m s−1 for BCC. As flow rate increases further, pressure drop increases faster than linear, reflecting the expected change from a viscous to a pressure drag dominated regime as suggested by (1.1). A similar trend is found in other open-cell type porous media, such as metal foams (e.g. Dukhan Reference Dukhan2006; Oun & Kennedy Reference Oun and Kennedy2014) and pack beds of spherical particles (e.g. Ergun Reference Ergun1952; Lovreglio et al. Reference Lovreglio, Das, Buist, Peters, Pel and Kuipers2018).

Another way to interpret figure 6(a) is to hold a constant

![]() $-\Delta\! P/\Delta x$

, say 400 Pa m−1, and move horizontally as

$-\Delta\! P/\Delta x$

, say 400 Pa m−1, and move horizontally as

![]() $u_s$

increases. We notice that for the same pressure drop, gyroid and primitive with

$u_s$

increases. We notice that for the same pressure drop, gyroid and primitive with

![]() $\phi =0.55$

(

$\phi =0.55$

(![]() and

and ![]() ) have the smallest bulk velocities, and then gyroid and primitive at

) have the smallest bulk velocities, and then gyroid and primitive at

![]() $\phi =0.70$

(

$\phi =0.70$

(![]() and

and ![]() ) and subsequently at

) and subsequently at

![]() $\phi =0.85$

(

$\phi =0.85$

(![]() and

and ![]() ), which represents increasing bulk velocity with increasing porosity. The BCC structures allow the highest flow rates among the three geometries, with

), which represents increasing bulk velocity with increasing porosity. The BCC structures allow the highest flow rates among the three geometries, with

![]() $\phi =0.85$

(

$\phi =0.85$

(![]() ) resulting in the highest in the BCC category.

) resulting in the highest in the BCC category.

The pressure drop results for Set 2, where

![]() $\phi \approx 0.85$

and the unit cell size

$\phi \approx 0.85$

and the unit cell size

![]() $l$

vary, are presented in figure 7(a). Not surprisingly, increasing

$l$

vary, are presented in figure 7(a). Not surprisingly, increasing

![]() $l=$

4, 6, 9, 12 mm corresponding to G1, G2, G3 (or G4) and G5 results in a reduction of

$l=$

4, 6, 9, 12 mm corresponding to G1, G2, G3 (or G4) and G5 results in a reduction of

![]() $-\Delta\! P/\Delta x$

. Note that the abscissa of figure 7(a) is larger compared with that in figure 6(a) to accommodate the increased pressure resulting from smaller

$-\Delta\! P/\Delta x$

. Note that the abscissa of figure 7(a) is larger compared with that in figure 6(a) to accommodate the increased pressure resulting from smaller

![]() $l$

. Interestingly, comparing the pressure drop results of porous media manufactured using SLA technique with plastic (G4) with SLM in metal (Metal-G4) with the same porosity and unit cell size, the pressure drop in Metal-G4 (SLM) is much larger than G4 (SLA). When

$l$

. Interestingly, comparing the pressure drop results of porous media manufactured using SLA technique with plastic (G4) with SLM in metal (Metal-G4) with the same porosity and unit cell size, the pressure drop in Metal-G4 (SLM) is much larger than G4 (SLA). When

![]() $u_s \lessapprox 0.02$

m s−1, the trend of pressure drop is similar. However, as velocity increases, the pressure drop in the SLM sample increases dramatically. It is known that metal 3-D printing with SLM cannot produce surfaces that are as smooth as in SLA using plastic, and this increased surface roughness is likely the cause of the elevated pressure drop even though the bulk characteristics of both Metal-G4 and G4 are the same. In figure 7(a), in a manner similar to figure 6(a), the linear trend at smaller

$u_s \lessapprox 0.02$

m s−1, the trend of pressure drop is similar. However, as velocity increases, the pressure drop in the SLM sample increases dramatically. It is known that metal 3-D printing with SLM cannot produce surfaces that are as smooth as in SLA using plastic, and this increased surface roughness is likely the cause of the elevated pressure drop even though the bulk characteristics of both Metal-G4 and G4 are the same. In figure 7(a), in a manner similar to figure 6(a), the linear trend at smaller

![]() $u_s$

gives way to a quadratic-like dependence at higher

$u_s$

gives way to a quadratic-like dependence at higher

![]() $u_s$

. This linear and quadratic variation in net pressure drop is quantified next following (1.1) in terms of

$u_s$

. This linear and quadratic variation in net pressure drop is quantified next following (1.1) in terms of

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

.

