Introduction

Decapod crustaceans are some of the most successful invasive species across freshwater, brackish, and marine ecosystems worldwide (Karatayev et al., Reference Karatayev, Burlakova, Padilla, Mastitsky and Olenin2009; Brockerhoff and McLay, Reference Brockerhoff, McLay, Galil, Clark and Carlton2011; Hänfling et al., Reference Hänfling, Edwards and Gherardi2011; Rato et al., Reference Rato, Crespo and Lemos2021). Of these invasive decapods, the brachyuran crabs are highly successful (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Therriault and Côté2017). Often with broad diets and environmental tolerances (Hänfling et al., Reference Hänfling, Edwards and Gherardi2011), crabs can establish high population densities (Lord and Williams, Reference Lord and Williams2017; Hilliam and Tuck, Reference Hilliam and Tuck2022; Castriota et al., Reference Castriota, Falautano and Perzia2024) and cause considerable impacts in their new environments through predation (Kotta et al., Reference Kotta, Wernberg, Jänes, Kotta, Nurkse, Pärnoja and Orav-Kotta2018), competition (Baillie and Grabowski, Reference Baillie and Grabowski2018), introduced parasites (Frizzera et al., Reference Frizzera, Bojko, Cremonte and Vázquez2021), and physical manipulation of their habitats (Rudnick et al., Reference Rudnick, Chan and Resh2005; Gonzalez et al., Reference Gonzalez, Ruiz, Chang and Boyer2024).

Within the Brachyura, portunid swimming crabs are the most frequently reported alien species (sensu Colautti and MacIsaac, Reference Colautti and MacIsaac2004), particularly those in the genus Charybdis De Haan, 1883 (Brockerhoff and McLay, Reference Brockerhoff, McLay, Galil, Clark and Carlton2011; Swart et al., Reference Swart, Visser and Robinson2018). At least six species from two Charybdis subgenera (C. (Charybdis) and C. (Archias)) have been reported globally as alien species, and at least five of these have established invasive populations (Table 1). While several of these species are Suez invaders, spreading from the Red Sea into the Mediterranean and becoming established, the most common vector for translocations appears to be via shipping (Table 1).

Table 1. Examples of non-native populations or records of Charybdis spp

* Not explicitly stated in description.

The Port of Southampton is one of the busiest ports in the UK, handling a large number of container ships, car transporters, and cruise ships (Asgari et al., Reference Asgari, Hassani, Jones and Nguye2015; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Williams and Preston2020). Large vessel movements connect Southampton to more than 200 other ports worldwide, and the region is a hotspot for recreational boating, increasing localised connections (Tidbury et al., Reference Tidbury, Taylor, Copp, Garnacho and Stebbing2016). With hull fouling, ballast, and bilge water serving as vectors for the transport of alien species, this region has been identified as being at high risk from invasive marine species (Tidbury et al., Reference Tidbury, Taylor, Copp, Garnacho and Stebbing2016). Indeed, Southampton Water – the tidal estuary of the Rivers Itchen and Test – has the highest number of alien marine species on the UK south coast (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Bishop, Carlton, Dyrynda, Farnham, Gonzalez, Jacobs, Lambert, Lambert, Nielsen and Pederson2006; Minchin et al., Reference Minchin, Cook and Clark2013; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Wood and Bishop2022). However, barring a single record of the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis, no non-native crabs have been reported in this region (GBIF, 2025).

Here, we report an observation of a single specimen of the alien portunid, Charybdis (Archias) hoplites in Southampton Water. This represents the first record of this species outside its native range and the most northerly record of any species within the genus. As this species is rarely discussed in the literature, this observation of C. (A.) hoplites also provides opportunities to clarify its diagnostic characters, aiding future studies and monitoring efforts.