$K_{\!Q2}$

.

3.2. Permeability of TPMS porous media

Two permeability coefficients in (1.1) are usually obtained by fitting the experimental results with a second-order polynomial equation in

![]() $u_s$

. In the fitted equation, the coefficients of linear and quadratic terms correspond, respectively, to

$u_s$

. In the fitted equation, the coefficients of linear and quadratic terms correspond, respectively, to

![]() $\mu /K_{\!Q1}$

and

$\mu /K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $\rho /K_{\!Q2}$

. Since dynamic viscosity and density of the working liquid are known,

$\rho /K_{\!Q2}$

. Since dynamic viscosity and density of the working liquid are known,

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

can be calculated. The least-square fitted equations to the pressure drop data of gyroid are shown in red dashed lines (

$K_{\!Q2}$

can be calculated. The least-square fitted equations to the pressure drop data of gyroid are shown in red dashed lines (![]() ) in figure 6(b) for Set 1 and in figure 7(b) for Set 2, and all the data had an

) in figure 6(b) for Set 1 and in figure 7(b) for Set 2, and all the data had an

![]() $R^2\gt 0.99$

. The two determined coefficients

$R^2\gt 0.99$

. The two determined coefficients

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

for gyroid are tabulated in table 1, with the common trend that the values of

$K_{\!Q2}$

for gyroid are tabulated in table 1, with the common trend that the values of

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

decrease as porosity decreases. In other words, ‘form drag’ coefficient

$K_{\!Q2}$

decrease as porosity decreases. In other words, ‘form drag’ coefficient

![]() $C_Q\equiv 1/K_{\!Q2}$

in table 1 increases significantly as the internal structure of the gyroid acts as a blockage or resistance against the fluid flow. The results from Set 2, which consists only of gyroid with varying

$C_Q\equiv 1/K_{\!Q2}$

in table 1 increases significantly as the internal structure of the gyroid acts as a blockage or resistance against the fluid flow. The results from Set 2, which consists only of gyroid with varying

![]() $l$

and similar

$l$

and similar

![]() $\phi$

, are presented in figure 7(b) and table 1. The table shows that with increasing

$\phi$

, are presented in figure 7(b) and table 1. The table shows that with increasing

![]() $l$

(i.e. larger void regions) Darcy permeability

$l$

(i.e. larger void regions) Darcy permeability

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

increases, whereas

$K_{\!Q1}$

increases, whereas

![]() $C_Q$

reduces. The case with Metal 3-D printing (Metal-G4) exhibits a higher

$C_Q$

reduces. The case with Metal 3-D printing (Metal-G4) exhibits a higher

![]() $C_Q$

(i.e. ‘drag’) compared with the case G4 that has the same bulk properties but better surface finish. This again reinforces the comments made earlier about the increased drag owing to enhanced surface roughness in metal 3-D printed porous media.

$C_Q$

(i.e. ‘drag’) compared with the case G4 that has the same bulk properties but better surface finish. This again reinforces the comments made earlier about the increased drag owing to enhanced surface roughness in metal 3-D printed porous media.

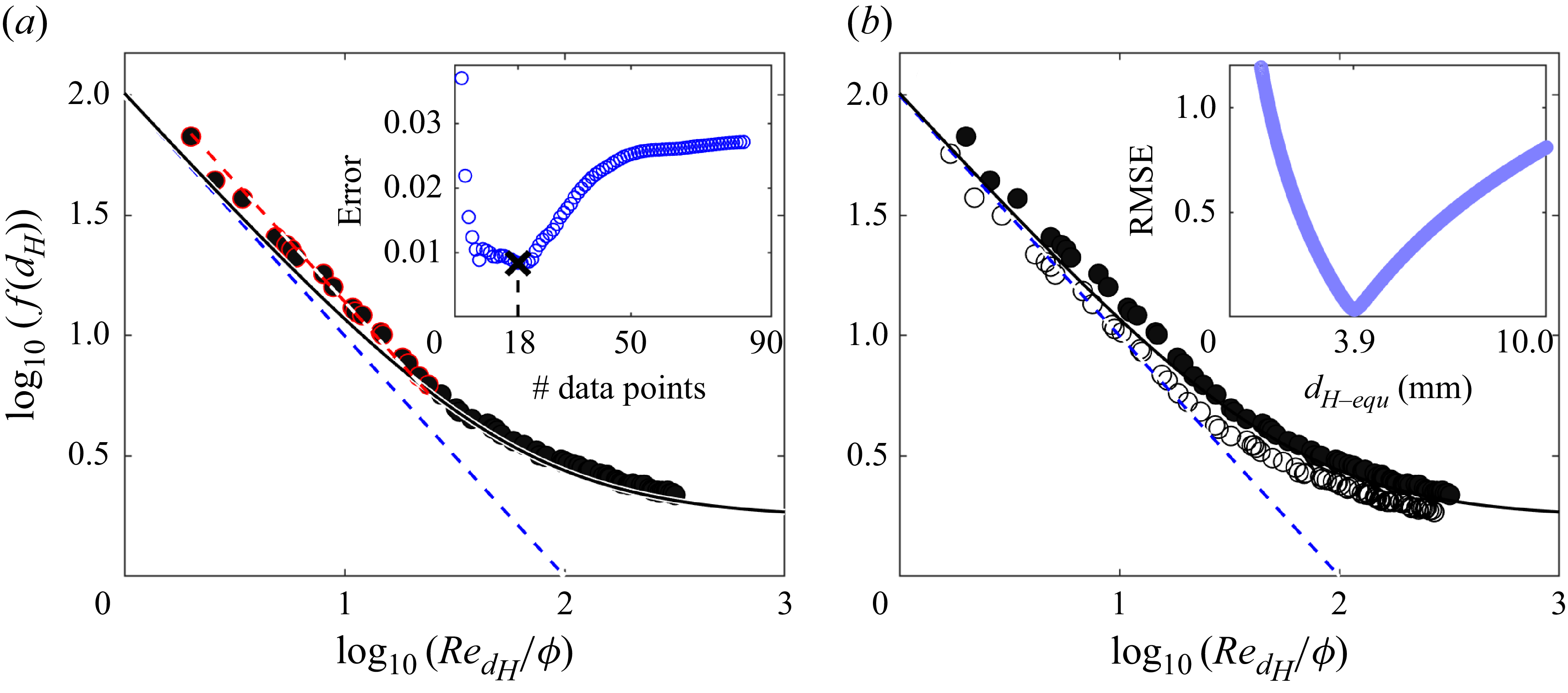

Figure 9. Friction factor

![]() $f$

(see (4.1)) distributions based on the hydraulic diameter

$f$

(see (4.1)) distributions based on the hydraulic diameter

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

in (a), and with

$d_{\!{H}}$

in (a), and with

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

replaced with

$d_{\!{H}}$

replaced with

![]() $d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

in (b). The black solid line represents the Ergun equation (4.2) written in

$d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

in (b). The black solid line represents the Ergun equation (4.2) written in

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

, whereas the blue dashed line is the linear part (i.e. only first term on the right-hand side) of (4.2).

$d_{\!{H}}$

, whereas the blue dashed line is the linear part (i.e. only first term on the right-hand side) of (4.2).

Interestingly, and rather surprisingly, an attempt to fit (1.1) to the data of primitive and BCC in the least-square sense results in an erratic and sometimes a negative coefficient for

![]() $u_s$

(i.e. a negative

$u_s$

(i.e. a negative

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

) that is non-physical. An attempt at forcing a least-square fit with a non-negative coefficient for

$K_{\!Q1}$

) that is non-physical. An attempt at forcing a least-square fit with a non-negative coefficient for

![]() $u_s$

results in a value of zero for

$u_s$

results in a value of zero for

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

, again non-physical. This mathematical anomaly points to a physical difference between the form of pressure drop data for gyroid and the other two geometries (i.e. primitive and BCC). A careful observation of some of the primitive and BCC data in figure 6(a) or 6(c) and 6(d) shows that the pressure drop functions ‘bend outwards’ for higher velocities, making a linear plus a quadratic fit less viable. This becomes clear later (cf. figures 8 or 9) where the friction factor versus