Materials and methods

Specimen collection

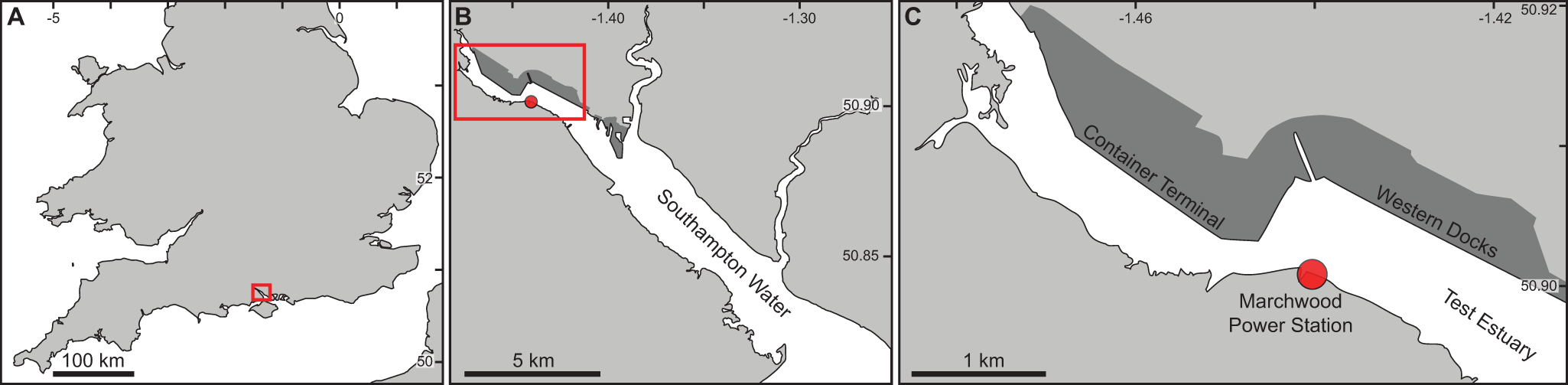

The recently deceased specimen of Charybdis (Archias) hoplites was collected from the Test Estuary, Southampton, United Kingdom, at the cooling water intake of Marchwood Power Station (50.9014°, −1.4407°; Figure 1), on the 24th of July 2025. The water temperature at the collection site was 21°C, and the salinity was 33 psu; both within the expected range for this time of year (Environment Agency, 2025). The specimen was collected during a monthly 24 h impingement survey assessing the fish and invertebrates screened prior to entrainment into the power station’s cooling water system. The specimen was immediately identified as unusual due to its elongate sixth anterolateral teeth and was photographed in the field and preserved in 70% isopropanol, with the second and third left pereiopods removed and preserved separately in 80% ethanol for molecular analysis.

Figure 1. Collection location of Charybdis (Archias) hoplites, Marchwood Power Station, Test Estuary, Southampton Water, UK. Red rectangles in panels (A) and (B) show positions of subsequent, finer-scale panels. The red circles in panels (B) and (C) indicate the location of the Marchwood Power Station cooling water intake. Dark grey shaded areas in panels (B) and (C) indicate the location of the Port of Southampton. Latitude and longitude are presented in decimal degrees.

DNA amplification and phylogenetics

DNA was extracted from muscle tissue of the left second pereiopod of the specimen using a PureLink™ Genomic DNA kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol with two replicate 40 μl elutions.

We sequenced a segment of the mitochondrial gene cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) using the primers dgLCO-1490 and dgHCO-2198 (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003). A PCR reaction (50 μl) was made using 25 μl of OneTaq ® 2X Master Mix (New England Biolabs), 1 μl of each primer (10 μM), 10 μl of template DNA, and 13 μl of Milli-Q water. PCR thermocycling conditions were 2.5 min at 94°C for initial denaturation, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 90°C (denaturation), 1 min at 48°C (annealing), 1 min at 72°C (extension), and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. PCR success was confirmed by gel electrophoresis, and the amplified product was purified using a peqGOLD Cycle-Pure KIT (VWR International) before Sanger sequencing at Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany.

Sequence data were manually trimmed by removing low-quality bases at the ends of raw reads, and bidirectional reads were aligned in ChromasPro 2.2. The sequence data were then compared against the NCBI GenBank database (Sayers et al., Reference Sayers, Beck, Bolton, Brister, Chan, Connor, Feldgarden, Fine, Funk, Hoffman and Kannan2025) using BLASTn (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Zaretskaya, Raytselis, Merezhuk, McGinnis and Madden2008).