$K_{\!Q1}$

, again non-physical. This mathematical anomaly points to a physical difference between the form of pressure drop data for gyroid and the other two geometries (i.e. primitive and BCC). A careful observation of some of the primitive and BCC data in figure 6(a) or 6(c) and 6(d) shows that the pressure drop functions ‘bend outwards’ for higher velocities, making a linear plus a quadratic fit less viable. This becomes clear later (cf. figures 8 or 9) where the friction factor versus

![]() $Re/\phi$

trend for primitive and BCC differs considerably from gyroid. As will be discussed later, primitive and BCC have a behaviour that has similarities to a pipe flow (i.e. connected voids), which has a substantial ‘transitions’ region apart from the laminar to turbulent region. An additional issue encountered when fitting (1.1) to all cases is related to the number of data points used in fitting. As shown in Appendix A, for gyroid (

$Re/\phi$

trend for primitive and BCC differs considerably from gyroid. As will be discussed later, primitive and BCC have a behaviour that has similarities to a pipe flow (i.e. connected voids), which has a substantial ‘transitions’ region apart from the laminar to turbulent region. An additional issue encountered when fitting (1.1) to all cases is related to the number of data points used in fitting. As shown in Appendix A, for gyroid (

![]() $\phi =0.85$

), changing the number of data points does not change

$\phi =0.85$

), changing the number of data points does not change

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

beyond 10 %–20 %, whereas for primitive (and BCC), one could obtain a positive

$K_{\!Q2}$

beyond 10 %–20 %, whereas for primitive (and BCC), one could obtain a positive

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

for a reduced and a negative

$K_{\!Q1}$

for a reduced and a negative

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

for an increased number of data points. Appendix A further attempts to highlight these variations using one example from each gyroid and primitive by successively increasing the number of data points in fitting (1.1), starting from

$K_{\!Q1}$

for an increased number of data points. Appendix A further attempts to highlight these variations using one example from each gyroid and primitive by successively increasing the number of data points in fitting (1.1), starting from

![]() $u_s=0$

. In fact, the role of these large connected void regions presented in primitive and BBC remains to be fully investigated and it seems that this is a potential reason for the negative values of

$u_s=0$

. In fact, the role of these large connected void regions presented in primitive and BBC remains to be fully investigated and it seems that this is a potential reason for the negative values of

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

.

$K_{\!Q2}$

.

Although empirically determined

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

using (1.1) are widely used in the study of metal foams (and other porous media) to provide valuable information for modelling a specific geometry or configuration, it has several limitations. (i) For cases where a fitting (1.1), such as for gyroid in our experiments or multitude of other porous media like metal form or packed bed of spheres, dimensional

$K_{\!Q2}$

using (1.1) are widely used in the study of metal foams (and other porous media) to provide valuable information for modelling a specific geometry or configuration, it has several limitations. (i) For cases where a fitting (1.1), such as for gyroid in our experiments or multitude of other porous media like metal form or packed bed of spheres, dimensional

![]() $K_{\!Q1}$

and

$K_{\!Q1}$

and

![]() $K_{\!Q2}$

are less satisfactory, which also limits comparison between different geometries. (ii) There are other geometries, such as primitive and BCC in our case, where (1.1) cannot fit the data, owing to a different physical mechanism at play. (iii) Furthermore, a naive fitting of (1.1) produces different results for varying data count, especially for the ‘non-canonical’ porous media like primitive and BCC, and to a lesser extent in gyroid.

$K_{\!Q2}$

are less satisfactory, which also limits comparison between different geometries. (ii) There are other geometries, such as primitive and BCC in our case, where (1.1) cannot fit the data, owing to a different physical mechanism at play. (iii) Furthermore, a naive fitting of (1.1) produces different results for varying data count, especially for the ‘non-canonical’ porous media like primitive and BCC, and to a lesser extent in gyroid.