To further investigate relationships among closely related taxa and to help identify our specimen, we created a Bayesian phylogeny. Sequence data were downloaded for the 50 closest hits from our BLASTn search, along with three sequences from the closely related genus Thalamita (Evans, Reference Evans2018; Negri et al., Reference Negri, Schubart and Mantelatto2018) for use as an outgroup. Sequences were aligned using ClustalW and trimmed in MEGA 12 (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Higgins and Gibson1994; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher, Suleski, Sanderford, Sharma and Tamura2024). The Bayesian phylogeny was then computed using MrBayes (Ronquist et al., Reference Ronquist, Teslenko, Van Der Mark, Ayres, Darling, Höhna, Larget, Liu, Suchard and Huelsenbeck2012) through the NGPhylogeny.fr web service (Lemoine et al., Reference Lemoine, Correia, Lefort, Doppelt-Azeroual, Mareuil, Cohen-Boulakia and Gascuel2019) using a General Time Reversible (GTR) model and gamma distributed rates. The analysis consisted of two parallel Markov Chain Monte Carlo runs, each with four chains, run for 10 × 106 generations, sampled every 500 generations with a burn-in fraction of 0.25. The consensus tree, with Bayesian posterior probabilities, was visualised using Interactive Tree of Life (Letunic and Bork, Reference Letunic and Bork2024). The sequence data created for this project were deposited in GenBank (Accession number: PX830597).

Morphology and identification

Diagnostic characters were recorded using the terminology of Davie et al. (Reference Davie, Guinot, Ng, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Von Vaupel Klein2015), Lai et al. (Reference Lai, Ng and Davie2010), Ng (Reference Ng, Carpenter and Niem1998), and Wee and Ng (Reference Wee and Ng1995). Identification was initially undertaken using FAO identification guides (Ng, Reference Ng, Carpenter and Niem1998; Tavares, Reference Tavares and Carpenter2003), followed by further assessment using keys and detailed taxonomic works, as detailed in the results. As the first gonopods of males are important diagnostic characters in Charybdis (Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Husdson and Campbell1957), these were dissected from the specimen for computerised tomography scanning.

Computerised tomography scanning

The male first gonopod was securely positioned in a 0.5 ml Eppendorf Safe-Lock tube using plastic foam, with a small amount of ethanol added to prevent desiccation following the method outlined in Goatley and Tornabene (Reference Goatley and Tornabene2022). The specimen was scanned using a Zeiss Xradia 520 Versa at the Natural History Museum, London. The X-ray source was operated at 110 kV and 91 µA with an exposure time of 3 s. A 0.4X lens was used, and 2034 projection images were acquired. Image reconstruction was performed using the Zeiss Reconstructor software, yielding a voxel size range of 4.2 µm.

VGStudio Max (version 2.2) was applied to visualise the scans, converting the data into TIFF stack formats for further processing with the open-source 3D surface rendering software Drishti (Limaye, Reference Limaye2012; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Clark, Clark and Kamanli2021). For visualisation in this study, screen grabs were captured and edited in Adobe Photoshop CS6 to enhance image quality and resolution to 300 dpi. These were saved in .TIFF format. Scan data created for this project were deposited in MorphoSource (www.morphosource.org; ark:/87602/m4/805675).

Results

Phylogenetic analysis

Our BLASTn search revealed that our COI sequence data (658 base pairs) were identical to two records and 99.84% similar to a third record on GenBank. Two of these records are identified as Charybdis sp., while one of the identical matches is identified as Charybdis (Archias) pusilla in Cubelio et al. (Reference Cubelio, Venugopal, Sankar, Ameri, Padate and Takeda2023). Pairwise distance calculations, with variance estimated from 1000 bootstrap replicates, indicate that these four samples are highly similar, with all standard error intervals overlapping zero (Table 2).

Table 2. The number of base differences per site between sequences of the Charybdis (Archias) hoplites specimen from Southampton Water and the three closest hits using BLASTn on NCBI GenBank. GenBank accession numbers are presented following names. Standard error estimates from 1000 bootstraps are shown above the diagonal (italic). Analyses were conducted in MEGA12 (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher, Suleski, Sanderford, Sharma and Tamura2024)

The molecular phylogeny (Figure 2, Fig. S1) resolves our specimen as inseparable from the three aforementioned records on GenBank. These are positioned within C. (Archias), which forms a well-supported monophyletic group. Following the phylogenies of Evans (Reference Evans2018) and Negri et al. (Reference Negri, Schubart and Mantelatto2018), the validity of C. (Charybdis) remains uncertain, as our phylogeny resolves this subgenus as a poorly supported and polyphyletic group with C. (C.) feriata sister to all other members of the ingroup. Notably, within the C. (Charybdis) japonica group, there were some unexpected taxa, including six records of Gaetice depressus (Varunidae), suggesting that some GenBank records for these taxa are misidentified (Fig. S1).