Some of these issues will be resolved in the next section, and in doing so, we will also demonstrate a procedure that will allow a unified comparison of all porous media. The non-dimensional pressure drop (

![]() $f$

) versus Reynolds number is the starting point. The difficulty, however, is the definition of a length scale required for non-dimensionalisation. We will begin with the ‘pore diameters’ defined in § 2.1.2 as the length scale, before moving to the hydraulic diameter (

$f$

) versus Reynolds number is the starting point. The difficulty, however, is the definition of a length scale required for non-dimensionalisation. We will begin with the ‘pore diameters’ defined in § 2.1.2 as the length scale, before moving to the hydraulic diameter (

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

). As we shall see,

$d_{\!{H}}$

). As we shall see,

![]() $f$

versus

$f$

versus

![]() $Re$

based on

$Re$

based on

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

by itself is also not completely satisfactory, which will lead us to define an ‘equivalent hydraulic diameter’ (

$d_{\!{H}}$

by itself is also not completely satisfactory, which will lead us to define an ‘equivalent hydraulic diameter’ (

![]() $d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

) to characterise and compare various porous media. We will commence with the data collected for Set 1 (for fixed

$d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

) to characterise and compare various porous media. We will commence with the data collected for Set 1 (for fixed

![]() $l=12$

mm, and varying

$l=12$

mm, and varying

![]() $\phi$

and geometry), and towards the end show results from Set 2 (fixed

$\phi$

and geometry), and towards the end show results from Set 2 (fixed

![]() $\phi \approx 0.85$

and varying

$\phi \approx 0.85$

and varying

![]() $l$

).

$l$

).