Figure 2. Bayesian phylogeny calculated from the 50 closest hits to the Charybdis (Archias) hoplites specimen collected from Southampton Water, and three Thalamita spp. as an outgroup. Numbers adjacent to branches indicate posterior probabilities. Tip labels include GenBank accession numbers. The number of sequences resolved within collapsed nodes is indicated in parentheses following the tip labels. * indicates a grouping of species identified as Charybdis (Archias) japonica (×8) and Gaetice depressus, Varunidae (×6) from GenBank. Coloured backgrounds delineate the subgenera: C. (Archias), Orange; C. (Charybdis), pink; outgroup, Thalamita spp., Purple. Complete phylogeny – without collapsed nodes – is provided in Figure S1.

Morphology and identification

The hexagonal carapace, six anterolateral teeth and paddle-like last walking legs suggested the specimen was best placed within the Portunidae (Ng, Reference Ng, Carpenter and Niem1998; Tavares, Reference Tavares and Carpenter2003). The presence of six anterolateral teeth indicated that this specimen was unlike any portunids from the Atlantic (Tavares, Reference Tavares and Carpenter2003). Using Indo-Pacific identification keys (Ng, Reference Ng, Carpenter and Niem1998), six teeth on the anterolateral margin and a frontal carapace margin distinctly less than half the greatest width of the carapace (Figures 3–6) suggest that the Southampton specimen is placed in Charybdis, a conclusion supported by the molecular data.

Figure 3. Preserved specimen of Charybdis (Archias) hoplites (Wood-Mason, Reference Wood-Mason1877), male, Southampton Water, NHMUK reg. 2025.2075. (A) Dorsal view; (B) Ventral view with arrow indicating regeneration bud of left first pereiopod; (C) Dorsal view of frontal margin. Images taken by Peter Grugeon, NHM Publishing and Image Resources.