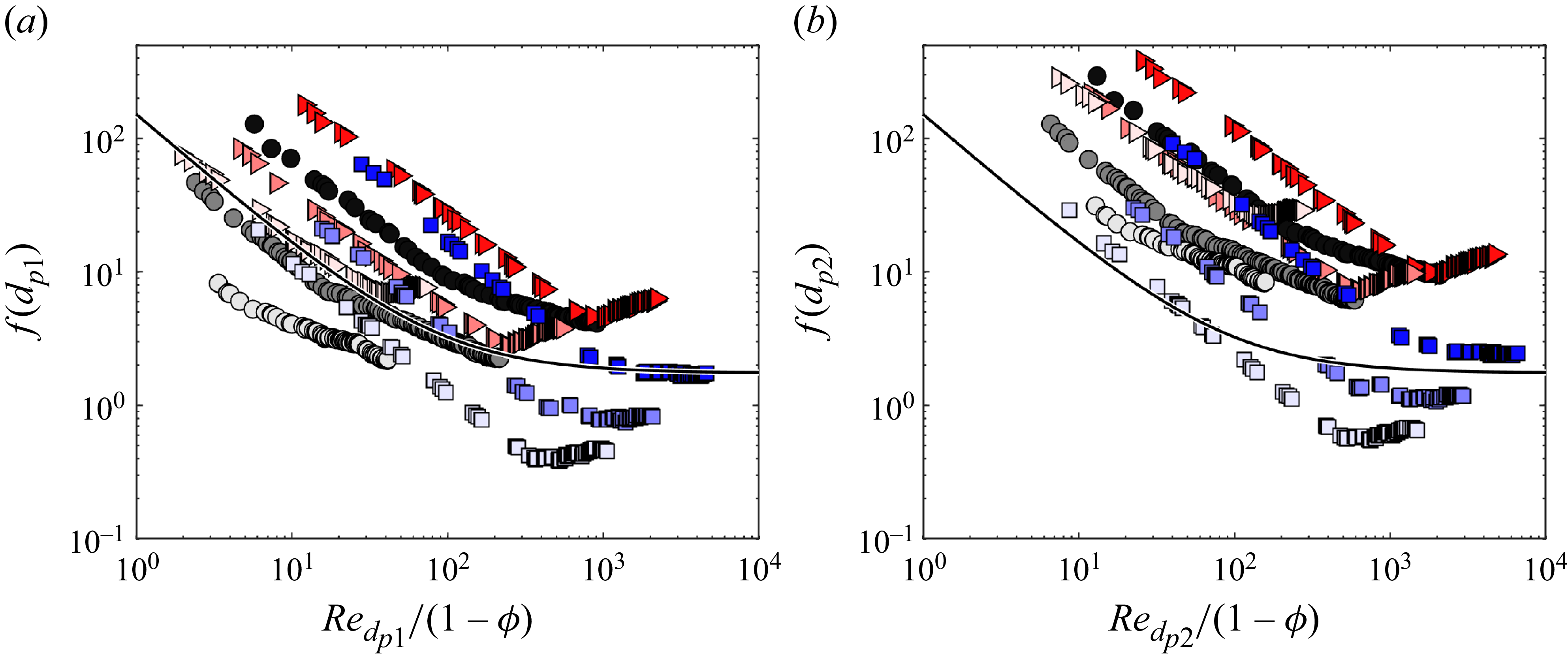

4. Non-dimensional pressure drop versus Reynolds number correlations

The pressure drop is non-dimensionalised, and represented by

![]() $f$

as defined in (1.3). For the pore or sphere diameter

$f$

as defined in (1.3). For the pore or sphere diameter

![]() $d$

that appears in (1.3), we use the two pore diameters,

$d$

that appears in (1.3), we use the two pore diameters,

![]() $d_{\!p1}$

and

$d_{\!p1}$

and

![]() $d_{\!p2}$

discussed in § 2.1.2. Our experimental results of Set 1, with

$d_{\!p2}$

discussed in § 2.1.2. Our experimental results of Set 1, with

![]() $\textit{Re}_{\!p1} \equiv d_{\!p1} u_s/\nu$

and similarly for

$\textit{Re}_{\!p1} \equiv d_{\!p1} u_s/\nu$

and similarly for

![]() $\textit{Re}_{\!p2}$

, are compared with the Ergun equation (1.4), and plotted in figure 8(a) and 8(b), respectively, for

$\textit{Re}_{\!p2}$

, are compared with the Ergun equation (1.4), and plotted in figure 8(a) and 8(b), respectively, for

![]() $d_{\!p1}$

and

$d_{\!p1}$

and

![]() $d_{\!p2}$

. The most set of data show the expected

$d_{\!p2}$

. The most set of data show the expected

![]() $f\sim 1/Re$

behaviour at lower

$f\sim 1/Re$

behaviour at lower

![]() $Re$

, and

$Re$

, and

![]() $f$

tending towards a constant value at increasing

$f$

tending towards a constant value at increasing

![]() $Re$

. Nevertheless, figure 8 demonstrates how the experimental results might seem to vary depending on the definition of the ‘pore diameter’. This could cause significant confusion in applications when TPMS porous media are used, because no universally accepted definition of pore size exists, and more significantly, the existing definitions are not related to fluid flows, rather defined by convenient geometric arguments. The uniqueness issue of the pore diameter could be solved by using the hydraulic diameter, which is now considered. Nevertheless, we note that in most geometries, an experimental estimation of the hydraulic diameter is practically unattainable; in what follows, we will present an ‘equivalent hydraulic diameter’ that overcomes these issues and is physically meaningful.

$Re$

. Nevertheless, figure 8 demonstrates how the experimental results might seem to vary depending on the definition of the ‘pore diameter’. This could cause significant confusion in applications when TPMS porous media are used, because no universally accepted definition of pore size exists, and more significantly, the existing definitions are not related to fluid flows, rather defined by convenient geometric arguments. The uniqueness issue of the pore diameter could be solved by using the hydraulic diameter, which is now considered. Nevertheless, we note that in most geometries, an experimental estimation of the hydraulic diameter is practically unattainable; in what follows, we will present an ‘equivalent hydraulic diameter’ that overcomes these issues and is physically meaningful.

4.1. Hydraulic diameter and resulting

$f$

versus

$f$

versus

$Re$

distribution

$Re$

distribution

The concept of hydraulic diameter usually works well for similar geometries in diverse fluid flow situations. As discussed in § 1 hydraulic diameter

![]() $d_{\!{H}} \equiv 4V_\textit{fluid}/({\rm wetted\,area})$

, an estimation of

$d_{\!{H}} \equiv 4V_\textit{fluid}/({\rm wetted\,area})$

, an estimation of

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

requires void volume available for flow (

$d_{\!{H}}$

requires void volume available for flow (

![]() $V_\textit{fluid}$

) that is related to porosity, the wetted surface area that includes the total surface area of TPMS porous media, and the surface area of the acrylic pipe that does not contact TPMS porous media.