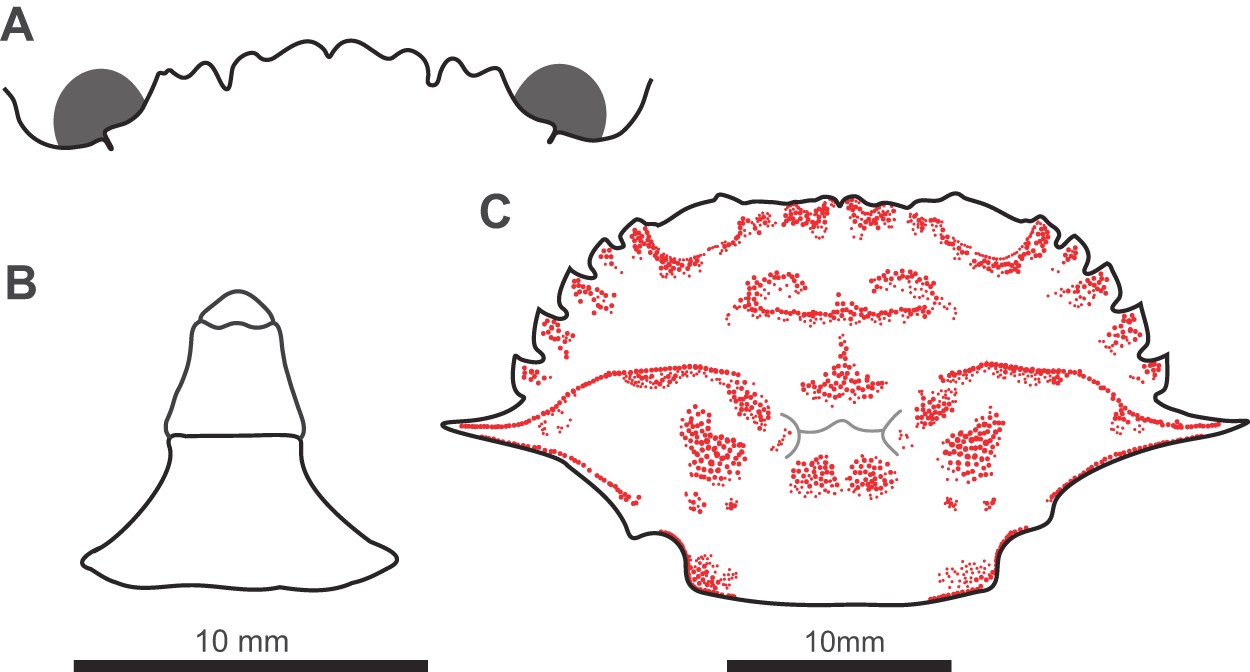

Figure 4. Diagnostic characters of Charybdis (Archias) hoplites (Wood-Mason, Reference Wood-Mason1877). (A) The frontal margin. (B) The abdomen of the single male specimen. (C) The pattern of granulation on the carapace (red stippling). Grey lines indicate the cervical groove (sinuous epibranchial line running from sixth anterolateral tooth). Scale bar for (A) and (B) beneath panel (B).

Figure 5. A computerised tomography scan of the distal tip of first gonopod of Charybdis (Archias) hoplites (Wood-Mason, Reference Wood-Mason1877). Red arrow indicates a row of three small, distinct tubercles.

Figure 6. Fresh specimen of Charybdis (Archias) hoplites (Wood-Mason, Reference Wood-Mason1877) from Southampton Water, displaying live colouration.

Charybdis comprises ca. 60 species assigned to several subgenera (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Guinot and Davie2008). The status of these subgenera has been in constant revision, but currently these are C. (Charybdis) De Haan, 1833; C. (Archias) Paulson, 1875; and C. (Gonioneptunus) Ortmann, 1893. According to Wee and Ng (Reference Wee and Ng1995) and Ng (Reference Ng, Carpenter and Niem1998), the angle between the posterolateral carapace margin and the posterior carapace margin is a reliable character to separate subgenera: angular versus round. The presence of an angular junction in the Southampton specimen suggests it should be assigned to C. (Archias).

Given the unknown native range of the Southampton specimen, its lack of chelae, and the limited number of global keys for Charybdis (Archias) spp., several keys were used to identify the Southampton Water specimen.

Using the Wee and Ng (Reference Wee and Ng1995) guide to Malaysian and Singaporean Charybdis and Thalamita species, the Southampton specimen keyed out as C. (Archias) hongkongensis. Using Ng (Reference Ng, Carpenter and Niem1998), the specimen keyed out as C. (Archias) truncata – the only member of C. (Archias) in this guide. The pattern of granulation on the carapace of the Southampton specimen differs from both of these species, with a medial triangular patch of granules (Figure 4) not reported in either. Furthermore, the margin of the penultimate segment of the male abdomen is convex in C. (A.) hongkongensis and C. (A.) truncata versus straight in the Southampton specimen (cf. Leene, Reference Leene1938; Figure 4).

Using the global portunid key of Leene (Reference Leene1938) and the keys of Alcock (Reference Alcock1899b), Apel and Spiridonov (Reference Apel and Spiridonov1998), and Türkay and Spiridonov (Reference Türkay and Spiridonov2006) for India, the Arabian Gulf, and Western Indian Ocean, respectively, the Southampton specimen was identified as Charybdis (Archias) hoplites (Wood-Mason, Reference Wood-Mason1877). All characters of the Southampton Water specimen agree with the descriptions in Alcock (Reference Alcock1899b), Leene (Reference Leene1938), and Wood-Mason (Reference Wood-Mason1877), supporting this identification.

While the molecular evidence suggested that the Southampton Water specimen was C. (A.) pusilla, this actually strengthens the argument for its placement within C. (A.) hoplites. Charybdis (A.) pusilla has long been recognised as being similar to C. (A.) hoplites, with Alcock (Reference Alcock1899b) describing C. (A.) pusilla as C. (Goniohellenus) hoplites var. pusilla, and Apel and Spiridonov (Reference Apel and Spiridonov1998) and Türkay and Spiridonov (Reference Türkay and Spiridonov2006) recognising it as a subspecies of C. (A.) hoplites. Cubelio et al. (Reference Cubelio, Venugopal, Sankar, Ameri, Padate and Takeda2023), however, recognised C. (A.) pusilla as a species, and it is their specimens that are accessioned in GenBank, matching our Southampton Water specimen.

The main morphological characters distinguishing C. (A.) pusilla and C. (A.) hoplites are size (Alcock, Reference Alcock1899b; Leene, Reference Leene1938) and the relative length of the merus of the last ambulatory leg (Apel and Spiridonov, Reference Apel and Spiridonov1998). Type material of C. (A.) pusilla has a maximum carapace width of 16 mm (Alcock, Reference Alcock1899b). By contrast, C. (A.) hoplites has an adult size range of 28.5–57.5 mm (Apel and Spiridonov, Reference Apel and Spiridonov1998). The merus of the swimming leg of C. (A.) pusilla is described as being ‘twice as long as broad’ versus 1.6 times in C. (A.) hoplites (Apel and Spiridonov, Reference Apel and Spiridonov1998). The Southampton specimen has a carapace width of 35 mm, and a swimming leg merus 1.6 times longer than wide. Placement in C. (A.) hoplites, therefore, seems parsimonious.

Taxonomy

Superfamily Portunoidea Rafinesque, 1815

Family Portunidae Rafinesque, 1815

Subfamily Thalamitinae Paulson, 1875

Genus Charybdis De Haan, 1833

Subgenus Charybdis (Archias) Paulson, 1875

Charybdis (Archias) hoplites (Wood-Mason, Reference Wood-Mason1877)

Synonyms:

Goniosoma hoplites Wood-Mason 1877: 422; Alcock & Anderson 1894: 184, 1896: pl. 23, Figure 6; Alcock 1899: 67–68; Gordon 1931: 534–536.

Charybdis (Goniohellenus) hoplites – Alcock 1899b: 64–65; Leene 1938: 99, figs 53–54; Chhapgar 1957: 423, fig. 7h; Gordon 1931: text fig. 12a, b, b′; Naderloo 2017: 182, figs 20.13a, 20.15; Apel & Spiridonov 1998: 211–213, figs 31, 33.

Charybdis hoplites forma typica – Leene 1938: 99–102, figs 53–54

Charybdis hoplites – Tirmizi & Kazmi 1996: 28 (key), 29–32, figs 13–14.

Charybdis (Archias) hoplites – Ng et al. 2008: 153–154 (list)

Abbreviations used: coll. = collected by, cw = carapace width taken as the maximum width between the tips of the lateral carapace spines in mm, reg. = registration number, stn = station.

Distribution: Madras, Bay of Bengal (Wood-Mason, Reference Wood-Mason1877); RIMS Investigator, Bay of Bengal, stn 159, 14.0986°, 80.4222°, 205 m; stn 170, 13.0183°, 80.6155°, 196 m; stn 172, NE of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), 13.0183°, 81.2958°, 365–640 m (Alcock and Anderson, Reference Alcock and Anderson1894); Coromandel Coast, the Eastern Ghats, Indian state of Tamil Nadu, 146–201 m (Alcock, Reference Alcock1899a, Reference Alcock1899b); off the Indus Delta, 29–80 m (Alcock, Reference Alcock1899b); Iran (Nobili, Reference Nobili1906; Naderloo, Reference Naderloo2017); Bahrain (Stephensen, Reference Stephensen1946); Saudi Arabia (Basson et al., Reference Basson, Burchard, Hardy and Price1977); Off Pakistan (Tirmizi and Kazmi, 1996); Arabian Gulf (Apel and Spiridonov, Reference Apel and Spiridonov1998).

Charybdis (Archias) hoplites: 1♂, cw 34.97 mm, damaged, without chelae and left pereiopod 1, cooling water intake of Marchwood Power Station during fish/crustacean impingement monitoring, 50.9014°, −1.4407°, River Test, Southampton Water, Hampshire, England, coll. Robin Somes & Richard Seaby, Pisces Conservation Ltd, and Christopher Goatley, University of Southampton, 24/07/2025, NHMUK reg. 2025.2075.