$V_\textit{fluid}$

) that is related to porosity, the wetted surface area that includes the total surface area of TPMS porous media, and the surface area of the acrylic pipe that does not contact TPMS porous media.

Appendix C provides details of extracting

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

. Briefly, Autodesk Netfabb computer software is used to estimate

$d_{\!{H}}$

. Briefly, Autodesk Netfabb computer software is used to estimate

![]() $V_\textit{fluid}$

and the wetted surface area. The values of

$V_\textit{fluid}$

and the wetted surface area. The values of

![]() $V_\textit{fluid}$

are experimentally estimated by immersing samples in water and calculating the increased volume. The difference between computer-estimated and experimental values is

$V_\textit{fluid}$

are experimentally estimated by immersing samples in water and calculating the increased volume. The difference between computer-estimated and experimental values is

![]() $\lessapprox 1.5\,\%$

. The final computed

$\lessapprox 1.5\,\%$

. The final computed

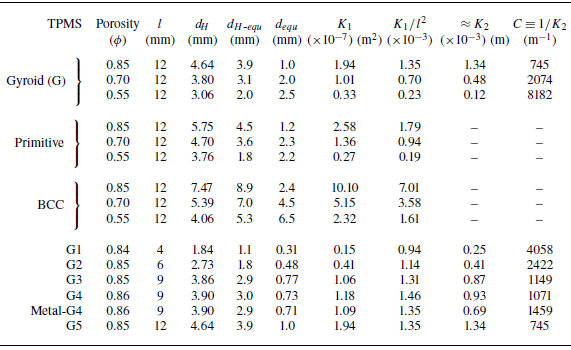

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

values for all samples are reported in table 2. Consistent with our expectation that smaller

$d_{\!{H}}$

values for all samples are reported in table 2. Consistent with our expectation that smaller

![]() $\phi$

should result in a higher pressure drop and hence equivalent to a packed bed of smaller spheres, Set 1 data shows that reduction in

$\phi$

should result in a higher pressure drop and hence equivalent to a packed bed of smaller spheres, Set 1 data shows that reduction in

![]() $\phi$

results in a reduced

$\phi$

results in a reduced

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

. Likewise, in Set 2, with a fixed

$d_{\!{H}}$

. Likewise, in Set 2, with a fixed

![]() $\phi \approx 0.85$

, an increase in unit cell size

$\phi \approx 0.85$

, an increase in unit cell size

![]() $l$

shows an increased

$l$

shows an increased

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

.

$d_{\!{H}}$

.

Table 2. Equivalent hydraulic diameter

![]() $d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

and equivalent sphere diameter

$d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}$

and equivalent sphere diameter

![]() $d_{{equ}}$

;

$d_{{equ}}$

;

![]() $d_{{equ}} = (3/2)d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}(1-\phi )/\phi$

; the Darcy permeability

$d_{{equ}} = (3/2)d_{{H\hbox{-}\textit{equ}}}(1-\phi )/\phi$

; the Darcy permeability

![]() $K_1$

from (4.5); and

$K_1$

from (4.5); and

![]() $K_2$

estimated in § 5.

$K_2$

estimated in § 5.

To plot

![]() $f$

versus Reynolds number, the Ergun equation (1.4) is modified in-terms of the hydraulic diameter

$f$

versus Reynolds number, the Ergun equation (1.4) is modified in-terms of the hydraulic diameter

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

by using,

$d_{\!{H}}$

by using,

![]() $d=(3/2) d_{\!{H}}\,(1-\phi )/\phi$

, and with

$d=(3/2) d_{\!{H}}\,(1-\phi )/\phi$

, and with

where,

![]() $\textit{Re}_{d_{\!{H}}} = u_s\,d_{\!{H}}/\nu$

. Note that the derivation of the Ergun equation begins with

$\textit{Re}_{d_{\!{H}}} = u_s\,d_{\!{H}}/\nu$

. Note that the derivation of the Ergun equation begins with

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

(rather than

$d_{\!{H}}$

(rather than

![]() $d$

); so, in that sense (4.2) is more broadly applicable than (1.4). Recall that the constants 150 and 1.75 in both (4.2) and (1.4) are for random packed spheres.