Material examined: Charybdis (Goniohellenus) hoplites stn 70, 25.5700°, 57.3917° to 25.5500°, 57.4200°; 25.xi 1933, 196 m, coll. HEMS Mabahiss, John Murray Expedition, det. Michael Türkay, July 1982, NHM reg. 1991.153.9, 6♂, 1 damaged, cw 39.51–48.83 mm, 3♀, cw 33.22–38.61 mm; stn 75, 25.1800°, 56.7917° to 25.1633°, 56.7917°; 28.xi 1933, 201 m, coll. HEMS Mabahiss, John Murray Expedition, det. Michael Türkay, July 1982, NHM reg. 1991.162.1, 1♂, cw 31.50 mm.

Description: Carapace transversely hexagonal, width 1.97 times length (Figure 3); frontal margin 0.25 times carapace width with eight rounded teeth (including inner orbital teeth), notch between teeth two and three (from orbit) twice as deep as others (Figure 4); six anterolateral teeth, first five pointed anteriorly, posterior tooth pointing laterally and more than double length of others (Figures 3 and 4); junction between posterolateral carapace margin and posterior margin of carapace angular; carapace with lines and patches of granules, scroll shaped line anteromedially followed by medial triangular patch, epibranchial ridge sinuous expanding medially into teardrop shaped patch, four patches posterior to cervical groove medial patches circular, lateral patches larger and pyriform, lines and patches of granules scattered around carapace margins (Figure 4). Second male pleomere with straight lateral margins; proximal width 1.8 times distal width (Figure 4). Merus of all ambulatory legs with spine on posterior distal margin; merus of swimming leg 1.6 times longer than wide (Figure 3). Distal tip of first gonopod with a row of three small, distinct tubercles (Figure 5).

Colour in life: Carapace green-brown; walking legs pale brown with covering of short, darker pubescence (Figure 6); anterior surfaces pale cream-brown.

Colour in preservation: Carapace orange-brown with granulations appearing paler; walking legs pale brown with covering of short, pubescence darker brown; anterior surfaces pale cream (Figure 3).

Remarks: Ng et al. (Reference Ng, Guinot and Davie2008) commented that the name Archias Paulson, 1875 (type species A. sexdentatus Paulson, Reference Paulson1875), has precedence over Charybdis (Goniohellenus) Alcock, 1899 (type species Goniosoma hoplites Wood-Mason, Reference Wood-Mason1877). Noting, however, that the type species of Archias (A. sexdentatus Paulson, Reference Paulson1875) is poorly known, they deferred from a revision. It was treated as a possible junior subjective synonym of C. (Goniohellenus) hoplites (Wood-Mason, Reference Wood-Mason1877) or C. (G.) longicollis Leene, 1938 (see discussion in Apel and Spiridonov, Reference Apel and Spiridonov1998), but its precise classification was unclear until fresh specimens became available. A neotype will probably be necessary to stabilise the taxonomy of these names. The figures of A. sexdentatus provided by Paulson (Reference Paulson1875: pl. 8 Figure 3–3b), however, agreed well with what is now known as C. (G.) hoplites, and there appears to be little doubt that they belong to the same subgenus. Prema et al. (Reference Prema, Ravichandran and Sivakumar2021) recognised this and used Archias Paulson, 1875, in place of Goniohellenus Alcock, 1899.

Discussion

Recorded here is an observation of a non-native species of portunid crab in Southampton Water, United Kingdom. This specimen of Charybdis (Archias) hoplites (Wood-Mason, Reference Wood-Mason1877) represents the first record of this species in the Atlantic and the highest latitude record of any member of this genus (GBIF, 2025). Members of this genus are well known for their capacity to exploit novel habitats, with at least six species being reported as alien species worldwide (Table 1). The most likely method of introduction of our specimen is in ballast water or hull fouling from one of the many ships visiting the Port of Southampton.

The native range of C. (A.) hoplites includes the Persian/Arabian Gulf, Gulf of Oman, Arabian Sea, and Bay of Bengal, with a single record from the Southern Red Sea (Türkay and Spiridonov, Reference Türkay and Spiridonov2006; GBIF, 2025). Direct transport to the Port of Southampton in ballast water could be possible, as regular cargo services run direct from the home range of C. (A.) hoplites, with a journey time of approximately 30 days (CMA CGM, 2025; DP World, 2025; ONE, 2025). This falls within the range of larval durations of other members of the genus (Dineen et al., Reference Dineen, Clark, Hines, Reed and Walton2001), and survival of adults in ballast water is likely. Alternatively, transport could have been from another port outside the home range of C. (A.) hoplites with an undetected population of these crabs. Transport of adults on hull fouling is also possible, particularly if shorter distances from such undetected populations are considered (Cuesta et al., Reference Cuesta, Almón, Pérez-Dieste, Trigo and Bañón2016).

As only a single male specimen was recorded and the environmental conditions in Southampton Water differ considerably from those in the native habitats of C. (A.) hoplites, this species record will hopefully represent a transient occurrence. The collection location has shallow (<15 m) water depth and moderate turbidity. Between November 2024 and October 2025, salinity at the collection site in the Test Estuary ranged from 27.8 to 33 psu, and water temperature varied from 7.5°C in February to 21°C in August (Environment Agency, 2025).

The depth, turbidity, and salinity of the collection location are within the known tolerances of Charybdis spp. (Türkay and Spiridonov, Reference Türkay and Spiridonov2006; Narita et al., Reference Narita, Ganmanee and Sekiguchi2008; Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Gerner and Sewell2010). Winter temperatures would seem likely to pose challenges to the persistence of warm-water C. (A.) hoplites in Southampton. Specific information on temperature tolerance for this species is limited, but the congeneric C. (C.) feriata (Linnaeus, 1758) exhibits markedly reduced survival at 20°C (Baylon and Suzuki, Reference Baylon and Suzuki2007). By contrast, larval C. (C.) japonica show high tolerance to low temperature conditions (10°C) (Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Gerner and Sewell2010). Given that C. (A.) hoplites occupies depths exceeding 360 m in the Indian Ocean (Türkay and Spiridonov, Reference Türkay and Spiridonov2006), where temperatures drop below 11°C (Ray et al., Reference Ray, Das and Sil2024), the species’ survival under cooler conditions cannot be ruled out.

Reliable identification of invasive species requires appropriate taxonomic resources. In the case of Charybdis, identification of the Southampton Water specimen required the use of multiple regional and global keys (Leene, Reference Leene1938; Wee and Ng, Reference Wee and Ng1995; Apel and Spiridonov, Reference Apel and Spiridonov1998; Ng, Reference Ng, Carpenter and Niem1998; Türkay and Spiridonov, Reference Türkay and Spiridonov2006). Conflicting outcomes, a complex taxonomic history (see Remarks), and probable misidentifications in GenBank indicate that taxonomic resources for Charybdis remain incomplete. Given the prevalence of crabs as invasive species worldwide (Brockerhoff and McLay, Reference Brockerhoff, McLay, Galil, Clark and Carlton2011), there is a clear need for new genus-level keys, together with curated DNA voucher material and reliable barcodes. These resources would facilitate early detection and support eDNA-based monitoring of alien species.

Once reported, almost two-thirds of alien crabs become established (Brockerhoff and McLay, Reference Brockerhoff, McLay, Galil, Clark and Carlton2011) – a pattern common among alien marine organisms (Minchin et al., Reference Minchin, Cook and Clark2013) – and the Port of Southampton is at high risk from invasive species (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Bishop, Carlton, Dyrynda, Farnham, Gonzalez, Jacobs, Lambert, Lambert, Nielsen and Pederson2006; Minchin et al., Reference Minchin, Cook and Clark2013; Tidbury et al., Reference Tidbury, Taylor, Copp, Garnacho and Stebbing2016). The occurrence of C. (A.) hoplites in Southampton Water illustrates how global shipping continues to link distant marine ecosystems. Whether this individual represents an isolated vagrant or the first sign of an emerging population remains uncertain, underscoring the importance of continued monitoring to detect alien species and, if necessary, implement control measures prior to their establishment.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315426101131.

Author contributions

Designing the study: R.M.H.S. and R.S.; Carrying out the study: C.H.R.G., R.M.H.S., and R.S.; Analysing the data: C.H.R.G., R.S., S.A.K., B.C., and P.F.C.; Writing – original draft: C.H.R.G.; Writing – review and editing: all authors.

Funding

Field sampling for this study was funded by Marchwood Power Station, as part of their impingement monitoring project. DNA sequencing was funded by the School of Ocean and Earth Science, University of Southampton.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The findings and views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Marchwood Power Station or its staff.

Ethical standards

N/A.