$d$

); so, in that sense (4.2) is more broadly applicable than (1.4). Recall that the constants 150 and 1.75 in both (4.2) and (1.4) are for random packed spheres.

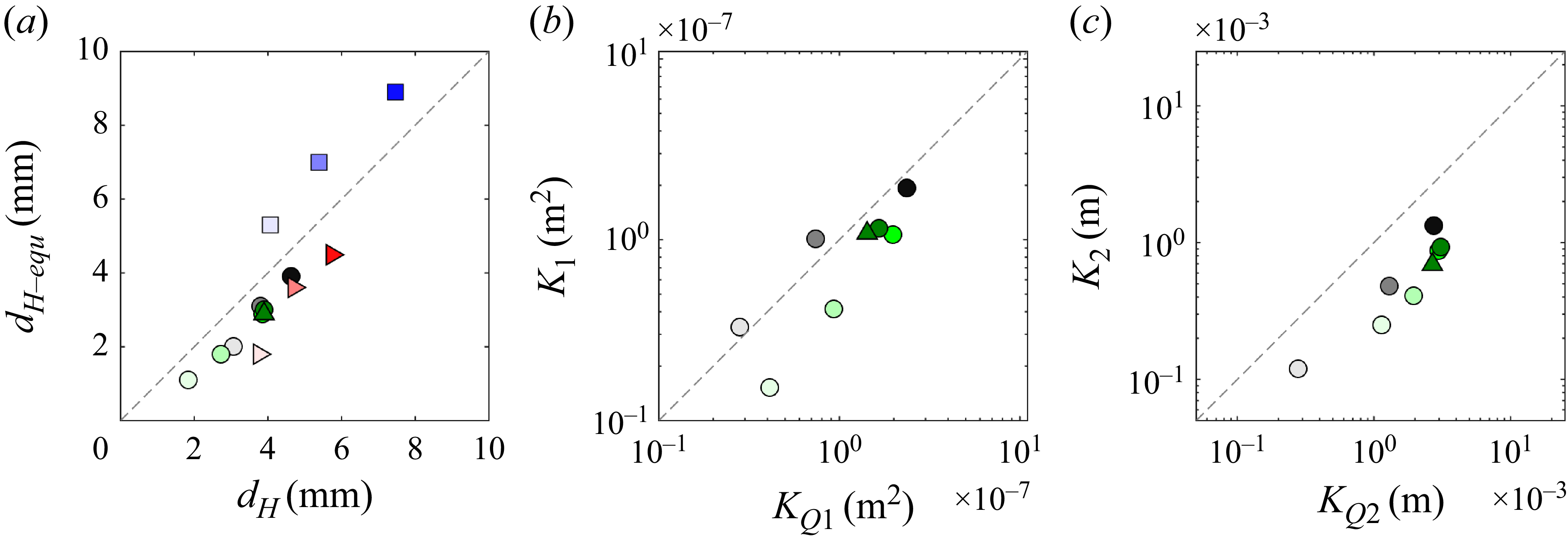

Using

![]() $d_{\!{H}}$

from table 2 and

$d_{\!{H}}$

from table 2 and

![]() $f$

evaluated as in (4.1), figure 9(a) shows Set 1 data on a log–log

$f$

evaluated as in (4.1), figure 9(a) shows Set 1 data on a log–log

![]() $f$

versus

$f$

versus

![]() $\textit{Re}_{d_{\!{H}}}$

plot using appropriate symbols for each case. The Ergun equation (4.2) is presented with a black solid line. The net pressure drop, composed of viscous and pressure drag, dominates, respectively, at lower and higher

$\textit{Re}_{d_{\!{H}}}$

plot using appropriate symbols for each case. The Ergun equation (4.2) is presented with a black solid line. The net pressure drop, composed of viscous and pressure drag, dominates, respectively, at lower and higher

![]() $\textit{Re}_{d_{\!{H}}}$

. Data from TPMS porous media start at different ordinate positions, but most porous media show a linear relationship that is suggested by the Ergun equation for low

$\textit{Re}_{d_{\!{H}}}$